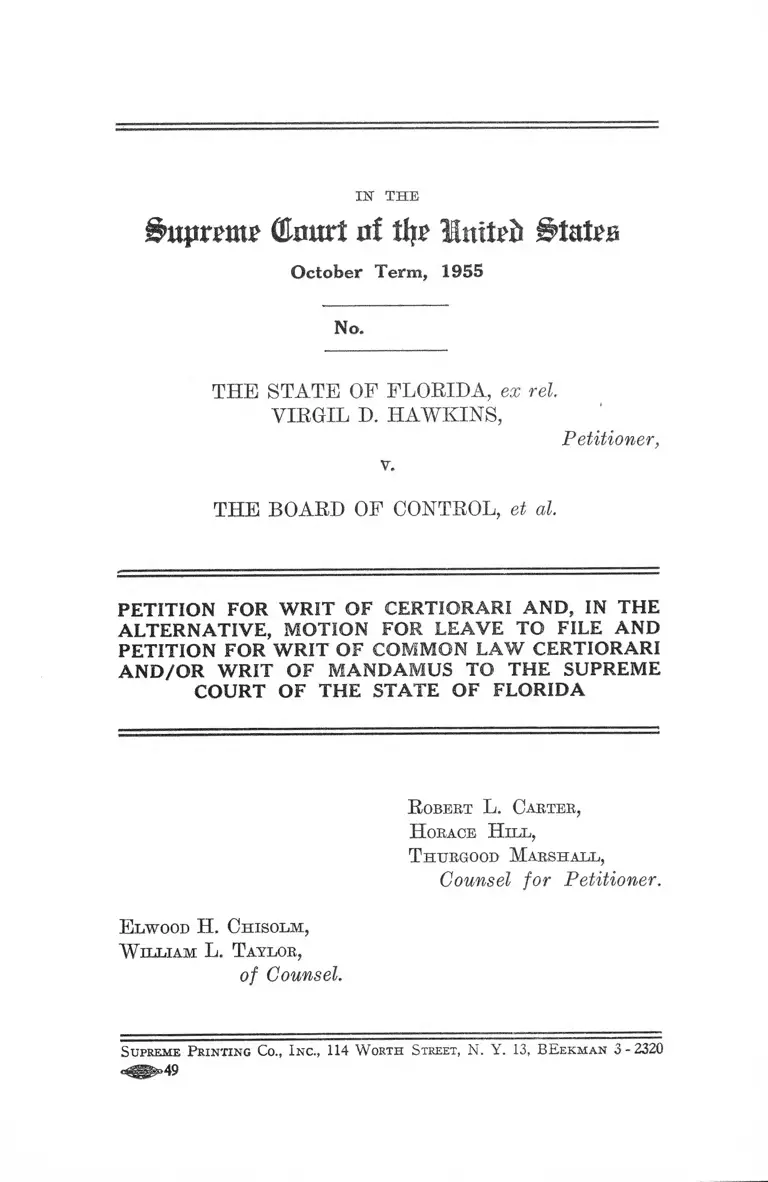

Hawkins v. Board of Control Petition for Writ of Certiorari and, in the Alternative, Motion for Leave to File and Petition for Writ of Common Law Certiorari and/or Writ of Mandamus to the Florida Supreme Court

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hawkins v. Board of Control Petition for Writ of Certiorari and, in the Alternative, Motion for Leave to File and Petition for Writ of Common Law Certiorari and/or Writ of Mandamus to the Florida Supreme Court, 1955. 20e37a03-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ad5d0430-bb55-4f0b-aeca-e372c6c6e91e/hawkins-v-board-of-control-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-and-in-the-alternative-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-petition-for-writ-of-common-law-certiorari-andor-writ-of-mandamus-to-the-florida-supreme-court. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

(Erntrt of % Inttefc States

October Term, 1955

No.

THE STATE OF FLORIDA, ex rel.

VIRGIL D. HAWKINS,

Petitioner,

v.

THE BOARD OF CONTROL, et at.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI AND, IN THE

ALTERNATIVE, MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND

PETITION FOR WRIT OF COMMON LAW CERTIORARI

AND/OR WRIT OF MANDAMUS TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

R obert L. Carter ,

H orace H il l ,

T htjrgood M a r sh a ll ,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H . C h is o l m ,

W il l ia m L. T aylor,

of Counsel.

Supreme P rinting Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3 - 2320

I N D E X

Motion for Leave to File Petition............................. 1

Petition for Writ of Certiorari................................ 3

Opinions Below.................................................. 4

Jurisdiction.......................................................... 5

Questions Presented .......................................... 7

Statement ........................................................... 8

Reasons for Allowance of the W ri t ....... ............. 10

Conclusion............................................ 15

Appendix A—Opinion and Order of the Supreme

Court of Florida .............................. 17

Appendix B—Motion for Extension of T im e......... 45

Table o f Cases Cited

Adkins v. E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 335 U. S.

331 .......................................................................... 7

Board of Supervisors v. Tureaud, 225 F. 2d 434 (CA

5th decided Aug. 23, 1955, 226 F. 2d 714 (decided

October 26, 1955), — F. 2d — (decided Jan. 6,

1956)........................................................................ 12

Booker v. Memphis State College, Civil No. 2656

(W. D. Tenn. 1955) unreported ............................. 13

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 ................................ 6

City National Bank v. Hunter, 152 U. S. 512............. 7

Constantine v. Southwestern Louisiana Institute, 120

F. Supp. 417 (W. D. La. 1954) ............................. 11

DeBeers Consolidated Mines v. United States, 325

U. S. 212 ................................................................. 6

PAGE

11

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F. 2d 180

(CA 6th 1955) ........................................................ 13

Ex Parte Bradley, 7 Wall. 364 ....... ......................... 7

Ex Parte Kawato, 317 U. S. 6 9 ................................ 6

Ex Parte Republic of Peru, 318 U. S. 578 .............. 6, 7

Far Eastern Conference v. United States, 342 U. S.

7 0 ........................................................... ................. 6, 7

Frazier v. Board of Trustees of University of North

Carolina, 134 F. Supp. 589 (M. D. N. C. 1955)__ 12

Grant v. Taylor, Civil Action No. 6404 (W. D. Okla.

1955) unreported ............................................. 12

Gray v. Board of Trustees of University of Tennes

see, 342 U. S, 517 .................................................. 11

Holmes v. Jennison, 14 Peters 614, Appx I I ......... 6

House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 4 2 ...................................... 7

In re 620 Church Street Building Corp., 299 U. S.

24 ......................................... 7

La Crosse Telephone Corp. v. Wisconsin Employ

ment Relations Board, 336 U. S. 1 8 ...................... 5

Lucy v. Adams, — U. S. —, 100 L. ed. (Advance

P- 17) .............................................. 10

McCargo v. Chapman, 20 How. 555 ......................... 7

McClellan v. Carland, 217 U. S. 268 ......................... 7

McCullough v. Cosgrove, 309 U. S. 634 .................... 6

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (CA 4th

1951) cert, denied, 341 U. S. 591 ....................... 10

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S.

637 ......................................................................... 10,14

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 __ 14

Mitchell v. Board of Regents of University of Mary

land, Docket No. 16, Folio 126 (Baltimore City

Court 1950) unreported ............................ 11

PAGE

I l l

Parker v. Illinois, 333 U. 8. 570 ............................. 5

Parker v. University of Delaware, 75 A. 2d 225 (Del.

1950)........................................................................ 10,11

Pope v. Atlantic Coast Line RR Co., 345 U. S. 379 .. 5

Re Metropolitan Trust Co., 218 U. S. 312................ 7

Republic Natural Gas Co. v. Oklahoma, 334 U. S. 62 5

School Segregation Cases (Brown v. Board of Edu

cation of Topeka), 347 U. S. 4830, 349 U. S. 294

9,10,11,12,13,14

Sibbald v. United States, 12 Peters 488 .................. 6

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 ................. 10,11

Spiller v. Atchison T. & S. F. R. Co., 253 U. S. 117 7

Swanson v. University of Virginia, Civil Action No.

30 (W. D. Va. 1950) unreported........................... 11

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ...........................10,11,14

Troullier v. Proctor, Civil Action No. 3842 (E. D.

Okla. 1955) unreported .................................. 12

Union Pacific R. Co. v. Weld Co., 247 U. S. 282 . . . . 7

United States Alkali Export Association v. United

States, 325 U. S. 126............................................... 6

Wells v. Dyson, Civil Action No. 4679 (E. D. La.

1955) unreported ...................................................... 12

White v. Smith, Civil Action No. 1616 (W. D. Tex.

1955) unreported........................................................ 12

Whitmore v. Stillwell, — F. 2d — (CA 5th decided

November 23, 1955) ................................................... 12

Wichita Falls Junior College Dist. v. Battle, 204 F.

2d 632 (CA 5th 1953), cert, denied, 347 U. S. 974 .. 11

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 92 F. Supp. 986

(E. D. La. 1950), aff’d, 340 U. S. 909 .................... 10

Wilson v. City of Paducah, 100 F. Supp. 116 (W. D.

Ky. 1951) ................................................................... 10

PAGE

IV

Statutes Cited

PAGE

Title 28, United States Code:

Section 1257(3) .................................................. 3, 5, 6

Section 1651(a) ................................................... 3,5,6

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment .................................... 4,14

Other A uthorities Cited

Moore, Commentary on the U. S. Judicial Code 598

(1949) ..................................................................... 6

Robertson and Kirkham, Jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court § 12 (Wolfson and Kurland ed. 1951) . . . . 6

Ferris, Extraordinary Legal Remedies, § 162 (1926) 6

Evasion of Supreme Court Mandate in Cases Re

manded to State Courts Since 1941, 67 Harv. L.

Rev. 1251 (1954) .................................................... 6

IN THE

&npxmj> Qkmrt of % Ittttefli States

October Term, 1955

No.

--------------------o---------- ---------

T h e S tate of F lorida , ex r e l . V ir g il D . H a w k in s ,

Petitioner,

v.

T h e B oard of C ontrol , et al.

------------------------- o-------------------

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE PETITION FOR WRIT

OF CERTIORARI AND/OR PETITION FOR

WRIT OF MANDAMUS

Now comes the petitioner and respectfully moves this

Court for leave to file the annexed petition for writ of cer

tiorari under Title 28, United States Code, Section 1651(a)

directed to the Supreme Court of the State of Florida to

review an order and judgment of that court entered on

October 19, 1955 and more particularly described in the

petition, and for such other and further relief as may be

just and proper.

In the alternative, petitioner moves for leave to file the

petition for writ of mandamus annexed hereto; and fur

ther moves that an order and rule be entered and issued

directing the Supreme Court of the State of Florida and the

Honorable E. Harris Drew, Chief Justice of the Supreme

Court of the State of Florida and the Honorable T. Frank

Hobson, Campbell Thornal, Glenn Terrell, Elwyn Thomas,

Stephen C. 0 ’Connell and B. K. Roberts, Associate Justices

of the Supreme Court of the State of Florida to show cause

why a writ of mandamus should not be issued against them

2

in accordance with the prayer of said petition and why

your petitioner should not have such other and further

relief in the premises as may be just and meet.

Further petitioner states that these motions and peti

tions annexed hereto are made as alternatives to the peti

tion for writ of certiorari also annexed hereto which

invokes the Court’s jurisdiction under Title 28, United

States Code, Section 1257(3), and are made in the event the

Court finds jurisdiction therein lacking and refuses to grant

the petition for writ of certiorari filed pursuant to that

statutory authority.

R obert L. Carter,

T htjrgood M a rsh a ll ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, New York.

H orace, H il l ,

610' Second Avenue,

Daytona Beach, Fla.,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H . C h is o l m ,

W il l ia m L. T aylor,

of Counsel.

3

IN THE

Sutprem* (Emtrl of % llnltvh

October Term, 1955

No.

o

T h e S tate oe F lorida, ex e e l . V ir g il D . H a w k in s ,

Petitioner,

v.

T h e B oard of C ontrol , et al.

-------------------o-------------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI AND, IN THE

ALTERNATIVE, PETITION FOR WRIT OF COMMON

LAW CERTIORARI, AND/OR PETITION FOR WRIT

OF MANDAMUS TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

Petitioner prays that pursuant to Title 28, United States

Code, Section 1257(3) a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Florida entered in

the above-entitled cause on October 19, 1955.

In the alternative, petitioner prays that pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1651(a) a writ of

certiorari issue to review the judgment entered in the

aforesaid cause under which petitioner was refused an

order requiring Ms immediate admission to the University

of Florida subject only to the same rules and conditions

applicable to all other persons, and was denied such relief

pending the taking of evidence by an officer of the court

below to determine the time when, and under what circum

stances, petitioner’s unquestioned right of admission to the

University of Florida should and would be vindicated.

4

Petitioner prays as a further alternative that a writ of

mandamus issue to the Supreme Court of Florida and to

the Honorable E. Harris Drew, Chief Justice of that Court

and the Honorable T. Frank Hobson, Campbell Thornal,

Glenn Terrell, Elwyn Thomas, Stephen C. O’Connell and

B. K. Roberts, Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of

Florida, directing and requiring the said Honorable E.

Harris Drew, T. Frank Hobson, Campbell Thornal, Glenn

Terrell, Elwyn Thomas, Stephen C. O’Connell and B. K.

Roberts to enter an order requiring petitioner’s immediate

admission to the University of Florida law school in accord

with petitioner’s right to equal educational opportunities

as secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

O pinions B elow

The first opinion was entered in this case on August 1,

1950 and is reported at 47 So. 2d 608. A second opinion

was entered on June 15, 1951 and is reported at 53 So.

2d 116. Petition for writ of certiorari was denied by this

Court, 342 U. S. 877. The third opinion of the Supreme

Court of the State of Florida was entered on August 1,

1952, and is reported at 67 So. 2d 162. When review of

that judgment was sought here, this Court granted the

petition for writ of certiorari, vacated the judgment and

remanded the cause “ for consideration in the light of the

Segregation Cases decided May 17, 1954 . . . and conditions

that now prevail” , 347 U. S. 971. Pursuant to the mandate

of this Court, the cause was returned to the Supreme Court

of Florida and on October 19, 1955, that court entered the

instant judgment which is reported at 83 So. 2d 20 and

review of which is herein sought.

5

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of the State of

Florida was entered on October 19,1955, and a copy thereof

is appended to this petition in Appendix A at pages

17-44. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257(3). Petitioner

submits that the judgment below, while on its face not a

final disposition of all the issues, subjects him to irrepar

able injury by refusing to recognize his constitutional claim

to equal educational opportunities as being immediate and

present. Petitioner has already lost 6 years. Presumably

he could now have finished his course and entered upon the

practice of law had his constitutional rights been properly

and seasonably settled by the court below. No matter what

the ultimate decision of Florida may be, petitioner will

have and is suffering irremedial and irreparable injury.

The decision rendered, disposes of petitioner’s rights under

the Federal Constitution under a formula contrary to the

decisions of this Court and adverse to petitioner’s inter

ests. Moreover, further delay in granting him immediate

redress could well effectively deprive petitioner completely

of his constitutional rights. As such the judgment below

is properly reviewable under Title 28, United States Code,

Section 1257(3). See Pope v. A tlantic Coast Line R. R. Co.,

345 U. S. 379, 382, 383; La Crosse Telephone Corp. v. Wis

consin Employment Relations Roar cl, 336 U. S. 18; Parker

v. Illinois, 333 U. S. 570; Republic Natural Gas Co. v. Okla

homa, 334 U. S. 62.

Despite the considerations hereinabove cited, this Court

may find that it is without jurisdiction to review the deci

sion below under Title 28, United States Code, Section

1257(3). In that eventuality jurisdiction is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1651(a) to aid the

Court in the exercise of its appellate jurisdiction over state

coui'ts granted under Title 28, United States Code, Section

1257(3).

6

If this Court has no jurisdiction under Title 28, United

States Code, Section 1257(3), petitioner seeks relief under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1651(a) either by

issuance from this Court of a writ of common law certiorari

or by writ of mandamus because no other remedy is avail

able by which he may secure redress of his right to equal

protection of the laws.

Where this Court would have jurisdiction under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1257(3) but for the fact

that the judgment appealed from is not final, this Court

has power to issue an extraordinary writ authorized by

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1651(a). Ex Parte

Republic of Peru, 318 U. S. 578. Writs may be issued to

state courts as well as to federal courts. Sibbald v. United

States, 12 Peters 488, 493; Holmes v. Jevmison, 14 Peters

614, 632, Appx. I I ; cf. Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 304

(dissenting opinion). See Moore, Commentary on the

U. S. Judicial Code 598 (1949); Robertson and Kirkham,

Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court §12 (Wolfson and

Kurland ed. 1951); Ferris, Extraordinary Legal Remedies,

§ 162 (1926); Note, Evasion of Supreme Court Mandate

in Cases Remanded to State Courts Since 1941, 67 Harv.

L. Rev. 1251, 1259 (1954).

This Court, in the exercise of its sound discretion, has

issued extraordinary writs of mandamus or common law

certiorari: (1) where the issue involved the propriety of

a lower court’s exercise of equity jurisdiction, United

States Alhalai Exp. Assoc, v. United, States, 325 U. S. 196

(certiorari); Ex Parte Kawato, 317 U. S. 69 (mandamus);

(2) where a petitioner would have suffered an irremediable

loss of rights if compelled to await a final judgment before

seeking review, DeBeers Consolidated Mines v. United

States, 325 U. S. 212 (certiorari); McCullough v. Cos-

grave, 309 U. S. 634; Ex Parte Republic of Peru, supra

(mandamus); (3) where issues of public importance were

involved, Far Eastern Conference v. United States, 342

7

U. S. 570 (certiorari); Ex Parte Republic of Peru, supra

(mandamus); and (4) as a means of “ furthering justice

in other kindred ways”, Re 620 Church Street Building

Corp., 299 U. 8.24, 26 (certiorari). See also Spiller v. Atchi

son T d SFR Co., 253 U. S. 117; McClellan v. Carland, 217

U. S. 268; Adkins v. E. I. DuPont de Nemours d Co., 335

U. S. 331; Union Pacific R. Co. v. Weld County, 247 U. S.

282; House v. Mayo, 324 U. S. 42 (certiorari); McCargo

v. Chapman, 20 How 555, 557; Ex Parte Bradley, 7 Wall.

364, 376 (mandamus). The extraordinary writ of man

damus also has been issued to secure compliance with a

prior mandate of this Court, City National Bank v. Hunter,

152 U. S. 512; Re Metropolitan Trust Co., 218 IT. 8. 312.

As noted, infra, in “ Reasons for Allowance of the W rit”,

all of these factors justifying the issuance of the extra

ordinary writs of mandamus or common law certiorari

obtain in the instant case.

Q uestions Presented

Is petitioner entitled to an order requiring his imme

diate admission to the University of Florida Law School

subject only to the same terms and conditions as are ap

plicable to other persons and without distinction or dis

crimination based upon his race or his color?

May the court below defer petitioner’s admission to

the University of Florida until it has received evidence

from a master as to law and fact designed to guide the

court in determining when, in the public’s interest, peti

tioner’s admission should be ordered and the terms and

conditions under which the same should be allowed?

8

Statem ent

This cause originated in April, 1949. Petitioner was one

of four applicants who sought admission to the profes

sional and graduate schools of the University of Florida.

Petitioner seeks entrance to the school of law. On May

13, 1949, petitioner was advised that his admission to the

University of Florida was prohibited because he was a

Negro, and the Board of Control offered to pay his tuition

to an institution of his choice outside the state. Petitions

for alternative writs of mandamus were filed in the Su

preme Court of the State of Florida and were granted

(E. 8). On August 1,1950, the court below entered its first

judgment and ruled that the Board of Control, in ordering

the establishment of schools of law, pharmacy, graduate

courses in agriculture and chemical engineering at Florida

A. and M. College for Negroes and in offering to provide

out-of-state scholarship aid to petitioner pending estab

lishment of these segregated educational facilities, had

fully satisfied the state’s constitutional obligation to fur

nish equal educational opportunities to petitioner and

other Negroes similarly situated. The court refused to

enter a final order but retained jurisdiction in order to

permit the parties to seek further relief at some later

date (E. 48). On May 16, 1951, petitioner filed a motion for

peremptory writ of mandamus (E. 67). On June 15, 1951

the court below denied the peremptory writ (E. 68), and

petitioner filed a petition for writ of certiorari in this

Court. This Court refused to grant the petition for writ

of certiorari on the grounds that no final judgment had

been entered, 342 U. S. 877.

On August 1, 1952, the Supreme Court of Florida en

tered final judgment in this case denying petitioner’s

motion for peremptory writ, quashing the alternative writs

of mandamus previously issued and dismissing the cause

(E. 86). When the cause was brought here a second time,

9

this Court granted the petition for writ of certiorari,

vacated the judgment below, and remanded the cause for

consideration in the light of the School Segregation Cases

(Brown v. Board of Education), 347 U. S. 483.

On July 31,1954, the Supreme Court of Florida ordered

the petitioner to amend his petition so as to place before

that court the issues raised by the original petition in the

light of the School Segregation Cases, decided May 17,1954,

and conditions that now prevail (R. 95). On September 30,

1954, an amended petition for writ of mandamus was filed

in the court below (R. 133), and thereafter, an amended

answer was filed by respondents (R. 97)—all pursuant to

the court’s instruction. The cause was argued before the

Supreme Court of Florida in January, 1955, and on October

19, 1955, the present judgment was entered (R. 104).

Under this most recent decision of the court below, the

esclusion of petitioner from the University of Florida

solely because of his race was declared unconstitutional,

and a master was appointed to take evidence pursuant to

which the court below will determine when and under what

circumstances petitioner and other Negroes may be ad

mitted to the University of Florida in the indeterminate

future. The master was given four months to take evi

dence and make his report. To petitioner’s knowledge,

no steps have been taken as of this date—some 90 days

subsequent to the decision of the court below to gather the

evidence and make the report authorized by the court’s

decision. In fact, the state has just made application to

extend until July 2, 1956, the time when that report should

be made. A copy of their application served on counsel

for petitioner on January 12 past is set forth and appended

hereto as Appendix B at pages 45-47.

Thus, the undisputed facts are that as of now, almost

7 years have elapsed since petitioner first applied to the

University of Florida, and he is still awaiting a decision

ordering his admission.

10

R easons for A llow ance o f the W rit

1. Petitioner is entitled to an order requiring his imme

diate admission to the University of Florida law school.

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 641; Sweatt y. Painter,

339 U. S. 629; MeLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

U. 8. 637; Lucy v. Adams, — U. 8. -—, 100 L, ed. (Adv.

p. 17). The decision below to postpone immediate relief

and to determine at some subsequent time when and in

what form petitioner’s right to relief will be granted, based

upon evidence to be adduced by an officer of the court,

constitutes in effect a denial of petitioner’s right. We

submit that the formula laid down in Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U. S. 294, for ending segregation in the

public schools is not applicable to state junior colleges,

colleges, graduate and professional schools. The May 31,

1955, formula was designed to give public officials, who had

to undertake necessary administrative planning, such as

redistricting, reassignment of pupils, reorganization of

schools and staff, time essential to free a public school

system of color discrimination in compliance with the

law. The removal of racial barriers with respect to ad

mission to state junior colleges, colleges, graduate or

professional schools involves no such administrative prob

lems and, indeed no administrative considerations of any

complexity whatsoever. These schools merely have to adopt

and enforce rules and regulations pursuant to which quali

fied Negro applicants are admitted on the same basis as

other persons. Most of the institutions in this category,

which have removed racial barriers pursuant to court deci

sions, have removed these barriers at once. See Sweatt v.

Painter, supra; MeLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents,

supra; McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (CA 4th

1951), cert, denied, 341 U. S. 591; Wilson v. Board of

Supervisors, 92 F. Supp. 986 (ED La. 1950), aff’d, 340

U. S. 909; Parker v. University of Delaware, 75 A. 2d 225

11

(Del. 1950); Wichita Falls Junior College Dist. v. Battle,

204 F. 2d 632 (CA 5th 1953), cert, denied, 347 IT. S. 974;

Constantine v. Southwestern Louisiana Institute, 120 F.

Supp. 417 (WD La. 1954); Wilson v. City of Paducah, 100

F. Supp. 116 (WD Ky. 1951); Mitchell v. Board of Regents

of University of Maryland, Docket #16, Folio 126 (Balti

more City Court 1950) unreported; Swanson v. University

of Virginia, Civil Action No. 30 (WD Va. 1950) unreported;

and see Gray v. Board of Trustees of University of Tennes

see, 342 U. S. 517. It should be pointed out, parenthetically

at least, that in the cases cited the courts had not aban

doned the “ separate but equal” doctrine. Even so, relief was

considered warranted immediately when its need was dem

onstrated. The considerations cited by the court below

for postponing immediate relief in the removal of segrega

tion concern themselves, in the main, not with administra

tive difficulties hut with questions of supposed adverse

public sentiment which, as this Court pointed out in its

May 31 order, could not be the basis for a denial of constitu

tional rights.

2. This case raises a constitutional question of great

public importance. Prior to decision by this Court on

May 31, 1955, in the School Segregation Cases, 349 U. S.

294, the law was apparently clear that in respect to state

junior college, college, graduate and professional educa

tion a showing that equal educational opportunities had

been denied on the basis of race or color entitled the appli

cant to relief in the form of a court order compelling his

admission to the state junior college, college, graduate or

professional school instanter. See Sweatt v. Painter and

cases listed, supra. It was considered settled constitutional

doctrine that the right to equal educational opportunities is

personal and present, Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra,

and that at the college, graduate and professional school

level these rights, when established, would be vindicated

immediately.

12

After decision by this Court in the School Segrega

tion Cases, 349 U. S. 294, question, whether the formula

there set forth, which permitted the grant of a reasonable

time to school officials to comply with the constitutional

proscription against segregation in public education, was

applicable to areas other than elementary and secondary

schools, has caused some confusion and no little concern.

In Tureaud v. Board of Supervisors, there was contro

versy and confusion in the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit as to whether that formula was applicable in a

case involving a Negro’s right of admission at the college

level of the University of Louisiana. Two conflicting

opinions resulted, and the controversy had to be referred

to the court en banc and a third opinion rendered before

the matter could be finally settled in terms of a grant of

immediate relief in accord with the decision of the trial

court. See 225 F. 2d 434 (decided August 23, 1955) 226

F. 2d 714 (decided October 26, 1955), and — F. 2d —

(decided January 6, 1956).1

In Frasier v. Board of Trustees of University of North

Carolina, 134 F. Supp. 589 (MD NC 1955) immediate relief

was granted. This was true in Whitmore v. Stillwell,

— F. 2d — (CA 5th decided November 23, 1955);

White v. Smith, Civil Action No. 1616 (WD Tex. 1955)

unreported; Wells v. Dyson, Civil Action No. 4679 (ED

La. 1955) unreported; Trouiller v. Proctor, Civil Action

No. 3842 (ED Okla. 1955) unreported; Grant v. Taylor,

Civil Action No. 6404 (WD Okla. 1955) unreported.

In Lucy v. Adams, supra, this Court vacated a super

sedeas so that immediate relief could be obtained by the

Negro applicants so that they could receive the benefits of

1 There were, of course, other points of difference in this case,

but one of the basic disputes was whether the criteria set down by

this Court on May 31, 1955, should have been applied by the trial

court.

13

an equal education, pending disposition of the procedural

and substantive considerations by the appellate courts.

On the other hand in Booker v. Memphis State College

(Civil No. 2656, W. D. Tenn. 1955), not yet reported and

now pending on appeal, the court took the position that

six years was a reasonable time to allow for the institution

to end its discriminatory practices'—such elimination to

begin at the graduate level and end at the first year level

six years hence—the level at which application had been

made.

In the instant case, after six years of litigation and

acknowledgment by the court below that the exclusion from

the University based upon race is unconstitutional, the

court felt it had authority under the decisions of this Court

to further defer petitioner’s admission to the University

and to approve a plan which would allow the University a

period of time to eliminate its discriminatory practices.

In Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F. 2d 180

(CA 6th 1955) the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

felt the formula of gradual compliance was applicable to

public housing.

These two approaches are at war and cannot be recon

ciled. Indeed, under the latter approach, the decision of

May 17, 1954, in the School Segregation Cases which broke

with the “ separate but equal” doctrine in the field of public

education means that Negro applicants at the college and

graduate levels are now entitled to less protection than they

were before “ separate but equal” was abandoned. We can

not believe this to be the Court’s intention, and clarifica

tion and settlement of this question is of primary im

portance.

3. This Court must review this case in order to pre

vent a gross miscarriage of justice. When the Supreme

Court of Florida handed down its first decision in August

14

1950, in which, it held out-of-state scholarship aid and a

promise to establish separate schools for Negroes to be a

satisfaction of the state’s obligation under the Fourteenth

Amendment, this Court had long since condemned the out-

of-state scholarship device as a failure to comply with the

requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment, Missouri ex

rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, and had established

standards in Sweatt v. Painter, supra; McLaurin v. Okla

homa State Regents, supra, which, if applied, would have

resulted in petitioner’s admission to the University of

Florida. Two years later the court below dismissed the

petition for writ of mandamus, still clinging to the notion

that segregation at the graduate and professional school

level was permissible. Now, although it is recognized that

the School Segregation Cases (Brown v. Board of Educa

tion), 347 U. S. 483, have broken with the “ separate but

equal” doctrine, petitioner’s enjoyment of his right to

equal educational opportunities is still deferred. Already

over 6 years have elapsed since petitioner first applied for

admission to the University, and the end of his wait for vin

dication of his rights is not yet in sight. The state’s motion

for extension of time (see Appendix B) makes that all too

clear. We submit that petitioner is entitled to the support

and protection of this Court in vindication of his claim,

and that this petition should be granted to review and deter

mine that question,

4. The court below in deferring decision on petitioner’s

request to be admitted to the University of Florida has

failed to follow the mandate of this Court. The court was

instructed to consider the case in the light of the School

Segregation Cases, decided May 17, 1954. The court below

adopted and followed a suggested formula announced by

the Court a year later in May, 1955. We submit this was

error and abuse of discretion. This petition should be

granted to review and correct this error and flagrant abuse

of discretion.

15

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the reasons hereinabove stated, it is

respectfu lly subm itted that this petition for writ o f

statutory certiorari should be granted and, in the alter

native, that this petition for writ of common law cer

tiorari should be granted, an d /or a writ o f m andamus

issue from this Court directed to the Supreme Court

o f the State o f F lorida and the H onorable E. Harris

Drew, the C hief Justice o f the Supreme Court o f the

State o f F lorida and the H onorable Glenn Terrell,

B. K. Roberts, Stephen C. O ’Connell, Elwyn Thomas,

T. Frank H obson and Campbell Thornal, the A ssociate

Justices o f the Supreme Court o f the State o f Florida,

requiring said C hief Justice and A ssociate Justices to

show cause on a day to be fixed by this Court w hy a

writ o f m andamus should not issue from this Court

ordering petitioner’s adm ission w ithout further delay

to the U niversity o f Florida School of Law.

R obert L. Carter ,

H orace H il l ,

T hurgood M arsh a ll ,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H . C h is o l m ,

W il l ia m L. T aylor,

of Counsel.

17

A PPEN D IX A

O pinion and Order o f the Supreme Court

o f Florida

Dated October 19, 1955

R oberts, J . :

This cause came on for reconsideration in accordance

with the mandate of the Supreme Court of the United

States entered on May 24, 1954. The history of the case

is set forth in State ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control of

Florida, et al., (Fla.) 47 So. 2d 608; (Fla.) 53 So. 2d 116,

cert. den. 342 U. S. 877, 72 S. Ct. 166, 96 L. Ed. 659; (Fla.)

60 So. 2d 162, cert, granted 347 U. S. 971, 74 S. Ct. 783, 98

L. Ed. 1112. By and through this litigation, the relator

seeks admission to the College of Law of the University of

Florida on the basis that it is a tax-supported institution,

that he is in all respects qualified, and that his admission

has been refused solely because he is a member of the negro

race. His admission was denied by this court and his cause

dismissed on August 1, 1952, for the reason that there was

available to him adequate opportunity for legal education

at the LawT School of the Florida A. & M. University, an

institution supported by the State of Florida for the higher

education of negroes, and that, although the facilities were

not identical, they were substantially equal and were suffi

cient to satisfy his rights under the “ separate but equal”

doctrine announced by the Supreme Court of the United

States in 1896, in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, and

subsequent cases. See State ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of

Control, supra, 60 So. 2d 162.

The relator appealed our decision to the Supreme Court

of the United States, where it was considered with other

comparable appeals there, one of which was Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka. On May 17, 1954, the

Supreme Court of the United States handed down its first

18

opinion in the Brown case (reported in 347 U. S. 483, 74

S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873, 38 A. L. R. 2d 1180), by which it

announced the end of segregation in the public schools

and rejected the “ separate but equal” doctrine established

in Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, in the following language:

“ In Sweatt v. Painter, supra [339 U. S. 629, 70

S. Ct. 848, 94 L. Ed. 1114] in finding that a segre

gated law school for Negroes could not provide them

equal educational opportunities, this Court relied in

large part on ‘those qualities which are incapable

of objective measurement but which make for great

ness in a law school.’ In McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, supra, [339 U. S. 637] the Court, in

requiring that a Negro admitted to a white graduate

school be treated like all other students, again re

sorted to intangible considerations: ‘. . . his ability

to study, to engage in discussions and exchange

views with other students, and, in general, to learn

his profession.’ Such considerations apply with

added force to children in grade and high schools.

To separate them from others of similar age and

qualifications solely because of their race generates

a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the com

munity that may affect their hearts and minds in a

way unlikely ever to be undone. . . .

“ Whatever may have been the extent of psycho

logical knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson,

this finding is amply supported by modern authority.

Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to

this finding is rejected.

“ We conclude that in the field of public educa

tion, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no

place. Separate educational facilities are inherently

unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and

others similarly situated for whom the actions have

Appendix A

19

been brought are, by reason of the segregation com

plained of, deprived of the equal protection of the

laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This

disposition makes unnecessary any discussion

whether such segregation also violates the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

On May 24, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United

States vacated our judgment of August 1,1952, and directed

our reconsideration of the instant case in the light of its

opinion of May 17, 1954, in the Brown case, supra [347

U. S. 483] “ and conditions that now prevail.” Under

order of this court, all pleadings were brought down to

date and now pose the single question of whether or not

the relator is entitled to be admitted to the University of

Florida Law School upon showing that he has met the

routine entrance requirements. In its May 17, 1954, opin

ion in the Brown case, the Supreme Court of the United

States reserved jurisdiction for the purpose of making

further orders, judgments and decrees and, pursuant to

that reservation of jurisdiction, on May 31, 1955, entered a

supplemental opinion (reported in 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed.

653, and referred to hereafter as the “ implementation

decision” ) in which it said:

‘ ‘ Full implementation of these constitutional prin

ciples may require solution of varied local school

problems. School authorities have the primary re

sponsibility for elucidating, assessing, and solving

these problems; courts will have to consider whether

the action of school authorities constitutes good faith

implementation of the governing constitutional prin

ciples. Because of their proximity to local condi

tions and the possible need for further hearings, the

courts which originally heard these cases can best

perform this judicial appraisal. Accordingly, we

believe it appropriate to remand the cases to those

courts.

Appendix A

20

“ In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles. Tra

ditionally, equity has been characterized by a practi

cal flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a

facility for adjusting and reconciling public and

private needs. These cases call for the exercise of

these traditional attributes of equity power.

“ At stake is the personal interest of the plain

tiffs in admission to public schools as soon as prac

ticable on a non-discriminatory basis. To effectu

ate this interest may call for elimination of a variety

of obstacles in making the transition to school sys

tems operated in accordance with the constitutional

principles set forth in our May 17, 1954, decision.

Courts of equity may properly take into account the

public interest in the elimination of such obstacles

in a systematic and effective manner. But it should

go without saying that the vitality of these consti-

tional principles cannot be allowed to yield simply

because of disagreement with them.

“ While giving weight to these public and pri

vate considerations, the courts will require that the

defendants make a prompt and reasonable start

toward full compliance with our May 17,1954, ruling.

Once such a start has been made, the courts may

find that additional time is necessary to carry out

the ruling in an effective manner. The burden rests

upon the defendants to establish that .such time is

necessary in the public interest and is consistent

with good faith compliance at the earliest practicable

date. To that end, the courts may consider prob

lems related to administration, arising from the

physical condition of the school plant, the school

and transportation system, personnel, revision of

school districts and attendance areas into compact

units to achieve a system of determining admission

Appendix A

21

to the public schools on a non-racial basis, and revi

sion of local laws and regulations which may be

necessary in solving the foregoing problems. They

will also consider the adequacy of any plans the

defendants may propose to meet the problems and

to effectuate a transition to a racially non-discrimi-

natory school system. During this period of transi

tion, the courts will retain jurisdiction of these

cases.

“ The judgments below, except that in the Dela

ware case, are accordingly reversed and remanded

to the district courts to take such proceedings and

enter such orders and decrees consistent with this

opinion as are necessary and proper to admit to

public schools on a racially non-discriminatory

basis with all deliberate speed the parties to these

cases. . . .

“ It is so ordered.”

Article VI of the Constitution of the United States pro

vides, among other things, the following:

“ This Constitution, and the Laws of the United

States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof;

and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under

the Authority of the United States, shall be the

supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every

State shall he hound thereby, any Thing in the Con

stitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary not

withstanding.” (Emphasis added.)

The theory of “ separate but equal” facilities under

which this state has developed its educational system since

Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, was decided in 1896, has been

abolished by the decision of the Supreme Court in Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, supra, 347 U. S. 483; and

Appendix A

22

we deem it to be our inescapable duty to abide by tbis deci

sion of the United States Supreme Court interpreting the

federal constitution. It therefore follows that the respond

ents may not lawfully refuse to admit the relator to the

University of Florida Law School merely because he is a

member of the negro race and “ separate but equal” facili

ties have been provided for him at a separate law school.

Nor can we sustain the contention of respondents that “ the

adverse psychological effect of segregation on Negro chil

dren on which the case of Brown v. Board of Education,

supra, rested would have no application to the petitioner

who is a college graduate and 48 years of age,” which they

present in defense of their action in refusing to admit

relator to the University of Florida Law School.

The respondents also state, however, as a third de

fense to such action, that “ the admission of students of

the Negro race to the University of Florida, as well as to

other institutions of higher learning established for white

students only, presents grave and serious problems affect

ing the welfare of all students and the institutions them

selves and will require numerous adjustments and changes

at the institutions of higher learning; and respondents

cannot satisfactorily make the necessary changes and ad

justments until all questions as to time and manner of

establishing the new order shall have been decided on the

further consideration by the United States Supreme Court

. . .” This, in my opinion, constitutes a valid defense to

issuance of the peremptory writ at this time.

The “ implementation decision” of May 31, 1955, quoted

at length above, does not impose upon the respondents a

clear legal duty to admit the relator to its Law School

immediately, or at any particular time in the future; on

the contrary, the clear import of this decision—and, indeed,

its express direction—is that the state courts shall apply

equitable principles in the determination of the precise

time in any given jurisdiction when members of the negro

Appendix A

23

race shall be admitted to white schools. The Supreme

Court of the United States said in that decision that these

cases call for the exercise by the courts of the traditional

powers of an equity court with particular reference tc

“ its facility for adjusting and reconciling public and pri

vate needs,” and the “ practical flexibility in shaping its

remedies.” In entering its “ implementation decision,” it

is very likely that the high court had before it, and may

well have considered, the decision of this court rendered

November 16, 1954, in Board of Public Instruction v. State,

75 So. 2d 832, in which, speaking through Mr. Justice Ter

rell, we discussed the necessity of gradual de-segregation,

and, among other things, said:

“ School systems are developed on long range

planning. Since the Brown case reverses a trend

that has been followed for generations certainly

there should be a gradual adjustment from the exist

ing segregated system to the non-segregated system.

This is the more true in most of the states with

segregated school systems because plants and phy

sical facilities have not kept pace with the growth of

population, hence they are bursting at the seams

from overcrowded conditions.

# # *

“ . . . When desegregation comes in the democratic

way it will be under regulations imposed by local

authority who will be fair and just to both races in

view of the lights before them. If it come in any

other way it will follow the fate of national prohibi

tion and some other ‘noble experiments.’ If there

is anything settled in our democratic theory, it is

that there must be a popular yearning for laws that

invade settled concepts before they will be enforced.

The U. S. Supreme Court has recognized this.”

Appendix A

24

The respondents have alleged that the admission of

negroes to the institutions of higher learning under their

jurisdiction and control “ presents grave and serious prob

lems affecting the welfare of all students and the institu

tions themselves and will require numerous adjustments

and changes at the institutions of higher learning; . . .”

And, under the express language of the “ implementation

decision,” this court “ may properly take into account the

public interest in the elimination of such obstacles in a

systematic and effective manner.” Moreover, the relator

has chosen as the vehicle for enforcing his lawful right in

this court our extraordinary remedy of mandamus, and

it has long been held in this state that the granting of the

writ of mandamus “ is governed by equitable principles,

and that the enforcement of the writ if granted may he

modified or postponed in particular circumstances when

the carrying it out according to the strict letter of the

command would be of no great advantage to the relator

but would tend to work a serious public mischief, or result

in irreparable injury or embarrassment in the orderly

functioning of the government with regard to its financial

affairs, unless so restricted.” City of Safety Harbor v.

State (1939) 136 Fla. 636, 187 So. 173. See also State ex

rel. Carson v. Bateman, 131 Fla. 625, 180 So. 22; State

ex rel. Gibson v. City of Lakeland, 126 Fla. 342, 171 So.

227; State ex rel. Bottome v. City of St. Petersburg, 126

Fla, 233, 170 So. 730.

It is our opinion that, both under the equitable princi

ples applicable to mandamus proceedings and the express

command of the United States Supreme Court in its “ im

plementation decision” the exercise of a sound judicial dis

cretion requires this court to withhold, for the present, the

issuance of a peremptory writ of mandamus in this cause,

pending a subsequent determination of law and fact as to

the time when the relator should be admitted to the Uni

versity of Florida Law School; and, to that end and for

Appendix A

25

that purpose, Honorable John A. H. Murphree, Circuit

Judge, is hereby appointed as a commissioner of this court

to take testimony from the relator and respondents and

such witnesses as they may produce, material to the issues

alleged in the third defense of the respondents, as follows:

“ That the admission of students of the negro

race to the University of Florida, as well as to other

state institutions of higher learning established for

white students only, presents grave and serious

problems affecting the welfare of all students and

the institutions themselves, and will require numer

ous adjustments and changes at the institutions of

higher learning; and respondents cannot satisfac

torily make the necessary changes and adjustments

until all questions as to time and manner of estab

lishing the new order shall have been decided on the

further consideration thereof by the United States

Supreme Court, at which time the necessary adjust

ments can be made as a part of one over-all pattern

for all levels of education as may be finally deter

mined, and thereby greatly decrease the danger of

serious conflicts, incidents and disturbances,”

and with directions to file a transcript of such testimony

without recommendations or findings of fact to this court

within four months from the date hereof; such testimony

to be limited in scope to conditions that may prevail, and

that may lawfully be taken into account, in respect to the

College of Law of the University of Florida.

We adopt this procedure pursuant to the directive of

the “ implementation decision” to the effect that we retain

jurisdiction “ during this period of transition” so that we

“ may properly take into account the public interest” as

well as the “ personal interest” of the relator in the elimi

nation of such obstacles as otherwise might impede a sys

Appendix A

26

tematic and effective transition to the accomplishment of

the results ordered by the Supreme Court of the United

States. Based upon such evidence as may be offered at

the hearing above directed, this court will thereupon deter

mine an effective date for the issuance of a peremptory

writ of mandamus.

It is so ordered.

D r e w , C. J., H obson and T h o r n a l , JJ., concur.

T er r ell , J., concurs specially.

T h o m a s and S eek in g , JJ., concur in part and dissent in

part.

Appendix A

T e r r ell , J., concurring with R oberts, J . :

I agree with the opinion of Mr. Justice Roberts. Were

it not for the far-reaching effect of Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, hereinafter referred to as the Brown

case, I would refrain from expanding my concurrence.

The Brown case, reported in 347 U. S. 483, 98 L. Ed. 873,

38 A. L. R. 2d 1180, was decided May 17, 1954. The gist

of the court’s opinion rejected the doctrine of “ separate

but equal”, pronounced in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S.

537, and held that racial segregation in the public schools

was discriminatory and unconstitutional and had no place

in the field of public education.

The case was restored to the docket for further con

sideration with reference to formulating a final decree

which was promulgated May 31, 1955, reported in 75

S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 653. (Pertinent part of text quoted

in opinion of Mr. Justice Roberts.) It reiterated the hold

ing of May 17,1954, but remanded the cause to the Federal

Court from which it originated with instruction to con

sider problems related to administration arising from

physical condition of school plant, school transportation

27

system, personnel, revision of school districts, attendance

areas, local laws and regulations that may be proposed

by school authorities to effectuate a transition to racially

non-segregated schools.

The inferior federal courts, said the Supreme Court,

may determine whether or not proposals to implement the

decision are sufficient to establish a racially non-discrimina-

tory school system. In implementing its determination that

recial discrimination in the public schools is unconstitu

tional, the inferior federal courts, sitting as courts of

equity, “ will be guided by equitable principles characterized

by a practicable flexibility in shaping its remedies, and by

a facility for adjusting and reconciling public and private

needs.”

This opinion will be directed to a discussion of what

I conceive to be the import of the last sentence in the pre

ceding paragraph. It is not a criticism of the Brown case

but a defense of the equities herein pointed out and others

that may arise. I trust that it will be of aid to school

authorities in working out this vexatious problem. Florida

and every state with a segregated school system will be

confronted with a host of problems in shifting from a

segregated to a non-segregated school system. Some of

these problems will be common but many of them will be

different. In requiring the inferior federal courts to be

“ guided by equitable principles characterized by a practic

able flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility

for adjusting and reconciling public and private needs”,

what did the Supreme Court mean? The answer to this

question is the most important aspect of the decision

because it is not only the guide for inferior federal courts

to interpret the proposals of local school authorities to

comply with the law, but the Department of Education

will be expected to follow it in shaping its pattern for

a desegregated university and public school system.

The Brown case throws no light whatever on this point,

nor are we enlightened by a study of the facts in that

Appendix A

Appendix A

case. It arose in the State of Kansas where less than

three percent of its school population is Negro. There

is a respectable body of opinion in the country which

subscribes to the view that transition from segregated

to desegregated schools in states where the Negro popula

tion is very small, not exceeding eight or ten percent of

the whole population, will be a simple matter. This is

true because many of these states have never had a segre

gated system and those which have had such a system have

not been required to incur the heavy burden that the

segregated school system requires.

In Florida the ratio of white school population to Negro

school population is approximately 79 to 21. In some of

the states with segregated schools the ratio of white to

Negro school population is approximately 50 to 50. Other

segregated states have ratios between these two extremes.

In said states, segregation has been the school pattern

since the public school system was instituted. Billions of

dollars have been expended by them in providing and

improving physical school facilities, the preparation of

teachers and provision for other equipment to raise the

general standard of education. All of this expenditure

was based on legislative and judicial assurance that it was

proper school policy. Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, and other

cases, upholding the doctrine of “ separate but equal”

facilities for the races heretofore alluded to. Now after

generations the same court which decided Plessy v. Fergu

son, and after the states with segregated school systems

in reliance on it had spent many billions of dollars in

providing the latest approved school equipment, has decided

that it is unconstitutional and must be discarded. This

in the face of the fact that there is no local agitation for

the change. It seems to me that these circumstances sug

gest equity enough to stay desegregation until the schools

provided in reliance on the doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson

have ceased to be adequate and must be replaced by others

to meet the new requirement.

29

There is an, intangible aspect to the integrated school

question that speaks louder for equity than the one dis

cussed in the preceding paragraph. It has to do with the

diverse moral, cultural and I. Q. or preparation response

of the white and Negro races. It may also be said to

embrace the economy of the Negro teachers. Account of

the differential these factors present, it is a matter of

common knowledge that whites and Negroes in mass are

totally unprepared in mind and attitude for change to

non-segregated schools. The degree of one’s culture and

manners may resolve these differentials, but they will not

resolve under the impact of court decrees or statutes.

Closing cultural gaps is a long and tedious process and is

not one for court decree or legislative acts. I content

myself with merely calling attention to this aspect of the

segregation question. The confusion, frustration and

disaster that will result from failure to take it into account

can best be presented to the federal courts and adjudicated

by them when a concrete case arises making it necessary

to invoke “ equitable principles characterized by practicable

flexibility.” There is no known yardstick to measure the

equity that this observation may provoke. Innate defi

ciencies in self-restraint and cultural acuteness always

engender stresses, especially when they are infected with a

racial element that is difficult to control.

Since the effect of desegregation on Florida is of

primary concern at the present, it would be impressive

to consider a concrete example at close range. The ratio

of white to Negro population in Leon County is 60 to 40.

Most of the Negroes are residents of the section known

as “ Frenehtown” and the area near “ Bond School” .

In fact Lincoln High and Bond School are located to

accommodate these communities. Leon High, Sealey, Kate

Sullivan and others are located to accommodate white

children in the communities surrounding them. The whites

and the Negroes in other words voluntarily segregate

Appendix A

30

themselves by community. Leon County has millions of

dollars invested in school plants and school facilities all

of which are crowded. This is the rule in Florida and

in other areas in states where segregation is the rule.

If “ equitable principles characterized by practicable

flexibility” is to be the rule, can desegregation mean that

the public school program of Leon County is to be scrapped

and another instituted at the cost of millions to the tax

payers so that Negro and white children can attend the

same school. Reduced to the language of the street,

“ equity” or “ equitable principles” is nothing more than

a polite name for the plowboys’ concept of justice.

In the western part of the City of Tallahassee, Florida

State University with approximately 7,000 white students

is located and in the southwestern part of the city, about

one mile away, Florida A. & M. University with approxi

mately 3,000 colored students is located. The state has

many millions of dollars invested in buildings and equip

ment to administer these institutions, both of which are

crowded. If ‘ ‘ equitable principles characterized by practic

able flexibility” is to be the guide, does desegregation mean

that attendance at these institutions is to be scrambled

and one of them abandoned and the other enlarged at great

expense in order that white and Negroes may attend the

new school. A negative answer to this question would

appear to be evident.

I might venture to point out in this connection that

segregation is not a new philosophy generated by the states

that practice it. It is and has always been the unvarying

law of the animal kingdom. The dove and the quail, the

turkey and the turkey buzzard, the chicken and the guinea,

it matters not where they are found, are segregated; place

the horse, the cow, the sheep, the goat and the pig in the

same pasture and they instinctively segregate; the fish in

the sea segregate into “ schools” of their kind; when the

goose and duck arise from the Canadian marshes and take

Appendix A

31

off for the Gulf of Mexico and other points in the south,

they are always found segregated; and when God created

man, he allotted each race to his own continent accord

ing to color, Europe to the white man, Asia to the yellow

man, Africa to the black man, and America to the red man,

but we are now advised that God’s plan was in error and

must be reversed despite the fact that gregariousness has

been the law of the various species of the animal kingdom.

In a democracy, law, whether by statute, regulation or

judge made, does not precede, but always follows a felt

necessity or public demand for it. In fact when it derives

from any other source, it is difficult and often impossible

to enforce. The genius of the people is as resourceful in

devising means to evade a law they are not in sympathy

with as they are to enforce one they approve. The early

patriots turned Boston harbor into a teapot one night

because they did not like the tax on tea. President Jackson

is said to have once defied the order of the Supreme Court

and challenged them to enforce it. He did not subtract

from his fame or his integrity in doing so. Our country

went to war to overthrow the Dred Scott decision and

prohibition petered out, was made a campaign issue and

was repealed because sympathy for it was so indifferent

that it could not be enforced.

States with segregated schools have them from a deep-

seated conviction. They are as loyal to that conviction as

they are to any other philosophy to which they are devoted.

They are as honest and law-abiding as the people of any

state where desegregation is the rule. Convinced as they

are of the justice of their position, they will not readily

renounce it if they are required to forfeit abruptly their

conviction and their investment, are not convinced that

their position is wrong or are required to adopt a system

not shown them to be an improvement over the one they

are required to forfeit.

If “ equitable principles characterized by practicable

flexibility” is to be the polestar to guide the courts and

Appendix A

32

school authorities in the solution of this question, I think

the potential sources of equity pointed out herein are so

impelling that desegregation in the public schools must

come by sane and sensible application of the equities

pointed out herein, including others that will arise, to the

facts of the particular case. I think the local school

authorities have the character, integrity and the good

judgment required to do this. The Supreme Court used

the Brown case as the criterion to evolve the decree that

we are confronted with, the circumstances out of which

it arose are so different from those which precipitated the

case at bar that I do not think it (Brown case) rules the

instant case. It is true that cases from South Carolina,

Virginia and the District of Columbia were before the

court and were considered with the Brown case but the

latter appears to have been the basis of decision. Desegre

gation in the public schools will be much more difficult than

desegregation in the institutions of higher learning.

In the case at bar relator seeks entry to the law school,

comparable to the graduate school of the University of

Florida. I think when required showing is made Ms

case will be ultimately controlled by Sweat! v. Painter,

339 U. S. 629, 94 L. Ed. 1114; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State

Regents, 339 U. S. 637, 94 L. Ed. 1149; Sipuel v. Board of

Regents, 322 U. S. 631; Lucy, et al. v. Adams, et al., decided

October 10, 1955, and similar cases, but I think the plead

ings here raise questions or equities that should be resolved

by evidence. The opinion of Mr. Justice Roberts provides

the orthodox method to explore these equities for which

I feel impelled to concur.

It is so ordered.

Appendix A

33

S e b r i n g , J. concurring in part and dissenting in part:

This cause is now before the Court for a reconsidera

tion of the issues, pursuant to the mandate of the Supreme

Court of the United States entered May 24, 1954.

For a complete history of the case see State ex rel.

Hawkins v. Board of Control of Florida, et al. (Fla.), 47

So. 2d 608; (Fla.), 53 So. 2d 116, cert. den. 342 U. S. 877,

72 S. Ct. 166, 96 L. Ed. 659; (Fla.),, 60 So. 2d 162, cert,

granted 347 U. S. 971, 74 S. Ct. 783, 98 L. Ed. 1112.

The cause was initiated by the relator, Hawkins, when

he filed a petition for an original writ of mandamus to

require the Board of Control of Florida to admit him as a

student to the College of Law of the University of Florida,

a tax-supported institution maintained for white persons

only. In his petition Hawkins averred that he possessed

all the educational and moral requirements and qualifica

tions necessary for admission to the College but that the

Board had refused to admit him solely because he was

a Negro.

In a return filed to an alternative writ issued in the

cause the respondents admitted that they had refused to

admit Hawkins to the College of Law of the University of

Florida but that they had offered to admit him to the

College of Law of the Florida A. & M. University, a tax-

supported institution established and maintained for Negro

students only, and that at the latter institution he would

be afforded opportunities and facilities for study that were

substantially equal to those afforded white students at the

University of Florida.

After the return had been filed, the respondent filed

a motion for the entry of a peremptory writ the return

notwithstanding on the ground that the return showed

affirmatively that the relator was entitled to the relief

for which he had prayed. The motion was denied, and

the cause was dismissed on August 1, 1952, for the reason

that although the facilities offered members of the white

Appendix A

34

and Negro races to obtain an education were not identical

they were substantially equal and this satisfied the require

ments of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Con

stitution, under the principle enunciated in Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 41 L. Ed. 256, 16 S. Ct. 1138,

and kindred cases.

After the judgment had been entered the relator filed

a petition in the Supreme Court of the United States for

a writ of certiorari to review the judgment. On May 24,

1954, that court granted the petition for certiorari, vacated

our judgment, and remanded the cause to this Court with

directions that the cause be reconsidered “ in the light of

the Segregation Cases decided May 17, 1954, Brown v.

Board of Education, etc., and conditions that now pre

vail . . . in order that such proceedings may be had in the

said cause, in conformity with the judgment and decree

of this [United States Supreme] Court above stated, as,

according to right and justice, and the Constitution and

laws of the United States, ought to be had therein. . . .”

State ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 347 U. S. 971,

74 S. Ct. 783, 98 L. Ed. 1112.

Pursuant to the mandate of the Supreme Court of the

United States, this Court, on July 31, 1954, entered an

order directing the relator to amend his original petition

in mandamus “ so as to place before this Court the issues

raised by the original petition ‘ in the light of the Segrega

tion Cases decided May 17, 1954, Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, etc., and conditions that now prevail,’ ” and directing

the respondents “ to amend their return so as to present

to this Court any answer they may have to said amended

petition which will enable this Court to carry out the

mandate of the Supreme Court of the United States.”

Thereafter, the relator filed an amended petition in

which he averred, in substance, that he possessed all the

educational and moral qualifications necessary for admis

sion to the College of Law of the University of Florida;

that he had an A. B. degree from Lincoln University,

Appendix A

35

Pennsylvania; that he had duly applied for admission to

said College of Law but had been refused admission

“ solely because of certain provisions of the Constitution

and Statutes of the State of Florida which deny the right

of your petitioner admission to the said University solely

because of . . . petitioner ’s race and color, thus denying . . .

petitioner the equal protection of laws solely on the ground

of Ms race and color, contrary to the Constitution of the

United States . . . that in addition to the College of Law

of the University of Florida, the board of Control by

legislative authority and from public funds has established,

supported and maintained the Florida Agricultural and

Mechanical College of law specifically for Negroes only;”

that the Board has “ refused to admit your petitioner to

the University of Florida solely because of race and color

but have offered admittance to the Florida Agricultural

and Mechanical College of Law on the basis of his race and

color. That the arbitrary and illegal refusal and offer

of admittance to the respective colleges by the respondents

are in violation of the equal protection of the laws guaran

teed by the Constitution of the State of Florida and of

the United States in light of the decision handed down

on May 17,1954 by the Supreme Court of the United States

in Brown v. The Board of Education, et al. That the

separate educational facilities hereinbefore alleged are

inherently unequal. That by virtue of the segregation

complained herein your petitioner has been deprived of

the equal protection of the laws guaranteed under and

by virtue of the 14th amend [sic] of the Constitution.”

In due course the respondents filed an amended return

to the amended petition admitting all of the material

allegations of the return, except that they denied that

the separate educational facilities which respondent had

been offered were unequal, and denied that the segrega

tion complained of deprived the relator of the equal pro

tection of the law guaranteed to him by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constituution of the United States.

Appendix A

36

The cause is now before this Court for final decision

on the amended petition, the amended return, and the

motion of the relator for a judgment in his favor the

allegations of the amended return to the contrary notwith

standing.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483,

74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. Ed. 873, 38 A. L. R. 2d 1180, which

we have been directed by the Supreme Court of the United

States to consider in our determination of the right of the

relator to the relief prayed, was decided on May 17, 1954,

some nine months after the judgment of dismissal was

entered by this Court in the case at bar. It was a suit

brought by a Negro to gain admission to a public school

maintained exclusively for white children and involved the

question as to whether or not the “ segregation of children

in the public schools solely on the basis of race, even

though the physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors

may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group

of equal educational opportunities.” Except for the fact

that the school facilities involved were maintained for

grade and high school students, and not for college students,

the essential facts in the Brown case are identical with

those presented by the amended petition of the relator.

In arriving at its conclusion that the facilities main

tained by the Board of Education of the City of Topeka

did not afford to the children of that city the equal educa

tional opportunities which the Federal Constitution re

quires, the Supreme Court of the United States had this

to say:

“ In Sweatt v. Painter [339 U. S. 629, 70 S. Ct.

848, 94 L. Ed. 1114], [this Court] in finding that a

segregated law school for Negroes could not provide

them equal educational opportunities . . . relied in

large part on ‘those qualities which are incapable

of objective measurement but which make for great

Appendix A

37

ness in a law school.’ In McLanrin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, 339 U. S. 637, 94 L. Ed. 1149, 70

S. Ct. 851, . . . the Court, in requiring that a Negro

admitted to a white graduate school be treated like

all other students, again re-sorted to intangible con

siderations: ‘. . . his ability to study, to engage in

discussions and exchange views with other students,