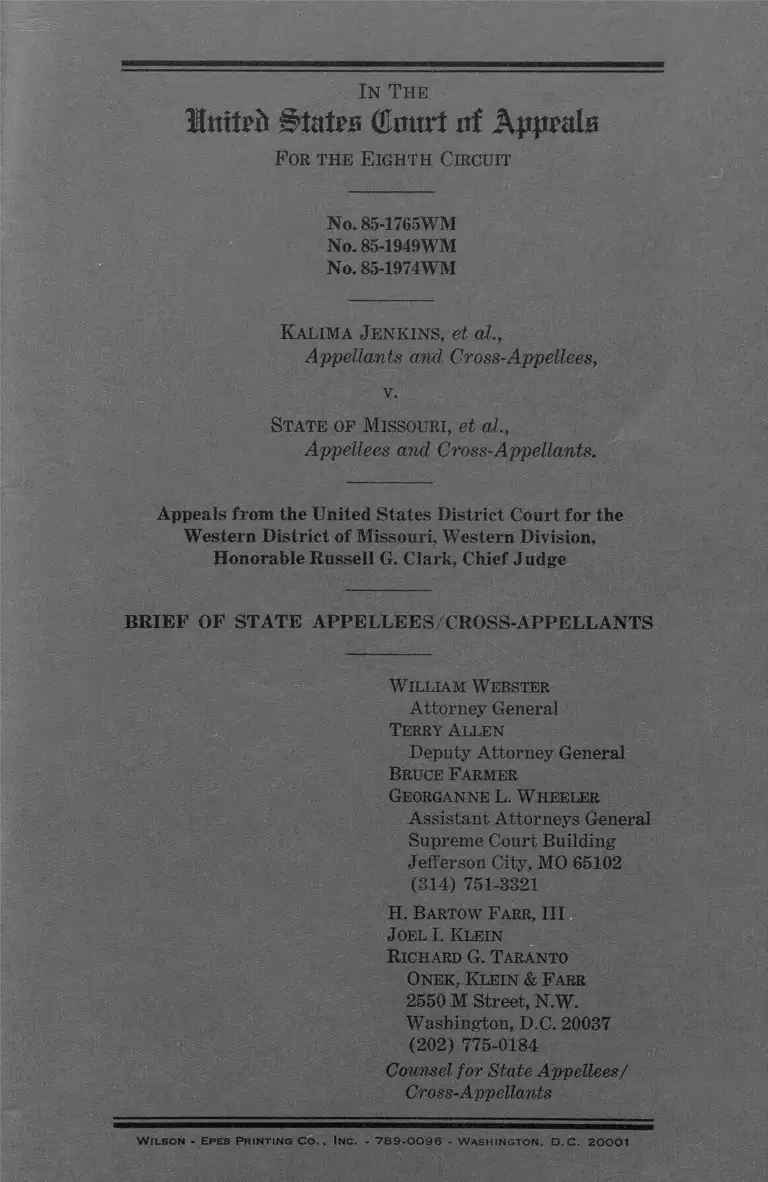

Jenkins v. Missouri Brief of State Appellees/Cross-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jenkins v. Missouri Brief of State Appellees/Cross-Appellants, 1985. e00db5bf-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/acdfa15a-ba77-43ea-b2b7-159f6d3f5e3e/jenkins-v-missouri-brief-of-state-appelleescross-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In The

Imtpfc Glourt of AppmlB

For the E ighth Circuit

No. 85-1765WM

No. 85-1949WM

No. 85-1974WM

Kalima Jenkins, et a l ,

Appellants and Cross-Appellees,

v.

State of Missouri, et al.,

Appellees and Cross-Appellants.

Appeals from the U nited S ta tes D istrict Court fo r the

W estern D istrict of M issouri, W estern Division,

Honorable Russell G. C lark, Chief Judge

BRIEF OF STATE APPELLEES CROSS-APPELLANTS

W illiam Webster

A ttorney General

Terry Allen

Deputy A ttorney General

Bruce Farmer

Georganne L. Wheeler

A ssistant A ttorneys General

Supreme Court Building

Jefferson City, MO 85102

(814) 751-3321

H. Bartow Farr, III

J oel I. Klein

Richard G. Taranto

Oner , Klein & B’arr

2550 M Street, N.W.

W ashington, D.C. 20037

(202) 775-0184

Counsel fo r S ta te Appellees/

Cross-Appellants

W il s o n - E p e s P r in t in g C o . . In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n . D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

SUMMARY AND REQ U EST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

T his desegregation case involves both in te rd is tr ic t and

in tra d is tr ic t claim s, m ade by both the p lain tiffs and the

K ansas C ity M issouri School D is tr ic t (K CM SD ) a g a in s t

various S ta te agencies and officials, v arious federa l agen

cies, and v a rious school d is tr ic ts in the K ansas C ity

m etropo litan a rea . A f te r y e a rs of discovery and m onths

of tr ia l, th e d is tr ic t cou rt rejected the in te rd is tr ic t claim s,

m ak ing extensive findings abou t th e lack of any signifi

ca n t c u rre n t seg rega tive effect re su ltin g fro m th e alleged

d isc rim in a to ry acts. T he co u rt accepted the in tra d is tr ic t

claim s, how ever, find ing th a t vestiges of the fo rm e r dual

school system rem ained w ith in the KCM SD itself. In the

c o u rt’s view, th is find ing ju stified a rem edy fo r all s tu

den ts and all schools th ro u g h o u t th e KCM SD.

The co u rt’s rejection of th e in te rd is tr ic t claim s is cor

rec t u n d e r the govern ing law established by M illiken v.

B radley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974 ), and is overw helm ingly

supported by the c o u rt’s findings. T he c o u rt’s decision to

im pose a d istric t-w ide rem edy, by co n tra s t, is unsu p

po rted by adequate findings. In add ition , the rem edy

adopted by the d is tr ic t cou rt is u n ju stified in a num ber

of p a r t ic u la r respects.

The S ta te defendan ts request the sam e am oun t of tim e

fo r o ral a rg u m e n t as th a t g ran ted to the KCM SD or

p lain tiffs. T he S ta te defendan ts believe th a t 40 m inu tes

is a sufficient period.

(i)

Page

SUMMARY AND REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGU

M ENT ................................ ................ ..................................... i

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES ................. ........ ...... ........ . v

PRELIM IN A RY STA TEM EN T....................................... xi

STATEM ENT OF TH E ISSUES _________ ____ ______ xii

STATEM ENT OF TH E C A SE .............................. ........... 1

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGU

M ENT ................................................................. ....... ........ ....... 7

ARGUM ENT ............................................................ ............ . 8

I. The D istrict Court Properly Found A gainst

Plaintiffs and the KCMSD on Their Claims of

In te rd is tric t L iab ility_________ 8

A. The Law Governing In te rd is tric t Claims Re

quires Proof of Intentionally D iscrim inatory

Acts and A Significant C urren t Condition of

Segregation Resulting From Those A c ts____ 8

B. The D istrict Court Correctly Found T hat

School Boundaries In the Kansas City M etro

politan A rea W ere Not Set or M aintained

W ith a D iscrim inatory Purpose .......... .......... 12

C. The D istrict Court Correctly Found th a t No

Racially D iscrim inatory Act of the S tate

Was a Substantial Cause of Significant Cur

ren t In te rd is tric t Segregation _______ _____ 14

1. Pre-1954 S tate School Policies ................ 15

2. Post-1954 School-Related A c tio n s______ 22

3. Housing Actions ........ ................................. . 26

D. The D istrict Court’s Findings Dispose of the

In te rd istric t Claims A gainst the State De

fendants ....... 29

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(iii)

IV

II. The D istric t Court Adopted an Im proper Rem

edy fo r the In trad is tric t Violation ......................... 40

A. The D istrict Court, in Developing a Remedy

for Segregation W ithin the KCMSD, Failed

to L im it the Remedy to Redress of the Con

ditions Caused by T hat S eg rega tion ........... 40

1. The F inding of Segregation in the 90+ %

Black Schools __________ ________ ___ __ 42

2. The F inding of Indigenous Inferiority.... 47

B. The D istrict Court Committed Several E r

ro rs W ith Regard to P articu la r Program s.... 53

1. The V oluntary In te rd is tric t Program .... 54

2. The General Addition of T eachers ........... 55

3. The School G rant P ro g ra m _________ __ 55

4. The Buildings Plan ........................ .............. 56

5. The Allocation of Funding Between the

S tate and the KCMSD _________________ 5g

CONCLUSION .................................................... ......... 63

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

C A SE S Page

Adam s v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277 (8th C ir.),

cert, denied, 449 U.S. 826 (1980).......................... 15, 43

Alabama V. Pugh, 438 U.S. 781 (1978)__________ xii, 60

Alexander V. Youngstown Board o f Education,

675 F.2d 787 (6th Cir. 1982)..... .......... ......... ......... 42

Anderson v. C ity o f Bessemer City, N.C., 105

S.Ct. 1504 (1985) .... ........... ..................... ................ 30

A rm our v. N ix, No. 16,708 (N.D.Ga. 1979), aff’d,

446 U.S. 930 (1 9 8 0 )______________________ __ 14, 32

Arm strong v. Board of School Directors of the

City of M ilwaukee, 616 F.2d 305 (7th Cir.

1980) ____ ___ __________ ____________ ____ __ _ 42-43

A rth u r v. N yquist, 712 F.2d 809 (2d Cir. 1983),

cert, denied, 104 S.Ct. 1907 (1984)___ ________ 52

Barrows V. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953)________ 27

B erry v. School D istrict of the C ity of Benton

Harbor, 564 F. Supp. 617 (W.D.Mich. 1983).... 13

B erry v. School D istrict of the C ity of Benton

Harbor, 698 F.2d 813 (6th C ir.), cert, denied,

464 U.S. 892 (1 9 8 3 )___________ ___ _________ 13, 57

Bradley V. M illiken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973),

rev’d, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)..... ..................... .......... 11

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 462 F.2d

1058 (4th Cir. 1972), aff’d, 412 U.S. 92 (1973).. 14

Brennan v. A rm strong, 433 U.S. 672 (1977)____ 42

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 483

(1954) ............... passim

Columbus Board of Education V. Penick, 443 U.S.

449 (1979) .......... ......9 ,30,41

Cunningham v. Grayson, 541 F.2d 538 (6th Cir.

1976), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 1074 (1977)........ 14

Davis v. E ast Baton Rouge Parish School Board,

721 F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1983)_________ __ ____ 44

D ayton Board of Education v. Brinkm an, 433 U.S.

406 (1 9 7 7 )__________ 9 ,41 ,57

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974)_____xiii, 60, 61

Evans v. Buchanan, 393 F. Supp. 428 (D.Del.),

aff’d mem., 423 U.S. 963 (1 9 7 5 )________ _____ 11, 13

Evans v. Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750 (3d Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 446 U.S. 923 (1980).............. ............. 13

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

E x Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908)................ ...... 60

Ford M otor Company v. Dept, o f Treasury, 323

U.S. 459 (1945)...................................... .................. 60

General Building Contractors A ss ’n v. Pennsyl

vania, 458 U.S. 375 (1982) ........... ..... ................. 41

Goldsboro City Board of Education v. Wayne

County Board of Education, 745 F.2d 324 (4th

Cir. 1984) ...... .............................................. ........... .13, 30-32

Great N orthern L ife Insurance Co. v. Read, 322

U.S. 47 (1944) .... ................... ...... .................. ......... . 60

Haney v. County Board o f Education, 410 F.2d

920 (8th Cir. 1969) ........................... ......... ........ ,........ 13, 36

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1 9 7 6 )................. passim

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 672

F.2d 1107 (3rd C ir.), cert, denied, 459 U.S.

824 (1982) ________ ______ ______ ____________ 13

Jenkins v. State of Missouri, 593 F. Supp. 1485

(W.D.Mo. 1984) ............................ .............................. .

Keyes v. School D istrict No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) ........... ................................................... .............

Lee V. Lee County Board of Education, 639 F.2d

1243 (5th Cir. 1981).................... ................... ........

Liddell v. Missouri, 731 F.2d 1294 (8th C ir.), cert.

denied, 105 S.Ct. 82 (1984) ..................... ........

M iener v. M issouri, 673 F.2d 969 (8th C ir.), cert.

denied, 459 U.S. 909 (1982) _____ ____________

M illiken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)_________

M illiken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) .

Monell v. D epartm ent of Social Services, 436 U S

658 (1978) ________________ __ _______ ____ _

Moose Lodge No. 107 V. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163 (1972)

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530 F.2d 401 (1st C ir.), cert.

denied, 426 U.S. 935 (1976)

M orrilton School D istrict No. 32 v. United States,

606 F.2d 222 (8th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 444

U.S. 1071 (1 9 8 0 )............. .................

M ount H ealthy City School D istrict v. Doyle 429

U.S. 274 (1 9 7 7 ).... ............................................’

Newburg Area Council, Inc. v. Board o f Education

of Jefferson County, 510 F.2d 1358 (6th Cir.

1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 931 (1975).............

passim

passim

11, 60

passim

passim

22

27

52

13, 39

11

11,13

V ll

Oliver v. Kalamazoo Board of Education, 640 F.2d

782 (6th Cir. 1 9 8 0 ).................................................... 52, 53

Parent Association of A ndrew Jackson H.S. V.

Am back, 598 F.2d 705 (2d Cir. 1979) ................. 57

Pasadena City Board of Education V. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424 (1 9 7 6 )................... .............................. 44

Penick V. Columbus Board of Education, 519 F.

Supp. 925 (S.D. Ohio), aff’d, 663 F.2d 24 (6th

Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 1018 (1982).... 59

Pennhurst S ta te School and Hospital v. Halder-

man, 104 S.Ct. 900 (1984)........................................ 60

Plaquemines Parish School Board v. United

States, 415 F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969).... ................ 53

Pullm an-Standard V. Sw int, 456 U.S. 273 (1982).. 31

Reed v. Rhodes, 500 F. Supp. 404 (N.D. Ohio

1980), aff’d, 662 F.2d 1219 (6th Cir. 1981),

cert, denied, 455 U.S. 1018 (1982)..................... 59

School D istrict of Kansas City, M issouri v. State

of Missouri, 460 F. Supp. 421 (W.D.Mo. 1978)... 2, 38

School D istrict of Omaha v. United States, 433

U.S. 667 (1977) ..______ _________ _________ _ 41-42

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)...................... 27

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971)............. ..............................passim

Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1978),

cert, granted, 440 U.S. 906 (1979), cert, dis

missed, 444 U.S. 437 (1980).................................... 18

Tasby v. Estes, 412 F. Supp. 1185 (N.D.Tex.

1975), aff’d on in terdistrict issues, 572 F.2d

1010 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, granted, 440 U.S.

906 (1979), cert, dismissed, 444 U.S. 437

(1980) .... ...... ..................... ........................................... 14,32

Taylor v. Ouachita Parish School Board, 648 F.2d

959 (5th Cir. 1981) ........... ........ ................... ............ 14

United States v. Board of Education of Valdosta,

Georgia, 576 F.2d 37 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, de

nied, 439 U.S. 1007 (1978).................... ................... 43

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

V ll l

United S ta tes v. Board o f School Commissioners

of the City o f Indianapolis, 456 F. Supp. 183

(S.D.Ind. 1978), aff’d in relevant part, 637 F.2d

1101 (7th Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 838

(1980) ....... ............. ............................. ........................ 11,13

United States v. Jefferson County Board o f E du

cation, 380 F.2d 385 (5th C ir.), cert, denied,

389 U.S. 840 (1967 )........... ................. ..................... 53

United States V. Missouri, 515 F.2d 1365 (8th

C ir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 951 (1975)_______ 13

United States v. Texas, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir.

1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 1016 (1972)........... 53

United States v. Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043 (E.D.

Tex. 1970), aff’d in relevant part, 447 F.2d 441

(5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 1016

(1972) .................................................. .......................... 13

W ashington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ................8, 9, 41

Weiss v. Leaon, 225 S.W.2d 127 (Mo. 1949).............. 27

S T A T U T E S

42U.S.C. § 1982 (1982)_________ _____ __________ 53-54

Act of July 6, 1957, § 1, 1957 Mo. Laws 542-53.... 16

Mo. Const, a rt. 3, § 40 (2 0 )______________________ 10-11

Mo. Const, a rt. IX, § 1 (a) (1 9 4 5 )............................ . 15

1865 Mo. Laws 177, § 20 ..___ ____________________ 17

1869 Mo. Laws 8 6 _________________ 17

1870 Mo. Laws 149, § 45, codified a t Mo. Rev. Stat.

Mo. a rt. 1, ch. 150, § 7052 ______ ______ _____ _ 16-17

1874 Mo. Laws 163-64, § 7 3 ............... ...... ................... 16-17

1887 Mo. Laws 264, codified a t Mo. Rev. Stat.

§§ 8003 & 8004 (1889) ............................................. 16-17

1893 Mo. Laws 247 ___ _____ __ ________________ 16-17

1909 Mo. Laws 790, § 42, codified a t Mo. Rev.

Stat. a rt. 2, ch. 102, §§ 11145 & 11146 (1919).. 16-17

1929 Mo. Laws 382-83, codified a t Mo. Rev. Stat.

ch. 72, § 10350 (1939) _____ ______ ____ ____ i 6_i7

1946 Mo. Laws 1699-1700______________ 16-17

Mo. Rev. Stat. §§ 162.222, 162.431, 162.441 (1978

& Supp. 1983)... ....... ..... ....... ...................................... 10

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

IX

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 165.563 (1943)........ 23

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 99.040 (1978) ........ 26

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 99.300 (1978).................................. 26

Mo. Rev. Stat. §§ 215.100, 213.105, 213.120 (1978).. 53-54

O TH ER A U T H O R IT IE S

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52 ( e ) ............. ..................................... . 30

Executive Order No. 11063........ ................................... 53-54

Effective Schools: A Sum m ary of Research (1983).. 57-58

M urnane, “In terp reting the Evidence on School

Effectiveness,” 83 Harv. Educ. Rev. 19 (1981).. 57-58

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

1. The decisions appealed from by the State cross

appellants were rendered by Chief Judge Russell G. Clark

of the United States District Court for the Western Dis

trict of Missouri, Western Division, on June 1, 1981

(unreported) ; August 12, 1981 (unreported) ; September

17, 1984 (593 F. Supp. 1485) ; and June 14, 1985 (un

reported) .

2. The jurisdiction of the District Court was based on

28 U.S.C. §§ 1331, 1343 (1982).

3. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant

to 28 U.S.C. § 1291 (1982). The State cross-appellants

filed a timely notice of appeal on August 1, 1985.

(xi)

XU

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Whether the district court properly rejected the

claims of interdistrict liability against the State defend

ants, where there was no racial gerrymandering and no

significant current segregative effects of any discrimina

tory acts.

Milliken V. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974).

Lee v. Lee County Board of Education, 639 F.2d

1243 (5th Cir. 1981).

2. Whether the district court acted within its equitable

discretion in declining to include the proposed elaborate

housing program in its school desegregation remedy.

3. Whether the Kansas City Missouri School District

should be realigned as a plaintiff after it has been found

liable for a constitutional violation.

4. Whether the district court erred in ordering exten

sive remedial programs for every school in the KCMSD,

without adequate findings regarding the extent of injury

caused by the intradistrict violation.

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 263 (1977).

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976).

5. Whether the Eleventh Amendment requires dismis

sal of the State and the State Board of Education as

parties to this case.

Alabama v. Pugh, 438 U.S. 781 (1978).

6. Whether the district court erred in the following

respects in its remedial order: (a) in requiring the State

to continue making full Foundation Formula payments

to the KCMSD, a constitutional violator, for students who

are attending school elsewhere under a transfer program;

(b) in ordering the addition of numerous teachers to the

KCMSD staff throughout the district, over and above

those needed to bring the KCMSD to AAA status; (c)

in awarding block grants to every school in the KCMSD,

without any designation of the money for programs

tailored to injury from segregation; (d) in ordering a

$37 million general capital improvements plan, without

xiii

any finding that current facility problems were related to

segregation; and (e) in allocating more than 77 percent

of the overall costs of the remedial plan to the State and

only 23 percent to the KCMSD, though both were found

jointly liable for the intradistrict violation.

Edelman V. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974).

Liddell v. Missouri, 731 F.2d 1294 (8th Cir. 1984),

cert, denied, 105 S.Ct. 82 (1984).

I n T he

States GJmtrt itf Appeal#

F or th e E ig h th Circuit

No. 85-1765WM

No. 85-1949WM

No. 85-1974WM

Kalima J e n k in s , et al.,

Appellants and Cross-Appellees,

v.

State of Missouri, et al,

Appellees and Cross-Appellants.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Missouri, Western Division,

Honorable Russell G. Clark, Chief Judge

BRIEF OF STATE APPELLEES/CROSS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This lawsuit involves claims regarding the racial com

position of the schools in the Kansas City metropolitan

area. The suit was originally filed in 1977 by the KCMSD

through its superintendent and its school board, and by

students in the district. The named defendants included

the State of Missouri, the Missouri State Board of Edu

cation and various Missouri officials, the State of Kansas,

the Kansas State Board of Education and various Kan

sas officials, several Kansas school districts in the Kansas

City metropolitan area, twelve Missouri school districts

in the area, the United States Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare (HEW), the United States De

partment of Housing and Urban Development (HUD),

and the United States Department of Transportation

(DOT). The lawsuit alleged unconstitutional interdis

2

trict segregation caused by acts of the defendants and

sought a sweeping remedy involving reassignment of

students across district and state lines.

In October 1978, the district court dismissed all of the

Kansas defendants. School District of Kansas City, Mis

souri v. State of Missouri, 460 F. Supp. 421 (W.D.Mo.

1978). The court also realigned the KCMSD as a de

fendant, a ruling that is before this Court in the appeal

brought by the KCMSD (No. 85-1949WM). Thereafter,

in May 1979, students in the KCMSD and in several of

the defendant Missouri school districts filed an amended

complaint.1 All of the non-Kansas defendants originally

named were named again as defendants, and the KCMSD

was added as a new defendant.

The amended complaint, at least as construed by the

district court, made two distinct claims: it realleged the

interdistrict violation alleged in the original complaint;

and it alleged an intradistrict violation, committed by

the KCMSD and by the State defendants, within the

KCMSD. In July 1979, the KCMSD asserted a similarly

dual cross-claim against the State defendants2; it sought

indemnification for its intradistrict liability, and it made

the same allegation of an interdistrict violation as that

made by the plaintiffs.

Before trial began in 1983, the United States Depart

ment of Transportation and one of the Missouri school

districts were dismissed by stipulation, leaving the

KCMSD, eleven suburban school districts (SSDs), the

1 The named plaintiffs were replaced at various times during the

litigation. In February 1985, the court certified a class of all

present and future KCMSD students. The named plaintiffs and the

class are the appellants in No. 85-1765WM and the cross-appellees in

No. 85-1974WM.

2 The State defendants were the State of Missouri, the Governor

of Missouri, the Missouri State Board of Education and its mem

bers, and the Commissioner of Education of the State of Missouri.

In March 1985, the Treasurer of the State of Missouri was added

as a defendant necessary for relief. All of the State defendants are

cross-appellants in No. 85-1974WM and appellees in No. 85-1765WM

and No. 85-1949WM.

3

State defendants, HUD, and HEW (later dismissed) as

defendants. The district court refused to grant the State

of Missouri’s motion to dismiss the State on Eleventh

Amendment grounds. See Order of June 1, 1981 at

13-14; Order of August 12, 1981 at 5-6. The court also

refused to grant, this time upholding an Eleventh Amend

ment defense, a 1980 request by the KCMSD that the

State be ordered to contribute 50 percent of the future

costs of the intradistrict desegregation plan adopted by

the KCMSD in 1977 (Plan 6C) under agreement with

the Office of Civil Rights of HEW. See Order of June 1,

1981 at 17-31.

After hearing months of evidence by the plaintiffs and

KCMSD, and before hearing evidence in response, the

district court dismissed all of the suburban school dis

tricts from the case. Order of April 2, 1984. As de

scribed more fully below, the court found, in accordance

with Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) [Milliken

I], that school districts in Missouri were autonomous and

that none of the districts had committed any interdistrict

violation. Further, in extensive and detailed fact find

ings, the court found that none of the discriminatory

governmental actions advanced by plaintiffs or the

KCMSD to support their interdistrict claims had any

significant current interdistrict segregative effect. See

generally June 5 Order (June 5, 1984, opinion setting

out findings and conclusions underlying April 2, 1984,

dismissal).

The findings of fact in the June 5 Order addressed

each of the theories for finding interdistrict liability.

First, the court held that there had been no manipulation

of district boundaries for racial reasons, finding a “ [l]ack

of proof of discriminatory intent in the establishment or

changing of any school district boundary lines.” Id. at 6.

Second, the court held that the pre-1954 State segrega

tion policy had no significant current interdistrict effects,

finding plaintiffs’ proof on this point to be “weak, specu

lative, and in any event de minim[i]s.” Id. at 12. Third,

the court determined that the pre-1948 State enforcement

4

of racially restrictive covenants had no significant cur

rent interdistrict effects. Id. at 39.8 Taking these matters

together, the district court concluded that “ [a]t most,

plaintiffs’ evidence is de minim[i]s and is therefore

insufficient” to support relief involving the SSDs, Id.

at 98.

The court then heard further evidence and, on Septem

ber 17, 1984, issued its final liability ruling. Jenkins v.

State of Missouri, 593 F. Supp. 1485 (W.D.Mo. 1984)

[“Jenkins”]. In that order, the court first rejected plain

tiffs’ arguments that certain specific pre- and post-1954

actions by the KCMSD and various state agencies were

an adequate basis for finding liability. Thus, the court

denied relief based on practices of the KCMSD such as

allowing liberal transfers and undertaking “intact bus

ing.” Furthermore, it found no basis for liability in

post-1954 State actions concerning vocational schools,

highway location and relocation assistance, and Missouri

Housing Development Commission programs. See id. at

1501-03 (“none of the aforementioned agencies com

mitted any constitutional violation” ).

The court nevertheless did find liability for segregation

within the KCMSD on the part of both the State de

fendants and the KCMSD. The court first noted the un

disputed fact that, prior to 1954, the State and the

KCMSD had imposed a mandatory dual school system

upon the students in the KCMSD. The court stated that,

“having created a dual system, the State and KCMSD

had and continue to have an obligation to disestablish

the system.” Id. at 1504. The court then found that

“there are still vestiges of the State’s dual school system

still lingering in the KCMSD [and that] the obligations

of the KCMSD and the State have not been met.” Id.3 4

3 The court also found that no challenged post-1954 school actions

of the State or the SSDs were racially discriminatory. The inter-

district claims and findings of fact are discussed in much greater

detail in the Argument section below.

4 See also id. at 1505 (“Having found that there are still vestiges

of the dual school system in the KCMSD, the Court finds the issues

5

The court identified two such “vestiges” in its opinion.

Of particular importance was the fact that “24 schools

. . . are racially isolated with 90+% black enrollment.”

Id. at 1493. The court specifically found that, in light

of this condition, “the District did not and has not en

tirely dismantled the dual school system.” Id. The court

also found that “the inferior education indigenous of the

State-compelled dual school system has lingering effects

in the Kansas City, Missouri School District.” Id. at

1492.* 5

The court ordered the State and the KCMSD to de

velop a remedial plan to “establish a unitary school

system within the KCMSD.” Id. at 1506. The KCMSD’s

initial plan proposed consolidation of the KCMSD with

the SSDs. See KCMSD Plan for Remedying Vestiges of

the Segregated Public School System (January 18, 1985).

Because of its earlier rulings against the claims of inter-

district violation, however, the district court rejected

this plan and ordered the KCMSD to prepare an amended

plan “to be implemented within the existing boundaries

of the [KCMSD], which would have the effect of remov

ing the vestiges of the dual school system as it presently

exists in the KCMSD.” Order of January 25, 1985 at 3.

After submission of a new remedial plan by the

KCMSD, and submission of alternative plans by the

State defendants, see note 52 infra, the court held a

two-week hearing on the scope of appropriate relief. On

June 14, 1985, the court issued an order establishing a

multi-faceted district-wide remedial plan. Remedy Order

(June 14, 1985). The plan contemplates a broad upgrad

ing of conditions throughout the KCMSD, at a projected

in favor of plaintiffs against the KCMSD and the State of Missouri

and it further finds the issues in favor of the KCMSD against the

State of Missouri.”)

5 Although the court found that certain actions by the State,

largely the passing of now-superceded statutes, had “encouraged

racial discrimination by private individuals,” it did not rest any

determination of liability on such grounds. Id. at 1503.

cost of at least 87 million dollars during the next three

years.

The plan provides numerous additional teachers, coun

selors, and resources to raise the KCMSD rating to AAA

status. Id. at 7-11. Class sizes will be reduced across the

entire district. Id. at 11-15. Summer school will be made

available to all interested students. Id. at 16-17. So,

too', will all-day kindergarten. Id. at 17-18. Before and

after school tutoring will be made available in certain

elementary schools. Id. at 18-19. An elaborate early

childhood development program will be implemented. Id.

at 19-20. Each school will be given a fixed amount of

money ($50,000-$75,000 in the first year, $100,000-

$125,000 in the third year, with the 90+% black schools

receiving the higher amount) to implement an “effective

schools” program, the specifics to be determined by the

KCMSD. Id. at 20-23. Funding will be provided for

both current and future magnet schools in the KCMSD.

Id. at 23-24. Funding will also be provided for staff

development as well as for a public information specialist.

Id. at 24-25, 37. In addition, the State will ask—indeed,

already has asked—the suburban school districts to par

ticipate in a voluntary interdistrict transfer plan. Id.

at 31-33.6 Finally, a $37 million capital improvements

program—to include the correction of safety, comfort,

and aesthetic problems—will be undertaken. Id. at 33-37.

Of the three-year cost of the remedial plan, the district

court assigned more than 77% to the State, less than

23% to the KCMSD. Id. at 41-42.

Judgment in the case was entered on June 18, 1985,

and three separate appeals were taken. Implementation

of the desegregation remedy is now under way.

6

,8 The court indicated that, in its view, further involuntary stu

dent movement would be highly unlikely to result in additional

stable integration. See Remedy Order at 31. The court did, how

ever, adopt the State defendants’ suggestion that a study be con

ducted of the feasibility of further student reassignment within

the KCMSD. Id. at 26-31.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This desegregation case, involving both interdistrict

and intradistrict claims, has had a long and complicated

history. After several years of discovery and months of

trial, the district court rejected the interdistrict claims,

making extensive findings about the lack of any signifi

cant current segregative effect resulting from the alleged

discriminatory acts. The court did find, however, that

vestiges of the former dual school system remained

within the KCMSD itself, justifying, in its view, a rem

edy for all students and all schools throughout the

KCMSD. It is those various findings, and the law appli

cable to them, that frame the issues on this appeal.

I. The Interdistrict Claims. The district court, in care

ful findings of fact, determined that the plaintiffs and

KCMSD had failed to prove an essential element of

their interdistrict claims: i.e., that any unlawful acts

of the defendants had a significant current segregative

effect on an interdistrict basis. See pages 12-29 infra.

Those findings, largely ignored by the plaintiffs and

KCMSD on appeal, are not clearly erroneous, but mani

festly correct. The court was also correct in holding

that the presumption regarding intradistrict racial dis

parities, recognized in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) [Swann], does

not- apply to interdistrict cases like this one. See pages

31-36 infra. Finally, contrary to the suggestion of the

plaintiffs and KCMSD, the court did not mistakenly deny

interdistrict relief because of an erroneous interpreta

tion of Milliken I.

II. The Intradistrict Claims. The district court found

that the existence of 24 largely-black schools in the

KCMSD was a vestige of the former dual school system

in the district, a questionable finding that the State

nonetheless does not challenge on this appeal. See pages

42-45 infra. But neither that finding, nor a second find

ing about inferior education indigenous to segregation,

can support a remedy of the dimensions imposed by

7

8

the court. Thus, as a general matter, the remedy does

not relate only to conditions properly found to have been

caused by the constitutional violation. See Milliken v.

Bradley, 433 U.S. 263 (1977) [Milliken II]. Further

more, and in any event, particular portions of the rem

edy are inconsistent with Liddell v. Missouri, 731 F.2d

1294 (8th Cir. 1984), cert, denied, 105 S.Ct. 82 (1984)

[.Liddell VII], governing remedial principles, and, in the

case of the allocation of financial responsibility between

the State and KCMSD, the Eleventh Amendment as well.

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Properly Found Against Plaintiffs

and the KCMSD on Their Claims of Interdistrict

Liability.

The plaintiffs and the KCMSD have labored in their

briefs to obscure both the legal standards applicable to

their interdistrict claims and the district court’s findings

of fact. Indeed, both of their briefs are written almost

as though trial court findings had never been made, and

both seek to introduce legal standards that are unsup-

portable as well as wholly unprecedented in school deseg

regation cases. The reasons for this approach are appar

ent. The governing legal standards are simple and clear,

and the district court entered detailed findings of fact

showing that plaintiffs and the KCMSD failed at every

turn to prove the elements of their interdistrict claims.

A. The Law Governing Interdistrict Claims Requires

Proof of Intentionally Discriminatory Acts and A

Significant Current Condition of Segregation Re

sulting From Those Acts.

A violation of the Equal Protection Clause in a school

desegregation case requires “ ‘a current condition of seg

regation resulting from intentional state action.’ ” Wash

ington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 240 (1976) [Davis] (quot

ing Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 205

(1973)). This standard thus requires proof of three

elements: (1) a current condition of racial segregation

(2) caused by (3) the defendant’s purposeful discrim

9

ination. These elements must be proved in any school

desegregation case, whether the alleged violation is inter-

district or intradistrict.

Two aspects of these proof requirements, obvious on

the face of the standard, bear emphasis in analyzing both

of the claims—the interdistrict claim as well as the in

tradistrict claim—in this case. First, the condition of

segregation that must be traced to some unlawful gov

ernmental act is a current condition, not some segrega

tive condition of the past. This being an injunctive ac

tion, it is not enough that an unlawfully caused condi

tion of segregation have existed in 1954; what must be

shown is an unlawfully caused condition of segregation

that exists today.7 8 Second, it is not enough that there

be, on the one hand, current racial disparities and, on

the other hand, some discriminatory acts: the acts must

have caused the disparities before a violation may be

found.®

These general standards take on a special shape where

the segregation alleged is interdistrict in nature—that is,

segregation between districts—and the school districts ex

hibit a marked degree of local control. In that circum

stance, the three basic elements of a constitutional viola

tion must still be proved, but the proof requirements for

the three elements apply differently and are heightened.

The Supreme Court set out the standards governing a

claim for interdistrict relief in Milliken I :

Before the boundaries of separate and autonomous

school districts may be set aside by consolidating the

separate units for remedial purposes or by imposing

a cross-district remedy, it must first be shown that

there has been a constitutional violation within one

district that produces a significant segregative effect

7 See, e.g., Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449,

458-68 (1979) [Columbus]; Milliken II, 433 U.S. at 280-88; Swann,

402 U.S. at 15-16.

8 See, e.g., Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 433 U.S.

406, 413 (1977) [Dayton 7]; Milliken II, 433 U.S. at 282; Davis,

426 U.S. at 239.

10

in another district. Specifically, it must be shown

that racially discriminatory acts of the state or local

school districts, or of a single school district have

been a substantial cause of interdistrict segregation.

Thus an interdistrict remedy might be in order

where the racially discriminatory acts of one or

more school districts caused racial segregation in an

adjacent district, or where district lines have been

deliberately drawn on the basis of race. In such cir

cumstances an interdistrict remedy would be appro

priate to eliminate the interdistrict segregation di

rectly caused by the constitutional violation. Con

versely, without an interdistrict violation and inter

district effect, there is no constitutional wrong call

ing for an interdistrict remedy.

418 U.S. at 744-45. Thus, in any case in which a state

school system exhibits a large measure of local control,

Milliken I requires that parties seeking an interdistrict

remedy prove either (a) that the school district boun

daries were manipulated for racial reasons or (b) that

some intentionally discriminatory action by the govern

mental defendants—the State or the local school dis

tricts—was a “substantial cause” of “significant” current

interdistrict segregation. Id.; see Hills v. Gautreaux, 425

U.S. 284, 294 & n. 11 (1976) [Hills] (Milliken I re

quires demonstration of “significant” interdistrict segre

gative effects caused by unlawful governmental a c t);

Lee v. Lee County Board of Education, 639 F.2d 1243,

1254-56 (5th Cir. 1981).

These Milliken I standards apply to the interdistrict

claims in this case because education in Missouri ex

hibits the requisite degree of local control. As the dis

trict court found below, “each of the school districts is a

locally autonomous and independent entity.” June 5

Order at 12. Thus, Missouri school districts have the

power to establish their own boundaries by local initia

tive, Mo. Rev. Stat. §§ 162.222, 162.431, 162.441 (1978

& Supp, 1983), and indeed the Missouri Constitution pro

hibits the legislature from passing any “special law”

affecting school district boundaries, Mo. Const, art. 3,

11

§ 40(20). See June 5 Order at 8, 11. School districts

are governed by locally elected boards of education and

have sweeping or plenary authority to make decisions

regarding curriculum, finance, personnel, student assign

ment, transportation, and administration. Id. at 8-11;

see Lowell Dep. at 6 (transportation); PL Exh. 2267

(student assignment); PL Exh. 1737 (finance) ; Tr.

6179-80 (locally elected boards, personnel, finance). For

these and other reasons,® the district court found that

“the SSDs are more autonomous than those [districts]

discussed in Milliken and numerous other desegregation

cases.” Id. at 7-8.w Hence, due regard for the tradition

of local control in education requires that the Milliken I

standards be applied to the interdistrict claims in this

case.* 10 11

0 The district court also found that, before 1954, local school

districts had substantial autonomy in deciding whether to provide

schools for their black students or to transfer them to other dis

tricts. June 5 Order at 11; see Tr. 335-36, 372, 378, 622-24, 696-97,

871-72, 1084-86, 1124-26, 1136-38, 1154, 1199, 5837; PI. Exh. 1814;

see notes 18, 19 infra. The court further noted that the federal

Office of Civil Rights in HEW (now Department of Education) has

always considered Missouri school districts autonomous and that

school boards must be sued in their own names and do not share

the State’s Eleventh Amendment immunity. Id . ; see High Dep. vol.

1 at 65, 70, 110-11; Ward Dep. vol. 1 at 30; Mount Healthy City

School District v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274, 280 (1977) ; Miener v.

Missouri, 673 F.2d 969, 980-81 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 459 U.S.

909 (1982).

10 The court found at least as much local control in the Missouri

schools as that found in Alabama in Lee v, Lee County Board of

Education, supra, and more local control of boundaries or other

matters than in Michigan, see Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215,

247-48 (6th Cir. 1973), rev’d, Milliken I, 418 U.S. 717 (1974), in

Indiana, see United States v. Board of School Commissioners of the

City of Indianapolis, 637 F.2d 1101, 1124-25 (7th Cir. 1980), cert,

denied, 449 U.S. 838 (1980), in Delaware, see Evans v. Buchanan,

393 F. Supp. 428, 438 (D.Del.), aff’d, mem., 423 U.S. 963 (1975),

and in Kentucky, see Newburg Area Council, Inc. v. Board of Edu

cation of Jefferson County, 510 F.2d 1358 (6th Cir. 1974), cert,

denied, 421 U.S. 931 (1975).

11 The KCMSD seeks to get around these standards by suggesting

that the autonomy of local school districts in Missouri is “a dubious

legal proposition.” KCMSD Brief at 27 n. 80. The treatment of local

school districts as mere “instrumentalities of the State” is, how

12

To make out their claim for interdistrict relief against

the State defendants, the plaintiffs and the KCMSD were

accordingly required to show either (a) that the State

had engaged in the racially motivated manipulation of

the boundaries of the KCMSD or the SSDs or (b) that

some discriminatory State action other than racial gerry

mandering was a substantial cause of significant current

interdistrict segregation. They failed on both counts.

B. The District Court Correctly Found That School

Boundaries In the Kansas City Metropolitan Area

Were Not Set or Maintained With a Discriminatory

Purpose.

The district court expressly found an utter “ [l]ack of

proof of discriminatory intent in the establishment or

changing of any school district boundary lines.” June 5

Order at 6. The court stated: “There was no credible

evidence that any of the boundaries of any defendant

school district were established or maintained with any

racially discriminatory intent.” Id. at 9. Indeed, the

district court made this specific finding with respect to

every one of the SSDs except Grandview, about which no

boundary issue had ever been raised. See id. at 43 (Blue

Springs), 45 (Center), 48 (Fort Osage), 54-55 (Hick

man Mills), 59-61 (Independence), 67 (Lee’s Summit),

74 (Liberty), 78 (North Kansas City), 83-84 (Park

Hill), 91 (Raytown).

The importance of these findings can best be under

stood by reference to the caselaw on which plaintiffs and

the KCMSD exclusively depend. For, in failing to prove

any governmental manipulation of school district bound

aries for racial reasons, the plaintiffs and the KCMSD

distinguished their claim for interdistrict liability from

the interdistrict claims in every school desegregation case

in which such a claim has prevailed. All of these cases

ever, just the sort of treatment rejected by the Supreme Court in

Milliken I in the face of similar claims of ultimate state authority.

418 U.S. at 726 n. 5, 741-43. The argument that “no significant

local autonomy existed with respect to the pre-1954 interdistrict

school system for blacks” is simply incorrect. See notes 18, 19 infra.

13

involved racially motivated governmental decisions about

the drawing or maintaining of school district boundaries.

This is true, as the district court recognized, see June 5

Order at 6-7, of the three cases from this Circuit involv

ing findings of interdistrict liability—MorrUton School

District No. 32 v. United States, 606 F.2d 222, 225-28

(8th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 1071 (1980);

United States v. Missouri, 515 F.2d 1365, 1367-70 (8th

Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 951 (1975); and Haney v.

County Board of Education, 410 F.2d 920, 923-24 (8th

Cir. 1969). It is equally true, as the district court also

recognized, see June 5 Order at 9-10, of the Wilmington

case,1'2 the Indianapolis case,12 13 the Louisville case,14 and

the Allegheny County case.15 See also Berry v. School

District of the City of Benton Harbor, 564 F. Supp. 617,

625 (W.D. Mich. 1983) ; United States v. Texas, 321

F. Supp. 1043, 1048-50 (E.D. Tex. 1970), aff’d in rele

vant part, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 1016 (1972). By contrast, in case after case

that did not involve some kind of racial gerrymandering,

the courts have repeatedly rejected the claims of inter-

district liability.16

12 Evans v. Buchanan, 393 F. Supp. 428, 438-45 (D.Del), aff’d

mem., 423 U.S. 963 (1975); see Evans V. Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750,

762-63 n. 11 (3d Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 446 U.S. 923 (1980) (not

ing state legislation regarding boundaries as basis for interdistrict

liability).

13 United States v. Board of School Commissioners of the City of

Indianapolis, 456 F. Supp. 183, 188 (S.D.Ind. 1978), aff’d in rele

vant part, 637 F.2d 1101, 1108 (7th Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 449

U.S. 838 (1980).

14 Newburg Area Council, Inc. v. Board of Education of Jefferson

County, Kentucky, 510 F.2d 1358 (6th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421

U. S. 931 (1975) ; see Lee v. Lee County Board of Education, supra,

639 F.2d at 1257-58 (in Newburg, “school district boundaries had

been artificially maintained in order to preserve the racial charac

teristics of the school districts involved”) .

15 Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 672 F.2d 1107, 1116,

1120 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 824 (1982).

16 See, e.g., Milliken I, supra-, Goldsboro City Board of Education

V. Wayne County Board of Education, 745 F.2d 324 (4th Cir. 1984);

Berry v. School District of the City of Benton Harbor, 698 F.2d

813, 818-19 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 892 (1983); Lee V. Lee

14

The plaintiffs and the KCMSD were therefore left

with a claim for interdistrict relief unique in the annals

of school desegregation law. Unable to establish any un

lawful creation or maintenance of school district bound

aries by the State or by any of the local school districts,

the plaintiffs and the KCMSD were consigned to proving

their interdistrict claims indirectly. They were required

to show, as no proponents of interdistrict relief in any

case have yet succeeded in showing, that some racially

discriminatory act other than gerrymandering was a

substantial cause of significant current interdistrict seg

regation. The district court below found that plaintiffs

and the KCMSD had made no such showing.

C. The District Court Correctly Found That No

Racially Discriminatory Act of the State Was a

Substantial Cause of Significant Current Inter

district Segregation.

In trying to overcome the finding that current racial

disparities among the SSDs and the KCMSD are not the

result of a constitutional violation, the plaintiffs and the

KCMSD have chosen to emphasize the one element most

favorable to them: the fact of current racial disparities.

It is undisputed, of course, that there is a much heavier

concentration of black students in the urban KCMSD

than in the suburban SSDs.17 No interdistrict violation

is shown, however, by the mere fact that one school dis

trict is largely black while neighboring districts are

largely white: the contention to the contrary is precisely

County Board of Education, swpra; Taylor v. Ouachita Parish

School Board, 648 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1981) ; Cunningham, v. Grayson,

541 F.2d 538 (6th Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 1074 (1977) ;

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 462 F.2d 1058 (4th Cir. 1972)'

aff’d by equally divided court, 412 U.S. 92 (1973); Tasby v. Estes,

412 F. Supp. 1185 (N.D.Tex. 1975), aff’d on interdistrict issues, 572

F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, granted, 440 U.S. 906 (1979), cert,

dismissed, 444 U.S. 437 (1980); Armour v. Nix, No. 16,708 (N D

Ga. 1979), aff’d, 446 U.S. 930 (1980).

17 In 1982, approximately 68% of the KCMSD’s student population

was black, whereas approximately 5% of the SSD’s student popula

tion was black. The percentage of black students in the SSDs, how

ever, varies greatly from district to district. See PL Exh.’ 53G.

15

what Milliken I rejected. Indeed, the situation in Kansas

City—the concentration of blacks in an urban area with

predominantly white suburbs—is the situation in most

cities in the United States today. See Tr. 16,486-88 (tes

timony of KCMSD witness, Dr. Daniel Levine) (Kansas

City typical of big cities in evolution of racial patterns);

Tr. 19,082 (testimony of Dr. William Clark) (same) ;

Columbus, 443 U.S. at 485 (Powell, J., dissenting).

Appellants thus had to show something more than the

existence of racial disparities to establish interdistrict

liability on the part of the State defendants: i.e., that

racially discriminatory acts of the State were a substan

tial cause of the current disparities. In attempting to

meet this burden, the plaintiffs and the KCMSD identi

fied three bases for interdistrict liability on the part of

the State defendants—the pre-1954 State school-segrega

tion policy; certain post-1954 State school-related actions;

and certain housing-related actions. The district court,

however, unscrambled the jumbled allegations of unlaw

ful conduct, carefully analyzed the evidence to determine

whether they were in fact discriminatory acts causing

significant current segregation, and found on every spe

cific basis for interdistrict liability that the plaintiffs and

the KCMSD had failed in their proof.

1. Pre-1954 S ta te School Policies.

The first, and by far the most important, asserted

basis for interdistrict liability on the part of the State

is the pre-1954 policy of mandatory segregation. As the

State defendants have conceded throughout this litiga

tion, the State of Missouri unconstitutionally mandated

separate schools for black and white children prior to the

1954 decision by the United States Supreme Court in

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 483 (1954)

[Brown]. Mo. Const, art. IX, § l ( a ) (1945). See

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277, 1280 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied, 449 U.S. 826 (1980). That policy, although

not formally removed from the State Constitution until

1976, was declared unenforceable by the Attorney Gen

16

era! of Missouri in 1954 and removed from the statute

books by 1957. Act of July 6, 1957, § 1, 1957 Mo. Laws

452-53; PI. Exh. 2232. Nevertheless, the plaintiffs and

the KCMSD sought to prove in the district court that

the interdistrict racial disparities today, more than thirty

years later, were substantially caused by the pre-1954

mandatory segregation. Their theory was that the segre

gation policy caused a dearth of black schools outside the

KCMSD, which in turn caused today’s concentration of

blacks in the KCMSD. The district court found to the

contrary: as the court said, “ [plaintiffs’ proof was

weak, speculative, and in any event de minim[i]s.” June

5 Order at 12.

To begin with, even when the segregation laws were in

effect more than thirty years ago, they did not mandate

interdistrict segregation. The policy of the State of Mis

souri was to require separate schools for black and white

children; the State “did not require separate school dis

tricts.” June 5 Order at 15. State law, moreover, at

least after 1887, did not prohibit the maintenance of black

schools in the SSDs or their predecessors. Although State

law had varying provisions over the years for the edu

cation of black students in districts with a very small

black enrollment (roughly 8 to 25), the manner in which

districts educated resident black students—whether a

black school was maintained or black students were trans

ferred to other districts—was generally a matter for lo

cal decision. See id.; Tr. 5837 (testimony of plaintiffs’

witness, Dr. Anderson); PL Exh. 116A, 1814.1® In fact, 18

18 Both the plaintiffs and the KCMSD assert that State law long

prohibited the maintenance of black schools in districts with less

than a certain minimum number of black students. KCMSD Brief

at 3, 6; Plaintiffs Brief at 5. The plaintiffs’ and the KCMSD’s read

ing of the statutes is simply wrong. Although such a prohibition

existed before 1887, Missouri law has contained no such prohibition

for nearly 100 years.

In 1887, the Missouri legislature repealed the requirement of

1870 Mo. Laws 149, § 45, and 1874 Mo. Laws 163-64, § 73, codified

at Mo. Rev. Stat. art. 1, ch. 150, § 7052, that districts with fewer

than 10 black students close their black school. See 1887 Mo. Laws

17

for many years, Missouri law required black schools in

small districts.19 And there were black schools in some of

the SSDs and their predecessors before 1954. See June 5

Order at 61-62 (black school in Independence), 74-75

(black school in Liberty), 79 (black school in North Kan

sas City), 84-86 (black school in Park H ill); PI. Exh. 39.

In any event, the plaintiffs and the KCMSD simply

failed to prove that, whatever the conditions in the SSDs

may have been, a significant number of black students

from the SSDs moved to, or transferred to school in, the

KCMSD. The absolute numbers, the district court found,

themselves show that insignificance. Thus, with respect

to moves, the court below, looking at the two critical pe

riods of 1910-1920 and 1930-1960 (i.e., extending even

beyond Brown), found: “ [ejven assuming the entire de

crease in the three-county area can be accounted for

264, codified at Mo. Rev. Stat. §§ 8003 & 8004 (1889) . In 1893, a

proviso was added to the 1887 statute that permitted, but did not

require, a school district with fewer than eight black students to

discontinue its black school. 1893 Mo. Laws 247 (district “may

discontinue” black school). The statute, as thus amended, was

carried forward in 1909 Mo. Laws 790, § 42, and codified at Mo.

Rev. Stat. art. 2, ch. 102, §§ 11145 & 11146 (1919). See Plaintiffs

& KCMSD Jt. Addendum A at A81-A82. The 1929 revision of the

statute likewise contained no prohibition on maintaining a black

school without a minimum number of black students. 1929 Mo.

Laws 382-83, codified at Mo. Rev. Stat. ch. 72, § 10350 (1939) ; see

1946 Mo. Laws 1699-1700 (reenacting statute without modification

in any relevant respect). See also PI. Exh. 116A (collecting statutes).

19 Replacing similar statutes enacted in 1865 and 1869, see 1865

Mo. Laws 177, § 20; 1869 Mo. Laws 86, the Missouri legislature in

1870 required the provision of a black school in any district with

at least 16 black students. 1870 Mo. Laws 149, § 45. This provision

was repeated in § 73 of 1874 Mo. Laws 163-64, while § 74 added a

requirement that, if two adjoining districts each had less, but

together had more, than 16 black students, they must jointly estab

lish a black school. The minimum number was changed to 15 in

1887. See 1887 Mo. Laws 264, codified at Mo. Rev. Stat. §§ 8003 &

8004 (1889) and Mo. Rev. Stat. art. 2, ch. 102, §■§ 11145 & 11146

(1919). This law was not significantly modified until 1929. See

1929 Mo. Laws 382-83. Thereafter, a school district with 8 black

children was required either to maintain a black school or to pay

the transportation and tuition for black students to attend in

another district. See PI. Exh. 116A (collecting statutes).

18

only by people leaving and going to Kansas City because

of the dual school system, . . . the impact of that move

ment on the KCMSD enumeration [is] insignificant.”

June 5 Order at 16.2<> With respect to transfers, the

court found the pre-1954 totals equally insignificant: in

1954, less that 0.5% of the KCMSD black enrollment

consisted of transfers, and that number included trans

fers from districts other than the SSDs, Ibid.20 21 Moreover,

the evidence showed that many of the transferees did

not move to where they transferred to school. Id. at 18

(citing Tr. 372, 565, 632-36, 676-80, 714, 719, 841, 1216-

17, 1334-35, 1358-60, 1664-65, 2587-88, 2699-2704, 3170-

73).22 Thus, the impact of transfers and moves even

20 In 1910-1920, the black enumeration in the three-county area

outside the KCMSD decreased by 287 while the black enumeration

in the KCMSD increased by 6,676. In 1930-1960, the decrease out

side the KCMSD was 550 while the increase in the KCMSD was

45,000. June 5 Order at 15-16.

21 The district court found that, over the half-century from 1900

to 1954, only 251 students transferred into the KCMSD from the

SSDs. June 5 Order a t 16. This amounted to only 4,6 students

per year. Even assuming, arguendo, that all of the roughly 600

student transfers recorded on PI. Exh. 40 came from predecessors of

the SSDs—an assumption clearly unwarranted by the evidence, see

Tr. 4557-59—the figure would amount to only 11.1 students per

year. In either event, the numbers are insignificant. See Tasby v.

Estes, supra, 572 F.2d at 1015 n. 19 (eleven transfers insignificant).

In addition, the district court noted the insignificance of the number

of transfers to Lincoln High School (the black high school) in the

KCMSD prior to 1954. June 5 Order at 16-17 (citing Tr. 1773).

Of course, none of these numbers reflects the reasons for the

transfers. In particular, none reveals whether black schools were

available in the districts from which the students transferred or

whether the absence of a black school was the cause of the transfer.

22 The plaintiffs submitted a list of 44 names of students who

allegedly transferred to Lincoln High School before 1954 and

moved to the KCMSD after transferring. Of the people on this

list, however, a number now live outside the KCMSD, some lived

in the KCMSD only briefly, and some did not transfer until after

1954, when the State’s segregation policy was no longer in effect.

For these reasons, and both because there was no “credible evidence

as to why these 44 people moved to Kansas City” and because the

total is “insignificant in any event,” the district court concluded

that the list “does not show a connection between black schools in

Kansas City and the movement of blacks into Kansas City.” June 5

Order at 17.

19

before 1954 was wholly insubstantial.23

Having failed to show any significant numbers of

moves to the KCMSD from the SSDs or their predeces

sors, plaintiffs and the KCMSD also failed to show that

even the limited number of moves were motivated by the

unavailability of black schools outside the KCMSD. Nor

did they demonstrate that a lack of available suburban

schools was the reason for the substantial migration of

blacks into the KCMSD from outside the metropolitan

Kansas City area. Indeed, the district court specifically

found to the contrary. To whatever extent schools were

in fact unavailable, the court found that “the absence of

black schools in any of the defendant districts did not

discourage black families from outside (or from within)

Missouri from moving to and living in those districts.”

June 5 Order at 18 (citing Tr. 1153-54, 1213-14, 1252-

54). The motivation for the migration into the KCMSD

(not just of blacks, but of whites as well) was primarily

the economic opportunities available there.

The findings on this point are comprehensive. Thus,

the court found that the largest pre-1954 black population

increases in the KCMSD occurred during the two world

war periods and, as was true all over the country, were

“in large part due to the unusual economic and employ

ment ramifications of the world wars and intervening

depression.” Id. at 17 (citing Tr. 5932-34, 9988-90).

Outside Kansas City, Liberty, Independence, and Excelsior

Springs, blacks in the three-county area were “mostly

rural, farm-dependent families,” id. at 16 (citing Tr. 331,

454, 526, 796, 901-06, 935, 952, 1008, 1052, 1089, 1100-

05, 3139, 3165-66), and the increase in black population

in the KCMSD was due to the availability of jobs and

economic opportunities in the city.24 By contrast, the

23 See June 5 Order at 43 (Blue Springs) ; 45-46 (Center) ; 49

(Ft. Osage) ; 51 (Grandview) ; 55 (Hickman Mills) ; 61-62 (Inde

pendence) ; 67-70 (Lee’s Summit); 74-75 (Liberty) ; 78-79 (North

Kansas C ity); 84-87 (Park Hill) ; 91 (Raytown).

24 The period from 1910 to 1960 is well-recognized as the period

of massive emigration of blacks from rural to urban areas all over

20

movement of blacks into communities within the SSDs or

their predecessors did not vary according to whether the

particular community had a black school, thus refuting

the suggestion that the availability of schools was what

attracted blacks to the KCMSD rather than to the outly

ing districts.25 As the district court found, “jobs and eco

nomic opportunity were primary motivators for blacks

leaving the three-county area and moving to Kansas City

and elsewhere, and . . . any motivation resulting from

segregated schools was de minimis and insignificant when

compared to those primary motivating factors.” Id. at

18. See Tr. 595, 600, 676-78, 713, 796, 911, 1052, 1089,

1103, 1111, 1163, 1307-18, 1552, 1579-80, 1680-81, 1728,

2781, 3214, 3267.

Of course, the effect that plaintiffs and the KCMSD

must trace to the pre-1954 segregation policy is a current

effect, not an effect in 1954. Thus, the failure to prove

that the pre-1954 segregation policy was a substantial

cause of interdistrict disparities before 1954 translates

into an even clearer failure to prove that the pre-1954

policy was a substantial cause of interdistrict disparities

today. If the pre-1954 interdistrict effects were negligi

ble, the effects are even more negligible after thirty years

in a “dynamic” and “fluid” society in which “myriad

factors produce a multitude of simultaneous decisions and

consequent effects” and in which “many events have in

tervened, reshaping earlier actions.” June 5 Order at 98-

the country. See Milliken I, 418 U.S. at 759 n. 9 (Douglas, J.,

dissenting) (citing Hauser, “Demographic Factors in the Integra

tion of the Negro,” Daedalus 847-77 (fall 1965), and U.S. Dep’t of

HEW, J. Coleman et al., Equality of Educational Opportunity 39-40

(1966)).

25 Thus, not one of those areas that had black schools experienced

any appreciable increase in its black population, while blacks moved

into some areas that did not have black schools. See June 5 Order

at 61-62 (black school in Independence, but no increase in black

population) ; 69 (black families moved into Lee’s Summit even

though no black school) ; 74-75 (black school in Liberty, but no

increase in black enumeration, see PI. Exh. 49) ; 79 (black school in

North Kansas City, but no increase in black enumeration) ; 84-86

(black school in Park Hill, but no increase in enumeration).

21

99; see also id. at 18 (“The Court further finds that

transferring blacks to the KCMSD under the prior segre

ga ted school system is not a cause of the present racial

distribution of the population in the three-county area”) ;

(“plaintiffs have not persuaded the Court that any

vestiges or significant effects of the pre-1954 dual school

system remain in any of the SSDs”) .

Indeed, a brief look at the post-1954 history shows

just how patent was the plaintiffs’ and the KCMSD’s

failure of proof. The critical fact is that the massive

increase in the KCMSD’s black population occurred after

1954, when the segregation policy had already been de

clared void, and not in the years when the segregation

policy was in effect. Thus, in 1955-56, the black enroll

ment in the KCMSD was only 11,625; by 1971-72, it had

increased to 35,620 (from which it then declined to 24,803

in 1983-84). KCMSD Exh. K2. Moreover, from 1881 to

1954, the percentage of black students in the KCMSD was

virtually unchanged—13.6% of the total student popula

tion in 1881, and 14.0% in 1954. PL Exh. 53E [sub] ;

June 5 Order at 16.26 By contrast, after 1954, the per

centage of blacks in the KCMSD increased steadily—from

18.9% in the 1955-56 school year to 50.2% in the 1970-

71 school year to 67.7% in the 1983-84 school year.

KCMSD Exh. K2.

These numbers have an obvious significance for two

reasons. First, they show that the greatest increase in

black population in the KCMSD occurred at a time when

the pre-1954 segregation policy was not operative, a time

when the availability of schools could not have been a

reason for residential decisions. Second, the growth in

black population after 1954—for reasons largely unrelated

to schools—reinforces the finding that the movement of

blacks to Kansas City before 1954 was also for reasons

26 Further, after 1910, the percentage of blacks in the enumera

tion of the three-county area outside the KCMSD was never more

than 4.4%, and the total number was never more than 859. The

figures for 1920 are 3.1% and 572, highs for the period 1920-1954.

PI. Ex. 53E[sub],

22

unrelated to schools. The numbers thus confirm the dis

trict court’s finding that all but an insignificant portion

of today’s black KCMSD population is not in the KCMSD

because of the pre-1954 policy but for other—namely,

economic—reasons.

2. Post-1954 School-Related Actions.

All of the suburban school districts, the court below

found, became unitary school districts soon after Brown.

See June 5 Order at 19, 99. Black enrollments in the

SSDs have steadily increased at least since 1968. Id. at

36; PL Exh. 53G, 53H. Since shortly after Brown, as

the district court found, “school district boundaries have

not constrained black movement in any way.” Id. at 39.

Nevertheless, the plaintiffs and the KCMSD have

pointed to a number of post-1954 school-related actions as

a second alleged basis for interdistrict liability. Most of

the identified actions were taken solely by the suburban

school districts, however; only a few were actions of the

State.27 Of these few State actions, the district court

found that none was racially discriminatory.

The first allegation involved the Area Vocational Tech

nical School program. The district court found, however,

that the State committed no violation in this program.

Although the State distributed the federal funds for the

program, “ [e]ach district, in its discretion, determined

whether or not to participate in the program and in what

manner.” June 5 Order at 23. In any event, the district

court, after reviewing the evidence concerning the voca

tional schools in each district, id. at 23-26, found that

“ [t]he area schools were established without discrimina

tory intent and there was no credible evidence that their

operation had the effect of segregating students on the

27 Neither plaintiffs nor the KCMSD has sought to impose

vicarious liability on the State defendants for acts of local school

districts not taken pursuant to State policy. This is hardly surpris

ing given that there is no principal-agent relationship between the

State defendants and autonomous school districts and* that there is

no vicarious liability under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (1982). See Monell

V. Department of Social Services, 436 U.S. 658, 690-691 (1978).

23

basis of race.” Id. at 26. The court also found “no evi

dence that vocational educational monies have been dis

tributed with a purposefully discriminatory motive or

effect.” Id. Thus, on two counts—the absence of either

discriminatory purpose or effect—“the operation of voca

tional education in the Kansas City metropolitan area

is not an interdistrict constitutional violation.” Id. See

also Jenkins, at 1495.28

The plaintiffs and the KCMSD also alleged that the

enactment of House Bill 171 in 1957 was a constitutional

violation. The bill amended Mo. Rev. Stat. § 165.563

(1943), which had declared that any city of over 500,000

was to be a single school district, to apply thereafter only

to cities of over 700,000. The district court found that

H.B. 171 “was not discriminatorily enacted.” June 5 Or

der at 27. Among the articulated bases for this finding

of fact were the following: that neither the original 1897

law (setting the level at 300,000) nor its 1909 revision

(raising it to 500,000) was enacted for racial reasons;

that H.B. 171 was passed unanimously and counted

among its supporters a black representative from the

KCMSD who had long been a promoter of civil rights;

that there were racially neutral administrative reasons

for passage of the bill as well as for its having been sup

ported even by the KCMSD; and that the bill did not

affect the KCMSD in 1957 and, since then, several an

nexations to the KCMSD have increased its white popula

tion. Id. at 27-29.29

w Plaintiffs do not appear to allege on appeal that any State

action concerning the vocational-technical schools was racially dis

criminatory. Plaintiffs’ Brief at 28-29. Indeed, plaintiffs assert that,

when the State initiated the program, it did so “without considering

[the schools’] impact on racial isolation.” Ibid.

29 Although both the plaintiffs and the KCMSD point to H.B. 171

as a basis for State interdistrict liability, the KCMSD does not

allege racial motivation in the passage of H.B. 171 (which the

KCMSD itself supported), and the plaintiffs do not challenge the

district court’s finding as clearly erroneous, the finding clearly

being amply supported by the record. See KCMSD Brief at 14;

Plaintiffs’ Brief at 27.

24

The plaintiffs and the KCMSD further pointed to the

State’s inaction on the Spainhower Commission proposals

as a basis of interdistrict liability. The Spainhower pro

posals—made in 1979, after this lawsuit was filed and

after the KCMSD’s Plan 6C was in place-—contained

wide-ranging recommendations for the restructuring of

school financing, boundaries, and local control. But, to

begin with, the failure to act upon proposals that might

increase integration is itself not a constitutional violation

unless there is a preexisting duty to take such action,

which was not the situation here. Furthermore, as the

district court found, the reason that the Legislature did

not enact these proposals was simply that “it desired to

maintain Missouri’s strong tradition of local control over

public education.” June 5 Order at 29. Reviewing the

evidence, the court found that any race-motivated opposi

tion by particular legislators or private individuals was

insignificant and not adopted by or an influence on any

government entity. See id. at 29-31. Thus, the court

specifically found, “ [t]here was no credible evidence . . .

that racial concerns led to the defeat of the Spainhower

recommendations.” Ibid.50

In addition, the plaintiffs and the KCMSD pointed to the

State’s failure to adopt the “Milwaukee Plan” proposal,

embodied in H.B. 1717 in 1979, to provide State money

to school districts as an incentive for participating in

interdistrict transfer programs akin to the one in Mil

waukee. The court noted that the State Department of

Elementary and Secondary Education opposed the meas

ure as too expensive. See June 5 Order at 31. It identi

fied no evidence that the State or any SSD opposed the

measure for reasons related to race. Ibid.30 31

30 Neither the plaintiffs nor the KCMSD contends on appeal that

the district court’s finding of no discriminatory purpose in the

non-adoption of the Spainhower proposals is clearly erroneous.

See KCMSD Brief at 13; Plaintiffs’ Brief at 27-28.

31 Neither plaintiffs nor the KCMSD alleges on appeal that re

jection of the Milwaukee Plan was for racial reasons. See KCMSD

Brief at 14 n.41; Plaintiffs’ Brief at 28.

25

In sum, none of the post-1954 actions for which the

plaintiffs and the KCMSD seek to hold the State defend

ants liable for an interdistrict violation was a purpose

fully discriminatory act causing significant interdistrict

segregation.32 Because the autonomy of local districts

means that their acts cannot form a basis of State lia

bility, the plaintiffs and the KCMSD do not seek to base

State interdistrict liability on the defendant school dis

tricts’ allegedly unconstitutional post-1954 acts. See

KCMSD Brief at 12-16; Plaintiffs’ Brief at 26-29. In

any event, the district court found that each of the local

districts’ alleged violations was not in fact an interdistrict

violation.33

82 In the district court, the plaintiffs also advanced arguments

about juvenile homes as a basis for State interdistrict liability.

The district court found that “there is absolutely no showing that

the schools have had a racial impact on the KCMSD or any SSD.”

June 5 Order at 21. Apparently, neither the plaintiffs nor the

KCMSD challenges this finding on appeal.

83 The district court found that the Cooperating School Districts

Association of Suburban Kansas City had not been racially moti

vated in any of its actions and that no SSD joined with racial