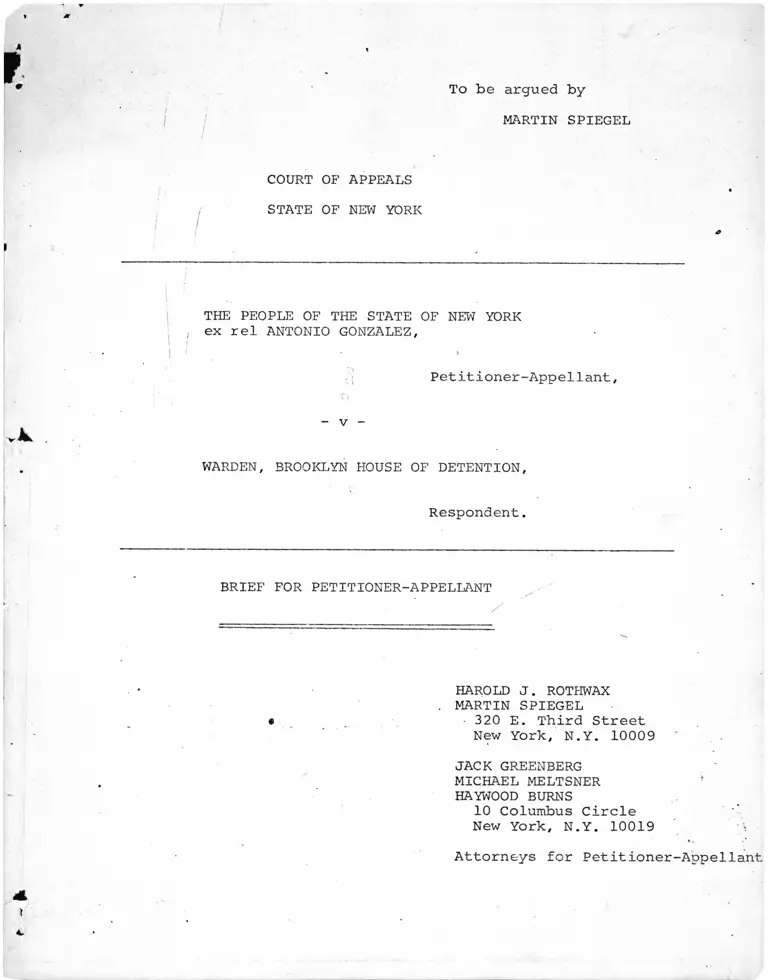

People of the State of New York v. Brooklyn House of Detention Brief for Petitioner-Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. People of the State of New York v. Brooklyn House of Detention Brief for Petitioner-Appellant, 1967. 4ee0ee0d-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/abfe4f7b-3c51-461d-bcd1-318fb46edf36/people-of-the-state-of-new-york-v-brooklyn-house-of-detention-brief-for-petitioner-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

To be argued by

MARTIN SPIEGEL

COURT OF APPEALS

STATE OF NEW YORK

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

! ex rel ANTONIO GONZALEZ,

I

Petitioner-Appellant,

n

- v -

WARDEN, BROOKLYN HOUSE OF DETENTION,

Respondent.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

HAROLD J. ROTHWAX

. MARTIN SPIEGEL

• _ . • 320 E. Third Street

New York, N.Y. 10009

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL MELTSNER * *HAYWOOD BURNS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorneys for Petitioner-Appellant.

I

V • j

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I

Preliminary Statement .............. •................................................................................................................ 1

Questions Presented ................................. 2

Statutes Involved ................................... 2

Statement of Facts ..................................

Argument:

3

Introduction ..................................... 6

iThe Bail Set Is Unconstitutionally Excessive

In That The Evidence Demonstrates Both A Like

lihood Of Appearance And The Existence Of

Non-Financial Conditions Of Release Which Would

Insure Appearance At Trial ...................... 13

* Detention Of Petitioner Solely On Account Of

His Poverty Deprives Him Of Equal Protection

Of The Law ...................................... 19

Pre-trial Detention Denies Petitioner Due

Process of Law As Guaranteed By The Fourteenth

Amendment In That (A) He Is Punished Without

Trial And In Violation Of The Presumption Of

Innocence And (B) He Is Prejudiced At Trial,

And Deprived Of Fundamental Fairness In The

Guilt Finding And Sentencing Process .... ........ 27

The Eight Amendment As Incorporated In The

Fourteenth Grants A Broad Right To Pre-trial

Release Which May Not Be Foreclosed Simply

Because Of Poverty .............................. 34

Conclusion .......................................... 53

• . V - - - - - r . . . . 1 ' . . .i

COURT OF APPEALS

STATE OF NEW YORK

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW

YORK ex rel ANTONIO GONZALEZ,

Petitioner-Appellant,

I /| ' - v -

i i ]

WARDEN, BROOKLYN HOUSE OF DETENTION,

Respondent.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

Preliminary Statement

Petitioner, Antonio.Gonzalez, appeals, pursuant to

- Section 5601 (13) (l),of the Civil Practice Law and Rules frpm

a judgment and order of the Appellate Division, Second Depart

ment, on October 25, 1967, which dismissed a writ of habeas

corpus issued on October 23, 1967 by the Honorable James D.

Hopkins, an Associate Justice of that Court, and remanded

petitioner to the custody of respondent. The Court wrote

no opinion.

A timely notice of appeal was served on October 26,

1967.

Questions Presented

1. Whether the courts below required constitutionally excessive

hail in the light of facts which demonstrate a likelihood

of appearance and the existence of non-financial conditions

of release which would reasonably assure that petitioner

would appear.

2. Whether detention of petitioner solely on account of his

poverty deprived him of equal protection of the laws.

3. Whether pre-trial detention denied petitioner due process

of law in that (a) he is being punished without trial, in

violation of the presumption of innocence, without any

showing of necessity and (b) he is prejudiced at trial

and deprived of fundamental fairness in the guilt finding

and sentencing process.

. I

Statutes Involved

• . ' __ . . . . . . . . . •

New York Code of Criminal Procedure, Section 553. In what

cases defendant may be admitted to bail before conviction. If

the charge be for any crime other than as specified in section

five hundred and fifty-two he may be admitted to bail, before

t

2

Jconviction, as follows:

1. As a matter of right, in cases of misdemeanor;

2. As a matter of discretion, in all other cases; the

court may revoke bail at any time where such bail is dis-

I i

cretionary with the court.

Statement of Facts --------------'

On, August 23, 1967, Antonio Gonzalez was arrested by

Detective Bernard Geik of the New York City Police Department,

and charged with assault and robbery upon an officer. He has

been in custody continuously since August 23, 1967. Detective

Mitsch, the injured officer was working in an undercover

capacity, disguised as a drug addict and attempting to purchase

narcotics. Apparently some persons, who had pretended that

they were going to sell Detective Mitsch heroin, tried to flee

with the money Mitsch had paid them. Detective Mitsch, trying

to regain his money, ultimately drew his gun, and a number of

persons, including petitioner Gonzalez, tried to stop and

disarm Mitsch. He was badly beaten and his gun was taken.

One of the issues of the trial will be whether Mr. Gonzalez

knew that Mitsch*was a police officer,- or reasonably believed

that he was a drug addict who was attempting to rob another

person at gunpoint.

Mr. Gonzalez was arraigned on August 23, 1967 in the

Criminal Court of the City of New York. His bail was set at

3

$25,000. At various stages, the bail was reduced in the

Criminal Court. By September 28, 1967 it had reached $2,500.

Because this amount was far in excess of what Mr. Gonzalez

could afford, on October 10 an application was made before

Justice Arthur Klein, presiding in Part 31 of the Supreme

Court, New York County, for a reduction of bail. Justice Klein

reduced bail to $1,500. On October 16 Judge Daniel Hoffman,

of the New York City Criminal Court reduced the bail to $1,000.

\ I t -On October 16, Justice Darwin Telesford signed a writ of habeas

corpus returnable in th} Supreme Court, Kings County. On

October 20, 1967, after hearing argument of counsel, Justice

Vincent Damiani dismissed that writ, saying that under the

circumstances, he found that the bail was reasonable.

On October 23, 1967, the instant writ of habeas corpus

was signed by Associate Justice James D. Hopkins of the Appellate

Division, Second Department. On October 25, 1967 a hearing was

held before the Justices of the Appellate Division. Counsel for

. . . I 1petitioner informed the Court that the -relator was 19 years of

age and had no previous criminal record, that he had come to

New York from Puerto Rico three years ago, that he had lived

with his father, brother and sister at 734 East 5th Street,

•Manhattan, for the past two years, that, he was employed as a

clerk by Mobilization For1 Youth at a salary of $45.00 per week

Jand was attending classes there in remedial reading and job

training, and that present in Court was a social worker, em

ployed by Mobilization For Youth, who. had known Jdjî ---GoTTZairez:— >.

- .4

for two years and who agreed to supervise petitioner if he

were released. Counsel informed the Court that Mr-r* Gonzalez

had $100, which had been collected among friends and relatives

to be used for bail, and that he was in jail solely because

he lacked the funds necessary to secure a $1,000 bail bond.j j

The Assistant District Attorney, appearing for Respondent,

conceded that the facts as stated by petitioner's counsel

were correct to his knowledge. After hearing counsel, the

Court deliberated privately and then informed counsel that

the writ was dismissed.

5

Introduction

In recent years, the American money bail system has

/been the' subject of increasing criticism and concern from

i/the informed public. More than any other aspect of the

criminal process our practice of attempting to increase the

likelihood of appearance at trial by means of a financial

test, administered by professional bondsmen, has aroused

criticism from individua s and organizations concerned with

nthe criminal law. The nation's chief prosecutor has character-

2/ 3/

ized the money bail system as "cruel" and illogical." Judges, * *

1/ At least two conferences have been organized to consider all

aspects of the bail system, a reflection of that widespread

concern. See, Proceedings of the Conference on Bail and

Indigency, 1965 U. 111. L. Forum, #1; Nation Conference on

Bail and Criminal Justice, Proceedings and Interim Report

(1965)[hereinafter cited as National Bail Conference]; cf.

Conference Proceedings, National Conference on Law and Poverty

(1965).

2/ Address by the Honorable Robert F. Kennedy, Attorney General,

National Bail Conference 297 (1965).

3/ Botein, The Manhattan Bail Project: Its Impact on Criminology

* and the Criminal Law Processes, 43 Tex. L. Rev. 319 (1965)

(an approving commentary upon the first movement which succeeded

in translating criticism into reform); see also Justice Botein's

address to the National Conference on Bail and Criminal Justice,

National Bail Conference 18; McCree, Bail and the Indigent

Defendant, 1965 U. 111. L. Forum 1 (the inadequacies of money

bail led the writer and other United States District Judges

sitting in the Eastern District of Michigan to establish a

successful release-on-recognizance program).

6

4 / 5 / 6/

scholars, administrators and private researchers have

concurred in questioning both the operation, the assumptions

and the constitutionality of the money bail system, and in

calling for its reform.

Recent writings, for example, agree that monetary bail

is inefficacious as a means of assuring the presence of an

accused at trial. Freed & Wald, Bail in the United States:

1964, A Report to the National Conference on Bail and Criminal

Justice 49-55 [hereinafter cited as Freed & Wald]; Area, Rankin

and Sturz, The Manhattan Bail Project: An Interim Report on

the Use of Pre-trial Parole, 38 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 67, 90 (1963); •

4/ Foote, The Coming Constitutional Crisis in Bail, 113 U. Pa..

L. Rev. 959, 1125 (1965) (a reexamination of the meaning of

the Eighth Amendment's prohibition of excessive bail in a

historical perspective, and an inquiry into the relationship

between the proper Eighth Amendment standards and current

bail abuses)[hereinafter cited as Crisis in Bail]; Beeley,

The Bail System in Chicago 160 (1927); Allen, Poverty and the

Administration of Federal Criminal Justice, Report of the

Attorney General's Committee on Poverty and the Administration

of Federal Criminal Justice 58-89 (1963); Ares, Bail and the

Indigent Accused, 8 Crime and Delin. 12 (1962).

5/ Mann, 1965 U. 111. L. Forum 27-32 (bail bonds totally obsolete

and represent the "tilted scales of justice," in the words of

the Chief Probation and Parole Officer of the St. Louis, Mo.,

Circuit Court for Criminal Causes); Ares, Rankin and Sturz,

• The Manhattan Bail Project: An Interim Report on the Use of

Pre-Trial Parole, 38 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 67 (1963); Sills, A Bail

Study, for New,Jersey, 87 N.J.L.J. 13 ,(1964).

6/ McCarthy and Wahl, The District of Columbia Bail Project:

An Illustration of Experimentation and a Brief for Change, 53

Geo. L.J. 675 (1965); Goldfarb, Ransom — A Critique of the

American Bail System (1965); Freed & Wald; The Bail System of

the District of Columbia (j r . Bar Sec., D.C. Bar Ass'n 1963).

7

Note , Bail: An Ancient Practice Reexamined, 70 Yale L.J.

966 (1961). It has been noted that in most cases the decision

as to whether an accused will be released prior to trial is

effectively delegated to a professional bondsman whose decision

to release an accused is unrelated to the likelihood of flight

and indeed relates only to his own profit motive- See Report

of the 3d February 1954 Grand Jury of New York County, New York

to Honorable John A. Mullen at 2-3; Freed & Wald 22-38; Report

of the May, 1960 County Grand Jury .of the Circuit Court of

Jackson County, Missouri; Bail or Jail, Criminal Court Committee

of the Ass'n of the Bar of the City of New York, 19 The Record 11

(Jan. 1964). The cost of pre-trial imprisonment in terms of

time, public funds, employment, education, and human suffering

is staggering. See Freed & Wald 39-48; National Bail Conference

63-65; Goldfarb, No Room in the Jail, The New Republic, March 5,

1966, p. 12; Foote, Compelling Appearance in Court: Administration

of Bail in Philadelphia, .102 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1031 (1954) [herein

after cited as Philadelphia Bail Study]; Foote, A Study of the

Administration of Bail in New Yo-rk City, 106 U. Pa. L. Rev. 693

(1958) [hereinafter cited as New York Bail Study]; Rankin, The

Effect of Pre-Trial Detention, 39 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 641 (1964).

.This extensive Research has amply documented that the bail

setting process is often abused to punish prior to trial, to

give an accused "a taste of jail," or"to make an example."

Hearings on S, 1357, S. 646, S. 647 and S. 648 Before the Sub

committee on Improvements in Judicial Machinery of the Committee

on the Judiciary, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. 3, 66, 130 (1965); Note,

Preventive Detention Before Trial, 79 Harv: L. Rev. 1475 (1966)

8

!. ‘ • •*

New York Bail Study 705; Philadelphia Bail Study 1039.

Criticism has not, however, been limited to the operation

of the present system. The system itself has been questioned

on a variety of constitutional grounds by most of those who have

observed it in operation. Commentators have challenged the

constitutionality of denying pre-trial liberty to an accused

solely on account of his poverty; of punishing the indigent

through pre-trial imprisonment with its correlative presumption

not of innocence but of guilt, although he alleges he is not

guilty; of detaining the indigent accused when the detention

itself may adversely affect the disposition of his case and

deprive him of a fair trial. In light of a constitutional pro

hibition against excessive bail setting, it has been said that

bail in excess of what a defendant can afford, or bail set

without consideration and express rejection of non-financial

means of increasing the probability of appearance at trial is

constitutionally excessive. A combination of the substantial

constitutional doubts raised with respect to the bail system as

a whole and the overwhelming body of evidence documenting the

practiced abuses of the system led Congress in 1966 to enact the

Bail Reform Act of 1966. The Act requires that an accused

shall be released on his own recognizance or an unsecured promise

to pay unless the United States Commissioner or judge finds that

an accused would not be reasonably likely to appear. Even if

it is determined that an accused is not likely to appear if

released on his own recognizance, the judge or commissioner can

only require secured money bail if he finds a variety of non-

financial conditions of release will not insure the presence of

I

9

the accused. Thus, Congress has responded to a need for

reform by ameliorating the money bail system and providing

that wherever possible release on nonfinancial terms shall

be proper. The Supreme Court of the United States has

responded to this criticism in dramatic fashion in the most

recent bail cases to come before it; In Re Shuttlesworth,

369 U.S. 35 (1962); Bitter v. United States, 36 U.S.L. Week

3159 (October 16, 1967).

Shuttlesworth was convicted of disorderly conduct arising

out of efforts to test the constitutionality of segregat’on of

Uthe Birmingham transit system and was sentenced to pay $100

and costs or serve 82 days. His conviction was affirmed by

the Alabama Court of Appeals without consideration on the merits

of his challenge to the constitutionality of the disorderly

ordinance as applied, because his filing of the transcript of

evidence was untimely under Alabama practice. The Supreme

Court of Alabama and the Supreme Court of the United States

denied certiorari. Shuttlesworth then sought habeas corpus in

the District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, which

denied relief on the ground that untimely filing of the tran

script on the state appeal had forfeited the constitutional

claim. Without^reaching this question, Judge Rives denied a

certificate of probably cause on the ground that state collateral

relief by habeas corpus or coram nobis appeared to be available.

A motion for leave to file an original petition for habeas corpus

was filed in the Supreme Court, which disposed of the matter

by holding that state judicial proceedings which failed to reach

10

the petitioner's claims or effect his release within five

days were thereby ineffective and insufficient to justify

further delay of federal jucicial relief. Shuttlesworth

stands for the proposition that release on bail is so

significant a part of the criminal process that a federal

court will entertain the merits of a federal habeas petition,

not withstanding the exhaustion of remedies doctrine, if

release is not obtained expeditiously in state courts.

In Bitter, supra, the Supreme Court took the unusual

step of reversing a conviction on the ground that pre-conviction

liberty on bond (or recognizance) had been unjustifiably

revoked. The defendant's liberty had been revoked during

trial when' he returned late to a court proceeding and he was

subsequently incarcerated at a jail 40 miles from the court

room. The court found revocation of liberty in the circumstances

of the case amounted to unjustifiable punishment unrelated to a

significant interference with trial processes; and that it

constituted an "unwarranted burden upon defendant and his

counsel in the conduct of the case."

Of course, neither Shuttlesworth or Bitter address them

selves directly to the merits of this case but their results

do speak eloquently of an awareness that the operation of the

bail system deserves careful scrutiny to insure conformity

with evolving concepts of due process of law and equal protec

tion of the laws.

In the submission which follows we urge first, that given

the facts which demonstrate a likelihood of appearance and the

11

existence of nonfinancial conditions of release which would

increase the likelihood of appearance, the lower courts required

constitutionally excessive bail. We ask this court to instruct

lower courts to determine expressly, on the basis of the evidence|

before them, that no available nonfinancial alternative will

*reasonably insure appearance before approving a financial test

for an indigent's pre-trial release.

Secondly, we urge that detention of petitioner solely on

account of his poverty deprives him of equal protection of the

laws.

Thirdly, we urge that pre-trial detention denies petitioner

due process of law in that (a) he is punished without trial and

in violation of the presumption of innocence without any showing

of overriding necessity and (b) he is prejudiced at trial and

deprived of fundamental fairness in the guilt finding and

sentencing process.

A final section of this brief contains a discussion of

historical and other materials which demonstrate that the

Eighth Amendment as incorporated in the Fourteenth grants a

broad right to pre-trial release which may not be foreclosed

to the poor.

12

I

The Bail Set Is Unconstitutionally

Excessive In That The Evidence

Demonstrates Both A Likelihood Of

Appearance And The Existence Of

Nonfinancial Conditions Of Release

Which Would Insure Appearance At

Trial.

The only legitimate purpose of a pre-trial bail requirement

is to decrease the risk that a defendant will fail to appear at

trial, Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1, 5 (1951). Bail is not to be

1 /used as an instrument of punishment, and whenever bail is made

to serve a purpose for wh ch it was not intended, it becomes

excessive, Cohen v. United States, 7 L.ed 2d 518, 82 S. Ct. 526

(1962) (Douglas J.). Bail is a device to insure liberty, not

detention:

This traditional right to freedom before

conviction permits the unhampered prepara

tion of a defense, and serves to prevent

the infliction of punishment prior to

conviction. . . Unless this right to bail

is preserved, the presumption of innocence,

secured only after centuries of struggle,

would lose its meaning. Stack v. Boyle,

supra at 4.

All the evidence in this case demonstrates the extreme

unlikelihood of non-appearance. Petitioner's character and

roots in the community are totally inconsistent with flight.

The accused is 19 years old. For the past two years

he and his brother and sister have lived with their father

at the same address on New York's lower east side. Petitioner's

mother is deceased. At time of the events leading to his arrest

he was working as a clerk for Mobilization for Youth, Inc., an

anti-poverty organization with offices on the lower east side.

13

With his earnings of $45.00 per week he helped his father support

the younger children in the family. Mr. Gonzalez also attended

classes in remedial reading and job training sponsored by

Mobilization in order to improve his situation.

Thus, at the time he submitted to arrest and incarceration,

the defendant, a teenage youth (1) had steady employment (2) was

helping to support his family, (3) was attending educational

classes, (4) had lived at the same address with his family for

a period of years in the same neighborhood as he worked. It

is difficult to conceive of a person less likely to flee the

jurisdiction.

The record below also reflects upon the defendant as a

person. He is a young man without a criminal record who,

according to the arresting officer, when he realized he was

wanted for a crime made a full statement and was fully coopera

tive.

Whether the accused's involvement in the instant prose

cution amounts to a criminal violation is, of course, an issue

for the trial jury and not for a bail setting court. One of

the issues at trial, however, will be whether Mr. Gonzalez knew

that Detective Mitsch was a police officer, or reasonably

believed that he was a drug addict who was attempting to rob

another person at gun point. This is not a case where conviction

is, by any means, assured.

While there is substantial evidence of roots in the

community, in all proceedings below, though opposing reduction

14

• I

II „ ■ .i

of bail, the state has not been able to produce evidence to

show a likelihood of flight. Given the purpose of bail, to

secure pre-trial liberty rather than detention, the state

must come forward with evidence to show that it is likely a

defendant may flee before a bail figure which resuits in deten

tion is sustained. In the instant case, aside from the bare

accusation, the only factor which the state has been able to

point to is the fact that prior to three years ago petitioner

lived in Puerto Rico. Detention on the basis of this factor

alone is untenable; it would effectively deny release to Puerto

Ricans residing in New York, regardless of their roots in the

state.

Under the law of New York if the lower court had felt that

there was evidence that the accused would not present himself

voluntarily at the time of trial it could have denied bail

altogether. N. Y. Code of Crim. Proc. §553. Evidentally this

was not the judgment of the courts below because bail has been

set. In point of fact the accused has remained in jail for the

last nine weeks and is in jail presently, not because if

released he can be expected to flee (if that were the case the

bail would be far more than $1,000.00) but because he is too

impecunious to afford the ransom the state seeks to extract.

In view of the historical background of our bail system,

its purpose, and constitutional principles against discrimination

on the basis of poverty, sound construction and policy requires

that the courts refrain from exacting financial conditions for

pre-trial release when nonfinancial conditions would accomplish

15

the same purpose. For example, in the instant case, Mr.

Elwood Jefferson, a social worker who has known petitioner

for two years stated that he would supervise petitioner if he

were released prior to trial. Where the evidence shows that

there are non-monetary conditions of release which will result

in appearance without detaining an accused, the courts should

be bound to choose them.

I ;In addition to parole in the custody of the social worker

|the courts below had a number of nonfinancial alternatives to

the imposition of money bail on this indigent defendant. The

federal Bail Reform Act of 1966 is perhaps the best existing

model of a pre-trial release system in use. The Act provides

that, in noncapital cases, a person charged with a crime

shall be released on his personal recognizance or upon the

execution of an unsecured appearance bond. If the judicial

officer expressly determines that such a release will not

reasonably assure the appearance of the person, he may either

in lieu of or in addition to the above methods impose another

condition or combination of conditions which will assure

appearance — resorting to the least stringent that will

accomplish the desired purpose. These conditions include:

(1) placing the person in the custody of a designated

person or organization agreeing to supervise him;

(2) placing restrictions on the travel, association,

or place of abode of the person during the period

of release;

(3) requiring the execution of an appearance bond in a

16

I ' • • ' *

i - ; 1

j . j

specified amount and the deposit in the registry

of the court, in cash or other security as directed,

of a sum not to exceed 10 per centum of the amount

of the bond, such deposit to be returned upon theI •

performance of the conditions of release;

(4) requiring the execution of a bail bond with sufficient

solvent sureties, or the deposit of cash in lieu

thereof; or

(5) imposing any other condition reasonably necessary

to assure appearance as required, including a

condition requiring that the person return to custody

after specified hours.

(18 U.S.C. §3146)

The Bail Reform Act of 1966 is cited because it is

illustrative of the range of possibilities open to courts for

imposing nonfinancial conditions of release, conditions which

are well within the broad range of discretion of the lower

courts. Faced with an indigent accused who showed no likelihood

of fleeing, the courts below should have imposed one or more of

the nonfinancial conditions of release that were open to them.

If the petitioner failed to comply with these conditions, the

9 ' ' _-- ■ -- '

court could then revoke release pursuant to its powers under

§553(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

Thus, it is petitioner's position that the setting of

bail conditions more onerous than are reasonably necessary

to result in a defendant's appearance constitutes the imposition

of an excessive bail within the meaning of the Eighth and

17

Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and

Article I, Section 5 of the New York State Constitution.

It may be argued by the District Attorney that the refusal •

of the lower courts to lower bail further may be taken as the

product of their judicial finding that none of the non-monetary

methods described above are sufficient to secure petitioner's

appearance. However, since the bail standards urged here have

never been articulated by an appellate court in New York, there

is absolutely no reason to infer that such a standard was

applied. Furthermore, the record is bare of any such finding

by the lower court. Finally, it is submitted that on the facts

of the instant case, such a determination would be without

basis. Cf. People ex rel. Deliz v. Warden, 260 App. Div. 155,

21 N.Y.S. 2d 435 (1940).

18

II

Detention of petitioner Solely

On Account Of His Poverty Deprives

Him Of Equal protection Of The Law*I / >

’ ;

The equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution commands that distinctions drawn by

a State — - whether in the exaction of pains or in the allowance of

benefits — must not be irrelevant, arbitrary or invidious, VJhere

i /a state chooses to grant an advantage to one class and not to

others, « * The attempted classification* * *must always rest

upon some difference which bears a reasonable and just relation to

the act in respect to which the classification is proposed, and can

never be made arbitrarily and without any such basis*" Gulf, uColorado, and Santa Pe Ry* v* Ellis, 165 U*S* 150, 155, 159 (1897)*

See, e*g., Skinner v, Oklahoma, 316 U«S* 535 (1942); Baxstrom v.

HeroId, 86 S* Ct* 760 (1966)* .

The lesson of these cases is that there can be no difference

in treatment, unless there is a rational distinction between the

classes affected* or, to put it another way, where no rational

i .

u "But arbitrary selection can never be justified by calling it

classification* The equal protection demanded by the 14th

Amendment forbids this. No language is more worthy of

frequent and thoughtful consideration, than Mr. Justice

Matthews speaking for this court, in Yick No v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 356, 369: ’When we consider the nature and the

theory of our institutions of government, the principles

upon v,hich they are supposed to rest, and review the history

of their development, we are constrained to conclude that

they do not mean to leave room for the play and action of

purely personal and arbitrary power*" 165 U.S* at 159,

- 19 -

distinction exists between two persons or classes, the lav; must

treat them alike. As Mr. Justice Black stated in Griffin v.

Illinois, /351 U.S. 12 (1956) at 17-13:

. . . our own constitutional guarantees of

due process and equal protection both call

for procedures in criminal trials which

allow no invidious discriminations between

| persons and groups of persons, Both equal

! | , protection and due process emphasize the

j / central aim of our entire judicial system

— all people charged with crime must, so

far as the la ; is concerned, 1 stand on an

equality before the bar of justice in every

American court.1

Any lav; which fails to abide by that basic principle of

American jurisprudence is, of course, unconstitutional and hence

void.

The relevance of these general principles to the issue here

under discussion is clear. Petitioner is being detained in jail

for no reason other than his poverty. Not only does this

detention deprive him of his greatest right of all — - his liberty

— without trial, conviction and sentence, but as discussed infra

experience demonstrates that he suffers, by reason of his pre

trial incarceration, significant consequence which infect the«

fairness and equality of the fact finding and sentencing pro- '

ceedings which follow his incarceration. Petitioner submits that

his continued incarceration, solely because ha is not a rich man,

denies him equal protection of the laws as guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

20

■£n impressive series of recent decisions strikes down under

%the Equal Protection Clause various state practices which deny

indigent criminal accuseds substantial procedural advantages which

those who can pay for them may obtain. Griffin v^Illinois, 351

U.S. 12 (1956) (denial of free criminal trial transcript necessary

for adequate appellate review) ? Eskridge v. Washington State Board,

357 U.S. 214 (1958) (denial; absent trial court finding that

i \ j j“justice will thereby be promoted." of free criminal trial tran-

script necessary for adequate appellate review) 7 Draper v.

Washington, 372 U.S. 487 (1963) (denial, on trial court finding

that appeal is frivolous, of free criminal trial transcript

necessary for adequate appellate review)? Lane v» Brown, 372 U.S.

477 (1963) (denial, absent public defender's willingness to prose

cute appeal from denial of state coram nobis petition, of free

transcript of coram nobis proceeding necessary to perfect state

appellate jurisdiction)? Douglas v, California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963)

(denial, absent appellate finding that appointment of counsel on

appeal would be of value to defendant or the appellate court, of

free-appointment of counsel on appeal as of rights from criminal

conyict?.on) ; Eurns <v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252 (1959) (denial, in default

of $20.00 filing fee, of motion for leave to appeal a felony con

viction) ; Smith v. Bennett, 365 U.S. 708 (1961) (denial, in default

of $4,00 filing fee, of leave to file habeas corpus petition);

Rincald v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1966) indigent sentenced to prison

may not be forced to pay for appeal transcript out of prison

- 21 —

II

earnings). See also Long v. District Court of Iowa, 385 U.S.

192 (1966); People v. Saffore, 18 N.Y.2d 101, 218 N.E.2d 685

(1966); People v. Montgomery, 18 N.Y.2d 993, 278 N.Y.S.2d 226,I

224 N.E.2d 730 (1966). These decisions establish, as stated

in.Griffin, that within the meaning of the equal protection

clause "There can be no equal justice where the kind of trial

a man gets depends on the amount of money he has" 351 U.S. at 19.

Applying the principle to an indigent's request for

release on his recognizance pending appeal from conviction,

Mr. Justice Douglas stated the question: "Can an indigent

be denied freedom, where a wealthy man would not, because he

does not happen to have enough property to pledge for his free

dom?" Bandy v. United States, 81. S. Ct.. 197, 198 (Douglas

J. 1960). He subsequently answered the question in the nega

tive, concluding that "no man should be denied release because

of indigence. Instead, under our constitutional system, a roan

is entitled to be released on 'personal recognizance' where

other relevant factors make it reasonable to believe that he

will comply with the orders of the Court." Bandy v. United

States, 82 S. Ct. 11, 13 (Douglas, J. 196T) .

-------------------------------------------•----------------------:— • ---------- ; — — ‘— •— — . . . . . ■ . - v - ■

8/ The first Bandy decision, on application for release on recog

nizance pending certiorari to review affirmance of Bandy's

conviction by a court of appeals, was filed by Mr. Justice

Douglas on the same day that the Supreme Court vacated the

court of appeals' judgment and remanded the case to that court

for further consideration of the appeal on the merits. In

light of this development, Justice Douglas denied the applica

tion without prejudice to its renewal in the court of appeals.

81 S. Ct. 197, 198. The court of appeals subsequently denied

such an application, and in the second Bandy opinion, not

withstanding his view that the denial was unconstitutional,

22

That the system of conditioning pre-trial release on financial

bail is a long-suffered discrimination running back to the days ox

medieval unconcern for the impoverished/ does not insulate it from

condemnation, under the Fourteenth Amendment. The argument from

traditions

reflects a misconception of the function of

the Constitution and this Court's obligation

in interpreting it. The Constitution of the

i United States must ba read as embodying

I general principles meant*to govern society

and the institutions of government as they

evolve through :ime, It is therefore this

Court's function to apply the Constitution

as a living document to the legal cases and

controversies of contemporary society.

(White v. Crook/ 251 F. Supp. 401/ 408

(H.Do Ala. IS68) (three-judge court)).

Recently, the United States Suprem

time-honored poll tax of $1.50 as

s Court struck down Virginia's

a prerequisite to voting in state

elections on the ground that "Voter qualifications have no relation

8 (Con'to) Justice Douglas again refused release on recogni

sance, on the theory that —— a petition for certiorari seeking

review of the court of appeals' adverse determination having

been filed -- an individual Justice ought not anticipate and

"moot” the issue before the full Court. Apparently, the paper

filed by Bandy which Mr.•Justice Douglas believed to be a

petition for certiorari was rather a petition for leave to

file an original petition for habeas corpus. The Court sub

sequently den fed that petition, With d-lr. Justice Douglas

dissenting on the ground of his Bandy II opinion. Bandy va

i2ll£ea_States, 369 U.S. 815 (1952). Although the C ^rt/Tn

denying tine relief sought, cannot but have been aware of the

issue framed by Justice Douglas, it is impossible to sav

s views orwhether it considered and rejected the Justice' w

whether it denied the petition on some available procedu: ground. il

- ‘23 -

*

to wealth nor to paying or not paying this or any other tax"

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U0S0 663 (1966)c

In finding yealth a "capricious" and "irrelevant factor" the Court

addressed itself to the contention that the poll tax v/as “an old

familiar form of taxation" and rejected history as sufficient to

support discrimination on the basis of property*

I ' I ' In determining what lines are unconstitutionally

I ! discriminatory, we have never been confined

to historic noti< ns of equality, any more

than we have restricted due process to a

fixed catalogue of what was at a given time

deemed to be the limit of fundamental rights«.

See Malloy v c Hogan, 373 U 0S0 1. 5-6o Notions

of what constitutes equal treatment for

purposes of the Equal Protection Clause do

change (emphasis in original).

Thus, notwithstanding ancient abuses against the poor, the

Constitution today decrees that the financial position of one

charged v/ith crime shall have no place in determining the character

of treatment he receives from the state0 This is especially true

with respect to pre-trial liberty of an accused for: "the function

of bail is limited, (and] the fixing of bail for any individual

defendant must be based upon standards relevant to the purpose of

assuring the presence of that defendant#" Stack v„ Boyle, 342 U.S,

1* 5 (1951) (emphasis added)„ Fixing bail for petitioner in an

amount which he cannot pay because of poverty is not basing bail

upon "standards relevant" to the purpose of assuring his presence.

It is to deny him release and continue his incarceration until trial

in violation of his right to bail under the Constitution and laws

24 -

. J ?lr-

I • ■:

I . j ■ . •

of. the State and the United States.

It is ironic that we freely provide an indigent with

transcripts and lawyers after conviction but deny them pre

trial liberty solely because of poverty. Such a result converts

the bail system into a device which detains as many poor per- *

sons as possible rather than "a procedure the purpose of which

is to enable-them to stay out of jail until a trial has found

them guilty" Stack v. Boyle, supra, cf. Bail Reform Act of 1966,

89-465; 80 Stat. 214. It is an invidious discrimination, and

denies petitioner in the most obvious and offensive way his

constitutional right to equal protection of the laws. Under

the laws of the State of New York the lower courts could have

denied bail if there was any evidence suggestive that Mr. Gonzalez

would not be likely to appear, N.Y. Code of Criminal Procedure

§ 553. To set bail at a figure which cannot be met, once bail

is set, only results in detaining the poor; not those likely to

flee. In Griffin, supra and Douglas, supra the state urged

that free transcripts and appointment of attorneys could be

denied to the poor because there is no constitutional right

f

to appeal. The Supreme Court rejected these contentions holding

that as long as the state granted an appeal access to the Appellate

Court could not be denied on the basis of wealth. In light of

these decisions, we fail to see how the state can justify with

holding pre-trial liberty once it has been determined, by setting

bail in the first place,that release is justified.

In People v. Saffore, 18 N.Y.2d 101, 218 N.E.2d 686 (1966),

25

this Court held that imprisonment on an indigent convicted

defendant in excess of the one year statutory maximum for his

misdemeanor offense, because of his financial inability to pay

a fine, violated his right to Equal Protection of the Laws as

well as the constitutional ban against excessive fines.

<

The analogy to the bail area is plain. No meaningful dis

tinction can be drawn between over-the-statutory-maximum imprison

ment for inability to pay a fine, and imprisonment for inability

to provide bail money before conviction. As Mr. Justice Jackson

has said: "The practice of admission to bail as it has evolved

in Anglo-American law is not a device for keeping persons in

jail upon mere accusation until it is found convenient to give

them a trial. On the contrary, the spirit of the procedure is

to enable them to stay out of jail until a trial has found them

guilty." Stack v. Boyle, supra at pp. 7, 8.

26

Ill

Pre-trial Detention Denies Petitioner

Due Process of Law As Guaranteed By

The Fourteenth Amendment In That (A) He

Is Punished Without Trial and In Viola

tion of the Presumption of Innocence and

(B) He is Prejudiced At Trial, and

Deprived of Fundamental Fairness in the

Guilt Finding and Sentencing Process.

Pre-trial detention punishes petitioner, a criminally accused

indigent, without trial and prejudices the fact-finding, guilty-

determining and punishment-setting processes through which he

passes against impartial evaluation of his case.

That pre-trial detention imposes punishment is obvious.

Bitter v. United States, J6 U.S.L. Week 3159 (October 16, 1967).

A jailed accused loses his liberty, the most precious of rights,

as completely as does any convict. Petitioner, for example, has

been subjected to severance of family relations, loss of pay,

loss of employment, and loss of educational opportunity. The

conditions in available pre-trial detention facilities are normally

inhumane. An accused is often subjected to poor food and housing,

overcrowding, inadequate recreational and other facilities, essen

tial rudimentary comfort and decency. " [A]t the time an accused

is convicted and sentenced to imprisonment, his standard of living

JL/is almost certain to rise." As the National Conference on Bail

and Criminal Justice put it:

9 / Other common restrictions of the detention jail are censor

ship of mail, restrictions on newspapers and periodicals,

a frequently total prohibition on the use of the telephone,

inadequate facilities for confidential conversations with ■-

lawyers and others, including restricted visiting privileges

only for close relatives and restriction of visits to times

which are particularly inconvenient to members of

27

"His horn3 may be disrupted, his family

humiliated, his relations with wife and

̂_ children unalterably damaged* The man

who goes to jail for failure to make

bond is treated by almost every juris

diction much like the convicted criminal

i serving a sentence" (Bail in the United *

States: 1954, 43 (Nat'l Conference on

Bail and Criminal Justice)),

To force one not convicted of crime to suffer punishment of

this magnitude for no reason other than poverty is shocking and

violates fundamental principles of due process„ Unless pre-trial

freedom is assured "the presumption of innocence, secured only after

centuries of struggle, would lose its meaning" Stack v* Boyle, 342

UcSo 1, 4 (1951), Our system of justice does not permit incarcera

tion because of a supposed risk of flights "that is a calculated

risk which the law takes as the price of our system of justice* . *

[Tjha spirit of the procedure is to enable [defendants] to stay out

of jail until a trial has found them guilty" jCd, at 8 (separate'

opinion) * .,

It is vicious enough, then, to commit to a jail an indigent

accused who may never be sentenced to any imprisonment upon convic

tion by due course of law because after serving his pre-trial jail

term ho is either net convicted or, if convicted, has his case

2,/ (Con'ti) the working class, Foote* concludes that "these

limitations are as unnecessary to the legitimate purpose of

•detention -- security — as is the line up and in their con

tempt for man's dignity and their probable tendency to coerce

guilty pleas far more pernicious as a contamination of the .

values for which due process stands, Whether or not such

restrictions are deliberately intended to punish and humiliate,

they certainly have that effect and some judges use pre-trial

detention explicitly for punitive purposes0 For example, to

give the accused 'a taste of jail,"’

28

concluded by a disposition that does not include imprisonment.

10/There are many such appalling cases. It is, however, far more

serious and clearly a violation of due process to permit the dis

abilities which flow from pre-trial detention to infect the fact

finding, guilty-determining, punishment-setting processes of the

jailed defendant. Right to counsel, for example, one of the funda

mental rights of one accused of crime is of limited value if we

permit a host of subtle conditions to prejudice the working of the

adversary'system against one detained prior to trial. See Bitter

v. United States, supra.

The (potential) adverse effects of pre-trial incarceration are

many. See Foote, The Coming Constitutional Crisis in Bail, 113 U.

Pa. L. Rev. 959, 1125 (1965). An indigent defendant who lacks the

resources to finance a pre-vrial investigation by others and who

cannot, because incarcerated, conduct such investigation himself is

seriously disadvantaged. If the resources available to public

authorities for pre-trial investigation on behalf of indigent

defendants are inadequate, the defendant who has his liberty during

the pre-trial process is in a significantly advantageous position

relative to the accused who is incarcerated. Moreover, as recog

nized by the Attorney General's Committee on Poverty and Administra-

*tio'n of justice in many cases "it is only the accused who can locate

'10/ It should be noted that society pays dearly for punishing the

accused. Pre-trial detention cost the federal government $2

million in 1963. In New York City alone costs run to $10

million per year. Bail in the United States: 1964, 40-41 ..

(National Conference on Bail and Criminal Justice).

29

Petitionerand induce reluctant witnesses to come forward."

maintains strenuously that there are witnesses who may assist

in his defense who are unavailable to his counsel but who he

may be able to locate. Preparing a defense is especially dif-

ficult where, as here, ethnic or class differences isolate a

subcultural group and make it even more difficult for investigators

1 1 /to learn facts which might exonerate an accused.

Another kind of special prejudice which the incarcerated

accused is subject to is exhibition in a line-up which not only

results in possible new evidence being accumulated against him but

may result in police attempts to exploit the identification process.

The prosecution is able to obtain this advantage solely because of

the defendant's pre-trial detention status. If he had been enlarged

on bail police jurisdiction of him could not have been obtained

without his consent.

A number of less obvious consequences are significant.

Professor Foote summarizes them:

1. That the detained prisoner cannot hold a job is "the

principle explanation. . .which demonstrates that defendants fare

far worse in the sentencing process particularly in obtaining

probation than bailed defendants." -- - ~

2. The expectations of all those connected with the adminis

tration of criminal justice — police, jailers, prosecutors,

1V Crisis in Bail, at p. 1141, 1142.

- 30 -

defense counsel, judges, probation officers — prejudge the jail

case as a failure, and this prejudgment colors their actual dis-

position; for example, a probation officer assigned to write up a

jail case has a bias before he begins because of the defendant's

jail status. If this is true, then the statistics showing that

jailed defendants do in fact fare comparatively badly in the dis

position process may in part demonstrate nothing more than the

operation of self fulfilling prophecy.

3. The fact that the defendant himself shares this expectation

of failure tends, along with the fact that he will generally have

to find a new job, to reduce the chances of his successfully com

pleting a period of probation.

4. The quality of representation which a jail defendant

obtains is adversely affected by pre-trial detention because, in

stead of the defendant coming to his office, counsel must go to the

jail to see tne defendant, often under conditions unfavorable to

privacy and mutual dignity. The result is a reduction in the

frequency of pre-trial consultation below that which is desirable

ana which would take place where the defendant is on bail and able

« -- -r _- .to coma to the lawyer's office. The burden on the lawyer may also

intensify his resentment if he is already concerned about the low

%

work-to-fee ratio of much criminal representation.

5. The quality of the lawyer—client relationship is adversely

affected by pre-trial detention because the jailed defendant will

have less confidence in counsel and is more likely than a bailed

31

II. ■

defendant to feel that lie As getting inadequate representation.

v

Jail house consultation with the lawyer intensifies the defendant’s

j i • . '

disassobiaticn fi'oa counsel because he has had little or do responsi"j i

bility in the selection of the lawyer? confirms his opinion that

because he has no money he is receiving second class legal services?

induces that resentment which the poor feel because they are treated

as charity cases; and adds to his suspicion that the adversary

j - •system may in fact not be verv adversary when counsel is a public

• \ ~ >defender who is paid by the state and whose professional career is

the representation of jail house failures.

6. The defendant's prospects for rehabilitation turn in part

upon his outlook towards the fairness of the administration of

justice, which is adversely affected by his detention experience.

A defendant's attitudes are crystallized in prison, where the most

obvious lesson of the pre-trial period is that if you have money

you go out, i.e., that justice is for sale. Those familiar with

detention prisons are aware that this cynical attitude dominates

the value culture of the jail*

Empirical data suggests a very str'ong association between these

unfavorable effects* of pre-trial detention and higher sentences ar-d

fewer releases on probation. A host of authorities corroborate this

conclusion. See Crisis in Bail at SSO. See also Philadelphia Bail .

Study, 1052, table 1; New York Bail Study, 726-727. See also Freed

and Wald, Bail in United states, 1954. One study demonstrated that

of a group of New York prisoners in 1934, three tines as many

32

jailed defendants were sentenced to prison as those enlarged

12/on bail during the pre-trial period. Twice as many bailed

defendants as jailed defendants were not convicted; of those

convicted five times more jailed than bailed defendants did

not receive prison sentences. The author concluded these find

ings provide strong support for the notion that a causative

relationship exists between detention and unfavorable disposi

tion.

Given the prejudice suffered by detention prior to trial

and conviction, petitioner cannot be incarcerated solely by

reason of poverty. Such a system -- inefficacious at best

and easily perverted to permit the imposition of sanctions

against those who, though reasonably likely to return for trial,

are considered worthy of punishment by prosecutors or magistrates

or poor financial risks by bondsmen — cannot claim in this

case the support of any legitimate state interest sufficient

to offset the pains and prejudices which it needlessly imposes

on the poor.

12/ Rankin, The Effect of Pre-trial Detention, 39 N.Y.U.L.

Rev. 641 (1964)

33

IV

The Eighth Amendment As Incorporated

By The Fourteenth Grants A Broad

Right To Pre-trial Release Which May

Not Be Foreclosed Simply Because Of

Poverty

The eighth Amendment to the Constitution states as follows:

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor

excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and

unusual punishments inflicted.

It is petitioner's position that the Amendment as incorporated

by the Fourteenth implies a constitutional right to pre-trial

release, which cannot be burdened at this time in our history by

irrelevant considerations of wealth.

All discussion of the meaning of the Eighth Amendment bail

clause must begin with the ambiguity of its text, the many

difficulties of construction do not detract, however, from the

inevitable conclusion that the purpose of the Amendment was to

grant a broad right to pre-trial release.

It has been noted by the outstanding contemporary commentator

on the bail institution Professor Caleb Foote that there are three

possible interpretations of the language of the excessive bail

clause of the Eighth Amendment if it is considered as a text apart

13/

from its historical context.

13/ See Foote "The Coming Constitutional, Crisis in Bail" 113

U. of Pa. L. Rev. 959, 1125 (1965) hereinafter cited as

Crisis in Bail.

34

First, it night be urged that the Eighth Amendment weans bail%

cannot be demanded in an excessive sum in cases made bailable by

other provisions of law but that the clause of itself imports no

right to pre-trial release. While such a reading of the clause

is logically possible it presents the absurdity of a constitutional

provision being merely auxiliary to statutory lav;. This notion is

contrary to the whole concept of a Bill of Rights restricting a

legislature, for the right to bail could be denied by Congress and

• > -

the Amendment rendered meaningless for want of application. Such

a construction — under which the Eighth Amendment would be

nugatory in the absence of congressional or state legislation

establishing the scope of the right to bail — runs against tne

first principles of a written constitution, for "it cannot be

presumed that any clause in the Constitution is intended to be

without effect" Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 174 (1803).

Indeed, that construction would be inconsistent not only with the

remainder of the Bill of Rights but with the remainder of the

Eighth Amendment, for its prohibition against excessive fines

and cruel and unusual punishment have been incorporated in the

Fourteenth Amendment and applied to protect against legislative

actiono Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 6G0.

A second possible construction would be that hail cannot be

demanded in an excessive amount in cases in which a court sets

bail, but, in the absence of other statutory or constitutional

restrictions, the court retains the discretion to deny bail

35

1

altogether. Such a construction would also render the Eighth

Amendment excessive bail clause something unique and callously

futile in our constitutional system:

By making a clause say to the bail setting

court that it may not do indirectly v/hat it

i is however permitted to do directly deny

relief — the clause is reduced to the

! stature of little more than a pious platitude.

! i (Crisis in Bail at 970)

A great deal of historical data supports the conclusion that

the third possible construction — that the excessive bail clause

created a federal constitutional right to pre-trial release — is

far more likely than either of the two dryly logical alternatives

suggested above. In 1789 while the excessive bail clause was

being considered as one of the proposed amendments to the Con-

stitution, the first Congress passed Section 33 of the Judiciary

Act extending an absolute right to bail in all noncapital federal

criminal cases. The available materials contain "nothing to

indicate that anyone in Congress recognised the anomaly of

advancing the basic right governing pre-trial practice in the

form of a statute while enshrining the subsiduary protection

insuring fair implementation of that right in the Constitution

14/

itself." One is left to conclude that the right to bail v;as so

fundamental to the framers that they never questioned that the

Eighth Amendment had granted it. This conclusion is reinforced

14/ Crisis in Eail at 972.

- 36

by the passage in 1787 of the Northwest Ordinance which stated:

. . . all persons shall be bailable unless

for capital offenses where the proof shall

be evident or the presumption great; all

i fines shall be moderate; and no cruel or

j. unusual punishments shall be inflicted. . . .

(An Ordinance for the government of the

Territory of the United States, Northwest

of the River Ohio, July 13, 1787, Article ii).

Ho reason suggests itself why the inhabitants of the Northwest

Territory should have been given by their organic charter

greater rights in this regard than citizens of the United States

within its organic bounds.

The history of the language which became the Eighth Amendment

also stroports this conclusion. The- following excerpts from

ii/Cr5-sis in Bail describe the background of English history

against which the Eighth Amendment came to be drafted:

Recognition of the importance of bail in order to - -

avoid pre-trial imprisonment was a central theme

in the long struggle to implement the promise of

the famous 39th chapter of Magna Carta that "no

freeman shall be arrested, or detained in prison. . .

unless, . .by the lav; of the land." It is

significant that three of the most critical

(steps in this process *— the Petition of Right

I in 1628, the Habeas Corpus Act of 1S79, and

the Bill of Rights of 1689 -- grew out of

cases v;]jich alleged abusive denial of freedom

on bail pending trial.

Darnel's Case in 1627 involved five knights

who had been thrown in prison by Charles I and

who brought an action for habeas corpus at the

king's bench. The return of the prison warden

merely recited that Darnel "was and is committed

15/ Id. at 965-936 [notes omitted].

- 37

by the special command of his majesty, &c.n

Sergeant Bramston opened for his client by

stating that "it is his petition, that he

may be bailed from his imprisonment, . , for

it being before trial and conviction had by

law, it is but an accusation, and he that is

only accused ought by law to be let to bail*"

Counsel for another of the knights asked "how

can- the court adjudge upon this return, that

Sir John Corbet ought be kept in prison, and, „ .

that he is not bailable?" The Attorney

1 General argued that the. version of Magna

Carta chapter 39, enacted in 1354 upon which

the petitioners relied did not apply to pre

trial imprisonment, It was his position that

only imprisonment pursuant to "final prosecution"

must be "by due process of lav;"; the pre-trial

period "is not within the meaning of the

statute," When the judges proved their sub

servience to the King by denying release, the

case was taken up in Commons as soon as

parliament convened early the next year. In

the debates which ensued during the preparation

of the Petition of Right there was repeated

discussion ofDarnel *s case

e f fe c t ive ne s s

First of 1275

thus Coke stated that

must be known, else

the fact that, if the decision in

stood, it would impair the

of the Statute of Westminster the

which governed admission to bail;

"the cause of imprisonment

statute will be of littlethe

force. oU

It was against this background that the

Petition of Right was adopted and received from

] Charles I the grudging answer, "Soit droit fait

come il est desire par le petition," Reciting

the abu^e of cases like that of Darnel,, the

Petition prayed that "no freeman in any such

manner as is before mentioned, be imprisoned or

detained: and thereby brought the force of Magna

Carta to bear upon pre-tri'al imprisonment.

Not quite half a century later, on June 27,

1676, one Jenkes was arrested and imprisoned,

apparently for inciting to riot in making a

speech asking that Charles n be petitioned to

call a new parliament. The charge was one which

by statute required that Jenkes be admitted to

bail, but on the following August 13 he was

38

f

■,.i

still trying in vain to gat. anyone to sot and

take his bail, and ha was ultimately released

only by an informal process* Cases such as

Jenkes' in turn contributed to the enactment

of the great Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, which

recited that "many of the King's subjects have

been and hereafter may be long detained in

prison, in such cases where by law they are

bailable. . „ ." The act provided in great

detail for an habeas corpus procedure which

plugged the loopholes and even made the king's

bench judges subject to penalties for non-

compliance. • •

The Act of 1679 stopped the procedural

runaround to which Jenkes had been subject, but

by setting impossibly high bail the judges

erected another obstacle to thwart the purpose

of the law on pre-trial detention. When,

therefore, parliament drew up a Bill of Rights

which was accepted by William and Mary as they

assumed the throne, one of the abuses by which

the late King was alleged to have tried "to

subvert . . . the laws and liberties of the

kingdom" was that "excessive bail hath been

required of persons committed in criminal

cases, to elude the benefit of the laws made

for the liberty of the subjects," The remedy

which followed was the language with which we

are concerned: "That excessive bail ought not

to be required. . . . "

Two things stand out in this history. The

first is that relief against abusive pre-trial

imprisonment was one of those fundamental aspects

of liberty which was of most concern during the

formative era of English lav;. The evils which were

being confbatted were obvious; as'Jenkes said in

one of his futile petitions:

My Lord, I have been imprisoned

since the 28-th of June, to my great loss,

charge, and prejudice of my health. I

have hitherto been denied bail, Habeas

•Corpus and the Writ of Main-prize; which

I am informed, were never before denied

to any of his majesty’s subjects in the

like case. . . . 7 do not beg a discharge,

for I desire nothing more than to clear

my innocence by a public trial./

39

His friends added that without bail ,!he might lie

there all his life-time without trial, which no

subject ought to do*"

V7e should note, second, that as the English

protection against pre-trial detention evolved

it came to comprise three separate but essential

elements. The"first was the determination of

whether a given defendant had the right to

release on bail, answered by the Petition of

Right, by a long line of statutes which spelled

out which cases must and which must not be

bailed by justices of the peace or (in the

early period) by sheriffs, and by the dis

cretionary power of the judges of the king's

bench to bail any case not bailable by the

lower judiciary* Second was the simple,

effective habeas corpus procedure which was

developed to convert into reality rights

derived from legislation which could otherwise

be thwarted. Third was the protection against

judicial abuse provided by the excessive bail

clause of the Bill of Rights of 1639.

The protective structure thus stands like

a three-legged stool, but when the Americans

strengthened and converted their English

statutory legacy into constitutional dogma

they unaccountably left off one of the legs.

This is the heart of the federal constitional

problem. The principle of habeas corpus found

its way into Article

stitution, while thethe 1689 Bill of Rights was included in our

Eighth Amendment. But the underlying right to

the remedy of bail itselfwhich these enactments

supplemented and guaranteed, was omitted.

1, section 9 of the Con-

excessive bail languageS

or

It is probably not surprising that for

nearly ninety years after' parliament had

enacted the English Bill of Rights there appears

to have been no reference to excessive bail in

any American legislation. The charter-making

period of colonial history had been completed by

the end of the seventeenth century and in any

event the colonists, as British subjects, assumed

40

they were protected by the principles of such

basic English legislation as Magna Carta, the

Habeas Corpus-Act, and the Bill of. Rights. In

any event, the excessive bail provision of, the

1689 Bill of Rights was merely one segment of

the English history, and we have already noted

that the preamble of this clause makes it

abundantly clear that its only purpose was to

shore up the enforcement of preexisting rights

to bail. The relatively subsidiary importance

of the clause in English law is illustrated by

Blackstone's relegation of it to a single

sentence buried in the middle of a five-page

chapter on bail.

But in June of 1776, less than a month

before the proclamation of the Declaration of

Independence in Philadelphia, the Virginia

legislature enacted the famous Virginia

Declaration of Rights, and here for the first

time, as clause nine, appeared the language

taken from the English Bil3. of Rights: "That

excessive bail ought not to be required, nor

excessive fines imposed, nore cruel and unusual

punishments inflicted." With the substitution

of "shall not" for "ought not to be," this is

the wording of the eighth amendment. Aside

from the obvious, inference to be drawn from the

identity of language, the path from Williamsburg

in 1776 to the congress in 1789 can easily_be

traced. The Virginia Declaration exercised a

magnetic force, and its ninth section was

incorporated in the Revolutionary period con

stitutions of Maryland, Delaware, North Carolina, Georgia .and Massachusetts. It was

in Virginia, moreover, that one of the most

vigorous fights developed in the struggle

'over fatification of the Constitution. By the

time of the Virginia deoate the Consciuui-ion

had been ratified without qualification in six

states; three others, Massachusetts, South

Carolina and New Hampshire, had coupled rati

fication with strong recommendations for the

adoption of certain amendments as a bill of

rights. These did not, however, make any

reference to bail. This latter procedure

was adopted in Virginia, whose convention recom

mended a bill of rights closely following tne

41

language of their earlier Declaration of Rights,

including the excessive hail clause. The sub-mgsequent ratifications by Nov/ York, North

Carolina and Rhode Island included the same

recommendation, When Madison rose in the House

of Representatives a year later to propose the

amendments v/hich became the Bill of Rights he

took the excessive bail language exactly as it

had been recommended by the Virginia Convention

which in turn had taken it verbatim from the

3.776 Declaration,

The man who wrote both the Declaration of

Rights in 1776 and the amendments proposed to^

Congress by the Virginia ratification convention

in 1783 was George Mason, one of the unsung heroes

of the revolutionary era, As the evidence is

persuasive that the excessive bail language of

the Declaration was carried forward into the Bill

of Rights without further thought or analysis after

it left Mason's hands, his role is one of critical

importance in understanding the original objective

of these £ev; words.

There was little about Mason v/hich would have

foretold his creative genius in fashioning our

constitutional lav/. Although educated in the

library of a lawyer uncle v/hich included n

generous share of lav/ books and although he served

for many years as a lay justice for Fairfax

County, he hex! no technical training or experience

as v. lawyer. lie v/as preoccupied with raising nine

young children after the death of his v/ife and

with managing a 5,000 acre plantation just down

river from Mount Vernon v/ith 500 s3.aves who not

only produced and'shipped out tobacco and wheat

but also made the plantation almost entirely

self-sufficient in such matters as food, liquor,

lumber, clothing and shoes. His correspondence

was mostly about his immediate concerns: running

the plantation, requisitioning supplies and powder

for the militia, promoting the development of

western land, collecting his debts or getting his

debtors throv/n in jail, riding to hounds or hunting

deer in his private game preserve v/ith his

neighbor, George Washington, and protecting the

Potomac from marauding robbers or scavenging

British naval parties. Throughout his life he

shunned public office, and only the most compelling

- 42

circumstances could dislodge him from these

local, family and plantation responsibilities.

The Virginia Convention of June, 1776, was

such a circumstance, and it catapulted him

into the role of chief architect of fundamental

American liberties.

Two years before, in 1774, Mason had drafted

the Fairfax Resolves, a protest document whose

influence can be seen in the Declaration and

Resolves of the First Continental Congress later

that year. At that time, however, Mason's role

was not that of rebel but pS loyal British sub

ject, importuning and pleading in the great tra

dition which before had produced such monuments

as Magna Carta, the Petition of Right delivered

to Charles a and the English Bill of Rights of

1633. But when the 1775 Virginia convention met,

the die for revolution had been cast — - the

Declaration of Independence was only four weeks

away and the task was to form a new government

for the Commonwealth. Mason himself noted that

his draft Declaration of Rights was the first doc

ument of its kind in American history. Nor had it

any counterpart in England, whose great charters

of liberty were either statutes like the Habeas

Corpus Act with "no noble language, just down-to-

earth regulations. . ."or enactments like Magna ’

Carta and the Bill of Rights, in v/hich specific

concessions were obtained from the Crown. In

deed, the form of the English Bill of Rights bears

a striking resemblance to the colonial protest doc

uments of 1774, first spelling out grievances and

then reaching for solutions. Mason's outlook in

1776, however, was entirely prospective. There

was no certain form'of future government, no

body of existing law and precedent whose incor

poration could be assumed, and he described as

his objective the creation of a "hew government

upon a broad foundation” and the provision of

"the most effectual securities for the essential

rights of human nature, both in civil and

religious liberty." The philosophy of Locke and

Sidney, some of the finest creations of the 600

year, struggle for liberty in England, a strong

conviction of the importance, of man, and an

intense but practical idealism were some of the

ingredients that filtered through his mind into

the Declaration. It is difficult today, when

43

much of what las wrote has become trite with

familiarity, to appreciate the extent of

Mason's creative innovation, This is because

his selection and phrasing was borrowed by

Jefferson for the Declaration of independence,

because the Virginia Declaration became the

model for most subsequent state constitutions,

and because many of the clauses found their

way into the Bill of Rights,, But anyone who

puts himself into its historical context in

reading Mason's Declaration is likely to agree

with Jefferson's estimate of Mason as "a.man

of the first order of wisdom among those who

acted on the theatre of the revolution, of

expansive mine, profound judgment, cogent in

argument, learned in the lore of our former

constitution, and earnest for the republican

change on democratic principles,"

Why, then, in a document generally so well

adapted to its purpose, did Mason deal with the

problem of pre-trial detention in so incomplete

and ambiguous a fashion? In every other operative

clause of the Declaration, for example, habeas

corpus, jury trial, confrontation, venue, self

incrimination, general searches, the prohibition

against governmental action is clearly stated,

The defect in his treatment of bail seems most like3.y to have arisen from Mason's failure to