North Carolina Teachers Association v. Asheboro City Board of Education Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

February 28, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. North Carolina Teachers Association v. Asheboro City Board of Education Brief for Appellee, 1967. 36884dc0-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ac1a4928-7781-41ad-be76-64ba0e328341/north-carolina-teachers-association-v-asheboro-city-board-of-education-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

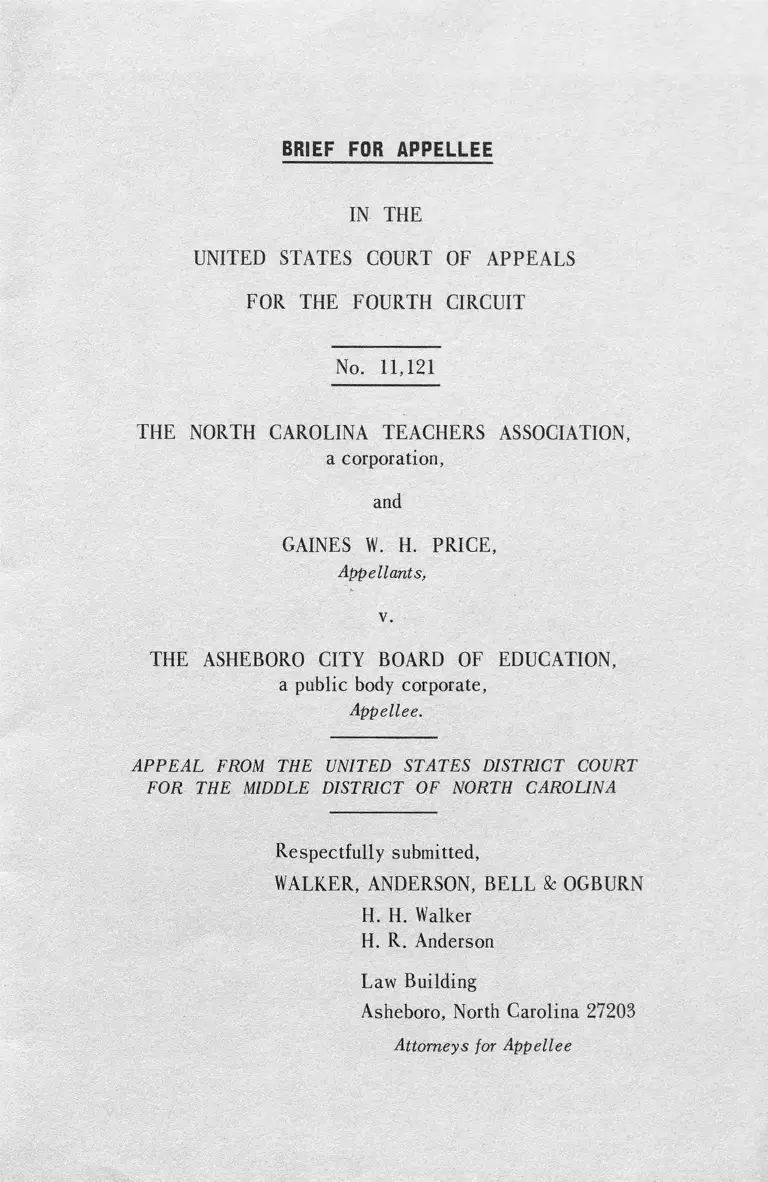

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 11,121

THE NORTH CAROLINA TEACHERS ASSOCIATION,

a corporation,

and

GAINES W. H. PRICE,

Appellants,

v.

THE ASHEBORO CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

a public body corporate,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Respectfully submitted,

WALKER, ANDERSON, BELL & OGBURN

H. H. Walker

H. R. Anderson

Law Building

Asheboro, North Carolina 27203

Attorneys for Appellee

INDEX

Page

Statement of E ase............................................................................. 1

Statement of F a c t s .......................................................................... 5

Issu e ................................................. 9

Arguement........................................................................................... 10

Certificate................ 17

Appendix............................................................................................. 19

TABLE OF CASES

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F.Supp.776, 777 (E.D.S.C. 1955)..................13

Brooks v. School District of City of Moberly, Missouri, 267 F.2d

733................................................................................................ 12

Buford, et al v. Morganton City Board of Education, 244 F. Supp.

437, (W.D.N.C. 1965)............................................................... 15

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education, 364 F.2d

189 (4 Cir. 1966).................................................................. 11,16

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, 360 F.2d 325

(4 Cir. 1966 ).................................................................. 14-15-16

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4 Cir. 1966).............................. 6

Louisiana, et al v. United States, 38 US 145, 154, 85 S. Ct. 817,

13 L.Ed. 2d 709, 715 (1965)................................................. 13

Morris v. Williams, 149 F.2d 703 (8 Cir. 1945).............................. 12

STATUTE:

North Carolina General Statutes § 115-58, 115-72...................Ap. 19

North Carolina General Statutes § 115-142...................................... 20

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 11,121

THE NORTH CAROLINA TEACHERS ASSOCIATION,

a corporation,

and

GAINES W. H. PRICE,

Appellants,

v.

THE ASHEBORO CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

a public body corporate,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal is from a final judgment (456a) entered on

the 31st day of October, 1966, ( -F . Supp.-) of the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North Caro-

Irna, Greensboro Division, said final judgment following

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Opinion in Case

No. C-102-G-65 dated October 19, 1966, (455a). The judg-

2

ment recited that plaintiffs (appellants) have not established

the right to any of the relief prayed for in the complaint or

amendments thereto, and the action was thereupon dismissed.

This action was originally instituted by The North Caro

lina Teachers Association in which it sought to have The

Asheboro City Board of Education enjoined from hiring, as

signing, and dismissing teachers on the basis of race and

color, and by order signed on February 11, 1966, the original

plaintiff was allowed to amend by praying that all teachers

found to be denied employment by virtue of any constitutional

rights having been violated by reinstated in the same or com

parable positions in the Asheboro School System. Motion for

preliminary injunction was denied on February 11, 1966. and

motion of the Asheboro City Board of Education to dismiss

was likewise denied on the same day. The cause came on for

hearing on May 3, 1966, and plaintiff introduced evidence con

sisting of exhibits and testimony. The defendant offered no

evidence.

Following the closing of the school which was then known

as Central High School and the conversion of this school into

Central School, several conferences were held with the teach

ers in the entire system (144a). Letters were sent to Negro

teachers at Central High School because of the closing of

the school, and this was due to the fact that there appeared

at that time to be uncertainty as to the availability of posi

tions for certain teachers.

On February 11, 1965, the defendant adopted a plan for

compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

(196a). Following conferences with the United States Office

of Education, there have been some revisions to this plan

3

(196a). The Board of Education of the City of Asheboro fur

ther directed all personnel connected with the school system,

as a part of its policy governing employment and assignment

of staff and professional personnel, that “ Employment and/

or assignment of staff members and professional personnel

shall be based henceforth on factors which do not include

race, color, or national origin and shall be on a non-discrimi-

natory basis. Factors to be considered will include training,

competence, experience, and other objective means of mak

ing evaluations.” This policy and directive was adopted in

June, 1965, (51a).

In the amended complaint plaintiff requested the Court

to order reinstated all teachers found by the Court to be den

ied employment in violation of their rights under the due pro

cess and equal protection clause of the Constitution.

The defendant denied that there has been any discrimina

tion as against any teachers, severally or individually, and

requested the Court to dismiss the action. The defendant

contended that the nine (9) Negro teachers who taught in the

defendant’ s school system during the school year 1964-65

were not offered additional employment only after these tea

chers were considered and compared with all other teachers

in the entire school system in comparable positions. At the

same time certain white teachers were released for cause and

others resigned after conferences.

Following the hearing on May 3 and May 4, 1966, Gaines

W. H. Price filed a motion to intervene or be added as a party

plaintiff in this cause and requesting that he be allowed to

adopt the pleadings in evidence of the original plaintiff. De

fendant filed a response to this motion to intervene on the

3rd day of July, 1966. Following this, a hearing on the motion

to intervene was held, and the parties hereto stipulated that

4

certain testimony would be admitted concerning Gaines W. H.

Price (430a).

On the 15th of September, 1966, the Court permitted Gain

es W. H. Price to intervene as a party plaintiff and to adopt

the pleadings of the original party plaintiff heretofore filed

in the matter. On October 19, 1966, the Court filed its Find

ings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Opinion and found that

the action did not in any way involve pupil assignment, but

raised the issue only of whether the defendant in its system

hires, assigns, and dismisses teachers on the basis of race

or color. No issue was involved concerning the discharge of

a teacher prior to expiration of his contract of employment

(439a). The Court further found (435a) that during the 1964-

65 school year the defendant operated a total of nine (9)

schools, consisting of one senior high school, two junior

high schools, five elementary schools, and one union school,

then known as Central High School. During the school year

1964- 65 twenty-four (24) Negro teachers were employed in

the school system of the defendant and were assigned to

Central High School, then a union school. In February, 1965,

the defendant took action effective for the 1965-66 school

term to reorganize its school system. This resulted in the

conversion of the all-Negro Central High School into an ele

mentary school, grades 1 through 6. The name was changed

to Central School and the prior teacher allotment of twenty-

four (24) was reduced to twelve. The teacher allotment for

the defendant's entire school system for the school year 1964

-65 was two hundred nine (209), and the allotment for the

1965- 66 school year was two hundred six (206). Prior to 1965

-66 Negro teachers were assigned to the Central High School

and white teachers were assigned to the other schools in the

system. Upon the reorganization of the system, commencing

with the school year 1965-66, the Asheboro High School ac

commodates all students in the entire system attending grades

5

10 through 12; Asheboro Junior High School accommodates

all students in the entire system attending grades 8 and 9;

and the Fayetteville Street School accommodates all students

in the entire system attending grade 7. Under this single as

signment policy, all students, Negro and white, in a given

grade, attend the same school from grades 7 through 12. Dur

ing the school year 1965-66, eleven (11) Negro teachers

taught as Central School, one (1) Negro teacher taught at

Asheboro High School, one (1) Negro teacher taught at Ashe

boro Junior High School and one (1) Negro teacher taught

part-time at the Balfour Elementary School.

The Court further found (438a) that resignations were

requested and received from four (4) white teachers who

taught in the defendant’ s school system during the 1964-65

school year, and, in addition, other white teachers resigned

after conferences. Not offered re-employment for the year

1965-66 were nine (9) Negro teachers, which number includes

the individual plaintiff.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

In February of 1965, pursuant to the requirements of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, the defendant adopted a plan of

compliance, and this plan was subsequently revised in part

following conferences with the United States Office of Edu

cation (196a). The schools of the Asheboro City School Sys

tem are approved and accredited by the North Carolina State

Department of Public Instruction and by the Southern Associ

ation of Colleges and Schools (195a). Prior to the adoption

of the plan for compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 there had never been an application for transfer

by a Negro student which was not approved in the entire

Asheboro City School System (196a). It is respectfully sub

mitted to the Court that there is no evidence at all in this

6

case that there has ever been any difficulty with a Negro

student getting in any school of his choice in the Asheboro

system.

As stated in the case of JOHNSON v. BRANCH, 364 F.2d

177 (4 Cir. 1966): “ The law of North Carolina is clear on the

procedure for hiring teachers. All contracts are for one year

only, renewable at the discretion of the school authorities.

A contract must be signed by the Principal as an indication

of his recommendation and then transmitted to the District

School Committee, whose business it is either to approve or

disapprove it in their discretion.” (N. C. G. S. Sec. 115-72).

There is no vested right to public employment.

The stipulations entered into by and between the parties

to this action on the 15th day of September, 1966, (430a)

certainly dispute the claim of plaintiffs that the teachers not

offered new contracts of employment were not compared by

the administration with all teachers in comparable positions.

The pertinent portion of the stipulation is as follows: “ Each

of the Negro teachers not offered new contracts of employ

ment was compared by the administration with all teachers in

comparable positions. For instance, Gaines W. H. Price was

compared to Joseph B. Fields, A. G. Harrington, A. B. Fair-

ley, and J. A. Hayworth; teacher Price had a bachelor’ s de

gree while teachers Fields, Harrington, Fairley, and Hay

worth all had master degrees. Teacher Price had a Class A.

Certificate in the music (science) area while teachers Fields,

Harrington, and Hayworth had Graduate Certificates in either

music or science, civics or chemistry and general science.

Teacher Price was rated by the administration as an aver-

7

age teacher while teacher Fields was rated superior, teacher

Harrington rated above average, teacher Fairley rated super

ior, and teacher Hayworth was rated above average. In addi

tion to the general qualifications, other qualifications were

listed in the record showing teacher Fields to have an ex

cellent record in training bands that won superior ratings in

competition for ten year.” The stipulations went on further

to provide that in addition to this portion of the testimony,

other relevant evidence received concerned with the applica

tion of standards and criteria as applied to all teachers,

should and will be considered by the Court in deciding this

case now pending (430a-431a). The Superintendent stated

(320a-352a) that as to each of the teachers not offered re

employment, they were compared with all other teachers in the

areas of certification. For instance, (321a) teacher Price was

not re-employed because the Superintendent stated that the

other band directors both had had preferential qualifications

as to academic background, performance and some other cata-

gories, and he compared this teacher with the other two band

directors. Teacher Kilgore, a Negro not offered re-employ

ment, accepted employment elsewhere earlier than May of

1965, but even so, he was compared with the teachers in the

entire system (331a) who were in comparable positions to

Jackie E. Kilgore. This was not a general broadside com

parison, but the teachers were named specifically. Teacher

Pearline Palmer was compared to six (6) other teachers in

the library and related fields in the entire Asheboro system.

Sarah I. Peterson, not offered employment for the year 1965-

66, was compared with all other persons in comparable posi

tions by name and individually (337a) (338a) (339a). Lewis

H. Newberry was compared (339a et seq.) and in addition

(340a), it was testified that this teacher had a very "annoy

ing habit” of presenting worthless checks, even to the school

in which he was employed on at least three occasions to the

school, and on occasions to other citizens of the community.

The answer to interrogatories by the Superintendent dated

March 5, 1966, (90a-95) shows that the written evaluation

of each teacher in the school system was commenced in the

year 1964-65 and approximately 200 sheets were attached to

this answer to interrogatories and introduced in evidence by

plaintiffs. Plaintiffs did not attach these sheets or make them

a part of their appendix. The Superintendent stated that the

criteria used have been developed from the literature of the

profession and out of the experience of the teaching, super

visory, and administrative personnel of the school system and

that all criteria do not carry equal weight (92a), and that at

least one (1) formal written evaluation and three (3) or more

non-written evaluations (93a) were made. And it is signifi

cant that the defendant contended in several instances (367a)

that the Negro teachers not employed for the 1965-66 year

were compared with the teachers already in the system as

well as the new teachers in the areas of their certification.

It seems that the main contention of the plaintiffs is based

on the letters of May 14, 1965, written and sent to the individ

ual plaintiff and several other Negro teachers at Central High

School. However, the letter stated that the applications of the

teachers to whom the letter was mailed would be kept on file

for consideration as vacancies arose. There is no evidence

that any white teacher received such a letter and there is

evidence that the white teachers for whom there had been

determined to be no vacancy had been notified previous to

the May 14 letter (438a). The record affirmatively discloses

that the Negro teachers’ applications would be kept on file

and that they would be considered for employment if a vacany

occurred (364a).

Several white teachers were requested to resign after con

ference were held. Their names appear on Page 352a, some

of these teachers having had several years’ experience in the

Asheboro City School System. As pointed out by the District

9

Court (450a-451a) the white teachers not offered re-employ

ment did not receive any letter and while not affirmatively

shown by the evidence, the clear inference is that the white

teachers were not given the considerations outlined in the

letter; that is, their applications to remain on file and auto

matic consideration for vacancies.

The District Court found that the decree in this case is

dictated by the answer to the issue of whether race was a

factor entering into the employment and placement of teachers.

The District Court found that race was not a motivating factor.

The Court further went on to say that the fact that the teach

ers at predominantly Negro schools are largely Negro and the

fact that the teachers at predominantly white schools are

themselves white violates no part of the Constitution (453a).

The Court found that the individual plaintiff was not denied

due process of law or equal protection of the law by the de

fendant and further found that no person among those alleged

in the complaint had been denied due process of law or equal

protection of the law by the defendant and that the request

of the plaintiffs for an injunction should be denied and motion

of the defendant to dismiss should be allowed and the Court

in fact did dismiss the action and denied request for injunc

tive relief.

ISSUE

Are the plaintiffs in a position to complain that they have

been denied due process or equal protection under the laws

when the same standards and criteria were applied to all

teachers, so long as the action of the Board was not unrea

sonable, arbitrary, or motivated by racial considerations?

10

ARGUMENT

THE DEFENDANT BOARD HAS THE RIGHT, AUTHOR

ITY, AND THE OBLIGATION, TO EXERCISE ITS SOUND

DISCRETION IN REGARD TO THE EMPLOYMENT OR RE

EMPLOYMENT OF TEACHERS IN THE ENTIRE SYSTEM,

AND SO LONG AS IT DID NOT ACT CAPRICIOUSLY, AR

BITRARILY, OR ABUSE ITS DISCRETION THERE WAS NO

DENIAL OF DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL PROTECTION OF

LAW, AND THE NEGRO TEACHERS ARE NOT ENTITLED

TO THE RELIEF SOUGHT IN THIS CASE.

The record clearly shows in this case that each Negro

teacher notified had been evaluated and compared, just as

each white teacher in the system had been evaluated and

compared, with all other teachers in the area of their certi

ficates and qualifications. This applied to the teachers re

tained in the system and new teachers employed (369a).

Following such evaluation and comparisons, white teachers

as well as Negro teachers were not offered a new contract

for the year 1965-66. All teachers’ qualifications were con

sidered to see who was more qualified to teach in the entire

school system. Evidence elicited from the Superintendent on

direct examination by plaintiff (277a) in referring to the pro

cedures and criteria used in evaluating teachers, indicates,

and there is no evidence to the contrary anywhere in this

record, that present procedures and criteria had been used

by the school system for at least 20 years, except written

evaluations by the principals have been required only one

year. This written evaluation had to do with the individual

teachers and did not include a group evaluation which had

been required of all principals in the school system for at

least twenty (20) years (277a). Following the beginning of

11

the use of the individual form reports, the group evaluations

were no longer required (278a). Again, the answer to inter

rogatories by the Superintendent shows that the present pro

cedures and criteria used in evaluating all teachers have been

used for the school system for at least twenty (20) years, and

in addition (88a), with the respect of such procedures used

in evaluating the teachers, observations were made by the

principals constantly; the supervisors - directly, two to six

times yearly, and indirectly, constantly; by the Superintendent

- directly, irregularly, and indirectly, constantly, and by the

State Department of Public Instruction - irregularly. Various

conference are held concerning the performance of teachers

(89a) (90a). The criteria used have been developed from the

literature of the profession and out of the experience of the

teaching, supervisory, and administrative personnel of the

school system (91a). The Superintendent, Assistant Super

intendent, the Director of Elementary Instruction, various

principals, teachers, and members of the Board of Education

are all involved in establishing the criteria used in evaluat

ing teachers (9 la-92 a). The principal, supervisor, and Super

intendent then use this criteria to make the evaluation of

teachers.

This case is most certainly factually distinguishable from

CHAMBERS v. HENDERSONVILLE CITY BOARD OF EDU

CATION, 364 F.2d 189, (4 Cir. 1966). In the CHAMBERS

case, litigation had brought about some pupil desegregation

on a freedom of choice basis. In the instant case there was

no litigation involved, nor is there any evidence that there

had been any threatened litigation either as to the pupils or

the teachers, In our instant case all teachers were put to

the same test. The Court held in the CHAMBERS case, sup

ra, at Page 192, that “ white teachers who met the minimum

standards and desired to retain their jobs were not required

to the same test. The Court held in the CHAMBERS case,

supra, at Page 192, that “ white teachers who met the minimum

12

standards and desired to retain their jobs were not required

to stand comparison with new applicants or with other teach

ers in the system. Consequently, the Negro teachers who de

sired to remain should not have been put to such a test.”

In the instant case, as in the case of BROOKS v. SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF CITY OF MOBERLY, MISSOURI, 267 F.2d

733, all of the facts disclose that the officials of the Ashe-

boro School System prior to the end of the school year did

in fact carefully and conscientiously compare the qualifi

cations of all the teachers, using previously established

uniform standards, even putting the qualifications in writing

for the year 1965-66. Just as in the BROOKS case, supra,

the procedure used in the Asheboro system resulted in the

failure to rehire both white and Negro teachers. This Court

in JOHNSON v. BRANCH, 364 F.2d 177, (4 Cir. 1966) recog

nized the right of the North Carolina schools concerning and

respecting teacher contracts and the right of renewal. It is

respectfully submitted that the evaluation records themselves

constituted a specific survey of each teacher in the entire

system. It is true that the District Court in the instant case

did cast upon the school authorities the burden of proof to

expunge itself of any taint or allegation that it trafficked in

racial consideration in teacher employment and assignment

(449a). The defendant respectfully contends that this has

been done in the instant case. It is clear that the District

Court was totally aware of the absolute necessity of treating

all teachers alike and having cast upon the school author

ities the burden of exonerating themselves of the imputation

of racial discrimination as raised by the complaint, the Dis

trict Court examined the circumstances in the case of each

Negro teacher who was not re-employed. This was not a

sweeping and general survey resulting in a general conclus

ion, but a very comprehensive and careful examination of

the reasons in each individual instance for not retaining the

Negro teachers. The BROOKS case, supra, citing the case

of MORRIS v. WILLIAMS, 149 F.2d 703 (8 Cir. 1945) held

13

that “ ### teaching is an art; and while skill in its practice

cannot be acquired without knowledge and experience, ex

cellence does not depend upon these two factors alone. The

processes of education involve leadership, and the success

of the teacher depends not alone upon college degrees and

length of service, but also upon aptitude and the ability to

excite interest and to arouse enthusiasm.***” The question

presented in the BROOKS case, supra, as it is in the instant

case, is as to whether or not the method used by the Board in

employing teachers for the school year 1965-66 was fair and

objective to all involved.

The District Court’ s findings (450a) set forth that: “ As

stated in the Court's Findings of Fact, the displaced Negro

teachers were not treated as new applicants, considered only

for vacancies existing in the system, but were considered

for positions for which they were qualified and compared

with white and Negro teachers who had during the preceding

year been the occupants of those positions and signified a

desire to be re-employed.” The District Court further found

(452a-453a) that “ it is recognized that the Court has not mere

ly the power but the duty to render a decree which will, so far

as possible, eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past

as well as bar discrimination in the future. LOUISIANA, ET

AL v. UNITED STATES, 38 US 145, 154, 85 S. Ct. 817, 13

L.Ed. 2d 709, 715 (1965). Nevertheless the decree in this

case is dictated by the answer to the issue of whether race

was a factor entering into the employment, and placement

of teachers. The Court finds that race was not a motivating

factor. The fact that the teachers at predominantly Negro

schools are largely Negro and the fact that most teachers at

predominantly white schools are themselves white violates

no part of the Constitution.” Citing BRIGGS v. ELLIOTT,

132 F.Supp. 776, 777 (E.D.S.C. 1955).

The testimony in this case, consisting of rather lengthy

depositions, interrogatories, and answers to interrogatories,

14

and the testimony of the Superintendent, shows in great de

tail, relating to the individual teachers, that effective stan

dards and criteria and procedures have been equally applied

to all teachers of all races in the Asheboro school system.

The pattern of the evaluation of each teacher is demonst

rated in the answers to the interrogatories of the Superin

tendent dated March 5, 1966, and also in the Superintendent’ s

deposition of September 21, 1965. The Superintendent stated

(130a) in response to the question to what factors did he

consider in determining the competency of a teacher that:

’ ‘The normal, of course, are things you have asked about or

certainly you have mentioned. You have mentioned degrees;

you have mentioned experience. But of greatest importance,

as far as we are concerned, is performance in the classroom,

classroom performance.

“ Now in addition to that, professional attitude; ability

to accept responsibility and carry out obligations of a teach

er; I think certainly we would consider initiative.” Mr.

Teachey, the Superintendent, stated (131a) following the

question: “ I think you stopped with initiative.” A. “ Accept

ance of authority; loyalty - loyalty, of course to the administ

ration and the school system. And I jotted a new one down a

few days ago, which I came across in some of the readings on

the qualifications of a teacher. It had to do with - This per

son pointed out that the good teacher is one who can excite

pupils, who can create enthusiasm among them and this kind

of thing. These are subjective.” In response to a question

(131a) as to whether or not it would be very difficult for the

Superintendent to evaluate every teacher in the school system

according to these criteria, the Superintendent replied that

it would be necessary to depend upon other people.

As to the case of FRANKLIN v. COUNTY SCHOOL

BOARD OF GILES COUNTY, 360 F.2d 325 (4 Cir. 1966), it

15

is respectfully submitted that the FRANKLIN case was de

termined in this Court only after there had been a judicial

determination by the District Court of discrimination because

of race. Further, the FRANKLIN case was determined in this

Court on the question which related to whether or not the

District Court had offered the proper and equitable relief for

teachers after a Federal Court had in fact found that the

school board had discriminated against the teachers in res

pect to employment because of race. Thus, the opinion of

the Circuit Court in the FRANKLIN case related to the method

for affording relief and the extent of such relief after this

determination had been made. And in the FRANKLIN case,

this Court did not hold that the individual plaintiffs were

automatically entitled to re-employment but held only that

the plaintiffs were entitled to re-employment in any vacancy

which they may be qualified by cerificate or experience.

Appellee respectfully submits that the language of the

BROOKS case, supra, as quoted in the case of BUFORD, ET

AL v. MORGANTON CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION, 244 F.

Supp. 437, (W.D.N.C. 1965) is particularly applicable to the

case now being heard: “ The record discloses that experts

in the field of education are not in agreement as to the best

methods of evaluating teachers. Possibly, better methods

might be available for evaluating teacher qualifications. The

board has a wide discretion in performing its duties including

those relating to the employment of teachers. If the board

acted honestly and fairly in the exercise of its discretionary

powers, the plaintiffs are in no position to complain, at least

so long as the action of the board is not unreasonable, arbitra

ry, or motivated by racial consideration.”

Thus, this appellee respectfully contends that all the

16

evidence points unerringly to the fact that the defendant

school board has exercised its discretion in the best interest

of the entire school system and the pupils, as well as of all

teachers involved. There is no evidence that it has failed in

the burden put upon it of complying with constitutional re

quirements as well as the requirements that it act honestly

and fairly in the exercise of its discretionary powers.

There is no question at all that consideration of race or

color in the employment, assignment, and retention of teach

ers is clearly forbidden. CHAMBERS v. HENDERSONVILLE

CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION, supra, FRANKLIN v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF GILES COUNTY, supra,

BRADLEY v. SCHOOL BOARD OF CITY OF RICHMOND,

supra. This appellee respectfully submits to the Court that

there is no evidence that race or color entered into the em

ployment, assignment or retention of teachers. Appellee

further respectfully submits that it has a fully integrated

system of education, and that this is borne out by the table

contained in the Findings ofFact by the District Judge (437a);

that there was at the time of the institution of this suit one

Negro teacher teaching in the completely integrated Asheboro

High School, one in the completely integrated Asheboro Junior

High School, one in the Balfour Elementary School, and in

addition that there was a white principal and one white teach

er assigned to Central. Appellee respectfully contends that

the same standards and criteria did apply and now apply to

all teachers and applicants and respectfully submits that the

action of the District Court should be affirmed in all respects.

Respectfully submitted,

WALKER, ANDERSON, BELL & OGBURN

H. H. Walker

Law Building H. R. Anderson

Asheboro, North Carolina 27203

Attorneys for Appellee

17

CERTIFICATE

Four copies of this Brief were mailed (first class) to Mr.

J. Levonne Chambers, 405-1/2 East Trade Street, Charlotte,

North Carolina 28202; Mr. Conrad 0. Pearson, 203-1/2 East

Chapel Hill Street, Durham, North Carolina 27702; Mr. Sam-

mie Chess, Jr., 622 East Washington Drive, High Point, North

Carolina, and Messrs. Jack Greenberg and James M. Nabrit,

III, 10 Columbus Circle, New York, New York, 10019, Counsel

for the Appellants, on February 28, 1967, the same day on

which this Brief was filed with the Clerk of the United States

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, Richmond, Virginia.

Hal H. Walker

APPENDIX

THE NORTH CAROLINA STATUTES INVOLVED

The text of the North Carolina Statutes involved is as

follows:

GENERAL STATUTES OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPT

ER 115, SECTION 58 DUTIES WITH RESPECT TO E-

LECTION OF PRINCIPALS, TEACHERS AND OTHER

PERSONNEL.

It shall be the duty of the county superintendent to approve,

in his discretion, the election of all teachers and personnel

by the serveral school sommittees of the administrative unit.

He shall then present the names of all principals, teachers

and other school personnel to the county board of education

for approval or disapproval, and he shall record in the minutes

the action of the board in this matter. Provided, that in county

administrative units which elect to operate as one school

district without a school committee it shall be the duty of the

county superintendent to recommend and the board of edu

cation to elect all principals, teachers, and other school per

sonnel in the county administrative unit.

It shall be the duty of the city superintendent to record in

the minutes the action of the city board of education in the

election of all principals, teachers and other school personnel

elected upon the recommendation of the superintendent.

GENERAL STATUTES OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPT

ER 115, SECTION 72 HOW TO EMPLOY PRINCIPALS,

TEACHERS, JANITORS AND MAIDS. The district com

mittee, upon the recommendation of the county superintendent

of schools, shall elect the principals for the schools of the

district, subject to the approval of the county board of edu

cation. The principal of each school shall nominate and the

district committee shall elect teachers for all the schools of

20

the district, subject to the approval of the county superin

tendent of schools and the county board of education. Like

wise, upon the recommendation of the principal of each

school of the district, the district committee shall appoint

janitors and maids for the schools of the district, subject to

the approval of the county superintendent of schools and the

county board of education. No election of a principal or teach

er, or appointment of a janitor or maid, shall be deemed valid

until such election or appointment has been approved by the

county superintendent and the county board of education. No

teacher under eighteen year s of age may be employed, and the

election of all teachers and principals and the appointment

of all janitors and maids shall be done at regular or called

meetings of the committee.

In the event the district committee and the county super

intendent are unable to agree upon the nomination and elec

tion of a principal or the principal and the district committee

are unable to agree upon the nomination and election of teach

ers or appointment of janitors or maids, the county board of

education shall select the principal and teachers and appoint

janitors and maids, which selection and appointment shall

be final.

The distribution of the teachers and janitors among the

several schools of the district shall be subject to the ap

proval of the county board of education.

GENERAL STATUTES OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPT

ER 115, SECTION 142 CONTRACTS OF PRINCIPALS

AND TEACHERS TERMINATED AT THE END OF 1954-

1955 TERM; EMPLOYMENT THEREAFTER, (a) The con

tracts of all principals and teachers now employed in the

public schools of North Carolina are hereby terminated as

of the end of the school term 1954-1955. County and city

superintendents shall give each principal and teacher notice

21

by mail of the termination of his contract, but the failure to

give such notice shall not have the effect of continuing in

force of the contract of any principal or teacher beyond the

end of the 1954-1955 school term.

(b) Any teacher or principal desiring election as teacher

or principal in a particular administrative unit shall file his

or her application in writing with the county or city superin

tendent of such unit. The application shall state the name

and number of the certificate held, when the certificate ex

pires, experience in teaching, if any, and the administrative

unit in which the applicant last taught. It shall be the duty

of all county and city boards of education to cause written

contracts on forms to be furnished by the State Superintendent

of Public Instruction to be executed by all teachers and prin

cipals before any salary vouchers shall be paid. The con

tracts of teachers and principals shall be made for the next

succeeding school year or for the unexpired part of a cur

rent school year. No county or city board of education shall

enter into a contract for the employment of more teachers, in

cluding vocational teachers, than are allotted to that parti

cular administrative unit by the State Board of Education un

less provision has been made for the payment of the salaries

of such teachers from local funds. All contracts shall be sub

ject to the condition that when the position for which any

principal or teacher is employed is terminated the contract

is likewise terminated.