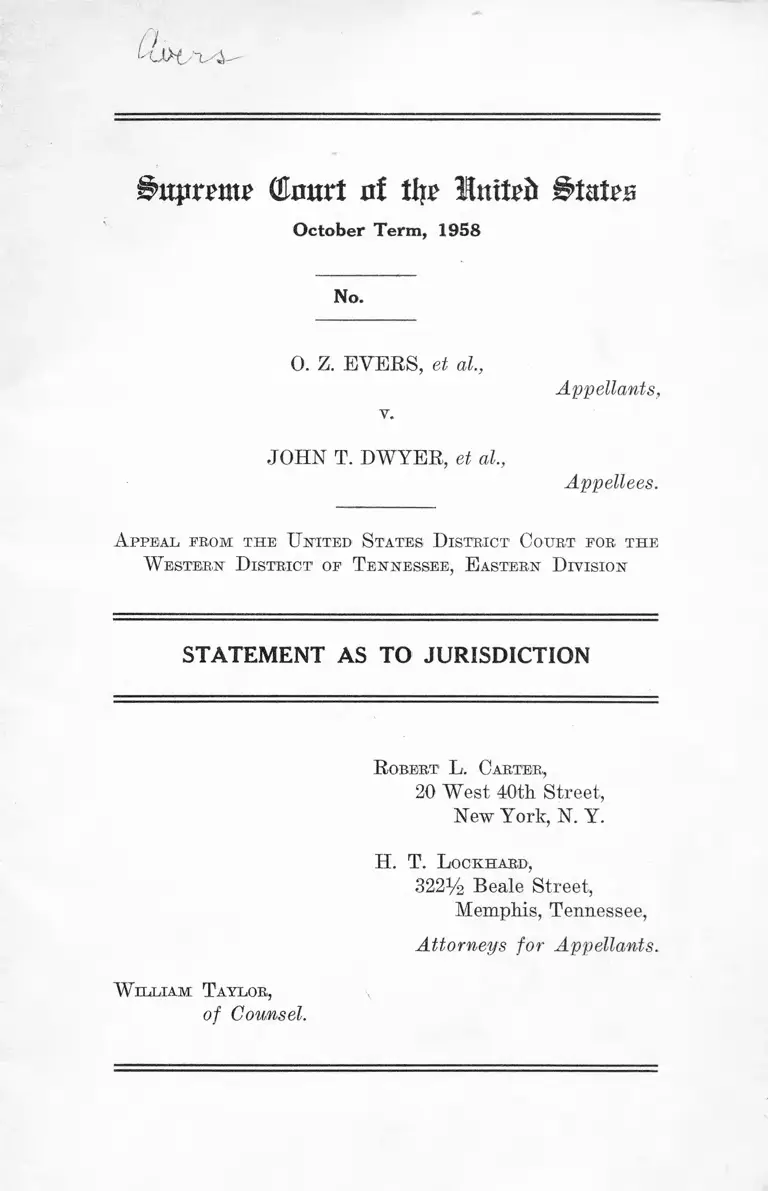

Evers v. Dwyer Statement as to Jurisdiction

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Evers v. Dwyer Statement as to Jurisdiction, 1958. e6e8155a-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ad32b5db-36c1-4d1c-9af9-6f5ff15974e2/evers-v-dwyer-statement-as-to-jurisdiction. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

aAH T «i

(tart ni % InttrJi Stairs

October Term, 1958

No.

0. Z. EVERS, et al,

Appellants,

v.

JOHN T. DWYER, et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal, from th e H otted S tates D istrict C ourt for the

W estern- D istrict of T ennessee, E astern D ivision

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

R obert L . C arter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, N. Y.

H. T. L ockhard ,

322% Beale Street,

Memphis, Tennessee,

Attorneys for Appellants.

W il l ia m T a y lo r ,

of C owns el.

I N D E X

Opinion B e lo w ............................................. .

Jurisdiction ................................................. .

Statute In volved ...........................................

Questions Presented ................................. .

Statement of the Case ............................. .

The Questions Presented Are Substantial

A. The Constitutional Question........

B. The Decision of the Court Below

Conclusion ....................................................

A ppendix I—Opinion of the Court Below

A ppendix II— Statutes Involved .............

PAGE

1

2

3

3

3

5

5

6

8

9

16

Table of Cases

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780, 787 (5th Cir.

1958) ............................................................................. 6

Baltimore City v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877 .................. 5

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ............ 2, 5

Burnes v. Scott, 117 U. S. 582, 589 ........................... 7

Doremus v. Board of Education, 342 IT. S. 429,

434-435 ........................................................................... 6

Frothingham v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447 ........................ 7

Gayle v. Browder, 352 IT. S. 903 ................................. 2, 5

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade

County, 246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957) .................. 6

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 IT. S. 879 ................................ 5

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 IT. S. 123, 152 7

11

PAGE

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 5 10 .................. 7

Stark v. Brannan, 82 F. Supp. 614 (D. C. 1949), affd.

185 F. 2d 871 (D. C. Cir., 1950), affd. 342 U. S. 451 7

Toomer v. Witsell, 334 IT. S. 385 ................................... 2

Truax v. Raich, 239 IT. S. 33 ..................................... 7

Wheeler v. Denver, 229 IT. S. 342, 351 ...................... 6, 7

Williamson v. Osenton, 232 IT. S. 6 1 9 ........................ 6

Young v. Higbee Co., 324 IT. S. 204, 214 ...................... 6

&ttprm t CSJmtrt of % Init^ States

October Term, 1958

No.

— — — — o -------------------------------

0 . Z. E vers, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

J ohn T. D w yer , et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal from th e U nited S tates D istrict C ourt for th e

W estern D istrict of T ennessee, E astern D ivision

■— -— ---------------------------------------o ----------------------------------------------------------

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

The appellant, pursuant to United States Supreme

Court Rules 13(2) and (5), files this, his statement on the

basis upon which it is contended that the Supreme Court

of the United States has jurisdiction on a direct appeal to

review the judgment of the District Court and should exer

cise such jurisdiction in this case.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the District Court has not yet been re

ported but a copy thereof appears as Appendix I to this

statement.

2

Jurisdiction

The case below was brought by appellant to secure a

declaratory judgment and interlocutory and permanent

injunctions to restrain appellees from enforcing Sections

1704-1709, Title 65, Tennessee Code Annotated on the

grounds that said statutes contravened the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States. Appellant invoked jurisdiction

under 28 U. S. C. §§ 1331 and 1343(3) (Tr. 1) and a three-

judge court was convened pursuant to 28 XL S. C. 2281

and 2284 (Tr. 24). This appeal is taken from the judg

ment of the three-judge court dismissing the action for

lack of an actual controversy.

The final decree appealed from was made and entered

on June 27, 1958 (Tr. 36). Notice of appeal was filed in

the U. S. District Court for the Western District of Ten

nessee, Eastern Division on July 23, 1958 (Tr. 37).

The Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdic

tion to review by direct appeal the judgment and decree

complained of by the provisions of 28 U. S. C. §§ 1253 and

2101(b).

The following decisions sustain the jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court to review the judgment in this case:

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Toomer v.

Wit sell, 334 U. S. 385.

Appellant also filed a notice of appeal in the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (Tr. 40).

This action was not taken because of any doubt that the

jurisdiction of a three-judge court was properly and neces

sarily invoked under Title 28, U. S. C. § 2281, but rather

because Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, decided after the

commencement of this action, may affect the substantiality

of the federal question presented to this Court. Since the

issue—whether a subsequent decision may affect the

propriety of a direct appeal to this Court from a judgment

3

of a three-judge court whose jurisdiction was properly in

voked initially—has not yet been fully clarified, appellant

filed an appeal in the Court of Appeals.

Statute Involved

Sections 1704-1709, Title 65, Tennessee Code An

notated, 1955, requiring the separation of white and

colored persons on street car lines operated in the state

of Tennessee are not set out here because of their length,

but appear in Appendix II to this statement.

Questions Presented

1. Whether Sections 1704-1709, Title 65, Tennessee

Code, 1955, requiring racial segregation on street car lines

operated in Tennessee are violative of the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment ?

2. Whether appellant Evers, a Negro resident of Mem

phis, Tennessee, against whom Tennessee statutes requiring

racial segregation have been enforced, may be barred from

maintaining an action to declare said statutes unconstitu

tional and to restrain their enforcement, on the ground

that this suit does not present an “ actual controversy!”

Statement of the Case

On June 5, 1956 appellant, a Negro resident of the City

of Memphis, Tennessee, brought this action against the

Mayor and Commissioners of Memphis, the Chief of Police

and two police officers of Memphis, the Memphis Street

Railway Company and the operator of one of the Com

pany’s buses. Appellant sought a declaratory judgment

that Title 65, Sections 1704-1709, Tennessee Code anno

tated, requiring segregation of white and Negro passen

gers on street car lines operated in the State of Tennessee,

4

was unconstitutional in that it offended the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and inter

locutory and permanent injunctions restraining the en

forcement of these statutes (Tr. 6, 7). The suit was

brought as a class suit under Rule 23a of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure on behalf of appellant Evers and all

other Negroes similiarly situated.

In the complaint, appellant alleged that on April 26,

1956, he had boarded a bus operated by appellee rail

way company and had taken a seat normally reserved for

white persons, that he had been ordered to move by the

bus driver but refused to do so, that the driver summoned

two policemen who advised appellant that he was violat

ing state law and ordered him to move to the rear of the

bus, leave the bus, or be arrested and that he elected to

leave the bus (Tr. 4, 5).

All of the appellees admitted the substantial accuracy

of these allegations (Tr. 10, 15, 21, 22), and on November

27,1956, amotion for summary judgment was filed (Tr. 25).

Hearing on the merits of this cause was held before a

three-judge court on January 6,1958, nineteen months after

the commencement of this action. At the hearing, counsel

for appellees elicited from appellant the statements that he

had used the public transportation facilities of Memphis

only on the occasion described in his complaint (Tr. 117),

that he owned an automobile (Tr. 117), and that he was

not personally bearing the expenses of this action (Tr. 112,

118). Upon these statements, and evidence that appellant

was employing a roundabout means of reaching his as

serted destination (Tr. 150-153) appellees based a motion

to dismiss.

On January 11, 1958, a further hearing was held to

allow the intervention of the Governor and Attorney Gen

eral of Tennessee. The Governor and Attorney General

appeared by their attorneys, adopted all the defenses

presented by the other appellees and submitted briefs in

support of these defenses (Tr. 326).

5

On June 27, 1958, the court below entered an order dis

missing the complaint on the ground that no actual con

troversy was presented for decision and that appellant

had suffered no legal injury, basing this decision upon the

facts brought forth at the January 6 hearing.

On July 23, 1958, appellant filed notice of appeal to this

Court (Tr. 37) and to the Court of Appeals (Tr. 40).

The Questions Presented Are Substantial

A . The Constitutional Question.

In a series of decisions rendered since 1954, this Court

has held that all forms of publicly sanctioned or enforced

racial segregation are repugnant to the guarantees of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Broivn v. Board of Education,

347 TJ. S. 483; Baltimore City v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877;

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879; Gayle v. Browder, 352

TJ. S. 903. Gayle v. Browder applied this principle to public

transportation, the field here involved.

But in several areas, state and local officials have

sought to avoid the effect of these decisions by employing

various colorable legal stratagems. In some cases these

devices have delayed or nullified the enjoyment by Negro

citizens of their rights to unsegregated public facilities.

In this case, it is submitted, the court below erroneously

sanctioned a principle which, if sustained, will be used to

further frustrate and postpone the vindication of these

constitutional rights.

Appellant Evers’ constitutional right to unsegregated

public transportation facilities and the rights of those

similarly situated can no longer be doubted. Gayle v.

Browder, supra. Unless the court below was correct in

concluding that appellant Evers had no standing to main

tain this action, it was under obligation to enter an order

vindicating the right to the use of public transportation

facilities on a non-discriminatory basis.

6

B. The D ecision o f the Court B elow .

The crux of the trial court’s decision is a finding that

appellant Evers did not really bring the suit in order to

obtain for himself unsegregated public transportation, but

rather for some other ulterior motive. From this finding,

the court draws the legal conclusions that appellant did

not suffer “ legal injury” sufficient to give him standing

to sue and that no ‘ ‘ actual controversy ’ ’ was presented. The

finding, in turn, rests upon evidence that (1) appellant only

used the transportation facilities of Memphis on one occa

sion ; (2) appellant owns his own automobile.

At the outset, one may question whether any logic

supports the findings the trial court drew from this evi

dence. Surely the court did not intend to suggest that in

order to acquire standing to sue, appellant had either to

subject himself on a regular basis to the segregated seat

ing arrangement he found obnoxious or else submit to

multiple arrests for attempting to violate state law.1 And

the court could hardly have meant to hold that owners of

automobiles never have occasion to use a city’s public

transportation system and thus have no “ interest” in it.

But even if it be conceded, arguendo, that these facts

afford a basis for doubting appellant’s motive in bringing

this suit, dismissal was not proper. For, where a plaintiff

adduces facts sufficient to bring him within the jurisdiction

of the court and entitle him to relief, his motives in bring

ing the action are entirely irrelevant. Dor emus v. Board

of Education, 342 U. S. 429, 434-435; Young v. Higbee Co.,

324 U. S. 204, 214; Wheeler v. Denver, 229 U. S. 342, 351;

Williamson v. Osenton, 232 U. S. 619.

1 It is even doubtful that appellant had to violate the law and

subject himself to possible arrest at all in order to acquire standing

to sue. Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780, 787 (5th Cir., 1958) ;

cf. Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County, 246 F. 2d

913 (5th Cir., 1957).

The cases and principles cited by the court below sup

port rather than negate appellant’s right to maintain this

action. See, e.g., Frothingham v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447.

Appellant was a member of the class, i.e., Negro citizens

of Tennessee, directly affected by the statute in question;

he did not merely suffer in ‘ ‘ some indefinite way in common

with people generally” . And, appellant was not only in

danger of sustaining injury as a result of the statute’s en

forcement, but actually had sustained such injury on one

occasion. The presence of “ legal” injury cannot be

negated by a finding that, subjectively, appellant did not

feel -aggrieved by the action complained of where, as here,

appellant’s interest is created by specific provisions in the

Constitution and laws of the United States. See Joint

Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U. S.

123, 152.

This Court, in fact, has upheld the rights of action of

parties far less immediately affected by government action

than appellant here. See, e.g., Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33;

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510; Joint Anti-

Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123,

149 ff.

Unmentioned in the opinion of the court below, but

underlying its decision is the fact that appellant is not

personally bearing the expenses of this lawsuit.2 For if

appellant was incurring the expenses of this action, it would

be extremely difficult for anyone to suggest that he did not

really want for himself the relief sought. But it is well

established that the fact that others are paying the ex

penses of litigation does not impair a party’s legal interest

or standing to sue. Wheeler v. Denver, 229 U. S. 342, 351;

cf. Stark v. Brannan, 82 F. Supp. 614 (D. C. 1949), affd.,

185 F. 2d 871 (D. C. Cir., 1950), affd. 342 U. S. 451.3

2 Appellees strongly urged this point as a ground for dismissal

both in their briefs and at the hearing (Tr. 112, 118, 119, 145, 230).

3 This is the rule even when the agreement to pay expenses is

champertous. Burnes v. Scott, 117 U. S. 582, 589.

The last factor underscores the importance of the ques

tions here presented. Complainants in cases involving civil

rights are rarely in a position to bear all of the,expenses

of litigation, and almost always receive pecuniary support

from a legal aid organization or other source. If the prin

ciple enunciated by the court below is allowed to stand, all

plaintiffs who do not pay their own expenses may be sub

jected to a “ purity of motive” test not based on any

objective criteria. One more barrier to the vindication of

precious constitutional rights will have been erected.

Appellants submit that the traditional concepts of “ ac

tual controversy” and “ standing to litigate” cannot he

twisted to achieve this result.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted,

this appeal should be granted and the judgment of the

court below should he reviewed and reversed by this Court.

B obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, N. Y.

H. T. L ockhakd ,

322% Beale Street,

Memphis, Tennessee.

Attorneys for Appellants.

W illiam T aylor,

of Counsel.

9

APPENDIX I

Opinion of the Court Below

P er Cu ria m . This is a civil action brought by O. Z.

Evers, a colored citizen, against the Mayor and Commis

sioners of the City of Memphis, individually and in their

official capacities; the Chief of Police of Memphis, both

individually and officially; two police officers of Memphis;

a named employee of the Memphis Street Railway Com

pany, operator of one of its buses; and the “ Memphis

Street and Railway Company.” The complaint is based

upon the alleged violation of the rights of plaintiff and

other citizens similarly situated, as guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States, in the enforcement by defendants of Sections 1704-

1709, Title 65, Tennessee Code Annotated, 1955, requiring

the separation of white and colored persons on street-car

lines operated in Tennessee.

The charge is made that the aforementioned Tennessee

Code sections are unconstitutional, in view of the decision

of the Supreme Court of the United States in Gayle v.

Browder, 352 U. S. 903, affirming the decision of a three-

judge district court sitting in the Middle District of Ala

bama in 1956 (reported in 142 Fed. Supp. 707), generally

known as the “ Montgomery Bus Case” . The plaintiff in

sists that the doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 567,

has been entirely repudiated by the holding and pronounce

ments of the highest court in Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U. S. 483; Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v.

Dawson, 350 U. S. 877; and Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S.

879.

Plaintiff avers that, on April 26, 1956, he was ordered

by the bus operator to move from a front seat which he

occupied to the rear of the bus. He refused and, later, two

Memphis Police officers who, apparently, had been sum

moned by the bus operator, ordered him to obey, get off

the bus, or be arrested. Whereupon, he left the car. He

10

pleads that he and those similarly situated are threatened

with irreparable injury by reason of the acts of defendants

of which complaint is made, and that there is no other plain,

adequate and complete remedy other than by “ this suit for

an injunction.”

The prayer of the complaint asks that a three-judge

court, as provided for by Title 28, section 2284, United

States Code, be convened; that an injunction restraining

defendants from enforcing the sections of the Tennessee

Code cited above be granted; and that defendants be re

strained from enforcing “ any and all customs, practices,

and usages pursuant to which plaintiff or other persons

similarly situated are segregated in the street cars of the

Memphis Street and Railway Company, on the ground that

such statutes are null and void and in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.” Declaratory judgment, pursuant to sections 2201

and 2202 of Title 28, United States Code, declaring and

defining “ the legal rights of the parties in relation to the

subject matter of this controversy” is prayed.

Separate answers of the Mayor and City Commissioners

of Memphis, of the Memphis Street Railway Company and

its bus operator, and of two substituted police officers for

those officers named in the petition (who had nothing to do

with the matter) were filed; a three-judge court was law

fully designated; and the case came on for hearing before

that court on January 6, 1958.

Immediately prior to the hearing, the defendants filed

a motion for continuance on the ground that the five-day

notice required by statute (28 U. S. C., section 2284) had

not been given by the Clerk of the Court to the Governor and

the Attorney General of Tennessee. At the hearing, it was

insisted that the assembled three-judge court had no juris

diction to proceed. Technically, there was merit in this

position; but, inasmuch as the pendency of the suit and of

the date set for hearing was a matter of common knowledge

11

and must have been known by the State officials, the court

deemed it inadvisable to delay action beyond a time suf

ficient to permit the State of Tennessee to intervene. It

was ordered, therefore, that the hearing proceed, that evi

dence be introduced and recorded and arguments heard,

with the understanding that after appropriate notice had

been given the Governor and the Attorney General of

Tennessee the State could intervene and be heard; or, if the

State so elected, all evidence received at the January 6

hearing should be expunged and the proceeding started

de novo. This course was pursued by the court for the

added reason that the counsel who took the lead for plaintiff

had traveled from New York to attend the hearing and all

parties except the State were represented by counsel in

attendance. The further hearing was set for January 11

to afford opportunity for compliance with the provision of

the statute requiring five days notice.

On January 11, 1958, the Solicitor General and the

Assistant Attorney General of Tennessee appeared on be

half of the State and adopted all defenses made by the

defendant officials of Memphis. When offered the oppor

tunity, they expressed no desire to present additional proof,

but did file briefs. Indeed, the second point made in the

State’s brief is, we think, determinative of the present

case; that is to say that this action should be dismissed

for lack of an actual controversy and of a real interest in

the suit on the part of the plaintiff. The Federal Declara

tory Judgment Act provides: “ In a case of actual contro

versy within its jurisdiction, except with respect to Federal

Taxes, any court of the United States, upon the filing of an

appropriate pleading, may declare the rights and other legal

relations of any interested party seeking such declaration,

whether or not future relief is or could be sought. Any

such declaration shall have the force and effect of a final

judgment or decree and shall be reviewable as such.”

(Emphasis supplied) Title 28, section 2201, U. S. C.

12

In Maryland Casualty Co. v. Pacific Coal £ Oil Co., 312

U. S. 270, 272, 273, the Supreme Court asserted that a dis

trict court is without power to grant declaratory relief

unless an actual controversy exists. The Supreme Court

said, further, that the difference between an abstract ques

tion and a controversy contemplated by the Declaratory

Judgment Act is necessarily one of degree; that it would

be difficult—if possible—to fashion a precise test; and that

the question in each case is basically whether the facts

alleged, under all the circumstances, show that there is a

substantial controversy between parties having adverse

legal interests of sufficient immediacy and reality to war

rant the issuance of a declaratory judgment.

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, speaking

through Judge Shackelford Miller, Jr., in Walker v. Fel-

mont Oil Corporation, 240 F. (2d) 912, 916 (C. A. 6), said:

“ Although jurisdiction may exist, it does not follow that

it must be exercised. The Declaratory Judgment Act con

fers a discretion on the court rather than an absolute right

upon the litigant. Public Service Commission of Utah v.

Wycoff Co., 344 U. S. 237, 241, 243, 73 S. Ct. 236, 97 L. Ed.

291; Brillhart v. Excess Insurance Co., 316 U. S. 491, 494,

62 S. Ct. 1173, 86 L. Ed. 1620; Great Lakes Dredge & Dock

Co. v. Huffman, 319 U. S. 293, 63 S. Ct. 1070, 87 L. Ed.

1407. Federal courts should exercise their discretionary

power with the proper regard for the rightful independence

of state governments in carrying out their domestic policy.

Conflicts in the interpretation of state law, dangerous to

the success of state policies, are almost certain to result

from the intervention of lower federal courts. Common

wealth of Pennsylvania v. Williams, 294 U. S. 176, 185, 55

S. Ct. 380, 79 L. Ed. 841; Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U. S.

315, 318, 334, 63 S. Ct. 1098, 87 L. Ed. 1424. A federal court

in a declaratory judgment suit should give strong con

sideration to the public interest involved in the avoidance

of needless friction with state policies. Railroad Commis

sion of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 TJ. S. 496, 500, 61 S. Ct.

13

643, 85 L. Ed. 971; Alabama Public Service Commission v.

Southern Railway Co., 341 IT. S. 341, 350, 71 S. Ct. 762,

95 L. Ed. 1002.”

Moreover, the Court of Appeals for this Circuit, in an

opinion by Judge Potter Stewart, states: “ * * * It is well

settled, however, that accepted principles governing equi

table and declaratory relief are no less applicable where

such relief is sought under the Civil Rights Act. Giles v.

Harris, 1903,189 U. S. 475, 486, 23 S. Ct. 639, 47 L. Ed. 909;

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 1943, 319 U. S, 157, 63 S. Ct;.

877, 87 L. Ed. 1324. Federal courts have been chary of

granting declaratory or equitable relief in an area of pos

sible friction between federal and state jurisdictions.

(Citing cases).” Williams, et al. v. Dalton, et al., 231 F.

(2d) 646, 648 (C. A. 6).

The Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, in

Ex-Cell-0 Corporation v. City of Chicago, 115 F. (2d)

627, held that a party attacking the validity of a municipal

ordinance had failed to meet the required standard of

showing, not only that the ordinance was invalid, but also

that he had sustained or was in immediate danger of

sustaining some direct injury as the result of its enforce

ment; not merely that he had suffered in some indefinite

way in common with people generally. The court quoted

from the opinion of the Supreme Court in Massachusetts

v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447. See also Federation of Labor v.

McAdory, 325 U. S. 450, 463, where it was said: “ Only

those to whom a statute applies and who are adversely

affected by it can draw in question its constitutional

validity in a declaratory judgment proceeding.”

In the absence of a clear showing of an actual con

troversy and that he is genuinely being deprived of a con

stitutional right, no citizen should be privileged to obtain

from a federal court a judgment which not only declares

invalid the statutory law of a sovereign state, but also

enjoins its enforcement.

14

In the instant case, the plaintiff, a colored postal clerk

who had previously been a police officer in Cook County,

Illinois, recently came to Memphis where he worked in

the Post Office. On April 26, 1956, he boarded a Memphis

Street Railway bus and took a front seat immediately

behind the driver, who directed him to sit in the rear of

the bus, stating that the law required it because of plain

tiff ’s color. He refused to comply. The bus driver pro

ceeded to a fire station, which he entered and where he

remained for some ten minutes according to the plaintiff.

When the bus reached another corner on its route, two

police officers boarded the bus and asked what was wrong.

The driver told them that the plaintiff and another man

accompanying him had refused to move to the rear. The

officers ordered plaintiff to go to the back of the bus, get

off, or be arrested. He left the bus.

Plaintiff testified that he was coming down town to the

Post Office and had ridden in an automobile owned by a

friend whose name he could not recall to the point where

he boarded the bus. The bus which he boarded was not

headed directly toward the Post Office in the business dis

trict of the city, but in a different direction on a cir

cuitous route which required several miles’ extra travel to

reach the down-town area. He denied that in getting on

the bus on the particular day he was laying grounds for

this suit; but, on cross-examination by the City Attorney,

he admitted that he had never previously ridden a bus in

Memphis and that he had not ridden one since the incident

in question.

Plaintiff admitted further that he is the owner of an

automobile at the present time and that he owned one at

the time of the particular incident—the only occasion on

which he had ridden a bus. It is thus obvious that he was

not a regular or even an occasional user of bus transpor

tation ; that in reality he boarded the bus for the purpose

of instituting this litigation; and that he is not in the

position of representative of a class of colored citizens

who do use the buses in Memphis as a means of transpor

tation. This is, therefore, not a case involving’ an actual

controversy. Moreover, plaintiff has not suffered the

irreparable injury necessary to justify the issuance of an

injunction. In fact, his own testimony shows that he has

not been injured at all.

Accordingly, the action is dismissed.

/ s / J oh n D . M artin ,

United States Circuit Judge.

/ s / M arion S. B oyd,

United States District Judge.

/s / W illiam E. M iller,

United States District Judge.

16

APPENDIX II

Statutes Involved

E qu ipm en t and O pebating of S tbeet and

I nteeurban R ailroads

Title 65, Section 1704, Tennessee Code (1955). P or-

tions of Cab to B e S et A pabt and D esignated fob E ach

R ace.— All persons, companies, or corporations operating

any street car line in the state are required, where white

and colored passengers are carried or transported in the

same car or cars, to set apart and designate in each car or

coach, so operated, a portion thereof or certain seats

therein to be occupied by white passengers, and a portion

thereof or certain seats therein to be occupied by colored

passengers; but nothing in sections 65-1704-65-1709 shall

be construed to apply to nurses attending children or other

helpless persons of the other race. (Acts 1905, eh. 150, sec

tion 1; Shan., section 3079al; Code 1932, section 5527.)

Title 65, Section 1705, Tennessee Code (1955). P rinted

S ign to I ndicate C abs ob P arts of Cars for E ach R ace.

■—Large printed or painted signs shall be kept in a con

spicuous place in the car or cars, or the parts thereof set

apart or designated for the different races, on which shall

be printed or painted, if set apart or designated for the

white people, and it being a car so designated or set apart,

“ This ear for white people.” If a part of a car is so

designated, then this sign, “ This part of car for white

people.” If set apart or designated for the colored race,

this sign to be displayed in a conspicuous place as follows,

“ This car for the colored race.” I f any part of a car is

set apart or designated for said race, then this sign as

follows, “ This part of the car for the colored race.” (Acts

1905, ch. 1950, section 1; Shan., section 3079a2; Code 1932,

section 5528.)

Title, 65, Section 1706, Tennessee Code (1955). C on

ductor M ay I ncrease or D im in is h S pace for E ith er R ace,

or R equire Change of S eats.'—The Conductor or other

17

person in charge of any car or coach so operated upon any

street car line shall have the right at any time, when in his

judgment it may be necessary or proper for the comfort

or convenience of passengers so to do, to change the said

designation so as to increase or decrease the amount of

space or seats set apart for either race, or he may require

any passenger to change his seat when or so often as the

change in the passengers may make such change necessary.

(Acts 1905, ch. 150, section 2; Shan., section 3079a3; Code

1932, section 5529.)

Title 65, Section 1707, Tennessee Code (1955). R efusal

of P assengers to T ake S eats A ssigned by C onductor and

D esignated for T h eir R ace or L eave Car-P en alty .— All

passengers on any street car line shall be required to take

the seats assigned to them, and any person refusing so to

do shall leave the car or remaining upon the car shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction shall be fined

in any sum not to exceed twenty-five dollars ($25.00); pro

vided, no conductor shall assign any person or passenger

to a seat except those designated or set apart for the race

to which said passenger belongs. (Acts 1905, ch. 150, sec

tion 3; Shan., section 3079a4; Code 1932, section 5530.)

Title 65, Section 1708, Tennessee Code (1955). F ailure

to S et A part P ortions of Car for E ach R ace-P en alty .—

Any person, company, or corporation failing to set apart

or designate separate portions of the cars operated for the

separate accommodation of the white and colored passen

gers, as provided by sections 65-1704-65-1709, shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor and fined in any sum not to exceed

twenty-five dollars ($25.00). (Acts 1905, ch. 150, section 4;

Shan., section 3079a5; Code 1932, section 5531.)

Title 65, Section 1709, Tennessee Code (1955). S pecial

Cars for E xclusive A ccommodation of E ith er R ace.—

Nothing in sections 65-1704— 65-1709 shall be construed to

prevent the running of extra or special cars for the exclu

sive accommodation of either white or colored passengers,

if the regular cars are operated as required by sections

65-1704—65-1709. (Acts 1905, ch. 150, section 5; Shan.,

section 3079a6; Code 1932, section 5532.)