Hamm v. City of Rock Hill Brief of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hamm v. City of Rock Hill Brief of Petitioners, 1964. 2f72d346-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ad58d911-7c5d-404f-b695-dcff5880144f/hamm-v-city-of-rock-hill-brief-of-petitioners. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

}*%.. * ■

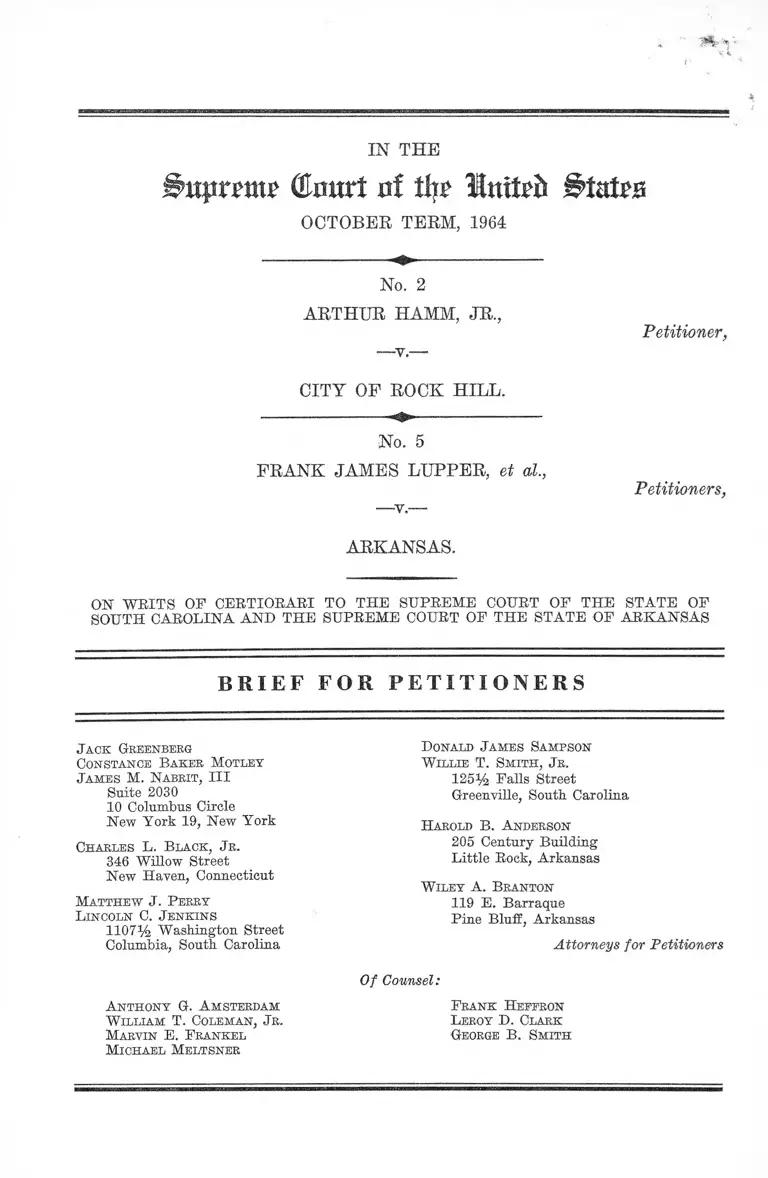

IN THE

n p n m ? (E u u r t a t % I n t t e f c S t a t e s

OCTOBEB TERM, 1964

No. 2

ARTHUR HAMM, JR.,

CITY OF ROCK HILL.

Petitioner,

No. 5

FRANK JAMES LUPPER, et al.,

ARKANSAS.

Petitioners,

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF

SOUTH CAROLINA AND THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF ARKANSAS

B R I E F F O R P E T I T I O N E R S

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

J ames M. Nabrit, I I I

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Charles L. B lack, J r.

346 Willow Street

New Haven, Connecticut

Matthew J . P erry

L incoln C. J enkins

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Donald J ames Sampson

W illie T. Smith, J r.

125% Falls Street

Greenville, South Carolina

H arold B. A nderson

205 Century Building

Little Rock, Arkansas

Wiley A. Branton

119 E. Barraque

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

Of Counsel:

Anthony G. A msterdam F rank H eeeron

W illiam T. Coleman, J r. L eroy D. Clark

Marvin E. F rankel George B. Smith

Michael Meltsner

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ..... ....................... ........... __...._............. . 1

Jurisdiction ....... ...................... ................ ............. .....____ 2

Questions Presented......... ........................... 3

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes and Ordinance

Involved ............................................... 3

Statement ........................................... 7

1. Hamm v. City of Rock Hill .......... ....... ....... 7

2. Lupper et al. v. Arkansas ................................ 11

Summary of Argument ........... ...................................... 14

A rgum ent :

1. The Enactment of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, Subsequent to These Convictions But

While They Were Still Under Direct Review,

Makes Necessary Either Their Outright Re

versal or a Remand to the State Courts for

Consideration of That Act ............................ 18

A. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Abates

These Prosecutions as a Matter of Fed

eral Law, and These Cases Should Be

Reversed on That Ground ................. . 18

B. The Least Possible Consequence in These

Cases, of the Rule Announced in Bell v.

Maryland Is Their Remand to the State

Courts, for Consideration There of the

Effect of the Enactment of the Federal

Civil Rights Act of 1964 ............................. 41

11

II. Petitioners’ Convictions Enforced Racial Dis

crimination in Violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States ........... ..... ............................................ 46

A. The States of Arkansas and South Caro

lina Are Involved in the Acts of Racial

Discrimination Sanctioned in These Cases

Because Such Acts Were Performed in

Obedience to Widespread Custom, Which

in Turn Has Received Massive and Long-

Continued Support From State Law and

Policy................. ................ ........... ........... 46

B. The Employment of the State Judicial

Power, Together With State Police and

Prosecutors, to Enforce the Racial Dis

crimination Here Shown, Constituted

Such Application of State Power as to

Bring to Bear the Guarantees of the

Fourteenth Amendment............................ 51

C. The Obligation of These States Under

the Fourteenth Amendment Is an Affirma

tive One—the Affording of “Equal Pro

tection of the Laws.” That Obligation Is

Breached When, as Here, the State Main

tains a Regime of Law Which Denies to

Petitioners Protection Against Public Ra

cial Discrimination, and Instead, Subordi

nates Their Claim of Equality in the Com

mon and Public Life of the States to a

Narrow Property Claim, Enforcing the

Subordination by the Extreme Sanction

of the Criminal Law ................................ 57

PAGE

Ill

D. None of the Theories of “State Action”

Urged by Petitioners Needs to Result in

the Extension of Fourteenth Amendment

Guarantees to the Genuinely Private Con

cern of Individuals, for a Reasonable In

terpretation of the Substantive Guaran

tees of the Amendment Can and, Ought to

Prevent That Result ................................ 65

III. These Convictions Violate Due Process in

That There Was Inadequate Conformity Be

tween Definite Statutes and the Conduct

Proved.......... .............. 70

A. These Convictions in Both Cases Violated

Due Process of Law, in That They Were

Had Under Statutes Which, in the Pro

cedural and Evidentiary Context, Fail

to Designate as Criminal the Conduct

Proven, With the Clarity Required Under

Decisions of This Court ......................... 70

B. In the Hamm case, the Defendant Was

Denied Due Process of Law by the Re

fusal of the Prosecutor and Trial Judge to

Specify the Law Under Which He Was

Charged, by the Consequent Vagueness of

the Law Set Forth in the Instructions to

the Jury, and by the Variance Between

the Law Charged the Jury and the Law

on the Basis of Which the State Appel

late Courts Sustained Defendant’s Con

viction .................................... .............. 79

PAGE

A p p e n d ix ............................................................................ ................. l a

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II ..................... . la

IV

T able of Cases

page

Barr v. Columbia,-----U. S .----- , 12 L. Ed. 2d 766 38

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ............................. . 54

Bell v. Maryland,----- U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d 822 .... 14,

15, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28,

36, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44,

46, 48, 52, 54, 55, 56, 58,

59, 61, 64, 66, 68, 69

Bouie v. Columbia,----- U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d 894 .... 45,

70, 71, 72, 76,

77, 78, 80, 82

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ________ _____ 59

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .............. 59

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ........................................................................ ....... 64

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 .......... ............ . 83

Catlette v. United States, 132 F. 2d 902 (4th Cir. 1943) 64

Charleston v. Mitchell, 239 S. C. 376, 123 S. E. 2d 512

(1961) ______________ ___________ ___________ 82

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 .............................57, 64, 67

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S, 196 .......... ..... ..... ..... ......... 83

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 .................. 83

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 ................................ 60

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 ........... ...... .......77, 78, 83

Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U. S. (9 Wheaton) 1 .................. 24

Greenville v. Peterson, 239 S. C. 298, 122 S. E. 2d 826

(1961), rev’d, 373 U. S. 244 ....................................49,82

Hauenstein v, Lynham, 100 U. S. 483 .............. .......35, 42, 45

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ............... ..... .......... 83

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24 .............. ......................... 53

PAGE

In re Eahrer, 140 U. S. 545 ....... ......................... ....... . 49

Kentucky v. Dennison, 65 U. S. (24 How.) 66 .............. 65

LeRoy Fibre Co. v. Chicago M. & St. P. Ry., 232 U. S.

340 ......... ..... .............................— .................. ........... 69

Louisville & Nashville R.R. v. Mottley, 211 IT. S. 149 .... 39

Lynch v. United States, 189 F. 2d 476 (5th Cir. 1951),

cert. den. 342 U. S. 831 ......... ........... ............... ..... .... 64

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S

151 .......................................

McGhee v. Sipes, 334 U. S. 1............ ...........................

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501 ........... ............... ....

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 14 U. S. (1 Wheat.) 304 ...

Moore v. United States, 85 Fed. 465 (8th Cir. 1898)

NLRB v. Carlisle Lumber, 94 F. 2d 138 (9th Cir. 1937),

cert. den. 304 U. S. 575 (1938), cert. den. 306 U. S.

646 (1939) ...................... ........... ..... ............................. 39

NLRB v. Fainblatt, 306 U. S. 601 ................................ 21

Phelps Dodge v. NLRB, 113 F. 2d 202 (2d Cir. 1940),

modified and remanded on other grounds, 313 U. S.

177 (1941) .................................................................. 39

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 ..........................49, 82

Robinson v. Florida,-----U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d 771 ..50, 51

Russell v. United States, 369 U. S. 749 ..................... 84

San Diego Building Trades Council, Millmen’s Union,

Local 2020, Building Material and Dump Drivers,

Local 36 v. Garmon, 359 U. S. 236 ............................ 25

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................. 16, 51, 52, 53, 54,

55, 56, 57, 65

64

54

59

59

28

V I

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 376 U. S. 940 .......... . 83

Slaughter House Cases, 83 U. S. (16 Wall.) 36 ......... 60

Sola Elec. Co. v. Jefferson Elec. Co., 317 U. S. 173 .... 24

Spartanburg v. Winters, 233 S. C. 526, 105 S. E. 2d

703 (1958) .................................................... ............. 84

Sperry v. Florida, 373 U. S. 379 ................. ....... ........ . 24

State v. Cole, 2 McCord 1 (S. C. 1822) .....................37, 38

State v. Moore, 128 S. C. 192, 122 S. E. 672 (1924) ....43,44

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IJ. S. 303 ................. 61

Stromberg v. California, 283 IT. S. 359 ...... .............. 78, 82

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154.......... ...................... 83

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 .............. ................. 83

Terry v. Adams, 345 IT. S. 461 ..................... 52, 59, 63, 64, 67

Testa v. Katt, 330 U. S. 386 .................. ........................ 45

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 IJ. S. 88 ....... ..... ...... .....78, 83

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 .......70, 77, 78, 82, 83

United States v. California, 297 U. S. 175 ____ 40

United States v. Chambers, 291 U. S. 217.................... 25

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542 .................... 64

United States v. Darby, 312 U. S. 100 ....................... 21

United States v. Taylor, 123 F. Supp. 920 (S. D. N. Y.

1954) ................. .................................................... ..... 28

United States v. Tynen, 78 U. S. (11 Wall.) 88 .......... 25

Van Beeck v. Sabine Towing Co., 300 U. S. 342 .......... 25

Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U. S. I l l ................................ 21

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 287 ............. . 82

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ................ ............ 78

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 ........................ .......45, 83

PAGE

Vll

F ederal S tatutes

page

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241 ...A,14,18,19, 20, 21,

22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28,

30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35,

36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41,

42, 44, 45, 50, 69

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat, 27, 42 IT. S. C. §1982

(1952) .................. ...................... ...............................53,56

National Labor Relations Act, §8(a)(1), 8(a)(3), 49

Stat. 452 (1935), 29 U. S. C. §158 a(l), a(3) (1952) .. 40

1 U. S. C. §§1, 101-104, 108 ........... .............................. 29

1 IT. S. C. §109 ........................................ ....4,14,26,29,33,

35, 36, 38, 41

S tate S tatutes

Ark. Stat. §1-103 (1947) ................. .......... ................. 6,42

Ark. Stat. §1-104 (1947) ............... ...........................6,7,43

Ark. Stat. §41-1432 (Act 226 of 1959) .....................12,13

Ark. Stat. §41-1433 (Act 14 of 1959) .............. 6,13, 71, 73,

75, 76, 77, 78

Ark. Stat. Ann. §73-1218 (1957) ...................... 47

Ark. Stat. Ann. §73-1614 (1957) .............. 47

Ark. Stat. Ann. §73-1747 (1957) ........................... 47

Ark. Stat. Ann. §76-1119 (1957) ........................... 47

Ark. Stat. Ann. §80-509 (1960) .................. 47

Ark. Stat. §80-544 (Acts of 1958, 2d Ex. Sess.) . 47

Ark. Stat. §80-2401 (1960) ...................................... 47

Ark. Stat. §84-2724 (1960) ..................... 47

PAGE

Ark. Stat. Ann. §§144, 145 (1947)

Ark. Stat. Ann. §80-2401 (1960)

City of Rock Hill Code of Laws, §19-12 .....5, 9, 79, 80,

1 Maryland Code §3 (1957) ................................ ......

S. C. Acts and Joint Resolutions 1956, No. 914 ......

S. C. Code §5-19 (1962) ................. ............. ...............

S. C. Code §16-386 (1952 as amended 1954) 4,9,80,

S. C. Code §16-388 (1952 as amended 1960) ......5,9,10,

73, 75, 76, 77,

80, 81, 82, 83,

S. C. Code §21-751 (1962) ............... ..... .....................

S. C. Code §22-3 (1962) _______________________

S. C. Code §40-452 (1962) ................. .......-.................

S. C. Code §51-2.1 (1962) ................................. ...........

S. C. Code §§55-1, 55-2 (1962) ........................ ..........

S. C. Code §58-551 (1962) ........ ..................................

S. C. Code §§58-714, 58-719, 58-720 (1962) ..................

S. C. Code §§58-1331, 58-1340 (1962) ..........................

Ya. Code §18.1-173 (1960) .............. ..................... .......

Ot h er A u tho rities

Brief for Respondents, Shelley v. Ivraemer, 334 U. S. 1

Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, Bell

v. Maryland,-----U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d 822 ......

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. 2464 (1870) ..........

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 3rd Sess. 775 (1871) ............

viii

47

47

,82

42

47

47

,82

72,

78,

84

48

48

48

48

47

47

47

47

75

54

58

29

29

IX

110 Cong. Rec. 1456-7 (daily ed. Jan. 31, 1964) ........... 21

110 Cong. Rec. 9162-3 (daily ed. May 1, 1964) _____22, 23

110 Cong. Rec. 12999 (daily ed. June 11, 1964) _____ 32

Faubus, Inaugural Address, 4 Race Rel. L. Rep. 179

(1959) ...................................... ..... .............................. 47

Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House

Committee on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

ser. 4, pt. 1 (1963) .................................................. . 20

Henkin, Shelley v. Kraemer: Notes for a Revised Opin

ion, 110 U. Pa. L. Rev. 473 (1962) .......... ..............66, 67

House Judiciary Committee Report on the Civil Rights

Act, H. R. Report No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1963) .................... .............................................20,30,31

Million, Expiration or Repeal of a Federal or Oregon

Statute as a Bar to Prosecution for Violations

Thereunder, 24 Ore. L. Rev. 25 (1944) .............. ...... 29

New English Dictionary ...... ............. ..... .......... .......... 30

Note, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) ................... ......... 83

Record in McGee v. Sipes, 334 U. S. 1 ...................... . 54

Webster’s New International Dictionary, 2d ed......... 30

PAGE

I n t h e

(£mtt nl H i t I n t t ^ S t a t e s

O ctober T erm , 1964

No. 2

A r t h u r H am m , J r .,

—v.—

C ity of R ock H il l .

Petitioner,

No. 5

F rank J ames L u ppe r , et al.,

—v.

Petitioners,

A rkansas.

o n w r i t s o f c e r t i o r a r i t o t h e s u p r e m e c o u r t o f t h e s t a t e o f

SOUTH CAROLINA AND TH E SUPREM E COURT OF TH E STATE OF ARKANSAS

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

O pinions Below

1. Hamm v. Rock Hill. The opinion of the Supreme Court

of South Carolina (R. Hamm 101) is reported at 241 S. C.

446, 128 S. E. 2d 907 (December 6, 1962). The order of the

Sixth Judicial Circuit Court of York County, December

29, 1961, is unreported (R. Hamm 96). The oral sentenc-

2

ing of the defendant in the Rock Hill Recorder’s Court,

June 29, 1960, is unreported (R. Hamm 96).

2. Lupper v. Arkansas. The opinion of the Supreme

Court of Arkansas (R. Lupper 76) is reported a t ----— Ark.

, 367 S. W. 2d 750 (May 13, 1963). The supplemental

opinion denying rehearing of the Supreme Court of Ar

kansas (R. Lupper 89) is reported at ----- A rk .------ , 367

S. W. 2d 760 (June 3, 1963). The Pulaski County Circuit

Court delivered no opinion (R. Lupper 75). The jury fixed

the sentences (R. Lupper 74).

Jurisdiction

1. Hamm v. Rock Hill. The final judgment of the Su

preme Court of South Carolina, which is the order denying

rehearing, was entered on January 11, 1963 (R. Hamm

106). The petition for certiorari was filed April 10, 1963,

and granted June 22, 1964 (R, Hamm 108).

2. Lupper v. Arkansas. The final judgment of the Su

preme Court of Arkansas, which is the order denying re

hearing, was entered June 3, 1963 (R. Lupper 89). The

petition for certiorari was filed September 3, 1963, and

granted June 22, 1964 (R. Lupper 91).

The jurisdiction of this Court in each of these cases is

invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. Code §1257(3), petitioners

having asserted below and here the denial of rights, privi

leges and immunities secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Does the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 compel the

reversal of these convictions, as a matter of federal law!

2. Must these cases be remanded to the state courts, for

consideration there of the effect of the Federal Civil Rights

Act?

3. Do these convictions result in the enforcement of

racial discrimination against petitioners, with such ad

mixture of state action” as to bring to bear the guarantees

of the Fourteenth Amendment?

4. Can these convictions stand against due process vague

ness objections, in view of the fact that the conduct shown

in the record does not fall within the language of the stat

utes applied?

5. Did the refusal of the trial judge to require the prose

cutor in the Hamm case to specify the law under which the

defendant was charged, the consequent indefinite form of

the jury instructions, and the varying statutory grounds on

which Hamm’s conviction was affirmed by the state appel

late courts, deprive petitioner of due process of law?

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes and

Ordinance Involved

1. This case involves the following provisions of the

Constitution of the United States:

Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3;

Article VI, paragraph 2;

The Fourteenth Amendment.

4

2. This case also involves the following statutes of the

United States:

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II, 78 Stat. 243-246, set

forth, infra, at p. l a ;

1 U. S. C. §109, 61 Stat. 635:

Repeal of statutes as affecting existing liabilities.—

The repeal of any statute shall not have the effect to

release or extinguish any penalty, forfeiture, or lia

bility incurred under such statute, unless the repeal

ing Act shall so expressly provide, and such statute

shall be treated as still remaining in force for the

purpose of sustaining any proper action or prosecution

for the enforcement of such penalty, forfeiture, or

liability. The expiration of a temporary statute shall

not have the effect to release or extinguish any pen

alty, forfeiture, or liability incurred under such stat

ute, unless the temporary statute shall so expressly

provide, and such statute shall be treated as still re

maining in force for the purpose of sustaining any

proper action or prosecution for the enforcement of

such penalty, forfeiture, or liability.

3. This case also involves the following South Carolina

Statutes and Ordinance of the City of Rock Hill:

Section 16-386, Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952,

as amended 1954:

Entry on another’s pasture or other lands after no

tice; posting notice

Every entry upon the lands of another where any

horse, mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pas

tured, or any other lands of another, after notice from

the owner of tenant prohibiting such entry, shall be a

misdemeanor and be punished by a fine not to exceed

5

one hundred dollars, or by imprisonment with hard

labor on the public works of the county for not ex

ceeding thirty days. When any owner or tenant of any

lands shall post a notice in four conspicuous places on

the borders of such land prohibiting entry thereon, a

proof of the posting shall be deemed and taken as no

tice conclusive against the person making entry, as

aforesaid, for the purpose of trespassing.

Section 16-388, Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952,

as amended 1960:

Any person:

(1) Who without legal cause or good excuse enters into

the dwelling house, place of business or on the

premises of another person, after having been

warned, within six months preceding, not to do so

or

(2) Who, having entered into the dwelling house, place

of business or on the premises of another person

without having been warned within six months

not to do so, and fails and refuses, without good

cause or excuse, to leave immediately upon being

ordered or requested to do so by the person in

possession, or his agent or representative, shall

on conviction, be fined not more than one hundred

dollars, or be imprisoned for not more than thirty

days.

Section 19-12, Code of Laws of the City of Rock Hill:

Entry on lands of another after notice prohibiting

the same

Every entry upon the lands of another, after notice

from the owner or tenant prohibiting the same, shall

be a misdemeanor. Whenever any owner or tenant of

any lands shall post a notice in four conspicuous places

6

on the border of any land prohibiting entry thereon,

and shall publish once a week for four consecutive

weeks such notice in any newspaper circulating in the

county where such lands situate, a proof of the posting

and publishing of such notice within twelve months

prior to the entry shall be deemed and taken as notice

conclusive against the person making entry as afore

said for hunting and fishing.

4. This case also involves the following Arkansas Stat

utes :

Arkansas Statutes §41-1433 (Act 14 of 1959):

Any person who after having entered the business

premises of any other person, firm or corporation,

other than a common carrier, and who shall refuse to

depart therefrom upon request of the owner or man

ager of such business establishment, shall be deemed

guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction shall be

fined not less than fifty dollars ($50.00) nor more than

five hundred dollars ($500.00), or by imprisonment not

to exceed thirty (30) days, or both such fine and im

prisonment.

Arkansas Statutes, §1-103 (1947) :

Repeal of criminal or penal statute—Effect on Of

fenses Committed.-—When any criminal or penal stat

ute shall be repealed, all offenses committed or for

feitures accrued under it while it was in force shall be

punished or enforced as if it were in force, and not

withstanding such repeal, unless otherwise expressly

provided in the repealing statute. [Act Dec. 21, 1846,

§1, p. 93; C. & M. Dig., §9758; Pope’s Dig., 13283.]

Arkansas Statutes, §1-104 (1947):

Existing actions not affected hy repeal.—No action,

plea, prosecution or proceeding, civil or criminal, pend-

7

ing at the time any statutory provision shall be re

pealed, shall be affected by such repeal, but the same

shall proceed in all respects as if such statutory provi

sion had not been repealed, (except that all proceed

ings had after the taking effect of the revised statutes,

shall be conducted according to the provisions of such

statutes, and shall be in all respects, subject to the

provisions thereof, so far as they are applicable).

[Rev. Stat., ch. 129, §31; C. & M. Dig., §9759; Pope’s

Dig., §13284.]

Statement

1. H amm v. City of Rock Hill

Petitioner Hamm, a Negro college student, and Reverend

C. A. Ivory, a Negro minister, were arrested for a sit-in

demonstration at the lunch counter of McCrory’s variety

store in Rock Hill, South Carolina on June 7, 1960. They

were convicted of “trespass” and sentenced to pay a fine

of $100 or spend 30 days in jail (R. Hamm 1, 2). Rev.

Ivory died during the appeal of the convictions (R. Hamm

98).

On June 7, 1960 Hamm and Rev. Ivory entered

McCrory’s Dime Store (R. Hamm 67, 68), a retail national

chain store, open to the public at large (R. Hamm 59, 60,

61, 66, 68). After purchasing several items in the store,

they decided to order coffee at the lunch counter (R. Hamm

69, 70, 76). The lunch counter is one of 20 counters in the

store and is separated from the adjoining counter solely

by an aisle (R. Hamm 58). Hamm seated himself on

a stool, and Rev. Ivory, a cripple, remained in his wheel

chair next to the counter (R. Hamm 12, 13, 28). Although

Hamm and Rev. Ivory were orderly and neatly dressed

(R. Hamm 20, 64, 65, 71, 72) the manager of the store,

8

H. C. Whiteaker, told them that “he could not serve them”

(R. Hamm 63). Mr. Whiteaker, under questioning by de

fendant’s counsel, clearly specified that the store’s policy

was that of not serving Negroes seated at the lunch counter

(R. 59-64):

Q. Now, I believe, is it true that you invite members

of the public to come into your store? A. Yes, it is

for the public.

* # >X< # #

Q. The policy of your store as manager is not to

exclude anybody from coming in and buying these

three thousand items on account of race, nationality

or religion, is that right? A. The only place where

there has been exception, where there is an exception,

is at our lunch counter.

# # * #

Q. I see. Now, sir, if I may ask you, what is the

basis of this policy as to the lunch counter; first, I

want to know as to race, religion and nationality. What

is the basis of it ? A. Since I have been here, which is,

the restaurant has been open nine years, we have not

served a Negro seated at the lunch counter (R. Hamm

59).

Negroes were welcome in all other parts of the store and

could buy food to “take out” at the end of the counter

(R. Hamm 60, 61). This policy of segregation at lunch

counters in places of public accommodation was in conform

ity with the custom of the community (R. Hamm 23, 61).

Q. Oh, I see, but generally speaking, you consider

the American Negro as part of the general public, is

that right, just generally speaking? A. Yes, sir.

Q. You don’t have any objections for him spending

any amount of money he wants to on these 3,000 items

9

do you? A. That’s up to him to spend if he wants to

spend.

Q. This is a custom, as I understand it, this is a

custom instead of a law that causes you not to want

him to ask for service at the lunch counter? A. There

is no law to my knowledge, it is merely a custom in

this community (E. Hamm 61).

After the arrival of two police officers, the manager asked

Hamm and Eev. Ivory to leave the lunch counter (R. Hamm

64). It is not clear whether the manager made the request

with or without the prompting of the police officers (R.

Hamm 71, 77). Rev. Ivory insisted upon a refund for the

purchases that he had made in other parts of the store.

The testimony is conflicting as to whether Rev. Ivory re

fused to leave or whether he merely insisted upon a refund

before leaving and was arrested before the manager indi

cated the place for refund (R. Hamm 14, 15, 22, 29, 30, 31,

32, 71, 79).

Rev. Ivory was tried for trespass in the Recorders Court

in the City of Rock Hill on June 29, 1960. The prosecuting

attorney relied on three state and city “trespass” stat

utes, S.C. Code §16-386, S.C. Code §16-388 (2), Code City

of Rock Hill §19-12, and “any other sections” (R. Hamm 7).

Petitioner Hamm’s case was submitted to the jury on the

Ivory record (R. Hamm 1). Defendants filed timely mo

tions raising Fourteenth Amendment due process and equal

protection objections during and after the trial (R. Hamm

34-53, 80-81). The jury returned a general verdict of guilty

and defendants were sentenced to pay a fine of $100 or

serve 30 days in prison. On December 29, 1961 the con

victions were affirmed along with several breach of the

peace convictions and other trespass convictions in the

Sixth Judicial Circuit Court of York County. The Court

1 0

did not specify which, statute applied to the Hamm case,

but did not distinguish the trespass charge in Hamm’s

case from a trespass charge in a case arising before enact

ment of the 1960 trespass law S.C. Code §16-388 (2).

On December 6,1962, the Supreme Court of South Carolina

affirmed the conviction of Hamm (R. Hamm 101) on the

basis of S.C. Code §16-388 (2) (1960 trespass law). That

Court concluded:

There is nothing substantial in the objection that the

City Recorder refused to require the City of Rock Hill

to elect the particular statute upon which the prosecu

tion was based. The warrant charged a single offense

of trespass and the Recorder submitted to the jury

only the question of whether the appellant was guilty

of trespass as such was defined in the statute here

tofore cited. There was no prejudice to the appellant.

The record shows that the appellant and the Rev.

C. A. Ivory are Negroes. It was the policy of McCrory’s

store not to serve Negroes at its lunch counter. The

appellant asserts by exceptions 3, 4 and 5 that his

arrest by the police officers of the City of Rock Hill

and his conviction of trespass that followed was in

furtherance of an unlawful policy of racial discrimina

tion and constituted State action in violation of his

rights to due process and equal protection of the laws

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution. Identical contention was made, con

sidered and rejected in the cases of City of Greenville

v. Peterson, et al., 239 S.C. 298, 122 S. E. 2d 826; City

of Charleston v. Mitchell, et al., 239 S.C. 376, 123 S. E.

(2d) 512; City of Columbia v. Barr et al., 239 S.C. 395,

123 S. E. (2d) 521, and City of Columbia v. Bouie,

et al., 239 S.C. 570, 124 S. E. 2d 332, in each of which

1 1

was involved a sit-down demonstration similar to that

disclosed by the nncontradicted evidence here, at a

lunch counter in a place of business privately owned

and operated, as was MeCrory’s in the case at bar

(R. Hamm 105).

Rehearing was denied on January 11, 1963 (R. Hamm 106).

2. L upper et al. v. Arkansas

Petitioners Frank James Luppera and Thomas Robinson

were arrested and convicted of trespass for participation

in a “sit-in” demonstration in the luncheon area of the Blass

Department Store in Little Rock, Arkansas.

On the afternoon of April 13, 1960, police officer Baer

followed a group of Negroes, including petitioner Thomas

Robinson, when he saw them entering the Blass Depart

ment Store (R. Lupper 36, 38). When he observed their

seating themselves in the mezzanine luncheon area he left

the store and reported his observations to police head

quarters (R. Lupper 37). Two other police officers were

sent by headquarters to join officer Baer (R. Lupper 37).

When the three officers were across the street from the

store they were approached by two store managers, whom

they accompanied back to the store upon being told that

“they had some colored boys” (R. Lupper 26, 27). The

petitioners were found on the main floor of the department

store (R. Lupper 32, 33). The managers pointed them out

to the police as two of a group of five or more Negroes

who had sought service in the luncheon area and failed to

a The opinion of the Supreme Court of Arkansas uses the name

“James Frank Lupper.” The brief herein uses the name Frank

James Lupper as that is petitioner’s true name (R. Liipper 53).

1 2

leave after being refused service (R. Lupper 32, 33, 42, 46).b

The officers testified they arrested petitioners after peti

tioners admitted they had refused to leave the luncheon

area upon the manager’s request (R. Lupper 29). None of

the officers had seen the petitioners refuse to leave the

luncheon area, and as one stated, the arrests had been made

solely because the managers had asked to “get them out

from the lunch counter” (R. Lupper 29, 35, 38).

The store was open to the general public0 and the

luncheon area was operating at the hour petitioners were

seeking service (R. Lupper 47). One manager noted that

it was his “busiest time” and he “expected a good many

people” (R. Lupper 47). Negroes who sought service in the

luncheon area, however, were told by the manager, “we are

not prepared to serve you at this time and will you kindly

excuse yourself” (R. Lupper 42). No objection was made

to the demeanor of appellants as the managers testified

that they were not loud, boisterous or disrespectful at any

time and were “neatly dressed” (R. Lupper 42, 48).a

The petitioners, two Negro students at a local college,

were regularly served in areas of the department store

other than the luncheon area, petitioner Lupper testifying

that his mother held a charge account with the store for

some 19 to 20 years (R. Lupper 54, 59, 61, 62). Petitioners

indicated that as they were regular customers in the store

they thought they should be served in the luncheon area

also (R. Lupper 54, 57, 62, 64).

b Petitioner Robinson claimed he had not been told to leave, for

after arriving in the mezzanine he had turned and left when he

saw the other Negro youths leaving (R. Lupper 61, 64-65).

0 In addition to trespass, petitioners were charged under the

breach of the peace statute which covers only a “public place of

business.” Section 41-1432, Arkansas Statutes (Section 1 of Act 226

of 1959).

a This fact dictated reversal of petitioners’ convictions of breach

of the peace by the Supreme Court of Arkansas (R. Lupper 79, 81).

13

Petitioners were charged with breach of the peace in vio

lation of Section 41-1432, Arkansas Statutes (Section 1

of Act 226 of 1959) and with refusal to leave a business

establishment after request in violation of Section 41-1433,

Arkansas Statutes (Section 1 of Act 14 of 1959).

They were tried on April 21, 1960 in the Municipal Court

of Little Rock and convicted on both charges (R. Lupper

1, 2). Thereupon they appealed to the Pulaski County

Circuit Court, where trial was had before a jury on June

17, 1960. Each was again convicted on both charges and

each received a fine of $500.00 and 6 months’ imprisonment

on the Act 226 violation and a fine of $500.00 and 30 days’

imprisonment on the Act 14 violation (R. Lupper 74).

Thereafter, the petitioners took an appeal to the Supreme

Court of Arkansas. This appeal was consolidated for brief

ing with Briggs v. State (No. 4992) and Smith v. State (No.

4994) (R. Lupper 77). On May 13,1963, the Supreme Court

of Arkansas handed down its decision, reversing all the

Act 226 convictions for lack of evidence and affirming the

Act 14 convictions of the petitioners, holding:

It is contended that the Act is so vague as to make

it impossible to determine what conduct might trans

gress the statute. It is said that the Act provides no

ascertainable standard of criminality. With these con

tentions we cannot agree. The Act clearly, specifically

and definitely makes the failure to leave the business

premises of another upon request of the owner or

manager a misdemeanor (R. Lupper 81).

Appellants further assert that the Act has been

unconstitutionally applied in that the enforcement of

such Act amounts to “state action” in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitu

tion. . . .

14

There is no right in these defendants under either

State or Federal law to compel the owners of lunch

counters to serve them. Many states have enacted

so-called “public accommodation” statutes but Arkan

sas is not among them. The Fourteenth Amendment

does not guarantee any such right to the appellants

(R.. Lupper 84).

# # * # #

The petitioners sought rehearing (R. Lupper 88-89)

which was denied (R. Lupper 89-90) on June 3, 1963.

Summary o f Argument

I

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II (Public Accommo

dations), compels the reversal of these eases and their re

mand for dismissal, both under the doctrine expounded in

Bell v. Maryland,----- U. S .------ , 12 L. Ed. 2d 822, and by

virtue of §203 (c) of the Civil Rights Act, forbidding “pun

ishment” of acts such as those here shown to have been

committed. By an action “possibly unique” in national leg

islative history, Bell v. Maryland, supra, at 829, Congress

has declared it to be in the national interest that acts such

as those here sought to be punished be permitted, has out

lawed the interest vindicated by these prosecutions, and has

expressly forbidden the punishment of persons acting as

petitioners have acted. The federal and common-law doc

trine of abatement of criminal prosecution, on removal of

the taint of criminality, here applies, and the federal “sav

ing statute” (1 U. S. C. §109) does not shield these prose

cutions from the effect of that doctrine, for, as a matter

both of its own construction and the effect on it of §203(c)

of the Civil Rights Act, the “saving” statute has no appli

cation here.

15

Though the Court need never reach the point, it is, more

over, entirely clear, under the holding in Bell v. Maryland,

supra, that these cases, if it were not that they must be

reversed as a matter of federal law, must be remanded to

the state courts for consideration there of the abating effect

of the Civil Rights Act, for that Act, besides being para

mount national law, is a part of the law of every state, and

the position, in each state, is therefore the same as the posi

tion in Maryland as shown in Bell.

In the South Carolina case, the absence, in that state, of

any “saving” statute, and the state’s consistent adherence

to the common-law rule of abatement on a legislative aboli

tion of the crime, would make remand unnecessary, even

under the erroneous assumption that state law alone ap

plied, since South Carolina could not refuse to abate these

prosecutions, in the face of the Civil Rights Act, without

effecting a forbidden discrimination against a federal law.

II

These records exhibit the use of state power to effect

racial discrimination, contrary to the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

South Carolina and Arkansas, as a matter of well-known

history, have lent state power to the support of the custom

of segregation. Neither state has taken any turn in regard

to this question; both, for example, still retain on their

statute-books extensive Jim Crow codes. The custom thus

supported and given moral sanction by law is in turn ex

pressed in the actions taken by proprietors in these cases.

The causal chain is clear and visible; it is impossible that

no causal connection exists between the power of the state

that supports the custom of segregation, and the act of the

proprietor who follows the custom. At the least, the state

itself, in a criminal prosecution, cannot be heard to deny

16

that its own efforts to preserve segregation as a custom

have been efficacious.

Further, under the doctrine of Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U. S. 1, “state action” is found in the use of the state police,

prosecutorial, and judicial powers, to implement and give

sanction to racial discrimination in the extended public

life of the community, even though the pattern of discrimi

nation is nominally “private” in origin. No suggested dis

tinction of Shelley is successful, and that case must either

be overruled, openly or sub silentio, or applied here.

Thirdly, the states concerned have acted, insofar as “ac

tion” is necessary to the “denial” of “equal protection,”

by maintaining legal regimes in which, in final effect, a

narrow and technical “property” claim is given preference

to the claim of Negroes to be protected against the insult

and inconvenience of public segregation.

None of these theories of “state action,” broad though

they are, need bring the Fourteenth Amendment into the

authentically private life of man, for there are many rea

sonable canons of interpretation, applicable to the sub

stantive guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment, which

may be invoked if cases arise calling for their invocation.

In the cases at bar, no true private assoeiational interest

exists and the Court need not and ought not, in these cases,

be concerned with the exact location of any lines which

might later have to be drawn. It is enough to note that

sound and equitable considerations exist on the basis of

which such lines may be drawn when needful, so that the

Court need not, in taking note of the plain “state action”

here shown, fear a commitment to the intrusion of the

Fourteenth Amendment into matters genuinely private.

17

III

These convictions violate due process of law, in that the

statutes alleged to be violated do not forbid the conduct

shown on the record, so that the convictions either (1 ) are

without any evidence of the crime charged, or (2) are

under a statute failing entirely to warn.

The statutes concerned in these cases very clearly make

criminal a refusal to leave the “premises” or “place of

business,” after an order to leave the “premises” or “place

of business.” Both records show affirmatively, on the

state’s own testimony, that no such order was given; the

order, in each case, was an order to move away from one

part of the “premises” or “place of business.” Criminal

trespass statutes do not cover the whole field of civil tres

pass; they are special and narrow in their application.

The action of disobeying an order to leave a man’s house

is a very different action from that of disobeying an order

to move away from his piano, in a context of general wel

come elsewhere in the house; the statute criminally penal

izing the first cannot automatically be extended to cover

the second. A statute prescribing a long jail term for re

fusal to leave the “place of business” or being ordered to

leave the “place of business,” cannot, without a violation

of due process, be made the basis of conviction for refus

ing to stand back from the lunch counter.

In the Hamm case, the defendant was denied due process

of law by the refusal of the prosecutor and trial judge to

specify the law under which he was charged, by the con

sequent vagueness of the law set forth in the instructions

to the jury, and by the variance between the law charged

the jury and the law on the basis of which the state appel

late courts sustained defendant’s conviction.

18

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Enactment o f the Civil Rights Act o f 1 9 6 4 , Sub

sequent to These Convictions But W hile They Were

Still Under Direct Review, Makes Necessary Either Their

Outright Reversal or a Remand to the State Courts for

Consideration o f That Act.

A. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Abates These Prosecutions

as a M atter of Federal Law, and These Cases Should Be

Reversed on That Ground.

On July 2, 1964, the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964,

78 Stat. 241, went into effect, providing, inter alia:

T itle II— I n ju n c t iv e R e l ie f A gainst D iscrim in a tio n

in P laces of P ublic A ccommodation.

Sec. 201. (a) All persons shall be entitled to the full

and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities,

privileges, advantages, and accommodations of any

place of public accommodation, as defined in this sec

tion, without discrimination or segregation on the

ground of race, color, religion, or national origin.

(b) Each of the following establishments which

serves the public is a place of public accommodation

within the meaning of this title if its operations affect

commerce, or if discrimination or segregation by it is

supported by State action: . . .

* * *

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch

counter, soda fountain, or other facility principally

engaged in selling food for consumption on the prem

ises, including, hut not limited to, any such facility

19

located on the premises of any retail establishment;

or any gasoline station; . . .

* * *

(4) Any establishment (A) (i) which is physically

located within the premises of any establishment

otherwise covered by this subsection, or (ii) within

the premises of which is physically located any such

covered establishment, and (B) which holds itself

out as serving patrons of such covered establishment.

(c) The operations of an establishment affect com

merce within the meaning of this title if (1 ) it is one

of the establishments described in paragraph (1 ) of

subsection (b); (2) in the case of an establishment

described in paragraph (2) of subsection (b), it serves

or offers to serve interstate travelers or a substantial

portion of the food which it serves, or gasoline or other

products which it sells, has moved in commerce; .. . and

(4) in the case of an establishment described in para

graph (4) of subsection (b), it is physically located

within the premises of, or there is physically located

within its premises, an establishment the operations

of which affect commerce within the meaning of this

subsection. . . .

Sec. 202. All persons shall be entitled to be free, at

any establishment or place, from discrimination or

segregation of any kind on the ground of race, color,

religion, or national origin, if such discrimination or

segregation is or purports to be required by any law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, rule, or order of a State

or any agency or political subdivision thereof.

Sec. 203. No person shall (a) withhold, deny, or

attempt to withhold or deny, or deprive or attempt to

deprive, any person of any right or privilege secured

2 0

by section 201 or 202, or (b) intimidate, threaten, or

coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce

any person with the purpose of interfering with any

right or privilege secured by section 201 or 202, or

(c) punish or attempt to punish any person for exer

cising or attempting to exercise any right or privilege

secured by section 201 or 202. [Emphasis added.]

It is clear that department store lunch counters, such as

those involved in these cases, fall within the terms of

§201 (c)(2), as quoted.1 The discrimination practiced in

these cases was, on the records, racial (R. Hamm 72-3

et passim. R. Lupper 27, 35, 36, 46, 50-51). Had these al-

1 The retail store lunch counters involved in these cases are

literally covered by the Act, for, being open to the general public

(R. Hamm 59-61, 66, 68; R. Lupper 47, 79), they “offer to serve

interstate travelers . . . ” §201 (b)(2), (c)(2). This statutory

language contains no requirement of “substantiality,” if that term

could have any meaning in this context. The Bill, as originally

introduced in the House by Congressman Celler as H.R. 7152, did

contain such a limiting requirement in Sec. 202 (a) (3) :

. . . (i) the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages,

or accommodations offered by any such place or establishment

are provided to a substantial degree to interstate travelers . . .

Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House Committee

on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., ser. 4, pt. 1, at 653

(1963).

This section of the act was changed to its present broader form

after passing through the full House Judiciary Committee. Mi

nority Report, H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 79 (1963).

The omission of a requirement of “substantiality” cannot have

been inadvertent, for there stands in immediate contiguity the

criterion, in the alternative, that a “substantial portion” of the food

served has moved in interstate commerce. “Offering to serve”

interstate travelers, as an alternative ground to actually serving

them, could hardly contain a “substantiality” requirement. It is

virtually impossible that an establishment which makes a principal

or massive appeal to interstate travelers would never serve one.

Yet, if some “substantiality” requirement be read into the “offer

to serve” criterion, that establishment would be the only one

brought within the Act independently by the “offer to serve” test.

Congress, in adding this language and eliminating the “substan-

2 1

leged offenses occurred after its passage, therefore, the

Civil Rights Act would furnish a complete defense, not

only because it is unthinkable that a state should be per

mitted to punish disobedience to an order the giving of

tiality” requirement, can hardly have meant to designate a class

that would be as good as empty.

This literal interpretation harmonizes completely with other

portions of the coverage section, for Congress obviously intended to

include virtually all hotels, gas stations, and places of amusement,

especially motion picture houses. Congressman Celler’s remarks,

in presenting the bill, state an intent to do, for the nation as a

whole, exactly what was done before in the 30 states having public

accommodation laws 110 Cong. Rec. 1456 (daily ed. Jan. 31, 1964).

He also spoke of the coverage of retail store lunch counters in terms

indicating that their simply being “public” was enough. Id. p. 1457.

This construction is eminently reasonable. It is the aggregate

rather than the individual effect of the prohibited practice that

counts, Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U. S. I l l , 127, 128; NLRB v.

Fairiblatt, 306 U. S. 601, 606, 607; United States v. Darby, 312

U. S. 100, 123; and it cannot be doubted that, if every restaurant

not principally or largely catering to interstate travelers were

segregated, the aggregate effect of the segregation of these thou

sands of restaurants would substantially inconvenience interstate

travel. The Negro interstate traveler wTould still be a second-class

interstate traveler, who could be confident of service only if he kept

blinders on and never left the principal routes of travel to see the

sights, to shop between trains, or to make any other of the depar

tures travelers customarily make from the shortest way.

What Congress seems to have done is to cover every lunch counter

that brings itself within the constitutional power of Congress by

virtue of its making any kind of an offer to serve a public that in

cludes interstate travelers, while leaving it open that some genu

inely eccentric case may present itself and be found outside of the

Act (cf. The ‘intrastate colored” lavatories that briefly flourished

a few years ago in railroad stations). NLRB v. Fainiiatt, supra,

at p. 607. That this is the right construction of the phrase in ques

tion is conclusively shown by the fact that the provision would be

virtually impossible to administer without it; a requirement that

every Negro desiring a meal face an argument about (and finally

the necessity of making an elaborate record on) the degree and

quality of an offer to serve interstate travelers, would as good as

nullify the Act. Particularly is this true of the use of the Act as a

defense in criminal prosecutions, a use whose contemplation by

Congress is proved with rare clarity by the legislative history. See

text, infra, pp. 22, 23.

2 2

which contravenes a federal right, but because such punish

ment is itself explicitly declared unlawful, in §203 (c),

supra. Senator Humphrey, floor manager for the bill in

the Senate, read into the record a Justice Department

statement containing this language:

It need hardly be added, however, that nothing in

section 205 (b) [now §207 (b), making the “remedies”

of the Act exclusive] precludes a defendant in a State

criminal trespass prosecution arising from a “sit in”

at a covered establishment from asserting the non

discrimination requirements of title II as a defense

to the criminal charge. The reference in section 205

(b) to “means of enforcing” the right created by title

II obviously does not deal at all with the question of

whether the right created by that title may be used as

a defense in criminal proceedings. Raising a defense

in a criminal case is not “enforcing” a right by a

“remedy” within the meaning of section 205 (b). That

section is intended to preclude only direct affirmative

action by the Government, or by a person aggrieved

acting as a plaintiff, pursuant to Federal laws other

than the provisions contained in title II. It is not in

tended and should not be read as precluding a plea in

a criminal prosecution, or an action for damages,

against a person availing himself of the Federal right

created by title II, that the criminal or civil action

against him is not well taken. That this is the proper

connotation of the title is made doubly clear by section

203 (c) which prohibits the imposition of punishment

upon any person “for exercising or attempting to exer

cise any right or privilege” secured by section 201 or

202. This plainly means that a defendant in a criminal

trespass, breach of the peace, or other similar case can

assert the rights created by 201 and 202 and that State

courts must entertain defenses grounded upon these

provisions. . . . 110 Cong. Rec. 9162-3 (daily ed. May

1, 1964).

In effect, the “offense” with which petitioners are charged

is now removed, by the paramount federal authority, from

the category of punishable crimes—exactly the thing that

happened with respect to the Maryland “offense,” when

that state passed the public accommodations law that was

the basis of the action taken by this Court in Bell v. Mary

land, ----- U. S. ——, 12 L. Ed. 2d 822, except that the

Civil Rights Act is stronger, since it contains that §203

(c) quoted in the preceding statement proffered by Sen

ator Humphrey, and directly forbidding “punishment” for

an attempt at exercising the named rights.

If these petitioners are now to be punished notwith

standing §203 (c), it will be for having insisted upon some

thing which the national conscience has now most decidedly

declared they are entitled to insist upon, against a refusal

which the national conscience has now declared affirma

tively unlawful. Their punishment can serve no purpose,

for no valid state or private interest can now be admitted

to exist in deterring them or others from doing what they

have done; the only licit deterrence interest now runs the

other way. Their punishment would afford the immoral

spectacle of pointless revenge against those whose claim,

substantially, has been validated by national authority.

Such a result ought to be allowed only if the law un

equivocally commands it. It is petitioners’ submission that

the law actually forbids it—that the Civil Rights Act of

1964 and especially its §203 (c), placed in the setting of

the ancient law expounded in this Court’s opinion in Bell

v. Maryland, supra, abates these prosecutions and forces

their remand for dismissal.

24

Not only the text but all the implications and radiations

of the Civil Eights Act are a part of federal law, overriding-

contradictory state law to their full extent. Gibbons v.

Ogden, 22 U. S. (9 Wheaton) 1; Sola Elec. Co. v. Jefferson

Elec. Co., 317 U. S. 173; Sperry v. Florida, 373 U. S. 379.

In the Sola case, this Court said, at p. 176:

It is familiar doctrine that the prohibition of a

federal statute may not be set at naught, or its benefits

denied, by state statutes or state common law rules.

In such a case our decision is not controlled by Erie R.

Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64. There we followed state

law because it was the law to be applied in the federal

courts. But the doctrine of that case is inapplicable

to those areas of judicial decision within which the

policy of the law is so dominated by the sweep of fed

eral statutes that legal relations which they affect must

be deemed governed by federal law having its source

in those statutes, rather than by local law. Royal In

demnity Co. v. United States, 313 U. S. 289, 296; Pru

dence Corp. v. Geist, 316 U. S. 89, 95; Board of Comm’s

v. United States, 308 U. S. 343, 349-50; cf. O’Brien v.

Western Union Telegraph Co., 113 F. 2d 539, 541.

When a federal statute condemns an act as unlawful,

the extent and nature of the legal consequences of the

condemnation, though left by the statute to judicial

determination, are nevertheless federal questions, the

answers to which are to be derived from the statute and

the federal policy which it has adopted. To the federal

statute and policy, conflicting state law and policy must

yield. Constitution, Art. VI, cl. 2; Awolin v. Atlas

Exchange Bank, 295 IT. S. 209; Deitrick v. Greaney,

309 U. S. 190, 200-01.

This Court, in fitting the statute into the complex web

of federal-state relations, must follow the method set out

25

in San Diego Building Trades Council, Millmen's Union,

Local 2020, Building Material and Dump Drivers, Local 36

v. Garmon, 359 U. S. 236, 239, 240:

The comprehensive regulation of industrial relations

by Congress, novel federal legislation twenty-five years

ago but now an integral part of our economic life, in

evitably gave rise to difficult problems of federal-state

relations. To be sure, in the abstract these problems

came to us as ordinary questions of statutory construc

tion. But they involved a more complicated and per

ceptive process than is conveyed by the delusive phrase,

“ascertaining the intent of the legislature.” Many of

these problems probably could not have been, at all

events were not, foreseen by the Congress. Others were

only dimly perceived and their precise scope only

vaguely defined. This Court was called upon to apply

a new and complicated legislative scheme, the size and

social policy of which were drawn with broad strokes

while the details had to be filled in, to no small extent,

by the judicial process.

(Cf. Van Beech v. Sabine Towing Co., 300 U. S. 342, 351.)

The classic doctrines of the two preceding quotations are

exactly applicable to the question of the abative effect of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on these prosecutions.

Apart from statute, the general federal rule is that a

change in the law, prospectively rendering that conduct in

nocent which was formerly criminal, abates prosecution

on charges of having violated the no longer existent law.

See Bell v. Maryland, supra, 12 L. Ed. 2d at p. 826, n. 2;

United States v. Chambers, 291 U. S. 217; United States

v. Tynen, 78 U. S. (11 Wall.) 88.

Though the case has apparently never arisen, there -would

seem to be no reason for the non-application of this rule

2 6

to the operation of a federal statute upon state prosecu

tions, where the federal statute has the effect (as the Civil

Bights Act of 1964 has with respect to these prosecutions)

of rendering lawful, in the name of the national authority

and interest, that which formerly was unlawful, and ren

dering unlawful the actions and claims of the person whose

interests are protected by the state’s prosecution, cf. Bell

v. Maryland, ----- U. S. at ----- , 12 L. Ed. 2d at 825.

Indeed, the case is a fortiori, for the national authority

is supreme.

Unless, therefore, there is statutory warrant for the

contrary conclusion, the effect of the Civil Bights Act of

1964, in its Sections 201 ff., must be to abate these prose

cutions.

The only relevant statutory provision is the first sentence

of the Act of February 25, 1871, B.S. 13, now codified in

1 U. S. C. §109, in the following terms:

§109. Bepeal of statutes as affecting existing liabilities.

The repeal of any statute shall not have the effect

to release or extinguish any penalty, forfeiture, or lia

bility incurred under such statute, unless the repealing

Act shall so expressly provide, and such statute shall

be treated as still remaining in force for the purpose

of sustaining any proper action or prosecution for the

enforcement of such penalty, forfeiture, or liability.

The expiration of a temporary statute shall not have

the effect to release or extinguish any penalty, for

feiture, or liability incurred under such statute, unless

the temporary statute shall so expressly provide, and

such statute shall be treated as still remaining in force

for the purpose of sustaining any proper action or

prosecution for the enforcement of such penalty, for

feiture, or liability.

27

Both as a matter of its own construction and because of

the existence of §203(c) of the Civil Rights Act, this statute

does not apply here. To it, first, may be directed, with even

stronger force, the remarks of this Court on the similar

Maryland statute, in Bell v. Maryland, supra, 12 L. Ed. 2d

at pp. 828, 829:

By its terms the clause does not appear to be applicable

at all to the present situation. It applies only to the

“repeal,” “repeal and re-enactment,” “revision,”

“amendment,” or “consolidation” of any statute or

part thereof. The effect wrought upon the criminal

trespass statute by the supervening public accommo

dations laws would seem to be properly described by

none of these terms. The only two that could even

arguably apply are “repeal” and “amendment.” But

neither the city nor the state public accommodations

enactment gives the slightest indication that the legis

lature considered itself to be “repealing” or “amend

ing” the trespass law. Neither enactment refers in any

way to the trespass law, as is characteristically done

when a prior statute is being repealed or amended.

This fact alone raises a substantial possibility that the

saving clause would be held inapplicable, for the clause

might be narrowly construed—especially since it is in

derogation of the common law and since this is a crim

inal case—as requiring that a “repeal” or “amendment”

be designated as such in the supervening statute itself.

The absence of such terms from the public accommo

dations laws becomes more significant vdien it is rec

ognized that the effect of these enactments upon the

trespass statute was quite different from that of an

“amendment” or even a “repeal” in the usual sense.

These enactments do not—in the manner of an ordinary

“repeal,” even one that is substantive rather than only

formal or technical—merely erase the criminal liability

that had formerly attached to persons who entered or

crossed over the premises of a restaurant after being-

notified not to because of their race; they go further

and confer upon such persons an affirmative right to

carry on such conduct, making it unlawful for the res

taurant owner or proprietor to notify them to leave

because of their race. Such a substitution of a right

for a crime, and vice versa, is a possibly unique phe

nomenon in legislation; it thus might well be con

strued as falling outside the routine categories of

“amendment” and “repeal.”

Of the two words here discussed, “amend” and “repeal,”

“amend” is the more nearly apt to describe the effect of the

Civil Rights Act on the trespass laws of the states, though

neither exactly answers, see Bell v. Maryland, supra, 12

L. Ed. 2d at pp. 828, 829. But the federal “saving clause,”

by its own terms, saves rights under the prior statute

only when “repeal” has taken place. While some lower fed

eral courts have held “amendment” tantamount to “repeal,”

in applying this statute, e.g. United States v. Taylor, 123

F. Supp. 920 (S. D. N. Y. 1954), this Court has never so

held. On the other hand, the literal force of “repeal,” was

insisted on, in another context, in Moore v. United States,

85 Fed. 465 (8th Cir. 1898). The word “repeal” cannot, in

any case, be stretched to cover the total reversal of law and

policy which The Civil Rights Act has effected on the per

missible applications of generally valid state trespass stat

utes. What has happened is not “repeal” but the affirmative

utterance of an overriding national judgment, practical

and moral, removing all taint from actions such as peti

tioners’, and declaring it to be a national wrong to deny

them service or to “punish” them for seeking service. This

is a “possibly unique phenomenon in [federal] legislation;”

see Bell v. Maryland, supra, 12 L. Ed. 2d at p. 829.

29

It is further, certain that the word “statute,” three times

used in the here relevant first sentence of 1 U. S. C. §109,

to denote the prior law that is “saved,” does not refer to

state enactments at all. This section now stands, and since

its enactment in 1871 always has stood, in a context dealing

entirely with federal enactments.2 There exists, moreover,

a sound policy reason for this limitation; it is one Congress

might sensibly have wished to make. For where criminal

liabilities are saved, the federal prosecutor, an officer re

sponsible ultimately to national authority, can use his dis

cretion to prevent a harsh application. If state criminal

liabilities were saved, in the face of a national determina

tion that the acts on which they rest ought not to be crim

inal, no such tempering of the rule, by any official respon

sible to the nation as a whole, would be possible. National

executive clemency would likewise be foreclosed.

An entirely independent and most compelling reason

exists for denying 1 IJ. S. C. §109 any application to the

2 The 1871 legislative history of the act from which 1 U. S. C.

§109 descends is wholly silent on this provision, except for a single

recitation of its content, without exegesis or comment. See Million,

Expiration or Repeal of a Federal or Oregon Statute as a. Bar to

Prosecution for Violations Thereunder. 24 Ore. L. Rev. 25, 31, 32

(1944). But the context of the discussion makes it plain that only

federal statutes were in Congress’ mind. The enactment was part

of an Act “Prescribing the form of the enacting and resolving

clauses of the acts and resolutions of Congress, and rules for the

construction thereof.” The other sections of the Act, three in num

ber, deal with form of enacting clauses, routine rules of construc

tion, and non-revival of repealed statutes by repeal of the repealing

Act. (Now 1 U. S. C. §§1 (in part), 101-104, and 108.) The dis

cussion touched on these sections, rather than on the one here of

interest. Cong. Globe, 41st Cong., 2d Sess. 2464 (1870); Id., 3rd

Sess. 775 (1871). The Forty-First Congress, with Mr. Conkling’s

voice so strong in this and other debates, was not one to which it is

reasonable to attribute a latent tenderness to states’ rights. On the

whole record of these debates, it is entirely plain that the applica

tion of the saving provision to state law was never thought of, and

that the whole focus of interest was the internal characteristics of

Acts of Congress, and their mutual relations.

30

present cases. That statute itself provides that the ‘‘pen

alty” shall be “extinguished” if the repealing act “so ex

pressly provide. . . . ” The Civil Rights Act of 1964, in its

Section 203, as seen above, forbids not only the withholding

of service at places of public accommodation, not only the

intimidation and coercion of persons seeking such service,

but also [§203(c)] punishing or attempting to punish “any

person for exercising or attempting to exercise any right

or privilege secured by section 201 or 202.” [Emphasis

added.] The present prosecutions would clearly fall under

this law, if the acts on which they are based had taken

place after July 2, 1964. They fall under the law, anyway,

if the word “secure” be taken in one of its normal dictionary

meanings (soundly rooted in its etymology and exemplified

in the last words of the Preamble to the Constitution of

the United States), “to put beyond the hazard of losing or

of not receiving.” Webster’s New International Dictionary,

2d ed., s.v. “secure” ; “To render safe, protect or shelter

from, guard against some particular danger . . . To make

secure or certain . . . ” New English Dictionary, s.v. “se

cure.” “Secure” is not an apt synonym for “create,” a

synonym necessary for referring §203(c) solely to the

period after July 2, 1964. It is an apt word for “making

safe that which already or independently exists,” and that

interpretation results in the literal applicability of §203 (c)

to these prosecutions.

The House Committee Report on the Civil Rights Act,

H. R. Report No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963), con

tains passages that corroborate the judgment that Con

gress, in considering the public accommodations title of

the bill, was thinking not only in terms of “rights” to be

created by it, but of “rights” already existent, at the very

least on the moral plane, which were to be “secured” by it.

The Report at p. 18 says, for example, that:

31

. . . Today, more than 100 years after their formal

emancipation, Negroes, who make np over 10 percent

of our population, are by virtue of one or another type

of discrimination not accorded the rights, privileges,

and opportunities which are considered to be, and must

be, the birthright of all citizens.

In the next paragraph, it is added:

. . . A number of provisions of the Constitution of

the United States clearly supply the means to “secure

these rights,” and H. R, 7152, as amended, resting upon

this authority, is designed as a step toward eradicat

ing significant areas of discrimination on a nationwide

basis. It is general in application and national in scope.

That this language refers, among other things, to the

public accommodations problem is made clear on the same

page, where it is said of the bill:

. . . It would make it possible to remove the daily

affront and humiliation involved in discriminatory de

nials of access to facilities ostensibly open to the gen

eral public . . .

This application is also suggested by specific statement

in the part of the Report at p. 20 dealing with public

accommodations:

Section 201 (a) declares the basic right to equal

access to places of public accommodation, as defined,

without discrimination or segregation on the ground

of race, color, religion, or national origin. [Emphasis

added.]

In the Senate, a textual change, highly significant here,

took place when, in §207(b), the phrase “based on this

title” was substituted for “hereby created,” in application

32

to the rights to public accommodation. Senator Miller of

Iowa, explaining, said:

One can get into a jurisprudential argument as to

whether the title creates rights. Many believe that the

title does not, but that the rights are created by the

Constitution. [Emphasis added.] 110 Cong. Rec. 12999

(daily ed. June 11,1964).

These passages make it plain that the Act was passed in

an atmosphere in which the “right” to non-discrimination

was conceived of, at least in part, as something that ex

isted before the bill, something that was recognized, de

clared, and protected, rather than being created, by the

bill. It is not necessary, and would probably be impossible,

to ascertain just how, in every context, this conception of

“right” functioned with other conceptions, or how it may

finally be fitted into the Act in all its parts. It suffices to

show, and the quoted passages do show, that there is nothing

unnatural in a construction of §203(c) to apply to the

punishment or attempted punishment of the claim of the

right to be free from discrimination, the same right “se

cured” and specially implemented by the law, but conceived

of as existing, at least morally, prior to its passage. On this

view, §203 (c) is tantamount to a specific shield against the

force of 1 U. S. C. §109, even if that section would have

applied in the absence of §203(c).

It is entirely plain that at least some of the “rights”

“secured” by Title II of the Civil Rights Act were neces

sarily conceived as preexisting the Act, as a matter of

strictest law, for Title II proscribes discrimination sup

ported by “state action” [§201(a) and (b)]. It is not con

troversial that such discrimination was unlawful before the

Act. Moreover, among the forms of “state action” said by

the Act to infect discrimination with illegality is state

33

“enforcement” of “custom” (§201(d)(2))—terminology

seemingly applicable to the very cases at bar (see Points

IIA and IIB, infra, pp. 46-57). In §203(e), Congress lumps

together all these “rights” without the slightest suggestion

of there being intended any distinction between them, with

respect to the present lawfulness of “punishing” their

assertion, whenever that assertion took place. It can hardly

be believed that Congress would have wished to present this