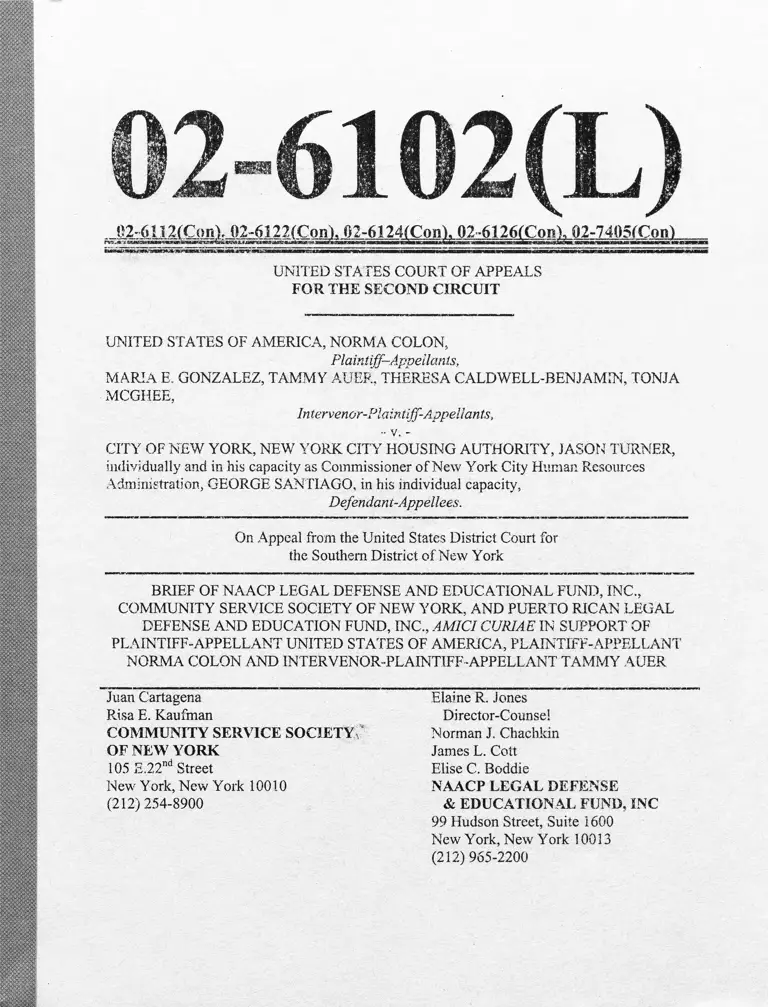

United States v. City of New York, NY Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant

Public Court Documents

September 27, 2002

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. City of New York, NY Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant, 2002. 9fee2af3-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ae06dc70-b617-45ff-9c69-5fa0696e175e/united-states-v-city-of-new-york-ny-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-plaintiff-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, NORMA COLON,

Plaintiff-Appellants,

MARIA E. GONZALEZ, TAMMY AUER, THERESA CALDWELL-BENJAMIN, TONJA

MCGHEE,

Intervenor-Plaintiff Appellants,

- v, -

CITY OF NEW YORK, NEW YORK CITY HOUSING AUTHORITY, JASON TURNER,

individually and in his capacity as Commissioner of New York City Human Resources

Administration,-GEORGE SANTIAGO, in his individual capacity,

Defendant-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Southern District of New York

BRIEF OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

COMMUNITY SERVICE SOCIETY OF NEW YORK, AND PUERTO RICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC., AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF

PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT

NORMA COLON AND INTERVENOR-PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT TAMMY AUER

Juan Cartagena

Risa E. Kaufman

COMMUNITY SERVICE SOCIETY

OF NEW YORK

105 E.22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

(212) 254-8900

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

James L. Cott

Elise C. Boddie

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

& EDUCATION AL FUND, INC

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................................ ii

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT.......................................... viii

STATEMENTS OF INTEREST......... ............................................................1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...................................................................... 3

ARGUMENT.................. 5

I. NEW YORK CITY WEP WORKERS REINFORCE THE WORK

PERFORMED BY CITY EMPLOYEES AND OFTEN SUPPLANT

CITY EMPLOYEES ALTOGETHER.................................................... ...5

II. DENYING WEP WORKERS TITLE VII PROTECTION

AGAINST DISCRIMINATORY TREATMENT EXACERBATES THE

ALREADY DAUNTING BARRIERS THEY FACE IN ACHIEVING

SELF-SUFFICIENCY..................................... 9

III. THE DISTRICT COURT’S RULING SUBVERTS THE

PURPOSE OF TITLE VII.........................................................................14

A. Applying Title VII protections to the WEP workers in this case is

consistent with the statute’s purpose of eliminating discrimination in the

workplace and the broad interpretation courts have given Title VII.....14

B. The district court’s ruling contravenes the purpose of Title VII by

failing to account for plaintiffs’ actual work experience - as pled in

their complaints - and instead focusing on artificial criteria to define the

plaintiffs’ employment status................................ ............................ 19

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT’S RULING, IF NOT OVERTURNED,

WOULD CREATE A SUB-CLASS OF MOSTLY AFRICAN-

AMERICAN AND LATINO WORKERS WHO ARE UNPROTECTED

BY FEDERAL CIVIL RIGHTS LAWS BARRING EMPLOYMENT

DISCRIMINATION ON THE BASIS OF RACE, SEX, OR NATIONAL

ORIGIN AND PROHIBITING SEXUAL HARASSMENT....................25

CONCLUSION......... ................................................................................... 30

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE.....................................................................32

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975)..................................................................................16

Alexander v. Sandoval,

532 U.S. 275 (2001)..................................................................................26

Annis v. County o f Westchester,

36 F.3d 251 (2d Cir. 1994)...................................................................... 27

Armbruster v. Quinn,

711 F.2d 1332 (6th Cir. 1983)...................................................................17

Ass ’n Against Discrimination in Employment, Inc. v. City o f Bridgeport,

647 F.2d 256 (2d Cir. 1981).....................................................................26

Cook v. Arrowsmith Shelburne, Inc.,

69 F.3d 1235 (2d Cir. 1995).............................................. ................ 22, 23

County o f Washington v. Gunther,

452 U.S. 161 (1981)..................................................................................17

Davidson v. Capuano,

792 F.2d 275 (2d Cir. 1986).....................................................................28

Diana v. Schlosser,

20 F. Supp. 2d 348 (D. Conn. 1998).........................................................21

Fadeyi v. Planned Parenthood Ass ’n o f Lubbock, Inc.,

160 F.3d 1048 (5th Cir. 1998)............. ...... .............................................. 24

Gomez v. Alexian Bros. Hosp.,

698 F.2d 1019 (9th Cir. 1983)...................................................................21

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971)............................................................................16, 26

Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc.,

510 U.S. 17 (1993).................................................................................. ..12

Int’IBhd. o f Teamsters v. U.S.,

431 U.S. 324(1977)...................................................................................17

Jin v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co.,

295 F.3d 335 (2d Cir. 2002)......................................................................11

ii

Johnson v. Transportation Agency,

480 U.S. 616(1987)................................................................................... 16

King v. Chrysler Corp.,

812 F. Supp. 151 (E.D. Mo. 1993)................................ .......................... 21

Lauture v. IBM Corp.,

216 F.3d 258 (2d Cir. 2000).....................................................................24

Los Angeles Dept, o f Water and Power v. Manhart,

435 U.S. 707 (1978)...................................................................................23

McDonald v. Santa Fe Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976)...................................................................................23

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973)...................... 17

McKennon v. Nashville Banner Pub. Co.,

513 U.S. 352 (1995)...................................................................................16

Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson,

477 U.S. 57 (1986).................................................................................... 23

Moldand v. Bil-Mar Foods,

994 F. Supp. 1061 (N.D. Iowa 1998).......................................................21

O ’Connor v. Davis,

126 F.3d 112 (2d Cir. 1997)........................ ............................................ 19

Pelech v. Klaff-Joss, L.P.,

815 F. Supp. 260 (N.D. 111. 1993)................. ........................................... 21

Pullman-Standard v. Swint,

456 U.S. 273 (1982)...................................................................................16

Robinson v. Shell Oil Co.,

519 U.S. 337 (1997).................................................................................. 23

Rogers v. EEOC,

454 F.2d 234 (5th Cir. 1971).....................................................................18

Sherman v. Burke Contracting, Inc.,

891 F.2d 1527 (11th Cir. 1990),

cert, denied, 498 U.S. 943 (1990).................................................. .......... 21

Sibley Memorial Hospital v. Wilson,

488 F.2d 1338 (D.C. Cir. 1973)..........................................................17, 20

iii

Spirt v. Teachers Ins. & Annuity Ass ’n,

691 F.2d 1054 (2d Cir. 1982),

vacated on other grounds, 463 U.S. 1223 (1983).............................. 21, 22

Trevino v. Celanese Corp.,

701 F.2d 397 (5th Cir. 1983).....................................................................23

United Steelworkers v. Weber,

443 U.S. 193 (1979)................................................................................... 16

Vanguard Justice Society, Inc. v. Hughes,

471 F. Supp. 670 (D. Md. 1979)......................................... ..................... 22

Statutes

42 U.S.C. § 1983.................................................... 27

42 U.S.C. § 602(a)(l)(A)(i)........................................................................... 18

42 U.S.C. §603(a)(5)(I)(iii)...........................................................................27

42 U.S.C. §603(a)(5)(I)(iv)...........................................................................27

42 U.S.C. §608(d)......................................................................................... 25

Age Discrimination Act of 1975,

42 U.S.C. §6101 etseq...................................................................... 25

New York Social Services Law Sec 331(3)................................ ................ 28

NYCPLR §7801 etseq..................................................................................28

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity

Reconciliation Act (“PRWORA”),

Pub. L. No. 104-93, 110 Stat. 2105 (1996)..............................................25

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973,

29 U.S.C. §794.......................................................................................... 25

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990,

42 U.S.C. §12101 etseq............................................................................ 26

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §2000d etseq............................................................................ 26

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §§2000e etseq. (2001)........ passim

IV

Regulations

12NYCCR Sec. 1300.11(b)..........................................................................28

12NYCCR Sec. 1300.11(b)(6).....................................................................28

Treatises

Merrick T. Rossein,

Employment Discrimination Law and Litigation §1-4 (2001).................15

Other Authorities

Andrew Bush, Swati Desai, and Lawrence Meade,

Leaving Welfare: Findings from a Survey o f Former

New York City Welfare Recipients (New York City Human Resources

Administration Working Paper 98-01, 1998)............................................ 13

Building a Ladder to Jobs and Higher Wages:

a Report by the Working Group on New York City’s

Low-Wage Labor Market (Oct. 2000).................................................... 13

Citizens’ Committee for Children,

Child Care: The Family Life Issue in New York City (2000)...................13

Community Voices Heard,

WEP Workers Work Experience Program:

New York City ’s Public Sector Sweat Shop Economy (2000)..............6, 10

Developments in the Law - Employment Discrimination

and Title VII o f the Civil Rights Act o f1964,

84 Harv. L. Rev. 1109(1971)....................................................................15

Heather Boushey, Economic Policy Institute,

Staying Employed After Welfare: Work Supports and Job Quality Vital to

Employment Tenure and Wage Growth (June 2002)............................. 13

Human Resources Administration,

NYC Public Assistance Fact Sheet (available at

http://www.nyc.gov/html/hra/pdf/hrafact_Oct 2001.pdf).........................25

National Partnership for Women & Families,

Detours on the Road to Employment: Obstacles Facing Low-Income

Women (1999).........................................................................................-10

Office of the State Comptroller, State of New York,

Report 99-J-l, Welfare Reform: Assessing Educational and Training

Needs o f Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Recipients (2000)... 10

Pamela Loprest,

Who Returns to Welfare

(The Urban Institute Series B, No. B-49, 2002).......................................14

Rebecca Gordon, Applied Research Center,

Cruel and Usual: How Welfare ‘Reform ’ Punishes Poor People (2001). 11

Richard M. Tolman & Jody Rapheal,

A Review o f Research on Welfare and Domestic Violence (2000)

(available at www.ssw.umich.edu/trapped/pub.html)................... .......... 10

S. Rep. 867, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. (1964)................ .................................. 17

Sheila Zedlewski,

Work-Related Activities and Limitations o f Current Welfare Recipients

(Urban Institute Discussion Paper 99-06, July 1999)...............................10

The City of New York,

Fiscal Year 2000 Mayor’s Management Report (2000)............................7

The City of New York,

Fiscal Year 2001 Mayor’s Management Report (2001)............................7

The Rockefeller Institute of Government,

Leaving Welfare: Post-TANF Experiences o f New York State

Families (2002) (available at

www.rockinst.org/publications/federalism/

leaver_fmal_June_2002.pdf)............. ...................................................... 14

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights,

A New Paradigm for Welfare Reform: The Need for Civil Rights

Enforcement, August, 2002

(available at www.usccr.gov/pubs/prwora/welfare.htm).......................... 11

Use of Work Experience Program Participants

at the Department o f Parks and Recreation, Inside the Budget

(Independent Budget Office, New York, N.Y., Nov. 2000)......................7

Welfare Overhaul Proposals:

Hearing on Welfare Reauthorization Proposals Before Subcommittee on

Human Resources o f the House Committee on Ways and Means

107th Cong. (April 11, 2002) (statement of Jason A. Turner,

Director for Self-Sufficiency, Milwaukee, Wise.)...................................5

VI

http://www.rockinst.org/publications/federalism/

Welfare Overhaul Proposals:

Hearing on Welfare Reauthorization Proposals Before Subcommittee on

Human Resources o f the House Committee on Ways and Means,

107th Cong. (April 11, 2002) (statement of Lee Saunders,

Executive Assistant to the President, American Federation

of State, County, and Municipal Employees (“AFSCME”), and

Administrator, AFSCME District Council 37, New York)........................8

vii

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure,

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

COMMUNITY SERVICE SOCIETY OF NEW YORK, and PUERTO

RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC., amici curiae

herein, through the undersigned counsel, make the following disclosures:

Amici, all not-for-profit corporations of the State of New York, are

neither subsidiaries nor affiliates of a publicly-owned corporation.

Risa J b . j^aurman, nsq,

COMMUNITY SERVICE

SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

105 E. 22nd St.

New York, NY 10010

VIII

STATEMENTS OF INTEREST

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (“LDF”) is a

non-profit corporation established under the laws of the State of New York.

It was formed to assist black persons in securing their constitutional rights

through the prosecution of lawsuits and to provide legal services to black

persons suffering injustice by reason of racial discrimination. For six

decades, LDF attorneys have represented parties in litigation before the

United States Supreme Court and the lower federal courts involving race

discrimination and particularly discrimination in employment. LDF believes

that its experience in, and knowledge gained from, such litigation will assist

the Court in this case.

Community Service Society of New York

For more than 150 years, the Community Service Society of New

York (“CSS”) has been leading the fight against poverty in New York City.

CSS focuses on the deeper-seated problems that prevent people from

permanently moving out of poverty, combining research, advocacy, direct

service, volunteerism, community organizing and litigation to address issues

related to housing, income security, education, health, and community

i

development. Since 1987, CSS’s Department of Legal Counsel has helped

fulfill the promise that the law should serve all people and has played an

essential role in the organization’s fight against poverty by participating as

direct counsel and amicus curiae in cases involving barriers faced by low-

income New Yorkers.

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.

The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.

(“PRLDEF”) is a national non-profit civil rights organization founded in

1972. It seeks to ensure the equal protection of the laws to protect the civil

rights of Puerto Ricans and other Latinos through litigation and policy

advocacy. Since its inception, PRLDEF has participated both as direct

counsel and as amicus curiae in numerous cases throughout the country

concerning the proper interpretation of the civil rights laws.

2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT*

In New York City, workers participating in the City’s Work

Experience Program (“WEP”) face daunting roadblocks to economic self-

sufficiency. The complainants in the cases below painted a grim picture of

the hostile and sexually harassing environments in which they were

compelled to work in order not to lose their benefits. Although these

workers consistently perform the same or similar jobs as those performed by

other city workers — so much so that the City appears to have reduced its

workforce in reliance on their labor - the district court below found that

they were not “employees” and, therefore, unprotected by Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq. (2001) (“Title VII”).

The district court’s ruling perpetrates a gross injustice on WEP

workers. If not reversed by this Court, the district court’s decision would

create a sub-class of predominantly African-American and Latino workers,

completely unprotected by federal civil rights laws barring employment

discrimination on the basis of race, gender, and national origin and

prohibiting sexual harassment. This plainly contravenes Title VII’s purpose

of eliminating discrimination in the workplace and the broad interpretation

courts consistently have given Title VII to effectuate that purpose. By

This brief is filed with the consent of all parties to these consolidated

appeals.

3

denying these workers the same legal protection against discriminatory and

harassing conduct afforded others -- who perform the same or similar work

in the same workplace — the district court’s decision further ostracizes a

minority population already living on the social and economic margins. The

consequences of the court’s ruling are particularly acute given that WEP

workers have extremely limited options in the labor market and, without

legal recourse, may be trapped in a discriminatory, harassing, and abusive

environment.

4

ARGUMENT

I. NEW YORK CITY WEP WORKERS REINFORCE THE WORK

PERFORMED BY CITY EMPLOYEES AND OFTEN SUPPLANT CITY

EMPLOYEES ALTOGETHER

WEP workers comprise a critical sector of the City’s workforce,

supplementing and often supplanting City employees. The City extols the

virtue of the WEP program as a simulated work environment for WEP

workers. The Commissioner of New York City’s Human Resources

Administration during the administration of former Mayor Giuliani

described the goal of the workfare program as “genuine practice for private

employment.” Welfare Overhaul Proposals: Hearing on Welfare

Reauthorization Proposals Before Subcommittee on Human Resources o f the

x L

House Committee on Ways and Means 107 Cong. (April 11, 2002)

(statement of Jason A. Turner, Director for Self-Sufficiency, Milwaukee,

Wise.). Far from a simulation, however, the WEP program extracts real

work from WEP workers, who often do the same jobs and provide the same

valuable services as other city employees. The lower court’s denial of Title

VII protections thus enables the City to benefit from their labor while

avoiding its obligation to respect their civil rights — as it must respect the

rights of other city workers.

5

A survey of WEP workers in 1999 and 2000 conducted by

Community Voices Heard (“CVH”), an organization of individuals on

welfare and in workfare in New York City, found that “[w]hile the vast

majority of workfare participants perform entry-level jobs, many also do

more complex jobs with higher degrees of responsibility, including

supervising and training other workfare workers, opening and closing city

buildings and parks, and assisting the general public with community

problems.” Community Voices Heard, WEP Workers Work Experience

Program: New York City’s Public Sector Sweat Shop Economy 5 (2000).

The surveyors found that 86 percent of survey respondents in all categories

of workers reported that they performed the same work as municipal

employees at their WEP sites, id. at 6, with more than 90 percent of the

workfare workers in the Metropolitan Transit Authority reporting that they

performed the same work as transit employees. Id. at 14. The survey also

found that workfare workers provide janitorial and maintenance work in the

Department of Citywide Administrative Services, and clerical and office

work in a variety of City offices, including the Office of Employment

Services, neighborhood Jobs Centers, Department of Housing and

Preservation, and in borough buildings and schools. Id. at 8-9. WEP

6

workers also work in day care and senior care facilities throughout the City.

Id.

The City’s Independent Budget Office reported similarly that WEP

workers help maintain and clean the City’s parks, with 95 percent of WEP

workers performing tasks similar to the work done by the City’s park

workers and maintenance employees. Use o f Work Experience Program

Participants at the Department o f Parks and Recreation, Inside the Budget

(Independent Budget Office, New York, N.Y., Nov. 2000), at 1. The

Department of Parks and Recreation has “significantly augmented [its]

workforce, even as the number of full-time and seasonal employees has

declined.” Id. at 1-2.1

1 The Office of the Mayor attributes an increase in the City’s street

cleanliness ratings - from under 75 percent in 1996 to 86.7 percent in Fiscal

Year 2000 - to the labor of WEP workers within the Department of

Sanitation. The City of New York, Fiscal Year 2000 Mayor’s Management

Report 89 (2000). During the first four months of Fiscal 2001, WEP

workers at the Department of Transportation removed 8,247 cubic yards of

debris from the highways and removed stickers from 9,101 signs and poles.

The City of New York, Fiscal Year 2001 Mayor’s Management Report 89

(2001). The Independent Budget Office (“IBO”) notes that during a time

when the number of full-time employees at the City’s Department of Parks

and Recreation plummeted, the overall parks “acceptability rating” improved

from 57 percent in 1992 to 89 percent in 2000, an improvement that the IBO

noted was likely attributable to the increase in the number of WEP workers

at the Department. Use of Work Experience Program Participants at the

Department o f Parks and Recreation, Inside the Budget (Independent

Budget Office, New York, N.Y., Nov. 2000), at 1.

7

Indeed, at least one municipal union has charged that the workfare

program has resulted in the elimination of thousands of City jobs, as WEP

participants are substituted for City workers. Between December 1993 and

November 1998, the number of civilian employees declined by about 15,000

in City agencies, with most of those lost jobs in entry-level positions.

Welfare Overhaul Proposals: Hearing on Welfare Reauthorization

Proposals Before Subcommittee on Human Resources o f the House

Committee on Ways and Means, 107th Cong. (April 11, 2002) (statement of

Lee Saunders, Executive Assistant to the President, American Federation of

State, County, and Municipal Employees (“AFSCME”), and Administrator,

AFSCME District Council 37, New York). AFSCME estimates that the

WEP program caused the loss of 800 jobs in the Parks Department and

1,600 in the Human Resources Administration. Id. For example, AFSCME

documented an 85 percent staff reduction, from 136 to 24 custodial

assistants, in the City’s welfare offices, while hundreds of WEP workers

were assigned to clean the offices. Id.

8

II. DENYING WEP WORKERS TITLE VII PROTECTION AGAINST

DISCRIMINATORY TREATMENT EXACERBATES THE ALREADY

DAUNTING BARRIERS THEY FACE IN ACHIEVING SELF-

SUFFICIENCY

Their significant role in the City’s workforce notwithstanding, welfare

recipients face numerous obstacles to gaining economic self-sufficiency

through permanent, full-time employment. It would be highly ironic and

problematic to exacerbate these barriers by denying WEP workers the civil

rights protections that apply to other City workers, many of whom do the

same or similar work as WEP workers. The lower court’s exclusion of WEP

workers from Title VII protections threatens to create a sub-class of City

workers whose labor is repeatedly taken advantage of while their civil rights

are trammeled. Title VII protections for WEP workers are, therefore,

essential both to enable WEP workers to succeed and to prevent against the

exploitation of this vulnerable class of workers.

WEP workers face myriad barriers to finding permanent, full-time

employment. Using data based on a 1997 survey of individuals nationwide

receiving cash assistance, the Urban Institute found that welfare recipients

are inhibited in finding permanent private employment due to low education

levels (41 percent), lack of recent work experience (43 percent), need to care

for an infant or disabled child (19 percent), and either poor physical or poor

9

mental health (48 percent). Sheila Zedlewski, Work-Related Activities and

Limitations o f Current Welfare Recipients 8-10 (Urban Institute Discussion

Paper 99-06, July 1999). See also National Partnership for Women &

Families, Detours on the Road to Employment: Obstacles Facing Low-

Income Women 2 (1999) (welfare recipients identifying the following as

“often” or “very often” being obstacles to employment: lack of education

and training (87.9%); lack of transportation (86.5%); lack of child care

(84.7%)). Domestic violence is another obstacle faced by many welfare

recipients seeking to find permanent employment, with as many as 60

percent of women receiving welfare experiencing domestic violence as

adults. Richard M. Tolman & Jody Rapheal, A Review o f Research on

Welfare and Domestic Violence 5 (2000) (available at

www.ssw.umich.edu/trapped/pub.html). A lack of training and skills also

severely inhibit WEP workers from becoming self-sufficient.2

Though WEP workers provide valuable labor and services to the City,

the City fails to provide them with the tools necessary to overcome this

obstacle. The Community Voices Heard survey discussed above found that

less than a quarter of the New York City WEP workers responding to the

survey reported receiving any regular training on the job. WEP Work

Experience Program: New York City’s Public Sector Sweat Shop Economy,

at 8. See also Office of the State Comptroller, State of New York, Report

99-J-l, Welfare Reform: Assessing Educational and Training Needs o f

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Recipients 5 (2000) (finding that

assessments often were not made of TANF recipients’ skills and experience

10

http://www.ssw.umich.edu/trapped/pub.html

Allowing harassment and discrimination against WEP workers to go

unchecked will only exacerbate the difficulties they have in transitioning to

permanent employment.* 3 Based on a study covering thirteen states, the

United States Civil Rights Commission reports that:

people of color have encountered insults and disrespect as they

have attempted to navigate the welfare system. . . . women are

frequently subject to sexual inquisitions at welfare offices and

sexual harassment at job activities, often with no recourse.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, A New Paradigm for Welfare Reform:

The Need for Civil Rights Enforcement (Aug., 2002) (available at

www.usccr.gov/pubs/nrwora/welfare.htm), («citing Rebecca Gordon, Applied

Research Center, Cruel and Usual: How Welfare Reform ’ Punishes Poor

People 5, 33-34 (2001)). The emotional toll exacted by such experiences is

enormous. See, e.g., Jin v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 295 F.3d 335, 339

(2d Cir. 2002) (after “months of submitting to the weekly sexual abuse out

of fear of losing her job, [plaintiff] . . . requested disability benefits due to

when making job placements, and thus significant barriers to employment

are not identified and addressed through education and training).

3 A study of employment opportunities for a pool of welfare recipients

in Virginia found that relative to white recipients, blacks are more likely to

be subjected to pre-employment tests (such as drug or criminal background

checks); to receive shorter interviews - even when they have more

education than their white counterparts - ; to work less desirable evening

hours; and to have a more negative relationship with their supervisors. See

Susan T. Gooden, The Hidden Third Party: Welfare Recipients’

Experiences with Employers, 5 J. of Pub. Mgmt. & Soc. Pol’y 69-83 (1999).

l i

http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/nrwora/welfare.htm

the effects of the severe harassment”); Id. at 344-45 (“Requiring an

employee to engage in unwanted sex acts is one of the most pernicious and

oppressive forms of sexual harassment that can occur in the workplace. The

Supreme Court has labeled such conduct ‘appalling’ and ‘especially

egregious.”’) {citing Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc., 510 U.S. 17, 22

(1993)). Workfare recipients forced to provide services under such

conditions can hardly be expected to acquire the personal resources and

skills that will facilitate their successful entry into the job market.

Moreover, those WEP workers who do manage to find permanent

employment face overwhelming barriers to achieving self-sufficiency. Title

VII protections help to ensure that WEP workers are not diverted by

debilitating harassment and discrimination from securing the skills and

training they require to move into permanent employment, and that those

who must return to the program do not become an exploited sub-class of

City workers.

For instance, most WEP workers moving into the permanent work

force will be unable to find a job that pays them a living wage. Average

wages for former welfare recipients nation-wide are approximately $6 to $8

12

per hour, with only about one quarter of such jobs providing health benefits.4

Without health insurance, they will not be able to secure adequate medical

care, further compromising their ability to retain steady employment.5 The

difficulties of finding safe, affordable, and reliable child care also impair the

transition to full-time employment.6

These barriers mean that many former welfare recipients may find

themselves returning to welfare and, thus, to the WEP program just to

survive. Indeed, a recent report by the Urban Institute found that, nationally,

one in five families leaving welfare return within two years. Pamela

See Heather Boushey, Economic Policy Institute, Staying Employed

After Welfare: Work Supports and Job Quality Vital to Employment Tenure

and Wage Growth 4 (June 2002). See also Andrew Bush, Swati Desai, and

Lawrence Meade, Leaving Welfare: Findings from a Survey o f Former New

York City Welfare Recipients 12 (New York City Human Resources

Administration Working Paper 98-01, 1998) (survey of former welfare

recipients found that 48 percent of those who were employed reported that

their income was the same or less than what they had received with welfare).

5 See Staying Employed after Welfare, at 7 (reporting on a national

study which found that low-wage jobs are less likely to offer health

insurance than high wage jobs).

See Staying Employed After Welfare, at 5-8; Building a Ladder to

Jobs and Higher Wages: a Report by the Working Group on New York

City’s Low-Wage Labor Market 124 (Oct. 2000) (more than 30,000 children

on the waiting lists for subsidized child care available to low-income

families in New York City); Citizens’ Committee for Children, Child Care:

The Family Life Issue in New York City 3 (2000) (over 100,000 New York

City Children ages 0 through 5 were eligible for but did not receive child

care subsidies in 2000).

13

Loprest, Who Returns to Welfare 1 (The Urban Institute Series B, No. B-49,

2002). Similarly, a recent survey, conducted by the Rockefeller Institute,

found that of people who left public assistance in New York State during

1999, twenty-one percent reported returning to assistance during the 18 to 24

month follow-up period. The Rockefeller Institute of Government, Leaving

Welfare: Post-TANF Experiences o f New York State Families 26 (2002)

(available at www.rockinst.org/publications/federalism/

leaver_final_June_2002.pdf). Clearly, then, by excluding WEP workers

from Title VII protections, the lower court’s ruling threatens to create a sub

class of workers trapped in discriminatory environments.

III. THE DISTRICT COURT’S RULING SUBVERTS THE PURPOSE

OF TITLE VII

In its exclusion of WEP workers from Title VII protection, the district

court’s decision subverts the purpose of the statute and elevates form over

substance by focusing on superficial criteria to define Plaintiffs employee

status. The decision also deprives a vulnerable population of protection

under the only federal civil rights law expressly intended to bar

discrimination in employment.

A. Applying Title VII protections to the WEP workers in this case

is consistent with the statute’s purpose of eliminating

discrimination in the workplace and the broad interpretation

14

http://www.rockinst.org/publications/federalism/

courts have given Title VII.

In enacting Title VII, Congress sought to eradicate discrimination in

the workplace, animated, at least in part, by its recognition that the

prevalence of racial discrimination in the work environment was a primary

cause of the depressed economic condition of African Americans.

Chief among the complex of motives underlying the equal

employment opportunity provisions of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 was doubtless a desire to enhance the relative social and

economic position of the American black community. Few

domestic problems have proved more intractable, or received

more scholarly attention, than the depressed employment status

of black Americans. The statistics are by now familiar . . . .

Discrimination has often been assumed to be at the root of the

problem. Title VII, by outlawing discrimination, was to

improve substantially the employment prospects of blacks.

Developments in the Law - Employment Discrimination and Title VII o f the

Civil Rights Act o f 1964, 84 Harv. L. Rev. 1109, 1111 (1971). The

legislative sponsors of the bill that eventually became Title VII repeatedly

voiced their concerns that widespread employment discrimination was

leading to rampant unemployment and low wage earnings among blacks and

was having “the effect of severely retarding the economic standards of the

[black] population.” Merrick T. Rossein, Employment Discrimination Law

and Litigation §1-4, at 1-28 n. 27 (2001) (quoting remarks of Sen.

Humphrey). Members of Congress understood that discrimination severely

15

erodes economic opportunity by limiting access to jobs and by creating

debilitating work environments that demoralize and destabilize minority

workers already living at a subsistence level. The key to improving

economic opportunity for African Americans and other racial minorities,

Congress determined, was to create protections against racial discrimination.

Courts consistently have recognized this objective in interpreting Title

VII. The United States Supreme Court has said that the purpose of Title VII

is “to achieve equality of employment opportunities,” Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 429 (1971) - see also Johnson v. Transportation

Agency, 480 U.S. 616, 630 (1987) (Title VII “should not be read to thwart..

. efforts” to further its “purpose of eliminating the effects of discrimination

in the workplace.”) - and to “break down old patterns of racial segregation

and hierarchy.” United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 208 (1979).

See also McKennon v. Nashville Banner Pub. Co., 513 U.S. 352, 358 (1995)

(“Congress designed the remedial measures [in Title VII] to serve as a ‘spur

or catalyst’ to cause employers ‘to self-examine and to self-evaluate their

employment practices and to endeavor to eliminate, so far as possible, the

last vestiges’ of discrimination.”) (quoting Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 417-18 (1975)); Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273,

276 (1982) (“Title VII is a broad remedial measure, designed to ‘assure

16

equality of employment opportunities.’ . . . The Act was designed to bar not

only overt employment discrimination, ‘but also practices that are fair in

form, but discriminatory in operation.’”) (quoting Int 7 Bhd. o f Teamsters v.

U.S., 431 U.S. 324, 348-49 (1977)); County o f Washington v. Gunther, 452

U.S. 161, 178 (1981) (“a ‘broad approach’ to the definition of equal

employment opportunity is essential to overcoming and undoing the effect

of discrimination”) (quoting S. Rep. 867, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. 12 (1964));

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800-01 (1973) (“The

language of Title VII makes plain the purpose of Congress to assure equality

of employment opportunities and to eliminate those discriminatory practices

and devices which have fostered racially stratified job environments to the

disadvantage of minority citizens . . . Title VII tolerates no racial

discrimination, subtle or otherwise.”).

Courts have observed that Title VII should be enforced “to rid from

the world of work the evil of discrimination because of an individual’s race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin,” Armhruster v. Quinn, 711 F.2d 1332,

1340 (6th Cir. 1983), and to prevent employers from “exerting any power

[they] may have to foreclose, on invidious grounds, access by any individual

to employment opportunities otherwise available to him, Sibley Memorial

Hospital v. Wilson, 488 F.2d 1338, 1341 (D.C. Cir. 1973). The Fifth Circuit

17

compellingly articulated this point in Rogers v. EEOC, 454 F.2d 234 (5th Cir.

1971):

[Title VIPs] language evinces a Congressional intention to

define discrimination in the broadest possible terms . . . . We

must be acutely conscious of the fact that Title VII . . . should

be accorded a liberal interpretation in order to effectuate the

purpose of Congress to eliminate the inconvenience, unfairness,

and humiliation of ethnic discrimination . . . . One can readily

envision working environments so heavily polluted with

discrimination as to destroy completely the emotional and

psychological stability of minority group workers . . . Title VII

was aimed at the eradication of such noxious practices.

454 F.2d at 238.

By denying Title VII coverage to WEP workers — among the most

vulnerable of the City’s low-wage population ~ the district court’s ruling

threatens their ability to achieve economic self-sufficiency. As with Title

VII, one of the primary goals of welfare reform ostensibly is to promote

economic independence. See 42 U.S.C. § 602(a)(l)(A)(i). Yet, by

excluding WEP workers from the principal federal civil rights law barring

employment discrimination, the lower court has relegated them to the status

of a class to be permanently exploited and cast out on the social and

economic margins of our society.

18

B. The district court’s ruling contravenes the purpose of Title VII

by failing to account for plaintiffs’ actual work experience - as

pled in their complaints - and instead focusing on artificial

criteria to define the plaintiffs’ employment status.

In determining the applicability of Title VII, the district court focused

its inquiry on whether Plaintiffs received ‘“direct or indirect remuneration’”

from the City. (JA 73) (<citing O ’Connor v. Davis, 126 F.3d 112, 116 (2d

Cir. 1997)). On a bare record and without affording any discovery, the court

concluded that Plaintiffs were not “employees” for Title VII purposes

because they “did not receive employment-related benefits.” (JA 73). The

court simply discounted Plaintiffs’ welfare benefits, which it determined

were not “wages.” Id.

The court erred. Ample case law in this Circuit establishes that Title

VII applies to workers who receive an economic benefit in exchange for

their services. See generally Brief of Amici National Employment Law

Project, el al. in Support of Plaintiff-Appellant Norma Colon. The benefits

received by WEP workers plainly satisfy these criteria. See id. WEP

workers perform essentially the same work as that done by the City s

employees — so much so that the City has reduced its municipal work force

in reliance on their labor -- for payment that enables them to pay their rent,

clothe themselves, and feed their families. The district court s decision

19

ignores this reality and instead elevates form over substance by relying on

superficial labels to describe their compensation. Its finding (effectively as a

matter of law) that WEP participants can never be employees under Title VII

defies common sense, particularly given their role in supplementing and,

frequently, supplanting other City employees. See infra, at Section I.

Moreover, the district court’s decision is incongruous with a body of

Title VII cases that have broadly interpreted the statute to cover

nontraditional, indirect employment relationships. It would be ironic if

WEP participants - who provide valuable services to the City in exchange

for their benefits - were denied Title VII coverage that has been extended to

a less traditional class of workers. For example, in a long line of cases

beginning with Sibley Memorial Hospital v. Wilson, 488 F.2d 1338 (D.C.

Cir. 1973), courts have found cognizable Title VII claims brought by

independent contractor plaintiffs who are not employed by the defendant,

but whose access to employment defendant controls. In Sibley Hospital, the

Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia determined that a private male

nurse who was compensated by patients could maintain a Title VII action

against the hospital where he worked to challenge hospital policies that had

blocked him from offering nursing services to female patients. The court

reasoned that it would defeat the purpose of Title VII

20

[t]o permit a covered employer to exploit circumstances

peculiarly affording it the capability of discriminatorily

interfering with an individual’s employment opportunities with

another employer, while it could not do so with respect to

employment in its own service, [and that to do so] would be to

condone continued use of the very criteria for employment that

Congress has prohibited.

Id. at 1341. A number of circuit and district courts have adopted this

approach. See, e.g., Sherman v. Burke Contracting, Inc., 891 F.2d 1527,

1532 (11th Cir.), cert, denied, 498 U.S. 943 (1990); Gomez v. Alexian Bros.

Hosp., 698 F.2d 1019, 1021 (9th Cir. 1983); Diana v. Schlosser, 20 F. Supp.

2d 348, 350-53 (D. Conn. 1998); Moldand v. Bil-Mar Foods, 994 F. Supp.

1061, 1073 (N.D. Iowa 1998); Pelech v. Klaff-Joss, L.P., 815 F. Supp. 260,

263 (N.D. 111. 1993); King v. Chrysler Corp., 812 F. Supp. 151, 153 (E.D.

Mo. 1993).

This Circuit followed Sibley Hospital in Spirt v. Teachers Ins. &

Annuity Ass’n, 691 F.2d 1054, 1063 (2d Cir. 1982), vacated on other

grounds, 463 U.S. 1223 (1983). In Spirt, this Court determined that a

college professor could maintain a Title VII action against third-party

retirement annuity plans, used by her employer, on the grounds that they

employed sex-segregated mortality tables in calculating retiree benefits.

Acknowledging that the “[p]laintiff clearly [was] not an employee of [the

21

defendant] in any commonly understood sense,” this Court nevertheless

went on to observe that:

[I]t is generally recognized that “the term ‘employer,’ as it is

used in Title VII, is sufficiently broad to encompass any party

who significantly affects access of any individual to

employment opportunities, regardless of whether that party may

technically be described as an “‘employer’” of an aggrieved

individual as that term has generally been defined at common

law.’”

691 F.2d at 1063 (<quoting Vanguard Justice Society, Inc. v. Hughes, 471 F.

Supp. 670, 696 (D. Md. 1979)). Because the retirement plans were “so

closely intertwined” with her employer, were mandatory for tenured faculty

(like plaintiff), and “share[d] [with plaintiffs employer] in the

administrative responsibilities” of managing the plans, this Court deemed

them to be an “employer” for purposes of Title VII. Id.

Subsequently, in Cook v. Arrowsmith Shelburne, Inc., 69 F.3d 1235

(2d Cir. 1995), this Court held that a parent corporation could be held liable

for the discriminatory conduct of its subsidiary’s employees. In assessing

the “degree of interrelationship between the two entities” sufficient to hold

the parent liable, the Court adopted a four-part test that emphasized the

22

degree of control exercised by the parent corporation over the labor relations

of its subsidiary. Id. at 1241.7

The Supreme Court itself has eschewed rigid interpretations of Title

VII. In Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U.S. 337 (1997), for example, the

Court interpreted the term “employee” to include “former” employees,

recognizing that “to hold otherwise would effectively vitiate much of the

protection afforded by [Title VII].” 519 U.S. at 345-46. In Meritor Savings

Bank v. Vinson, A ll U.S. 57 (1986), the Court concluded that the provision

barring discrimination in the “terms, conditions, or privileges of

employment” “evince[d] a congressional intent ‘to strike at the entire

spectrum of disparate treatment of men and women’ in employment,” id.

{citing Los Angeles Dept, o f Water and Power v. Manhart, 435 U.S. 707,

707 n. 13 (1978)), and, therefore, encompassed hostile environment claims.8

7 The Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Circuits have followed this approach in

determining a parent corporation’s liability in Title VII cases. Cook, 69 F.3d

at 1241 (citing cases); see also Trevino v. Celanese Corp., 701 F.2d 397,

404 (5th Cir. 1983) (critical question is “[w]hat entity made the final

decisions regarding employment matters related to the person claiming

discrimination?”).

8 In a related employment context, the Supreme Court has concluded

that Section 1981 covers discrimination against whites, despite the statute’s

literal language providing that “all persons . . . shall have the same right. . .

to make and enforce contracts . . . as is enjoyed by white citizens. . . .

McDonald v. Santa Fe Transportation Co., 427 U.S. 273, 285-86 (1976).

Similarly, this Court has broadly construed Section 1981 to cover at-will

23

An inquiry into the practical realities of WEP workers’ job activities

and responsibilities -- rather than a blanket rule based on naked assumptions

and artificial criteria -- should determine the cognizability of Title VII

claims. It would be cruelly ironic if the City’s WEP program - which is

intended to provide participants with real world work experience did not also

provide the same real world protection afforded others who do the same or

similar work. Title VII should be construed to give effect to the labor

performed by WEP workers - often as a substitute for more highly paid City

employees -- and to require employers who use WEP labor not to

discriminate against or harass WEP workers, in the same way that they are

barred from discriminating against or harassing others who perform the

same or similar work in the same workplace.

employment relationships, in part based on the recognition that to exclude

at-will employees from coverage “would severely weaken the statute . . . and

would deny protection from workplace discrimination to a significant

number of people.” Lauture v. IBM Corp., 216 F.3d 258, 263 (2d Cir.

2000). See also Fadeyi v. Planned Parenthood Ass’n o f Lubbock, Inc., 160

F.3d 1048, 1052 (5th Cir. 1998). The reasons for extending protection to

WEP workers in the Title VII context are no less compelling.

24

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT’S RULING, IF NOT OVERTURNED,

WOULD CREATE A SUBCLASS OF MOSTLY AFRICAN-

AMERICAN AND LATINO WORKERS WHO ARE UNPROTECTED

BY FEDERAL CIVIL RIGHTS LAWS BARRING EMPLOYMENT

DISCRIMINATION ON THE BASIS OF RACE, SEX, OR

NATIONAL ORIGIN AND PROHIBITING SEXUAL HARASSMENT

In the absence of Title VII coverage, WEP workers - the

overwhelming majority of whom are African-American and Latino - would

be unprotected by federal civil rights laws prohibiting employment

discrimination on the basis of race, sex, and national origin and barring

sexual harassment.9 None of the federal civil rights laws enumerated in the

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act

(“PRWORA”), Pub. L. No. 104-93, 110 Stat. 2105 (1996) are aimed

specifically at eliminating discrimination in employment. Rather, their

primary purpose is to bar discrimination in the administration of government

programs or activities. See 42 U.S.C. §608(d) (identifying The Age

Discrimination Act of 1975, 42 U.S.C. §6101 et seq.\ Section 504 of the

9 According to the City’s data, more than 68% of the City’s adult public

assistance recipients are women, and more than 80% are Hispanic or non-

Hispanic black. See Human Resources Administration, NYC Public

Assistance Fact Sheet (available at

http://www.nvc.gov/html/hra/pdf/hrafact Oct 2001.pdf). The City does not

report the gender and racial demographics for public assistance recipients

who are WEP workers. However, there is no reason to suspect that the

demographics of the WEP population differ from that of the general public

assistance population.

25

http://www.nvc.gov/html/hra/pdf/hrafact_Oct_2001.pdf

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. §794; The Americans with

Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. §12101 et seq.; Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000d et seq.).

Of the statutes identified in Section 608(d), only Title VI bars

discrimination on the basis of race and national origin, see 42 U.S.C.

§2000d, and even Title VI has limited applicability: it only prohibits

employment discrimination in federally-funded programs that serve

primarily to provide employment. See, e.g., Ass ’n Against Discrimination in

Employment, Inc. v. City o f Bridgeport, 647 F.2d 256, 276-77 (2d Cir. 1981)

(Title VI claims dismissed because no evidence presented that creation of

employment opportunities was primary objective of the federal assistance),

cert, denied, 455 U.S. 988 (1982). None of the statutes, including Title VI,

bar gender discrimination. Id. Further, private causes of action for disparate

impact are not available under Title VI, see Alexander v. Sandoval, 532 U.S.

275 (2001), as they are under Title VII, see Griggs, 410 U.S. at 436.

The 1997 amendment to the PRWORA, commonly known as the

Welfare-to-Work Act, includes a nondiscrimination provision prohibiting

gender discrimination, but only as to “work activities engaged in under a

program operated with funds provided under [the Act itself].” See 42 U.S.C.

26

§603(a)(5)(I)(iii).10 The Act, therefore, does not cover all workfare workers

- and would not cover the plaintiffs in this action — just those participating

in Welfare-to-Work funded programs. Id. Moreover, the remedies available

to gender discrimination plaintiffs even in Welfare-to-Work programs are far

narrower than those afforded under Title VII. See 42 U.S.C.

§603(a)(5)(I)(iv). The grievance procedure provides an administrative

hearing, rather than expressly granting a private right of action in federal

court. Id. In contrast to Title VII, neither compensatory nor punitive

damages are identified as possible remedies. Id. Complainants are not

afforded the right to a jury of their peers, id., and the statute does not provide

attorneys’ fees, id., all options under Title VII.11

This provision states in full:

In addition to the protections provided under the provisions of

law specified in section 608(c) of this title, an individual may

not be discriminated against by reason of gender with respect to

participation in work activities engaged in under a program

operated with funds provided under this paragraph.

42 U.S.C. §603(a)(5)(I)(iii). The reference to §608(c) (and not §608(d))

appears to be a typographical error.

It is little consolation that a complainant might be able to pursue a

claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. It is true that in enacting Title VII, Congress

did not intend to limit a plaintiffs right to bring a Section 1983 suit against

state and municipal officers in the employment discrimination context. See,

e.g., Annis v. County o f Westchester, 36 F.3d 251, 254 (2d Cir. 1994). But,

27

The consequences of having sparse and inadequate civil rights

protection would be particularly acute for WEP workers, who tend to be

intensely poor, often lack formal education, and have severely limited

employment options. In essence, this population is a captive, vulnerable

unlike Title VII, Section 1983 does not have the advantage of an

administrative remedy, which may be critical for poor complainants who

lack the resources to bring litigation.

Moreover, it is unclear that WEP workers subjected to employment

discrimination would have an adequate remedy at state law. New York

Social Services Law Sec 331(3) provides merely that:

[n]o social services district shall, in the exercising of the

powers and duties established in this title, permit

discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin,

sex, religion or handicap, in the selection of participants,

their assignment or reassignment to work activities and

duties, and the separate use of facilities or other treatment

of participants.

Unlike Title VII, this provision is not aimed at barring discrimination in

employment; and the range of procedural protections and remedies is more

limited. First, it is not clear that this statute confers a private right of action.

At best, it appears that a WEP worker could file a grievance with the local

social services district where she is assigned. If dissatisfied with the results

of the conciliation of the grievance, she could appeal to the State for a fair

hearing. See generally 12 NYCCR Sec. 1300.11(b) (regulations issued by

New York State Department of Labor for conciliation procedure); 12

NYCCR Sec. 1300.11(b)(6) (right to a fair hearing). She also presumably

could bring an Article 78 proceeding, NYCPLR §7801 et seq., but she would

be limited to reinstatement of benefits, not the full panoply of remedies

afforded by Title VII, see, e.g., Davidson v. Capuano, 792 F.2d 275, 278-79

(2d Cir. 1986) (damages for civil rights violations not available in Article 78

proceedings).

28

workforce that, if denied Title VII protections, would be left without the

resources necessary to escape discriminatory, harassing, and abusive

conduct in the workplace.

29

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amici respectfully urge the Court to reverse

the decision below.

Respectfully submitted,

Juan Cartagena

Risa E. Kaufman

COMMUNITY SERVICE

SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

105 E.22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

(212) 254-8900

Foster Maer

Evette Soto-Maldonado

PUERTO RICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE & EDUCATION

FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, 14th floor

New York, New York 10013

(212)219-3360

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

James L. Cott

Elise C. Boddie

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

& EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 965-2200

Dated this the 27th day of September, 2002.

30

RULE 32(a)(7)(B)(i) CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

The undersigned hereby certifies that this brief complies with the

type-volume limitations of R.32(a)(7) and R. 29(d) of the Federal Rules of

Appellate Procedure. Relying on the word count of the word processing

system used to prepare this brief, I hereby represent that the amicus brief of

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service

Society of New York, and Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund,

Inc. in support of Plaintiff-Appellant United States of America, Plaintiff-

Appellant Norma Colon, and Intervenor-Plaintiff-Appellant Tammy Auer

contains 6,277 words, not including the corporate disclosure statement, table

of contents, table of authorities, and certificates of counsel, and is therefore

within the word limit for amicus briefs under Fed. R. App. P. 29(d) and Fed.

R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(B).

COMMUNITY SERVICE

SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

105 E. 22nd St.

New York, NY 10010

Dated this the 27th day of September, 2002.

31

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Risa E. Kaufman, hereby certify that on this 27th day of September,

2002, I served the within brief of amici curiae NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., Community Service Society of New York, and

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. in support of Plaintiff-

Appellant United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant Norma Colon, and

Intervenor-Plaintiff-Appellant Tammy Auer, on the following persons via

FedEx Priority Overnight Delivery Service:

Mordechai Newman

Assistant Corporation Counsel

100 Church Street, Room 6-193

New York, NY 10007

Donna Murphy

Attorney for New York City Housing Authority

250 Broadway 9th, Floor

New York, NY 10007

Sarah S. Normand

Neil Corwin

U.S. Attorney's Office

One St. Andrew's Plaza

New York, NY 10007

Marc Cohan

Anne Pearson

Welfare Law Center

275 Seventh Avenue

New York, New York 10001

32

Daniel D. Leddy, Jr.

5 Parkview Place

Staten Island, NY 10310-3128

Philip Taubman

Taubman & Kimelman

30 Vesey Street, 6th Floor

New York, NY 10007

Jack Tuckner

Tuckner, Sipser, Weinstock & Sipser, LLP

120 Broadway, 18th Floor

New York, NY 10271

Kenneth W. Richardson

305 Broadway, Suite 1100

New York, NY 10007

Jennifer Brown

Yolanda Wu

Timothy Casey

NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund

395 Hudson Street, 5th FI.

New York, NY 10014

Ris

COMMUNITY SERVICE

SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

105 E. 22nd St.

New York, NY 10010

(212) 254-8900

33