Letter from Tegeler to Court RE: Plaintiff Inclusion on Final List

Correspondence

September 30, 1992

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Letter from Tegeler to Court RE: Plaintiff Inclusion on Final List, 1992. 6781b3c9-a546-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ae0502e3-2117-443a-9055-b1906a849347/letter-from-tegeler-to-court-re-plaintiff-inclusion-on-final-list. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Maria ny -®

CAV '

FOUNDATION

ThirtyTwo Grand Street, Hartford, CT 06106

203/247-9823 Fax 203/728-0287

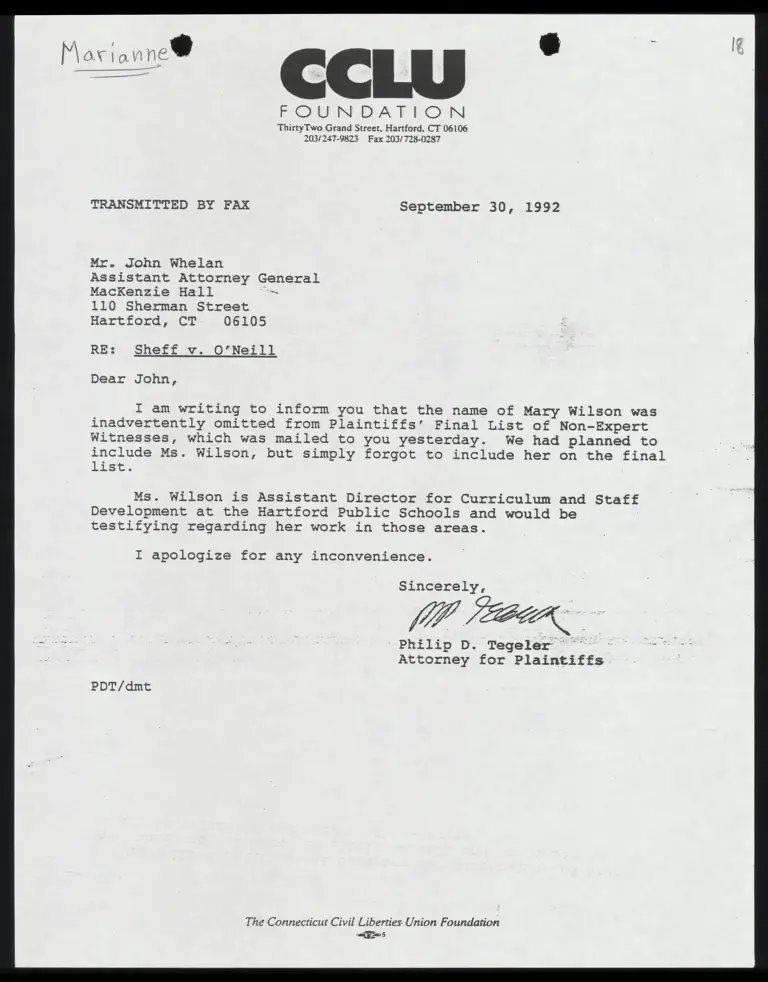

TRANSMITTED BY FAX September 30, 1992

Mr. John Whelan

Assistant Attorney General

MacKenzie Hall Be

110 Sherman Street

Hartford, CT 06105

RE: Sheff wv. O'Neill

Dear John,

I am writing to inform you that the name of Mary Wilson was

inadvertently omitted from Plaintiffs’ Final List of Non-Expert

Witnesses, which was mailed to you yesterday. We had planned to

include Ms. Wilson, but simply forgot to include her on the final

list.

Ms. Wilson is Assistant Director for Curriculum and Staff

Development at the Hartford Public Schools and would be

testifying regarding her work in those areas.

I apologize for any inconvenience.

Sincerely,

Philip D. Tegeler =~

Attorney for Plaintiffs

PDT/dmt

The Connecticut Civil Liberties: Union Foundation

wis