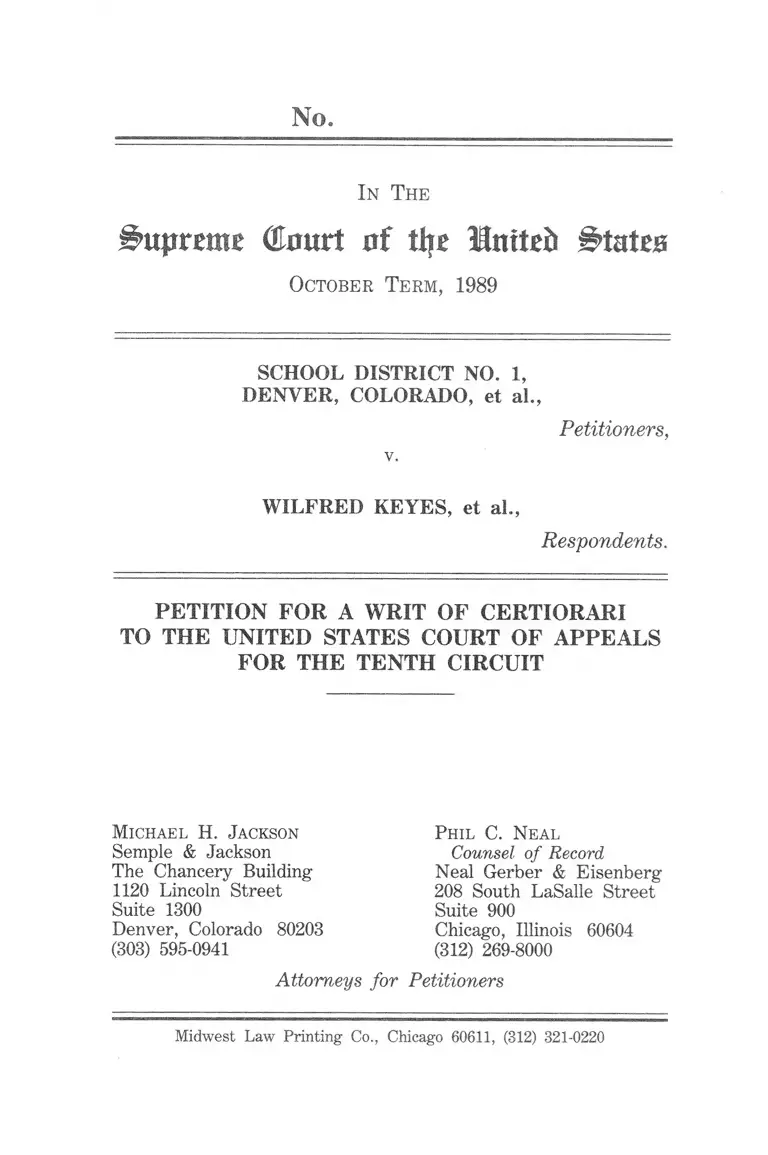

School District Denver v Keyes Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1989

144 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. School District Denver v Keyes Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1989. 047491c2-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ad458a45-edb6-4201-9262-3beff79baab8/school-district-denver-v-keyes-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

No.

In The

Supreme (£mrt o f tije MnxUb States

October Term, 1989

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1,

DENVER, COLORADO, et al.,

Petitioners,

WILFRED KEYES, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

M ic h a e l H. Ja c k so n

Semple & Jackson

The Chancery Building

1120 Lincoln Street

Suite 1300

Denver, Colorado 80203

(303) 595-0941

P h il C. N e a l

Counsel o f Record

Neal Gerber & Eisenberg

208 South LaSalle Street

Suite 900

Chicago, Illinois 60604

(312) 269-8000

Attorneys fo r Petitioners

Midwest Law Printing Co., Chicago 60611, (312) 321-0220

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether a school district that fully implemented a

comprehensive remedial plan that resulted in a racially

neutral, fully desegregated student attendance pattern,

and maintained full compliance with that plan and all court

orders relating to it for over a decade, was entitled to

be released from continuing judicial control over student

assignments.

2. Whether a district court, having decided that a

remedial student assignment plan need no longer be ad

hered to by the school district, after more than ten years

of full compliance with the plan, and having dissolved the

injunction requiring such plan, may nevertheless subject

the school district to continuing judicial control in the form

of an injunction that requires the district to maintain

racial balance in all schools of the district for an indeter

minate period of time (and perhaps permanently).

3. Whether a school district may validly be subjected

to an injunction forbidding it to operate any school that

becomes “ racially identifiable,” where no standard for

measuring “ racial identifiability” is provided and where

the districtwide average of the minority school population

has already reached more than 60 percent.

4. Whether a school district may validly be subjected to

an injunction that contains any requirement of racial bal

ance that is applicable to every school in the district and,

if not, whether any form of continuing injunction to main

tain racial balance is permissible, consistent with the Con

stitution and with the specificity requirements of Rule 65

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

11

PARTIES

The following parties are now or have been interested

in this litigation or any related proceedings:

Plaintiffs:

WILFRED KEYES, individually and on behalf of CHRISTI

KEYES, a minor; CHRISTINE A. COLLEY, individually and

on behalf of KRIS M. COLLEY and MARK A. WILLIAMS,

minors; IRMA J. JENNINGS, individually and on behalf

of RHONDA 0. JENNINGS, a minor; ROBERTA R. WADE,

individually and on behalf of GREGORY L. WADE, a minor;

EDWARD J. STARKS, JR., individually and on behalf

of DENISE MICHELLE STARKS, a minor; JOSEPHINE

PEREZ, individually and on behalf of CARLOS A. PEREZ,

SHEILA R. PEREZ and TERRY J. PEREZ, minors; MAXINE

N. BECKER, individually and on behalf of DINAH L.

BECKER, a minor; and EUGENE R. WEINER, individual

ly and on behalf of SARAH S. WEINER, a minor.

Plaintiff Intervenors:

MONTBELLO CITIZENS’ COMMITTEE, INC., CONGRESS

OF HISPANIC EDUCATORS, an unincorporated associa

tion; ARTURO ESCOBEDO and JOANNE ESCOBEDO, in

dividually and on behalf of LINDA ESCOBEDO and MARK

ESCOBEDO, minors; EDDIE R. CORDOVA, individually

and on behalf of RENEE CORDOVA and BARBARA COR

DOVA, minors; ROBERT PENA, individually and on behalf

of THERESA K. PENA and CRAIG R. PENA, minors;

ROBERT L. HERNANDEZ and MARGARET M. HER

NANDEZ, individually and on behalf of RANDY R. HER

NANDEZ, ROGER L. HERNANDEZ, RUSSELL C. HER

NANDEZ, RACHELLE J. HERNANDEZ, minors; FRANK

MADRID, individually and on behalf of JEANNE S. MA

DRID, a minor; RONALD E. MONTOYA and NAOMI R.

MONTOYA, individually and on behalf of RONALD C.

MONTOYA, a minor; JOHN E. DOMINGUEZ and ESTHER

E. DOMINGUEZ, individually and on behalf of JOHN E.

DOMINGUEZ, MARK E. DOMINGUEZ and MICHAEL J.

Ill

DOMINGUEZ, minors; and JOHN H. FLORES and ANNA

FLORES, individually and on behalf of THERESA FLORES,

JONI A. FLORES and LUIS E. FLORES, minors; MOORE

SCHOOL COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION and MOORE

SCHOOL LAY ADVISORY COMMITTEE, CITIZENS AS

SOCIATION FOR NEIGHBORHOOD SCHOOLS, an unincor

porated association, and on behalf of all others similarly

situated.

Additional Internenors:

SUSAN TARRANT, WADE POTTER, DEBORAH POTTER,

DANIEL J. PATCH, MARILYN Y. PATCH, CHRIS ANDRES,

RONALD GREIGO, DORA GREIGO and RANDY FRENCH.

Defendants:

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, DENVER, COLORADO; THE

BOARD OF EDUCATION, SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, DEN

VER, COLORADO; WILLIAM C. BERGE, individually and

as President, Board of Education, School District No. 1,

Denver, Colorado; STEPHEN J. KNIGHT, JR., individual

ly and as Vice President, Board of Education, School Dis

trict No. 1, Denver, Colorado; JAMES C. PERRILL, FRANK

K. SOUTHWORTH, JOHN H. AMESSE, JAMES D. VOOR-

HEES, JR., and RACHEL B. NOEL, individually and as

members, Board of Education, School District No. 1, Den

ver, Colorado; ROBERT D. GILBERTS, individually and as

Superintendent of Schools, School District No. 1, Denver,

Colorado; and their successors, EDWARD J. GARNER, as

President, Board of Education, School District No. 1, Den

ver, Colorado; DOROTHY GOTLIEB, as Vice President,

Board of Education, School District No. 1, Denver, Colo

rado; NAOMI L. BRADFORD, SHARON BAILEY, MARCIA

JOHNSON, TOM MAURO and CAROLE H. McCOTTER, as

members, Board of Education, School District No. 1, Denver,

Colorado; and RICHARD P. KOEPPE, Ph.D., as Superin

tendent of Schools, School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado.

IV

Defendant Intervenors:

MR. AND MRS. DOUGLAS BARNETT, individually and on

behalf of JADE BARNETT, a minor; MR. AND MRS. JACK

PIERCE, individually and on behalf of REBECCA PIERCE

and CYNTHIA PIERCE, minors; MRS. JANE WALDEN,

individually and on behalf of JAMES CRAIG WALDEN,

a minor; MR. AND MRS. WILLIAM B. BRICE, individually

and on behalf of KRISTIE BRICE, a minor; MR. AND

MRS. CARL ANDERSON, individually and on behalf of

GREGORY ANDERSON, CINDY ANDERSON, JEFFERY

ANDERSON and TAMMY ANDERSON, minors; MR. AND

MRS. CHARLES SIMPSON, individually and on behalf of

DOUGLAS SIMPSON, a minor; MR. AND MRS. PATRICK

McCARTHY, individually and on behalf of CASSANDRA

McCa r t h y , a minor; MR. RICHARD KLEIN, individual

ly and on behalf of JANET KLEIN, a minor; and MR.

AND MRS. FRANK RUPERT, individually and on behalf

of MICHAEL RUPERT and SCOTT RUPERT, minors.

V

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented ............................................... i

Parties ........................................................................ ii

Table Of Authorities ............................................... vi

Opinions Below ........................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................ 2

Constitutional Provision Involved......................... 2

Statement Of The Case ......................................... 2

Reasons For Granting The Writ ......................... 11

I. The Supervisory Injunction Upheld

By The Court Of A ppeals Is Con

trary To The Remedial Limits E stab

lished By This Court’s Decisions A nd

Is In Conflict W ith The Decisions Of

Other Circuits ....................................... 11

II. The Vagueness Of The Injunction As

Upheld By The Court Of A ppeals

Calls F or The E xercise Of This

Court’s Supervisory Power ................ 16

Conclusion ................................................................... 20

Appendices:

A—Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Tenth Circuit, January 30, 1990

B—Memorandum Opinion and" Order of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado,

June 3, 1985

C—Order for Further Proceedings of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado,

October 29, 1985

D—Memorandum Opinion and Order of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado,

February 25, 1987

E—Memorandum Opinion and Order of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado,

October 6, 1987

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page:

Dowell v. Bd. o f Educ. o f Oklahoma City PvMic

Schools, 890 F.2d 1483 (10th Cir. 1989), cert,

granted, 58 U.S.L.W. 3610 (U.S. Mar. 27, 1990)

(No. 89-1080) ................................................. 11, 12, 20

Dowell v. Bd. o f Educ. o f Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 795 F.2d 1516 (10th Cir. 1986) . . . . 13

Keyes v. School Disk No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973) .. 2

Keyes v. School Disk No. 1, 521 F.2d 465 (10th

Cir. 1975) ............................................................. 3

Keyes v. School Disk No. 1, 576 F. Supp. 1503

(D. Colo. 1983) ................................................... 3

Keyes v. School Disk No. 1, 380 F. Supp. 673

(D. Colo. 1974) ................................................... 4

Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313 (1st Cir. 1987) ..

................................................................. 8,14,15,17,19

Morgan v. Nucci, 620 F. Supp. 214 (D. Mass.

1985) 14

Pasadena City Bd. o f Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S.

424 (1976) ....................................... 9, 12, 13, 14, 16, 19

Price v. Denison Independent School District, 694

F.2d 334 (5th Dist. 1982) .................................... 17

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. o f Educ., 611 F.2d

1239 (9th Cir. 1979) ............................... 8,14,15,19

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ..............................................12,13,14,17

United States v. Overton, 834 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir.

1987) ...................................................................... 19

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254 ...........

Fed. R. Civ. P., Rule 65

2

16, 19

In The

Supreme (Enurt nf the Umteh States

October Term, 1989

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1,

DENVER, COLORADO, et aL,

Petitioners,

v.

WILFRED KEYES, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (Appendix A) is

reported at 895 F.2d 659. The June 3, 1985 opinion and

order of the district court (Appendix B) is reported at

609 F. Supp. 1491. The October 29, 1985 order of the dis

trict court is reproduced in Appendix C. The February

25, 1987 opinion and order of the district court (Appen

dix D) is reported at 653 F. Supp. 1536. The October 6,

1987 opinion and order of the district court (Appendix E)

is reported at 670 F. Supp. 1513.

—2—

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered on

January 30, 1990. The jurisdiction of this Court is based

on 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION INVOLVED

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution provides in pertinent part: “ [No State shall] deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection

of the laws.”

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case is a sequel to this Court’s decision in Keyes

v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973), which ruled

that a finding of discrimination in one geographic part of

the Denver school system gave rise to a presumption of

districtwide discrimination.1

On remand from this Court a districtwide desegrega

tion plan was ordered which, as modified by a subsequent

decision of the court of appeals, was fully implemented

in the 1976 school year. In that year, as the district court

found in the present proceedings, “ the Denver school

system [could] be considered desegregated with respect

to pupil assignments.” App. B35. As a result of the stu

dent assignment plan ordered by the court, in that school

year only one of the 119 schools in the Denver school sys

tem varied by more than a de minimis amount from the 1

1 Citations to all the reported decisions in the history of the case

are provided in note 1 of the opinion below. See App. A3. The

jurisdiction of the district court is based on 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and

1343.

—3

court’s targeted range of + 15% of the districtwide Anglo/

minority percentage.

The student assignment plan implemented pursuant to

the 1976 decree (sometimes referred to as “ the Finger

Plan” ) has remained the basic framework for the school

system ever since. The Finger Plan involved extensive

re-drawing of school boundaries, pairing of many elemen

tary schools and use of satellite zones, with busing of a

large fraction of the pupil population.2 The only changes

in the plan have been adjustments made pursuant to court

order in 1979 and 1982. The 1982 adjustments eliminated a

number of the previous pairings and created more neigh

borhood schools as well as two magnet schools. A number

of elementary schools were closed pursuant to each of the

1979 and 1982 orders.

In 1984 the school district moved that the system be

declared unitary and that the jurisdiction of the district

court be terminated. In the alternative, it moved that the

1976 decree be modified by dissolving the provisions pre

scribing student assignments.

The plaintiffs opposed the motion and countered by mov

ing for extensive further relief, including revisions in the

2 In addition to those student-assignment provisions, the decree

dealt comprehensively with facilities, faculty, transportation, extra

curricular activities, and other aspects of the district’s operations.

It also prescribed a bilingual education program. The bilingual pro

visions were eliminated by the court of appeals as not supported

by any finding of constitutional violation. 521 F.2d 465, 482-83.

Later, on the complaint of an intervening class of limited English

proficiency children, the bilingual program of the district was held

inadequate under 20 U.S.C. § 703(f). 576 F. Supp. 1503 (1983). That

ruling resulted in a consent decree, referred to as the Language

Rights Consent Decree of August 17, 1984. See Interim Decree

110, App. E8.

- 4 -

attendance plan for the purpose of correcting racial/ethnic

imbalances that had developed over the preceding years

and particularly since the 1982 revisions. App. C1-C2.

After a hearing, the court in 1985 denied the school dis

trict’s motion and ordered the Board of Education to sub

mit plans for remedying certain deficiencies found by the

court, including plans for rectifying the “ resegregation”

at three elementary schools whose Anglo percentage had

fallen to 18%, 15%, and 12% respectively.3 App. B32, C3.

While maintaining its position that further remedial orders

were not appropriate, the school district advised the court

of measures it had adopted that were intended to encour

age increased Anglo attendance at the three schools on

a voluntary basis, and it stated its opposition to any man

datory reassignments. (The measures proposed included

certain experimental curricular themes at two of the schools

and the installation of a Montessori magnet program at

the third.) The plaintiffs renewed their request for man

datory reassignments, including new pairings, to improve

racial balance at the schools in question.4

3 The total enrollment and the racial/ethnic composition of the

Denver public schools have changed materially over the years that

the Finger Plan has been in effect, as shown by the following

table:

Total enrollment Anglo enrollment %

Anglo

1973-74 87,620 49,394 56%

1976-77 61,680 30,427 49%

1983-84 51,159 20,043 39%

See 380 F.Supp. 673, 674; App. B33.

4 The other deficiencies found by the district court in its 1985

order related to distribution of teachers and administration of stu

dent hardship transfers. In response to the court’s order for plans

to address the deficiencies, the Board advised the court that it

(Footnote continued on following page)

5 -

After a second hearing, which took place two years after

the first hearing on the school district’s motion, the dis

trict court determined that no further remedial orders

were required. It authorized the Board to implement the

proposals the Board had put forward and it denied the

plaintiffs’ motion for further relief. The court further

determined (in contrast to its 1985 decision refusing to

lift or modify the injunction) that the time had come to

“ relax” judicial supervision over the school district, and

to give the Board greater independence in managing its

affairs while at the same time retaining judicial control

until such time as the court was prepared to declare the

district unitary and enter a permanent injunction. App.

D9-D13.

The district court then implemented that decision by

entering an “ Interim Decree.” That decree (1) dissolved

the original remedial decree, expressly relieving the Board

of any duty to maintain the attendance plan initially or

dered by the court as the remedy for past constitutional

violations, but (2) placed the Board under a continuing

obligation to maintain some unstated degree of racial bal

ance. Specifically, the Interim Decree provided that:

1. * * * * [The defendants] shall continue to take

action necessary to disestablish all school segregation,

eliminate the effects of the former dual system and

prevent resegregation.

2. The defendants are enjoined from operating

schools or programs which are racially identifiable as 4

4 continued

had adopted resolutions on both matters that imposed more strin

gent administrative requirements. App. D3-D4. Although the Board

contended that the district court was improperly imposing new

requirements that went beyond the original decree, neither of

these matters was contested by the Board on the appeal to the

Tenth Circuit.

6

a result of their actions. The Board is not required

to maintain the current student assignment plan of

attendance zones, pairings, magnet schools or pro

grams, satellite zones and grade-level structure.

Before making any changes, the Board must consider

specific data showing the effect of such changes on

the projected racial/ethnic composition of the student

enrollment in any school affected by the proposed

change. The Board must act to assure that such

changes will not serve to reestablish a dual school

system.

3. The constraints in paragraph 2 are applicable

to future school construction and abandonment.

* * * *

7. The defendants shall maintain programs and

policies designed to identify and remedy the effects

of past racial segregation.

* * *

12. This interim decree, except as provided herein,

shall supersede all prior injunctive orders and shall

control these proceedings until the entry of a final

permanent injunction.

App. E5-E8.

No time limit was set for the duration of the Interim

Decree nor did the court specify what steps the district

must take or what conditions it must meet in order to

be declared unitary and be released from the court’s

supervisory jurisdiction.5 The court indicated, however,

5 The court said:

The timing of a final order terminating the court’s supervisory

jurisdiction will be directly related to the defendants’ perform

ance under this interim decree. It will be the defendants’ duty

to demonstrate that students have not and will not be denied

the opportunity to attend schools of like quality, facilities, and

(Footnote continued on following page)

-7 -

that even “ when unitary status is achieved” the court’s

supervision would not be lifted until the court was “ rea

sonably certain that future actions will be free from in

stitutional discriminatory intent.” The court did not define

“ institutional discriminatory intent” but made clear that

it meant something other than “ discriminatory intent” of

the board and its members: “ [I]t is not, however, mea

sured by the good faith and well meaning of individual

Board members or of the persons who carry out the pol

icies and programs directed by the Board.” App. E5. (The

court had already indicated, however, that it considered

the Board’s declared policy for the future inadequate be

cause it did not promise to avoid “ discriminatory impact”

as distinguished from “ discriminatory intent.” See App.

B57.)

Two years prior to entry of the Interim Decree, the

school district had appealed the court’s order of June 3,

1985 refusing the 1984 motion for a finding of unitariness

or for dissolution of the student-assignment provisions.

Although that interlocutory appeal had been properly taken

under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1) from an order refusing to mod

ify an injunction, the court of appeals had postponed con

sideration of the merits of the appeal until further action

in the district court.

That further action did not come until 1987. The district

then appealed the order entering the Interim Decree. The

court of appeals consolidated the two appeals for hear

ing, heard them on January 17, 1989 and decided both 5

5 continued

staffs because of their race, color or ethnicity. When that has

been done, the remedial stage of this case will be concluded

and a final decree will be entered to give guidance for the

future.

A pp . E4.

■8-

appeals on January 30, 1990. Thus five additional years

of full compliance with the comprehensive student assign

ment plan originally ordered in 1976 have taken place

since the hearing on the school district’s initial motion for

a declaration of unitariness or termination of court super

vision over student assignments.6

The court of appeals affirmed both (1) the district court’s

1985 refusal to declare the district unitary or to grant

relief from the court’s control over student assignments

and (2) the district court’s 1987 order dissolving the 1976

decree and replacing it with the Interim Decree, except

that the court ordered minor modifications in the Interim

Decree.

As to the 1985 order, the court ruled that the district

court had been in error in concluding that a school district

could not be found unitary as to student assignments sep

arately from an overall finding of unitariness. But the

court held that that error was immaterial since the school

district, according to the court of appeals, had not chal

lenged the district court’s conclusion of “ fact” that the

“ resegregation” of three elementary schools was not caused

6 There has never been any question that the school district was

in full compliance with the student assignment plan ordered in 1976

as modified by orders of the court in 1979 and 1982. The “ resegre-

gative” effects relied on by the district court in its 1985 order

were simply effects attributed by the court to certain modifica

tions permitted by the court after hearing in 1982. There have been

no “ resegregative actions” by the school district unless actions

taken with court approval can be so described. Since the school

district has at all times been in full compliance with the court-

ordered student assignment plan, the case is an even stronger case

for unitary status than existed in Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd.

o f Edue., 611 F.2d 1239 (9th Cir. 1979) and Morgan v. Nucci, 831

F.2d 313 (1st Dist. 1987), discussed infra.

- 9

by demographic changes. App. A14.7 That “ finding” was

enough, the court thought, to support a conclusion that

the district was not unitary. In reaching that conclusion

the court of appeals entirely ignored the fact that the

district court had found that as of 1976 the Denver school

district had been fully desegregated as to student assign

ments, as well as the fact that there had never been a

failure to comply strictly with the court-ordered student

assignment plan (and the district court had found none).

App. B35.

The court of appeals also found that the district court’s

refusal to declare the district unitary even as to student

assignments was supported by the district court’s “belief’

that the district was “without the ability and without the

will to ensure that the effects of prior segregation [do]

not resurface.” App. A16.

In affirming the 1985 order, the court of appeals took

no note of the fact that the district court’s 1987 action

had undermined the district court’s own 1985 refusal to

7 The court of appeals’ observation on this point was a misreading

of the record and of the school district’s position. There was never

any issue in the district court as to whether the three schools had

become racially imbalanced as a result of “ demographic” change,

although the district court’s opinion created an impression that

such a contention had been made. The obvious fact, which was

not in dispute, was that Anglo pupils had failed to appear in the

expected numbers after the changes in assignments made by the

court-approved modifications in 1982. The school district’s primary

contention was that the court had no power, in view of this Court’s

decision in Pasadena City Bd. o f Educ. v. Spangler 427 U.S. 424

(1976), to order continuing adjustments to correct for racial imbal

ance merely because it had “ reserved jurisdiction” to do so each

time it entered an order. The court of appeals did not discuss the

school district’s argument that the principle of Spangler could not

properly be circumvented or frustrated by such a “ bootstrap”

theory.

10

find the district unitary or grant relief from the student

assignment provisions. It failed or declined to recognize

that the very fact of dissolution of the 1976 decree, and

the express determination that the school district need

no longer follow the Finger Plan, was the equivalent of

a finding in 1987 that the district had become unitary at

least as to student assignments. Instead, the court of ap

peals treated the “ Interim Decree” as in substance a

“ continuation” of the original decree (App. A20), notwith

standing that the Interim Decree itself stated that it “ su-

persede[d] all prior injunctive orders” (App. E8) and that

the district court had referred to the superseded provi

sions as “ obsolete.” App. E4.

The court declined to modify the decree’s provisions

ordering the Board to “ prevent resegregation” and for

bidding the Board to operate any schools that are “racially

identifiable.” It merely cautioned that it is not necessary

that each school must “ necessarily reflect the racial pro

portions in the district as a whole.” 8 App. A19-A21. The

court approved the Interim Decree as a commendable ef

fort to give the school district “ more freedom,” although

it expressed sympathy with the district’s “ frustration with

not knowing its precise obligations.” App. A21.

Like the district court, the court of appeals provided

no comfort as to when the “ interim” decree might end

or how the district might bring that about, saying only,

“ We recognize that the showings required to obtain uni

tariness are difficult to make. But when the district makes

those showings is entirely within its own control.” App.

A22.

8 The court of appeals did strike paragraph 4 of the Interim De

cree on the ground that it was no more than an injunction to obey

the law. App. A18. See discussion infra, pp. 18-19.

-1 1

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I. The Supervisory Injunction Upheld By The Court

Of Appeals Is Contrary To The Remedial Limits

Established By This Court’s Decisions A nd Is In

Conflict W ith The Decisions Of Other Circuits.

This case, like the Tenth Circuit’s decision in the Dowell

case, in which certiorari has been granted,9 raises funda

mental issues as to the obligations of a school board once

the remedial process of desegregation has been carried

to completion. In this case, as in its Dowell decision, the

Tenth Circuit has adopted a view of the remedial proc

ess that is irreconcilable with principles previously recog

nized by this Court, and that is also in conflict with de

cisions in other circuits.

In Dowell the issues arise in the context of determin

ing the effect to be given to an express determination

that a school district has become “ unitary” and determin

ing what standard governs the dissolution of a remedial

decree. In this case the issues arise because the district

court, although declining to declare the school district

unitary, found it appropriate to dissolve the remedial de

cree as it pertained to student assignments but then im

posed a new decree that perpetuates indefinitely the obli

gation to maintain racial balance in each of the schools

in the system.

In contrast to Dowell, no question has been raised in

this case as to the propriety of the dissolution of the re

medial student assignment plan under which the Denver

district had operated for eleven years. Thus this case

raises no question about the applicable standard for modi

9 Dowell v. Bd. o f Educ. o f Oklahoma City Public Schools, 890

F.2d 1483 (10th Cir. 1989), cert, granted, 58 U.S.L.W. 3610 (U.S.

Mar. 27, 1990) (No. 89-1080).

- 1 2 -

fying or dissolving a longstanding injunction; the law of

the case is that the dissolution has properly taken place.

The case therefore throws into even sharper relief than

the Dowell case the question of the nature of a school

district’s continuing obligations once the original remedial

order has been fully executed and a court has determined

that it need no longer be followed.

Under the teachings of this Court in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971), and in

Pasadena City Bd. o f Educ. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424

(1976), the fact that the Denver school district had reached

the point where the judicially-prescribed remedy was com

plete should have meant that the school district was en

titled to be returned to full autonomy, at least over stu

dent assignments, and that the district court could not

perpetuate its regulatory control merely by failing to pro

nounce the magic word “ unitary.” For “ having once im

plemented a racially neutral attendance pattern in order

to remedy the perceived constitutional violations,” as the

Court said in Spangler, “ the District Court had fully per

formed its function of providing the appropriate remedy

for previous racially discriminatory attendance patterns.”

427 U.S. at 436-37.

In disregard of that principle, the district court pro

ceeded to replace the original remedial decree with a new

injunction whose terms require the school board to main

tain some indeterminate degree of racial balance in the

schools for an indefinite period (and with the apparent ex

pectation on the part of the court that such an obligation

will become permanent).10

10 The district court said:

A permanent injunction is necessary for the protection of

all those who may be adversely affected by Board action. The

(Footnote continued on following page)

13

The new decree enjoins the Denver school board to

“ prevent resegregation.” App. E6, 11. It also declares

that the duty “ imposed by the law and by this interim

decree” includes the “ maintenance” of the desegregated

condition of the Denver schools. App. E6, f4. The decree

also requires the Board to consider the projected racial/

ethnic composition of each school before making any

changes in the student assignment plan, and it enjoins the

Board from operating any school that is “ racially identi

fiable.” App. E6, f2.

Such an injunction is contrary to principles established

by the decisions of this Court and of other circuits.

First, this Court made clear in both the Swann case

and the Spangler case that once the affirmative duty to

desegregate schools has been accomplished, a school dis

trict has no constitutional obligation to make continuing

adjustments of student assignments in order to preserve

racial balance, and in Spangler the Court ruled that a

district court has no power to order a school district to

do so. That ruling was made in Spangler even though the

school district had not been declared unitary. (Although 10

10 continued

Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals has recently emphasized and

repeated the admonition that “ the purpose of court-ordered

school integration is not only to achieve, but also to maintain

a unitary school system.” [Citing Dowell v. Bd, o f Educ., 795

F.2d 1516, 1520 (1986; emphasis in quote).] Resegregation can

occur as much by benign neglect as by discriminatory intent.

A beneficiary of a permanent injunction may come to court

to enforce the rights obtained in this litigation by showing that

the injunctive decree is not being obeyed.

App. D12 (emphasis added).

Interestingly, the authority cited by the Tenth Circuit in the

quoted passage was this district court’s statement in its 1985 opin

ion in the present case. See Dowell, 795 F.2d at 1520.

—14—

the reference in Swann was to “year-by-year” adjust

ments, the Spangler decision made clear that the princi

ple involved is that once a racially neutral attendance plan

has been established, a school district has no further af

firmative obligation to pursue racial balance in student

enrollments in response to changing compositions of the

schools. 427 U.S. at 436-37.)

Second, the Tenth Circuit’s approval of the notion that

a court may continue to exert some “ looser degree of con

trol” over student assignments, notwithstanding the fact

that the purposes of a remedial plan have been fulfilled

so that that plan has been dissolved, conflicts with the

decisions of the First Circuit in Morgan v. Nucci, 831

F .2d 313 (1987) and the Ninth Circuit in Spangler v. Pas

adena City Bd. o f Educ., 611 F.2d 1239 (1979).

In Morgan v. Nucci the district court had attempted

to preserve its power over student assignments in the

same manner as did the district court in this case. It

entered what it called final orders prescribing future con

duct for the Boston school board, explaining that

the final orders seek to provide assignment guidelines

for future years which are as flexible as consistency

with a workable student desegregation plan permits;

and an irreducible minimum of safeguards for insur

ing a future in which the Boston public schools may

flourish on a racially unitary, racially unidentifiable,

yet flexible and clear foundation of equal access and

equal educational opportunity for all students.

620 F. Supp. 214, 222 (D. Mass 1985).

The court of appeals for the First Circuit vacated the

district court’s order. With respect to the district court’s

effort to provide a modified injunction controlling future

student assignments the court said, “ The schools are

15

either unitary or not in respect to student assignments.”

Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d at 326. The court held that

unless new or different facts should appear on remand,

the school district should be found unitary as to student

assignments and the injunction as to student assignments

should be permanently vacated. Id.

Similarly, in Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. o f Educ.,

after the remand from this Court’s decision, the Ninth

Circuit held improper as a matter of law a district court’s

refusal, on the ground that continued monitoring was

necessary in order to prevent resegregation, to relinquish

jurisdiction over the school board. The Ninth Circuit

ordered that all injunctive orders be vacated and that the

jurisdiction of the district court over the case be termi

nated. (Again, there was no express finding that the

school district was “ unitary.” )

The decision below is in conflict with the Ninth Circuit’s

decision for the further reason that it approved as grounds

for continuance of jurisdiction reasons substantially iden

tical with those which were rejected by the Ninth Cir

cuit as insufficient as a matter of law. Thus the court of

appeals in this case upheld the district court’s order “ re

taining supervisory jurisdiction over the Denver public

schools” on the basis of the district court’s “ belie[f| that

the district was both without the ability and without the

will to ensure that the effects of prior segregation did

not resurface.” App. A16. Exactly the same kinds of justi

fication had been advanced by the district court in the

Spangler case, and the court of appeals held that such

apprehensions about the future actions of the school board

could not justify continued displacement of the board’s in

terest in “ managing [its] own affairs, consistent with the

Constitution.” 611 F.2d at 1241; see also id. at 1244-47

(concurring opinion of Kennedy, J.).

-16-

II. The Vagueness Of The Injunction As Upheld By

The Court Of A ppeals Calls For The Exercise

Of This Court’s Supervisory Power.

The very terms of the interim injunction entered by the

district court underscore the difficulties inherent in replac

ing a satisfied remedial order with some “ looser” stan

dard of judicial restraint on a school board’s discretion.

In its Spangler decision this Court reversed the court

of appeals in part because that court’s opinions had left

the school board without clear guidance as to its obliga

tions under the then-existing decree. The Court said:

Violation of an injunctive decree such as that issued

by the District Court in this case can result in pun

ishment for contempt in the form of either a fine or

imprisonment. . . . Because of the rightly serious view

courts have traditionally taken of violations of injunc

tive orders, and because of the severity of punish

ment which may be imposed for such violation, such

orders must in compliance with Rule 65 be specific

and reasonably detailed.

427 U.S. at 438-39.

In Spangler the uncertainty was due to the court of ap

peals’ ambiguous resolution of the issue whether a pro

vision of the injunction should be stricken. Here the uncer

tainty lies both in the injunction itself and from the gloss

put on it by the court of appeals.

The heart of the district court’s injunction in this case

lies in its prohibition against the existence (“ operation” )

of any schools that are “ racially identifiable” as a result

of Board actions. App. E6, 12. The prohibition is made

specifically applicable to school construction and abandon

ment. App. E6, 13. Thus the Board is forbidden from tak

-17-

ing any action that may result in any school’s becoming

“ racially identifiable.” 11

It is well recognized that the term “racially identifiable”

has no fixed meaning in school desegregation cases. See,

e.g., Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d at 319-20; Price v. Deni

son Independent School District, 694 F.2d 334, 353-64 (5th

Cir. 1982). No one has suggested any way of measuring

racial identifiability except by arithmetic ratios. Yet the

district court declined to provide the Board with any stan

dard to guide it, while putting the Board at its peril of

violating an injunction if some action of the Board were

subsequently deemed to have crossed some imaginary line

resulting in “racial identifiability.” Noting the Board’s con

cern that that term is too indefinite and “ may be con

strued to mean an affirmative duty broader than that re

quired by the Equal Protection Clause,” the district court

brushed the concern aside with the non sequitur that the

prohibition applies only to Board “ actions” that may re

sult in racial identifiability (or “ substantial dispropor-

tionality” ). App. E5.

The court of appeals declined to eliminate the provision,

or to modify it except to say that it “ should not be inter

preted to require that racial balance in any school . . .

necessarily reflect the racial proportions in the district as

a whole.” App. A21. That qualification of course does not

address the problem. The question is not whether each

school must reflect the racial proportions “ in the district 11

11 In forbidding the existence of any racially identifiable school,

as the provision clearly implies, the prohibition flies in the face

of the statement in Swann that “ the existence of some small num

ber of one-race, or virtually one-race, schools within a district is

not in and of itself the mark of a system that still practices seg

regation by law.” 402 U.S. at 26.

-18-

as a whole” (for no one would suppose that it must do

so) but what racial proportions each school must reflect.

Paradoxically, the court of appeals did order the elimina

tion of Paragraph 4 of the decree, on the ground that it

was no more than an injunction to obey the law.12 App.

A18. But an injunction to “ obey the law” is, in this case,

far more specific in its guidance than the provisions of

the injunction the court left untouched. Since the “ law”

applicable is the Fourteenth Amendment, a school board

enjoined to obey the law knows that the forbidden line

is intentional discrimination. A conscientious board knows

how to obey that law, and such an injunction puts it at

no greater peril than the Fourteenth Amendment itself.

An injunction to “ avoid racial identifiability,” with no

standard to say what that means, is as serious an impair

ment of the autonomy and discretion of a school board

in managing the educational affairs of a school district as

an injunction prescribing in detail the student assignment

plan to be followed. It means that the Board will act at

its peril whenever it takes any action that may have an

adverse impact on the racial proportions in any school in

the district. Rather than conferring freedom on the Board,

as the district court professed a desire to do, it merely

places the Board in constant peril of future judicial inter

vention in the form of contempt proceedings (as well as

12 The paragraph provided:

The duty imposed by the law and by this interim decree is

the desegregation of schools and the maintenance of that condi

tion. The defendants are directed to use their- expertise and

resources to comply with the constitutional requirement of

equal educational opportunity for all who are entitled to the

benefits of public education in Denver, Colorado.

A p p . E 6.

-1 9

continued extension of judicial control) and thus greatly

inhibits the good-faith conduct of the enterprise for which

the Board has responsibility.

An obvious reason why neither the district court nor

the court of appeals wished to make the decree more spe

cific is that, while there is no way to do so except by

providing arithmetic guidelines, such guidelines, imposed

after full implementation of a remedial plan, would clear

ly contravene this Court’s declarations that the Constitu

tion does not require any prescribed degree of racial bal

ance in the public schools. But that obstacle is not over

come by cloaking the required racial balance in the vague

test of “ racial identifiability,” leaving it to the enjoined

party to guess what the prescribed degree of racial bal

ance is. The vagueness only compounds the fundamental

substantive objection to the injunction.

Thus the vagueness that infects the new supervisory

decree in this case is more than a departure from the re

quirement of Rule 65, Fed. R. Civ. P., and this Court’s

ruling in Spangler. It is a difficulty inherent in any ef

fort to prescribe permanent or continuing obligations of

a school board once it is determined that the board need

no longer adhere to a prescribed remedial plan. This prob

lem helps make clear why the courts of appeals for the

First, Fifth, and Ninth Circuits have concluded that once

a school district has fulfilled the prescribed remedy for

a constitutional violation a district court should vacate

prior orders and relinquish its control, leaving the board

subject only to its constitutional obligation not to engage

in intentional discrimination on account of race. See

Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313; United States v. Over-

ton, 834 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1987); Spangler v. Pasadena

City Bd. o f Educ., 611 F.2d 1239.

■20-

The fundamental issue raised by the Tenth Circuit’s

decision in this case, as in its decision in the Dowell case,

is whether the measure of a school district’s obligation

to maintain a unitary system, after completion of a rem

edy for eliminating a previously discriminatory student as

signment system, is discriminatory intent or maintenance

of some prescribed (or unprescribed) degree of racial bal

ance, regardless of other educational considerations. Cer

tiorari should be granted in this case, in addition to the

Dowell case, not only because the issues in the two cases

are closely related but also because, if the example set

by this case is permitted to stand, school boards may be

subjected to the constraints of judicial supervision indefi

nitely and long after full compliance with a comprehensive

remedial plan has been maintained for many years.

The petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted.

CONCLUSION

Respectfully submitted,

M ic h a e l H. Ja c k so n

Semple & Jackson

The Chancery Building

1120 Lincoln Street

Suite 1300

Denver, Colorado 80203

(303) 595-0941

Neal Gerber & Eisenberg

208 South LaSalle Street

Suite 900

Chicago, Illinois 60604

(312) 269-8000

P h il C. N e a l

Counsel of Record

Attorneys fo r Petitioners

APPENDICES

INDEX TO APPENDICES

Page

A— Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Tenth Circuit, January 30, 1990 ___ A1

B— Memorandum Opinion and Order of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado,

June 3, 1985 ...................................................... B1

C— Order for Further Proceedings of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado,

October, 1985 .................................................... C l

D— Memorandum Opinion and Order of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado,

February 25, 1987 ............................................. D1

E— Memorandum Opinion and Order of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado,

October 6, 1987 ................................................. E l

A1

APPENDIX A

[January 30, 1990]

PUBLISH

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

TENTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 85-2814 & 87-2634

W ILFR E D KEYES, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

CONGRESS OF HISPANIC EDUCATORS, et al.,

Plaintiffs/Intervenors-Appellees,

v.

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1, DEN VER, COLORADO, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Colorado

(D.C. Civil No. C-1499)

Phil C. Neal of Neal, Gerber, Eisenberg & Lurie, Chicago,

Illinois (Michael H. Jackson of Semple & Jackson, Denver,

Colorado, with him on the brief) for Defendants-Appellants.

A2

Gordon G. Greiner of Holland & Hart, Denver, Colorado,

for Plaintiffs-Appellees (James M. Nabrit, III, New York,

New York, with him on the brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees;

Norma V. Cantu of Mexican American Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., San Antonio, Texas, and Peter

Roos, San Francisco, California, with him on the brief for

Plaintiffs/Intervenors-Appellees).

Wm. Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney General,

Roger Clegg, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, and

David K. Flynn, Attorney, Department of Justice, Wash

ington, D.C., filed a brief on behalf of the United States

as amicus curiae.

Before LOGAN, SETH and ANDERSON, Circuit Judges.

LOGAN, Circuit Judge.

This is yet another chapter in the slow and acrimonious

desegregation of Denver Public School District No. 1. In

the district court, the school district moved for a declara

tion that it had attained unitary status and for the ter

mination of this case and of the court’s continuing jurisdic

tion over operation of the schools. The court denied both

requests and later ordered the district to prepare a plan

for further desegregation of certain schools and programs

that it believed were preventing the district from attain

ing unitary status. Case number 85-2814 is the district’s

appeal from the court’s denial of its motion for termina

tion of continuing jurisdiction and from the court’s later

order. Case number 87-2634 is the district’s appeal from

the court’s order approving the district’s response but re

taining jurisdiction, and its subsequent “ interim decree”

in which the court eliminated reporting requirements and

A3

mandated certain general desegregation actions. The court

styled its “ interim decree” an intermediate step towards

a final, permanent injunction.

I

This case began in 1969 when plaintiffs, parents of chil

dren then attending the Denver public schools, sought an

injunction against the school district’s rescission of a pro

posed voluntary desegregation plan. Since that time the

parties have made many trips to the courthouse, resulting

in numerous opinions, including two by this court and one

by the full Supreme Court of the United States.1 In the

instant appeals we are concerned primarily with the dis

trict court’s actions in Keyes X IV through Keyes XVII. 1

1 See Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 303 F. Supp. 279 (D. Colo.

1969) (Keyes I), modified, 303 F. Supp. 289 (D. Colo. 1969) (Keyes

II), order reinstated, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969) (Brennan, J. in chambers)

(Keyes III); Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 313 F. Supp. 61 (D. Colo.

1970) (Keyes IV); Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 313 F. Supp. 90

(D. Colo. 1970) (Keyes V), ajfd in part and rav’d in part,, 445 F.2d

990 (10th Cir. 1971) (Keyes VI), cert, granted, 404 U.S. 1036 (1972)

and cert, denied sub. nom School Dist. No. 1 v. Keyes, 413 U.S.

921 (1973), modified and remanded, 413 U.S. 189 (1973) (Keyes

VII), on remand, 368 F. Supp. 207 (D. Colo. 1973) (Keyes VIII)

and 380 F. Supp. 673 (D. Colo. 1974) (Keyes IX), ajfd in part and

rev’d in part, 521 F.2d 465 (10th Cir. 1975) (Keyes X), cert, denied,

423 U.S. 1066 (1976); Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 474 F. Supp.

1265 (D. Colo. 1979) (Keyes XI); Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 540

F. Supp. 399 (D. Colo. 1982) (Keyes XII); Keyes v. School Dist.

No. 1, 576 F. Supp. 1503 (D. Colo. 1983) (Keyes XIII); Keyes v.

School Dist. No. 1, 609 F. Supp. 1491 (D. Colo. 1985) (Keyes XIV);

I R. Tab 29, Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, No. C-1499 (D. Colo.

Oct. 29, 1985) (Keyes XV) (Order for Further Proceedings); Keyes

v. School Dist. No. 1, 653 F. Supp. 1536 (D. Colo. 1987) (Keyes

XVI); Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 670 F. Supp. 1513 (D. Colo.

1987) (Keyes XVII).

A4

From 1974, see Keyes IX, 380 F. Supp. 673, to the pres

ent the school district has operated under a court-ordered

desegregation plan, which occasionally has been modified

with the district court’s approval. See, e.g., Keyes XII,

540 F. Supp. at 404; Keyes XI, 474 F. Supp. at 1276. In

1984 the district moved for an order declaring the Denver

schools unitary, dissolving the injunction as it related to

student assignments, and terminating the court’s jurisdic

tion in the case. Plaintiffs opposed the motion and moved

for an order directing the school district to prepare and

submit numerous plans and policies to remedy what they

considered shortcomings in the district’s desegregation ef

forts. The court held a full hearing on the motions and

later filed an opinion denying the district’s motion, but

refusing to rule on plaintiffs’ motion pending further nego

tiations between the parties. Keyes XIV, 609 F. Supp.

at 1521-22.

In its opinion, the court rejected the district’s argument,

id. at 1498, that compliance for an extended period of time

with the 1974 court-approved desegregation plan, as modi

fied in 1976, entitled the district to a declaration of uni

tariness. The court reasoned that the district’s argument

hinged on the thesis that the “ 1974 Final Judgment and

Decree, as modified in 1976, was a complete remedy for

all of the constitutional violations found in this case.” Id.

However, the court had indicated at the time of its 1976

order that further remedial changes would be necessary

in the future. Id. at 1500.

The court supported its factual finding that the district

was not unitary by placing weight on the following factors:

its recognition in 1979 and the school board’s recognition

in 1980 that the district was not yet unitary, id. at 1501;

the board’s uncooperative attitude in recent years, id. at

1505; the board’s recognition in one of its resolutions that

A5

compliance with the court-approved plan was insufficient,

in itself, to desegregate the district’s schools, id. at 1506;

the increasing resegregation at three schools, id. at 1507;

the district’s misinterpretation of the faculty/staff assign

ment policy so that the fewest number of minority teach

ers would be placed in previously predominantly Anglo

schools, id. at 1509-12; and the district’s “ hardship trans

fer” policy, which the court found was implemented with

“ a lack of concern about the possibility of misuse and a

lack of monitoring of the effects of the policy,” id. at 1514.

In addition, the court believed that the district had not

given adequate assurances that resegregation would not

occur if the court terminated jurisdiction, id. at 1515, and

that in any event, even if the board affirmatively tried

to prevent resegregation, it would be compelled to com

ply with Colo. Const. Art. IX § 8 which outlaws “ forced

busing,” compliance with which certainly would cause dras

tic resegregation of Denver’s schools. Keyes XIV, 609 F.

Supp. at 1515. Finally, the court noted that mere statistics

indicating general integration in student assignments were

insufficient to compel a finding of unitariness, id. at 1516,

and indicated that the board had neither the understand

ing of the law nor the will to contravene community sen

timent against busing that would be necessary for the

district to achieve and maintain a unitary school system.

Id. at 1519, 1520.

Following this ruling and the parties’ failure to negotiate

a settlement of their differences, the court ordered the

school district to prepare and submit a plan “ for achiev

ing unitary status . . . and to provide reasonable assurance

that future Board policies and practices will not cause re

segregation.” Keyes XV, I R. Tab 29 at 2. Specifically,

the court ordered the board to address four problem areas:

(1) three elementary schools, Barrett, Harrington, and Mit

A6

chell, that were racially identifiable as minority schools;

(2) the district’s hardship transfer policy; (3) the assign

ment of faculty; and (4) plans to implement board Resolu

tion 2233, which states the board’s commitment to opera

tion of a unitary school system. Id. at 2-3. It is from this

order and the court’s ruling in Keyes XIV that the school

district appeals in case number 85-2814.

In February 1987, the district court noted that the board

had responded positively to its order in Keyes XV, but

that the plaintiffs still had ample reason for their concerns

about the district’s ability or willingness to achieve and

maintain a unitary system. Keyes XVI, 653 F. Supp. at

1539-40. Nevertheless, the court cited the community’s in

terest in controlling its school district and decided “ that

it is time to relax the degree of court control over the

Denver Public Schools.” Id. at 1540. At the same time,

the court concluded that a permanent injunction should

be constructed, in part because one board’s resolutions

could not bind a subsequent board, and the constitutional

duty was to maintain, not simply achieve, a desegregated,

unitary school system. Id. at 1541-42.

Later in 1987, the district court issued an “ interim de

cree” that eliminated reporting requirements and allowed

the school district to make changes in the desegregation

plan without prior court approval. Keyes XVII, 670 F.

Supp. at 1515. The court attempted to fashion an injunc

tion sufficiently specific to meet the requirements of Fed.

R. Civ. P. 65(d), while at the same time allowing the board

to operate “ under general remedial standards, rather than

specific judicial directives.” Id. The court summarized its

order as enjoining “governmental action which results in

racially identifiable schools,” id. at 1516, and said its de

cree was a step towards a final decree that would termi

nate the court’s supervisory jurisdiction and the litigation’s

remedial phase. Id. In case number 87-2634, the district

appeals the court’s February 1987 order and its later “ in

terim decree.”

II

Plaintiffs assert, as an initial matter, that this court does

not have jurisdiction over case number 85-2814. Specifical

ly, plaintiffs argue that subsequent orders of the district

court have superseded Keyes XIV, and thus any appeal

from the decision is moot. In the alternative, they con

tend that the court’s “ refusal to issue a declaratory judg

ment that a defendant has complied with an injunction,”

see Joint Brief of Appellees at 1, is not an appealable in

junctive order under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1), the school

district’s asserted basis for appellate jurisdiction. In ad

dition, plaintiffs argue that the appeal from Keyes XV,

the court’s order for the district to submit certain deseg

regation plans, also is mooted by the interim decree and

was not an injunctive order under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1).

We hold that the school district’s appeal from Keyes

XIV is not moot and that we have jurisdiction to consider

the appeal. A case becomes moot when the controversy

between the parties no longer is “ live” or when the par

ties have no cognizable interest in the appeal’s outcome.

Murphy v. Hunt, 455 U.S. 478, 481 (1982) (per curiam);

Wiley v. NCAA, 612 F.2d 473, 475 (10th Cir. 1979) (en

banc), cert, denied, 446 U.S. 943 (1980). Here, however,

a decision favorable to the school district, reversing the

district court’s ruling that the school system was not uni

tary, or even remanding the question for further consid

eration, would give the district some relief from the court’s

order. The court’s later orders do not supersede Keyes

XIV, but rather emanate from and supplement that opin

A8

ion’s ruling that the school district is not unitary. Cf Bat

tle v. Anderson, 708 F.2d 1523, 1527 (10th Cir. 1983), cert,

dismissed sub. nom. Meachum v. Battle, 465 U.S. 1014

(1984). The appeal from Keyes X IV is not moot.

In addition, we have jurisdiction over the appeal from

Keyes X IV because the denial of the district’s motion for

a declaration of unitariness constitutes an interlocutory or

der “ continuing” an injunction. See 28 U.S.C. § 1292(aXl).

We agree with plaintiffs that denial of the district’s motion

did not “ modify” any prior injunctive order of the court,

but the court’s order plainly resulted in a continuation of

the injunctive decree mandating desegregation of the Den

ver schools. Because we reject plaintiffs’ characterization

of the court’s order as a “ refusal to issue a declaratory

judgment,” we need not address whether the district has

made a sufficient showing to appeal the denial of an in

junctive order. See Stringfellow v. Concerned Neighbors

in Action, 480 U.S. 370, 379 (1987).

We hold, however, that the appeal from Keyes X V is

moot. That order merely required the district to submit

certain plans to the court, and the district fully complied

long ago. Because the district has no legal interest in our

disposition of the appeal from that order, and because no

decision by this court could grant the district any effec

tual relief from the order, Keyes X V is moot and the ap

peal from it dismissed. See International Union, UAW

v. Telex Computer Prods., Inc., 816 F.2d 519, 522 (10th

Cir. 1987); Garcia v. Lawn, 805 F.2d 1400, 1403 (9th Cir.

1986). The other part of the appeal in case number 87-

2634, dealing with Keyes XVITs “ interim decree,” is prop

erly before us, of course, as it modified the court’s earlier

injunction. 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1).

A9

III

The school district’s contentions in No. 85-2814 can be

summarized as follows: (1) because the district’s long-term

compliance with the 1974 decree, as subsequently modi

fied, has remedied any constitutional violation, the court

now must terminate its jurisdiction over student assign

ments; (2) the district court’s findings, which are not chal

lenged on appeal, that the school system is not unitary

regarding faculty assignments and hardship transfer policy,

do not prevent student assignments from being unitary;

(3) because there is no constitutional right to any particu

lar racial balance in a school’s student body, the district

court erred in focusing on the racial identity of three

elementary schools and in demanding future maintenance

of racial balance; (4) concerns about the present or future

segregative effects of board actions (especially implemen

tation of a neighborhood school policy) are irrelevant to

a determination of unitariness because discriminatory im

pact does not violate the Constitution nor does it justify

the court’s continued jurisdiction; and (5) there is no evi

dence that this or future boards will act with segregative

intent. The United States, as amicus curiae, generally agrees

with the district, and argues that a court must terminate

jurisdiction when it finds the district to be unitary, a find

ing it must make when the district has in good faith fully

implemented a court-approved desegregation plan.

A

We begin at the beginning, with the proposition announced

in Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483, 495 (1954)

{Brown I), that a state violates the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment when it intentionally segre

gates or tolerates the segregation of public school students

A10

on the basis of race. Where no statutory dual system ever

existed, such as in Denver, a plaintiff proves a violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment by showing the existence

of segregated schools and the maintenance of that segre

gation by intentional state action. Keyes VII, 413 U.S.

at 198. The school district does not remedy these viola

tions by simply halting its intentionally discriminatory acts

and adopting racially neutral attendance policies. Rather,

as the Supreme Court later held, the affirmative constitu

tional duty to desegregate expressed in Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II), requires school

boards to dismantle their dual school systems. Green v.

County School Bd. o f New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430,

437-38 (1968); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 28 (1971); see also Keyes VII, 413

U.S. at 222-23 (Powell, J., concurring and dissenting). The

Supreme Court has noted that the primary duty to deseg

regate and eliminate racial discrimination in public educa

tion rests with the local school boards. Brown. II, 349 U.S.

at 299. In fact, the school board has an affirmative duty

under the Constitution to remedy past de jure discrimina

tion and eliminate its effects, and “ [ejach instance of a

failure or refusal to fulfill this affirmative duty continues

the violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.” Columbus

Bd. o f Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 459 (1979). It

is irrelevant that the school district does not intend to

perpetuate the prior intentional segregation because “ the

measure of the post-Brown I conduct of a school board

under an unsatisfied duty to liquidate a school system is

the effectiveness, not the purpose, of actions in decreas

ing or increasing the segregation caused by the dual sys

tem.” Dayton Bd. o f Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526, 538 (1979) (Dayton II).

When the school district defaults on its obligation to

stop segregative acts and remedy their effects, a federal

A ll

court in a properly-instituted case must order a remedy,

and in so doing it may employ its full powers as a court

of equity. Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 281 (1977)

(.Milliken II); Swann, 402 U.S. at 15. The court’s remedial

authority, however, is not plenary but extends only to the

breadth of the violation proven. Milliken II, 433 U.S. at

282. A valid desegregation remedy must meet three re

quirements: (1) it must be tailored to the nature and scope

of the constitutional violation; (2) it must be designed to

restore the discrimination victims to the position they would

have occupied had the discrimination not occurred; and

(3) it must take into account the interest of state and local

authorities in themselves managing the public schools. Id.

at 280-81. But, within these parameters, a district court

may order remedial programs even in areas in which in

tentional discrimination has not existed, if it concludes that

the remedy is necessary to “ treat the condition that of

fends the Constitution,” and that “ the constitutional viola

tion caused the condition for which remedial programs are

mandated.” Id. at 282, 286 n.17 & 287 (emphasis added);

Keyes VII, 413 U.S. at 205 (defining de jure segregation

as “ a current condition of segregation resulting from in

tentional state action” ) (emphasis added).

Because desegregation remedial orders are equitable in

nature, we review them only for abuses of discretion.

Wright v. Council o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 470-71 (1972);

Diaz v. San Jose Unified School Disk, 861 F.2d 591, 595

(9th Cir. 1988). Thus, so long as a remedy is tailored to

the violation, it need not be the least restrictive of the

available options. Swann, 402 U.S. at 31 (appellate court

will not overturn remedy if it is “ reasonable, feasible and

workable” ); United States v. Yonkers Bd. o f Education,

837 F.2d 1181, 1236 (2d Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 108 S.

Ct. 2821 (1988); see also United States v. Paradise, 480

U.S. 149, 184 (1987) (plurality opinion). Of course, the

A12

court may modify even a final decree if changing circum

stances indicate the need for a modification. Pasadena City

Bd. o f Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 437 (1976);

Dowell ex rel. Dowell v. Board o f Education o f Oklahoma

City Pub. Schools, 795 F.2d 1516, 1520-21 (10th Cir.)

(Dowell I), cert, denied, 479 U.S. 938 (1986).

Once a school district has eliminated all intentional racial

discrimination, and eradicated all effects of such discrimi

nation, the court may declare it unitary. Green, 391 U.S.

at 439-40; Brown II, 349 U.S. at 301. Although the Su

preme Court has not defined precisely what facts or factors

make a district unitary, a starting point is to evaluate the

factors that make a system segregated. In the context

of a unitariness decision, these factors include elimination

of invidious discrimination in transportation of students,

integration of faculty and staff, equality of financial sup

port given to extracurricular activities at different schools

and integration of those activities, nondiscriminatory con

struction and location of new schools, and assignment of

students so that no school is considered a white or black

school. E.g., Swann, 402 U.S. at 18-19; United States v.

Montgomery County Bd. o f Education, 395 U.S. 225, 231-

32 (1969). This court has defined “ unitary” as the elimina

tion of invidious discrimination and the performance of

every reasonable effort to eliminate the various effects

of past discrimination. Dowell ex rel. Dowell v. Board o f

Education, Oklahoma City Pub. Schools, No. 88-1067, slip

op. at 19 & n.15 (10th Cir. Oct. 7, 1989) (Dowell II); Brown

v. Board o f Education, No. 87-1668, slip op. at 16 (10th

Cir. Dec. 11, 1989). In so defining “unitariness,” we recog

nize that racial balance in the schools is no more the goal

to be attained than is racial imbalance the evil to be rem

edied. See Spangler, 427 U.S. at 434; Swann, 402 U.S.

at 24. Therefore, a court is without power to order con-

A13

stant adjustments in the assignment of students, merely

to maintain a certain racial balance. Spangler, 427 U.S.

at 436-37. But, we also recognize that when a school board

has a duty to liquidate a dual system, its conduct is mea

sured by “ the effectiveness, not the purpose, of [its] ac

tions in decreasing or increasing segregation caused by

the dual system.” Dayton II, 443 U.S. at 538. The exis

tence of racially identifiable schools is strong evidence that

the effects of de jure segregation have not been eliminated.

Swann, 402 U.S. at 26.

Long-term compliance with a desegregation plan that

is complete by its own design and does not contemplate

later judicial reappraisal entitles the school district to a

declaration of unitariness. Spangler, 427 U.S. at 435-37;

see Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. o f Education, 611 F.2d

1239, 1243, 1244 (9th Cir. 1979) (Kennedy, J., concurring)

(because desegregation plan wTas “ a full and complete rem

edy,” compliance with plan for nine years, in light of na

ture and degree of violation, sufficient to make district

unitary). Whether the plan was in fact a complete remedy

for the violation requires both an examination of the orig

inal violation, and, as the district court noted here, an

examination of the actual effects of the plan. Keyes XIV,

609 F. Supp. at 1506; cf. Dayton II, 443 U.S. at 538. Thus,

compliance with even a court-approved desegregation plan,

by itself and without proof of the executed plan’s inten

tion and effect, does not make a district unitary. Pitts

v. Freeman, 755 F.2d 1423, 1426 (11th Cir. 1985); United

States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 647 F.2d 504, 508 (5th Cir.

Unit A 1981). Of course, while a district is not unitary,

the court must maintain supervisory jurisdiction and may

require prior approval of various board actions. Swann,

402 U.S. at 30; Brown II, 349 U.S. at 301 (during transi

tion to unitary system, court will retain jurisdiction). Dur

A14

ing this “pre-unitariness” period the board bears a “ ‘heavy

burden’ of showing that actions that increased or continued

the effects of the dual system serve important and legiti

mate ends.” Dayton II, 443 U.S. at 538 (citation omitted).

B

The district court’s finding that the school district had

not achieved unitary status is a factual one which we re

view under a clearly erroneous standard. Brown, slip op.

at 15; see also id., dissenting slip op. at 3, 52 (Baldock,

J., dissenting). Applying the principles discussed above

and this standard, we cannot conclude that the district

court was clearly erroneous in holding that the school dis

trict’s pupil assignment policies were nonunitary.

As an initial matter, we agree with the school district that

it may be declared unitary in certain aspects, even though

other aspects remain “ nonunitary.” See, e.g., Spangler,

427 U.S. at 436-37; id. at 442 (Marshall, J., dissenting);

Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313, 318 (1st Cir. 1987). Just

as a remedy must be tailored to fit the scope of the viola

tion, Milliken II, 433 U.S. at 280-81, 282; Dayton I, 433

U.S. at 420, so must the court relinquish supervisory con

trol over a school district’s attendance policies and deci

sions when the need for that close supervision no longer

exists. See Jackson County, 794 F.2d at 1543 (“ continuing

involvement,” though not necessarily permanent injunction,

must terminate when no more constitutional violations ex

ist to justify continuing supervision). But even so, the

district makes virtually no argument here that the district

court was clearly erroneous in rejecting the district’s evi

dence and concluding that the district had failed to prove

that existing resegregation resulted from demographic

changes and not from actions of the board. See Keyes

A15

XIV, 609 F. Supp. at 1507-08. Our independent review of

the record reveals nothing that would compel us to over

turn the court’s refusal to find convincing the district’s

evidence. Before the declaration of unitariness it is the

district’s burden to prove resegregation has resulted from

demographic changes and not from actions of the board.

See Dayton II, 443 U.S. at 538.

Instead of arguing that the district court was wrong on

the facts, the district argues that the court was wrong

on the law. In one respect, we agree. As noted above,

a district may be declared unitary in some respects and

not others. The district court appears to have held to the

contrary, see Keyes XIV, 609 F. Supp. at 1508, 1517, and

if that was its intention, it erred. But the error is harm