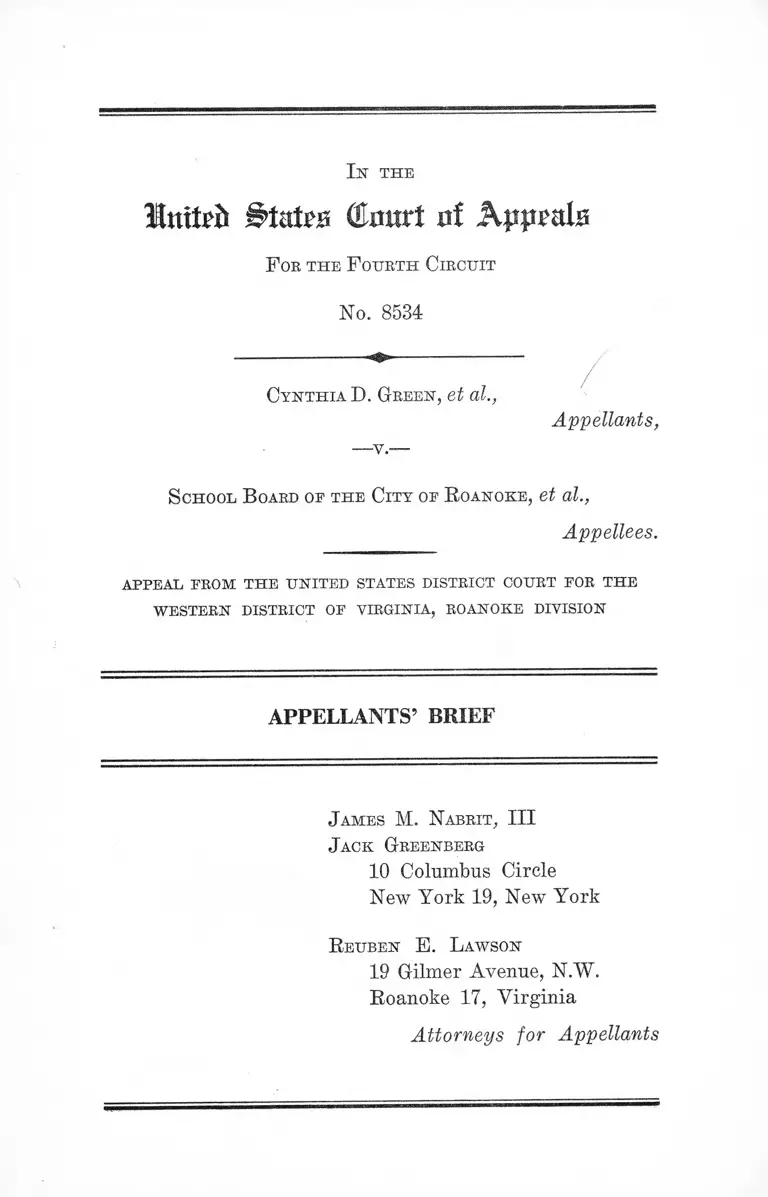

Green v. City of Roanoke School Board Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Green v. City of Roanoke School Board Appellants' Brief, 1961. 416e2b39-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aa79b767-c461-42b7-b22c-939ce65318e3/green-v-city-of-roanoke-school-board-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

lutttb Cmirt $f Kppmh

F or t h e F ourth C ircu it

No. 8534

Cy n th ia D. Gr e e n , et al.,

-v.—

Appellants,

S chool B oard op t h e C ity op R oanoke, et al.,

Appellees.

appeal prom t h e u n ited states district court for t h e

WESTERN DISTRICT OP VIRGINIA, ROANOKE DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J ames M. N abrit, III

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R eu ben E. L awson

19 Gilmer Avenue, N.W.

Roanoke 17, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ........................................ 1

Question Involved.............................................-.......... 8

Statement of F ac ts........................................... 9

I. The Segregated Pattern in the City School

System........................................ 9

II. Facts With Regard to Plaintiffs’ Applications 12

A r g u m e n t ............................................................ 21

The Pupil Assignment Policies, Standards and

Procedures Used by the Roanoke City School

Board and the Pupil Placement Board Are Ra

cially Discriminatory and Should Be Prohib

ited ...... ....................... 21

A. The initial assignment system and the

feeder system are discriminatory.......... 21

B. The defendants’ special transfer criteria

applied to Negroes seeking to enter white

schools are discriminatory..................... 26

C. The Placement Board’s protest and hear

ing procedure was not an adequate and

expeditious remedy ................................ 33

D. The Court has clear power to grant com

plete relief by issuing an order restrain

ing the discriminatory initial assign

ment practices......................................... 36

PAGE

Conclusion 40

T able op A tjthobities

Cases

Adkins v. School Board of City of Newport News,

148 F. Snpp. 430 (E. D. Va. 1957), aff’d 246 F, 2d

325 (4th Cir. 1957) ...................................... ........... 34

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 266 F. 2d 507 (4th Cir. 1959) ................... 36

Allen y . School Board of City of Charlottesville, 3

Race Rel. Law R. 937 (W. D. Va. 1958) ................. 34

Beckett v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 185 F.

Supp. 459 (E. D. Va. 1959), aff’d sub nom. Farley

v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960) .................. 23, 33

Blackwell v. Fairfax County School Board, 5 Race

Rel. Law R. 1056 (E. D. Va,, Sept. 22, 1960) ....... 34

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .... 23, 28

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) .... 36

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 242 F. 2d 156

(5th Cir. 1954) ......................................................... 39

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956) ...... 37

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ................... ...23, 24, 25

Covington v. Edwards, 264 F. 2d 780 (4th Cir. 1959) 37

Dodson v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville,

289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961) .................................. 31

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) .......... 25, 28

Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960) ...... 23, 33

Hamm v. County School Board of Arlington County,

263 F. 2d 226 (4th Cir. 1959) .................................. 32, 34

Hamm v. County School Board of Arlington County,

264 F. 2d 945 (4th. Cir. 1959) .................................. 32, 34

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U. S. 32 (1940) ..................... 39

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U. S. 321 (1944) .......... ....... 36

11

PAGE

I l l

Hill v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 282 F.

2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960) ......................................... 22, 24, 25

Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 265 F. 2d

95 (4th Cir. 1959) .................................................... 37

Jackson v. The School Board of the City of Lynch

burg, Va. (W. D. Va., C. A. No. 534, Jan. 15, 1962,

not yet reported) ....... ............................................ 35, 39

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ..................... ............ 27, 31, 35, 39

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 4 Race

Rel. Law R. 31 (E. D. Va., Oct. 22, 1958; Jan. 23,

1959; Feb. 6, 1959); aff’d 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir.

1960); 179 F. Supp. 280 (E. D. Va. 1959) .............. 34

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d

370 (5th Cir. 1960) .................................................. 32,39

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 179

F. Supp. 745 (M. D. N. C. 1959), rev’d 283 F. 2d

667 (4th Cir. 1960) .................................................. 38

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (4th Cir.

1951) ....................................-................................... 29

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390 (1923) ................... 29

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) .....25, 28,

32, 39

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925) ...... 29

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 II. S. 395 (1946) 36

School Board of the City of Charlottesville v. Allen,

240 F. 2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956) .................................... 36

School Board of the City of Norfolk v. Beckett, 280

F. 2d 18 (4th Cir. 1958) ....................................... 32

Smith v. Swormstedt, 16 How. (U. S.) 288, 14 L. ed.

942 (1853)

PAGE

39

IV

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County, 159 F. Supp. 567 (E. D. Ya. 1957), aff’d

252 F. 2d 929 (4th Cir. 1957), cert, denied 356

U. S. 958 ................................................................. 33

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County, 166 F. Supp. 529 (E. D. Va. 1958), aff’d

in part and remanded in part, sub nom. Hamm v.

County School Board of Arlington County, 263

F. 2d 226, 264 F. 2d 945 (4th Cir. 1959) ................. 34

Thompson v. County School Board, etc., 4 Race Rel.

Law R. 609 (E. D. Va. July 25, 1959); 4 Race Rel.

Law R. 880 (E. D. Ya. Sept. 1959); 5 Race Rel.

Law R. 1054 (E. D. Va., Sept, 16,1960) ................. 34

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County (E. D. Va., C. A. No. 1341, unreported

June 3, 1959) ..................... ............ -...................... 34

Walker v. Floyd County Board (W. D. Va., C. A.

No. 1012; Sept. 23,1959, unreported) ..................... 34

Rules and Statutes

28 U. S. C. §§1291,1292(a) (1) ............................ 1

28 U. S. C. §1343 .........................- ....................... 2

42 U. S. C. §1981 .............................................. 2

42 U. S. C. §1983 .................................................. 2

F. R. C. P. Rule 23(a)(3) ...... .........................2,38,39

F. R. C. P. Rule 54(c) .................................... 37

* Code of Va., §22-232.8 .................................... -..... 33

Other Authorities

Black, The Lawfulness of the Segregation Decisions,

69 Yale L. J., 421 (1959) ....................................... 30

Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence, 5th Ed., 5 Symons,

1941, Vol. 1, §§260, 261a-n

PAGE

39

I n t h e

Ituiti'ii &mxt 0! Appals

F or t h e F ourth C ircuit

No. 8534

Cy n th ia D. Gr e e n , et ah,

—v.-

Appellants,

S chool B oard o r t h e C ity of R oanoke, et ah,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM TEIE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, ROANOKE DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement o f the Case

This is an appeal from an order (216a)1 entered Octo

ber 4, 1961, denying injunctive and declaratory relief in an

action brought by the plaintiffs-appellants, Negro school

children and parents in Roanoke City, Virginia, against

the School Board of Roanoke City, the Superintendent of

Schools, and the Pupil Placement Board of the Common

wealth of Virginia. This appeal is brought under 28

IT. S. C. §§1291, and/or 1292(a) (1).

1 Citations are to the Appendix to this Brief unless otherwise

indicated.

2

The complaint, filed August 20, 1960, by 28 Negro pupils

(20 of whom are appellants) and their parents and guard

ians, was a class action “on behalf of all other Negro

children attending the public schools of the City of Roanoke

and their respective parents or guardians” (7a), under Rule

23(a)(3), F. R. C. P. There was jurisdiction under 28

U. S. C. §1343, the action being authorized by 42 U. S. C.

§1983 to enforce rights secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, and by 42

U. S. C. §1981 providing for the equal rights of citizens.

The complaint identified the defendants City School

Board and Superintendent of Schools (7a) as a state

agency and a state agent, respectively, exercising various

duties in maintaining, operating, and administering the

public schools oof Roanoke City, and identified defendants

Oglesby, Justis and Wingo constituting the Virginia Pupil

Placement Board, a state agency vested with statutory

powers to place pupils in schools (10a). The complaint

alleged that despite the Supreme Court’s decisions that

state-imposed racial segregation was unconstitutional and

plaintiffs’ applications to the defendants to attend public

schools which they are eligible to enter except for their

race, the defendants were pursuing a policy, practice, cus

tom, and usage of racial segregation and would continue

to do so unless restrained by the Court (lla-12a). The

complaint alleged that defendants were applying the Vir

ginia Pupil Placement Act in such a manner as to perpetu

ate the pre-existing segregation system (lOa-lla); that they

required pupils seeking to attend a nonsegregated school to

pursue certain inadequate administrative remedies (11a);

that plaintiffs had applied to enter all-white schools prior

to the 1960-61 school term and had been denied admission

on a racially discriminatory basis (12a); and that the vari

ous practices of the defendants complained of denied plain

tiffs their liberty without due process of law and the equal

3

protection of the laws secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment (12a).

Plaintiffs sought a declaration that certain of the ad

ministrative procedures prescribed by the Pupil Placement

Act were inadequate to secure plaintiffs’ rights to a non-

segregated education and need not be pursued by them as

a prerequisite to judicial relief, and prayed for a declara

tion that the Pupil Placement Board’s policies and practices

in assigning pupils to segregated schools on the basis of

race was unconstitutional (13a-14a). The complaint also

sought temporary and permanent injunctive relief to re

strain defendants “from any and all action that regulates

or affects, on the basis of race or color, the admission,

enrollment or education of the infant plaintiffs, or any other

Negro children similarly situated, to and in any public

school operated by the defendants” (14a). The complaint

asked that the defendants be required to present to the

Court a comprehensive plan for desegregation of the school

system in the event that they requested any delay in full

compliance (15a).

On August 23, 1960, Judge John Paul heard and denied

the motion for preliminary injunction as well as the School

Board’s oral motion to dismiss. On September 12, 1960,

the city school authorities filed a “Motion to Dismiss and

Answer” (19a). The motion to dismiss urged that the com

plaint failed to state a claim charging (1) that facts de

tailing the allegations of discrimination were not alleged;

(2) that plaintiffs had not exhausted administrative

remedies under the Virginia Pupil Placement Act, and

(3) that plaintiffs should be required to seek judicial re

view in the state courts. The answer admitted the identity

of the parties as alleged; denied that plaintiffs were en

titled to maintain a class action; admitted that plaintiffs

applied for admission at certain schools and were assigned

4

elsewhere, but denying that the refusals were racially dis

criminatory. The answer alleged that the School Board

had “devoted itself to a concerted effort to maintain good

race relations” ; that prior to the plaintiffs’ and other ap

plications in May 1960, no Negro pupils had requested

admission to any white school; that of the 39 Negro ap

plicants to white schools, 9 had been granted admission

to white schools by the Pupil Placement Board on August

15, 1960, and; that plaintiffs were assigned to all-Negro

schools in accordance with educational policy and not on

account of race or color.

The Placement Board’s answer (24a) generally denied

the allegations of the complaint except for the identity

of the defendants; asserted that plaintiffs’ requests were

denied because of the lack of a favorable recommendation

from the city school authorities and the Placement Board’s

policy “that no pupil shall be transferred from one school

to another in the absence of a favorable recommendation

by local school officials” ; denied that the plaintiffs were

placed in school or denied transfers on the “sole ground

of race or color in contravention of any constitutional

rights” ; asserted that the Placement Board was “under no

obligation or compunction to promote or accelerate the

mixing of the races in the public schools” and that “vol

untary segregation of the races is lawful and the normal

wish of the parents of the overwhelming majorities of

both Negro and white races” ; and set up in defense the

fact that the plaintiffs had not invoked the Board’s protest

and hearing procedures.

Judge Oren R. Lewis, sitting by special designation,

tried the case on May 25-26, 1961. Evidence presented by

the plaintiffs was received. The Court called a witness

and introduced the Court’s exhibits. Defendants called no

witnesses. On July 10, 1961, the Court filed its memoran

dum opinion (202a).

5

The Court determined that plaintiffs had been denied

transfers on the basis of the Placement Board’s criteria

relating to residence, academic aptitude and achievement,

and sibling relationships (205a). The Court rejected de

fendants’ claim that plaintiffs’ suit should be dismissed for

failure to file a protest with the Pupil Placement Board

under the placement statute holding that since the trans

fers were denied only five or sis days before the school

term “there was unsufficient time to have heard a protest

if one had been filed” (206a). The Court ruled that the

protest procedure was “not unreasonable and must be

complied with escept in unusual cases” (209a), and sug

gested that the Placement Board establish an earlier date

for applications to be submitted (209a). The Court also

ruled that the state judicial remedies provided by the Act

need not be pursued by plaintiffs (209a).

With regard to plaintiffs’ individual applications, the

Court determined:

1. that one pupil had been admittedly denied a transfer

in error and must be admitted at the next term (206a);

2. that three pupils had been denied on the ground

of residence; that this was nondiscriminatory and injunctive

relief was denied (206a) ;

3. that five pupils were denied transfers on the basis

of residence and because they were academically below

the median of the white school; that this was not dis

criminatory and injunctive relief should be denied (207a);

4. that one pupil had been denied on the basis of a

“very low scholastic aptitude” ; that that was nondis

criminatory and relief was denied (207a);

5. that five pupils were denied because below the median

at the school applied fo r; that the Court could not deter

mine how far they were below the median and that the

6

Placement Board should re-examine these applications

(207a) ;

6. that two pupils were denied because they were

“slightly below or even with the median” of the class ap

plied fo r; that “this ground alone would appear to be

discriminatory” and, therefore, the Placement Board should

re-examine the applications;

7. that three applicants were denied on the ground that

they were “only slightly above the median” ; that this

ground was “obviously discriminatory” and that the Court

would order their admission “unless, upon re-examination,

the Board establishes nondiscriminatory reasons for deny

ing these applications” ;

8. that five applicants were denied because of sibling

relationships; that these applicants should not be denied

unless the Board could establish that this criterion was

uniformly used and these applicants should be re-ex

amined.

The opinion directed the Placement Board to report to

the Court before August 20, 1961, the result of its re

examination of 15 of the pupils, and stated that “the de

fendants will be heard upon the report of the re-ex

amination and any exceptions thereto, at a date to be

fixed by the Court” (208a).

The Court concluded that there was no evidence to justify

the charge that the Pupil Placement Board members were

administering the Act so as to preserve and perpetuate

the policy, practice, custom of assigning children to sepa

rate schools on the basis of their race and color (210a),

but that they were “conscientiously endeavoring to perform

their official duties in accordance with law and without

regard to race, color or creed” (211a).

7

The Court held that the Placement Board had statutory

power to place all students and that there was “no evidence

indicating that the School Board of the City of Roanoke or

its Division Superintendent are, in fact, performing these

duties; therefore, there is no legal justification for the

entry of a permanent injunction, and the motion so re

questing is herewith denied” (211a).

On August 20, 1961, the Placement Board served a copy

of its report on plaintiffs’ counsel2 indicating that five of

the pupils re-examined by it were granted the requested

transfers and that the other ten were again denied trans

fers on the grounds previously urged. Plaintiffs filed ob

jections to this report on September 8, 1961, and again

requested injunctive relief (212a). No hearing has yet been

held by the Court on the report and exceptions.

The Court’s order was entered on October 4, 1961, deny

ing the injunctive relief requested by plaintiffs (216a).3

Twenty of the infant plaintiffs filed a timely notice of

appeal from the order of October 4, 1961, on November 1,

1961 (220a).

2 The report was apparently also mailed to the Court, but was

not filed with the Clerk’s office and has not been included in the

record.

3 A proposed order was promptly tendered to the Court as di

rected in the opinion filed July 10, 1961, but was not entered until

October 4, because plaintiffs were unable to secure agreement of

counsel for the Placement Board as to the form, until after the

Court had fixed a hearing date for settlement of the order.

8

Question Involved

Whether the Court below erred in denying injunctive

and declaratory relief prohibiting and condemning as

racially discriminatory the defendants’ pupil assignment

standards and procedures where:

a. all pupils are initially assigned to schools in a racially

segregated pattern by the use of neighborhood area as

signments without any uniform rule of proximity or school

zones, and by the use of a “feeder system” in which the

all-Negro schools are organized in a separate unit for

assignments;

b. “routine” assignments and transfers recommended by

local authorities without parental objection are accepted

by the Placement Board without question and without the

application of any other criteria, but special assignment

criteria, unrelated to the organization of the pupils in the

schools, involving proximity of residence to schools, aca

demic test scores in relation to the median of the class

applied for, sibling relationships, and personality are ap

plied to the transfer applications of plaintiffs, since they

were Negroes seeking to enter all-white schools, and did

not have favorable recommendations by the local authori

ties;

c. Negro pupils applying to white schools must pursue

a burdensome and discriminatory protest and hearing pro

cedure except in “unusual cases” ;

d. the school authorities refuse to make any plans for

initial desegregation or eliminating the system of routine

placement on the basis of race.

These questions are presented by the pleadings and the

evidence received below and were decided against the con

tention of the appellants.

9

S tatem en t o f Facts

I. T h e Segregated P attern in the City School System .

The Roanoke City public school system has about 40

schools (197a-199a) serving about 19,000 pupils, approxi

mately 4,100 of whom are Negroes (34a). There are seven

all-Negro schools, five elementary schools, a junior high

and a high school, which make up “Section No. II” in the

Roanoke City system (PL Ex. H, 65a, 197a). The other

schools in the system were attended only by white pupils

until 1960 when 30 Negro pupils applied to attend white

schools and nine of them were admitted in three schools

—Melrose, West End and Monroe Junior High School

(32a-33a).4 The all-Negro schools are staffed only by

Negroes, and the “white” schools are staffed only with

white teachers and principals (34a).

In September 1961 the all-white and predominantly white

schools were expected to have approximately 1,300 empty

seats (about 2,100 empty seats by the middle of the 1961-62

term), while the all-Negro schools were overcrowded and

expected to have 400 pupils above seating capacity in

September 1961 (36a, 197a-199a),

The Roanoke City schools are organized in six sections,

each section being composed of several elementary schools

which “feed” their students to a designated junior high

school which, in turn, “feeds” pupils upon promotion to

a designated high school (35a, 70a, 197a). Entering pupils

are placed in the school in their neighborhood—each

principal being familiar with the neighborhood his school

serves routinely recommends assignments on Pupil Place

ment forms in accordance with the neighborhood system

4 Since this case was decided a few other Negroes have been

admitted to white schools, including about 6 of the plaintiffs.

1 0

(70a). When pupils are promoted from one school to

another, the principals routinely make recommendations

on the basis of the feeder system (70a). In the all-Negro

“Section I I” the all-Negro schools feed their pupils only

to other all-Negro schools. The Superintendent could re

call no case where the Pupil Placement Board had not

accepted the local recommendation under the feeder sys

tem (70a). All of the schools have general programs, there

being no separate schools established with reference to

achievement or ability (52a, 56a, 57a). Assignments upon

promotion from one level to another are based on the

feeder system without regard to ability and achievement

tests (52a-53a). Within the schools there is some group

ing of pupils by ability or achievement (57a-58a). Where

pupils request transfers on the basis of change of resi

dence or when a new pupil enters the system, there is no

study of their academic tests or comparison with the

median scores in the schools they seek to enter (except in

the case of crippled or retarded children) (73a-75a).

The Pupil Placement Board routinely assigns over 99%

of the pupils without individual examination on the basis

of the local recommendations (135a) (10,000 pupils “for

an ordinary morning—a good Monday” (154a).

Mr. Oglesby testified that the Placement Board had no

standard procedure of reviewing the routine assignment

practices used in the local school districts, such as school

zones and feeder systems (142a). He stated when asked

if he knew anything about the Roanoke “feeder school”

system:

I don’t know the slightest thing about how they operate

their schools in Roanoke, not the slightest (142a).

In the small percentage of cases where the parents and

school authorities are in dispute, or where as in plaintiffs’

1 1

cases there is no local recommendation,5 the Placement

Board applies its assignment criteria for protested cases

(135a-141a), which involve generally the Board’s appraisal

of the pupil’s record to determine ability to adjust to a

new situation academically and otherwise, and a judg

ment of the distance from the pupil’s residence to the

schools involved (159a). The Board criteria are not in

writing and are only vaguely defined, as the testimony

by Chairman Oglesby set forth below, indicates.6

5 The Placement Board’s answer asserted its policy not to grant

transfers from one school to another “in the absence of a favorable

recommendation by local school officials” (24a).

6 Upon questioning by the Court, Mr. Oglesby testified (158a-

160a):

“Q. Now, does the Board or did the Board have at the time

of the Roanoke hearing had the Board itself, previous thereto,

established any standards or criteria which they used in con

nection with evaluating each of these applications! A. We

had been in existence, I believe, less than a month. We haven’t

had very much time for establishing criteria. We had not

established anything and we have not as of now established

any that would be considered. I think we just took the cases

as they were and tried to make a decision on our best judg

ment as it appeared to us.

Q. Then the Court understands that you didn’t have any

advance criteria or standard to compare these applicants with

at the time of the Roanoke hearing and you do not have any

now? A. That’s right,

Q. How can you make all transfers equal insofar as meeting

or coming close to a fixed standard throughout the State if

you don’t have a standard to go by? A. I don’t know, sir.

Q. What? A. I don’t know the answer to that, sir. We

have tried not to put a child in a situation where he couldn’t

handle himself, where we felt he was going to fail. The cri

teria for that would vary from place to place.

Q. I appreciate that. A. And we have, of course, gradually

formulated certain ideas, but as for having written out firm

criteria, I don’t think we have them.

Q. Now, you do use and you did use then in the Boanoke

case, as one of the criteria, the considered judgment of the

Board pertaining to the qualifications of the applicant to fit

in with the group he was seeking to enroll? A. Yes, sir.

(continued next page)

1 2

Neither the Roanoke school authorities nor the Place

ment Board have made any announcements of any plan

for desegregation (32a, 91a-92a).

II. Facts W ith Regard to P laintiffs’ Applications.

In May 1960, thirty Negro pupils submitted applications

for transfer to all-white schools to Superintendent Rushton;

nine other pupils filed such applications shortly there

after (38a, 193a-196a). The Pupil Placement forms of

these pupils are Exhibits F-l through F-39 (28a). They

also filed a petition requesting desegregation (194a).

Superintendent Rushton presented the applications to the

City School Board, and then forwarded them to the Pupil

Placement Board without any recommendations (38a, 48a).

The Placement Board asked the superintendent to submit

additional information with regard to these pupils “which

had to do with such things as maps showing the location

of pupils and academic records, health records, and any

other pertinent information which might be helpful in

Q. And, insofar as that criteria is concerned, it would ob

viously be different from locality to locality? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Because the reason he was seeking, obviously might be

different? A. Yes, sir.

Q. What other oral criteria did the Board have in mind

and use in addition to this fitness in the case of the Roanoke

applicants? A. My recollection, Your Honor, was very little

else except in the case, I believe, about four of them, the

matter of distance.

Q. But did you have any distance criteria? Did the Board

at that time have more or less a standard policy subject to

minimum or variation that distance would be one of the con

trolling criteria in approving or disapproving applicants? A.

Yes, sir.

Q. And did you have any other except distance and the

Board’s opinion after investigating all of the facts you could

get as to the fitness of the child to co-mingle with those he

sought to enroll with? A. I believe everything else could be

listed in that second classification in this case, my idea of it.

That is what I meant by that classification.”

13

understanding the local situation” (38a-39a). Mr. Wingo,

a member of the Placement Board, asked Superintendent

Rushton three questions with regard to these applications:

(1) “Are there Negro pupils who cannot he excluded from

attending white schools except for race?”; (2) “Would the

Superintendent and School Board so certify to the Pupil

Placement Board?” ; (3) . . what would happen in the

local communities if some Negro pupils were assigned to

white schools?” (39a). (Emphasis supplied.)

Subsequently, the superintendent’s two assistants (Mr.

A. B. Camper, now deceased, and Mrs. Dorothy Gibb on ey)

investigated the school records of the 39 Negro pupils

(40a). They gathered summaries of the children’s aca

demic records, including teachers’ comments on the pupil,

recent school grades and scores on intelligence and achieve

ment tests in the files (80a). Studies were made of the

achievement and intelligence test scores of the pupils in

the classes the Negroes sought to enter, and the class

median scores were determined (81a).

At a meeting held on August 15, 1960, Superintendent

Rushton, Mr. Camper and Mrs. Gibboney met with the

members of the Placement Board and the Board’s Execu

tive Secretary, Mr. Hilton, to discuss these 39 Negro pupils

(43a). The Superintendent insisted that neither he nor

his staff made any recommendation to the Placement

Board (48a-49a). He said: “and when they asked me for

a recommendation, I said straightforwardly that ‘it is

your responsibility to assign pupils; we will answer your

question’” (50a). However, there were nine pupils whom

Mr. Rushton “indicated to the Board could not be excluded

for any reason other than race” (45a). These nine pupils

were granted transfers to white schools by the Placement

Board on that day (45a, 28a-29a). Mr. Rushton testified:

“I told them that in my opinion if any of these 39 would

14

be successful in transferring from a segregated to a de

segregated school, I thought that these nine would prob

ably be more successful. That was my valid judgment. It

was not a recommendation. It was just when I was asked

a judgment as I was in these cases” (51a). The Placement

Board’s minutes for August 15, 1960, assigning the nine

Negro pupils to white schools recite in part as follows:

Inasmuch as the local school authorities of Roanohe

City applied, at the request of the Pupil Placement

Board, criteria and standards dealing with the trans

fers and assignments of pupils of different races to

the schools of that school division, which are regarded

by this Board as valid and reasonable, and since,

through the application of these criteria and stand

ards, the local school authorities are not in a position

to oppose legally the following assignments and trans

fers, the Pupil Placement Board takes the following

action: [List of 9 pupils and schools.] (28a-29a) (Em

phasis supplied.)

There was no written record of the August 15 meeting

except for the minutes quoted above, and a summary sheet

used during the conference and produced at the trial by Mr.

Hilton (87a-90a). This sheet is Plaintiffs’ Exhibit J (200a),

and was approved or accepted by the Board by acquiescence

as a summary of its action (161a-162a).

Mr. Oglesby, Chairman of the Placement Board, was not

able to state the reason for the denial of any particular

child’s transfer (153a). He said generally (136a-137a) :

Your Honor, we spent most of the afternoon, it is

my recollection, it might have been more, we spent a

good part of the day considering these 39 cases. We

got all of the information they could give us. At the

end of that time, based upon everything that we had,

15

we decided that in the case of 30 of these students they

weer poor risks. What I mean by that is, in some

cases they would definitely pull down the standards of

the school they went into. But in general our feeling

wyas that the child was not prepared to do the work

that he would have to do in that school; that he would

probably fail. I don’t mean all of them would fail.

But what I do mean is that in each case I felt there

was at least more than an even chance that he couldn’t

do the work. As a gambling proposition, I think—

statistics and probability are so tied together that the

simplest wray to talk about statistics is talk in terms

of probability. And the easiest way to make that clear,

clear as a gambling proposition, I would have felt if

somebody had been willing to offer me a bet, an even

bet, for $100 on each of those pupils, if I was betting

in the ordinary course of events, that child would not

make good in the school that he wants to be put in.

I wouldn’t consider it a gambling case for the 30. I

would consider it an investment. We are not infallible.

All w7e did was to judge the facts as we had—the best

we could get. That was our feeling about it. I believe

that it would have been a profitable gamble on the

basis of my having to give, say, two to one on the odds.

That is, of course, again, just guessing. That is the

way we decided it. That is about all we can do.

Mr. Wingo, called as a witness by the Court (161a),

testified as to the reasons for the rejection of each of the

pupils (170a-173a). His statement of the reasons for re

jection was accepted by the Court in its opinion (206a-

208a), as described above in the Statement of the Case, p. 5,

supra. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit J, mentioned above, indicated

only one ground for rejection of each pupil (200a, 169a);

Mr. Wingo, under questioning by the Court, indicated more

1G

than one ground for refusal of several pupils (170a). The

general categories involved were residence, academic test

scores, and sibling relationships (170a-173a).

With regard to residence, pupils were rejected who lived

closer to the schools attended than to the schools applied

for. Mrs. G-ibboney’s handwritten notes (Court’s Ex. No.

1, see column marked “Distance”) indicated the compara

tive distance between each pupil’s homes and the two

schools involved.7 8

Among the 11 pupils rejected on the ground of residence,

9 lived from one to seven blocks farther from the white

school than the Negro school; one pupil (No. 10) lived an

equal distance between the two schools, and another (No.

3) lived one block closer to the white school. Note that

pupils No. 10s and No. 3 were denied solely on the ground

of residence. The 17 plaintiffs rejected on other grounds

lived from 4 to 19 blocks closer to the white schools than

the Negro schools they attended.9 * 11 Thus, while living closer

to the Negro schools, an equal distance between Negro and

white schools, or even one block closer to the white schools

was treated as a basis for denying transfers on the resi

dence criterion; the fact that a pupil lived even as much

as 19 blocks closer to the white school did not entitle him

7 This portion of the Exhibit is explained at 115a. For example,

“ +19” means that a pupil is 19 blocks closer to the school applied

for than the one attended; minus figures indicate that the pupils

are a given number of blocks farther from the school applied, for

than the one attended.

8 Throughout the record pupils were referred to by key numbers

rather than names (30a). The key numbers are listed in Exhibit I

(201a).

9 The breakdown is as follows: There were 2 living 19 blocks

closer; 3 living 16 blocks closer; 2 living 12 blocks closer; 2 living

11 blocks closer; one living 10 blocks closer; one—9 blocks closer;

two—2 blocks closer; one—6 blocks closer; two—5 blocks closer,

and one—4 blocks closer (Court’s Exhibit No. 1).

17

to transfer to it. For example, Negroes living within one

block of a white school were denied transfers and assigned

to more crowded Negro schools 20 blocks away (133a).

Thus, no uniform proximity rule was applied; distance was

applied only as a factor to justify exclusions, not transfers.

The Placement Board applied its academic criterion to

reject 19 pupils as indicated in the opinion below (207a).

The Board compared the pupils’ intelligence test and

achievement test scores with the median scores of the

classes they sought to enter, and rejected all pupils who

were not more than slightly above the median score in the

white classes (163a, 170a-173a). The data considered by

the Board indicated the number of I.Q. points each plain

tiff scored above or below the median (see Court’s Exhibit

No. 1, column headed “Deviation from Median I.Q.” ; 117a),

and the achievement scores above or below the median

(see Court’s Exhibit No. 1, column headed “Deviation from

Median Grade Level” ; 118a). The Board had no data

from which it could determine the relative standing of

the Negroes in relation to the white classes except whether

they were in the top or bottom half. Plaintiffs’ expert wit

ness, Dr. Bayton, testified that without knowing more than

a pupil’s score on a test and the median score it would

not be statistically possible to determine his standing in

the class, because a median is a statistic which describes

nothing more about a group other than that half are above

that point and half are below it (94a, 97a-99a). To find

out a pupil’s position in a group it would be necessary to

know at least the “standard deviation” from which it

would be possible to calculate how the individuals are

grouped around the median and thus a given individual’s

position (100a, HOa-llla, 112a). Mr. Wingo acknowledged

that the Board did not have information about the standard

deviation (179a-180a) or any figure to describe the group

ing of pupils around the median, but he stated that he

18

did not “need” that since the Board was concerned only with

whether or not a pupil was above or below the median

(180a-181a). Mr. Wingo explained the Board’s reason for

applying the requirement that transferring students be

above the median to Negroes, but not to whites, as fol

lows (175a-176a):

Q. Well, would you state whether or not it is the

policy of the Board in reviewing applications for

transfer in the cases of both white and colored students

that both categories, in order to get approval on their

transfer, that they should be at least equal or a little

better than the average median of the class they seek

to attend? A. Yes, with one reservation, Your Honor.

In the case of Negroes transferring from, schools that

were Negro schools to predominantly white schools, if

these transfers or these attempts to transfer are ran

domly made, the chances are three out of four that

each one that applies will be below the median for

the white school or predominantly white school to

which he is applying. That is a matter of course, if

they are selected at random—three to four. On the

other hand, if whites are applying for transfer to a

white school, the chances are one in two that they are

below or one in two above. In other words, the thing

becomes an academic situation in the case of the whites.

But in the case of the Negro applying for—to enter

the white school, that difference makes it a statistical

problem.

Q. Then, in that particular category, color does have

a bearing on it? A. I am sorry?

Q. Then, in that particular category, color does in

fact have a bearing on the decision? A. It does inso

far as our concern for scholarship qualifications are

concerned, yes.

19

Q. So, to that extent, there is a different standard

in the case of a white applicant and a colored appli

cant? In other words, he is required to have an aver

age above the median to a greater degree than a white

student would require ? A. Well, the situation is this:

Whites selected randomly for transfers will not change

the picture. Negroes selected randomly, without ap

plication of test scores and academic qualifications,

generally, will lower the standards.

Five pupils were denied transfers on the ground of the

“sibling relationship” criterion. These five pupils had test

scores above the medians but were rejected on the ground

that if they were transferred they would be separated from

their siblings who had scores below the median (178a).

Mrs. Gibboney testified that the local authorities told the

Placement Board that it was inadvisable to separate sib

lings (127a). But Mrs. Gibboney acknowledged that three

of the plaintiffs (pupils Nos. 8, 9 and 13) were siblings in

the second, sixth and seventh grades, respectively, who

were then attending three different all-Negro schools (128a-

131a). Mr. Wingo testified that the Placement Board “gave

some credence” to the Roanoke City policy and was “con

cerned about disrupting the family” (178a). He testified

that the Board was “concerned about the individuals not

being placed in situations that would be educational [ly]

frustrating and upsetting and lead to failures” (179a), and

that while the Board was not sure that the separation

“would necessarily cause harm . . . we just don’t want to

take a chance” (179a).

With regard to the personality or social adjustment cri

terion, Mr. Oglesby testified that the record of teachers’

comments about the pupils was one of the important things

the Board considered in appraising the pupils’ applications

(148a). He said:. “We were trying to get all of the in

2 0

formation we could and we could think of nothing more

important to a clear understanding of our part so we can

do a square job on the thing than what the teachers thought

about the ability of what they could do” (148a). In stating

the reasons for denial of transfers, Mr. Wingo mentioned

this factor only in regard to one pupil whom he mentioned

had “a record of poor adjustment in school” (172a).

Dr. James Bayton, a man with 22 years experience as a

college and university teacher of psychology, having con

siderable additional experience as a psychologist in busi

ness and Government (92a-94a), testified as an expert

witness for plaintiffs.10 He testified that he did not believe

that teachers were competent to make clinical evaluations

of pupils’ personalities such as some of the statements

about the plaintiffs contained in the School Board’s sum

mary sheets (see Court’s Exhibit No. 1); that such teacher

comments as “not well adjusted” and comments on “leader

ship abilities” are not reliable; and that Virginia had a

certification law requiring clinical psychologists to be li

censed to make such judgments (101a-105a). Dr. Bayton

said he knew of no testing that could be done by psycholo

gists which would enable them to predict how a given child

would adjust when placed with a given group of children;

that even if psychologists agreed in evaluating one pupil’s

personality, it would be necessary to know something about

the personalities of the group; and that he knew of no

scientific or other way to determine how an individual will

get along with a group of 30 others (113a-114a).

Dr. Bayton testified that “sibling relationships” were

discussed a great deal in developmental psychology and

in personality theory, particularly with regard to rivalry

10 Mr. Wingo of the Placement Board is not a psychologist. His

graduate training is in education (185a). Mr. Oglesby is a uni

versity mathematics professor (134a).

2 1

between siblings, but that he knew of no accepted theory

or view in psychology that it is bad to separate brothers

and sisters in different schools, and had never heard of

any such thing (105a-106a). He commented: “They are

both likely to be on a different pace, anyway, unless they

are twins. So, they get separated and they get separated

when one goes to junior high school and other is behind”

(106a).

By letters dated August 17 and August 22, respectively,

the Placement Board notified the parents that the transfer

requests had been denied and the Superintendent notified

them of the assignments made (PI. Ex. D; 27a). Neither

letter informed the parents of any reasons for the denials

of transfers. This case was filed on August 20, 1960 (la).

ARGUMENT

T he P u p il A ssignm ent Policies, S tandards and P ro

cedures Used by th e R oanoke City School B oard and the

Pupil P lacem en t B oard A re R acially D iscrim inato ry and

Should Be P ro h ib ited and D eclared Invalid .

A. T he initial assignm ent system and the feeder

system are discrim inatory.

It is readily apparent that initial assignments of pupils

entering the school system are based upon race, as is demon

strated by the completely segregated pattern resulting from

the routine initial assignment policies and procedures. The

“Negro” schools in the City are organized in a separate

“Section II” in the system; all Negroes are routinely as

signed to the schools in Section II, and no white children

are assigned there. No formal rigid school zones are in use.

Elementary schools serve traditionally designated neigh

borhoods. But clearly the segregated pattern of schools

is not entirely the result of residential segregation, for as

plaintiffs’ eases demonstrate (see Court’s Exhibit No. 1),

numbers of Negroes living closer to the all-white and pre

dominantly white schools than to the Negro schools are,

nevertheless, routinely placed in the all-Negro schools.

The feeder system by which, once a Negro pupil enters

an all-Negro school, he is moved to a designated Negro

junior high and high school, similarly regulates assignments

on the basis of race. This assignment system is similar to

that held invalid by this Court in Hill v. School Board of

the City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473, 474 (4th Cir. 1960),

where the Court said, “The concept of moving within a so-

called ‘normal stream’ based upon race can no longer be

availed of in these situations.” The Court went on to com

ment in the Hill case:

However, assignments to the first grade in the pri

mary schools are still on a racial basis, and a pupil

thus assigned to the first grade still is being required

to remain in the school to which he is assigned, unless,

on an individual application, he is reassigned on the

basis of the criteria which are not then applied to

other pupils who do not seek transfers. As we recently

held in Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria,

Virginia, 4 Cir., 278 F. 2d 72, such an arrangement

does not meet the requirements of the law.

It is submitted that the Roanoke City feeder system,

which, admittedly, has continued routine assignments on

the same racial basis used when segregation was compelled

by state law, is invalid. Such racial regulation of school

assignments cannot be justified on the theory that this is

“voluntary” segregation. State officers are supposed to use

non-racial grounds for assigning pupils and not continue to

use race on the presumption that the majority favors segre

gation. A majority desire for segregation cannot justify

state officers’ action in assigning pupils on the basis of race,

23

under Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954)

and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958). The organization

of Negro pupils in a separate all-Negro section of the

school system is obviously not in conformity with the school

authorities’ responsibilities to eliminate school assignments

on a racial basis.

The mechanical arrangement used to accomplish the seg

regated initial assignments, involving the relationship be

tween the local authorities and Pupil Placement Board,

cannot alter the unconstitutionality of the result. The Place

ment Board routinely approves the assignments made by

the local authorities which, as demonstrated, are made on

a racial basis. The fact that the Pupil Placement Board

(which has statutory authority to place pupils) has not

concerned itself with the details of the feeder system, and

merely “rubber stamps” the local recommendations in rou

tine cases, does not insulate either the Placement Board or

the local authorities from accountability for the racial

assignment practices. A similar Placement Board policy of

automatically approving all assignments not involving re

quests for desegregation existed in the Norfolk case as de

scribed by Judge Hoffman in Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 185 F. Supp. 459, 460 (Finding No. 1),

(E. D. Ya. 1959), aff’d sub now,. Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d

131 (4th Cir. 1960). From the standpoint of the Fourteenth

Amendment, all the defendants are State agents and agen

cies, all answerable in law for the product of their discrim

inatory activities, whatever the formalities of the relations

between them. In an analogous situation where one state

agency attempted to excuse its discriminatory conduct on

the basis of interference by another agency, the Supreme

Court rejected the claim, stating in Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U. S. 1, 16:

The situation here is in no different posture because

the members of the School Board and the Superinten-

24

dent of Schools are local officials; from the point of

view of the Fourteenth Amendment, they stand in this

litigation as the agents of the State.

The Court went on to say at 358 U. S. 17:

In short, the constitutional rights of children not to

he discriminated against in school admission on grounds

of race or color declared by this Court in the Brown

case can neither be nullified openly and directly by state

legislators or state executive or judicial officers, nor

nullified indirectly by them through evasive schemes

for segregation whether attempted “ingeniously or

ingenuously.” Smith v. Texas, 311 US 128, 132, 85 L ed

84, 87, 61 S Ct 164.

Thus, both the local and state authorities are legally

accountable for the racial initial assignments and the “nor

mal stream” (or “feeder system” as it is called in Roanoke),

which are invalid under this Court’s decision in Hill v.

School Board of the City of Norfolk, supra.

While the school authorities did begin limited desegre

gation in Roanoke in 1960, without an injunctive order re

quiring it, this limited voluntary compliance with the

requirement of desegregation does not justify approval of

the placement criteria on even an interim basis, as was held

to be appropriate in the Hill case, supra. The Hill case

involved obvious differences in the actual assignment pro

cedures. A further distinction between this case and the

Hill case, is that here neither the trial court nor either of

the defendants has sought to justify the pupil assignment

procedures as a temporary or interim measure or as a part

of a planned program of gradual desegregation. Both de

fendant boards indicated that they had no plans for deseg

regation other than to continue the present procedure in

definitely; they defend it as valid and the court below

agreed.

25

Plaintiffs submit that contrary to defendants’ arguments,

under Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7, school authorities do

have affirmative obligations with respect to desegregation:

It was made plain that delay in any guise in order to

deny the constitutional rights of Negro children could

not be countenanced, and that only a prompt start, dili

gently and earnestly pursued, to eliminate racial segre

gation from the public schools could constitute good

faith compliance. State authorities were thus duty

bound to devote every effort toward initiating desegre

gation and bringing about the elimination of racial

discrimination in the public school system (emphasis

supplied).

The Eighth Circuit has subsequently emphasized the af

firmative obligations of school boards to desegregate. Nor

wood v. Tucker, 287 P. 2d 798, 809 (8th Cir. 1961). That

Court has also made it plain that “subjective good faith” or

a conscientious belief by the authorities that their actions

were proper could not justify the use of discriminatory

pupil assignment procedures. Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d

256, 261 (8th Cir. 1960).

The trial Court’s refusal to grant permanent injunctive

relief prohibiting an indefinite continuation of the assign

ment practices reflected that Court’s view that the proce

dures were nondiscriminatory (210a). The Court took this

view despite the fact that it had found the application of

some of the transfer criteria to be racial discrimination

in individual cases (207a-208a). Plaintiffs urge that the

trial Court should be directed to retain jurisdiction over the

cause in order to supervise and insure the elimination of

the discriminatory initial assignment and transfer prac

tices. Cf. Hill v. School Board of the City of Norfolk,

supra.

26

B. T he defendan ts’ special transfer criteria applied

to Negroes seeking to en ter w hite schools are

discrim inatory.

The record in this case amply demonstrates that the de

fendants nsed special standards and procedures in deter

mining the transfer requests submitted by plaintiffs. The

defendants’ entire approach to the applications of the

39 Negroes who applied to enter white schools in May, 1960

is reflected by Mr. Wingo’s question to the School Super

intendent: “Are there Negro pupils who cannot be excluded

from attending white schools except for race!” (39a).

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit J (200a), the summary sheet used at the

August 15th conference on these applications, demonstrates

that the entire process was a search for reasons to disqualify

applicants. The exhibit indicates that the Board began with

39 applicants and proceeded to subtract applicants as rea

sons for opposing their transfers were agreed upon. The

Placement Board’s minutes also reflected this approach

(28a-29a), stating that the nine Negroes admitted to white

schools were pupils who “the local school authorities are

not in a position to oppose legally” (28a-29a). Thus, the

entire screening process is revealed as a search for grounds

to oppose the transfers rather than an application of pre

viously determined assignment criteria. The lack of any

uniform objective and agreed standards for assigning pupils

was clearly acknowledged by the Placement Board Chair

man (158a-159a).

The transfer criteria applied to the Negro applicants were

special criteria not routinely applied to white pupils rou

tinely admitted to the same schools by operation of the

“feeder system”. The minutes even referred to them as

“criteria and standards dealing with the transfers and

assignments of pupils of different races to the schools” (28a-

29a). The entire procedure was in violation of the prin

27

ciples set forth in Jones v. School Board of the City of

Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960), where the Court

said:

“If the criteria should he applied only to Negroes seek

ing transfer or enrollment in particular schools and not

to white children, then the use of the criteria could not

he sustained. Or, if the criteria are, in the future,

applied only to applications for transfer and not to

applications for initial enrollment by children not pre

viously attending the city’s school system, then such

action would also be subject to attack on constitutional

grounds, for by reason of the existing segregation pat

tern it will be Negro children, primarily, who seek

transfers.”

Mr. Wingo acknowledged that the academic criteria ap

plied to Negro pupils and not to white transfer applicants,

attempting to justify this on the theory that three out

of four Negro pupils were below the median of the white

schools, and it was necessary to screen Negro pupils aca

demically and admit only those significantly above the

median in order not to lower the median in the white schools

(176a). He said that admitting whites to the same schools

at random, would not change the white schools’ median, and

therefore it was not necessary to apply the academic median

criterion to white transfer students (176a). This argument

seeks to justify the Board’s requirement that Negroes be

above the median, that is have academic scores above half

of the white pupils in the class applied for, to be granted

transfers. It is obvious that a rule requiring Negro transfer

applicants to be superior to more than half of the white

students in the class they seek to enter is patently racially

discriminatory. School segregation cannot be justified on

the basis of any theory that Negro pupils as a group have

lower academic test scores than white pupils as a group.

28

Such arguments were made by the states and rejected in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954).

If a school system desired to group pupils by reference

to their academic test scores and established special schools

for pupils with certain academic abilities, there would be

no constitutional objection. However, this has not been

done in the Roanoke schools, as the Superintendent freely

admitted (52a-53a; 56a-57a). Roanoke does have ability

grouping where it is considered necessary within given

schools, but all of the schools accept pupils routinely with

out reference to their academic test scores. They are some

times grouped academically after they are admitted (57a).

All of the plaintiffs were discriminated against by the

application of the academic criterion. No matter how high

or low the individual plaintiffs’ intelligence and achieve

ment test scores (and the Board used no data to find out

exactly where they stood in relation to the white pupils),

the simple fact remains that white pupils were admitted

without reference to such test scores. Nondiscriminatory

treatment requires that Negro applicants similarly be ad

mitted without reference to the academic test scores.

Defendants’ explanations that the academic screening was

done with good motives, out of solicitude for the Negro

pupils themselves and to assure that they would be success

ful if admitted to white schools, cannot justify the dis

criminatory criteria. Similar arguments were rejected in

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256, 258, 8th Cir. (1960) and

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798, 809 (8th Cir. 1961). The

Court said in the Dove case tha t:

“An individual cannot be deprived of the enjoyment

of a constitutional right, because some governmental

organ may believe that it is better for him and for

others that he not have this particular enjoyment. The

29

judgment as to that and the effects upon himself

therefrom are matters for his own responsibility”

(at p. 258).

This Court stated the applicable principles forcefully in

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949, 953-954 (4th Cir.

1951), a case where state officials argued that it would be

to a Negro’s advantage to attend an all-Negro school

rather than the all-white state law school. Judge Soper

writing for the Court said:

“Indeed the defense seeks in part to avoid the charge

of inequality by the paternal suggestion that it would

be beneficial to the colored race in North Carolina as

a whole, and to the individual plaintiff's in particular,

if they would cooperate in promoting the policy

adopted by the State rather than seek the best legal

education which the State provides. The duty of the

federal courts, however, is clear. We must give first

place to the rights of the individual citizen, and when

and where he seeks only equality of treatment before

the law, his suit must prevail. It is for him to decide

in which direction his advantage lies.”

The Supreme Court long ago invalidated State efforts

to over-ride parental decisions as to the best educational

choices to make for their children, stating that:

“The child is not the mere creature of the State; those

who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right,

coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare

him for additional obligations.”

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510, 535 (1925) (in

validating State denial of right to attend private schools).

See also Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390, 401-402 (1923)

(invalidating State prohibition of foreign language instruc

30'

tion). The defendants’ conception that Negro pupils must

bear the burden of demonstrating that obtaining a non-

segregated education will benefit them, advances a unique

proposition in our constitutional law. Professor Charles

L. Black discussed this theory in a recent article, The Law

fulness of the Segregation Decisions, 69 Yale L. J. 421,

428 (1959):

“It is true that the specifically hurtful character of

segregation, as a net matter in the life of each segre

gated individual, may be hard to establish. It seems

enough to say of this, as Professor Poliak has sug

gested, that no such demand is made as to other con

stitutional rights. To have a confession beaten out of

one might in some particular case be the beginning of

a new and better life. To be subjected to a racially

differentiated curfew might be the best thing in the

world for some individual boy. A man might ten years

later go back to thank the policeman who made him

get off the platform and stop making a fool of himself.

Religious persecution proverbially strengthens faith.

We do not ordinarily go that far, or look so narrowly

into the matter. That a practice, on massive historical

evidence and in common sense, has the designed and

generally apprehended effect of putting its victims at

a disadvantage, is enough for law. At least it always

has been enough.

“I can heartily concur in the judgment that segregation

harms the white as much as it does the Negro. Sadism

rots the policeman; the suppressor of thought loses

light; the community that forms into a mob, and goes

down and dominates a trial, may wound itself beyond

healing. Can this reciprocity of hurt, this fated mutu

ality that inheres in all inflicted wrong, serve to vali

date the wrong itself?” (Footnotes omitted.)

31

The “sibling relationship” criterion as applied by the

defendants to deny plaintiffs’ transfer request is equally

invidious and discriminatory. This criterion was sought

to be justified by Mr. Wingo on grounds similar to those

just mentioned, namely, as an attempt to protect plaintiffs

from being in frustrating situations (178a-179a). Mr. Wingo

said he was concerned about disrupting the families by

putting siblings in different schools (178a), and also that

where one sibling had an academic record below the median,

he considered this an indication that the other children in

the family might have difficulty succeeding academically,

saying: “Generally speaking, the children in a family will

be more or less alike” (166a). Thus, by this criterion, pupils

were excluded, despite their own test scores above the

median, on the ground that they had siblings who were

below the median.

If the academic median criterion is held to be discrimina

tory, the sibling relationship criterion must naturally fail

as it depends entirely upon the validity of the academic

criterion. In other words, if no pupils can be excluded for

a score below the median, their siblings (who also applied

for transfers) would not be separated from them. The

sibling relationship criterion would be inoperative. There

is no need here to decide whether school authorities might

use another type of sibling relationship rule unrelated to

a discriminatory acadamic standard. The court need not

consider, for example, whether a board might validly make

it a condition that all pupils in a family at a given school

level seek transfers together. That situation was not in

volved here. Here several siblings sought transfers to

gether. When some pupils were excluded from white

schools by the discriminatory academic ground, the Board

required that their siblings be excluded with them. This

Court’s decisions in Jones v. School Board of the City of

Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960); Dodson v. School

32

Board of the City of Charlottesville, 289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir.

1961) and Hamm v. County School Board of Arlington

County, 264 F. 2d 945 (4th Cir. 1959), indicate that such

applications of assignment criteria are invalid.

The Board’s residence criterion was also applied in a

discriminatory manner. Negro transfer applicants were ex

cluded if they lived closer to the all-Negro schools than to

the all-white schools or an equal distance between schools.

However, Negro pupils living closer to the all-white schools

were not required to attend those schools because they

lived closer to them. To the contrary, Negroes living with

in one block of white schools and twenty blocks from all-

Negro schools were not only initially assigned to the all-

Negro schools—they were not even permitted to transfer

to the white schools (133a). Thus, it is plain that a differ

ent residence criterion has been used in determining trans

fer applications from the method used in deciding initial

assignments. This also falls within the rule of the Jones

case, supra, prohibiting the use of special criteria for trans

fers not used in original placements. See also, Norwood

v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798, 803 (8th Cir. 1961), and Mannings

v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370, 374 (5th Cir.

1960).

The screening of pupils on the basis of teacher’s com

ments about their personalities and school adjustment was

another special criterion applied only in the case of the

Negro transfer applicants. Similar subjective standards,

sometimes referred to as “adaptability” criteria, were re

jected in Hamm, v. County School Board of Arlington

County, 263 F. 2d 226 (4th Cir. 1959) and School Board

of the City of Norfolk v. Beckett, 280 F. 2d 18, 19 (4th Cir.

1958). It is clear that no personality appraisals are used

in the routine initial assignments of pupils. Use of this

standard in screening the plaintiffs was discriminatory.

33

C. T h e Placem ent B oard’s pro test and hearing p ro

cedure was not an adequate and expeditious

rem edy.

The court below held that plaintiffs’ failure to file a

protest with the Placement Board after their applications

were denied did not bar them from obtaining judicial relief

because of the circumstance that the Placement Board did

not act on the applications until shortly prior to the school

term and there was “insufficient time to have heard the

protest if one had been filed” (206a). Plaintiffs submit that

this ruling was correct in the circumstances of the case.

The statute relied upon by defendants (Va. Code §22-232.8)

requires a substantial period of time before a hearing can

be held and the Board is allowed thirty (30) days after

the hearing to decide the ease. Numerous courts have held

that the procedure provided by §22-232.8 was inadequate:

Judge Hoffman’s holding in Beckett v. School Board of

City of Norfolk, 185 F. Supp. 459 (E. I). Va. 1959), aff’d

sub nom. Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960),

while relying in part on the Placement Board’s fixed oppo

sition to desegregation, was also based upon a determina

tion that the remedy was inadequate since the Placement

Board had not acted upon the applications until three days

prior to the school term and the protest procedures required

so much time.

Prior to the Beckett case, Judge Bryan had reached a

similar conclusion on several occasions in the Thompson

case, infra. None of the Negro pupils who obtained ad

mission to white schools during the several years such

orders were issued in Arlington were required to follow

the protest machinery. This was true both before and

after the Placement Act amendments of 1958. Compare

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington County,

159 F. Supp. 567 (E. D. Va. 1957) (procedure is “too

34

sluggish and prolix”), aff’d 252 F. 2d 929 (4th Cir. 1957),

cert, denied 356 U. S. 958, and Aclhins v. School Board of

City of Newport News, 148 F. Supp. 430, 442-443 (E. D.

Va. 1957), aff’d 246 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1957), with Thomp

son v. County School Board of Arlington County, 166

F. Supp. 529, 531 (E. D. Va. 1958) (after amendment to

present form, Placement Law held “still not expeditious”),

aff’d in part and remanded in part, sub nom. Hamm v.

County School Board of Arlington County, 263 F. 2d 226

and 264 F. 2d 945 (4th Cir. 1959). Judge Brya.n rejected

the protest machinery as inadequate once more after the

invalidation of the massive resistance laws. Thompson v.

County School Board of Arlington County (E. D. Va.,

C. A. No. 1341, unreported “Memorandum on Formulation

of Decree on Mandate” dated June 3, 1959), holding that

Negro pupils could ignore the protest machinery because

it still was not expeditious.

The simple fact is that none of the dozens of Negro

pupils who obtained admission to white schools by court

orders in the Arlington County case,11 12 13 Fairfax County f 2

or Alexandria13 school segregation cases were required to

pursue the Placement Board’s protest machinery.

There were similar rulings in the Charlottesville and

Floyd County cases by Judges Paul and Thompson, Allen

v. School Board of City of Charlottesville, 3 Race Rela

tions Law Reporter 937, 938 (W. D. Va. 1958); Walker

11 See for example Thompson v. County School Board, etc., 4

Race Rel. Law R. 609 (E. D. Va. July 25, 1959) ; 4 Race Rel. Law

R, 880 (E. D. Va. Sept. 1959); 5 Race Rel. Law R. 1054 (E. D. Va.

Sept. 16, 1960).

12 Blackwell v. Fairfax County School Board, 5 Race Rel. Law R.

1056 (E. D. Va. Sept. 22, 1960).

13 Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 4 Race Rel. Law

R. 31, 33 (E. D. Va. Oct. 22, 1958; Jan. 23, 1959; Feb. 6, 1959);

aff’d 278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ; see also 179 F. Supp. 280

(E. D. Va. 1959).

35

v. Floyd County School Board (W. D. Va., C. A. No. 1012;

Sept. 23,1959, unreported).

Plaintiffs submit that the remedy provided by this sec

tion is inadequate for a more fundamental reason than

the time element involved in exhausting it. So long as the

practice of initial assigning standards on the basis of race

continues, it is discriminatory to require that students seek

ing to obtain a desegregated assignment pursue a protest

and hearing procedure. This is particularly true where

the protest proceedings are not designed to correct the

practice of assigning pupils on the basis of race but in

volve merely the application of special criteria for pro

tested cases (the same criteria already applied ex parte

in this case). In light of the Placement Board’s policy of

using different assignment criteria to review protested

transfer applications than the criteria used to place pupils

initially, the entire protest procedure is necessarily dis

criminatory within the rule of Jones v. School Board of

the City of Alexandria, supra.

District Judge Michie recently wrote in Jackson v. School

Board of the City of Lynchburg, Va. (W. D. Va., C. A.

No. 534, January 15, 1962, not yet reported):

If the Pupil Placement Board is not going to make

the initial placements of all public school students in

the state (and, as indicated above, it obviously cannot)

and if on appeal it is not going to consider whether

or not those placements have been made on a dis

criminatory and racial basis, then obviously the ap

peal to the Pupil Placement Board can afford no ade

quate remedy to those children who have been

discriminated against because of their race unless per

chance they happen to live nearer to the school they

. wish to attend. Under these circumstances it would

be almost a cruel joke to say that administrative reme

36

dies must be exhausted when it is known that such

exhaustion of remedies will not terminate the pattern

of racial assignment but will lead to a remedy only

in a few given cases based on geography—a considera

tion which has been disregarded in the assignment of

white pupils.

D. T he court has clear pow er to grant com plete re lief

by issuing an order restraining the discrim inatory

initial assignm ent practices.

The court below refused to issue an injunction against

the defendants as prayed,14 holding that the Placement