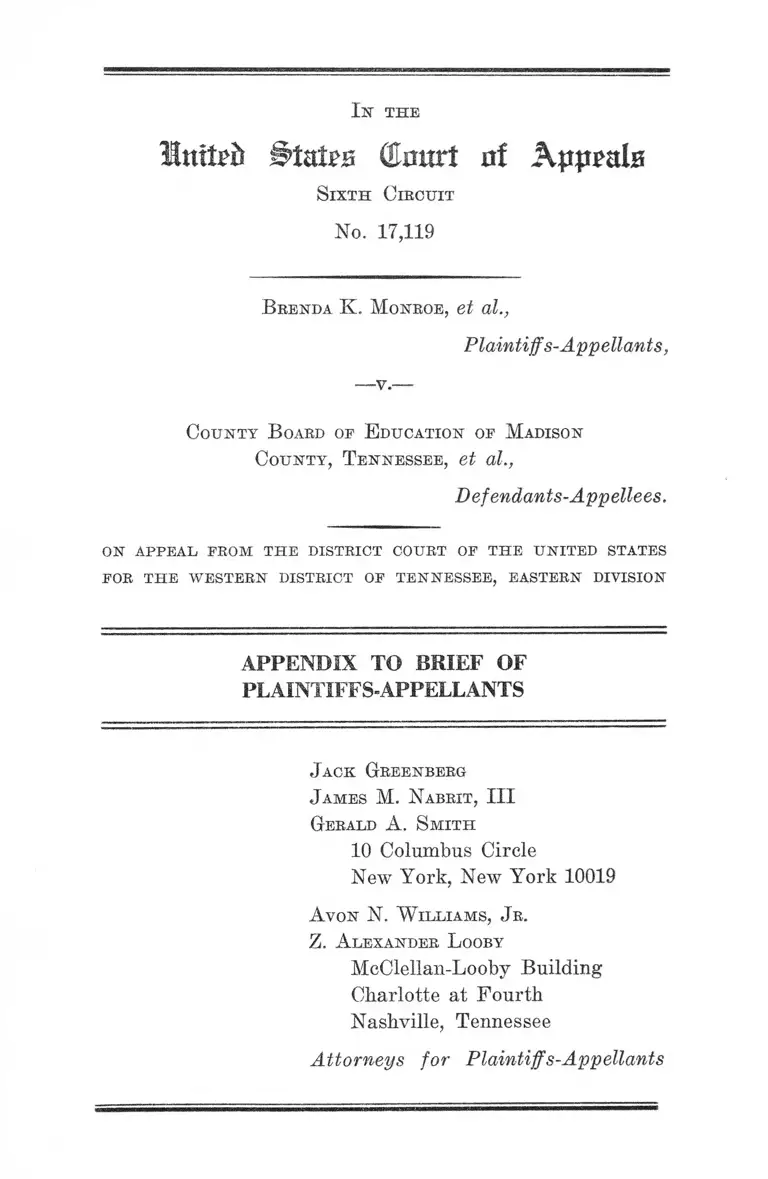

Monroe v. Madison County, TN Board of Education Appendix to Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Monroe v. Madison County, TN Board of Education Appendix to Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1967. 8928c71d-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/adba8cfd-7d87-44ff-805d-c4bb7e7051b1/monroe-v-madison-county-tn-board-of-education-appendix-to-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n’ the

I n M Snivel uf A p p e a ls

Sixth Ciecuit

No. 17,119

B renda K . Monroe, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

—v.---

County B oard oe E ducation op Madison

County, Tennessee, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

ON appeal prom the district court of the united states

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OP TENNESSEE, EASTERN DIVISION

APPENDIX TO BRIEF OF

PLA1NT3 FFSAP PELL ANTS

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Gerald A. Smith

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

I N D E X

Relevant Docket Entries ......... la

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief ___ __________ 2a

Defendants’ Reply to Motion for Further Relief .... 8a

Transcript of Hearing Held on June 25, 1965 .............. 12a

T e s t i m o n y :

Plaintiffs’ Witnesses:

Glynn White—

D irect..................................................................... 18a

Cross ........................................ 23a

Redirect .............................................. ..... ..... 30a, 32a

Recross ......... ..... .............................. ........ ..... 32a, 33a

Nathaniel Benson—

D irect.............. ................................................. 35a

Cross .............. ......... .................................... ..45a, 91a

Redirect.......... ............................................... 71a

Recross ................................................. 71a

Gladys Wilson—

D irect............................................... 50a

Cross ............................................................... 55a

Redirect................................................. 71a

Recross ........................................... 71a

Cecil Shipp—

Direct ................................................................... 74a

Cross ........................................... 79a

PAGE

Walker D. Bond—

D irect............................... 81a

Cross .................................................................. 84a

Redirect............ .................................................. 87a

Recross .............................................................. 89a

R. B. Yann—

Direct ........... 94a

Cross .................................................................. 99a

Floyd Jackson—

Direct ................................................... 101a

Cross ............................... 103a

Redirect ............................................................ 106a

Wilford Joyner McBride-—

Direct ................................................................ 109a

Cross .................................................................. 112a

Willie D. Boone—

D irect................................................................. 114a

Cross .................................................................. 120a

Redirect ...... 120a

Recross ............... 120a

M. T. Meriwether—

Direct ................................................................. 122a

Cross ................................. 129a

Redirect ............... 139a

Janies A. Cook—

Direct ....... 140a

Cross ................ 143a

Redirect .................................................. 149a

Recross .................. 150a

ii

PAGE

XU

Defendants’ Witness:

J. L. W a lk er-

Direct .................................................................. 153a

Cross ................................................................. 165a

Defendants’ Exhibit 1

Report of Survey on Number of Families Ad

versely Affected by Schools Opening in August 193a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

Total Enrollment of Pupils in Madison County,

Tennessee 1965-1966 (With Racial Breakdown) 199a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 6

Report Card of Dyka Benson .............. 202a

Memorandum Decision of District Court, Filed

Aug. 2, 1965 ..................................... 206a

Order of District Court, Filed Aug. 9, 1965 ............... 210a

Notice of A ppeal........ ...................................................... 213a

Docket Entries ................................................................ 214a

Clerk’s Certificate .......................................................... 216a

PAGE

Relevant Docket Entries

1965

4 - 14 Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief against

defendants County Board of Education of Madison

County and James L. Walker, Madison County

School Supt.

5- 10 Defendants’ (County Board of Education & James

L. Walker, Madison Co. School Supt.) Reply

to Motion for Further Relief.

8-2 Memorandum Decision of District Court relating to

County Schools.

8 - 9 Order of District Court on Memorandum Decision

relating to County Schools.

9 - 7 Notice of Appeal from Judgment entered Aug. 9,

1965 relating to Madison County Schools.

1966

2-14 Filed Court Reporter’s Transcript of Proceedings.

2a

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief Against the Defend

ants, Comity Board of Education of Madison County,

Tennessee and James L. Walker, Madison County

School Superintendent

Filed April 14, 1965

[Caption Omitted]

The plaintiffs, by their undersigned attorneys, move

this Court for an order granting further relief in this ease

against the defendants, County Board of Education of

Madison County, Tennessee, and James L. Walker, Madi

son County Superintendent. The further relief sought is

an order directing said defendants to: (1) allow a more

adequate length of time for registration of pupils in the

Madison County Schools for the school year 1965-66;

(2) assign teaching, supervisory and other professional

and supporting personnel to schools in the Madison County

School System on the basis of qualification and need and

without regard to the race of the personnel or of the

children in attendance; (3) eliminate all racial distinc

tions, restrictions and discriminatory practices in teacher

in-service training activities and other professional or

school-related activities of teachers; (4) eliminate all ra

cial restrictions and discriminatory practices from all

school-sponsored or school-related curricular and extra

curricular activities, including musical concerts and other

cultural affairs; (5) eliminate racially discriminatory poli

cies with respect to the provision and operation of the

school transportation system; and (6) eliminate all other

racial classifications from the operation of the Madison

County public school system.

3a

In support of this motion, plaintiffs show unto this

Court the following:

1. On 21 May 1964 this Court entered an order direct

ing desegregation of grades 1 through 8 of the Madison

County school system for the school year 1964-1965 and

grades 9 through 12 for the school year 1965-1966; pro

viding that with respect to desegregated grades pupils

were to attend the school of their choice, for implementa

tion of which a registration was to be held not later than

June 20, 1964 and June 20 of each of the succeeding four

years. Among other things the order provided that

“ transportation facilities and school facilities, including

cafeterias, as well as school facilities, including athletics,

will be desegregated.” The Court’s order further provided:

“ The application of plaintiffs for desegregation of faculties

will be held under advisement pending the implementation

of this plan.”

2. Defendants have mailed notices to parents or guard

ians of school children advising that school registration

for the school year 1965-1966 will be held on April 16,

1965 between the hours of 8 :30 A. M. and 3 :00 P. M. and

on April 17, 1965 between the hours of 8:30 A. M. and

12:00 Noon, at each school (grades 1-12, inclusive) oper

ated by the Madison County school system. Said registra

tion period falls in the Easter vacation and provides an

insufficient amount of time for parents or guardians to

select the school in which they shall register their children

and an insufficient amount of time for the actual registra

tion of such children.

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief Against the

Defendants, County Board of Education of

Madison County, etc.

4 a

3. Defendants have done nothing since the Court’s order

in this case to desegregate the teaching, supervisory and

other professional and supporting personnel in the Madi

son County school system, including bus drivers. Con

tinued segregation of such personnel adversely affects the

choice available to Negro and white pupils under the

Court’s order by retaining an aspect of racial segregation

and designation in the operation of individual schools

in the school system. The retention of such racial designa

tion and discrimination in faculty and personnel assign

ment also affects the education received in the school

system and thereby deprives these plaintiffs and the class

they represent of due process of law and equal protection

of the law secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

4. Defendants continue to retain racial distinctions in

activities related to faculty training and professional

achievement. For instance, during the week of 4 April

1965 defendants released all white teachers assigned to

formerly white schools in the school system to attend a

meeting of the Tennessee Education Association in Nash

ville, Tennessee, allowing them their regular pay for this

professional activity, but denied all Negro teachers as

signed to the formerly Negro schools the privilege of

attending said meeting, and required them to perform

their regular school duties during those days.

5. Defendants continue to sponsor or allow the schools

to participate in curricular and extra-curricular activities

on a racially discriminatory basis. For instance, on 11

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief Against the

Defendants, County Board of Education of

Madison County, etc.

5a

February 1965 the Jackson Symphony Orchestra gave a

young people’s concert for certain elementary grades in

the Jackson City Schools and the Madison County Schools.

Only the children attending formerly white schools were

permitted to attend these concerts. Defendants excluded

nearly a third of the children in the Madison County

school system. All of those excluded were Negro children

attending all Negro schools staffed by all Negro faculties.

6. Defendants continue to assign white bus drivers to

buses serving formerly white schools and Negro bus drivers

to buses serving formerly Negro schools. Also, defendants

continue to discriminate racially in the laying out, exten-

tion or alteration of routes necessitated to permit trans

portation of Negro school children to and from formerly

white schools when selected for attendance by them.

W herefore, plaintiffs pray for an order directing defen

dants t o :

1. Send additional notices to all parents or guardians

of children in the Madison County school system allowing

them at least an additional month in which to select the

school of their choice for the 1965-1966 school year, and

thereafter allowing at least three full days for the reg

istration of said children at the individual schools;

2. Assign teaching, supervisory and other professional

and supporting personnel to schools in the Madison County

school system on the basis of qualification and need and

without regard to the race or color of the personnel as

signed or of the children in attendance;

Plaintiff s’ Motion for Further Relief Against the

Defendants, County Board of Education of

Madison County, etc.

6a

3. Eliminate all racial discrimination and racial distinc

tions as to any teacher in-service training or other pro

fessional or school-related activities performed by teachers

in the school system, or under the direct or indirect spon

sorship or support of the school system;

4. Eliminate all racial restrictions, distinctions, segre

gation and discriminatory practices from all school-spon

sored curricular and extra-curricular activities, including

musical concerts and other cultural activities conducted

for school children under the direct or indirect auspices

of or with the cooperation of the Madison County school

system;

5. Assign bus drivers without regard to the race or

color of the driver or of the pupils riding said buses and

without regard to the former racial character of the school

or schools served by said buses; and eliminate all racially

discriminatory policies and practices with respect to the

laying out, extension or alteration of bus routes and with

regard to the provision of transportation of children to

the school or schools selected by them for attendance;

and

6. Eliminate all other racial classification, distinctions

and practices from the operation of the Madison County

public school system.

Plaintiffs further pray that this Court set this motion

for immediate hearing, to the end that further relief may

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief Against the

Defendants, County Board of Education of

Madison County, etc.

7a

be effective for the school year commencing in September,

1965.

Z. A lexander L ooby

Avon N. W illiams, Jr.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

J ack Greenberg

Derrick A. B ell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief Against the

Defendants, County Board of Education of

Madison County, etc.

By ...................................................

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs.

8a

Filed May 10, 1965

Defendants’ Reply to Motion for Further Relief

[Caption Omitted]

Defendants, County Board of Education of Madison

County, Tennessee, and James L. Walker, Madison County

Superintendent, for reply or answer to the motion for

further relief filed in this cause by plaintiffs, say:

1. Defendants admit the averments in support of said

motion set forth in Paragraph 1.

2. Defendants admit the averments set forth in Para

graph 2 except that they deny that the pupil registration

period for the school year 1965-1966 provided “an insuffi

cient amount of time for parents or guardians to select

the school in which they shall register their children and

an insufficient amount of time for the actual registration

of such children.” Defendants would show that the reg

istration for said school year has already been held, that

the registration period lasted for 1% days, that this was

a half day longer than the normal registration period and

provided ample time for the actual registration of pupils,

that the registration was held on April 16 and 17, 1965,

that registration notices were mailed to parents or guard

ians on March 31, that a copy of the form of the registra

tion notice was mailed to counsel for plaintiffs on March

12, that no objection thereto was made by plaintiffs or

their counsel until on or about April 14 when the motion

for additional relief was filed herein, that the desegrega

tion plan instituted by defendants pursuant to order of

this Court has been a matter of common knowledge since

9a

May, 1964, and that parents and guardians have had more

than ample time in which to select the school of their

choice. Defendants would further show that for the school

year 1965-1966, 68 Negro students have registered in for

merly white elementary schools and 24 Negro students in

formerly white high schools.

3. Defendants admit that there has been no desegrega

tion of faculties but deny that this adversely affects or

deprives plaintiffs of their constitutional rights. Defen

dants deny the other averments of Paragraph 3, except

as hereinafter indicated. Defendants would show that they

employ only two supervisors of instruction and that one

supervisor is white and the other Negro; and defendants

would further show that Negro and white children are

being transported to school in the same school buses but

that, for disciplinary reasons, the driver of each bus is

of the same race as that of the majority of the students

being transported.

4. Defendants deny that they continue to maintain racial

distinctions in activities related to faculty training and

professional achievement. Defendants would show that the

Negro teachers in the county school system do not belong

to the Tennessee Education Association and were, there

fore, not released for the purpose of attending the April 9,

1965, Nashville meeting of said association; but defendants

would further show that the Negro teachers belong to a

similar association known as the Tennessee Education

Congress, that a meeting of this latter association was

held on the same date in the same city, that all Madison

County schools were closed on April 9, 1965, and that

the Negro teachers were at liberty to attend the meeting

Defendants’ Reply to Motion for Further Relief

10a

of the Tennessee Education Congress if they wished to

do so.

5. Defendants deny that they “continue to sponsor or

allow the schools to participate in curricular and extra

curricular activities on a racially discriminatory basis.”

Defendants admit, however, the Jackson Symphony Or

chestra incident referred to in Paragraph 5 but would

show that this was an extra-curricular activity, that they

had no control over the invitations extended by the spon

sor of this concert, and that invitations were extended

only to students in grades five and six of formerly white

schools. Defendants are advised that this was because

of the limited seating capacity and would show that both

Negro and white fifth and sixth grade students attended

this concert.

6. Defendants admit that they continue to assign white

bus drivers to buses serving formerly white schools and

Negro bus drivers to buses serving formerly Negro schools,

but defendants would show that this is very essential,

particularly during this transitional period, to the main

tenance of order and discipline on the buses, and defen

dants deny that this practice adversely affects or deprives

plaintiffs of their constitutional rights. Defendants deny

that they have discriminated racially in the laying out,

extension or alteration of bus routes, and would show

that on several occasions they have extended bus routes

solely for the purpose of enabling Negro students to attend

formerly white schools.

/ s / J ack Manheik, Sr.

J ack Manhein, Sr.

Attorney for named Defendants

First National Bank Building

Jackson, Tennessee

Defendants’ Reply to Motion for Further Relief

11a

Certificate of Service

I certify that I served the foregoing reply or answer on

Emmett J. Ballard and Avon N. Williams, Jr., Esqs.,

attorneys for plaintiffs, by depositing on the 10 day of

May, 1965, two true copies thereof in the U. S. Mail,

postage prepaid, in envelopes addressed respectively to

each of said attorneys at their respective addresses as

set out in the complaint, which addresses are the last

addresses of said attorneys known to me.

/ s / J ack Manhein, Sr.

J ack Manhein, Sr.

Attorney for named Defendants

First National Bank Building

Jackson, Tennessee

12a

Transcript of Hearing Held on June 25, 1965

— 390—

The trial of this case was resumed with relation to the

Board of Commissioners for Madison County, on this date,

Friday, June 25th, 1965, at 9:30 o’clock, a. m., when and

where evidence was introduced and proceedings had as

follows:

The Court: Mr. Manhein, are you ready in the

motion?

Mr. Manhein: Yes, sir.

The Court: I believe we had better get Mr. W il

liams so we can get going here.

This is No. 1327, Monroe against the Board of Edu

cation of Madison County. We have heretofore held

a pre-trial conference in connection with the Motion

of the plaintiffs for additional relief, and we set

the motion for hearing today. Now, what were the

main issues that were generally agreed at the pre

trial conference to he taken up in this case? What

do you concede to be the main issues, Mr. Williams?

Mr. Williams: May it please the Court, one issue—

the issue of registration time was resolved in the

- 3 9 1 -

pre-trial conference by agreement of the parties

before the Court; that is this matter of registration

time. It was agreed that the plaintiffs would be

allowed until July the 6th, and on that date that all

children who had not heretofore requested—that all

children who desire to request admission to another

school could do so at the office of the Superintendent,

if I am correct, all children who were not satisfied

with the registrations they made during the month

13a

of April could register at the school of their choice

on July 6th at the Superintendent’s office.

The Court: Is that your understanding, Mr. Man

hein?

Mr. Manhein: Yes, sir, if I understood Mr. W il

liams. There will simply be a single day’s registra

tion, from 9:00 to 12:00, I believe was agreed, and

1 :00 to 5 :00 on July the 6th.

The Court: All right, sir.

Mr. Williams: And as I understood it, in the

future, although the Court’s order specified ten days

—3 9 2 -

notice to the parents, the defendants agreed that

thirty days notice would be afforded of registration.

Mr. Manhein: We have no objection to that, Your

Honor. I assume there will be an order to that

effect. If not, I may forget it next year.

The Court: All right. We will put that in any

order we enter on this motion. We give thirty days

notice of registration date.

Mr. Williams: Yes, sir.

The Court: All right. Now, what?

Mr. Williams: If the Court please, there was

some question about the number of days allowed

for registration in the pre-trial conference. While

I don’t think it is a major issue—

The Court: (Interposing) How much time do

you allow?

Mr. Manhein: Your Honor, a day and a half. We

customarily register a single day’s time, or we al

lowed a day and a half.

Proceedings

14a

Proceedings

— 393—

Mr. Williams: I think we requested, if I recall

correctly, Your Honor, three days, two or three days.

Mr. Manhein: Well, Your Honor, it seems to me

there is no need to require us to devote three days

to it unless it is necessary.

The Court: Well, that will be a matter for deter

mination by the Court. If plaintiffs want to offer

proof that a day and a half is not sufficient, why, of

course, they are entitled to do so, but it is not up

to the School Board to suit the convenience of all

concerned if they allow reasonable time and give

adequate notice and there is no problem in processing

the registrations and the time to be allowed, then

certainly that would meet the constitutional test.

Mr. Williams: If the Court please, I don’t believe

that is going to be a major problem.

The Court: All right, sir.

Mr. Williams: Now, if Your Honor please, the

next issue which was not resolved and remains un

resolved was the issue of faculty desegregation.

The Court: All right, sir.

— 394—

Mr. Williams: And then there was an issue that

sort of goes along with that, or perhaps not—maybe

it goes along—there was an issue of faculty training

and professional activities, and then there was an

issue of extra-curricular activities. Now, it may be

that both of those issues are more properly allied

together.

The Court: Faculty training and professional

activities and what else?

15a

Mr. Williams: And the next issue would be extra

curricular activities.

The Court: All right. What else do we have?

Mr. Williams: There was an issue of white bus

drivers and discrimination in bus routes. The issue

of white bus drivers may or may not—the Court may

or may not consider that as being an issue that the

Court will hear today. The Court expressed itself

in no uncertain terms as feeling that it was bound

by the decision in the Mapp case in the Sixth Cir

cuit. However, if the Court please, the defendants

admit that they are assigning bus drivers to buses

— 395—

on the basis of a majority of students riding the

particular bus. We feel that that is clear discrimina

tion.

The Court: Well, if you can explain to the Court

how the Court could possibly interpret the Mapp case

any other way than the way the Court interpreted

it, then we would be glad to entertain your conten

tion, but as we understood Judge O’Sullivan’s opinion

in the Mapp case, he said clearly that while in these

class actions filed by students and their parents,

they could maintain a claim to desegregation of

faculties as part of their claim to an abolition of

discrimination in the schools, but he clearly held,

as we understood the opinion, that you can’t main

tain such a claim with respect to supervisory person

nel and housekeeping personnel and that type of

thing.

Mr. Williams: Your Honor is correct on that.

However, the Fourth Circuit, I believe, has held,

and there are some other circuits which have held,

Proceedings

16a

certainly the Fifth Circuit, to the contrary, and at

—3 9 6 -

least one District Judge here in Tennessee. It may

be that the matter was not brought to his attention

at the time. I don’t think we did bring the matter

to Judge Miller’s attention.

The Court: I believe that’s the Sloane case.

Mr. Williams: Yes; in that case he included bus

drivers.

The Court: I notice he did that, and we wondered

since you are supposed to follow the law of your

Circuit, if the Circuit Court of Appeals has spoken,

we wondered how he did that, and we surmised that

that point was not brought to his attention.

Mr. Williams: My recollection is that it was not,

if Your Honor please.

I would submit, if Your Honor please, that the

Court permit us—I would ask the Court to permit

us to offer proof on this question in the event that

we should decide to reserve our rights, in the event

that we should decide to attempt to get a more

—397—

favorable decision out of the Sixth Circuit.

The Court: Well, you are entitled to put on your

proof and make your report. You are certainly en

titled to do that.

Mr. Williams: Now, if Your Honor please, of

course we have an issue of discrimination with re

gard to bus routes. Now, frankly, whether that

exists or continues to exist, I am not fully apprized

this morning, and as Your Honor saw, our clients

were late in getting here. It did exist last year. It

may not exist now.

Proceedings

17a

The Court: You are going to investigate that on

the witness stand, is that right I

Mr. Williams: Perhaps at recess time.

Now, if Your Honor please, a very important issue

which the Court held that we could raise was the

issue of the split season. The Court specifically

directed both sides to bring such proof as they might

desire on the question of the elimination of the split

season.

Mr. Manhein: In that connection, Your Honor,

there has been no formal amendment of the motion.

—398—

I don’t know whether counsel contemplates that or

not, but I have been expecting it. I just call that

to the Court’s attention. I don’t make any issue of

it.

The Court: You are correct in stating that the

split season issue was not raised in the motion for

further relief. But Mr. Williams did say in the pre

trial conference that was a side issue and it was

discussed, and it comes as no surprise to the de

fendants, so I think we could go ahead and hear it,

whether or not it was actually included.

Mr. Williams: I f it please the Court, that issue

was raised in the original specifications.

The Court: Yes. He is not denying that. He

pointed out that it was not raised in the motion for

further relief, but he is not contesting your right to

have it litigated at this time, because it was men

tioned at the pre-trial conference, and he is not sur

prised by it.

Proceedings

18a

Mr. Williams: I believe that constitutes a state-

—399—

ment of the issues, Your Honor.

The Court: Do you see any other issues, Mr. Man-

hein?

Mr. Manhein: Your Honor, I don’t see any other

issues, but I had thought that we had resolved that

faculty in-service training issue, if there is an issue,

at the pre-trial conference. Your Honor will recall

that at the conference we took the position we had

no objection to any order with respect to faculty

in-service training, as long as we knew just exactly

what we could do and could not do. So I don’t know

whether that’s an issue or not.

The Court: We didn’t carry away the feeling from

the pre-trial conference there was any hot issue on

that, to say the least, but if Mr. Williams wants to

offer some proof as to what is being done, he is

entitled to do that, and it is up to him how strongly

he wants to urge it as a ground for relief.

All right, Mr. Williams, you may put on your

proof.

—400—

Mr. Williams: Call Mr. White.

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

Glynn W hite, the said witness, having been first duly

sworn, testified as follow s:

Dir ext Examination by Mr. Williams:

Q. State your name, please. A. Glynn White.

Q. What is your age? A. Thirty-seven.

Q. Where do you live! A. Route 1, Denmark.

19a

Q. Is that Madison County, Tennessee? A. Yes, sir.

Q. How long have you lived in Madison County? A. All

my life.

Q. What is your occupation? A. Farmer.

Q. How many school children do you have? A. Four.

Q. Are they enrolled in the schools of Madison County?

—401—

A. Three of them is.

Q. In what school? A. Two of them at Huntersville

Elementary.

Q. What are their names? A. Beverly White and Ro

lando White.

Q. Where is the other one enrolled? A. North Side

High School; Glenda White.

Q. I believe Glenda is one of the plaintiffs in this case?

A. That’s right.

Q. And you are one of the plaintiffs in this case? A.

Yes.

Q. Now, Mr. White, I believe both Huntersville and

North Side are formerly schools that have been deseg

regated? A. Yes.

Q. And your children have been attending there under

the order of this Court? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, Mr. White, which do you believe would be the

better situation for your children, a school where the teach

ers are all white, or a school where the teachers are deseg

regated and mixed as are the students? A. I believe the

—4 0 2 -

schools that would be desegregated would be the most ef

ficient for the students.

Q. You mean by that a school desegregated as to faculty

as well as students? A. Yes.

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

20a

Q. Do you have any reason for that belief? A. Well,

one reason, as they grow, they get better relations, socialize

together and communication.

Q. You believe that they get that better where the teach

ers are desegregated than they do where the teachers are

all-white, is that right? A. Yes.

Q. Now, you recall last year when this desegregation

plan went into effect, all children were required to select

the school that they wanted to attend, you remember that,

do you, in the county school system? A. That’s right.

Q. State whether or not all the white children in Madison

County selected and went back to white schools, is that

true? A. That’s right.

Q. And I believe you are aware that there were very

—403—

few negroes who elected to go to the white schools? A.

Yes, sir.

Q. You are aware of that? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you feel that the apparent reluctance of negroes

to select white schools is related in any way to the fact that

the teachers and principals in those schools were all white?

A. Yes, sir, I do.

Q. What is the relation? A. Well, the parents, I feel

like they are a little reluctant because—-because of the resi

dences, the places that they live, have a part to do with

the reason why they are reluctant to register their children

in all-white schools.

Q. Do you feel like the fact that they are all-white fac

ulties, all-white teachers—

Mr. Manhein: Your Honor, we object to this tes

timony as to this man’s feelings. Now, he can testify

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

21a

to facts, but counsel is asking Mm about Ms general

feelings on the subject.

— 404—

The Court: Well, he can testify about what his

attitudes are, because that is one of the facts in the

case.

Mr. Manhein: But he is talking about the general

feeling in the community, as I understood, his state

ment as to what the general feeling in the community

is.

Mr. Williams: I asked him whether he felt that

the all-white faculties had anything at all to do with

the fact of there not being any negro children to se

lect all-white schools.

The Court: Wouldn’t that be hearsay, because he

would have to base that on what other people told

him. He can testify as to how it may or may not

have influenced him, but for him to make a statement

as to how other people felt would, of necessity, be

hearsay, wouldn’t it!

Mr. Williams: Well, if the Court please, I would

suppose, yes, in all intellectual honesty, except, as I

said the last time before this Court, these Courts

have heard a lot of hearsay in these cases.

— 405—

Q. Mr. White, you say you have lived in this county

all your life? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you are familiar with this split season, this let

ting off children, letting them out to attend the harvest!

A. Yes, sir.

Q. As a parent of negro school children and a plaintiff

in this case, do you feel that that is good, that that is edu

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

22a

cationally sound for the children, to start them to school

in July and then let them out for harvest season and split

the season like that? A. No, I do not.

Mr. Manhein: We object on the ground that that

fact is stipulated, that it is not educationally sound.

The Court: I don’t believe the School Board makes

any contest on that issue.

Mr. Williams: Fine.

Q. Now, Mr. White, are you familiar with the general

economic condition of negro farmers in Madison County?

A. In part, yes, sir.

Q. Well, what do you mean by in part? A. Well, I

— 406—

would say about seventy-five percent of them.

Q. Now, based on that knowledge of approximately sev

enty-five—and is that personal day-to-day daily knowledge

that you have gained over your entire lifetime since you

have lived up there? A. That’s right.

Q. Based on that personal knowledge, is it your opinion

that there is any economic necessity among negro farmers

in Madison County for this split season to prevail, to con

tinue this split season? Do you feel that there is any eco

nomic necessity for it? A. No, I do not.

Q. Mr. White, where the School Board has a choice plan

like this, and children have to select the place where they

go to school and have to go down and have a pre-school

registration in the spring—you are familiar with that,

aren’t you? A. Yes.

Q. How many days, in your opinion, are required in a

large county like Madison County for the parents and

children to actually get their children over to the schools

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

23a

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Direct

—407—

and effect this registration in such a manner that they all

have a fair chance at it? How many days do you think the

Board should allow for registration! A. I would think

they should allow at least five days for registration.

Q. Madison County is kind of a large county area-wise,

is it not? A. Yes, that’s right.

Q. State whether or not there are people who get con

fused, who get the wrong information about the day and

that sort of thing? A. Well, the time that they allow this

spring for registration, which my own opinion, I do think

that it was not enough time, because people do get con

fused. The children want to go to these previous schools,

and then they probably meet somebody, and they talk them

out of it, and I think they should have at least four or five

days to concentrate over the matter.

Q. Now, one more thing I want to ask you, Mr. White.

Where all the formerly white schools, the schools that used

to be white schools continue to have all-white teachers and

principals and all the negro schools, formerly negro schools,

- 4 0 8 -

have all-negro teachers and principals, does that help to

keep those schools identified as negro and white schools

in your mind? A. I think so.

Q. It does? A. I think so.

Q. Would it help to eliminate this racial designation of

these schools if they desegregated the teachers and mixed

the teachers as well as the students in these schools? A.

Yes, sir, I think so.

Q. You could, then, forget that East High used to be a

negro school, perhaps, is that right? A. That’s right.

24a

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

Mr. Williams: You may cross-examine.

Cross-Examination by Mr. Manhein:

Q. What business did you say that you were in? A.

Farming.

Q. You haven’t had any experience in school adminis

tration, have you? A. No, I haven’t.

—409—

Q. None of any kind? A. No, I haven’t.

Q. Have you ever been a teacher? A. No.

Q. Have you ever been in any way identified with any

schools or school system? A. No, I have not.

Q. Now, tell me again why you think that we need to

take five days in Madison County to register pupils? A.

The reason is because Madison County has quite a few

students. I notice it was up in the thousands to register

this time, and it seems to me that it’s impossible to register

them in a day and a half with so many thousand students.

Q. Do you know how long it has been taking for the last

twenty years to register the students in Madison County,

how many days? A. Well, not exactly, but I do think that

it has been more than a day and a half.

Q. Do you know how long we took to register students

this year? A. A day and a half.

—410—

Q. Do you know how long we took last year? A. No, I

do not.

Q. Or the year before? A. No, I do not.

Q. Well, do you know whether there was any difficulty

involved in registering these students in a day and a half

time this year? A. I know this year it was difficult be

25a

cause some of the students that had planned to register,

they happened to be away at that time, and couldn’t make

it back.

Q. You mean some of them were out of town at that

time! A. Yes.

Q. You really don’t know, or really don’t have the slight

est conception of how much time really is needed to register

our pupils? A. I believe you need more than a day and

a half.

Q. And your only reason for it is that somebody might

be out of town? A. That’s not the only reason, but just as

I stated before, probably some of the parents would like to

think of the situation before they jump right into it.

Q. Well, let’s assume that they had thirty days to think

- 4 1 1 -

over what school they wanted to register in or have their

children register in, would that be ample? A. Well, I

would think so, if they had thirty days to think over it.

Q. I f they had thirty days to think over it, in your

opinion, would a day and a half be enough time to actually

conduct the registration of those students? A. It’s a pos

sibility, if they had time to think over it.

The Court: Let me ask you this: Were you

around any of the schools on the last registration

days?

The Witness: Yes, sir, I was.

The Court: Well, was there any mechanical diffi

culty in handling those who were there to register?

Were there any turned away because they couldn’t

put them on the books?

The Witness: The school that I register my

daughter to, it was no difficulty there.

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

26a

The Court: Do you know of any difficulty of

the people that came to register that had any

trouble actually being registered? Were the lines

—412—

too long so that when they got to the end of the

day there were people standing in line waiting to

register ?

The Witness: Personally, I don’t know of that.

The Court: Isn’t what you are really saying is

that the problem is that they didn’t actually get

the word about when the registration was going

to be soon enough, rather than the time being ac

tually allotted for registration? Isn’t that what you

are saying?

The Witness: Judge, Your Honor, I notice that

several say they would have registered, but the

time was too short.

The Court: You mean at which they got the notice

of the registration?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: We are talking about two different

things here. Now, what Mr. Williams is seeking

to prove by you is a day and a half is simply not

enough time, assuming you know when that is going

to be—assuming there is plenty of notice that when

that day and a half is going to be, that that’s just

—413—

not enough time to handle the people that come

there to register. Now, is it your contention that

a day and a half is not enough time?

The Witness: That’s my statement.

The Court: And what do you base it on ?

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

27a

The Witness: The population of the students in

Madison County.

The Court: But you don’t know of any actual

example of anyone being prevented from register

ing who showed up, because there were too many

people there on that day?

The Witness: No, I don’t.

The Court: You are basing it on the number of

people in Madison County, the number of students

in the school system?

The Witness : Yes, sir.

The Court: All right, sir.

By Mr. Manhein:

Q. Now, you have expressed the opinion that there was

no economic necessity in Madison County for the split

school season that we have had there for a good many

years. What do you base that opinion on? A. Well, I

—414—

just don’t think that there has been an economic purpose,

because people do not have to stop their children out of

school to pick the cotton.

Q. Isn’t it true that a large number of families, of

negro families in Madison County do use their children

to pick cotton during the harvest season? A. At present

that is true.

Q. Is it true? A. At present.

Q. Well, don’t you think that’s necessary from the

standpoint of these families themselves to have their

children pick cotton and help them in that fashion? A.

No, sir, I do not.

Q. Why not? A. Because I think that the children

should, the parents should not deprive their children of

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

28a

an education to pick cotton. I do feel like the education

is more benefit that cotton picking.

Q. But that wasn’t the question that was asked you.

The question was asked you whether or not you thought it

was an economic necessity. I f you didn’t understand the

question, I will ask it again. Do you think from an eco

nomic standpoint, from the standpoint of the financial

—4 1 5 -

affairs, earnings and what-not of these families, that it

is necessary! A. No, sir, I do not.

Q. Who is going to pick the cotton for them! A. Well,

the parents can pick the cotton, or either mechanical

pickers.

Q. Most of these families that we are talking about

can’t hire mechanical pickers to come in there and pick

their cotton! A. Yes, sir, it’s cheaper than hand picking.

Q. So you think that these sharecroppers on these little

farms would be able to hire somebody to come in there

with a cotton picker to pick their cotton! A. I do so,

and if it’s too small, the parents can harvest it them

selves.

Q. Do you know anything about cotton picking! A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Can you utilize those big machines on these little

farms that we are talking about! A. Well, I see them

on small farms.

Q. Is there any limitation so far as the terrain is

concerned! Can they use those machines in hilly fields

as well as flat, or is there any problem there! A. Well,

- 4 1 6 -

due to the weather you cannot pick cotton neither way.

Q. How many children would you say we have in Madi

son County whose children pick cotton at harvest time!

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

29a

A. Well, I would say about—approximately, I guess, about

fifty percent.

Q. Of the families? A. Yes.

Q. Well, would you give us an estimate of the number

of families, so that fifty percent will mean more to the

Court? A. The number of families—I don’t believe I

could give that.

Q. Well, you don’t have any rough idea as to the number

of families that would be involved? A. No, sir, I do not.

Q. But you think about half of the negro farm families

do have their children pick cotton at harvest time? A.

Yes.

Q. Now, you have three children, I believe you said?

A. I have four; but three in the Madison County School

System.

—417—

Q. And where did you say they were going to school?

A. One will be going to North Side.

Q. That’s a formerly white high school, is it not? A.

That’s right. And the other two will be going to Hunters

ville.

Q. That is also a formerly white elementary school?

A. That’s right.

Q. Now, your fourth child, is he or she not of school

ag’e? A. She is school age, but she goes to college.

Q. So that all three of your children are going to for

merly white schools? A. That’s right.

Q. Now, when you enrolled those children in those

schools, you knew that they had a white faculty, did you

not?

Glynn. White—-for Plaintiffs—Cross

Mr. Williams: That’s objected to, if Your Honor

please; that has no probative value whatsoever.

30a

The Court: It does have probative value. It’s for

the Court to say how much weight to give it.

—418—

Mr. Williams: Well, I further object on the ground

it is incompetent and irrelevant.

The Court: He has testified that negro parents

are reluctant to send their children to a school that

has an all-white faculty. Now, it is certainly relevant

on cross-examination for counsel for the School

Board to ask him if he didn’t do exactly that, and

why he did it.

Mr. Williams: I submit it is not relevant, because

defendants admit and stipulate that they are oper

ating the school system with all white and all negro

faculties.

The Court: Objection overruled.

By Mr. Manhein:

Q. You knew when you had your children enrolled at

their respective schools, that both those schools had all-

white faculties, did you not? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Well, now, that didn’t deter you, or make you reluctant

to send your children to those schools, did it? A. No, it

did not.

Q. In fact, it rather encouraged you to send them to

—419—

those schools? A. Well, I just prefer sending them there.

Q. You thought they would get a better education, or

what was your reason? A. Not that the white teacher

know any more than colored teacher, but since it was in a

segregated system, I knew that the Board did not give

equal facilities as they did in the colored schools.

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Cross

31a

Q. You mean physical things like the school building

and the equipment and that sort of thing? A. That’s

right.

Q. Well, in any event, you did not hesitate to send

your children to schools where they had all-white faculties

—that didn’t bother you at all? A. No, it did not.

Mr. Manhein: That is all.

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Redirect

Redirect Examination by Mr. Williams:

Q. Mr. White, I believe when you joined in this lawsuit,

you knew that in the complaint we were asking for mixed

faculties in the schools, did you not? A. I did so.

—420—

Q. And, in spite of the fact that you sent your child, your

children to schools with all-white faculties, I believe you

testified that you felt your child could get a better educa

tion with mixed faculties, is that correct? A. That’s right.

The Court: Why do you say that, Mr. White?

The Witness: Because, as I stated, Judge, Your

Honor, as they grow up, they have better communi

cation—

The Court: How do you mean better communica

tion?

The Witness: I mean socializing together, the

white teachers and the negro teachers.

The Court: We are not talking about the effect on

the teachers. We are talking about the effect on the

school children. Now, you said your children before

this lawsuit had gone to all-negro schools, negro

students and faculty, and then after this Court en

32a

tered the order, your children went to a white school.

Now, is it your contention that your kids would not

get just as good an education where the faculty was

all-white, as they would where you had part white

—421—

and part negro faculty?

The Witness: That’s not my intent. But I do feel

like they would get just as much education, and then

they would have the experience of being among the

white and negro teachers.

The Court: All right.

Mr. Williams: If Your Honor please, in light of

that answer that has just been given, I would like

to ask this:

Q. How far did you go in school? A. Through the

twelfth grade.

Q. And that was in the Madison County School System?

A. That’s right.

Q. In the segregated negro portion of the Madison

County School System, is that right? A. Yes.

Q. You are not a college educated man, are you? A. No.

Q. And by occupation, you are a farmer? A. That’s

right.

Mr. Williams: That is all.

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs—Recross

—422—

Recross Examination by Mr. Manhein:

Q. I think he answered this question, Your Honor, and

I am not quite sure—did you say you thought they would

get just as good an education in an all-white faculty as they

33a

would if the faculty were integrated? A. Well, I think I

did say that.

Mr. Manhein: That is all.

Glynn White—for Plaintiffs— Redirect—Recross

Redirect Examination by Mr. Williams:

Q. State what you meant by that, Mr. White? A. In

the previous all-white school, where they have more litera

ture and better literature, I presume that they have a

chance of getting more than they would get in the previous

all-negro schools, because in a segregated system the previ

ous negro schools do not have all that the previous white

schools has.

Q. And does this remain true, even though the negro

schools are allegedly—even though they now say the negro

schools are desegregated, are they still just like they were

before, all negro faculties and still the same discrepancy,

difference that you are talking about in the literature and

the facilities? A. Yes, sir.

—423—

Mr. Williams: I believe that is all.

Recross Examination by Mr. Manhein:

Q. You don’t really know whether there is any difference

in the school books and literature in the schools, do you?

A. I think it is some difference.

Q. Well, can you give us some concrete example?

Mr. Williams: May it please the Court, I respect

fully refer counsel to the language that this gentle-

34a

man is using, having just admitted that he is a gradu

ate of their negro high school up there.

The Court: Are you making an objection?

Mr. Williams: Yes, sir, I am objecting.

The Court: To this question on its relevance?

Mr. Williams: I am objecting, if Your Honor

please—no, I will withdraw my objection.

—424—

By Mr. Manhein:

Q. Well, can you give us some concrete example of what

you are saying? I am not talking about when you were in

school twenty years ago, but at the present time, any dif

ference in the literature, books, curriculum? A. I think

the American History is different.

Q. Where? A. In the negro schools and the previous

white schools.

Q. Different in what way? A. It is not the same book as

I saw my daughter bring home.

Q. What grade was your daughter in at that time? A.

The seventh grade.

Q. And she brought one American History book home

when she was in the seventh grade that somehow is different

from some other American History book that she brought

home? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And is that what you are basing this on? A. That’s

the onliest thing I have to go on, because it was different.

Q. What grade was she in when she brought the other

American History book home? A. She was in the sixth

- 4 2 5 -

grade at that time.

Q. And when she was in the sixth grade she went to what

school? A. To Denmark School.

Glynn White—-for Plaintiffs—Recross

35a,

Q. And she brought a certain type of American History

book home in the sixth grade? A. Yes.

Q. Did they teach American History in the sixth grade?

A. Well, she told me it was American History.

Q. You really don’t know that there is any difference?

You are kind of guessing about that? A. I may not be

giving it exactly, but it is some difference.

Mr. Manhein: All right.

Mr. Williams: That is all.

The Court: Step down, Mr. White.

(Witness excused.)

Nathaniel Benson,—for Plaintiffs—Direct

The Court: Call your next witness.

Mr. Williams: Call Mr. Benson.

—426—

Nathaniel Benson, the said witness, having been first

duly sworn, testified as fo llow s:

Direct Examination by Mr. Williams:

Q. State your name, age and address. A. Nathaniel

Benson. My age is forty-three.

Q. Where do you live? A. Route 5, Jackson.

Q. How long have you lived there? A. Practically all

my life ; ever since I was about nine years old.

Q. That’s Madison County, Tennessee? A. Right.

Q. What is your occupation? A. Well, I am a farmer

and am in the taxi business.

Q. How far did you go in school? A. Seventh grade.

Q. And was that in the segregated schools of Madison

County, Tennessee? A. Right.

36a

Q. When did you finish the seventh grade? A. I can’t

—4 2 7 -

recall right now when I finished.

The Court: Speak up so everybody can hear you.

The Witness: I can’t recall the year that I finished

in, because, if it please the Court, I would like to

say, while I am thinking of it, the reason I didn’t

go any higher is on account of the harvest of the

white man’s cotton. It wasn’t ours. It was the white

man’s cotton, but we didn’t get anything out of it.

I am forty-three years old, and I don’t want my kids

to come up like I did.

By Mr. Williams:

Q. Your folks were tenant farmers and you worked on

a white man’s farm? A. Yes.

Q. And they let you out at the harvest time, a split sea

son—how many years ago was that? Has it been twenty

or twenty-five or thirty years? A. It was about thirty-

three years ago, I would say.

Q. And they let you out in split seasons, so that you could

harvest this cotton for the white man? A. That’s right.

—428—

Q. And that’s the reason that you didn’t go any further

in school? A. That’s right,

Q. Are there any large numbers of negroes up there in

Madison County who benefit, who have to have this split

season thing in order to live, in order to live and make out?

A. Don’t have to.

Q. Sir? A. We don’t have to. Just like I said, I have

been in the cab business, and have been all over Madison

County, and I see what is happening, and out on my road

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—Direct

37a

there is ten miles through which we don’t have but just

one sharecropper. I notice a while back that somebody said

that ninety-five percent of the negro people was farmers.

Q. You say ninety-five? A. He said they was share

croppers. But you don’t have that—you don’t have ninety-

five percent of the negro people sharing. On my road there

is ten miles through which we don’t have but one.

Q. Is he working for himself or working for the white

man? A. He is sharecropping, working for a white man.

—429—

Q. These sharecroppers that work for these white men

and deprive their children of an education like this, what

is their average annual income? What do they, themselves,

get out of this? A. It’s working sharecropping or work

ing by the day.

Q. Do they do it both ways? A. Both ways. People

used to sharecrop and work by the day on my road and

some other roads, and they would get four dollars a day.

A person can’t make it now on four dollars a day.

Q. How much do they give them for the children that

work? A. The children, they don’t hire them, because they

say they are too small.

Q. So, what happens, then, in effect, that they pay the

negro four dollars for a day’s labor, and instead of doing

it himself, he is given the opportunity to use his children—

Mr. Manhein: Object to the leading.

The Court: I believe you are leading.

Mr. Williams: I was just trying to speed things

—430—

along.

The Court: Well, that is all right. We won’t ride

herd on you too much, but you can’t put the answers

in his mouth.

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—Direct

38a

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—Direct

By Mr. Williams:

Q. But that was the situation? A. If Your Honor please,

if you will let my opinion on that—

The Court: Now, let me say this: We are talking

about the split season, and maybe to save a little

time, the Court ought to set a few ground rules.

We understand the law. The School Board has no

obligation to abolish the split season unless it is

shown that it is being maintained in order to per

petuate segregation. In support of its contention

that that is not the reason for it, the School Board

contends that as a matter of fact a great number

of these negro children do pick cotton, and, further,

that that’s an economic necessity for them, and their

parents, and in support of the contention that it is

- 4 3 1 -

being maintained in order to perpetuate segrega

tion, the plaintiffs are seeking to show that there

is no economic necessity for it and that’s the only

reason, to perpetuate segregation. Now, let’s try

to keep our proof on that issue, not what different

people may think about it, its general wisdom or

the fact that it’s part of the system which is eco

nomically wrong because this Court, as we said in a

prior opinion, cannot reorganize the economy of

Madison County as part of the school desegregation

case.

I might say here also that the School Board has

stipulated that educationally it is not desirable, but

I think Mr. Williams will recognize that even though

it is educationally not desirable, this Court cannot

order it abolished for that reason. The only basis

39a

on which the Court could do something about it is

on the basis that it was perpetuating segregation.

I also took occasion to say in the last opinion I wrote

in this case that if it is true, as plaintiffs contend,

—432—

that it is unpopular with the vast majority of ne

groes in Madison County and that they don’t want

it, it would seem to the Court that under this plan

of desegregation that has been approved there, that

would create a very strong motive on the part of the

negroes to choose to go to the heretofore white

schools; so in that sense, if it was unpopular, it

wouldn’t tend to perpetuate segregation, and now

I wish you gentlemen would keep your questions

related to the point as to its economic necessity,

because that indirectly goes to the question of

whether or not it is being maintained to perpetuate

segregation.

Mr. Williams: I would like to state for the record

that the plaintiffs are here offering proof on this

question of economic necessity under protest ac

tually, because the plaintiffs, Your Honor, may recall

in the pre-trial conference and throughout this case,

have maintained that the fact of the differentiation

as between the negro and the white school is un

constitutional.

The Court: All right, sir.

—433—

By Mr. Williams:

Q. Now, Mr. Benson, how many children do you have!

A. Four.

Q. How man are enrolled in the schools in Madison

County! A. Three.

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—-Direct

40a

Q. What schools are they in? A. One is in Browns,

and the other in East High, and I enrolled one of them in

North side this year.

The Court: Give me that again, Mr. Benson.

The Witness: One of them is in Browns Elemen

tary School.

The Court: Is that a heretofore white school?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: And where are the others ?

The Witness: North Side High School and East

High.

The Court: Is that a heretofore white school?

The Witness: A negro school.

The Court: Go ahead, Mr. Williams.

—434—

By Mr. Williams:

Q. Now, Mr. Benson, why are these children attending

these three different schools, especially why are the two

high school children attending different schools, one at

tending a formerly white and one a formerly negro?

A. Well, the one is attending the negro school on account

of the mother. Her mother wanted her to go there. I

really wanted her to go to North Side, because they have

better everything, I would say. They have better books.

They have more books. I was out there to a PTA meeting

two or three years ago, if it please the Court, and they

had the meeting in the library. The library that they

had, which I am not educated—I got my books at my house,

and they have in East High School, and I gets around

quite a bit since my kids have been in school, and I have

been to some of these white schools, and they have a lot

of books. They have so many books. Some of the places

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—Direct

41a

the books is stacked on the tables out in the library. I

have seen that, which I don’t guess nobody knows I was

looking, but that’s why I wrant to go there, because they

can get more education, because I didn’t get it, and I am

pushing to try to make them get some of it, make the

—4 3 5 -

white man pay them for the work that I have did; that’s

what I am trying to do.

Q. Now, Mr. Benson, do you feel like your children will

get a better education? A. They will.

Q. Now, let me ask you about faculties, teachers and

principals. Do you feel like it is better for the teachers

and principals to be mixed within a school, or for them

all to be all-white teachers ? A. I feel like it is better for

them to be mixed, because you have better teachers. There

are teachers that are not qualified now, and they will go

back to school and get what they needs to teach their kids.

I feel like it is better for them to be mixed. I feel like the

whole entire thing is now ready to be mixed, all faculties.

Q. Do you feel like the schools that have been all-negro

should have some white faces in there somewhere? A.

That’s right; both for teachers and for students.

Q. Why do you feel like that? A. I feel like it would be

better for the people, better for the faculty and better for

the students.

—436—

Q. Is everybody up there in Madison County an Ameri

can citizen? A. Right.

Mr. Manhein: If Your Honor please, this is ir

relevant.

Mr. Williams: I don’t know, if Your Honor please.

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—Direct

42a

The Court: Let me ask you this: You know we

have a limited amount of time today, and you have

another motion this afternoon. You know this Court

knows that everybody in Madison County is an

American citizen.

Mr. Williams: But I am asking him if he feels

like that has something to do with his feeling. I

know counsel wants to object to this, but this public

supported School Board is the one forcing us to put

a seventh-grade educated plaintiff on—

The Court: Mr. Williams, you are not going to

ask irrelevant questions, and your last question was

irrelevant. Now, what we are trying to get at is the

—4 3 7 -

question as to whether or not this segregation of

faculties is preventing the abolition of discrimina

tion. In other words, more specifically, is it prevent

ing negro parents from choosing to go to white

schools; that is what we are basically interested in,

and if we don’t stick pretty close to that, we will

never get through.

Mr. Williams: May it please the Court, I submit

that’s not the only point about segregated faculties.

It affects the education.

The Court: But the point is, Mr. Williams, that

this Court is not and cannot take over all the educa

tional policies of the Board. We are not sitting in

judgment of whether this educational policy is good

or bad, except to the extent that it prevents the

abolition of discrimination. Now, if it were true that

the fact that you had an all-white faculty makes for

a poorer education in the schools, and if that creates

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—Direct

43a

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—Direct

a deterrence on the part of the negro parents not

to send their children to the white schools because of

that educational factor, it would come into play that

—4 3 8 -

way, but we are not sitting in judgment of the edu

cational policies per se.

Mr. Williams: I am not trying to establish that,

if Your Honor please. All I am showing is—if Your

Honor please, I will try to direct my questions along

—I want to state for the record, if Your Honor

please, that it is our contention, first, with regard to

this question, that the Supreme Court held in the

Brown case that segregation in education is uncon

stitutional. We feel that that decision, and we insist

that that decision encompassed a holding that that

included segregation in all aspects of the school

system.

The Court: We understand that’s your contention

about what the constitutional law is.

Mr. Williams: Now, if Your Honor please, the

Court, as we understand it, indicated in the pre-trial

conference that it would be incumbent on us here

to introduce some proof with regard to this teacher

desegregation question. We do not intend to aban

don our position that the Supreme Court has held

—439—

that segregation in and of itself in education violates

the constitution. We intend further to show, how

ever, that segregation in this particular aspect as

well as all other aspects of the school system has

an impact on the education of a child, not only by

way of a deterrent from selecting a particular school

44a

in a choice plan system, but also in other ways, as

has been mentioned by the plaintiff, Mr. White.

The Court: All right, let’s get around to ques

tioning this witness. We understand your position.

Mr. Williams: All right, sir.

Q. Do you feel that continued segregation of the fac

ulties in the school has any tendency to keep the negro

school designated, known as a negro school and a white

school known as a white school? A. Repeat that. I didn’t

quite understand it.

Q. Do you feel that the fact that you have white teachers

only at white schools and negro teachers only at negro

schools tends to keep those schools known as negro and

white schools in the community? A. I really don’t think

—440—

it would help Madison County if you keep them like they

are now.

Q. Well, explain why you don’t think it would help

Madison County? A. Well, I just explained it a while

ago. I believe it would be better for them to integrate now

as a school than stay a negro and white school.

Q. Do you still call schools up there in Madison County

negro and white schools? A. Well, as far as I know, they

call them.

Q. Are all the schools that used to be negro schools still

known as negro schools? A. Yes. There is not a white

kid in them, and not a white teacher in them that I knows

anything about.

Q. Do you feel if they had white teachers in those schools

that they might begin to not be known as negro schools

and be known as Madison County schools? A. That’s

right.

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—Direct

45a

Q. Now, the white schools are schools that are sup

posedly desegregated. Do you still know them as white

schools, even though a few negro kids go there? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. Do you feel that it may help them—

—441—

Mr. Manhein: Objection again, on the ground he

is leading. He is leading the witness and making a

speech in the process.

Mr. Williams: All right. I will tone down my

voice.

Q. Mr. Benson, do you feel that the white schools would

stop being known as white schools and be known as Madi

son County schools if you had negro teachers assigned

there ? A. Bight.

Mr. Williams: You may cross-examine.

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiff's—Cross

Cross-Examination by Mr. Manhein:

Q. How many families, approximately, if you know, do

we have in Madison County—how many negro families do

we have, families whose children pick cotton during the

harvest season? A. Well, you will find a lot of them that

picks cotton in Madison County. I don’t know just how

many. As I said a while ago, speaking about ninety-five

percent of the negro people is farmers, but you don’t have

them now. I f you was in the business I was in, you could

find out those people is not farming now—most of them do

—4 4 2 -

public work.

46a

Q. Could you give us any estimate as to the percent!

A. I would say you have about twenty percent.

Q. About twenty percent of the negro people farming?

A. And you have about that many of whites that are

farmers around.

Q. Well, I believe you don’t understand my question.

Could you tell me about what percent of the negro farm

families that we have in Madison County, about how

many— A. All total?

Q. No. What percent use their children to pick cotton?

Would it be as many as half of them? A. No, it wouldn’t

be half. You would have about ten percent of them.

Q. And do you have any idea as to how many negro farm

families we have in Madison County? A. Are you speak

ing of the land owners or sharecroppers or renters, or who ?

Q. Both. A. All total?

Q. Yes. A. About twenty percent of them.

—443—

The Court: You say only twenty percent of the

negro families in Madison County out of Jackson

are making their living farming?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: What are the rest of them doing?

The Witness: They works in town at plants and

things that are coming in. They haven’t never got

anything off the farm nohow, the sharecroppers

haven’t.

By Mr. Manhein:

Q. Now, what community do you live in? A. Denmark

community.

Q. And what is the closest former negro school to you?

A. Tri-Community School.

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs-—-Cross

47a

Nathaniel Benson—for Plaintiffs—Cross

Q. Do you have any idea how many negro farm families

you have out there at the Tri-Community School? I am not

talking about families who earn a living in town, but

families who earn their living—well, farmers, share

croppers or land owners? A. On my road?

Q. Well, in that Tri-Community area there, whose chil

dren go to Tri-Community School? A. We have about

- 4 4 4 -

five.

Q. Five what? A. Five families is farming on that

road; that don’t work in town.

Q. I am not talking about on the road. What I am trying

to get at, and I am anxious for you to understand the ques

tion, if I can make it clear. About how many negro farm

families do we have whose children attend the Tri-Com

munity School, if you know? A. Oh, I don’t know how

many families attending that school, Tri-Community

School. I wouldn’t have the slightest idea.

Q. Well, could you give any estimate?

Mr. Williams: I object, if Your Honor please. He

said he doesn’t know.

The Court: Objection sustained.

By Mr. Manhein:

Q. Two of your children are in white schools. The fact

that they had in those schools all-white faculties didn’t deter

you from sending your children to those schools, did it ? A.

No, it didn’t.

—445—

Q. It didn’t bother you at all? A. No. But, as I stated

a while ago, I think it would be better, though, for the

entire school to be integrated.

48a

Q. Now, let me ask you this question: Do you think that

your children will get just as good an education with

the all-white faculty as they would if they had a mixed