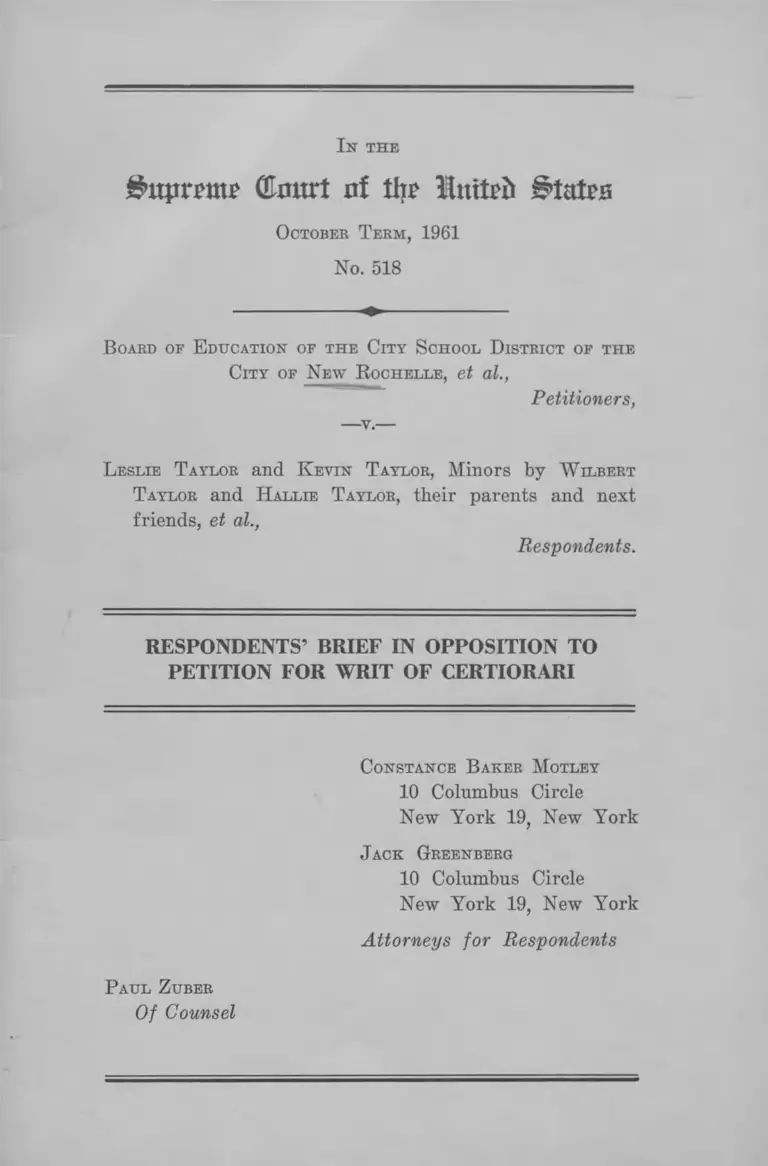

City of New Rochelle Board of Education v. Taylor Respondents' Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of New Rochelle Board of Education v. Taylor Respondents' Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1961. 0e0be16a-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aa84eee4-191f-442f-af95-471d98a93913/city-of-new-rochelle-board-of-education-v-taylor-respondents-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Supreme GJourt of the llutteh States

October T erm, 1961

No. 518

B oard of E ducation of the City S chool D istrict of the

City of New R ochelle, et al.,

Petitioners,

-v -

L eslie T aylor and K evin T aylor, Minors by W ilbert

T aylor and H allie T aylor, their parents and next

friends, et al.,

Respondents.

RESPONDENTS’ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Constance Baker M otley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Respondents

Paul Z uber

Of Counsel

I N D E X

S ubject I ndex

page

Opinions Below ................................................................. 1

Question Presented ........................................................... 2

Constitutional Provisions Involved .............................. 2

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 2

A bgument :

I. The petition for writ of certiorari raises

questions of fact which have been decided

adversely to petitioners by two courts........... 7

II. This Court’s decisions in the school segrega

tion cases apply to all state perpetuated ra

cial segregation in the public schools ............ 10

Conclusion ..................................................................................... 13

T able of Cases

Board of Education of the City School District of the

City of New Rochelle, et al. v. Taylor, et al., ------

U. S . ------ , 30 L. W. 2114.............................................. 7

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ............. 9

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

483 (1954) ................................................................... 2,9,10

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S.

294 (1955) ..................................................................2,10,12

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) .....................2, 9,10,12

11

PAGE

General Talking Pictures Corp. v. Western Electric

Co., 304 U. S. 175 (1938) .............................................. 9

Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co.,

336 U. S. 271 (1949) ..................................................... 9

McEwan v. Brod, 91 N. Y. Supp. 2d 565 (1949) ....... 5

McEwan v. Brod, 97 N. Y. Supp. 2d 917 (1950) ....... 5

Taylor, et al. v. Board of Education of the City School

District of the City of New Rochelle, et al., 294

F. 2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961) ..........................................1,4,6

Taylor, et al. v. Board of Education of the City School

District of the City of New Rochelle, et al., 288

F. 2d 600 (2nd Cir. 1961) ............................................ 3

Taylor, et al. v. Board of Education of the City School

District of the City of New Rochelle, et al., 191

F. Supp. 181 (S. D. N. Y. 1961) ............................ 3,10,12

Taylor, et al. v. Board of Education of the City School

District of the City of New Rochelle, et al., 195

F. Supp. 231 (S. D. N. Y. 1961) .......................... 1, 3, 6,11

In t h e

*$>upr£m? (flflurt nf tljp States

October T erm, 1961

No. 518

B oard of E ducation of the City School D istrict of the

City of New R ochelle, et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

L eslie T aylor and K evin T aylor, Minors by W ilbert

T aylor and H allie T aylor, their parents and next

friends, et al.,

Respondents.

RESPONDENTS’ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals,

Second Circuit, is now reported. Taylor, et al. v. Board

of Education of the City School District of the City of

New Rochelle, et al., 294 F. 2d 36 (1961).

The opinion of the District Court dealing with the plan

is also now reported. Taylor, et al. v. Board of Education

of the City School District of the City of New Rochelle,

et al., 195 F. Supp. 231 (S. D. N. Y. 1961). The first

opinion of the District Court is cited in the Petition.

2

Question Presented

Whether where the two courts below held that segrega

tion at the Lincoln School was not a fortuity but was de

liberately created and maintained by petitioner-school au

thorities, principles enunciated by this Court in Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954),

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294

(1955), and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7 (1958) were

properly applied?

The Constitutional Provisions Involved

This case involves the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Statement of the Case

Petitioners seek review of the judgment of the United

States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, affirming the

judgments of the United States District Court, Southern

District, New York, which, relying primarily upon Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954),

held that rights secured to infant respondents by the

equal protection clause had been violated by petitioners in

requiring respondents to attend the Lincoln elementary

school in the City of New Kochelle.

The District Court’s holding was based upon two prin

cipal findings: (1) petitioners had, prior to 1949, inten

tionally created Lincoln School as a racially segregated

school, and had not since then acted in good faith to achieve

desegregation as required by the Fourteenth Amendment;

and (2) petitioners’ conduct, since 1949, had been moti

vated by the purposeful desire to maintain the Lincoln

School as a racially segregated school.

3

These principal findings, affirmed by the court below, were

supported by numerous more detailed findings in the first

trial court opinion which, together with that court’s hold

ing, formed the basis of a decree entered by it on Janu

ary 24, 1961, suggesting that petitioners submit a plan,

by April 14, 1961, for desegregating the Lincoln School,

commencing with the 1961-62 school year. Taylor, et al.

v. Board of Education of the City School District of the

City of New Rochelle, et al., 191 F. Supp. 181 (S. D. N. Y.

1961).

Petitioners appealed to the court below from this decree.

Their appeal was dismissed as premature on April 13,

1961. Taylor, et al. v. Board of Education of the City

School District of the City of New Rochelle, et al., 288 F. 2d

600 (2nd Cir. 1961).

Thereafter, on May 3, 1961, pursuant to an extension

of time granted by the court below, plans were presented

to the trial court. The plan of the majority of petitioner

board provided for voluntary transfer of children re

siding in the Lincoln School attendance area to any of the

other eleven elementary schools in New Rochelle upon ful

fillment of a number of conditions precedent. Most of these

prerequisites were stricken by the court, for reasons set

forth in its second opinion, and a decree was entered by it

on May 31, 1961 directing implementation of the plan as

judicially amended. Taylor, et al. v. Board of Education

of the City School District of the City of New Rochelle,

et al., 195 F. Supp. 231 (S. D. N. Y. 1961). A plan of the

board minority also was proffered.1

1 The minority plan also embodied a permissive transfer provi

sion for grades kindergarten through three but did not attach the

majority’s numerous conditions. It provided for dispersal of grades

four through six among other neighboring schools and for re

building the Lincoln School on another site by 1964.

4

Petitioners again appealed to the court below. This

time their appeal was heard on the merits and the judg

ments of the trial court affirmed on August 2, 1961, one

judge dissenting.

In affirming, the Court of Appeals ruled: “ A major

finding of the court below was that the defendant School

Board had deliberately created and maintained Lincoln

School as a racially segregated school. This crucial find

ing is, we conclude, supported by the record” (294 F. 2d

at 38).

Succinctly, the facts of record upon which the major

findings depend are:

1. In 1930, when the Webster School was opened, the

district lines were gerrymandered to include white

pupils in Webster who had been and who normally

would have attended Lincoln. As Negroes moved

into this area which had been included in the

AVebster district, the area was restored to the

Lincoln district. Later, pupils in the predominantly

white Bochelle Park area in the Lincoln district

were assigned to the Mayflower School (Appellees’

App. pp. 5b-9b).2

2. In conjunction with the policy of manipulating the

district lines so that as few whites as possible

would have to attend Lincoln, school authorities

permitted white children living in the Lincoln dis

trict to transfer freely to other schools, so that by

1949, the Lincoln School was 100% Negro (Appel

lees’ App. pp. 9b-12b, 65b, 73b).

2 “Appellees’ A pp .” refers to appendix to appellees’ brief below

which is part of record sent to this Court in support of petition

for writ of certiorari.

5

3. As a result of pressures exerted by community

groups, the Board, on January 11, 1949, resolved

to “ study present district lines with a view to

setting up school districts in terms of the best in

terests of all the children and of the most complete

utilization of the present physical plant” 3 (Appel

lants’ App. pp. 67a-68a).4 The resolution also pro

vided, “ That as of September 1, 1949, district lines

as set by the Board will be strictly adhered to ac

cording to best educational practices,” and “ That

effective at once all new entrants to the school

system be admitted only to the school of the dis

trict in which they legally reside.” As a result,

a few whites returned to Lincoln.5 The enrollment

there is now 94% Negro.

4. Thereafter, from 1949 to 1960, petitioners studied

the Lincoln School problem (Appellants’ App. pp.

72a-85a). They hired many specialists who made

recommendations, but petitioners never took any

action (Appellees’ App. pp. 52b-53b, 65b-66b). In

1957 the Board proposed to rebuild Lincoln, which

now is delapidated, on the same site without chang

ing the lines or allowing transfers out, contrary to

recommendations of specialists which the Board

had employed. This proposal was defeated in 1957

by referendum (Appellants’ App. p. 77a).

3 Resolution of January 11, 1949 is reprinted as Appendix D

to Petition for W rit of Certiorari, App. p. 43.

4 “Appellants’ A pp .” refers to appendix to appellants’ brief in

the court below which has been sent up to this Court as part of

record in support of petition for writ of certiorari.

5 Some white parents whose children were affected sought, un

successfully, to enjoin enforcement of the resolution on the ground

that the Lincoln School curriculum was inferior. McEwan v. Brod,

91 N .Y . Supp. 2d 565 (1949), 97 N .Y . Supp. 2d 917 (1950).

6

5. In 1959, the Board again proposed to rebuild

Lincoln on the same site. This time, however, it

proposed to build a smaller school, i.e., a school to

accommodate only 400 pupils—Lincoln’s present

enrollment is 483—and to distribute all those in

excess of capacity presently enrolled or to be en

rolled among other adjacent schools, contrary to

petitioners’ own neighborhood school policy which

they claim is violated by the trial court’s order.

This proposal was approved in a special referen

dum in May 1960 (Appellants’ App. pp. 86a-95a,

98a).

6. In the 1960 referendum campaign, the issue, as

defined by school personnel, was whether Lincoln

should be continued as the City’s segregated school

or whether all the children assigned thereto should

be dispersed among adjacent schools—destroy

ing the “ integrated balance” in those schools (Ap

pellees’ App. pp. 32b-52b, 64b).

The desegregation plan as amended by the trial court is

set forth in its second decree (195 F. Supp. at 240). It

was praised below as “ noteworthy for its moderation”

(294 F. 2d at 39) and has been in effect since September

1961.

Stay pending appeal of the order requiring implementa

tion of the plan was denied by the trial court (195 F. Supp.

at 238) and by the Court of Appeals (294 F. 2d at 40).

A stay of the mandate of the Court of Appeals was denied

by it pending petition for writ of certiorari to this Court

on August 17, 1961, one judge dissenting. Taylor, et al.

v. Board of Education of the City School District of the

City of New Rochelle, et al., No. 427, Docket 27055. A stay

of the mandate was also denied by Mr. Justice Brennan

7

on August 30, 1961. Board of Education of the City

School District of the City of New Rochelle, et al. v.

Taylor, et al.,------U. S . ------- , 30 L. W. 2114.

A R G U M E N T

I.

The petition for writ of certiorari raises questions of

fact which have been decided adversely to petitioners by

two courts.

Petitioners seek to have this Court review and set aside

the findings of the courts below that the Lincoln School

segregation results from the deliberate acts of petitioners

and not from happenstance.

The first question presented confirms this: “ Is This

Truly a Segregation Case and Have Plaintiffs Been De

prived of a Constitutional Right?” (Petition p. 2). For

this Court to answer this question in the negative this

Court would have to review and hold clearly erroneous

the crucial constitutionally relevant findings of fact de

cided adversely to petitioners by both courts below.

Again, petitioners say (Petition p. 21) “ Education in

New Rochelle is offered on a non-discriminatory basis,

and Exhibit M proves it mathematically (App. F ).” Ex

hibit M is a chart showing enrollment in the New Rochelle

schools. In the last column of this chart, the non-white

percent of the total enrollment of each school is shown.

These non-white percentages range from .25% in the Ward

School to 94% in the Lincoln School. Petitioners insist,

contrary to the consecutive findings below, that this chart

proves there is no racial discrimination in the New Ro

chelle public school system. Petitioners argue that Lincoln

8

is 94% non-white as a result of the preponderance of

Negroes in the area and the election of eligible -white pupils

in the district to attend private or parochial schools, not

a consequence of action taken by petitioners since 1949.

They contend that since there has been no officially im

posed segregation in New Rochelle since 1949, this case

involves simply the validity of a pupil assignment regula

tion, rigidly adhered to since 1949 and reinstituted by peti

tioners for the purpose of desegregating Lincoln which,

at that time, was 100% Negro. Petitioners then urge that

the decisions below must rest solely upon the fact that

30 years ago the Lincoln district was created as a segre

gated district and not on any proof or finding that since

1949 petitioners’ conduct has been unconstitutional.

What petitioners overlook, however, is the fact that by

1949, as a result of their actions, the Lincoln School had

become firmly established in the community as The Negro

School; that in January 1949 they promised not only

rigid adherence to the pupil assignment regulation but a

redistricting by September 1, 1949; that from 1949-1960

the promise with respect to redistricting was never ful

filled, despite recommendations for remedying the Lincoln

School situation made by Board employed specialists; that

in 1960, when the referendum issue was clearly whether

Lincoln should be rebuilt on the same site, and admittedly

perpetuated as a segregated school, or the children there

attending distributed among adjacent schools, thereby in

creasing the non-white proportions in these schools, peti

tioners determined to perpetuate the racial situation at

Lincoln so that racial balances in neighboring schools not

be upset.6 This determination, made in 1959-1960, and

based wholly upon race and color, is constitutionally in

6 Appellees’ App. pp. 63b-64b, 65b-66b.

9

valid. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra;

Cooper v. Aaron, supra, at 7. School authorities may not

make decisions which would tend to perpetuate segrega

tion. Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) (see

particularly supplemental opinion at p. 47).

The decisions below, therefore, do not rest solely upon

a finding that in 1930 the Board created a segregated

school in New Bochelle. The decisions below are also

predicated upon a finding that in 1960 petitioners had an

opportunity to choose between segregation and desegrega

tion and chose the former, and, as a palliative, proposed

to reduce the capacity of the new Lincoln to 400 and to

disperse the excess number of pupils enrolled in Lincoln

among other schools in violation of petitioners’ own “ sac

rosanct” neighborhood school policy.

Consequently, in order for this Court to reach the con

clusion which petitioners desire with respect to the first

question, this Court would have to set aside these findings

of the two lower courts.

This Court has consistently ruled that a petition for

writ of certiorari will not he granted merely to review the

evidence or inferences drawn therefrom, General Talking

Pictures Corp. v. Western Electric Co., 304 U. S. 175

(1938), or to permit this Court to review facts found by

two lower federal courts. Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v.

Linde Air Products Co., 336 U. S. 271 (1949).

10

n.

This Court’s decisions in the school segregation cases

apply to all state perpetuated racial segregation in the

public schools.

In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483

(1954), this Court held officially enforced and officially per

mitted segregation in the public schools unconstitutional.

This holding was reaffirmed in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294 (1955), and in Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958).

Eelying primarily upon these decisions, the trial court

held that, under the facts in this case, rights secured to

infant respondents by the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment were being violated by petitioners’

requirement that these respondents continue to attend

Lincoln School.

The District Court found:

(1) that the Board of Education of New Bochelle,

prior to 1949, intentionally created Lincoln School as

a racially segregated school, and has not, since then,

acted in good faith to implement desegregation as re

quired by the Fourteenth Amendment; and (2) that

the conduct of the Board of Education even since 1949

has been motivated by the purposeful desire of main

taining the Lincoln School as a racially segregated

school (191 F. Supp. 181, 183).

Having found these facts, the District Court clearly had

no alternative but to apply this Court’s teaching in Brown.

In its second opinion, the trial court held: “It must

again be emphasized that the segregation at the Lincoln

11

School was not a fortuity; it was deliberately created and

maintained by Board conduct.” 195 F. Supp. supra at 233.

In affirming, the Court of Appeals held “ The facts recited

above showing the Board’s acceleration of segregation at

Lincoln up to 1949 and its actions since then amounting

only to a perpetuation and a freezing in of this condition

negate the argument that the present situation in Lincoln

School is only the ‘chance’ or ‘inevitable’ result of apply

ing a neighborhood school policy to a community where

residential patterns show a racial imbalance” (294 F. 2d

at 39).

Petitioners argue that this Court should review this

case because the complaint attacked the neighborhood

school policy. However, it should be noted that petitioners

carefully avoid the claim that the trial court held the

neighborhood school policy unconstitutional. That the

complaint may have sought to have the neighborhood

school policy declared unconstitutional is not a reason for

granting certiorari. The controlling consideration is that

the trial court expressly did not hold the neighborhood

school policy, as such, unconstitutional. On March 11,

1961, the trial court said:

Furthermore, there have been many misconcep

tions, which I believe in some instances were deliber

ate, as to the extent of my ruling which have oper

ated to obscure the essential issues involved. For

example, I have seen statements that I had in effect

abolished the neighborhood school policy. If one reads

my opinion, it will be readily apparent that I decided

nothing of the sort. Indeed, to characterize the opin

ion in this manner is a distortion. I did not strike

down the neighborhood school policy for the concept

of the neighborhood school as an abstract proposition

was not even being questioned. But I feel that the com

12

munity has been deliberately confused by these mis

interpretations of the opinion. I did bold that

this policy, lawful though it be, “ is not sacrosanct.

It is valid only insofar as it is operated within the

confines established by the Constitution. It cannot be

used as an instrument to confine Negroes within an

area artificially delineated in the first instance by

official acts” (Appellants’ App. pp. 167a-168a).

In suggesting that petitioners submit a plan, the trial

court was guided by this Court’s instructions in Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294 (1955), re

iterated in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7 (1958). The

plan, submitted by the majority of the members of peti

tioner board, provides for voluntary transfer of pupils

from Lincoln to other schools in accordance with terms

of the trial court’s decree. It does not, as contended by

petitioners, enjoin them from rebuilding the Lincoln

School or taking any other action designed to bring their

operations in line with constitutional requirements.

As the trial court pointed out, the plan adopted will

not solve all problems, “ But inability to find a perfect

answer is hardly justification for refusal to do anything.

. . . It hardly need be stated that there is never an ideal

solution when the question of desegregation is faced

squarely. Experience in the south has made clear, that

the problems to be met in this area are most difficult and

delicate. . . . Therefore, there can never be a solution

which could conceivably please everyone. But, if this alone

were sufficient to excuse inaction, progress in this vital

area of human rights would be nonexistent . . . ” (191 F.

Supp. 181, 193).

The plan has been in operation since September 1961.

The infant respondents, and others similarly situated,

13

have transferred to other schools in New Rochelle in ac

cordance with the terms of the decree. To require them

to continue to attend Lincoln, against the background of

all the facts in this case, would, as the Court of Appeals

held, closely approximate the harmful conditions con

demned in the Brown case.

CONCLUSION

For all of the foregoing reasons, the petition for writ

of certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Constance B aker Motley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Respondents

Paul Z uber

Of Counsel

38