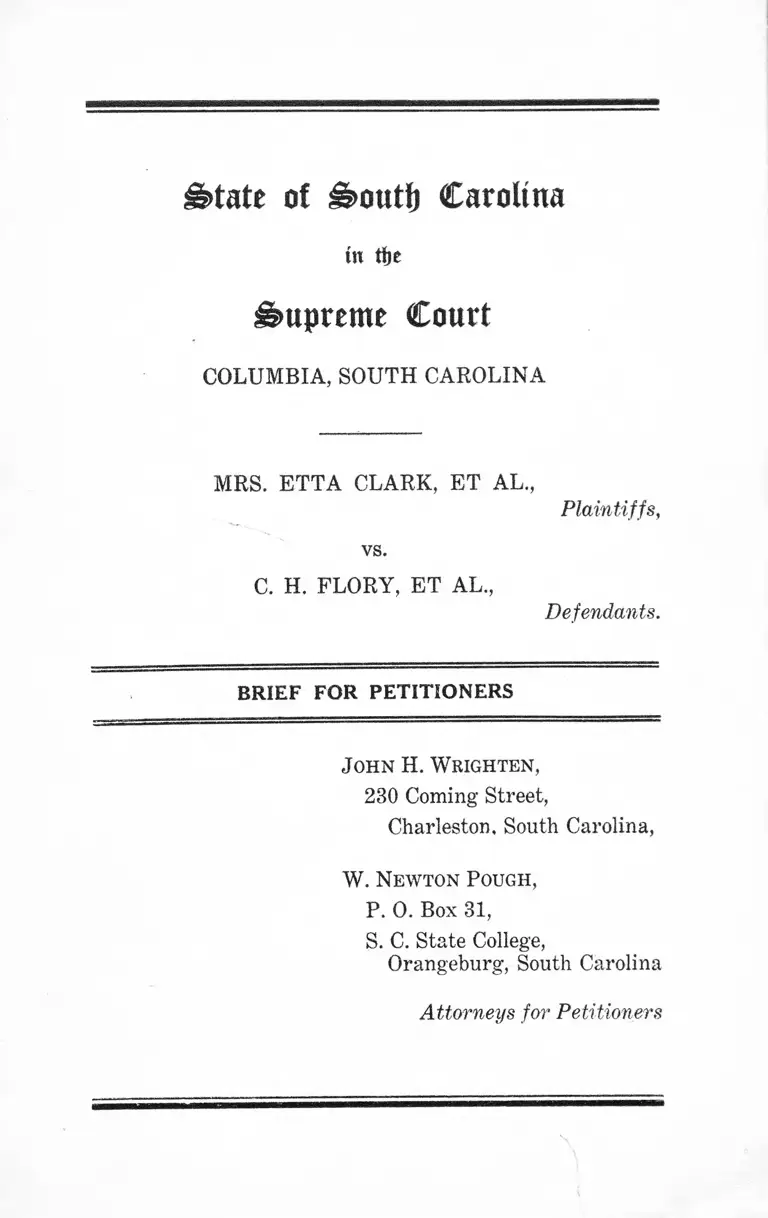

Clark v. Flory Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clark v. Flory Brief for Petitioners, 1956. fbeb6d0b-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aabe339f-ac79-4eaa-bc31-c030c95f566e/clark-v-flory-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

£§>tate of Carolina

in ttje

Supreme Court

COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA

MRS. ETTA CLARK, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

C. H. FLORY, ET AL.,

Defendants.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

John H. W righten,

230 Coming Street,

Charleston, South Carolina,

W. Newton Pough,

P. 0 . Box 31,

S. C. State College,

Orangeburg, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Statement .................

Statutes Involved....

Questions Presented

Argument.................

Conclusion ..............

Index to Cases ........

PAGE

la

2a

3 a

4a tO' 8a

9a

.10a

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

STATEMENT

Petitioners are Negro Citizens of the County of Charles

ton, State of South Carolina and citizens of the United

States of America, brought an action in the Federal Dis

trict Court, the Eastern District of South Carolina, Char

leston Division, for the use of the Edisto State Park Beach,

Edisto Island, Charleston County. The same was brought

against C. H. Flory, et al., and the State Commission of

Forestry, Defendants named herein. The Petitioners’ Com

plaint alleges that the denial by the Defendants of the

Petitioners, the use of the Edisto State Park Beach is

unconstitutional and discriminatory; which denied them

of their constitutional rights as citizens of Charleston

County, State of South Carolina and the United States of

America. Under the laws of South Carolina, Section 51-

181 through 51-184 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina,

1952, segregation of the races at the Edisto State Park

Beach is required, and violators are subject to fine, there

fore, the Petitioners brought this action in this Honorable

Court for the interpretation of Section 51-181 through

51-184. The same is believed by the Petitioners, to be

unconstitutional, based on the 14th Amendment, United

States Constitution and Article 1, Section 5 of the Consti

tution of South Carolina.

2a

STATUTES INVOLVED

SECTIONS:

51-181— Joint use prohibited in Cities over 60,000, 1930

census.

51-182— Posting of signs required.

51-183— Unlawful to use contrary to posting.

51-184— Penalties.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether or not Sections: 51-181, 51-182, 51-183 and

51-184 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina, and the

policy, custom and practice of the Defendants under au

thority and color of said statutes, and otherwise, in deny

ing on account of race and color to Petitioners and other

Negro Citizens similarly situated, rights and privileges of

attending and making use of the bathing beach and bath

house facilities at the Edisto State Park Beach, are repug

nant to the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitu

tion and Article 1, Section 5 of the Constitution of South

Carolina?

2. Whether or not Sections: 51-181, 51-182, 51-183 and

51-184 are repugnant to Article 3 of the Constitution of

South Carolina Section 34, Paragraph 9?

3. Whether or not Sections: 51-181, 51-182, 51-183 and

51-184, violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th

Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article

1, Section 5 of the Constitution of South Carolina?

4. Whether or not Sections: 51-181, 51-182, 51-183 and

51-184, are violative of the Due Process of Law under the

5th Amendment of the United States Constitution and the

Constitution of South Carolina, Article 1, Section 5?

4a

ARGUMENT

I

Our view is that on the authority of the McLaurin vs.

Okla., State Regents, 339 U.S. 637, the Supreme Court

had held that it was a denial of the equal protection guar

anteed by the 14th Amendment for a State to segregate

on the grounds of race, a student who had been admitted

to an institution of higher learning. We feel that based on

authority cited, the denial of the defendants in admitting

the Colored People to the use of the Edisto State Park

Beach is also a denial of the Equal Protection Clause of the

14th Amendment and also a denial of their rights under

the Constitution of South Carolina as cited.

If a State cannot segregate at Colleges and Universities,

where individuals must come into close contact of necessity,

then it cannot segregate at bathing beaches where coming

into contact is optional.

II

Article 4, Section 51-181 of the 1952, Code of Laws of

South Carolina provides that “Joint use prohibited in Cities

over 60,000, 1930 census,” under the heading, “ Use of

certain parks, etc., White and Colored Races jointly pro

hibited.”

The title of the Acts in question specifies its purpose to

be that of separating the Races in joint use of public parks,

etc., yet while at the same time it only excluded the joint

use of public parks in certain areas, while in other areas

there is no such restriction.

5a

Moreover, the provisions of the act make its applicable

use to about three Counties, at present, and when it was

passed by the Legislature or General Assembly in 1935, its

application was directed to Charleston County; for at that

time Charleston was the only County that had a City in it

with a population of 60,000 people, based on the 1930 cen

sus; therefore, not only do we believe that the aforemen

tioned Statutes discriminate against them as taxpayers and

Citizens, both White and Colored, in the State of South

Carolina, but that the said Statutes are Special in nature,

and that the passage of these Statutes on the part of

the General Assembly violated the very thing that the

Constitution was designed to prevent.

Many cases analogous to the present have been decided

by this Honorable Court. Thus, it has been held that the

purpose of Article 3, Section 34, Paragraph 9 of the Con

stitution of South Carolina, “ is to make uniform the Stat

utes of like subject” , Carroll vs. Town of York, 109 S. C.

1, 95 S.E. 121.

In Webster vs. Williams, 183 S. C. 368, 191 S. E. 51, 111

A.L.R. 1348, a special act was condemned in which an at

tempt was made to increase the penalty upon delinquent

taxes in a single County despite a general law thereabout.

Further, this Court has held that where a general law

can be had on a subject special Statute on the subject will

be declared null and void.

In Gaud vs. Walker, 53 S.E. 2d 316, 214 S. C. 451, it was

said that; “ under constitutional provision the General As

sembly is to provide by general laws for organization and

classification of municipal corporations, with powers of

6a

each class to be defined so that no such corporation has

powers or is subject to restriction other than all other

corporations of the same class, the police power cannot be

delegated as to one town or city and withheld as to others.”

AS TO SPECIAL LAWS:

Under the constitutional provision that no special law

shall be enacted where a general law can be made appli

cable, acts imposing one-year limitation on action by State

or City officer or employee for salary, fees, or other obli

gation of service, or six months limitation if cause of action

assured prior to effective date of act, which act does not

apply to Counties having a population of over 85,000, is

unconstitutional as a whole and cannot be sustained in part

by striking out provisions making act applicable as to such

Counties. Gillespie vs. Pickens County, 14 S.E. 2d 900, 197,

S. C. 217.

Legislative discretion in enacting special laws cannot be

extended beyond limits marked out in organic law. Sirrin

vs. State, 128 S.E. 172, 132 S. C. 241.

Under constitutional provisions limiting purpose of local

or special laws, Legislature cannot adopt a mere arbitrary

classification to apply different rules to different subjects.

Thomas vs. Macklen, 195 S.E. 539, 186 S. C. 290.

A law is general in the constitutional sense if applicable

uniformly to all members of any class of persons, places,

or things requiring peculiar legislation in matters covered

by it; “ General Law.” McKiever vs. City of Sumter, 135

S.E. 60, 137 S. C. 266.

Constitutional inhibition against special law, where gen

7a

eral law can be made applicable, prohibits enactment of

special laws relating to a particular county, no particular

local conditions require special treatment, and statute of

State-wide operation on the subject is in force. Webster

vs. Williams, 191 S.E. 51, 183 S. C. 368, 111 A.L.R. 1348.

We think that the leading case on the subject of special

and general law and the prohibiting of special laws, with a

full discussion of the constitutional restraint thereon is

found in Owens vs. Smith, et al., (1950), 216 S. C. 382, 58

S.E. (2d) 332. There the Court said, “ Where subject of

legislation is reasonably susceptible of general treatment,

a special enactment thereon is invalid under constitutional

provision prohibiting special law where general law can be

made applicable, and enactment is not authorized by an

other provision authorizing enactment of special provisions

respecting municipal government.”

III

In Brown vs. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, segre

gation of White and Colored Children in the public'schools

of the State was held to be a denial of the Equal Protection

Clause of the 14th Amendment. We feel that the above

cited case is applicable in the Beach Case, also.

IV

_ In Bolling vs. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, segregation in pub

lic ^schools of the District of Columbia was held to be vio

lative of the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment.

In the same case the Court said: at (P.P. 499-500).

Classification based solely upon race must be scrutinized

with particular care, since they are contrary to our tradi

tions and hence constitutionally suspect. As long as 1896,

8a

this Court declared the principle, that the Constitution of

the United States in its present form, forbids so far as

Civil and Political rights are concerned, discrimination by

the general government or by the States, against any citi

zen because of race. And, in Buchanan vs. Warley, 245

U. S. 60, the Court held that a statute which limited the

rights of property owners to convey his property to a per

son of another race was held as unreasonable discrimina

tion, a denial of due process of the law.”

EQUAL PROTECTION DEN IED:

In Gillespie vs. Pickens County, 197 S. C. 217, 14 S.E.

(2d) 900, where an act fixed a period of limitation for ac

tions against Counties for salaries, fees, etc., but which

excluded from its operation claims against four Counties

of the State, violated the Equal Protection and Due Process

Clause of the State and Federal Constitution.

DUE PROCESS CLAUSE DENIED:

Sections 5 and 6 of Act No. 502, 1944 Acts, which per

mitted School District to acquire the absolute ownership of

property and required the citizens of other School Districts

to help pay for it without acquiring any legal interest

whatever, therein, constituted a denial of Due Process and

Equal Protection of the laws. Moseley vs. Welch, 209 S. C.

19, 39 S.E. (2d) 133.

9a

CONCLUSION

FOR THE REASONS HEREINABOVE STATED

AND CASES CITED, IT IS RESPECTFULLY SUBMIT

TED THAT THE STATUTES IN QUESTION ARE UN

CONSTITUTIONAL AND THAT THE RELIEF

PRAYED FOR BY THE PETITIONERS SHOULD BE

GRANTED.

10a

IN D EX TO CASES

PAGE

1. McLaurins vs. Okla., State Regents

339 U.S. 637 .......................................................................... 4a

2. Carroll vs. Town o f York

109 S.C., 1, 95 S.E. 121 ....................................................... 5a

3. Webster vs. Williams

18 183 S.C. 368, 191 S.E. 51, 111 A.L.R. 1348.... 5a & 7a

4. Gaud vs. Walker

53 S.E. (2d) 316, 214 S.C. 451 ............................. 5a & 6a

5. Gillespie vs. Pickens County

14 S.E. (2d) 900, 197 S.C. 217............................... 6a & 8a

6. Serrins vs. State

128 S.E. 172, 132 S.C. 241.................................................. 6a

7. Thomas vs. MacKlen

195 S.E. 539, 186 S.C. 290.................................................. 6a

8. McKiever vs. City o f Sumter

135 S.E. 60, 137 S.C. 266..................................................... 6a

9. Owens vs. Smith, et al.

216 S.C., 382, 58 S.E. (2d) 332.......................................... 7a

10. Brown vs. Board of Education

347 U.S. 483 ............................. -...................................- ...... 7a

11. Bolling vs. Sharpe

347 U.S. 4 9 7 ............................................................................ 7a

12. Buchanan vs. Warley

245 U.S. 6 0 ........................ -................-................................. 8a

13. Moseley vs. Welch

209 S.C. 19, 39 S.E. (2d) 133............................................ 8a