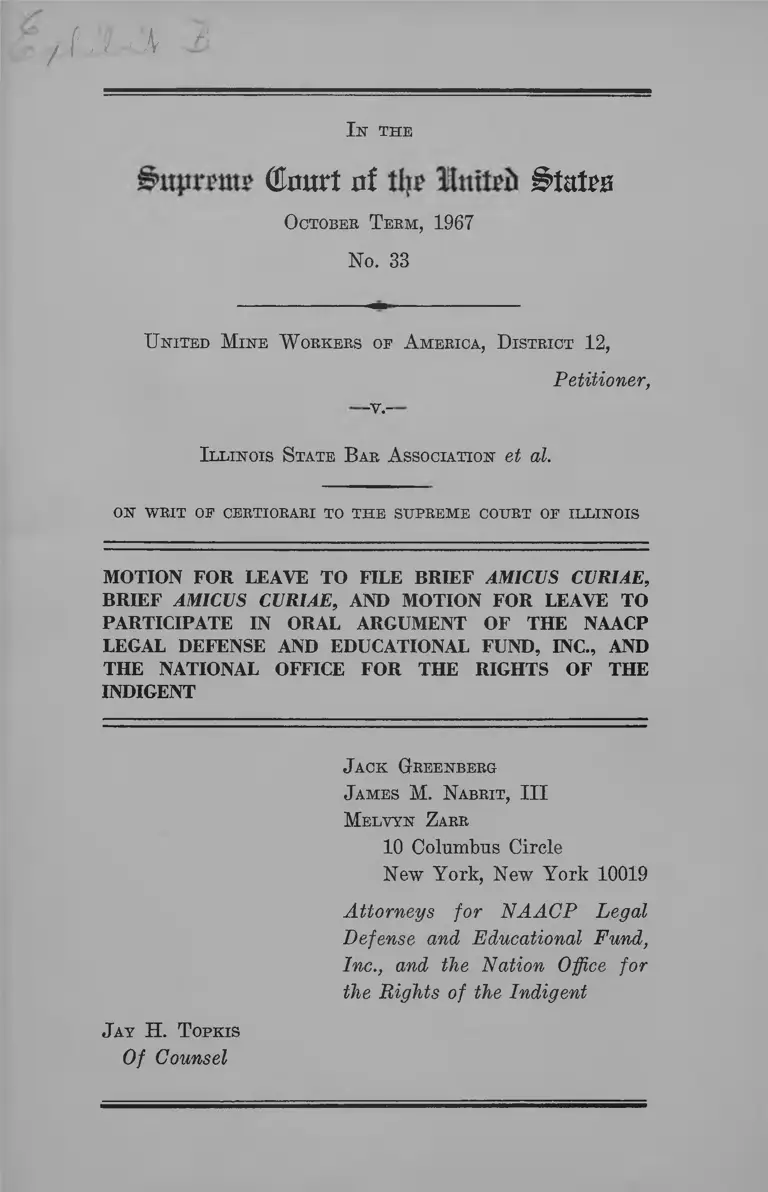

United Mine Workers of America, District 12 v. Illinois State Bar Association Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae and Motion for Leave to Participate in Oral Argument

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Mine Workers of America, District 12 v. Illinois State Bar Association Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae and Motion for Leave to Participate in Oral Argument, 1967. 36813527-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ad1cb336-6685-4afc-a6ad-016c840f7270/united-mine-workers-of-america-district-12-v-illinois-state-bar-association-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae-and-motion-for-leave-to-participate-in-oral-argument. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

/ ' f ̂ V '■ A a;

Iir THE

Olflurt nt BUUb

October T eem, 1967

No. 33

U nited Mine W orkers of A merica, District 12,

Petitioner,

-V.-

I llinois State B ar A ssociation et at.

ON writ of certiorari to the supreme court of ILLINOIS

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE,

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE, AND MOTION FOR LEAVE TO

PARTICIPATE IN ORAL ARGUMENT OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND

THE NATIONAL OFFICE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE

INDIGENT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, II I

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and the Nation Office for

the Rights of the Indigent

J ay H . T opkis

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

MOTION FOE LEAVE TO FILE B EIEF AMICUS

CURIAE .............................................................................. 1

B EIEF AMICUS CURIAE

Statement of the C ase....................................................... 5

Summary of A rgum ent..................................................... 6

Argument ........................ 8

Introduction ................................................................ 8

I. A Great Gap Exists Between the Legal Ser

vices Americans Need and the Legal Services

They Can Atford Under the Traditional Fee

System .................................................................... 9

II. Creative Elements in the Legal Profession Have

Eecently Undertaken to Develop New Forms

of Practice to Satisfy the Manifest Need for

More Plentiful, Efficient and Inexpensive Legal

Services .................................................................. 14

III. The Eigid Employment of the Canons of Ethics

by State and Local Bar Associations to Throttle

These New Forms Is Eetarding Progress

Toward Satisfying the Manifest Need for Ser

vices ........................................................................ 26

u

PAGE

IV. There Is a Constitutional Eight to Associate

to Give and Eeceive Legal Services Within Any

Institutional Framework Which Adequately

Protects Clients From Injury. The Implemen

tation of This Eight Is Wholly Consistent With

the Fulfillment of the Mission of the Canons of

Ethics and the Eecognition of New Legal Forms

to Meet New Legal Needs .................................. 35

Conclusion .......................................................................... 46

MOTION FOE LEAVE TO PAETICIPATE IN

OEAL AEGUMENT ..................................................... 47

T a bm oe Cases

Cases:

Bates V. Little Bock, 361 U. S. 516 (1960) ...................... 39

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia State

Bar, 377 U. S. 1 (1964) ..............................8,15,21, 26, 27,

33, 34,37, 38

Fenster v. Leary, N. Y. (Court of Appeals,

July 7, 1967) .................................................................. 41

Gideon'v. Wainwright,272TJ. S. 335 (1963) .................. 10

Griswold V. Conn., 381, U. S. 479 (1965) ................ 39,41,42

Gunnels v. Atlanta Bi^r, 191 Ga. 366, 12 S. E. 2d 602

........................................................... 20(1940)

Harrison v. United Planning Organisation, Civ.

\#2282-65 (D. C., D. C .) ................................................. 27

lU

PAGE

In re Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, 13 111, 2d

391,150 N. E. 2d 163 (1958) ......................................... 21

In re Community Action for Legal Services, Inc., 26

App. Div. 2d 354, 274 N. Y. S. 2d 779 (1966) ............. 28

In re Community Legal Services, Inc., #-4968, Common

Pleas # 4 (March Term, 1966) ..................................25,28

In re Gault, 387 II. S. 1 (1967)......................................... 10

In re Maclub, 295 Mass. 45, 3 N. E. 2d 272 (1936) ....... 16

Jones V. Roanoke Valley Legal Aid Society, #8986

(Hustings Ct., Eoanoke, 1967) .......................... ......... 28

Matter of Pinkert, #299 (App. Div., 4th Dept. June

29, 1967) .......................................................................... 28

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 IT. S. 184 (1964) ...............39,40

Meyer v. Nebraska, 272 U. S. 390 (1923) ..............39,40,42

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 437 (1966) ...................... 10

NAACP v. Button, 371 H. S. 415 (1963) .....8,19, 26, 27,33,

35, 36, 37

People ex rel. Chicago Bar Association v. Chicago

Motor Club, 362 111. 50, 199 N. E. 1 (1935) ............... 16

People ex rel. Courtney v. Association of Real Estate

Taxpayers, 354 111. 102, 187 N. E. 823 (1933) ........... 17

Schware v. Board of Law Examiners, 353 TJ. S. 232

(1957) ............................................................................. 40

Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U. S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1872) .... 39

Stanislaus Co. Bar v. California Rural Legal Assist

ance, #93302 (Superior Ct., Stanislaus Co. (1967)) 28

IV

PAGE

Touchy V. Houston Legal Foundation, Doc. #4636 (Ct.

Civ. App. 1967) ............................................................ 28

Trautman v. Shriver, #66-188-ORL Civil (D. C., M. D.

F la .) ................................................................................. 28

United Mine Worhers, District 12 v. Illinois State

Bar Association, 33 111. 2d 112, 219 N. E. 2d 503

(1966) .................................................................. 8,27,37,43

Vitaphone Corp. v. Hutchinson Amusement Co., 28 P.

Supp. 526 (D. Mass. 1939) ......................................... 17

Constitutional and Statutory P rovisions

Provisions:

TJ. S. Const., Amend. I ................................................... 45

TJ. S. Const., Amend. XIV ............................................. 38

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, 78 Stat. 253-266

(1964) .............................................................................. 11

Civil Eights Act of 1964, Title II, 78 Stat. 243 (1964) .... 11

Economic Opportunity Act, 75 Stat. 516 (1964) ........... 28

Int. Rev. Code of 1954 §104............................................. 13

Other Sources

Sources:

American Bar Associiltion, Informative Opinion of the

Committee on Unauthorised Practice of the Law,

36 A. B. A. J. 677 (1950) ......................................... 20,43

PAGE

American Bar Association, Standing Committee Un-

anthorized Practice of the Law, Current Report, 32

U natjthorized P ractice N ews 56 (1966) .............. 34,47

Cahn and Cahn, The War on Poverty: A Civilian

Perspective, 73 Yale L. J. 1317 (1964) ........................ 24

California State Bar Association, Committee on Group

Legal Services, Group Legal Services, 39 Cal. State

B. J. 639 (1964) ....................................... 14,15,16,18, 21, 23

Carlin, L awyers E thics (1966) ...................................... 31

Carlin, L awyers o h their Owh (1962) .......................... 31

Carlin and Howard, Legal Representation and Class

Justice, 12 IJ. C. L. A. L. Kev. 381 (1965) ................ 11,12

Cheatham, A Re-evaluation of the Canons of Profes

sional Ethics, 33 T en h . L. Rev. 129 (1966) ................ 34

Comment, Neighborhood Law Offices: The New Wave

in Legal Services for the Poor, 80 H arv. L. Rev. 805

(1967) .......................................................................12,13,24,25

Comment, Participation of the Poor: Section 202(a) (3)

Organizations Tinder the Economic Opportunity Act

of 1964, 75 Yale L. J. 599 (1966) .............................. 32

Cox, Poverty and the Legal Profession, 54 Tt.t,. B. J .

12 (1965) ............................................................................... 14

Derby, Unauthorized Practice of Law, 54 Cal. L. R ev.

1331 (1966) ........................................................................... 17

Masotti and Corsi, Legal Assistance for the Poor, 44

J. U rban Law 438 (1967) ................................................10,12

McCalpin, A Revolution in the Law Practice, 15 Clev.-

Mar. L. R ev. 203 (1966) .................................................... 26

McCloskey, Economic Due Process and the Supreme

Court—An Exhumation and Reburial, 1962 S. Cx.

R ev. 34 (1962) .............................................................. 41

VI

PAGE

New York Times, August 7, 1967, p. 11, col. 1 (late

city ed.) .......................................................................... 12

Office of E conomic Oppoetunity, F iest A nnual E e-

POET OF THE LbQAL SeEVICES P eOGEAM TO THE A mEEI-

CAN Bae A ssociation (1966) ...............................24,30,45

Office of E conomic Oppoetunity, Legal Seevices P eo-

geam Guidelines (1966) ..................................... 24,26, 28,30

Office of E conomic Oppoetunity, National Confbe-

ENCE on Law and P oveety (1965) ............................24, 31

Office of E conomic Oppoetunity, T he P ooe Seek

J ustice (1967) .............................................................. 24

Parker, The Relations of Legal Service Programs with

Local Bar Associations, in Office of E conomic Op

poetunity, National Confeeence on Law and P ov

eety (1965) ......................................................................... 29,31

Pye, Bole of Legal Services in the Anti-Poverty Pro

gram, 31 Law and Contemp. P eob. 211 (1966) .......... 9

Eeisler, Legal Services for All—Are New Approaches

Needed?, 39 N. Y. S. B. J. 204 (1967) ...................... 43,44

Silverstein, A Change of Pace Conference on Legal

Services (August 6, 1967) ............................................. 10

Sparer, The Welfare Client’s Attorney, 12 IJ. C. L. A.

L. R ev. 361 (1965) ....................................................... 11

State Bar of California Reports, May-June, 1967, p. 1,

col. 1 ..................... 33

ten Broek, California’s Dual System of Family Law,

16 Stan. L. R ev. 25fr, 900 (1964) ................................ 11

U nited States Depaetmbnt of H ealth, E ducation

AND W elfaee, Confeeence P eoceedings: T he E x

tension OF Legal Seevices to the P ooe (1964) ....24, 25

vu

PAGE

Utton, The British Legal Aid System, 76 T ale L. J.

371 (1966) ...................................................................... 42

Verbatim Proceedings, Meeting of the New Haven

County Bar Association, November 16, 1964 ........... 29

Winkler, Legal Assistance for the Armed Forces, 50

A. B. A. J. 451 (1964) .......................... ...................... 18

Zimroth, Qrouy Legal Services and the Constitution,

76 Yam; L. J. 966 (1967) ..................................... 16,38,44

I n the

Olourt at

October T erm, 1967

No. 33

U nited Min e W orkers, D istrict 12,

Petitioner,

Illinois State Bar A ssociation, et al.

on writ of certiorari to the supreme court op ILLINOIS

M otion for Leave to F ile B rief Amicus Curiae

Movants NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and the National Office for the Eights of the Indigent,

respectfully move the Court for permission to file the at

tached brief amicus curiae and assign the following reasons.

During the past thirty years, the legal profession has

come to recognize that its goal of providing all Americans

with adequate legal representation cannot he achieved

through exclusive reliance upon the traditional attorney-

client relationship. In some instances, clients in need of

legal assistance are totally indigent, and cannot afford to

hire a lawyer. In others, clients are indigent in the sense

that they cannot possibly afford to pay the legal fees

charged in a complex case. In still other instances, clients

who can afford counsel cannot find an attorney willing

to handle their cases, because their causes are unpopular

(as in civil rights litigation in the deep South).

The incorporation of petitioner Legal Defense Fund

twenty-eight years ago was one of the earliest reactions

to the newly recognized need for new forms of legal service.

The Fund employs a staff of over twenty lawyers who

represent Negroes all over the nation in cases involving

equal opportunities in education, employment, housing,

and economic security, as well as in criminal cases. Its

salaried lawyers receive no fees from its clients; the Fund’s

budget is derived primarily from private donations.

Last year the Fund established as a separate corpora

tion movant National Office for the Eights of the Indigent

(NOEI) as another response to the manifest need for legal

services which cannot be satisfied by private practitioners

alone. I t too is an association employing salaried attor

neys, and its income is provided initially by a grant

from the Ford Foundation. NOEI is cooperating with

lawyers in both urban and rural areas to assist the poor

in individual cases and at the same time to suggest to

appellate courts the need for changes in legal doctrines

which unjustly affect the poor. NOEI is currently involved

in cases concerning public welfare, urban renewal, public

housing, garnishment rules, and consumer frauds. I t works

closely with attorneys in neighborhood legal offices estab

lished under the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964. These

offices represent still ^nother attempt to expand legal ser

vice so that everyone in need of counsel may have it.

Many of the experiments providing new forms of legal

service described in Section II of the appended brief

(pp. 14-26) can be described as forms of “group legal

service.” Yet such services are often deemed unethical by

state and local bar associations. The present case is a

typical instance in which an attempt to provide a large

number of persons with inexpensive legal assistance is

being stifled by a state bar association. The legal doctrine

announced by the Illinois Supreme Court, we submit (brief,

pp. 26-34), threatens not only the effort of the Mine

Workers Union to help solve some of the legal problems of

its members, but jeopardizes, to a greater or lesser extent,

all these experiments in group service. Our own opera

tions, the neighborhood law office programs funded by the

federal government, and of course the more classic forms

of group legal service (such as that established by the

Mine Workers)—all are threatened by this doctrine.

And even were the Illinois Court’s doctrine definitively

restricted to the latter category of service, a major objec

tive of the Legal Defense Fund and NORI—the extension

of legal service to all Americans who need it—^would be

severely retarded. Reaching the objective of adequate legal

services for all is an enormous undertaking requiring not

one, or ten, but perhaps thousands of experiments in group

legal services. To the extent doctrines which cripple this

necessary experimentation are allowed to flourish, the

Legal Defense Fund’s and NORI’s objectives are frus

trated. Therefore, we respectfully submit that the views

of movants may he of interest to the Court.

We have asked permission of the parties to file this brief

amicus curiae; counsel for petitioner consented but coun

sel for respondents Illinois Bar Association et al. refused.

W herefore movants pray that the attached brief amicus

curiae be permitted to be filed with this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack GtREekberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Melytk Zare

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and the National Office for

the Bights of the Indigent

J ay H. T opkis

Of Counsel

I n the

Olourt of tlfie

October T erm, 1967

No. 33

U nited Mine W orkers op A merica, D istrict 12,

Petitioner,

— v̂.—

I llinois State Bar A ssociation et at.

on writ op certiorari to the supreme court op ILLINOIS

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

Statem ent o f the Case

For many years, the Mine Workers Union has employed

a licensed attorney, who represents members and their

dependents, if they so desire, in Workmen’s Compensation

cases. The attorney is paid $12,400 per year by the Union,

and receives no additional fees from the members he rep

resents. Members are free to employ outside counsel if

they prefer. Among the conditions of the attorney’s em

ployment by the Union is the stipulation that “you will

receive no further instructions or directions and have no

interference from the District [Local] nor from any officer.

6

and your obligations and relations will be to and with only

the several persons you represent.” The attorney seeks to

achieve settlements fair and acceptable to the claimants;

when he cannot reach such a settlement with the company,

he represents his client before the Industrial Commission

of Illinois. The worker receives the full amount of the

settlement or award.

The Illinois State Bar Association alleged that this pro

cedure constituted the unauthorized practice of law by

the Union, and secured an injunction from the circuit court

of Sangamon County restraining the Union’s continued

employment of the attorney to represent individual mem

bers. The Union unsuccessfully contended there and in the

Illinois Supreme Court that its activities are constitution

ally protected.

Summary o f Argum ent

In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that

most Americans are not receiving the legal services they

vitally need. We have begun to recognize that just as all

of us need routine medical care, legal assistance is also

a routine need in a complex society. Persons in every

bracket, from the very rich to the very poor, have this

need, yet very few can afford the legal help they need,

given the high demand for lawyers, the small supply, and

the prevaihng method, of providing and paying for legal

services (pp. 9-14). |

Elements in the leg^l profession have responded to this

challenge by devising many new forms of service. The

new forms both lower the costs of service by incorporating

economic efficiencies and spread the costs among members

of groups so that no staggering costs fall upon a single

unfortunate individual. Today’s experiments in providing

legal service parallel recent changes in the provision of

medical service. Among the types of programs that might

be included in the term “group legal service” are club legal

services, legal insurance, institutions providing legal ser

vice to further a public cause, legal services as fringe

benefits of employment or union membership, and neighbor

hood law offices for the poor (pp. 14-26).

But some state and local bar associations, motivated

perhaps by the unwarranted fear that new forms of ser

vice wiU bring about a reduction in the number and amount

of lawyers’ fees, have charged many of these experiments,

both in and out of court, with the “unauthorized prac

tice of law.” They have succeeded in closing down many

of the programs, and in deterring the establishment of

others. Even some of the neighborhood legal offices founded

by the Federal government have been attacked. Although

only a few of these offices have actually been closed by

these attacks, their functions have been effectively re

stricted by pressure from the bar. And although the Illinois

Supreme Court’s opinion places aid to indigents in a sep

arate category from group services, we shall show that

this distinction is unreasoned; it therefore has not pro

tected, and cannot protect, such assistance from attack

(pp. 26-34).

The attacks on most of these new experiments should

not succeed, because services like that provided members

of the Mine Workers Union are constitutionally protected.

There is a constitutional right to associate to give and

receive legal services. In addition, state-imposed restric

tions on the practice of law, in the absence of harm

8

or the real threat of harm, violate due process. States

may enforce canons of legal ethics narrowly focused upon

specific real dangers, but may not, as below, employ broad

and vaguely stated proscriptions, based on remote hypoth

eses of harm, to restrict the ways in which lawyers may

meet the public’s legal needs (pp. 35-45).

A R G U M E N T

Introduction

The essential feature of the Illinois Supreme Court’s

opinion is its theory that, except in the case of legal

services to indigents,’ the unauthorized practice of law

is committed whenever the full burden of paying for legal

services does not fall squarely upon the client aided.^ This

theory is based upon faulty reasoning and fails to take

proper account of the constitutional principles announced

in NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) and Brotherhood

of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia State Bar, 377 TJ. S. 1

(1964). Unless disapproved in the clearest terms, it could

help suppress the robust development of legal services now

taking place in the United States, a development offering,

for the first time in our history, the possibility of adequate

legal representation for all persons—regardless of eco

nomic condition. This brief will survey the dimensions of

this revolution, will show how the rigid and unthinking

’ The court’s exception lof aid to indigents is unreasoned. As will

be shown, the court’s reafeoning could be used to attack legal pro

grams aiding the poor, and in a number of states this has already

happened. See pp. 27-33, infra.

̂United Mine Workers, District 12 v. Illinois State Bar Asso

ciation, 35 111. 2d 112,117, 219 N. B. 2d 503, 506 (1966).

9

application of canons of legal ethics has served to stifle

new legal service programs across the country, and wiU

suggest a principle for accommodating the legitimate in

terests protected by the canons of ethics with the need for

new forms of legal services.

A Great Gap Exists Between the Legal Services Am eri

cans Need and the Legal Services They Can Afford Under

the Traditional Fee System .

At an earlier period in American history, it might have

been argued that only the wealthy had need of a lawyer

to assist with a civil matter. With few exceptions, only

the wealthy ever got a lawyer. The principal tasks of

the attorney centered around the sale of real property,

and persons without property to buy or sell rarely were

aware of their need for counsel. But in the twentieth

century, the routine need for legal services became manifest.

The complexity of our society has increased the occasions

of our need for legal services and has heightened our

awareness of the need. In his roles as consumer, lessee,

vendee or vendor of property, employee, tortfeasor or tort

victim, the average American frequently enters into com

plex relations which may be characterized as, or may result

in, a legal problem. He needs legal advice to recognize and

vindicate his rights and to prevent his problems from be

coming more serious. I t is now “difficult to see how any

person can attain maturity and at no time have need for

legal advice.” Pye, Bole of Legal Services in the Anti-

Poverty Program, 31 Law and Contemp. P eob. 211, 217

(1966).

10

In the area of criminal law, the increase in demand for

legal assistance has been even more dramatic. The broad

ened right to counsel established by the decisions in Gideon

V. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335 (1963), Miranda v. Arizona,

384 U. S. 436 (1966), and In re Gault, 387 U. S. 1 (1967),

has produced so many requests for aid that already over

burdened public defenders’ offices have been subjected to

unprecedented strains.

The legal profession, like the medical profession, has

been slow to adapt to the vastly increased demand for

services. We are experiencing a shortage of law schools,

of lawyers, of judges, of courts. Every court’s calendar is

severely congested. Unlike doctors, lawyers have not cre

ated categories of legal assistants with less training than

their own to administer legal first aid.® And the legal

profession has rigidly insisted upon the exclusive use of

a fee system which, together with the low supply and high

demand, has priced lawyers far beyond what the average

man can pay. Only the relatively wealthy can affiord

routinely to consult a lawyer about civil matters. In fact,

two thirds of lower class and one third of upper class

families have never employed a lawyer. Masotti and Corsi,

Legal Assistance for the Poor, 44 J. U rban Law 483, 486

(1967). And a major legal problem is like a major medical

problem: one rarely saves in contemplation of such an

event; yet should one occur, proper legal help may cost

̂Law students enrolled in Legal Aid programs are occasionally

allowed to assist in the representation of clients, but this practice

is permitted in only fourteen states. Silverstein, A Change of Pace

Conference on Legal Services, working paper presented to the 1967

American Bar Association Convention, Honolulu, Hawaii, August

6, 1967. There is no legal equivalent of the nurse, hygienist, or

other sub-doctor professional.

11

many thousands of dollars. Only the very rich can atford

a legal catastrophe.

The profession’s answers to this problem have been legal

aid to the indigent and, in some types of cases, contingent

fees. The indigent have suffered most from the unavail

ability of adequate legal assistance. The poor, in fact,

probably have more legal problems than most Americans,

since indigents often have special needs for help in the

fields of welfare,** landlord-tenant law,® civil rights,® do

mestic relations,^ consumer problems,® and, of course,

criminal law. Legal aid societies have never adequately

̂The poor often need lawyers to help avail themselves of their

rights under the Social Security Act and state welfare laws. Rights

are often denied because welfare procedures are much too slow,

clients are arbitrarily cut olf, and state programs are administered

in a way which violates statute and constitutional law, or because

of human failure on the part of the administrators. Under the

laws, clients have a right to a hearing on any claims they have,

but a hearing is a meaningless device to an uneducated indigent

without benefit of counsel. See Sparer, The Welfare Client’s A t

torney, 12 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 361 (1965).

® Victimization of poor tenants by landlords is not uncommon.

But a tenant whose landlord is violating a building code or who

is evicting him improperly has no adequate remedy unless he has

legal help. See Carlin and Howard, Legal Representation and

Class Justice, 12 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 381 (1965).

®A person aggrieved by the violation of Titles II (public ac

commodations) or VII (fair employment) of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 78 Stat. 243, 78 Stat. 253-266 (1964), requires legal repre

sentation, as does one seeking enforcement of state civil rights acts

and court decrees which are resisted.

’’ The poor often have problems in this area, and Legal Aid has

traditionally been unwilling to assist them in divorce cases. Be

cause the poor have not been able to have legal assistance, our sys

tem has been described as a “dual system of family law”, ten

Broek, California’s Dual System of Family Law, 16 Stan. L. Rev.

257, 900 (1964), which discriminates against the poor by applying

different substantive rules.

® A missed payment on an installment purchase usually leads to

some legal action—sometimes a suit for repossession and accelera

tion of the balance due. Many employers fire workers whose wages

12

met the needs of the indigent, despite the dedicated ef

forts of hundreds of Legal Aid attorneys. First, the es

tablishment of legal aid offices was neither systematic nor

comprehensive. Only relatively large cities had any offices

at all; the rural and small-town poor were left unaided.

Comment, Neighborhood Law Offices: The New Wave in

Legal Services for the Poor, 80 H aev. L. E ev. 805,807 (1967).

Even the large cities were not adequately served. In 1962,

nine cities with populations over 100,000 had no legal aid

programs, and twenty-four such cities had programs

which failed to meet the minimum standards of the Amer

ican Bar Association. Masotti and Corsi, Legal Assistance

for the Poor, 44 J. U eban L aw 483, 487 (1967). Second,

the amount of money spent for legal aid was infinitesimal;

in 1963, it amounted to less than 2/10 of one per cent of

the money spent that year for all legal services in the

nation.® Id. at 487-88.

These quantitative deficiencies naturally produced qual

itative shortcomings. To reduce the potential case load to

manageable dimensions, legal aid had to set extremely

low income eligibility standards. I t had to avoid publicity

and community education, so that not too many indigents

are attached. Even a consumer with a perfect defense has no

adequate remedy unless he has legal help, and this is true also of

a consumer who wishes to avail himself of his rights against a

merchant who sold defective goods or failed to deliver. See Carlin

and Howard, supra, n. 5.

® Pour million dollars was spent for legal aid in 1963. A budget

of thirty million dollars Was required in fiscal 1967 to enable the

new neighborhood legal offices (see pp. 23-24 infra) to serve 400,000-

600,000 clients. The chairman of the American Bar Association’s

committee on legal aid has estimated that there are potentially 14

million indigent eases annually, a volume which would cost between

300 million and 500 million dollars a year if the service were per

formed by salaried attorneys. The New York Times, August 7,

1967, p. 11, col. 1 (late city ed.).

13

would know that its services were available. I t tradition

ally refused to help in certain types of cases, such as

divorces and bankruptcies, both because of limited funds

and because many communities thought of legal aid as

charity and did not wish it to assist in the vindication of

rights which were vaguely thought of as immoral. And

of course, while many talented and self-sacrificing lawyers

have worked for legal aid, the low salary and status at

tached to the position of legal aid attorney discouraged

many others from considering the position, so that often

a job requiring the talents of a superman was performed

by a mediocre attorney. Comment, 80 H aev. L. R ev. 805,

at 807-09.

One other legal service has been generally available

to a person without resources to hire an attorney. If he

happens to be a plaintiff, and his complaint happens to be

for money damages (usually in personal injury cases), a

client can normally have a lawyer prosecute the case for

a percentage of the recovery, if successful. At first glance

the contingent fee seems like low cost legal service, since the

client who has nothing may end up with a large amount

of money. Actually the contingent fee is usually a very

expensive type of legal service. The lawyer gambles on

recovery and, if successful, shares handsomely in the seem

ing windfall. But, after all, the recovery is not a windfall,

but compensation for a loss (often a loss measurable in

dollars and cents).“ The loss of one fourth to one third

of this recovery in legal fees is not one that most plaintiffs

can “afford”, even if it is one they can bear, and contingent

It may be noted that under the tax law, the recovery of dam

ages for personal injury is not “income.” Int. Rev. Code of 1954

§ 104.

Contingent fees are further inadequate as a solution because

even clients who do not prevail must pay the attorney’s disburse

ments.

14

fee arrangements should not be thought of as a solution

to the problem of inadequate legal services. And even if

it were, it is not a solution for the client who is the defen

dant in a personal injury case, or is threatened with evic

tion by his landlord, or is sued on a contract. Nor can it

help the client who needs an injunction, or a divorce, or

who wants to write a will, change his name, or appeal the

revocation of his driver’s license. Many millions of people

are not poor enough to qualify for legal aid or the as

sistance of a neighborhood legal office, yet not wealthy

enough to afford legal services they genuinely need.^ ̂ De

pending upon the complexity of the cases in which they

find themselves involved, millions or tens of millions of

Americans are “legally indigent.” For them, creative ele

ments in the legal profession are developing new forms of

legal services at substantially lower cost.

n.

Creative Elem ents in the Legal P rofession Have Re

cently Undertaken to D evelop New Form s o f Practice to

Satisfy the M anifest Need for More P len tifu l, Efficient

and Inexpensive Legal Services.

“Group legal services” may be defined as services per

formed by an attorney for a group with a common problem,

including a group which has formed to establish a plan of

prepaid legal service, whether or not the members have a

common interest in â particular field of activity."' Read

"" See Cox, Poverty an^ the Legal Profession, 54 III. B. J. 12, 15

(1965).

This is a simplified version of the more precise definition for

mulated by the California Bar Association’s Committee on Group

Legal Services, in their report to the Association. The report is

the leading work on the subject and is published in 39 Cal. State

B. J. at 639 (1964).

15

broadly, this definition would include legal aid as a group

service, since the indigent are a definable group with com

mon problems, served by a salaried attorney. In the case

of legal aid, the services are paid for only partly by the

indigents aided, through their United Fund contributions;

the rest of society contributes the balance. Since the 1930’s,

some groups of persons not indigent in the strict sense

have experimented with plans to provide themselves with

cheaper legal services, for which they pay the entire cost.

A group service performs several functions. I t informs

the members of the group that some of their problems

may be legal ones, and that legal assistance is available.

I t may help refer them to one of a panel of attorneys.^®

But perhaps the most important function of a group ser

vice is to keep the price of legal assistance within a range

that members of the group can afford. This is generally

done in two ways: (1) by spreading the cost of services

performed over the entire group, rather than allowing it

to fall upon the member who happens to need a lawyer’s

help, and (2) by raising the volume of a particular kind of

work that the attorney performs, thus lowering the unit

cost of the work. See California State Bar Association,

Committee on Group Legal Services, Group Legal Services,

39 Cal. S tate B. J. 639, 662-67 (1964). Increased volume

and the opportunity to specialize can lower the unit cost

of work done both by a recommended lawyer who charges

a fee in each case and a salaried lawyer retained by the

group itself. In the case of a salaried attorney, however,

there may be a further reduction in the cost of service,

in that an attorney who is guaranteed a particular income

As in Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex. rel.

Virginia State Bar, 377 IJ.S. 1 (1964).

16

in a given year may be willing to accept a lesser aggre

gate amount than if he had to rely on the relatively

uncertain income that fees provided*

Early Group Services

Group legal services first became popular in the 1930’s.

They were frequently offered as one benefit of membership

in automobile clubs. In a typical instance, members paid

$10.00 annual dues to the club, and if they were charged

with a traffic offense or sued for a vehicular tort, they

could enlist the services either of an attorney on the club’s

recommended list or of their own choosing. The club took

no part in the case, but it paid the lawyer’s bill. Em

ploying reasoning similar to that of the Illinois Supreme

Court in the present case, the Supreme Court of Massa

chusetts found that to purchase in advance, for the nom

inal sum of $10, ah. the legal services that might be needed

for a year was “utterly at variance with the standards of

the legal profession, where the fee . . . is fixed by the nature

of the work performed, the skill required and the benefit

accruing to the client.” The service was enjoined. In re

Macluh, 295 Mass. 45, 50, 3 N. E. 2d 272, 274 (1936); see

People ex rel. Chicago Bar Association v. Chicago Motor

Club, 362 111. 50, 199 N. E. 1 (1935); see also Zimroth,

Group Legal Services and the Constitution, 76 Yale L. J.

966, 966-67 (1967).

** Theoretically the risk-spreading function could be performed

independently of the eostlowering function; members of a group

could insure against legal costs without seeking the services of

particular lawyers. But the California Committee on Group Legal

Services could find no insurance company which was interested in

developing a group legal insurance plan. 39 Cal. State B. J. 639

at 720 (1964).

17

Another early group service was the Association of Real

Estate Taxpayers. Twenty to thirty thousand property

owners contributed fifteen dollars each to a non-profit cor

poration which was created to bring test suits to protect

their property from forfeiture and tax sale. I t would

have cost an individual $200,000 to bring such a suit.

There, as here, the Illinois Supreme Court held that the

association constituted a lay intermediary, and declared

the arrangement illegal. People ex rel. Courtney v. Asso

ciation of Real Estate Taxpayers, 354 111. 102, 187 N. E.

823 (1933).

The Copyright Protection Bureau fared better in court.

Eight motion picture distributors organized and made

contributions to the Bureau. When the Bureau discovered

an unauthorized exhibition of a picture, its salaried legal

staff could settle or sue the exhibitor. The court costs of

the suit were charged to the aggrieved distributor, but the

lawyers’ salaries were paid by a general assessment

against all of the members. The Bureau was held not to

be engaged in the unlawful practice of law. Each member

had a right to have a legal department to bring suits, and

the “mere fact it created its agency for the above purpose

under a trade name does not involve any illegality.” Vita-

phone Corp. V. Hutchinson Amusement Co., 28 F. Supp.

526 (D. Mass. 1939). This court, unlike others, did not

even dwell on the group nature of the arrangement.^®

One author has suggested that this case is distinguishable

from the Real Estate Taxpayers ease only in that it was brought

in a federal court. Derby, Unauthorized Practice of Law, 54 Calif.

L. Rev. 1331,1357 n. 149 (1966).

18

Special Interest Groups

Were it not for tlie early cases declaring group services

unlawful, the most prevalent form of group services today

might be those organized by special interest groups whose

members have a peculiar need for legal assistance; e.g.,

automobile clubs. But the ethical rules invoked by local

bar associations have impeded the establishment of such

group services. For example in California, a large so

cial club whose members belonged to a particular ethnic

group wished to hire an attorney to assist them with

their common legal problems, especially those dealing

with naturalization or their status as aliens. This asso

ciation was prevented by opposition from the State

Bar. California State Bar Association, Committee on

Group Legal Services, Group Legal Services, 39 Cal.

State B. J. 639, 686 (1964). The California Teachers’

Association, however, does provide its members with

some of the advantages of group service. In cases in

volving the protection of professional rights, teachers may

choose their own attorneys and the association will pay

75% of the fee beyond $50 up to $750. Ibid, at 676.

The only major “professional association” offering rela

tively comprehensive legal services to its members is the

United States Army. Under a plan set up in 1943, the

Army has been providing servicemen and their dependents

with free legal advice op all civil matters, “from adoption

to wills”, other than problems dealing with military admin

istration or justice. .^Ithough the serviceman must have

a civilian lawyer to gcj to court, all assistance up to that

point is provided by the program. See Winkler, Legal

Assistance for the Armed Forces, 50 A.B.A.J. 451 (1964).

19

Defendants’ Liability Insurance

The most widespread form of group service, though

rarely thought of as such, is the legal assistance given

defendants in automobile negligence cases by their lia

bility insurers. The insurance not only protects the insured

against liability, but against the legal fees involved in

defending a suit. Typically the insurance company will

provide an attorney to defend a suit. The cost is borne by

all the members of the group of insured drivers, as a

part of the premiums paid. Public liability, defamation,

and even malpractice insurance also usually cover legal

fees.

Institutions Promoting a Cause

Institutions which seek to promote a political or social

cause through litigation typically offer a group legal ser

vice. They usually retain one or more salaried attorneys

who prosecute the cases of litigants from the groups

served, who may or may not formally be members of the

organization. Amicus NAACP Legal Defense Fund has

no membership except for its board of directors. With

its staff of lawyers and funds it raises for itself it has

provided counsel to more or less clearly defined groups;

students wishing to attend integrated schools, civil rights

workers, Negroes seeking equal opportunity for employ

ment, etc. The NAACP (a membership corporation sepa

rate and apart from the Defense Fund) is financed in

part by membership dues, in part by private contributions.

I t too has a legal staff. See N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U. S.

415 (1963). The American Civil Liberties Union is similarly

financed, and supplies counsel to litigants in selected civil

liberties cases.̂ ** Even local bar associations have offered

The Union once participated in eases principally as amicus

curiae, but now supplies counsel in 80% of its cases.

20

this type of group legal service. In 1940, the Atlanta Bar

Association established a committee to fight usurious

lenders. I t advertised that it would provide free legal

service to anyone who would sue for recovery of pajunents

made on usurious loans.^^

Corporation Fringe Benefits

Legal service as a fringe benefit of corporate employ

ment offers limitless possibilities for the extension of low

cost legal assistance to millions who need it. I t is well

known that many companies already offer this service to

their executives. In some cases, staff or retained counsel

charge the executives a discounted fee or no fee for private

services; in others, the fee is the usual fee for the service,

but is billed to the corporation.^® But just as thousands of

companies now offer prepaid medical service to all em

ployees, legal aid could be extended either in clinics staffed

by company lawyers or through recommended or completely

independent attorneys who would be paid by the companies,

perhaps charging the clients a small deductible fee. At

least one company extended this service to all of its work

ers; during World W ar II, a California defense plant em

ployed salaried lawyers to handle the personal legal

problems of its employees. The lawyers aided 3,461 em

ployees in 1944, and saved the company an estimated 15,364

man-hours. The program was terminated when the war

ended, but company officials said it had succeeded in mini-

This practice was upheld against a charge by creditors that it

was unethical. Gunnels v. Atlanta Bar, 191 Ga. 366, 12 S.E. 2d.

602 (1940).

This practice, though widespread, is officially considered un

ethical. See American Bar Association, Informative Opinion of the

Committee on Unauthorized Practice of the Law, 36 A.B.A.J. 677,

678 (1950).

21

mizing the objective and subjective effects that legal prob

lems had on workers. See California State Bar Associa

tion, Committee on Group Legal Services, Group Legal

Services, 39 Cal. State B. J. 639, 679-81 (1964).

Union Benefits

A few labor unions have devised a variety of means for

providing their members with inexpensive legal service.

This Court examined one of these plans in Brotherhood of

Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex. rel. Virginia State Bar,

377 U. S. 1 (1964). There the Brotherhood had selected,

in each region of the country, a lawyer reputed to be honest

and skillful. When a member was injured, the union would

advise him to see a lawyer and would recommend the

lawyer it had selected for that region. The member had to

pay the fee, but he was assured the assistance of an expert

in railroad injuries, and since the lawyers selected were

called upon to perform a high volume of similar work, they

charged the members somewhat less than the usual fee.̂ ®

The United Mine Workers’ plan, under attack here, seeks

to do somewhat more. The union retains its own salaried

attorney, and injured members may choose to avail them

selves of his services. This type of plan is much less costly

to the members than that of the Trainmen. Local 12 of the

Mine Workers has 14,000 members. If the attorney’s sal

ary and ofSce expenses amount to $40,000 a year, less than

$3.00 of each member’s dues is being allocated to “legal in

surance.” The Mine Workers’ plan spreads the risk of

The Brotherhood and the lawyers agreed that a contingent

fee of no more than 25% would he charged. When the plan was

originally established, workers had to pay attorneys contingent

fees of up to 50%. In re Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, 13

111 2d 391, 393,150 N.E. 2d 163,195 (1958).

22

legal fees among all its members, and reduces aggregate

costs significantly by employing a salaried lawyer.^"

Bnt even tbe Mine Workers’ plan fails to exploit the full

cost-reducing potential of group service. For two years

an affiliate of the New York Hotel Trades Council retained

a salaried lawyer to advise its members on the full range

of legal problems that confronted them as members of

society other than those arising from their employment.

Most of the work done by the attorney concerned landlord-

tenant law and wage attachments by merchants. An infini

tesimal portion of the union treasury was spent on this

project, but members felt they could consult the attorney

freely so as to avoid trouble as well as resolve conflict.

Similarly, it is “not uncommon” in California for unions to

refer members to the attorney retained by the union for

its own affairs, and to pay the fees for the first visit. One

California law firm has agreements with five unions, under

which it provides service in workmen’s compensation cases

for all members who wish it, and also gives legal advice

without charge to members with personal legal problems.

And for several years in the late 1950’s the Los Angeles

culinary industry had collective bargaining agreements

under which management paid an annual sum to a legal aid

trust fund. A panel of five lawyers gave union members

legal advice for up to one hour per civil problem and the

attorneys were reimbursed from the trust fund at the rate

of twenty dollars per/hour. Most of the problems han-

Another “single issue

York State locals of the

Union. Lay advocates on

’ service is provided memhers of the New

International Ladies Garment Workers

the union’s staff represent union members

before administrative panels in contested claims for unemployment

compensation. Union lawyers take appeals to court if necessary.

The service costs each member pennies a year; each case would cost

many hundred times that sum if handled by an outside lawyer.

23

died by the panel centered around debtor-creditor and

landlord-tenant relationships, and automobile accidents.

See California Bar Association, Committee on Group Legal

Services, Group Legal Services, 39 Cal. S tate B. J. 639,

670-75 (1964).

Legal Assistance Associations

A major recent development in the extention of legal

services is the Legal Services Program sponsored and

largely financed by the United States government’s Office

of Economic Opportunity. This program is designed to

expand the resources available to indigents by improving

on the legal aid concept. The “neighborhood law office” is a

key innovative feature. Over six hundred of these offices

have been established in communities of every size across

the nation. Unlike most legal aid offices, the neighborhood

offices are located in the residential districts they serve,

not downtown. They are therefore far more accessible to

the poor, many of whom rarely leave their neighborhoods.

They are often situated in community action centers which

offer a variety of services, so that doctors and social work

ers may easily refer to lawyers clients who do not realize

their problems are legal. The neighborhood offices employ

salaried attorneys, who attempt to convince neighborhood

residents that they are on their side, that they are their

advocates—even against government agencies. The attor

neys engage in community organization and legal education.

They give indigent clients advice on nearly all legal prob

lems, including matrimonial problems, and go to court

whenever necessary. Neighborhood offices also differ from

legal aid in that they are not reluctant to take appeals when

the client so desires. Legal aid seldom succeeded in press

ing precedent-making cases, because understaffing required

24

that nearly all cases be settled, and in those that did go to

trial, the small sums involved did not justify the expenses

of appeal. But since the neighborhood attorney sees his

role as advocate for both the client and the neighborhood

(when their interests coincide) he is less likely to discourage

an appeal. See generally Comment, Neighborhood Law Of

fices: The New Wave in Legal Services for the Poor, 80

H aev. L. E ev. 805 (1967); Ofeice of E conomic Oppoktu-

NiTY, T he P ooe Seek J ustice (1967); Office of E conomic

Opportunity, F irst A nnual E eport of the L egal Services

P rogram to the A merican Bar A ssociation (1966); U nited

States Department of H ealth, E ducation and W elfare,

Conference P roceedings: T h e E xtension of L egal Serv

ices to the P oor (1964); Office of E conomic Opportunity,

National Conference on L aw and P overty (1965). See

also Cahn and Cahn, The War on Poverty: A Civilian

Perspective, 73 Yale L. J . 1317 (1964).

While the neighborhood office is a novel concept, it is

by no means the only experimental feature of the program.

In fact, “there is no such thing as a ‘standard’ legal serv

ices program. Innovation is encouraged and is limited

only by the ingenuity of the developers of a proposal.”

Office or E conomic Opportunity L egal Services P rogram,

GumELiNEs 4 (1966). On New York City’s Lower East Side,

mobile law offices in trailers search out those so poor and

uneducated that even a neighborhood office is too far away.

Office of E conomic Opportunity, T he P oor Seek J ustice

8 (1967). And in northern Michigan, attorneys for the poor

have offices in six towns and ride circuit through areas too

sparsely populated to support their own neighborhood

offices. Office of E conomic Opportunity, F irst A nnual

iEPORT OF THE LeGAL SERVICES PROGRAM 14 (1966). In

25

Northern Wisconsin, a program called Judicare is being

tested: Indigents take their problems to any attorney, and

the government will pay the fee, which is not to exceed

80% of the State B ar’s minimum fee schedule. Preliminary

data indicate that this program costs at least 50% more

than a neighborhood office program of similar scope. Com

ment, 80 H abv. L. E ev. 805, 849 (1967).^^

Another remarkable experiment of the legal Services

Program is the use of lay advocates to assist with minor

problems. “Not every injury requires a surgeon; not every

injustice requires an attorney . . . We need what is, in ef

fect, a new profession of advocates for the poor . . . That

job is too big—and, I would add, too important—to be left

only to lawyers.” Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, in Depart

ment OP H ealth, E ducation and W elfare, Conference

P roceedings: T he E xtension op L egal Services to the

P oor (1964). The Dixwell Legal Eights Association in New

Haven, Conn., for example, employs and trains indigents to

assist their own neighbors to vindicate their rights. The lay

advocates appear for their clients in informal administra

tive hearings before Welfare Department personnel when

welfare rights have been denied. The program’s goal is to

prevent problems from becoming so complex that the serv

ices of a lawyer are required. But if a laivyer is needed,

clients are referred to the New Haven Legal Assistance

Association.

The advantages for urban areas of a salaried neighborhood

lawyer rather than Judicare have been compiled by Judge Ray

mond Pace Alexander: Judicare leaves the poor to the yellow

pages for names of lawyers; neighborhood ofBces can train spe

cialists, watch patterns of cases and bring test suits, draft legisla

tion, and provide comprehensive service. In re Community Legal

Services, Inc., :fp4968, Common Pleas # 4 (March Term, 1966).

26

Finally, the Office of Economic Opportunity contemplates

that the indigent may some day be served by groups which

they themselves form.^^ As poverty is eradicated, the in

dependently financed neighborhood offices may be gradu

ally transformed into classic group services.

III.

The Rigid Em ploym ent o f the Canons o f Ethics by

State and Local Bar Associations to Throttle These New

Form s Is Retarding Progress Toward Satisfying the

M anifest Need for Services.

In 1966, F. William McCalpin, chairman of the Ameri

can Bar Association’s Special Committee on Availability

of Legal Services, wrote that Button and Trainmen had

brought to light many apparently long existing, though

suh rosa, group legal service plans. He cited as an ex

ample the service offered its members by tlie New York

Hotel Trades Council, described in the previous section.

“Although protests have been made by some segments of

tlie organized Bar,” he wrote, “in today’s climate the ef

fect of such protestation is doubtful.” McCalpin, A Revo

lution in the Law Practice, 15 Clev.-Mab. L. Rev. 203, 205

(1966). The organized Bar has done more than protest.

The disciplinary conunittee of tlie New York Coimty Law

yers Association, by inRiating an investigation of the Hotel

Trades Council program, succeeded in closing it down.

“ If. despite the indigency of its individual members, a group

can afford to hire an attiorney. neighborhood offices may refuse to

provide free counsel: thus a means test is applied to groups as

well as individuals. Office of Ecoxoauc Oppojsrrxrxx, Lesal

i^svicES Pso«i£Air. GruJELijrES 21 .̂1966).

27

When its salaried attorney resigned to take another job,

the nnion conld not find another lawyer willing to fill the

position, given the threat of disciplinary proceedings and

possible disbarment. The Lawyers Association contended

that the group nature of the service might violate ethical

principles, and would not accept the union’s claim that

its activities were protected by the rationale of Trainmen.

The union’s regular attorney says that but for the threat

of proceedings by the Bar, filling the position would have

been very easy.

Bar opposition to programs extending legal service must

come as no surprise to this Court. In NAAGP v. Button,

the Court considered the Virginia Bar Association’s op

position, on ethical grounds, to an offer of service by the

salaried attorneys of a group promoting a cause by means

of litigation. In Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, the

Court encountered the Virginia B ar’s labeling of a union re

ferral plan as “unauthorized practice.” Despite the Court’s

opinions in those cases. Bar associations have, if anything,

intensified their attacks on group services for “unauthor

ized practice.” Bar opposition to group service for the

social club of immigrants in California is one instance.

What happened to the Hotel Trades Council is another.

The Illinois Mine Workers Case is another.

The accusation of “unauthorized practice” has even

been leveled at some of the neighborhood law office

programs sponsored by the Office of Economic Oppor

tunity. In a number of cities, bar associations have

gone so far as to challenge the programs in court. In

the District of Columbia, for example, a suit against

the legal assistance project has been pending for over

a year. Harrison v. United Planning Organization, Civ.

#2282-65 (D. C., D. C.). A temporary restraining

28

order was secured against the California Rnral Legal

Assistance Association in Stanislaus County; the order

expired, hut the Association is now defending a suit

on the merits. Stanislaus Co. Bar. v. California Rural

Legal Assistance, #93302 (Superior Ct., Stanislaus Co.

(1967)). In Houston, the courts refused to enjoin the pro

gram, finding it to be within the “charity” exemption of

Canon 35. Touchy v. Houston Legal Foundation, Hoc.

#4636 (Ct. Civ. App. 1967). A suit by four bar associa

tions is pending in Florida, Trautman v. Shriver, #66-188-

ORL Civil (D. C., M. D. Fla.), and a private attorney sued

the local program in Roanoke Valley, Va., Jones v.

Boanohe Valley Legal Aid Society, #8986 (Hustings Ct.,

Roanoke, 1967), hut recently took a voluntary nonsuit.

In other instances, courts in nonadversary proceedings

have disapproved on grounds of ethical impropriety as

pects of the programs.^^

In Onandaga County, New York, the statute permitting chari

table corporations to handle civil cases was in June, 1967, held to

preclude legal assistance from giving advice or aid in juvenile or

criminal cases. Matter of PinTcert, #299 (App. Div., 4th Dept,

June 29, 1967). Pennsylvania and New York State require chari

table corporations which propose to practice law to obtain court

approval. Community Legal Services of Philadelphia was warmly

endorsed by the Court despite objections from some members of

the bar. In re Community Legal Services, Inc., #4968 (Common

Pleas #4 , March Term 1966). But legal assistance in New York

City suffered a very serious setback when the New York Appellate

Division disapproved its cjiarter. The proposed association would

have had twenty directors: 13 lawyers and seven representatives

of the poor. This would have conformed with the requirement in

the Economic Opportunity Act that “the poor must be represented

on the board or policy-mSaking committee of the program to pro

vide legal services.” Oitfice of E conomic Opportunity Legal

Services P rogram, Guidelines 11 (1966); see 75 Stat. 516 (1964).

This was one feature of the program objected to by the court. The

attorney. In re Community Action for Legal Services, Inc., 26

court seemed to say that a program would commit unauthorized

pt^cCtice unless every member of the board of directors were an

29

In some other cities, bar groups have effectively opposed

the neighborhood law office programs without actually go

ing to court. What happened in New Haven is illustrative.

During 1963, the Legal Aid Committee of the New Haven

County Bar Association approved the plans for the forma

tion of the New Haven Legal Assistance Association,

although the issue was never formally presented to the

Bar Association in a general meeting. In 1964, as the

Legal Assistance Association was preparing to begin op

erations, it informed the Bar candidly of its plans. In an

extremely bitter meeting of the County Bar Association

on November 16, 1964, after a debate centering around

the need for the program and the concept of unauthorized

practice, the Bar Association voted to go on record “as

opposing the entire program.” V eebatim P roceedings,

Meeting oe the New H aven County B ab A ssociation, No

vember 16, 1964 (copy on tile in the Yale Law L ibrary);

see Parker, The Relations of Legal Service Programs with

Local Bar Associations, in Office of E conomic Opportu

nity, National Conference on L aw and P overty 126

(1965). The Connecticut State Bar Association subse

quently found the program consistent with the Canons of

Ethics, and the neighborhood law offices were opened, but

the county bar has continued to challenge the propriety

of the program. Defending the program before commit

tees of the County Bar Association has consumed much

of the neighborhood lawyers’ time; the program’s execu

tive director estimates that during the program’s first

App. Div. 2d 354, 361, 274 N.Y.S. 2d 779, 787-88 (1966). As a

result of this ease, New York City’s legal services program, though

approved and funded by the federal government in July 1966, is

not yet in operation (although a few neighborhoods do have

minuscule services).

30

year of operations, one third of his time was spent nego

tiating with the local bar. Thus even where legal assistance

programs prevail, ethical challenges by local bar associa

tions can have serious adverse effects on their ability to

fulfill their intended purposes.

Furthermore, although actual attacks have been spo

radic, legal assistance programs everywhere have had to

make two major concessions to the organized bar. First,

the federal program ignores the concept of “legal in

digency” i.e., of indigency in relation to the costs of a

particular case. Instead, a rigid means test is imposed.

A family of four with an income of $5200 per year may not

take advantage of the program, even if hiring a lawyer to

help them would cost several hundred or even several thou

sand dollars. In some rural areas the qualifying income

level is $2000. For a single person, the eligibility level

ranges from $1200 in rural areas to $3380 in a few cities.

Offick of E co^tomic OppoBTtrsrrx, Fmsx A sxttal B epobt

OF TTTK T.f>v\t. Sebvices P bogbam 9 (1966). Second, neigh

borhood law offices may not provide free legal advice in

eases wMeh a lawyer would handle for a contingent fee,

notwithstanding that a contingent fee may reduce signifi

cantly a much needed compensatory recovery. “The test

should be whether the client can obtain representation.”

Ottics of Ecovomc OppoBTrxrrr. L egal S ebvices P bo-

6SA3I. GrtT'FiivFS 20 (1966). These two rules assuage the

Bar's dominant concei^: that neighborhood law offices not

take business from lo êal attorneys. That concern is re-

devtod in the reasoning by which the Canons o f Ethics

and the Elino's Supijeme Cotirt j*ut programs assisting

~iadlgents~ in a special category. Enfortimately, these

Twv» rules s e v e n s limit the wnvs in which the neighbor-

31

hood law offices could help fill the unsatisfied need for legal

services at a cost that most families can afford.

I t may at first seem odd that despite the two rules limit

ing the scope of legal assistance associations, and despite

Canon 35’s specific exemption of programs aiding indi

gents, and despite the American Bar Association’s warm

endorsement of the federal neighborhood law office pro

gram, local bar groups have continued to make ethical

attacks on legal assistance to the poor in every part of

the country. But this phenomenon should not be too sur

prising. Local bar associations are often dominated by

independent practitioners whose annual profits are often

much in doubt and who fear even a slight loss of clientele

to free assistance programs. In New Haven, all of the 24

lawyers in attendance from firms of over 10 voted to sup

port the program, but single practitioners voted 111-33 to

oppose it. Parker, The Relations of Legal Service Pro

grams with Local Bar Associations, in Office of E coftomic

OppoETXjifiTY, National Confeebncb on L aw and P oveety

126, 131 (1965). See also Caelin, Lawyees on theie Own

(1962); Caelin, Lawyees E thics 23-36 (1966) (clientele of

solo practitioners and a statistical profile of the New York

County Lawyers Association). And “it is not safe to as

sume that members of the local bar or leaders of the local

bar association have any knowledge of, or sympathy for,

the cause of legal aid in its traditional form or of the

pronouncements of the American Bar Association or of the

state bar association on the subject, let alone any knowl

edge of, or sympathy for, a program of extended legal

service.” Parker, The Relations of Tjegal Service Pro

grams with Local Bar Associations, in Office of E conomic

Oppoetunity, Nationai. Confeeknce on I jaw and I’ovuety

126 (1965).

32

Further, the exception contained in Canon 35 and in

the opinion of the Illinois Supreme Court cannot really

protect service for indigents from ethical attack, for it is

founded upon no logic whatsoever. The Illinois Court

fears a possible conflict of interest which might divert a

salaried attorney’s true loyalty from his client to the union

executive board which controls his paycheck. But a

neighborhood lawyer’s hypothetical conflict of interest is not

a whit different. He is bound to serve his client, but his

salary is paid either entirely by the federal government,

or, in most cases, 90% by the federal government and

10% by a local public or private fund. And he is responsi

ble to an executive committee which hired him, an execu

tive committee perhaps more interested in questions of

legal policy than the executive board of the Mine Workers

Union. Given the rationale of the Illinois court’s opinion,

no legal assistance program can feel assured that a court

will not carry it to its logical conclusion. In fact, the

reasoning of the Illinois court threatens legal assistance

even more than it does classic group service, since typically

a member of a group plan has some control over the hired

attorneys, some voice, directly or indirectly, in how his

money is spent. By contrast, indigents have only the most

remote control, as voters in federal elections, over the op

erations of the Legal Services Program.^^ The fragility

of the exemption for programs aiding indigents is made

In addition, indigent may have a degree of control through

representatives of the poor on the programs’ policy boards, but

those representatives neeq not have voting power, much less ma

jority voting power, and in many areas the provision of the statute

requiring such representotion is not being complied with. See

Comment, Participation of the Poor; Section 202(a)(3) Organi

zations Under the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, 75 Yale

L. J. 599 (1966).

33

further evident by the obvious truth that indigents no less

than wealthy men deserve the complete loyalty of their

attorneys.

Confusion over the scope of the constitutional rights

described in Button and Trainmen has rendered vulnerable

the entire spectrum of new group services, from corporate

and union fringe benefits and facilities of private associa

tions to the neighborhood law offices sponsored by the fed

eral government. The nature of these rights must now be

clarified so that lawyers may continue the great experi

ments they have begun in expanding legal service in the

United States. Canons of Ethics inappropriate to modern

needs should not be permitted to stifle these efforts.

In 1964, a committee of the California State Bar Asso

ciation recommended that the Rules of Professional Con

duct be amended to allow, with appropriate safeguards,

the institution of group legal service plans, including plans

under which groups hired salaried attorneys, California

State Bar Association, Committee on Group Legal Serv

ices, Group Legal Services, 39 Cjvl. State B. J. 639, 723-26

(1964). A few months ago, the Board of Governors of

the California Bar “noting {Trainmen and Button] never

theless concluded that it is not in the interest of the public

or the administration of justice to apply the principles of

those decisions to legal service plans at the expense of

certain Rules of Professional Conduct. Except as they

conflict with the Supreme Court decisions, these rules will

continue to be enforced.” State B ar of California R e

ports, May-June, 1967, p. 1, col. 1. Among the reasons

given by the Board was that modification of the Rules

would be “premature” in view of the pendency of this case.

Ihid. The American Bar Association, too, is seeking

34

guidance as to the extent of the rights established by this

Court’s earlier decisions. Partially as a result of the shock

which the Association received in T ra in m e n ,it established

a Special Committee on Evaluation of Ethical Standards.

See Cheatham, A Be-evaluation of the Canons of Profes

sional Ethics, 33 Tenn. L. Rev. 129, 130 (1966). The deci

sion in this case may have even a more profound effect

than Trainmen on the availability of legal service in

America. “The crucial importance of this case cannot he

minimized. Many unauthorized practice cases have been

of vital concern to specific areas of the unauthorized prac

tice movement, but this case above aU holds the key to

how, and in Avhat manner, attorneys are to practice law in

contemporary times.” American Bar Association, Stand

ing Committee Unauthorized Practice of the LaAV, Current

Report, 32 U xauthoeized P ractice News 56, 65 (1966).

" tsir jkKised in the petitkai

atiKi. Kas Cnars dsfJiKd. Saw Bdtr A«;i_

35

IV.

There Is a Constitutional Right to Associate to Give

and Receive Legal Services W ithin Any Institutional

Fram ework W hich Adequately Protects Clients From

Injury. The Im plem entation o f This Right Is W holly

Consistent W ith the Fulfillm ent o f the M ission o f the

Canons o f Ethics and the R ecognition o f New Legal

Form s to Meet New Legal Needs.

States have a legitimate interest in protecting persons

who seek legal advice from being defrauded, from being

assisted by persons incompetent to deal with their prob

lems, and from being victimized by lawyers unable to ac

cord them their complete loyalty. The protection of these

interests has been the traditional mission of the Canons of

Ethics. But where there is no danger of injury, we submit,

potential clients have a right to associate to receive legal

services, and lawyers have a right to provide those serv

ices, regardless of whether the lawyer charges the client a

fee. The ethical rules against unauthorized practice, cor

porate practice, and lay intermediaries were not written

to harass lawyers wishing to experiment with systems of

payment other than the fee and should not be so employed

by respondents and other bar associations today. These

rules, and the valid interests they protect, are fully recon

cilable with the constitutional right to associate to bring

or defend a lawsuit.

There i$ a constitutional right to associate to bring

or defend a lawsuit.

In N.A.A.C.P. V. Button, this court reviewed a form of

group legal service perform îd by (jmu:us NAACP Le.gal

Defense Fund and the NAACP, two institutions which

36

pursue a social cause by means of litigation. In the ar

rangement to which the Court accorded constitutional

protection, the NAACP had hired a staff of fifteen Virginia

attorneys, who were paid at a per diem rate of up to sixty

dollars a day plus expenses, a sum smaller than the com

pensation ordinarily received for equivalent private pro

fessional work. 371 U. S. at 420-21. Like the Mine Work

ers, members of the NAACP received a particular kind of

legal service at a cost much lower than that which would

prevail under a fee arrangement, and they paid for it in

advance, indirectly, through payment of dues to the asso

ciation.^® I t is true that the main issue in that case was

solicitation rather than group services, and the Court read

the Virginia decree broadly as proscribing “any arrange

ment by which prospective litigants are advised to seek

the assistance of particular attorneys,” not only the plan

actually employed by the N.A.A.C.P. But the Court,

clearly aware that the attorneys were paid per diem by the

Association, see 371II. S. at 420, and that the organization

was “financing litigation,” 371 U. S. at 447 (concurring