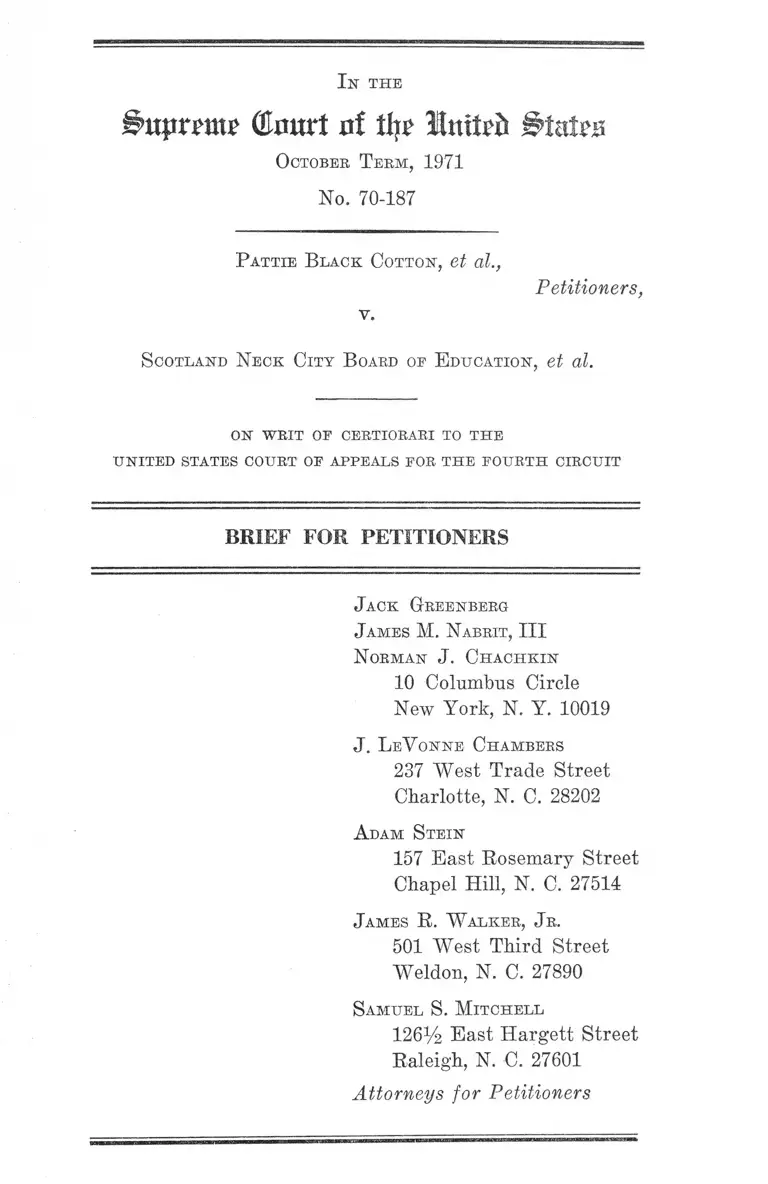

Cotton v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cotton v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education Brief for Petitioners, 1971. 2fdba372-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ab2c143b-4485-44da-9304-5cd3a16d688e/cotton-v-scotland-neck-city-board-of-education-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

( ta r t ni tty Ittitrd Bizitm

October T erm, 1971

No. 70-187

Pattie Black Cotton, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

Scotland Neck City Board oe E ducation, et al.

o n w r i t o p c e r t i o r a r i t o t h e

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS POR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

N orman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

J. L eV onne Chambers

237 West Trade Street

Charlotte, N. C. 28202

A dam Stein

157 East Rosemary Street

Chapel Hill, N. C. 27514

James R. W alker, Jr.

501 West Third Street

Weldon, N. C. 27890

Samuel S. Mitchell

126% East Hargett Street

Raleigh, N. 0 . 27601

Attorneys for Petitioners

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions B elow ........................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................... 2

Questions Presented............................................................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 2

Statement .............................................. 2

1. Proceedings B elow ................................... 2

2. The Public Schools in Halifax County and

Scotland Neck Prior to 1968-69 ........................... 6

3. Department of Justice Intervention................... 8

4. The State Consolidation and Desegregation

Plan ............. 9

5. Chapter 31—The Scotland Neck B ill ................. 11

a. The Purpose of Chapter 31 ........................... 12

b. The Effects of Chapter 31 ............................ 14

6. Events Subsequent to the Preliminary Injunc

tion ........................................................................... 18

A rgument—

The District Court Correctly Enjoined the Divi

sion of Halifax County’s System into Two Sep

arate Units Where the Changed Boundaries Would

Impede Desegregation and Where Formerly Ig

noring Such Boundaries Was Instrumental in

Promoting Segregation.............................................. 20

Introduction and Summary of Argument............... 20

I. The District Court Correctly Evaluated the

Proposed Scotland Neck Secession in Terms

of Its Effectiveness in Dismantling School

Segregation in Eastern Halifax County ....... 22

II. The Separation of Scotland Neck From the

Halifax County School System Impedes De

segregation of the Schools Involved............... 33

A. Organization of the Dual System in Scot

land Neck A re a .............................................. 33

B. The Interim Plan .......................................... 38

C. The Assignment Pattern I f Scotland Neck

Secedes; the Doughnut-Shaped Zone for

Braw ley............................................................ 39

D. The Effect of Secession on Brawley and

District I ...................................................... 43

E. The Interdistrict Transfer P lans............... 47

F. Other Effects of the Secession of Scotland

Neck .... ............................................................. 49

ii

PAGE

Conclusion 53

Ill

T able of A uthorities

Cases: page

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) ........................ ..................... ................... 23

Aytch v. Mitchell, 320 F. Supp. 1372 (E.D. Ark. 1971) 29

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....20, 22,

29, 33, 46, 51

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) ....20, 23,

29, 33

Brown v. South Carolina State Board of Education,

296 F. Supp. 199 (D. S.C. 1968), aff’d, 393 U.S. 222

(1968) ............................................................................... 50

Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School District No. 1,

Clarendon County, S. C., 429 F.2d 830 (4th Cir. 1970) 51

Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County,

Va., 332 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964) ................................ 36

Burleson v. County Board of Election Commissioners

of Jefferson County, 308 F. Supp. 352 (E.D. Ark.

1970), affirmed, 432 F.2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970) ......... 29

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 190 F. Supp. 861

(E.D. La. 1960), affirmed sub nom. City of New

Orleans v. Bush, 366 U.S. 212 (1961) ......................... 28

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S.

290 (1970) ............................. ........................................... 22

Coffey v. State Education Finance Commission, 296

F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss. 1969) .................................. 50

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) .............................. 28

IV

Corbin v. County School Board of Pulaski County, Va,,

177 F.2d 924 (4th Cir. 1949) .... ............... ...... ............... 36

Crisp v. County School Board of Pulaski County, Ya.

(W.D. Ya. 1960), 5 Race Eel. L. Eep. 721 ............... . 36

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile,

402 U.S. 33 (1971) ...............:........ ................... 21, 22, 24, 39

Evans v. Buchanan, 207 F. Supp. 83 (D. Del. 1962)....... 29

Goins v. County School Board of Grayson County, Va.,

186 F. Supp. 753 (W.D. Va. 1960), stay denied, 282

F.2d 343 (4th Cir. 1960)...................................... ........... 36

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 TJ.S. 339 (1960) ...............23, 39

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) .........................6, 8,12,16, 22, 23, 25, 32, 37

Griffin v. Board of Education of Yancey County, 186

F. Supp. 511 (W.D. N.C. 1960) ................................... 36

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ....... ... ....28, 50

Griffin v. State Board of Education, 296 F. Supp. 1178

(E.D. Va. 1969) ................................ ............................... 50

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp.

649 (E.D. La. 1961), aff’d, 368 U.S. 515 .................... 50

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County,

Ark., 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969) .............................. 29

Hawkins v. North Carolina State Board of Education,

11 Race Eel. L. Eep. 745 (W.D. N.C., March 31,

1966) ...................................... .......................................... 50

Jenkins v. Township of Morris School District, 58

N.J. 483, 279 A.2d 619 (1971)

PAGE

29

V

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F, Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala. 1967), aff’d, sub nom. Wallace v.

United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967) ..... ....... ...... ........ 50

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 448 F.2d

746 (5th Cir. 1971) ...................................... 20, 29, 30, 31, 52

Lee y. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D. N.Y. 1970,

affirmed per curiam, 402 U.S. 935 (1971)....................... 49

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) 36

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) 22

North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann, 402

U.S. 43 (1971) .......................................................... 21, 30, 49

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Commis

sion, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), aff’d 389 U.S.

571 (1968) ..................................................................... . 50

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Commis

sion, 296 F. Supp. 686 (E.D. La. 1968), aff’d, 393 U.'S.

16 (1968) ........................................................................... 50

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) .....22, 37

School Board of Warren County, Va. v. Kilby, 259 F.2d

497 (4th Cir. 1958)....................... ...................... ............. 36

Sloan v. Tenth School District of Wilson County, Tenn.,

433 F.2d 587 (6th Cir. 1970) ....... ................................. 29

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 448 F.2d

403 (5th Cir. 1971) ............ ............. ........................20, 29, 30

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) .............20, 21, 22, 24, 42, 44, 45, 46, 49, 52

PAGE

PAGE

Turner v. Littleton Lake Gaston School District, 442

F.2d 584 (4th Cir. 1971) .............................................. 5,

Turner v. Warren County Board of Education, 313

F. Supp. 380 (E.D. N.C. 1970), affirmed sub nom.

Turner v. Littleton Lake Gaston School District, 442

F.2d 584 (4th Cir. 1971) ..............................................16,

United States v. Bright Star School District i f 6, un-

reported, W.D. Ark., No. T-69-C-24, April 15,1970 ....

United States v. Crockett County Board of Education,

unreported, W.D. Tenn., C.A. No. 1663, May 15, 1967

United States v. Halifax County Board of Education,

314 F. Supp. 65 (E.D. N.C. 1970) ........... 1, 9,13,14,17,

United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353 (E.D. La.

1963), affirmed, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ........................—

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Educa

tion, No. 70-130 .....................—........................................

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Educa

tion, 442 F.2d 575 (4th Cir. 1971) .......................... 1, 26,

United States v. Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043 (E.D. Tex.

1970), affirmed, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971) ...........

United States v. Tunica County School District, 323

F. Supp. 1019 (N.D. Miss. 1970), aff’d, 440 F.2d 1236

(5th Cir. 1971) ....................................... -..... -..................

Walker v. County School Board of Floyd County, Ya.

(W.D. Ya. 1960), 5 Race Bel. L. Rep. 714 ........... .......

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 442 F.2d 570

(4th Cir. 1971) ............... .................. -.......... 5, 26, 29, 41,

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, No. 70-188 .....4,

26

29

30

30

25

42

2

29

29

50

36

42

27

V l l

Statutes: page

28 U.S.C. section 1254(1) ................. 2

1969'Session Laws of North. Carolina, Chapter 31 ..2, 3,4, 27

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 115-163.................................................... 15

Other Authorities:

U. S. Bnrean of the Census, U. S. Census of Popula

tion: 1970 General P opulation Characteristics,

North Carolina............... 40

I n the

g>ttpr?mp ( to r t nf % TUm ttb States

Ootobee T eem, 1971

No. 70-187

Pattie Black Cotton, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Scotland Neck City Boaed op E ducation, et al.

ON W RIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT' OP APPEALS POE THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals (A. 1104) is re

ported sub nom. United States v. Scotland Neck City Board

of Education, 442 F.2d 575 (4th Cir. 1971). Dissenting opin

ions by Judges Winter and Sobeloff are reported at 442

F.2d 588 and 442 F.2d 593.

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina (A. 1062) is reported

sub nom. United States v. Halifax County Board of Educa

tion, 314 F. Supp. 65 (E.D. N.C. 1970).

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered March

23, 1971. The petition for certiorari was filed May 20, 1971,

and was granted on October 12, 1971. The case was con

solidated with United States v. Scotland Neck City Board

of Education, No. 70-130, in which certiorari was also

granted October 12, 1971. The jurisdiction of the Court

rests on 28 U.S.C. section 1254(1),

Questions Presented

Whether the Court of Appeals erred by holding that new

school districts may be formed which divide a unit that is

faced with the duty to desegregate a dual system where

the changed boundaries result in less desegregation and

where formerly the absence of such boundaries was instru

mental in promoting segregation.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the constitutionality of Chapter 31

of the 1969 Session Laws of North Carolina which is set

out in the appendix to this brief, pp. 16b, et seq.

2. The ease also involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

1. Proceedings Below

This case (consolidated here with No. 70-130, United

States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education) involves

the desegregation of the public schools operated by the

Halifax County Board of Education in North Carolina.

3

The school system of some eighteen schools and slightly

more than 10,600 pupils (in 1968-69) embraces a rural area

and a number of small towns such as Scotland Neck, a

community with about 695 resident pupils. The county

has long maintained a dual system of racially segre

gated schools, and while the county school board was en

gaged in negotiating with the United States Department

of Justice about a desegregation plan, local citizens ob

tained passage of Chapter 31 of the 1969 Session Laws of

North Carolina wThich created a new independent school

system for the town of Scotland Neck and thus separated

the town and its one school from the county school system

and its desegregation plans. This case involves the con

stitutionality of Chapter 31 in the context of the desegre

gation process.

The complaint (A. 26 and amendment at A. 62) was

filed by the United States on June 16, 1969, in the Eastern

District of North Carolina seeking the desegregation of

the schools by a more effective method than the freedom

of choice plan then in effect, and seeking an injunction

against Chapter 31 on the ground that it interfered with

desegregation of the public schools of Halifax County and

denied equal protection of the laws to Negro students.

Petitioners Patty Black Cotton, et al. are Negro pupils,

parents and teachers who were permitted to intervene as

plaintiffs. The Halifax County Board of Education, the

Scotland Neck City Board of Education, the Mayor and

Commissioners of Scotland Neck and the Town of Scotland

Neck were named as defendants, and several other state

and local officials were later added as defendants.

After a three day hearing the district court entered a

preliminary injunction on August 25, 1969, restraining

implementation of Chapter 31 (A. 790). On May 26, 1970,

a final injunction was entered (A. 1084), the district court

4

holding that Chapter 31 was unconstitutional under the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

because it “was enacted with the effect of creating a refuge

for white students of the Halifax County School system”

(A. 1083). The district court order was accompanied by

a long and detailed opinion setting forth complete findings

of fact. The opinion by Judge Larkins was concurred in

by Chief Judge Butler who sat to hear a related case

involving similar questions relating to the creation of two

new school districts—Littleton-Lake Gaston and Warren-

ton—in neighboring Warren County located just west of

Halifax. (For the general location of the several districts

see Map I in Petitioners’ Brief Appendix of Maps, Tables

and Statutes.1 Map I also shows nearby Emporia, Virginia

involved in a companion case, Wright v. Council of City

of Emporia, No. 70-188.)

The Fourth Circuit, sitting en banc, reversed the injunc

tion, with Judges Sobeloff and Winter dissenting. The

opinion of the court by Judge Craven upheld Chapter 31,

concluding that the primary purpose of the law “was not

to invidiously discriminate against black students.” (442

F.2d at 582.) In the companion case involving Emporia,

Virginia, Judge Craven set out the legal rule applied to

decide these cases in the following language:

If the creation of a new school district is designed

to further the aim of providing quality education

and is attended secondarily by a modification of the

racial balance, short of resegregation, the federal

courts should not interfere. If, however, the primary

purpose for creating a new school district is to retain

as much of separation of the races as possible, the

state has violated its affirmative constitutional duty

1 This Brief Appendix is hereinafter referred to as “Maps and

Tables.”

5

to end state supported school segregation. The test

is much easier to state that it is to apply. (Wright v.

Council of City of Emporia, 442 F.2d 570, 572 (4th

Cir. 1971).)

The Court of Appeals held that the effect of the separa

tion of Scotland Neck schools and students on the desegre

gation of the remainder of the county system was

“minimal” and that the shift in .racial percentages was

“hardly a substantial change” (442 F.2d at 582).

The Court of Appeals held that the transfer plan adopted

by the Scotland Neck school board immediately after its

creation—by which 350 white and 10 black pupils would

transfer into the unit from Halifax County and 44 black

pupils would transfer out of Scotland Neck to attend

Brawley School—“would have tended toward the establish

ment of a resegregated system” and did violate the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (442 F.2d

at 583), but found the transfer plan of “no relevance”

to the constitutionality of Chapter 31 because it said that

the legislature did not know that such a plan would be

adopted (442 F.2d at 581-582, note 3). In so doing, the

Court of Appeals ignored findings to the contrary by the

district court (314 F. Supp. at 69).

The Court of Appeals’ contradiction of the district court

finding in this regard is significant since the Court of

Appeals upheld an injunction in the companion case in

volving Littleton-Lake Gaston because the record in that

case indicated legislative awareness of a comparable

transfer scheme. Turner v. Littleton Lake Gaston School

District, 442 F.2d 584 (4th Cir. 1971).

Petitions for certiorari filed by the United States and

the intervening plaintiffs were granted October 12, 1971.

6

The Court of Appeals has stayed the effectiveness of its

mandate pending this Courts’ decision, and thus the imple

mentation of Chapter 31 is still enjoined.

2. The Public Schools in Halifax County and Scotland Neck

Prior to 1968-69

Until the creation of the Scotland Neck Administrative

Unit by the North Carolina General Assembly on March 3,

1969 and by the vote of the residents of Scotland Neck

on April 8, 1969, the Halifax County Board of Education

administered all of the schools in the county except for

two areas on the northern border of the County. (See Map

II, Maps and Tables). During the 1968-69 school year

there were 10,655 students: 2,357 (22.1%) white, 8,196

(76.9%) black and 105 (1%) Indian (Table I, Maps and

Tables).

In 1964, for the first time, six black students were per

mitted to attend a formerly all-white school under a limited

free choice policy. When this Court decided Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968),

only 3% of the black children were attending school with

whites pursuant to the Board’s desegregation program.

(314 F. Supp. at 67).

At the time of Green, and a year later when this litigation

commenced, the County operated four schools which housed

all of its 2,357 white students and a few blacks, each offer

ing grades 1 through 12. They were: the Scotland Neck

School, located in the middle of the eastern portion of the

county, Enfield School about 16 miles west of Scotland

Neck, the Aurelian Springs School some 16 miles north

west of Enfield and William R. Davie approximately 8 miles

north of Aurelian Springs. (See Map II, Maps and Tables).

Superimposed upon the system of schools operated for

white children was a network of 14 black schools where in

7

October, 1968 7,446 or 90.8% of the County’s black pupils

attended school (Table I, Maps and Tables). In the eastern

portion of the county, for example, about % of a mile from

the Scotland Neck School and just outside the town limits

to the east is the Brawley School2 (A. 233). Brawley, like

Scotland Neck was a school serving grades 1 through 12.

At the high school level—grades 9 through 12—Brawley

drew students from the same geographical areas as the

Scotland Neck School (A. 273-276; 149; 821). White stu

dents from the outlying county areas rode buses to the

Town of Scotland Neck and went to the Scotland Neck

School. Black pupils rode separate buses from the same

surrounding area to the Town of Scotland Neck and went

to the Brawley School. White students in the town and

nearby areas walked to the Scotland Neck School. Black

children in the Town of Scotland Neck and close by walked

to Brawley.

In addition to Brawley, there are four black elementary

schools (grades 1 to 8) in the areas surrounding the Town

of Scotland Neck. Dawson is to the east, Tillery Chapel to

the north, Bakers to the west and Thomas Shield to the

south (Map II, Maps and Tables). At the elementary level,

Brawley served the Town of Scotland Neck and its immedi

ate environs. The black high school students in this area

had traditionally gone to Brawley. All of the white chil

dren in the areas served by these five black schools had al

ways gone to the Scotland Neck School until August, 1970

(A. 273-276; 149).

2 The Scotland Neck School is on the west side of town. The

town line separates ten acres of its campus and one four-classroom

building which are located in the County. After the new unit was

created arrangements were made to recapture these facilities for

the use of the Scotland Neck Unit by extending the boundaries of

the new unit through administrative action, and by leasing the

building from Halifax County for $1.00 per year. (314 P. Supp.

at 70).

8

This case involves the constitutional duty of North Caro

lina officials to desegregate the six schools in the Scotland

Neck-Brawley area.

Scotland Neck is a town of less than 3,000 people. It is

one mile wide at its widest and two miles long at its longest3

(Map IY, Maps and Tables). It has a resident school

population of 695 of which 399 (57.4%) are white and 296

(42.6%) black (Table IY, Maps and Tables). In October,

1968, the total attendance at the schools in the Scotland

Neck-Brawley area was 3,302: 786 (23.8%) white and 2,516

(76.2%) black (Table I, Maps and Tables). This very

nearly parallels the black/white ratio of the Halifax County

Unit as a whole which was 22.1% white and 76.9% black

(Ibid.).

3. Department of Justice Intervention

Following Green, the Department of Justice on July 27,

1968 sent a letter informing the Halifax County Board of

Education that it would institute suit unless prompt action

were taken to dismantle the dual school system in Halifax

County. The negotiations which ensued produced an agree

ment that the Board would take some desegregation steps

for the 1968-69 school year and would submit a plan for

the complete disestablishment of its dual system by early

1969 to be fully implemented for the 1969-70 school year.

The steps taken for 1968-69 were a few faculty transfers

and the transfers of grades 7 and 8 from three black schools,

and grade 7 from a fourth to four neighboring white schools.

As part of the plan, grades 7 and 8 were moved from Braw-

ley to Scotland Neck. No white students were assigned to

Brawley or to any other black school in the county.

3 It is less than % of a mile wide at its northern end where the

Scotland Neck and Brawley Schools are located (Map IV, Maps

and Tables).

9

In October, 1968, the Halifax School Board made a re

port to the Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

Its report showed student and teacher assignments at the

schools in the Scotland Neck-Brawley area as follows

(Table I, Maps and Tables) :

Pupils Teachers

Grades School White Black Total % Black W B

1 -1 2 Scotland Neck 786 193 979 19.7% 36 10

1-6; 9-12 Brawley 0 1106 1106 100% 0 40

1-8 Bakers 0 283 283 100% 1 12

1-8 Thomas Shields 0 203 203 100% 0 9

1-8 Dawson 0 459 459 100% 2 16

1-8 Tillery Chapel 0 272 272 100% 0 11

Totals 786 2,516 3,302 76.2% 39 98

Of the 193 black students assigned to Scotland Neck, 153

were the students in grades 7 and 8 who had been trans

ferred from Brawley (A. 732). The rest of the students at

Scotland Neck and the five other all-black schools had been

assigned by freedom of choice. Only 40 or about 1%% of

the black students in this area who were assigned by free

choice ended up in school with white children. No white

child chose any of the five black schools.

4. The State Consolidation and Desegregation Plan

On July 1, 1968 the Halifax Board wrote to the North

Carolina Department of Public Instruction requesting that

it propose to the Board a desegregation plan which would

provide “ the most effective organizational patterns for the

county schools in order to insure the best education possible

for the children” (314 F. Supp. at 68). A committee of

staff members of the State Department of Public Instruc

tion and other educators made a detailed survey of the

system and made recommendations to the local board

10

(A. 587). The committee was directed by Dr. J. L. Pierce,

Director of the Division of School Planning of the state

department who was a former teacher, coach and principal

at the Scotland Neck School (A. 972).

The committee made several long range recommenda

tions and also made recommendations for an Interim Plan

to meet immediate educational needs. The principal long

range recommendations were to construct two new high

schools to replace the nine high schools operating in the

county (A. 597-605). To be implemented, the long range

plan would require political and financial arrangements

that would take some time to accomplish.

The Interim Plan (A. 606) was designed for immediate

implementation. It proposed an organization of the schools

which would effectively break up the classical features of

the dual structure in Halifax County. It was essentially

a consolidation plan to eliminate the duplication inherent

in a typical rural segregated school system. Thus, in the

small towns such as Scotland Neck and Enfield, where

there had been white schools and black schools offering

the same grades and serving the same areas, the schools

were consolidated. The result of the plan was the elimina

tion of five of the nine high schools and the creation of

attendance zones for the elementary schools.

In the Scotland Neck-Brawley area which was designated

District I, a high school district was established which

covered the same area formerly served by the Scotland

Neck and Brawley schools (Map III, Maps and Tables).

The State recommended that all 10th through 12th grade

students (white and black) in District I attend Scotland

Neck and that all 8th and 9th grade students attend Brawley.

At the elementary level, students in grades 1 through 7

from the Town of Scotland Neck and its immediate en

11

virons would go to Brawley and the junior high site at

Scotland Neck (A. 606). Elementary zone lines were to be

established for grades 1-7 around the four outlying ele

mentary schools (Bakers, Dawson, Thomas Shields and

Tillery Chapel).

The state department completed its survey and recom

mendations in September, 1968 (A. 233-234). On December

17, 1968, the Board prepared a Table projecting student as

signments by race for the state department’s Interim

Plan (A. 681-682). These December, 1968 projections as

compared to October, 1968 percentages and grade organiza

tions are as follows (see Tables I and II, Maps and Tables):

District I

______________ PnpilsGrades School

5-6;

10-12 Scotland Neck

1-4;

7-9 Brawley

1-8 Bakers

1-8 Thomas Shields

1-8 Dawson

1-8 Tillery Chapel

Totals

White Black Total

325 640 965

330 740 1070

6 387 393

68 340 408

44 570 614

31 378 409

804 3055 3859

1968-69

Grades Black

%

Black

66.3% 1-12 19.8

69.2% 1-12 100

98.5% 1-8 100

83.3% 1-8 100

92.8% 1-8 100

92.4% 1-8 100

79.2%

The State Plan was not submitted to the Department of

Justice. Instead, the Scotland Neck Bill was introduced

into the legislature in January, 1969 and a free choice

plan was submitted to the Department of Justice in

February.

5. Chapter 31— The Scotland Neck Bill

In the summer of 1968, Scotland Neck residents became

fully aware that major changes in school assignments would

12

be finally required. They learned through the press that

Green had prompted the Halifax Board to seek recom

mendations for a desegregation plan from the State De

partment of Public Instruction. The Scotland Neck Com

monwealth gave prominent coverage to the negotiations

with the Government. On August 9, 1968, under a headline

“ County Ordered to End Dual System,” the paper reported

that freedom of choice was not desegregating the schools

and there are available “ ‘other ways, such as unitary

geographic attendance zoning or some form of grade re

organization or consolidation, promising speedier and more

effective conversion to a unitary system’ ” (A. 761).

A week later, the paper reported the terms of the agree

ment between the Board and the Government. “ [SJeventh

and eighth grades of Scotland Neck and Brawley schools

will be consolidated for the 1968-69 term into one junior

high school” and complete disestablishment of the dual

system in the county and in Scotland Neck will occur “at

the beginning of the 1969-70 school year” .

a. The Purpose of Chapter 31.

The district court found and the defendant had conceded

that one of the purposes of the proponents was to carve

out a school system with a racial ratio sufficiently tolerable

to whites to stem the exodus to private segregated schools4

from an area where the ratio was perceived to be intoler

able to whites.

4 “ The testimony and the candid admissions of counsel also indi

cate that the desire to preserve an acceptable white ratio in

the school system was a factor behind the passage of the act.

Mr. Harrison stated that he told the legislature that white

children were going to private schools and that something

needed to be done to retain the support of white people for

the public schools. (Henry Harrison’s Deposition, p. 18). Mr.

Shields and Mr. Overman both testified that they felt that

integration would encourage the growth of the all-white private

schools. (Overman’s Deposition, pp. 217-218, Shields’ Deposi-

13

“After closely scrutinizing the record and after care

fully considering the arguments of counsel, this Court

is of the opinion that the following motivating forces

were responsible for the design of the legislation cre

ating the separate Scotland Neck school district: (1)

the desire to improve the educational level in the Scot

land Neck schools, the present conditions in those

schools having been brought about by a lengthy his

tory of neglect and discrimination with respect to

financial allocations to the Scotland Neck schools by

the Halifax County Board of Education; (2) a desire

on the part of the leaders of Scotland Neck to preserve

a ratio of black to white students in the schools of

Scotland Neck that would be acceptable to white

parents and thereby prevent the flight of white students

to the increasingly popular all-white private schools

in the area; (3) a desire on the part of the people of

Scotland Neck to control their own schools and be in

a position to determine their direction with more final

ity than if the schools were a part of the Halifax

County system.” (314 F. Supp. at 72).

Judge Larkins did not determine which of the purposes

was predominant, but said each was significant.

“In ascertaining such a subjective factor as motiva

tion and intent, it is of course impossible for this Court

to accurately state what proportion each of the above

reasons played in the minds of the proponents of the

bill, the legislators or the voters of Scotland Neck,

tion, pp. 70-71). Mr. C. M. Moore said that it was his opin

ion that the independent school system would be a better al

ternative than the private schools. (Moore’s Deposition, pp.

18-19). Mr. Shields testified to the same thing and said that

most of the adults in Scotland Neck held the same opinion.

(Shields Deposition, pp. 23-26).” (314 F. Supp. at 73). (See

A. 984.)

14

but it is sufficient to say that the record amply sup

ports the proposition that each of the three played

a significant role in the final passage and implementa

tion of Chapter 31.” (314 F. Supp. at 72).

The majority of the Court of Appeals canvassed the

record and determined that the purposes were as Judge

Larkins had found, but concluded that benign objectives

of quality education and local control predominated (442

F.2d at 582). Judges Sobeloff and Winter came to the

opposite conclusion. They believed that the record showed

beyond question that the separation of Scotland Neck from

Halifax County was conceived as a segregation plan (442

F.2d at 592, 598-600).

We agree with the dissenting judges below. But we think

it would unecessarily complicate the case to recite all the

facts which demonstrate that Scotland Neck’s claims of

legitimate non-racial motives are hollow, since Scotland

Neck concedes one of its purposes was to accommodate

the racial prejudices of its white patrons and since the

record is conclusive that the scheme would have substantial

discriminatory effects.

b. The Effects of Chapter 31.

In the Spring of 1969, after the election by the Scotland

Neck voters, the new district immediately took steps to

establish a new administrative unit. One of the first

actions taken was to establish a transfer plan to allow

students residing outside of the city limits to attend the

Scotland Neck school. The new Board adopted a tuition

plan whereby families would be charged $100 tuition for

the first child registered and $25.00 for each additional

child with a maximum of $150 per family. Meanwhile,

the County School Board accommodated this policy by

permitting transfers into the county from Scotland Neck

15

without tuition and releasing comity children who sought

transfer to the new unit.6

The Scotland Neck Unit began with a resident student

population of 695 of whom 399 (57.4%) were white and

296 (42.6%) black. The transfer plan brought in 350 whites

and 10 blacks; no whites and 44 blacks transferred out.

The net result was an anticipated enrollment of 1,011 which

will be 74.1% white. (Table IV, Maps and Tables; A. 522-

524)).

The Court of Appeals thought that the transfer plan

which it found to be unconstitutional had “no relevance”

to the constitutionality of Chapter 31, because it said

“there is nothing in the record to suggest that the Legisla

ture had any idea that the Scotland Neck Board would

adopt a transfer plan after the enactment of Chapter 31

wrhich would have the effect of increasing the percentage

of white students” (442 F.2d at 581-582, note 3). However,

the Court of Appeals overlooked a district court finding

of fact which shows that the legislature did know of the

transfer plan:

In November 1968, a group consisting of Frank

Shields, the future chairman of the Scotland Neck

City Board of Education, C. Kitchin Josey, Henry

Harrison, and Thorne Gregory, the State representa

tive from the area, visited the Tryon City unit, at

that time the smallest school unit in the State with

823 students enrolled during the 1968-69 school year.

At that time, 974 pupils vrere attending the schools

within the corporate limits of Scotland Neck, and it

was expected that, with transfer, any new administra-

6 Children attending schools outside of the administrative unit

where they live may do so only upon the agreement of both the

unit of residence and the receiving unit. Units are permitted to

establish tuition charges for non-resident students but are not re

quired to do so. N.C. Gen. Stat. §115-163.

16

live unit would have approximately the same number

of pupils. (314 F. Supp. at 69; emphasis added.)6

Subsequently, Representative Thorne Gregory intro

duced and sponsored the bill, and served as Chairman

of the House Finance Committee which approved it

(A. 209). Since Scotland Neck had only 695 resident pupils

it was obvious that planning for about a thousand students

in the new administrative unit was based on a substantial

number of transfers. Moreover, since nearly one-half—387

of the 786— of the white pupils attending the historically

all-white school were from outside the town, it was equally

obvious that the expected transfers would increase the

percentage of white students in Scotland Neck School.7

It was only after the preliminary injunction was entered

that the Scotland Neck Board suggested some control of

its transfer policy (A. 796). But it has stubbornly refused

to give up the idea entirely. As Judge Winter observed:

“ This proposal has not yet been finally abandoned. In

oral argument before us, counsel would not tell us forth

rightly that this would not be done, but rather, equivocally

indicated that the proposal would be revived if we, or the

district court, could be persuaded to approve it.” (442 F.2d

at 592). The obvious reasons that Scotland Neck has been

6 This finding was fully supported by the record. See Depositions

of Overman (A. 299), Harrison (A. 366-67), and Shields (A. 422).

7 Aside from the many consolidations of administrative units in

North Carolina in recent years (A. 580-A. 583) ; Turner v. Warren

County Board of Education, 313 F. Supp. 380 (E.D. N.C. 1970),

there had been no new units established in North Carolina since

1953 until the post-Green 1969 Legislature created the small units

of Scotland Neck, Littleton Lake— Gaston and Warrenton (A. 584).

It is highly unlikely, therefore, that the Scotland Neck proponents

would have sought to establish the smallest unit in North Carolina,

particularly where North Carolina law allowed for the kind of

transfer plan which was established. See note 5, supra.

17

reluctant to relinquish its ability to accept transfers are

that with only 695 students it would be considerably

smaller than the smallest school district now existing in

North Carolina making it incapable of even approximating

an adequate educational program and because its bound

aries exclude nearly one-half of its traditional white

patrons.8

In addition to the transfer plan, worked out with the

Halifax Board, Scotland Neck arranged with State educa

tion officials to extend the boundaries of the unit so as to

include the grounds of part of the Scotland Neck School

campus which was on the county side of the town line.9 It

also successfully negotiated with the Halifax Board to lease

the four classroom school building located on the ten acre

site for $1.00 per year. (314 F. Supp. 70-71; A. 294).

When this case came on for hearing on the motion of the

United States for a preliminary injunction on August of

1969, the Halifax Board was planning to assign its children

by freedom of choice. The facts before the district court

were that 350 of the 387 white children wrho lived in the

county and who had attended Scotland Neck School in

1968- 69 (A. 250) had paid a deposit on their tuition to re

turn for the 1969-70 school year and that the five black

schools in the area would be at least 97.8% black. There was,

of course, no assurance that the handful of whites who had

not transferred to Scotland Neck would not do so later

(A. 522) or would show up at the black schools. The only

differences between the school boards’ proposals for the

1969- 70 school year and the situation which had existed at

the Scotland Neck School in 1968-69 were that about half

of the white children would pay tuition and the black ratio

would have increased from 19.8% to 25.9% (Maps and

8 See note 7, supra.

9 See note 2, supra.

18

Tables, Tables I and IV). The black schools would remain

all-black or virtually all-black.

6. Events Subsequent to the Preliminary Injunction

On November 24, 1969, the district court directed the

Halifax County Board of Education to submit a desegrega

tion plan on December 15 (A. 924). On that date, the Board

reluctantly submitted the State’s Interim Plan, indicating

that it knew of no better plan to disestablish the dual system.

On May 19, 1970, Judge Larkins approved the Interim

Plan and ordered that it be fully implemented by June 1,

1970.

Following the final judgment in this case enjoining Chap

ter 31, entered on May 26, 1970, the Halifax School Board

filed a motion (A. 1089) requesting that it be permitted to

implement the Interim Plan except in Scotland Neck where

it proposed to assign all town students to the Scotland Neck

School (See Map IV, Maps and Tables). Both the United

States and the private plaintiffs objected. The Government

correctly characterized the motion as an application for a

stay pending appeal (A. 1092). The Board attached a Map

(Exhibit A ) to its motion which shows what District I

would look like if both the Interim Plan and the Scotland

Neck Unit were put into effect (Map IV, Maps and Tables).

The Brawley zone would entirely encircle the Town of Scot

land Neck—like a doughnut—instead of including the Town

of Scotland Neck as would be accomplished by the Interim

Plan. Scotland Neck School would continue to serve Scot

land Neck children in grades 1 through 12. All high school

students in District I outside of the town limits would be as

signed to Brawley rather than to Scotland Neck as would

happen under the Interim Plan. The Board indicated on

the Map the number of children by race residing in each

zone as follows:

19

Pupils

Grades School White Black Total % Black

Scotland Neck Unit

1-12 Scotland Neck 399 296 695 42.6

Remainder of District I

1-12 Brawley 83 805 888 90.7

1-8 Bakers 9 357 366 97.5

1-8 Thomas Shields 85 233 318 73.2

1-8 Dawson 60 388 448 86.6

1-8 Tillery Chapel 22 211 233 90.6

Presumably these would be the assignments if the Scot

land Neck IJnit were allowed to operate but were subject

to the Court of Appeals’ injunction against permitting

transfers in or out.

20

ARGUMENT

The District Court Correctly Enjoined the Division of

Halifax County’s System into Two Separate Units Where

the Changed Boundaries Would Impede Desegregation

and Where Formerly Ignoring Such Boundaries Was

Instrumental in Promoting Segregation.

Introduction and Summary of Argument

We submit in Part I, infra, that the decision of the dis

trict court is consistent with the basic principles enun

ciated in this Court’s various school desegregation decisions

following Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

{Brown 1 ) ; 349 U.S. 294 (1955) {Brown 11), including the

most recent decisions in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), and companion

cases. We believe that the Court of Appeals departed from

those principles in important respects. In particular, we

urge that the district court was correct in evaluating Chap

ter 31 in relation to its effect on the various desegregation

alternatives available in Halifax County. We think the

Court of Appeals erred by adopting a rule that Chapter 31

should be sustained unless plaintiffs proved that its “pri

mary purpose is to retain as much separation of the races

as possible. The Fifth Circuit has applied a correct rule

m deciding similar cases, namely, that districts engaged in

the desegregation process may not make boundary changes

which impede desegregation, particularly where such boun

daries were ignored to facilitate a dual system. See, e.g.,

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education ( Calhoun County

School System and City of Oxford School System), 448

F.2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971); Stout v. Jefferson County Board

of Education, 448 F.2d 403 (5th Cir. 1971).

21

In Part II, below, we focus on tlie facts o f Halifax County

and urge that the district court was correct in ruling that

the proposed separation of Scotland Neck does impede de

segregation, while the Court of Appeals erred by labeling

the change “minimal” and “hardly substantial” in its im

pact on the desegregation process. We show that the dual

system in Halifax County was long sustained and facilitated

by ignoring boundaries of the kind now erected to maintain

Scotland Neck School as a majority white school while

nearby Brawley and four other black schools will be main

tained as black institutions. The proposed separation of

Scotland Neck is in conflict with the requirement that “ school

authorities should make every effort to achieve the greatest

possible degree of actual desegregation” (Swann v. Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 26 (1971); Davis v. Board of

School Commissioners, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971)), and impedes

the use of conventional desegregation techniques, e.g., the

“pairing” of nearby schools (Swann, supra at 27); see also

North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann, 402

U.S. 43 (1971). While no particular degree or percentage

of racial balancing is required by the Constitution, the

shifting percentages caused by the separation of Scotland

Neck would continue existing all-black schools and schools

that are “ substantially disproportionate in their racial com

position” (Swann, supra, 402 U.S. 1, 26).

22

I.

The District Court Correctly Evaluated the Proposed

Scotland Neck Secession in Terms of Its Effectiveness

in Dismantling School Segregation in Eastern Halifax

County.

The district court had the crucial responsibility to see to

it that all vestiges of state imposed segregation in Halifax

County be eliminated forthwith. Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U.S. 483 (1954); 349 U.S. 294 (1955); Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 403

(1968); Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968);

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968);

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S.

19 (1969); Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board,

396 U.S. 290 (1970); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971). It is

beyond question that a typical pattern of a racially segre

gated dual school system which had been erected pursuant

to the Constitution and laws of the State of North Carolina,

continued to exist in rural Halifax County almost undis

turbed when this case came before the district court in

August and December of 1969. See Part II, infra. In this

case the district court thought that its duty “under this

Court’s mandate to eliminate racially separate public

schools established and maintained by state action” {Swann,

supra, 402 U.S. 1, 5), was to compare the proposed seces

sion of Scotland Neck from Halifax County with other pro

posals in terms of their relative effectiveness in dismantling

school segregation root and branch. Green v. Cou/nty School

Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 403 (1968). Applying

this standard, the district judges found that the operation of

the new school unit would impede rather than further de

23

segregation. The court therefore enjoined its operation and

ordered the Halifax County Board to implement the more

effective plan which had been proposed by North Carolina’s

Department of Public Instruction.

We think that this approach was entirely consistent with

this Court’s school desegregation decisions. The novelty of

a state law changing a district’s boundaries in the face of

desegregation does not avert Brown’s basic thrust. Brown

II envisioned that the equitable power of the district courts

ought to be addressed to revision of “ school districts” as

well as individual schools and attendance areas. This was

assumed by the Court in enumerating factors that might

justify delay in immediate desegregation:

To that end the courts may consider problems related

to administration, arising from the physical condition

of the school plant, the school transportation system,

personnel, revision of school districts and attendance

areas into compact units to achieve a system of deter

mining admission to the public schools on a nonracial

basis, and revision of local laws and regulations which

may be necessary in solving the foregoing problems.

(349 U.S. at 300-301; emphasis added.)

In declaring segregation unconstitutional; the Court made

plain that “all provisions of federal, state, or local law-

requiring or permitting such discrimination must yield

to this principle” (Brown II, supra, 349 U.S. at 298).

Cf. Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960).

The Court announced in Green and reaffirmed in Swann

that a “ school authority’s remedial plan or a district

court’s remedial decree is to be judged by its effectiveness.”

402 U.S. 1, at 25. Green said that school boards had “the

affirmative duty to take whatever steps might be necessary

to convert to a unitary system in which racial discrimina

24

tion would be eliminated root and branch.” 391 U.S. at

437-438. Swann articulated further guidelines including,

inter alia, the requirement that district judges and school

authorities “make every effort to achieve the greatest

possible degree of actual desegregation” ; the articulation

of “a presumption against schools that are substantially

disproportionate in their racial composition” with the

burden on school authorities to justify any one-race schools

as not resulting from past discriminatory action; and the

endorsement of the use of drastically altered attendance

zones, and techniques of pairing and non-contiguous zoning

to dismantle segregated systems. 402 U.S. at 26-28. See

also Davis v. School Commissioners of Motile County, 402

U.S. 33, 37 (1971). Moreover, the Court made it clear

that assignment plans are “not acceptable simply be

cause . . . [they appear] to be neutral” if they fail to

counteract the continuing effects of past discrimination.

402 U.S. at 28.

Swann also reflected the Court’s understanding of the

manifold means by which school authorities control the

racial composition of schools, noting the great influence

exerted by decisions about school location and construc

tion, and requiring that Court’s look to the future to pre

vent such decisions from being used to perpetuate or

reestablish dual systems. 402 U.S. at 20-21. Finally,

Swann reemphasized the broad remedial discretion of the

district judges where school authorities have defaulted

in their constitutional obligation to provide a racially non-

discriminatory system of public schools. 402 U.S. at 15-18,

25, 28, 31.

As previously mentioned the district court concluded

that Chapter 31 “was enacted with the effect of creating

a refuge for white students of the Halifax County School

system, and interferes with the desegregation of the Hali-

25

fax County School system, in accord with the plan adopted

by said Board to be implemented on or before June 1,

1970.” 314 F. Supp. at 78. This conclusion, buttressed by

detailed fact-findings, supported the decision to enjoin

Chapter 31 as an interference with the best available

desegregation plan and is in accord with Green and Swann.

The Court of Appeals took a very different approach.

It began by assuming that the withdrawal of a small area

in the middle of the eastern portion of Halifax County

at a time when the Halifax School Board was under an

immediate duty to produce and implement an effective

school desegregation plan was to be viewed as a normal

creation of a political entity by the State of North Carolina:

Appellees urge in their brief that conceptually the

way to analyze this case is to “view the results of

severance as if it were part of a desegregation plan

for the original system.” We do not agree. The

severance was not part of a desegregation plan pro

posed by the school board but was instead an action

by the Legislature redefining the boundaries of local

governmental units. 442 F.2d at 382-83.10

Rejecting the standard of Green requiring the selection

of the most effective plan, the Court of Appeals designed

the “primary purpose” test to determine whether the new

school unit would violate the Fourteenth Amendment.

If the creation of a new school district is designed

to further the aim of providing quality education and

10 The court went on to assume “For the sake of argument that

appellees’ method of analysis is correct” and concluded “that the

severance of Scotland Neck students would withstand constitu

tional challenges.” 442 F.2d at 583. In our next argument (II),

we demonstrate why the district court was correct in its determi

nation that the new unit would impermissibly impede desegregation

in Halifax County.

2 6

is attended secondarily by a modification of the racial

balance, short of resegregation, the federal courts

should not interfere. If, however, the primary purpose

for creating a new school district is to retain as much

of separation of the races as possible, the state has

violated its affirmative constitutional duty to end state

supported school segregation. The test is much easier

to state than it is to apply.

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 442 F.2d 570, 572

(4th Cir. 1971).11 In applying this test to Scotland Neck,

the majority of the Court of Appeals concluded that “ The

purpose of Chapter 31 was not to invidiously discriminate

against black students in Halifax County . . ” (442 F.2d

at 582). We agree with the dissenting judges below that

even if the primary purpose test were appropriate, the

record here decisively reveals an overriding motive of

segregation.12 However, the analysis employed by the

11 The rule which applied to the three cases which were decided

together (Emporia, Scotland Neck and Turner v. Littleton-Lake

Gaston School District, 442 F.2d 584 (4th Cir. 1971), was most

fully discussed in Emporia.

12 Judge Sobeloff applied the majority’s test (442 F.2d at 598-60)

and came to the “conclusion that race was the dominant considera

tion and that the goal was to achieve a degree of racial apartheid

more congenial to the white community.” 442 F.2d at 600. Judge

Winter also reviewed the facts, 442 F.2d at 591-92, and reached

the same result. “ On the facts I cannot find the citizens of Scotland

Neck motivated by the benign purpose of providing additional

funds for their schools; patently they seek to blunt the mandate

of Brown.” 442 F.2d at 592. We would only add a brief discussion

of two matters to what Judges Sobeloff and Winter have said.

Judge Craven found for the majority that the unconstitutional

transfer plan did not affect the constitutional validity of Chapter

31 (442 F.2d at n. 3, 581-82) even though a similar plan was

relevant m determining the constitutional invalidity of the new

district in Littlet on-Lake Gaston (442 F.2d n. 2, 587) because the

legislature did not know of the proposed transfer plan for Scot

land Neck but did for Littleton-Lake Gaston. Judges Sobeloff and

Winter convincingly found the transfer plan very relevant to the

27

Court of Appeals is considerably more pernicious in terms

of the future course of school desegregation than in its

application to a particular case.13

The “primary purpose” doctrine is a dangerous departure

from the firmly established principles worked out by this

Court and lower courts since Brown to ensure that all the

interlacing laws, practices and customs which have sup

issue of purpose. 442 F.2d at 591-92; 442 F.2d 598-99. What is

conclusive, however, is the district court’s specific finding based

on substantial evidence that Representative Gregory, who intro

duced and shepherded Chapter 31 through the State House, had

full knowledge of the transfer plan. See p. 15, supra. Moreover,

the law did not take effect until after a vote of the residents of

Scotland Neck where the issue was supported by the same people

who sought its passage in the legislature and who established the

transfer plan immediately after its implementation. Finally, the

transfer plan was readily foreseeable since it was permissible under

state law. See note 5, supra.

Second, Judge Craven in finding the selection of the town boun

daries to he a “ natural geographic boundary” and seeing “no indi

cation that the geographic boundaries were drawn to include white

students and exclude black students . . .” 442 F.2d at 582, thought

that this pointed towards a benign purpose. We dispute both asser

tions. We know of nothing “natural” about the political boundaries

of a town. See pp. 39-40, infra. And we think that the selection

of Scotland Neck, which is the only area of eastern Halifax County

which has a majority white student population, raises an inference

of racial motive. Map IV, Maps and Tables; see pp. 39-40, infra.

13 Judge Sobeloff observed: “ I find no precedent for this test

and it is neither broad enough nor rigorous enough to fulfill the

Constitution’s mandate. Moreover, it cannot succeed in attaining

even its intended reach, since resistant white enclaves wall quickly

learn how to structure a proper record—shrill with protestations

of good intent, all considerations of race muted beyond range of

the court’s ears.” 442 F.2d at 594. The doctrine will trap federal

courts “ in a quagmire of litigation. The doctrine formulated by

the court is ill-conceived and surely will impede and frustrate

prospects for successful desegregation. Whites in counties heavily

populated by blacks will be encouraged to set up, under one guise

or another, independent school districts in areas that are or can be

made predominantly white.” 442 F.2d at 600. See also, Brief for

Petitioners, Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, No. 70-188,

pp. 37-46.

ported dual school systems are dismantled and abolished.

It is fundamentally wrong, therefore, to say as the Court

of Appeals has said, that an act of the legislature aimed at

altering the structure of a single school system amidst a

desegregation controversy is to be judged by its “primary

purpose” and not by its effect on the desegregation in the

locality. It was error to require that plaintiffs prove the

“primary purpose” to segregate where they have shown

that the effect of the law impedes desegregation.

It was recognized by this Court from the start that school

segregation is the product of a whole battery of devices

rooted in state action. A variety of schemes and arrange

ments have cropped up over the years which served to with

hold the promise of Brown. The Court has rejected time

and again claims that the action of one state official or

agency or another has some kind of insulation from judicial

scrutiny. This has been so because:

In short, the constitutional rights of children not to be

discriminated against in school admission on grounds

of race or color declared by this Court in the Brown

case can neither be nullified openly and directly by state

legislators or state executive or judicial officers, nor

nullified indirectly by them through evasive schemes for

segregation whether attempted “ingeniously or in

genuously.”

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 17 (1958). See also, Bush v.

Orleans Parish School Board, 190 F. Supp. 861 (E.D. La.

1960), aff’d sub nom. City of New Orleans v. Bush, 366 U.S.

212 (1961); Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964);

and see the authorities collected in Judge Sobeloff’s dissent

below, 442 F.2d at 593-594, nn. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. See also cases

invalidating a host of private school tuition grant schemes

infra, Part II, note 26.

29

The Court of Appeals acknowledged in the Emporia case

that the device of carving up school districts into a number

of separate units posed a “ serious danger” of obstructing

desegregation. Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 442

F.2d 570, 572 (4th Cir. 1971). This danger has been clearly

perceived and decisively dealt with by the lower federal

courts. It is very significant that every such attempted

secession which we have found reported in the lower federal

courts—with the sole exception of the Scotland Neck and

Emporia cases—has resulted in a decision disapproving

such secessions as unconstitutional evasions of Brown.

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education (Calhoun County

School System and, City of Oxford School System), 448

F.2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971); Stout v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 448 F.2d 403 (5th Cir. 1972); Burleson v. County

Board of Election Commissioners of Jefferson County, 308

F. Supp. 352 (E.D. Ark. 1970), affirmed, 432 F.2d 1356 (8th

Cir. 1970); Turner v. Warren County Board of Education,

313 F. Supp. 380 (E.D. N.C. 1970), affirmed sub nom. Turner

v. Littleton-Lake Gaston School District, 442 F.2d 584 (4th

Cir. 1971); Aytch v. Mitchell, 320 F. Supp. 1372 (E.D. Ark.

1971); cf. Jenkins v. Toivnship of Morris School Dist., 58

N.J. 483, 279 A.2d 619 (1971). In each of these cases an

attempted secession was struck down as an interference with

desegregation.

Similarly, in a long series of cases where existing school

districts have been established on a racially segregated

basis, the courts have ordered desegregation plans which

effectively merged racially separate districts. Haney v.

County Board of Education of Sevier County, 410 F.2d 920

(8th Cir. 1969); United States v. Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043

(E.D. Tex. 1970), affirmed, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971);

Evans v. Buchanan, 207 F. Supp. 820, 825 (D. Del. 1962);

Sloan v. Tenth School District of Wilson County, Tenn.,

30

433 F.2d 587, 588 (6th Cir. 1970) (mentioning prior pro

ceedings involving merger of three overlapping districts);

United States v. Bright Star School District # 6 , nnreported,

W.D. Ark. No. T-69-C-24, April 15, 1970; United States v.

Crockett County Board of Education, nnreported, W.D.

Tenn., C.A. No. 1663, May 15, 1967.

The two recent Fifth Circuit decisions in Lee and Stout,

both decided since this Court’s decisions in Swann and com

panion cases provide the approach which we believe should

be used in deciding such controversies. The decision in

Stout, supra, by a unanimous panel of Judges Thornberry,

Clark and Ingraham, held that splinter school districts,

albeit valid under state law, need not be recognized where

they thwart implementation of a unitary school system. The

court relied upon this Court’s decision striking down the

North Carolina Anti-Bussing statute, North Carolina State

Board of Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43, 45 (1971), quot

ing the following language from that opinion by the Chief

Justice:

.. . [I ] f a state-imposed limitation on a school author

ity’s discretion operates to inhibit or obstruct the

operation of a unitary school system or impede the

disestablishing of a dual school system,, it must fall;

state policy must give way when it operates to hinder

vindication of federal constitutional guarantees.

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 448 F.2d

403, 404 (5th Cir. 1971).

The opinion in Lee, supra, by Judge Wisdom (joined

by Judge Simpson, as on this issue by Judge Coleman)

held that in confronting the secession of the City of Oxford

school system from the Calhoun County system the district

court properly treated the two systems as one for the

31

purpose of developing a desegregation plan. Judge

Wisdom wrote in Lee, 448 F.2d at 752:

For purposes of relief, the district court treated

the Calhoun County and Oxford City systems as one.

We hold that the district court’s approach was fully

within its judicial discretion and was the proper way

to handle the problem raised by Oxford’s reinstitution

of a separate city school system. The City’s action

removing its schools from the county system took

place while the city schools, through the county board,

were under court order to establish a unitary school

system. The city cannot secede from the county where

the effect—to say nothing of the purpose—of the

secession has a substantial adverse effect on desegre

gation of the county school district. If this were

legally permissible, there could be incorporated towns

for every white neighborhood in every city. [Citations

omitted] . . . Even historically separate school dis

tricts, where shown to be created as a part of a state

wide dual school system or to have cooperated to

gether in the maintenance of such a system, have been

treated as one for purposes of desegregation. [Cita

tions omitted] . . .

School district lines within a state are matters of

political convenience. It is unnecessary to decide

whether long-established and racially untainted bound

aries may be disregarded in dismantling school segre

gation. New boundaries cannot be drawn where they

would result in less desegregation when formerly the

lack of a boundary was instrumental in promoting

segregation. Cf. Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal

Separate School District, 5 Cir. 1969, 409 F.2d 683,

688, n. 10.

32

We believe that Judge Wisdom’s formulation provides

a principle for decision consistent with the case law

developed in this Court from Brown to Swann and capable

of coping with a potentially widespread new pattern of

evasion, the “ incorporated town for every white neigh

borhood.” The courts below in this case wrote without

benefit of this Court’s opinion in Swann, but nevertheless

Judge Winter’s dissent (joined by Judge Sobeloff) reached

a formulation based on Green that is similarly satisfactory:

Given the application of the Green rationale, the

remaining task in each of these cases is to discern

whether the proposed subdivision will have negative

effects on the integration process in each area, and,

if so, whether its advocates have borne the “heavy

burden” of persuasion imposed by Green. (442 F.2d

at 589).

Judge Sobeloff’s dissenting opinion stated that the test

for any such secession was whether it served a “compelling

and overriding” state interest:

If challenged state action has a racially discriminatory

effect, it violates the equal protection clause unless

a compelling and overriding legitimate state interest

is demonstrated. This test is more easily applied,

more fully implements the prohibition of the Four

teenth Amendment and has already gained firm root

in the law. (442 F.2d at 595).

Of course Judges Sobeloff and Winter did not have the

benefit of Swann’s statement that in traditionally dual

systems there is a “presumption against schools that are

substantially disproportionate in their racial composition”

(402 U.S. at 26), and the holding that all proposals con

templating disproportionate schools should be scrutinized

“to satisfy the court that their racial composition is not

the result of present or past discriminatory action . .

(402 U.S. at 26).

Whatever verbal formulation is used to state the test,

we think the Fourth Circuit’s emphasis on the requirement

that plaintiffs show a legislative motivation to promote

segregation is basically inconsistent with effective imple

mentation of Brown in the face of determined tactics of

resistance and evasion. The response by all of the other

federal courts which have faced the secession tactic points

the way to full realization of the right to a racially non-

discriminatory public education.

II.

The Separation of Scotland Neck From the Halifax

County School System Impedes Desegregation of the

Schools Involved.

An analysis of the facts in this case demonstrates the

correctness of the district court’s ruling that the proposed

secession would impede desegregation and the error of

the court of appeals in labeling the change “hardly sub

stantial” and “minimal” . The application of the legal prin

ciples discussed in part I can best be understood by

considering the facts with respect to: (1) the pattern of

operation under the dual system, (2) the interim desegre

gation plan proposed by the state survey committee, and

(3) the pattern which would have developed with Scotland

Neck as a separate system, either with or without the

interdistrict transfers.

A. Organization of the Dual System in Scotland Neck Area.

The eastern part of Halifax County around the town of

Scotland Neck had a classic dual segregated system.

34

Scotland Neck School served all-white children for miles

around in grades 1-12.14 Five Black schools served the

same region in a separate system for blacks. Brawley

School (1-12)—less than a mile from Scotland Neck—

served the same region with a high school zone entirely

overlapping Scotland Neck’s and partially overlapping its

elementary zone (A. 273-276; 149). The other four black

schools (Bakers, Tillery Chapel, Dawson and Thomas

Shields) overlapped the balance of Scotland Neck’s ele

mentary attendance area. The black majority had “neigh

borhood” elementary schools while the white minority was

bused to a regional elementary school at Scotland Neck

(A. 273-276).

Under the dual system the boundary of the town of Scot

land Neck had no significance whatsoever in the assignment

of pupils. White pupils in the county came to town to at

tend Scotland Neck (A. 250), and black pupils living in

town went to Brawley which was located just outside the

city limits on the town’s eastern boundary (A. 273-276). In

1960 an addition to Scotland Neck School—the four-class

room junior high site—was built outside the town limits in

the county. Scotland Neck School was expanded period

ically15 to its present capacity of 1,000 students in order to

serve the white population of the eastern end of the county,

a larger population than the 695 resident pupils of the

town. Similarly the establishment of Brawley16 as a sep

arate school for blacks just a short distance away on the

14 The nearest white school was Enfield, about 16 miles from

Scotland Neck.

16 Scotland Neck was built in 1903, with classroom additions and

improvements in 1923, 1939, 1949, 1954 and 1960. (A. 667-A. 668)

16 Brawley was built in 1926 with classroom additions and im

provements in 1937, 1942, 1951, 1955, 1960 and 1968. (A. 652-

A .653)

35

town boundary (A. 233) was premised on using it to serve

all blacks in the region—both within and without the City

limits.

Under the dual system the Halifax County Board had a

variety of arrangements ignoring even the boundaries with

neighboring school administrative units where convenient

or necessary to serve the ends of segregation. For example,

Indian students were sent to the Haliwa School in the next

county, Warren County; many black students were sent to

Chaloner School in the Roanoke Rapids City system ; and

white pupils were sent to Littleton School in Warren County

(A. 221). Similar arrangements brought pupils from other

districts into the Halifax system to attend segregated

schools. The footnote below details this widespread pat

tern of ignoring and crossing over school unit boundaries

to implement segregation.17 When the arrangement sending

black children to Chaloner School located in the Roanoke

Rapids system was challenged by the Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare, the Halifax Board leased Chaloner

from Roanoke Rapids arid continued the black children in

17 (A. 221) ; Answer to interrogatory 3(d) (A. 859-860) :

A pproxim ate N um ber o f Students W ho Reside

W ithin the Unit hut W ho A tten d

School Outside o f the Unit

N o. o f Pupils School Unit School and School Unit

Y ear by Race o f Residence A tten d ed

1964-65 220 (Indian) Halifax County Haliwa-Warren County

160 (W hite) Halifax County Littleton-Warren County

800 (Negro) Halifax County Chaloner-Boanoke Bapids City

1965-66 220 (Indian) Halifax County Haliwa-Warren County

155 (W hite) Halifax County Littleton-Warren County

790 (Negro) Halifax County Chaloner-Boanoke Bapids City

1966-67 215 (Indian) Halifax County Haliwa-Warren County

155 (W hite) Halifax County Littleton-Warren County

1967-68 150 (Indian) Halifax County Haliwa-Warren County

150 (W hite) Halifax County Littleton-Warren County

1968-69 140 (Indian) Halifax County Haliwa-Warren County

150 (White) Halifax County Littleton-Warren County

1969-70 75 (W hite) Halifax County Littleton-Warren County

36

the same building which thus became a part of the Halifax

system even though it was located within the City of Roa

noke Rapids.18 In sum, the Halifax Board, like many other