British Airways Board v. Civil Aeronautics Board Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

August 26, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. British Airways Board v. Civil Aeronautics Board Court Opinion, 1977. ed44688d-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ab22e036-b2ba-4b79-b46a-e659d4f8bf95/british-airways-board-v-civil-aeronautics-board-court-opinion. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

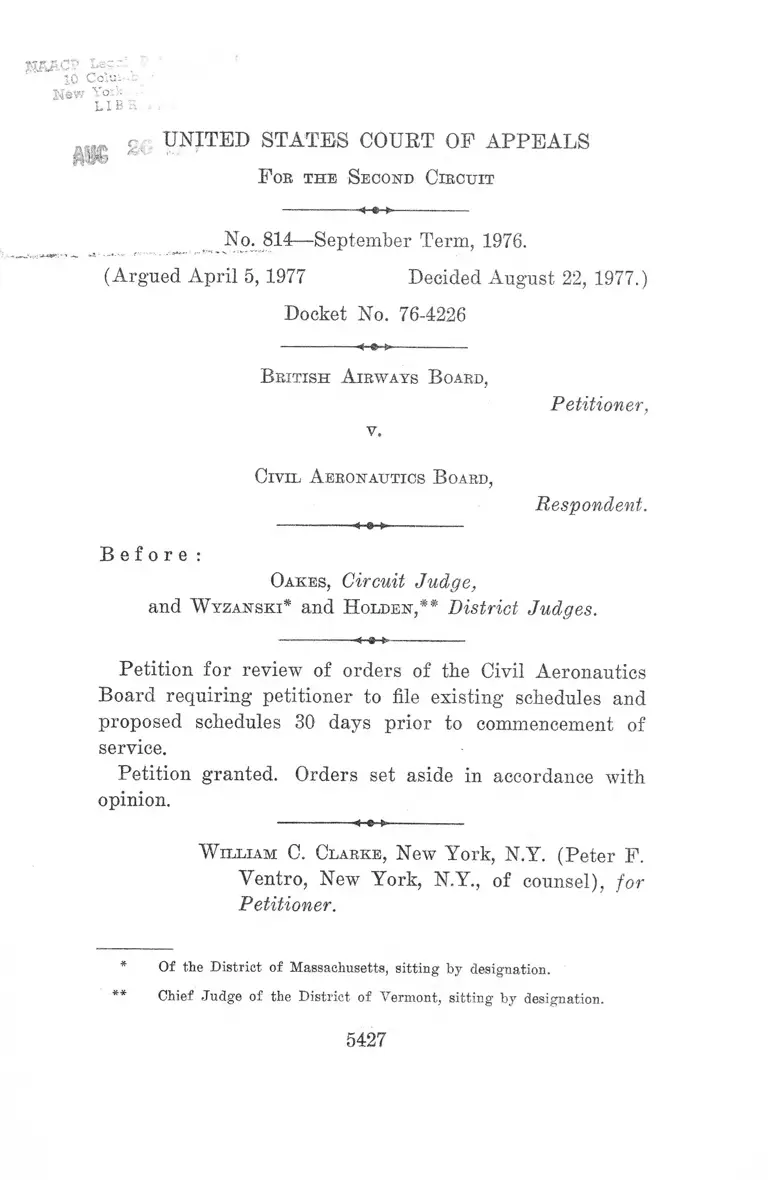

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F oe t h e S econd C ircuit

Jew York

LI S R

No. 814—September Term, 1976.

(Argued April 5, 1977 Decided August 22, 1977.)

Docket No. 76-4226

B r itish A irw ays B oard,

v.

Petitioner,

C iv il A eronautics B oard,

Respondent.

B e f o r e :

Oak es , Circuit Judge,

and W y za n s k i* and H olden ,** District Judges.

Petition for review of orders of the Civil Aeronautics

Board requiring petitioner to file existing schedules and

proposed schedules 30 days prior to commencement of

service.

Petition granted. Orders set aside in accordance with

opinion.

W il l ia m C. Clark e , New York, N.Y. (Peter F.

Yentro, New York, N.Y., of counsel), for

Petitioner.

Of the District of Massachusetts, sitting by designation.

Chief Judge of the District o f Vermont, sitting by designation.

5427

J ames C. S c h u l t z , General Counsel, Civil Aero

nautics Board (Jerome Nelson, Deputy

General Counsel, Glen M. Bendixsen, Asso

ciate General Counsel, Robert L. Toomey,

David E. Bass, Attorneys, Civil Aeronau

tics Board, Donald I. Baker, Assistant

Attorney General, Carl D, Lawson, Joen

Grant, Attorneys, Department of Justice,

of counsel), for Respondent.

Oakes , Circuit Judge:

British Airways Board (British Airways), the United

Kingdom’s government-owned air carrier, petitions for re

view of three orders of the Civil Aeronautics Board (the

Board or CAB). The first order, said to be in response to

certain United Kingdom actions taken against American-

owned carriers, required British Airways to file its exist

ing schedules of service to and from the United States by

September 28, 1976, and to file proposed schedules for any

new or modified service thirty days before making the

schedule changes. In re the Schedules of Air VBI Limited,

Order 76-9-74, No. 29778 (CAB Sept. 14, 1976). The second

order denied a stay of the first, schedule-filing order (ex

cept as to Washington-London Concorde service). Order

76-9-161 (Sept. 30, 1976). The third order was issued in

response to a letter from President Ford to the CAB, dated

October 9, 1976, in which the President stated that, because

Britain and the United States had resolved their differ

ences, “prompt rescission of the Board’s [first or schedule

filing] order . . . would be appropriate and in the interests

of our foreign policy.” The CAB then vacated its earlier

orders and terminated their effectiveness nunc pro tunc

5428

as of October 8, 1976. Order 76-10-110 (Oct. 26, 1976 ).*

Because British Airways had not filed any schedules be

tween September 28 and October 8, 1976, however, the

Board indicated in the October 26 order that the airline

would be subject to “ enforcement liability” for that period.

Id. at 3.1 2

A schedule-filing order such as the one under review

may be required under 14 C.F.R. § 213.3(c) (1975) when

the CAB finds that the government of the holder of a

foreign air carrier permit has taken action impairing or

limiting an American air carrier’s operating rights in the

foreign country. When such an order is entered against a

foreign air carrier, the carrier cannot make changes in

equipment or in times or frequency of arrival and depar

ture for thirty days, see id. § 213.3(b). The CAB can also

issue a schedule-limitation order that limits the number

of flights the subject airline can make to or from the

United States, with the order expressly subject to “ stay or

disapproval by the President of the United States within

10 days after adoption . . id. § 213.3(d). Here an order

limiting petitioner’s United States schedules was issued by

the CAB on September 29, 1976. The October 9 letter of

the President to the CAB referred to above was issued in

response to this schedule-limitation order and disapproved

1 Despite the GAB's vacation of these orders, at least the first of them

remains before us because the petition for review as to it was filed

prior to the CAB’S vacation order, and the vacation order itself was

explicitly made "subject to any necessary approval by the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.” Order No. 76-10-110, at 4;

see id. at n.6.

2 During the pendency of this review proceeding, an administrative

enforcement proceeding against British Airways was initiated by the

CAB. The enforcement proceeding has been stayed by agreement of

the parties. According to the CAB’S third order, British Airways is to be

held liable only for its failure to file existing schedules; no liability for

failure to file proposed schedules is contemplated. See id. at 3 & n.5.

5429

it within the requisite ten-day period, id. The letter then

went on to refer to the schedule-filing order here under

review.* 1 * 3

This court’s jurisdiction to review these orders is prem

ised on 49 U.S.C. § 1486. That section makes reviewable

in the courts of appeals “ [a]ny order . . . issued by the

Board . . ., except any order in respect of any foreign air

carrier subject to the approval of the President as pro

vided in [id. § 1461] . . .” Insofar as here relevant, Section

1461 requires that presidential approval be obtained when

ever the CAB desires to amend or otherwise modify a

foreign air carrier’s operating permit or certificate. Thus,

if the CAB’s schedule-filing directive to British Airways

were considered an amendment of the carrier’s permit, ad

vance presidential approval, which was not obtained, would

have been required, and this court would be without juris

diction to review the orders.

3 The letter from the President provides in full (emphasis added)

T he W hite House

Washington

October 9, 1976

Dear Mr. Chairman:

I have reviewed the Board’s proposed order in the matter of the

schedules of British Airways Board (British Airways) in Docket

29778 and the circumstances surrounding that order. In view of

the fact that the issues necessitating the actions proposed in the

order have been satisfactorily resolved with the British authorities,

I am hereby disapproving the order.

1 have further determined that prompt rescission of the Board’s

order 76-9-74, which requires the carrier to file with the Board its

existing and proposed schedules, would he appropriate and in the

interests of our foreign policy.

Bespectfully,

s / Gerald B. Ford

The Honorable John E. Bobson

Chairman

Civil Aeronautics Board

Washington, D.C. 20428

5430

We believe that the orders here involved did not amend

British Airways’ permit. In 1970, by an order approved

by the President, the Board amended the permits of 48

foreign carriers, including that of British Airways’ corpo

rate predecessor, to make the permits subject to the pro

visions of certain regulations adopted on the same date.

It was under these regulations, 14 C.F.R. §§ 213.1-.6 (1975),

that the Board issued its schedule-filing directive in the

instant case. The directive thus amounted to implementa

tion of a previously approved condition and did not modify

British Airways’ permit. An implementation effort of this

nature does not require separate presidential approval.

Dan-Air Services, Ltcl. v. GAB, 475 F.2d 408, 412 (D.C.

Cir. 1973) (per curiam). Therefore this court has juris

diction to review the orders before us.4

The fact that the CAB did not have to obtain presiden

tial approval before it ordered British Airways to file

schedules, however, does not mean that it was free as a

matter of law to ignore the disapproval embodied in the

presidential letter of October 9 relative to the schedule

filing order under review, see note 3 supra. The Board

4 The scope of review is governed by Section 10(e) o f the Admin

istrative Procedure Act, 5 TJ.S.C. $ 706(e), which provides:

To the extent necessary to decision and when presented, the

reviewing court shall decide all relevant questions of law, interpret

constitutional and statutory provisions, and determine the meaning

or applicability of the terms of an agency action. The reviewing

court shall—

(2) hold unlawful and set aside agency action, findings, and

conclusions found to be—

(A ) arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise

not in accordance with law;

( B ) ' contrary to constitutional right, power, privilege, or im

munity ;

(C) in excess of statutory jurisdiction, authority, or limitations,

or short of statutory right;

5431

recognized this by largely deferring to the President’s

wishes and vacating its schedule-filing order nunc pro tunc

as of October 8, 1976. But at the same time it insisted

that it was acting as “an independent agency,” and to show

its independence it decided to hold British Airways liable

for its failure to file existing schedules in the September

28-October 8 period, though, “to strike a balance,” not for

failure to file proposed schedules thirty days in advance,

see note 2 supra. We believe that the Board’s insistence

on its independence in this matter represents a misunder

standing of its role with regard to foreign air carriers and

of the extent of presidential primacy on issues related to

foreign affairs. We accordingly set aside the orders.

In Chicago & Southern Air Lines, Inc. v. Waterman

Steamship Corp., 333 U.S. 103 (1948), the Supreme Court

discussed the “ inversion] [of] the usual administrative

process” that Congress intended when it made CAB deci

sions relating to foreign air carriers subject to presidential

approval:

Instead of acting independently of executive control,

the agency is . . . subordinated to it. Instead of its

order serving as a final disposition . . ., its force is

exhausted when it serves as a recommendation to the

President. . . . Presidential control is not limited to a

negative but is a positive and detailed control over

the Board’s decisions, unparalleled in the history of

American administrative bodies.

Id. at 109.B A necessary implication of the President’s

“positive and detailed control” under the statute, we be- 5

5 The Chicago # Southern holdings with regard to ripeness and judicial

review have teen limited and criticized by certain courts and commen

tators. See, e.g., Zweibon v. Mitchell, 516 F.2d 594, 622-23 (D.C. Cir.

1975) (en banc) (plurality opinion of Wright, <7.); Air tin e Pilots’

Ass’n International v. Department of Transportation, 446 F,2d 236,

5432

lieve, is the power to disapprove particular actions taken

by the Board under broad regulations that the President

has previously approved. Cf. Trans World Airlines, Inc.

v. CAB, 184 F.2d 66, 71 (2d Cir. 1950) (power of President

to withdraw approval), cert, denied, 340 U.S. 941 (1951).

Were this power lacking, presidential approval of broad

regulations would in effect give the CAB carte blanche in

an area in which Congress has quite clearly indicated that

the President, not the CAB, is supreme. It is in an area

of foreign policy, moreover, in which the President’s deci

sions, to use Mr. Justice Jackson’s words for the Supreme

Court, “are delicate, complex, and involve large elements

of prophecy.” 333 U.S. at 111. In such an area, an agency

of the United States Government, even if independent for

other purposes, is subordinated to executive control “ [i]n-

stead of acting independently . . .,” 333 U.S. at 109, at

least when the Chief Executive has been given positive

and detailed control by the Congress. See Chicago &

Southern Air Lines, Inc. v. Waterman Steamship Corp.,

supra, 333 U.S. at 109-10 (President is “ the Nation’s organ

in foreign affairs” ; his powers and those of Congress are

“pooled” in this area “to the end that commercial strategic

and diplomatic interests of the country may be coordinated

and advanced without collision or deadlock between agen

cies” ) ; In re British Overseas Airways Corp. Permit

Amendment, 29 C.A.B. 583, 594 (1959) (CAB cannot be

equated with U.S. Government with regard to foreign

240-41 (5th Cir. 1971) ; Pan American World Airways, Inc. v. CAB,

392 F.2d 483, 492-93 (D.C. Cir. 1968) ; Pan American World Airways,

Inc. v. CAB, 380 F.2d 770, 775-76 (2d Cir. 1967), aff’d by equally

divided Court sub nom. World Airways, Inc. v. Pan American World

Airways, Inc., 391 U.S. 461 (1968); Miller, The Waterman Doctrine

Bevisited, 54 Geo. L.J. 5 (1965). None of these limitations or criticisms,

however, is directed at the portion of Chicago #■ Southern quoted, in text,

which involves the President’s statutory powers over CAB decisions

affecting foreign air carriers.

5433

carriers ; there is a “ division of functions,” with the Pres

ident making the final decision for the Government).

Once it is accepted that the CAB must take the Presi

dent’s word as supreme in a case of this nature, it follows

that the Board’s orders here under review must he set

aside. The Board itself recognized that it was not follow

ing the President when, in its third order, which vacated

the first two but preserved a basis for enforcement liability,

it explicitly stated that the Board’s deference to presiden

tial wishes “will not be unqualified.” Order No. 76-10-110,

supra, at 2. The President’s letter to the Board, moreover,

although not phrased as a directive, could not be more clear

as to the action that the President had “determined” to be

“appropriate and in the interests of our foreign policy.”

See note 3 supra.

That this determination was embodied in a letter issued

in response to the Board’s schedule-limitation order of

September 29, 1976, reinforces the view that the President

was exercising his full prerogative in the area and demon

strates the importance of the schedule-filing order in the

overall settlement of the then-current dispute between the

United States and Great Britain. The only action required

of the President under the regulations was approval or

disapproval of the schedule-limitation order; by inclusion

of the reference to the schedule-filing order, the President

made it clear that he was exercising the full extent of his

presidential control. The “prompt rescission” that the

President called for is not anywhere suggested to be a

partial rescission, and the common meaning of the verb

“rescind,” at least in law, involves. declaring something

(usually a contract) abrogated from its inception, so that

the parties are restored to the positions they would have

occupied had no action been taken initially, see Blank’s Law

Dictionary 1471 (4th ed. 1951). Rescission in this sense has

5434

been denied British Airways by the CAB’s preservation of

a basis for enforcement liability, contrary to the express

determination of the President.6

We therefore set aside the Board’s orders. Because we

have concluded that the orders improperly ignored a pres

idential directive, made in the exercise of his statutory and

constitutional powers, we need not reach the other attacks

on the orders made by British Airways.

Petition for review granted. Orders set aside in accor

dance with opinion.

I f there were any doubt as to the President’s intention, it is resolved

by tracing the underlying advisory memoranda. At our request the De

partment of Justice, on behalf o f the Counsel to the President, the De

partment of State, and the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Coun

sel, furnished the court with memoranda pertaining to the draft of the

President's letter of October 9. This material is short and simple.

The Department of State wrote the Office of Managament and Budget

on October 8, 1976. It pointed out that, in view of the satisfactory

solution worked out with the British, the basis for the issuance of the

schedule-filing order under review was "no longer valid,” and that

"withdrawal of the order has substantive importance, since the require

ment . . . significantly reduces the scheduling flexibility of [the British]

airlines.” State therefore recommended that the President’s letter

"strongly urge the CAB to withdraw its order 76-9-74 of September 14,

1976.”

The Office of Management and Budget’s "Memorandum for the

President," also dated October 8, points out that "State . . . recommends

that you advise the Board that recission [sic] of its September 14, 1976,

order is appropriate and in our foreign policy interests.” It goes on to

note: "In view of the foreign policy issues inherent in this case, the

interested executive agencies defer to the recommendations of the De

partment of State. The National Security Council concurs with the

Department of State recommendation.” The final draft of the letter

expressly used the term "rescission,” see note 3 supra, whieh carries with

it, we think, a definite retroactive meaning of significance, as dis

cussed in the text. Bather than "strongly urge” the agency, as State

had suggested, which would imply a power in the Board of independent

action, the final draft pointedly uses the terminology, "I have . . . deter

mined, which is consistent with an exercise of presidential prerogative,

not subject to independent action by the agency.

5435

480-8-23-77 TJSCA— 4221

MEILEN PRESS INC, 445 GREENWICH ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013, (212) 966-4177