Memoranda from Coke to Ellis Re: Bifurcation of Desegregation Cases in the Federal Courts; Attorney Notes

Working File

July 15, 1992 - July 20, 1992

22 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Memoranda from Coke to Ellis Re: Bifurcation of Desegregation Cases in the Federal Courts; Attorney Notes, 1992. fb60a4e2-a246-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ad5e88b9-1795-4a68-8f95-a34d9597acf1/memoranda-from-coke-to-ellis-re-bifurcation-of-desegregation-cases-in-the-federal-courts-attorney-notes. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

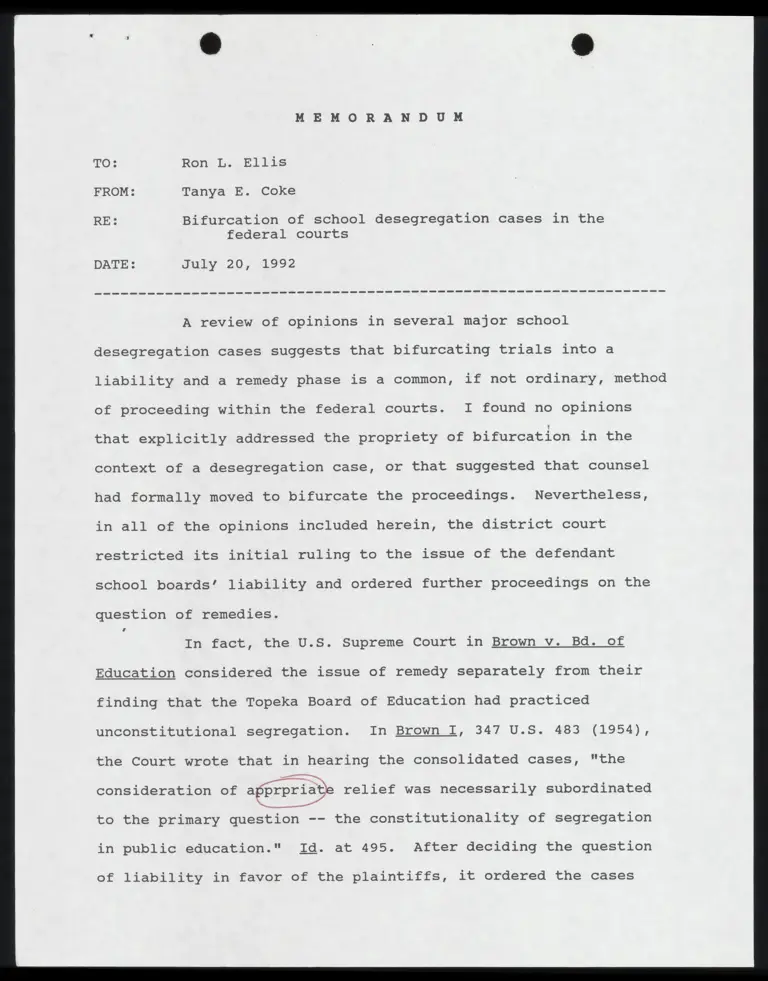

MEMORANDUM

70: Ron L. Ellis

FROM: Tanya E. Coke

RE: Bifurcation of school desegregation cases in the

federal courts

DATE: July 20, 1992

A review of opinions in several major school

desegregation cases suggests that bifurcating trials into a

liability and a remedy phase is a common, if not ordinary, method

of proceeding within the federal courts. I found no opinions

that explicitly addressed the propriety of bifurcation in the

context of a desegregation case, or that suggested that counsel

had formally moved to bifurcate the proceedings. Nevertheless,

in all of the opinions included herein, the district court

restricted its initial ruling to the issue of the defendant

school boards’ liability and ordered further proceedings on the

question of remedies.

’

In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Bd. of

Education considered the issue of remedy separately from their

finding that the Topeka Board of Education had practiced

unconstitutional segregation. In Brown I, 347 U.S. 483 (1954),

the Court wrote that in hearing the consolidated cases, "the

consideration of agprpriate relief was necessarily subordinated

to the primary question -- the constitutionality of segregation

in public education." Id. at 495. After deciding the question

of liability in favor of the plaintiffs, it ordered the cases

2

restored to the docket and requested the parties to present

further argument on the question of relief as previously

formulated by the Court.'Id. See also Brown II, 349 U.S. 298,

299 (1955). The Court reasoned that a separate and more detailed

briefing was needed "in order that we may have the full

assistance of the parties in formulating decrees." Id. Among

the remedial questions to be decided in Brown II was how the

Ld

district courts should be instructed to arrive specific terms for

decrees in school desegregation cases. Brown, 347 U.S. at 495,

n. 13. Ultimately, the Court held that trial courts must work

with school officials in shaping remedies ("school authorities

have primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing and

solving these problems . . .). Brown, 349 U.S. 298, 299 (1958),

In Taylor v. Board of Education, 191 F.Supp. 181

(S.D.N.Y. 1961), a suit brought by black parents against the New

! The Court framed the remedial issues as follows: "Assuming

it is decided that segregation in public schools violates the

Fourteenth Amendment

(a) would a decree necessarily follow providing that,

witin the limits set by normal geographic school

districting, Negro children should forthwith be admitted

to schools of their choice, or (b) may this Court, in the

exercise of its equity powers, permit an effective

gradual adjustment to be brought about from existing

segregated systems to a system not based on color

distinctions? . . . (a) should this Court formulate

detailed decrees in these cases; (b) if so, what specific

issues should the decres reach; (c) should this Court

appoint a special master to hear evidence with a view to

recommending specific terms for such decrees; (d) should

this Court remand to the courts of firs instance with

directions to frame decrees in these cases, and if so

what general directions should the decrees of this Court

include and what procedures should the courts of first

instance follow in arriving at the specific terms of more

detailed decrees?" Brown, 347 U.S. at 495.

| »

%® 0

3

Rochelle Board of Education, the district court held that the

defendants had intentionally maintained a segregated school

system in violation of onstituion and the dictates of Brown v.

v

Board of Education. While the opinion is unclear as to whether

the court actually barred testimony as to remedy during the

course of the trial, in concluding his order Judge Kaufman wrote

that it was "unnecessary at this time to determine the extent to

which each of the items of the relief requested by plaintiffs

will be afforded." Id. at 198. Instead, the court stated that

it would defer consideration of remedies until the school board

had presented a plan for desegregation, "said Yesesvenation to

begin no later than the start of the [following] school year."

Id. When school officials later tried to appeal the order and

extend the date set for filing a desegregation plan, the Second

Circuit dismissed the action for want of jurisdiction on the

basis that the district court’s order was not yet final. Taylor

v. Board of Education, 288 F.2d 600, 602 (2d Cir. 1961). The

’

court held that when a district court has simply found

segregation by a school board to be unconstitutional and has

directed the board promptly to submit a plan for remedying it,

without any further "injunction," the decision is not complete,

and therefore not appealable. Id. at 602.

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed, 402 U.S. 1, 28 L.Ed.2d 554, 91 S.Ct. 1267

(1971), that a school board has broad discretion to formulate

educational policy, including plans to remedy racial segregation

4

within their school systems. The court in Swann wrote that

"absent a finding of a constitutional violation," such remedy

formulation "would not be within the authority of a federal

court." Swann, 402 U.S. at 16. Only where a school system has

defaulted on their obligation to proffer an acceptable plan for

desegregation, the court held, would the courts have the power to

fashion a remedy to assure a unitary school system. Id. This

language in Swann appears to endorse, if not mandate, a two stage

proceeding in which school authorities, once held liable under

Brown, are to be afforded the opportunity to formulate and

present a plan before the district court orders remedial action.

Since Swann, the district courts have continued to hear

cases in more or less informally bifurcated proceedings. In

United States v. Board of School Commissioners of Indianapolis,

332 F.Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971), aff’d, 474 F.2d 81 (7th Cir.

1973), cert. denied, 413 U.S. 920 (1973), the district. court

prihcipally addressed itself to two issues relating to liability:

whether the school district had deliberately pursued a policy of

segregating black students from white students as of the date of

the Brown I decision; and if so, whether the Board had since

changed its policy to eliminate such desegregation. In its

opinion finding the school board in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, the district court did order the board to adopt a

number of specific remedies immediately. These included the

reassignment of faculty, the relocation of a black high school,

and the implementation of a voluntary transfer policy that would

5

enhance desegregation. Id. at 678, 680. However, the court

stated that it also "[r]ecogniz[ed] that the orders thus far made

will not result in significant desegregation of majority black

schools immediately, unless the voluntary transfer . . . policies

are unusually successful," and therefore ordered defendants to

file comprehensive plans for racial desegregation with the court

before the start of the next school term. Id. at 681. The court

announced that it would hear and decide the question of further

remedies separately in a later proceeding. Id. In an opinion

issued four years later, the district court ordered the busing of

¥

black students to outlying districts. U.S. v. Bd. of Sch.

commissioners of Indianapolis, 419 F.Supp. 180 (1975). This and

subsequent orders on the issue of appropriate remedies were also

separately appealed. See U.S. v. Bd. of Sch. Commissioners, 541

F.2d 1211 (1976), vacated and remanded, 429 U.S. 1068, 97 S.Ct.

802, 650 L.Ed.2d 786 (19717).%

* The litigation around the desegregation of Boston’s public

schools in the mid-1970’s explicitly followed dual lines of

inquiry. In its initial order, the district court described the

15-day trial in Morgan v. Hennigan, 379 F.Supp. 410 (D.Mass.

1974) as one that "concerned only the liability issues of the

2 The U.S. Supreme Court remanded the case for reconsi-

deration of mixed questions of liability and remedy in what became

an interdistrict case (i.e., whether the district court had

jurisdiction to compel desegregation remedies affecting outlying

suburban corporations). See School Bd. of Indianapolis, 573 F.2d

400 (7th Cir. 1978); 456 F.Supp. 183 (S.D. Ind. 1978); 506 F.Supp.

657 (S.D. Ind. 1979) (remedy only).

: L

6

case, as contrasted with issues relating to the possible remedy."

Id. at 416. Judge Garrity wrote that "[t]he court’s primary task

is to determine whether the defendants have intentionally and

purposefully caused or maintained racial segregation in

meaningful or significant segments of the Boston public school

system in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment." Id. at 425.

The court went on to examine for evidence of intentional

discrimination the school board’s policies toward districting,

student transfers, the assignment and promotion of faculty and

staff, utilization of facilities, and admission to its vocational

and college preparatory campuses. After finding that the

defendants had purposefully acted with discriminatory intent to

segregate, Judge Garrity declared that "the defendants are under

an ’affirmative obligation’ to reverse the consequences of their

unconstitutional conduct." Id. at 482. The court broadly

outlined several "remedial guidelines" for fulfilling this

obligation, but scheduled for the following week a separate

hearing to consider the details of a state plan for desegregation

already then under proposal.®? Id. at 483. Judge Garrity also

ordered defendants to "begin forthwith the formulation and

implementation of plans which shall eliminate every form of

3 These remedial guidelines were limited to broad statements

to the effect, for example, that the primary responsibility for

desegregation lay with the school committee; that school

authorities have the affirmative duty to take whatever steps are

necessary (including busing, redistricting, and involuntary school

and faculty assignments) to achieve a unitary system; and that the

time allowed for compliance would be only that reasonably necessary

to design and implement a remedial plan. Id. at 482.

7

racial segregation in the public schools of Boston . . . I 14.

at 484.

The appeal to the First Circuit was similarly limited to the

district court’s findings on liability because (in the words of

the court of appeals) the district court, "(h]aving found such

deliberate design [to segregate], left the question of remedy to

a future time." Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509 F.2d 580, 583 (1st Cir.

1974). In a separate opinions issued some two years later, the

district court addressed the remedy phase of the Boston school

case. Morgan v. Kerrigan, 401 F.Supp. 216 (D.Mass. 1975). At

{

issue on appeal to the First Circuit in Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530

F.2d 401 (1st Cir. 1976) was whether the defendants could

present, "for purposes of tailoring remedies," evidence of

residential segregation during the remedy phase of the case, once

the liability phase had been concluded. Id. at 407. The court

of appeals described the history of the bifurcated proceedings in

the case as follows:

"The liability phase came to an end in 1974 with a

district court finding of substantial segregation in

the entire school system intentionally brought about

and maintained by official action over the years.

Morgan v. Hennigan, 379 F.Supp. 410 (D.Mass. 1974). We

affirmed, Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509 F.2d 580 (lst Cir.

1974), and the Supreme Court denied certiorari, 421

U.S. 963, 95 S.Ct. 1950, 44 L.Ed.2d 449 (1975). While

the liability issues were being considered on appeal,

the district court, after its decision on June 21,

1974, began its exploration of appropriate remedies.

The period from June, 1974, to May, 1975, was occupied

with the addition of parties to the litigation,

hearings as to the nature, scope and objectives of a

plan, submission and criticism of various plans,

consideration of all proposals and preparation of a

plan by a panel of masters, and, finally, the issuance

of a revised plan by the district court on May 10,

8

1975, followed by a Memorandum Decision and Remedial

Order.

Morgan, 530 F.2d at 405-406. One of the defendant organizations

had attempted to file a desegregation plan based on the theory

that segregation in certain schools was the result of residential

housing patterns, rather than of any official or intentional

action of the school board. The defendants argued that the court

should reopen the proceedings to consider, for purposes of

tailoring remedies, the impact of demographic conditions on

particular schools. The district court refused to accept this

plan and its supporting evidence, and the Court of Appeals for

the First Circuit affirmed, on grounds that this "evidence was

irrelevant at the remedy stage of the case and that the issue

raised by the offer had been litigated and finally decided in the

liability phase of these proceedings." Id. at 407. The First

Circuit ultimately affirmed the district court’s plan and

implementation order for the remedial stage ("Phase II") of the

litigation. Id. at 431.

Hart v. Community School Bd. of Brooklyn, 497 F.2d 1027 (2d

Cir. 1974) is another of several cases which raised the question

of whether a district court’s order, finding liability but only

ordering the submission of remedial plan, was appealable. See

also Tavlor v. Board of Ed. of New Rochelle, supra. The district

court in Hart (in an oral opinion) had found that the Coney

Island junior high school at issue was unconstitutionally

segregated. Without entering a final order or issuing an

9

injunction, the district court directed the school board and city

housing authority to submit desegregation plans within the next

year. Judge Weinstein later held hearings on the remedial plans

submitted, rejected them as inadequate, and postponed the date

for desegregation pending the formulation of a new plan to be

developed with the assistance of a special master. Hart, 383

F.Supp. 699 (E.D.N.Y. 1974)* The black and Hispanic plaintiffs

in the case here attempted to appeal from the court’s

postponement of the desegregation. The 2nd Circuit dismissed the

appeal, holding that as per Taylor v. Bd. of Ed. of New Rochelle,

Y

288 F.2d 600 (2nd Cir. 1961), a district court’s opinion that

ruled on the question of liability while reserving the issue of

remedy, was not to be considered a final order.

In Reed v. Rhodes, 422 F.Supp. 708 (N.D. Ohio 1976), black

parents and the NAACP brought suit against city and state

educational officials, alleging they had intentionally

perpetuated racial segregation of students in the Cleveland

public schools. While the district court made no mention of the

trial having been formally bifurcated, its lengthy opinion

4 Judge Friendly of the Second Circuit characterized the lower

court opinion as stating that "in accordance with the invariable practice,

local school authorities must be given an opportunity to prove an

acceptable plan for eliminating the illegal segregation at this

school.’" Id. at 1029 (emphasis added). After receiving the

recommendations of the school board and special master, the

district court ultimately ordered the school to implement a magnet

program that would attract majority students and, failing that, to

institute a program of busing. Hart, 383 F.2d 769 (E.D.N.Y. 1974).

: @

10

addressed only issues of liability. After finding that the

Cleveland Board of Education had intentionally maintained a

segregated school system, chief Judge Battisti appointed a

special master to assist the court and "legitimately affected

interest groups" in fashioning a remedy. Id. at 797. The court

ordered the city and state school boards to submit a proposed

plan for desegregation within 90 days. In Reed, the court also

took the step of certifying the action for an interlocutory

appeal, writing that "there [was] substantial ground for

difference of opinion" in the case. Id. The court here

suggested that, given this circumstance, the defendants” ability

to appeal the finding of liability before the conclusion of the

remedy stage "may materially advance the ultimate termination of

the litigation." Id.

In fact, a protracted series of appeals followed the initial

opinion in Reed. Nevertheless, these appeals also proceeded in a

bifurcated manner, addressing issues of liability and remedy

Ld

severally. See Reed v. Rhodes, 559 F.2d 1220 (1977) (remanding

for reconsideration re: liability); 455 F.Supp. 546 (N.D. Ohio

1978) (liability); 607 F.2d 748) (remanding for reconsideration re:

state officials’ liability); cert. denied, 445 U.S. 935, 100

s.ct. 1329, 63 L.Ed. 2d 770 (1980); 500 F. Supp. 404 (N.D. Ohio

1980) (liability); 662 F.2d 1219 (1981) (affirming finding of

liability). only after issuing its second opinion regarding

liability (on remand by the 6th circuit for reconsideration in

light of several intervening Supreme Court decisions), did the

11

district court two years later enter a remedial order. See Reed

v. Rhodes, 455 F.Supp. 569 (N.D. Ohio 1978); 581 F.2d 570

(1978) (modifying a subsequent, unpublished remedial order by

district court); 500 F.Supp. 363 (N.D. Ohio 1981) (remedy) .

This practice of bifurcated proceedings appears to have

continued into the "modern" era of desegregation litigation.

Since the Court’s ruling in Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 97

S.Ct. 2749, 53 L.Ed.2d 745 (1977), schools desegregation

litigation has increasingly focused on the scope of relief and

the legality of plans for its financing. The procedural history

of these cases suggests that the complexity of the issues

involved -- for example, the creation of magnet schools,

compensatory programs and cost sharing arrangements between state

and local boards -- have made separate hearings on remedy

something of a necessity. In Milliken, for example, the federal

district court in Detroit conducted extensive hearings in regard

to remedy before ordering that compensatory programs in reading,

teacher training and counseling be instituted at state expense.

See Milliken, 433 U.S. at 267. It was this remedial order that

became the focus of appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court in Milliken

1, 418 U.S. 717, 94 8.Ct. 3112, 41 L.Bd.24 (1974) and Milliken

IX, 433 U.S. 267, (1977). In Jenkins v. Missouri, a relatively

—

recent desegregation case from Kansas City, the district court

held the State of Missouri and the Kansas City school board

liable for unconstitutional acts of segregation and ordered the

defendants to submit a plan for achieving a unitary school

| J

12

system. Jenkins, 593 F. Supp 1485, 1506 (W.D.Mo. 1984). After

separate hearing on remedy, the court held that need for a

unitary system justified a broad program of remedies to attract

and maintain nonminority enrollment, as well as an income tax

surcharge necessary to finance it. Jenkins, 639 F.Supp. 19

(W.D.Mo. 1985), aff’d 855 F.2d 1295 (38th Cir. 1988). .The court

later held additional hearings and issued separate orders on

other aspects of the remedial plan, including the school

district’s long-range program for capital improvements. See

Jenkins, 672 F.Supp. 400 (W.D.Mo. 1987). Finally, in a recent

case from the Second Circuit, the district court found City of

Yonkers’ officials and school board members liable for

intentional segregation in the city’s subsidized housing and

public schools. Yonkers v. Bd. of Education, 624 F.Supp. 1276

(S.D.N.Y. 1985). After receiving proposals from the parties and

conducting an evidentiary hearing, the court issued a remedy

order, reported at 635 F.Supp. 1538 and 1577 (1986). The court

of appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the finding of

liability and upheld the district court’s order that magnet

schools be implemented forthwith. Yonkers, 837 F.2d 1181 (2nd

cir. 1987), cert. denied, 486 U.S. 1055, 108 S.Ct. 2821, 100

L.Ed.2d 922 (1988).

TEC

MEMORANDUM

TO: Ron L. Ellis

FROM: Tanya E. Coke

RE: Bifurcation of school desegregation cases in the

federal courts

DATE: July 15, 1992

A review of opinions in several major school

desegregation cases suggests that bifurcating trials into a

liability and a remedy phase is a common, if not ordinary, method

of proceeding within the federal courts. I found no opinions

that explicitly addressed the propriety of bifurcation in the

context of a desegregation case, or that suggested that counsel

had formally moved to bifurcate the proceedings. Nevertheless,

in all of the opinions included herein, the district court

restricted its initial ruling to the issue of the defendant

school boards’ liability and ordered further proceedings on the

question of remedies.

In Taylor v. Board of Education, 191 F.Supp. 181

(S.D.N.Y. 1961), a suit brought by black parents against the New

Rochelle Board of Education, the district court held that the

defendants had intentionally maintained a segregated school

system in violation of Constitution and the dictates of Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 98 L.Ed.2d 873 (1954). While

the opinion is unclear as to whether the court actually barred

testimony as to remedy during the course of the trial, in

concluding his order Judge Kaufman wrote that it was "unnecessary

2

at this time to determine the extent to which each of the items

of the relief requested by plaintiffs will be afforded." Id. at

198. Instead, the court stated that it would defer consideration

of remedies until the school board had presented a plan for

desegregation, "said desegregation to begin no later than the

start of the [following] school year." Id. When school

officials later tried to appeal the order and extend the date set

for filing a desegregation plan, the Second Circuit dismissed the

action for want of jurisdiction on the basis that the district

court’s order was not yet final. Taylor v. Board of Education,

288 F.2d 600, 602 (2d Cir. 1961). The court held that when a

district court has simply found segregation by a school board to

be unconstitutional and has directed the board promptly to submit

a plan for remedying it, without any further "injunction," the

decision is not complete, and therefore not appealable. Id. at

602.

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Fd, 402 U.S. 1, 28 L.E4d.2d 554, 9) S.Ct. 1267

(1971), that a school board has broad discretion to formulate

educational policy, including plans to remedy racial segregation

within their school systems. The court in Swann wrote that

"absent a finding of a constitutional violation," such remedy

formulation "would not be within the authority of a federal

court." Swann, 402 U.S. at 16. Only where a school system has

defaulted on their obligation to proffer an acceptable plan for

desegregation, the court held, would the courts have the power to

3

fashion a remedy to assure a unitary school system. Id. This

language in Swann appears to endorse, if not mandate, a two stage

proceeding in which school authorities, once held liable under

Brown, are to be afforded the opportunity to formulate and

present a plan before the district court orders remedial action.

Since Swann, the district courts have continued to hear

cases in more or less informally bifurcated proceedings. In

United States v. Board of School Commissioners of Indianapolis,

332 F.Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971), aff’qd, 474 F.24 81 (7th Cir.

1973), cert. denied, 413 U.S. 920 (1973), the district court

principally addressed itself to two issues relating to liability:

whether the school district had deliberately pursued a policy of

segregating black students from white students as of the date of

the Brown I decision; and if so, whether the Board had since

changed its policy to eliminate such desegregation. In its

opinion finding the school board in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, the district court did order the board to adopt a

number of specific remedies immediately. These included the

reassignment of faculty, the relocation of a black high school,

and the implementation of a voluntary transfer policy that would

enhance desegregation. Id. at 678, 680. However, the court

stated that it also "[r]ecogniz[ed] that the orders thus far made

will not result in significant desegregation of majority black

schools immediately, unless the voluntary transfer . . . policies

are unusually successful," and therefore ordered defendants to

file comprehensive plans for racial desegregation with the court

A

before the start of the next school term. Id. at 681. The court

announced that it would hear and decide the question of further

remedies separately in a later proceeding. Id. In an opinion

issued four years later, the district court ordered the busing of

black students to outlying districts. U.S. v. Bd. of Sch.

Commissioners of Indianapolis, 419 F.Supp. 180 (1975). This and

subsequent orders on the issue of appropriate remedies were also

separately appealed. See U.S. v. Bd. of Sch. Commissioners, 541

F.2d 1211 (1976), vacated and remanded, 429 U.S. 1068, 97 S.Ct.

802, 650 L.Ed.2d 786 (1977).

The litigation around the desegregation of Boston’s public

schools in the mid-1970’s explicitly followed dual lines of

inquiry. In its initial order, the district court described the

15-day trial in Morgan v. Hennigan, 379 F.Supp. 410 (D.Mass.

1974) as one that "concerned only the liability issues of the

case, as contrasted with issues relating to the possible remedy."

Id. at 416. Judge Garrity wrote that "[t]he court’s primary task

is to determine whether the defendants have intentionally and

purposefully caused or maintained racial segregation in

meaningful or significant segments of the Boston public school

system in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment." Id. at 425.

! The U.S. Supreme Court remanded the case for reconsi-

deration of mixed questions of liability and remedy in what became

an interdistrict case (i.e., whether the district court had

jurisdiction to compel desegregation remedies affecting outlying

suburban corporations). See School Bd. of Indianapolis, 573 F.2d

400 (7th cir. 1978); 456 F.Supp. 183 (S.D. Ind. 1978); 506 F.Supp.

657 (S.D. Ind. 1979) (remedy only).

5

The court went on to examine for evidence of intentional

discrimination the school board’s policies toward districting,

student transfers, the assignment and promotion of faculty and

staff, utilization of facilities, and admission to its vocational

and college preparatory campuses. After finding that the

defendants had purposefully acted with discriminatory intent to

segregate, Judge Garrity declared that "the defendants are under

an ’affirmative obligation’ to reverse the consequences of their

unconstitutional conduct." Id. at 482. The court broadly

outlined several "remedial guidelines" for fulfilling this

obligation, but scheduled for the following week a separate

hearing to consider the details of a state plan for desegregation

already then under proposal.? Id. at 483. Judge Garrity also

ordered defendants to "begin forthwith the formulation and

implementation of plans which shall eliminate every form of

racial segregation in the public schools of Boston . . .

at 484.

The appeal to the First Circuit was similarly limited to the

district court’s findings on liability because (in the words of

the court of appeals) the district court, "[h]aving found such

deliberate design [to segregate], left the question of remedy to

2 These remedial guidelines were limited to broad statements

to the effect, for example, that the primary responsibility for

desegregation lay with the school committee; that school

authorities have the affirmative duty to take whatever steps are

necessary (including busing, redistricting, and involuntary school

and faculty assignments) to achieve a unitary system; and that the

time allowed for compliance would be only that reasonably necessary

to design and implement a remedial plan. Id. at 482.

6

a future time." Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509 F.2d 580, 583 (1st Cir.

1974). In a separate opinions issued some two years later, the

district court addressed the remedy phase of the Boston school

case. Morgan v. Kerrigan, 401 F.Supp. 216 (D.Mass. 1975). At

issue on appeal to the First Circuit in Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530

F.2d 401 (1st Cir. 1976) was whether the defendants could

present, "for purposes of tailoring remedies," evidence of

residential segregation during the remedy phase of the case, once

the liability phase had been concluded. Id. at 407. The court

of appeals described the history of the bifurcated proceedings in

the case as follows:

"The liability phase came to an end in 1974 with a

district court finding of substantial segregation in

the entire school system intentionally brought about

and maintained by official action over the years.

Morgan v. Hennigan, 379 F.Supp. 410 (D.Mass. 1974). We

affirmed, Morgan v. Kerrigan, 509 F.2d 580 (1st Cir.

1974), and the Supreme Court denied certiorari, 421

U.S. 963, 95 S.Ct. 1950, 44 L.Ed.2d 449 (1975). While

the liability issues were being considered on appeal,

the district court, after its decision on June 21,

1974, began its exploration of appropriate remedies.

The period from June, 1974, to May, 1975, was occupied

with the addition of parties to the litigation,

hearings as to the nature, scope and objectives of a

plan, submission and criticism of various plans,

consideration of all proposals and preparation of a

plan by a panel of masters, and, finally, the issuance

of a revised plan by the district court on May 10,

1975, followed by a Memorandum Decision and Remedial

Order.

Morgan, 530 F.2d at 405-406. One of the defendant organizations

had attempted to file a desegregation plan based on the theory

that segregation in certain schools was the result of residential

housing patterns, rather than of any official or intentional

action of the school board. The defendants argued that the court

7

should reopen the proceedings to consider, for purposes of

tailoring remedies, the impact of demographic conditions on

particular schools. The district court refused to accept this

plan and its supporting evidence, and the Court of Appeals for

the First Circuit affirmed, on grounds that this "evidence was

irrelevant at the remedy stage of the case and that the issue

raised by the offer had been litigated and finally decided in the

liability phase of these proceedings." Id. at 407. The First

Circuit ultimately affirmed the district court’s plan and

implementation order for the remedial stage ("Phase II") of the

litigation. Id. at 431.

Hart v. Community School Bd. of Brooklyn, 497 F.2d 1027 (2d

Cir. 1974) is another of several cases which raised the question

of whether a district court’s order, finding liability but only

ordering the submission of remedial plan, was appealable. See

also Taylor v. Board of Ed. of New Rochelle, supra. The district

court in Hart (in an oral opinion) had found that the Coney

Island junior high school at issue was unconstitutionally

segregated. Without entering a final order or issuing an

injunction, the district court directed the school board and city

housing authority to submit desegregation plans within the next

year. Judge Weinstein later held hearings on the remedial plans

submitted, rejected them as inadequate, and postponed the date

for desegregation pending the formulation of a new plan to be

developed with the assistance of a special master. Hart, 383

8

F.Supp. 699 (E.D.N.Y. 1974)%® The black and Hispanic plaintiffs

in the case here attempted to appeal from the court’s

postponement of the desegregation. The 2nd Circuit dismissed the

appeal, holding that as per Taylor v. Bd. of Ed. of New Rochelle,

288 F.2d 600 (2nd Cir. 1961), a district court’s opinion that

ruled on the question of liability while reserving the issue of

remedy, was not to be considered a final order.

In Reed v. Rhodes, 422 F.Supp. 708 (N.D. Ohio 1976), black

parents and the NAACP brought suit against city and state

educational officials, alleging they had intentionally

perpetuated racial segregation of students in the Cleveland

public schools. While the district court made no mention of the

trial having been formally bifurcated, its lengthy opinion

addressed only issues of liability. After finding that the

Cleveland Board of Education had intentionally maintained a

segregated school system, Chief Judge Battisti appointed a

special master to assist the court and "legitimately affected

interest groups" in fashioning a remedy. Id. at 797. The court

ordered the city and state school boards to submit a proposed

3 Judge Friendly of the Second Circuit characterized the lower

court opinion as stating that "in accordance with the invariable practice,

local school authorities must be given an opportunity to prove an

acceptable plan for eliminating the illegal segregation at this

school.’" Id. at 1029 (emphasis added). After receiving the

recommendations of the school board and special master, the

district court ultimately ordered the school to implement a magnet

program that would attract majority students and, failing that, to

institute a program of busing. Hart, 383 F.2d 769 (E.D.N.Y. 1974).

9

plan for desegregation within 90 days. In Reed, the court also

took the step of certifying the action for an interlocutory

appeal, writing that "there [was] substantial ground for

difference of opinion" in the case. Id. The court here

suggested that, given this circumstance, the defendants’ ability

to appeal the finding of liability before the conclusion of the

remedy stage "may materially advance the ultimate termination of

the litigation." Id.

In fact, a protracted series of appeals followed the initial

opinion in Reed. Nevertheless, these appeals also proceeded in a

bifurcated manner, addressing issues of liability and remedy

severally. See Reed v. Rhodes, 559 F.2d 1220 (1977) (remanding

for reconsideration re: liability); 455 F.Supp. 546 (N.D. Ohio

1978) (liability); 607 F.2d 748) (remanding for reconsideration re:

state officials’ liability); cert. denied, 445 U.S. 935, 100

S.Ct. 1329, 63 L.Ed. 2d 770 (1980); 500 F. Supp. 404 (N.D. Ohio

1980) (liability); 662 F.2d 1219 (1981) (affirming finding of

liability). Only after issuing its second opinion regarding

liability (on remand by the 6th circuit for reconsideration in

light of several intervening Supreme Court decisions), did the

district court two years later enter a remedial order. See Reed

Vv. Rhodes, 455 F.Supp. 569 (N.D. Ohio 1978): 581 F.24 570

(1978) (modifying a subsequent, unpublished remedial order by

district court); 500 F.Supp. 363 (N.D. Ohio 1981) (remedy).

TEC