Richmond Virginia School Board v. Virginia Board of Education Reply Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1972

26 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Richmond Virginia School Board v. Virginia Board of Education Reply Brief for Petitioners, 1972. 0b72e65b-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ac3295de-a9a7-4708-8ee6-476e7bd93e04/richmond-virginia-school-board-v-virginia-board-of-education-reply-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

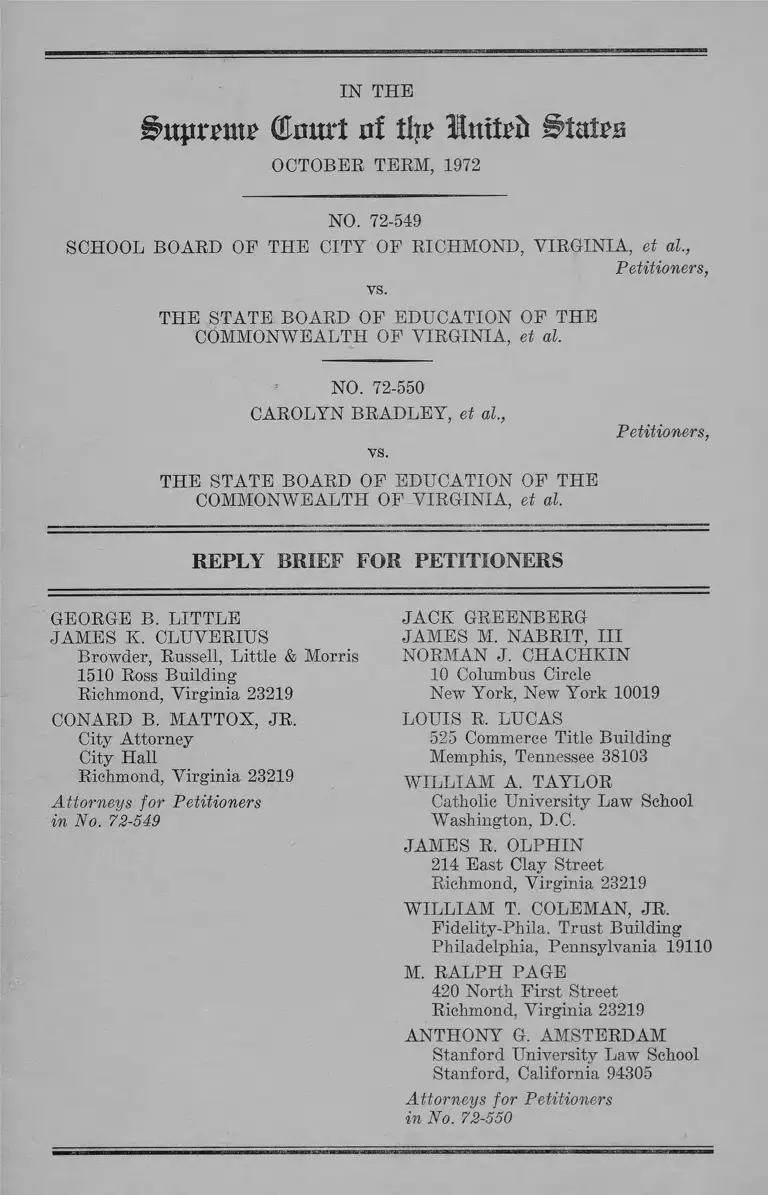

IN THE

l&uproui? (Limrt of to

OCTOBER TERM, 1972

NO. 72-549

SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF RICHMOND, VIRGINIA, et al.,

Petitioners,

THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, et al.

NO. 72-550

CAROLYN BRADLEY, et al,

vs.

Petitioners,

THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, et al.

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

GEORGE B. LITTLE

JAMES K. CLUVERIUS

Browder, Russell, Little & Morris

1510 Ross Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

CONARD B. MATTOX, JR.

City Attorney

City Hall

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Petitioners

in No. 72-549

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

LOUIS R. LUCAS

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

WILLIAM A. TAYLOR

Catholic University Law School

Washington, D.C.

JAMES R. OLPHIN

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

WILLIAM T. COLEMAN, JR.

Fidelity-Phila. Trust Building

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19110

M. RALPH PAGE

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioners

in No. 72-550

I N D E X

Introduction ......... ..... .............................. ...... ......... ........ . 1

A. The Issue of Constitutional Violation ....... 2

B. The Issue of Remedy ............................ ............. 13

Co n c l u sio n ................................ ..... ....................... ............. 21

T able oe A uthorities

Cases:

Adams v. Richardson, Civ. No. 3095-70 (D.D.C., No

vember 16, 1972, February 16, 1973) .......... ................ lOn

Brewer v. School Board of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th

Cir. 1968) .................. , ............. ...................................... 6n

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954);

349 U.S. 294 (1955) ............................................. 13n, 17,18

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile,

402 U.S. 33 (1971) ........ ............................................... 6n

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ................. .............................10,11,12

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 417 F.2d 801

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969) ........... 12n

James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137 (1971) ...................... 5n

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education,

436 F.2d 856 (6th Cir. 1970), 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972) ...................... ..... 12n

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) ....... ..... lOn

PAGE

11

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 446 F.2d 911

(5th Cir. 1971) .............................................................. l ln

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 41 U.S.L.W. 4467 (U.S., April

2, 1973) .............................. ........... ................................... 16n

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 TJ.S. 443 (1968) ....11,12

San Antonio School District v. Rodriguez, 41 TT.S.L.W.

4407 (U.S., March 21, 1973) ...................................... 16,18

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) ....... ...................... lOn

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 TJ.S. 1 (1971) ..................................................5n, 11,12

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

453 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972) .................................... 12n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

431 F.2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970), rev’d 402 TJ.S. 1 (1971) 9n

United States v. Aluminum Company of America, 148

F.2d 416 (2d Cir. 1945) ........ 8n

United States v. Board of School Commissioners of

Indianapolis, No. 72-1031 (7th Cir., February 1,

1973), aff’g 332 F. Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971) ____ 8n

United States v. W.T. Grant Co., 345 U.S. 729 (1953) 8n

Wright v. Board of Public Instruction of Alachua

County, 445 F.2d 1397 (5th Cir. 1971) ..................... lln

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) ....................................................................... 16n

Other Authorities:

Department of HEW, The Effectiveness of Compen

satory Education, Summary and Review of the Evi

dence (1972) ..................................................................... 19

PAGE

Ill

Jencks, C., et al., Inequality (1972) ................. ............. 18n

Mosteller, F. and Moynihan, D. (Eds.), On Equality of

Educational Opportunity (1972) ......................... ...... 18n

Office of Education, Equality of Educational Opportu

nity [The Coleman Report] (1966) ______________ 18n

“Perspectives in Inequality,” 43 Harvard Educational

Review (No. 1, February, 1973) ................................ 19n

U.S. Civil Rights Commission, The Diminishing Bar

rier; A Report on School Desegregation in Nine

Communities (1972) ............ ............... ....... .......... ....... I9n

U.S. Civil Rights Commission, Five Communities:

Their Search for Equal Education (1972) ............... 19n

U.S. Civil Rights Commission, Racial Isolation in the

Public Schools (1967) ............... ................................... 18n

Washington Star-News, February 13, 1973 .............. . 20n

*

PAGE

I n t h e

(tart of fir? lotted Us

October T eem , 1972

No. 72-549

S chool B oaed oe th e C ity of R ichm ond , V irginia , et al.,

VS.

Petitioners,

T h e S tate B oaed of E ducation of th e Com m onw ealth

of V irginia , et al.

No. 72-550

Carolyn B radley, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

T h e S tate B oaed of E ducation of the Com m onw ealth

of V irginia , et al.

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Introduction

The Briefs of the petitioners and respondents and the

Memorandum of the United States1 exhibit marked dis-

1 Throughout this Reply Brief, in addition to the abbrevia

tions in citations previously employed by the parties (see the first

footnote in each of the Briefs of the parties), the opening briefs

and the government’s memorandum will be identified as follows:

2

agreement in the framing of the decisive issues of this

case. They are, however, in agreement upon a number

of points. We devote this Reply Brief to a canvass of

the agreements and disagreements, in the hope that, by

focusing the controversy between the parties, we may

facilitate the Court’s resolution of it.

Petitioners and the United States are in substantial

agreement as to the precise issue involved: whether the

relief decreed constituted an abuse of the remedial powers

of the District Court. (See U.S. Br. 2, 4.) However, both the

respondents’ characterization of the issue as one of “viola

tion” and the manner in which they (and the United States)

analyze the District Court’s exercise of remedial discre

tion, create unwarranted confusion. The predicate of re

spondents’ and the government’s arguments—namely, that

all vestiges of discrimination had been eliminated and that

the Richmond, Henrico and Chesterfield school systems

were “unitary” when these proceedings were brought—is

demonstrably false on this record.

A. The Issue of Constitutional Violation

1. Respondents construct the major part of their argu

ment upon the proposition that “before the federal ju

diciary can intervene in local school affairs the existence

of a constitutional violation must be established by way

of predicate for its action.” (St. Br. 50.) Petitioners

entirely agree. (See PL Br. 62-66; RSB Br. 91.) The

disagreement between the parties concerns not the need

for, but rather the identity of, the relevant constitutional

violation in this case. (See PI. Br. 57; RSB Br. 76-77.)

Brief for plaintiffs (Petitioners in No. 72-550) as “PL Br. ------

Brief for the Richmond School Board (Petitioners in No. 72-549)

as “RSB Br. ------ ” ; Brief for the state and county defendants

(Respondents in both cases) as “ St. Br. ------ and the govern

ment’s memorandum as “U.S. Br. ------ .”

3

2. Petitioners and the District Court see the constitu

tional violation in relatively simple terms that respon

dents’ brief strains to overlook. The violation is that

the public schools of the Commonwealth of Virginia within

the City of Richmond (as well as in the Counties of Chester

field and Henrico) were racially segregated by law and

by the purposefully segregatory acts of state and local

officials, before 1954, in 1954, and for almost two decades

thereafter. (See PI. Br. 11-16, 64-66; RSB Br. 30-47, 67-70,

86-91.) Respondents’ adamant refusal to talk about this

long-continued, uncontestable de jure segregation does not

make it go away. Respondents’ silence on the score does

not make it any less a constitutional violation, or the

constitutional violation that underlies this protracted liti

gation. Hence, the only question confronting the District

Court was how this enduring denial of fundamental con

stitutional rights could be effectively vindicated. This

search for an effective remedy provides the lens through

which all other aspects of this case must be viewed.

3. Much of the respondents’ brief consists of an attempt

to obfuscate this constitutional violation by the enumera

tion and refutation of a succession of other possible the

ories of “ constitutional violation.” (St. Br. 57-87.) Inas

much as the enumerated theories are neither petitioners’2

nor the District Court’s, their refutation by respondents

fails to join issues of any consequence. We agree with a

great deal of what is said in these pages of respondents’

brief, but not with its relevance to this case. The petitioners

2 Respondents argue, based on evidence introduced to demon

strate the effectiveness and feasibility of a desegregation plan

which crossed school division boundary lines—the only desegrega

tion plan of this nature put before the District Court—not that

the remedy is ineffective or impracticable, but that this evidence

was elicited by the petitioners and employed by the District Court

to establish constitutional violations.

4

have never maintained that any constitutional violation

flows from the absence of a “viable racial mix” (St, Br.

58-61) ;3 or from the mere fact that there are concentra

tions of blacks in Richmond and whites in Henrico and

Chesterfield (St. Br. 61-72) ;4 or from the mere proximity

3 We have never argued that the Constitution requires the assign

ment of any fixed or specific percentages of black and white chil

dren to a school or schools (see PL Br. 58-59; RSB Br. 76-77), and

the District Court neither found nor ordered any such thing (see

PI. Br., App. A, la-5a; RSB Br. 50-51). Respondents here pursue

their tactic, largely successful in the Court of Appeals (see PI. Br.

50-51; RSB Br. 51-52), of confusing the reasons for the Richmond

School Board’s proposal of a particular form of inter-division de

segregation plan (which included, quite properly, educational as

well as constitutional considerations, see St. Br. 18-32) with the

District Court’s distinct reasons for concluding that some form of

inter-division desegregation plan was necessary (which were, with

equal propriety, entirely constitutional reasons). Respondents cor

rectly note that the District Court quoted testimony of Dr. Pet

tigrew and other educational experts concerning a “viable racial

mix” or enrollment proportion likely to remain stable (St. Br. 30-

31). They ignore (1) that these quotations occur in the extensive

“additional findings of fact as supplemental to [the District

Court’s] . . . general findings of fact” (338 F. Supp., at 116-230,

Pet. A. 185-545), in which virtually all of the evidence in this

voluminous record is recalled and appraised, rather than in the

portion of the court’s opinion describing the factual and legal bases

of its constitutional ruling (338 F. Supp., at 79-116, Pet. A. 185-

263) ; (2) that the District Court was necessarily concerned with

the educational soundness of the Richmond School Board’s plan,

in addition to (not as a prerequisite of, see note 2 supra) its satis

faction of constitutional objectives (e.g., 338 F. Supp., at 115, Pet.

A. 262-63) ; and (3) that the District Court expressly held:

While the viable racial mix contemplated by the plan is ed

ucationally sound and would indeed result in a unitary sys

tem, variations from the suggested viable mix may be un

avoidable. All parties are admonished that it is not the

intention of the Court to require a particular degree of racial

balance or mixing. (338 F. Supp., at 230, Pet. A. 519-20).

4 Petitioners need not claim, on this record, that “ [Concentra

tions of blacks in cities and whites in suburbs . . . of itself . . .

[constitutes] a constitutional violation” (St. Br. 61), or that the

mere “proximity of majority-black to majority-ivhite schools . . .

[affords] a constitutional violation” (St. Br. 85). These conten

tions continue to be “ as much beside the point in Richmond, Yir-

of majority-black schools to majority-white schools (St. Br.

85-86) ;4 or from the strong community of interest between

ginia as it would have been beside the point in Swann to consider

whether, without more, a State’s use of the neighborhood school

system violates the Constitution as applied to neighborhoods of

differing racial concentration” (PL Br. 58; see id., 57-61, 73-77).

The close proximity of identifiably “black” and “white” schools

on either side of the Richmond City boundary lines (PI. Br. 8-10,

67, 86-87; RSB Br. 29-30), and the increasing concentration of

blacks in the center-city ghetto of Richmond (PI. Br. 30-35, 95-97,

App. F, l f -4 f ; RSB Br. 22-27, 68-70) were factors that added

enormously to the difficulty of desegregating the Richmond area

schools, and they were therefore properly considered by the District

Court in its efforts to arrive at an effective desegregation plan. So,

too, the District Court properly considered the prospect that a

Richmond-only desegregation plan would hasten the conversion of

the City into an all-black ghetto. (See PI. Br. 30-33, 67-68, 96;

RSB Br. 69-70.)

But these factors are not—and neither petitioners nor the Dis

trict Court have ever asserted that they were—independent, isolated

violations of the Constitution which alone justify the relief decreed.

For this reason, respondents’ invocation of James v. Valtierra, 402

U.S. 137 (1971) (St. Br. 69) as the response to extensive evidence

of racial discrimination in housing in the Richmond area (see PI.

Br. 33-35; RSB Br. 38-44, 67-69) is wide of the mark. In the first

place, it is not correct, as respondents imply, that the exclusion of

blacks from housing in the counties is entirely a matter of the un

availability of low-cost housing. For example, the federally as

sisted, moderate rental multi-family housing which is located in

the counties is virtually all-white (PX 129, 130). The District

Court also could properly infer from the unrebuttted testimony of

black witnesses (A. 461-67; 21 R. 42-49), the long-maintained

racially discriminatory real estate advertising policies of Richmond

newspapers (PX 42) and other evidence of pervasive racial dis

crimination (see generally, PL Br. 33-35) that Dr. Taeuber was

correct in his testimony (A. 632) that the highly segregated nature

of the greater Richmond community was not attributable solely to

the effect of economics. And unlike respondents’ assumptions that

restrictive covenants ceased to affect housing patterns after 1950

(St. Br. 67), the District Court considered both expert testimony

to the contrary (A. 736-39) and statements to the contrary by the

President of the United States and the Assistant Attorney General

(PX 90, 126). Thus housing discrimination—like the other forms

of overt racial discrimination which this record establishes are

pervasive in the Richmond area—could properly be considered by

the District Court in projecting that a school desegregation plan

6

Richmond, Henrico and Chesterfield (St. Br. 71-72) ;5 or

from the failure of the respondents to offer an alternative

plan of inter-divisional desegregation (St. Br. 84) ,6 Largely

limited to Richmond City would spawn exclusionary practices de

signed to keep blacks out of the counties. (See PI. Br. 96-97.) But,

in any event, the inability of blacks to find housing in the counties,

whether it results from racial discrimination or from economic dis

advantages (see PI. Br. 91-93 n. 158), was an appropriate con

sideration for the District Court in determining the. likely “ effec

tiveness” {Davis, 402 U.S. at 37) of a Richmond-only plan to deseg

regate the area’s schools. (See PI. Br. 86-98; RSB Br. 70-72.)

Cf. Brewer v. School Board of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968).

6 Petitioners made no such argument, either below or in our orig

inal briefs. Significantly, respondents do not direct the Court to

any portions of the District Court’s opinion (see St. Br. 71-72),

for there is nothing in that opinion which even remotely suggests

“ that a single community of interest in Richmond and the adjacent

counties gives rise to a constitutional requirement” of an inter

division plan (St. Br. 71). Rather, the District Court quite cor

rectly took account of the interdependence throughout the area in

gauging the degree to which schools remained racially identifiable

at the time of its decree and in weighing the feasibility of an inter

division plan. (See PI. Br. 92-95; RSB Br. 62-64.)

6 Petitioners’ briefs noted that the Richmond Board’s plan was

the only inter-division plan put before the District Court, not

withstanding ample opportunity was afforded to all parties to sub

mit alternative plans. (PI. Br. 46, 61-62, App. B, lb-3b; RSB

Br. 47-48, 70-71.) Because a district court’s approval of the only

constitutionally adequate plan proposed by any party manifestly

does not constitute an adoption by the court of that party’s non

constitutional reasons for preferring the plan to other possibly con

stitutional alternatives, we had hoped that the respondents might

appreciate the irresponsibility of confusing, on this record, (i) the

Richmond School Board’s educational objectives in selecting the

plan, with the District Court’s constitutional objectives in approv

ing it (see PL Br., App. A, 4a), or (ii) the consolidation form

of plan chosen by the school board for reasons of practicality (A.

240) with “any general assertion [by the District Court] of a

sweeping power . . . to ‘compel one of the States of the Union to

restructure its internal government’ ” (PI. Br. 61; see id., App. B,

lb-3b). Respondents nevertheless persist in promoting both con

fusions—the first of which is the basis of their “viable racial mix”

argument discussed in note 3 supra, and the second of which ap

pears in their extravagant formulation of the political question-

7

uncontradicted evidence of these facts was properly con

sidered by the District Conrt in determining that Richmond-

only desegregation plans would not be effective and that

the plan proffered by the Richmond School Board was the

only alternative before the court holding out any promise

of providing effective relief. But this evidence was not

taken by the District Court to establish new and indepen

dent constitutional violations.

We agree in part and disagree in part with the last

two propositions stated in respondents’ needless and fruit

less quest for a “ constitutional violation.” It is true that

the “ failure” of “ the State Board [of Education] . . . to

consolidate the three systems . . . did not violate the Con

stitution,” standing alone (St. Br. 79; see id., 79-84). But

the cooperation of Virginia’s several educational authori

ties in numerous segregatory schemes that ignored local

school division lines, while standing solidly upon those

lines as bulwarks against desegregation, was, of course,

one of the many means by which the Commonwealth his

torically promoted separation of the races in the public

schools and resisted its termination. (See PI. Br. 84-86;

RSB Br. 64-66.) “History does not afford a constitutional

violation” (St. Br. 73; see id., 73-78) if viewed with the

supercilious anachronism that mentions Virginia’s “mem

bership in the Confederacy during the Civil War” (St. Br.

73) and glosses disingenuously over everything that fol

lowed. But the recent history of Virginia’s unremitting

hostility and resistance to school desegregation (PI. Br.

11-16, 18-22; RSB Br. 32-44) is plainly relevant both to

the racial identifiability of disproportionately black schools

today and to the choice of means necessary to disestablish

Tenth Amendment argument advanced at St. Br. 103-04—while

they erect and instantly demolish “ failure . . . to offer an alternative

plan” as an independent claim of constitutional violation. The

claim is none of ours.

8

them. (See PL Br. 86-97; RSB Br. 77-91). To assert the

contrary simply insults the intelligence of the Court as well

as the sensibilities of a People brutalized by having to

witness the entire governmental machinery and public life

of a State committed overtly to resisting the constitutional

command that they be treated decently and equally as

American citizens.

4. Respondents, and the United States to a somewhat

lesser degree, also seek to obscure and avoid the continu

ing constitutional violation by asserting that it does not

warrant the relief fashioned by the District Court because

the “ three distinct school systems involved in this case are

no longer dual systems; each is a unitary system” (St. Br.

52; see id., 50-88).7 Logically, this assertion begs the ques

tion, of course; factually, it ignores the specific, detailed

findings to the contrary of the District Court (see PI. Br.

42-44, 64-66; RSB Br. 12, 37-43, 69, 104-06) that all three

school divisions, whether considered separately or together,

remained segregated at the time when the county and state

defendants were brought before the court and when relief

against them was ordered;8 legally, the argument rests

7 The assertion by the United States that the District Court “as

sumed” or “presumed” that all three systems were operating* unitary

systems (U.S. Br. 2, 8, 9, 10) is negated by the very portion of the

lower court’s opinion cited by the government (338 F. Supp., at

104, Pet. A. 238), which is set out in full in text at p. 13 infra.

Interestingly, the United States nowhere in its Memorandum itself

advances the thesis that any of these school divisions had become

“unitary” during this litigation. Compare U.S. Br. 7 n. 8, 17.

_8 Ordinarily, the existence of a legal violation or other condition

giving rise to a cause of action is determined as of the time litiga

tion is filed. E.g., United States v. Board of School Commissioners

of Indianapolis, No. 72-1031 (7th Cir., February 1, 1973), slip op.

at p. 13, ajf’g 332 F. Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971) ; United States

v. Aluminum Company of America, 148 F.2d 416 (2d Cir. 1945) •

cf. United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U.S. 629 (1953). As we

pointed out in our opening briefs (PI. Br. 64-66; ESB Br. 69),

9

upon a misrepresentation of the meaning of the District

Court’s findings as to Richmond,9 and upon a misconcep

tion that HEW satisfaction with the belated desegregation

plans for Henrico and Chesterfield also satisfied the Con-

there is no issue as to an initial violation. And the Court of Ap

peals agreed that there was a continuing, unremedied violation at

the time of joinder (see 462 F.2d, at 1065, Pet. A. 571-72). There

was, therefore, no lack of power in the District Court to fashion

an appropriate remedy. In any event, as the District Court found,

racially segregated schools within each division had not been dis

established effectively even at the time the decree was entered.

9 By isolating various portions of the District Court’s August 17,

1970 opinion and April 5, 1971 opinion from their context, re

spondents seek (St. Br. 6-16) to convey the impression that the

District Judge had been fully satisfied that an effective, operable

plan for Richmond had eliminated all vestiges and effects of school

segregation—and thereafter ordered the plan changed because he

accepted educational, nonconstitutional justifications for the

change. Study of the entire opinions demonstrates the inaccuracy

of this characterization.

The District Court’s August 17, 1970 comments regarding the

estimated efficacy of the Poster Plan (St. Br. 14) were intended

to emphasize the contrast between the relative effectiveness of the

plaintiffs’ plan and those which had theretofore been submitted by

the Richmond School Board. It deserves emphasis that the court’s

remarks were made in the light of then governing law in the Fourth

Circuit, Swann v. Charlotie-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 431

F.2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970), rev’d 402 U.S. 1 (1971); thus, the refer

ence to “no intraetible remnant of segregation in the City of Rich

mond” which could not be reached within a reasonable busing time.

These comments were made entirely without reference to, or con

sideration of, the question whether a plan which achieved the max

imum feasible desegregation within Richmond might yet fail to

fully satisfy the Constitution in light of the particular circum

stances later developed on this record. No pleadings addressed to

that issue were pending at the time of the court’s ruling (an ear

lier motion to file a third-party complaint against the county school

boards was withdrawn August 7, 1970 [A. 17, 19]) ; neither the

counties nor the State Board (parties the District Court later

held should be joined before the issue was decided) was yet rep

resented in the litigation (see 36 R .; 51 F.R.D. 139, Pet. A. 48-57).

With respect to the District Court’s April 5, 1971 opinion, we

detailed the explicit reservations delineated by the court in our

opening briefs (PI. Br. 38-39, n. 62; RSB Br. 10-11).

10

stitution.10 * But the more basic failing of respondents’

approach is that it wholly misconceives the meaning of a

“unitary” school system, and the time at which a formerly

dual system can be said to have achieved a “unitary”

character.

Green v. Comity School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968) requires (1) consideration of

all feasible alternative plans of desegregation; (2) se

lection of the option offering the greatest promise of ef

fective relief; (3) evaluation in actual practice of the

plan selected; and (4) its modification, or the selection

of other alternatives, if evaluation demonstrates that the

plan has proved ineffective to eliminate racially identi-

10 While eourts have often said the HEW guidelines are entitled

to “ great weight” in evaluating the progress of desegregation, e.g.,

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d

729 (5th Cir. 1965) ; Kempv. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965),

the responsibility to adjudicate has never been abdicated to the ad

ministrative agency. See Lee v. Macon County Board of Education,

270 F. Supp, 859 (M.D. Ala. 1966) ■ Kemp v. Beasley, supra, 352

F.2d at 19: “ It is for the courts, and the courts alone, to deter

mine when the operation of a school system violates rights guar

anteed by the Constitution.” Several factors in this case support

the District Judge’s determination to probe further than the prof

fered “ HEW approval” of Henrico and Chesterfield schools. The

exhibits referred to by respondents (St. Br. 10-12) respecting

Henrico, for example, demonstrate that HEW’s characterization of

the system as “unitary” in 1969 (Ex. A. 97e) was no bar to the

requirement by the agency of further desegregation measures in

1970 and 1971 (Ex. A. 99e, 103e). Furthermore, the District Court

had reason to believe in the light of this litigation that HEW

might be applying less stringent standards than the Constitution

required. See 317 F. Supp., at 563-66, Pet. A. 13-20. The same

conclusion has been reached by another district court in a lawsuit

brought to compel compliance with the law by the agency. Adams

v. Richardson, Civ. No. 3095-70 (D.D.C., November 16, 1972 [memo

randum opinion], February 16, 1973 [order]). And in any event,

the District Court found that vestiges of the dual system remained

in each of the counties at the time of the hearing and that they

were not “unitary” when its decree was entered.

11

liable schools.11 The notion of a “unitary” system was

carefully explained in Stvann in both conceptual and op

erational terms. Conceptually, it describes a system that

has “ achieved full compliance with this Court’s decision

in Brown I.” {Swann, 402 U.S., at 31). Operationally, it

describes a finding whose consequence is that a federal

district court must dismiss a school desegregation case

as closed and finished business. {Swann, 402 U.S., at 31-

32.) But in light of Green, Raney v. Board of Education,

391 U.S. 443 (1968), and cognate cases,12 it is perfectly

plain that the finding of “unitary” character and conse

quent dismissal cannot come so soon as a plan has been

11 Thus unitary status is not achieved with initial selection of a

plan, but only when it has been shown that the plan is fully ef

fective in practice or that no feasible alternatives promising .greater

prospect of effective relief are available. As the District Court

stated,

Against this background the “desegregation” of schools within

the city and the counties separately is pathetically incomplete.

Not only is the elimination of racially identifiable facilities im

possible of attainment, but the partial efforts taken contain

the seeds of their own frustration. As before, and as courts

have seen happen elsewhere and sought to prevent, racially

identifiable black schools soon became almost all black; Rich

mond has lost about 39% of its white students in the past two

years. Time and again courts have rejected half-measures as

insufficient to fulfill school authorities’ affirmative duty, well

aware that otherwise the achievement will be only temporary.

That school authorities may even in good faith have pursued

policies leading to some desegregation and may in fact have

achieved some results does not relieve them of the remainder

of their affirmative obligation. Clark v. Board of Education

of Little Bock School District, 426 F.2d 1935 (8th Cir. 1970).

If the existing assignment program, he it by freedom of choice,

a pupil placement system, residential zoning, or some combina

tion thereof, does not, upon consideration of alternative means,

work effectively to abolish the dual system, it is legally defec

tive. [citations omitted] (338 F. Supp., at 103-04, Pet. A.

237-38). (emphasis added).

12 E.g., Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 446 F.2d 911 (5th

Cir. 1971) ; Wright v. Board of Public Instruction of Alachua

County, 445 F.2d 1397 (5th Cir. 1971).

12

adopted which the District Court believes will finally sat

isfy constitutional requirements. The finding and dismissal

must wait until the District Court has observed the opera

tion of the plan in actual practice and has concluded that

it is working in such a fashion that “ ‘the goal of a de

segregated, non-racially operated school system is rapidly

and finally achieved” ’ (391 U.S., at 449).

Palpably, this stage had not arrived in any of the three

school divisions—Richmond, Chesterfield or Henrico—at

the time of the District Court’s decree, or of the Fourth

Circuit’s reversal; nor has it yet arrived in any of the

three divisions. Therefore, unless the explicit language

of Green, Swcmn, and Raney is ignored, none of the three

divisions can be called “unitary” or relieved of the con

tinuing power of a federal court to modify and extend

desegregation remedies as needed,13 until full “unitary”

status is achieved.

It was for this reason that the District Court properly

concluded that the original constitutional violation of ra

cially segregated public schools in the Richmond area had

never been remedied and that the court was empowered

and obligated to address its remedial process to that con

tinuing violation with due recognition of the fact that the

“maintenance of segregation in an expanding community

. . . creates problems, when a remedy must eventually be

found, of a greater magnitude in the present than existed

13 E.g., Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 417 F.2d 801

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969) (freedom-of-choice);

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education, 436 F.2d 856

(6th Cir. 1970), 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S.

1001 (1972) (geographic zoning) ; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 453 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972) (feeder pat

terns).

13

at an earlier date . . . (338 F. Supp., at 91, Pet. A. 210).

As the District Judge wrote:14 *

The institution within the three existing school dis

tricts of something which might in some other context

pass for desegregation of schools is a phenomenon

dating at best from the opening of the 1971-72 school

year, which took place during the trial of this case.

Prior thereto each system was in some respect non-

unitary, and the Court is not fully advised as to the

current status of the county system[s]. Even were

each existing system, considered in a vacuum, as it

were, to be legally now unitary within itself, the

question still remains whether state policy having the

effect of preventing further desegregation and fore-

seeably frustrating that which has been accomplished

to date may be imposed upon a very recently achieved

desegregated situation. Momentary unitary status—

assuming it existed here, which has not teen shown—•

will not insulate a school division from judicial super

vision to prevent the frustration of the accomplish

ment. (338 F. Supp., at 104, Pet. A. 238). (emphasis

added).

B. The Issue of Remedy

1. Respondents apparently agree with petitioners that,

if a constitutional violation is established upon this rec

ord, the power of the District Court to remedy it by an

interdivision desegregation plan is unquestionable. (See

PI. Br. 62-82.) We take this to be the meaning of re

spondents’ passing immediately from the issue of “ con

14 As noted above, see pp. 8, 12, note 11 supra, the District

Court found as a fact that each of the school divisions was non-

unitary, and further that Richmond could not itself end its non-

unitary system because of the State’s long delay in commencing

compliance with Brown. (See PL Br. 88-100.)

14

stitutional violation” (St. Br. 50-87) to the “Factors to

Be Weighed in Determining the Validity of the District

Court’s Remedy” (St, Br. 87; see id., 87-104)—factors that

are meaningful only as a matter of discretion, not of

power. (See PI. Br. 82-100.) And as we have noted above,

the government states the issue solely in terms of discre

tion. (U.S. Br. 2.)

2. The arguments of both respondents and the United

States addressed to remedy are predicated upon their con

tention that the District Court approved an inter-division

desegregation plan for the sole purpose of achieving a

viable racial mix. (See, e.g., St. Br. 88, 96, 104; U.S. Br.

2, 9, 11, 17, 21.) We have previously considered this

assertion in note 3 supra. We reiterate the point here

because of the pivotal position accorded to the notion

by respondents and the government.

The District Court was concerned—as a reading of its

entire opinion or the entire section containing its general

findings and legal conclusions (338 F. Supp., at 79-116,

Pet, A. 185-263) will readily make clear—with the effec

tiveness of a remedy for the long-continued constitutional

violation.16 Having evaluated in successive, actual opera

tion (1) the freedom-of-choice plan, (2) the interim plan,

and (3) Plan III, the court ultimately concluded that inter

division assignments provided the only realistic means to

eliminate the persisting racial identifiability of the schools.16

16 The respondents’ and government’s briefs, focusing as they do

on the non-issue of “violation,” ignore entirely any discussion of

the effectiveness of the various plans that were put before the Dis

trict Court.

16 The United States suggests that the District Court engaged in

circular reasoning by making an initial arbitrary determination to

look outside Richmond in measuring racial identifiability and then

deciding that an effective means of eliminating that identifiability

would require pupil reassignments outside Richmond. (See U.S.

15

The strenuous efforts of the respondents and the United

States to rewrite the District Court’s opinion (see note 3

supra) are ultimately futile.17

3. Most of the other factors discussed by the respon

dents as bearing on the District Court’s exercise of discre

tion have been canvassed in our principal briefs and need

not be rehashed here. To the extent that they do not ignore

or go beyond the record,18 * respondents essentially substi

tute their own factual or judgmental conclusions for those

of the District Court, and thereby seek impermissibly to

Br. 13-15.) The government overlooks the facts that the District

Court was concerned with: (i) the many traditionally black Rich

mond schools which had never been effectively desegregated, under

free choice, the interim plan or Plan III, and which therefore

presumptively retained their racial identities (see PI. Br. 5-6, 11-13,

43, 89-90; RSB Br. 24-25, 36-37, 69); (ii) the evidence reinforcing

that presumption of identity, i.e., the testimony defining the nature

of racial identifiability and how it is perceived (see PI. Br. 67, 86-

100; RSB Br. 62-64) ; (iii) the evidence indicating the permeability

for all other community concerns of the city-county boundary lines

(see PI. Br. 25-29, 94-95; RSB Br. 15-22) ; and (iv) the evidence

indicating that the lines were freely crossed by the community’s

educators for valid educational purposes and had been so crossed

in the past for the invalid purpose of segregation (see PI. Br. 22-

24, 29, 84-86, App. E, le-5e; RSB Br. 64-67, 77-82). It was this

complex of factors and not an arbitrary preference for majority-

white schools which led the District Court to explore “ racial iden

tifiability” in the context of the greater Richmond area.

17 The distortion of the District Court’s opinion required by

these efforts is indicated by the Fourth Circuit’s comment that the

District Court “apparently adopt [ed] Dr. Pettigrew’s viable racial

mix theory,” 462 F.2d, at 1063 n. 4, Pet. A. 568. That is simply

not supported by a fair reading of the District Court’s general find

ings and conclusions of law (338 F. Supp., at 79-116, Pet. A.

185-263).

18 Compare, e.g., St. Br. 89-90 with PI. Br. 30-33, 90-97, App. F,

lf-4f, and RSB Br. 22-27, 69-70, 107-08; St. Br. 92-98 with PI. Br.,

App. C, lc-3c, App. D, ld-3d, App. E, le-5e, and RSB Br. 32-34,

48-50; St. Br. 98-100 with PI. Br. 22-23, 47-48 n. 67, 68-69 n. 100,

and RSB Br. 52-53, 79 n. 75; St. Br. 100-02 with PI. Br. 83 n. 135,

App. D, 2d-4d, and RSB Br. 106-07.

16

upset that court’s “broad discretionary power” in “ shaping

equity decrees.” 19

4. One point only at St. Br. 87-104 and U.S. Br. 17-21

seems to us to call for a reply. This is the assimilation of

San Antonio School District v. Rodriguez, 41 U.S.LW.

4407 (U.S., March 21, 1973), to respondents’ own concep

tion of “ local control.” (St. Br. 92-93; U.S. Br. 20-21.) We

have already pointed out at PL Br. 22-24, 84-86, App. E,

le-5e; RSB Br. 64-67, 77-82, that “ local control” in Vir

ginia is an accordion which collapses or expands as re

quired to pipe the tune of racial segregation and resistance

to desegregation in the public schools. For the one thing

that is clear on this record is that from 1870 to the time

of the District Court’s decision, with respect to racial mat

ters all school divisions either acceded to the directives

of, or surrendered control to, state authorities. We have

also noted that, to the extent that “ local control” is a real

concern and is not “racially based” (see PI. Br. 85, n. 137;

RSB Br. 78, n. 73), it is amply accommodated by the spe

cific provisions of the Richmond School Board plan ap

proved by the District Court.20

19 Lemon v. Kurtzman, 41 U.S.L.W. 4467, 4469 (U.S., April 2,

1973, opinion of the Chief Justice).

20 See PI. Br., App. C, le-3c, App, D, ld-3d, App. E, le-5e; RSB

Br. 32-34, 48-’50. To summarize, consolidation was preferred by

the Richmond School Board in part because it allowed greater

local control than inter-division assignment pursuant to contract.

(338 F. Supp., at 84, 191, Pet. A. 195, 430; see PI. Br. 61-62;

RSB Br. 49-50.) Cf. Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia,

407 U.S. 451, 454-55 (1972). The Board’s plan also provides for

the creation of six administrative subdivisions, each with its own

local board to which are delegated decision-making powers over

various curricular and administrative matters—the very method

which has proved effective in Fairfax County, Virginia. (See 338

F. Supp, at 191-92, Pet. A. 430-31; PI. Br. 47-48, App. D, 3d; RSB

Br. 49, 106.) Respondents’ assertions of financial difficulties must

17

5. We address finally respondents’ argument that “ [t]his

Court must not say that black majority schools are in

trinsically inferior or that black majority schools impose

a feeling of inferiority on those black students who attend

them” (St. Br. 48; see id., 75-78, 85-86). The argument

would lie better in the mouths of persons who had not

penned black children into segregated schools during dec

ades before and after Brown, and who now advance it in

the service of perpetuating that same segregation. The

sly suggestion that “ it is the N.A.A.C.P.” (St. Br. 76; sic)

which has latterly invented the inferiority and degradation

of the Southern “black” school requires neither analysis nor

response. It is a patent outrage.

In Brown, after noting the finding of the lower court in

the Kansas case that “ segregation of white and colored

students has a detrimental effect upon the colored children

[and that the] . . . impact is greater when it has the sanc

tion of the law; for the policy of separating the races is

usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro

group . . . ” , this Court stated:

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological

knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this find

ing is amply supported by modern authority. Any lan

guage in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this finding is

rejected. * *

be weighed against the total lack of any such problems in the ad

ministration of joint and regional schools throughout Virginia for

many years (see PI. Br. 22-23; RSB Br. 64-65), in light of the

existence of state laws dealing specifically with the allocation of

financing responsibility in a consolidated school system (see Pet,

A. 611-12, 621; PI. Br. App. D, 3d; ESB Br. 1.06-07), and in

light also of the present power of state officials to require levels

of expenditure sufficient to meet state-mandated minimum stan

dards of educational quality (see Pet. A. 621-22; PI. Br. App. C,

lc n. lc, App. D, 3d-4d).

18

Respondents and the government apparently seek to cast

doubt on the continued vitality of this finding through gen

eral and vague reference to a body of contemporary educa

tional research (St. Br. 76-77; U.S. Br. 11). The relevance

of their assertion to this case is dubious at best since this

Court has never held it a prerequisite to relief dismantling

a dual school system that black plaintiffs demonstrate they

have suffered specific psychological harm in segregated

schools or will make specific gains in integrated schools.

The assertion also disregards, of course, the abundant tes

timony in this record, credited by the District Court, sup

porting the conclusion that racially identifiable schools do

harm black children. (See RSB Br. 83-87.)

In any event, the implication that current educational

research is at odds with the finding of Brown does not stand

examination. Indeed, every major study conducted since

1954 supports and reinforces the conclusion that racial seg

regation in the public schools adversely affects the motiva

tion and educational development of black children.21

Some researchers have questioned past assumptions that

public schools are a principal instrument for establishing

equality of status and condition. Some have challenged the

notion that there is a demonstrable correlation between

educational expenditures and the quality of education. See

authorities cited in San Antonio School District v. Rodri

gues, 41 U.S.L.W. at 4420. All, however, agree that racial

composition of the classroom is a critical school factor in

determining educational outcomes.22 HBW’s most recent

21 See Office of Education, Equality of Educational Opportunity

[The Coleman Report] 302-10 (1966) ; U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights, Racial Isolation in the Public Schools 96-114 (1967);

Mosteller and Moynihan (Eds.), On Equality of Educational Op

portunity 41 (1972); Jeneks et al., Inequality 102, 109 (1972). 23

23 Jeneks, for example, concludes that the elimination of “racial

and socio-economic segregation in the schools might reduce the test

19

report on the subject, after reviewing evidence compiled in

several communities, summarizes the findings as follows:

“ [EJvidence of gains [through desegregation] combined

with the absence of alternative educational strategies

with demonstrated superior effectiveness, suggests the

high educational importance for desegregation in im

proving black academic achievement . . . ” (Department

of HEW, The Effectiveness of Compensatory Educa

tion, Summary and Review of the Evidence 176

(1972)).

Practical experience in communities that have desegre

gated their schools supports the research findings that de

segregation is beneficial and negates the veiled suggestion

that the plan approved here may be politically unworkable.

In two 1972 studies covering fourteen school districts that

had implemented desegregation plans, the U.S. Commis

sion on Civil Rights found that students “have adjusted

quickly and smoothly to the new school environment, often

despite fears and anxieties of their parents,” that “ school

desegregation had begun to make inroads on the entrenched

racial isolation and hostility with which most pupils and

teachers confronted each other in segregated systems,” that

communities had taken action often vigorous and creative to

head off problems, and that there was “widespread accept

ance of desegregation by those most intimately involved in

the educational process—the students and the teachers.” 23 * 23

score gap between black and white children and between rich and

poor children by 10 to 20 percent.” See also “Perspectives on

Inequality,” 43 Harvard Educational Review (No. 1) at 39 If. (Feb

ruary, 1973).

23 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Five Communities: Their

Search for Equal Education 1-2 (1972) ; U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights, The Diminishing Barrier; A Report On School Desegrega

tion in Nine Communities 1-3 (1972). The fourteen communities

20

In snm, the issue in this case, as the government acknowl

edges, is a constitutional one. The research findings of edu

cators and sociologists were relevant only as considerations

for the district court to weigh in determining the most

appropriate form of relief after finding a constitutional

violation. The government’s suggestion that the courts are

being asked to choose among “various educational and

sociological theories” (U.S. Br. 12) is a smoke screen.

We submit that the scope of remedial discretion should

still be defined in terms of the feasibility of available alter

natives, and that on this record inter-division assignments

have been established as feasible, workable and education

ally sound. The use of inter-division assignments as a de

segregation tool in this case will provide the only means

of avoiding the stark reality of black schools in Richmond,

and white schools in Henrico and Chesterfield. Yet such

assignments may be effected without expanding the time

or distance of pupil transportation presently afforded

within the individual school systems.

included several, e.g., Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Tampa-Hillsborough,

whose plans are similar to the plan adopted in this case. Experience

with a desegregation plan implemented in January, 1973 in Prince

Georges County, Maryland, the tenth largest school district in the

nation, has also been positive. See, e.g., Washington Star-News,

February 13, 1973, p. B-l.

21

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, and those set out in the prin

cipal briefs of the petitioners, the judgment of the Court

of Appeals should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

GEORGE B. LITTLE

JAMES K. CLUVERIUS

Browder, Russell, Little

& Morris

1510 Ross Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

CONARD B. MATTOX, JR.

City Attorney

City Hall

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Petitioners

in No. 72-549

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

LOUIS R. LUCAS

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

WILLIAM A. TAYLOR

Catholic University

Law School

Washington, D.C.

JAMES R. OLPHIN

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

WILLIAM T. COLEMAN, JR.

Fidelity-Phila. Trust Building

Philadelphia, Pa. 19110

M. RALPH PAGE

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University

Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioners

in No. 72-550

M EIIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219