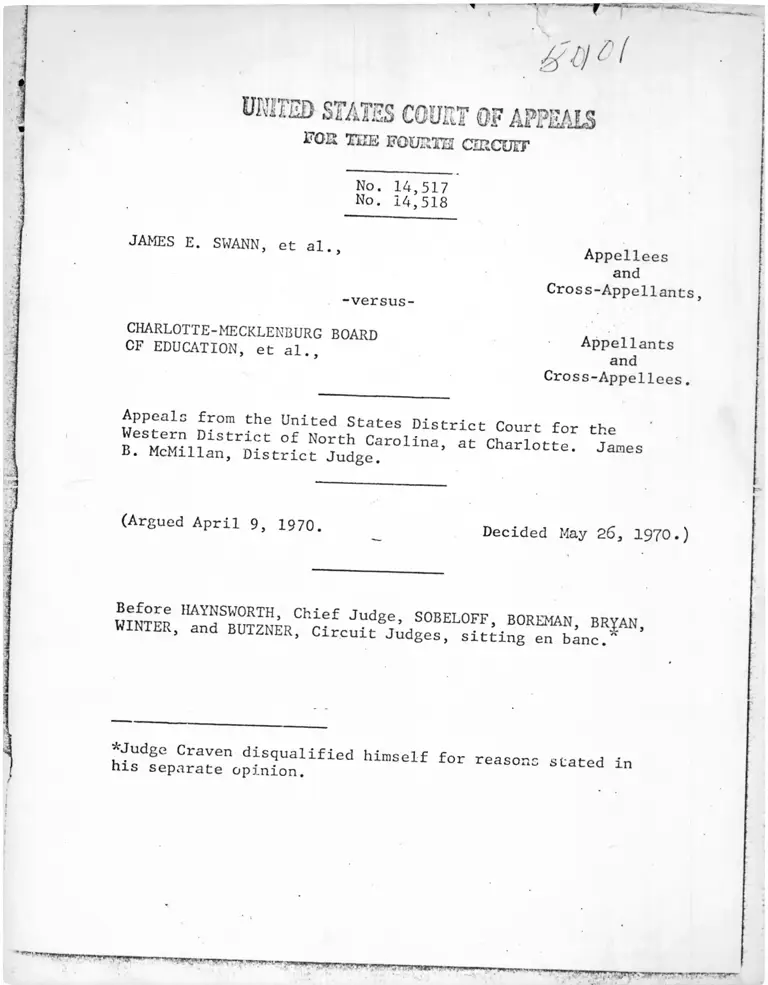

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Opinion

Public Court Documents

April 9, 1970 - May 26, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Opinion, 1970. 897db578-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ab7ad1fc-6fa1-4c14-a32d-e89a0f265328/swann-v-charlotte-mecklenberg-board-of-education-opinion. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

'/Jlj D I

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

HIE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 14,517

No. 14,518

JAMES E. SWANN, et al.,

-versus-

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD CF EDUCATION, et al.,

Appellees

and

Cross-Appellants,

Appellants

and

Cross-Appellees.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

(Argued April 9, 1970. Decided May 26, 1970.)

hisdfeDir^r dis?ualified himself for reasons stated in nxs separate op3.mon.

-iA’ ,

William J. Waggoner and Benjamin S. Horack (Ervin, Horack

and McCartha; and Weinstein, Waggoner, Sturges, Odom and

Bigger 01 brief) for appellants and cross-appellees; J.

LeVonne Chambers (Adam Stein and Chambers, Stein, Ferguson

& Lanning; Jack Greenberg, James M. Nabrit, III, and Con

rad 0. Pearson on brief) for appellees and cross-appellants;

David L. Norman, Deputy Assistant Attorney General of the

United States, (Jerris Leonard, Assistant Attorney General,

Brian K. Landsberg and David D. Gregory, Attorneys, Depart

ment of Justice, and Keith S. Snyder, United States Attorney

for the Western District of North Carolina, on brief) for

United States of America as amicus curiae; Stephen J. Poliak

(Richard M. Sharp, and Shea & Gardner; and David Rubin, on

brief) for The National Education Association as amicus

curiae; The Honorable William C. Cramer, M.C.,amicus curiae;

Gerald Mager for The Honorable Claude R. Kirk, Jr., Governor

of Florida, amicus curiae.

- 2 -

. L»| - -

‘:i

i

/tIf

ifr

i

i

I*

BUTZNER, Circuit Judge:

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg School District ap

pealed from an order of the district court requiring the

faculty and student body of every school in the system to

be racially mixed. We approve the provisions of the order

dealing with the faculties of all schools and the assign

ment of pupils to high schools and junior high schools,

but we vacate the order and remand the case for further

consideration of the assignment of pupils attending ele

mentary schools. We recognize, of course, that a change

in the elementary schools may require some modification

of the junior and senior high school plans, and our remand

is not intended to preclude this.

I.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system serves

a population of over 600,000 people in a combined city and

county area of 550 square miles. With 84,500 pupils attend-

1. The board's plan provides: "The faculties of all school;

will be assigned so that the ratio of black teachers to

white teachers in each school will be approximately the same

as the ratio of black teachers to white teachers in the en

tire school system." We have directed other school boards

to desegregate their faculties in this manner. See Nesbit

v. Statesville City Bd. of Ed., 418 F.2d 1040, 1042 (4th

Cir. 1969) ; cf. , United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of

• Ed., 395 U.S. 225, 232 (1969).

N -3-

ing 106 schools, it ranks as the nation's 43rd largest

school district. In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd.

of Ed., 369 F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966), we approved a de

segregation plan based on geographic zoning with a free

transfer provision. However, this plan did not eliminate

the dual system of schools. The district court found that

during the 1969-70 school year, some 16,000 black pupils,

out of a total of 24,700, were attending 25 predominantly

black schools, that faculties had not been integrated, and

that other administrative practices, including a free trans

fer plan, tended to perpetuate segregation.

Notwithstanding our 1965 approval of the school

board's plan, the district court properly held that the

board was impermissibly operating a dual system of schools

in the light of subsequent decisions of the Supreme Court,

Green v. School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 435

(1968), Monroe v. Bd. of Comm'rs, 391 U.S. 450 (1968), and

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Ed., 396 U.S. 19 (1969).

The district judge also found that residential

patterns leading to segregation in the schools resulted in

part from federal, state, and local governmental action.

These findings are supported by the evidence and we accept

N

-4-

them under familiar principles of appellate review. The

district judge pointed out that black residences are con

centrated in the northwest quadrant of Charlotte as a

result of both public and private action. North Carolina

courts, in common with many courts elsewhere, enforced

racial restrictive covenants on real property^ until

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948} prohibited this dis

criminatory practice. Presently the city zoning ordinances

differentiate between black and white residential areas.

Zones for black areas permit dense occupancy, while most

white areas are zoned ro c hr n 4- n rl 1 nrv/J ̂--- mk « J r /- ̂ ̂ -- - '— ^ ~ uou6c, m e uiS-

trict judge also found that urban renewal projects, sup

ported by heavy federal financing and the active partici

pation of local government, contributed to the city's raciall

segregated housing patterns. The school board, for its part,

located schools in black residential areas and fixed the

size of the schools to accommodate the needs of immediate

neighborhoods. Predominantly black schools were the in

evitable result. The interplay of these policies on both

residential and educational segregation previously has been 2

2. E.g., Phillips v. Wearn, 226 N.C. 290, 37 S.E.2d 895 (1946

-5-

recognized by ibis and other courts.3 The fact that similar

forces operate in cities throughout the nation under the

mask of de facto segregation provides no Justification for

ailowing us to ignore the part that government plays rn

creating segregated neighborhood schools.

The disparity in the number of black and white

pupils the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board busses to

predominantly black and white schools illustrates how

• t-v. location of schoolscoupling residential patterns wrth the

i u ic All pupils are eligible tocreates segregated schools. All pup

. _ .. ... 1 .̂.C farther than 1-1/2 miles ride school buses rr cne, — c -----

from the schools to which they are assigned. Overall sta

tistic. show that about one-half of the pupils entitled

to transportation ride school buses. Only 541 pupils were

bussed in October 1969 to predominantly black schools.

3. E.g.. Henry v. Clarksdale U.S. 940

e V SC o o l ^ t r g r o ^ c o o k County.

404 F.2d 1125, 1130 Oth C ' v _ gStoSl Bd. of City

786, 798 (N.D. HI. 1988'> ,, rir 1968); Keyes v.

of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37, Supp. 279 and 289 (D.

School Dist. No. One, ^ f h s n t e d F.2d_____ <1°«*

Colo.), stay PendHl£-aEEi--gg-^^1969) ; Dowell v. School Cir.), stay_vaca£|^, 396 U.S^ 12 5 t g?5 (W-D. Okla. 1965),

Bd. of Oklahoma City, 244 F-Supp. denled, 387 U.S. 931

af f' d, 375 F.2d 158 , ^ [ C™ '1 l.fr& h S S S S in th^Public

H967t. See generally Fiss, — j g ^ ^ T X T T e v . 564

fsisai* °£ 419 F-2(1965). But see Deal v.

1387 (6th Cir. 1969).

-6-

‘ >\lW |

which had a total enrollment of over 17,000. In contrast,

8 schools located outside the black residential area have

in the aggregate only 96 students living within 1-1/2 miles.

These schools have a total enrollment of about 12,184 pupils

of whom 5,349 ride school buses.

II.

The school board on its own initiative, or at

the direction of the district court, undertook or proposed

a number of reforms in an effort to create a unitary school

system. It closed 7 schools and reassigned the pupils pri

marily to increase racial mixing. It drastically gerry

mandered school zones to promote desegregation, n created

a Single athletic league without distinction between white

and black schools or athletes, and at its urging, black and

white PTA councils were merged into a single organization.

It eliminated a school bus system that operated on a racial

basis, and established nondiscriminatory practices in other

facets of the school system. It modified its free transfer

plan to prevent resegregation, and it provided for integra

tion of the faculty and administrative staff.

-7-

The (Uhi t int'‘inn h i rim/ f ttf

,,r i.i,, , W'instaking analysis°r the liom-.l1,! ,, ,

... . ' authorities, dis-•ippiovcd u„.. board',, llwil t

school,, nearly |(|>|()/ ' becaUSe " left

the distrle, ' 1,1 "K thls decision>

BLrUl C,,,‘r<- I'-M II,a, ,, „qf-,. 1 . , ’> "ml inutit integrate thestudent bo,ly of every

school,,, which I..... lnm 3 dUal SyStem

a , " hy state action, toa unitary ayutem.

“llio noeeaajfy

exi (.r, , 1 v/̂ h segregation thatexisLs because govern,,,,.,,,

neii-hh k * 111 segregatedneighborhood school,, j,, .

„cckl , " <0 the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School !,J (lt,a ,

in many other ,■•• • ’ segregation occurs

tion-il , , n »' nation, and constitutional principle,, d<,„||„., w(

ally Thr S '"',Id be applied nation-

aiAy- rhe 8°1u lJon Ja nor

now well ^ ,l<)"> ‘‘l^iculty. It iswell settled that school ,

hnvo n cn °l,,,r/,ling dual systemshave an affirmative „

system t i l l (o n unptary school

system in Which racial ,||fierl„,

1 "''lion would be eliminatedroot and branch." rril,

391u 0 V' of New Kent County,

391 u* S* 4 °̂> W <\%H) ,o

i < 111 * I*" Supreme Court defined a unitary school ,Val„

J *ih ht) (aHi | i.i i • -iWiLhin which no perso

is to be effectively excluded from any school because of

race or color." Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Ed.,

396 U.S. 19, 20 (1969). This definition, as the Chief

Justice noted in Northcross v. Board of Ed. of Memphis,

90 S.Ct. 891, 893 (1970), leaves open practical problems,

"including whether, as a constitutional matter, any par

ticular racial balance must be achieved in the schools;

to what extent school districts and zones may or must be

altered as a constitutional matter; to what extent trans

portation may or must be provided to achieve the ends

sought by prior holdings of the Court."

Several of these issues arise in this case. To

resolve them, we hold: first, that not every school in a

unitary school system need be integrated; second, neverthe

less, school boards must use all reasonable means to inte

grate the schools in their jurisdiction; and third, if

black residential areas are so large that not all schools

can be integrated by using reasonable means, school boards

must take further steps to assure that pupils are not ex

cluded from integrated schools on the basis of race. Special

classes, functions, and programs on an integrated basis

-9-

T'jrw maH. .» ......... A y .„ , v... .”'■"/mi. '*™ "1-vim. •»>. .4.

should be made available to pupils in the black schools.

The board should freely allow rrajority to minority trans

fers and provide transportation by bus or common carrier

so individual students can leave the black schools. And

pupils who are assigned to black schools for a portion of

their school careers should be assigned to integrated schools

as they progress from one school to another.

We adopted the test of reasonableness -- instead

of 006 that calls for absolutes — because it has proved

to be a reliable guide in other areas of the law. Further-

raorej the standard of reason provides a test for unitary

school systems that can be used in both rural and metropoli

tan districts. All schools in towns, small cities, and

rural areas generally can be integrated by pairing, zoning,

clustering, or consolidatirg schools and transporting pupils.

Some cities, in contrast, have black ghettos so large that

integration of every school is an improbable, if not an un

attainable, goal. Nevertheless, if a school board makes

every reasonable effort to integrate tUe pupils under its

control, an intractable remnant of segregation, we believe,

should not void an otherwise exemplary plan for the c\-eation

-10-

of a unitary school system. Ellis v. Board of Public

Instruc. of Orange County, No. 29124, Feb. 17, 1970

will be. assigned to the system's ten high schools accord

ing to geographic zones. A typical zone is generally fan

shaped and extends from the center of the city to the

suburban and rural areas of the county. In this manner

the board was able to integrate nine of the high schools

with a percentage of black students ranging from 17% to

367o. The projected black attendance at the tenth school,

The court approved the board's high school plan

with one modification. It required that an additional

300 pupils should be transported from the black residential

area of the city to Independence School.

The school board proposed to rezone the 21 junior

high school areas so that black attendance would range from

0% to 907o with only one school in excess of 38%. This schoo

F. 2d (5th Cir.)

Ill

The school board's plan proposes that pupils

Independence, which has

-11-

Piedmont, in the heart of the black residential area, has

an enrollment of 840 pupils, 90% of whom are black. The

district court disapproved the board's plan because it

maintained Piedmont as a predominantly black school. The

court gave the board four options to desegregate all the

junior high schools: (1) rezoning; (2) two-way transporta

tion of pupils between Piedmont and white schools, (3)

closing Piedmont and reassigning its pupils and (4) adopt

ing a plan proposed by Dr. John A. Finger, Jr., a consult

ant appointed by the court, which combined zoning with

satellite districts. The board, expressing a preference

for its own plan, reluctantly adopted the plan proposed

; . :

by the court's consultant.

Approximately 31,000 white and 13,000 black pupils

are enrolled in 76 elementary schools. The board's plan

for desegregating these schools is based entirely upon geo

graphic zoning. Its proposal left more than half the black

elementary pupils in nine schools that remained 86% to 100%

black, and assigned about half of the white elementary pupils

to schools that are 86% to 100% white. In place of the

-12-

board's plan, the court approved a plan based on zoning,

pairing, and grouping, devised by Dr. Finger, that re

sulted in st.ident bodies that ranged from 9% to 38% black

The court estimated that the overall plan which

it approved would require this additional transportation:

No. of

pupils

No. of

buses

Operating

cost

Senior High 1,500 20 $ 30,000

Junior High 2,500 28 § 50,000

Elementary 9,300 90 $186,000

TOTAL 13,300 138 $266,000

In addition, the court found that a new bus cost about

$5,400, making a total outlay for equipment of $745,200.

The total expenditure for the first year would be about

$1 , 011, 200.

The school board computed the additional trans

portation requirements under the court approved plan to

be:

-13-

No. of

PuPils-

No. of

buses

Operating

cost

Senior Hie.h 2,497 69 $ 96,000

Junior High 4,359 84 $116,800

Elementary 12,429 269 $374,000

TOTAL 19,285 422 $586,800

In addition to the annual operating cost, the school board

projected the following expenditures:

Cost of buses

Cost of parking areas

Cost of additional personnel

$2,369,100

284,800

166,200

Based on these figures, the school board computed the total

expenditures for the first year would be $3,406,700 under

4

the court approved plan.

4. The school board computed transportation requirements

under the plan it submitted to be:

No. of No. of Operating

pupils buses cost

Senior High 1,202 30 $ 41,700

Junior High 1,388 33 $ 45,900

Elementary

TOTAL

2,345 41 $ 57,000

4,935 104 $144,600

(cont.) -14-

Both the findings of the district court and the

evidence submitted by the board are based on estimates

that rest on many variables. Past practice has shown that

a large percentage of students eligible for bus transporta

tion prefer to provide their own transportation. However,

it is difficult to accurately predict how many eligible

students will accept transportation on the new routes

and schedules. The number of students that a bus can

carry each day depends in part on the number of trips the

bus can make. Scheduling two trips for a bus generally

reduces costs. But student drivers may not be able to

spend the time required for two trips, so that adult driver

will have to be hired at substantially higher salaries. It

is difficult to accurately forecast how traffic delays will

affect the time needed for each trip, for large numbers

4. (cont. from p. 14):

The board estimated that the breakdown of costs for the

first year of operation under its plan would be:

Cost of buses .

Cost of parking areas

Operating expenses of $144,600

Plus depreciation allow

ance of . 31? 000

Cost of additional personnel

$589,900

56,200

175,600

43,000

The estimated total first-year costs are $864,700.

-15-

of school buses themselves generate traffic problems that

only experience can measure.

The board based its projections on each 54-

passenger bus carrying about 40 high school pupils or 54

junior high and elementary pupils for one roundtrip a day.

Using this formula, it arrived at a need of 422 additional

buses for transporting 19,285 additional pupils. This ap

pears to be a less efficient operation than the present

system which transports 23,600 pupils with 280 buses, but

the board's witnesses suggest that prospects of heavier

traffic justify the difference. The board also envisioned

parking that seems to be more elaborate chan chctu currenuly

used at some schools.

In making its findings, the district court applied

factors derived from present bus operation, such as the

annual operating cost per student, the average number of

trips each bus makes, the capacity of the buses -- includ

ing permissible overloads, and the percentage of eligible

pupils who use other forms of transportation. The district

court also found no need for expensive parking facilities

or for additional personnel whose costs could not be ab

sorbed by the amount allocated for operating expenses. While

- 16 -

TF*rw" — r s rm " *1 r - ’ - n r * r

we recognize that no estimate --whether submitted by the

board or made by the court -- can be_absolutely correct,

we accept as not clearly erroneous the findings of the dis

trict court.

Opposition to the assignment of pupils under

both the board's plan and the plan the court approved cen

tered on bussing, which numbers among its critics both

black and white parents. This criticism, however, cannot

justify the maintenance of a dual system of schools. Cooper

v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958). Bussing is neither new nor un

usual. It has been used for years to transport pupils to

consolidated schools in both racially dual and unitary

school systems. Figures compiled by the National Educa

tion Association show that nationally the number of pupils

bussed increased from 12 million in the 1958-59 school

year to 17 million a decade later. In North Carolina

54.97o of all pupils are bussed. There the average daily

roundtrip is 24 miles, and the annual cost is over

$14,000,000. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg School District

presently busses about 23,600 pupils and another 5,000

ride common carriers.

Bussing is a permissible tool for achieving

integration, but it is not a panacea. In determining

who should be bussed and where they should be bussed,

a school board should take into consideration the age of

the pupils, the distance and time required for transporta

tion, the effect on traffic, and the cost in relation to

the board's resources. The board should view bussing for

integration in the light that it views bussing for other

legitimate improvements, such as school consolidation and

the location of new schools. In short, the board should

draw on its experience with bussing in general -- the

benefits and the defects -- so that it may intelligently

plan the part that bussing will play in a unitary school

system.

Viewing the plan the district court approved for

junior and senior high schools against these principles

and the background of national, state, and local transporta

tion policies, we conclude that it provides a reasonable

way of eliminating all segregation in these schools. The

estimated increase in the number of junior and senior high

school students who must be bussed is about 17% of all

-18-

pupils now being bussed. The additional pupils are in

the upper grades and for the most part they will be going

to schools already served by busses from other sections

of the district. Moreover, the routes they must travel

do not vary appreciably in length from the average route

of the system's buses. The transportation of 300 high

school students from the black residential area to sub

urban Independence School will tend to stabilize the

system by eliminating an almost totally white school in

a zone to which other whites might move with consequent

5"tipping" or resegregation of other schools.

5. These 300 students will be bussed a straight-lane dis

tance of some 10 miles. The actual bus routes will be

somewhat longer, depending upon the route chosen. A rea

sonable estimate of the bus route distance is 12 to 13

miles. The principal's monthly bus reports for Independ

ence High School for the month from January 10, 1970 to

February 10, 1970 shows the average one-way length of a

bus route at Independence is presently 16.7 miles for the

first trip. Buses that make two trips usually have a

shorter second trip. The average one-way bus route, in

cluding both first and second trips, is 11.7 miles. Thus

the distance the 300 pupils will have to be bussed is nearly

the same as the average one-way bus route of the students

presently attending Independence, and it is substantially

shorter than the system's average one-way bus trip of 17

miles.

- _19-

,' W, TTT-7

We find no merit in other criticism of the plan

for j inior and senior high schools. The use of satellite

school zones^ as a means of achieving desegregation is not

improper. District Courts have been directed to shape

remedies that are characterized by the "practical flexi

bility" that is a hallmark of equity. See Brown v. Board

of Ed., 349 U.S. 294, 300 (1955). Similarly, the pairing

and clustering of schools has been approved. Green v.

County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 442

n .6 (1968); Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 F.2d

801, 809 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969).

The school board also asserts that §§ 401(b) and

407(a)(2) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 [42 U.S.C. §§

2000c(b) and -6(a)(2)] forbid the bussing ordered by the

district court.^ But this argument misreads the legislative

6. Satellite school zones are non-contiguous geographical

zones. Typically, areas in the black core of the city are

coupled -- but not geographically linked -- with an area

in white suburbia.

7. Title 42 U.S.C. § 2000c(b) provides that as used in the

subchapter on Public Education of the Civil Rights Act of

1964:

'"Desegregation1 means the assignment of

students to public schools and within such schools

without regard to their race, color, religion, or

national origin, but 'desegregation' shall not mean

the assignment of students to public schools in

order to overcome racial imbalance."

(cont.)

-20-

history of the statute. Those provisions are not limita

tions on the power of school boards or courts to remedy

unconstitutional segregation. They were designed to re

move any ir. plication that the Civil Rights Act conferred

new jurisdiction on courts to deal with the question of

whether school boards were obligated to overcome cle facto

segregation. See generally, United States v. School Dis

trict 151, 404 F.2d 1125, 1130 (7th Cir. 1968); United

States v. Jefferson County Board of Ed., 372 F.2d 836, 880

(5th Cir. 1966), aff'd on rehearing en banc 380 F.2d 385

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, sub nom. Caddo Parish School Bd.

v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967); Keyes v. School

Dist. No. One, Denver, 303 F.Supp. 289, 298 (D. Colo.),

sta~y pending appeal granted, ____ F.2d ____ (10th Cir.); 7

7. (cont. from p. 20)

Title 42 § 2000c-6(a)(2) states in part:

"[Provided that nothing herein shall empower

any official or court of the United States to

issue any order seeking to achieve a racial

balance in any school by requiring the trans

portation of pupils or students from one school

to another or one school district to another in

order to achieve such racial balance, or other

wise enlarge the existing power of the court to

insure compliance with constitutional standards."

- 21 -

stay vacated, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969), Uor docs North Caro

lina's anti-bussing law present an obstacle to the plan,

for those provisions of the statuLe in conflict with the

plan have been declared unconstituLIonal . Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., F. Supp. ____

(W.D.N.C. 1970).8

The district court properly disapproved the school

board's elementary school proposal because it left about

one-half of both the black and white elementary pupils in

schools that were nearly completely segregated. Part of

the difficulty concerning 'the elementary schools results

from the board's refusal to accept the district court's

suggestion that it consult experts from the Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare. The consultants that the

board employed were undoubtedly competent, but the board

8. The unconstitutional provisions are:

"No student shall be assigned or compelled to

attend any school on account of race, creed,

color or national origin, or for the purpose

of creating a balance or ratio of race, re

ligion or national origins. Involuntary bus

sing of students in contraveneion of this

article is prohibited, and public funds shall

not be used for any such bussing.” N.C. Gen.

Stat. § 115-176.1 (Supp. 196^> /

>

1

-22-

* *J T . i *

limited their choice of remedies by maintaining each

school's grade structure. This, in effect, restricted

the means of overcoming segregation to only geographical

zoning, and as a further restriction the board insisted

on contiguous zones. The board rejected such legitimate

techniques as pairing, grouping, clustering, and satellite

zoning. Moreover, the board sought to impose a ratio in

each school of not less than 60% white students. While

a 60% - 40%> ratio of white to black pupils might be de

sirable under some circumstances, rigid adherence to this

formula in every school should not be allowed to defeat

integration.

On the other hand, the Finger plan, which the

district court approved, will require transporting 9,300

pupils in 90 additional buses. The greatest portion of

the proposed transportation involves cross-bussing to

paired schools -- that is, black pupils in grades one

through four would be carried to predominantly white

schools, and white pupils in the fifth and sixth grades

would be transported to the black schools. The average

daily roundtrip approximates 15 miles through central

city and suburban traffic.

-23-

The additional elementary pupils who must be

bussed represent an increase of 397, over all pupils

presently being bussed, and their transportation will

require an increase of about 327, in the present fleet of

buses. When the additional bussing for elementary pupils

is coupled with the additional requirements for junior

and senior high schools, which we have approved, the total

percentages of increase are: pupils, 567, and buses, 497.

The board, we believe, should not be required to undertake

such extensive additional bussing to discharge its obliga

tion to create a unitary school system.

- ' .• • ■ ■ • IV. :

Both parties oppose a remand. Each side is adamant

that its position is correct -- the school board seeks total

approval of its plan and the plaintiffs insist on imple

mentation of the Finger plan. We are favorably impressed,

however, by the suggestion of the United States, which at

our invitation filed a brief as amicus curiae, that the

school board should consider alternative plans, particularly

for the elementary schools. We, therefore, will vacate the

judgment of the district court and remand the case for recon

-24-

sideration of the assignment of pupils in the elementary

schools, and for adjustments, if any, that this may re

quire in plans for the junior and senior high schools.

On remand, we suggest that the district court

should direct the school board to consult experts from

the Office of Education of the Department of Health, Edu

cation, and Welfare, and to explore every method of desegre

gation, including rezoning with or without satellites,

pairing, grouping, and school consolidation. Undoubtedly

some transportation will be necessary to supplement these

techniques. Indeed, the school board's plan proposed

transporting 2,300 elementary pupils, and our remand

should not be interpreted to prohibit all bussing. Further

more, in devising a new plan, the board should not perpet

uate segregation by rigid adherence to the 607o white-407o

black racial ratio it favors.

Ifj despite all reasonable efforts to integrate

every school, some remain segregated because of residential

patterns, the school board must take further steps along

the lines we previously mentioned, including a majority

-25-

to minority transfer plan, t o AKHwyy* that no pupil is

excluded from an integrated .u 'vm\ v'w the basis of ract .

Alexander v. Holmes y of Ed>j 395

U.S. 19 (1969), and Carter v. VI*M VVUciana School Bd.,

396 U.S. 290 (1970), emphasis* M um Hthool boards must

forthwith convert from dual to Ui\h,U y systems. In Nes-

bit v. Statesville City Bd. of: f',d, , / , F>2d 1040 (4th

9

Cir. 1969), and VJhittenberg v, 'U'htinl Dist. of Greenville

9. The board's plan provides;

"Any black student wilI I

transfer only if the sr|

is originally assigned !

per cent of his race <1

he is requesting to at

30 per cent of his roe

space. Any white stud

to transfer only if 1 li

is originally assigned

per cent of his race u

is requesting to atten

per cent of his race n

in

I e

e

e 11

15

li

ud

d

ud

“ I'n 1 inftted to

''"I li» which he

1'■ * "lure than 30

I I I lie school

• nM less thanud

‘""I 111\m available

* '',ll| be permitted

,u hno | to which he

'Ui inure than 70

II I lie school he

luut less than 70

This clause, which was ̂ des | (() prevent tipping or

resegregation, would be suitable , , fl(1 schoois in the

system were integrated. But , )|(? board envisions some

elementary schools will remain /(eMi|y black, it unduly

restricts the schools to whirl) pu,,||t, these schools can

transfer. It should be amended ( / ( j j ow tbese elementary

pupils to transfer to any sclmnl |,, v/} 1 ich their race is a

minority if space is available,

\

-20-

County, ---- F.2d ---- (4th Cir. 1970), we reiterated that

immediate reform is imperative. We adhere to these prin

ciples, and district courts in this circuit should not con

sider the stays which were allowed because of the exception.il

nature of this case to be precedent for departing from the

directions stated in Alexander, Carter, Nesbit, and Whitten-

berg. . •

Prompt action is also essential for the solution

of the remaining difficulties in this case. The school

board should immediately consult with experts from HEW

and file its new plan by June 30, 1970. The plaintiffs

should file their exceptions, if any, within 7 days, and

the district court should promptly conduct all necessary

hearings so that the plan may take effect with the opening

of school next fall. Since time is pressing, the district

court s order approving a new plan shall remain in full

force and effect unless it is modified by an order of this

court. After a plan has been approved, the district court

may hear additional objections or proposed amendments, but

the parties shall comply with the approved plan in all

-27-

respects while the district court considers the suggested

modifications. Cf. Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Ed.,

418 F.2d 1040, 1043 (4th Cir. 190).

Finally, we approve the district court's inclu

sion of Dr. Finger's consultant fee in the costs taxed

against the board. See In the Matter of Peterson, 253

U.S. 300, 312 (1920). We caution, however, that when a

court needs an expert, it should avoid appointing a person

who has appeared as a witness for one of the parties. But

the evidence discloses that Dr. Finger was well qualified,

and his dual role did not cause him to be faithless to the

trust the court imposed on him. Therefore, the error,

if any, in his selection, was harmless.

We find no merit in the other objections raised

by the appellants or in the appellees' motion to dismiss

the appeal. The judgment of the district court is vacated,

and the case is remanded for further proceedings consistent

with this opinion.

-28-

SOBELOFF, Circuit Judge, with whom WINTER, Circuit Judge,

joins, concurring in part and dissenting in part:

Insofar as the court today affirms the District Court's

order in respect to the senior and junior high schools, I

concur. I dissent from the failure to affirm the portion

of the order pertaining to the elementary schools.

I ' ' ' :

THE BASIC LAW AND THE PARTICULAR FACTS

All uncertainty about the constitutional mandate of

Brown v. Board of Education. 347 U.S. 483 (1954) and 349

U.S. 294 (1955), was put to rest when in Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County the Supreme Court spelled

out a school board's "affirmative duty to take whatever

steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary system in

which racial discrimination would be eliminated root and

branch," 391 U.S. 430, 437-438 (1968) . "Disestablish [ment

of] state-imposed segregation" (at 439) entailed "steps

which promise realistically to convert promptly to a system

without a 'white* school and a 'negro' school, but just

schools" (at 442). If there could still be doubts they were

29

T.

answered this past year. In Alexander v. Holmes County

Board of Education, the Court held that " [u]nder explicit

holdincs of this Court the obligation of every school

district is to terminate dual school systems at once and

to operate now and hereafter only unitary schools," 396

U.S. 19, 20 (1969). The command was once more reaffirmed

in Carter v. West Feliciana School Board, 396 U.S. 290

(1970), requiring "relief that will at once extirpate any

lingering vestiges of a constitutionally prohibited dual

school system." (Harlan, J., concurring at 292).

We face in this case a school district divided along

racial lines. This is not a fortuity. It is the result,

as the majority has recognized, of government fostered

residential patterns, school planning, placement, and,

as the District Court found, gerrymandering. These factors

have interacted on each other so that by this date the black

and white populations, in school and at home, are virtually

entirely separate.

As of November 7, 1969, out of 106 schools in the

system, 57 were racially identifiable as white, 25 were

30

racially identifiable as black.^ of these, nine were all

white schools and eleven all black. Of 24,714 black students

in the system, 16,000 were in entirely or predominantly black

schools.

There are 76 elementary schools with over 44,000 pupils.

In November 1969, 43 were identifiable as white, 16 as black,

with 13 of the latter 98% or more black, and none less than

65%. For the future the Board proposes little improvement.

There would still be 25 identifiably white elementary schools

and approximately half of the white elementary students

would attend schools 85 to 100% white. wine scnools would

remain 83 to 100% black, serving 6,432 students or over half

the black elementary pupils.

To call either the past or the proposed distribution a

"unitary system" would be to embrace an illusion.* 2 And the

1* the entire system, 71% of the pupils are white,

29% of the pupils are black. The District Judge deemed

a school having 86% or greater white population identifiable

as white, one with 56% or greater black population identi

fiable as black.

2. In its application to us for a stay pending appeal,

counsel for the School Board relied heavily on Northcross v.

Board of Education of Memphis, ___ F.2d ___ (6th Cir. 1970),

as a judicial ruling that school assignments based on resi

dence are constitutionally immune. The defendant tendered

(footnote cont'd on page 4)

31

majority does not contend that the system is unitary, for

it holds that "the district court properly disapproved the

school board's elementary school proposal because it left

about one-half of both the black, and white elementary pujils

in schools that were’nearly completely segregated." The

Board's duty then is plain and unarguable: to convert to

a unitary system. The duty is absolute. It is not to be

tempered or watered down. It must be done, and done now.

II

THE COURT-ORDERED PLAN

A. The Necessity of the Court-Ordered ..Plan

The plan ordered by. the District Court works. It does

the job of desegregating the schools completely. This

"places a heavy burden upon the board to explain its

preference for an apparently less effective method.

Green, supra at 439. '

The most significant fact about the District Court's

plan is that it— or one like it— is the only one that can

(footnote 2 cont'd from page 3)

us a statistical comparison of pupil

with pupil population by attendance

school system.

enrollment by school

area for the Memphis

Since then the Supreme Court in Northcross has ruled

that the Court of Appeals erred insofar as it held tha

Memphis board "is not now operating a 'dual school system

***." 38 L.W. 4219.

32

• *1

work. Obviously, when the black students are all on one

side of town, the whites on the other, only transportation

will bring them together. The District Judge is quite

explicit:

Both Dr. Finger and the school board staff

appear to have agreed, and the court finds

as a fact, that for the present at least,

there is no way to desegregate the all-black

schools in Northwest Charlotte without pro

viding (and continuing to provide) bus or

other transportation for thousands of children.

plans and all variations of plans con

sidered for this purpose lead in one fashion

or another to that conclusion.

The point has been perceived by the counsel for the Board,

who have candidly informed us that if the job must be done

then the Finger plan is the way to do it.

The only suggestion that there is a possible alterna

tive middle course came from the United States, participat

ing as amicus curiae. Its brief was prefaced by the

following revealing confession:

We understand that the record in the case

is voluminous, and we would note at the outset

that we have been unable to analyze the record

as a whole. Although we have carefully examined

the district court's various opinions and orders,

the school board's plan, and those pleadings readily

available to us, we feel that we are not conversant

with all of the factual considerations which

may prove determinative Of this appeal.

/ccordingly, we here attempt, not to deal

extensively with factual matters, but rather

to set forth some legal considerations which

may be helpful to the Court.

Notwithstanding this disclaimer, the Government went on

to imply in oral argument— and has apparently impressed

on this court--that HEW could do better. No concrete

solution is suggested but the.Government does advert to

the possibility of pairing and grouping of schools. Two

points stand out. First, pairing and grouping are pre

cisely what the Finger plan, adopted by the District

Court, does. Second, in the circumstances of this case,

these methods necessarily entail bussing.

I am not "favorably impressed" by the Government's

performance. Its vague and noncommital representations

do little but obscure the real issues, introduce uncertainty

and fail to meet the "heavy burden" necessary to overturn

3the District Court's effective plan. 3

3. A federal judge is not required to consult with

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare on legal

issues. What is the constitutional objective of a plan,

and whether a unitary system has been or will be achieved,

are questions for the court. HEW's interpretation of the

(footnote cont'd on page 7)

3^

B. The Feasibility of the Plan

Of course it goes without saying that school boards

(footnote 3 cont'd from page 6)

constitutional command does not bind the courts.

[W]hile administrative interpretation may lend

a persuasive gloss to a statute, the definition

of constitutional standards controlling the

actions of states and their subdivisions is

peculiarly a judicial function.

Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City County,

382 F.2d 326 (1967).

Although the definition of goals is for the court,

HEW may be able to provide technical assistance in over

coming the logistical impediments to the desegregation

of a school system. Thus it was quite understandable

that at the outset of this case the District Court in-

the Board to consult with HEW. Desegregation of

this large educational system was likely to be a complex

and administratively difficult task, in which the ex

pertise of the federal agency might be of help. However,

after a substantial period of time and the beginning of

a new school year, it became clear that the Board had no

intention of devising a meaningful plan, much less seek

ing advice on how to do so. At that point (December 1969)

with the need for speed in mind, the Judge appointed an

expert already familiar with the school system to work

with the school staff in developing a plan.

Whether to utilize the assistance of HEW is ordinarily

up to the district judge. Consultation in formulating the

mechanics of a plan is not obligatory. The method used by

the Judge in this case was certainly sufficient. Moreover,

now that a plan has been created and it appears that there

are no real alternatives, a remand for HEW's advice seems

an exercise in futility.

35

are not obligated to do the impossible. Federal courts

do not joust at windmills. Thus it is proper to ask

whether a plan is feasible, whether it can be accomplished.

There is no genuine dispute on this point. The plan is

simple and quite efficient. A bus will make one pickup

in the" vicinity of the children's residences, say in the

white residential area. It then will make an express trip

to the inner-city school. Because of the non-stop feature,

time can be considerably shortened and a bus could make a

return trip to pick up black students in the inner city and

to convey them to the outlying school. There is no evidence

of insurmountable traffic problems due to the increased

bussing.4 Indeed, straight line bussing promises to be

The only indication I have encountered that a serious

traffic problem will be occasioned by the additional bussing

is found in an affidavit by the City Director of Traffic Engi

neering. His statement is based on the exaggerated bus esti

mate prepared by the Board and rejected by the District Court.

See note 5, infra. Moreover, he appears to have relied to

q large extent on the erroneous assumption that under the plan

busses would pick up and discharge passengers along busy

thoroughfares, thus causing "stop—and—go traffic of slow

moving school busses in congested traffic.'

A later affidavit of the same official, filed at the re

quest of the District Court, affords more substantial data.

It reveals that the total estimated number of automobile trips .

per day in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (not including

internal truck trips) is 869,604. That the 138 additional

busses would gravely aggravate the congestion is dubious, to

say the least.

36

quicker. The present average one-way trip is over 15 miles

and takes one hour and fourteen minutes; under the plan the

average one-way trip for elementary students will be less

than seven miles and 35 minutes. The cost of all of the

additional bussing will be less than one week's operating

budget.^

C . The Standard of Review

In Brown II, the Supreme Court charged the district

courts with the enforcement of the dictates of Brown I.

The lower courts were to have "a practical flexibility in

shaping * * * remedies." 349 U.S. at 300. Thus, in

subsuming these cases under traditional equity principles, 5

5. The District Judge rejected the Board's inflated

claims, and found that althogether the Finger plan would

bus 13,300 new students in 138 additional busses. The

Board had estimated that 19,285 additional pupils would

have to be transported, requiring 422 additional busses.

This estimate is disproportionate on its face, for

presently 23,600 pupils are transported in 280 busses.

As indicated above, the direct bus routes envisioned by

the Finger plan should accomplish increased, not diminished,

efficiency. The court below, after close analysis, dis

counted the Board's estimate for other reasons as well,

including the "very short measurements" used by the Board

in determining who would have to be bussed, the failure

of the Board to account for round-trips, staggering of

opening and closing hours, and overloads.

37

the Supreme Court brought the' desegregation decree v/ithin

the rule that to be overturned it "must [be] demonstrate [d]

that there was no reasonable basis for the District Judge's

decision." United States v. W. T. Grant Co.. 345 U.S. 629,

634 (1953). This court has paid homage to this maxim of

appellate review when, in the past, a district judge has

ordered less than comprehensive relief. Bradley v. School

Board of the City of Richmond. 345 F.2d 310, 320 (1965),

revl<3/ 382 U.S. 103 (1965). What is called for here is

similar deference to an order that would finally inter

the dual system and not preserve a nettlesome residue. As

the Supreme Court made clear in Green, supra, those who

would challenge an effective course of action bear a

"heavy burden." The Finger plan is a remarkably economical

scheme when viewed in the light of what it accomplishes.

There has been no showing that it can be improved or

replaced by better or more palatable means. It should,

then, be sustained.

38

Ill

OBJECTIONS RAISED AGAINST TIIP: COURT--ORDERED PLAN

The "Illegal" Objective of the Plan

My Brother Bryan expresses concern about the plan,

regardless of cost, because it undertakes, in his view,

an illegal objective; "achieving racial balance." What

ever might be said for this view abstractly or in another

context, it is not pertinent here. We are confronted in

this case with no question of bussing for mere balance

unrelated to a mandatory constitutional goal. What the

District Court has ordered is compliance with the

constitutional imperative to disestablish the existing

segregation. Unless we are to palter with words, de

segregation necessarily entails integration, that is to say

integration in some substantial degree. The dictum to

the contrary in Briggs v. Elliott. 132 F. Supp. 776

(E.D.S.C. 1955), was rejected by necessary implication

by the Supreme Court in Green, supra, and explicitly by

this court in Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick Co.

413 F.2d 53, 54 n.2 (4th Cir. 1969).

As my Brother Winter shows, there is no more suitable

way of achieving this task than by setting, at least

39

initially, a ratio roughly approximating that of the racial

population in the school system. The District Judge adopted

this ad hoc measurement as a starting guide, expressed a

willingness to accept a degree of modification,6 and de-

parted from it where circumstances required.

B * —he "Unreasonableness" of the Plan

The majority does not quarrel with the plan’s objective,

nor, accepting the findings of the District Court, does it

really dispute that the plan can be achieved. Rather, we

are told, the plan is an unreasonable burden.

This notion must be emphatically rejected. At bottom

it is no more than an abstract, unexplicated judgment--*

conclusion of the majority that, all things considered,

desegregation of this school system is not worth the price.

This is a conclusion neither we nor school boards are

permitted to make.

that 6‘ The Di3trict Jud9e wrote in his December 1 order

will not^ ratf°S °f pupils in particular schools

JLll not be set. if the board in one of its three

tries had presented a plan for desegregation the

inUpuPU UrfthaVe S°Ught WaYS tD apPr°Ve variationsin pupil ratios. in default of any such plan from

the school board, the court will start with the

23°US a ; ° 2 gi”ally advanced ^ the order of April

ra^-o fPforts sh°nld be made to reach a 71-29

ratio in the various schools so that there will be

no basis for contending that one school is racially

different from the others, but to understand that

variations from that norm may be unavoidable.

^0

nw*"Tir?

In making policy decisions that are not constitutionally

' d;LCtated' state authorities are free to decide in their

discretion that a proposed measure is worth the cost in

volved or that the cost is unreasonable, and accordingly

they may adopt or reject the proposal. This is not such

a case. Vindication of the plaintiffs' constitutional

right does not rest in the school board's discretion, as

the Supreme Court authoritatively decided sixteen years

ago and has repeated with increasing emphasis.' It is not

, for the Board or this court to say that the cost of com-

pliance with Brown is "unreasonable."

That a subjective assessment is the operational part

of the new ''reasonableness" doctrine is highlighted by a

study of the factors the majority bids school boards take

into account in making bussing determinations. "[a ] school

board should take into consideration the age of the pupils,

the distance and time required for transportation, the

effect on traffic, and the cost in relation to the board's

resources." But as we have seen, distance and time will

be comparatively short, the effect on traffic is undemonstrate

the incremental cost is marginal. As far as age is con

cerned, it has never prevented the bussing of pupils in

4 l

Charlotte-Mccklenburg, or in North Carolina generally, where

70.9% of all bussed students are elementary pupils.

If the transportation of elementary pupils were a

novelty sought to be introduced by the District Court, I

could understand my brethren’s reluctance. But, as is

conceded, bussing of children of elementary school age is

an established tradition. Bussing has long been used to

perpetuate dual systems.7 More importantly, bussing is a

recognized educational tool in Charlotte—Mecklenburg and

North Carolina. And as the National Education Association

has admirably demonstrated in its brief, bussing has played

a crucial role in the evolution from the one-room school-

house in this nation. Since the majority accepts the

legitimacy of bussing, today’s decision totally baffles me.

In the final analysis, the elementary pupil phase of

the Finger plan is disapproved because the percentage

7. For some extreme examples, see: School Board of

Warren County v. Kelly, 259 F .2d 497 (4th Cir. 1958);

Corbin v. County School Bd. of Pulaski County, 117 F.2d

924 (4th Cir. 1949); Griffith v. Bd. of Educt of Yancey

County, 186 F. Supp. 511 (W.D.N.C. 1960); Gains

v. County School Bd. of Grayson County, 186 F. Supp. 753

(W.D.Va. 1960), stay denied, 282 F.2d 343 (4th Cir. 1960).

See also, Chambers v. Iredell Co., F.2d (4th Cir.

1970) (dissenting opinion) .

h2

4.

increase in ̂ „ ,— ••v Xo somehow determined to be too onerous.

Why this is so ^not told. The Board plan itself would

bus 5000 addi~' v- _ pupils. The fact remains that in North

Carolina 55% c- • , , .pupils are now being bussed. Under the

Finger plan, a-- ̂ -xiriately 47% of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

student populat' x- .i D aid be bussed. This is well within

the existing ., , . ̂ " — throughout the state.

The majoritro* <; ,- - proposal is inherently ambiguous. The

court-ordered nlrr- ' - c-, • ̂ t.* Said to be unreasonable. Yet the

School Board's cv- , , .oi has also been disapproved. Does

the decision— tho- ~ v ^ • . ." - linger plan is unreasonable— depend

on the promise ̂ ,^^ ' 1 intermediate course is available?

Would the amount -- . . , .— segregation retained m the School

8

8. The majocrc

portion of the clir

pupils, 32% increr<

is said, would r e m

increase.

calculates the elementary school

-ean a 39% increase in bussed

- busses; the whole package, it

a. 56% pupil increase and 49% bus

These figure

story. if one ir.o

presently beincr nr:

commercial lines

would not appear r

elementary schools

increment, the whs.

^ —ccurate but do not tell the whole

"within the number of students

•^xrrrted those that are bussed on

■‘-hej increase in pupils transported

^ 3 5 large. Thus the plan for

3— r entail a 33% bussed pupil

^"3rger plan, 47%.

43

Board's plan be avowedly sanctioned if it were recognized

that nothing short of the steps delineated in the District

Court's plan will suffice to eliminate it? Since there is

no practicable alternative, must we assume that the majority

is willing to tolerate the deficiencies in the Board plan?

These questions remain unresolved and thus the ultimate

meaning of the "reasonableness" doctrine is undefined.

Suffice it to say that this case is not an appropriate one

in which to grapple with the theoretical issue whether the

law can endure a slight but irreducible remnant of segregated

schools. This record presents no such problem. The remnant

Of 2TclC."ioll"lw i rlonf i -P-J ->—u — -LU elementarv schools 4-̂

District Court addressed itself, encompasses over half

the elementary population. This hrge fraction cannot be

c lied slight, nor, as the Finger plan demonstrates, is

it irreducible.

I am even more convinced of the unwisdom of reaching

out to fashion a new "rule of reason," when this record is

far from requiring it, because of the serious consequences

it would portend for the general course of school

desegregation. Handed a new litigable issue-the so-called

reasonableness of a proposed plan-school boards can be

44

' ' 'T T W 1*** —

expected to exploit it to the hilt. The concept is highly

susceptible to delaying tactics in the courts. Everyone

can advance a different opinion of what is reasonable.

Thus, rarely would it be possible to make expeditious

disposition of a board's claim that its segregated system

not reasonably eradicable. Even more pernicious, the

new-born rule furnishes a powerful incentive to communities

to perpetuate and deepen the effects of race separation

so that, when challenged, they can protest that belated

remedial action would be unduly burdensome.

Moreover, the opinion catapults us back to the time,

thought passed, when it was the fashion to contend that

the inquiry was not how much progress had been made but

the presence or absence of good faith on the part of the

board. Whether an "intractable remnant of segregation-

can be allowed to persist, apparently will now depend in

g measure on a slippery test: an estimate of whether

the Board has made "every reasonable effort to integrate

9 -

the pupils under its control."

9- Both in its characterization of t-he . .

its treatment of the case the nv-,in ? , facts and ln

actions of this Board have ^ ma3°tity implies that the

4. . s i3oarcl have been exemplary T f^«i 4-to register my dissent- ^ P y ' 1 *eel constrainedmy dissent from this view although on no account

(cont'd p. 18)

45

T"."" " ’S" f

The Supreme Court having barred further delay by its

insistent emphasis on an immediate remedy, we should not

lend ourselves to the creation of a new loophole by

attenuating the substance of desegregation.

9. (cont'd from p. 17)

the^aS:rdCe1 enedst0onth?hLr°CsSie“ 0n ^

Charlo«e-M1c\le;b“ fsc\\\rbLrtrL?1Segaen ared ^He found it unnecessary at t-hat * R e g a l l y segregated.the Board hirl li k ? ? time t 0 decide whethertne Board had deliberately gerrymandered to perpetuate tt ^system since he believed that the . , P rpetuate the du<

promote substantial changes The Ron ,°rder to foll°" would

May 15 to devise a „l „ I? ™ was glven untils L - u j . plan eliminatrng faculty and student

A majority of the Board voted not to taVe

below_ y ^-cording to the court

No express guidelines were given the superintendent

wever, the views of many members expressed at the"

meeting were so opposed to serious and substantial

.̂ segregation that everyone including the super

intendent could reasonably have concluded as the

court does, that a ■■minimal" plan „a£ wha;

a prelufer; the "Plan" was essentiallya prelude to anticipated disapproval and appeal.

* * * * * * *

The staff were never directed to do

on re-drawing of school zone lines,

(cont'd p. 1 9 )

any serious work

pairing of schools,

M6

L .

(cont'd from p. 18)

combining zones, grouping of schools, conferences

with the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, nor any of the other possible methods

of making real progress towards desegregation.

The superintendent's plan was submitted to the Board

on May 8 . it was quite modest in its undertaking. Never

theless, the Board "struck out virtually all the effective

provisions of the superintendent's plan." The plan

ultimately filed by the Board on May 28 was "the plan

previously found racially discriminatory with the addition

of one element— the provision of transportation for

[majority to minority transfers.]" The Board also added

a rule making a student who transfers to a new high school

ineligible for athletics for a year. As the District Judge found,

[t]he effect of the athletic penalty is obvious—

it discriminates against black students who may

v;ant to transfer and take part in sports, and is no

penalty on white students who show no desire for such transfers.

In the meantime the Board for the first time refused

to accept a recommendation of the superintendent for the

promotion of a teacher to principal. The reason avowed was

that the teacher, who was black and a plaintiff in the

suit, had publicly expressed his agreement with the District

Court order. The job was withheld until the prospective

appointee signed a "loyalty oath."

The District Judge held a hearing on June 16 and ruled

on June 20. He declined to find the Board in contempt

but did note that"[t]he board does not admit nor claim that it has any positive

(cont'd on p. 2 0)

47

1

(cont'd from page 19)

ophy."' 7 “ y trUe neighborhood school philos-

Di strict Judge was^leased t^learn that ^ t h e V h 3"! ThE has reversed its field anH ion at the Sch°o1 Board

constitutional duty to desegregatrpupils^teach™ 3^ 6

“ 1 st the^arliest^ossible

“ ereby'sevefa^rwacl

= - ■ = a z ^ I s l f L H « ~ 7 “

complete desegregation in November. P °r

black nuDilq" l I instead of the promised 4245 pupils had been transferred (t ■ c.revealed that •, * (Later informationarea that the number was onlv 767 ̂ pllvrt found that Y ] Furthermore, he

accoprtheT, “ ficated that lts combers do not accept the duty to desegregate the schools at

any ascertainable time; and they have clearly

indicated that they intend not to do it effective

a V v ^ - n f 1 of, 1970- They have also demonstrated

a yawning gap oetween predictions and performance.

On November 17, the Board filed a n l m T +. „ , . further consideration ot • • d plan. it 'discarded

transporting. ■■ ^

provrded that white students would not be assigned to

S T S ;* ::reT̂ :y„ t v s ^his was, as the District Court found, a one-

(cont'd p. 21)

48

n ^ e f f o i t ^ ' V 1™ °f th° faCt that :ho plan contemplated blacks The desegregate schools with greater than 40%

to the JuIv°29an1aranSfhrred t0 °Utlying schools Pursuant

th.

part o f f aC® o f t h ± S t 0 t a l l a c k o f cooperation on the

expert t o ^ ' the court was compelled to appoint an,P devise a plan for desegregation. The Finqerplan was the result. linger

It appears from the record that on most issues the

Board^was sharply divided. of course I mean to cast no

aspersions on those members— and th»r« ___ __-

theeahthe B°ard f°rthrightly to shoulder'"its &duty. ̂ But

that ?hVe PeCltal °f eVents demonstrates beyond doubt that this Board, through a majority of its members f a r

from making "every reasonable effort" to f u l f i l l s

constitutional obligation, has resisted and delayed

desegregation at every turn. Y a

(cont'd from page 20)

49

Albert V. Bryan, Circuit t ,

■ . cult J^ e , dissenting in part;

The Court commands the Chan,

■ °f ^cation to provide busing of ' ^ ^ ' ^ ‘-burg Board

^ U — - * • Phtuc schools

r r - 1

raClal Jiaî is the Objective. Busing " b ^ " 3

imbalance is not as vgt; ° racial

f°~» bo matter the prior or °bll8atlon- There-

thlS ^ °ther reaoo„s, a„d r e ^ l L ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

" dUPUCati°" - « ’e bus routes, 1 th "

B°t Stand. th "k the injunction can-

Without Constitutional ordain

^ Federal courts to order the B P°“er “

1 - bo authority th i ? ^ ^ " “ * “ -

implications or Brown v B Const“ ««°n, or in the

Bo* its derivatives, repair" ^ ^ ^

‘o apportion the schoo! bodies ln ^ ^ *° endeaTOr

"hole school system. raClal ratio °f the

The majority-opinion presunno

^ aiS° hBBinn to achieve it, c - Cial balah=e,

UUt W ‘e ChlSI' Justice or the V n U e T Z l T ^ ’

seated inquiry on whether " 63 ^ reCen‘ly sug-nether any particular racial h„ 'racial balance must

I

i

50

- -■ ! iiM y \ "fw & pm

be achieved in the schools; . . . [and] to what extent trans

portation may or must be provided to achieve the ends sought

by prior holdings of the Court." See his memorandum appended

to Northcross v. Board of Education of the Memphis, Tennessee,

City Schools, ___US___, 38 USLW 4219, 4220 (March 9, 1970).*

Even construed as only incidental to the 1964 Civil

Rights Act, this legislation in 42 United States Code § 2000c-6

is necessarily revealing of Congress' hostile attitude toward

the concept of achieving racial balance by busing. It unequivo

cally decried in this enactment "any order [of a Federal court]

seeking to achieve a racial balance in anv school ĥ r

the transportation of pupils or students from one school to

another . . . to achieve such racial balance . . . .11

I would not, as the majority does, lay upon Charlotte-

Mecklenburg this so doubtfully Constitutional ukase.

* On remand the District Court in Northcross has held there

was no Constitutional obligation to transpor pupils to over

come a racial imbalance. Northcross v. Board of Education of

the Memphis City Schools, ___FS___ (W.D.Tenn., May 1, 1970)

(per McRae, J.). In the same Circuit, see, too, Deal v.

Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F2d 1387 (6 Cir. 1969).

51

WINTER, Circuit Judge, concurring in part and

dissenting in part:

I would affirm the order of the district court

*in i.ts entirety.

In a school district in which freedom of choice has

patently failed to overcome past state policy of segregation

and to achieve a unitary system, the district court found the

reasons for failure. They included resort to a desegregation

plan based on geographical zoning with a free transfer provi

sion, rather than a more positive method of achieving the

constitutional objective, the failure to integrate faculties,

the existence of segregated racial patterns partially as a

result of federal, state and local governmental action and

the use of a neighborhood concept for the location of schools

superimposed upon a segregated residential pattern. Correct-

Certainly, if the district court's order

with respect to high schools and junior

high schools is affirmed, the district

court should not be invited to recon

sider its order with respect to them.

The jurisdiction of the district court

is continuing and it may always modify

its previous orders with respect to any

school upon application and for good

cause shown.

52

v

ly the majority accepts these findings under established

principles of appellate review. To illustrate how govern

ment-encouraged residential segregation, coupled with the

discriminatory location and design of schools, resulted in

a dual system, the majority demonstrates that in this lo

cality busing has been employed as a tool to perpetuate

segregated schools.

In complete compliance with Carter v. West Feli

ciana—School Board, _____ U. S. _____ (1970) ; Alexander v.

Holmes County Bd. of Ed.. _____ U. S. _____ (1969); Green

v. School Bd. of New Kent County. 391 U. S. 430 (1968), and

^Q^roe v • Bd. of Comm1 rs. , 391 U. S. 450 (1968) the major

ity concludes that the existing high school and junior high

school systems must be dismantled and that the constitution

al mandate can be met by the use of geographical assignment,

including satellite districts and busing.

The majority thus holds that the Constitution re

quires that this dual system be dismantled. It indicates

its recognition of the need to overcome the discriminatory

educational effect of such factors as residential segrega

tion. It also approves the use of zones, satellite districts

resultant busing for the achievement of a unitary system

- * * W>.- ^ f - r rf4t

at the high school and junior high school levels. Neverthe-

V

less, the majority disapproves a similar plan for the deseg

regation - j f the elementarv schools on the ground that the

busing involved is too onerous. I believe that this ground

is insubstantial and untenable.

At the outset, it is well to remember the seminal

declaration in Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II), 349

U. S. 294, 300 (1955), that in cases of this nature trial

courts are to "be guided by equitable principles" in

"fashioning and effectuating decrees." Since Brown II the

course of decision has not departed from the underlying

premise that this is an equitable proceeding, and that the

district court is invested with broad discretion to frame

a remedy for the wrongful acts which the majority agrees

have been committed. In Green v. School Board of New Kent

County, 391 U. S. at 438, the Supreme Court held that the

district courts not only have the "power" but the "duty to

render a decree which will, so far as possible, eliminate

the discriminatory effects of the past, as well as bar like

discrimination in the future. " Dis* rict courts were directed

to "retain jurisdiction until it is clear that disestablish-

5>4

■ w 1"’*

aL the high school and junior high school levels. Never the-

\

less, the majority disapproves a similar plan for the deseg

regation of the elementarv schools on the ground that the

busing involved is too onerous. I believe that this ground

is insubstantial and untenable.

At the outset, it is well to remember the seminal

declaration in Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II), 349

U. S. 294, 300 (1955), that in cases of this nature trial

courts are to "be guided by equitable principles" in

"fashioning and effectuating decrees." Since Brown II the

course of decision has not departed from the underlying

premise that this is an equitable proceeding, and that the

district court is invested with broad discretion to frame

a remedy for the wrongful acts which the majority agrees

have been committed. In Green v. School Board of New Kent

County, 391 U. S. at 438, the Supreme Court held that the

district courts not only have the "power" but the "duty to

render a decree which will, so far as possible, eliminate

the discriminatory effects of the past, as well as bar like

discrimination in the future." Dis*rict courts were directed

to "retain jurisdiction until it is clear that disestablish-

54

>***Sjr«* *'-v : T O T

ment has been achieved. Raney v. Board of Education. 391

U. S. 443, 449 (1968). Where it is necessary district

courts may even require local authorities "to raise funds

adequate to reopen, operate, and maintain without racial

discrimination a public school system." Griffin v. School

Board, 377 U. S. 218, 233 (1964). Thus, the Supreme Court

has made it abundantly clear that the district courts have

the power, and the duty as well, to fashion equitable reme

dies designed to extirpate racial segregation in the public

schools. And in fashioning equitable relief, the decree of

a district court must be sustained unless it constitutes a

clear abuse of discretion. United States v. V,T. T. Grant Co.,

345 U. S. 619 (1953).

Busing is among the panoply of devices which a

court of equity may employ in fashioning an equitable remedy

in a case of this type. The district court's order required

that "transportation be offered on a uniform non-racial basis

t-o children whose attendance in any school is necessary

to bring about reduction of segregation, and who lives far

ther from the school to which they are assigned than the

determines to be walking distance. " It found as a

55

fact, and I accept its finding, that "there is no way" to

.

j. desegregate the Charlotte schools in the heart of the black

community without providing such transportation.

The district court's order is neither a substan-1j

tial advance nor extension of present policy, nor on thisi

record does it constitute an abuse of discretion. This

school system, like many others, is now actively engaged in

the business of transporting students to school. Indeed,

busing is a widespread practice in the United States. U. S.

Commission on Civil Rights, Racial Isolation in the Public

Schools 180 (1967). Between 1954 and 1967 the number of

pupils using school transportation has increa.sed from

9,509,699 to 17,271,718. National Education Association,

National Commission on Safety Education, 1967-68 Statistics

on Pupil Transportation 3.

Given its widespread adoption in American educa

tion, it is not surprising that busing has been held an ac

ceptable tool for dismantling a dual school system. In

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 380

F.2d 385, 392 (5 Cir.)(en banc), cert, den. sub. nom.

Caddo Parrish School Bd. v. United States, 389 U. S. 840

* i' »

\

56

1

rrr^y ' W T ' r y r * — JBpr m -' WTV '^ 1

(1967). the court ordered that bus service which was "gener-

p ovidod must bo routed so as to transport every student

"to the school to which he is assigned" provided that the

school "is sufficiently distant from his home to make him

eligible for transportation under generally applicable trans

portation rules. " Similarly, in Unit^ states v. Schod

1=1. 286 F. s. 786, 799 (N.D. 111. 1968), aff'd.. 404 F.2d

H25 (7 Cir. 1968), the court said that remedying the ef

fects of past discrimination required giving consideration to

"racial factors" in such matters as "assigning students" and

providing transportation of pupils. m addition, the Eighth

Cir°Uit in 2efflE_lb_Beasley, _____ F.2d _____ (8 cir. 19?0) _

recognized that busing is "one possible tool in the implemen

tation of unitary schools." And. finally, Griffin v.

Board, supra, makes it clear that- +-v,Q ^clear that the added cost of necessary

transportation does not render a plan objectionable.

1 turn, then, to the extent and effect of busing

of elementary school students as ordered by the district

court.

Presently, 23,600 students - 21% of the total

population - are bused, excluding some 5,000 pupils

57

‘ ‘ - ' - . - A * .

who travel to and from scho>i i .'•̂ 1 by public transportation.

school board operates 280 ™'u""> The average cost of fcus.ir.c

students is $39.92 per student- . .^ n*-» which one-half is born,:

"hy the state and one-half h,- »> .the board. Thus, the average