Petition for Permission to Appeal Certain Orders Involving Controlling Questions of Law

Public Court Documents

July 19, 1972

113 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Petition for Permission to Appeal Certain Orders Involving Controlling Questions of Law, 1972. 0254b850-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/abd56b43-37b8-4f58-9c33-c9d18d9dc644/petition-for-permission-to-appeal-certain-orders-involving-controlling-questions-of-law. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

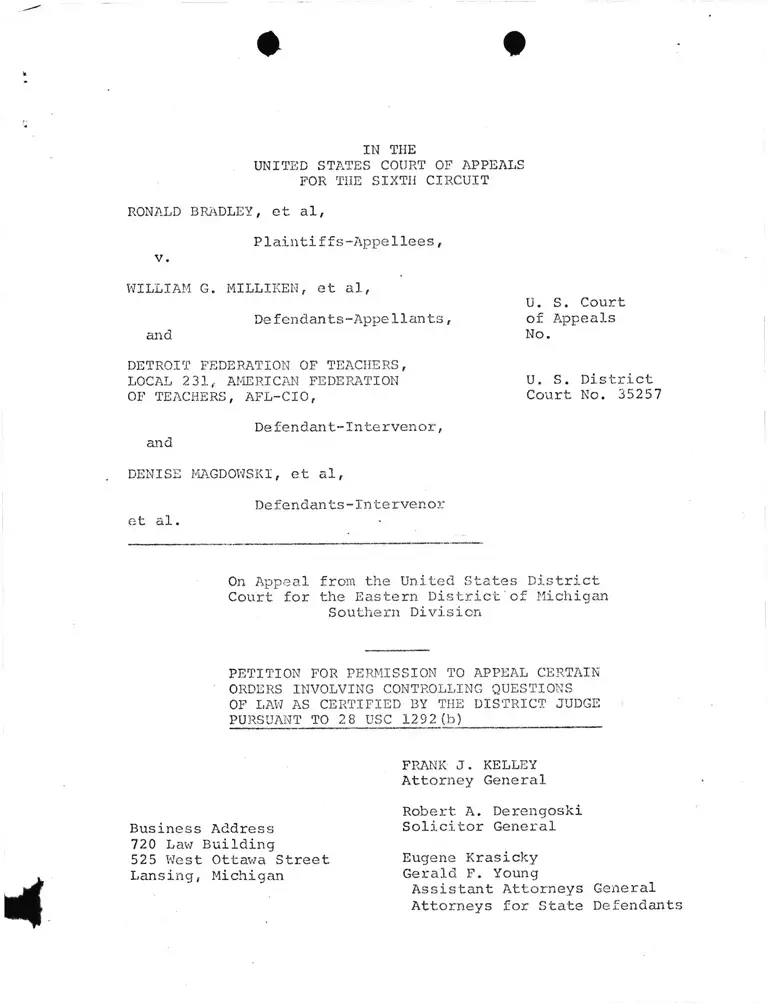

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

v.

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al,

Defendants-Appe Hants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al,

Defendants-Intervenor

et al. •

U. S. Court

of Appeals

No.

U. S. District

Court No. 35257

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Michigan

Southern Division

PETITION FOR PERMISSION TO APPEAL CERTAIN

ORDERS INVOLVING CONTROLLING QUESTIONS

OF LAW AS CERTIFIED BY THE DISTRICT JUDGE

PURSUANT TO 28 USC 1292(b)

Business Address

720 Lav; Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

Eugene Krasicky

Gerald F. Young

Assistant Attorneys General

Attorneys for State Defendant

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF 7\PPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al,

Defendants-Appellants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL--CIO,

Defendant-Intervener,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al,

Defendants-Intervener,

et al.

U.S. Court

of Appeals

No.

U.S. District

Court No. 35257

PETITION FOR PERMISSION TO 7CPPEAL CERTAIN

ORDERS INVOLVING CONTROLLING QUESTIONS

OF LAW AS CERTIFIED BY THE DISTRICT JUDGE

PURSUANT TO 23 USC 1.292 (b) _______

Petitioners (defendants) William G. Milliken,

Governor of the State of Michigan; Frank J. Kelley, Attorney

General of the State of Michigan; Michigan State Board of

Education; John W. Porter, Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion; and Allison Green, Treasurer of the State of Michigan,

by their attorneys Frank J. Kelley, Attorney General of the

+

State of Michigan, Robert A. Derengoski, Solicitor General,

Eugene Krasicky, Assistant Attorney General and Gerald F.

Young, Assistant Attorney General, pursuant to 28 USC 1292(b)

and FRApp P 5 petition this Court for permission to appeal

certain orders of the district judge, which orders, when

entered, will state that they involve controlling questions

of law as to which there are substantial grounds for dif

ferences of opinion and that an immediate appeal from such

orders may materially advance the ultimate termination of

this litigation.

In support of this petition petitioners show:

STATEMENT OF FACTS

1. Petitioners are duly elected or appointed offi

cials of the State of Michigan. On August 18, 1970, this

suit was instituted in the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Michigan by plaintiffs Bradley, et

al, seeking (a) a determination that as a result of

official policies and practices of these and Detroit School

District defendants and their predecessors in office a con

stitutionally impermissible racially identifiable pattern

of faculty and student assignments existed in the Detroit

public schools, and (b) a determination that legislative

2-

enactment of the State of Michigan 1970 PA 48, being MCLA

388.171a et seq; MSA 15.2298(la) et seq, which "allegedly

delayed and interferred with the implementation of a voluntary

plan of partial high school pupil desegregation which had

been adopted by the Detroit Board of Education," was uncon

stitutional.

2. This Court ruled section 12 of said Act 48

invalid under US Const Am XIV. 433 F2d 897.

3. After lengthy trial the District Court, on

September 27, 1971, entered its Ruling on Issue of Segrega

tion, Appendix A attached. The Court concluded, both as

a matter of fact and of lav;, that the public schools in

Detroit are "segregated on a racial, basis" and that both

state and local defendants "have committed acts which have

been causal factors in the segregated condition."

with regard to the Governor was that he was an ex officio

member, without a vote, of the State Board of Education,

he signed 1970 PA 48, which had been adopted by the legis

lature with only 1 dissenting vote, and he appointed the

boundary commission required by said Act 48. No testimony

4. The sole testimony introduced at the trial

was introduced at the trial with regard to the Attorney

General.

- 3-

5. The sole testimony offered at the trial with

regard to the State Board of Education and the Superintendent

of Public Instruction was that the State Board of Education

had joined with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission in 1966

in the issuance of a joint policy statement on the quality

of educational opportunity, and that the State Board of

Education's "School Plant Planning Handbook" stated

that care in site selection must be taken if housing patterns

in an area would result in a school largely segregated on

racial, ethnic or socio-economic lines. Neither the State

Board of Education nor the Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion under Michigan law has the authority to approve site

location. ■

6. In its ruling the court found that the School

District of the City of Detroit was not segregated with regard

'• P

to its teaching and administrative staff.

7. The principal evidence relied upon by the Dis

trict Court in its ruling was evidence of housing segregation

with regards to which neither these defendants nor the Detroit

School District defendants played any part. These defendants

continuously objected during the trial to the admissibility

of such evidence pursuant to this Court's rulings in Deal v

Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F2d 55 (1966), and Deal

v Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F2d 1337 (1969).

, - 4-

8. The District Court also relied upon evidence

of a few isolated instances, such as the busing of a small

number of black students past a white school to attend a

newer school in a black neighborhood. Such incidents were

promptly corrected as soon as they were brought to the atten

tion of the proper Detroit Public School officials.

9. On March 24, 1972, the District Court entered

its Ruling on Propriety of Considering a Metropolitan Remedy

to Accomplish Desegregation of the Public Schools of the

City of Detroit, Appendix C attached. The substance of this

ruling was that if the court found an intra-Detroit school

district plan inadequate, the court was bound by the decisions

of the United States Supreme Court to decree a metropolitan

remedy.

10. On March 28, 1972, the District Court issued

its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Lav; on Detroit-Only

Plan of Desegregation (Appendix C attached), in which it

said that: I

"The court must look beyond the limits of

the Detroit school district for a solution

to the problem of segregation in the

Detroit public school."

The substance of this ruling was that because of the com

position of the student body in the Detroit school system

' - 5-

(approximately 65% black; 35% white) it could not be deseg

regated because every school would have a substantially

black student body.

11. On June 14, 1972, the District Court entered

its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Support of

Ruling on Desegregation Area and Development of Plan and

its Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order for Development

of Plan of Desegregation, Appendix D attached. In its Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law, the court noted, initially,

that it had taken no proofs and made no findings with respect

to the establishment of the boundaries of the 86 public school

districts in the Counties of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb, nor

on the issue of whether, with the exclusion of the Detroit

school district, such school districts have committed acts

of de_ jure segregation. It should be noted, further, that

18 of the school districts included in the desegregation area

are not parties to this lawsuit.

. 12. The substance of the court's ruling and order

was to establish a desegregation area consisting of 53 inde

pendent school districts, including the Detroit public

schools; the appointment of a panel to develop a plan for

the assignment of pupils within the desegregation area and

to develop a plan for the transportation of pupils; the

- 6-

direction to the panel to make recommendations for the

acquisition of transportation; the direction that all reason

able costs of the panel be borne by the "state defendants";

the direction that faculty be assigned so that no less than

10% of the faculty and staff in each school building be

black and that where more than one building administrator

is required, a bi~racial team be assigned, the restructuring

of curriculum and facility utilization to create uniforrntiy

within the desegregation area; the direction to the State

Board of Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion to disapprove all proposals for new construction or

expansion where housing patterns in an area would result in

a school largely segregated; the establishment of in-service

training of the faculty and staff within the 53 school dis

tricts at the expense of the defendants; and the hiring of

black counsellors.

13. On July 11, 1972, the District Court entered

its order for acquisition of transportation, Appendix E

attached. In substance this order required the Detroit

Board of Education, not later than July 13, 1972, to acquire

by purchase, lease or other contractual arrangement at least

295 buses for the use in transporting pupils in the desegre

gation area in the 1972-73 school year. The "state defend

ants" were ordered to bear the costs of this acquisition.

- 7-

Also, this order added the Michigan State Treasurer, Allison

Green, as an additional defendant.

14. Approximately simultaneously with the entry

by this Court of an order staying the acquisition order of

July 11, 1972, the District Court set a hearing for July

19, 1972, for the purpose of entering an order or orders pur

suant to 28 USC 1292(b). At said hearing the District Court

ruled that it would enter an order or orders to the effect

that each of its rulings and orders, Appendices A-E attached,

contained controlling questions of lav;. At the time of

writing this petition, such order, or orders, .have not been

entered, but petitioners are informed and believe that such

order or orders will be entered on the morning of July 20,

1972.

STATEMENT OF THE QUESTIONS

Ruling on Issue of Segregation, September

27, 1971, Appendix A

1. Based on the record in this case, is the Dis

trict Court's findings of fact and conclusions of law of

de jure segregation in the public schools of the Detroit

School District in error?

2. Based on the record in this case, are the public

schools of the Detroit School District de jure segregated

- 8-

schools as a result of the conduct of any of the state -

defendants herein?

3. Whether the lower court erred in admitting into

evidence and relying upon evidence of racial discrimination

in housing by persons not parties to this cause, in finding

de jure segregation in the Detroit public schools.

4. Whether the lower court erred in denying these

defendants 41(b) motion made at the close of plaintiffs case

in chief?

5. Whether the lower court, erred in making find

ings against these defendants based on evidence introduced

after these defendants had made their 4.1b motion and rested

at the close of plaintiffs' case in chief?

6. Whether the lower court's legal conclusion of

systematic educational inequality between Detroit and the

surrounding suburban school districts, based upon transporta

tion funds, bonding limitations, and the state school aid

formula, is erroneous as a matter of law?

7. Whether the lower court's legal conclusion of

de jure segregation by these defendants in the matter of

site selection for school construction is erroneous as a

matter of lav/?

- 9 -

• • -

Ruling On Propriety of Considering a _

Metropolitan Remedy, Etc., March 24,

1972f Appendix B.

8. Where the Detroit School District has been

found to have committed acts of do jure segregation, may

the District Court properly issue a desegregation order

extending to other geographically and politically independent

school districts and require interdistrict transfers of

students, (1) absent any claim or finding that such other

school districts are themselves guilty of de_ jure segrega

tion, or (2) absent any claim or finding that the boundary

lines of such school districts were created and maintained

for the purpose of creating or fostering a dual school system?

Findings of Fact & Conclusions of Law

on-Detroit. Only Plans of Desegregation

of March 28, 1972tAppendix C.

9. Based on the record in this case, can constitu

tionally adequate unitary school systems be established within

the geographical limits of the Detroit School District?

10. Whether a finding of de_ jure segregation as

to some schools within the Detroit School District warrants

a desegregation remedy for all schools in the school district

or only for those schools within the school district found to

be de jure segregated schools?

- 10-

Ruling on Desegregation Areva, Etc. , of

June 14, 1972, Appendix D. .

11. The foregoing ruling, finding and conclusions

of June 14, 3.9 72 , encompass all of the previously stated

questions set forth above. In addition, the same presents

the following question: Based on the record in this case,

did the District Court exceed its equitable authority in

ordering the remedial plan of metropolitan desegregation out

lined and set forth therein?

Order for Acquisition of Transportation,

July 11, 1972, Appendix E.

12. Whether, in the absence of any proofs or

findings concerning either the establishment of the boundaries

of the 86 public school districts in Wayne, Oakland and

Macomb Counties or whether any of these 86 school districts,

with the exception of the School District of the City of

Detroit, have committed any acts of de jure segregation,

the District Court may adopt a metropolitan remedy?

13. Whether a district court may compel state offi

cials to perform acts beyond their lawful authority to per

form under state law in a school desegregation remedial order?

14. This petition for permission to appeal is

filed on this early date at the direction of the clerk of

11-

the Court of Appeals after only a matter of hours for prepara

tion and the petitioner respectfully requests leave to amend

the same to add additional questions, if necessary, within

the 10 day period after entry of the amended orders of the

District Court from which the within appeal is sought.

STATEMENT OF (1) SUBSTANTIAL BASIS FOR

DIFFERENCE OF OPINION AND (2) IMMEDIATE

APPEAL MAY MATERIALLY ADVANCE THE

TERMINATION OF LITIGATION.__________

1. Now involved in this litigation are approximately

800,000 public school children, roughly 1/3 of the public

school children in the State of Michigan, and 53 school dis

tricts, which, prior to the District Court's order of June

14, 1972, Appendix D, were independent bodies corporate

vested with plenary powers by state lav; to educate the child

ren residing within their respective boundaries. Eighteen

of these bodies corporate are not parties to this lawsuilt.

There has been no decision by the trial court that any of

these bodies corporate, except the School District of the

City of Detroit, were segregated de_ jure along racial lines.

Neither has it been determined by the trial court (nor have

proofs been taken) that the boundaries of these 53 independent

bodies corporate were established for purposes of cte jure

segregation, or, that the de_ jure segregation found in the

Detroit schools was the result of these boundaries.

- 12-

The constitution and laws of the State of Michigan

require unitary school systems. Const 1963, Art VIII, §2.

MCLA 340.355; MSA 15.3355. See also Workman v Board of Educa

tion of Detroit, 18 Mich 399 (1869).

The principal basis for the District Court’s find

ing of de jure segregation within the Detroit public schools

was segregated housing patterns, evidence of which this Court

ruled to be inadmissible in the two Deal cases, 369 F2d 55

(1966), and 419 F2d 1387 (1969). The District Court's find

ing as to de jure segregation against the Board of Education

of the City of Detroit at most rests upon a finding that a

few schools were segregated as to race. Such a finding does

not support a ruling that the Detroit school system is a de

jure segregated system. Keyes v School District No. 1,

Denver, Colorado, 445 F2d. 999 (1971), cert granted ___US

__92 SCt 707, 30 L Ed 2d 728 (1972).

The findings of de_ jure segregation with regard

to petitioners is totally unsupported by the record. No

findings were made against the Attorney General. The find

ings against the Governor amounted to his signing a legisla

tive enactment, only one section of which was found to be

unconstitutional, and the appointment of the boundary com

mission required by said act.

- 13-

The findings against the State Board of Education

and the Superintendent of Public Instruction were that they

had issued a policy statement in 1966 and a planning handbook,

the latter involving site selection over which they had no

authority.

The metropolitan remedy ordered by the Court is

totally unprecedented not only in its scope but for the

total lack of supporting findings. A similar remedy of far

less magnitude in a state which segregated the races in the

schools by constitution and statute and which remedy was

supported by findings of fact was recently reversed by the

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Bradley v School

Board of City of Richmond, Virginia, ___ F2d ___ (June 5,

1972) .

Further, the District Court's order for development

of plan of desegregation, June 14, 1972, Appendix D, is pre

dicated upon the misconception of a constitutional duty to

achieve racial balance in the public schools, a misconception

clearly denounced in Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, 402 US 1 (1971), and Spencer v Kugler, 326 F Supp

1235 (DC NJ, 1971), aff'd 404 US 1027 (1972).

Petitioners respectfully submit that a substantial

basis exists for a difference of opinion.

- 14-

2. If the District Court's ruling on segregation,

September 27, 1971, Appendix A, is reversed this litigation

will terminate forthwith. If the District Court's rulings

and orders, first with reference to the propriety of a

metropolitan remedy, second with reference to the Detroit-

Only Plans of Desegregation and third with reference to the

desegregation area and development of plan of desegregation

are reversed, this litigation will terminate forthwith for

the vast majority of the parties in this action, and some

18 school districts that are not parties. If the decisions

are reversed, state funds will not be expended contrary to

state lav/ for the purchase of unneeded school buses.

Last, a ruling by this Court, even if such a ruling

affirmed all of the District Court's rulings and orders above

referred to, will expedite an appeal to the United States

Supreme Court and the final resolution and termination of

the litigation.

WHEREFORE, petitioners pray that their petition

for permission to appeal pursuant to 28 USC 1292(b) be granted.

Respectfully submitted, .

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Robert A. Derengoski

Solicitor General

- 15-

Eugene Krasicky

Gerald F. Young

George McCargar

Assistant Attorneys Genral

Business Address:

720 Law Building

525 West Ottawa

Lansing, Michigan

Dated: July 19, 1972

16-

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

)

RONALD BRADLEY, et al., • • ' • )

- - )

’ Plaintiffs )

v. ) .

)

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., )

. )

' Defendants )

)

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, )

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION )

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, )

• Defendant- )

Intervenor )

•-/ )

and . )

)

DENISE MAGDOW8KI, et al., )

. )

. ‘ Defendants- )

• • Intervenor )

____:________ ___________________________________ )

A T R U E - C O P Y

FREDERICK W. JOHNSON

BY a /

DEPUTY CLERK

CIVIL ACTION NO:

35257

RULING ON ISSUE OF SEGREGATION

This action was commenced August 18, 1970, by

plaintiffs, the Detroit Branch of the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People and individual parents and

students, on behalf of a class later defined by order of the

Court dated February 16, 1971, to include "all school, children

of the City of Detroit and all Detroit resident parents who

have children of school age." Defendants are the Board of

Education of the City of Detroit, its members and its former

superintendent of schools, Dr. Norman A. Drachler, the Governor,

Attorney General, State Board of Education and State Superin

tendent of Public Instruction of the State of Michigan. In

their complaint, plaintiffs attacked a statute of the State

of Michigan known as Act 48 of the 1970 Legislature on the

*

The

not contes

no opinion

standing of the NA7iCP as a proper party plaintiff was

ted by the original defendants and the Court expresses

on the matter.

APPENDIX A

ground that it put the State of Michigan in the position of

unconstitutionally interfering with the execution and operation

of a voluntary plan of partial high school desegregation

(known as the April 7, 1970 Plan) which had been adopted by

the Detroit Board of Education to be effective beginning with

the fall 1970 semester. Plaintiffs also alleged that the

Detroit Public School System was and is segregated on the .

. basis of race as a result of the official policies and actions

of the defendants and their predecessors in office.

. -

Additional parties have intervened in the litigation

since it was commenced. The Detroit Federation of Teachers v

(DFT) which represents a majority of Detroit Public school

teachers in collective bargaining negotiations with the defendant

Board of Education, has intervened as a defendant, and a group

of parents has intervened as defendants.

Initially the matter was tried on plaintiffs' motion

for preliminary injunction to restrain the enforcement of ,

Act 48 so as to permit the April 7 Plan to be implemented. On

that issue, this Court ruled that plaintiffs were not entitled

to a preliminary injunction since there had been no proof that

Detroit has a segregated school system. The Court of Appeals

found that the "implementation of the April 7 Plan was thwarted

by State action in the form of the Act of the Legislature of

Michigan," (433 F.2d 897, 902), and that such action could not

be interposed to delay, obstruct or nullify'steps lawfully

taken for the purpose of protecting rights guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment. ' .

The plaintiffs then sought to have this Court direct

the defendant Detroit Board to implement the .April 7 Plan by

o . '

the start of the second semester (February, 1971) in order to

remedy the deprivation of constitutional rights wrought by the

unconstitutional statute. In response to an order of the Court,

defendant Board suggested_two other plans, along with the

April 7 Plan, and noted priorities, with top' priority assigned

to the so-called "Magnet Plan." The Court acceded to the

wishes of the Board and approved the Magnet Plan. Again,

plaintiffs appealed but the appellate court refused to pass

on the merits of the plan. Instead, the case was remanded

with instructions to proceed immediately to a trial on the

merits of plaintiffs' substantive allegations about the Detroit

School System. 438 F .2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971). \

Trial, limited to the issue of segregation, began

April 6, 1971 and concluded on July 22, 1971, consuming 41

trial days, interspersed by several brief recesses necessitated

by other demands upon the time of Court and counsel. Plaintiffs

introduced substantial evidence in support of their contentions,

including expert and factual testimony, demonstrative exhibits

and school board documents. At the close of plaintiffs' case,,

in chief, the Court ruled that they had presented a prima facie

case of state imposed segregation in the Detroit Public Schools;

accordingly, the Court enjoined (with certain exceptions) all

further school construction in Detroit pending the outcome

of the litigation. '

The State defendants urged motions to dismiss as to

them. These were denied' by the Court. . .

- At the close of proofs intervening parent defendants

(Denise Magdowski, et al.) filed a motion to join, as parties 05

«

contiguous "suburban" school districts - all’within the so-

• •

called Larger Detroit Metropolitan area. This motion was

taken under advisement pending the determination of the issue

of segregation.

. It should be noted that, in accordance' with’ earlier

rulings of the Court, proofs submitted at previous hearings

in the cause, were to be and are considered as part of the

proofs of the hearing on the merits.

In considering the present racial complexion of the

. • *

City of Detroit and its public.school system we must first look

to the past and view in perspective what has happened in the

last half century. In 1920 Detroit was a predominantly white

city - 91% - and its population younger than in more recent

times. By the year 1960 the largest segment of the city's

white population was in the age range of 35 to 50 years, while

its black population was younger and of childbearing age. The

population of 0-15 years of age constituted 30% of the total

population of which 60% were white and 40% were black. In

1970 the white population was principally aging--45 years—

while the black population was younger and of childbearing age.

Childbearing blacks equaled or exceeded the total white

population. As older white families without children of

school age leave the city they are replaced by younger black

families with school age children, resulting in a doubling

of enrollment in the local neighborhood school and a complete

change in student population from white to black. As black

inner city residents move out of the core city they "leap-frog"

the residential areas nearest their former homes and move to

areas recently occupied by whites. ' '

The population of the City of Detroit reached its

- A _

highest point in 1950 and has been- declining by approximately

169,500 per decade since then. In 1950, the city population

constituted 61% of the total population of.the standard1

metropolitan area and in 1970 it was but 36% of the metro

politan area population. The suburban population has

increased by 1,978,000 since 1940. There has been a steady

out-migration of the Detroit population since 1940. Detroit

today is principally a conglomerate of poor black and white

plus the aged. Of the aged, 80% are white.

If the population trends evidenced in the federal

decennial census for the years 1940 through 1970 continue,

the total black population in the City of Detroit in 1980

will be approximately 840,000, or 53.6% of the total. The

total population of the city in' 197 0 is 1,511,000 and, if

past trends continue, will be 1,338-, 000 in 1980. In school

year 1960-61, there were 285,512 students in the Detroit

Public Schools of which 130,765 were black. In school year

1966-67, there were 297,035 students, of which 168,299 were

black. In school year 1970-71 there were 289,743 students of

which 184,194 were black. The percentage of black students

in the Detroit Public Schools in 1975-76 will be 72.0%,

in 1980-81 will be 80.7% and in 1992 it will be virtually

100% if the present trends continue. In 1960, the non-white

population, ages 0 years to 19 years, was as follows:

0 - 4 years 42%

5 - 9 years 36%

10 - 14 years 28%

15 19 years 18%

jn 3.970 the non-white population, ages 0 years to 19 years,

was as follows:

0 - 4 years 48%

5 - 9 “years 50%

10 - 14 years .. -50%

15 - 19 years 40%

The black population as a percentage of the total population

in the City of Detroit was:

(a) 1900 1.4%

(b) 1910 1.2%

(c) 1920 4.1%

(<2) 1930 7.7%

(e) 194 0 9.2%

(f) 1950 . 16.2%

(g) 1960 vp3̂•COCM

00 1970 43.9%

The black population as a percentage of total student

population of the Detroit Public Schools was as follows:

(a) 1961 45 .8%

(b) 1963 51.3%

(c) 1964 53.0%

(d) 1965 54.8%

(e) 1966 56.7%

(f) 1967 58.2%

(g) 1968 59.4%

(h) 1969 61 .5%

(i) 1970 63.8%

For the years indicated the housing characteristics in the

City of Detroit were as follows:

.

(a) 1960 total supply of housing -

• units was 553,000 . -

(b) 1970’ total supply of housing

• . units was 530,770

The percentage decline* in the white students in the

\ . .

Detroit Public Schools during the period 1961-1970 (53.6%

in 1960; 34.8% in 1970) has been greater than the percentage

decline in the white population; in the City of Detroit during

the same period (70.8% in 1960; 55.21% in 1970), and

correlatively, the percentage increase in black students in

the Detroit Public Schools during the nine-year period 1961

1970 (45.8% in 1961; 63.8% in 1970) has been greater than the

percentage increase in the black population of the City of

Detroit during the ten-year, period 1960-1370 (28.3% in

1960; 43.9% in 1970). In 1961 there were eight schools in

the system without white pupils and 73 schools with no

Negro pupils. In 1970 there were 30 schools with no

white pupils and 11 schools with no Negro pupils, an

increase in the number of schools without white pupils of

22 and a decrease in the number of schools without •

Negro pupils of 62 in this ten-year period. Between

1968 and 1970 Detroit experienced the largest increase in

percentage of black students in the student population of any

major northern school district. The percentage increase in

Detroit was 4.7% as contrasted with —

New York 2.0%

Los Angeles 1.5%

Chicago 1.9%

- 7 -

• •

Philadelphia 1.7%

Cleveland 1.7%

Milwaukee 2 .6%

St. Louis 2.6%

Columbus ' 1.4%

Indianapolis ■ 2.6%

Denver ■ .

Boston 3.2%

San Francisco 1.5%

Seattle 2.4%

. in I960, there were 266 schools in the Detroit

School System. In 1970, there were 319 schools in the

Detroit School System. - . . - .

» . • •

• In the Western, Northwestern, Northern, Murray,

Northeastern, Kettering, King and Southeastern high school

service areas, the following conditions exist at a level

significantly higher than the city average:

. (a) Poverty in children •

(b) Family income below poverty level

■' (c) Rate of homicides per population

(d) Number of households headed by females

(e) Infant mortality rate

(f) Surviving infants with neurological

defects

(g) Tuberculosis cases per 1,000 population

(h) High pupil turnover, in schools

The City of Detroit is a community generally dividea

by racial lines. Residential segregation within the city and

throughout the larger metropolitan area is substantial, per

vasive and of long standing. Black citizens are located in

- 0 - t

separate and distinct areas within the city and are not

generally to be found in the suburbs. While the racially '

unrestricted choice of black persons and economic factors

may have played some part in the development of this pattern

of residential segregation, it is, in the main, the result

of past and present practices and customs of racial discrimina

tion, both public and private, which have and do restrict the

housing opportunities of black people. On the record there

can be no other finding.

. - »

Governmental actions and-inaction at all levels,

federal, state and local, have combined, with'those of

private organizations, such as loaning institutions and real

estate associations and brokerage firms, to establish and

to maintain the pattern of residential segregation throughout

the Detroit metropolitan area. It is no answer to say that

restricted practices grew gradually (as the -black population

in the area increased between 1920 and 1970), or that since

1948 racial restrictions on the ownership of real property

have been removed. The policies pursued by both government

and private persons and agencies have a continuing and present

• ' • effect upon the complexion of the.community - as we know,

the choice of a residence is a relatively infrequent affair.

Per many years FHA and VA openly advised and advocated the

maintenance of "harmonious" neighborhoods, i_.j2., racially

and economically harmonious. The conditions created

continue. While it would be unfair to charge the present

defendants with what other governmental officers or agencies

i

have done, it can be said that the actions or the failure to

act by the responsible school authorities, both city and

«

state, were linked to that of these other governmental units.

When we speak of governmental action we should not view the

different agencies as a collection of unrelated units.

Perhaps the most that can be said is that all of them,

including the school authorities, are, in part, responsible -

for the segregated condition which exists. 7\nd we note that

just as there is an interaction between residential patterns

and the racial composition of the schools, so there is a

corresponding effect on the residential x^attern by the racial

composition of the schools.

Turning now to the specific and pertinent (for our

purposes) history of the Detroit school system so far as it

involves both the local school authorities and the state

school authorities, we find the following:

During the decade beginning in 1950 the Board

created and maintained optional attendance zones in neighbor

hoods undergoing racial transition and between high school

attendance areas of opposite predominant racial compositions.

In 1959 there were eight basic optional attendance areas

affecting 21 schools. Optional attendance areas provided

pupils living within certain elementary areas a choice of

attendance at one of two high schools. In addition there

was at least one optional area either created or existing in.

1960 between two junior high schools of opposite predominant

racial components. All of the high school optional areas,

except two, were in neighborhoods undergoing racial

transition (from white to black) during the 1950s. The two

exceptions were: (1) the option between Southwestern

(61.6% black in 1960) and Western (15.3% black); (2) the

option between Denby (0% black) and Southeastern (30.9% black)

Wit}', the exception of the Denby-Southeastern option (just

- 10 -

noted) all of the options were between high schools of

opposite predominant racial compositions. The Southwestern-

Western and Denby-Southeastern optional areas are all white

on the 1950, 1960 and 1970 census maps. Both Southwestern

and Southeastern, however, had substantial white pupil

populations, and the option allowed whites to escape integra

tion. The natural, probable, forseeable and actual effect of

these optional zones was to allow white youngsters to escape

identifiably "black" schools. There had also been an optional

zone (eliminated between 1956 and 1959) created in "an

attempt . . . to separate Jews and Gentiles within the

system," the effect of which was that Jewish youngsters

went to Mumford High School and Gentile youngsters went to

Cooley. Although many of these optional areas had served

their purpose by 1960 due to the fact that most of the areas

had become predominantly black, one optional area (Southwestern

Western affecting Wilson Junior High graduates) continued until

the present school year (and will continue to effect 11th and

12th grade white youngsters who elected to escape from

predominantly black Southwestern to predominantly white Western

High School). Mr. Henrickson, the Board's general fact witness,

who was employed in 1959 to, inter alia, eliminate optional

areas, noted in 1967 that: "In operation Western appears to

be still the school to which white students escape from

predominantly Negro surrounding schools." The effect of

eliminating this optional area (which affected only 10th

graders for the 1970-71 school year) was to decrease

Southwestern from 86.7%'black in 1969 to 74.3% black in 1970.

. The Board, in the operation of its transportation

«

to relieve overcrowding policy, has admittedly bused black

- 11 -

pupils past or away from closer white schools with available

space to black schools. This practice has continued in

several instances in recent years despite the Board's pvowed

policy, adopted in 1967, to utilize transportation to

increase integration. ■ ■

. With one exception (necessitated by the burning of

a white school), defendant Board' has never bused white

children to predominantly black schools. The Board has not

bused white pupils to black schools despite the enormous

amount of space available in inner-city schools. There were

22,961 vacant seats in schools 90% or more black.

The Board has created and altered attendance zones,

maintained and altered grade structures and created and

altered feeder school patterns in a manner which has had the

natural, probable and actual effect of continuing bla^.k and

white pupils in racially segregated schools. The Board admits

at least one instance where it purposefully and intentionally

built and maintained a school and its attendance zone to

contain black students. Throughout the last decade (and

presently) school attendance zones of opposite racial

compositions have been separated by north—south boundary lines

despite the Board's awareness (since at least 1962) that

drawing boundary lines in an east-west direction would result

in significant integration. The natural and actual effect of

these acts and failures to act has been the creation and

perpetuation of school segregation. There has never been a

feeder pattern or zoning change which placed a predominantly

white residential area into a predominantly black school zone

or feeder pattern. Every school which was 90% or more black

in I960, and which is still in use today, remains 90% or more

black. Whereas 65.8% of Detroit's black students attended

90%. or more black schools in I960, 74.9% of the black students

attended 90% or more black schools during the 1970-71 school

year. ' • •

The public schools operated by defendant Board are

thus segregated on a racial basis. This racial segregation

is in part the result of. the discriminatory acts and omissions

of defendant Board.

In 1966 the defendant State Board of Education and

Michigan Civil Rights Commission issued a Joint Policy State

ment on Equality of Educational Opportunity, requiring that

"Local school boards must consider the factor of

. racial balance along with other educational

considerations in making decisions about selection

- of new school sites, expansion of present

facilities . . . . Each of these situations

presents an opportunity for integration." ■ - ■

Defendant State Board's "School Plant Planning Handbook" requires

that . ' ‘‘ •

"Care in site location must be taken if a serious

transportation problem exists or if.housing

patterns in an area would result -in a school

largely segregated on racial, ethnic, or socio-

, economic lines."

The defendant City Board has paid little heed to these statements

and guidelines. The State defendants have similarly failed to

take any action to effectuate these policies. Exhibit NN

reflects construction (new or additional) at 14 schools which

opened for use in 1970-71; of these 14 schools, 11 opened over

90% black and one opened less than 10% black. School con

struction costing $9,222,000 is opening at Northwestern High

School which is 99.9% black, and new construction opens at

Brooks Junior High, which is 1.5% black, at a- cost of $2,500,000.

The construction at Brooks Junior High plays a dual segregatory

role: not only is the construction segregated, it will result

1; . '

in a feeder pattern change which will remove the last,majority

' . I _

white school from the already almost all-black Mackenzie High

School attendance area. . . '

Since 1959 the Board has constructed at least.13

snuill primary schools with capacities of from 300 to 400 pupils.

This practice negates opportunities to integrate, "contains"

the black population and x^erpetuates and compounds school

segregation. / .■ - ■

The State and its agencies, in addition to their •

general responsibility for and supervision of public education,

have acted directly to control and maintain the pattern of

segregation in the Detroit schools. The State refused, until

this session of the legislature, to provide authorization or

funds for the transportation of pupils within Detroit regardless

of their poverty or distance from the school to which they

were assigned, while providing in many neighboring, mostly

white, suburban districts the full range of state supported

transportation. This and other financial limitations, such

• «

as those on bonding and the working of the state aid formula

whereby suburban districts were able to make far larger per

pupil expenditures desx^ite less tax effort, have created and

perpetuated systematic educational inequalities.

■ The State, exercising what Michigan courts have held

to be is "plenary power" which includes power "to use a

statutory scheme, to create, alter, reorganize or even dissolve

a school district, despite any desire of the school district,

(

its board, or the inhabitants thereof," acted to reorganize

- 14 -

the school district of the City of Detroit.

'The State acted through Act 48 to impede, delay

and minimize racial integration in Detroit schools. |f.he

first sentence of Sec. 12 of the Act was directly related to

the April 7, 1970 desegregation plan. The remainder of the

section sought to prescribe for each school in the eight

districts criterion of "free choice" (open enrollment) and

"neighborhood schools" ("nearest School priority acceptance"),

which had as their purpose and effect the maintenance of

segregation. '

In view of our findings of fact already noted we

think it unnecessary to parse in detail the activities of the

local board and the state authorities in the area of school

construction and the furnishing of school facilities. It. is

our conclusion that these activities were in keeping, generally,

with the discriminatory practices which advanced or perpetuated

racial segregation in these schools.

It would be unfair for us not to recognize the

many fine steps the Board has taken to advance the cause of

quality education for all in terms of racial integration and

human relations. The most obvious of these is in the field

of faculty integration.

Plaintiffs urge the Court to consider allegedly

discriminatory practices of the Board with respect to tne

hiring, assignment and transfer of teachers and school

administrators during a period reaching back more than 15

years. The short answer to that must be that black teachers

and school administrative personnel were not readily available

in that period. The Board and the intervening defendant union

-1 5

have followed a most advanced and exemplary course in adopting

and"carrying out what is called the "balanced staff concept" -

which seeks to balance faculties in each school with respect

to race, sex and experience, with primary emphasis on race. -

More particularly, we find: • ' -

1. With the exception of affirmative policies

designed to achieve racial balance in instructional staff, no

teacher in the Detroit Public Schools is hired, promoted or

I

assigned to any school by reason of his race. • ■

2. In 1956, the Detroit Board of Education adopted

the rules and regulations of the Fair Employment Practices

Act as its hiring and promotion policy and has adhered to

this policy to date.

3. The Board has actively and affirmatively sought

out and hired minority employees, particularly teachers and

administrators, during the-past decade. -

4. Between 1960 and 1970, the Detroit Board of

Education has increased black representation among its

teachers from 23.3% to 42.1%, and among its administrators

from 4.5% to 37.8%. ' ■ .

5. Detroit has a higher proportion of black

administrators than any other city in the country.

6. Detroit ranked second to Cleveland in 1968

among the 20 largest northern city school districts in the

percentage of blacks among the teaching faculty and in 1970

surpassed Cleveland by several percentage points. .

- 1 6 -

employs black teachers in a greater percentage than the

percentage of adult black persons in the City of Detroit.

8. Since 1967, more blacks than whites have! been

placed in high administrative posts with the Detro'it Board

of Education. ' .

. 9. The allegation that the Board assigns black

teachers to black schools is not supported by the record.

10. Teacher transfers are not granted in the Detroit

Public Schools unless they conform with the balanced staff

concept.

11. Between 1960 and 1970, the Detroit Board of

Education reduced the percentage of schools without black

faculty from 36.3% to 1.2%, and of the four schools currently

without black faculty, three are specialized trade schools

where minority faculty cannot easily be secured.

12. In 1968, of the 20 largest northern city -

school districts, Detroit ranked fourth in the percentage

of schools having one or more black teachers and third in t

the percentage of schools having three or more black teachers.

13. In 1970, the Board held open 240 positions in

schools with less than 25% black, rejecting white applicants

for these positions until qualified black applicants could

be found and assigned.

14. In recent years, the Board has come under pressure

from large segments of the black community to assign male

black -administrators to predominantly black schools to serve

1 7 -

£is male role models for students, but such assignments have

been made .only where consistent with the balanced staff

concept. . '

15. The numbers and percentages of black teachers

in Detroit increased from 2,275 and 21.6%, respectively,

in February, 1961, to 5,106 and 41.6%, respectively, in.

October, 1970. .

• 16. The number of schools by percent black of

staffs changed from October, 1963 to October, 1970 as - -.-

follows: ' .

Number of schools without black teachers—

decreased from 41, to 4. ■

. Number of schools with more than 0%, but less

- than 10% black teachers~-decreased from 58, to 8.

Total number of schools with less than 10% black

teachers— decreased from 99, to 12.

• Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers—

increased from 72, to 124.

17. The number of schools by percent black of staffs

changed from October, 1969 to October, 1970, as follows:

- Number of schools without black teachers— decreased

from 6, to 4.

Number of schools with more than 0%, but less than

10% black teachers— decreased from 41, to 8.

Total number of schools with less than 10% black

■ teachers— decreased from 47, to 12.

Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers—

increased from 120, to 124.

18. Tlie total number of transfers necessary to

achieve, a faculty racial quota in each school corresponding to

the system-wide ratio, and ignoring all other elements is,

as of 1970, 1,026.

3-9. If account is taken of other elements necessary

to assure quality integrated education, including qualifies- •

tions to teach the subject area and grade level, balance of

experience, and balance of sex, and further account is taken

of the uneven distribution of black teachers by subject

taught and sex, the total number of transfers which would be

necessary to achieve a faculty racial quota in each school

corresponding to the system-wide ratio, if attainable at all,

would be infinitely greater.

20. Balancing of staff by qualifications for subject.,

and grade level, then by race, experience and sex, is educationally

desirable and important.

21. It is important for students to have a success

ful role model, especially black students in certain schools,

and at certain grade levels-. '

22. A quota of racial balance for faculty in each

school which is equivalent to the system-wide ratio and

without more is educationally undesirable and arbitrary.

23., A severe teacher shortage in the 1950s and

1960s impeded integration-of-facuity opportunities.

24. Disadvantageous teaching conditions in Detroit

.in the 1960s— salaries, pupil mobility and transiency, class

size, building conditions, distance from teacher residence,

shortage of teacher substitutes, etc.— made teacher recruitment

and placement difficult.

25. The Board did not segregate faculty by race, but

rather attempted to fill vacancies with certified and qualified

- 1 9 -

teachers who would take offered assignments.

f ̂ ■

26. Teaelier seniority in the Detroit system, .

although measured by system-wide servi.ee, has been applied '

.consistently to protect against involuntary transfers and

"bumping" in given schools. "

27. Involuntary transfers of teachers have occurred

only because of unsatisfactory ratings or because of decrease

of teacher services in a school, and then only in accordance

with balanced staff concept, r '...--- ------

28. There is no evidence in the record that Detroit

teacher seniority rights had other than equitable purpose

* •

or effect. - .

29. Substantial racial integration of staff can be

achieved, without disruption of seniority and stable teaching

relationships, by application of the balanced staff concept

to naturally occurring vacancies and increases and reductions

of teacher services. • .

30. The Detroit Board of Education has entered into

■ •

-successive collective bargaining contracts with the Detroit

Federation of Teachers, which contracts have included provisions

promoting integration of staff and students.

■ The Detroit School Board has, in many other instances

cind in many other respects, undertaken to lessen the impact

of the forces of -segregation and attempted to advance the

cause of integration. Perhaps the most obvious one was the

adoption of the April 7 Plan. Among other things, it lias

4

denied the use of its facilities to groups which practice racial

discrimination; it does not permit the use of its facilities

state legislation which would have the effect of segregating

j

the district; it has worked to placed black students in craft

. _ I ’

positions in industry and the building trades; it ha^ brought

about a substantial increase in the percentage 'of black

students in manufacturing and construction.trade apprentice

ship classes; it became the first public agency in Michigan

to adopt and implement a policy requiring affirmative act of

contractors with which it deals to insure equal employment

opportunities in their work forces; it has been a leader in

IV

j>ioneering the use of multi-ethnic .instructional material,

and in so doing has had an impact on publishers specializing

in producing school texts and instructional materials; and

it has taken other noteworthy pioneering steps to advance

relations between the white and black races.

In conclusion, however, we find that both the State

of Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education hav^ committed

acts which have been causal factors in the segregated condition

of the public schools of the City of Detroit. As we assay

the principles essential to a finding of de jure segregation,

as outlined in rulings of the United States Supreme Court,

t It. 0 s it 0 *

1. The State, through its officers and agencies,

and usually, the school administration,- must have taken some

action or actions with a'purpose of segregation.

- 2. This action or these actions must have created

or aggravated segregation in the schools in question.

. • V> n

3. h current condition of segregation exists.

-2.1 -

recognize that causation in the case before us is both

several and comparative. The pri ca in d e n i *hly

have been popoulation movement and housing patterns, but _

state and local governmental actions, including school board

actions, have ployed a substantial role in promoting

segregation. It is, the Court believes, unfortunate that we

cannot deal with public school segregation on. a no-fault

basis, for if racial segregation in our public schools is an

evil, then it should make no difference whether we classify

it de jure or de facto. Our objective, logically, it seems

to us, should be to remedy a condition which we believe needs

correction. In the most realistic sense, if fault or blame

must be found it is that of the community as a whole,

including, of course, the black coirponents. We need not

minimize the effect of the actions of federal, state and local

governmental officers and agencies, and the actions of loaning

institutions and real estate firms, in the establishment and

maintenance' of segregated residential patterns - which lead to

school segregation - to observe that blacks, like ethnic group

in the past, have tended to separate from the larger group and

associate together. The ghetto is at once both a place of

confinement and a refuge. There is enough blame for everyone

to share. .

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW .

1. This Court has jurisdiction of the parties and

the subject matter of this ^5ction under 28 U.S.C. 1331(a),

1343(3) and (4), 2201 and 2202; 42 U.S.C. 1983, 1988, and

2000 d .

2. In considering the evidence and in applying

legal standards it is not necessary that the Court find thatf ■

the policies and practices, which it has found to be dis

criminatory, have as their motivating forces any evil intent'

or motive. Keyes v. Sch, Pint. #1, Denver, 383 F. Supp. 279.

Motive, ill will and bad faith have long ago been rejected

as a requirement to invoke the protection of the Fourteenth

Amendment against racial discrimination. Sims v. Georgia,

389 U.S. 404, 407-8. .

3. School districts^-are accountable for the natural,

probable and foreseeable consequences of their policies and

practices, and where racially identifiable schools are the

result of such policies, the school authorities bear the

burden of showing that such policies are based on educationally

required, non-racial considerations. Keyes v. Sch. Dist.,

supra, and Davis v. Sch._Dist. of Pontiac, 3 09 F-. Supp. 734,

and 443 F.2d 573. ■

4. In determining whether a constitutional violation

has occurred, proof that a pattern of racially segregated

schools has existed for a considerable period of time amounts .

- to a showing of racial classification by the state and its

agencies, which must be justified by clear and convincing

evidence. State of Alabama v, U.S., 304 F .2d 583.

5. The Board's practice of shaping school attendance

zones on a north-south rather than an east-west orientation,

with the result that zone boundaries conformed to racial

residential dividing lines, violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

Kortbcross v. Bel. of Ed., Memphis, 333 F . 2 d 661.

segregation result-School System and the residential racial

*r •

ing primarily from public and private racial discrimination

are interdependent phenomena. The affirmative obligation of

the defendant Board has been and■is to adopt and implement

pupil assignment practices and policies that compensate

for and avoid incorporation into the school system the .

effects of residential racial segregation. The Board's

building upon housing segregation violates the Fourteenth

Amendment. See, Davis v . Sch. D.ist. of Pontiac, supra, and—. - i "

authorities there noted. -- --...—

7. The Board's policy of selective optional

attendance zones, to the extent that it facilitated the

separation' of pupils on the basis of rcice, was in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp.

401, aff'd sub nom., Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F .2d 175.

8. The practice of the Board of transporting black

students from overcrowded black schools to other identifiably

black schools, while passing closer identifiably white schools,

which could have accepted these pupils, amounted to an act

of segregation by the school authorities. Spangler v . Pasadena

City Bd. of Ed., 311 F. Supp. 501. .

9. The manner in which the Board formulated and

modified attendance zones for elementary schools had the

natural and predictable effect of perpetuating racial

segregation of students. Such conduct is an act of de jure

discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

M yO . v . School D j s t r i c t. 15]., 286 F. Supp. 786; Brewer v., City

of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37.

- ? . A

Fourteenth Amendment, maintain segregated elementary schools

■ I ! _or permit educations3. choices to be influenced by community

sentiment or the wishes of a majority of voters. Coopcy v .

Zniron, 358 U.S. 1, 12-13, 13 - i 6 . . • •

"h citizen's constitutional rights can hairdly be

infringed simply because a majority of the people

choose that it be." Lucas v. 44th Gen'l Assembly

of Colorado, 377 U.S. 713, 736-/37.

11. Under the Constitution of the United States

and the constitution and laws of the State of Michigan, the

responsibility for providing educational opportunity to all

children on constitutional terms is ultimately that of the

state. Turner v, Warren County Board of Education, 313 F. Supp,

380; Art. VIII, §§ 1 and 2, Mich. Constitution; Dasiewicz v .

Bd. of Ed. of the City of Detroit, 3 N.W.2d 71.

12. That a state's form of government may delegate

the power of daily administration of public schools to officials

with less than state-wide jurisdiction does not dispel the

obligation of those who have broader control to use the

authority they have consistently with the constitution. In

such instances the constitutional obligation toward the

individual school children is a shared one. Bradley v. Sch.

Bd., City of Richmond, 51 F.R.D. 139, 143. •

13. Leadership and general supervision over all

public education is vested in the State Board of Education.

Art. VIII, § 3, Mich. Constitution of 1963. The duties of the

State Board and superintendent include, but are not limited to,

specifying the number of hours necessary to constitute a school

day; approval until .1962 of school sites; approval of school

construction plans; accreditation of schools; approval of loans

r> n cr1-' C-i• 0 hi Oil S tlci Lc aic it• i i O.l :■ ) I 0 V X C \ 2 o y. S U 8 ] J 011 •■j x o n s and o>q:>ulsion

mi *-■

O .individual student s for misconduct [Op. A tty. Gen. )

July 7, 1970, No. 4701 i>] ; authority over tr;.i n Sjjo rtation routes

and disbursement of transportation funds; teacher certification

and the like. M.S.A. 15..1023 (1). State lav; provides review

procedures from actions of local or intermediate districts '

(See M.S.A. 15.3442), with authority in the State Board to

ratify, reject, amend or modify the actions of these inferior

state agencies. See M.S.A. 15.3467; 15.1919(61); 15.1919 (68b);

15.2299(1); 15.1951; 15.3402; Bridgetamoton School District

No. 2 Fractional of Carsonville, Mich, v. Supt. of Public

Instruction, 323 Mich. 615. In general, the state

superintendent is given the duty "[t]o do all things necessary

to promote the welfare of the public schools and public

educational instructions and provide proper educational

facilities for the youth of the state." M.S.A.' 15.3252.

See also M.S.A. 15.2299(57), providing in certain instances

for reorganization of school districts.

• 14. State officials, including all of the defendants,

are charged under the Michigan constitution with the duty of

providing pupils an education without discrimination with

respect to race. Art. VIII, § 2, Mich. Constitution of 1963.

Art. I, § 2, of the constitution provides:

"No person shall be denied the equal protection

of the laws; nor shall any person be denied the

enjoyment of his civil or political rights or be

discriminated against in the exercise thereof

because of religion, race, color or national

origin. The legislature shall implement this

section by appropriate legislation."

. 15.

established an

The State Department of Education has recently

Equal Educational' Opportunities section having

- 2 6 -

responsibility t.c> identity r daily ini olanced s c; i o o 1 d i s 11: i c t s

and develop desegregation plans. ' M.S.A. 15.3355 provides

that no school or department shall .be'kept - for any person or

persons on account of race or color. ■

16. The state further provides special funds to

local districts for compensatory education which are administered

on a per school basis under direct review of the State Board.

All other state aid is subject to fiscal review and accounting

by the state. M.S.A. 15.1919. See also M.S.A. 15.1919 (68b),

providing for special supplements to merged districts "for the

purpose of bringing about uniformity of educational opportunity

for all pupils of the district." The general consolidation lav;

M.S.A. 15.3401 authorizes annexation for even noncontiguous

school districts upon approval of the superintendent of public

instruction and electors, as provided by law. Op. Atty. Gen.,

Feb. 5, 1964, No. 4193. Consolidation with respect to so-

called "first class" districts, _i._e. , Detroit, is generally

treated as an annexation with the first class district being

the.surviving entity. The law provides procedures covering

all necessary considerations. M.S.A. 15.3184, 15.3186.

17. Where a pattern of violation of constitutional

rights is established the affirmative obligation under the

Fourteenth Amendment is imposed on not only individual school

districts, but upon the State defendants in this case.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358, U . S . .1;. Griffin v. County School Board

of Pr ince Edward _Countv, 3 37 U .S . 218; U.S. v. State of Georgia,

Civ. No. 12972 (N.D. Ga., December 17, 1970), rev1d on other

grounds, 428 F.2d 377; Godwin v, Johnston County Board of

Education, 301 F. Supp. 1337; Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education, 267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala.), aff‘d sub nom.,

- 2 7 -

V.' a J. 1 • * c\ v , t . a . , a U . b1 • (2. X -J* f i' i..t $'} ; v i. < n v. W t :iiUi n Cov.i.i.V

Board of Bducci1ion, 288 P . S upp. 50 9; Smith v. North Caro 1 i n a

*' '

State Board of Educationi, Ho. 15, 07 2 (4th Cir., June 14, 1971)

The foregoing const1tutes o'.:<r findings of fact and

conclusions of law on the issue of segregation in the public

schools of the City of Detroit.

Having found a de jure segregated public school

system in operation in the City of Detroit, our first step,

in considering what judicial remedial steps must be taken,

is the consideration of intervening parent defendants1

motion to add as parties defendant a great number of Michigan

school districts located out county in Wayne County, and in

Macomb and Oakland Counties, on the principal premise or

ground that effective relief cannot be achieved or ordered in

their absence. plaintiffs have opposed the motion to join

the additional school districts, arguing that the presence

of the State defendants is sufficient and all that is required,

even if, in shaping a remedy, the affairs of these other -

districts will be affected.

In considering the motion to eidd the listed school

districts we pause to note that the proposed action has to

do with relief. Having determined that the circumstances of

the case require judicial intervention and equitable relief,

it would be improper for us to act on this.motion until the

other parties to the action have had an opportunity to submit

their proposals for desegregation. Accordingly, we shall not

rule on the motion to add parties at this time. Considered

as a plan for desegregation the motion is lacking in specifi-ty

- 2 8 -

and is framed in the broadest general terms. The

. ' _ i '

may wish to amend its proposal and resubmit it as

prehensive plan of desegregation. V

moving party

j

a com-

In order that the further proceedings, 'in this cause

may be conducted on a reasonable time schedule, and because

the views of counsel respecting further proceedings cannot but

be of assistance to them and to the Court, this cause will be

set down for pre-trial conference on the matter of relief.,

The conference will be held in our Courtroom in the City of •

" . ■ *

Detroit at ten o'clock in the morning, October 4, 1971.

DATED: September 27_, 1971.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION •

RONALD BRADLEY-, et al,

Plaintiffs

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

A f R U E C O P Y

FREDERICK W. JOHNSON, Clerk

DEPUTY. CLERK

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,'

;nd

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

et al.

Dsfendant-

latervenor

Defendants-

Intervenor

CIVIL ACTION NO:

352 57

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW .

ORT■ _

■ D K T R O T T —ONT-Y' n T antq OF E E S E O R E O ETT0 >T

In accordance with orders of the court defendant

Detroit Board of Education submitted two plans, limited

to the corporate limits of the city, for desegregation

of the public schools of the City of Detroit, which we will

refer to as Plan A and plan C; plaintiffs submitted a

similarly limited plan, which will be referred to as the

Foster Plan. Hearings were had on said plans on March 14,

15, 16, 17 and 21, 1972. In considering these plans the

court docs not limit itself to the proofs offered at the

hearing just concluded; it considers as part of the evidence

bearing on the issue (_i.e. , City-Only Plans) all proofs

submitted in the case to this point, and it specifically

L a v a •! V>» » -T rsv -ci c-'w-o liv-r o j. n a.v_-o_'w-a.

Conclusions contained in its

filed September 27, 1971.

v~s « J , ' ----------- ------------ -3

u w w u i i c i x i i u x i i u j o a u u

"Ruling on Issue of Segregation,"

APPENDIX B

The court makes the following factual findings:

. ■ i

nr t\ vrt £T vi £i_ •

1. The court finds that this plan is an elabora

tion and extension of the so-called Magnet Plan, previously

authorized for implementation as e.n interim plan pending

hearing and determination on the issue of segregation.

2. As proposed we find, at the high school level,

that it offers a greater and wider degree of specialization,

but any hope' that it would be effective to desegregate the

public schools of the City of Detroit at that level is

virtually ruled out by the failure of the current model to

achieve any appreciable success.

3. We find, at the Middle School level’, that the

expanded model would affect, directly, about 24,000 pupils

ot a total or ±h\j, uuu in trie yiauet> cuvcieu; emu •\

- O ' - ■ i . j . ' - ' V '

would be to set up a school system within the school system,

and would intensify the segregation in schools not included

in the Middle School program. In this sense, it would

increase segregation. .

4. As conceded by its author, Plan A is neither a

desegregation nor an integration plan.

PLAN C „ ’ ■

- 1. The court finds that Plan C is a token or part

time desegregation effort. '

2. We find that this plan covers only a portion

of the grades and would leave the base schools no less

tracially identifiable. .

- 2 -

PLAINTIFFS' PLAN

accomplish more desegregation than now obtains in the ystem,

or would be achieved under Plan A or Plan C.

2. V.e find further that the racial composition of

the student body i uch that, the plan's implementation would

clearly make the entire Detroit public school system

racially identifiable as Black

3. The plan would require the development of trans-

■ portation on a vast scale which, according to the evidence,

could not be furnished, ready for operation, by the opening

of the 1972-73 school year. The plan contemplates the

• transportation of 82,000 pupils and would require the

or a great nuirrer or drivers, tne procurement or space

for storage and maintenance, the recruitment of maintenance

and the not negligible task of designing a transportation

' '// '

system to service the schools.

that it would not have to undergo another reorganization if

a metropolitan plan is adopted. .

. 5. It would involve the expenditure of vast sums

of money and effort which would be wasted or lost.

. 6. The plan does not lend itself as a building

block for a metropolitan plan. • .

more identifiably Black, and leave many of its schools 75 to

acquisition of some 900 vehicles, the hiring and training

4. The plan would entail an overall recasting

of the Detroit school system, when there is little assurance

7. The plan would make the Detroit school system

- 3 -

• •

90 per cent Black.

8. It would change a school system which is now

Black and White to one that - would be perceived as Black,

thereby increasing the flight of Whites from the city and

the system, thereby increasing the Black student population.

9. It would subject the students and parents,

faculty and administration, to the trauma of reassignments,

with little likelihood that such reassignments would

continue for any appreciable time.

In summary, we find that none of the three plans

would result in the desegregation of the public schools of

the Detroit school district. -

- • CONCLUSIONS OF LAW .

,.v ■ i # The court has continuing jurisdiction of this

action for all purposes, including the granting of effective

relief. See Ruling on Issue of Segregation, September 27,

1971. •

• 2. On the basis of the court's finding of illegal

school segregation, the obligation of the school defendants

is to adopt and implement an educationally sound, practicable

plan of desegregation that promises realistically to achieve

now and hereafter the greatest possible degree of actual

school desegregation. Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S.

430; Alexander -v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S.

19; Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S.

290; -Swann v. Charlotta-MecklenburH Board it ion,

- 4 -

402 U.S. 1.

.3 . Detroit Board of Education Plans A and C

are legally insufficient because they go not promise to

' ' I

effect significant desegregation. Green v..County fcchool

Board, supra, at 439-440. •

4. Plaintiffs' Plan, while it would provide a

C •

racial mix more in keeping with the Black-White proportions

of the student population than under either of t e Boar d s

plans or as the system now stands, would accentuate the .

racial identiflability of the district as a Black school

system, and would not accomplish desegregation. .

5. The conclusion, under the evidence in this

case, is inescapable that relief of segregation in the

r ■

public schools of the City of Detroit cannot be accomplished

within the corporate geographical limits of the city. The

state, however, cannot escape its constitutional duty to •

desegregate the public schools of the City of Detroit by

pleading local authority. As Judge Merhige pointed out

in Bradley v. Richmond, (slip opinion p. 64):

"The power conferred by state law on central and

local officials to determine the shape of school

attendance units cannot be employed, as it has been

here, for the purpose and with the effect of sealing

off white conclaves of a racial composition more

appealing to the local electorate and obstructing the

desegregation of schools. The equal protection

clause has required far greater inroads on local •

government structure than the relief sought here,

which is attainable without deviating- from state