Estes v. Dallas NAACP Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Estes v. Dallas NAACP Brief for Petitioners, 1979. 9e8dcc1d-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aade896f-16f9-4cb0-90da-ae8fe8713c87/estes-v-dallas-naacp-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed January 09, 2026.

Copied!

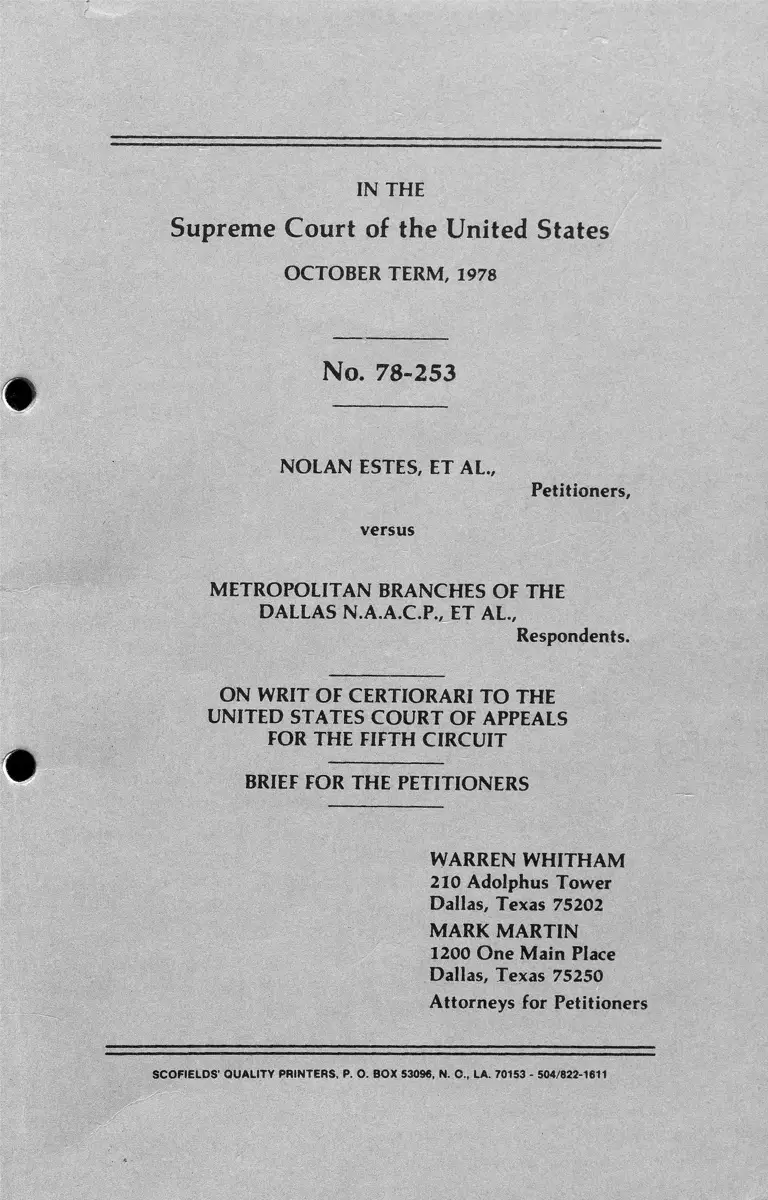

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM , 1978

No. 78-253

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

versus

METROPOLITAN BRANCHES OF THE

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

WARREN WHITHAM

210 Adolphus Tower

Dallas, Texas 75202

MARK M ARTIN

1200 One Main Place

Dallas, Texas 75250

Attorneys for Petitioners

SCO FIELD S ' Q UALITY PRINTERS, P. O. BO X 53096, N. 0 ., LA. 70153 - 504/822-1611

INDEX

Page

Opinions Below .............................................. i

Jurisdiction ......................................................... 2

Constitutional Provisions Involved ............. 2

Question P resen ted ............................................................. 2

Statement of the Case ........................................... 3

Summary of the Argument ..........................................38

Argument ........................................ 42

I. The Elimination O f All One-Race Schools Is

Not The Controlling Factor To Be Considered

In Determining Whether The Remedy For

mulated By The District Court Is Consistent

With The Equal Protection Clause And This

Court's Decisions in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, And

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (Milliken 11) . . 46

The Court O f Appeals Has Mis

construed Swann's Holding With

Respect To The Central Issue O f Stu

dent Assignment And In Particular

Swann's Language Concerning The

Specific Problem Area O f One-Race

Schools ................................................................... 46

Actions And Admissions Of The

R e sp o n d e n t-P la in tiffs And The

INDEX (Continued)

Page

Respondent-NAACP Are Contrary To

The One-Race School Criteria Seized

Upon By The Court O f Appeals . . . . . . . . . 55

Time And Distance Studies Were Not

Necessary ................. .. 56

Elimination O f All One-Race Schools

Cannot Be The Controlling Factor

When The District Court Is For

mulating A Remedy To Eliminate The

Vestiges Only O f A State-Imposed

Dual System ............................................. .. 58

The Court O f Appeals Should Have

Considered And Determined The Non-

Student Assignment Provisions O f

The Remedy Formulated By The Dis

trict Court As Appropriate Tools Or

Techniques O f Desegregation Consis

tent With The Equal Protection Clause

And This Court's Decision In Milliken II . 61-62

II. Why The District Court's Final Order Should

Be Affirmed In Its Entirety ................... ............ 67

Conclusion .............................................................71

Proof of Service .................................... ..................73

Cases: Pa«e

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1 9 6 8 ) .............................................39,52

Jones v. Caddo Parish School Board, 487 F.2d 1275

(5th Cir. 1973) ..................................................... 41,67

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado,

413 U.S. 189 (1973), reh. denied 414 U.S.

883 (1973) ................................................................. 45

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) .............54,69

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977)

(Milliken I I ) ...... ................................ P^sim

CITATIONS

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1 9 7 6 ) ........................................ 50,61,69

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), reh. denied 403 U.S.

912 (1971) ........................................................passim

Tasby v. Estes, 444 F.2d 124 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 1 ).............4

Tasby v. Estes, 517 F.2d 92 (5th Cir. 1975), cert,

denied 423 U.S. 939 (1975) ............................ 4,6,14

United States v. Montgomery County Board of

Education, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ................ 39,50,54

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1 9 7 6 ) .............. 47

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) 6 9

CITATIONS (Continued)

Page

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions:

28 U.S.C. Section 1254(1) ..................... .....................2

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,3,38,46-48,71

Miscellaneous:

Bell, Integration Ideals and Client Interests, 85

Yale L.J. 470 (March, 1 9 7 6 ) ..................... 64,65,66

Webster's Third New International Dictionary, G.

& C. Merriam Company, Publishers,

Springfield, Massachusetts, 1971 . . . . . 59

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

O CTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 78-253

NOLAN ESTES, ET AL„

Petitioners,

versus

METROPOLITAN BRANCHES OF THE

DALLAS N.A.A.C.P., ET AL.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinions, orders and judgment of the District

Court (Estes Pet. App. “B", 4a~129a) are reported in

part at 412 F.Supp. 1192. The opinion of the Court of

Appeals (Estes Pet. App. "C ", 130a-146a) is reported at

572 F.2d 1010.

JU RISDICTIO N

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered

on April 21, 1978 (App., 16-18). A Petition for Rehear

ing was denied on May 22, 1978 (Estes Pet. App. "D",

146a-147a). The Petition for Writ of Certiorari was

filed on August 14,1978, and was granted on February

21, 1979. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked un

der the provisions of 28 U.S.C. Section 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL PRO VISIO N S INVOLVED

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

provides in pertinent parts as follows:

, . nor shall any State * * * deny to any per

son within its jurisdiction the equal protection

of the laws."

QUESTION PRESENTED

Among the issues before the Courts below was the

constitutionality of the remedy formulated by the Dis

trict Court to eliminate the vestiges of a state-imposed

dual school system in the large urban school system

described in this Brief and by the Courts below. The

question presented is:

Whether as to such school systems, the elimination

of all one-race schools is the controlling factor to be

considered in determining whether a remedy formulat

ed by the District Court is consistent with the Equal

Protection Clause and this Court's decisions in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, and

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (Milliken II).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action was brought in the District Court against

Petitioners, the members of the Board of Trustees of

the Dallas Independent School District and its General

Superintendent (the School District), on October 6,

1970, by both Blacks and Mexican-Americans

(Respondent-Plaintiffs) asserting de jure segregation

of each class and seeking the establishment of a unitary

school system for each class.

The School District and the federal courts have been

on intimate terms in school desegregation matters

since 1955 immediately following Brown 11. The instant

action is not the first, but a second and separate Dallas

school desegregation case. At the time the instant ac

tion was filed there was also pending in the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Tex

as an existing class action desegregation suit in which

continuing jurisdiction is exercised by the District

Court and in which the various earlier proceedings in

volving desegregation of the School District have been

determined.1

1 The various proceedings in that action in part may be found at

Bell v. Rippy, 133 F.Supp. 811 (N.D.Tex., 1955), Brown v. Rippy, 233

p 2d 796 (5th Cir., 1956), cert, denied, 352 U.S. 878; Bell v. Rippy, 146

3

4

On June 3,1971, in a decision entered as a result of an

appeal from an order denying the Respondent-

Plaintiffs' first motion for preliminary injunction, the

Court of Appeals directed the District Court to make

full written findings of fact and conclusions of law on

the merits of this action in the light of principles enun

ciated in Swann. Tasby v. Estes, 444 F.2d 124 (5th Cir,

1971). The District Court did so in August, 1971. The

Respondent-Plaintiffs again appealed.

Almost four years later, on July 23, 1975, the Court

of Appeals, among other things, vacated the student

assignment plan ordered by the District Court in

August of 1971 and remanded with directions to. for

mulate elementary and secondary student assignment

plans which comport with the directives of the

Supreme Court and that July 23, 1975, Opinion-

Mandate of the Court of Appeals. Tasby v. Estes, 517 F.2d

92 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 939.

On August 25,1975, over the School District's objec

tions, the District Court allowed the Metropolitan

Branches of the Dallas N.A.A.C.P. (Respondent-

NAACP) to intervene. (August 25, 1975, Order

permitting NAACP to Intervene; App., 13-14)

F.Supp. 485 (N.D.Tex., 1956); Borders v. Rippy, 247 F.2d 268 (5th

Cir., 1957); Rippy v. Borders, 250 F.2d 690 (5th Cir,, 1957); Boson v.

Rippy, 275 F.2d 850 (5th Cir., 1960); Borders v. Rippy, 184 F.Supp. 402

(N.D.Tex., 1960); Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir., 1960); Borders

v. Rippy, 188 F.Supp. 231 (N.D.Tex., 1960); Borders v. Rippy, 195

F.Supp. 732 (N.D.Tex., 1961); Britton v. Folsom, 348 F.2d 158 (5th

Cir., 1965); and Britton v. Folsom, 350 F.2d 1022 (5th Cir., 1965).

5

On February 2, 1976, trial on fashioning a student

assignment plan once again commenced in the District

Court. This trial lasted five weeks, 44 witnesses testi

fied and there were 145 exhibits admitted into

evidence. Besides the initial parties Plaintiffs and the

School District, six Intervenors participated: (1) Curry,

et al, (2) Maxwell, (3) Brinegar, et al, (4) Strom, et al-

Oak Cliff, (5) Strom, et al-Pleasant Grove, and (6) the

NAACP-Intervenors. In addition the tri-ethnic

Educational Task Force of the Dallas Alliance as

Amicus Curiae participated and presented evidence.

There were six student assignment plans before the

Court prior to the District Court's March 10, 1976,

Opinion and Order (Estes Pet. App. "B", 4a-44a),

including a plan developed by the Court's own appoint

ed desegregation expert, Dr. Josiah C. Hall, who has

been associated with the University of Miami

Desegregation Consulting Center. After March 10,

1976, and prior to the April 7, 1976, Final Order there

was yet a seventh plan before the Court. This was a

plan developed by the School District pursuant to the

District Court's March 10, 1976, Opinion and Order

directing the School District to set forth the specifics of

the Amicus Curiae concept proposals presented to the

District Court. This trial culminated in the District

Court's April 7, 1976, Final Order, as supplemented,

and it is from such April 7,1976, Final Order, as supple

mented, that the appeal to the Court of Appeals arose.

The District Court's April 7, 1976, Final Order (Estes

Pet. App. "B", 53a-120a), as supplemented (Estes Pet.

App. "B", 121a-129a), containing the remedy formulat

ed by the District Court and here in question, will

hereafter be referred to as the Final Order.

Both Courts below have correctly recognized the ur

ban metropolitan nature of the School District and that

the School District is not a small rural school system

but is the eighth largest urban school district in the

United States.

As to Mexican-American students the District Court

specifically found in a July 16, 1971, Memorandum

Opinion (Brinegar Pet. App. A, A -l-A -6), that the

Plaintiff Mexican-Americans failed to maintain their

burden of proof to show that there had been some form

of de jiire segregation against Mexican-American

students. However, the District Court by that same

order of July 16,1971, directed that Mexican-American

students be considered as a separate ethnic group and a

“minority" for purposes of a desegregation plan. Hence

in the School District the problem exists of formulat

ing a tri-ethnic remedy and the phrase “Anglo" is used

in lieu of "white" under such circumstances. Tasby, 517

F.2d at 106.

There is no actual total population census of the

School District. The boundaries of the City of Dallas

and the School District are not coterminous. The pop

ulation of the City of Dallas is 800,000 to 900,000.1 he

ethnic composition of the total population of the School

District, as distinguished from student enrollment, ap

proximates the ethnic composition of the population of

6

the City of Dallas which is estimated to be 25% or 30%

Black, 10% to 15% Chicano and the remainder Anglo.

(R. Vol. I, 279, 405, 406; App„ 36-37, 37-39) This is far

different from the ethnic composition of the student

population of the School District.

In 1975 the student population of the School District

was 41.1% Anglo, 44.5% Black, 13.4% Mexican-

American and 1% "other." (Def. Ex. 11, pp. 1, 2; R. Vol.

I, 63, 64; App., 222-223, 21-23) The Court is advised

that as of March 1, 1979, the student population of the

School District was 33.50% Anglo, 49.11% Black,

16.37% Mexican-American and 1.03% "other." This

enrollment pattern then at the time of preparation of

this brief would be as follows:

December 1, 1975 March 1, 1979

7

Number Percent Number Percent

Anglo 58,023 41.1 44,766 33.50

Black 62,767 44.5 65,637 49.11

Mexican-

American

18,889 13.4 21,876 16.37

Other 1,443 1.0 1,369 1.03

141,122 133,648

At the time of trial on February 2, 1976, the School

District had lost approximately 40,000 Anglo students

during the pendency of this second action. As the

students become younger there is a decided drop in the

number and percentage of Anglo students. (Def. Ex.

13, R. Vol. I, 71; Def. Ex. 11, pp. 1, 2, R. Vol. I, 63, 64;

App., 224-225, 25-26, 222-223, 21-23)

Defendants' Exhibit 13, which reflects the historical

enrollment of the School District, is as follows:

HISTORICAL ENROLLMENT

Dallas Independent School District

Mexican-

Dates Anglo Percent Negro Percent American Percent Total

October, 1969-70 97,131 52,531 13,606

Kindergarten

Total

- 28

97,103

- 271

52,260

- 94

13,512 162,875

October, 1970-71 95,133 55,648 13,945

Kindergarten - 121 -1,036 - 216

Total 95,012 - 2.2 54,612 + 4,5 13,729 + 1.6 163,353

October, 1971-72 86,548 57,394 15,154

Kindergarten

Total

- 66

86,482 - 9.0

-1,455

55,939 + 2.3 ^

- 269

14,885 + 8.4 157,306

October, 1972-73 78,560 59,643 15,909 ,

Kindergarten

Total

- 126

78,434 - 9.3

-2,383

57,260 + 2.4

- 514

15,395 + 3.4 151,089

October, 1973-74 73,042 62,468 17,141

Kindergarten

Total

-3,439

69,603 - 11.3

-3,575

58,893 + 2.9

-1,276

15,865 + 3.1 144,361

* HEW Report (Continued below)

Mexican-

Dates Anglo Percent Negro Percent American Percent Total

October, 1974-75 67,324 63,760 18,426

Kindergarten -3,821 -4,105 -1,562

Total 63,503 - 8.8 59,655 + 1.3 16,864 + 6.3 140,022

October, 1975 60,796 64,594 18,994

Kindergarten -3,370 -4,338 -1,559

Total 57,426 - 9.6 60,256 + 1.0 17,435 + 3.4 135,117

1969-70 97,103 - 52,260 - 13,512

1975 - 57,426 60,256 17,435

Total Loss 39,677 - 40.9 7,996 + 15.3 3,923 + 29.0

Since kindergarten attendance was not mandatory during the entire period shown on this

exhibit, appropriate adjustments have been made and the calculations based on Grades 1-

1 2 .

The ethnic make-up by grade level of the School District as of December 1, 1975, was:

(Def. Ex. 11, pp. 1, 2; App. 222-223)

Grade Mexican-

Level Anglo % Black % American % Other % Total

K 3254 34.8 4429 47.3 1595 17.0 87 .9 9365

1 4260 36.7 5274 45.5 1955 16.9 113 1.0 11602

2 ' 4095 36.9 5080 45.7 1822 16.4 104 1.0 11101

3 3947 36.7 5056 46.9 1648 15.3 118 1.1 10769

4 3756 35.5 5098 48.1 1608 15.2 131 1.2 10593

5 4226 37.5 5251 46.6 1672 14.8 125 1.1 11274

6 4543 39.3 5394 46.6 1504 13.0 128 1.1 11569

7 4853 41.0 5356 45.2 1532 12.9 103 .9 11844

8 5039 42,2 5343 44.8 1438 12.1 115 1.0 11935

9 5231 43.5 5406 45.0 1286 10.7 100 .8 12023

10 5287 45.4 4943 42.5 1259 10.8 155 1.3 11644

11 4828 51.5 3526 37.5 936 10.0 93 1.0 9383

12 4704 58.7 2611 32.6 634 7.9 71 .8 8020

TOTAL 58023 41.1 62767 44.5 18889 13.4 1443 1.0 141122

1 1

The School District estimates that in 1980 the

percentage of Anglo enrollment will be 26%, that Black

enrollment will be 57% and that Mexican-American

enrollment will be 18%. (R. Vol. I, 67, 68; App., 23-24,

24-25)

The School District contains approximately 351

square miles within the 900 square miles of Dallas

County. From the School District's most northerly

point to its most southerly, there is a distance of

approximately 35 miles viewed from the northwest to

the southeastern part of the district. It is about 25 miles

from what is called the southwest quadrant in Oak

Cliff just below Hulcy Junior High School to the

northernmost point near the Dallas County line. (R.

Vol. I, 405; App., 37-38)

In addition to being faced with the task of fashioning

a remedy for an ever increasing minority Anglo school

system, the District Court also had the problem of pre

serving naturally integrated areas and schools which

had become naturally integrated due to changing hous

ing patterns. All of the plans before the Court sub

mitted by all of the parties, the Amicus Curiae and the

Court's desegregation expert recognized and accepted

the concept that there was no reason to disturb already

desegregated neighborhood schools. Each plan pro

posed to leave certain areas and schools alone as they

were naturally integrated. (R. Vol. 1,104,105; Hall s Ex.

5, pp. 14-19, R. Vol. IV, 123; R. Vol. IV, 129, 130;

NAACP Ex. 2, p. 6, R. Vol. IV, 6; R. Vol. IV, 15, 16,19;

12

PL Ex. 16, pp. 9, 41, R. Vol. Ill, 231, 243; R. Vol. Ill, 241-

242, 259, 330, 355, 406, 410; App., 33-35, 251-259,100-

10.1; 102-103, 230, 92-93, 93-95, 95-96, 237-238, 248-

249, 70-71, 73-74, 71-72, 74-75, 75-76; 76-77, 86-87,

89-90)

Further the District Court had to consider the loca

tion within the School District of these naturally

integrated areas and schools in relationship to those

areas containing the remaining predominantly Anglo

students and those areas containing predominantly

Mexican-American or Black enrollment. The area con

taining the only remaining predominantly Anglo

students lies generally in a strip along the northern and

certa in eastern sections of the system. The

predominantly Mexican-American or Black students

reside to the south and southeast in areas distant from

the predominantly Anglo students. Separating the

remaining predominantly Anglo students and the

predominantly Mexican-American or Black students

are large portions of the naturally integrated areas and

schools. (D ef. Ex. 2, R. Vol. I, 77, 85; Def. Ex. 3, R. Vol. I,

81, 85; R. Vol. I, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81; App., 220, 27-28, 31-

33, 221, 30-31, 31-33, 27-28, 28, 29, 29-30, 30-31)

Defendants' Exhibit 1 reflects the Black and white

racial composition of the student population by

residential patterns in the year 1960. The orange area

shows the residential location of Black students in the

year 1960. The yellow area shows the residential loca

tion of white students in the year 1960. In 1960 sep

13

arate statistics were not kept as to Mexican-American

students and Mexican-American students were count

ed as "white." In 1960 Mexican-American students

were located in the area of the present Travis Elemen

tary School and the Juarez and Douglass Elementary

Schools. To that extent the Mexican-American student

population in 1960 would be shown in the yellow area

on Defendants' Exhibit 1. (R. Vol. I, 76; App., 26-27)

Defendants' Exhibit 2 reflects the current residential

patterns of students in the School District. The yellow

zone on that map reflects the only remaining

predominantly white students, the pink zone is the

naturally integrated area representing minority and

Anglo, and the dark orange on that map represents

predominantly Mexican-American or Black enroll

ment. (R. Vol. I, 77, 78; App., 27, 28)

Defendants' Exhibit 3 reflects the growth over the

period 1960, 1965 and 1970 of the growing Black

scholastic population within the School District, as well

as the areas of the School District that in 1975 were

composed of at least 25% Black students, the areas that

in 1975 were at least 25% Mexican-American and the

areas that in 1975 were at least 25% minority com

bined, i.e., 25% of both Black and Mexican-American.

(R. Vol. I, 80, 81; App., 29-30, 30-31)

In its July 23, 1975, Opinion-Mandate the Court of

Appeals made reference to the "endurance record

perhaps, but not speed records" set with respect to

14

desegregation litigation concerning the School Dis

trict. Tasby, 517 F.2d at 109. The Court of Appeals there

also observed "The DISD is no stranger to school de

segregation proceedings before this Court." Id. at 95.

If there is one overriding concern of the School Dis

trict, it may be fairly said to be that the School District

would indeed like to become a stranger to school

desegregation proceedings. To that end, and given the

origin and development of what became the provisions

of the District Court's Final Order, the School District

supports the District Court's Final Order and asks that

it be affirmed in its entirety by this Court.

During the course of hearings in the District Court

commencing February 2, 1976, the descriptive ter

minology of "student assignment" provisions and

"non-student assignment" provisions developed, As

used, non-student assignment provisions involved

judicial remedies in desegregation proceedings going

beyond student assignment plans and pertaining to (a)

the operation and management of the business and af

fairs of the School District, and (b) the education,

curriculum and program aspects of the School District.

r

On September 16, 1975, the District Court in a

public hearing expressed great dissatisfaction with

both a desegregation plan proposed by the School Dis

trict and a plan proposed by the Respondent-NAACP.

The District Court went on to point out that this was a

community-wide problem that involved all segments of

15

the city. (R. September 16, 1975, Hearing on Plaintiffs'

Motion for Further Relief, 83-91; App., 198-204) As a

result of the District Court's comments, there came to

be presented to the District Court certain concept

proposals of an organization known as the Educational

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance. It was from such con

cepts that the Final Order originated.

The Educational Task Force of the Dallas Alliance is a

tri-ethnic group. A description of how the Educational

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance came into being and

how its concepts came to be presented to the District

Court is summarized below.

There exists in the City of Dallas a community serv

ice organization known as the Dallas Alliance to act

upon urban issues. A description of the Dallas Alliance

and its activities during and preceding the trial com

mencing February 2, 1976, follows.

The Dallas Alliance was composed of a board of forty

trustees. (R. Vol. V, 50, 51; App., 132, 133) O f these

forty persons, eleven were Black, four were Mexican-

American, one was American Indian and the re

mainder were Anglo. (R. Vol. V, 226, 227; App., 153-

154, 154-155) In addition the Dallas Alliance had 77

cooperating or corresponding organizations with

whom it communicated and received views and infor

mation. (R. Vol. V, 52, 53; App., 133-134, 134-135)

Prior to instituting its Educational Task Force the

Dallas Alliance had two other task forces in operation.

One was on the Criminal Justice System and the sec

ond on Neighborhood Regeneration and Mainte

nance. (R. Vol. V, 54, 55; App., 135, 136) On October

23,1975, the Dallas Alliance authorized an Educational

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance. (R. Vol. V, 59, 61,62,

388; Def. Ex. 17, R. Vol. V, 387; App„ 136-138, 161-

162, 226-229, 160-161) Creation of that Task Force

came about as follows. Following the District Court's

comments of September 16, 1975, a group of twenty

citizens, some of whom belonged to the Dallas Alliance

and some of whom did not, had constituted them

selves together as a committee to look into some

matters with respect to education in the School District

and to inquire into whether the processes of developing

a desegregation plan were possible. (R. Vol. V, 68, 69; .

App., 142, 143) The committee was made up of six

Blacks, seven Mexican-Americans and seven Anglos.

(R. Vol. V, 7; App., 125) This committee sought and ob

tained from the Dallas Alliance status as its Educa

tional Task Force. (R. Vol. V, 61; App., 137-138) Nine

persons serving on the committee that then became the

Educational Task Force were at that time members of

the Dallas Alliance. (R. Vol. V, 64, 65; App., 139-140,

140-141) After the committee became the Educational

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance the American Indian

member of Dallas Alliance became a member of the

Educational Task Force. (R. Vol. V, 65, 66, 69; App.,

140-141, 142-143)

On December 18, 1975, the District Court sum

moned all parties and their attorneys to appear before it

and in effect introduced the Educational Task Force to

the parties and indicated strongly its support for their

efforts. (R. December 18, 1975, Called Hearing of

Judge Taylor, 1-14; App., 205-215) The Educational

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance was given a charge by

the Dallas Alliance to attempt to design a plan for the

school system. (R. Vol. V, 75; App., 143-144) This it set

out to do as follows:

The Task Force was assigned the services of the Ex

ecutive Director of the Dallas Alliance, Dr. Paul Geisel.

(R. Vol. V, 2; App., 122-123) Dr. Geisel was on leave of

absence from the University of Texas at Arlington

where he is a Professor of Urban Affairs. (R. Vol. V, 3;

App., 123-124) Dr. Geisel holds a PhD in sociology

from Vanderbilt; he did as his doctoral dissertation a

study of the educational and aspirational achievement

levels of students in the Chattanooga, Tennessee,

school system; he has been employed by Tuskegee In

stitute; and while teaching at the University of Pitts

burgh he did an analysis of the Pittsburgh schools in

terms of racial achievements and racial integration and

was the Educational Chairman of the Allegheny Coun

ty NAACP. (R. Vol. V, 5; App., 124-125) Dr. Geisel

went to work with the Educational Task Force of the

Dallas Alliance in the middle of October, 1975. (R. Vol.

V, 21; App., 128) Upon obtaining status as the Educa

tional Task Force of the Dallas Alliance that Task Force

met on a regular basis every Tuesday evening for an ex

tended period until about December 16, 1975. (R. Vol.

V, 22; App., 128) The Task Force was first briefed by

school personnel and by city officials. Thereafter Dr.

17

Geisel traveled throughout the country to meet with

various leading figures in the field of desegregating

public schools. (R. Vol. V, 22; App., 128) In the course of

this work Dr. Geisel personally saw, or spoke from his

office by telephone with, approximately thirty differ

ent people. Dr. Geisel talked by telephone extensively

with people in Atlanta, Charlotte-Mecklenburg and

Jacksonville, Florida. When Dr. Geisel returned to

Dallas from his travels, he made a report to the Educa

tional Task Force on the kinds of ideas and processes

used to desegregate schools and the kinds of issues that

are involved. (R. Vol. V, 22; App,, 128) On Tuesday

evening, December 16, 1975, the Task Force heard Dr.

Geisel's report and developed guidelines for him to

follow. Dr. Geisel was then given until January 6 ,1976,

to attempt to formulate, develop and flesh out what the

proposals would look like if they were turned in as pro

posals for a desegregation plan. (R. Vol. V, 23; App.,

129)

The Task Force then began meeting on Tuesday

nights as well as on Saturdays, and in many instances

on Sundays. Altogether the Task Force spent about

1,500 hours together. (R. Vol. V, 23; App., 129)

The Task Force came to a consensus, to a community

of the mind, and they came to understand what each

member was attempting to achieve through his or her

participation. (R. Vol. V, 24; App., 129-130) On Mon

day, February 16, 1976, the Educational Task Force

went to the District Court and presented its plan. (R.

18

19

Vol. V, 24; A pp.,129-130) The "consensus" of the Task

Force was much more than a bare majority. The initial

proposal submitted to the District Court reflected the

support of nineteen of the twenty-one members. (R.

Vol. V, 102; App., 144-145) Sixteen members of the

Task Force were present at the time their proposals

were submitted to the District Court on February 16,

1976. (R. Vol. V, 104; App., 145-146)

The Task Force consulted with some thirty experts.

The Task Force was interested in talking to people who

were skilled in the field of education and skilled in the

field of desegregation. Most of these people were con

tacted personally by Dr. Geisel. In rare instances the

consultants dealt directly with the Task Force members

themselves. (R. Vol. V, 369, 370; App., 155-156, 156-

157)

Persons contacted on behalf of the Educational Task

Force were: Dr. Jose Cardenas (also the Plaintiffs

witness); Dr. Horacio Ulibarri (from New Mexico); Dr.

Robert Green, Dean of the College of Urban Develop

ment at Michigan State; Dr. Flarold Gores, Education

al Facilities Laboratory; Dr. Frank Rose, Executive Di

rector of the Lamar Society of the University

Associates in Washington; Dr. Thomas Pettigrew, then

on leave from Stanford University; Dr. Rudolpho

Alvarrez, Professor of Sociology in Chicano studies at

U.C.L.A.; Wilson Riles, State Superintendent of Public

Instruction in California; Davis Campbell, Assistant to

the State Superintendent of Public Instruction of

20

California; Marion Joseph, Assistant to the State

Superintendent of Public Instruction of California; Ray

Martinez, Superintendent of instruction at Pasadena,

California; Jim Taylor and Ron Prescott, officials in the

Los Angeles School District; Robert Nicewander, Unit

ed States Office of Education; Marshall Smith of the

National Institute of Education; Dennis Doyle,

National Institute of Education; Jack Troutman, a local

consultant; Dr. Julius Truelson, former president of

the Great Cities School System and former Superin

tendent of Schools, Fort Worth Independent School

District; Research and superintendent's staff, Fort

Worth Independent School District; School Superin

tendent of Sacramento, California; School Superin

tendent of San Francisco Schools; School Superin

tendent of Charlotte, North Carolina; City Planning

Department of the City of Dallas; Dr. Leon Lessinger,

Dean of the College of Education of the University of

South Carolina. (R. Vol. V, 370-372; App., 156-158)

While the Task Force did examine the school systems

in a good many cities, it did not try to imitate or copy

any other city. The Task Force tried to come up with

something unique for the total city of Dallas. (R. Vol. V,

373, 374; App., 158-189, 159-160)

Following the Task Force presentation to the District

Court on Monday, February 16, 1976, that Court on

Tuesday, February 17, 1976, submitted the Task

Force's proposals to the parties and announced that the

Educational Task Force of Dallas Alliance would be rec

21

ognized by the Court as Amicus Curiae. The Court

then asked the parties to study these proposals and

report back their reactions. The reactions of the

Respondent-Plaintiffs, the School District and the

Respondent-NAACP were unfavorable to various

aspects of the proposals. (R. Vol. IV, 295-317; App.,

104-121) The Court then called Dr. Geisel to the stand

as the Court's witness and the Task Force proposals

were introduced in evidence. (R. Vol. V, 8 , 9; App., 126-

127) On March 3, 1976, the Task Force filed its modi

fied proposals (R. Vol. IX, 363; App., 196-197) A mem

ber of the Task Force was called by the Court as the

Court's witness to testify concerning the modified

proposals. (R. Vol. IX, 361; App., 196)

It was the concepts in these March 3 ,1976 , modified

proposals which the District Court adopted in two pre

liminary orders. The District Court directed the School

District to set forth in writing the specifics of these

modified proposals. In this connection the District

Court's March 10, 1976, Opinion and Order provided:

(Estes Pet. App. "B", 41a)

"Accordingly, it is ORDERED by the Court

that the modified plan of the Educational Task

Force of the Dallas Alliance filed with the

Court on March 3, 1976, is hereby adopted as

the Court's plan for removal of all vestiges of a

dual system remaining in the Dallas Inde

pendent School District, and the school dis

trict is directed to prepare and file with the

2 2

Court a student assignment plan carrying into

effect the concept of said Task Force plan no

later than March 24, 1976."

and the District Court's March 15,1976, Supplement

al Order provided; (Estes Pet. App. "B", 45a, 46a)

"During the process of fleshing out the

Court's Order of March 10, 1975, some

questions have arisen regarding the Court's

adoption of the Dallas Alliance's plan. So that

there is no misunderstanding in this regard,

the Court intended by the order of March 10

to adopt the concepts suggested by the plan of

the Educational Task Force of the Dallas

Alliance. The staff of the school district shall

take these concepts and adapt them to fit the

characteristics of the Dallas Independent

School District. The Court recognizes that

during this process, a certain amount of flexi

bility is necessary. The Court expects the

school district to put into effect the concepts

of the Dallas Alliance plan. The specifics of the

desegregation plan for the DISD will be em

bodied in the Court's Final Order which will

be entered in approximately two weeks."

Obedient to the District Court's orders, the School

District on March 24,1976, on March 29,1976, and on

April 1, 1976, filed with the Court three separate

documents representing its efforts to set forth the

23

specifics of the modified proposals of the Educational

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance.

On April 7,1976, the District Court in its Final Order

fashioned and directed the remedy thought to be

necessary by that Court to eliminate the vestiges of a

dual school system in the School District. In the Dis

trict Court's language introducing that remedy: (Estes

Pet. App. "B", 47a)

"The Court has received and thoroughly con

sidered suggestions made by various inter

veners and by the Amicus Curiae Educational

Task Force of the Dallas Alliance subsequent

to the submission of the DISD's student

assignment plan on March 24. The Court is of

the opinion that many of these suggestions

have merit and should be reflected in the stu

dent assignment plan. The Court has thus

modified the document submitted by the

DISD to incorporate many of these sug

gestions. It has fu rth er incorporated

modifications necessary in order that the

spirit of the Dallas Alliance's plan will be im

plemented to the fullest extent possible.

These changes appear in the Final Order

entered this day."

The District Court's Final Order constitutes a

judicial sanction of the heart of a compromise reached

by a tri-ethnic group of citizens. The concepts pro

posed to the District Court by the Educational Task

Force of the Dallas Alliance represent a compromise

arrived at in the eleventh hour in which the hard

bargain was struck between a student assignment plan

which might be briefly summarized as providing (a) a

somewhat "neighborhood" approach to schools for

grades K-3 and 9-12, and (b) judicially forced inte

grated 4-6 grade centers and 7-8 grade centers re

quiring busing, and (c) unique and special districtwide

vanguard schools for grades 4-6, academy schools for

grades 7-8, and magnet schools for grades 9-12, on the

one hand; and on the other hand, increased participa

tion by minorities in the day-to-day running of the

School District by virtue of the 44% Anglo, 44% Black

and 12% Mexican-American ethnic ratio applicable to

the top salaried administrative positions in the School

District, then established at 142 in number (R. Vol. V,

133-137, 213-215; App., 146-150, 151-153)

Respondents Plaintiffs and NAACP have opposed

and objected to only the student assignment portions of the

District Court's Final Order. These Respondents want

both massive busing in a now minority Anglo school

district as well as the imposition upon the School Dis

trict of federal court orders involving the federal

judicial system in (a) the operation and management of

the business and affairs of the School District, and (b)

the education, curriculum and program aspects of the

School District.

Implementation of the District Court's Final Order

commenced in August of 1976 with the opening of the

1976-77 school year. Thereafter, on October 11, 1976,

the Board of Education of the School District unani

mously adopted an order calling an election to be held

December 11, 1976, on the proposition of whether the

Board be authorized to issue bonds in the amount of

$80,000,000.00 for the purpose of the construction and

equipment of school buildings in the School District

and the purchase of necessary sites therefor. That

Board of Education was, and still is, composed of nine

members. These School Trustees were not elected "at

large/' but rather each was elected from single

member trustee districts fairly apportioned. The Board

is composed of six Anglos, two Blacks and one

Mexican-American. (R. February 24, 1977, Hearing of

Defendants' Motion for Approval of Site Acquisition,

School Construction and Facility Abandonment, 5, 6;

R. Vol. II, 54, 58-60; App., 216-217, 40, 41-43)

On December 11, 1976, the voters in the School Dis

trict — including the voters in the East Oak Cliff Sub

district — voted in favor of this $80,000,000.00 school

improvement bond issue. In the East Oak Cliff area

there were 3,000 votes for the bond issue and only 300

or 400 votes against this bond issue. 1 he bond issue

also carried by an overwhelming majority in South

Dallas which is also a predominantly black area in the

School District. (R. February 24, 1977, Hearing of

Defendants' Motion for Approval of Site Acquisition,

School Construction and Facility Abandonment, 6, 7;

App., 217-218)

25

2 6

All parties essentially agree that the time and dis

tance students must spend on buses together with traf

fic congestion prevent transportation of students

between what is identified by the District Court as the

virtually all-black East Oak Cliff area and the area con

taining the remaining Anglos in the strip along the

north and east portions of the School District. All plans

before the District Court except Respondent-

Plaintiffs' Plan A left all or portions of this East Oak

C liff area with one-race schools. Even then

Respondent-Plaintiffs did not seriously urge their Plan

A to the District Court.

Respondent-Plaintiffs' expert witness, Dr. Charles V.

Willie, testified:

"Yes, I made time studies of how long it would

take to go from the tip end of North Dallas to

Oak Cliff and I found that to be an exceedingly long

distance. But I don't think that the School Dis

tricts have to be laid out that way." (Emphasis

ours) (R, Vol. Ill, 134; App., 51)

Respondent-Plaintiffs' witness and lead counsel, Mr.

Edward B. Cloutman, III, testified concerning their

only effort at a time and distance study as to which

evidence was presented:

"A. It's the one next to the Dealey zone. I

think that one we that we made was at least

27

about thirty-four, thirty-five minutes and it

took — it was about twenty-two miles."

* * *

"Q . . . . What route did you take?

"A. We took a, I believe, east-west major

street. I believe Royal Lane, to the Tollway,

south to 1-35,1-35 to I believe Ledbetter on the

southern end, Ledbetter east — Lve for

gotten the street name. It's the same street

that the Veteran's Hospital is on, turning

north and then to the school.

"Q . What time of day?

"A. It was about noon.

"Q . What day of the week?

"A. It was on a Sunday." (Emphasis ours) (R.

Vol. Ill, 375, 376; App., 79-80)

The Court's witness, Dr. Paul Geisel, testified:

"Q . And you left South Oak Cliff. Now, as I

would look at that map, it would leave South

Oak Cliff all black, I believe that would be.

"A. Essentially.

"Q . What was the reason — was there any

reason for that?

"A. The reason that had to do with two com

ponents, I believe. One was the issue of

attempting to — not to do cross town busing or do

busing that required a travel time of greater than thirty

minutes . . ." (Emphasis ours) (R. Vol. V, 49;

App., 130-131)

28

In three separate places Respondent-Plaintiffs' Plan

B states the reason for leaving black one-race schools in

the East Oak Cliff Subdistrict. In the thrice repeated

language of Plaintiffs: (PL Ex. 16, pp. 34, 36, 38, R. Vol.

Ill, 231, 243; R. Vol. Ill, 376, 377; App., 239-240, 241-

243, 243-245, 70, 73-74, 80)

"Distance from the majority white areas,

capacity of schools, DISD enrollment patterns and

generally good physical facilities were factors

resulting in South Oak Cliff retaining its pres

ent student assignment patterns." (Emphasis

ours)

The "South Oak Cliff" referred to is the area now re

ferred to as East Oak Cliff in the District Court's Final

Order. By Respondent-Plaintiffs' own admission in

their Plan B, and by their own attorney-witness's tes

timony, the long distance of the East Oak Cliff Sub

district from areas containing white students is so

great that the continued existence of black one-race

schools in East Oak Cliff is justified. (R. Vol. Ill, 378,

379; App., 81-82, 82-83) Respondent-Plaintiffs also ad

mit in their Plan B, and by their own attorney-witness's

testimony, that the "enrollment patterns" in the School

District, i.e., an ever expanding scholastic population in

East Oak Cliff, the number of Black students and the

number of Anglo students in the School District and

the absence of Anglo student growth in the School Dis

trict, further justify the continued existence of black

one-race schools in East Oak Cliff. (R. Vol. Ill, 379-381,

407, 408; App., 82-84, 87-88, 88-89)

29

Respondent-Plaintiffs, by motions filed in the Dis

trict Court on April 2, 1976, and April 5, 1976, sought

an award of attorneys' fees in this action under Section

718 of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 on the

theory that they were the "prevailing party." On April

30, 1976, Respondent-Plaintiffs filed a brief in support

of their motion for attorneys' fees which contained the

following statement: (April 30, 1976, Brief in Support

of Motion for Attorneys' Fees and Costs, p. 4; App., 14)

"Finally, the plan adopted by the Court in its

order of March 10, 1976, together with Sup

plemental Opinion and Orders dated April 7,

1976, and April 15, 1976 adopt and/or incor

porate almost every precept proposed by

plaintiffs for student assignment and non

student assignment features of the remedy."

The District Court recognized that the Respondent-

Plaintiff Black and Mexican-American students ob

tained all of the student assignment and non-student

assignment relief they proposed and sought. The Dis

trict Court in its Order dated July 20, 1976, awarding

attorneys' fees and costs to Respondent-Plaintiffs,

pointed out: Quly 20, 1976, Memorandum Opinion, p.

3; App., 15)

"Finally, the plan adopted by the Court on

March 10, 1976, and Ordered to be imple

mented on April 7, 1976, and April 15, 1976,

incorporated almost every precept proposed

by plaintiffs for both student assignment and

non-student assignment remedies."

30

Respondent-Plaintiffs filed two plans with the Dis

trict Court on January 12,1976. Respondent-Plaintiffs'

Exhibit 16 contains both plans, one of which is iden

tified as Plan A and one as Plan B. Prior to the filing of

the School District's brief in the Court of Appeals

Respondent-Plaintiffs' counsel, Mr. Edward B. Clout-

man, III, advised counsel for the School District that

Respondent-Plaintiffs did not intend to urge either of

Respondent-Plaintiffs' Plans A or B in this case.

Respondent-Plaintiffs did not urge either of their plans

in the Court of Appeals. Both of Respondent-Plaintiffs'

plans have been abandoned by Respondent-Plaintiffs in

this action.

Various approaches in Respondent-Plaintiffs' two

plans support the student assignment plan contained in

the District Court's Final Order. Both Plaintiffs' Plans

A and B proposed to leave certain areas and schools of

the School District alone as those areas and schools

were naturally integrated. Respondent-Plaintiffs'

testimony admits that under Plaintiffs' Plan A, 13

elementary schools were considered desegregated and

were left alone as being naturally integrated. Plaintiffs'

testimony admitted that under Plaintiffs' Plan B, 41

elementary schools were considered desegregated and

were left alone as being naturally integrated. (PL Ex.

16, pp. 9, 41, R. Vol. Ill, 231, 243; R. Vol. Ill, 241, 242,

259, 330, 355, 406, 410; App., 237-238, 248-249, 70-71,

73-74, 71-72, 74-75, 75-76, 76-77, 86-87, 89-90) The

3 1

concept of leaving certain areas and schools of the

School District alone for the reason that those areas

and schools were naturally integrated is a part of the

student assignment plan contained in the District

Court's Final Order.

Both Respondent-Plaintiffs' Plans A and B proposed

magnet schools, some districtwide and some serving

smaller parts of the School District. As shown in the

Overview to Respondent-Plaintiffs' Plans A and B,

Respondent-Plaintiffs recommend that all magnet

schools should be constructed in the inner-city area to

encourage the inward flow of students, and particu

larly white students, and that these schools should seek

the assistance of local businesses and citizens in order

to acquire appropriate construction sites. Respondent-

Plaintiffs suggest that student enrollment in such

magnets should approximate the ethnic enrollment of

the School District as a whole with exceptions for the

elementary magnets created under Plan B. (PI. Ex. 16,

pp. 2, 39, R. Vol. Ill, 231, 243; R. Vol. Ill, 371, 372, 382,

383; App., 234-236, 245-247, 70-71, 73-74, 77-78, 78-

79, 84-85, 85-86)

This concept of magnet schools and their location in

the minority or inner-city areas to encourage the in

ward flow of students, and particularly white students,

with the participafion of the business community and

student enrollment approximating the ethnic enroll

ment of the School District as a whole is a part of the

student assignment plan contained in the District

Court's Final Order.

Respondent-Plaintiffs' Plan B leaves some virtually

all-black schools in what has become known as the East

Oak Cliff Subdistrict. Under Respondent-Plaintiffs'

Plan B there are 12 elementary schools, two junior high

schools and one high school that are black one-race

schools in East Oak Cliff. Respondent-Plaintiffs'Plan B

also leaves two all-black elementary schools in West

Dallas. These are Allen and Lanier. Respondent-

Plaintiffs' Plan B also leaves Dunbar an all-black

elementary school in South Dallas. (R. Vol. Ill, 378;

App., 81-82) Thus Respondent-Plaintiffs' Plan B leaves

15 all-black elementary schools, two all-black junior

high schools and one all-black high school.

Throughout, Respondent-NAACP has insisted that

the existence of some one-race schools invalidates the

student assignment portion of the remedy. Efowever,

Respondent-NAACP publicly admits it does not have a

solution. In a newspaper interview this public ad

mission was made by the attorney of record for the

Respondent-NAACP:

"And even the NAACP admits that it is having

some trouble finding a way to break up the all

black nature of the subdistrict. 'If I knew the

answer, I'd give it to you,' says NAACP at

torney E. Brice Cunningham. 'I admit that we

have not yet come up with an alternative to

some all-black schools. But we will still chal

lenge it in court.' " Dallas Morning News,

August 15, 1976, at 1, col. 2.

33

Respondent-NAACP demands racial balance in each

school and year-by-year adjustments in such quota

assignments. The Respondent-NAACP plan states:

"(a) Every school should have a racial balance

comparable to the racial balance in the District,

which will not deviate more than Ten Percent

(10%) up or down." (Emphasis ours) (NAACP

Ex. 2, p. 7, R. Vol. IV, 6; App., 231, 92-93)

* * *

"2. The first magnitude of desegregation

and the attaining of an Unitary School System

should be to achieve a racial balance of black and

white students in each school and then follow

through with the integration of other

minorities into the system." (Emphasis ours)

(NAACP Ex. 2, p. 7, R. Vol. IV, 6; App., 231,

92-93)

* * *

"5. Any set plan should have written into it

automatic mechanisms for change based upon

conditions which may arise in the com

munity." (NAACP Ex. 2, p. 7, R. Vol. IV, 6;

App., 232, 92-93)

* it *

"13. Monitoring procedures are to be so

specified that assignment adjustments will be

acted upon when trends of racial changes are

noted. These procedures are to be made spe

34

cific with respect to degrees of change and

timing of remedial actions to be taken,"

(NAACP Ex. 2, p. 8, R. Vol. IV, 6; App„ 233,

92-93)

During the course of the trial Mr. E. Brice Cunning

ham, Respondent-N A A CP's lead attorney, on

February 19, 1976, advised the Court as follows con

cerning the propriety of leaving grades K-3 in their

current neighborhood schools: (R. Vol. IV, 303; App.,

109-110)

"The members of the NAACP can see justifi

cation possibly for K through three because

we are dealing with young children, the first

time in school. I have talked with some teach

ers and they explained that these kids may lose

their or may have problems being there the

first time but for nine through twelve there is

no justification that we can see."

The Final Order allows grades K-3 to so remain in

their neighborhood schools.

The Court of Appeals recognized:

(a) that the School District is the eighth largest ur

ban school district in the country (Estes Pet. App. "C ",

131a),

(b) that the School District has been the subject of

35

desegregation litigation in various actions since 1955

(Estes Pet. App. "C", 132a),

(c) that the primary attack upon the student assign

ment plan in question is based upon the claim that the

plan cannot pass constitutional muster because of the

large number of one-race schools it establishes (Estes

Pet. App. “C", 132a),

(d) that since 1971 substantial changes have oc

curred in the School District, residential patterns of

Dallas have shifted, many areas are now naturally in

tegrated, what was formerly a majority Anglo school

system has become a predominantly minority school

system, that in 1971 the school system was 69% (sic

59%) Anglo, and that in 1975 it was 41.1% Anglo,

44.5% Black, 13.4% Mexican-American and 1% “other"

(Estes Pet. App. "C", 134a, 135a),

(e) that there may be special considerations in

volved in devising a school desegregation plan in an ur

ban area with a predominantly minority enrollment

that may justify the maintenance of some one-race

schools (Estes Pet. App. "C ", 134a),

(f) that in devising the plan in question the District

Court considered numerous proposals to desegregate

the school system, among which were plans submitted

by the original Plaintiffs, the NAACP Intervenors, the

School District, a Court-appointed expert and a tri

ethnic Amicus Curiae group (Estes Pet. App. "C ",

134a), and

(g) that after a voluminous record and holding

hearings for over a month on the feasibility and effec

tiveness of these proposals that the District Court

drew a comprehensive plan dealing, inter alia, with

special programs, transportation, discipline, facilities,

personnel, and an accountability system, as well as stu

dent assignment (Estes Pet, App. "C ", 134a).

At the conclusion of the liability phase of this action

on July 16, 1971, (as distinguished from any phase of

this case involving the nature and content of any re

medial order) the District Court made no findings that

any matters pertaining to the operation and manage

ment of the business and affairs of the School District

or any matters pertaining to the education, curricu

lum and program aspects of the School District consti

tuted a deprivation by the School District of any rights

secured any minority student by the Constitution or

laws of the United States. Further, the Court made no

findings at the conclusion of the liability phase of this

action on July 16,1971, (Brinegar Pet. App. A, A -l - A-

6) that any student by reason of his or her race, color or

national origin had been excluded from participation in,

been denied the benefits of, or been subjected to dis

crimination under any program or activity receiving

federal financial assistance as covered by the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, including Section 601 of that Act.

42 U.S.C. §2000d.

The Judge of the District Court has presided in this

second case from its beginning. From its March 10,

37

1976, Opinion and Order it is obvious that the District

Court has recognized and considered all the many com

plex factors involved in fashioning a desegregation

remedy for the School District. Over the strenuous ob

jections of the School District, the District Court an

ticipated the subsequent June 27, 1977, decision of this

Court in Milliken II and ordered comprehensive non

student assignment provisions in the remedy.2 Sum

mary examples of the non-student assignment re

quirements included in the District Court's remedy are

set out in Estes Petition Appendix "F", 152a-157a.

The Court of Appeals appears to recognize the

careful study and consideration that the District Court

had given the case and the many complex factors in

volved in fashioning the remedy. The Court of Appeals

even noted that there may be special considerations in

volved in devising a school desegregation plan in an ur

ban area with a predominantly minority enrollment

that may justify the maintenance of some one-race

schools. Nevertheless, the Court of Appeals con

sidered the number of one-race schools as controlling

and remanded the case to the District Court for the

formulation of a new student assignment plan and for

findings to justify the maintenance of any one-race

schools that may be a part of that plan.

2 Nothing contained in this brief is to be construed as a waiver by

the School District of its right on remand to object to the introduc

tion of all evidence and to all parts of any plan or proposal as might

pertain to non-student assignment matters and to object to the in

clusion of non-student assignment provisions in any remedial

order and the School District specifically reserves its right to so

object.

38

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

A. In addressing the four specific problem areas

with respect to the centra! issue of student assign

ment, Swann left school authorities and lower courts

confronted with a serious dilemma — how to reconcile

the language pertaining to racial balance or quotas with

the language concerning the elimination of every all-

Negro and all-white school. The Court of Appeals seiz

ed upon one problem area, the number of one-race

schools, and elevated it to the controlling factor to

resolve the "no racial balance or quota — elimination of

one-race schools" dilemma. This was done to accom

modate the Respondent-NAACP demand for racial

balance. The Court below in effect erroneously con

strued Swann to require that every one-race school

must be eliminated. One-race schools cannot be elimi

nated, and are not required to be eliminated, in this

large urban school system given the facts of this case.

Swann's comment that school authorities and district

judges will necessarily be concerned with the elimina

tion of one-race schools should not be read to require

that every one-race school must be eliminated or to re

quire findings to justify one-race schools. None of

Swann's language addressing that concern can be so con

strued. Contrary to Swann, the Court of Appeals has

developed a "per se rule" and made the elimination of all

one-race schools the controlling factor to be con

sidered in determining whether a remedy is consistent

with the Equal Protection Clause and this Court's

decisions in Swann and Milliken II. The one-race school

criteria seized upon by the Court of Appeals is an exam

ple of how Green v. New Kent County thinking can bring

lower courts to an erroneous interpretation of Swann in

cases involving large urban school systems. A national

educational crisis exists in large urban school systems

because some federal courts refuse to admit that Swann

must be interpreted in light of the urban condition as it

exists in these school systems. The District Court was

one federal court that did recognize this fact. New and

innovative approaches are appropriate in desegrega-

tionm atters — . . in this field the way must always be

left open for experimentation." United States v. Mont

gomery County Board of Education, 395 U.S. 225, 235 (1969).

Otherwise the judicial goal of a plan that promises

realistically to work now in such school systems will

not be reached.

B. The District Court's Final Order should be af

firmed in its entirety: Respondent-Plaintiffs'attorneys

in seeking and receiving an award of attorneys' fees

have admitted that the District Court's Final Order af

fords Black and Mexican-American students the relief

sought. The lead counsel for Respondent-NAACP has

publicly conceded that Respondent-NAACP does not

know how to eliminate certain all-black schools in the

School District.

C. The Court of Appeals' concern with the ab

sence of time and distance studies was unwarranted.

The District Court was fully aware of the realities of

time and distance. Given the evidence in the record of

3 9

40

demographic housing patterns and changes, the wide

ly separated location of predominantly Anglo students

and predominantly minority students, the location of

naturally integrated neighborhoods, and the testimony

of certain witnesses, the District Court had no need to

be concerned with formal time and distance studies. No

formal detailed time and distance studies were offered

by any party. If the District Court and the parties con

sidered that this case could be decided on the evidence

without such studies, then surely the Court of Appeals

should have been able to do so. The Court of Appeals7

concern for the absence of time and distance studies is

but further evidence that the Court of Appeals inter

prets Swann to require that every one-race school must

be eliminated.

D. "Vestiges" as used by the District Court in both

1971 and 1976 was employed in the sense of a "trace of

something formerly present," i.e., that which had once

existed but has passed away or disappeared. The dual

system was no more. Only its trace must now be re

moved from the system. Here the District Court has

found only a limited constitutional violation exists — a

trace of a former dual system. It is this trace of

something formerly present with which we are now

concerned. The District Court formulated a plan to

remedy only these "vestiges" without exceeding the

District Court's equitable powers and responsibility to

balance public and private needs. A drastic remedy con

templated by the Court of Appeals with its emphasis on

the elimination of all one-race schools is not required or

41

permitted in this case in order to remove this trace of

something formerly present. The judicial task is to cor

rect the condition that offends the Constitution. The

District Court's Final Order meets this standard.

E. The District Court correctly refused to follow

Respondent-NAACP's "single-minded commitment to

racial balance." Recognizing all the complex factors in

volved, the District Court anticipated the subsequent

June 27, 1977, decision of this Court in Milliken II and

properly considered education-oriented alternatives.

The decision of the Court of Appeals does not refer to

this Court's opinion in Milliken II. Thus the decision of

the Court of Appeals in effect interprets Swann to mean

that the non-student assignment provisions contained

in the remedial order in question, including remedial

educational programs, are not to be considered as

desegregation tools or techniques. The Court of

Appeals has made too limited a reading of Swann in the

light of this Court's decision in Milliken II.

F. The Court of Appeals has looked with approval

upon the fact that district courts have appointed bi-

racial committees to study and make recommenda

tions for school desegregation plans. Jones v. Caddo Parish

School Board, 487 F.2d 1275, 1276, 1277 (5th Cir. 1973).

While the tri-ethnic committee involved here might

not have been initially appointed to render this service,

the background, origin and development of the District

Court's Final Order is tantamount to initial appoint

ment of a tri-ethnic committee to study and make rec-

ommendations. The District Court's Final Order has

considerable support in the community among both

Anglo and minority citizens. That support is evident

from the vote in favor of the $80,000,000.00 school im

provement bond issue at the election held on December

11, 1976. That bond election carried in Black precincts

such as the East Oak Cliff area and in South Dallas.

G. Swann is to be interpreted in light of the urban

condition present in school systems such as Dallas. Un

less the District Court's realistic approach to such a

school system is affirmed by this Court, desegregation

litigation involving these school systems will go on and

on over the years and will end only when such school

systems become virtually all-black or virtually all-black

and Mexican-American. Given the origin and develop

ment of the District Court's Final Order and the facts

of this case, this is a school desegregation case in which

the District Court's Final Order should be approved

and affirmed in its entirety and over twenty-four years

of litigation brought to a conclusion.

ARGUMENT

4 2

Among the issues before the Courts below was the

constitutionality of the remedy formulated by the Dis

trict Court to eliminate the vestiges of a state-imposed

dual school system in a large urban school system. In

particular a system that is now minority Anglo, with an

ever decreasing percentage of Anglo students, that

now requires a tri-ethnic remedy and which has been

the object of ongoing litigation to formulate a remedy

since Brown II. It is obvious from the directions given

the District Court on remand that the Court of Appeals

considered the number of one-race schools to be the

controlling criteria for determining the appropriate

ness of a remedy for such school systems. That is not

what this Court said concerning one-race schools in

Swann. That is not what this Court in effect construed

Swann to mean in Milliken II.

Here, as in Swann, the central issue is that of student

assignment. Swann addressed four specific problem

areas with respect to this central issue: (1) racial

balance or racial quotas, (2) one-race schools, (3) re

medial altering of attendance zones, and (4) transporta

tion of students. (402 U.S. at 22)

However, in addressing those four problems, the

Court left school authorities and lower courts con

fronted with a serious dilemma — how to reconcile

Swann's language pertaining to racial balance or racial

quotas with Swann's language concerning the elimina

tion of every all-Negro and all-white school.

The District Court sought to articulate this dilemma

in its March 10, 1976, Opinion and Order: (Estes Pet.

App. "B ", 9a, 10a)

"In adopting a student assignment plan, this

Court is required to arrive at a delicate balance

— the dual nature of the system must be elim

43

4 4

inated; however, a quota system cannot be im

posed. The Supreme Court ruled in Swann,

supra at 26, that

[t]he district judge or school authorities

should make every possible effort to

achieve the greatest possible degree of ac

tual desegregation and will thus

necessarily be concerned with the elimina

tion of one-race schools.

"O n the other hand, the Supreme Court held

that

[ t] he con stitu tion al command to

desegregate schools does not mean that

every school in every community must

always reflect the racial composition of the

school system as a whole." (Emphasis ours)

The Court of Appeals seized upon one of the problem

areas addressed by Swann, to wit, the number of one-

race schools, and elevated that one problem area to the

controlling factor. Elevation of the one-race school

problem area to that of primary importance is the

means by which the Court of Appeals has resolved this

dilemma posed by Swann's language.

The "no racial balance or quota - elimination of one-

race schools" dilemma of Swann leads courts such as the

Court below to attempt desegregation through racial

balance by focusing on the elimination of one-race

4 5

schools as the controlling factor to be considered in de

termining whether a remedy is consistent with the

Equal Protection Clause and this Court's decisions.

In Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 200 (1973),

this Court pointed out that it has never suggested that

plaintiffs must bear the burden of proving de jure

segregation as to each and every school or student. The

Court of Appeals by its requirement for findings to

justify one-race schools has erroneously directed

judicial efforts at a remedy toward the individual school

rather than school systems.

Unless the District Court orders a racial balance plan,

the Court of Appeals may well continue to remand this

case until there is finally ordered a plan which elimi

nates all one-race schools through the use of racial

balance or quotas. In doing so the Court below must of

necessity ignore facts present in this school system and

this Court's holding in Milliken II.

Lower court interpretations of Swann, as in the Court

of Appeals, create such uncertainties with respect to

school systems such as Dallas that nothing is resolved.

Such lower court readings of Swann create such unfor

tu n ate social and economic circumstances in

metropolitan cities that the results have become a

national educational tragedy. All that now occurs un

der Swann with respect to school systems such as Dallas

is constant district court hearings, appeals and

remands. The District Court had a solution for a

national problem. The Court of Appeals rejected this

solution. The decision of the Court of Appeals should

be reversed. The decision of the District Court should

be affirmed.

In Point I of this brief the School District shall show

that the decision of the Court of Appeals is in conflict

with this Court's decisions in Swann and Milliken II. In

Point II the School District will discuss the origin of the

District Court's Final Order, the need for further word

from this Court and why the District Court's Final

Order should be affirmed in its entirety.

I.

The Elimination O f All One-Race Schools Is

Not The Controlling Factor To Be Con

sidered In Determining Whether The

Remedy Formulated By The District Court Is

Consistent With The Equal Protection Clause

And This Court's Decisions in Swann v.

Charlotte-Meckienburg Board of Education, 402 U.S.

1, And Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (Milliken

II).

The Court Of Appeals Has Misconstrued Swann's

Holding With Respect To The Central Issue Of Student

Assignment And In Particular Swann's Language

Concerning The Specific Problem Area Of One-Race

Schools.

4 6

Swann states the question to be: (402 U.S. at 22)

"(2) whether every all-Negro and all-white

school must be eliminated as an indispensable

part of a remedial process of desegregation;"

(Emphasis ours)

Swann does not require that every one-race school

must be eliminated as an indispensable part of the

remedy. But in an apparent effort to judicially sanction

the Respondent-NAACP demand for racial balance,

the Court below in effect construed Swann to require

that every one-race school must be eliminated as an in

dispensable part of the remedy. Otherwise there would

be no need on remand for District Court findings to

justify the maintenance of any one-race schools, as was

so pointedly required by the Court of Appeals.

In speaking of the "violation" phase of school

desegregation proceedings, this Court in Washington v.

Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 240 (1976), made clear, "That there

are both predominantly black and predominantly white

schools in a community is not alone violative of the

Equal Protection Clause." But as to the "remedy" phase

of school desegregation litigation, the Court below was

not disposed to permit one-race schools, even given the

facts of this case and the special conditions that exist in

this large urban school district.

If the existence of predominantly black and pre

dominantly white schools in a community is not alone a

violation of the Equal Protection Clause; then the elim

48

ination of all one-race schools should not be the con

trolling factor in determining whether a remedy is con

sistent with the Equal Protection Clause and this

Court's decisions. If such were the case, then the elim

ination of all one-race schools as such a remedy would

be directly contrary to this Court's oft-repeated

language in school desegregation cases that the nature

of the violation determines the scope of the remedy.

(Swann, 402 U.S. at 16)

If racial balance or racial quotas are not to be used as

an implement in a remedial order, then one-race

schools cannot be eliminated in this large urban school

system given the demographic phenomena present

here. As recognized by this Court in Swann, in

metropolitan areas minority groups are often found

concentrated in one part of the city. (402 U.S. at 25)

Such is the case in this School District. But also to be

considered here is the location within the School Dis

trict of naturally integrated areas and schools in rela

tion to the areas containing the remaining predomi

nantly Anglo students and the areas containing pre

dominantly Mexican-American or Black students. The

predominantly Mexican-American or Black students

reside to the south and southeast in areas distant from

the predominantly Anglo students. Separating the re

maining predominantly Anglo students and the pre

dominantly Mexican-American or Black students are

large portions of the naturally integrated areas and

schools. (Maps, Def. Exs. 1, 2 and 3; App., 219, 220, 221)

4 9

Nor is the school system required to make continual

changes in a mobile society. Change in neighborhood

patterns caused by citizens themselves can bring about