Tyus v. Bosley, Jr. Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1993

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Tyus v. Bosley, Jr. Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1993. a65a281b-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ab733506-cb98-47e5-abb0-295112695472/tyus-v-bosley-jr-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

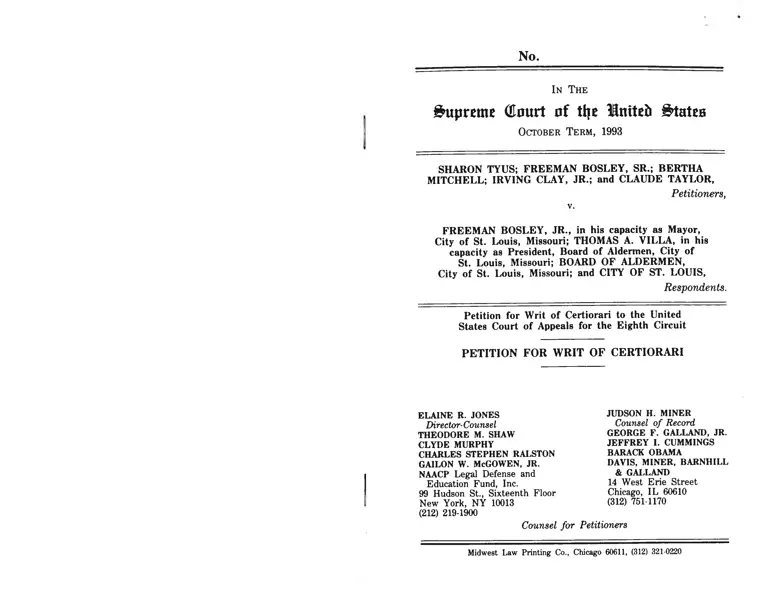

____________ No^________________________

In The

^prEine CCourt of tl|e ISniteii î tatea

October Term, 1993

SHARON TYUS; FREEMAN BOSLEY, SR.; BERTHA

MITCHELL; IRVING CLAY, JR.; and CLAUDE TAYLOR,

Petitioners,

V.

FREEMAN BOSLEY, JR., in his capacity as Mayor,

City of St. Louis, Missouri; THOMAS A. VILLA, in his

capacity as President, Board of Aldermen, City of

St. Louis, Missouri; BOARD OF ALDERMEN,

City of St. Louis, Missouri; and CITY OF ST. LOUIS,

Respondents.

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

ELAINE R. JONES

Director- Counsel

THEODORE M. SHAW

CLYDE MURPHY

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

GAILON W. McGOWEN, JR.

NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson St., Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

JUDSON H. MINER

Counsel of Record

GEORGE F. GALLAND, JR.

JEFFREY I. CUMMINGS

BARACK OBAMA

DAVIS, MINER, BARNHILL

& GALLAND

14 West Erie Street

Chicago, IL 60610

(312) 751-1170

Counsel for Petitioners

Midwest Law Printing Co., Chicago 60611, (312) 321-0220

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Is a single-member, multi-district reapportionment

plan immune from a challenge imder §2 of the Voting

Rights Act simply because the plan provides African ^ e r -

icans with a “proportional” number of districts in the juris

diction as a whole?

2. Does a minority group’s “proportional representation”

bar its §2 claim that district boundaries were purposefully

manipulated to dilute and minimize its voting strength, to

maximize the voting strength of the majority group, and to

“maintain[ ] the reelection chances of white incumbents?”

3. If a minority group’s “proportional representation”

does defeat its §2 challenge to a single-member, multi

district plan, is such representation measured by the minor

ity group’s share of the jurisdiction’s voting-age population

or by its share of the total population?

11

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS BELOW

The parties to the proceedings in the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit were petitioners

Sharon Tyus; Freeman Bosley, Sr.; Bertha Mitchell; Irving

Clay, Jr.; and Claude Taylor; and respondents Thomas A.

Villa, in his capacity as President, Board of Aldermen, City

of St. Louis, Missouri; Vincent C. Schoemehl, in his capacity

as Mayor, City of St. Louis, Missouri; Board of Aldermen,

City of St. Louis, Missouri; and City of St. Louis, Missouri.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR R EV IE W ........ i

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS BELOW........ ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................................... v

OPINIONS BELOW ................................................... vi

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION ....................... 1

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

AND STATUTES INVOLVED............................ 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .............................. 2

1. Statement of the F a c ts .................................... 2

2. The Proceedings Below.................................... 3

3. The Lower Courts’ Opinions........................... 6

a. The District C o u rt...................................... 6

b. The Proceedings In the Eighth Circuit . . . 7

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT:

I.

THE LOWER COURTS’ DECISION THAT “PRO

PORTIONAL REPRESENTATION” BARS A §2

CHALLENGE TO A SINGLE-MEMBER DISTRICT

PLAN CONFLICTS WITH THIS COURT’S DECI

SIONS IN GINGLES AND VOINOVICH AND PRE

SENTS AN UNSETTLED ISSUE OF GREAT PUB

LIC IMPORTANCE THAT REQUIRES CLARIFICA

TION BY THIS COURT............................................ 8

A. In Gingles, this Court articulated a clear ana

lytical framework for vote dilution claims in

the multi-member district context, while recog

nizing that a different analysis might apply to

single-member district p lans.......................... 10

IV

B. In Voinovich, this Court suggests an approach

for analyzing challenges to single-member dis

trict plans that conflicts with the lower courts’

opinion................................................................. 12

C. The lower courts’ approach conflicts with the

language and purpose of the Voting Rights Act

itse lf..................................................................... 21

II.

THE LOWER COURTS’ HOLDING THAT PROPOR

TIONAL REPRESENTATION BARS A §2 INTENT

CLAIM CONFLICTS WITH THE RULINGS OF

THIS COURT AND WITH OTHER CIRCUITS . . . 23

III.

IF PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION IS TO

SERVE AS A DEFENSE TO VOTING RIGHTS

CLAIMS, THE LOWER COURTS’ USE OF VOTING-

AGE POPULATION RATHER THAN TOTAL POPU

LATION AS THE MEASURE OF PROPORTIONAL

REPRESENTATION RAISES AN IMPORTANT IS

SUE ON WHICH LOWER COURTS HAVE TAKEN

DIVERGENT POSITIONS........................................ 26

A. This Court should provide direction to lower

courts who are in conflict regarding the proper

measure of proportional representation------ 26

B. The language of the Act and this Court’s

precedents indicate that total population is the

proper measure of proportion^ity............... 27

IV.

THIS CASE RAISES ISSUES SIMILAR TO THOSE

RAISED IN DEGRANDY v. JOHNSON MAKING

DEFERRAL APPROPRIATE.................................. 29

CONCLUSION............................................................. 30

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Coses Page

Allen V. State Board o f Education, 393 U.S. 544, 89

S.Ct. 2052, 22 L.Ed.2d 1 (1969)......................... 29

Assembly o f State o f California v. U.S. Dept, o f Com

merce, 968 F.2d 916 (9th Cir. 1992)................. 29

Baird v. Consolidated City o f Indianapolis, 976 F.2d

35 (7th Cir. 1992)................................................. 22,23

Barnett, et al. v. Daley, et al., 809 F.Supp. 1323

(N.D.Ill. 1992)......................................................... 26

Barnett, et al. v. Daley, et al., 835 F.Supp. 1063

(N.D.Ill. 1993)......................................................... 9, 25

Campbell v. Theodore, ___ U.S. ___ , 113 S.Ct.

2954, 125 L.Ed.2d 656 (1993).............................. 7,14

Chisom V. Roem er,___ U.S. ____ , 111 S.Ct. 2354,

115 L.Ed.2d 348 (1991)........................................ 29

City o f Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct. 1519,

64 L.Ed.2d 47 (1980)............................................ 23

City o f New York v. U.S. Dept, o f Commerce, 822

F.Supp. 906 (E.D.N.Y. 1993).............................. 29

City o f Port Arthur, Texas v. United States, 517

F.Supp. 987 (D.D.C. 1981) (three-judge court),

ojfd, 459 U.S. 159 (1982).................................... 24

City o f Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358, 95

S.Ct. 2296, 45 L.Ed.2d 245 (1975)..................... 23, 26

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 102 S.Ct. 2525, 73

L.Ed.2d 656 (1982)............................................... 22

DeGrandy v. Johnson, No. 92-519, appeal pending,

113 S.Ct. 1249 (1993)............................................ 26, 29

Fumco Const. Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567, 98 S.Ct.

2943, 57 L.Ed.2d 957 (1978)................................ 22

Garza v. County o f Los Angeles, 918 F.2d 763 (9th

Cir. 1990), cert, denied. 111 S.Ct. 681 (1991) .. 14, 25, 28

VI

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 81 S.Ct. 125,

5 L.Ed.2d n o (1960)............................................ 24

Gnrwe v. Em ison,___ U .S.____ , 113 S.Ct. 1075, 122

L.Ed.2d 388 (1993)............................................... 5, 7,14

Jeffers v. Clinton, 730 F.Supp. 196 (E.D. Ark. 1989),

affd, 498 U.S. 1019 (1991)......................... 9,14, 26, 27

Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398 (7th Cir. 1984), cert.

denied, 471 U.S. 1135 (1985)........................... 14, 23, 24

Kirkpatrick v. Preisler, 394 U.S. 526, 89 S.Ct. 1225

22 L.Ed.2d 519 (1969).......................................... 28

Kirksey v. Bd. o f Supervision, 554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.),

ceH. denied, 434 U.S. 968 (1977)....................... 14

Major V. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325 (E.D.La. 1983) . . . 23

McNeil V. Springfield Park, 851 F.2d 937 (7th Cir.

1988), ceH. denied, 490 U.S. 1031 (1989).......... 13, 27

Nash V. Blunt, 797 F.Supp. 1488 (W.D.Mo. 1992),

affd, 113 S.Ct. 1809 (1993)................................ 10, 26

Phillips V. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542, 91

S.Ct. 496, 27 L.Ed.2d 613 (1971)....................... 22

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 84 S.Ct. 1362, 12

L.Ed.2d 506 (1964)............................................... 28

Robinson v. Commissioners Court, 505 F.2d 674 (5th

Cir. 1974)................................................................. 15

Rodgers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 102 S.Ct. 3272, 73

L.Ed.2d 1012 (1982).............................................. 25

Rural West Tennessee African American Affair

Council V. McWherter, 836 F.Supp. 453 (W.D.

Tenn. 1993)..................... ...................................... 10, 26

Rybicki v. State Board of Elections, 574 F.Supp. 1082

(N.D. 111. 1982) (three-judge court)................... 25

Shaw V. Reno, ___ U.S. ___ , 113 S.Ct. 2816, 125

L.Ed.2d 511 (1993)........................................ 7, 23, 24, 26

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 92

L.Ed.2d 25 (1986)...................................................passim

Vll

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144,

69 S.Ct. 996, 51 L.Ed.2d 229 (1977)................. 28

Voinovich v. Quitter,___ U .S .____ , 113 S.Ct. 1149,

122 L.Ed.2d 500 (1993)...........................................passim

Wetherell v. DeGrandy, 794 F.Supp. 1076 (N.D.Fla.

1992), jurisdiction noted, sub nom. DeGrandy v.

Johnson,___ U.S_____ _ 113 S.Ct. 1249 (1993) .. 9

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes

United States Constitution, 14th and 15th Amend

ments ................................................................ 3, 9, 23, 25

28 U.S.C. §1254(1)...................................................... 1

42 U.S.C. §1973 ........................................................ passim

I n T he

Supreme Olourt 0f tlje Mnltth t̂atea

October Term, 1993

SHARON TYUS; FREEMAN BOSLEY, SR.; BERTHA

MITCHELL; IRVING CLAY, JR.; and CLAUDE TAYLOR,

Petitioners,

V.

FREEMAN BOSLEY, JR., in his capacity as Mayor,

City of St. Louis, Missouri; THOMAS A. VILLA, in his

capacity as President, Board of Aldermen, City of

St. Louis, Missouri; BOARD OF ALDERMEN,

City of St. Louis, Missouri; and CITY OF ST. LOUIS,

Respondents.

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Sharon Tyus, Freeman Bosley, Sr., Bertha Mitchell,

Irving Clay, Jr. and Claude Taylor respectfully petition for

a writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Cir

cuit together with the Court of Appeals’ order denying peti

tioners’ suggestion for rehearing en banc and the written

dissent to that order by Judge McMillian, are reported at

999 F.2d 1301 and appear in Appendix A (“App. A”) to this

petition. The opinions of the District Court for the Eastern

District of Missouri granting defendants’ Motion for Sum

mary Judgment and denying plaintiffs’ Rule 59(e) Motion

to Alter or Amend are unpublished and appear as Appendi

ces B and C, respectfully.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

August 4, 1993. Appellants were granted an extension to

August 31, 1993 to file for rehearing. On August 30, 1993,

appellants timely filed their petition for rehearing with sug

gestions for rehearing en banc. On November 1, 1993, one

judge dissenting, the Court of Appeals denied both petition

ers’ suggestions for rehearing en banc and their petition for

rehearing. On January 25, 1994 and again on February 8,

1994, this Court extended the filing date to March 1, 1994.

This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

CONSTI'TUTIONAL PROVISIONS

AND STATUTES INVOLVED

This case involves §2 of the Voting Rights Act, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. §1973. The relevant portion of the

statute appears at Appendix D.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

1. Statem ent of the Facts.

Petitioners are residents and voters in the City of St.

Louis. By its charter, the defendant St. Louis Board of

Aldermen was required in 1991 to redraw the aldermanic

boundaries in accordance with decennial census figures

(Art. I, §3). According to the 1990 census, St. Louis was

50.2% white, 47.4% African American, and 2.5% Hispanic

and other minorities.^ The city’s voting-age population was

55% white, 42.6% African American, and 2,4% Hispanic and

others (159-210). This population is strikingly segregated.

Over 90% of the white population in St. Louis is located on

the city’s south side and north along the Mississippi River

to the city’s northern end, while over 90% of the African

American population is concentrated on the city’s north

side, and west of the river front. A continuous boundary can

be drawn to encapsulate each community (73-83; 159-210;

211).

At the time the redistricting began, using the 1990 cen

sus data and the 1981 ward boundaries, the African Amer

ican population had grown to a majority status of 59.6% or

more in 13 of the city’s 28 wards and a plurality of 48.8%

in a 14th Ward. The white community had contracted to a

majority status of 58% or more in 13 wards and a plurality

of 49.8% in a 14th Ward (169-70). When the Board of Aider-

men began to redistrict the city, there were 17 white in

cumbent aldermen and 11 African American incumbent

According to the Census Bureau’s adjusted post-enumeration

figures, St. Louis is 48.9% white, 48.5% African American, and

2.5% Hispanic and other minorities (168). Citations are to the

pages of the record appendix filed with the Eighth Circuit.

aldermen, and there was a white mayor (63-7).*

During the redistricting process, the African American

aldermen proposed a plan that provided for 14 wards in

which African Americans could elect the candidates of their

choice and 14 wards in which whites could elect their pre

ferred candidates (89). The proposal was rejected by the

majority aldermen, who instead adopted a map th a t pro

vided for 16 wards in which whites have a voting-age

majority and can elect their candidate of choice, 11 wards

in which African Americans have a voting-age majority and

can elect their candidate of choice, and 1 ward (the 2nd) in

which African Americans have a 59.4% voting-age majority

but, eight months earlier, with similar population figures,

the African American community was unable to elect its

candidate of choice in a head-to-head bi-racial election (62-

7; 151-52; 169-70; 122).

2. 'The Proceedings Below.

In January, 1992, plaintiffs challenged St. Louis’ 1991

Ward map as a race-based redistricting whose ward boun

daries were manipulated with the purpose and effect of

diluting or minimizing the electoral potential of the city’s

African American population while maximizing the voting

strength of the white population, in violation of §2 of the

Voting Rights Act and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution (1-18).®

In February, 1993, while the appeal was pending, in a four

candidate primary, the white incumbent was defeated and an

African American won the democratic nomination for mayor. In

April, the African American democratic nominee won the general

election.

® In their complaint, plaintiffs alleged a one-person, one-vote

claim under the 14th Amendment together with a vote dilution

or racial gerrymander claim under §2 of the Voting Rights Act

and the 14th and 15th Amendments. The trial court rejected

(continued...)

Specifically, plaintiffs alleged that boundaries were

manipulated to fracture or “fragment[ ] a geographically

compact group of black voters” which would have supported

“one or more [additional] wards without such fragmenta

tion,” and to “reduc[e] the number of black persons residing

in [specific] wards” (12). According to plaintiffs’ complaint,

if the boundaries had been drawn “fairly and without dis

criminatory effect, blacks would constitute an effective

voting majority in at least 14 out of the 28 aldermanic

wards” (10). Instead, the 1991 Map provided African Ameri

cans with a voting-age majority in only 12 wards, and an

effective voting majority in only 11 wards.^ Plaintiffs also

alleged that defendants drew the map with “[t]he purpose

to deny or abridge the [voting] rights of blacks on account

of race or color” (10).

Defendants filed an answer® and then promptly moved

for summary judgment. The single ground for their motion

® (...continued)

plaintiffs’ one-person, one-vote claim and treated plaintiffs’ vote

dilution and/or racial gerrymander claims under §2 and not the

Constitution. On appeal, plaintiffs argued both their “results” and

their “intent” claims under §2 only. They did not appeal the one-

person, one-vote ruling.

* Plaintiffs further alleged that (a) the African American popu

lation was sufficiently large and geographically compact to sup

port 2 or 3 additional wards in which it could elect its preferred

candidates; (b) African Americans in St. Louis are politically co

hesive; and (c) the African-American population in St. Louis is

subject to racial bloc voting against candidates preferred by Afri

can Americans (9-11). Plaintiffs also alleged the presence of the

continuing burdens of past discrimination in voting rights, hous

ing and employment, all of which inhibit the ability of African

Americans to participate in the electoral process and to elect can

didates of their choice (9).

® In their answer, defendants admit that there is ample Mrican

American population for 14 wards (22); that voting in portions of

St. Louis is racially polarized (22-3); and that St. Louis has a long

history of private and public racial discrimination (22).

was tha t the 1991 map provides African Americans with

the possibility of obtaining proportional representation mea

sured by their percentage of voting-age population; tha t is,

African Americans, who comprise 47.4% of the city’s total

population but only 42.6% of its voting-age population, have

the possibility of electing their preferred candidates in 12

(42.8%) wards. In addition, defendants argued tha t St.

Louis ward maps have provided the c it/s African American

population with “proportional representation”, as measured

by voting-age population, for the past two decades (32).

In plaintiffs’ response, their expert disputed both the

manner in which defendants measured potential African

American voting strength under the new map, as well as

defendants’ assertion that proportional representation had

been previously achieved in St. Louis.® Plaintiffs argued

tha t because St. Louis is required to redistrict on the basis

of total population, total African American population and

not African American voting-age population must be used

® First, plaintiffs pointed out that defendants own chart showed

that St. Louis’ African American community has never attained

proportional representation on the cit3̂ s Board of Aldermen, even

under a voting-age population measure (62, 212). Second, plain

tiffs challenged the manner in which defendants’ expert arrived

at his conclusions, given that he performed no independent analy

sis of voting behavior in St. Louis, and relied solely on “the gen

erally accepted” rule of thumb that defines a “safe” ward at 65%

of total population or 60% of voting-age population and on figures

presented in an article which was not included in his affidavit

(32). Third, defendants’ expert counted the city’s 2nd Ward as an

African American ward in concluding that the 1991 map provides

for “proportional representation”, despite the fact that in 1991,

when the 2nd ward had a 58.4% African American voting-age

majority, the white incumbent defeated an African American rival

in a biracial election highlighted by low African American par

ticipation and severe racial bloc voting (62-7; 151-2; 169-70; 122).

Plaintiffs argued below that these facts demonstrated the need

for a thorough analysis of voting behavior within the Second

Ward before it can be characterized as an African American

ward. See Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075, 1085 (1993).

to determine whether African Americans have “proportional

representation” (90-1). Utilizing this traditional yardstick,

the 1991 map provided African Americans with a voting-age

majority in 42.8% of the wards or an “effective majority” in

only 39.2% of the wards, while African Americans’ percent

age of St. Louis’ total population is 47.4%, a ratio well short

of “proportional representation.”

Plaintiffs’ expert went on to detail the manner in which

the 1991 ward boundaries were selectively manipulated to

(a) reduce African American population in wards tha t had

become majority or plurality African American over the

past decade; (b) fracture African American population; and

(c) maximize white voting strength in the five wards within

St. Louis’ central corridor, thereby “maintaining the re-

election chances of white incumbents” (88-9). Plaintiffs

argued that such evidence of racial gerrymandering to mini

mize African American voting strength and to maximize

white voting strength should be sufficient to take the case

to trial, irrespective of the court’s findings regarding pro

portional representation.

3. 'The Low er C ourts’ O pinions.

a. The D is tric t C ourt. The district court granted

summary judgment to defendants. In doing so, the Court

made no reference to plaintiffs’ undisputed evidence that

the ward boundaries were manipulated to dilute or cancel

out minority voting strength and that, if the boundaries

had been drawn in a non-discriminatory manner, there

would be at least two more compact African American

wards and fewer white wards. Instead, the court focused ex

clusively on the issue of whether the map provided St.

Louis’ African American population with proportional re

presentation, citing Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30

(1986), for the proposition that once a minority group’s elec

toral success reaches “proportional representation [it] bars

a section 2 claim” (App. B-8).

The court also concluded that “proportional representa

tion” should be measured by the minority group’s percent

age of the voting-age population, and not by the group’s

percentage in the total population (App. B-9). In addition,

the court accepted defendants’ assertion that the 1991 map

provides African Americans with 12 wards—proportional re

presentation when measured against African Americans’

voting-age population—and that St. Louis’ aldermanic maps

had provided African Americans with such “proportional re

presentation” for the past two decades (App. B-8). Rejecting

plaintiffs’ claim that, in the single-member, multi-district

context, boundary manipulation should at the very least

constitute a special circumstance that can demonstrate that

this sustained proportional representation “does not accu

rately reflect the minority’s ability to elect its preferred re

presentatives,” the court concluded that “the sustained elec

toral success of African American candidates [in St. Louis]

defeats plaintiffs’ claim” (App. B-9).

b. The P roceed ings In the E ig h th C ircu it. On

November 30,1992, petitioners appealed the district court’s

ruling. The briefing was completed on March 17, 1993, and

the appeal was argued on May 12, 1993. On August 4,

1993, the panel issued an order finding “no error of law or

clearly erroneous findings of fact in the district court’s well-

reasoned memorandum,” and affirming the judgment of the

district court’ (App. A-3).

’’ Between March 2, 1993 and June 28, 1993, while the appeal

was pending, this Court issued three opinions and an order in

which it began to articulate the appropriate framework for analy

zing voting rights challenges to single-member, multi-district

plans like that in St. Louis. Growe v. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075

(1993); Voinovich v. Quitter, 113 S.Ct. 1149 (1993); Shaw v. Reno,

113 S.Ct. 2819 (1993); and Campbell v. Theodore, 113 S.Ct. 2954

(1993). On July 15, 1993, petitioners moved for a supplemental

briefing schedule to address this new Supreme Court authority

(continued...)

8

On August 31, 1993, petitioners filed a suggestion for a

rehearing en banc. The petition was denied on November 1,

1993, without opinion. Judge McMillian filed a written dis

sent, criticizing the court’s handling of the case:

This case raises important legal and factual issues

under the Voting Rights Act. In my view, genuine issues

of material fact exist making this case wholly unsuited

for summary judgment. The district court gave no con

sideration to, and made no findings concerning, serious

allegations and evidence of a violation of §2 of the Voting

Rights Act. In particular, I believe the district court

should have made detailed findings regarding whether

the City of St. Louis intentionally created its aldermanic

districts to dilute African American voting strength in

violation of Section 2.

(App. A-3-4).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

THE LOWER COURTS’ DECISION THAT “PROPORTION

AL REPRESENTATION” BARS A §2 CHALLENGE TO A

SINGLE-MEMBER DISTRICT PLAN CONFLICTS WITH

THIS COURT’S DECISIONS IN GINGLES AND VOINO-

VICH AND PRESENTS AN UNSETTLED ISSUE OF GREAT

PUBLIC IMPORTANCE THAT REQUIRES CLARIFICA

TION BY THIS COURT.

This case presents an issue of fundamental importance

to the continued vitality of the Voting Rights Act. The lower

court held that where a redistricting plan provides a minor

ity group with the potential for sustained proportional re

presentation, the requirements of the Voting Rights Act are

’ (...continued)

which directly conflicts with the analytic framework adopted by

the district court. The panel denied petitioners’ motion as moot

(App. A-1).

satisfied, irrespective of undisputed evidence that the sin

gle-member district boundaries have been blatantly manip

ulated to advantage white over African American voters.

The lower court based its conclusion on its interpretation of

this Court’s opinion in Thornburg v. Gingles, supra, which,

according to the lower court, makes proportional represen

tation an absolute bar to any §2 claim.

The lower court’s holding fundamentally misreads this

Court’s voting rights jurisprudence, and sets a dangerous

precedent for the adjudication of §2 challenges to single

member district plans. In Voinovich v. Quilter, supra, this

Court observed that the manipulation of ward boundaries

is the standard device by which to minimize or cancel out

minority voting strength in single-member district plans.

Such racial gerrymandering to prefer one race of voters over

another can occur even where the gerrymander provides

minority voters with rough “proportional representation” as

measured by voting-age population.

Despite Voinovich, lower courts continue to struggle with

this issue of how to reconcile challenges to single-member

district plans with the emphasis on proportional representa

tion contained in the closing section of the majority opinion

in Gingles. This confusion has resulted in a number of in

consistent rulings. For example, in Weatherall v. DeGrandy,

794 F.Supp. 1076 (N.D.Fla. 1992) (three-judge court), ju r

isdiction noted, sub nom. DeGrandy v. Johnson, 113 S.Ct.

1249 (1993), the court did not apply a proportional repre

sentation analysis to a challenged single-member district

plan. See also Jeffers v. Clinton, 730 F.Supp. 196 (E.D. Ark.

1989), affd , 498 U.S. 1019 (1991). On the other hand, a

trial judge in Barnett v. Daley, 835 F.Supp. 1063, 1066

(N.D. 111. 1993) relied upon the present action together with

this Court’s opinion in Gingles for its conclusion that, as a

m atter of law, proportional representation bars a voting

rights claim under §2 and under the 14th or 15th Amend-

10

ments. See also Nash v. Blunt, 797 F.Supp. 1488 (W.D. Mo.

1992) (three-judge court), affd , 113 S.Ct. 1809 (1992) (court

applied Gingles' proportional representation analysis to a

single-member district plan.)

In a slightly different context, the three-judge court in

Rural West Tennessee African American Affair Council v.

McWherter, 836 F.Supp. 453 (W.D. Tenn. 1993) applied a

traditional “totality of the circumstances” analysis to the

1991 Tennessee legislative map and found that it discrimi

nated against African Americans by packing them into two

districts in Shelby County, Tennessee and by fracturing

them among four districts in a neighboring rural part of the

state. The court concluded that an additional African

American district could have been drawn in each area. The

court ruled, nevertheless, that a remedy of one more district

was sufficient in as much as it would provide African

Americans with proportional representation as measured by

their percentage of the voting-age population. In other

words, the court held that despite a finding of actual dilu

tion two areas, proportional representation analysis per

mitted vote dilution in one of these areas to go unremedied.

This case presents the Court with the opportunity to

clarify the appropriate anal)dical framework for evaluating

the increasing number of challenges to single-member dis

trict plans.

A. In Gingles, this Court articulated a clear analytical

framework for vote dilution claims in the multi-member

district context, while recognizing that a different

analysis might apply to single-member district plans.

In Gingles, this Court stated that the essence of a §2

claim is that based on the “totality of the circumstances,”

a certain electoral law, practice or structure interacts

with social and historical conditions to cause inequality

in the opportunities enjoyed by black and white voters to

elect their preferred representatives.

11

478 U.S. a t 47 (Emphasis added); Voinovich, 113 S.Ct. at

1155 (single-member district plan). In Gingles, and subse

quently in Voinovich, this Court identified three precondi

tions to any vote dilution “effects” claim: (a) a sufficiently

large and geographically-compact minority community that

can support additional single-member districts; (b) a politi

cally cohesive minority community; and (c) racial bloc vot

ing. Gingles, 478 U.S. a t 50-51; Voinovich, 113 S.Ct. a t

1157. Once plaintiffs have satisfied this threshold showing,

as petitioners have done here, they must provide evidence

of those additional factors that tend to show that the chal

lenged electoral practice causes an inequality in the oppor

tunity of African American and white voters to elect their

preferred candidates. According to this Court, these factors,

which are listed in the Senate Report accompanying the

Amendment to §2, are supportive, but not essential to, a

minority voter’s claim. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 45. Moreover,

failure “to establish any particular factor is not rebuttal evi

dence of non-dilution.” S.Rep. at 29 n. 118.

In Gingles, this Court held that in the multi-member

and /or at-large district context, “the extent to which minor

ity group members have been elected to public office in the

jurisdiction” is the single most important additional factor

for courts to consider once the three preconditions are met.

More precisely, a majority of the Court concluded that a

minority’s proportional electoral success in a specific multi

member district could defeat a minority’s §2 claim if it was

sustained over a number of elections. According to a ma

jority of the Court, such sustained proportional represen

tation is “inconsistent” with a claim of vote dilution in the

multi-member context. Id. at 76-77.

This Court refused to say that even sustained electoral

success was an absolute bar to vote dilution challenges to

multi-member districts, and reserved for decision those

“special circumstances [that] could satisfactorily demon-

12

strate that sustained success does not accurately reflect the

minority group’s ability to elect its preferred representa

tives.” Id. a t 77, n. 38. Moreover, this Court was careful to

state that the framework set out in Gingles might not apply

to the analysis of challenges to single-member, multi-dis

trict plans. Id. a t 45, n. 12; 48, n. 15; and 49, n. 16. As Jus

tice O’Connor noted in her concurrence, in a single-member

district context, “the way in which district lines are drawn

can have a powerful effect on the likelihood that members

of a geographically and politically cohesive minority group

will be able to elect candidates of their choice.” Gingles, 478

U.S. at 87 (O’Connor, J. concurring).

Given the critical differences in the manner in which

vote dilution may be accomplished in various redistricting

plans, the language of Gingles clearly cautions against the

mechanical application of a proportional representation

analysis to this case. 'The lower court failed to heed this

warning, thereby summarily disposing of a well-documented

claim of vote dilution under §2 and refusing to conduct the

totality of the circumstances analysis demanded by §2.

B. In Voinovich, this Court suggests an approach for analy

zing challenges to single-member district plans that

conflicts with the lower courts’ opinion.

The lower court’s assumption that the Gingles analysis

of the importance of proportional representation applies

with equal force in the single-member district context is

wrong. In the at-large or multi-member district context,

proportional representation is generally both the most use

ful proxy for a minority group’s undiluted voting strength

and the best indicator that the minority group has an equal

opportunity to elect its preferred representatives. Under

multi-member district or at-large plans, all voters are

thrown into a single electoral stew; racial gerrymandering

is not at issue. Instead, the danger posed by such plans is

that “[i]f voting is racially polarized, a white majority is

13

able to consistently elect its candidates of choice, submerg

ing the preferences of minority voters.” McNeil v. Spring-

field Park, 851 F.2d 937, 938 n. 1 (7th Cir. 1988), cert,

denied, 490 U.S. 1031 (1989). If, in this situation, minorities

are consistently able to elect representatives in proportion

to their numbers, it is difficult, if not impossible, to identify

any sense in which the multi-member district plan causes

dilution of their voting strength.®

'Things are very different in the single-member, multi

district context. Only last term, in Voinovich, this Court

recognized tha t in the single-member district context, “the

usual device for diluting minority voting power is the

manipulation of district lines,” and that in single-member

districts (113 S.Ct. at 1155):

dilution of racial minority group voting strength may be

caused either by dispersal of blacks into districts in

which they constitute an ineffective minority of voters

[fracturing] or from the concentration of blacks into

districts where they constitute an excessive majority

[packing].

In other words, “boundary manipulation” is the most rele

vant factor in evaluating whether a single-member, multi

district plan dilutes minority voting strength or causes an

inequality in the opportunities enjoyed by African American

® A minority group’s sustained proportional representation with

in the multi-member or at-large context will generally indicate

that a substantial portion of the majority group “crosses over” to

support minority candidates, a phenomenon that is “inconsistent”

with a finding that racial bloc voting submerges minority voting

strength to deprive them of equal opportunity to elect candidates

of their choice. Proportional representation will be an even more

accurate indicator of equal opportunity in multi-member jurisdic

tions that contain only two racial groups (as was the case in the

North Carolina districts analyzed in Gingles), since proportional

representation for one group necessarily indicates proportional

representation for the other group as well.

14

and white voters to elect their preferred representative. Id.

at 1155.®

Voinovich’s emphasis on “fracturing” and “packing” in a

single-member district case is not new. Lower courts have

long recognized that the fracturing of a minority community

coupled with racial bloc voting tends to dilute minority

voting strength in violation of §2. Jeffers v. Clinton, 730

F.Supp. a t 205; see also Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398,

1405 (7th Cir. 1984), cert, denied 471 U.S. 1135 (1985);

Garza v. County o f Los Angeles, 918 F.2d 763, 771 (9th Cir.

1990), cert, denied. 111 S.Ct. 681 (1991); Kirksey v. Bd. of

® More recently, in Campbell v. Theodore, 113 S.Ct. 2954 (1993)

this Court suggests the need for a detailed, fact intensive analysis

to determine whether a specific, single-member, multi-district

scheme provides a minority group with vmequal access to the

political process. In Campbell, this Court vacated and remanded

“for further consideration in light of the position presented by the

Acting Solicitor General in his brief of May 7, 1993.” In his brief,

the Acting Solicitor General presented two positions. First, in the

single-member context, the lower court must address “the ques

tion whether additional compact and contiguous districts with

black majorities could and should have been created in disputed

areas to avoid dilution of black voting strength in violation of §2.”

The brief made no mention of “proportional representation” as a

cap on the inquiry (Brief at 7). Second, the district court’s iden

tification of African American or white districts requires an in-

depth analysis of each district that begins with voting-age popu

lation and includes a district-specific analysis of the “extent to

which voting is polarized” and “particularized consideration of

historical voting patterns, election results, or other data to sup

port treating identified districts as black ‘opportunity districts’ in

the face of plaintiffs’ challenges [that less than 57% African-

American voting-age population did not provide African-Ameri-

can-opportunity wards]” (Brief at 14 and 15, n. 11). Accord Growe

V. Emison, 113 S.Ct. 1075, 1085 (1993).

In this case, the lower court made no effort to determine

whether the St. Louis ward boundaries diluted African American

voting strength nor did it address the question of whether addi

tional compact or contiguous districts with African American

mtgorities could or should be drawn. The undisputed record below

resolves both inquiries in the affirmative.

15

Supervision, 554 F.2d 139, 149 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 434

U.S. 968 (1977); Robinson v. Commissioners Court, 505 F.2d

674, 679 (5th Cir. 1974).

For purposes of this case, the importance of the

Voinovich approach lies in the fact tha t such manipulation

of ward boundaries to “fracture” and “pack” minority popu

lations can be used to dilute minority voting strength

throughout a jurisdiction, while a t the same time providing

for minority electoral success in a “proportional” number of

districts. This can occur in three ways. First, the co-exis-

tence of proportional representation and minority vote dilu

tion is almost assured when the African American and

white population are segregated and voting-age population

is used to measure proportionality. Assume the following:

(a) a city of 1,200,000 in which African Americans com

prise 20% of the total population and 12% of the

voting-age population and whites comprise 80% of

the total population and 88% of the voting age popu

lation;

(b) one-half of the African Americans live in a geographi

cally compact but segregated community at the

northern end of the city and the other half live in a

geographically compact but segregated community at

the southern end; both communities are politically

cohesive and there is a history of racial bloc voting;

and

(c) the city has 8 single member districts. The 120,000

African Americans who live on the north side reside

in one district while the 120,000 African Americans

who live on the south side are fractured evenly

among four districts so tha t each district is 75%

white and 25% African American.

This hypothetical map has provided “proportional repre

sentation” for African Americans based on their percentage

of the voting-age population (12% of the voting-age popula

tion and 12% of the districts) within the city as a whole.

16

while denying equal opportunity to African Americans by

flagrantly diluting the voting strength of the south side

African American population.

Second, proportional representation and signiflcant vote

dilution can occur under a single-member district plan

whenever more than two racial groups reside within the

jurisdiction. In such circumstances, district boundaries can

be gerrymandered in order to insure that whites benefit

from “surplus” minority populations that are insufficient to

form their own districts.*®

Third, any single-member district map can selectively

“fracture” and “pack” minority voters in particular districts

in which racial bloc voting occurs, even as minority candi

dates in other districts within the jurisdiction succeed due

to the absence of racial bloc voting.**

Assume, for example, a city of 2,000,000 that is 40% white,

40% African American, 10% Hispanic and 10% Asian and that is

divided into 20 single member districts; all four groups are politi

cally cohesive and there is a history of racial bloc voting; the

housing patterns are such that both the whites and the African

Americans live in a single, segregated community while the His-

panics and Asians live in a number of small, dispersed commu

nities; and finally, none of the Hispanic or Asian communities are

large enough to create a district of their own, but can be included

in either white or African American majority districts. In this

hypothetical, ward boundaries can be manipulated to fracture or

pack African Americans and to use other minority populations to

help create additional white wards rather than additional African

American wards. In our hypothetical, a map could be drawn that

packs African Americans into 8 wards (40%), their “proportional”

number of wards, while whites can be given 12 wards, a number

far in excess of their “proportional” number.

“ For example, assume a jurisdiction with 8 single-member dis

tricts in which the African American population totals 20% of a

jurisdiction’s total population, that half of this African American

population lives in an integrated north side where racial bloc

voting is not present, and half live in a geographically concen

trated area on the south side with virulent racial bloc voting. For

(continued...)

17

What all these examples show is that, in the single

member, multi-district context, there is no necessary con

nection between a particular group’s percentage in the city’s

population and the number of wards where they would be

“expected” to have voting control in the absence of mani

pulative designing of boundaries. Conversely, if a particular

group ends up with a “proportional” number of wards, that

fact sheds little or no light on whether there has or has not

been manipulation of ward boundaries to enhance or to

dilute that group’s strength. 'That conclusion can only be

drawn from a searching examination of “the totality of the

circumstances,” including the geographic distributions and

density of white, African American and other groups; the

impact of the particular boundaries on white, African Amer

ican and other groups; the process by which they were

drawn; the constraints on possible alternative boundaries

(for example, geographic features like rivers, railroad

tracks, vacant industrial land, etc.); and all the other fac

tors set forth in the Senate subcommittee report to the Vot

ing Rights Act.

In this case, petitioner presented evidence of those facts

that, according to Voinovich, should be of singular concern

in a §2 challenge to a single-member, multi-district plan—

namely that in drawing the boundaries of the 1991 map,

defendants reduced African American population in specific

wards to enhance white voting strength, and systematically

“fractured” African American voters to cancel out their vot

ing strength while maximizing the voting strength of the

" (...continued)

such a scenario, African Americans might be elected in two north

side districts, thereby providing African Americans with propor

tional representation as a whole, even while south side African

Americans are flagrantly fractured and packed to prevent them

from exercising an equal opportunity to elect representatives of

their choice.

18

white population. In support of their allegations, plaintiffs’

expert focused on five of St. Louis’ 28 wards which comprise

the central corridor and on the one ward that runs along

the North Riverfront portion of St. Louis—the only geo

graphical areas in St. Louis in which concentrations of

African American and white population live in close enough

proximity to each other to permit the drawing of wards that

could be either white or African American (88-9).^ ̂At the

time of redistricting, the incumbents in all six of these dis

tricts were white.

According to plaintiffs’ expert, defendants used three

techniques in order to preserve white incumbencies. First,

the boundaries of the five central corridor wards were re

drawn to reduce African American voting strength and in

crease white voting strength.'® Next, ward boundaries were

In the context of a multiple-district plan, the vote dilution

analysis must be district specific. See Gingles, supra.

The table below outlines the results of the 1991 Remap:

1980 Afr-Am Whites 1990

Ward Map % White % Afr-Am Moved Out Moved In Map % Afr-Am

6 14,100 37.1 59.6 663 1,357 14,746 52.4

7 13,298 49.9 46.6 500 1,330 14,278 39.9

8 14,661 58.0 37.3 809 (1,336) 14,052 44.6

17 15,680 46.1 48.8 1,980 790 14,279 39.7

28 17,522 64.4 31.9 776 (2,625) 14,071 34.1

To see the significance of these manipulations, consider the

6th ward. Under the 1981 ward map, according to the 1990 cen

sus, the 6th ward was 59.6% African American and it was 67 per

sons short of the ideal ward population of 14,167. The ward did

not have to be redrawn at all. Instead, defendants manipulated

the ward boundaries to remove 663 African Americans and moved

in 1,357 whites. Thus, a 59.6% African American majority became

a 52.4% majority (which translates to a 46% voting-age minority).

Had defendants reversed the flow, the 59.6% African American

majority would have been elevated to over 66% (6,163, 169, 159-

167; 171-74,121). Thus, African American voting strength was re

duced from 13 voting-age majority wards and 1 plurality ward to

12 voting age majority wards.

19

manipulated to “fracture” politically-cohesive, homogenous,

African American populations, but not white populations.'^

Finally, defendants drew the boundaries of the 2nd Ward

to maximize white voting strength.'®

Such systematic manipulation of ward boundaries to ad

vantage one racial group over another is precisely what the

Voting Rights Act is designed to prevent. Under the analy

tical framework suggested in Voinovich, a court would have

necessarily considered these facts in making its “totality of

the circumstances” analysis. Under the lower court’s ap

proach, on the other hand, such blatant manipulation of

ward boundaries can be safely ignored. Neither the Act, nor

Gingles, nor Voinovich, countenance such an approach.

Because there is no necessary correlation between pro

portional representation and the existence, or lack there

of, of vote dilution in the single-member district context,

this Court must clarify the applicability of the Gingles

‘‘ Within the five central corridor wards reside 71,426 persons,

of whom 30,476 (42.2%) are African American. This area could

have been redistricted to include two effective African American

wards, and three effective white wards. Instead, the 1991 Map

distributed the 30,476 African Americans in ineffective groupings

among five white wards in percentages of 52.6 (but 45.9% of

voting-age population), 40.2, 45.0, 40.1, and 34.3 of the total

population of each ward respectively (5, 163, 164-7).

'® At the time of redistricting, the old 2nd Ward was 64.3% Afri

can American (58.4% voting-age population) and was bordered on

the east and north by the river and on its west by five wards that

were 93.0%, 95.8%, 98%, 98.8% and 98.9% African American. De

fendants could easily have drawn a compact ward with an effec

tive African American voting-age majority. Instead, the 2nd ward

was drawn in 1991 to run from the central corridor to the far nor

thern boundary of the city in order to pick up as much white

population as possible (39.5% of the voting age population) to pre

serve the reelection prospects of the white incumbent (163-4; 169-

70; 171-74; 120-1).

20

framework to §2 challenges to single-member district

plans.*®

If the analytic framework set forth in Gingles is to apply to

single-member district claims, then the lower courts need guid

ance as to the factors that constitute “special circumstances” that

override the sustained proportional representation defense. Writ

ing for the majority in Gingles, Justice Brennan and Justice

White concluded that a minority group’s proportional electoral

success will usually be dispositive if it is sustained over a number

of elections, and if plaintiffs fail to demonstrate '‘special circum

stances that such sustained success does not accurately reflect the

minority group’s ability to elect its preferred representatives.” 478

U.S. at 77, n.38. This Court in Gingles specifically reserves the

question of what such a category of “special circumstances” might

include. Ibid.

The lower courts that have attempted to analyze single-mem

ber plans within the Gingles framework are at odds over the ap

plication of the “special circumstances” language. For example, in

the instant case, the lower court seems to have accepted defen

dants’ argument that “special circumstances” are limited to

factors such as “bullet voting” because they were the only factors

suggested by this Court in Gingles, 478 U.S. at 57, n.25. How

ever, the “special circumstances” identified in Gingles while illus

trative in the multi-member district context, have no relevance in

the single-member district context. In Barnett, the court held that

the “special circumstances” can only be those circumstances

which indicate that proportional representation is “attributable

to transient factors” . . . 835 F.Supp. at 1069, n.8. See also Nash,

797 F.Supp. at 1499-1505. 'This analysis overlooks the fact the

“special circumstances” discussed in Gingles come into play only

a& r it has been found that sustained proportional representation

exists.

Given this court’s emphasis in Voinovich on the importance of

manipulation of ward boundaries in the single-member district

plan, a showing that district boundaries have been manipulated

to dilute a minority group’s voting strength and to advantage

another racial group must, at the very least, constitute a “special

circumstance” that overrides a showing of proportional electoral

success. Only through such an approach can this Court’s holding

in Gingles be reconciled with the language in Voinovich and the

mandate set forth by Congress in its amendments to the Voting

Rights Act. Guidance by this Court is needed.

21

C. The lower courts’ approach conflicts with the language

and purpose of the Voting Rights Act itself.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act states that “[t]he ex

tent to which members of a protected class have been

elected to office in the . . . political subdivision is one factor

which may be considered” in the evaluation of vote dilution

claims (emphasis added). ’This directive appears as part of

the proviso which establishes that the members of the pro

tected class have no per se right to proportional repre

sentation under §2.

By treating minority electoral success as the only factor

to consider, the lower courts’ opinion effectively turns the

language of section 2 on its head. Under the lower courts’

approach, proportional representation effectively becomes

a per se cap on a minority group’s electoral rights, leaving

officials free to gerrymander district boundaries to maxi

mize the voting strength of the jurisdiction’s majority

voters.

Ironically, such an approach encourages precisely the

kind of focus on proportional representation that the Voting

Rights Act itself disavows. The Act makes clear that

nothing in it is intended to guarantee proportional repre

sentation to any group. Nor is the Act intended to guaran

tee maximizing any particular group’s voting strength.

What the Act is intended to guarantee—in each and every

area of the city—is protection against unequal treatm ent in

the political process on the basis of race.

The absolute defense of proportional representation

recognized by the lower court moves the law away from this

fundamental protection of the Act and the searching

“totality of the circumstances” analysis this Court demands,

and into the kind of overall numbers game that the Act

itself and its critics condemn, whereby justice turns a blind

eye to practices that systematically discriminate against

minority voters, so long as white officials “give” them

22

roughly proportional representation. Such a balanced-

bottom-line approach to analyzing voting rights claims has

been soundly rejected by this Court in other contexts,

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 448-54 (1982); Furnco

Const. Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567,579-80 (1978); Phillips

V. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542, 543-44 (1971); and

has been rejected by the Seventh Circuit in the voting

rights context. Baird v. Consolidated City o f Indianapolis,

976 F.2d 357, 359 (7th Cir. 1992).

In this case, the demographics of St. Louis permits the

drawing of ward maps that could produce from 17 white

and 11 African American aldermen to 11 white and 17 Afri

can American aldermen. The St. Louis map caps African

American representation at 11 aldermen while preserving

the ability of the similarly geographically compact white

community to elect 17 aldermen. No one has disputed, at

any point in this litigation, that if the map had been drawn

without any consideration of racial demographics or if

African Americans and whites were fractured and otherwise

treated evenhandedly, there would be more wards in which

African Americans would have the opportunity to elect their

candidate of choice.

Such systematic and unequal treatment must not go un

remedied. Without clear direction from this Court, the “pro

portional representation defense” recognized by the lower

court will mean exactly that. A writ of certiorari should be

issued so tha t this Court can guide the lower courts in the

proper analytical framework for the growing number of §2

challenges to single-member, multi-district plans.

23

II.

THE LOWER COURTS’ HOLDING THAT PROPORTIONAL

REPRESENTATION BARS A §2 INTENT CLAIM CON

FLICTS WITH THE RULINGS OF THIS COURT AND WITH

OTHER CIRCUITS.

To the extent tha t a redistricting plan is “conceived or

operated as [a] purposeful device to further racial discrimi

nation” it is actionable under §2 as well as the Fourteenth

Amendment. City o f Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 66-67

(1980); see, e.g., Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d a t 1406; Major

V. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325, 350 (E.D. La. 1983) (three-judge

court) (Intentional discrimination in the redistricting proc

ess that violates the 14th Amendment is also actionable un

der §2). This Court has long recognized that a law th a t in

tentionally disadvantages a minority group to secure advan

tage for whites is presumptively unlawful:

An official action, whether an annexation or otherwise,

taken for the purpose of discriminating against Negroes

on account of their race has no legitimacy at all under

our constitution or under [the Voting Rights Act].

City o f Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358, 378

(1975). Because discrimination has no legitimacy under law,

this Court has held that the defense of proportional repre

sentation cannot foreclose a claim of intentional discrimina

tion. See City o f Richmond, 422 U.S. at 372-79 (holding, in

a case under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, tha t the in

tent to discriminate through a municipal annexation is

actionable even though the post-annexation districting plan

provided African Americans with proportional representa

tion); see also Baird, 976 F.2d at 360 (Proof of intentional

discrimination overcomes the defense of proportional re

presentation in §2 claim).

Indeed, this Court recently held in Shaw v. Reno, 113

S.Ct. 2816 (1993), that white plaintiffs could pursue a cause

of action under the Fourteenth Amendment by alleging that

24

intentional discrimination existed where a majority African

American district was so irregular in shape that it could

only be explained as an attempt at pure racial gerryman

dering. The significance of Shaw to this petition is that the

white plaintiffs were permitted to press their intentional

racial gerrymandering claim even though they enjoyed sub

stantially more than proportional representation.*^

In this case, the lines of the 1991 map may not be so

bizarre as to qualify under the standard set forth in Shaw.

However, plaintiffs in this case are not relying solely on the

facial irregularity of the map. Plaintiffs go well beyond the

allegations offered by the Shaw plaintiffs, and point to an

array of facts that demonstrate that the boundaries were

systematically manipulated to maximize white voting

strength, preserve white incumbencies, and reduce African

American voting strength. These facts are the classic

indicia of an intentional racial gerrymander. See Gomillion

V. Lightfoot, 346 U.S. 339 (I960).'* In addition, plaintiffs

u ^haw objected in part on the ground that

white North Carolinians enjoyed representation in excess of their

numbers in the population, and that the white plaintiffs in that

case had alleged no discriminatory effect.

Nevertheless, Justice White, who had previously joined Justice

Brennan in Gingles with respect to the importance of proportional

representation in the multi-member district context, acknowl

edged the possibility that the mere fact that a racial group enjoys

proportional representation does not foreclose the possibility of

mscriminatory effect, since in the single-member district context

such districting might have both the intent and effect of

packing’ members of that group so as to deprive them of any in

fluence in other districts.” 113 S.Ct. at 2835, n. 6 (White J dis

senting).

o Arthur, Texas v. United States, 517

U.S. 159 (1982) (reduction of African American voting strength

****«̂er Voting RigMs

Act), Ketchum, 740 F.2d at 1408 (discrimination based on an ulti-

(continued...)

25

offered evidence of racial bloc voting; depressed socioeco

nomic status attributable to a history of discrimination in

education, housing and employment; and a history of dis

crimination in electoral matters. These factors also support

a finding of intentional discrimination. Rodgers v. Lodge,

458 U.S. 613, 622-27 (1982).

It would be a perversion of justice to rule tha t white

plaintiffs in North Carolina may challenge a map under the

14th Amendment that was drawn by the State in order to

remedy perceived inequities between African American and

white voters, solely because the map is inartfully drawn,

while a t the same time barring a §2 intent claim that pro

vides detailed evidence of systematic boundary manipu

lation and “fracturing” to purposely diminish African Amer

ican voting strength. Yet this is precisely the interpretation

Shaw and Gingles have received in the lower courts. In this

case, the lower courts refused to even consider plaintiffs’

allegations because of a finding of proportional representa

tion. Likewise, in Barnett, the court held that once propor

tional representation is established, plaintiffs can no longer

assert an intent to dilute claim. According to the Barnett

court, the only intent claims available to plaintiffs are chal

lenges (a) to practices that “actually bar minorities from

voting . . . or interfere with their right to register,” or (b) to

a reapportionment scheme “so extremely irregular on its

face that it can be viewed as an effort to segregate the

races.” 835 F.Supp. at 1068-70.

The lower court’s summary disposition of plaintiffs’ in

tentional discrimination claim by finding that African

(...continued)

mate objective of keeping certain incumbent whites in office is in

distinguishable from discrimination borne of pure racial animus);

Rybicki v. State Board of Elections, 574 F.Supp. 1082, 1108-09,’

(N.D. 111. 1982) (three-judge court); Garza v. City of Los Angeles’

918 F.2d at 771.

26

Americans were provided with the opportunity to achieve

proportional representation under the challenged plan

squarely conflicts with this Court’s pronouncements in

Richmond and Shaw. A writ of certiorari should issue to

clarify the relationship between proportional representation

and claims of intentional vote dilution.

III.

IF PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION IS TO SERVE AS

A DEFENSE TO VOTING RIGHTS CLAIMS, THE LOWER

COURTS’ USE OF VOTING-AGE POPULATION RATHER

THAN TOTAL POPULATION AS THE MEASURE OF PRO

PORTIONAL REPRESENTATION RAISES AN IMPOR

TANT ISSUE ON WHICH LOWER COURTS HAVE TAKEN

DIVERGENT POSITIONS.

A. This Court should provide direction to lower courts

who are in conflict regarding the proper measure of

proportional representation.

Lower courts that have attempted to apply the Gingles’

proportional representation analysis to single-member dis

trict plans cannot agree on how it is to be measured. In the

instant case as well as in Rural West Tennessee, supra, the

courts used voting-age population as the appropriate mea

sure. In Nash, 797 F.Supp. a t 1498-1502; Jeffers, 730

F.Supp. at 198; and Barnett v. Daley, 809 F.Supp. 1323,

1329 (N.D. 111. 1992), the courts relied upon Gingles and

used total population as the proper measure of proportional

representation. In the DeGrandy case currently pending be

fore this court, appellants argue that this court should use

citizenship population as the proper measure. If lower

courts are to use proportional representation as an impor

tant factor in analyzing vote dilution claims in the single

member, multi-district context, a writ of certiorari should

be issued to resolve this conflict.

27

B. The language of the Act and this Court’s precedents in

dicate that total population is the proper measure of

proportionality.

The lower courts’ use of voting-age population to mea

sure proportional representation directly conflicts with the

language of §2 and decisions of this Court which hold tha t

where proportional representation is relevant, total popula

tion is the proper measure.*®

The starting point is the Act itself. Section 2 defines a

violation in terms of a showing that the electoral scheme

provides minority citizens with less opportunity “than other

members of the electorate” to participate in the political

process and to elect candidates of their choice. It then dis

avows a minority’s right to proportional representation in

the following language: “Nothing in this section establishes

a right to have members of a protected class elected in

numbers equal to their proportion in the population” (Em

phasis added). Clearly, §2 defines proportional represen

tation by “population”, not “voting-age population” or “the

electorate.”

Additionally, when Congress amended §2 in 1982, it ex

pressly noted that: “The principle that the right to vote is

The lower court’s use of voting-age stems simply from its ob

servation that “voting age is an appropriate measure for voting

rights cases.” (App. B-9) Voting-age population is in fact one of

the important factors in determining whether a minority’s total

population within a specific district is sufficient to provide it with

a reasonable opportunity to elect its preferred candidates. See,

e.g., McNeil, supra; Jeffers v. Clinton, 730 F.Supp. at 199. But it

has no relevance to a proportional representation analysis. Pro

portional representation is relevant only to the extent that it is

a surrogate for a group’s undiluted voting strength. Since total

population is used to reapportion single-member districts, how

ever, a minority’s total population figures are the only population

figures that determine the number of effective minority wards

that can be drawn and thereby measure the group’s undiluted

voting strength.

28

denied or abridged by dilution of voting strength derives

from the one person, one vote reapportionment case of Rey

nolds V. Sim s.” S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 19 re

ported in 1982 U.S. Code Cong, and Admin. News 177,196.

In Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 535,560-61 (1964), this Court

stated “[t]he fundamental principal of representative

government is one of equal representation for equal num

bers of people . . . .” This “one-person, one-vote” principle

is based on total population. In Kirkpatrick v. Preisler, 394

U.S. 526, 531 (1969), the Court recognized that “equal re

presentation for equal numbers of people is a principle de

signed to prevent debasement of voting power and diminu

tion of access to elected officials.” Reapportionment on the

basis of total population guarantees equal representation

and equal access to our elected officials.

In Gingles, this Court applied this principle of “propor

tional representation” to the Voting Rights Act and used

total population, not voting-age population, as its measure.

According to the Court in Gingles, the test for establishing

sustained electoral success of the minority community in a

multi-member district was whether “black residents” had

proportional representation. 478 U.S. at 74-77 (emphasis

added); 478 U.S. a t 74, n. 35; see also United Jewish Or

ganizations V. Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 166 (1977) (a claim un

der §5 of the Act). The Court then observed that in North

Carolina’s 23rd district, “the last six elections have resulted

in proportional representation for black residents.” Gingles,

478 U.S. at 77 (emphasis added). It determined proportional

representation by measuring the minority group’s percent

age of the total population (36.3%) with its electoral success

rate (one of three electoral representatives). Gingles, 478

U.S. at 74, n. 35, and 478 U.S. a t 104 (O’Connor, J., concur

ring); see Garza v. County o f Los Angeles, 918 F.2d a t 776

(the use of voting-age population rather than total popula

tion discriminates against minorities by diluting “the access

of voting-age [minorities]. . . to their representatives, and

29

would similarly abridge the right o f . . . minors to petition

their representatives”). As long as the wards are appor

tioned on the basis of total population, proportional repre

sentation must be measured by the same population base.

In the end, there is only one reason for using voting-age

population as the measure of proportional representation:

it permits the white majority to provide the minority com

munity with the fewest number of districts while still im

munizing their handiwork from a §2 challenge.^ This result

conflicts with the repeated admonition of this Court th a t §2

of the Act “should be interpreted in a manner tha t provides

‘the broadest possible scope in combatting racial discrimina

tion.” Chisom V. Roemer, 111 S.Ct. 2354, 2368 (1991),

quoting Allen v. State Board o f Education, 393 U.S. 544,

567 (1969).

IV.

THIS CASE RAISES ISSUES SIMILAR TO THOSE RAISED

IN DEGRANDY v. JOHNSON MAKING DEFERRAL AP

PROPRIATE.

On February 22, 1993, this Court noted probable juris

diction in the Florida state legislative redistricting case. De-

Grandy v. Johnson, No. 92-519, 113 S.Ct. 1249 (1993). The

issues in DeGrandy, as here, are whether (a) proportional

representation is a defense to a §2 challenge to a single

member, multi-district plan; and if so, (b) what weight is it

to be given within a “totality of the circumstances” analysis;

(c) is proportional representation to be determined on a ju r

isdiction-wide basis or on a more localized basis, (i.e..

“ The fundamental unfairness in using voting-age population to

further reduce minority representation is compoimded by the fact

that there is clear and convincing evidence that African American

population was seriously under-coimted in the last census. See

City of New York v. U.S. Dept, of Commerce, 822 F.Supp. 906, 913

(E.D.N.Y. 1993); Assembly of State of California v. U.S. Dept, of

Commerce, 968 F.2d 916, 917 (9th Cir. 1992).

30

should the court look at the City of St. Louis as a whole or

focus on the central corridor area where the boundaries

were manipulated to dilute minority voting strengths); and

(d) is it to be measured by total population or some other

population figure. These issues will have a significant bear

ing on the proper resolution of all single-member district

claims including the St. Louis reapportionment. For these

reasons, deferral is appropriate.

CONCLUSION

For all the reasons stated above, a writ of certiorari

should be issued to review the judgment and opinion of the

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. APPENDICES

Respectfully submitted,

JUDSON H. MINER

Counsel of Record

GEORGE F. GALLAND, JR.

JEFFREY I. CUMMINGS

BARACK OBAMA

DAVIS, MINER, BARNHILL

& GALLAND

14 West Erie Street

Chicago, IL 60610

(312) 751-1170

ELAINE R. JONES

Director- Counsel

THEODORE M. SHAW

CLYDE MURPHY

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

GAILON W. McGOWEN, JR.

NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson St., Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Petitioners

INDEX TO APPENDICES

P age

Opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Cir

cuit and Court of Appeals’ Order Denying Peti

tioners’ Suggestion for Rehearing en b a n c ........ A-1

Opinion of the District Court Granting Defendants’

Motion for Summary Judgment ............................ B-1

Opinion of the District Court Denying Plaintiffs’

Rule 59(e) Motion to Alter or A m end................ C-1

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as Amended,

42 U.S.C. §1973 .......................................................... D-1

A-1

APPENDIX A

AFRICAN AMERICAN VOTING RIGHTS LEGAL DE

FENSE FUND, INC.; Charles Q. Troupe; Angela D.

Walton, Plaintiffs,

Freeman Bosley, Jr.; Bertha Mitchell; Appellants,

Ida Ford; Charles Parker; Albert Banks; Carol Page;

Luretta Hawkins; Elmer Otey; Jacqueline McGill,

Plaintiffs,

Sharon Tyus, Appellant,

Laima Gordon; Alexis Johnson, Plaintiffs,

Irving Clay; Claude Taylor, Appellants,

V.

Thomas A. VILLA, in his capacity as President, Board

of Aldermen, City of St. Louis, Missouri; Vincent C.

Schoemehl, in his capacity as Mayor, City of St. Louis,

Missouri; Board of Aldermen, City of St. Louis, Missouri;

City of St. Louis, Appellees.

American Civil Liberties Union, Amicus Cimiae.

No. 92-3826.

United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit.

Submitted May 12, 1993.

Decided Aug. 4, 1993.

Order Denying Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc

Nov. 1, 1993.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Missouri; Hon. Jean C. Hamilton, Dis

trict Judge.

Judson Miner, Chicago, IL, argued for appellants.

Donna A. Smith, St. Louis, MO, on brief for amicus

curiae American Civ. Liberties Union.

A-2

Julian Bush, St. Louis, MO, argued (James J. Wilson,

Edward J. Hanlon and Michael Garvin, on brief), for ap

pellees.

Before BOWMAN, Circuit Judge, HENLEY, Senior Cir

cuit Judge, and MAGILL, Circuit Judge.