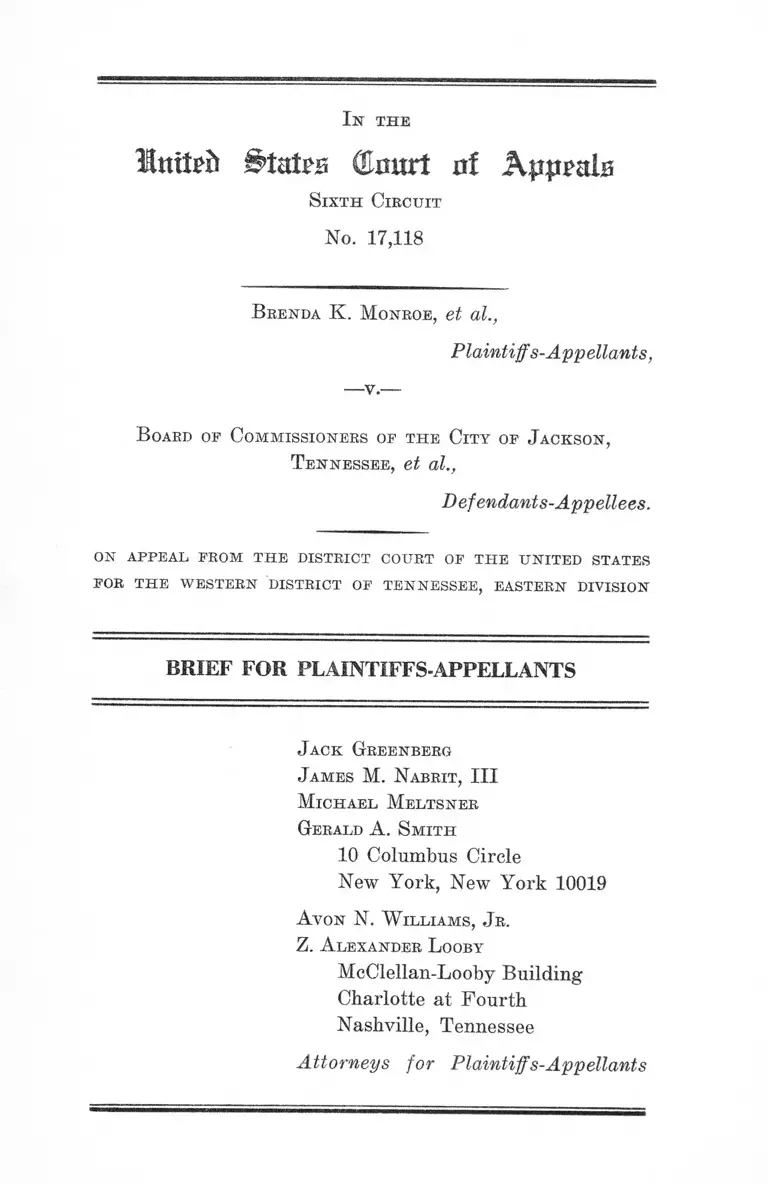

Monroe v. City of Jackson Board of Commissioners Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Monroe v. City of Jackson Board of Commissioners Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1967. 0028c71d-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ac483504-7291-4b06-8206-a8b7b45317a2/monroe-v-city-of-jackson-board-of-commissioners-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

lmte& States at Amalfi

S ix t h C iecu it

No. 17,118

B renda K. M onroe, et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

B oard of C ommissioners of t h e C it y of J ackson ,

T ennessee , et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

on appeal from t h e district court of th e united states

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, EASTERN DIVISION

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

M ich ael M eltsner

Gerald A . S m ith

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiam s , J r .

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

1

Statement of Questions Involved

(1) Whether a school board under a duty to disestablish

its segregated school system, may, consistently with

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 349 U.S.

294 and subsequent decisions of the United States

Supreme Court, draw junior high school zone lines

and adopt transfer policies so as to foster and

maintain a segregated school system!

The District Court answered this question “Yes” and

appellants contend the answer should have been “ No.”

(2) Whether appellants’ constitutional right to non-racial

allocation of faculties is met by a court order placing

the burden of achieving faculty desegregation on

teachers, by the adoption of a teacher freedom of

choice plan, where the school board has historically

adhered to policies and practices which promote

racial segregation.

The District Court answered this question “Yes” and

appellants contend the answer should have been “ No.”

(3) Whether a school board required by decisions of the

United States Supreme Court to eliminate racial

restrictions, distinctions and discriminatory prac

tices may give support to “ private” groups which

discriminate against Negroes in sponsoring activities

during school hours involving school facilities, pupils,

and personnel.

The District Court answered this question “Yes” and

appellants contend the answer should have been “ No.”

I N D E X

BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of Questions Involved ..... -............................ i

Statement of Facts ............................................................ 1

Prior History ........ 2

School System ........................... 4

School Desegregation Plan ........ 5

Teacher Segregation ................................................... 5

Gerrymandering—Junior High Schools ...... 7

Segregation— School Connected Activities ................. 11

A e g u m e n i —

I. The Board in Disestablishing Its Segregated

School System Has An Affirmative Duty To

Adopt Zoning and Transfer Policies For

Junior High Schools Which Will Facilitate The

Immediate and Meaningful Reform of A State-

Created Pattern of Segregation ....................... 13

II. A “ Freedom of Choice” Faculty Desegregation

Plan is Tantamount to No Plan At All, and

Falls Far Short of Vindicating the Right of

Negro Children to An Education Free From

Any Consideration of Race as Guaranteed By

the Fourteenth Amendment to The Constitu

tion of The United States ......... ........... ............. 20

III. School Board Participation In and Support

For Programs Which Discriminate On the

Basis of Race Is Prohibited By The Four

teenth Amendment to The Constitution of The

United States ...................................................... . 26

Relief ..................................................................................... 29

IV

T able of Cases

PAGE

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 ..... ............... ..... ...... . 24

Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent School District,

241 F.2d 230 (5th Cir. 1957) ...................................... 17

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ................... 17

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S.

103 ..... ................... ............ ........ .............................. .17,20,22

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C.

1955) ............................ ............... ............. ......... ..... 16, 17,18

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 .......1, 2, 27, 28

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 ____1,14,17, 20

Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County,

Va., 245 F. Supp. 549 (W.D. Va. 1965) ..... ..... ....... 21

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715 ......................................................................... .......... 28,29

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U.S. 263 .............................. 17, 20

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 ...........................14,16, 28, 29

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) ______ 26

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F.2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960), cert.

denied, 364 U.S. 933 ............. ................... ............... ..... 16

Evans v. Newton,----- - U .S .------ 15 L.ed. 2d 373 ............ 28

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

No. 10,214 (4th Cir. April 6, 1966) ......... ............. 21,22

Gilliam v. School Board, Hopewell, Va., 382 U.S. 103 .... 20

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 .............................. 15

V

Goss v. Board of Education, 301 F.2d 164 (6th Cir.

1962) .................................. ............................ .................. 18

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 ........... 17,18, 20,

23, 28, 29

Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society, 355 F.2d

718 (4th Cir. 1966) ..................................... ....... ........ 29

Kelley v. Board of Education of Nashville, 270 F.2d

209 (6th Cir. 1959) ......... ...................................... ..... . 18

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) ...........17, 25

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County, Va.,

249 F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va. 1966) ............. ......... 22,26

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 ...................... 16

McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 339 U.S. 637 ............. ............. 27

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

319 F.2d 571 (6th Cir. 1963) .......................... ........... 23

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of City of Jackson,

Tennessee, 221 F. Supp. 968 (W.D. Tenn. 1963) ....3, 4, 9

Monroe v. Madison County Board of Education, 229

F. Supp. 580 (W.D. Tenn. 1963) ........................ ......... 2

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of City of Jackson,

Tennessee, 244 F. Supp. 353 (W.D. Tenn. 1965) ....... 2

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n., 202 F.2d

275 (6th Cir. 1953) ............................................ ......... 28

Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis,

302 F.2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) ............. ......... .......... . 13

Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis,

333 F.2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ............. ...... ...... .......... . 13

PAGE

VI

Price v. Denison Independent School District Board of

Education, 348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965) ________ 25

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 ...... ......... ............ ......... 17, 20

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) .......................17,25

Taylor v. Board of Education of City School District

of New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181; 195 F. Supp. 231

(S.D.N.Y. 1961), aff’d 294 F.2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961) .... 15

Thompson v. County School Board of Hanover County,

Va., Cir. No. 4274 (E.D. Va., January 27, 1966) ....... 22

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 ........... ....... 17, 20

PAGE

S tatutes

Civil Rights Act of 1964

Title VI (42 U.S.C.A. §2000d) ................................... 24

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 60 .............. 4

O th er A uthorities

Fiss, “Racial Imbalance in the Public Schools: The

Constitutional Concepts” , 78 Harv. L. Rev. 564

(1965) ......................... .......... ............................................ 18

N.E.A., “Report of Task Force Appointed to Study

the Problem of Displaced School Personnel Related

to School Desegregation” (December 1965) ............... 21

PAGE

Ozmon, “ The Plight of the Negro Teacher” (Septem

ber, 1965) .......................................................................... 21

Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegrega

tion Plans Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare, Office of Education (March, 1966) ..-.15,19,24,

25, 26

Southern Education Reporting' Service, “ Statistical

Summary of School Segregation-Desegregation in

Southern and Border States” , 15th Revision (De

cember, 1965) ............................................................ ..... 23

APPENDIX

PAGE

Relevant Docket Entries ................. ...... ..................... . la

Motion for Further Relief and to Add Parties, etc..... 3a

Exhibit “K ” Annexed to Foregoing Motion—

Affidavit of Thomas B. Davis .......................... . 19a

Exhibit “L” Annexed to Foregoing M otion -

Affidavit of Mrs. Freddie Moore ........................ 21a

Exhibit “M” Annexed to Foregoing Motion—

Affidavit of Mrs. Carl Brown ......................... . 23a

Exhibit “ N” Annexed to Foregoing Motion—

Affidavit of Mrs. Annie L. Merriweather ......... 25a

Replication of Defendants to “ Motion for Further Re

lief” ........... 27a

Pre-Trial Order ............................................... 44a

Supplemental Replication to Motion of September 4,

1964 .................................... 46a

Petition ......................... 56a

Exhibit A Annexed to Petition— Map of Jackson,

Tennessee ................................................ 57a

Specification of Objections Filed by Plaintiffs ........... 58a

Additional Motion for Further Relief ....................... 61a

v i i i

IX

Replication of Defendant to Additional Motion for

Further R e lie f.................................................... ........... 67a

Exhibit A Annexed to Foregoing Replication—

The 1965-66 School Calendar ............................ 76a

Excerpts From Transcript of Testimony ........ .......... 78a

Memorandum Decision ........................... 286a

Order .............................................. 311a

Notice of Appeal ......... .................... ....... ........................ 318a

T e s t i m o n y :

Plaintiffs’ W itnesses:

Roger W. Bardwell—

Direct ...................................... 159a

Cross .................................... 174a

Redirect ..... 190a

Albert Porter—

Direct ......... .......... .............. ...................... ....... . 192a

Cross ............................................................197a, 254a

Redirect ................................. 261a

Merle G. H erm an-

Direct ......... 198a

Cross .............. 214a

Dr. Eugene Weinstein—

Direct .............. 221a

Cross ........ 233a

Redirect ............................................................. 250a

Recross ................................................................ 250a

PAGE

Defendants’ W itnesses:

C. J. Huckaba—

Direct ...... .................

Cross ..... .......... .........

Mrs. James McLemore—

Direct .................. .....

Cross ..........................

PAGE

78a

96a

270a

272a

E x h i b i t s :

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits: pao,e

12— School Zone Map ............. 104a

12 to 21— School Zone Maps and Docu

ments .............................. 163a

20— Enrollment Lists ................ 194a

26—Enrollment Lists ........................... 219a

Printed

Page

280a

Defendants’ Exhibits-.

1 to 9— Maps ________ ____________ 79a

10 to 11—Maps ............................... . 94a

Omitted.

In t h e

lutfrfc §>tat£0 QInurt of Appeals

S ix t h C ircu it

No. 17,118

B renda K. M onroe, et al.,

Plaintiff's-Appellants,

—v.—

B oard op C ommissioners op th e C it y of J ackson ,

T ennessee , et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Statement of Facts

This is an appeal by Negro appellants from the district

court’s order denying certain requests contained in their

Motion for Further Relief (3a-17a), Additional Motion for

Further Relief (61a-66a) and their Specifications of Ob

jections to defendants’ plan for unitary non-racial zones

for junior high schools (58a-60a). Appellants seek the

aid of this court in bringing about substantial, as opposed

to token, desegregation in the public schools of Jackson,

Tennessee in compliance with decisions of the United States

Supreme Court.

Appellants won some of the relief sought in the lower

court, but were denied or obtained inadequate relief on

2

several requests including: 1) The court’s refusal to dis

approve assertedly gerrymandered unified junior high

school zone lines. Its opinion was that “ [t]he proposed

junior high school zones proposed by defendants do not

amount to unconstitutional gerrymandering” (315a). 2) A p

pellants’ application for an order requiring faculty deseg

regation was also denied, but the court ordered the Board

to permit teachers to apply to teach in schools where pupils

are all or predominantly of another race (315a-316a).

3) Discrimination in curricula and extra-curricula activities

was enjoined but the court refused to enjoin the Board

from giving support to private groups which sponsor

activities involving school facilities, pupils, and personnel,

and discriminate in these activities against Negro pupils

and personnel (316a). The district court’s opinion is re

ported in 244 F. Supp. 353 (W.D. Tenn. 1965).

Prior History

The original complaint1 in this action was filed by Negro

children and their parents on January 8, 1963, almost

nine years after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483. The gravamen of

their complaint was that the City Board of Commissioners

were operating a compulsory segregated school system in

Jackson, Tennessee in violation of rights secured to plain

tiffs and members of their class by the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. Plaintiffs sought

a declaratory judgment and preliminary and permanent

1 Monroe v. Madison County Board of Education, 229 F. Supp. 580

(W.D. Tenn. 1963), was combined with this case in the original com

plaint, but was severed for trial. An appeal in the Madison County case

(No. 17,119) is pending in this court.

3

injunctive relief. The general relief sought was an in

junction against the continued operation of a compulsory

bi-racial school system or alternatively an order requiring

defendants to present a plan for the reorganization of their

compulsory bi-racial school system into a unitary non-

racial system.

January 19, 1963 the District Court found that the

Jackson School Board had denied the Negro plaintiffs

admission to white schools to which they had applied on

the basis of race and issued its preliminary injunction

against the Board requiring admission of the individual

named plaintiffs to schools to which they had applied.

February 26, 1963, appellee filed its answer, denying

that it had operated compulsory racially segregated schools

in that beginning with the 1961-62 school year it began

accepting individual applications for transfer and enroll

ment of Negro children in white schools pursuant to pro

visions of Tennessee’s Pupil Placement Act and since that

time seven Negro children had been admitted to white

schools in the city school system. The material allegations

of the original complaint were, otherwise, substantially

admitted.

Appellants’ Motion for Summary Judgment was granted

on June 19, 1963, and the Board was ordered to file a com

plete plan for desegregation and elimination of segrega

tion in the city school system. After defendant filed its

plan and plaintiffs filed specification of objections, the

cause was heard July 26 and 27, 1963. In an opinion

reported in 221 F. Supp. 968, the court approved a plan

requiring desegregation of the Jackson public schools within

four years, encompassing the first three grades in the

school year 1963-64, the next three grades in 1964-65 and

the two successive grades each year thereafter until com

4

pleted. The Board was authorized to use its reasoned

discretion in adopting admission and transfer policies as

long as they had no racial basis or purpose to delay deseg

regation. Pupils living in established attendance zones

were given a prior right to attend schools in those zones

over all others not residing therein. Pupils not living within

the limits of the City of Jackson could be admitted or

assigned to schools in accordance with the discretion of

the Board of Commissioners but the Board was not to

discriminate as to race in admitting or assigning pupils

to grades desegregated under the plan.

After the court’s order desegregating grades 1-3 for the

first year, school officials resegregated Negro pupils grad

uating from desegregated elementary and junior high

schools who had theretofore won admission to formerly

all-white schools as a result of the the court’s preliminary

injunction of January 19, 1963 and voluntary action of the

Board. After a hearing on plaintiffs’ motion for “ Appro

priate Relief” under Rule 60 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, Judge Brown entered an order protecting the

rights of Negro students above grade 3 and enrolled in

theretofore all-white schools, 221 F. Supp. 968, 973 (ad

dendum).

School System

As of the 1964-65 school year there were 7,804 pupils in

the Jackson School System. 3,194 (41%) are Negroes

(280a-285a). Of these, only 120 attend formerly all-white

schools, 2 above the 6th grade level (283a-285a). No white

students are enrolled in schools traditionally categorized

as Negro schools (280a-285a).

The entire system consists of 13 schools; 8 elementary,

3 junior high and 2 high schools. Eight of the 13 (5

5

elementary, 2 junior high and 1 high school) were hereto

fore attended by whites only. 5 schools (3 elementary,

1 junior high and 1 high school were formerly and are

now attended by Negro pupils only (280a-285a).

School Desegregation Plan

As of this appeal, the defendants are operating under

a plan which requires desegregation as follows: first

through third grades in the school year 1963-64, fourth

through sixth grade in the school year 1964-65, seventh

through ninth grades in the school year 1965-1966 and tenth

through twelfth grades in the school year 1966-67,2 when

the school system is to be totally desegregated (315a).

The Board is required to allow Negroes and whites to use

racial majority transfers to obtain assignments out of

their unitary zones if it continues to allow Negroes and

whites to use racial minority transfers to obtain school

assignments out of their unitary zone (313a). Each student,

however, is required each year to register in the school

of his unitary zone and thereafter apply for a transfer.

Direct registration in a school outside the students’ unitary

zone is not permitted (314a). Teacher desegregation is to

proceed under a “ freedom of choice” plan. This is effective

for substitute teachers during the 1965-66 school year and

all teachers beginning with the 1966-67 school year (315a-

316a).

Teacher Segregation

The Board of Commissioners has made no effort to as

sign teachers on an objective basis without regard to race

or color. In fact, they assert that “ integration of faculty

is not related to, nor necessary for the achievement of

Plaintiffs won acceleration in tlie lower court updating desegregation

in all grades by 1 year. See original time schedule pp. 4-5, supra.

6

elimination of compulsory segregation within the City

Schools of the City of Jackson (53a). They contend that

under the Constitution of the United States federal courts

are powerless to order assignment of school personnel

(54a). Defendants claimed that the destruction of the

entire city school was seeded in plaintiffs’ request for

faculty integration (42a). This fear wTas said by plaintiffs’

expert to be merely conjectural. His testimony revealed

at least three instances where faculty desegregation is

planned (Nashville) or has actually occurred (Wilson

County, Tennessee, Putnam County, Tennessee) and there

has been no mass exodus of white faculty personnel (247a-

248a). The student withdrawal feared by defendants (42a)

was recognized by Judge Brown as frivolous: “as you

know under the law of Tennessee, a child has to go to

school until he is I believe, sixteen years of age” (247a).

The testimony of Dr. Eugene Weinstein, plaintiffs’ ex

pert, indicates that continued faculty segregation causes

Negro schools to be stigmatized as “Negro” and newly

desegregated white schools, with all-white faculties to be

regarded as white and the existence of the stigma impedes

the ordinary rate of desegregation in the community

(223a). This is especially true when a pattern of faculty

segregation is considered along with the Board’s free

transfer policy (231a). “Faculty segregation tends to make

additional impetus to transfer out of a Negro school, be

cause it is obvious that it is Negro in all of its educational

environs and it tends to stigmatize a school as a Negro

school” (232a).

Testimony further reveals that faculty segregation tends

to deprive Negro children “of the opportunity of having

experience with white middle class values, with white people

presumably in a supportive relationship to them in the edu-

7

cational system. It tends to remove from them the oppor

tunity to have experience with another sub-culture that

they have to cope with later in life, whose values and

attitudes will be very important in the place they make

for themselves in subsequent life” (223a). Faculty segrega

tion also affects white pupils, they are deprived “ of the

opportunity to have experience with Negroes in a pro

fessional and authoritative role . . . confirming . . . existing

impressions in stereotypes the white students have”

(224a), and where faculties are composed of members of

a single racial group, white and Negro pupils will wonder

why only white teachers are allowed to teach whites and

vice-versa (239a). Based on the above principles Dr. Wein

stein concluded that faculties as well as students should

be desegregated in order to provide a completely deseg

regated education (224a).

Gerrym andering— ju n ior High Schools

The City of Jackson has three junior high schools.

Tigrett and Jackson Junior High are heretofore all-white

schools. Merry Junior High is an all-Negro school. Tigrett

is located in West Jackson, Merry in Central Jackson and

Jackson Junior High in the Eastern portion of the City.

These schools are divided by two irregularly drawn North-

South school zone lines which tend to follow racial neigh

borhood patterns.3 Observation of these zone lines, to

gether with racial neighborhood patterns “reveals that the

boundary zones for junior high attendance have been drawn

with the goal in mind to preserve racially segregated

3 See “ Exhibits Depicting the Gerrymandering of School Zones in Jack-

son, Tennessee Schools,” a blue spiral bound pamphlet prepared by

plaintiffs and containing seven exhibits using overlay maps and verbal

descriptions and marked as Exhibit 12. Appellants will refer hereafter

to Exhibits I through Y II therein by their Trial Exhibits numbers, 13

through 19. Reference here is made to Exhibit 17.

8

junior high schools to a large degree” (Tr. Ex. 17). There

is a concentration of Negro pupils in the Southwestern

portion of the Jackson zone, a smaller concentration of

Negro pupils in the Southeastern portion of the Tigrett

zone and some whites reside in the Merry zone. This

zoning coupled with appellees’ open transfer plan may he

used to promote complete segregation at the junior high

school level (Tr. Ex. 18).

The Board did not have completed information before

it when it drew up the junior high school zones approved

by the district court:

“ The Court is advised that the Jackson Junior High

School shown on the map is a new school just being

completed which will be in use by the time this plan

is effective. The present Jackson Junior High School

located at Headrick Avenue may be, or may not be

continued in service, a question not yet determined.

The map as presented does not include it but may

be amended later if the building is continued in ser

vice” (56a).

The Superintendent of Schools testified that Tigrett

Junior High, white, has a pupil capacity of 725, an enroll

ment of 678 (47 under capacity), its pupil-teacher ratio

is 26-1, new Jackson Junior High, white, has a pupil

capacity of 650, an enrollment of 401 (249 under capacity),

its pupil-teacher ratio is 25-1. While these two white

schools are almost 300 under capacity, all-Negro Merry

Junior High has an enrollment of 703, exceeding its capacity

by 3 and a pupil-teacher ratio of over 30-1. The school

board has taken bids to construct four additional class

rooms at Merry so as to increase its capacity by 120 (95a).

Apparently the fact that future enrollment levels in junior

high schools will tend to remain constant at about 100

9

above present enrollment was not considered in deciding

to go ahead with the construction (211a).

The Superintendent admitted that it was March, 1965

before it was decided to go ahead with the construction of

the Merry addition but refused to answer whether this

decision was made after it was found that Merry’s enroll

ment was 3 over its pupil capacity (136a). The Super

intendent would not say whether a single white student

is expected to enroll in Merry Junior High (136a-137a).

Regarding schools which have been desegregated under

the plan, Judge Brown set the following guidelines in 1963;

“ the Board may adopt any admission or transfer plan as

may, in its judgment be reasonable and proper, provided

however, that no admission or transfer will be based upon

race or have as its purpose the delay of desegregation as

contemplated by the plan.” Monroe v. Board of Commis

sioners of City of Jackson, Tennessee, 221 F. Supp. 968,

971 (W.D. Tenn. 1963). Faced with this order the school

board allowed 298 white and no Negro pupils from neigh

boring Madison County to transfer to five formerly all-

white elementary schools, while requiring eight Negro and

no white county transferees to enroll in two all-Negro

elementary schools (208a-209a). Anticipating desegrega

tion at the junior high level for the 1965-66 school year

defendants permitted 68 white and no Negro county trans

ferees to enroll in two formerly all-white junior high

schools while requiring four Negro and no white county

transferees to enroll in all-Negro Merry Junior High School

(208a). This practice obviously reduces the capacity of

these schools to accommodate Negro junior high pupils

who live within the City of Jackson.

At trial appellants’ expert witness, Mr. Herman, pro

posed the use of a feeder system for Jackson’s elementary

10

and junior high schools (200a). He suggested that junior

high zones should conform to elementary zones so that

rising sixth grade pupils would go to the junior high

school that takes pupils from the same school (200a). He

testified that the feeder system is both efficient and edu

cationally sound (207a) because it would result in “ an

integration of effort between the elementary schools and

the junior high schools where orientation procedures might

be developed. . . . The principals are able to work together

in enabling a sufficiently easy transition from the elemen

tary to junior high school. Also, from a guidance point

of view, it is well that schools have some association that

are teacher relationships and administrative relationships

which should be developed between feeder schools and the

schools into which the children are being enrolled” (200a).

Specifically appellants’ expert, Mr. Herman, recom

mended that elementary zones should be clustered around

junior high schools. Parkview (white, Tr. Ex. 13), Wash-

ington-Douglas (Negro, Tr. Ex. 13) and Whitehall (white,

Tr. Ex. 15) Elementary schools were suggested as appro

priate feeder areas for Jackson Junior High (white, Tr.

Ex. 17). Highland Park (white, Tr. Ex. 19), West Jackson

(white, Tr. Ex. 14) and South Jackson (Negro Tr. Ex. 14)

elementary were suggested as appropriate feeder areas for

Tigrett Junior High School (white, Tr. Ex. 17). Alexander

(white) and Lincoln (Negro, Tr. Ex. 15) Elementary

Schools were suggested appropriate feeder areas for Merry

Junior High School (207a). The feeder system proposal

was based on the assumption that some changes were neces

sary in elementary school zones (206a-209a). The Trial

Judge, in fact, did require some changes in elementary

zones (314a).

Air. Herman testified that pupil transportation is not

a great problem at the junior high level because pupils

11

in this age group are capable of using public transporta

tion facilities and sufficiently matured to take care of them

selves on the street (200a-201a). He pointed out that all

of the schools with the exception of Merry and South

Jackson had a great deal of flexibility in terms of capacity

and school capacity would not be a great problem in

rezoning’ the schools (210a).

The District Court felt that “ the value of the testimony

of these experts with respect to junior high schools was

somewhat undercut because they . . . assumed a duty to

maximize integration . . . [and] . . . that defendants had

the duty to adopt a ‘feeder’ system whereby certain ele

mentary schools would send their graduates only to a

particular junior high school” (297a). Judge Brown after

concluding “that the Constitution does not require integra

tion and that it only requires abolition of compulsory

segregation based on race” (292a), held that there was

no constitutional requirement that a “ feeder” system be

adopted (300a).

Segregation— School Connected Activities

Appellants in their Additional Motion for Further Relief

asked the district for an order “eliminat[ing] all racial

restrictions, distinctions and discriminatory practices from

all teacher in-service training' and professional or school-

related activities sponsored or supported by the City of

Jackson School System” (61a). A similar request was

made regarding “ cultural and/or recreational programs

conducted under the auspices of and/or with the direct

or indirect support or cooperation of the City of Jackson

School System” (61a).

Specifically, appellants complained that white and Negro

teachers were assigned separate in-service training days

12

(63a, 64a, 65a). Appellees did not deny this practice but

pleaded affirmatively that “ [t]he teachers themselves be

long to various teacher professional organizations, a mat

ter wholly beyond the control of the defendants” (72a).

Appellee admitted that Negro and white teachers are given

different holidays to attend their meetings (68a) but denied

that holidays are paid (72a). The trial court viewed the

question raised by these circumstances as one of internal

organizational policy (307a) but did not consider the ques

tion of whether the Board and hence the state may partic

ipate in any way in these segregated teacher activities.

The District Court also held that pupil plaintiffs had no

standing to raise the issue of segregated in-service training

for teachers (307a).

Appellants also complained that on February 11, 1965

segregated concert performances were given at Tigrett

Junior High School by the Jackson Symphony Orchestra.

White and Negro pupils in certain grades in the predom

inantly white city and county schools were all invited,

but no pupils in similar grades in the all-Negro schools

were permitted to attend the program (65a). Thus, almost

all Negroes, but no white pupils, were excluded from the

concert. Appellee admitted the allegation but replied that

the concert was sponsored by a private organization and

the city had no control over their activity (70a-71a). A l

though the concert performances were given in one of the

city’s schools, the court below viewed them as an “ outside

activity” and held that the “ occurrence does not constitute

unconstitutional discrimination” (306a).

13

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Board in Disestablishing Its Segregated School

System Has An Affirmative Duty To Adopt Zoning and

Transfer Policies For Junior High Schools Which Will

Facilitate The Immediate and Meaningful Reform of A

State-Created Pattern of Segregation.

Junior high school zoning in Jackson, Tennessee violates

the basic zoning standards set by this court in Northcross

v. Board of Education of City of Memphis, 302 F.2d 818,

823 (6th Cir. 1962);

Minimal requirements for non-racial schools are

geographic zoning, according to the capacity and facil

ities of the buildings and admission to a school accord

ing to residence as a matter of right.

Discrepancies in capacity and enrollment, as well as dif

ferences in the pupil teacher ratios at Negro and white

Junior High Schools (95a) make it perfectly clear that

the City of Jackson is not observing even the minimal

requirements. Moreover, these discrepancies indicate that

the board has failed “to demonstrate that the zone lines

of each school were not drawn with a view to preserve a

maximum amount of segregation.” Northcross v. Board of

Education of City of Memphis, 333 F.2d 661, 664 (6th Cir.

1964).

The Board obviously has an overall purpose to retain

pupils from the Negro community in Negro Junior High

schools and to retain pupils from the white community

in white Junior High schools. If this is not the case, ap

14

pellants find incomprehensible the fact that the Board

has committed itself to build additions at the all-Negro,

Merry Junior High school to accommodate 120 additional

Negro pupils (95a) while its two white junior high schools

remain substantially under capacity (95a) and only a small

increase in total Junior High enrollment can be predicted

for the future (211a). The Board’s conduct in this regard

is a flagrant violation of appellants’ right to attend schools

administered on a non-racial basis, Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1, and demonstrates that the Board has abdicated its

responsibility as imposed by Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 294, to adopt programs and policies which result

in the elimination of segregation.

Superimposed upon the Board’s racially oriented Junior

High zone lines (204a) is a freedom of choice plan which

has been used as an escape valve for white children

“ trapped” in Negro zones and a convenient tool with

which to encourage Negro children to transfer out of their

zones to all Negro schools (Tr. Exhibits 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,

18) (204a, 205a, 308a).

The following excerpt reveals the negative effect of this

zoning transfer system on the progress of desegregation:

Q. With a continued transfer system in the City of

Jackson, is it along the lines of an absolutely free

transfer system superimposed on that zone system

based on race, even though it works both ways—is

it your opinion that the condition of segregation

will continue to exist? A. Yes.

Q. Well, the zone lines have contributed to that

condition of seg'regation? A. Yes, the zone lines would

contribute to it and where they are not effective the

transfer system could be used for that purpose (205a).

15

In dealing with a similar zoning transfer situation the

Second Circuit in Taylor v. Board of Education of City

School District of New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181; 195

F. Supp. 231 (S.D.N.Y. 1961), aff’d, 294 F.2d 36 (2nd

Cir. 1961), was faced with evidence of zoning which created

racial segregation, and affirmed the district court order

to desegregate, the district court held:

. . . I see no basis to draw a distinction, legal or

moral, between segregation established by the formal

ity of a dual system of education, as in Brown, and

that created by gerrymandering of school district

lines and transferring of white children as in the

instant case. Cf. Gomillion v. Lightfoot, supra. [364

U.S. 339, 81 S.Ct. 125, 5 L.ed 2d 110] The result is

the same in each case: the conduct of responsible

school officials has operated to deny to Negro children

the opportunities for a full and meaningful educational

experience guaranteed to them by the Fourteenth

Amendment. (191 F. Supp. 192)

The United States Office of Education has recognized

that desegregation plans using a combination of zoning

and free choice may be used to limit desegregation and

requires boards to show that such combination plans “ will

most expeditiously eliminate segregation and all other

forms of discrimination” (emphasis supplied).4 This

standard can hardly be met when the superintendent is

unable to predict that a single white student is expected

to enroll in all-Negro Merry Junior High School (136a-

137a) even though a number of whites are zoned in the

4 Revised Statement of Policies For School Desegregation Plans Under

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, U.S. Department of Health, Edu

cation, and Welfare,.Office of Education, March 1966. Subpart C—Addi

tional Requirements for Voluntary Desegregation Plans Based on Geo

graphic Attendance Zones, §181.32.

16

area (Tr. Exs. 17, 18). In considering the adequacy of

any plan the courts must consider not only its abstract

constitutionality, but reasonable expectations as to how it

will work. Where all sides agree that a plan will more

than likely work to continue segregation patterns, it is

unconscionable and unconstitutional to approve the plan.

Such a plan plainly fails to perform the equitable duty of

undoing the effects of past wrongdoing. Cf. Louisiana

v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154, Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1, 7.

Given the long history of racial discrimination in the

Jackson school system, the delayed 1963 start of the

desegregation process in that community, together with

the Board’s lack of good faith5 and nearly contemptuous

disregard for lawful court orders,6 the Board in 1966

is required to do more than adopt policies which result

in mere token desegregation. See Evans v. Ennis, 281

F.2d 385, 394 (3rd Cir. 1960), cert, denied, 364 U.S. 933.

After observing that there is a “lack of complete clarity

as to whether the Constitution requires only an abolition

of compulsory segregation based on race or something-

more” (287a), the district court chose to adhere to that

well known dictum which originated in Briggs v. Elliott,

132 F. Supp. 776, 777 (E.D.S.C. 1955).7 It concluded

“that the Constitution does not require integration and

that it only requires the abolition of compulsory segrega

tion based on race” (292a). This view of what is required

0 Appellant refers to the Board’s attempt to resegregate Negro pupils,

see p. 4, supra.

6 The district court held that the Superintendent’s action in denying Ne

groes minority transfers was in direct violation of the court’s decrees and

awarded plaintiffs attorneys fees in this aspect of the litigation (308a).

7 “ The Constitution in other words does not require integration. It merely

forbids discrimination.”

17

pervades Judge Brown’s opinion and formed the basis for

his rejection of appellants’ feeder system proposal (297a,

300a) and their contention that the Constitution requires

school systems to integrate (288a, 292a),

The United States Supreme Court has indicated in a

number of recent opinions that the requirements for “good

faith compliance at the earliest practicable date” and “all

deliberate speed” announced in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 349 U.S. 294, 300, 301, must now be viewed in an

altered contest when interpreting and applying the lan

guage in plans for desegregation. Goss v. Board of Edu

cation, 373 U.S. 683, 689; Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U.S.

263, 264-65; see Bradley v. School Board of Richmond,

382 U.S. 103; Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198. Compare

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526. These Supreme

Court authorities make it clear that in this day and time

school boards must adopt desegregation plans which truly

accommodate the process of integration in public schools.

The Fifth Circuit which formerly adhered to the Briggs

standard; Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43, 48 (5th Cir. 1960) ;

Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent School District, 241

F.2d 230, 233 (5th Cir. 1957), has abandoned that posi

tion. In Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965), the court indicated

that the Briggs dictum, “ should be laid to rest” and that

“ . . . the second Brown opinion clearly imposes on public

school authorities the duty to provide an integrated school

system.” 348 F.2d at 730. The Eighth Circuit seems to be

in accord. Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 21 (8th Cir. 1965).

In fact, the Briggs statement8 was Obiter Dicta. This

was the opinion of a three-judge court issued promptly

Note 7, supra.

18

on remand following the Supreme Court’s reversal of its

decision of upholding compulsory segregation. It was is

sued in a totally abstract context apparently before coun

sel even argued the case.9 Because of confusion of defini

tions of “integration” and “ segregation” the Briggs dictum

is meaningless. In the past it has been used in support

of all sorts of now discredited schemes to maintain segre

gation. Cf., Goss v. Board of Education, 301 F.2d 164

(6th Cir. 1962), reversed, 373 U.S. 683; Kelley v. Board of

Education of Nashville, 270 F.2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959).

The district court reached the conclusion that “ ‘honestly’

drawn zone lines which, result in de facto segregation do

not deprive plaintiff of any constitutional rights” (295a).

This statement makes it apparent that the court viewed

the issue as similar to the problem of racial imbalance in

the North rather than considering it in the context of the

Southern problem, i.e., this disestablishment of state

created patterns of discrimination.10

Appellants submit that the Briggs’ view, which this Court

seems to have approved in Kelley v. Board of Education

of Nashville, 270 F.2d 209, 226 (6th Cir. 1959), should be

reexamined and rejected in light of more recent, contrary,

pronouncements of the United States Supreme Court and

other appellate courts. The Kelley type plan was in

validated by Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683.

The burden to desegregate and to justify any delay

is with the Board and the Board has at its disposal the

9 “ This cause coming on to be heard on the motion of plaintiffs for a

judgment and decree in accordance with the mandate of the Supreme Court,

and the Court having carefully considered the decision of the Supreme

Court, the arguments of counsel and the record heretofore made in this

cause . . . ” Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776, 778 (E.D.S.C. 1955).

10 For comparison of the problems see Fiss, Racial Imbalance in the

Public Schools: The Constitutional Concepts, 78 Harv. L. Eev. 564 (1965).

19

skills, personnel and necessary information to devise trans

fer and zoning policies necessary to conform to both con

stitutional standards and educationally sound policies.

Appellee in desegregating its school system should note

and follow the standard of responsibility set by the United

States Office of Education: “It is the responsibility of a

school system to adopt and implement a desegregation

plan which will eliminate the dual school system and all

other forms of discrimination as expeditiously as possible”

(emphasis supplied).11

Appellants’ experts have suggested the use of a feeder

system, the use of which would result in certain elementary

schools feeding particular junior high schools (207a). The

board has offered no testimony indicating that such a sys

tem is not feasible, practical, educationally sound, and the

most efficient and expedient device for achieving meaning

ful desegregation in the Jackson system. Appellants do

not, however, here intend to suggest any specific formula

tion for zoning and transfer plans. But if the Board does

not wish to take advantage of the feeder system in ful

filling its obligation to Negro school children, then what

ever alternative system it chooses to adopt, must meet

presently accepted requirements and lead to meaningful

public school desegreg'ation.

11 Supra note 4, $181.11.

20

II.

A “ Freedom of Choice” Faculty Desegregation Plan Is

Tantamount to No Plan At All, and Falls Far Short of

Vindicating the Right of Negro Children to An Educa

tion Free From Any Consideration of Race as Guaranteed

By the Fourteenth Amendment to The Constitution of

The United States.

The “freedom of choice” faculty desegregation plan

approved below is fraught with evil and incapable of

meeting recent standards set by the Supreme Court of

the United States. Bradley v. School Board of Richmond,

382 U.S. 103 ;12 Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198. In the Brad

ley and Gilliam13 cases, Negro petitioners sought certiorari

from decisions approving the refusal to hold full evi

dentiary hearings on the continued assignment of faculties

on the basis of race. The Supreme Court held that Ne

groes are entitled to a full evidentiary hearing without

delay on their contention that faculty segregation delays

the process of desegregation:

Each plan had been in operation for at least one

academic year; these suits had been pending for sev

eral years; and more than a decade has passed since

we directed desegregation of public school facilities

“with all deliberate speed,” Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 349 U.S. 294, 301. Delays in desegregating school

systems are no longer tolerable. Goss v. Board of

Education, 373 U.S. 683, 689; Calhoun v. Latimer,

377 U.S. 263, 264-65; see Watson v. City of Memphis,

373 U.S. 526. (382 U.S. at 105)

. . .12 Decided together with Gilliam v. School Board of Hopewell, also on

petition for certiorari to the same Court.

13 See Note 12 above.

21

The ‘ ‘freedom of choice” plan adopted by the district

court cannot stand in the face of the admonition in the

above quoted language for the plan will effectively post

pone desegregation indefinitely. Moreover, such a plan

erroneously places the burden of faculty desegregation on

teachers, while the task is clearly the responsibility of

the Board.

A free choice program for teachers, viewed in the

context of the history of discrimination in Jackson, is a

totally ineffective device for accomplishing* desegregation.

One can hardly expect a Negro teacher in this hostile

atmosphere to exercise a choice to teach in heretofore

all-white schools when Negro teachers throughout the

South are being discharged as school desegregation reaches

their communities.14 It is sheer folly to expect Negro

teachers to exercise such a choice in the face of these

potentially disastrous economic and social consequences,

where the local school board is opposing faculty deseg

regation in court on the ground “ that the destruction of

the entire City School System is seeded in this request . . .”

(42a). Cases involving dismissals of Negro teachers are

now pending in federal courts at every level as a result

of the actions of school boards in North Carolina, South

Carolina, Mississippi and Texas. See Franklin v. County

14 The National Education Association has sponsored a detailed study of

the problem. See “ Report of Task Force Appointed to Study the Problem

of Displaced School Personnel Related to School Desegregation and the

Employment Studies of Recently Prepared Negro College Graduates Cer

tified to Teach in 17 States” , December, 1965. See also, Ozmon, “ The Plight

of the Negro Teacher” , The American School Board Journal, pp. 13-14,

September, 1965. The problem was recognized in Brown v. County School

Board of Frederick County, Va., 245 F. Supp. 549, 560 (W.D. Va. 1965). “ I

cannot ignore the fact that those who have suffered the greatest hardships

as a result of school integration have been the Negro teachers whose jobs

have been lost in the backwash created by the closing of Negro schools.”

2 2

School Board of Giles County, No. 10,214, 4th Cir., April 6,

1966.

Only recently in Kier v. County School Board of Au

gusta County, Virginia, 249 F. Snpp. 239, 248 (W.D. Va.

1966), Judge Michie found free choice plans for teachers

unacceptable:

The duty of assigning teachers and administrative

staff to the various schools in the system rests squarely

upon the shoulders of the school authorities. Unlike

the pupil situation, there can he no “ freedom of choice”

plan for teachers and staff assignments. The duty

must be squarely and immediately met.

The district court found the appellants’ proof made it

“ obvious that defendants have followed a policy of as

signing white teachers, simply because of their race, only

to schools in which pupils are all or predominantly white,

and of assigning Negro teachers, simply because of their

race, only to schools in which pupils are Negroes” (305a).

Nevertheless, the court felt that appellants’ proof was not

“ sufficiently strong to entitle them to an order requiring

integration of faculties and principals” (305a). Appellants

contend that where the existence of segregated faculties

is shown, it is unnecessary to prove the actual adverse

effects on Negro children. This is implicit in the Supreme

Court’s statement in Bradley v. School Board of Richmond,

382 U.S. 103, 105: “ There is no merit to the suggestion

that the relation between faculty allocation on an alleged

racial basis and the adequacy of desegregation plans is

entirely speculative.” See K ier v. County School Board

of Augusta County, Virginia, 249 F. Supp. 239, 246 (W.D.

Ya. 1966); Thompson v. County School Board of Hanover

County, Virginia, Civ. No. 4274, E.D. Va., January 27,

23

1966. This Court has recognized the right of pupils to

desegregated faculties. Thus, in Mapp v. Board of Educa

tion of Chattanooga, 319 F.2d 571, 576 (6th Cir. 1963),

stricken allegations concerning desegregation of faculties

were ordered to be restored to the complaint.

Assuming that proof of ill effects is required, appellants

submit that such proof is clear in the record (201a-202a,

223a~224a, 231a-232a, 238a-239a) and the district court erred

in holding to the contrary.

In the Jackson system 120 Negro pupils have success

fully enrolled in formerly all-white schools, but not a single

white student is enrolled in a Negro school (280a-285a).

This is but another indication of the trend toward one-way

desegregation; i.e., Negro pupils leaving their all-Negro

schools with all-Negro faculties and student bodies intact.15

It is obvious that if this pattern is continued without cor

responding integration of Negro faculty personnel, not

only will meaningful pupil desegregation become impos

sible, but Negro teachers will be gradually siphoned out

of the system, and plaintiffs’ efforts to achieve faculty

desegregation will no longer be difficult, but impossible.

Faculty segregation impedes the progress of pupil

desegregation. Where, as here, students and parents are

given a choice of schools by exercising rights granted

under defendants’ open transfer plan, faculty segregation

influences a racially based choice. Arrangements which

work to promote segregation and hamper desegregation

are not to be tolerated in desegregation plans. Goss v.

Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683. Faculty segregation

influences a racially based choice as surely as the law

15 See comprehensive statistics published by the Southern Education Re

porting Service in its periodic “ Statistical Summary of School Segregation-

Desegregation in Southern and Border States” , loth Revision, December

1965, passim.

24

requiring racial designations on ballots which was in

validated in Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399.

The United States Office of Education has noted the

negative consequences of pupil desegregation without con

current faculty desegregation. Thus, in further implement

ing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.A.

2000d) the Office of Education in its March, 1966 Revised

Statement of Policies16 requires school districts submitting

plans for desegregation to comply with the following

policies:

§181.13 Faculty and Staff

(a) Desegregation of Staff. The racial composition

of the professional staff of a school system, and of

the schools in the system, must be considered in de

termining whether students are subjected to discrim

ination in educational programs. Each school system

is responsible for correcting the effects of all past

discriminatory practices in the assignment of teachers

and other professional staff.

(b) New Assignments. Race, color, or national origin

may not be a factor in the hiring or assignment to

schools or within schools of teachers and other pro

fessional staff, including student teachers and staff

serving two or more schools, except to correct the

effects of past discriminatory assignments.

* * # # *

(d) Past Assignments. The pattern of assignment

of teachers and other professional staff among the

various schools of a system may not be such that

schools are identifiable as intended for students of a

particular race, color, or national origin, or such that

16 Supra, Note 4.

25

teachers or other professional staff of a particular

race are concentrated in those schools where all, or

the majority, of the students are of that race. Each

school system has a positive duty to make staff as

signments and reassignments necessary to eliminate

past discriminatory assignment patterns. Staff deseg

regation for the 1966-67 school year must include

significant progress beyond what was accomplished

for the 1965-66 school year in the desegregation of

teachers assigned to schools on a regular full-time

basis. Patterns of staff assignment to initiate staff

desegregation might include, for example: (1) Some

desegregation of professional staff in each school in

the system, (2) the assignment of a significant portion

of the professional staff of each race to particular

schools in the system where their race is a minority

and where special staff training programs are estab

lished to help with the process of staff desegregation,

(3) the assignment of a significant portion of the

staff on a desegregated basis to those schools in which

the student body is desegregated, (4) the reassignment

of the staff of schools being closed to other schools

in the system where their race is a minority, or (5)

an alternative pattern of assignment which will make

comparable progress in bringing about staff desegrega

tion successfully.

These Office of Education standards for faculty deseg

regation are not binding on the courts. They are, however,

entitled to great weight. See Singleton v. Jackson Munic

ipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729, 731 (5th Cir.

1965); Price v. Denison Independent School District Board

of Education, 348 F.2d 1010, 1013 (5th Cir. 1965); Kemp

v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 18-19 (8th Cir. 1965). Significantly,

26

at least two district courts had fashioned orders before

the Office of Education adopted its Revised Statement

which complement the new regulations. Dowell v. School

Board of Oklahoma City Public Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971,

977-8 (W.D. Okla. 1965) (appeal pending), and Kier v.

County School Board of Augusta County, Virginia, 249

F. Supp. 239, 247 (W.D. Va. 1966), both require plans

under which the percentage of Negro teachers assigned

to each school would result in an equal distribution of

Negro teachers throughout the system. This or similar

relief is necessary to eliminate the problem of faculty

segregation in Jackson, Tennessee. The Board should be

required to submit an administrative plan for faculty

desegregation in accord with such definitive guidelines.

III.

School Board Participation In and Support For Pro

grams Which Discriminate On the Basis of Race Is

Prohibited By The Fourteenth Amendment to The Con

stitution of The United States.

The Board has two policies which appellants specifically

objected to in the court below. One is the practice of

closing schools so that public school teachers may have a

holiday to attend segregated teacher in-service training

programs (63a-64a). The other is the practice of allowing

the Jackson Symphony Association to hold segregated con

certs on school premises, during school hours, with au

diences composed of pupils from formerly all-white city

schools, county schools and Catholic schools (271a). Negro

pupils in Negro schools were completely excluded from

these concerts (271a). Obviously neither of these activities

would be possible without School Board cooperation.

The district court erroneously viewed the issue raised by

segregated teacher in-service training as one of who has

control of teacher organizations and concluded that the

Board does not (306a-307a). This conclusion was reached

in spite of the Board’s admission in its pleadings that

teacher in-service training was included in yearly school

board planning (68a, 76a).

The same is true regarding the district court’s finding

that symphony concerts are “ outside activity” (306a). It

is submitted that the question which should have been

posed regarding these activities is whether the Board, may,

under the circumstances, cooperate with and support or

ganizations which practice discrimination based on race.

Contrary to the district court’s holding (307a) Negro

pupils are directly affected by segregated teacher in-ser

vice training. The first Brown case held that a segregated

education was inherently unequal. What could be more

closely connected with the education of pupils than the

continuing education received by their teachers on a racial

basis? The court’s conclusion that “ segregation in teacher

in-service training has no effect on their right as pupils”

(307a) is clearly inconsistent with McLaurin v. Oklahoma,

339 U.S. 637. There a Negro had been admitted to a State

university for graduate instruction in education. Solely

because of his race, he was required to occupy a seat in

a row in the classroom reserved for colored students and

had special tables in the library and cafeteria. No white

student received this kind of treatment. The Supreme

Court said (339 U.S. 637, 641):

The result is that appellant is handicapped in his

pursuit of effective graduate instruction. Such re

strictions impair and inhibit his ability to study, to

engage in discussions and exchange views with other

28

students, and, in general, to learn Ms profession.

# * * Those who will come under his guidance and

influence must he directly affected by the education

he receives. Their own education and development will

necessarily suffer to the extent that his training is

unequal to that of his classmates. (Emphasis sup

plied.)

Official action, regardless of the form it takes, is subject

to constitutional limitations when it supports racial dis

crimination. See, Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U.S. 715; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 4. The

Supreme Court’s most recent pronouncement in the State

action area, Evans v. N ew ton,------ U.S. ------- , 15 L.ed. 2d

(No. 5) 373, 377; pointed out that:

Conduct that is formally ‘private’ may become so

entwined with governmental policies or so impregnated

with a governmental character as to become subject

to the constitutional limitations placed upon state ac

tion.

The Court went on to assume arguendo that “no constitu

tional difficulty would be encountered” if the conduct in

question “ in no way implicated the State. . . .” 15 L.ed.

2d at 377-78. (Emphasis supplied.) In Muir v. Louisville

Park Theatrical Ass’n., 202 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1953) this

court held that a private theatrical association’s policy

of refusing* Negroes admission to operatic performances,

held on property owned by the City and leased to the As

sociation, did not amount to unlawful discrimination in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. On certiorari,

the Supreme Court vacated and remanded the judgment

in light of Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483,

and prevailing conditions. 347 U.S. 971. More recently

29

racially discriminatory conduct has been prohibited when

the State participates “ through any arrangement, manage

ment, funds or property,” Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 4,

19 and when the State places its “power, property or

prestige” behind the discrimination. Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 725; see, Hawkins v.

North Carolina Dental Society, 355 F.2d 718 (4th Cir. 1966).

The above cited authorities make it perfectly clear that

the Jackson Symphony Orchestra may not hold segregated

performances on school premises and the Board may not

adopt the segregationist policy of the symphony associa

tion. The district court therefore erred in failing to con

demn this practice and in refusing to order the Board not

to permit segregated performances in the future.

It is also clear that the Board cannot acquiece to policies

which perpetuate faculty segregation and hence pupil seg

regation. Governmental arrangements with “private” per

sons which encourage segregation and hamper desegrega

tion have been condemned. Goss v. Board of Education,

373 U.S. 683. The district court’s refusal to enjoin the

Board from future participation in segregated teacher in-

service training programs was also error.

Relief

For the foregoing reasons, appellants respectfully sub

mit that the judgment of the court below should be re

versed and the cause should be remanded with directions

to the trial court to require the Board to present a new

plan of desegregation, said plan to take effect not later

than the next school term following this court’s order and

to include:

1. Revision of present junior high school zone lines

which impede desegregation and elimination of policies

30

which permit transfer to obtain a segregated educa

tion. Transfer provisions which will permit pupils as

signed to segregated schools to obtain transfer to

desegregated schools should also be included;

2. Provisions for the assignment of all teachers and

other faculty personnel in accordance with qualifica

tion and need without regard to race.

The district court should be directed to issue an order

enjoining the Board from giving any further support in

any form to any “private” group or organization which

practices discrimination based on race.

In addition, an express duty should be imposed on the

Board to integrate the school system, said duty to be car

ried out by the adoption and implementation of educa

tionally sound procedures and practices which the Board

may reasonably undertake.

Bespectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. B abbit , III

M ic h ael M eltsner

G erald A . S m it h

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N . W illiam s , J r .

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 218