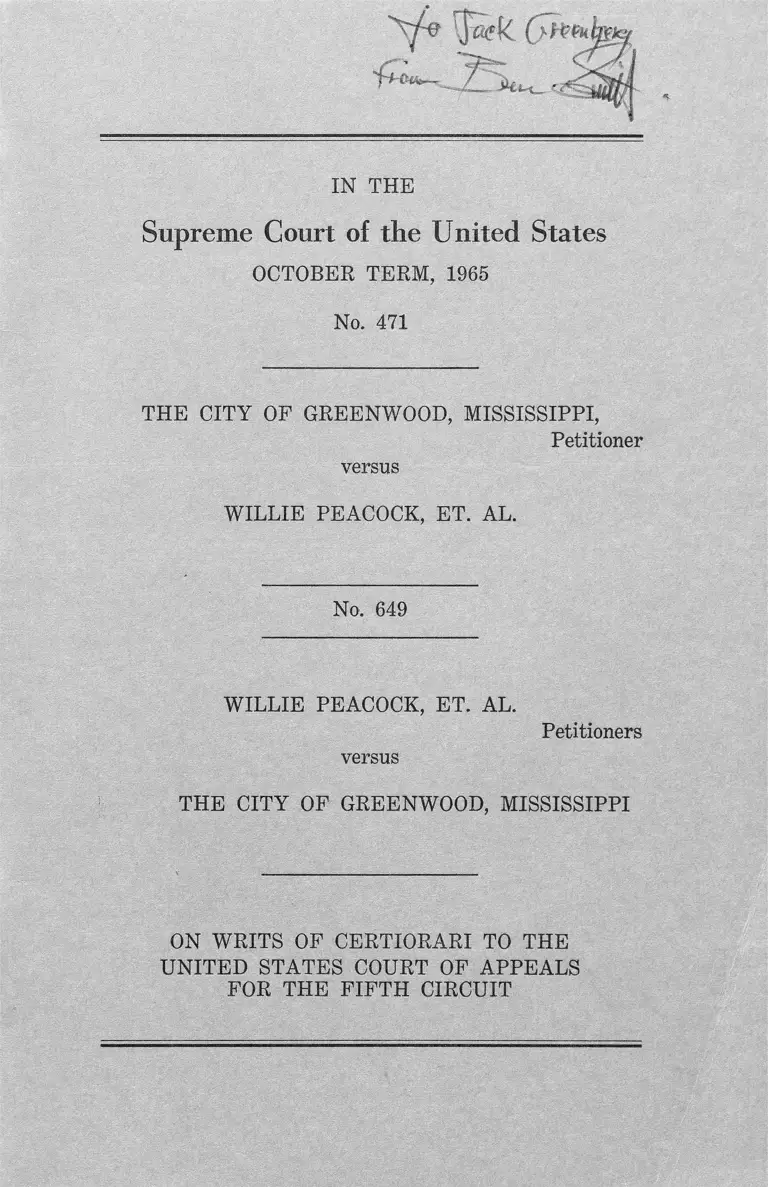

City of Greenwood, MS v. Peacock On Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Greenwood, MS v. Peacock On Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1966. 5523e2a6-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/abf790b5-b2f3-40f0-acec-2d15ca26e9e1/city-of-greenwood-ms-v-peacock-on-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

K6«

f t -0 « s 7 ^ ”

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1965

No. 471

THE CITY OF GREENWOOD, MISSISSIPPI,

Petitioner

versus

WILLIE PEACOCK, ET. AL.

No. 649

WILLIE PEACOCK, ET. AL.

Petitioners

versus

THE CITY OP GREENWOOD, MISSISSIPPI

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

I. Opinions Below ________________________ 1

II. Jurisdiction ____________________________ 2

III. Constitutional Provisions and

Statutes Involved ______________________ 2

IY. Questions Presented ___________ 4

V. Statement of the Case----------------------------- 5

VI. Argument

A) Point I A.)

(Racially Motivated Arrest and Charge) ---- 9

B) Point I B.)

(Sufficiency of the Pleadings) -------------------- 13

C) Point II A.)

(Unconstitutional Application of Jury

Statutes) _____________________________ 16

1) Historical Background ------ 18

2) Construction Problems ____________ 22

3) Supremacy Applies _______________ 24

4) Problems of Judicial Administration.... 27

29

I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

5) Abstention in Disguise

II

D) Point II B.)

(The Jury Statutes as written are Uncon

stitutional)

1) Rives and Powers Apply __________ 32

2) Franchise Connections and Women__ 35

3) Does Mississippi have a real jury

system ______________________ -___ 36

E) Point III

(Does 28 USC Section 1443(2) apply)

1) Who are “other persons” and what is a

“Posse Comitatus” _________________ 37

2) What the refusal to act “ineonsistant”

with the 14th Amendment means ------- 40

VII. Conclusion _____________________________ 43

VIII. Certificate ---------------- 45

TABLE OE CONTENTS (Continued)

Page

I ll

Baggett vs. Bullitt, 377 US 360, 84 S. Ct. 1316, 12

TABLE OF CASES

Page

L. Ed. 2d 377 _____________________________ 30

Baines, et al vs. Danville, et al (C. A. 4)

(unreported January 21st, 1966) _____________ 23

Baker vs. Carr, 369 US 186 (1961) ___________ 24, 29

Brown vs. Board of Education 347 US

483 (1954) ________________..._______ 24, 27, 34

Brown vs. Louisiana No. 41 October Term (1966) __ 11

Bush vs. Orleans Parish School Board, 364 US 50,

815 S. Ct. 260, 5 L. Ed. 245 (194

F. Supp. 182) __________________________ 11, 26

Clarksdale vs. Gertge, 237 F. Supp. 213 (1964) ____ 12

Cooper vs. Hutchinson (C. A. 3) 184 F. 2d

119 (1958) _______________________________ 30

Cox vs. Louisiana, 379 US 536 (1965) ____________ 12

Davis vs. Manu, 377 US 678 12 L. Ed. 2d 609, 84

S. Ct. 1453 ________________________________ 30

Dombrowski vs. Pfister, 227 F. Supp.

556 (1964) __________________ _____ 25, 26, 27

Dombrowski vs. Pfister, 380 US 479

(1965) ______________ 12, 13, 24, 25, 29, 30, 31

IV

TABLE OF CASES (Continued)

Page

Douglas vs. City of Jeanette, 319 US 147, 63 S. Ct.

877 87 L. Ed. 1324 ________________________ 30

Engel vs. Vitale, 370 US 421 (1962) ______________ 24

England vs. La. Board of Medical Examiners,

375 US 411 (1964) _____________________ 29, 30

Faye vs. Noia, 372 US 391 (1963) _______________ 24

Georgia vs. Rachel, 342 P. 2d 336 (1965) ______ 12, 13

Griffin vs. County School Board, 377 US 218, 12 L.

Ed. 2d 256, 84 S. Ct. 1226 __________________ 30

Hamer, et al vs. Sunflower, et al (C. A. 5)

(unreported opinion March 11th, 1966) _______ 35

Harrison vs. NAACP, 360 US 167, 79 S. Ct. 1025,

3 L. Ed. 2d 1152___________________________ 30

Hu An Kow vs. Nunan, 5 Sawy. 552, 600 Fed.

Case #6546 (1879) ___________ _____________ __ n

Kentucky vs. Powers, 201 US 1, 50 L. Ed. 633

(1906) ------------- 8, 12, 17, 18, 24, 27, 28, 29, 37

Louisiana P. & L. Co. vs. Thibodeaux, 360 US 25, 79

S. Ct. 1070, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1058 ________________ 30

McNeese vs. Board of Education, 373 US 668, 10 L.

Ed. 2d 622, 83 S. Ct. 1433 31

V

Meredith vs. Fair, 343 F. 2d 343 (1963) __________ 19

NAACP vs. Button, 371 US 415 (1963) ___________ 25

Neal vs. Delaware, 103 US 370 (1881) ___________ 28

Peacock, et al vs. City of Greenwood, 345 F. 2d 679

(C. A. 5) (1965) ______ 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 37, 38, 39

Peay vs. Cox, 190 F. 2d 123 (C. A. 5) (1951) ______... 34

People vs. Galamison, 342 F. 2d 255 (1965) ____ 37, 39

Plessey vs. Ferguson, 163 US 537, 41 L. Ed. 256,

16 S. Ct. 113 (1896) ___________________ 27, 28

Scott vs. Sanford, 19 How. 393, 60 S. Ct. 691 (1857)— 13

Slaughterhouse Cases, The, 16 Wall, 36, 21 L. Ed.

394 (1873) _______ ________________________ 27

State of South Carolina vs. Katzenbach

(unreported opinion of March 7, 1966) ____ 31, 32

Strauder vs. West Virginia, 100 US 303 (1880) — 10, 18

U. S. vs. Campbell, (N. D. Miss.)

(unreported opinion #G C 633, 1965) ------------- 36

U. S. ex rel Goldsby vs. Harpole, 236 F. 2d

71 (1959) _____________________________ 13, 22

TABLE OF CASES (Continued)

Page

VI

TABLE OF CASES (Continued)

Page

U. S. vs. Mississippi, 339 F. 2d 679 (C. A. 5)

(1964) ------------------------------------------------- 35, 38

U. S. vs. Mississippi, 380 US 128, 85 S. Ct.

088 (1965) ____________ _____ 16, 33, 34, 35, 38

U. S. vs. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (1961) _________ 13, 39

Virginia vs. Rives, 100 US 313, 25 L. Ed. 667

(1870) ____ 10, 12, 17, 18, 23, 24, 27, 28, 29, 37

Weathers, et al vs. City of Greenwood

(percuriam) ____________________ 1, 2, 7, 9, 35

Williams vs. Mississippi, 170 US 213 (1898) _______ 22

CONSTITUTIONAL AND

STATUTORY PROVISIONS

Civil Rights Act of 1870, 16 Stat. 140____________ 21

Civil Rights Act of 1871, 17 Stat. 13 _____________ 21

Civil Rights Acts of 1875, 18 Stat. 335, 18 Stat. 470 __ 21

Civil Rights Act of 1957, 42 USC Section 1971 __ 38, 43

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27 ______ 18, 21, 31

Constitution of Mississippi — Art. 3, Section

31 (1890) ________________________________ 17

VII

TABLE OF CASES (Continued)

Page

Constitution of Mississippi (1890) Art. 14

Section 243 _______________________________ 22

Constitution of Mississippi (1890) Art. 14

Section 244 ____________________________ 22, 34

Constitution of Mississippi, (1890) Art. 14,

Section 264 ___________________________ 22, 32

Constitution of the United States, Art. VI

(Supremacy Clause) ___________________ ___ 2

Constitution of the United States Amendment 1 3 ----- 21

Constitution of the United States

Amendment 1 4 ___________________ 2, 21, 28, 43

Constitution of the United States Amendment 1 5 ___ 21

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure — Rule 8(a) -------- 16

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure — Rule 7 ------------- 23

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure —

Rule 6(b) (2) ____ ________________________ 23

Laws of Mississippi 1866-67, —

pp. 232-233 __________________________ 18, 19, 41, 42

17Mississippi Code, Sections 1836-39 ------

Mississippi Code, Sections 2613 and 2639 13

VIII

Mississippi Code, Section 2296.5 ___________ 3, 10, 12

Mississippi Code, Section 9352-21, Section 9352-24 __ 6

Mississippi Code, Sections 6185-13, 2089.5 and 2291 _ 6

TABLE OF CASES (Continued)

Page

Mississippi Code, Section 1798 _______________ 33, 37

Mississippi Code, Section 1796 _______________ 33, 36

Mississippi Code, Section 1766 _______________ 22, 32

Mississippi Code, Section 1762 _______________ 22, 32

Mississippi Code, Section 4065(3) ________________ 15

Mississippi Session Laws 1865, pp. 86-93 _______ 19, 41

28 U S C Section 1443

(1964) _____ ______ 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 17,

_______________________________ 23, 37, 39, 40

28 U S C, Section 1446(a) 1964 _______________ 3, 16

42 U S C, Section 1971 _____________________ 14, 43

28 U S C, Section 2283 _________________________ 31

LEGISLATIVE MATERIALS

Congressional Globe; 1866, 39th Congress,

Pt. I, p. 474 ______________________ 41

IX

Congressional Globe; 1866, 39th Congress,

Pt. II, p. 1413_____________________________ 40

Congressional Globe; 1866, 39th Congress,

Pt. I, p. 588 _______________________________ 42

OTHER SOURCES

Aptheker; “Mississippi Reconstruction and The Negro

Leader Charles Caldwell” Science and Society,

Vol. XI No. 4 _____________________________ 19

Amsterdam; Criminal Prosecutions Affecting Federal

ly Guaranteed Rights: Federal Removal and Ha

beas Corpus Jurisdiction to Abort State Court

Trial; 113 Univ. of Penn. Law Review, 793,

(1965) ___________________________________ 40

Franklin; The Relation of the Fifth, Ninth and Four

teenth Amendments to the Third American Con

stitution -4-5 Howard Law Journal 171 (1958) — 21

Kurland, Toward a Co-operative Judicial Federalism;

The Federal Court Abstention Doctrine, 24 FRD

481 ______________________________________ 30

Preaus, Note 8, 39 Tulane Law Review (1965) ____ 29

Silver, Mississippi The Closed Society

Harcourt Brace & World (1964) _____________ 19

TABLE OF CASES (Continued)

Page

TABLE OF CASES (Continued)

Page

Stephenson, Gilbert T., Race Distinctions in American

Law (Appleton, 1910) ______________________ 20

Wharton, Vernon L., The Negro in Mississippi,

Univ. North Carolina Press

(1947) ---------------------------- 18, 19, 22, 33, 41, 42

Woodward, C. Vann, Origins of the New South, South

ern History Series, La. State University Press,

Vol. IX (1951) _____________________ 21, 22, 35

Woodward, C. Vann, Reunion and Reaction

Doubleday — Anchor Ed. (1956) ___ _____ 21, 22

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1965

No. 471

THE CITY OF GREENWOOD, MISSISSIPPI,

Petitioner

versus

WILLIE PEACOCK, ET. AL.

No. 649

WILLIE PEACOCK, ET. AL.

versus

Petitioners

THE CITY OF GREENWOOD, MISSISSIPPI

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the District Court below relative to

the Peacock portion of this consolidated case is found

at page 9 of the record. The Weathers opinion is at

page 67 of the record. These opinions are unreported.

However, the Court of Appeals opinion in Peacock by

Judge Bell, found at page 21 of the record, is reported

2

in 347 F. 2d at 679. The Weathers Appellate opinion

is per curiam and unreported. It is found at page 96

of the record.

JURISDICTION

The original judgments of the Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit were entered on June 22nd, 1965

(Peacock) and on July 20th, 1965 (Weathers). No

petition for a re-hearing was filed and applications for

writs of certiorari were made by the City of Greenwood

on August 19, 1965, and by Peacock, et. ah, on October

5, 1965. Certiorari was granted January 17, 1966. This

Court has jurisdiction of this matter under title 28 USC

§1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND

STATUTES INVOLVED HEREIN

1. The supremacy clause of the Constitution of the

United States (Article VI) and the Fourteenth Amend

ment to that Constitution are both involved herein.

2. The following statutes are also involved:

28 U.S.C. §1443(1964):

§1443. Civil rights cases.

Any of the following civil actions or criminal

prosecutions commenced in a State court may be

removed by the defendant to the district court

of the United States for the district and division

embracing the place wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied, or can

not enforce in the courts of such State, a right

3

under any law providing for the equal civil rights

of citizens of the United States, or of all persons

within the jurisdiction thereof;

(2) For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights, or for

refusing to do any act on the ground that it

would be inconsistent with such law.

28 U.S.C. 11446(a) (1964):

§1446. Procedure for removal.

(a) A defendant or defendants desiring to re

move any civil action or criminal prosecution

from a State Court shall file in the district court

of the United States for the district and division

within which such action is pending a verified

petition containing a short and plain statement

of the facts which entitle him or them to re

moval together with a copy of all process, plead

ings and orders served upon him or them in

such action.

Mississippi Code §2296.5

“It shall be unlawful for any person or persons

to wilfully obstruct the free convenient and nor

mal use of any public sidewalk, street, highway,

alley, road, or other passageway by impeding,

hindering, stifling, retarding or restraining traf

fic or passage thereon, and any person or per

sons violating the provisions of this act shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor.”

4

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I A) Whether a removal petition which alleges a

racially-motivated arrest, charge and prosecution of civil

rights workers peacefully engaged in a campaign to

register Negro voters, which arrest is alleged to be de

signed to harass and intimidate such workers, states a

case for removal under title 28USC§1443 (1964). (cov

ered in part IA) of the argument)

I B) Whether as a matter of pleading a removal peti

tion that alleges a racially-motivated arrest, charge and

prosecution, designed to suppress Negro voter registra

tion activity, sufficiently describes a denial of an equal

civil right and/or an inability to enforce in the courts

of the state a right under a law providing for equal

civil rights so as to set forth a case for removal, (cov

ered in Part IB) of the Argument)

II A) Whether a removal petition which alleges that

Negroes are administratively excluded from juries which

will try such state-charged petitioners, arrested while

assisting Negoes to register to vote, describes an inability

to enforce in the courts of that state a right under a law

providing for the equal civil rights of citizens, thereby

stating a case for removal under Title 28USC§1443 (1).

(covered in part IIA) of the Argument)

II B) Whether a petition which alleges that state jury

selection laws as written are unconstitutional and ex

clude females and Negroes from service on juries that

will try state-charged petitioners describes an inability

to enforce in the courts of that state a right under a

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens, there

by stating a case for removal under Title 28 USC§1443-

(1)- (covered in Part IIB) of the Argument)

5

III Whether a petition that alleges civil rights workers

were arrested and charged by the state for assisting

Negroes to register to vote in Mississippi are thereby

prosecuted for an act performed under color of authority

derived from the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil

Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, and additionally for re

fusing to do an act, i.e., for desisting, on the ground that

it would be inconsistant with such equal federal laws, all

within the meaning of Section 1443(2), sets forth a case

for removal, (covered in part III of the Argument)

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The fourteen petitioners in the Peacock case were all

arrested on March 31, 1964, by city officials in the City

of Greenwood, Mississippi, and charged with violating

Section 2296.5 of the Mississippi Code Annotated of

1942. Petitioners, who were all members of the Student

Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, were arrested while

picketing the LeFlore County Court House, and were

charged with obstructing public streets. On April 3,

1964, before trial in the Police Court of the City of

Greenwood, Mississippi, petitioners filed removal peti

tions in the United States District Court for the North

ern District of Mississippi (Greenville Division), alleg

ing jurisdiction under both sub-sections of 28 U.S.C. 1443.

Petitioners alleged that they were members of the Stu

dent Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, affilated with

the Council of Federated Organizations, both civil rights

groups. Petitioners further alleged that at the time of

their arrest they were engaged in a voter registration

drive in LeFlore County, Mississippi, assisting Negroes

to register so as to enable them to vote. They further al

leged that they could not enforce their rights under the

First and Fourteenth Amendments of the Federal Consti

6

tution to be free in speech to petition and to assemble, that

they were denied the equal protection of the laws, the

privileges and immunities of the laws and the due pro

cess of law, inasmuch as, among other things, they were

arrested, charged and were to be tried under a state

statute which was vague, indefinite and unconstitutional

on its face, and was unconstitutionally and arbitrarily

applied and used, and was enforced in the instance of

their arrest as “a part and parcel of the unconstitutional

and strict policy of racial segregation of the State of

Mississippi and the City of Greenwood.” Because of the

aforementioned, petitioners finally alleged, they were

denied and/or could not enforce in the courts of the

State of Mississippi the rights they possess providing for

equal protection and equal rights. Petitioners invoked

the application of both sub-sections of 28 USC. Section

1443.

The Weathers case also involved criminal cases re

moved from the Police Court of the City of Greenwood,

Mississippi, under authority of 28 U.S.C. 1443, subsec

tions 1 and 2. In that case there are fifteen applicant-

petitioners who were arrested at various times during

the month of July, 1964, and charged with the following

offenses: parading without a permit in violation of an

ordinance of the City of Greenwood, Mississippi, enacted

June 21, 1963, and recorded in Minute Book 55 at page

67 of the Records of Ordinances of the City of Green

wood, Mississippi; contributing to the delinquency of a

minor in violation of Section 6185-13 of Mississippi Code

Annotated of 1942; the use of profane and vulgar lang

uage in violation of Sections 2089.5 and 2291 of the

Mississippi Code Annotated of 1942; disturbance in a pub

lic place; disturbing the peace in violation of Section

7

2089.5 of the Mississippi Code Annotated of 1942; as

sault; assault and battery; inciting to riot; operating a

motor vehicle with improper license tags in violation of

Sections 9352-21 and 9352-24 of the Mississippi Code An

notated of 1942; interfering with a police officer in the

performance of his duty; and reckless driving.

Some of the petitioners in the Weathers case are

charged with more than one of the offenses listed above,

and some of them jointly filed one petition for removal.

Petitioners’ petitions for removal in the Weathers case

allege different facts, but with respect to 28 U.S.C. Sec

tion 1443(1) they allege that petitioners cannot enforce

their equal civil rights under the Fourteenth Amendment

in the courts of the state for the folio-wing reasons, to

wit: Mississippi courts and law enforcement officers are

committed to a policy of racial segregation and are pre

judiced against petitioners; under Mississippi law, cus

tom and practice racially segregated court rooms are

maintained; in Mississippi court rooms Negro witnesses

and attorneys are addressed by their first names; local

counsel are unavailable to petitioners and Mississippi

courts are closed to out-of-state attorneys; Mississippi

judicial officials are elected by elections in which Negroes

have been denied the right to vote; and Negroes are

systematically excluded from jury service. The peti

tioners also alleged that they were entitled to remove

their cases to federal court under the authority of 28

U.S.C. Section 1443(2).

In both the Peacock and Weathers cases, the City of

Greenwood filed motions to remand, which were sustained

by the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Mississippi (Greenville Division) on the

grounds that the said petitions did not state a removable

8

case under either subsection of 28 U.S.C. Section 1443.

The District Court refused to order an evidentiary hear

ing on the allegations of the petitions.

The petitioners in both cases appealed to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which

court, after issuing a stay order in the Peacock case

(decided before the 1964 Civil Rights Act permitted an

appeal of a remand order) entered judgment in Pea

cock on June 22, 1965. The Court of Appeals in

the Peacock case affirmed the District Court’s hold

ing regarding Section 1443(2) but reversed its holding

under Section 1443(1) and therefore remanded that case

to the District Court for a hearing on the truth of the

allegations in the petitions for removal. The Court of

Appeals refused to consider petitioners’ allegation that

the Statute under which they were charged was vague

and indefinite because the District Court did not reach

the question, but held that the unconstitutional applica

tion by State Officials of a State Criminal Statute valid

on its face in such a manner as to violate a person’s

rights under the equal protection clause of the Federal

Constitution is sufficient to entitle such person to re

move his case to Federal Court. The Court interpreted

certain Supreme Court decisions ending with Kentucky

v. Powers, 1906, 201 U.S. 1, 50 L. Ed. 633, holding that,

in order to establish removal jurisdiction, the denial of

equal rights through the systematic exclusion of Negroes

from Grand and Petit juries must result from State

legislative or constitutional provisions. Interpreting 28

U.S.C. 1443 Subsection (2), the court held that this sec

tion is limited to Federal officers and those assisting

them or otherwise acting in an official or quasi-official

capacity and held that this Section does not authorize re

9

moval by any person who is prosecuted for an act com

mitted while exercising an equal civil right under the

Constitution or laws of the United States.

On July 20, 1965, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit sustained the petitioners’ motion for a summary

reversal in the Weathers case, holding that the issues in

that case were identical with and therefore controlled

by the Court’s opinion in the Peacock case.

In remanding the cases to the District Court for fur

ther hearings, the Court of Appeals decided a Federal

question, namely, the scope of removal jurisdiction under

28 U.S.C. Section 1443.

Following these decisions of the Court of Appeals in

Peacock and Weathers, the City of Greenwood applied

for a writ of certiorari on August 19, 1965. The appel

lants below filed a cross-petition for certiorari on October

5, 1965, and this Court granted certiorari on January

17, 1966.

ARGUMENT

I

A RACIALLY - MOTIVATED ARREST AND

CHARGE, DESIGNED TO USE STATE LAW TO

HARASS AND INTIMIDATE CIVIL RIGHTS WORK

ERS WHO ARE ASSISTING NEGROES IN REGIST

ERING TO VOTE, PRESENTS A CASE FOR RE

MOVAL UNDER 28 U.S.C. SECTION 1443(1).

A. In this case the “law providing for the equal civil

rights of citizens . . .” is the Fourteenth Amendment.

In the decision below, Judge Bell makes three points in

regard to this part of the argument. First, he simply

states that this is the law involved:

10

“It is settled that the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment constitutes a ‘Law

providing for the equal civil rights of citizens

of the United States’ within the meaning of Sec

tion 1443(1).”

Secondly, he held that while the due process clause is

not such a law providing for equal civil rights, where

the claimed denial of an equal civil right is based on

race, such a claim meets the test of the removal statute:

“The removal statute contemplates those cases

that go beyond a mere claim of due process vio

lation; they must focus on racial discrimination

in the context of denial of equal protection of the

laws.”

Thirdly, and most importantly, the court below held

that mere allegation of an unconstitutional application

of state laws so as to deny equal protection because of

race is sufficient to meet the whole test of removal:

“Appellants allege that Mississippi Code Section

2296.5 is being applied against them for pur

poses of harassment, intimidation and as an

impediment to their work in the voter registra

tion drive, thereby depriving them of equal pro

tection of the Laws. We simply hold that these

allegations entitle appellants to remove their

cases to the federal court.”

Of great significance is the fact that the opinion be

low distinguishes this pre-trial, administrative type of

denial from the narrow interpretation given Section 1443

by the Rives and Powers doctrine1 and restricts those

1 Virginia vs. R ives, (1870) 100 U.Si. 313, 25 L. Ed. 667; K en tu cky vs.

Powers (1906) 201 U.S. 1, 26 S. Ct. 387, 50 L, Ed. 633, and Strauder vs.

W est V irg in ia et. al. U.S, 303 (1880).

11

eases to their bare facts. This holding is elaborated upon

in point IIA) which follows.

In essence it should be said that these holdings above

set forth recognize the realities of Negro life in Missis

sippi in 1964-65 and even now. Judges, and especially

Federal judges, are not “. . . forbidden to know as judges

what [they] see as men.” Hu An Kow vs. Nunan, 5

Sawy. 552, 560, Fed. Cas. #6546 (1879).

In effect, what Judge Bell was saying was that when

a minor state statute is used as a concealed segregation

law, the courts will deny the states that use of that

law. The federal courts have repeatedly stated that they

will strike down, even by the extraordinary writs, sophis

ticated as well as simple-minded schemes of racial segre

gation.2 The State of Mississippi piously complains and

in all innocence states that it fails to see a possible con

nection between obstruction of the public streets and

being unable to enforce an equal civil right in the State

courts.3 The most recent decisions of this court have

swiftly punctured such bland smugness. In Brown vs.

Louisiana, (No. 41, October Term, 1965, opinion rendered

February 23, 1966), Mr. Justice Fortas does not hesitate

to see as a judge what we all know as men, when he

says:

“We need not be beguiled by the ritual of the

request for a copy of ‘The Story Of The Negro.’

We need not assume that petitioner Brown and

his friends were in search of a book for night

reading. We instead rest upon the manifest

2B ush vs. Orleans P arish School Board, 364 TJ.S. 500, 81 S, Ct. 260, 5 L.

Ed. 2d 245 (194 F . Supp. 182).

3See pages 3 and 4 of City of Greenwood’s b rie f below in the C ourt of

Appeals.

12

fact that they intended to and did stage a peace

ful and orderly protest demonstration . .

The entire appellate history of this removal statute

until Rachel4 found the courts blind to the real meanings

of southern rural Negro life and responsive only to be

guiling notes of the southern redeemers preaching a new

application of an old formalism. This formalism, re

flected by the Gertge5 decision, was founded by Rives

and Powers and those cases that followed Neal vs. Dela

ware 103 U.S. 370. This court has consistently looked

through many such versions of legal obscurantism and

empty formalism to reach the truth. Dombrowski vs.

Pfister 380 U.S. 479 (1965), Cox vs. Louisiana, 379 U.S.

536 (1965). It should be so in this case.

Opposition to the southern Negro freedom movement

consistently indulges in the rigid legal formalism re

quired to conceal the true intent of crypto-segregationist

statutes such as Section 2296.5 of the Mississippi Code.

From the over-frequent use of such banal enactments

one would almost be persuaded that the reason Missis

sippi law enforcement officials are unable to solve the

frequent racial homicides in their state is that Mississippi

is simply overrun with Negroes wantonly picketing court

houses or unlawfully using profanity.6

The real truth, however, is not so lightly stated. The

Mississippi statutes used or rather misused here are part

and parcel of a rebellious and arrogant defiance of fed

erally-created, and protected, rights by the State of Mis

4Georgia vs. R achel et. al. 342 F . 2nd 336 (1965).

5Clarksdale vs. Gertge, 237 F . Supp. 213 (1964).

S it is estim ated th a t nearly 3000 civil r ig h ts m isdem eanor cases still

pend in M ississippi S ta te and F edera l courts, a ll left over from the

F reedom Sum m er of 1964 and before.

13

sissippi. The power structure of that state is doing to

day what it did one hundred years ago; that is, to erect

simple-minded and, when necessary, ingenious ramparts

to hold off Federal protection for the Negro.

Although the Mississippi Legislature may have diffi

culty in legalizing state-taxed whiskey,7 it is not so naive

as to legislate Negroes out of the jury system in exact

terms or to specify that only civil rights workers can be

arrested for obstructing the city streets. On the other

hand, no person should be expected to believe that Negroes

serve freely on Mississippi juries,8 or that civil rights

workers are not harassed.9

The current formalism of the Southern legal position

on civil rights is no more valid than the earlier disreput

able formalism of the Dred Scott case.10 It is this nacent,

empty, legal formalism that the Court below struck at

when it authorized this removal. That part of the

opinion should be affirmed.

B. THE PLEADING IS SUFFICIENT.

The pleading herein complained of by the City of

Greenwood was found to be sufficient by the Court of

Appeals:

“Under the Precedent of Rachel and the au

thorities therein cited having to do with notice

type pleading, we hold that the removal petitions

are adequate at this stage of the proceeding . . .u

7See § 2639, M ississippi code tax in g alcoholic sp irits , th e possession of

w hich is m ade illegal by M ississippi Code § 2613.

8U.S. ex re l Goldshy vs. H arpole, 236 F. 2d 71 (1959).

QU.S. vs. Wood, 295 F . 2d 772 (1961); D om'browski vs. P fister , 227 F

Supp. 56 (1964) (D issen t) , 380 TT.S. 479 (1965).

lOScott vs. Sandford, 19 How. 393 60 S. Ct. 691 (1857).

U Opinion below, 347 F. 2d 679 a t 682.

14

The petitions clearly allege the expressly unconstitu

tional character of the statutes sought to be employed

by the State,12 as well as the unconstitutional applica

tion of those laws.13 Admittedly, the language of the

Peacock petition is more general than Weathers but its

allegations leave no doubt that at least the petitioners

claimed harassment as a Section 1443 (1) ground, and

the voting provisions of the 1960 Civil Rights Act (42

U.S.C. 1971) as authority for a Section 1443(2) re

moval.

The Peacock petition allegations that bring into focus

1443(1) are as follows:

“II. Petitioner is a member of the Student Non-

Violent Coordinating Committee affiliated with

the Conference [Council] of Federated Organ

izations, both Civil Rights Groups and was at

the time of the arrest engaged in a voter reg

istration drive in Leflore County, Mississippi,

assisting Negroes to register so as to enable them

to vote as protected under the Federal Consti-

ttuion and the Civil Rights Act of 1960, being

42 USCA 1971 et. seq.

III. Petitioner as a citizen of the United States

cannot enforce his rights under the first and

14th amendments of the Federal Constitution to

be free in speech, to petition and to assemble;

is denied the equal protection of the Laws, the

privileges and immunities of the Laws and due

process of Laws, inasmuch as among other

things was arrested, charged and is to be tried

under a state statute that is vague, indefinite

and unconstitutional on its face; is unconstitu

tionally and arbitrarily applied and used, and

12R. 4 for Peacock, R. 42, W eathers.

13R. 4 for Peacock, R. 38-42, W eathers.

15

is enforced in this instance as a part and parcel

of the unconstitutional and strict policy of racial

segregation of the State of Mississippi and the

City of Greenwood.”

The main Weathers allegations covering subsection (1)

are:

“C-l. The arrests and prosecutions of Petition

ers have been and are being carried on with the

sole purpose and effect of harassing Petition

ers and of punishing them for and deterring

them from the exercise of their constitutionally

protected right to protest the conditions of ra

cial discrimination and segregation which exist

in all public aspects of life in Mississippi and

which the State of Mississippi now maintains

and seek to enforce by statute, ordinance, reg

ulations, custom, usage and practice.

C-2. Among recent legislative enactments evi

dencing Mississippi’s policy to enforce racial

discrimination and segregation and to suppress

all protest against such discrimination and seg

regation are Mississippi Code, Section 4065(3),

which purports to prohibit the executive offi

cers of the State from obeying the desegrega

tion decisions of the United States Supreme

Court, and the several statutes enacted by the

1964 session of the Mississippi legislature which

purport to prohibit picketing of public build

ings, congregating and refusing to disperse;

printing or circulating material which interferes

with the operation of a business establishment;

printing or circulating material which advocates

social equality; the disturbing of the peace of

others; giving false statements of complaints to

Federal officials; obstructing public streets; en

couraging others to remain on private premises

of another when forbidden to do so; and statutes

16

which purport to authorize officials to restrain

the movements of groups and individuals and to

impose curfews; authorize an increase in the

strength of the State Highway Patrol from 274

to 475 men and give the Governor power to dis

patch the Highway Patrol into areas on his own

initiative; authorize an increase of the maxi

mum penalty for violating a city ordinance

from 30 to 90 days imprisonment and a fine of

$300; and authorize communities to pool their

police forces and equipment.14

Additionally, the Weathers petitions refer specifically

to jury discrimination,15 State policy of racial segrega

tion,16 unfair trial,17 and lack of counsel,18 all arguable

grounds for removal under Section 1443(1).

The removal statues (28 U.S.C. Section 1446(a) (1964))

require the petition to contain “a short and plain state

ment of the facts which entitle [the petitioner] . . . to

removal.” Since 1948 this rule has brought removal

practice into line with the notice pleading theories of

Rule 8(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.19

Whether one uses the “short and plain statement” of

the Peacock petition or the more detailed allegations of

the Weathers petitions, the pleading requirements of Fed

eral law relative to removal are met in these cases.

II

A. A REMOVAL PETITION WHICH ALLEGES

UNCONSTITUTIONAL APPLICATION OF STATE

14In th is regard see the l is t of s ta te voter re g is tra tio n im pedim ents se t

fo r th by Mr. Ju s tice B lack in h is opinion in U.S. vs. M ississippi, 380

tX.Si. 128, 85 S. Ct. 808 (1965) a t 810.

15R. 41 (C-3-f).

16R. 38 (0-2).

17R. 39-40 (C-3-a).

18R. 40-41 (0-3-8).

19(See page 117, footnote 17, R achel b rief in th is C ourt).

17

LAWS, INCLUDING JURY SELECTION STATUTES,

SO AS TO EXCLUDE NEGROES FROM JURY SERV

ICE, SETS FORTH A CASE FOR REMOVAL UNDER

SECTION 1443(1), TITLE 28 U.S.C.

The issue posed by this headnote is that of the legal

and historical validity of the doctrines of Virginia vs.

Rives, (100 U.S. 313 (1880) and Kentucky vs. Powers,

201 U.S. 1 (1906). These cases can be said to severely

limit federal removal by holding that the denial of equal

protection must appear from explicit state statute or

constitutional enactment. Had it not been for these de

cisions, modern federal practice would have brushed

aside such arguments and promptly examined the facts

of jury service by Negroes in the jurisdictions concerned.

However, because of these cases, we must pause to con

sider whether or not a petition that alleges the Negro20

person or civil rights worker accused by the state can

not enforce in the state courts an equal civil right when

Negroes are excluded from the jury by corruption and

maladministration, states a case for removal.

This question cannot be considered in, a vacuum. While

obviously there is no evidence on this point in the record

since no hearing was permitted below, the basis for the

allegation should be examined. This requires a histori

cal treatment; not only of what Mississippi society has

done to the institution of the jury trial, but what it

has done to the Negro. Such facts as this treatment

may disclose are not evidence, however. They are

drawn from sources that include the federal courts as

well as historians, and may tell us how and why the

historically incorrect doctrines of Rives and Powers are

20R. 3 9 , 40. Also by th e M issississippi C onstitu tion A rt. 3 § 31, & Miss.

Code §§ 1836-39, p e titioners a re en titled to a tr ia l by ju ry .

18

inconsistent with the experiences of life and legally

wrong.

In any consideration of what the Thirty-Ninth Con

gress had in mind when it passed the third section of

the Civil Rights act of 1886, the state of the nation,

and of the South of that time, in particular, is im

portant. This subject is considered in the following

part.

One final comment by way of introduction is in order.

It should be noted that Part B of this second part of the

Argument is an alternative attack upon the Mississippi

jury system as unconstitutional on its face. A reading

of the state statutes will show that Mississippi may not

have been as ingenious or competent as some other states

in devising a jury selection system that appears racially

non-discriminatory, but this should not detract from the

fact that the Mississippi laws here considered allow a

full-fledged and complete theoretical attack on the Rives

and Powers doctrine.

1) Historically, Mississippi, like West Viriginia in the

Strauder case,21 attempted to rebuild the old society of

privilege with new forms. Early in the 1865-67 redemp

tion of that state, Negroes were by explicit statute ex

cluded from jury service.22 After Strauder and with

communication between Northern Republicans and South

ern redeemers restored by the Hayes-Tilden arrangement

(and spelled out in detail by Rives and Powers), that

state understood the ground rules. Henceforth, while on

the one hand excluding Negroes from the political and

judicial life of the State,23 it presented on the other hand

21Strauder vs. W est V irginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880).

22Laws of M ississippi, 1866-67, pp. 232-233.

23W harton, The Negro in M ississippi, (U n iversity of N orth C arolina

P ress 1947), C hapter XIV.

19

a fraudulent legal image of strict racial indifference to

the nation.24

Actually, the ability of the free Mississippi Negro to

enforce in his State courts such elemental rights of citi

zenship as legal personality and the competency to give

evidence, was specifically denied in law as early as 1865.25

The abandonment that year by the Federal Occupying

forces of the Freedmens Bureau courts throughout the

state26 was an ominous sign of the larger abandonment

of the Negro that occurred in 1877, following the elec

tion of Hayes.

The very first attempt by Mississippi to legislate Freed

mens rights resulted in the Black Codes of 1865, which

in effect re-enacted the slave codes with modifications.27

These codes prohibited Negroes from holding rural land,

and in effect conscripted the Negro into a race of in

dentured servants. The first post-war Provisional Mis

sissippi Legislature even attempted by resolution to nul

lify emanicipation and to restore slavery. This proposal

received substantial minority support.28

Though the Black Codes were repealed in 1867, the

Legislature specifically provided that Negroes could not

serve on grand and petit juries.29 This rule was over

24This im age has its m odern m akers. P rofessor S ilver w rites:

“The contention of th e B oard of T rustees and of U n iversity offi

cials, accepted as fac t by Judge Mize . . th a t th e U niversity is

no t a rac ia lly segregated in s ti tu tio n ’ and th a t ‘the s ta te has no

policy of seg regation’, . . . defies h is to ry and comm on know ledge.”

Silver, M ississippi: The Closed Society (H arco u rt Brace & W orld,

1964), page 114, M eridith vs. F air, 343 F2d 343 (1963).

25W harton, op cit., pages 76, 77, 134 and 135.

26General O rders #13 , V icksburg, October 21, 1865, quoted in W harton,

op. cit.

27Mississippi Session Law s 1865, parag raphs 86-93.

28C onstitutional Convention Jo u rn a l 1865, parag raphs 68-70; see also in

th is regard , A p theker; “M ississip in R econstruction and the Negro

Leader Charles Caldwell,” Science and Society, Vol. X I, No. 4, p, 340,

a t p. 343.

29Laws of M ississippi 1866-67, p a rag rap h s 232-233.

20

turned only by the order of the Federal Occupational

Commander two years later.30

Professor Wharton, in his work, The Negro in Missis-

sippi (University of North Carolina Press, 1947) at page

137 succinctly describes the plight and history of Negro

jurymen in that state:

“After 1875, the Negroes appeared in smaller

and smaller numbers on the jury panels, but

their complete elimination did not occur until

after 1890. In the constitution of that year it

was provided that all persons serving on grand

or petit juries must be qualified electors and

must also be able to read and write. Thus the

elimination of the Negro as a voter served also

to remove him from the jury bench, and in a

land of white officers, white judges, white law

yers and white juries, the term daw,’ in the

Negroes’̂ mind, came more and more to mean

only a big white man with a badge.”

In his book, Race Distinctions in American Laiv (Ap-

pelton, 1910) Gilbert T. Stephenson, at page 259, graphi

cally illustrates the extent to which by 1910, Negroes

were excluded from jury service. He quotes from letters

solicited from Clerks of Court in Mississippi covering

nine counties. The adminstrative method of exclusion

set forth is appallingly efficient.31

30General O rders No. 32 A ppletons Cyclopedia 1864, p a ras 455-456

V icksburg D aily Tim es, A pril 30, 1869.

31A sam ple from county # 6 :

“ . . . In m y County we had no Negroes on th e ju ry fo r the past

15 years o r more. We have som e 30,000 colored population in th is

county, . . . and we have only about 175 reg iste red in the county

The board of supervisors, a s a ru le, does no t place th e ir nam es

in th e box. . . . ”

Sam ple from County # 7 :

“1000 w hite people, 4000 N egroes: . . . we have no N egro ju ro rs

in th is county a t a ll.”

21

The federal response to such actions of the provisional

government was reasonably swift and direct. If the

southern legislatures, including Mississippi, were to re

impose slavery in another form, then the base of the

electorate had to be radically altered. After the Civil

Rights Act of 186632 had been followed by the Thirteenth

Amendment, the foundation had been laid for the balance

of the “Third American Constitution,”33 the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments, and the Civil Rights Acts

of 1870, 1871 and 1875.34 As a result of these enactments

the formal legislative response to the war was largely

complete.

Two essential points were made by this codification.

First, that while the war had been fought in the name

of the Union, the legal expression of victory was, not

unexpectedly, couched in terms of equal humans rights,

and — secondly — those rights received extensive and

serious federal protection. The withdrawal of that pro

tection as a matter of political expediency at the time

of the Hayes-Tilden arrangement of 187735 cannot detract

from the validity of its original content, or the effective

ness and necessity of its current meaning.

While the federal government turned away after 1890

from an interest in Negro rights, and was engaged in

Asian wars, and the struggle in Cuba,36 the state of Mis-

32Act of A pril 9, 1866, chs. 31, 14, s ta tu te 27.

33See F ran k lin , The R ela tion of th e F ifth , N in th and F ourteen th A m end

m en ts to the 3rd C onstitution, 4-5, H oward Law Journal, 171 (1958)

341870; ch. 114; 16 S tat. 140: 1871; ch. 22, 17 S tat. 13: 1875; A ct of M arch

1, 1875, Ch. 114, 18 S tat. 335, and Act of M arch 3, 1875, Ch. 137, 18 S tat.

470.

35.Siee W oodward, R eun ion and R eaction Doubleday-Anchor Ed. (1956).

360n th is po in t see the effect of Im peria lism in A sia described by P ro

fesso r W oodward. “W ith the sections (N orth and South) in rapport, the

w ork of w ritin g th e w hite m an’s law for A sia and Afro-Am erica w ent

fo rw ard sim ultaneously .” Origins of the N ew South , S outhern H isto ry

Series, La. S ta te Univ. P ress, 1951, page 326.

22

sissippi, as ruled by the redeemers, was “responsible” to

its sources of power. In the Constitution of 1890, Ne

groes were finally and effectively denied the franchise

and thereby excluded from jury service. It is not coin

cidental that this document, containing a “grandfather”

clause and “comprehension” requirements, similar to pre

sent franchise enactments,37 followed Rives and preceeded

Williams vs. Mississippi.38 By this time Negro registra

tion was down in that state from a high in 1867 of 60,167

(46,636 for whites) to 8,615 (68,127 whites in 1892.39

The constitutional connection between the franchise and

jury service has continued to this day40 and serves as a

vital link in the Mississippi plan of racial segregation.41

2) Mississippi was not so different from the other

states of the old Confederacy that its experiences and

response were unique. Certainly, these matters were in

the mind of Congress when in 1866 it clearly stated that

criminal prosecutions commenced in a state court may be

removed to a federal forum when they were brought

against:

“Any person who is denied . . . a right under any

37Mississippi C onstitu tion , Sections 243-244.

38170 U.S. 213 (1898).

39W harton op. cit., pp. 146 and 215.

40Mississippi C onstitu tion A rt. 14, Section 264; M ississippi code, Sections

1762 and 1766. See also GoldsVy vs. H arpole, op. cit.

41For a good descrip tion of th e M ississippi P lan see W oodward. Origins of

the N ew South , S ou thern H isto ry Steries. La. S tate Univ. P ress, p. 321

(1951). T his p lan w as w idely copied by the o ther Southern S tates.

(W oodw ard; R eun ion and R eaction, op. cit. a t p. 45). A nother v ita l link

w as the “A tlan ta Ctompromise” announced in 1895 by B ooker T. W ash

ing ton w hich confirm ed th e Negro abandonm ent of the P opulists (who

had ea rlie r em barked upon th e policy of u n itin g w hites so as to allow

them to d iv ide). T h is policy no t only recognized th a t 20 years of te r ro r

and opression had taken its toll, bu t p rac tica lly inv ited th e fina l d is

franch isem en t of The Negro by assign ing him a servile and hum ble

ro le in the New South.

23

law providing for the equal rights of citizens of

the United States. . .

or against:

“Any person who . . . cannot enforce in the

courts of such state, a right under any law pro

viding for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States.”

The above language does not appear in the statute in

that exact form, but under the construction given Section

1443(1) by Judge Soboloff of the Fourth Circuit in his

dissent from that Court’s opinion in Baines vs. Danville

(opinion, unreported, January 21st, 1966), the rendition

is justified.

Petitioners have obviously alleged they cannot enforce

the right to a trial jury impartially selected in the

courts of Mississippi. While in the day of the Rives

case federal and/or state procedure may have been in

adequate to show jury selection discrimination in advance

of trial, such is not true today. Adequate remedies exist

in Federal courts under the rules of both civil and crimi

nal procedure42 to test the jury selection process. The

argument that such a showing must not be “first made

manifest at the trial of the case”43 has no real meaning

in modern times, since matters of jury composition are

routinely taken up and made manifest well in advance

of trial.

The statute as it stands today must allow removal when,

in the light of experience in life and judicial history, the

42Civil R ules R ule 7; C rim inal R ules Rule 6 ( b ) ( 2 ) .

43R ives a t p. 319.

24

allegations, if proven, would show the denial of a federal

ly-protected equal right, or the inability to enforce such

right at time of trial. In reality, there is no logical

justification for the court below to say that these peti

tioners can remove because a statute, unconstitutionally

enforced, denied them their equal civil rights by unfair

arrest, and to say as well that they cannot remove when

administrative exclusion of their race from the jury pre

vents them from being able to enforce in the state courts

the “equal civil right” of “equal protection of the laws.”

It is indeed difficult for a person to conceive of such a

difference or to avoid the conclusion that if Peacock is

the law, then Rives and Powers should be overruled.

3) While it might be said that the Rives-Powers rul

ing avoids unnecessary federal-state conflicts and restricts

the removal statute to prosecutions by states so naive as

to explicitly — by statute — discriminate against Negroes

in this day and age, this is to ignore not only life, but

the requirements of federal law. In recent years Federal

courts have largely abandoned state court review as the

only method of exerting federal sovereignty. Sensing a

growing indifference on the part of state governments

to federal rights, and recognizing the primacy of the

supremacy clause, the federal courts have not hesitated to

step in on selected occasions to exert the power of the

United States in defense of its citizens. This has occurred

in matters of: reapportionment, (Baker vs. Carr, 369

U.S. 186 (1961) ; school prayer, (Engel vs. Vitale,

370 U.S. 421 (1962) ); school desegregation, (Brown vs.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ); civil liber

ties, (Donnbrowski vs. Pfister 380 U.S. 479 (1965) ); and

fair trial, {Faye vs. Noia 372 U.S. 391 (1963) ). All

of these cases have used extraordinary remedies (of in

25

junction or habeas corpus) to supplement the traditional

method of state-federal review. The court recognized in

these instances the urgency and importance of immediate

federal intervention to protect federal rights. That find

ing is equally justified in the removal cases here pre

sented.

In this regard Dombroivski vs. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479

(1965) clearly held that where federal rights are in

danger from state action the proper function of the fed

eral courts is to interpose federal power between the

individual citizen of the United States and the State:

“When the statutes also have an over-broad

sweep, as is here alleged, the hazard of loss or

substantial impairment of those precious rights

may be critical. For in such cases, the statutes

lend themselves too readily to denial of those

rights. The assumption that defense of a crimi

nal prosecution will generally assure ample ven-

dication of constitutional rights is unfounded in

such cases. See Baggett vs. Bullitt, supra, at

379. For “the threat of sanctions may deter

. . . almost as potently as the actual application

of santions . . .” NAACP vs. Button, 371 U.S.

415, 433.44

The free speech First Amendment rights referred to

in the Dombrowski opinion quoted above are no more

44380 U.S. 479 a t 486. See also d issen ting opinion of Judge W isdom

in an ea rlie r rep o rt in th is case found a t 227 F. Supp. 556 (1964)

w herein he w ro te: “Once m ore I em phasize th a t th e basic e rro r in the

co u rt’s decision is its fa ilu re to d is tin g u ish betw een th e type case now

before i t and the ru n of the m ine su it by a c rim ina l offender ask ing for

re lie f ag a in s t un law fu l S tate action. In the Civil R igh ts Act Congress

estab lished a d is tin c t federal cause of action in favor of those whose

constitu tional r ig h ts have been invaded. 42 U.SIC.A. Sections 1981,

1983, 1985. As a m a tte r of law, since such cases involve a federa l ques

tion , the r ig h t existed anyw ay. The fact th a t such cases involve a dis

pu te over federally protected freedom s m ake th e federal co u rt th e

app rop ria te forum for se ttlem en t of the d ispute.”

26

precious and are no more federal in character than the

Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment rights

made available for special protection by the civil rights

removal statute. Title 28, Section 1443, does not allow

the removal of all or even most criminal cases, and the

jury selection interpretation sought here does not en

compass procedural evils in jury selection which do not

touch on the equal protection guarantees of the wartime

amendments. This is not argued here. However, what

is said now is that these amendments had one great aim

-—- to bring the Negro up to the level of the white man

and to use federal power to see that this was accomp

lished. This was why federal removal was vital to the

true implementation of these amendments.

Here the petitioners seek, as did the Freedmens Bureau

one hundred years ago, to raise the Negro up, to give

him the vote and the education to use it. For this they

were exposed to the wrath of the white Mississippi com

munity which promptly set into motion the machinery

of the state to suppress them. The facts of Dombroivski

show the same sequence of events in Louisiana. As stated

by Judge Wisdom in his District Court dissenting opinion

in that case:

“Chairman Pfister is quoted as saying that the

plaintiffs were racial agitators. If that is true,

and if the plaintiff’s modest agitation by mail

was motivated only by the plaintiff’s interest in

civil rights for Negroes- then once again, as in

Bush vs. Orleans Parish School Board, the State

has marshalled the full force of its criminal law

to enforce its social philosophy through the po

liceman’s club.’ Under any rational concept of

federalism the federal district court has the pri

mary responsibility and the duty to determine

27

whether a state court proceeding is or is not a

disguised effort to maintain the State’s unyield

ing policy of segregation at the expense of the in

dividual citizen’s federally guaranteed rights and

freedoms.45

Rives and Powers reflect no more than the removal

counterpart of Plessy vs. Ferguson,46 These ancient re

moval cases are judicial reflections of the Hayes-Tilden

compromise withdrawing the previously given federal sup

port of the Negro. This withdrawal was first signalled

in the Slaughterhouse cases,47 and consistently followed

for seventy-five years. It was finally given its death

blow in Brown vs. Board of Education.48 Rives and Pow

ers deserve the same fate.

4) Not only were these two removal cases historically

wrong to begin with and now hopelessly out of date, but

their reasoning is completely deficient as clearly set forth

by the city itself in its application to this court where on

page 16 it says:

“Furthermore, City submits that there is no

more reason for Congress to have believed that

one would be denied his equal civil rights in the

courts of the state because state officials alleged

ly arrested and charged him in violation of the

equal protection clause than if state officials dis

criminated against him in violation of the equal

protection clause in the selection of the grand

and/or petit jurors.”

Applicants would turn this argument on its head and

say that there is as much reason for Congress to have

believed that one would be denied his “equal civil rights”

by a system of racially discriminatory jury selection as

by a racially motivated arrest and charge.

45D om brow sM vs. P fister , 227 F . Supp. a t p. 583.

46163 U.S. 537, 41 L,. Ed. 256, 16 S. Ct. 1138 (1896).

4716 W all; 36, 21 K Ed. 394 (1873).

48347 U.S. 483, 98 L. Ed. 873, 74 St. Ct. 686 (1954).

28

Clearly, Judge Bell, below, is hard put to follow the

reasoning of Rives and Powers. He simply did the best

possible job on this point while recognizing the inapprop

riateness of his Circuit Court’s attempting to strike them

down.

Judicial adminstration in that circuit has been sorely

tried by the obstructionist effect of these Plessy type

opinions. Clearly Negroes’ rights are more effectively

protected and the judicial process more properly and ef

ficiently used if the equal protection problems posed by

racially discriminatory jury selection systems are avoided

in the first instance by the simple process of federal re

moval rather than by being dragged through the federal

courts for years by the habeas corpus — appeal —

certiorari method. Certainly the Fifth Circuit in its

recent en banc hearing49 was searching for something

49ln R ives the cou rt recom m ended to th e federa l system th e case-by-case

m ethod of federal review sanctiond by N eal vs. Delaware. T h is m ethod

has proved in practice to be unw ieldy, expensive, and a burden to the

docket. I t has fa iled to produce su b stan tia l ju stice in circum stances of

w idespread d isregard of federa l rig h ts . On D ecember 16th and 17th

1965 the C ourt of A ppeals fo r the F if th C ricu it held a n ex trao rd in a ry

en banc h earin g covering seven ju ry d iscrim ination cases. These ap

peals w ere selected from all over the c ircu it by v ir tu e of th e i r im port

ance. _ These argum ents w ere certa in ly in p a r t designed to aid th e

court in its search fo r a so lu tion to the problem posed to its docket by

th e m ounting num ber of such cases. All five of the s ta te cases w ere

hapeas corpus appeals w hich re lied on th e N eal case, and the records

th e re in clearly showed th e consistency w ith w hich th e requ irem en ts of

th e F o u rteen th A m endm ent for im partia lly selected ju r ie s have been

consisten tly d isregarded in th e S ou thern S tates. The cases heard w ere:

I tT. S. ex rel E dgar Labat vs. B ennett, D kt. No. 22218,

IT. S. C ourt of A ppeals, F if th C ircu it.

2t7. S', ex rel E dw ard D avis vs. D avis, Dkt. No. 21926.

U. S. C ourt of Appeals, F if th C ircuit.

W . S. ex 7-el A ndrew J. Sco tt vs. W alker, Dkt. No. 20814,

U. S. C ourt of Appeals, F if th C ircu it.

iW illie B rooks vs. Beto, Dkt. No. 22809,

U. S. C ourt of A ppeals, F if th C ircuit.

5Jon i R ab inow itz vs, XJ. 8., D kt. No. 21256,

U. S. C ourt of A ppeals, F if th C ircuit.

®Eliza Jackson, et al vs. V. 8., D kt. No. 21345,

U. S. C ourt of A ppeals, F if th C ircu it.

lO rzell B illingsley, Sr. vs. Clayton, D kt. No. 22304,

U. S. C ourt of Appeals, F if th C ircuit.

29

along these lines. Only this court can ultimately restore

this vital federal right of equal protection in jury selection

to the Negro people in an effective and efficient way.

Powers and Rives should be overruled.

5) No only is the Rives-Powers doctrine a facet of

Plessy, but it is another version of abstention in disguise.

In reality, the doctrine was invented (and, given the

legislative history of the removal statute and the realities

of Reconstruction, there can be no other term) to return

jurisdiction of the Negro back to the tender mercies of

the states of the Old Confederacy. It was part and par

cel of the meaning of the Hayes-Tilden compromise of

1877 and suffers today from all the defects inherent in

the state activities and in-activities struck down by the

new decisions limiting abstension.

The old abstention doctrine was too broad and was de

fective in at least two ways.50 “1) it removes the federal

courts from creative participation in the development of

the law, and 2) it could cause the litigants great expense

and delay.” These important issues were all present in

Dombrowski vs. Pfister 380 U.S. 479 (1965) and in the

reapportionment cases beginning with Baker vs. Carr,

369 U.S. 186 (1962). Additionally, the great principal

of having a federal forum and federal proection for fed

eral rights, embodied in the federal removal statute,

and extended by Dombrowski and England,51 is abrogated

by this Rives-Powers version of abstension. As stated in

England:

“Abstention is a judge-fashioned vehicle for ac-

50See P reaus, Note # 8 , 39 Tulane Law R eview 57? a t 579 (1965).

51E ngland vs. La. Bd. o f Med. E xam iners, 375 U.S. 411 (1964).

30

cording appropriate deference to the ‘respective

competence of the state and federal court sys

tems.’ Louisiana P. & L. Co. vs. Thibodaux, 360

U.S. 25,29 79 S. Ct. 1070, 1073, 3 L. Ed. 2d

1058. Its recognition of the role of state courts

as the final expositors of state law implies no

disregard for the primacy of the federal judici

ary in deciding questions of federal law.52 Ac

cordingly, we have on several occasions explicitly

recognized that abstention does not, of course,

invlove the abdication of federal jurisdiction, but

only the postponement of its exercise. Harrison

vs. NAACP 360 U.S. 167, 177. 79 S. Ct. 1025,

1030, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1152___ ”

Shortly after the England decision this court decided

Dombrowski, wherein it was held:

“We hold the abstention doctrine is inappropri

ate for cases such as the present one where, un

like Douglas vs. City of Jeanette,53 statutes are

justifiably attacked on their face as abridging

free expression, or as applied for the purpose of

discouraging protected activities.”

This did no more than logically extend the principal

that where a state statute is unconstitutionally vague,

inhibiting of the exercise of First Amendment freedoms,

and deterring constitutionally protected conduct, federal

district courts may not abstain from adjudication and re

lief. Cooper vs. Hutchinson (1958 CA 3), 184 F. 2d 119;

Baggett vs. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360, 366, 367, 372, 12 L. Ed.

2d 377, 84 Sc. Ct. 1316; Griffin vs. County School Board,

377 U.S. 218, 12 L. Ed. 2d 256, 84 S. Ct. 1226; Davis vs.

Manu 377 U.S. 678, 12 E. Ed. 2d 609, 84 S. Ct. 1453;

52See K urland , Tow ard a Co-operative Jud icia l F edera lism : The Federal

Court A bsten tion D octrine, 24 FR D 1 481, 487.

53319 U.S. 147, 63 S. Ct. 877, 87 L. Ed. 1324.

31

McNeese vs. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 668 10 L. Ed.

2d 622, 83 S. Ct. 1433.

In effect the Congress of 1866 in passing the federal

removal section of the Civil Rights Act declared as a

matter of national legislative policy that in the field of

equal protection for Negroes, there was to be no doctrine

of abstention, and that the federal equal civil rights were

not to be subjected to state adjudication by the former

slave-holding class. As to such rights, the extraordinary

situations that must be present to overcome Section 228354

so that an injunction might issue (as in Dombrowski) are

almost assumed to exist. In effect, the Congress, as

shown in its debates, took legislative notice of the rebel

lious attitudes and defiant disregard by the Southern oli

garchy of the equal civil rights of the Negro. This notice,

as written into the law, recognizes not only state statutes

as obstacles to enforcement of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, but also the actions of the officials, judges and

sheriffs who enforce the law. Actually that Congress did

the same thing the present Congress did when it passed

the 1965 Voting Rights Bill.55 After extensive hearings

wherein the real scope of white suppression of the Negro

voter was exposed, (almost without contradiction), Con

gress set about fashioning a remedy. In doing so it ig

nored the so-called state remedies and immediately in

voked the Federal power in Federal forums. The Eighty-

Ninth Congress found, and this court agreed, in State of

South Carolina vs. Katzenbach (March 7, 1966 opinion)

that “the latter strategem (. . . discriminatory application

of voting test . . .)56 is now the principal method used to

54Title 28 Sec. 2283 U.S.C.

5579 S tat. 437.

56Emphasis added.

32

bar Negroes from the polls.” If the Eighty-Ninth Congress

can find unconstitutional application of state voting laws

the basis for Federal intervention and protection of Four

teenth Amendment voting rights, and if this court can

agree with that Congress, then there is no reason why it

cannot be said that the Thirty-Ninth Congress did not

intend discriminatory application of a state jury system

to justify Federal removal. Finally, there is no reason

why this court should not agree with such policy as set

forth in South Carolina vs. Katzenbach.

B. THE STATUTES ARE UNCONSTITUTIONAL.

1) Given the state of the Mississippi jury selection

statutes, it is difficult to conclude that this system does

not fall prey to even a loose reading of Rives and Poiv-

ers.

Those laws in their pertinent parts read as follows:

Mississippi Constitution Art. 14 Section 264:

“No person shall be a grand or petit juror un

less a qualified elector . . . The Legislature shall

provide by law for procuring a list of persons

so qualified . . .”

Mississippi Code Section 1762:

“Every Male citizen not under the age of Twenty-

One years who is a qualified elector . . . is a

competent juror . . [emphasis added]

Mississippi Code Section 1766:

“The Board of supervisors . . . shall select and

make a list of persons to serve as jurors in the

circuit court . . . as a guide in making the list

33

they shall use the registration book of voters,

and shall select and list the names of qualified

persons of good intelligence, sound judgment,

and fair character . .

Mississippi Code Section 1796:

“A challenge to the array shall not be sustained,

except for fraud, nor shall any venire facias ex

cept a special venire facias in a criminal case, be

quashed for any cause whatever.”

Mississippi Code Section 1798:

“All the provisions of law in relation to the list

ing, drawing, summoning and impaneling juries

are directory merely; and a jury listed drawn,

summoned or impainel, though in an informal

or irregular manner, shall be deemed a legal

jury . .

If the state statutes in West Virginia excluded Ne

groes from jury service, the formal Mississippi jury

structure does no less. The entire machinery of juror

selection in that State is geared to literate voter regis

tration. This scheme was deliberately contrived in 1890

when it was apparent that while Negroes composed near

ly one-half of the electorate, almost four-fifths of them

were unable to read and write. Compared to this, only

one-quarter of the whites suffered from such disability.

The solution was obvious:57 given the guiding principal

of white supremacy, the redeemers of the State simply

drew the Constitution of 1890 so as to require literacy

tests of electors which Negroes could not meet,58

57W harton, op. oit., page 201 w rite s : “By 1890 M ississippi’s D em ocratic

C ongressm en w ere read y to give en thusiastic support to any schem e th a t

would pu t a legal face on the e lim ination of th e N egro vote.”

58For a b rief bu t careful descrip tion of th is device, see V.S. vs. M ississippi

85, S. Ct. 808, 380 U.S. 128 (1965).

34

The second Mississippi plan worked for nearly 65

years, but in 1954, sensing that Brown vs. Board of Edu

cation signaled a revived federal interest in the Negro,

and reading clearly the caveat of the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit in Peay vs. Cox, 190 F. 2d. 123,59

the State tightened the constitutional disenfranchise

ment of the Negro. The Reconstruction Congresses had

struck at the heart of the Southern problem in 1866,

1870, 1871 and 1875. That lesson was not lost on Mis

sissippi. The rule now was that the Negro voter, and

hence the juror, must not, as before, be able only to read

or understand or interpret a 167-page constitution, but

he now had to read and understand and interpret this

amazing document.60 Feeling that this was not enough,

in 1960 the legislature with the help of the selected elec

torate that held the vote, added the requirement that

voters should be of “good character.”61

The federal concern though very late, was justified:

Negro voter registration had dropped from 50% in 1890,

to 9% in 1899, and then to 5% in 1954. Of course, this

was due to the successful operation of the plan, but at

this point the state became the victim of its own success.

The Justice Department stepped in and brought suit to

expose the scheme.

Mr. Justice Black, for this Court, wrote in U.S. vs.

Mississippi:

“It is apparent that the complaint which the

majority of the District Court dismissed, charged

a long standing, carefully prepared, and faith-,

fully observed plan to bar Negroes from voting

in the State of Mississippi, a plan which the reg

59Cert. D enied 342 U.S. 898.

60Sec. 244 of the M ississippi C onstitu tion .

6lSee. 241-A of th e M ississippi C onstitu tion .

35

istration statistics included in the complaint

would seem to show had been remarkably suc

cessful.”

Taken as a whole, the scheme to eliminate the Negro

from the jury box was just as successful. When one

construes the unconstitutional provisions of the Missis

sippi voter and juror selection statutes together (i.e., as

they are written) to the same provisions of the Louisi

ana Laws now found unconstitutional in U.S. vs. Lou-

isiana,62 the conclusion should be that the entire disrepu

table and concocted affair should be brought tumbling

down.

2.) It should be noted here that one of the grounds

specifically relied upon in the Weathers petitions as

grounds for removal is that the entire legal structure

which will conduct petitioners trials, is operated by a

sheriff, a district attorney and a judge put in office by

an election from which Negroes were systematically

excluded.63 Leflore County is a defendant in a pattern

and practice suit,64 and its registrar is one of those sought

to be restrained in U.S. vs. Mississippi, 85 S. Ct. 808,

380 U.S. 128. The Fifth Circuit has just set aside mu

nicipal elections in the case of Hamer vs. Sunflower

(script opinion March 11th, 1966, unreported) where a

pattern and practice finding so closely proceeded an elec

62380 U.S. 128 85 S. Ct. 808 (1965). The South C arolina p lan pushed by

G overnor T illm an, as described by Ju stice B lack in h is opinion in U.S.

vs. M ississippi, w as bu t an im ita tion of the second M ississippi p lan of

1890. See W oodward, O rigins of the N ew South , op. cit., p. 322.

I t should be noted th a t th e 1890 plan w as as m uch directed aga in s t

th e g row ing P o p u lis t m ovem ent w hich drew its support from the

illi te ra te w hites as ag a in s t th e Negro. By 1898, W illiam s vs. M ississippi,

170 U.S. 213 had placed th e stam p of Federa l approval on the whole

s in is te r conspiracy.

63R. 40 (C, 3,) e ) .

64U.S. vs. M ississippi, 339 F . 2d 679.

36

tion that Negroes made eligible by the Federal Court65

had no time to register or qualify as candidates. It

stands to reason that these county officials, who ini

tiated this arrest in the first place, and who can easily

be said, and probably shown, to be participants in the

Mississippi Plan, were not, are not, and cannot be ra

cially impartial. It will be most difficult if not impos

sible for petitioners who have already been denied equal

protection from the sheriff to receive it from the prose

cutor and the judge.

By the explicit exclusion of women by Mississippi Code

Section 1762, the structure of jury selection in that state

clearly becomes unconstitutional. A three judge Federal

Court in the Middle District of Alabama recently held, in