Lawler v. Alexander Record Excerpts

Public Court Documents

December 20, 1977 - October 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lawler v. Alexander Record Excerpts, 1977. 4ac7f004-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ad693e19-e393-4f09-adaa-9fe20fdef250/lawler-v-alexander-record-excerpts. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

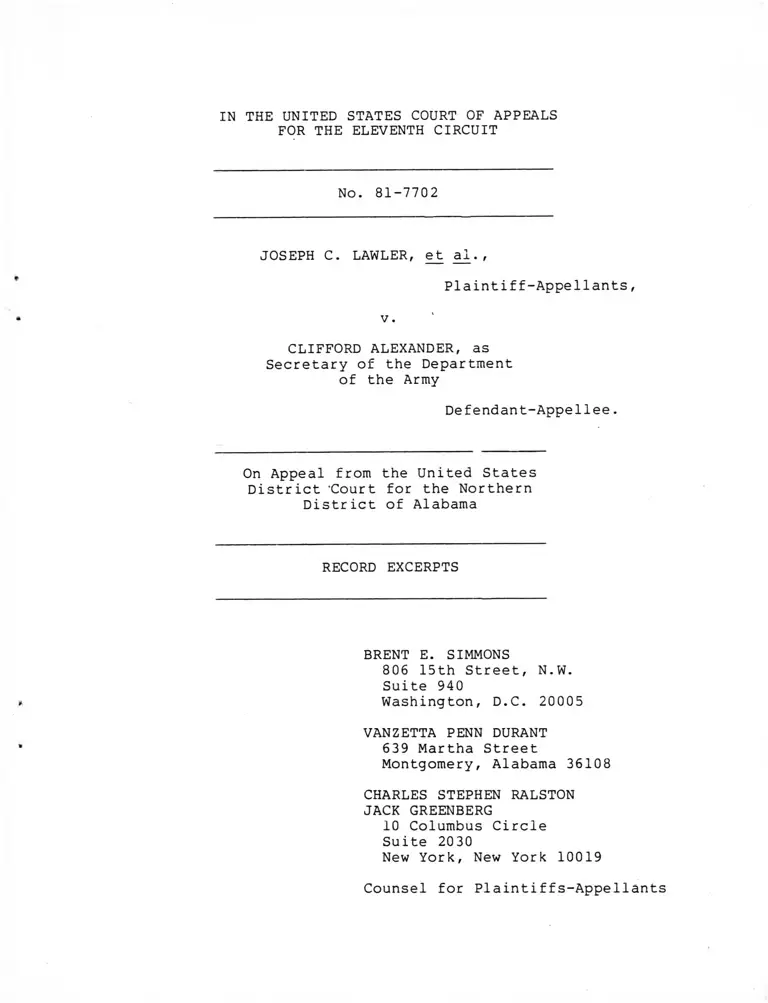

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 81-7702

JOSEPH C. LAWLER, et al.,

Plaintiff-Appellants,

v .

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER, as

Secretary of the Department

of the Army

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States

District 'Court for the Northern

District of Alabama

RECORD EXCERPTS

BRENT E. SIMMONS

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

VANZETTA PENN DURANT

639 Martha Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36108

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

JACK GREENBERG

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Docket Sheet ............................................. 2

Complaint ................................................ g

Answer .................................................... 2 3

Order Recertifying The Class ................. 1 6

Judgmen ..........*...................................... 17

Transcript of Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law .................................... 1 3

Order Denying Plaintiffs' Motion To

Amend Judgment and/or Findings ........................ 64

Memorandum of Opinion ................................... 65

a

i

CA77 R47 -E -

PROCEEDINGS

1Dec. 20i

211

1978

Jan 10

5?

24

3Feb 22

Mar 14

Apr 26

26

SS

26

Jun 6

7

m

Jul 11 &

13 %

Aug. 8 m

11 w

Sep. 6 [[si

27

Dec. 5

n a

n Ssi

15as

19

**

&

21

**Dec 20

Complaint filed, a d d /~S

SisnBons/complslnC leaned. Del. CO USM - add

Sumons/acnplaint returned, executed cn 12-22-77 on 0 S Atty; on 12/27/77 an

Atty Gen, Wash, D. C. and cn 12/30/77 cn Sec, U S Army, Wash, D.C. by

certified nail & filed lpc »,

Interrogatories and requests of deft for production of documents by plffs, filed - c

ANSWER of deft to the ocnplaint, filed - cs skh^^aZsjCd^-y

Answers of plffs to interrogatories, filed - cs -32.

Notice that deft will take the deposition of Timothy Goggins cn May 9,1978 in

Nashville, Tennessee, filed cs skh (notice to deponent attached)

Notice that deft will take the deposition of Joseph C. Iawler cn May 11, 1978

in Fort M cC le lla n , Alabama, with notice to deponent attached, filed - cs skh

Notice that deft will take the depositicn of Charles L. Bryant cn May 11, 1978

at Fort McClellan, Alabama, with notice to deponent attached, filed - cs skh

Interrogatories (first) of plffs propounded to deft, filed - cs skhpVp.23 . 6

Deposition of Charles L. Bryant taken on behalf of defendant, filed-snh

Objection of deft to interrogatories, filed - cs skhi2Z^?‘̂ / 0 C

Motion of plffs to ocnpel answers to interrogator!^, filed - cs skh

- 8/11/78 - M X T (Pointer) cm skh3&J/J 5 ! S - l

Motion of defendant, Clifford Alexander, to dismiss the complaint filed-cs-snh

— SEE ORDER DATED 9/5/78 - < 7ORDER CN PRETRIAL HEARING - filed and entered (Pointer) cm skWZ^XJ.S r o

ORDER dated September 5, 1978 that motion of deft to dismiss the putative class

is denied; an evidentiary hearing shall be scheduled upon request of plffs

filed and entered (Pointer) ca-snh

Depositicn of Joseph C. Lawler taken on behalf of deft, filed skh

Deposition of Timothy Goggins taken on behalf of deft, filed, add rmctA&t -(A>

Response of deft to plffs' first interrogatories to deft, filed (with attachments) -

Secorri Response of deft to plffs’ first interrogatories to deft, filed (with

attachments) cs skh{j#d£J6 7-//<V . _

Nation of deft to diatiss plffs, Timothy Goggins and Charles L. 3ryant, filed - cs

skh $O0U> HS-/3 0

Motion of deft for protective order, filed - cs skh^Zfc^C/J/

ORDER dated December 20, 1978 that plffs' counsel, including regular employees

of such counsel and their disignee be permitted access to information and

documents thereunto appertaining insofar as they relate to the allegations of

racial discrimination allegedly practiced upon Black employees of Ft. McClellan,

Alabama; further that experts retained by plaintiffs shall have access to all

records submitted by Ft. McClellan to be kept confidential; further that experts

employed by attys for plffs have access to information and records shall follow

those rigid security safeguards which are applied to these records filed and

entered (Pointer)cm-snh >33. -133

Hearing, under Rule 23, for certification as a class action before the Hon. Sam C.

Pointer, Jr. (Tommy Dempsey, Repcr,)

Oral order granting in pert end denying In part deft'e motion to quaeh

Louie Turner's Subpoena, entered. SCP

Plffs' testimony. Interrogatories of plff end deft'e answers thereto offered

by plffs end received by the court. Plffe rest.

Deft's testimony. Deposlton of Joseph Lawler offered by deft end rec'd by the eoui

Deft. rest. Preliminary findings end conclusions dictated into the record.

Orel Order denying deft'e motion to dismiss ee to Lawler end granting as to Bryant

end Goggins, with leave to reconsider ss to Goggins, entered. SC?

Orel Order that parties submit briefs within 2 weeks, entered. Written decision to be encered. after brleta are received. SC?_.— ------------- -----------------------

2

c iv il . D O CKET CO N TIN U A TIO N SH EET

PLAINTIFF DEFENDANT

JCSEPH C. IAWLER, ET AL CLIETQFD ALEXANDER

OOCKET NO. 77-P-1647-'

PAGE___OF ____ TAG'S

D ATE

1881,

PROCEEDINGS

.Mar 3

3

4

4

4

11

11

u

16

24

24

25

26

26

27

30

Apr 2

6

Apr. 10

m

Notice that deft will take the depositions of Timothy Goggins, Jchnnie'B. Hills,

Ruby M. Hairston and Joseph C. Lawler on 3-17-81 at Ft. McClellan, AL, filed-cs

Notice that deft will take the depositions of Diane F. Ware, Gwendolyn Redd,

Jeanette Simnons and Iouie Turner, Jr., cn 3-18-81 at Ft. McClellan, AL, filed-c

Notice (amendment) that the defts will take the depositions of Betty J. Bailey

Ralph E. Driskell, Timothy Goggins, JOhnnie B. Hills on March 12, 1981 in -

Ft. McClellan, Alabama, filed-cs-snh

Notice (amendment) that the defts will take the depositions of Ruby M. Haris ton,

Clyde Woodward, Louie Turner, Jr., on March 13, 1981 in Ft. McClellan,

Alabama, filed-cs-snh

Notice (amendment) that taking of the deposition of Vanzetta Penn Durant schedu

far March 17, 1981 and March 18, 1981 is CANCELLED, filed-cs-snh

Notice (amendment) that the depositions scheduled fee March 12, and 13, 1981 in

this action cure candelled, filed-cs-snh

Notice that deft will take the depositions of Clyde Woodward and Louie Turner an

3-19-81 at Ft. McClellan, AL, filed-cs phm

Notice that deft will take the depositions of Betty J. Bailey, Ralph E. Driskell

Jbhnnie B. Hills and Ruby Hairston an 3-18-81 at Ft. McClellan, AL, filed-

cs phm

Response of defts to plffs second set of interrogatories and request fer

production, filed-cs-snh

Notice that the deft, USA, will take the depositions of Wayne Garrett, Jack Haa-

Willie J. McCluney, Josephine McKinney, Bobby L. Murphy, Dennis E. Ray, Elijal

Ray, Jt., Willie J. Ruffin on March 26, 1981 in Ft. McClellan, Alabama, filed

cs-srh

Notice that the deft, USA, will take the depositions of Cynthia Strickland, Jeai

P. Simons, Dennis Thorns, Curtis L. Hunt, Jt. on March 27, 1981 in Ft.

McClellan, Alabama, filed-cs-snh

Motion of plffs far an order compelling production by defendant and answers to

interrogatories, with exhibit attached, filed-cs-

03/26/81-GRANIED IN PART AS DESCRIBED IN INFORMAL CONFERENCE (POINTER); altered

Notice (amendment) that the deposition notices dated March 26, 1981 and March

27, 1981 are cancelled, filed - cs-snh

Notice that the deft, USA, will take the depositions of Charlotte Acklin, Joseph;

McKinney, Bobby L. Murphy, Jack Heath, Wayne Garrett, McCardis Barclay,

Jeanette P. Simons, and Clyde Willis on March 29, 1981 in Ft. McClellan,

Alabama, filed-cs-snh

Sumaries of witnesses testimony of plffs, filed-cs-siti.'l22Cp3/9S~‘J <y 7

Motion of defendant to dismiss the complaint with exhibit attached, filed-cs-snh

— 03/31/81-DENIED (POINTER); entered 04/01/81-am-snh^J^.^!</i’-«57

Notice that deft will take the deposition of Joe L. Willis on April 4, 1981,

in Birmingham, AL, filed-cs-lpc

Witness list (expert) of defenant, filed-cs-snh(p®^£-<H.3"<2.-^ % (w

Notice that deft will take the depositions of Dennis Theres and Willie Ruffin cm

April 16, 1981 in Ft. McClellan, Alabama, filed-cs-snh

4

: u iamt. 1/75)

C IV IL D O C K E T C O N T IN U A T IO N S H E E T

D E F E N D A N T I

d o c k e t n o 77-P-1647-i

P A G E ____O F ______ P A G E S

D A T E

'981

vpril 17

20

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

27

May 1

5

5

12

12

22

m 2

2

8

£ 2

P R O C E E D IN G S

Witness list of plffs aid exhibits f i l e d - c s - s n h ^ 1„

Witness list aid exhibit list of defendants, filed-cs-si*^£22s£^‘*’™ -i»/<3

Deposition of Lcuie Turner, Jr. taken on behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of McCordia Barclay, Jr. taken on behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Whyne M. Garrett taken on behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Jack Heath, Jt. taken on behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Bobby L. Murphy taken on behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Depositon of Josephine McKinney taken an behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Charlotte Acklin taken an behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Ralph E. Driskell taken on behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Ruby M. Hairston taken on behalf of the defeidants, filed-snh

Deposition of Clyde Woodard taken on behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Betty Jean Bailey taken an behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Willie J. Ruffin taken an behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Jeanette P. Simons taken on behalf of the defendants,.^?'le^snb,^

Motion of defendant, to dismiss or in the alternative to de^ ^ ^ ^ y ^ j l j ^ ^ s ^ n h r,

— 05-21-81 DENIED, BUT P U T DIRECTED TO F H E PROOF OF NOTIFICaTCN (POINTER) ; h

Response of defendant (supplmental) to plffs second set of interrccatari.es and

request far production, filed-cs-snty22£)2_.2f<2 -352.

Motion af plffs far an order to carpel production with exhibits attached, filed

C3‘snh

Request af deft fix production by plff, filed-cs-snhj&y g

Response of plffs to defendant’s motions to disniss filed-cs-snh^22^J’-?/-J«,J

Response of defts to the standard pre-trial crder with exhibit attached

cs-snh

filedp. .

dated April 13, ^

ORDER (PROTECTIVE) by consent of the parties/that the use of certain documents

belonging to the Inspector General of the Army is limited as set out in

this order; should any of the documents named herein be offered into

evidence, they will be kept unser seal, and returned to deft at the

conclusion of litigation, filed (POINTER); entered 05/05/81-an-snh 7 per

(order found in file attached to letter this date - %Ti\)f5lOfi^33£ -Sjc

Notice that the plffs will take the depositors of Ann Vaughn, David Parker,

Patricia Dunn, and Jfergaret Colley on May 20, 1981 in Ft. McClellan,

Alabama, filed-cs-snh

Notice that the plffs will take the depositions of William Ward, Patsy Smallwopd,

Sandra Carrozza, Denton Elliscn cn May 21, 1981 in Ft. McClellan,

Alabama, filed-cs-snh

Proof of notice to the lumbers of class in January 1980 with affidavit of 0.

Clmon and exhibits attached, filed-cs-snh^Z^Z-£i9 ~35l

Notice that defendants will take deposition of Miriam Ellerman an 6/16/81 in

Colorado Springs, CO, filed-cs-tyt

Notice that defendants will take deposition of Dennis Oxanas on 6/10/81 in

Bioningham, AL, filed-cs-tyt

Motion of plaintiffs far continuance of trial to 11/30/81, with affidavit of

Martin L. Madar attached, filed-cs-tyt (Del. SOP)

DENIED SCP June 11, 1981 an Ihj 02/^0 353, -3 5 3

W.

5

DC 111A

(«•». 1/75)

C IV IL D O C K E T C O N T IN U A T IO N S H E E T

P L A IN T IF F

JOSEPH C. LAWLER, ET AL

D E F E N D A N T

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER

D O C K E T N O . T7-P-1647

P A G E ____O F ______ P A G E S

-E

1 9°3T5

June 12

23

24

24

24

24

24

25

26

29

29

July 1

2

3

17

20

27

30

Aug. 10

10

BS

P R O C E E D IN G S

Motion of plaintiffs to reconsider denial of motion far continuance filed^s-rfd

(del sc2)fao£- 3 5 “7 -3 GO

- Ufcuni) 6/15/81 (Pointer): ENTERED 6/15/81 on-dvm

Deposition of Dennis R. Thcnes taken an behalf of the defendant, filed-snh

Deposition of Patsy W. aiallwood taken on behalf of the plaintiffs, filed-snh

Deposition of David M. Parker taken on behalf of the plaintiffs, filed-snh

Deposition of Sandra Carrozza taken on behalf of the plaintiffs, filed-snh

Deposition of Ann Vaughan taken on behalf of the plaintiffs, filed-snh

Deposition of Denton Ellison taken on behalf of the plaintiffs, filed-snh

Motion of deft. Secretary of the Army, for a grptectyfe order in limine filed-

cs-snh (del to SCP) 6/29/Sl^oref^isiD‘BUT RULING DEFERRED (POINTER:

Deposition of Joseph Matzura, taken on behalf of pltfs., on 5/21/81 in Anniston,

Ala. - filed Brerda Evans, reporter Ire

Request of defendant far production, filed-cs-snh

Cn trial before the Han. Sam C. Pointer, Jr. - oral motion of plfts to leave

evidence open at aonclusion of trial for the purpose of an analysis by

expert of certain tapes, entered - denied - testimony of plfts - deposition

of Miriam Ellerman taken by defts, filed - deposition of Margaret Colley taker

defts, filed - case aontinued until July 1, 1981 at 9:00 a.m. - daily adj.

Reporter: Wendell Parks - Ipc (Anniston, AL)

Trial resumed - testimony of plfts resumed - testimony of deft as to witness

James Williamson taken out of turn - daily adj.

Trial resumed - testimony of plft resumed - daily adj.

Trial resuned - plfts rest - oral motion of deft for dismissal entered - overruled,

testimony of deft - daily adj.

Trial resumed - testimony of deft resuned - deposition of Miriam Ellerman offered

into evidence by deft - received - daily adj.

Trial resuied - testimony of deft resumed - deft rests - rebuttal testimony of

plfts - plfts rest - closing arguments by counsel - findings of facts &

conclusions of law dictated into the record by the Court entering judgment in

favor of the deft and against the plfts and plft class members and taxing

costs against the plfts - lpc Reporter: Wendell Parks

Clerk's Court Minutes dated JU-ly 7, 1981 that pursuant to the findings and

conclusions of law dictated into the record by the Court that judgment is

entered in favor of the defendant and against the plaintiffs' class metiers

and that costs are taxed against the plaintiffs, filed; entered 07/08/81-

cm-snh (Wendell Parks Court Reporter> ^ 2 ^ , 3 6 9

Motion of plffs to open and amend judgment and/or findings of fact with large

exhibits attached, f i l e d - c s - s n h '373

Bill of costs of defendant filed-cs-snh (del to G. Bell 7/27/81 far taxing)

Deposition of Donald R. EtaGee taken on behalf of the plaintiff filed-snh

Cost* taxed to plaintiffs in the sum of $600.99 - geb - as

Deposition of Ralph E. Driskell taken on behalf of the defendants, filed-snh

Deposition of Betty Jean Bailey taken on behalf of the defendants, filed- snh

6

: iiia

•v. vn)

7

ir

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

EASTERN DIVISION

filed in c tn rrs

NOfrrncRN district c; Alabama

DEC 2 01577

j a m e s £. • p r x

CIVIL ACTION NUMBER

A. Subject natter jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16, as amended 1972

(-Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act"). The Court has

jurisdiction over the subject matter pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

SS1331, 1343(4) and 1361.

B. This is an action, inter alia, for declaratory

and injunctive relief against certain policies and practices

of the United States Department of the Army, at its installation

at Fort McClellan, Alabama.

II.

A. Plaintiff, JOSEPH C. LAWLER, is a black male citi

zen of the United States and of the State of Alabama. He has

been employed at Fort McClellan since 1966; and is a current em

ployee of that installation. He holds a bachelor's degree from

Jackson State University-

B. Plaintiff, TIMOTHY GOGGINS, is a black male citi

zen of the United States and of the State of Alabama. He is a

graduate of Talladega College. He is a current employee at

Fort McClellan, serving as a Personnel Staffing and Classifies

tion Sepcialist.

JOSEPH C. LAWLER, TIMOTHY *

GOGGINS, and CHARLES L.

BRYANT, on behalf of themselves *

and others similarly situated, **

PLAINTIFFS, *

*

*

V S . *

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER, as head of *

the United States Department of

the Army, V*,* -

DEFENDANT. *

I.

8

2

C. Plaintiff, CHARLES L. BRYANT, is a current employee

at Fort McClellan, having worked there continuously since 1966.

He has completed two years of college; and he is now classified

at Fort McClellan as a truck driver and painter.

D. Defendant, CLIFFORD ALEXANDER, is the Secretary

of the United States Army, which operates a Military Police

School and a Training Center at Fort McClellan, Alabama. De

fendant Alexander is therefore the head of the agency charged

with discrimination, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. S2000e-16(a) and (c).

III.

A. Pursuant to Rule 23(a) and (b)(2), plaintiffs

bring this action on behalf of themselves and all other simi

larly situated black employees of Fort McClellan. The class

represented by plaintiffs is so numerous that joinder of all

of its members is impracticable. There are questions of law

and fact common to the class; and the individual claims of the

plaintiffs are typical of those of the class. Through their

counsel, plaintiffs will fairly and adequately represent the

class.

B. The defendant, through his agency, has acted or

refused to act on grounds generally applicable to the class,

thereby making appropriate final injunctive relief or correspond

ing declaratory relief with respect to the class as a whole.

C. The class represented by plaintiffs consists of

all black applicants for employment, and all black employees

of Fort McClellan who have been denied promotions or otherwise

discriminated against because of their race by the policies

and practices set forth below.

rv.

A. Plaintiffs allege that the hiring policies and

practices of Fort McClellan are racially discriminatory; and

that white applicants for employment are pre-selected over equally

or better qualified black applicants.

9

3

B. Plaintiffs aver that they and other similarly

situated black employees have been and continue to be denied

promotions because of their race or color. The racially dis

criminatory promotion policies and practices include but are

not limited to the following:

(1) . policy and practice of racially discrimi

natory evaluations by a basically all-white supervisory staff;

(2) . policy of improper classification of certain

jobs performed by black employees;

(3) . policy of improperly extending the areas of

consideration where incumbent black employees would otherwise

be entitled to fill vacant positions;

(4) . policy and practice of abolition or with

drawal of posted jobs where blacks have been certified as

"best qualified" for the vacancy;

(5) . policy and practice of identifying the race

of black candidates whose names are contained on the referral

list, so that they will not be considered to fill the vacancy;

(6) . policy and practice of downgrading the wage

scale of positions which are applied for and/or accepted by

blacks; and

(7) . policy of pre-selection of white employees

for certain vacancies by an all white supervisory or selection

staff.

C. Plaintiffs allege that the officials of Fort

McClellan often harrass, intimidate, and disrespect black em

ployees because of their race or color.

D. Plaintiffs aver that they have personally suffered

discrimination attributable to the above policies and practices,

and because of their race' or color.

10

4

A. On December 3, 1976 plaintiff Joseph Lawler noti

fied the Equal Employment Officer ("EEO") counselor at Fort

McClellan of his complaint that he had been discriminatorily de

nied a promotion. On January 1, 1977 the said plaintiff filed

a formal complaint of discrimination alleging a discriminatory

denial of promotions and racial disrespect. The complaint was

investigated by the United States Army Civilian Appellate Review

Office; and on November 22, 1977 plaintiff Lawler received his

Notice of Final Agency Decision and of his right to institute

this action within thirty days thereafter.

B. Plaintiff Timothy Goggins filed a complaint of

discrimination with the EEO counselor on March 30, 1977, com

plaining of discrimination in placement and hiring practices at

Fort McClellan. More than 180 days have elapsed since the filing

of the complaint, and there has been no final action by Fort

McClellan on this complaint.

WHEREFORE, the premises considered, plaintiffs respect

fully pray that this Court will grant the following relief:

A. A judgment declaring unlawful the defendant's

hiring and promotion policies;

B. An injunction requiring the defendant to cease and

desist its policy of harrassment, intimidation, and disrespect

towards black employees;

C. An injunction requiring the defendant to hire and

promote the plaintiff class members to the positions which they

are entitled, with the appropriate backpay;

D. An injunction requiring the defendant to abolish

those features of its promotion policies which discriminate

against its black employees;

F. A judgment granting plaintiffs their costs herein,

including a reasonable attorney's fee; and

G. Such other, further, or different relief as to

which plaintiffs may in equity and good conscience be entitled.

V.

11

5

Respectfully submitted,

ADAMS, BAKER & CLEMON

Suite 1600 - 2121 3uilding

2121 Eighth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

12

■o

)I

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

EASTERN DIVISION

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

) Civil Accion No. 77-P-1647-E

)

)

)

)

)

)

ANSWER

Comes now che above named defendant by and through

the United States Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama

and for answer to the complaint filed herein states as follows.

I. Paragraph I of complaint contains the plaintiff's

jurisdictional allegations to which no answer is required, but

the extent an answer is deemed necessary, they are denied.

II. A. Paragraph II.A. of the complaint is admitted

except the defendant denies that the plaintiff's degree is

from Jackson State University.

B. Paragraph II.B. of the complaint is admitted

except the defendant denies that the plaintiff is serving as

a Personnel Staffing and Classification Specialist.

C. Paragraph II.C. of the complaint is admitted

except defendant denies that plaintiff has completed two years

of college and that the plaintiff is classified as a truck

driver and painter. Defendant specifically infers that

Charles L. Bryant is employed a3 a WG-7 Motor Vehicle Operator.

JOSEPH C. LAWLER, TIMOTHY

GOGGINS and CHARLES L.

BRYANT, on behalf of

of themselves and others

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs

v s .

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER] As head

of the UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY,

Defendant

13

D. Paragraph II.D of Che complaint is admitted.

III. Paragraph III is denied.

IV. Paragraph IV is denied.

V. A. Paragraph V.A. of the complaint is admitted.

B. Paragraph V.B. of Che complaint is denied.

C. Defendant specifically denies Chat the plaintiffs

are entitled to any relief whatsoever.

FIRST DEFENSE

As to all plaintiffs individually named and the

alleged class, that part of the complaint which alleges

harassment, intimidation, and disrespect fails to state a

claim upon which relief can be granted.

SECOND DEFENSE

As to individually named plaintiffs Timothy Goggins

and Charles L. Bryant, and the alleged class, administrative

remedies have not been exhausted.

THIRD DEFENSE

As to Che individually named plaintiffs Timothy

Goggins and Charles L. Bryant, and the alleged class this

case should be returned to the administrative agency for its

review under the doctrine of primary jurisdiction.

FOURTH DEFENSE

As to the individually named plaintiff’s Timothy Goggins

and Charles L. Bryant, and the alleged class the complaint

- 2-

' > ' 'I

14

t »

fails Co stace a claim upon which relief may be granted

WHEREFORE, the defendant having answered the complaint,

prays for judgment together with cost and for such other

different relief as may be just.

J. R. BROOKS

United Staces Attorney^

OHNNY WARDWICK

ant United States Attorney

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing has

been served upon counsel for all parties to the proceeding

by mailing the same by first class United States mail properly

addressed and postage prepaid on this the j *L day of

February, 1978.

Johnny Harcjyh.cK

Assistant United States Attorney

-3-

15

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

Eastern Division

w a r ; 6 1 9 7 5 -

JOSEPH C. LAWLER, et al

Plaintiffs

NO. CA 7T-?-l6k7-Z

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER

Defendant.

O R D E R

This cause arises on the oral motion of the defendant, made

at the time of this court's preliminary ruling on the issue of class c

certification on December 20, 1978, to decertify the class recognized

by the court. This oral motion has been reasserted in the form of

the defendant's memorandum in support of class decertification re

ceived on January *, 1979- In addition to requesting that this

court decertify the previously-certified class, the defendant, by

this memorandum, has alternatively requested a redefinition of that

Upon consideration, the court has concluded that the grounds

asserted by the defendant in support of its motion for decertifica

tion are without merit. Primarily, these grounds relate tojthe

absence of common questions of law and fact, the impropriety of

this action for Injunctive relief, and the inadequacy of plaintiff

Lawler as a class representative. It is the conclusion of this

court that certification of the class here involved is appropriate.

Alternatively, the defendant has requested that the court redefine

the certified class in certain limited respects. It appears that

there is merit to thi3 request, since some of the language used by

the court in its preliminary ruling on December 20, 1978, is

apparently susceptible to differing interpretations depending on

whether understood in its ordinary, everyday sense, or in the

civilian personnel sense which is somewhat unique to the defendant.

For this reason, the class previously certified by this court is

hereby redefined to include all black employees at Fort McClellan,

Alabama, on or after November 3, 1976, who were or are paid from

appropriated fund3 , and who have been denied a promotion. Pro

motion, as here used, shall be applicable to those employees who

have failed to be selected for a position for which they were referred,

those employees who have been misassigned by their supervisor with the

result that they are performing work outside their correct Job

classification and description, and those employees who have been

unsuccessful in their efforts to obtain a requested reclassification

of their Jobs. So_ ORDERED.

This the ~~ day of Marc-

class.

I

16

; v

X

<

JUDGMENT ON DECISION BY TOE COURT

r IBistrirt. Cmtrf

F O R T H E

NORM DISTRICT OF ALABAf-lA

C iv il Ac t io n f i l e N o. 77- P -1647-E

Plaintiffs, JU D G M EN T

JOSEPH C. LAWLER, TIMOTHY GOGGINS,

and CHARLES L. BRYANT, on behalf of

themselves and others similarly

situated,

VS

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER, as head of the

United States Department of the Army,

Defendant.

CLERK'S COURT MINUTES

This action cate on for trial an June 29, 1981, before the Court,

Honorable Sam C. Pointer, Jr. , United States District Judge , presiding,

and the issues having been duly tried.

It is ORDERED and ADJUDGED that.pursuant to the findings of fact and

conclusions of law dictated into the record by the Coujrt, judgment is entered in

favor of the defendant and against the plaintiffs and the plaintiffs' class matters;

and that costs are taxed against the plaintiffs.

F I L E D

JUL3-19GI

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

JAMES E. VANDEGRIFT. CLERK

DATED: July 7, 1981

Anniston , Alabaim

Court Reporter: Wendell Paries

JAMES E. VANDEGRIFT, CLERK

BY:

DEPUTY CLERK

ENTE! !E

j'UL 8 iyai

17

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

DISTRICT OF ALABAMA,

JOSEPH C. LAWLER,

TIMOTHY GOGGINS, and

CHARLES L. BRYANT, on

behalf of themselves and

others similarly situated,

PLAINTIFFS

V S .

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER, as

head of the United States

Department of the Army,

DEFENDANT

COURT FOR THE NORTHERN

EASTERN DIVISION

)

)

)

)

) CIVIL ACTION NO.

)

) 77-P-1647-E

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

C A P T I O N

THE ABOVE ENTITLED CAUSE came on to be heard

before the Honorable Sam C. Pointer, Jr., United

States District Judge, at the United States District

Courthouse, Anniston, Alabama, on the 29th day of

June, 1931, commencing at 9:00 A.M., at which time

the following proceedings, among others, were had

and done:

18

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

1

Mr. Brent E. Simmons, /attorney at Law,

306 15th Street, N. w., Suite 940, Washington, D.C.

20005, appearing for the Plaintiffs.

Ms. Vanzetta Durant, Attorney at Law,

639 Martha Street, Montgomery, Alabama 36108, also

appearing for the Plaintiffs.

Mr. Richard W. Wright, Office of the

Judge Advocate General, Department of the Army,

Pentagon, Washington, D.C. 20310, appearing for the

Defendant.

Ms. Ann Robertson, Assistant United States

Attorney, United States District Courthouse,

Birmingham, Alabama 35203, also appearing for the

Defendant.

19

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

3.

FINDINGS OF FACT-CONCLUSIONS OF LAV?

THE COURT: The Court will now dictate into

the record findings of fact and conclusions of law.

The issues are as developed in the pretrial order

in this case and as indicated in the definition of

the class as indicated in prior orders of the Court.

The evidence consists of the testimony of a

number of witnesses, one of whom by deposition, and

the reception of a series of documentary items, some

of which constituting computer exhibits and other

summations from other materials.

Additionally, the Court has considered certain

matters presented not by way of formal evidence but

by way of summations of evidence in written form

presented through plaintiff’s counsel.

It should be noted that some of the exhibits

were received for limited purposes, such as for

impeachment purposes, and I have read those tabs out

of tha investigation file that were introduced right

at the close of the evidence.

This case involves a claim brought on behalf

of black employees at Fort McClellan in appropriated

funds positions with respect to any claims they may

have that during the period November 3, 1976, through

October 1, 1930, they were discriminated against by

20

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

being denied promotions. For this purpose promotions

includes situations where someone was referred for

potential selection but not selected, as well as

situations in which perhaps duties were being performed

by a person at the wrong grade level, so that *

effectively the person was being denied the promotion

or the pay for the position that he was in fact

performing.

It was also indicated during the pleadings

stage and class determination stage that the case would

involve claims of denials of requested reclassifica

tions of positions. For the most part, however, that

aspect of the case really has not been developed, so

that the primary consideration and attention of the

Court relates to the question of nisgrading of

positions and denials of promotion of those referred

by consideration.

Some question has been raised by brief and

at points during the presentation of evidence as to

whether denials of promotion that might arise through

some other means are properly before the Court. That

is, whether, for example, someone who was ruled

ineligible for consideration for a particular promotion

should have in this case a claim that that ruling of ... ...

ineligibility was a violation of Title VII. Those

_______________________________________________________________________________ A_

21

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

matters were not at the time the class was formed

thought by the Court to be appropriate for considera

tion in this case, given the nature of the claims

being made by the then class representatives, the

nature of the EEO complaint that had been filed by

Mr. Lawler, and the fact that many of these areas

would involve attacks upon criteria and standards

developed and presumably maintained on an Army-wide

basis or Government-wide basis, and that the plaintiffs

were really not preparing to challenge those in this

case.

In any event, the case came on to be preoared

and to be tried with respect to this more limited area

of denials of promotion, and for the period of time

that I have indicated.

The Court has, however, permitted evidence

dealing with other aspects of the entire promotional

system that was practiced and followed at Fort

McClellan, and has permitted evidence as to events

that occurred prior to November 3, 1976 and after

October 1, 1980 for their circumstantial value on

the issues which are before the Court.

in these findings concentrate primarily,

however, upon the matters that were involved between

November 3, 1976 and October 1, 1980. While mention

22

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

4

may be made of some events that occurred before or

after that period, I will not place too much attention

in these findings upon those, and I do note that by

and large the evidence before me indicates that the

events that occurred prior to this starting date, or

after the closing date, were not materially different

from the type of evidence that I found being presented

during this almost four year period of time.

Both plaintiffs and defendant have presented

evidence to me both of a statistical nature dealing

with certain generalizations about events, promotion

events, classification of positions, and about specific

incidents that have been referred to during the

presentation of individual claims by a score or so of

class members. I will first deal with some of the

statistical materials before proceeding with a

discussion of appropriate findings concerning individual

events.

Plaintiffs demonstrate that the number of

black persons employed at Fort McClellan in

appropriated funds positions is slightly less than

ten percent of the entire work force in such positions,

and that this figure is somewhat less than the

percentage of blacks in the localized labor market

in and around Anniston, a figure that is in the range

23

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

1

of fifteen to sixteen percent black.

Plaintiffs also have demonstrated through

Exhibits 1 and 2 that blacks are less well represented

at the higher grade levels in the several compensa

tion schedules than they are at the lower and middle

grade levels.

Plaintiffs have also demonstrated that the

average wage level for blacks is and has been less

than the average wage level for whites. All of these

natters are, of course, of significance and value in

support of plaintiffs' claims that there has been

discrimination in and about the promotion system at

Fort McClellan.

The parties have, however, gone much further

in detail in terns of what might generally be called

applicant flow data as it relates to promotions by

looking at the actual persons who applied for positions

announced, the evaluation and rating of those

individuals, the reference of those individuals for

consideration for selection, and selection itself.

Both plaintiffs and defendants have provided

the Court with studies relating to all or part of these

facets of the employment process and the promotion

process. The plaintiffs have provided a computerized

print-out which indicates in various categories of

24

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

information, including grade structures and levels,

type of promotion, type of outcome of a promotional

announcement, figures to indicate the number of

whites and blacks applying, who were rated, who were

found to be qualified at some level, who were found

to be either highly qualified, or what is most

important, for ultimate consideration best qualified,

and in part reflecting information concerning those

who were selected. This particular exhibit by the

plaintiffs is, as the plaintiffs acknowledge,

deficient in its column dealing with selection,

because apparently the failure of several of the

persons involved in actually ascertaining that informa

tion from Army records failing to provide information

in terms of who was selected and who was not selected.

The defense, however, did ask, and the Court

did receive that last column for consideration,

recognizing the omission and deficiency in its cover

age.

It may here, however, be noted that there is

no particular reason to believe that the materials

that ware encoded on that column would be materially

different as it relates to whites and blacks had all

five of the students filled in that information . ..

correctly instead of merely two of them. There is a

- _________________________________________________________________________ S_

25

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

greater room for error obviously when only two of

five were putting that information in, but there is

at least some indication, and indeed a comparison

with defendant’3 exhibits indicates this is correct,

for believing that the relative information concerning

whites and blacks selected is substantially accurate

in plaintiffs' exhibit as well as in the defendant's

exhibit.

By brief plaintiffs have suggested that the

information in their computer print-out, properly

analyzed, leads to certain conclusions, namely that

one could draw a reasonable inference from those

figures that blacks have been discriminated against

in various aspects of the promotional process.

More particularly the plaintiffs would assert that

blacks have been more adversely affected than whites

in certain promotions that, or, announcements that

were withdrawn, were abandoned or rewritten, and

that blacks tended to be at a higher rate than

whites found not to be in the best qualified group

of applicants, best qualified meaning those that

would ultimately be considered for the actual

promotion.

I want to make a few comments about certain

of the tables that were appended to the plaintiffs'

______________________________________________________________________________ 0_

26

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

---------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- J - O -

brief with respect to the use and analysis of that

print-out.

Table No. 3 of that brief does indicate that

ratings as categorized in that table were significantly

different from a statistical standpoint for blacks

i

and whites. What was not done, however, in Table 3,

and what must be also taken into account is that the

final selection of blacks did not result in any

disadvantage to blacks on a statistical basis.

Indeed, the contrary is true. The figures even from

the plaintiffs* exhibit reflect that even as relates

to those who were best qualified, the percentage of

blacks selected was approximately 9.47 percent. The

percentage of whites selected, 9.39 percent. That

would be by using the selection ratios from the

defendant's study, which were essentially complete.

If one uses the selection ratios that are

contained in Plaintiff's Exhibit 36, the computer

print-out itself, again blacks result in being

favored in their selection rate, and this goes back

to the various categories, both the number of appli

cants and the number rated.

The point has been made in Table 4 appended

to that brief that blacks have been more affected by

non-standard actions, matters in which something

27

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------b r

other than the normal promotion flow, such as by a

cancellation of some announcement or a rewriting of

some grade, and the like. According to the figures

contained in Table 4, those differences were thought

by plaintiffs’ expert to be statistically significant.

I note that an error apparently has been

made in this calculation in that the materials for

non-standard actions or outcomes do include certain

individuals who in fact were selected, so that not

everybody that is in that category failed to be

selected. According to the data submitted by

Plaintiff's Exhibit 36 there were seventeen individuals

affected in this non-standard outcome who in fact

were selected, and according to those tables, when

those individuals are eliminated and one looks at the

balance, namely the blacks who were involved in those

promotional matters, but who were not appointed, the

whites who were involved in those promotional

matters, but not appointed, it turns out that in

comparison with the number of original applicants,

only thirteen percent of the blacks were so affected

and eighty-five percent of the whites involved in

those same promotions were affected.

Likewise, if one looks at the best qualified

showing up in those non-standard outcomes and

28

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

12.

eliminates those who in fact were selected from that

consideration, it again turns out that the effect

of in effect cancellation of the announcement had a

higher adverse impact on whites than it did on blacks

— eighty-four percent, fifty-seven percent.

In Table No. 5 appended to the plaintiffs'

brief the argument is made through plaintiffs'

expert that even a .18 level of significance should

be considered appropriate. The Court rejects that

approach to statistical significance. It is perhaps

significant that plaintiffs' expert acknowledged

that no Court, and to his knowledge no other

statistician had yet agreed with that approach. The

Court does not disagree, however, with that same

expert's testimony in court to the effect that

materials and statistical data nay certainly be

considered by the Court, and properly so, even though

it is not statistically significant at the .05 level.

There is, however, a difference between allowing

something to be considered along with all other

evidence in the case than merely on the basis of

some statistical study at something like the .13

level, drawing from an an inferential leap that

something else exists. It is on that point that the

Court would disagree apparently with what plaintiffs'

29

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

------------------------------------------------------- in

expert was asserting.

I may have said Table 5, I meant to say

Table 6, where this .18 level was utilized.

As noted in Table 5, there was no significant

underrepresentation of blacks in the ratings given

with respect to upward mobility positions.

The defendants have produced for the Court

something more directly tailored to the actual issues

in the case, namely the number of whites and blacks

in fact selected in comparison with the number of

whites and blacks found to be best qualified, and

in turn in effect referred for consideration.

It may be noted at this point that there's

apparently something in'the neighborhood of seven

hundred or so actual promotions that occurred during

the period November 3, ’76 to October lf 1980, and

something on the order of, although the number is

less clear, a hundred and fifty perhaps announcements

of promotions that were vacated. And I can only

arrive at that figure inferentially primarily by

looking at some of plaintiffs' materials in Plaintiffs’

Exhibit 36. I say that at this point because it will

become important later on, that the Court is later

called upon to look at and make decisions or make

findings on perhaps fifty or sixty of these promotional

30

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

______________________________________________________________________________Li!___

events through direct evidence. But, the Court

recognizes that this is fifty or sixty such events,

promotional events, out of a total of something

bordering on nine hundred total for this period of

time, that is, either actual promotions or promotions

that were cancelled.

Now, returning for the moment to the defendant'i i

study, the defendant's study indicates that the

percentage of blacks rated best qualified who in fact

were selected during the period of time from one

year prior to November 3, 1976 until two months after

October 1, 1980, the selection rates for blacks out

of that best qualified group was 39.1 percent. The

selection rate for whites for that sane period of

time, 31.1 percent. Obviously such statistics give

rise to no inference of any discrimination against

blacks, and indeed if one were simply on a statistical

basis to draw any inference, it would be that whites

had been disfavored in that process. That, as a

matter of fact, from a statistical standpoint would

be significant at the .01 level, that is, with

ninety-nine percent confidence.

This same situation of overall higher selection

rates for blacks versus whites is true not only for

the entire five year period covered by the two studies,

31

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

but each of the two partial segeraents of that period.

There is no real difference between those results.

In argument it has been indicated that perhaps such

factors are not important. The Court disagrees. It

is certainly true that one may establish and prove

a claim of racial discrimination, discriminatory

treatment, even though other persons of the same

minority group may have been more favorably treated

or equally treated, and the mere fact that whites,

for example, are selected or have been selected at a

lower rate than blacks during this period of time

does not certainly establish that no black has been

discriminated against. It does, however, say this:

That there is to be no inference of discrimination

to be drawn from those basic materials, and in effect

the proof of discrimination is going to have to rest

on much more solid foundation that simply some

segmentation or stratification of parts of that

data.

The plaintiffs have categorized by way of

argument the reasons given by supervisors for select

ing the person or persons whom they chose, dividing

those responses into four categories, ranging from

clearly objective to essentially no ground, no

reason stated. Certainly that, type of endeavor has

32

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

sone potential value in a case. It does not, as I

view it, however, establish discrimination in fact,

nor give rise to an inference of discrimination in

fact. It is useful primarily in analyzing, assuming

sone prima facie case has been established of

imiuation, whether credence should be given to

the reasons articulated by the supervisors for their

decisions, and whether those reasons should be taken

as pretextural. It does not establish a prima facie

case in and of itself.

I have gone through to appraise the work

product of plaintiffs' counsel in this regard and

find it generally satisfactory in terms of the

attempted characterization of the responses and . ~

reasons given for selection or non-selection. I did

find some errors from my standpoint where I would

have made a different choice than the plaintiffs'

counsel, and some inconsistency. But I think the

important thing here is that at least as I view it

the more subjective statements for selection of whites

in comparison with the more objective reasons assigned

selecting blacks, even assuming the correct

c^aracterization, does not establish discrimination

or that discrimination has occurred. In fact, the

statistics weigh very heavily against such

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 4

33

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

------------------------- — ---------------------------In

discrimination against blacks generally.

The defendants have also presented in evidence

a study dealing with the grading of positions, that

is, a study of some one hundred and twenty-three

positions, sixty black incumbents, sixty-three white

incumbents, to ascertain whether and to what extent

there appeared to be raisclassifications and misgrading.

Such a study is obviously of importance in view of

the claim being made on behalf of the class that

there has been racial discrimination against them in

and about the misgrading of positions such that in

effect they were being denied promotions through a

misgrading approach.

Both plaintiffs' expert and defendant’s

expert agree that the percentage and proportion of

blacks who by virtue of this study that was under

taken have been misgraded is significantly greater

than the percentage of whites who have been misgraded.

It is also true, however, and both experts would

agree that the blacks were not only statistically

more often than whites undergraded, but they were also

more often than whites overgraded.

In terms of what inferences does one draw

• - >

from that, counsel perhaps have some indication from

a question that I posed during the course of argument.

34

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

1 A

The mere fact that blacks are more often misgraded

than whites does not prove anything of significance

in this case, except as one attempts to determine

what the effect of that misgrading was. Obviously

if all the evidence was to the effect that there was

no undergrading, only overgrading, and that blacks

were more often overgraded than whites, there could

hardly be a claim of discrimination.

I am convinced in this situation that the

Court must take into account not only the undergrading,

but also the overgrading, and ascertain what i3 the

net effect of the errors in grading, recognizing that

the error more frequently has occurred in this sample

with respect to blacks than with respect to whites.

That conclusion, when one in effect nets out, is to

see what the real significance of misgrading is, is

that there were four more blacks undergraded than

overgraded, two more whites undergraded than overgraded.

Given the sample sizes sixty and sixty-three respec

tively, the theoretical expected number would have

been three in each group, and is in effect a shift

of one. Actually the numbers are sufficiently small

that no real conclusion can be drawn one way or the

other. No conclusion can be drawn that there is any

adverse impact on the blacks as a result of the

35

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

raisgrading that certainly has been shown to occur.

Defendant's counsel made some argument to

the effect that one could project figures for the

entirety of the white employment group and that on

that basis there would be far more whites than blacks

undergraded. Obviously that is true. However, the

Court doe3 not believe that numbers in absolute

terms are as important in this sense as are relative

proportions. To the extent defense counsel was making

that argument the Court rejects it.

I will now be going through certain of the

incidents brought to the Court's attention during

the presentation of evidence as it relates primarily

to the question of whether as to those individuals

it has been established or shown that discrimination

in the way of a denial of a promotion occurred during

the period November 3, *66 through October 1, 1980.

I’m not sure logically quite how to go through these.

-I suppose there's no particular logical order. I

will start with Mr. Charles Bryant.

Mr. Bryant in November, 1977, was involved in

competition for equipment operator, WG-8 level. He

•iwas the only black among the five persons found to be

best qualified. He did not receive that selection,

and indeed tv/o whites with whom he had been working

________________________________________________________________________ 19

36

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

received that appointment. Mr. Bryant believed that

he not only had the qualifications for the job, but

indeed had superior experience to the white employees

who got the job.

His supervisor, Mr. Gann, testified and

indicated that all three were qualified, but that in

his opinion, that is, Mr. Gann, the two whites were

better qualified, better able to do the work, and

had had actually more experience in operating heavy

equipment than had Mr. Bryant.

Of course, the Court in evaluating this situa

tion looks to both a prima facie case of discrimina

tion from certain facts being established, but also

looks to the reason offered by a defendant employer

for its action, and then whether there is evidence

that demonstrates that that assigned reason is

pretextural such that the plaintiff would have carried

the burden of establishing,-considering the evidence

as a whole, that the denial of promotion was on

racial grounds. In this sense the Court is certainly

guided by the principles enunciated in Burdine v.

Texas College this past year, the Supreme Court out

lining just what that burden is and the fact that the

burden is ultimately on the plaintiff, and that the .

defendant is not required to in effect establish as

------------------- --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------2JL-

37

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

2 1

a part of a defense that the person chosen wa3 better

qualified than the black who was not chosen.

I conclude on this particular natter that the

reason given by Mr. Gann in testifying here was the

reason he in fact made the decision that he did.

I'm not required as I view it to decide who in fact

was better qualified, namely Mr. Bryant or the two

white individuals. I am required, I think, to decide

whether the reason that he has given for his selection

in fact was the reason that he had, whether right or

wrong, did he believe that he was selecting the

better qualified individual. To say it another way,

the way that the plaintiff would have the burden of

proving it, was he rather making that selection and

rejecting Mr. Bryant for racial reasons. I find

that he was not rejecting Mr. Bryant for racial

reasons, but made the selection on the basis of the

parsons he thought were better qualified.

It is significant in this sense that slightly

over a year later, in January of *79, Mr. Bryant

was selected over four white individuals by this

same Mr. Gann for another T7G-8 position, this one,

however, being that of cement finisher, which is

what Mr. Gann said Mr. Bryant had spent more time

doing insofar as incidental duties were concerned.

38

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

McCordis Barclay, he is here asserting that

in September, 1979, he should have received an appoint

ment as a supply technician, GS-5, which instead was

awarded to a white named Wanda Caldwell.

He further has established that although he

received a report indicating that he was one of the

best qualified persons for that position, and had

been interviewed, that in fact he had not been inter

viewed.

The Court finds in fact that Mr. Barclay was

not one of the best qualified, and that the form which

he received was erroneous. It should have reflected

highly qualified or best qualified, but not interviewed,

kut should not have, reflected certainly an interview

situation. In fact, what the evidence reflects is

that the five persons who initially were found to be

the best qualified, and who were referred for appoint

ment, that of those five that two declined that

consideration, that then there was added or to be

added two additional names; that Mr. Barclay and two

other persons were tied for sixth place on the rating

list, and that following the standard by which such

ties are to be broken. Hr. Barclay, with less years

in the service computation, was not referred for

consideration.

---------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------- 3-2----

39

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

It may here be noted that Mr. Barclay was

awarded the supply clerk job several months later,

and that then led to an appointment to the GS-5

level. Also, of course, that still nonetheless

involved a delay in reaching that GS-5 level.

I find no evidence of discrimination against

Mr. Barclay, and conclude that he simply was not

selected because of being found to be ineligible --

ineligible is not the correct word -- not being one

of the top-rated candidates for selection. It is

unfortunate that he received an erroneous form

indicating that he had been interviewed when in fact

he hadn't.

And next is the situation of Mr. Timothy

Goggins. There are two matters for the Court's

consideration with respect to Hr. Goggins, both

arose from applications made by him in December of

1976. He applied for the position of occupational

analyst, Gs-9, in the MP School. He was one of those

referred. The position, however, was abolished, that

is, not filled. In fact, it has never been filled

under the testimony, although the particular functions

of that position have, according to the defendant,

been, when required, performed by another individual

at a higher grade level who has other job functions.

______________________________________________________________________ 22_

40

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

The Court cannot find any inference that

when Mr. Goggins along with various whites didn't

get the job because the job was abolished that that

indicates any kind of racial discrimination against

Mr. Goggins. One may as well infer that it resulted

or was caused by racial discrimination against the

whites who were in the sane group. There is no

basis other than the race of the individuals who

were ultimately involved in making the decision to

cancel the position for drawing an inference in that

situation of racial discrimination.

No prima facie case under McDonald Douglas,

as I view it, is established here. And certainly

other evidence can establish that in that kind of

situation nevertheless it was prompted by or caused

by some racial bias or motivation. I find, however,

no evidence on which to draw that conclusion, that

that particular position was abolished or not filled

because of racial discrimination.

The other position that Mr. Goggins applied

for in December, 1976, was that of position classifica

tion specialist, a GS—11. In fact, the position was

not filled competitively, although announced in that

form, but was instead filled by the appointment of

a white, Earl Johnson,, who was a career conditional

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2-t*—

41

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

employee at the time. Mr. Goggins complains that that

occurred, a white was selected over him, and more

particularly that in effect there was no real competi

tion for this job by virtue of Johnson’s having

been selected. And indeed in one aspect the job was

virtually engineered down, since it was announced

as a GS-9 or 11, in fact filled by a person at the

GS-7 level.

It does appear that in part Mr. Goggins is

not a very good witness or person to make complaints

about that type of treatment, since he himself

received like or comparable treatment as a career

conditional person going through grades 5, 7, and 9

noncompetitively.

There are, of course, some differences, most

dramatically the question of this having been shown

by way of an announcement, and then in effect being

cancelled rather than simply being filled without an

announcement under this approach.

The defendant has also noted that another

black person who testified in this case had a some

what comparable situation of being promoted non

competitively, n a m e l y Margaret Colley. Again there

are some distinctions. Mr. Clark testifying indicated

that he did not think that Mr. Goggins actually could

----------------------------------------------------------- 05-

42

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

have handled this job had it in effect been handled

on a competitive basis. I do not find this selection

of Johnson to be discriminatory on a racial basis,

that is, to be prompted by racial discrimination.

It may have been prompted in part by a belief critical

of Mr. Goggins' abilities, but that does not

discrimination make. The mere fact that some super

visor does not believe that someone’s qualifications

are good, or as good as someone else, the mere fact

that that person is black, does not mean that that

decision is racially motivated, particularly in view

of what had already occurred with Mr. Goggins himself

in coming through this sequence of positions, and

with what we find to be true with at least one other

employee. I find nothing unusual or significant in

the appointment of a career conditional person

other than the fact that the announcement did go out

initially. I conclude that there was no discrimina

tion involved in this non-selection of Goggins for

that position.

It may be noted that approximately a year

after this event Mr. Goggins was in fact awarded a

GS-11 position at another post, which he accepted,

and where he is now serving. Whether Mr. Clark’s

analysis or expectation that Goggins would not be

- 43 -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

able to handle the work is correct or incorrect, of

course, is problematical, though the evidence did

reflect that Mr. Goggins was held up on one step

raise because of poor performance.

The Court will at this time take a short

recess before continuing with findings and conclusions.

(SHORT RECESS)

THE CODRT: Next Mr. Bobby Murphy. In 1977

Mr. Murphy sought a job as supply management office,

GS-7, a job in fact that was filled by a white, Mary

Barber. Mr. Murphy was rated as not qualified, that

is, not meeting the minimum qualifications established

through the OPM regulations.

It may here be noted that this decision of

ineligibility was made by a rating panel. The Court

has heard from two of the members of that panel,

one of whom is a black and is a member of the

complaining class here.

The Court finds that the rating of Mr. Murphy

as not qualified for that job was not the product

of any racial discrimination practiced by the panel

members. It may here be noted that notwithstanding

the fact that Mr. Murphy had been convicted of an

offense involving theft of property some several

years earlier from his employer, he nevertheless in

______________________________________________________________________________ 22—

44

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

1900 was selected for an additional promotion as

chief of the storage section.

The Court finds no discrimination against

Mr. Murphy with respect to his not being selected as

supply management officer.

Mr. Clyde Woodard# in effect# lost pay when

he was “promoted" back in 1975 to produce manager,

GS-5, having left a WG-5 position. In 1973# I

believe it was, a formal# or at least an informal

complaint was made by Mr. VJoodard to this underpay

or loss of pay for what was supposed to have been a

promotion, comparing his situation with that of a

white woman who had similarly gone from one schedule

to the other, Sarah Herndon. When this was evaluated,

in fact Hr. Woodard received that increase in pay

in his steps in the grade, and indeed recovered all

back pay.

While the Court would not from the evidence

presented have concluded that thi3 error in classifica

tion or in pay grade was as a result of racial

discrimination, in any event he has received full

correction for that matter.

He then applied for the position of warehouse

foreman, WS-5, and has here complained that a white

by the name of George was selected. Hi3 claim is

__________________________________________________________ 28

45

that that selection of George and his own non-selection *

was the result of racial discrimination, a somewhat

curious contention in view of the fact that the

person first selected for thi3 job, Bobby Murphy, ;

is a black, Mr. Murphy having declined, however, that *j*,*

position.

In any event, again, while the Court would

not on the basis of the evidence presented have found

that there was racial discrimination in the selection

of Mr. George over Hr. VJoodard, in any event Mr.

Woodard was successful on an administrative review

of that matter, was awarded this sane position,

ultimately a warehouse foreman, WS-5, and indeed got

back pay for the period of time that he had been

delayed in getting that appointment.

There is no active complaint accordingly by

Mr. Woodard for remedial action by the Court even

if the Court had found racial discrimination.

Mr. Jack Heath had no denial of a promotion

during the applicable period of time about which any

complaint is here made. He did testify dealing with

other aspects of employment discrimination as he

perceived it, which might have some effect upon one's

promotional opportunities. But, insofar as being

denied any promotion from November 3, 1966, to

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19