Rucho v Common Cause Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees

Public Court Documents

March 8, 2019

48 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rucho v Common Cause Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees, 2019. fdbc4a5b-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/abc47752-e4b0-4c6a-8b2d-6e89189a8f0b/rucho-v-common-cause-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

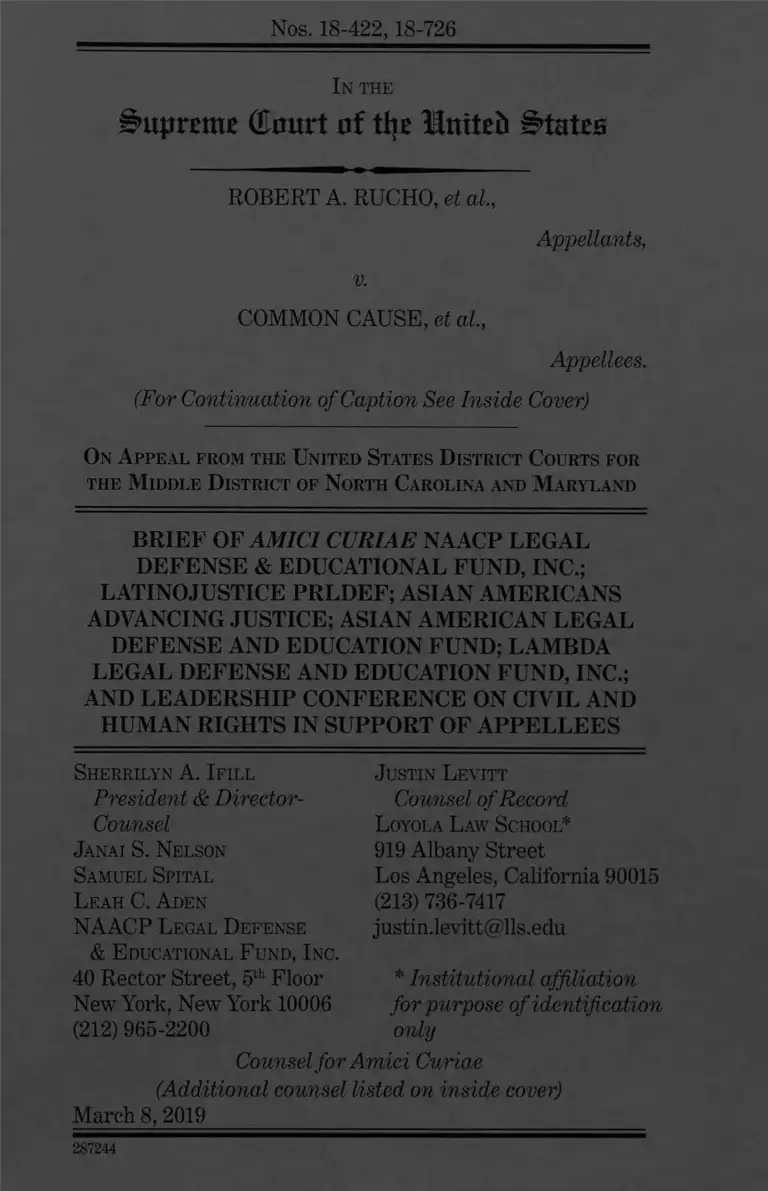

Nos. 18-422,18-726

In the

Supreme (tort of tl]r Hnitsi States

ROBERT A. RUCHO, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

COMMON CAUSE, et al.,

Appellees.

(For Continuation of Caption See Inside Cover)

On A ppeal from the United States D istrict Courts for

the M iddle D istrict of North Carolina and M aryland

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.;

LATINOJUSTICE PRLDEF; ASIAN AMERICANS

ADVANCING JUSTICE; ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND; LAMBDA

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.;

AND LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE ON CIVIL AND

HUMAN RIGHTS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

President & Director-

Counsel

Janai S. Nelson

Samuel Spital

L eah C. A den

NAACP L egal Defense

& E ducational F und, Inc.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, New York 10006

(212) 965-2200

Justin L evitt

Counsel of Record

L oyola L aw School*

919 Albany Street

Los Angeles, California 90015

(213) 736-7417

justin.levitt@lls.edu

* Institutional affiliation

for purpose of identification

only

Counsel for Amici Curiae

(Additional counsel listed on inside cover)

March 8,2019_________________________________

287244

mailto:justin.levitt@lls.edu

LINDA H. LAMONE, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

0. JOHN BENISEK, et al.,

Appellees.

Jennifer A. H olmes

NAACP L egal D efense

& E ducational F und, Inc.

700 14th Street N.W., Suite 600

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Laura W. Brill

Nicholas F. Daum

K endall Brill & K elly LLP

10100 Santa Monica Blvd.,

Suite 1725

Los Angeles, California 90067

(310) 556-2700

Counsel for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES......................................... ii

INTEREST OF THE AMICI......................................... 1

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF

THE ARGUMENT.......................................................... 1

A. A Cause of Action for Partisan

Gerrymandering Is Justiciable and

Requires Proof o f Invidious

Discrimination Against Voters Based

on Their Political Party Affiliation.............5

B. A Properly Structured Claim for

Partisan Gerrymandering Is

Consistent with the Voting Rights A ct... 19

C. A Properly Structured Claim for

Partisan Gerrymandering W ill Help

Avoid Detrimental Distortion in Cases

Brought Under Doctrines Involving

R ace.......................................................................... 23

CONCLUSION.............................................................33

APPENDIX................................................................... la

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

Federal Cases

Abbott v. Perez, 138 S. Ct. 2305 (2018)..................... 30

Bartlett v. Strickland, 556 U.S. 1 (2009).................. 24

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986)....................17

Benisek v. Lamone, 138 S. Ct. 1942 (2018).................7

Bethune-Hill v. Va. State Bd. of Elections, 137 S. Ct.

788 (2017)..........................................................19

City of Greensboro v. Guilford Cnty. Bd. of Elections,

251 F. Supp. 3d 935 (M.D.N.C. 2017)...... 11, 13

Clarke v. City of Cincinnati, 40 F.3d 807 (6th Cir.

1994).................................................................. 22

Comm, for a Fair & Balanced Map v. III. State Bd. of

Elections, 835 F. Supp. 2d 563 (N.D. 111. 2011)

(three-judge court)........................................... 28

Cooper v. Harris, 137 S. Ct. 1455 (2017)....... 2, 28, 30

Covington v. North Carolina, 316 F.R.D. 117

(M.D.N.C. 2016) (three-judge court), aff’d, 137

S. Ct. 2211 (2017)............................................. 24

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986)..............5, 18

Easley v. Cromartie, 532 U.S. 234 (2001)................. 30

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973)........... 6, 8

u

Garza v. Cnty. of Los Angeles, 918 F.2d 763 (9th Cir.

1990)..............................................................1, 29

Gill v. Whitford, 138 S. Ct. 1916 (2018)......................7

Goosby v. Town of Hempstead, 956 F. Supp. 326

(E.D.N.Y. 1997)................................................. 21

Goosby v. Town of Hempstead, 180 F.3d 476 (2d Cir.

1999) ..................................................................28

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704 (W.D. Tex. 1972)

(three-judge court), aff'd in part sub nom.

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)..........25

Harris v. Ariz. Ind. Redistricting Comm’n, 136 S. Ct.

1301 (2016).................................................12, 22

Heffernan v. City of Paterson, 136 S. Ct. 1412 (2016)

............................................................. ........................6

Hulme v. Madison Cnty., 188 F. Supp. 2d 1041 (S.D.

111. 2001)..................................................... 11, 13

Jordan v. Winter, 604 F. Supp. 807 (N.D. Miss. 1984)

(three-judge court), aff’d sub nom., Miss.

Republican Executive Comm. v. Brooks, 469

U.S. 1002 (1984).........................................25, 26

Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398 (7th Cir. 1984) ....29

Larios v. Cox, 300 F. Supp. 2d 1320 (N.D. Ga. 2004)

(three-judge court), aff’d, 542 U.S. 947 (2004)

...................................................................... 11, 14

League of United Latin Am. Citizens (“LULAC”) v.

Perry, 548 U.S. 399 (2006)......................passim

iii

Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, 138 S. Ct. 1945

(2018)................................................................ 14

McCreary Cnty. v. Am. Civil Liberties Union ofKy.,

545 U.S. 844 (2005)............................. 12, 17, 19

McMillan v. Escambia Cnty., Fla., 748 F.2d 1037

(11th Cir. 1984)................................................30

N.C. State Conference of NAACP v. McCrory, 831

F.3d 204 (4th Cir. 2016), cert, denied, 137 S.

Ct. 1399 (2017).................................................. 29

One Wis. Institute, Inc. v. Thomsen, 198 F. Supp. 3d

896 (W.D. Wis. 2016), appeal docketed, No. 16-

3091 (7th Cir. Aug. 3, 2016)............................. 29

Perez v. Abbott, 253 F. Supp. 3d 864 (W.D. Tex. 2017)

(three-judge court).............................. 27, 30, 31

Personnel Adm’r of Mass. v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

(1979).............................................. 10, 13, 15, 17

Raleigh Wake Citizens Ass’n v. Wake Cnty. Bd. of

Elections, 827 F.3d 333 (4th Cir. 2016).... 11, 13

Rodgers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)....................... 24

Shapiro v. McManus, 203 F. Supp. 3d 579 (D. Md.

2016) (three-judge court)................................... 6

Shelby Cnty. v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013)...... 20, 24

Smith v. Clinton, 687 F.Supp. 1310 (E.D. Ark. 1988)

(three-judge court)............................................22

IV

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30

(1986).............................................. 20, 21, 23, 28

United States v. Charleston Cnty., 365 F.3d 341 (4th

Cir. 2004)...........................................................30

Veasey v. Abbott, 830 F.3d 216 (5th Cir. 2016) (en

banc), cert, denied, 137 S. Ct. 612 (2017)...... 29

Vieth v. Jubelirer, 541 U.S. 267 (2004)...................3, 8

Vill. of Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hous. Dev’p Corp.,

429 U.S. 252 (1977)............................... 7, 12, 13

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)................24, 25

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973).......................... 9

Whitford v. Gill, 218 F. Supp. 3d 837 (W.D. Wis.

2016) (three-judge court), vacated on other

grounds, 138 S. Ct. 1916 (2018).....................12

Federal Statutes and Legislative Materials

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982)........... 20

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 52 U.S.C. § 10301 et seq.

.....................................................................................................................20, 21

State Constitutions

Fla. Const, art. Ill, § 16(c)........................................11

v

State Cases

In re Senate Joint Resolution of Legislative

Apportionment 1176, 83 So.3d 597 (Fla. 2012)

........................................................................... 11

In re Senate Joint Resolution of Legislative

Apportionment 2-B, 89 So.3d 872 (Fla. 2012)

........................................................................... 11

League of Women Voters of Fla. v. Detzner, 172 So. 3d

363 (Fla. 2015)............................................11, 13

League of Women Voters of Fla. v. Detzner, 179 So. 3d

258 (Fla. 2015)....................................................11

League of Women Voters of Pa. v. Pennsylvania, 178

A.3d 737 (Pa. 2018)............................................ 11

Other Authorities

Bruce E. Cain & Emily R. Zhang, Blurred Lines:

Conjoined Polarization and Voting Rights, 77

OHIO St. L.J. 867 (2016)..................................31

Art Harris, Blacks, Unlikely Allies Battle Miss.

Redistricting, Wash. Post, June 1, 1982....... 26

Samuel Issacharoff, Gerrymandering and Political

Cartels, 116 Harv. L. Rev. 593 (2002).......... 31

Samuel Issacharoff & Pamela S. Karlan, Where to

Draw the Line?: Judicial Review of Political

Gerrymanders, 153 U. PA. L. Rev. 541 (2004) 32

vi

Elena Kagan, Private Speech, Public Purpose: The

Role of Governmental Motive in First

Amendment Doctrine, 63 U. Cffl. L. Rev. 413

(1996)...........................................................10, 18

Michael S. Kang, Gerrymandering and the

Constitutional Norm Against Government

Partisanship, 116 MlCH. L. Rev. 351 (2017).. 10

Justin Levitt, Intent is Enough: Invidious

Partisanship in Redistricting, 59 Wm. & MARY

L. REV. 1993 (2018)........................................8, 9

vii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE1

Amici, listed individually in the Appendix to

this brief, are among the country’s leading civil rights

organizations. They have a significant interest in

ensuring the full, proper, and continued enforcement

of the United States Constitution and the federal,

state, and local statutes guaranteeing full and equal

political participation, including the Voting Rights

Act of 1965.

INTRODUCTION AND

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

“[E]lected officials engaged in the single-

minded pursuit of incumbency can run roughshod

over the rights of protected minorities.” Garza u.

Cnty. of Los Angeles, 918 F.2d 763, 778 (9th Cir. 1990)

(Kozinski, J., concurring and dissenting in part). The

same is true with respect to the pursuit of partisan

advantage. Both Democratic and Republican

legislatures have used the power of the state to enact

extreme partisan gerrymanders, retaining or

enhancing their own grip on power and methodically

subordinating voters who support an opposing party.

1 Pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 37.3, counsel for amici curiae

certify that all parties have consented to the filing of this brief

through letters from the parties on file with the Court. Pursuant

to Supreme Court Rule 37.6, counsel for amici curiae certify that

no counsel for a party authored this brief, in whole or in part, and

that no person or entity, other than amici curiae and their

counsel, made a monetary contribution to its preparation or

submission.

1

Minority communities have often been pawns

deployed or sacrificed in the pursuit of this partisan

entrenchment.

There is no active claim that the maps

presently before the Court built their partisan

advantage on the backs of minority voters. But the

North Carolina plan at issue here is the successor to

a map that impermissibly packed minority voters to

achieve similar partisan gains, Cooper v. Harris, 137

S. Ct. 1455 (2017); Rucho J.S. App. 155, 180-81.

Jurisdictions in both Maryland and North Carolina—

among many others—have in the past used racial

discrimination, provable and less provable, as a tool to

achieve partisan ends. If the Court withdraws the

judiciary from policing the boundaries of partisan

excess manifested by the record in these cases, brazen

partisan misconduct will follow here and in other

jurisdictions with unified partisan control of the

redistricting process. History teaches that minority

voters will inevitably be caught again in the crossfire.

Amici hope to assist this Court in considering

the ramifications of the doctrine and practice of

partisan gerrymandering on minority voters. In

particular, as amici explain, a partisan

gerrymandering claim requiring proof of invidious

intent—driven by the desire to subordinate some

voters based on their party affiliation and the desire

to entrench an opposing party in power—will help to

establish an administrable standard that guards

against excessive partisanship in the redistricting

process without undermining critical protections for

minority voters.

2

When this Court as a whole last meaningfully

considered the merits of a cause of action for partisan

gerrymandering, all nine Justices recognized that “an

excessive injection of politics” in the redistricting

process is incompatible with the Constitution. See

Vieth v. Jubelirer, 541 U.S. 267, 293 (2004) (plurality);

id. at 312, 316-17 (Kennedy, J., concurring in the

judgment); id. at 318, 326 (Stevens, J., dissenting); id.

at 343-44 (Souter, J., and Ginsburg, J., dissenting); id.

at 355, 360 (Breyer, J., dissenting). No consensus

emerged, however, with respect to identifying when

the role of politics in redistricting becomes excessive.

As Appellees make clear, such standards exist,

and can be fully compatible with federal law

protecting minority representation and political

participation. This Court should establish a standard

for adjudicating claims of partisan gerrymandering

that ensures that such claims succeed only when

plaintiffs prove invidious discrimination distinct from

legitimate political choices. In the instant cases, each

three-judge court found that the political party

controlling state government intended to lock in

partisan dominance of the state’s congressional

delegation, not through the persuasive force of its

policies, but by manipulating district lines to entrench

the power of certain voters and subordinate others

based on their partisan political affiliation. See Rucho

J.S. App. 155, 222, 286-88, 306; Benisek J.S. App. 12a,

16a, 23a-24a, 48a, 51a. Indeed, in each case at issue

here, the intent to use government authority to

subordinate opposition voters on the basis of their

political affiliation was plain—and at times, both

public and proud. See Rucho J.S. App. 156-57, 185;

Benisek J.S. App. 23a-24a. It is entirely consistent

3

with the Court’s prior jurisprudence to find that such

extreme conduct entails impermissible

discrimination, and requires no more than the

deployment of familiar evidentiary tools. And as the

Court’s experience already demonstrates, such a

holding would not likely subject federal courts to a

flood of insubstantial claims.

Indeed, a viable cause of action addressing

egregious partisan gerrymandering may assist the

courts. Causes of action in which race and racial

discrimination are central to the legal doctrine are

essential in addressing some of the deepest and most

pernicious forms of discrimination. That includes

legislation abusing race as a proxy for party, or

otherwise targeting minorities for disfavored

treatment based on other underlying motives,

including the pursuit of partisan gain. But when both

race and party play a role in legislators’ pursuit of

impermissible advantage, real partisan harms may

accompany very real racial harms; in these instances,

a claim to root out unconstitutional partisan excesses,

alongside doctrine tailored to address racial

discrimination, would ensure the presence of a

distinct, properly tailored tool to address each distinct

injury. And at times, we have also observed that

litigants whose primary concerns are partisan will

occasionally attempt to misuse unwarranted race-

based voting claims for their own ends. A properly

structured cause of action for partisan

gerrymandering can help courts better distinguish

and channel claims down the appropriate litigation

paths, avoiding unwelcome doctrinal distortion and

providing full redress for invidious discrimination of

all forms.

4

ARGUMENT

A. A Cause of Action for Partisan

Gerrymandering Is Justiciable and

Requires Proof of Invidious

Discrimination Against Voters Based on

Their Political Party Affiliation

This Court has previously determined claims of

unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering to be

justiciable. See, e.g., League of United Latin Am.

Citizens (“LULAC”) v. Perry, 548 U.S. 399, 414 (2006);

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109, 125 (1986).

Among the questions presented in this case,

however, are issues concerning the particular

standard or standards for adjudicating claims of

partisan gerrymandering under various

constitutional theories. Each three-judge court

correctly determined that invidious intent was an

essential element of such a standard no matter the

constitutional clause involved, and found facts

supporting proof of invidious intent. Rucho J.S. App.

141-42, 155-87, 227-74, 280-88, 305-13; Benisek J.S.

App. 42a-43a, 51a, 59a, 61a, 76a n.3. A justiciable

standard for claims that partisan gerrymandering

violates the Constitution—drawn from any of several

textual predicates, and whatever its other elements—

ought to require proof of invidious intent to

subordinate voters, driven by a focus on their partisan

affiliation and with the goal of entrenching an

opposing political party’s power. And this Court need

not determine the outer bounds of such a requirement

to recognize that neither three-judge court clearly

erred in finding the record in these cases sufficient to

support a finding of constitutionally invidious action.

5

Requiring proof of this sort of invidious intent

to subordinate is consistent with this Court’s doctrine.

In Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973), this

Court found no constitutional concern with a plan

intended to allocate political power to parties in

accordance with each party’s voting strength. But the

Court also noted that an otherwise acceptable

redistricting plan would be vulnerable under the

Fourteenth Amendment if it is invidiously

discriminatory: intended to “minimize or cancel out

the voting strength of racial or political elements of

the voting population.” Id. at 751 (internal quotation

marks and citations omitted) (emphasis added).

This Court has also clearly held that the First

Amendment prohibits the government from deploying

state power with an invidious intent to harm on the

basis of partisan affiliation. A public employer may

demote an employee for many reasons that do not

offend the Constitution. But the First Amendment

normally prevents a public employer from demoting

an employee out of a desire to punish the employee’s

support for a political candidate. See Heffernan v. City

of Paterson, 136 S. Ct. 1412, 1417-18 (2016). That is,

“the government’s reason for demoting [the employee]

is what counts here.” Id. at 1418. See also Shapiro v.

McManus, 203 F. Supp. 3d 579, 596 (D. Md. 2016)

(three-judge court) (“Because there is no redistricting

exception to this well-established First Amendment

jurisprudence, the fundamental principle that the

government may not penalize citizens because of how

they have exercised their First Amendment rights

thus provides a well-understood structure for claims

challenging the constitutionality of a State’s

6

redistricting legislation—a discernable and

manageable standard.”).

The manifestation of invidious intent also

played a central role in last year’s oral argument in

Gill v. Whitford. Justice Kennedy repeatedly asked

whether a law facially proclaiming the use of all

legitimate redistricting factors to favor one party (and

disfavor another) would be constitutional—a

hypothetical Justice Alito described as incorporating

a “perfectly manageable standard.” See Transcript of

Oral Argument at 19-20, 26-27, Gill v. Whitford, 138

S. Ct. 1916 (2018) (No. 16-1161). The question sets

aside methods of proof, and highlights instead the

legal crux of the matter: a driving insistence on using

state authority to entrench the political power of a

group of voters favored based on their partisan

preferences, and to similarly subordinate a group

singled out as disfavored based on different partisan

preferences. The attorney representing Wisconsin’s

legislature correctly acknowledged that such a statute

would violate both the Equal Protection Clause and

the First Amendment. Id. at 27; see also Transcript of

Oral Argument at 46-47, Benisek v. Lamone, 138 S.

Ct. 1942 (2018) (No. 17-333) (revealing Justice

Kennedy’s return to the same question, with a similar

answer).

To be sure, the evidence of unconstitutional

conduct will not always be as clear as in Justice

Kennedy’s hypothetical. Some violations will be

plainly marked and some will be perpetrated under

pretext, to be smoked out via familiar judicial tools,

cf., e.g., Vill. of Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hous.

Dev’p Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977). The fact that

7

some plaintiffs will fail to muster the necessary

evidence to prevail is not reason to deny the existence

of a cause of action. Justice Kennedy’s questions

reveal that there is a fundamental and widely

acknowledged harm at the heart of these cases.

A gerrymandering cause of action that requires

proof of invidious intent to subordinate voters driven

by a desire to harm them for their partisan affiliation

does not risk undue interference with the legitimate

political process. As this Court has recognized,

redistricting is “root-and-branch a matter of politics.”

Vieth, 541 U.S. at 285 (plurality); see also Gaffney, 412

U.S. at 752-73. But this does not mean that

redistricting is, or need be, root-and-branch an

attempt to subordinate voters on the basis of their

political affiliation. There is a distinction between

proper political contestation and improper partisan

subordination of voters because of their preferred

group affiliation. The vast majority of legislation

involves choices that are inherently political—for

example, how much revenue to allocate to different

government programs, or what should be eligible for

tax deductions. These are charged political questions

that present opportunities for partisan posturing, but

they do not necessarily involve a conscious effort to

subordinate voters because they are Republicans or

Democrats. See Justin Levitt, Intent is Enough:

Invidious Partisanship in Redistricting, 59 Wm . &

MaryL. Rev. 1993, 2013-18 (2018).

Beyond the requirements of federal and state

law, including those that protect minority voters from

discrimination, there are many political and practical

choices in the drawing of any redistricting map. In

8

most states, these include choices about whether to

follow certain county, city, or precinct lines but not

others, or certain roads, rivers, or rail lines but not

others; about the degree to which lines should follow

geometric patterns or patterns of residential

development; about allowing certain communities to

congregate within one district or to span district lines;

and about the degree to which a district should have

a distinct character or span multiple competing

interests, and which of those interests should

dominate. They include choices about whether to

protect the relationship of incumbents to their

constituents, by consistently maintaining the cores of

prior districts (as distinct from selectively protecting

incumbents from their constituents by siphoning off

opposing partisans). See LULAC, 548 U.S. at 440-41;

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783, 791 (1973). They

include choices about whether to resolve each of these

decisions in the same way throughout a jurisdiction,

or whether to resolve them differently, with different

priorities, in different portions of the jurisdiction. All

of these may properly be political and practical

choices. Prohibiting state action driven by the

invidious intent to subordinate on the basis of

partisan affiliation leaves each of these legitimate

political choices intact. See Levitt, supra, at 2025-27.

A state actor’s invidious intent to methodically

subordinate voters on the basis of their partisan

affiliation is also distinct from the natural desire of

legislators chosen in partisan elections to seek

legitimate partisan advantage. The appropriate

means by which a legislator gains partisan advantage

is through policy action that increases the legislator’s

appeal to voters with partisan policy preferences.

9

Such conduct is quite distinct from state action driven

by a design to lock in a legislator’s electoral success

not by appealing to voters, but by targeting presumed

opposing voters for systematic subordination through

changes to the electoral landscape itself. Cf. Elena

Kagan, Private Speech, Public Purpose: The Role of

Governmental Motive in First Amendment Doctrine,

63 U. CHI. L. Rev. 413, 428-29 (1996) (recognizing

constitutional limits on government restrictions of

speech because that speech may threaten incumbent

self-interest).

Finally, focusing on the invidious intent to

subordinate does not demand a process blind to

partisan inputs or partisan outcomes. Neither a

legislator’s knowledge that certain communities are

more likely to vote for Democratic or Republican

candidates, nor that given districts are more likely to

lean Democratic or Republican, is itself indicative of

the intent to entrench power at opponents’ expense.

Michael S. Kang, Gerrymandering and the

Constitutional Norm Against Government

Partisanship, 116 MlCH. L. Rev. 351, 352, 368 (2017);

cf. Personnel Adm’r of Mass. v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256,

279 (1979). And this Court has long recognized the

proper distinction between a legislature’s permissible

consideration of community characteristics and the

impermissible intent to subordinate community

voting power because of those characteristics. See

LULAC, 548 U.S. at 513-14 (Scalia, J., concurring in

the judgment in part and dissenting in part).

Both state and federal courts have been able to

identify legally cognizable invidious intent, distinct

from the standard rough-and-tumble of other political

10

choices. In Larios v. Cox, a three-judge court

determined that population disparities that would not

otherwise have raised prima facie constitutional

concern were constitutionally invalid because they

were driven by invidious partisan intent to

subordinate. 300 F. Supp. 2d 1320, 1329-30, 1334

(N.D. Ga. 2004) (three-judge court). This Court

summarily affirmed that decision. 542 U.S. 947

(2004). Similarly, the Fourth Circuit recently

invalidated a county redistricting plan that would

otherwise have passed muster, based on proof that the

districts’ population deviations were driven by the

invidious partisan intent of the North Carolina state

legislature. Raleigh Wake Citizens Ass’n v. Wake

Cnty. Bd. of Elections, 827 F.3d 333, 345-46, 351 (4th

Cir. 2016); see also City of Greensboro v. Guilford

Cnty. Bd. of Elections, 251 F. Supp. 3d 935, 937, 939,

943 (M.D.N.C. 2017) (North Carolina state

legislature); Hulme v. Madison Cnty., 188 F. Supp. 2d

1041, 1050 (S.D. 111. 2001) (Madison County, Illinois,

county board). Florida and Pennsylvania state courts

have also examined redistricting plans for invidious

partisan intent under their respective state

constitutions. See Fla. CONST, art. Ill, § 16(c); In re

Senate Joint Resolution of Legislative Apportionment

1176, 83 So.3d 597, 598, 617-19, 641-45, 648-51, 654,

659-62, 669-73, 676-78, 679-80 (Fla. 2012); In re

Senate Joint Resolution of Legislative Apportionment

2-B, 89 So.3d 872, 881-82, 887-91 (Fla. 2012); League

of Women Voters of Fla. v. Detzner, 172 So.3d 363, 378-

86, 391-93, 402-13 (Fla. 2015); League of Women

Voters of Fla. v. Detzner, 179 So.3d 258, 271-74,

279-80, 284 (Fla. 2015); League of Women

Voters of Pa. v. Pennsylvania, 178 A.3d 737, 817-21

(Pa. 2018). And, of course, the three-judge courts in

11

the instant actions were able to distinguish invidious

partisan intent to subordinate from the many other

legitimate political and practical choices involved in

drawing the particular districts at issue. Rucho J.S.

App. 155-87, 227-74; Benisek J.S. App. 55a-56a; see

also Whitford u. Gill, 218 F. Supp. 3d 837, 883-98

(W.D. Wis. 2016) (three-judge court), vacated on other

grounds, 138 S. Ct. 1916 (2018) (Wisconsin state

legislative map).

In other cases, the evidence has not supported

the allegations of invidious unconstitutional action in

the redistricting process. For instance, this Court

affirmed the rejection of a claim premised on invidious

partisanship in the redistricting process, based not on

the impossibility of making such a determination, but

on the insufficiency of proof offered by the plaintiffs.

Harris v. Ariz. Ind. Redistricting Comm’n, 136 S. Ct.

1301, 1307 (2016). And in the instant North Carolina

case, the three-judge court rejected a district-specific

showing of invidious intent with respect to District 5.

Rucho J.S. App. 243.

All of these courts used familiar tools to test for

invidious partisan intent in the redistricting process,

seeking “an understanding of official objective

emerging] from readily discoverable fact, without any

judicial psychoanalysis of a drafter’s heart of hearts.”

McCreary Cnty. v. Am. Civil Liberties Union of Ky.,

545 U.S. 844, 862 (2005). Following this Court’s

direction for assessing official purpose in a variety of

contexts, each tribunal conducted a “sensitive inquiry

into such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent

as may be available.” Vill. of Arlington Heights, 429

U.S. at 266. Particularly when a redistricting plan

12

proved to be a significant outlier, its excessive

partisan impact occasionally provided “an important

starting point,” Feeney, 442 U.S. at 279 (quoting Vill.

of Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266), for such an

analysis. However, recognizing that legitimate

redistricting factors will inevitably yield a partisan

impact, no court relied on an assessment of impact

alone. Instead, these courts further examined the

redistricting context, including but not limited to:

statements by mapmakers themselves, the conduct of

the legislative session, the progression of draft maps

up to the final product, and the map’s fit with

traditional redistricting principles. See Raleigh Wake

Citizens Ass’n, 827 F.3d at 346; City of Greensboro,

251 F. Supp. 3d at 943-49; League of Women Voters of

Fla., 172 So.3d at 380-86, 390-91; Hulme, 188 F. Supp.

2d at 1050-51. Moreover, these courts also considered

whether this evidence of invidious intent was

effectively rebutted by evidence revealing that the

district boundaries were, in fact, materially driven not

by invidious partisan intent to subordinate but by

legitimate legislative motives. Id.

Courts do not lightly make such

determinations. Nor do plaintiffs lightly bring such

cases. Appellants suggest—as defendants in such

circumstances often do—that once the judicial doors

are opened they will be torn off in a flood of frivolous

litigation. Rucho App. Br. 39. Experience indicates

otherwise. Since at least 2004, federal courts have

been available to hear claims that invidious

partisanship impermissibly motivated minor

variations in district population. Since 2004, there

have been thousands of state and local legislative

maps, pre-existing and newly drawn, with a minor

13

population variance. But Larios has been cited only

seven times by federal appellate courts substantively

reviewing allegations of improper political motivation

in the redistricting process.

Still, even if the marginal case posed concerns,

the records here stand far from the marginal case.

Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, 138 S. Ct. 1945

(2018), just last Term, may provide an apt analogy.

Lozman concerned the arrest of a civic gadfly at a city

council meeting, allegedly pursuant to a premeditated

city policy to intimidate him in retaliation for his

activism. Id. at 1954. The legality of the arrest

turned on proof of impermissible motive, and the court

expressly noted the “risk that the courts will be

flooded with dubious retaliatory arrest suits.” Id. at

1953. But in the face of objective evidence of a

potentially premeditated plan, this Court decided the

case before it and left the floodgate concerns for the

future. Id. at 1954. “[Wjhen retaliation against

protected speech is elevated to the level of official

policy, there is a compelling need for adequate

avenues of redress.” Id.

There will likely be no official policy to

subordinate voters on the basis of partisan affiliation

clearer than the policy firmly established here — and

openly acknowledged by the governing political

parties in North Carolina and Maryland. Each three-

judge court found that plaintiffs proved not merely

that the legislature had partisan information or was

aware of a partisan impact, but that it drew the map

in question specifically “because o f’ its ability to

entrench one party in power and subordinate voters

affiliated with an opposing party. Rucho J.S. App.

14

155; Benisek J.S. App. 48a-51a; see also Feeney, 442

U.S. at 279. In North Carolina, this purpose was

officially declared in the formal criteria established by

the state, and proudly promoted in the public hearings

of the legislature’s redistricting committee. Rucho

J.S. App. 156-57, 183. The public record established

by the North Carolina legislature is, in effect, Justice

Kennedy’s hypothetical question from the oral

arguments in Gill and Benisek come to life. Likewise,

in Maryland, legislators acknowledged in talking

points and floor speeches their drive to accomplish

similar partisan entrenchment with respect to the

district at issue. Benisek J.S. App. 23a-24a.

The three-judge courts also found that in each

state, the mapmakers’ intent was clear not only from

express statements, but also from other familiar

evidentiary sources—such as the redistricting process

itself, the information relied upon in drawing the map,

and empirical evidence of the strong partisan

advantage present in the final maps approved by the

legislatures. In North Carolina, the Republican Party

held exclusive control of the map drawing process,

working with a consultant to finalize the map before

the bipartisan redistricting committee had even met

or adopted governing redistricting criteria and before

public hearings were held. Rucho J.S. App. 156. No

public input was considered as a part of the map

drawing process; however, mapmakers relied strongly

on past election results in their analysis to develop a

map that “would favor Republicans for the remainder

of the decade.” Id. at 158. Indeed, in a 50-50 state,

the map was designed to elect 10 Republicans and 3

Democrats, only because (as the legislative leadership

bragged) they did “not believe it[ would be] possible to

15

draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats,”

id. at 183—and the map achieved its primary goal in

a manner that left it an “extreme statistical outlier,”

id. at 159-172.

Likewise, in Maryland, the court found that

“with respect to the mapmakers’ intent, the process

described in the record admits of no doubt.” Benisek

J.S. App. 48a. Although the Redistricting Advisory

Committee held public hearings and was ostensibly

tasked with recommending a map, privately,

Democratic representatives retained a consulting firm

to draw proposed maps with the exclusive goals of

maximizing Democratic incumbent protection and

enlarging Democratic congressional power. Id. at 14a.

Maryland Democratic officials were guided by “a

narrow focus on diluting the votes of Republicans.” Id.

at 48a. Accordingly, the mapmakers relied on a

custom-tailored partisan index to ensure that a

generic Democratic candidate would win the Sixth

District, and rejected alternative maps that placed the

outcome in greater doubt. Id. at 15a-17a. As a result,

according to analysis by the Cook Political Report, as

compared to the preexisting map, under the new

redistricting plan, the Sixth District “experienced the

single largest [partisan] swing of any district in the

Nation.” Id. at 24a-25a. The map was approved by

the Advisory Committee and subsequently, the

General Assembly, both without a single Republican

vote. Id. at 20a, 23a.

Amici recognize that neither the North

Carolina and Maryland legislatures’ partisan

excesses nor their candor may presently or in the

future reflect the norm. Absent this Court’s

16

affirmation of the three-judge courts’ decisions,

however, it is difficult to understand why they would

not become the new status quo, demonstrating to

citizens that expressions of political affiliation are not

constitutionally protected but available grounds for

punishment by the state. Surely, this Court is capable

of policing the worst excesses of partisan

discrimination to preserve the ability of voters to

express their political views through the ballot box

without fear of reprisals from the governing political

party.

Indeed, intervention here is vital even if it

yields malfeasance less explicit in the future. (If less

explicit malfeasance is likely to also be a bit less

excessive, that would be a welcome consequence on its

own.) Invidious intent cannot be assumed, see Feeney,

442 U.S. at 278-79, but must instead be proven. The

standard is a demanding one, and necessarily means

that a doctrinal requirement to prove the invidious

intent to subordinate voters based on their partisan

preference will inevitably leave some invidious

partisanship unaddressed. Cf. McCreary Cnty., 545

U.S. at 863 (recognizing that some legitimate intent

cases may founder on the absence of proof). That

litigation reality, however, does not detract from the

value of the ability to confront and correct invidious

discrimination that can be proven, including that

which is open and notorious on its face. Cf. Batson v.

Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 102, 105-08 (1986) (Marshall,

J., concurring) (endorsing doctrine to confront racially

discriminatory peremptory challenges, while

acknowledging that illegitimate peremptory

challenges beyond the doctrine’s reach are inevitable).

17

Even though a doctrinal requirement to prove

invidious partisan intent leaves some invidious

partisanship unaddressed, the requirement is

necessary to a manageable constitutional claim. See,

e.g., Bandemer, 478 U.S. at 127; Kagan, supra, at 509-

11. Consistent with this premise, no party in the

instant cases has requested, no three-judge court has

proposed, and this Court should not adopt, any single

quantitative metric as irrebuttable proof of an

unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. This brief

takes no position on the comparative merits or

limitations of any particular quantitative measure in

providing evidence of constitutional irregularity, or

even whether such measures, however helpful in

other cases, are necessary given the records at hand.

Modest “scores” using any of these measures may flag

plans produced by legislatures heeding only

traditional redistricting principles without improper

motivation, and therefore constitutionally

unremarkable. Extreme “scores,” on any of several of

these quantitative measures, may indicate partisan

results sufficiently anomalous to constitute, inter alia,

circumstantial evidence of invidious partisan intent to

subordinate. But as the three-judge courts in these

cases emphasized, a jurisdiction should always have

the opportunity to demonstrate that even an extreme

quantitative score was actually caused by legislative

focus on constitutionally legitimate factors, including

18

traditional redistricting principles.2 See, e.g., Rucho

J.S. App. 215-22; Benisek J.S. App. 41a-43a.

B. A Properly Structured Claim for Partisan

Gerrymandering Is Consistent with the

Voting Rights Act

A properly structured partisan

gerrymandering claim—one that requires proof of

invidious intent to subordinate voters driven by their

partisan affiliation—is entirely consistent with the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 (“VRA”). Of course,

compliance with the VRA does not insulate an

unconstitutional partisan gerrymander from judicial

scrutiny. Legislatures might produce maps that

comply with the VRA along the way to implementing

an unlawful plan premised on invidious partisan

intent, just as legislatures might produce plans that

are fair along partisan lines even as they violate the

VRA (or Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments) by

discriminating based on race. Neither is lawful. But

compliance with the VRA and the absence of invidious

2 As this Court recently emphasized in a different redistricting

context, this inquiry into legislative intent turns on “the actual

considerations that provided the essential basis for the lines

drawn, not post hoc justifications the legislature in theory could

have used but in reality did not.” Bethune-Hill v. Va. State Bd.

of Elections, 137 S. Ct. 788, 799 (2017); cf. McCreary Cnty., 545

U.S. at 864 (refusing to credit a hypothetically permissible

purpose that is merely a sham). Particularly in the arena of

invidious discrimination, jurisdictions should not be permitted to

rescue actual manifestations of unlawful intent to subordinate

with hypothetical interests invented for litigation purposes.

19

partisan intent are not in any way inherently in

conflict.

Section 2 of the VRA, 52 U.S.C. § 10301,

imposes a “permanent, nationwide ban on racial

discrimination in voting.” Shelby Cnty. u. Holder, 570

U.S. 529, 557 (2013). It prohibits any “voting

qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard,

practice, or procedure” that “results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United

States to vote on account of race or color.” Id.

§ 10301(a).

In 1982, Congress amended Section 2 to make

clear that a statutory violation can be established by

showing discriminatory intent, a discriminatory

result, or both. See Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30,

34-37, 43-45 (1986); see also 52 U.S.C. § 10301(a)-(b);

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982). In the

redistricting context, a jurisdiction may comply with

the prohibition on discriminatory intent by drawing

district lines without the intent to harm voters based

on their race or ethnicity. It is obvious that a

jurisdiction can satisfy this standard without drawing

lines intended to subordinate voters on the basis of

their partisan political affiliation.

Similarly, a jurisdiction may comply with the

VRA’s prohibition on discriminatory results without

setting out to subordinate voters on the basis of their

political affiliation. Based on local demographic,

historical, and political contexts, jurisdictions may

have an obligation under Section 2 to draw districts

preserving minority voters’ equal “opportunity . . . to

elect representatives of their choice.” 52 U.S.C.

§ 10301(b). Where a compact and sizable minority

20

community is politically cohesive, and where voting is

sufficiently polarized that the surrounding electorate

would otherwise usually prevent the minority

community from electing a candidate of choice,

jurisdictions have an obligation to ensure that

districts, in the totality of circumstances, do not create

a discriminatory abridgement of electoral

opportunity. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 44-45, 50-51.

Compliance with Section 2 of the VRA will thus

often require attention to, inter alia, the voting and

electoral patterns in a local community. Id. at 45

(recognizing that “whether the political processes are

equally open depends upon a searching practical

evaluation of the past and present reality and on a

functional view of the political process”); id. at 79

(noting that this determination “requires an intensely

local appraisal of the design and impact of the

contested electoral mechanisms”); see also Goosby v.

Town of Hempstead, 956 F. Supp. 326, 331 (E.D.N.Y.

1997) (using a myriad of factors identified by a

bipartisan Congress, “district judges are expected to

roll up their sleeves and examine all aspects of the

past and present political environment in which the

challenged electoral practice is used”).

The VRA does not, however, require districts

drawn with the intent to entrench or subordinate

Democrats, Republicans, or members of any other

political party. And a district that is drawn favoring

Democrats or favoring Republicans but that does not

provide a minority community the equitable

“opportunity . . . to elect representatives of their

choice,” 52 U.S.C. § 10301(b), fails to satisfy the

jurisdiction’s VRA obligations. The VRA is rigorously

21

focused on the distinct preferences of minority

communities facing discrimination, not on generic

partisan results. Cf., e.g., Clarke v. City of Cincinnati,

40 F.3d 807, 812 (6th Cir. 1994) (“[T]he Act’s

guarantee of equal opportunity is not met when, in the

words of Judge Richard Arnold, ‘ [candidates favored

by blacks can win, but only if the candidates are

white.’”) (quoting Smith v. Clinton, 687 F.Supp. 1310,

1318 (E.D. Ark. 1988) (three-judge court)).

This means that while the VRA requires

attention to local voting patterns, it does not require

districts drawn for voters because of their partisan

affiliation. A fortiori, it in no way requires an

invidious intent to subordinate voters based on their

partisan affiliation. Indeed, many courts, including

this Court, have required jurisdictions to comply with

their obligations under the VRA, without ever

intimating that doing so would require invidious

partisan intent. And just recently, in a case involving

population disparities, this Court unanimously

affirmed the rejection of a claim of invidious partisan

intent when the facts instead supported the

conclusion that the disparities were driven by good-

faith efforts to comply with the VRA. Harris, 136 S.

Ct. at 1309-10. That is, this Court recognized that

legitimate VRA compliance did not—and does not—

produce unconstitutionally invidious partisanship.

Beyond the VRA, other legitimate redistricting

considerations, including traditional redistricting

principles, may similarly further the concerns of

minority voters without running afoul of a properly

structured partisan gerrymandering claim. For

example, in some circumstances, the political

22

interests of minority voters may be served by efforts

to keep that community of interest intact within a

district, even where there is no federal mandate to do

so. Keeping that community intact raises no inference

that a legislature intends to subordinate voters based

on their partisan affiliation.

Similarly, in some circumstances, the political

interests of minority voters may be served by

preserving the core of an existing district, and hence

the relationship of a population with a longstanding

incumbent. Doing so raises no inference that a

legislature intends to subordinate voters based on

their partisan affiliation. A robust requirement of

invidious intent ensures that legitimate compliance

with traditional redistricting principles, including

those that advance the interests of minority voters, is

not inadvertently conflated with illegitimate

partisanship.

C. A Properly Structured Claim for Partisan

Gerrymandering Will Help Avoid

Detrimental Distortion in Cases Brought

Under Doctrines Involving Race

Cases involving claims of racial discrimination

under the VRA and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments play an essential role in remedying the

deepest and most pernicious forms of discrimination

in voting. See, e.g., LULAC, 548 U.S. at 438-42

(finding vote dilution in violation of Section 2 of the

VRA with respect to Congressional District 23 in

Texas); Gingles, 478 U.S. at 34, 80 (finding vote

dilution in violation of Section 2 of the VRA with

respect to state legislative districts in North

23

Carolina); Rodgers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)

(finding vote dilution in violation of Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments with respect to county

commission in Georgia); White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755, 765-70 (1973) (finding vote dilution in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment with respect to state

house districts in Texas); cf. Covington v. North

Carolina, 316 F.R.D. 117, 124 (M.D.N.C. 2016) (three-

judge court) (finding unconstitutional racial

gerrymander with respect to state legislative districts

in North Carolina), aff’d, 137 S. Ct. 2211 (2017).

No doubt they will continue to do so. As this

Court has recognized, “racial discrimination and

racially polarized voting are not ancient history,” and

“[m]uch remains to be done to ensure that citizens of

all races have equal opportunity to share and

participate in our democratic processes and

traditions.” Bartlett v. Strickland, 556 U.S. 1, 25

(2009) (plurality); see also Shelby Cnty., 570 U.S. at

536 (“[Vjoting discrimination still exists; no one

doubts that.”).

Racial discrimination, of course, is morally,

historically, and legally distinct from partisan

subordination. Partisan impulses have, however,

repeatedly provided disturbing incentives for officials

of both major parties to draw districts that

disadvantage minority voters. The absence of a

meaningful partisan gerrymandering doctrine has not

only fostered this abuse, but also led to further

detrimental impacts for voters and for the law.

Jurisdictions in race-based redistricting cases have

inappropriately and sometimes successfully claimed

invidious partisan purpose as a defense. And

24

claimants with partisan motives may bring

inappropriate race-based cases that distort the

jurisprudence of racial harm. The distinct harms of

partisan and racial discrimination in redistricting

merit two distinct causes of action, for the benefit of

the law and the courts, and voters of all kinds.

History shows that in the absence of a firm

understanding of the illegality of invidious partisan

gerrymandering, both major political parties—

Democratic and Republican—have drawn electoral

districts in pursuit of their excessive partisan

interests in ways that have harmed minority voters.

Following the 1970 Census, for example, Texas

Democrats drew multimember districts in Dallas and

Bexar counties that were “unconstitutional in that

they dilute the votes of racial minorities.” Graves v.

Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704, 708-709, 724-34 (W.D. Tex.

1972) (three-judge court). A three-judge district court

did not reach the partisan gerrymandering claim

brought by Republican voters and officials because the

claim of racial vote dilution delivered the requested

relief. Id. at 735. This Court unanimously affirmed

that finding of unconstitutional vote dilution.

Regester, 412 U.S. at 765-70.

Similarly, in Mississippi, following the 1980

Census, Black voters challenged the state’s

congressional redistricting plan, drawn by Democrats,

which “divided the concentration of black majority

counties located in the northwest or 'Delta’ portion of

the state among three districts.” Jordan v. Winter,

604 F. Supp. 807, 809 (N.D. Miss. 1984) (three-judge

court), aff’d sub nom., Miss. Republican Executive

Comm. v. Brooks, 469 U.S. 1002 (1984). The districts

25

were drawn to protect three incumbent Democrats

from Republican challengers (and thus maintain the

Democrats’ control of the state’s congressional

delegation), and Republican officials in Mississippi

“lobb[ied] the Justice Department on behalf of

Mississippi black[ voters] and Republicans to reject

the legislature’s redistricting plan.” Art Harris,

Blacks, Unlikely Allies Battle Miss. Redistricting,

Wash. Post, June 1, 1982. The Department of Justice

interposed an objection under Section 5 of the VRA,

and a three-judge district court then held that a

subsequent iteration of the redistricting plan

continued to discriminate against Black voters in

violation of Section 2 of the VRA. Jordan, 604 F.

Supp. at 809, 813-15.

As noted above, the Democratic Party is not

alone in pursuing redistricting plans that seek

excessive partisan advantage at the expense of

minority voters. In 2003, after Texas Republicans

“gained control” of “both houses of the [state]

legislature,” they drew a new congressional

redistricting plan with “the dual goal of increasing

Republican seats in general and protecting

[Republican Henry] Bonilla’s incumbency.” LULAC,

548 U.S. at 423-24. In doing so, however, the

legislature diluted Latino voting strength in

Congressional District 23, in violation of Section 2 of

the VRA. Id. at 438-42. As this Court observed, “[t]he

State chose to break apart a Latino opportunity

district to protect the incumbent congressman from

the growing dissatisfaction of the cohesive and

politically active Latino community in the district.”

Id. at 441. “This b[ore] the mark of intentional

discrimination that could give rise to an equal

26

protection violation.” Id. at 440. In 2011, the

Republican legislature again redrew the lines,

including District 23. “As it did in 2003, the

Legislature [ ] reconfigured the district to protect a

Republican candidate who was not the Latino

candidate of choice from the Latino voting majority in

the district.” Perez v. Abbott, 253 F. Supp. 3d 864, 884

(W.D. Tex. 2017) (three-judge court). Indeed, a three-

judge court described the map as a whole as follows:

It is undisputed that Defendants

engaged in extreme partisan

gerrymandering in drawing the map,

ignoring many if not most traditional

redistricting principles in their attempt

to protect Republican incumbents,

unseat [a Democratic incumbent], gain

additional Republican seats, and

otherwise gain partisan advantage.

Defendants do not really dispute the fact

that minority populations are divided or

“cracked” in the plan . . . .

Id. at 945. Ultimately, the court found that the state’s

treatment of minority voters in 2011 amounted to

multiple violations of Section 2 of the VRA and the

Constitution. Id. at 908, 938, 962.

And the North Carolina map now before the

Court is the successor plan to a 2011 map that, in the

words of its own author, sought to “create as many

districts as possible” that Republicans would win and

“to minimize the number of districts in which

Democrats would have an opportunity to elect a

Democratic candidate.” Rucho J.S. App. 180. As part

of its means to this end, the legislature chose an

27

equally impermissible path: intentionally and

unjustifiably overpacking minority voters in two

specific districts.3 Harris, 137 S. Ct. at 1469-78.

In cases of this type, jurisdictions often seek to

defend themselves by asserting that the complaints

turn more substantially on partisanship than they do

on race. See Comm, for a Fair & Balanced Map v. III.

State Bd. of Elections, 835 F. Supp. 2d 563, 567, 586

(N.D. 111. 2011) (three-judge court); Harris, 137 S. Ct.

at 1473, 1476. The absence of meaningful partisan

gerrymandering doctrine allows such arguments to

flourish.

In statutory vote dilution cases, such a defense

has no purchase. See, e.g., Gingles, 478 U.S. at 63-67,

74 (plurality); id. at 100 (O’Connor, J., concurring in

the judgment); Goosby v. Town of Hempstead, 180

F.3d 476, 492-94, 495-96 (2d Cir. 1999) (rejecting the

argument that partisan explanations for otherwise

proven racial vote dilution can defeat a VRA claim).

3 It is not inconsistent to understand that North Carolina

pursued invidious partisan advantage and that it did so through

the predominant and unjustified use of race. The particular

reason why specific individuals were moved within or without

certain identified districts was predominantly based on their

race and without adequate legitimate justification. Harris, 137

S. Ct. at 1469-78. And the underlying reason to move these

individuals based on their race was the drive to entrench

Republicans and subordinate Democrats. Rucho J.S. App. 180.

The legislature employed an impermissible means to obtain an

unconstitutional objective. See Harris, 137 S. Ct. at 1473 n.7;

infra at 28-29.

28

Similarly, in constitutional claims, where the

evidence establishes that voters have been targeted

based on their race or ethnicity, as a proxy for party,

such a defense is irrelevant. Courts have repeatedly

affirmed that the unjustified targeting of minority

voters for injury based on their race is unlawful,

whether they are targeted based on animus or as the

means to achieve ultimate partisan ends. See, e.g.,

Veasey v. Abbott, 830 F.3d 216, 241 n.30 (5th Cir.

2016) (en banc) (Haynes, J.) (noting that “[ijntentions

to achieve partisan gain and to racially discriminate

are not mutually exclusive” and that accordingly,

“acting to preserve legislative power in a partisan

manner can also be impermissibly discriminatory”),

cert, denied, 137 S. Ct. 612 (2017); N.C. State

Conference of NAACP v. McCrory, 831 F.3d 204, 222

(4th Cir. 2016) (noting that “intentionally targeting a

particular race’s access to the franchise because its

members vote for a particular party, in a predictable

manner, constitutes discriminatory purpose”), cert,

denied, 137 S. Ct. 1399 (2017); Garza, 918 F.2d at 778

& n. 1 (Kozinski, J., concurring and dissenting in part)

(explaining that incumbents may pursue intentional

racial discrimination for political gain without

displaying racial animus); One Wis. Institute, Inc. v.

Thomsen, 198 F. Supp. 3d 896, 924-25 (W.D. Wis.

2016) (holding that a voting measure in Wisconsin

“was motivated in part by the intent to discriminate

against voters on the basis of race” and that

“suppressing the votes of reliably Democratic minority

voters in Milwaukee was a means to achieve [a]

political objective”), appeal docketed, No. 16-3091 (7th

Cir. Aug. 3, 2016); see also Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d

1398, 1408 (7th Cir. 1984) (finding, in the

circumstances of that case, that “there is little

29

point. . . in distinguishing discrimination based on an

ultimate objective of keeping certain incumbent

whites in office from discrimination borne of pure

racial animus”); cf. Harris, 137 S. Ct. at 1473 n.7

(noting, in the context of racial gerrymander claims,

that strict scrutiny applies “if legislators use race as

their predominant districting criterion with the end

goal of advancing their partisan interests”).

However, as this Court and other federal courts

have recognized, race and party are, in certain

contexts, closely intertwined. See, e.g., Abbott v.

Perez, 138 S. Ct. 2305 (2018); Harris, 137 S. Ct. at

1474 (noting evidence that in North Carolina, “racial

identification is highly correlated with political

affiliation” (quoting Easley v. Cromartie, 532 U.S. 234,

242 (2001))); United States v. Charleston Cnty., 365

F.3d 341, 352 (4th Cir. 2004) (Wilkinson, J.) (noting

evidence that in South Carolina, party affiliation and

race were “inextricably intertwined”); Perez, 253 F.

Supp. 3d at 945 (noting evidence that “race and

political party affiliation are strongly correlated in

Texas”).4 Particularly in those circumstances,

defendants may attempt to shield themselves from

claims of racial discrimination by claiming partisan

4 Of course, even where such correlation exists, it in no way

renders race and party legally equivalent or fungible. As

described above, targeting minority voters for injury has long

been recognized as unlawful, period, whether as a proxy for party

or not. And minority voters continue to face unlawful

discrimination within closed party primaries, where opposition

on the basis of party is not at issue. See, e.g., McMillan v.

Escambia Cnty., Fla., 748 F.2d 1037, 1044 (11th Cir. 1984).

30

intent—and where the evidence is insufficient to

distinguish the two, an egregious gerrymander may

inflict its damage without evidence sufficient to prove

that voters were specifically targeted because of their

race or ethnicity. See, e.g., Perez, 253 F. Supp. 3d at

969-72. Confessing to one misdeed may supply a

narrow defense to another, but it should not yield

blanket exculpation. Where the intent to entrench

favored partisans and subordinate opposing voters

based on their partisanship works its own material

harm, doctrines designed to combat racial injustice

should not provide the exclusive source of relief. In

these circumstances, the recognition of a properly

structured claim for partisan gerrymandering could

not only lessen the need for courts to disentangle race

and party, but also better ensure that the

fundamental rights of all voters are fully protected.

See, e.g., Bruce E. Cain & Emily R. Zhang, Blurred

Lines: Conjoined Polarization and Voting Rights, 77

O hio St. L.J. 867, 871, 904 (2016) (noting that “racial,

partisan, and administrative motives have blurred’’

and that “if the Court decides to adjudicate partisan

gerrymandering claims, it would obviate much of the

quagmire . . . on how racial motivations may be

disentangled from partisan ones”).

Finally, in the absence of a legal standard for

claims of partisan gerrymandering, some partisan

actors—both Democrats and Republicans—have also

attempted to bring unwarranted race-based claims to

address partisan excesses. See, e.g., Samuel

Issacharoff, Gerrymandering and Political Cartels,

116 H a k v . L. R e v . 593, 630-31 (2002) (“One of the

perverse consequences of the absence of any real

constitutional vigilance over partisan

31

gerrymandering is that litigants must squeeze all

claims of improper manipulation of redistricting into

the . . . category of race.”).

As demonstrated above, some circumstances

raise both partisan and racial harm. But some do not.

Litigation that stems from partisan and not racial

discrimination but is brought under race-based causes

of action raises the risk that courts would tailor facts

or doctrine (i.e., to try to fit a square peg into a round

hole) in ways that are potentially detrimental to the

development of the law. See, e.g., Samuel Issacharoff

& Pamela S. Karlan, Where to Draw the Line?:

Judicial Review of Political Gerrymanders, 153 U. Pa .

L. REV. 541, 569 (2004) (noting “the spillover effects”

of litigation brought to “attack political

gerrymanders” under “doctrinal rubrics, such as

section 2 of the [VRA] or the Shaw cases,” and

suggesting that “the cost of repackaging essentially

partisan claims of excessive partisanship under one of

these labels is something that needs to be

considered”). Injury based on race and injury based

on partisan affiliation are of different legal, moral,

and historical character, and should be neither

confused nor conflated. The notion that partisan

claims may occasionally be merely masquerading as

race-based causes of action may warp the law and

generate skepticism around true race-based harms.

Legal doctrines focused on addressing racial

discrimination should remain dedicated to that goal,

without being subverted to contend with litigation

incentives more suitable for claims in which the

principal alleged injury is partisan. The recognition

of a distinct litigation framework including a properly

32

structured claim for partisan gerrymandering would

allow such cases to be channeled toward the most

appropriate doctrinal paths and to avoid any negative

spillover effect.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgments of the

three-judge courts should be affirmed.

March 8, 2019

Respectfully Submitted,

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

President & Director-Counsel

Janai S. Nelson

Samuel Spital

Leah C. Aden

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund, Inc .

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, New York 10006

(212) 965-2200

laden@naacpldf.org

Jennifer A. Holmes

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund , Inc .

700 14th Street N.W. Ste. 600,

Washington, DC 20005

Justin Levitt

Counsel of Record

Loyola Law School*

919 Albany St.

Los Angeles, California 90015

(213) 736-7417

justin.levitt@lls.edu

Laura W. Brill

Kendall Brill & Kelly LLP

10100 Santa Monica Blvd.,

Suite 1725

Los Angeles, California 90067

lbrill@kbkfirm .com

* Institutional affiliation for

purpose of identification only

Counsel for Amici Curiae

33

mailto:laden@naacpldf.org

mailto:justin.levitt@lls.edu

APPENDIX

List o f Amici Curiae

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. (“LDF”) is a non-profit, non-partisan law

organization established under the laws of New York

to assist Black and other people of color in the full,

fair, and free exercise of their constitutional rights.

Founded in 1940 under the leadership of Thurgood

Marshall, LDF focuses on eliminating racial

discrimination in education, economic justice,

criminal justice, and political participation.

LDF has been involved in numerous precedent

setting litigation relating to minority political

representation and voting rights before state and

federal courts, including lawsuits involving

constitutional and legal challenges to discriminatory

redistricting plans or those otherwise implicating

minority voting rights. See, e.g., Evenwel v. Abbott,

136 S. Ct. 1120 (2016); Ala. Legis. Black Caucus v.

Alabama, 135 S. Ct. 1257 (2015); Shelby Cnty. u.

Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013); Nw. Austin Mun. Util.

Dist. No. One v. Holder, 557 U.S. 193 (2009); League

of United Latin Am. Citizens v. Perry, 548 U.S. 399

(2006); Georgia u. Ashcroft, 539 U.S. 461 (2003);

Easley u. Cromartie, 532 U.S. 234 (2001); Bush v.

Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996); Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899

(1996); United States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737 (1995);

League of United Latin Am. Citizens v. Clements, 999

F.2d 831 (5th Cir. 1993) (en banc); Chisom v. Roemer,

501 U.S. 380 (1991); Houston Lawyers’ Ass’n v.

Attorney Gen. of Texas, 501 U.S. 419 (1991);

la

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986); Beer v.

United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976); White v. Regester,

422 U.S. 935 (1975) (per curiam); Gomillion v.

Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960); Terry v. Adams, 345

U.S. 461 (1953); Schnell v. Davis, 336 U.S. 933 (1949)

(per curiam); Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944);

Kirksey v. Bd. of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir.

1977); Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973).

Latino Justice PRLDEF (“LJP”) champions an

equitable society by using the power of the law

together with advocacy and education. Since its

founding as the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund, LJP has advocated for and defended

the constitutional rights and the equal protection of

all Latinos under the law. LJP has engaged in and

supported law reform civil rights litigation across the

country combatting discriminatory policies in

numerous areas and has worked to secure the voting

rights and political participation of Latino voters since

1972 when it initiated a series of suits to create

bilingual voting systems throughout the United

States. LJP has been involved in state and federal

litigation regarding Latino political representation

and voting rights, including constitutional and legal

challenges to discriminatory redistricting plans or

those otherwise implicating voting rights. See, e.g.,

Arcia v. Florida Sec'y of State, 772 F.3d 1335 (11th

Cir. 2014); Favors v. Cuomo (Favors I), 881 F. Supp.

2d 356 (E.D.N.Y. 2012); Torres v. Sachs, 381 F. Supp.

309 (S.D.N.Y. 1974); Arroyo v. Tucker, 372 F. Supp.

764 (E.D. Pa. 1974).

2a

Asian Americans Advancing Justice

(“Advancing Justice”) is a national affiliation of five

independent nonprofit organizations that actively

works to advocate for the civil and human rights of

Asian Americans and other underserved communities

to promote a fair and equitable society for all. The

Advancing Justice affiliation is comprised of our

nation’s oldest Asian American legal advocacy center

located in San Francisco (Advancing Justice - Asian

Law Caucus), our nation’s largest legal and civil

rights organization for Asian Americans, Native

Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders located in Los

Angeles (Advancing Justice — Los Angeles), the

largest national Asian American policy advocacy

organization located in Washington D.C. (Advancing

Justice — AAJC), the leading Midwest Asian American

advocacy organization (Advancing Justice - Chicago),

and the Atlanta-based Asian American advocacy

organization that serves one of the largest and most

rapidly growing Asian American communities in the

South (Advancing Justice - Atlanta). Collectively,

Advancing Justice has a long-standing history of

serving the interests of immigrant and language

minority communities, and has operated a voting

rights program for the last several decades that

ensures equal access to the voting process, language

assistance in voting for limited-English proficient

voters, and fair redistricting that empowers Asian

American communities through engagement and

representation of Asian Americans during

redistricting efforts at all levels.

The Asian American Legal Defense and

Education Fund (“AALDEF”), founded in 1974, is a

national organization that protects and promotes the

3a

civil rights of Asian Americans. By combining

litigation, advocacy, education, and organizing,

AALDEF works with Asian American communities

across the country to secure human rights for all.

AALDEF has monitored elections through annual

multilingual exit poll surveys since 1988.

Consequently, AALDEF has documented both the use

of, and the continued need for, protection under the

Voting Rights Act of 1965. AALDEF has litigated

cases around the country under the language access

provisions of the Voting Rights Act, and seeks to

protect the voting rights of language minority, limited

English proficient and Asian American voters.

AALDEF has litigated cases that implicate the ability

of Asian American communities of interest to elect

candidates of their choice, including lawsuits

involving equal protection and constitutional

challenges to discriminatory redistricting plans. See,

e.g., Favors v. Cuomo (Favors I), 881 F. Supp. 2d 356

(E.D.N.Y. 2012); Diaz v. Silver, 978 F.Supp. 96

(E.D.N.Y. 1997); OCA-Greater Houston v. Texas, No.

16-51126 (5th Cir. 2017); Alliance of South Asian

American Labor v. The Board of Elections in the City

of New York, Civ. No. l:13-CV-03732 (E.D.N.Y. 2013);

Chinatown Voter Education Alliance v. Ravitz, Civ.

No. 06-0913 (S.D.N.Y. 2006).

Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund,

Inc. (“Lambda Legal”) is a national organization

committed to achieving full recognition of the civil

rights of people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or

transgender (“LGBT”), or living with HIV—many of

whom are members of racial and ethnic minorities—

through impact litigation, education, and public policy

advocacy. Lambda Legal works to challenge the

4a

intersectional harms caused by invidious

discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender

identity, race, and ethnicity. It has participated in this

Court and lower courts in numerous cases addressing

First Amendment, Equal Protection, voting rights,

and other civil rights principles affecting LGBT

individuals and members of additional minority

groups. For example, Lambda Legal was party