Thomason v. Cooper Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thomason v. Cooper Brief for Appellees, 1957. bc60ad0a-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ac93abce-8882-4787-8766-651c606db560/thomason-v-cooper-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

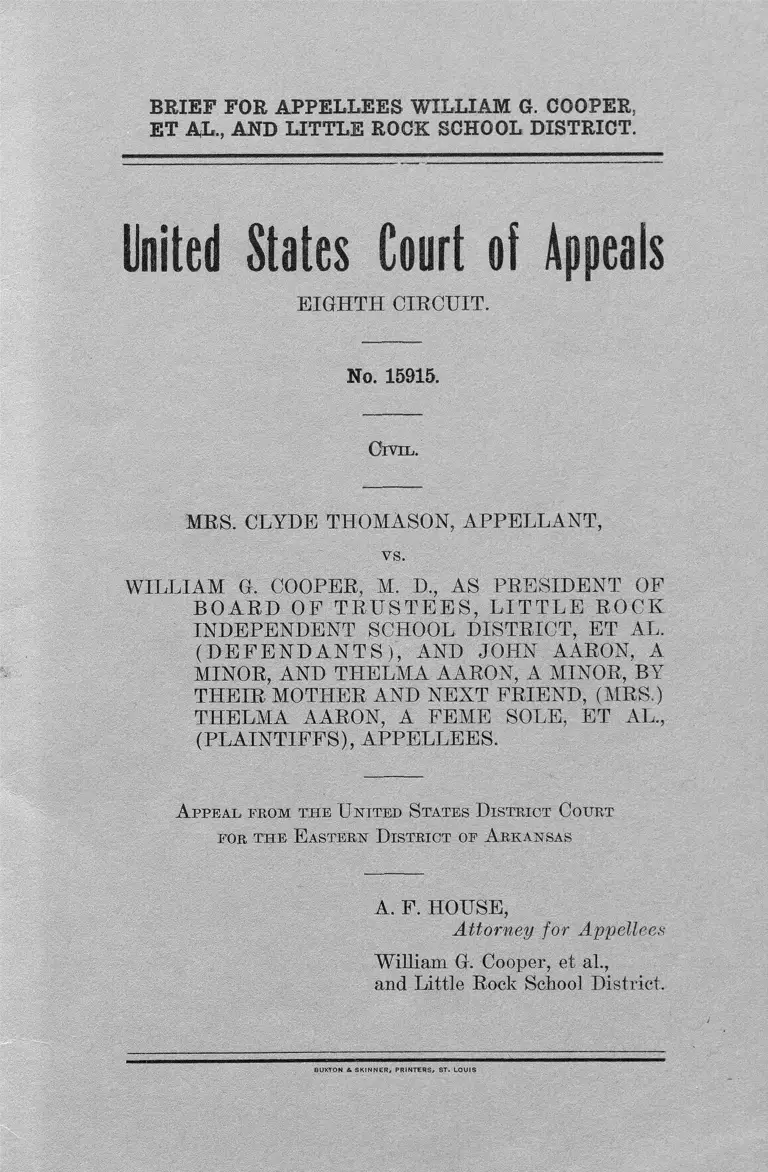

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES WILLIAM G. COOPER,

ET AL., AND LITTLE ROCK SCHOOL DISTRICT.

United States Court of Appeals

EIGHTH CIRCUIT.

No. 15915.

Q rm ,.

MRS. CLYDE THOMASON, APPELLANT,

vs.

WILLIAM G. COOPER, M. D., AS PRESIDENT OF

B O A R D OF T R U S T E E S , L I T T L E R O C K

INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL.

( D E F E N D A N T S ) , AND JOHN AARON, A

MINOR, AND THELMA AARON, A MINOR, BY

THEIR MOTHER AND NEXT FRIEND, (MRS.)

THELMA AARON, A FEME SOLE, ET AL.,

(PLAIN TIFFS), APPELLEES.

A p p e a l fr o m t h e U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C ourt

for t h e E aste rn D istr ic t of A r k an sa s

A. F. HOUSE,

Attorney for Appellees

William G. Cooper, el al.,

and Little Rock School District.

BUXTON & SKINNER, PRINTERS, ST. LOUIS

INDEX.

Page

Statement of the C ase .......................... 1

Argument..................................................................................................... 4

Conclusion ................................................................................................... 7

Table of Cases:

Capella v. Zurich General Accident & Liability Insurance Co.,

194 F. (2d) 558 .................................................................................... 6

Fort Worth & D. Railway Co. v. Harris, 230 F. (2d) 680 ................. 6

Other Authority:

Rule 46, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure....................................... 6

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT.

No. 15915.

MRS. CLYDE THOMASON, APPELLANT,

vs.

WILLIAM G. COOPER, M. D., AS PRESIDENT OF

B O A R D OF T R U S T E E S , L I T T L E R O C K

INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL.

( D E F E N D A N T S ) , AND JOHN AARON, A

MINOR, AND THELMA AARON, A MINOR, BY

THEIR MOTHER AND NEXT FRIEND, (AIRS.)

THELMA AARON, A FEAfE SOLE, ET AL,,

(PLAIN TIFF), APPELLEES.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES. WILLIAM G. COOPER,

ET AL., AND LITTLE ROCK SCHOOL DISTRICT.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

We have here not a preliminary injunction but a perma-

ment injunction, and that part of Rule 65, Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure, relied on by appellant is not applicable.

The schools operated by appellee Little Rock School

District, hereinafter referred to as ‘ ‘ District, ’ ’ were to

[ 2 ]

open on September 3, 1957. Instead of intervening in the

United States District Court, hereinafter referred to as

“ District C ourt/’ to show cause why operations under the

plan of integration approved by the District Court on Au

gust 15, 1956, should be. postponed, the appellant filed suit

on August 27, 1957, in the Chancery Court of Pulaski Coun

ty, a court of the State of Arkansas hereinafter referred to

as the “ Chancery Court.”

Under State court procedural rules the District would

have been entitled to a reasonable time in which to plead

and prepare for a hearing. Counsel for appellant and coun

sel for the District realized that they must move rapidly if

the question involved were to be finally settled before the

opening of schools on September 3rd. Counsel for the Dis

trict realized that if the Chancery Court decree interfered

with the operation of the plan as approved by the District

Court it would be required to go to the District Court for

injunctive relief. In view of the existing emergency, coun

sel for appellant and counsel for the District agreed that

the District would immediately file its Answer and be ready

for a hearing in the Chancery Court on September 29, 1957,

and that if the Chancery Court did enter an order forbid

ding operations under the plan, and if the District deemed

it advisable to go to the District Court for relief, counsel

for appellant would waive all formalities and appear before

the District Court for a hearing on the District’s petition

to enjoin appellant from endeavoring to enforce the Chan

cery Court order.

On August 28th the District filed its Answer and on the

29th there was a trial in the Chancery Court. On that date

an order was entered by the Chancery Court forbidding

integration of the races in the schools of the District. On

the afternoon of the 29th the District applied to the District

Court for a permanent injunction (R. 7) and asked for a

hearing on August 30th.

Inasmuch as under the agreement of counsel all proce

dural formalities were to be waived, it was not contempla

ted that a summons would be issued. However, it was

[ 3 ]

deemed proper to enter an order fixing the time of the

hearing in the District Court. The Order (R. 16-17) uses

the phrase “ temporarily enjoined.” This is the only sug

gestion in the record of an application for a temporary

order. The Petition asked for a permanent order (R. 5)

and the order which was entered was of a permanent na

ture (R. 17-18). The Court of its own motion suggested the

provision that the petitioner would not be required to file a

bond (R. 18), but that did not change the nature of the pro

ceeding. It only emphasized the fact that there was per

manency in the restraint placed on appellant.

After the order of August 29th was entered, counsel for

appellant, in keeping with the agreement to dispense with

procedural delays, waived official service on the appellant,

and on the day fixed for the hearing both appellant and her

counsel were before the Court, On September 17, 1957,

appellant filed her Notice of Appeal. It recites that the

appeal is from the final order dated August 30, 1957, “ issu

ing an injunction against her. ’ ’ It is significant that it was

not termed a temporary injunction. It should be added that

the agreement herein discussed was made with Arthur

Frankel who filed the Complaint in the Chancery Court.

Counsel who appears here for appellant first came into

the proceeding on August 29th, but later he was informed

of the agreement and courteously waived service of a copy

of the order of August 29th and appeared on August 30th.

[ 4 ]

ARGUMENT.

As stated, the hearing on the Petition which asks for a

permanent injunction was held on August 30, 1957. Coun

sel for appellees Aaron, et ah, the plaintiffs in the original

suit, was present. He also had waived service of a copy of

the order of August 29th. Appellant and her counsel were

present. Counsel for appellant took no exception to the

order fixing the date of hearing. He took no exception to

the Petition, and he did not ask for an opportunity to pre

sent testimony. He realized that within the confines of the

original order of the District Court and the Complaint and

the Answer filed in the Chancery Court, and the Decree of

the Chancery Court, the solution to the only question pre

sented would be found. As background material for consid

eration by the District Court, counsel for appellant sum

marized the testimony in the Chancery Court and argued at

length that non-acceptance of the plan by residents of the

District and the possibility of danger were sufficient to jus

tify the Chancery Court’s decree. A stenographic tran

script of his argument was taken by the official reporter of

the District Court. Counsel did not question the accuracy

of the exhibits attached to the Petition (R. 11-13). As a

matter of fact, Exhibit “ C ” was prepared by counsel for

appellant and he knew that Exhibit “ B ” was a true copy

of the Answer filed by the District in the Chancery Court

and that Exhibit “ A ” was a true copy of the Complaint

filed by Mr. Frankel in behalf of the appellant.

Only a question of law was presented to the District

Court, to-wit, whether it was proper for a State court to

interfere with the operation of the plan of integration which

was to be put into effect in accordance with the order of the

District Court, such court having retained jurisdiction of

the original suit. No question was involved as to the sover

eign power of a State, acting through its chief executive, to

take measures to preserve the peace. The question was

whether a State court could order the District to disobey

the order of the Federal Court. The impropriety of enjoin

ing the District from doing what it had been ordered to do

by the District Court was manifest, and it was a plain viola

tion of the rule of comity and in disregard of the suprem

acy clause of the Federal Constitution. To avoid repetition,

we adopt and cite in support of the foregoing proposition

the cases cited in Subdivision I of the Brief for Appellees,

Aaron, et al.

The appellant is in no position to argue here that there

was “ no adequate presentation of the facts.” There was

full opportunity to present any facts appellant deemed

material, but that opportunity was deliberately waived.

Counsel well knew that no conceivable testimony from wit

nesses could affect the application of the rule of law which

the District and Aaron et al contended was controlling. He

well knew the exhibits attached to the Petition presented

the one and only issue in the contest, to-wit, whether the

Chancery Court had imposed upon the District a command

in direct conflict with the command imposed by the District

Court’s order of August 15,1956.

The Judge of the District Court did not act precipitantly,

He heard all counsel had to say. He saw in the exhibits an

undermining of the principle of federal supremacy, and he

acted accordingly. The appellant did not even see fit to file

a response to the Petition. The only point he could have

stated in a response was implicitly raised in the exhibits

which were attached to the Petition, and that was one of

law and not fact. In the decree which was entered in the

Chancery Court and which was prepared by counsel for

appellant, he endeavored to put into words the idea that a

State court, in the exercise of State sovereignty, can impair

a Federal Court order on the premise that it is necessary to

do so to preserve the peace. The allegations in the Com

plaint filed in the State court reveal that the idea of State

sovereignty being exercised by a trial court was in a meas

ure extracted from a constitutional amendment and certain

State statutes which were designed to “ prevent federal en

[ 6 ]

croachment on the operation of public schools in Arkan

sas” (R. 9). The appellant speaks too late. Having been

given every opportunity to offer proof and except to pro

cedural orders, she was willing to rest her case on the

exhibits to the Petition and her counsel’s oral argument.

Under Rule 46 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, for

mal exception to rulings and orders of the court are unnec

essary, but no litigant will be heard on appeal who has not

made known to the trial court the action he desires the trial

court to take. Without timely objections and an opportu

nity to make corrections, a trial court may not be put in

error. Capella v. Zurich General Accident & Liability Insur

ance Co., 194 F.(2d) 558; Ft. Worth & D. Railway Co. v.

Harris, 230 F. (2d) 680.

Were this case to be remanded, it would again be submit

ted on the Petition and its exhibits, and testimony from in

numerable witnesses as to why the Chancery Court entered

its decree of August 29th could not possibly change the re

sult.

[ 7 ]

CONCLUSION.

Affirmance is proper.

Respectfully submitted,

A. F. HOUSE,

Attorney for Appellees

William G. Cooper, et al.,

and Little Rock School District.