Defense Fund Challenges Segregation in Beaufort County, N.C. Schools

Press Release

February 24, 1966

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 3. Defense Fund Challenges Segregation in Beaufort County, N.C. Schools, 1966. 4bff28cc-b692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/abeebe66-9947-459e-8512-bfe288cd9f76/defense-fund-challenges-segregation-in-beaufort-county-nc-schools. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

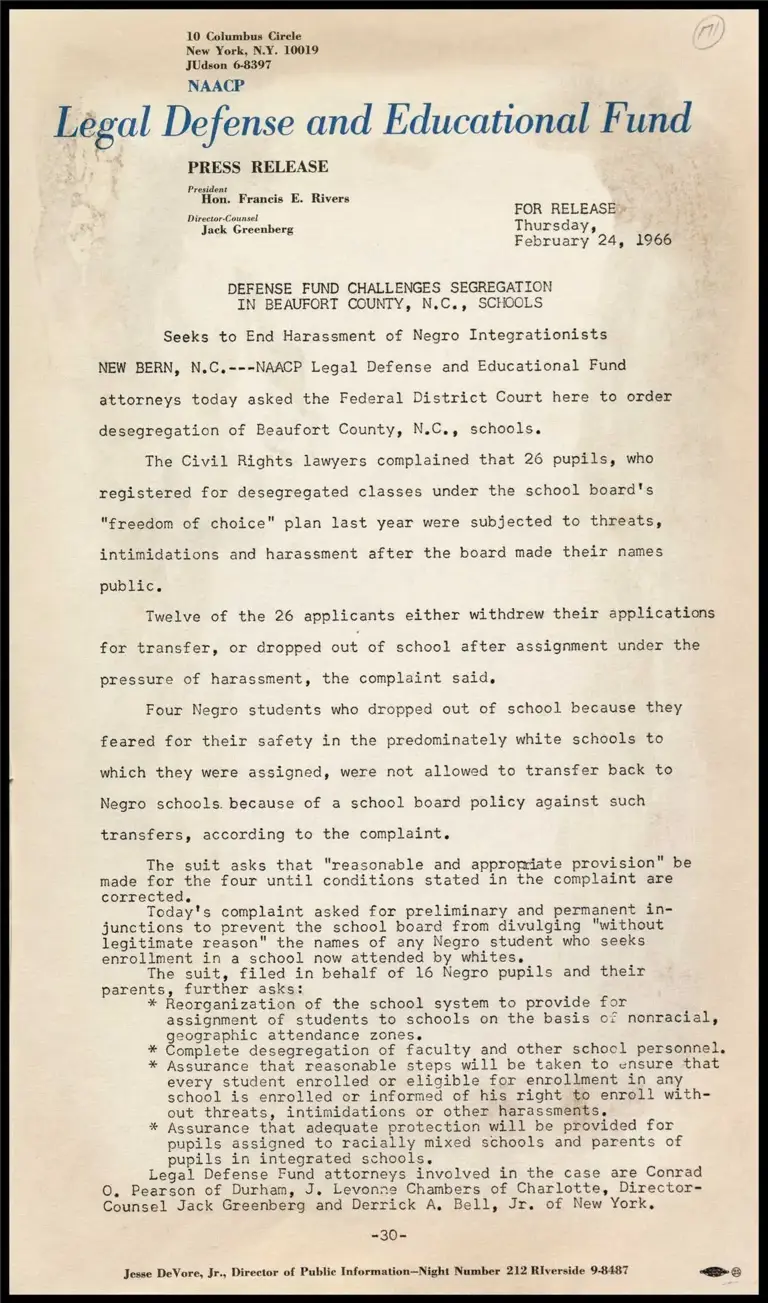

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

President : =

Hon. Francis E. Rivers

Director-Counsel FOR RELEASE

Jack Greenberg Thursday,

February 24, 1966

DEFENSE FUND CHALLENGES SEGREGATION

IN BEAUFORT COUNTY, N.C., SCHOOLS

Seeks to End Harassment of Negro Integrationists

NEW BERN, N.C,---NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund

attorneys today asked the Federal District Court here to order

desegregation of Beaufort County, N.C., schools.

The Civil Rights lawyers complained that 26 pupils, who

registered for desegregated classes under the school board's

"freedom of choice" plan last year were subjected to threats,

intimidations and harassment after the board made their names

public.

Twelve of the 26 applicants either withdrew their applications

for transfer, or dropped eres of school after assignment under the

pressure of harassment, the complaint said.

Four Negro students who dropped out of school because they

feared for their safety in the predominately white schools to

which they were assigned, were not allowed to transfer back to

Negro schools. because of a school board policy against such

transfers, according to the complaint.

The suit asks that "reasonable and appropriate provision" be

made for the four until conditions stated in the complaint are

corrected.

Today's complaint asked for preliminary and permanent in-

junctions to prevent the school board from divulging "without

legitimate reason" the names of any Negro student who seeks

enrollment in a school now attended by whites.

The suit, filed in behalf of 16 Negro pupils and their

parents, further asks:

* Reorganization of the school system to provide for

assignment of students to schools on the basis of nonracial,

geographic attendance zones.

* Complete desegregation of faculty and other school personnel.

* Assurance that reasonable steps will be taken to ensure that

every student enrolled or eligible for enrollment in any

school is enrolled or informed of his right to enroll with-

out threats, intimidations or other harassments,.

Assurance that adequate protection will be provided for

pupils assigned to racially mixed schools and parents of

pupils in integrated schools.

Legal Defense Fund attorneys involved in the case are Conrad

©. Pearson of Durham, J. Levonne Chambers of Charlotte, Director-

Counsel Jack Greenberg and Derrick A. Bell, Jr. of New York,

=20=

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 Riverside 9-8487 So