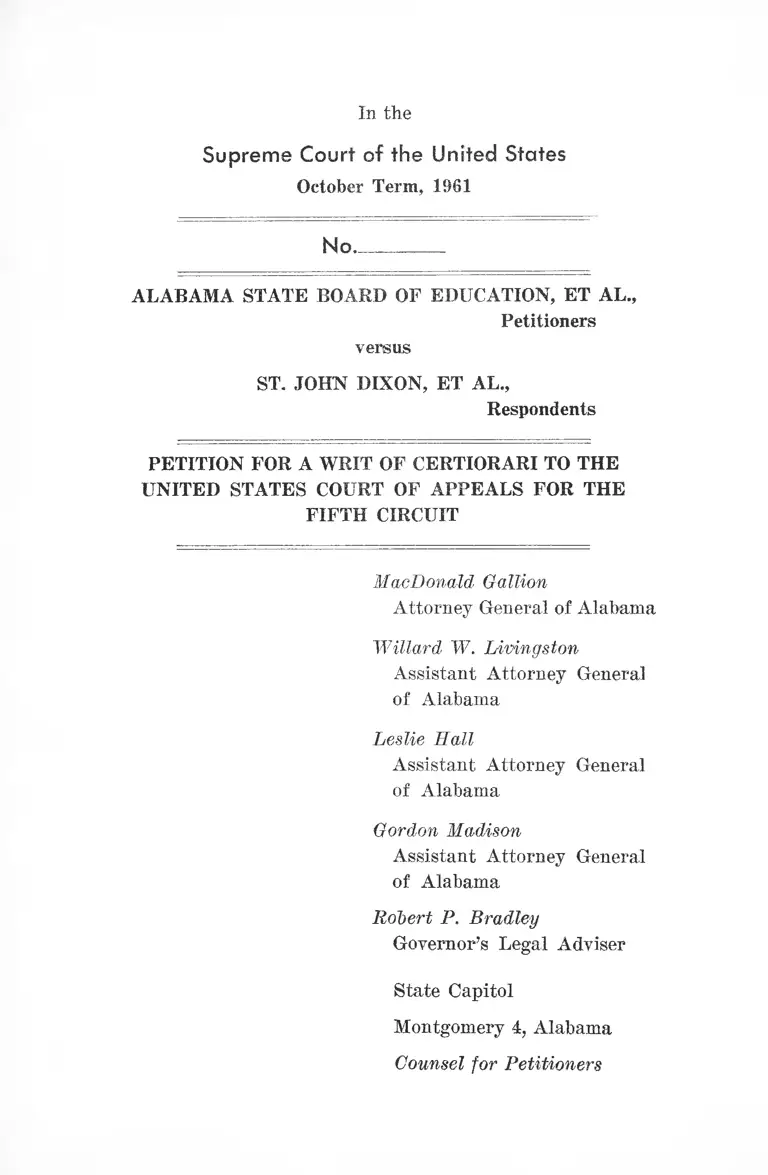

Alabama State Board of Education v. Dixon Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

August 4, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alabama State Board of Education v. Dixon Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1961. 47a56555-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/abd9ddb5-3a5e-4aa5-8fe8-56c79ec969f1/alabama-state-board-of-education-v-dixon-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1961

No.

ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.,

Petitioners

versus

ST. JOHN DIXON, ET AL.,

Respondents

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

MacDonald Gallion

Attorney General of Alabama

'Willard'■ W. Livingston

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Leslie Hall

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Gordon Madison

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Robert P. Bradley

Governor’s Legal Adviser

State Capitol

Montgomery 4, Alabama

Counsel for Petitioners

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1961

No__________

ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL.,

Petitioners

versus

ST. JOHN DIXON, ET AL.,

Respondents

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit entered in the above-entitled cause on August

4, 1961.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the District Court (R. p. 208) is reported

in 186 F. Supp. 945. The opinion of the Court of Appeals

is appended hereto.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

August 4, 1961 (E, p. 283). The jurisdiction of this Court

is invoked under Title 28, United States Code, Section

1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether due process requires in all cases notice and

some opportunity for hearing before students at a tax-

supported college are expelled for misconduct (R. p. 249).

2. Whether tax supported colleges and universities are free

2

to make their own reasonable rules relative to separating

students from said colleges and universities.

STATEMENT

In the present posture of this case, it is sufficient to state

that Respondents were expelled from Alabama State College,

a college for Negroes, by the Alabama State Board of Educa

tion for misconduct described by the District Court as fol

lows :

“The Court further finds and concludes in this case that

the conduct of these plaintiffs and other students of the

Alabama. State College from February 25, 1960, until they

were expelled or probated on March 5, 1960, in organizing,

leading and actively participating in the several demon

strations, was calculated to provoke and did provoke dis

cord, disorder, disturbance and disruption on the campus

of the college and in the college classrooms, generally. This

Court further finds and concludes that the conduct of these

plaintiffs in persisting after warning by the president of

the college was flagrantly in violation of the college rules

and regulations, was prejudicial to the school, constituted

insubordination, resulted in inciting other pupils to like

conduct, and in general, was conduct unbecoming a student

or future teacher in the schools . . . ” (B. p. 222)

The nature of the demonstrations are fully set forth in

the majority and dissenting opinions of the Court of Appeals.

The Respondents were expelled by the Alabama State

Board of Education for said misconduct, without notice or

hearing.

REASONS FOR ALLOWANCE OF THE WRIT

The opinion of the Court of Appeals affects and applies to

every tax supported college or university in the United

States.

3

Here, clearly, the right of the State of Alabama acting

through its agency, the Alabama State Board of Education,

is paramount to any alleged constitutional rights of Respon

dents.

Due process, unlike some legal rules, is not a technical

conception with a fixed content unrelated to time, place, and

circumstances.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals majority requires

notice and hearing before expulsion from a tax-supported

college in every conceivable case, regardless of the facts of

each.

Applying the law as declared by the Court of Appeals

would require notice and hearing before expulsion in the fol

lowing cases where the student, white or Negro, had confessed

to :

(a) Participating in panty raids

(b) Raping a co-ed.

(c) Murder

(d) Theft

(e) Defying order of a court relative to integration

(f) Having a contagious veneral disease

(g) Falsely charging fraud and misconduct against col

lege authorities in integration suits

This Court can think of many other cases.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is unrealistic and

apparently without knowledge of everyday campus affairs

in these times.

4

To attempt to lay down a formula by which Petitioners

may meet the new “due process” declared by the Fifth Circuit

in its present opinion is, we submit, beyond the proper pro

cedure, even if the formula is correct.

Each college should make its own rules and should apply

them to the facts of the case before it, “and that the function

of a court would be to test their validity if challenged in a

proper court proceedings” (B. p. 280).

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the reasons stated and the importance of

the questions to every tax-supported college or university, it

is respectfully submitted that this petition should be granted.

Bespectfully submitted,

MacDonald Gallion

Attorney General of Alabama

Willard W. Livingston

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Leslie Hall

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Gordon Madison

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Robert P. Bradley

Governor’s Legal Adviser

State Capitol

Montgomery 4, Alabama

Counsel for Petitioners

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Gordon Madison, one of the attorneys of record for

Petitioners, hereby certify that I have on this th e ....................

day of October, 1961, mailed copies of the foregoing Petition

for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit to Respondents’ attorneys, Fred D.

Gray, 34 North Perry Street, Montgomery, Alabama, and

Thurgood Marshall, Jack Greenberg, and Derrick A. Bell,

Jr., all of 10 Columbus Circle, New York, New York.

Gordon Madison

6

APPENDIX

OPINION OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

ENTERED ON AUGUST 4, 1961

RIVES', Circuit Judge: Tlie question presented by the

pleadings and evidence,1 and decisive of this appeal, is

whether due process requires notice and some opportunity

for hearing before students at a tax-supported college are

expelled for misconduct. We answer that question in the

affirmative.

The misconduct for which the students were expelled has

never been definitely specified. Defendant Trenholm, the

i The com plain t alleges th a t “D efendan t T renho lm on M arch 4, 1960,

no tified p la in tiffs of th e ir expulsion effective M arch 5, 1960,

w ith o u t any notice, hearing , o r appeal,” and fu r th e r avers:

“E xpulsion from A labam a S ta te College cam e w ith o u t

w arn ing , notice of charges, o p p o rtun ity to ap p ea r before

defendan ts or a t any o ther hearing , o p p o rtun ity to offer te s t i

m ony in defense, c ro ss-exam ina tion of accusers, appeal, o r

o ther o p p o rtun ity to defend p la in tiff’s rig h t no t to b e a rb i

tr a r ily expelled from defen d an t College. D efendan ts’ expu lsion

order, issued b y th e defendan ts function ing u n d e r th e s ta tu tes ,

law s and regu la tions of th e S ta te of A labam a, th e reb y deprived

p la in tiffs of righ ts p ro tec ted by th e due process clause of th e

F o u rteen th A m endm ent to th e U nited S ta tes C onstitu tion .”

To th is av erm en t th e defendan ts respond:

“ . . . th a t th e facts set fo r th in p la in tiffs ’ com plain t

show no v io lation of th e due process clause of th e F o u r

te en th A m endm ent to th e C onstitu tion of th e U n ited S tates;

th a t p la in tiffs have no constitu tional rig h t to a tten d A labam a

S ta te College; th a t th e facts sta ted by p la in tiffs in th e ir com

p la in t show th a t th is C ourt is w ith o u t ju risd ic tion fo r no

a rb itra ry action is alleged except as conclusions unsuppo rted

by th e facts alleged; th a t th e defendan ts de term ined in good

fa ith and w ith in th e ir au th o rity as th e govern ing au tho rities

of A labam a S ta te College th a t th e expulsions of th e p la in tiffs

w ere fo r th e best in te rests of the college and based upon u n

dispu ted conduct of p la in tiffs w h ile studen ts a t said college.”

As w ill ap p ea r la te r in th is opinion, th e issue th u s square ly

p resen ted by the p lead ings w as fu lly developed in th e evidence.

7

President of the College, testified that he did not know

why the plaintiffs and three additional students were ex

pelled and twenty other students were placed on probation.

The notice of expulsion2 which Dr. Trenholm mailed to

2 L e tte r from A labam a S ta te College, M ontgom ery, A labam a, da ted

M arch 4, 1960, signed b y H. C ouncil! T renholm , P residen t:

“D ear Sir:

T his com m unication is th e officia l no tifica tion of you r e x

pu lsion from A labam a S ta te College as of th e end of th e 1960

W in ter Q uarter.

“As rep o rted th rough th e various new s m edia, The S ta te

B oard of E ducation considered th is prob lem of A labam a S ta te

College a t its m eeting on th is p a s t W ednesday afternoon . You

w ere one of th e studen ts involved in th is expu ls ion -d irec tive

by th e S ta te B oard of E ducation. I w as d irec ted to proceed

accordingly.

“On F rid ay of las t w eek, I had m ade th e recom m endation

th a t any subsequen tly -con firm ed action w ould no t b e e f

fec tive u n til th e close of th is 1960 W in ter Q u a rte r so th a t

each s tu d en t could th u s have the o p p o rtun ity to tak e th is

q u a r te r’s exam inations and to q ua lify fo r as m uch O H -P t

cred it as possible fo r th e 1960 W in ter Q uarter.

“The S ta te B oard of E ducation , w h ich is m ade responsible

fo r the superv ision of th e six h igher in s titu tions a t M ontgom ery,

N orm al, F lorence, Jacksonville , L ivingston, and T roy (each of

th e o ther th ree in stitu tions a t Tuscaloosa, A uburn and M onte-

vallo hav ing separa te boards) includes th e follow ing in its

regu la tions (as ca rried in page 32 of T he 1958-59 R eg istra tion -

A nnouncem ent of A labam a S ta te College):

“ ‘ P up ils m ay be expelled from any of th e Colleges:

“ ‘a. F o r w illfu l disobedience to th e ru les and re g u

lations estab lished fo r th e conduct of th e schools.

“ ‘b. F o r w illfu l and continued neglec t of stud ies and

continued fa ilu re to m a in ta in th e stan d ard s of efficiency

req u ired b y th e ru le s and regulations.

“ ‘c. FO R CONDUCT PR E JU D IC IA L TO THE SCHOOL

AND FO R CONDUCT UNBECOM ING A STUDENT OR

FU TU RE TEACHER IN SCHOOLS OF ALABAM A, FOR

IN SU BO RD IN ATIO N AND IN SURRECTIO N, OR FOR

IN C ITIN G OTHER PU P IL S TO L IK E CONDUCT.

“ ‘d. F o r any conduct involving m ora l tu rp itu d e .’ ”

In th e notice received b y each of th e studen ts p a rag rap h “c,”

ju s t quoted, w as capitalized.

8

each of the plaintiffs assigned no specific ground for ex

pulsion, but referred in general terms to “this problem of

Alabama State College.”

The acts of the students considered by the State Board

of Education before it ordered their expulsion are de

scribed in the opinion of the district court reported in 186

F. Supp. 945, from which we quote in the margin.3

s “On th e 25th day of F eb ru a ry , 1960, th e six p la in tiffs in th is case

w ere s tuden ts in good stand ing a t th e A labam a S ta te College fo r

N egroes in M ontgom ery, A labam a . . . On th is date, a p p ro x i

m ate ly tw en ty -n in e N egro s tuden ts, inc lud ing these six p la in tiffs ,

according to a p rea rran g ed p lan , en te red as a group a pub lic ly

ow ned lunch g rill located in th e basem en t of th e county C o u rt

house in M ontgom ery, A labam a, and asked to be served. Service

w as refused ; th e lunchroom w as closed; th e N egroes refu sed to

leave; police au tho rities w e re sum m oned; and th e N egroes w ere

o rdered outside w h ere they rem ain ed in th e co rrido r of th e C o u rt

house fo r app ro x im ate ly one hour. O n th e sam e date , Jo h n P a t te r

son, as G overnor of th e S ta te of A labam a and as ch a irm an of th e

S ta te B oard of E ducation , conferred w ith Dr. T renholm , a N egro

ed uca to r and p res iden t of th e A labam a S ta te College, concern

ing th is ac tiv ity on th e p a r t of some of th e studen ts. D r. T re n

holm w as advised by th e G overnor th a t th e inciden t should be

investiga ted , and th a t if he w ere in th e p res id en t’s position h e

w ou ld consider expu lsion a n d /o r o th e r ap p ro p ria te d isc ip linary

action. O n F eb ru a ry 26, 1960, severa l h u n d red N egro studen ts from

th e A labam a S ta te College, includ ing severa l if no t a ll of these

p la in tiffs , staged a m ass a ttendance a t a tr ia l being held in th e

M ontgom ery C ounty C ourthouse, involving th e p e rju ry p rosecu tion

of a fellow studen t. A fte r th e tr ia l these studen ts filed tw o b y tw o

from th e C ourthouse and m arched th ro u g h th e city approx im ate ly

tw o m iles back to th e college. On F e b ru a ry 27, 1960, severa l

h u n d red N egro studen ts from th is school in c lu d in g severa l if n o t

a ll of th e p la in tiffs in th is case, staged m ass dem onstrations in

M ontgom ery and Tuskegee, A labam a. O n th is sam e date, Dr.

T renho lm advised all of th e stu d en t body th a t these dem onstrations

and m eetings w ere d isrup ting the o rderly conduct of the b u s i

ness a t th e college and w ere affecting th e w ork of o th er studen ts

as w ell as w ork of th e p a rtic ip a tin g s tuden ts. D r. T renho lm

personally w arn ed p la in tiffs B ern a rd Lee, Jo seph P e te rso n and

E lroy E m bry, to cease these d isrup tive dem onstra tions im m ediately ,

and advised th e m em bers of th e s tuden t body a t th e A labam a

S ta te College to behave them selves and re tu rn to th e ir classes . . .

“On or about M arch 1, 1960, approx im ate ly six h u n d red

9

As shown by the findings of the district court, just quot

ed in footnote 3, the only demonstration which the evidence

showed that all of the expelled students took part in was

that in the lunch grill located in the basement of the Mont

gomery County Courthouse. The other demonstrations were

found to be attended “by several if not all the plaintiffs.”

We have carefully read and studied the record, and agree

with the district court that the evidence does not affirma

tively show that all of the plaintiffs were present at any but

the one demonstration.

Only one member of the State Board of Education as

signed the demonstration attended by all of the plaintiffs

as the sole basis for his vote to expel them. Mr. Harry

Ayers testified:

“Q. Mr. Ayers, did you vote to expel these negro

students because they went to the Court House and

asked to be served at the white lunch counter?

“A. No. I voted because they violated a law of Ala

bama.

“Q. What law of Alabama had they violated?

“A. That separating of the races in public places of

that kind.

“Q. And the fact that they went up there and re

quested service, by violating the Alabama law, then

studen ts of th e A labam a S ta te College engaged in h ym n singing

and speech m ak ing on th e steps of th e S ta te C apitol. P la in tiff

B ern a rd L ee addressed s tu d en ts a t th is dem onstration , and th e

dem onstra tion w as a tten d ed b y severa l if no t all of th e p la in tiffs .

P la in tiff B ern a rd L ee a t th is tim e called on th e studen ts to s tr ik e

and boyco tt th e college if any s tu d en ts w ere expelled because of

these dem onstra tions.”

10

you voted to have them expelled?

“A. Yes.

“Q. And that is your reason why you voted?

“A. That is the reason.”

The most elaborate grounds for expulsion were assigned in

the testimony of Governor Patterson:

“Q. There is an allegation in the complaint, Gover

nor, that — I believe it is paragraph six, the de

fendants’ action of expulsion was taken without regard

to any valid rule or regulation concerning student

conduct and merely retaliated against, punished, and

sought to intimidate plaintiffs for having lawfully

sought service in a publicly owned lunch room with

service; is that statement true or false?

“.A Well, that is not true; the action taken by the

State Board of Education was — was taken to pre

vent — to prevent incidents happening by students at

the College that would bring — bring discredit upon

— upon the School and be prejudicial to the School,

and the State — as I said before, the State Board of

Education took — considered at the time it expelled

these students several incidents, one at the Court

House at the lunch room demonstration, the one the

next day at the trial of this student, the marching on

the steps of the State Capitol, and also this rally

held at the church, where — where it was reported

that — that statements were made against the ad

ministration of the School. In addition to that, the

— the feeling going around in the community here

due to — due to the reports of these incidents of the

students, by the students, and due to reports of in-

11

eidents occurring involving violence in other States,

which happened prior to these things starting here in

Alabama, all of these things were discussed l>y the

State Board of Education prior to the taking of the

action that they did on March 2, and as I was present

and acting as Chairman, as a member of the Board,

I voted to expel these students and to put these others

on probation because I felt that that was what was in

the best interest of the College. And the — I felt that

the action should be — should be prompt and immed

iate, because if something — something had not been

done, in my opinion, it would have resulted in violence

and disorder, and that we wanted to prevent, and we

felt that we had a duty to the — to the — to the par

ents of the students and to the State to require that

the students behave themselves while they are attend

ing a State College, and that is (sic) the reasons why

we took the action that we did. That is all.”

Superintendent of Education Stewart testified that he

voted for expulsion because the students had broken rules

and regulations pertaining to all of the State institutions,

and, when required to be more specific, testified:

“The Court: What rule had been broken is the ques

tion, that justified the expulsion insofar as he is con

cerned?

“A. I think demonstrations without the consent of the

president of an institution.”

The testimony of other members of the Board assigned

somewhat varying and differing grounds and reasons for

their votes to expel the plaintiffs.

The district court found the general nature of the pro

ceedings before the State Board of Education, the action of

12

the Board, and the official notice of expulsion given to the

students as follows:

“Investigations into this conduct were made by

Dr. Trenholm, as president of the Alabama State

College, the Director of Public Safety for the State

of Alabama under directions of the Governor, and

by the investigative staff of the Attorney General for

the State of Alabama.

“ On or about March 2, 1960, the State Board of

Education met and received reports from the Gov

ernor of the State of Alabama, which reports embodied

the investigations that had been made and which re

ports identified these six plaintiffs, together with

several others, as the ‘ring leaders’ for the group of

students that had been participating in the above-

recited activities. During this meeting, Dr. Tren

holm, in his capacity as president of the college, re

ported to the assembled members of the State Board

of Education that the action of these students in dem

onstrating on the college campus and in certain down

town areas was having a disruptive influence on the

work of the other students at the college and upon the

orderly operation of the college in general. Dr. Tren

holm further reported to the Board that, in his opinion,

he as president of the college could not control future

disruptions and demonstrations. There were twenty-

nine of the Negro students identified as the core of the

organization that was responsible for these demonstra

tions. This group of twenty-nine included these six

plaintiffs. After hearing these reports and recommen

dations and upon the recommendation of the Gover

nor as chairman of the Board, the Board voted unani

mously, expelling nine students, including these six

plaintiffs, and placing twenty students on probation.

13

This action was taken by Dr. Trenholm as president

of the college, acting pursuant to the instructions of

the State Board of Education. Each of these plain

tiffs, together with the other students expelled, was

officially notified of his expulsion on March 4th or

5th, I960.4 No formal charges were placed against

these students and no hearing was granted any of

them prior to their expulsion.”

“4[Same as footnote 2, supra, of this opinion.]”

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, M.D. Ala.,

1960, 186 F. Supp. 945, 948, 949.

The evidence clearly shows that the question for decision

does not concern the sufficiency of the notice or the adequacy

of the hearing, but is whether the students had a right to

any notice or hearing whatever before being expelled.4

* The p la in tiff D ixon testified :

“Q. Now on th a t day — from F eb ru a ry 25 u n til th e da te

th a t you received yo u r le tte r of expulsion, w hich you have

a lready iden tified , w ill you te ll th e C ourt w h e th e r any person

a t th e College gave you any officia l no tice th a t y o u r conduct

w as unbecom ing as a stu d en t of A labam a S ta te College?

“A. No.

“Q. Did th e p res id en t or an y o th er person a t th e College

a rran g e fo r any ty p e of h earin g w h ere you h ad an oppor

tu n ity to p resen t your side p rio r to th e tim e you w ere e x

pelled?

“A. No.

“Q. Y our answ er w as no?

“A. No.”

The testim ony of G overnor P a tte rson , C hairm an of th e S ta te

B oard of E ducation , w as in accord:

“Q. Did th e S ta te B oard of E ducation , p r io r to th e tim e it

expelled th e p la in tiffs , give them an o p p o rtun ity to appear

e ith e r befo re th e College o r before th e B oard in o rd e r to

p resen t th e ir sides of th is pic — of th is incident?

“A. No. o th e r th a n receiv ing the rep o rt from Dr. T renholm

about it.

14

The district court wrote at some length on that question, as

appears from its opinion. Dixon v. Alabama State Board

of Education, supra. 186 F. Supp. at pp. 950-952. After

careful study and consideration, we find ourselves unable

to agree with the conclusion of the district court that no

notice or opportunity for any kind of hearing was required

before these students were expelled.

It is true, as the district court said, that “ . . . there

is no statute or rule that requires formal charges and/or

a hearing . . . , ” but the evidence is without dispute that

the usual practice at Alabama State College had been to

give a hearing and opportunity to offer defenses before

expelling a student. Defendant Trenholm, the College Presi

dent, testified:

“Q. The essence of the question was, will you relate

“ Q. D id th e B oard d irec t D r. T renho lm to give th e s tu

den ts fo rm al notice of w hy th ey w ere expelled?

“A. No, th e B oard — th e B oard passed a reso lu tion in

s tru c tin g D r. T renho lm to ex p e l th e studen ts and p u t tw en ty

on p robation , and D r. T renho lm ca rried th a t ou t.”

S ta te S u p erin ten d en t of E ducation S tew art testified:

“Q. W ere these s tuden ts given any ty p e of hearing , or w ere

fo rm al charges filed against them befo re they w ere expelled?

“A. T hey w ere — Dr. T renho lm expelled th e studen ts; th ey

w e ren ’t g iven any hearing .

“Q. No hearing?

“A. I don’t th in k th ey w ou ld be g iven a h earin g in an y of

ou r schools in th is S tate; if th ey couldn’t behave them selves,

I th in k th ey should go hom e.

“Q. Do you — w ere they w arn ed a t a ll p rio r to expulsion?

“A. N ot as I know of; I can’t answ er th a t question . D r.

T renho lm w as in th e m eeting, and th a t afternoon a fte r th e

B oard m eeting, h e w as g iven th e — th e decision, and he w as

th e one w ho took action.

“Q. W hen th e S ta te B oard of E ducation expe ls a studen t,

is th e re any possib ility of appeal or any oppo rtun ity fo r h im to

p resen t h is side of th e story?

“A. I nev er have h ea rd of it .”

15

to the Court the usual steps that are taken when a

student’s conduct has developed to the point where

it is necessary for the administration to punish him

for that conduct?

“A. We normally would have conference with the

student and notify him that he was being asked to

withdraw, and we would indicate why he was being-

asked to withdraw. That would be applicable to aca

demic reasons, academic deficiency, as well as to any

conduct difficulty.

“Q. And at this hearing ordinarily that you would

set, then the student would have a right to offer what

ever defense he may have to the charges that have

been brought against him?

“A. Yes.”

Whenever a governmental body acts so as to injure an

individual, the Constitution requires that the act be con

sonant with due process of law. The minimum procedural

requirements necessary to satisfy due process depend upon

the circumstances and the interests of the parties involved.

As stated by Mr. Justice Frankfurter concurring in Joint

Anti-Fascist Committee v. McGrath, 1951, 341 U. S. 123, 163:

“Whether the ex parte procedure to which the peti

tioners were subjected duly observed The rudiments

of fair play,’ . . . cannot . . . be tested by mere

generalities or sentiments abstractly appealing. The

precise nature of the interest that has been adversely

affected, the manner in which this was done, the

reasons for doing it, the available alternatives to the

procedure that was followed, the protection implicit

in the office of the functionary whose conduct is

16

challenged, the balance of hurt complained of and

good accomplished — these are some of the considera

tions that must enter into the judicial judgment.”

Just last month, a closely divided Supreme Court held

in a. case where the governmental power was almost ab

solute and the private interest was slight that no hearing

was required. Cafeteria and Restaurant. 1 i orko s Union

v. McElroy, et ah, U. S. m /s, Oct. Term 1960, No. 97, de

cided June 19, 1961. In that case, a short-order cook work

ing for a privately operated cafeteria on the premises of

the Naval Gun Factory in the City of Washington was

excluded from the Gun Factory as a security risk. S'o,

too, the due process clause does not require that an alien

never admitted to this Country he granted a hearing be

fore being excluded. K nauff v. Shaughnessy, 1950, 338

U. S. 537, 542, 543. In such case the executive power as

implemented by Congress to exclude aliens is absolute

and not subject to the review of any court, unless express

ly authorized by Congress. On the other hand, once an

alien has been admitted to lawful residence in the United

States and remains physically present here it has been

held that, “although Congress may prescribe conditions for

his expulsion and deportation, not even Congress may expel

him without allowing him a fair opportunity to be heard.”

Kwong Had Chew v. Colding, 1953, 344 U. b. 590, 59 1, o98.

It is not enough to say, as did the district court in the

present case, “The right to attend a public college or uni

versity is not in and of itself a constitutional right.” (186

F. Supp. at 950.) That argument was emphatically an

swered by the Supreme Court in the Cafeteria and Restau

rant Workers Union case, supra, when it said that the ques

tion of whether “ . . . summarily denying Rachel Brawner

access to the site of her former employment violated the

requirements of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amend-

17

ment . . . cannot be answered by easy assertion that, be

cause she had no constitutional right to be there in the first

place, she was not deprived of liberty or property by the

Superintendent’s action. 'One may not have a constitutional

right to go to Baghdad, but the Government may not pro

hibit one from going there unless by means consonant with

due process of law.’ ” As in that case, so here, it is neces

sary to consider “the nature both of the private interest

which has been impaired and the governmental power which

has been exercised.”

The appellees urge upon us that under a provision of the

Board of Education’s regulations the appellants waived

any right to notice and a hearing before being expelled for

misconduct,

“Attendance at any college is on the basis of a

mutual decision of the student’s parents and of the

college. Attendance at a particular college is volun

tary and is different from attendance at a public

school where the pupil may be required to attend a

particular school which is located in the neighbor

hood or district in which the pupil’s family may live.

Just as a student may choose to withdraw from a, par

ticular college at any time for any personally-deter

mined reason, the college may also at any time decline

to continue to accept responsibility for the supervision

and service to any student with whom the relation

ship becomes unpleasant and difficult.”

We do not read this provision to clearly indicate an in

tent on the part of the student to waive notice and a hear

ing before expulsion. If, however, we should so assume, it

nonetheless remains true that the State cannot condition

the granting of even a privilege upon the renunciation of

the constitutional right to procedural due process. See

18

Slochower v. Board of Education, 1956, 350 U. S. 551, 555;

Wieman v. Updegraff, 1952, 344 TJ. S. 183, 191, 192; United

Piddle Workers v. Mitchell, 1947, 330 IT. S . 75, 100 ; Shelton

v. Tucker, U. S. m/s, Oct. Term, 1960, No. 14. Only private

associations have the right to obtain a waiver of notice and

hearing before depriving a member of a valuable right. And

even here, the right to notice and a hearing is so funda

mental to the conduct of our society that the waiver must

be clear and explicit. Medical and Surgical Society of

Montgomery County v. Weatherby, 75 Ala. 248, 256-59. In

the absence of such an explicit waiver, Alabama has required

that even private associations must provide notice and a hear

ing before expulsion. In Medical and Surgical Society of

Montgomery County v. Weathering supra, it was held that a

physician could not be expelled from a medical society with

out notice and a hearing. In Local Union No. 57, etc. r.

Boyd, Ala., 1944, 16 Bo. 2d 705, 711, a local union was

ordered to reinstate one of its members expelled after a

hearing of which he had insufficient notice.

The precise nature of the private interest involved in

this case is the right to remain at a public institution of

higher learning in which the plaintiffs were students in

good standing. It requires no argument to demonstrate

that education is vital and, indeed, basic to civilized society.

Without sufficient education the plaintiffs would not be

able to earn an adequate livelihood, to enjoy life to the

fullest, or to fulfill as completely as possible the duties and

responsibilities of good citizens.

There, was no offer to prove that other colleges are open

to the plaintiffs. If so, the plaintiffs would nonetheless

be injured by the interruption of their course of studies in

mid-term. It is most unlikely that a public college would

accept a student expelled from another public college of

the same state. Indeed, expulsion may well prejudice the

student in completing his education at any other institution.

19

Surely no one can question that the right to remain at the

college in which the plaintiffs were students in good standing

is an interest of extremely great value.

Turning then to the nature of the governmental power

to expel the plaintiffs, it must be conceded, as was held

by the district court, that that power is not unlimited and

cannot he arbitrarily exercised. Admittedly, there must

be some reasonable and constitutional ground for expulsion,

or the courts would have a duty to require reinstatement.

The possibility of arbitrary action is not excluded by the

existence of reasonable regulations. There may be arbi

trary application of the rule to the facts of a particular

case. Indeed, that result is well nigh inevitable when the

Board hears only one side of the issue. In the disciplining

of college students there are no considerations of immediate

danger to the public, or of peril to the national security,

which should prevent the Board from exercising at least

the fundamental principles of fairness by giving the ac

cused students notice of the charges and an opportunity

to be heard in their own defense. Indeed, the example

set by the Board in failing so to do, if not corrected by the

courts, can well break the spirits of the expelled students

and of others familiar with the injustice, and do inestimable

harm to their education.

The district court, however, felt that it was governed

by precedent, and stated that, “the courts have consistent

ly upheld the validity of regulations that have the effect

of reserving to the college the right to dismiss students at

any time for any reason without divulging its reason other

than its being for the general benefit of the institution.”

With deference, we must hold that the district court has

simply misinterpreted the precedents.

The language above quoted from the district court is

based upon language found in 14 C. J. S., Colleges and Uni-

20

versifies, § 26, p. 1360, which, in turn, is paraphrased from

Anthony v. Syracuse University, 231 N. Y. Supp. 435, re

versing 223 1ST. Y. Supp. 797. (14 C. J. S., Colleges and

Universities, § 26, pp. 1360, 1363 note 70.) This case, how

ever, concerns a private university and follows the well-

settled rule that the relations between a student and a

private university are a matter of contract. The Anthony

case held that the plaintiffs had specifically waived their

rights to notice and hearing. See also Barber v. Bryn Mawr,

122 Atl. 220 (Pa., 1923). The precedents for public col

leges are collected in a recent annotation cited by the dis

trict court. 58 A.L.R. 2d 903-20. We have read all of the

cases cited to the point, and we agree with what the an

notator himself says: “The cases involving suspension or

expulsion of a student from a public college or university

all involve the question whether the hearing given to the

student was adequate. In every instance the sufficiency

of the hearing was upheld.” 58 A.L.R. 2d at p. 909. None

held that no hearing whatsoever was required. Two cases

not found in the annotation have held that some form of

hearing is required. In Commonwealth ex rel, H ill v.

McCauley, 3 Pa, Co. Ct. Rep. 77 (1886), the court went

so far as to say that an informal presentation of the charges

was insufficient and that a state-supported college must

grant a student a full hearing on the' charges before ex

pulsion for misconduct. In Gleason v. University of M in

nesota, 116 X. W. 650 (1908), on reviewing the overruling

of the state’s demurrer to a petition for mandamus for rein

statement, the court held that the plaintiff stated a prima

facie case upon showing that he had been expelled with

out a hearing for alleged insufficiency in work and acts of

insubordination against the faculty.

The appellees rely also upon Lucy v. Adams, D.C.N.D.

Ala., C. A. No. 652, January 1957, where Autherine Lucy

21

was expelled from the University of Alabama without notice

or hearing. That case, however, is not in point. Autherine

Lucy did not raise the issue of an absence of notice or hearing.

It was not a case denying any hearing whatsoever but one

passing upon the adequacy of the hearing,3 which provoked

from Professor Warren A. Seavey of Harvard the eloquent

comment:

“At this time when many are worried about dis

missal from public service, when only because of the

overriding need to protect the public safety is the

identity of informers kept secret, when we proudly

contrast the full hearings before our courts with

those in the benighted countries which have no due

process protection, when many of our courts are so

careful in the protection of those charged with crimes

that they will not permit the use of evidence illegally

obtained, our sense of justice should be outraged by

denial to students of the normal safeguards. It is

shocking that the officials of a state educational in

stitution, which can function properly only if our

freedoms are preserved, should not understand the

elementary principles of fair play. It is equally shock

ing to find that a court supports them in denying to

a student the protection given to a. pickpocket.”

Dismissal of Students: “Due Process,” Warren A. Seavey, 70

Harvard Law Review 1406, 1407. We are confident that

precedent as well as a most fundamental constitutional

principle support our holding that due process requires notice

and some opportunity for hearing before a student at a tax-

supported college is expelled for misconduct.

For the guidance of the parties in the event of further

s People ex re l. B lue tt v . B oard of T rustees of U n ivers ity of Illinois,

10 111. App. 2d 207, 134 N. E. 2d 635.

22

proceedings, we state our views on the nature of the notice

and hearing required by due process prior to expulsion from

a state college or university. They should, we think, com

ply with the following standards. The notice should con

tain a statement of the specific charges and grounds which,

if proven, would justify expulsion under the regulations

of the Board of Education. The nature of the hearing should

vary depending upon the circumstances of the particular

case. The case before us requires something more than an

informal interview with an administrative authority of the

college. By its nature, a charge of misconduct, as opposed

to a failure to meet the scholastic standards of the college,

depends upon a collection of the facts concerning the charged

misconduct, easily colored hv the point of view of the wit

nesses. In such circumstances, a hearing which gives the

Board or the administrative authorities of the college an

opportunity to hear both sides in considerable detail is best

suited to protect the rights of all involved. This is not to

imply that a full-dress judicial hearing, with the right to

cross-examine witnesses, is required. Such a hearing, with

the attending publicity and disturbance of college activities,

might be detrimental to the college’s educational atmosphere

and impractical to carry out. Nevertheless, the rudiments

of an adversary proceeding may be preserved without en

croaching upon the interests of the college. In the instant

case, the student should be given the names of the witnesses

against him and an oral or written report on the facts to

which each witness testifies. He should also he given the

opportunity to present to the Board, or at least to an ad

ministrative official of the college, his own defense against

the charges and to produce either oral testimony or written

affidavits of witnesses in his behalf. If the hearing is not

before the Board directly, the results and findings of the

hearing should he presented in a report open to the student’s

inspection. If these rudimentary elements of fair play are

23

followed in a case of misconduct of this particular type, we

feel that the requirements of due process of law will have

been fulfilled.

The judgment of the district court is reversed and the

cause is remanded for further proceedings consistent with

this opinion.

REVERSED AND REMANDED.

CAMERON, Circuit Judge, Dissenting:

The opinion of the district court in this case1 is so lucid,

literate and moderate that I cannot forego expressing sur

prise that my brethren of the majority can find fault with

it. In this dissent I shall try to avoid repeating what the

lower court has so well said and to confine myself to an ef

fort to refute the holdings of the majority where they do

attack and reject the lower court’s opinion.

A good place to start is the quotation made by the ma

jority from the recent case of Cafeteria and Restaurant

'Workers Union v. McElroy, 1961, 29 L. W. 4743, 4745 et seq.,

------ TT. S!. ------ , wherein the discussion is made of one’s

right to “go to Baghdad.” I would add to the language

quoted by the majority from that case the sentences which

follow it:

“It is the petitioner’s claim that due process in

this case required that Rachel Brawner be advised

of the specific grounds for her exclusion and be

accorded a hearing at which she might refute them.

We are satisfied, however, that under the circum

stances of this case such a procedure was not con

stitutionally required.

“The Fifth Amendment does not require a trial-

i 186 F. Supp. 945, 1960.

24

type hearing in every conceivable case of govern

ment impairment of private interests. ‘ . . . The very

nature of due process negates any concept of inflexible

procedures universally applicable to every imaginable

situation . . . . “Due process,” unlike some legal rules,

is not a technical conception with a fixed content un

related to time, place and circumstances.’ It is ‘com

pounded of history, reason, the past course of de

cisions . . . ’ Joint Anti-Fascist Comm. v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 123, 162-163 (concurring opinion).

“As these and other cases make clear, considera

tion of what procedure due process may require under

any given set of circumstances must begin with a de

termination of the precise nature of the government

function involved as well as of the private interest

that has been affected by governmental action. Where

it has been possible to characterize that private in

terest (perhaps in over-simplification) as a mere

privilege subject to the Executive’s plenary power, it

has traditionally been held that notice and hearing

are not constitutionally required . . . ”2 [Emphasis

added.]

2 T he d issen ting opinion in th a t case contains language w hich fu r

th e r illum ina tes th e p rob lem befo re us:

“ . . . B u t th e C ourt goes beyond th a t. I t ho lds th a t

th e m ere assertion b y governm en t th a t exclusion is fo r a

va lid reason forecloses fu r th e r inqu iry . T h a t is, un less th e

governm en t o fficia l is foo lish enough to adm it w h a t h e is

doing — and few w ill be so foolish a f te r to d ay ’s decision

— h e m ay em ploy ‘secu rity req u irem en ts’ as a b lin d beh ind

w hich to dism iss a t w ill fo r th e m ost d iscrim inato ry of

causes.

“Such a re su lt in effect nu llifies th e su b stan tiv e rig h t —•

no t to be a rb itra r ily in ju red b y governm ent — w hich th e

C ourt p u rp o rts to recognize. . . . F o r u n d e r to d ay ’s holding

pe titio n e r is en titled to no process a t all. She is n o t to ld

w h a t she did w rong; she is n o t g iven a chance to defend h e r -

25

The failure of the majority to follow the reasoning of

M cElroy, supra, results, in my opinion, from a basic failure

to understand the nature and mission of schools. The prob

lem presented is sui generis.

Everyone who has dealt with schools knows that it is

necessary to make many rules governing the conduct of

those who attend them, which do not reach the concept

of criminality but which are designed to regulate the re

lationship between school management and the student

based upon practical and ethical considerations which the

courts know very little about and with which they are not

equipped to deal. To extend the injunctive power of federal

courts to the problems of day to day dealings between school

authority and student discipline and morale is to add to the

now crushing responsibilities of federal functionaries, the

necessity of qualifying as a Gargantuan aggregation of wet

nurses or baby sitters. I do not believe that a balanced

consideration of the problem with which we are dealing con

templates any such extreme attitude. Indeed, I think that

the majority has had to adopt the minority view of the

courts in order to reach the determination it has here an

nounced.

Nor do I find of favorable (to the majority) significance

the introductory sentence quoted by it from the annotation

in 58 ALB. at page 909.3 The quoted statement implies,

self. She m ay be th e v ic tim of th e basest calum ny, perhaps

even th e caprice of th e governm en t officials in w hose pow er

h e r s ta tu s res ted com pletely. In such a case, I cannot believe

th a t she is n o t en titled to some procedures.

“ ‘[T ]h e rig h t to b e h ea rd befo re being condem ned to

su ffe r grievous loss of any k ind , even though i t m ay n o t in

volve th e stigm a and h ard sh ip s of a crim inal conviction, is a

p rinc ip le basic to ou r society.’ ” [C iting M cG rath, supra.]

3 The cases involving suspension or expulsion of a stu d en t from a

public college or u n iv e rsity all invo lve the question w h eth er the

h ea rin g g iven to th e stu d en t w as adequate . In every instance the

suffic iency of the hearing was upheld.” [E m phasis A dded.]

26

rather, that there is no case where a student at a public

college or university lias taken the position that he was

entitled to a hearing before being expelled. More in point,

it seems to me, is the addition to the text found on page

4 of the July 1961 pocket part of American Jurisprudence,

Yol. 55, § 22, page 16, of the article on Universities and

Colleges. I quote the closing sentences of 55 Am. Jur., § 22,

pp. 15-16 of that article, adding the paragraph appearing in

the pocket part:

. . Where the conduct of a student is such that

his continued presence in the school will be disas

trous to its proper discipline and to the morals of

the other pupils, his expulsion is justifiable. Only

where it is clear that such an action with respect to

a student has not been an honest exercise of dis

cretion, or has arisen from some motive extraneous

to the purposes committed to that discretion, may

the courts be called upon for relief.

“There is a conflict of authority as to whether

notice of the charges and hearing are required before

suspensions or expulsion of a student. Assuming that

a student is entitled to a hearing prior to his expul

sion from an institution of learning, the authorities

are not in agreement as to what kind of hearing must

be given to him. A few cases hold that he is entitled

to a formal hearing clothed with all the attributes

of a judicial hearing. However, the weight of author

ity is to the effect that no formal hearing is required.”

The general rule covering the subtitle “Government and

Discipline” in the general treatise on Colleges and Uni

versities is thus stated in the black-typed summary of the

law in Yol. 14 Corpus Juris Secundum, § 26, page 1360:

“Broadly speaking, the right of a student to at-

27

tend a public or private college or university is

subject to the condition that he comply with its

scholastic and disciplinary requirements, and the

proper college authorities may in the exercise of a

broad discretion formulate and enforce reasonable

rules and regulations in both respects. The courts

will not interfere in the absence of an abuse of such

discretion.”

All of these expressions of the general rule seem to me to

justify and require our adherence to that rule under the

facts of this case. The majority opinion sets out many of

them, but I think its statement should be supplemented and

set forth in chronological order.

Appellants and other members of the student body of

Alabama State College had, for a period prior to the hap

penings outlined, been attending meetings at Negro churches

and other places where outsiders, including professional

agitators, had been counseling that the students of that in

stitution engage in “demonstrations.” Appellants, along

with a total of between twenty-nine and thirty-five students

of the college, proceeded en masse into a snack bar in the

basement of the county court house at Montgomery, Ala

bama, seating themselves in the privately owned facility so as

to occupy nine tables. The lady in charge of the eating place

asked them to depart and they refused. Officers were called

and, upon their arrival, they first asked that all white patrons

leave the premises, which was promptly done. The Negroes

refused their request to leave until the lights were put out,

whereupon they proceeded to the hall of the court house.

Inasmuch as they were blocking ingress and egress there

from ,they were ordered by the officers to take their stands

against the walls, which they did. They remained in the court

house about one and one-half hours following their entrance

about 11:00 A. M. They refused to give their names to re-

28

porters who interviewed them. The occurrence took place

on February 25, 1960.

The president of the college, H. Councill Trenholm, in

vestigated the occurrence at the direction of the governor

of Alabama and made his report and recommendation to

the State Board of Education. About five o’clock on the

afternoon of the occurrence he had released a mimeographed

statement making an appeal to the students and staff that

they “refrain from any activities which may have a damag

ing effect upon the reputation and relationships of college

and . . . have concern that there not be any type of further

involvement of any identified student of Alabama State

College.” He reported that, from his investigation con

ducted on the campus, it was his opinion that twenty-nine

students who were the leaders in the activities he had in

vestigated were subject to expulsion.4

On February 26, 1960, several hundred students, including

appellants, staged another demonstration at the Montgomery

Court House by attending a trial where a fellow student was

charged with perjury to which he pled guilty. The several

hundred demonstrators marched around the court house and

then walked, two by two, back to the college about two

miles away. A snapshot received in evidence depicted a

mob-like gathering, on the college campus on the same day,

of a large number of students ganged about the college

president of thirty-five years tenure. The expressions on the

faces of the participants, including at least some of appel-

4 T he governor recom m ended, how ever, th a t only B e rn a rd Lee, N orfolk,

Va.; St. Jo h n D ixon, N ational City, Cal.; E dw ard E. Jones, P it ts

bu rg , Pa.; L eon Rice, Chicago, 111.; H ow ard Shipm an, N ew Y ork,

N.Y.; E lro y E m ory, R agland , A la.; Jam es M cFadden, P rich a rd , A la.;

Jo seph Peterson , N ew castle, A la.; M arzette W atts, M ontgom ery,

A la., be expelled a t th e end of th e cu rren t te rm and th a t th e r e

m a inder be p laced on p ro b a tio n and allow ed to rem a in in school

pend ing good behav io r.

29

hints, portrayed a group in the grip of anger, exhibiting a

threatening and menacing attitude. The scene spoke more

eloquently to the trial court of the spirit and attitude of the

appellants and the followers they had gathered than many

reams of oral testimony could have.

February 27, several hundred Negro college students, in

cluding appellants, staged mass demonstrations in Mont

gomery and Tuskegee, some of which were attended by

violence. On the same day a large group of students from

the college, including appellants, gathered at a Negro church

and one of appellants, Bernard Lee, filed a petition with the

governor in which it was stated, among other things: “We

strongly feel that our conduct was not. of such that we should

owe our college or state an apology. If our conduct lias

disturbed you or President Trenholm, we regret this. But we

have no sense of shame or regret for our conduct . . .”

On the same day the governor was advised by the college

president that he had called upon members of the student

body to behave themselves and return to classes and had

urged the students not to engage in conduct which might

cause racial disturbances. A like plea was made by the

Attorney General of Alabama both to white and colored

people. March 1, 1960, at about 8:00 A.M., approximately

six hundred students of the college marched to the steps of

the state capitol, where student leaders, including appel

lants, made addresses calling on all the students to boycott

and strike against the college if any students were expelled.

The gathering was policed by a number of the state of

ficials to prevent untoward incidents.

March 2, 1960, the State Board of Education met and

heard Dr. Trenholm’s report, ordering the nine students

mentioned above to be expelled and twenty to be placed on

probation. The Board had the benefit of reports made by

30

agents of the Department of Public Safety, which revealed

the names of the demonstrators and of their leaders, as well

as that of college president and of the governor who had

witnessed portions of the demonstrations.

March 3, 1960, the date of the expulsion order, about two

thousand Negro students staged a demonstration at a church

near the college campus at which appellants were the leaders.

They urged the students to refrain from returning to classes

and from registration for the new term, and publicly de

nounced the State Board and the college administration.

The students stayed away from classes and milled about the

campus in general disorder.

These events all transpired before the expulsion of ap

pellants. But the “demonstrations” did not cease. March

4, a wildly cheering crowd of Negro students gathered at a

church and were addressed by one or more agitators of

national prominence, and an appeal was made for a meet

ing the following Sunday on the steps of the state capitol.

At the meeting, one or more of appellants and a number of

other students were very critical of the governor and the

college administration.

March 5, 1960, appellant Bernard Lee, representing the

demonstrators, sent a telegram to the president of the

student body at Tuskegee urging them to join in the dem

onstrations.

March 6, 1960, several thousand Negroes, including ap

pellants and hundreds of the students of the college as

sembled near the steps of the capitol and approximately

ten thousand white people gathered in the same vicinity.

A large gathering of city and county officers and the use of

fire hose finally avoided an open clash between the two

groups. For a number of days following, there were demon-

31

stations on the campus of the college accompanied by some

violence and some arrests were made by the police.

March 11, the entire group which had initiated the dem

onstrations were convicted and fined. Several months later,

appellants and several other students were still engaged in

constant efforts to stir up trouble and dissension among the

students and faculty of the college.

After appellants were expelled a document signed by one

of them, on behalf of the executive committee of the student

body, issued a. public call to the student body of every school

in Alabama, in the South and in the nation to support the

appellants, and the same document called upon parents,

teachers and the people of the nation to give them support.

Each of the appellants had, in his application for admis

sion to the college, agreed in writing to abide by college

policies and regulations relating to admission, attendance,

conduct, withdrawal or dismissal.

A part of the foregoing recital is taken from the affidavit

of Governor Patterson of Alabama. It was attached to and

offered as a portion of the answer of appellees to the com

plaint and the motion for preliminary injunction. This

motion was considered along with all of the other motions

filed and with the hearing of witnesses and was included

in the order from which this appeal was taken. The affi

davit was competent evidence even in a court. Rule 43 (e)

F. R. C. P.

The opinion of the majority stresses that definite proof

was not made of the attendance of all of the appellants at

all of the “demonstrations” (the word is taken from the

testimony of the only appellant who testified in the court

below). I think that ample showing was made to establish

32

that the appellants were at all of the demonstrations and

were the ringleaders of them. They participated in the

enterprise as joint venturers from the start and every docu

ment emanating from them showed the adhesiveness of the

group.

It is interesting to find what the majority considers to he

the significance of an assumed absence of proof in the light

of the fact that only one of the appellants took the witness

stand in the court below, although they all announced at

the outset that they were ready for trial and manifestly

were present in court. Their presence and participation in

all which transpired was shown by believable evidence and

circumstances and stand wholly undenied. In a recent case

charging a fraudulent civil conspiracy against a defendant3

where the proof was very slim, this Court speaking through

Judge Hives, stated the rule as follows:

“Certainly, the proof was sufficient to make out

a prima facie case of appellant’s involvement in each

of the transactions and liability to respond civilly in

liquidated damages under the statute; . . . his failure

either to take the stand, or show that he was unable

to testify, or even to offer any excuse whatever for

his failure to testify in explanation of suspicious

facts and circumstances peculiarly within his know

ledge, fairly warrants the inference that his testimony,

if produced, would have been adverse.”

See to the same effect these additional cases from this Cir

cuit : United States v. Leveson, 1959, 262 F. 2d 659; United

States v. Marlowe, 1956, 235 F. 2d 366; Williams v. United

States, 1952, 199 F. 2d 921; Paudler v, Paudler, 1950, 185

s D aniel v. U n ited S tates, 1956, 234 F . 2d 102, 106, ce rtio ra ri denied,

352 U. S. 971.

33

F. 2d 901, certiorari denied, 341 U. S. 920; and United States

v. Priola, 1359, 272 F. 2d 589.

A fortiori, in an equity case where parties are seeking

the extreme remedy of injunction against state officers, it

does not lie in the mouths of appellants to decry the weak

ness of the opposition proof when they, having all the facts

in their possession, sit silently by when challenged by as

sertions which it behooved them to refute if they would

support their case. They were accused and convicted by

competent proof, including a picture and writings authored

by them, of public boorishness, of defying the authority

of the officials of their school and state, of blatant insub

ordination, of endeavoring to disrupt the school they had

agreed to support with loyalty, as well as to break up other

schools, and had openly incited to riot; and when their time

came to speak, they stood mute, offering only one of their

group along with the college president and two newspaper

reporters as witnesses.

Before they were notified of their expulsion they had

issued public statements admitting everything which was

the basis of their expulsion, and had disclosed everything

they could have brought forward in any hearing which

might have been given them before they were notified that

their conduct required their separation from connection with

the college. It is difficult to perceive the validity of the

argument that they were not given a hearing when, called

upon to refute proof offered against them and themselves

carrying the burden of proof throughout, they failed to say

a word in their defense.

We are trying here the actions of State officials, which

actions we are bound to invest with every presumption of

fairness and correctness. Certainly the Board had before it

a responsible and credible showing which justified their find-

34

ing that these appellants were guilty of wilful disobedience

of the rules and directives of the head of the college they

were attending and of conduct prejudicial to the school and

unbecoming a student or future teacher in the schools of

Alabama, as well as of insubordination and insurrection and

inciting other peoples to like conduct. It is undisputed

that the Board made a leisurely and careful investigation and

passed its judgment in entire good faith. The State of Ala

bama had no statute and the school had no rule or regulation

requiring any other hearing than that which was had, and

the Board was entirely justified in declining “to continue to

accept responsibility for the supervision and service to any

student with whom the relationship becomes unpleasant and

difficult.” It is worth noting, too, that President Trenholm,

testifying as a witness for appellants, stated that the rules

of the school had been in effect more than thirty years; and

that there was no requirement in them for notice or hearing

and that prior practices did not include such as a precedent.

It is undisputed that failure to act as the Board did act

would have resulted in a complete disruption of discipline

and probable breaking up of a school whose history ran

back many years, and whose president had held the position

for thirty-five years. If he and the School Boai*d had clone

less, they would, in my opinion, have been recreant to their

duties. The moderate action they took did bring order out

of chaos and enable the school to continue operation.

I do not feel that we are called upon here to volunteer our

ideas of procedure in separating students from state col

leges and universities. I think each college should make its

own rules and should apply them to the facts of the case

before it, and that the function of a court would be to test

their validity if challenged in a proper court proceeding.

A. sane approach to a problem whose facts are closely

35

related to the one before ns was made by the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in Steier v. N. Y.

State Education, Commission et at., 1959, 271 F. 2d 13. Its

attitude is thus epitomized on page 18:

“Education is a field of life reserved to the indi

vidual states. The only restriction the Federal Gov

ernment imposes is that in their educational pro

gram no state may discriminate against an individ

ual because of race, color or creed.

“As so well stated by Judge Wyzanski in Cranney

v. Trustees of Boston University, D. C., 139 F. Supp.

130, to expand the Civil Rights Statute so as to em

brace every constitutional claim such as here made

would in fact bring within the initial jurisdiction of

the United States District Courts that vast array of

controversies which have heretofore been raised in

state tribunals by challenges founded upon the 14th

Amendment to the United States. Constitution. It

would be arrogating to the United States District-

Courts that which is purely a State Court function.

Conceivably every State College student, upon dismis

sal from such college, could rush to a Federal Judge

seeking review of the dismissal.

“It is contrary to the Federal nature of our sys

tem — contrary to the concept of the relative places

of States and Federal Courts.

“Whether or not we would have acted as did the

Administrator of Brooklyn College in dismissing the

plaintiff matters not. For a Federal District Court

to take jurisdiction of a case such as this would lead

to confusion and chaos in the entire field of juris

prudence in the states and in the United States.”

36

Certainly I think that the filing of charges, the disclosure

of names of proposed witnesses, and such procedures as the

majority discusses are wholly unrealistic and impractical

and would result in a major blow to our institutions of

learning. Every attempt at discipline would probably lead

to a cause celebre, in connection with which federal func

tionaries would be rushed in to investigate whether a federal

law had been violated. I think we would do well to bear in

mind the words of Mr. Justice Jackson :6

“ . . . no local agency which is subject to federal

investigation, inspection, and discipline is a free

agency. I cannot say that our country could have

no central police without becoming totalitarian, but

I can say with great conviction that it cannot become

totalitarian without a centralized national police.”

I think, moreover, that, in these troublous times, those

in positions of responsibility in the federal government

should bear in mind- that the maintenance of the safety,

health and morals of the people is committed under our

system of government to the states. More than a hundred

years ago Chief Justice Marshall7 stated the principle in

these words:

“The power to direct the removal of gunpowder

is a branch of the police power, which unquestion

ably remains, and ought to remain, with the states.”

I dissent.

s “T he S uprem e C ourt in th e A m erican System of G overnm en t,” p.

70.

7 B row n v. M ary land , 1827, 12 W h e a t, 419.

A dm . Office, U. S. C ourts — Scofields’ Q uality P trs . Inc., N. O., La.

37

JUDGEMENT OF THE COURT OF APPEALS

ENTERED ON AUGUST 4, 1961

“This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of the

record from the United States District Court for the Middle

District of Alabama, and was argued by counsel;

“On CONSIDERATION WHEREOF, It is now here

ordered and adjudged by this Court that the judgment of the

said District Court in this cause be, and the same is hereby,

reversed ; and that this cause be, and it is hereby remanded

to the said District Court for further proceedings consistent

with the opinion of this Court;

“It is further ordered and adjudged that the appellees,

Alabama State Board of Education, and others, be con

demned, in solido, to pay the costs of this cause in this Court

for which execution may be issued out of the said District

Court,

“Cameron, Circuit Judge, Dissenting.”