McLaughlin v. Callaway Reply Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McLaughlin v. Callaway Reply Brief for Appellant, 1975. 253686b4-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ae2f10f7-6ed1-4f60-8522-e3b3fff143ab/mclaughlin-v-callaway-reply-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

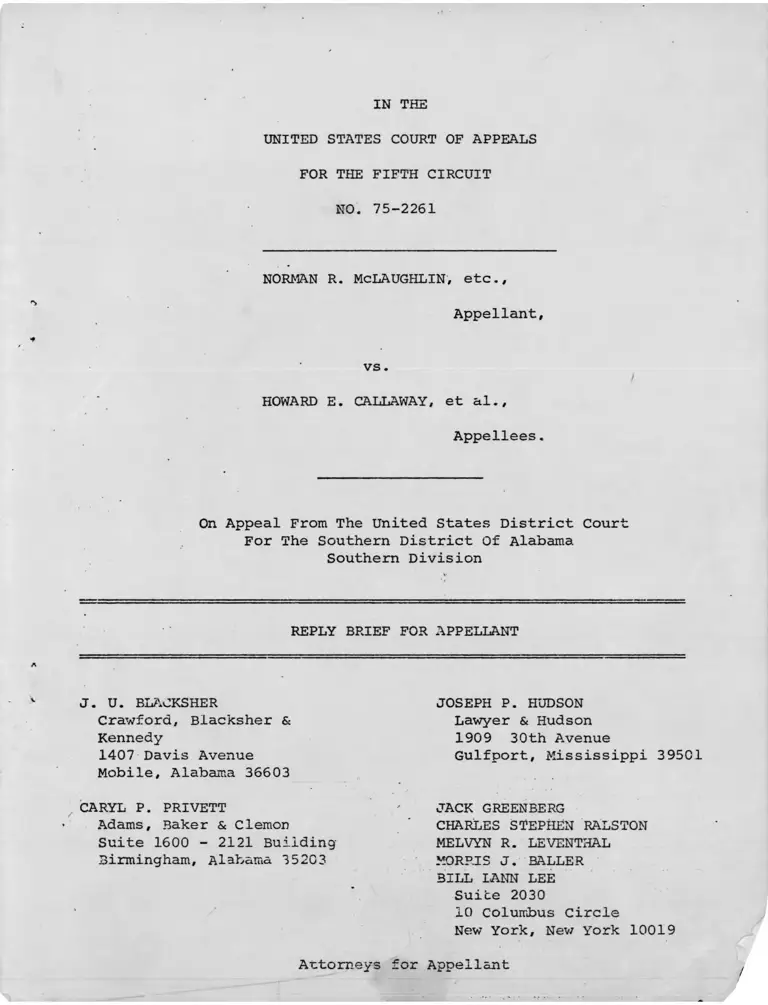

IN THE

-f

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 75-2261

NORMAN R. MCLAUGHLIN, etc.,

Appellant,

vs.

HOWARD E. CALLAWAY, et al..

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of Alabama

Southern Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

J. U. BLACKSHER

Crawford, Blacksher &

Kennedy

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

CARYL P. PRIVETT

Adams, Baker & demon

Suite 1600 - 2121 Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys

JOSEPH P. HUDSON

Lawyer & Hudson

1909 30th Avenue

Gulfport, Mississippi 39501

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

MORRIS J. BALLER

3ILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

for Appellant

TABLE OF CASES

Page

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, __ U.S. __,

45 L. Ed. 2d 280 (1975) ............................ 11,12

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Corp., 415 U.S.

36 (1974) ........................................ 5,17

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1953) ............. 14

Brown v. General Services Administration, 507 F.2d

1300 (2nd Cir. 1974), cert. granted, 43 U.S.L.W.

3625 (May 27, 1975) 16

Caro v. Schultz, __ F.2d __, 10 EPD 510,381

(Sept. 3, 1975) .................................. 5

Carr v. Conoco Plastics, Inc., 423 F.2d 57 (5th

Cir. 1970), affirming per curiam, 295 F. Supp.

128 (N.D. Miss. 1969), cert, denied, 400 U.S.

951 (1970)........................................ 8

Chisholm v. U.S. Postal Service, 9 EPD at p. 7948.... 8,16

Columbia v. Carter, 409 U.S. 418 (1973) ............. 15

Dillon v. Bay City Construction Co., 512 F.2d 801

(5th Cir. 1975) .................................. 7

Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976 (D.C. Cir. 1975).... 5

Drew v. Liberty-Mutual Ins. Co., 480 F.2d 69

(5th Cir. 1973) .................................. 4

Eastland v. T.V.A., 9 EPD 5 9927, p. 6882 (N.D.

Ala. 1975) ....................................... 2

Ellis v. NARF, N.D. Cal. No. C-73-1794 WHO, slip

opinion at 3-7 (September 22, 1975) ......... 2,8,13,15

Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1975)...... 9

Hackley v. Johnson, 360 F. Supp. 1247 (DDC 1973),

rev'd sub nom. Hackley v. Roudebush, __ F.2d

__(D.C. Cir. No. 73-2072)........................ 2,5

- i -

Table of Cases (continued)

PAGE

Handy v. Gayler, 364 F. Supp. 676 (D. Md. 1973) .... 2

Huff v. N.D. Cass Co., 485 F.2d 710 (5th Cir.

1973) ............................................ 7,8

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948) .................. 16

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir.

1968) ........ 8,12

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, __ U.S. __,

44 L.Ed. 2d 295 (1975) ............................ 17,18

Jones v. Alfred E. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968)___ 17

Lance v. Plummer, 353 F.2d 585 (5th Cir. 1965)...... 10,11

Long v. Sapp, 502 F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1974) .......... 8

Miller v. Saxbe, 9 EPD 5 10,005 (DDC 1975).......... 16

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974)......... 5,13,16,17

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1968) ................... '........... 8,12,13

Parks v. Dunlop, 517 F.2d 785 (5th Cir. 1975)___ 4,5,12,14

Predmore v. Allen, 10 EPD 5 10,360, p. 5079

(D. Md. 1975) .................................... 2,8

Richerson v. Fargo, 8 EPD S 9751, p. 6135 (E.D.

Pa. 1974)......................................... 2

Robinson v. Klassen, 9 EPD S 9954 (E.D. Ark. 1974)__ 16

Sampson v. Murray, 415 U.S. 61 (1974) ......... 5

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th

Cir. 1970) ................... ..................... 17

Sosna v. I own, 419 U.S. 393 (1975) ............... 8

Sperling v. United States, 515 F.2d 465 (3rd Cir.

1975) ............................................ 5,11

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229

(1969) ........................................... 17

- ii -

Table of Cases (continued)

PAGE

Swain v. Callaway, Fifth Circuit No. 75-2002 ....... 6,13

Sylvester v. U.S. Postal Service, 9 EPD 5 10,210,

p. 7936 (S.D. Tex. 1975) 2,7

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Rec. Assoc., 410 U.S.

431 (1973) ....................................... 16

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc.,

517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975) ..................... 13

Weinberger v. Salfi, __ U.S. __, 45 L.Ed.2d 522

(1975) 9,10,11,12

- iii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 75-2261

NORMAN R. MCLAUGHLIN, etc.,

Appellant,

v s .

HOWARD H. CALLAWAY, et al..

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District Of Alabama

Southern Division

i

—

i

i

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

This reply brief will respond point by point to a number

of arguments made in appellees' brief. Initially, however,

exactly what the government's position on federal Title VII

class actions is should be made clear. The government has now

abandoned the argument that class actions are permissible in

federal employment discrimination litigation generally, but

improper in the instant case because the plaintiff failed to

bring an "administrative class action" through third party

complaint procedures pursuant to 5 C.F.R. § 713.251. This was

specifically argued by the government and was the reason the

court below precluded a class action.

The regulations enacted pursuant to § 2000e-16

contemplate, and provide procedures for, the

maintenance of a class action in the administrative

process. 5 C.F.R. § 713.251. There has been no

attempt to pursue these procedures by the plaintiff

or any other member or representatives of the class.

The Fifth Circuit has recently expressed, in clear

and definite terms, the necessity of exhausting

administrative remedies under the 1972 Amendment to

Title VII before bringing an action in court.

Penn v. Schlesinger, supra (R. 126-27)(A. ). 1/

The Civil Division now concedes that the government was wrong,

2/for reasons consistently advanced and documented by plaintiff,

1/ The government has argued against class actions because the

"administrative class action" remedy was not exhausted in other

district courts throught the nation. .See, Hacklev v. Johnson. 360

F. Supp. 1247, 1254 n. 11 (DDC 1973); Handy v. Gayler. 364 F. Supp.

676, 67 9 (D. Md. 1973) ; Pointer v. Sampson, 7 EPD 3 9326, p. 750 9

(DDC 1974); Evans v. Johnson, 7 EPD «[[ 9351, p. 7590 (C.D. Cal. 1974)

Richerson v. Fargo, 8 EPD 3 9751, p. 6135 (E.D. Pa. 1974); Eastland

v* l?.«y. > 9 EPD 5 9927, p. 6882 (N.D. Ala. 1975) ; Sylvester v. U.S.

Postal Service, 9 EPD 3 10,210, p. 7936 (S.D. Tex. 1975); PredmorJ”

v. Allen, 10 EPD 5 10,360, p. 5079 (D. Md. 1975); Ellis v. NARF,

N.D. Cal. No. C-73-1794 WHO, Slip opinion at 3-7 (September 22,

1975)(Opinion attached to brief as Appendix A).

2/ R. 170-241, 259-62, 279-307 and 315-22 (A. ).

2

As interpreted by the Civil Service Commission,

the regulations do not permit filing of a class

action administrative complaint. 5 C.F.R. 713.251

is designed to permit third party complaints and

not class action complaints. 5 C.F.R. 713.251 is

not a substitute for the filing of individual

complaints, and plaintiff could not use 5 C.F.R.

713.251 to prosecute his individual claim on behalf

of a class. Rather, it is contemplated that groups,

(e.g., civil rights organizations) or other third

parties will use 713.251 to prosecute "general

allegations * * * which are unrelated to an individual

complaint of discrimination." Appellees' Brief at 13.

It is then argued that the holding of the court below nevertheless

should be affirmed on a ground other than that relied on by the

district court. Id. The Civil Division, of course, fails to

admit that the government has been smoked out on its prior

inconsistent erroneous position and, more importantly, that the

principal ground on which affirmance is sought, that class actions

are statutorily precluded, was necessarily rejected by the

3/

district court.

The statutory preclusion argument now made by the Civil

Division is that every potential class member must file an

"individual" administrative complaint pursuant to 5 C.F.R. § 713.211

et sec., and obtain a final decision on his individual charges

before any joint action could be brought. Class actions pursuant

but hitherto opposed by government lawyers.

3/ If the government had taken its present position — that there

is no administrative vehicle for raising class claims — below,

the district court might have permitted a class action. The court

specifically noted the absence of an administrative record as to

the class claims, which absence would require a full trial d<2 novo

(R. 127; A. ). If the court had known that there was no such

record because one could not be made, this factor would not have

influenced its decision.

As interpreted by the Civil Service Commission,

the regulations do not permit filing of a class

action administrative complaint. 5 C.F.R. 713.251

is designed to permit third party complaints and

not class action complaints. 5 C.F.R. 713.251 is

not a substitute for the filing of individual

complaints, and plaintiff could not use 5 C.F.R.

713.251 to prosecute his individual claim on behalf

of a class. Rather, it is contemplated that groups,

(e.cr., civil rights organizations) or other third

parties will use 713.251 to prosecute "general

allegations * * * which are unrelated to an individual

complaint of discrimination." Appellees' Brief at 13.

It is then argued that the holding of the court below nevertheless

should be affirmed on a ground other than that relied on by the

district court. Id. The Civil Division, of course, fails to

admit that the government has been smoked out on its prior

inconsistent erroneous position and, more importantly, that the

principal ground on which affirmance is sought, that class actions

are statutorily precluded, was necessarily rejected by the

3/district court.

The statutory preclusion argument now made by the Civil

Division is that every potential class member must file an

"individual" administrative complaint pursuant to 5 C.F.R. § 713.211

et seg., and obtain a final decision on his individual charges

before any joint action could be brought. Class actions pursuant

but hitherto opposed by government lawyers.

3/ If the government had taken its present position — that there

is no administrative vehicle for raising class claims — below,

the district court might have permitted a class action. The court

specifically noted the absence of an administrative record as to

the class claims, which absence would require a full trial de novo

(R. .127; A. ). If the court had known that there was no such

record because one could not be made, this factor would not have

influenced its decision.

3

to Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. Pro. in which "one or more members of

a class may sue . . . as representative parties on behalf of all,"

the principal vehicle for judicial vindication of civil rights

guarantees, would simply be eliminated from the arsenal of

weapons to enforce equal employment opportunity available to

federal employees. The consequence would be to effectively

exempt the federal government, the nation's largest employer,

from judicial scrutiny of classwide, systemic discrimination to

which all other employers are subject and the federal government

has long advocated with respect to all other employers.

This in fact is the Civil Division's basic proposition with

regard to the class action question and other issues such as trial

de novo, viz., that the law of employment discrimination developed

by the courts in Title VII cases involving private litigants does

not apply to suits against the federal government. Unfortunately

for the government, this Court has already squarely rejected this

contention in Parks v. Dunlop, 517 F.2d 785 (5th Cir. 1975). There,

the Civil Division argued that district courts lacked jurisdiction

to grant Rule 65 preliminary injunctions to federal employees who

had not fully exhausted administrative remedies. It urged that

Drew v. Liberty-Mutual Ins, Co., 480 F.2d 69 (5th Cir. 1973), did

not apply because, "The Court's reasoning . . . applies only to

discrimination by private employers . . . Brief for Appellant

in No. 75-1786, pp. 17-18. The government also argued generally

- 4 -

in Parks, that Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Corp., 415 U.S. 36 (1974),

and other Title VII decisions were inapplicable because they

involved private employers. Instead, Sampson v. Murray, 415 U.S.

61 (1974) governed. See, Brief for Appellant in No. 75-1786,

at pp. 10-19.

This Court rejected these arguments and squarely held that,

"The intent of Congress in enacting the 1972 amendments to that

Act [Title VII] extending its coverage to federal employment was

to give those public employees the same rights as private employees

enjoy," 517 F.2d at 787, and distinguished Sampson on that ground.

The Supreme Court has also so held with regard to substantive

law in Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 547 (1974) the District

of Columbia Circuit has so held with regard to both substantive

law and remedies in Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976 (D.C. Cir.

1975), and the Third and Seventh Circuits with regard to the right

to plenary judicial hearing and a trial de novo in Sperling v.

United States, 515 F.2d 465 (3rd Cir. 1975) and Caro v. Schultz,

__ F.2d __, 10 E.P.D. 5 10,381 (Sept. 3, 1975). Most devastating

to the government's position is the reversal by the District of

Columbia Circuit, on September 29, 1975, of Hackley v. Johnson,

360 F. Supp. 1247 (D.D.C. 1973), rev1d sub nom., Hackley v.

Roudebush, __ F.2d __ (D. C. Cir. No. 73-2072). In Hackley, the

Court of Appeals held that "Congress intended to bestow on federal

employees the same rights in District Court — including the right

5

to a trial de novo — which it had previously mandated for

private sector employees. . . . " Slip Opinion, p. 1835. The

Civil Division should not be permitted to frustrate and nullify

the purposes of a. statute whose enactment the Civil Service

Commission opposed without success in 1972 because it was

"unnecessary."

1. The Civil Division first contends that plaintiff fails

to meet the typicality requirement of Rule 23 (a) (3) . Brief for

Appellees at 15-19. At best, the issue is premature. Because

the court below ruled that a class action was precluded since no

exhaustion of "administrative class action" procedures occurred,

the question of Rule 23(a) prerequisites was never reached. The

government's present statutory preclusion position of course makes

the issue no less premature. Indeed, the government has admitted

that Rule 23(a) should not be considered for the first time in

this Court in identical circumstances in Swain v. Callaway,

Fifth Circuit No. 75-2002.

These questions are particularly well-suited for

district court to rule upon in the first instance,

and since the district court denied the class

aspects of this suit on jurisdictional grounds

without reaching those issues, we believe it

inappropriate to argue them for the first time

in this Court. Appellee's Brief at 51 n. 30.

The Civil Division argues that the district court's decision

shows that typicality was not satisfied. The court's decision,

however, did not extend to an assessment or determination of the

- 6 -

kinds of discrimination suffered by the class, or to any of the

other Rule 23 prerequisites since the Court based its decision

4/

on a failure to exhaust. In response to government motions,

the court denied any discovery as to discrimination against the

class so that an adequate factual basis for considering any Rule

23 issue was absent. Dillon v. Bay City Construction Co.. 512

F.2d 801, 804 (5th Cir. 1975); Huff v. N.D. Cass Co.. 485 F.2d

710, 713 (5th Cir. 1973)(en banc); Sylvester v. U. S. Postal

Service, 9 EPD fl 10,210 at p. 7936 (S.D. Tex. 1975). Indeed, to

the extent the available record does speak to class issues, it

shows that many of the salient employment policies the court

below found discriminatory in Mr. McLaughlin's case are in fact

generally applicable to black and other minority persons. Brief

for Appellant at 13-15.

The government's whole Rule 23(a) argument demonstrates

a profound misunderstanding of the nature of employment discrimi

nation and of the law of Title VII. It is clear that in suits

4/ The discussion in the government's brief quoting the district

court may erroneously give the impression that the court passed

on typicality. The language quoted at page 16-17 of the appellee'

brief, however, is from the Court's decision on the merits. That

decision did not purport to be a consideration of•Rule 23 criteria

since the court had long before ruled out a class action.

challenging across-the-board employment discrimination, as here,

"While it is true . . . that there are different

factual questions with regard to different employees

it is also true that the 'Damoclean threat of a

racially discriminatory policy hangs over the racial

class [and] is a question of fact common to all

members of the class.' Hall v. Werthan Bag corp.,

M.D. Tenn. 1966, 251 F. Supp. 184," Johnson v.

Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 417 F .2d 1122, 1124. 5/

Long v. Sapp, 502 F .2d 34 (5th Cir. 1974); Ellis v. NAFF, slip

opinion at 8-11, N.D. Cal. No. C-73-1794 (Sept. 22, 1975)(attached

to this Brief as Appendix A); Predmore v. Allen, supra, 10 EPD

at p. 5080; Chisholm v. U. S. Postal Service, supra, 9 EPD at p.

7948. The plaintiff in such suits is attacking a range of

employment practices that have the effect of discriminating

against blacks as a class "by stigmatization and explicit or

implicit application of a badge of inferiority." Sosna v. Iown,

§/419 U.S. 393, 413-14 n. 1 (1975) (White, J., dissenting).

/f

5/ See also Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496 (5th

Cir. 1968); Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F .2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968);

Carr v. Conoco Plastics, Inc., 423 F.2d 57 (5th Cir. 1970), affirming

per curiam, 295 F. Supp. 128 (N.D. Miss. 1969), cert. denied, 400

U.S. 951 (1970); Huff v. N.D. Cass Co., 485 F.2d 710 (5th Cir. 1973)

(en banc) .

6/ Justice White, who dissented from the majority's application

of established Title VII law to class action3generally, went on

to point out that Congress had given persons aggrieved by such

systemic discrimination "standing . . . to continue an attack upon

such discrimination even though they fail to establish injury to

themselves in being denied employment unlawfully."

8

2. The government next contends that a "finality"

requirement of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 precludes class action

treatment under Weinberger v. Saifi, __ U.S. __, 45 L.Ed.2d

522 (1975). Brief for Appellees at 20-23. The Civil Division,

however, is erroneous at every step in its analysis. First,

§ 2000e-16 does not."specifically provide that a civil suit may

be filed only after 'final action'." as the defendants claim

(Brief for Appellees, p. 21). To the contrary, § 2000e-16

"specifically provides" that federal employees can file a Title

VII suit after 180 days from the filing of an administrative

Vcharge when there has been a ”failure to take final action."

See, Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1975). Indeed,

the instant case is just such an action,® as the district court

noted, it was filed some 422 days after the administrative complaint

was filed, and was grounded solely on the lack of final agency

action within 180 days. Appellee's brief itself concedes both

7/ The full text of § 2000e-16 (c) is:

(c) Within thirty days of receipt of notice of

final action taken by a department, agency, or unit

referred to in subsection (a) of this section, or by

the Civil Service Commission upon an appeal from a

decision or order of such department, agency, or unit

on a complaint of discrimination based on race, color,

religion, sex or national origin, brought pursuant to

subsection (a) of this section. Executive Order 11478

or any succeeding Executive orders, or after one

hundred and eighty days from the filing of the initial

charge with the department, agency, or unit or with

the Civil Service Commission on appeal from a decision

9

IIthat federal employees can file civil actions without "finality,

at p. 4, and that the instant case was brought without "final

decision," at p. 8.

Second, the syllogism the Civil Division derives from Salfi

that the "simple requirement" of finality in a civil action

statute necessarily precludes class actions is nonsense. Whether

an administrative decision must be "final" is not even remotely

preclusive. Compare Lance v. Plummer, 353 F.2d 585, 591 (5th Cir.

1965). Rather Salfi stands for the limited proposition that in

a Social Security Act suit brought under the particular restric

tions of 42 U.S.C. § 405(g) each class member must have been a

"party" to the administrative proceedings and have received a

8/

final decision therein. Salfi is not analogous to federal

7/ (Continued)

or order of such department, agency, or unit until such

time as final action may be taken by a department, agency,

or unit, an employee or applicant for employment, if

aggrieved by the final disposition of his complaint, or

by the failure to take final action on his complaint, may

file a civil action as provided in section 2000e-5 of this

title, in which civil action the head of the department,

agency, or unit, as appropriate, shall be the defendant.

8/ As to class members, however, the complaint is

deficient in that it contains no allegations

that they have even filed an application with the

Secretary, much less that he has rendered any decision,

final or otherwise, review of which is sought. The

class thus cannot satisfy the requirements for juris

diction under 42 U.S.C. § 405(g). 45 L.Ed.2d at 538.

10

employee Title VII actions because similar language is absent

from §§ 717(c) and (d) and the general § 706 civil action pro

visions incorporated by § 717 (d) .

Third, the government fails to explain why Salfi would not

also bar a class action in private employee litigation brought

under § 2000e-5 (f) (1). Just as § 2000e-16, that provision speaks

only of "the person aggrieved" bringing a civil action after filing

an administrative complaint. In fact, § 2000e-5 contains an

additional requirement, viz., a notice of the right to sue

addressed to "the person aggrieved." Nevertheless, that single

person can represent all past, present, or would-be employees by

a class action under Title VII even though they have not filed

complaints themselves, as the Supreme Court held the

9/day before it decided Salfi. In short, the attempt to rule out

a class action by pointing to the "person aggrieved" language

must be rejected as it was in Lance v. Plummer, supra.

Fourth, the rejected Erleborn amendment to § 706, containing

language found preclusive in Salfi, is obviously "pertinent."

The rejection of the Erleborn amendment shows why Salfi supports

appellant's position. Brief for Appellant at 51-56. The Civil

Division's argument that the Erleborn amendment is not an indica

tion of Congressional intent because it is limited to § 706 actions

brought by private or state and local government employees simply

ignores § 717(d)'s express incorporation of the general § 706

framework for federal employee suits. Compare Sperling v. U.S.A.,

17 Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody. __ U.S. __, 45 L.Ed.2d 280 (1975)

11

515 F.2d 465, 474 et seq. (3rd Cir. 1975). In any event, nothing

in the legislative history indicates that the rejection of the

Erleborn amendment is not probative of Congressional intent with

respect to class actions by all employees covered by Title VII.

3. The Civil Division also contends that while Saifi,

a Social Security Act case, is applicable to determine the

incidents of a § 717 action, private Title VII decisions approving

class actions are totally inapplicable. As noted above, this

Court's decision in Parks v. Dunlop, supra, rejected such an argument.

Moreover, on its face, this contention is wrong. The Supreme Court's

recent decision in Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, __ U.S. __, 45

L.Ed.2d 280 (1975) and this Circuit's decisions in Oatis v. Crown

Zellerbach Corp., 398 F .2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968 and Jenkins v. United

Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968), construe the general § 706

civil action framework incorporated for federal sector actions

in § 717(d) and are thus directly applicable. As appellant's brief

points out, Congress even specifically cited Oatis and Jenkins in

rejecting the Erleborn amendment.

The particular claim that, because the CSC has "plenary"

remedial power while the EEOC does not, Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach

Corp., 398 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1969) is inapplicable is without

merit. Actual CSC administrative performance indicates that the

reasoning of Oatis with respect to the futility of requiring

identical administrative claims applies with particular force to

12

federal administrative remedies. The Civil Service Commission's

complaint resolution process has been subjected to intense criticism

by Congress, see Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. at 547; the courts,

see e.g., Ellis v. NARF, supra, and the U.S. Commission on Civil

Rights in The Federal Civil Rights Enforcement Effort - 1974, Vol.

V (July 1975) (Relevant excerpts have been reproduced and attached

to the Reply Brief for Appellants in Swain v. Callaway (5th Cir. No.

\

75-2002). The very commitment of the Civil Service Commission to/

enforce equal employment opportunity must be questioned. The Civil

Rights Commission Report found, for instance, that the vaunted

"plenary power" (Brief for Appellees, p. 25) of the CSC was

exercised so feebly in fiscal year 1973 that retroactive relief,

including back pay, was provided to 22 government employees, or

3% of 778 cases (pp. 84-85). The EEOC, in contrast, and in spite

of the supposed deficiencies in enforcement powers relied upon by

appellees in their brief (pp. 24-25), in the same fiscal year was

able to obtain back pay relief for 22,000 employees in the telephone

industry alone, in an amount of $45,000,000. (Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, Eighth Annual Report for FY 1973, p. 24.)

See also, United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., 517

F .2d 826, 834-35, 852, n. 29 (5th Cir. 1975).

It is further claimed that Oatis is inapplicable because

"class actions are unnecessary when injunctive relief is sought

against a governmental defendant because of the presumption that

13

the government will not continue activities which have been

declared unconstitutional or discriminatory." It is far too

late in the day to set this forth as a general proposition much

less to contend its validity in the instant case. Racial

discrimination in the federal service has been illegal under the

Fifth Amendment at least since Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497

(1953). As the "Department of the Army Special Study of Equal

Employment Opportunity in the State of Alabama," conducted in

September-October 1972, found, after examining the range of dis

criminatory employment practices this class action seeks to

eliminate, "The Mobile District has a very long way to go to have

a viable program in equal employment opportunity."

4. The Civil Division concedes that nothing in the legisla

tive history affirmatively prohibits federal Title VII class

actions and appears content merely to argue that legislative

history is "essentially silent." Brief for Appellees at 29-32.

Assuming arguendo that legislative history spoke only to § 706

class actions brought by private or state and local government

employees, § 717(d) would make it applicable to federal Title VII

actions. See, Parks v. Dunlop, supra. Assuming that the legis

lative history only spoke of § 706 class actions, even if § 717

did not expressly refer to § 706, the legislative history would

still be highly probative of general Congressional intent in

favor of class actions. Indeed, even if the legislative history

had been absolutely silent on any right to bring class actions at

14

all, Rule 23 of the Federal Rules would still require them.

The claim that legislative history provides no support for

class action treatment of federal employment discrimination

litigation, however, is also in fact erroneous. Appellant's

brief at 30-32 demonstrates that Congress wanted the Civil Service

Commission and federal agencies to uproot classwide, systemic

discrimination. See Ellis v. NARF, supra, slip opinion at 6-7,

12. The appellees have admitted that the Civil Service Commission has

failed to provide any administrative avenue to correct systemic

discrimination. An acceptance of their argument that there is

no judicial avenue either would result in total frustration of the

main reason for enacting § 717.

5. Leaving aside its exclusivity argument, see infra, the

Civil Division does not contest at all appellant's assertions

concerning the district court's erroneous ruling on the propriety

of class action treatment of claims arising under the Fifth

Amendment and a suit in the nature of mandamus under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1361. As to class action treatment of suits brought pursuant to

to 42 U.S.C. § 1981, the Civil Division apparently acknowledges

that the Supreme Court has "recognized a federal employee's right

to Section 1981 relief," citing District of Columbia v. Carter, 409

l_g/ As to the commentary on legislative history on pages 53-54

of appellant's brief, set forth in Brief for Appellees at 31-32,

to the extent it is cogent, it appears to conflict with the Supreme

Court's analysis in Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 45 L.Ed.2d at

294, n. 8.

15

U.S. 418 (1973), (see also Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948);

u /Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Rec. Assoc,, 410 U.S. 431 (1973),)

adding the caveat that "it is far from clear" in this Circuit.

Brief for Appellees at 36, n. 14. Appellant agrees with the

former proposition, but disagrees with the latter for reasons

stated in the Brief for Appellant at 60-62. Thus, the government's

whole case as to class actions to enforce rights guaranteed by

civil action provisions other than § 717 rests on the exclusivity

of § 717 of Title VII.

6. As to exclusivity, the Civil Division adopts the position

of the Second Circuit in Brown v. General Services Administration,

507 F. 2d 1300. (2nd Cir. 1974), cert. granted, 43 U.S.L.W. 3625

(May 27, 1975). Brief for Appellees at 33-37. First, it should be

noted that the Civil Division does not and cannot assert that

§ 717 on its face repeals all preexisting remedies for federal

employment discrimination, nor that legislative history supports

such a theory. Indeed, it is not even asserted that the § 717

civil action scheme is in apparent substantive conflict with

alternative remedies such as § 1981 as was the case in Morton

v. Mancari, supra, concerning the Indian Reorganization Act of

11/ Cases in which federal employee actions .under 42 U.S.C. § 1981

have been recognized include Chisholm v. U.S. Postal Service, supra,

9 EPD at p. 7947; Miller v. Saxbe, 9 EPD 5 10,005 (DDC 1975) (Gesell,

J.); Robinson v. Klassen, 9 EPD 5 9954 (E.D. Ark. 1974).

16

1934 which established an employment preference for qualified

Indians in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Nothing the Civil

Division argues, a fortiorari, meets the "cardinal rule that . . .

repeals by implication are not favored." Morton v. Mancari,

supra, 417 U.S. 535, 549.

Second, the argument that it makes no sense for Congress

to enact a comprehensive Title VII legislative scheme and then

allow alternative remedies of which Congress may not have been

aware has already been rejected by the Supreme Court with regard

to 42 U.S.C. § 1982 and Title VIIE of the Civil Rights Act of 1968;

Jones v. Alfred E. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 413-417 (1968);

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969) and with

respect to 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and Title VII itself, Johnson v.

Railway Express Agency, __ U.S. __, 44 L.Edc2d 295 (1975). See

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th Cir. 1970).

Moreover, the notion that because civil rights statutes, "although

related, and although directed to most of the same ends, are

separate, distinct and independent," Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency, 44 L.Ed.2d at 302, they are therefore exclusive remedies,

is just the opposite of prevailing law. Alexander v. Gardner-

Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 47 (1974).

Third, the coverage of § 717 is also clearly not coextensive

with that of § 1981 and other pre-existing legal remedies. The

17

and as tostatutes differ both as to relief available

h Vemployees covered. These earlier statutes provide for relief

not necessarily available under Title VII. For these reasons

it is apparent that § 717 and pre-existing statutes complement

one another and provide a diverse arsenal of remedies for an

12/

aggrieved federal employee.

J. U. BLACKSHER

Crawford, Blacksher &

Kennedy

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

CARYL P. PRIVETT

Adams, Baker & demon

Suite 1600 - 2121 Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Respectfully submitted,

1909 30th Avenue

Gulfport, Mississippi 39501

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

MORRIS J. BALLER

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

1?/ Under § 1981 an employee would be entitled in appropriate

circumstances to punitive or compensatory damages. Johnson v.

Railway Express Agency, 44 L.Ed.2d at 30. Title VII's two year

limit action on back pay, if applicable to the federal government,

would not restrict the back pay available under any of the pre

existing remedies. On the other hand, § 717 provides for awards of

attorneys' fees, court appointed counsel, and waiver of court costs.

Ijj/ § 717 does not cover aliens employed outside the limits of the

United States, employees of the Government Accounting Office, and

persons in the Government of the District of Columbia and the

legislative and judicial branches who are not in the competitive

service.

18

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 2nd day of October, 1975,

copies of the Reply Brief for Appellant was served on counsel

for the parties by the United States mail, air mail, special

delivery, postage prepaid, addressed to:

Robert E. Kopp, Esq.

Judith S. Feigin, Esq.

Appellate Section, Civil Division

United States Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

I

19

sp?

UNITED STATES DISTRICT C O U R ^ ^ 5U. §

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA54^ Ff?/.?[Sr- Coin-

^ I S C q ( r

JOSEPH L. ELLIS, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

NAVAL AIR REWORK FACILITY,

et al.,

Defendants.

ETTA D. SAUNDERS, individually

and on behalf of all others

similarly situated.

Plaintiff,

vs.

JAKES W. MIDDENDORF, II, et al.,

Defendants.

U t t i / C / J L i i j / j - i i u x v j L U u a x x j -

No. C-73-1794 WHO

0.

No. C-73-2241 WHO

behalf of all others similarly )

situated, )* )

Plaintiff, )

)

)vs. No. C-74-0028 WHO

) ’

JAMES W. MIDDENDORF, II, et al., )

)

)

.

Defendants.

)

) •

GWENDOLYN DAWSON, )

)

)Plaintiff,

S’ )

vs. )

)

)

No. C-74-0489 WHO

NAVAL AIR STATION, Alameda

California, et al., )

)

)* Defendants. X/ )

)MOSES SAUNDERS, et al., )■ )

Plaintiffs, ■\. )

vs. ) No. C-74-0520 WHO

)NAVAL AIR REWORK FACILITY,

Alameda, California, et al..

)

)

)

)Defendants. / •

)

1 -

MANUEL F. ALVARADO, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

NAVAL AIR REWORK FACILITY,

et al.,

Defendants.

ETTA B. SAUNDERS,

•Plaintiff,

vs.

JAMES W. MIDDENDORFII, et al.,

Defendants.

HARGROW D. BARBER, individually

and on behalf of all others

similarly situated,

Plaintiff,

vs.

JAMES W. MIDDENDORF, II., et al.,

Defendants.

HARGROW D. BARBER,

Plaintiff,

vs.

JAMES W. MIDDENDORF, II, et al. ,

Defendants.

)))))))))))~))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))>))

No. C-74-0764 WHO

No. C-74-1286 WHO

No. C-75-0820 WHO

No. C-75-0886 WHO

OPINION .

In these nine consolidated actions brought under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000e

et seq.), minority civilian employees at the Naval Air Rework

Facility (NARF) and the Naval Air Station (NAS).in Alameda,

California, allege discrimination on the basis of race and

sex. Plaintiffs have moved to certify a class action pursuant

I :

- 2 - .

to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and defend

ants Civil Service Commissioners (Commissioners) have moved to

be dismissed from the case. For the reasons hereinafter set

forth, I certify a class of all past, present, and future Black,

Chicano, Asian and Native American civilian employees of NARF

and NAS and all past, present, and future Black, Chicano, Asian

and Native American applicants for civilian employment at NARF and

NAS,1 2 and I deny the Commissioners' motion to dismiss.

x. THE motion to certify the class

In considering the'motion-to certify the class, it

is important to note that the Court previously ruled that

federal employees are entitled as a matter of right to hearings

de novo in federal court. Ellis v. Naval Air Rework Facility,

C-73-1794 (N.D. Cal., June 20, 1975).^ This becomes important

in considering whether plaintiffs have exhausted their adminis

trative remedies as well as whether their motion to certify the

class meets the requirements of Rule 23 of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure.

A. Exhaustion of Administrative Remedies.

Before considering whether the class plaintiffs seek

to represent meets the requirements of Rule.23 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, the Court must first determine whether

plaintiffs, having failed to raise third-party allegations

through the administrative procedures outlined at 5 C.F.R.

1. I certify this class only for the discovery and liability

phases of the proceedings. At this time, I make no rulings

as to whether the damages portion of the proceedings, as

suming for the moment that liability is established, will

be handled on an individual or class-wide basis.

2. See also, Sperling v. United States, 515 F .2d 465 (3d Cir.

1975); Caro v. Schultz, No. 74-1728 (7th Cir., Sept. 3̂,

1975). cf.. Chandler v. Johnson, 515 F . 2d 251 (9th Cir.

1975).

-3-

I

>

!

I1

1

§713.251 (1974),^ are now precluded from bringing class actions.

The Court is aware that the majority of district courts consider

ing this question has refused to certify class actions where the

administrative avenues have not first been exhausted, e.g. ,

Hackley v. Johnson, 360 F.Supp. 1247 (D.D.C. 1973); McLaughlin

v. Callaway, 382 F-^Supp. 885 (S.D. Ala. 1974).

However, these courts have also held that federal

employees suing under Title VII were not entitled to hearings

de novo in federal court. In light of that ruling, it only made

sense to require the administrative exhaustion of third-party

allegations since the district courts would ultimately be

deciding the discrimination allegations on the basis of the

administrative record. Having ruled that the administrative

record would be controlling, the district courts had virtually

■ no alternative but to require development of the most extensive

administrative records possible.

3. 5 C.F.R. §713.251 provides;

"Third party allegations of discrimination.

(a) Coverage. This section applies to

general allegations by organizations or other

third parties of discrimination in personnel

matters within the agency which are unrelated

to an individual complaint of discrimination

subject to §§713.211 through 713.222.

(b) Agency procedure. The organization

or other third party shall state the allegation

with sufficient specificity so that the agency

may investigate the allegation. The agency may

require additional specificity as necessary to

proceed with its investigation. The agency

shall establish a file on each general allega

tion, and this file shall contain copies of all

material used in making the decision on the

allegation. The agency shall furnish a copy

of this file to the party submitting the allega

tion and shall make it available to the Commis-

• sion for review on request. The agency shall

notify the party submitting the allegation of

. its decision, including any corrective action

• taken on the general allegations, and shall

furnish to the Commission on request a copy of

its decision.

(c) Commission procedures. If the third

party disagrees with the agency decision, it

-4- '

Exhaustion, however, is a judically created remedy

that must be tailored to fit the particular situation and

should not be applied blindly in every case. McKart v. United

States, 395 U.S. 185 (1969). Traditionally, the courts have

required parties to exhaust administrative remedies for the

dual purpose of creating a factual record to assist the court

and to put the agency on notice of plaintiffs' claims, thereby

giving the agency the first opportunity to rectify internal

problems. This Court having ruled that plaintiffs are entitled

to hearings de novo and that the administrative record will not

be determinative of the discrimination claim, it is no longer

sound to require rigid adherence to the administrative avenues

available under 5 C.F.R. §173.251. Sylvester v. United States

Postal Service, No. 73-H-220 (S.D. Tex., Apr. 23, 1975);

Chisholm v. United States Postal Service, No. C-C-73-148 (W.D.

N.C., May 29, 1975). Since plaintiffs will be presenting evi

dence at trial, the Court no longer needs the detailed factual

record of class claims that a "third-party" allegation filed

4under 5 C.F.R. §713.251 might have produced. . * 4

Footnote 3 continued:

may, within 30 days after receipt of the decision,

request the Commission to review it. The request

shall be in writing and shall set forth with par

ticularity the basis for the request. When the

Commission receives such a request, it shall make,

or require the agency to-make, any additional in

vestigations the Commission deems necessary. The

Commission shall issue a decision on the allega

tion ordering such corrective action, with or

without back pay, as it deems appropriate."

4. The Court has serious doubts as to the usefulness of any

record that might have been produced through the adminis

trative avenues available under 5 C.F.R. §713.251. Sec

tion 713.251 does not impose any time limit in which the

agency must act when it is investigating third-party com

plaints, nor does it impose any affirmative duty on the

agency to investigate the charges. The agency is required

to do no more than establish a file on each general allega

tion, and having made a decision, to notify the complain

ing party. The agency file constitutes the only record

of the investigation.

-5-

I also find that it is unnecessary to require plain

tiffs to file "third-party" claims in order to put the defendants

on notice that there was a generalized or class-wide dissatis

faction on the part of minority civilian employees at the naval

base. Each of the named plaintiffs filed an "individual" ad

ministrative complaint pursuant to 5 C.F.R. §713.211 et seq.

Each and every of the "individual" administrative complaints

raised issues of policy and practice that are inherently class-

type claims of discrimination. It is well-settled in the pri

vate sector employment discrimination cases that administrative

complaints are to be construed broadly to encompass any dis

crimination that could be considered to grow out of the adminis

trative charge. Danner v. Phillips Petroleum, 447 F.2d 159

(5th Cir. 1971); King v, Georgia Power Co., 295 F.Supp. 943

(N.D. Ga. 1968). Federal employment claims at the administra

tive level are also entitled to broad construction. The agency's

ovm regulations require that the investigation of administrative

complaints shall include:

" (a) * * * thorough review of the cir

cumstances under which the alleged discrimi

nation occurred, the treatment of members

of the complainant's group identified by his

complaint as compared with the treatment: of ,

other employees in the organizational seg

ment in which the alleged discrimination ...

occurred, and any policies ana practices re

lated to work situations which mav constitute,

or appear to constitute, discrimination even

though they have not been expressly cited by

the complainant. 5 C.F.R. §713.216(a)

In addition, 5 C.F.R. §713.218(c)(2) requires the complaint

examiner to develop a complete record and to receive into evi

dence "information having a bearing on the complaint or employ

ment policies and practices relevant to the complaint * *

• Had the defendants followed their ovm regulations,

they would have examined administratively the very policies

and practices that the plaintiffs now seek to challenge on a

class-wide basis at the judicial level. Defendants cannot

• t«• •

- 6 -

improperly narrow the focus of an "individual" discrimination

complaint at the administrative level and then claim that plain

tiffs have failed to notify the agency of system-wide dissatis

faction. . Chisholm v. United States Postal Service, sugra.

Indeed, there are strong equitable considerations

that favor permitting plaintiffs to pursue a class action des

pite their failure to file administrative third-party allega

tions. Plaintiffs in these actions filed their administrative

complaints without the aid of counsel. They filled out blank

forms supplied to them by the naval base for initiating dis

crimination complaints. The forms do not indicate that plain

tiffs should use a different procedure if they wish to make a

system-wide class action attack on alleged discrimination rather

than raise an individual complaint. Nor do the employing

■ agencies of NARF or NAS or the CSC make any effort to explain

the intricate administrative regulations to the individual

complainants. Against this background, requiring the individual

complainants to use the unspecified and complicated third-party

allegation procedures of 5 C.F.R. §713.251 would run contra to

the legislative aims of the 1972 Amendments to Title VII. One

of the purposes behind these amendments was to permit federal

employees to litigate claims in federal courts without those^

claims first being lost in the quagmire of administrative

remedies requiring exhaustion.5 Accordingly, I hold that plain

tiffs' failure to file third-party allegations pursuant to

5 C.F.R. §713.251 does not preclude their raising class-action

claims in federal court. * •

5. Senate Report No. 92-415 on S 2515, 92d Cong., 1st Sess.

16-17 (1971) stated: .• ; ^

• "The testimony of the Civil Service Commission

notwithstanding, the committee found that an

aggrieved Federal employee does not have access

to the courts. In many cases, the employee must

overcome a U.S. Government defense of sovereign

inununity or failure to exhaust administrative

remedies with no certainty as to the steps re

quired to exhaust such remedies."

-7-

B. Requirements of Rule 23.

Seeking to certify the class under Rule 23(b)(2)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, plaintiffs must meet

the Rule 23 prerequisites for a class action.^

1. Numeroslty.

I find that the class is so numerous that joinder

of all members is impracticable. There are over 1,200 minority civilian

employees at the Alameda naval base. In addition, plaintiffs

seek to bring this action on behalf of future employees and

applicants for employment. Since there is no way now of deter

mining how many of these future plaintiffs there may be, their

joinder is impracticable. Jack v. Amer. Linen Supply Company,

498 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1974). >' •

2. Common Questions of Lav/ or Fact.

I find that there are questions of law and fact common

to the class members. Although defendants argue that the de

tailed civil service rating requirements that must be met for

each federal job position are so varied that each discrimination

claim presents a unique set of facts, I find that, following this

line of reasoning, it would be almost impossible for a federal •

6. Pursuant to Rule 23(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Pro

cedure plaintiffs must establish that:

"One or more members of a class may sue or be

sued as representative parties on behalf of

all only if (1) the class is so numerous that

joinder of all members is impracticable, (2)

there are questions of law or fact common to

the class, (3) the claims or defenses of.the

representative parties are typical of the

• claims or defenses of the class, and (4) the

representative parties will fairly and adequately

protect the interests of the class." .

In addition, they" must satisfy the requirement of Rule

23(b)(2) and establish that:

- 8 -

/

employee to bring a class action discrimination suit since

individualized applications of the civil service ratings would

always be involved. The commonality of issues for both pri

vate and federal employees rests on the common threat of dis

crimination that confronts all members of the class. Johnson

Express, Inc. . , ,v, Georgia Highway,/417-^2^1122 (5th Cir. 1969); Chisholm jv̂ .

United States Postal Service, supra.

While I find that the general claims of discrimina

tion in promotions, hirings, firings, and job training oppor

tunities, present common questions of law and fact for the

named plaintiffs and the class they seek to represent with

respect to the liability phase of these actions, I do note

that the determination of the appropriate amount of damages

due the different class members, if liability is eventually

.established, may pose too many individual questions to be

handled on a class basis. Therefore, I limit my finding tnat

there are common questions of law and fact to the commonality

of issues as to liability and the appropriateness of injunctive

relief. Harvey v. International Harvester Company, 56 F.R.D.

47 (H.D. Cal. 1972). . /

3. Typicality of Claims.

I find that the claims of the representative parties

are typical of the claims of the class. The claims of the

snamed plaintiffs run the gamut of discrimination in hirings,

firings, and promotions. Although there may be individual

variations in the particulars, the claims of the representa

tives need not be identical to those of the class. If all the

members of the purported class would be benefited by the suit

Footnote 6 continued:

"the party opposing the class has acted or re

fused to act on grounds generally applicable to

the class, thereby making appropriate final in

junctive relief or corresponding declaratory re-^

• lief with respect to the class as a whole * • * *.

-9-

plaintiffs seek to bring, the requirement of typicality has

been satisfied. Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 391 F.2d 555

(2d Cir. 1968), aff'd in part, 417 U.S. 156 (1974).

4. Adequacy of Representation.

I find that the representative parties can adequately

and fairly represent the class. Although the named plaintiffs

in these actions are of Black and Chicano ancestry, since their

purpose in bringing these actions is to better the positions of

the minority workers at the naval base as a whole, I find they

can adequately represent the claims of a broad spectrum of

minority workers at the base including employees of Asian and

Native American national origin. I note that there is authority

f

to support the certification of such a broad class for purposes

of discovery and liability determinations where, as here, there

is no evidence of collusion or conflicting claims among members

of the class. Harvey v. International Harvester Company, supra;

Perm v. Sturopf, 308 F.Supp. 1238 (N.D. Cal. 1970).

5. Rule 23(b)(2) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure.

In addition to satisfying all the above requirements

, of Rule 23 (a), I find that the plaintiffs have satisfied the

requirements of Rule 23(b)(2) and have demonstrated that the

defendants have acted on grounds generally applicable to the

class, thereby making injunctive relief or corresponding declara

tory relief with respect to the class as a whole appropriate.

Plaintiffs claim that the defendants have discriminated against

them and the class they seek to represent on the "generally

applicable" grounds of hiring, firing, and promotion, and on

the basis of race, national origin and/or sex. Should plain

tiffs successfully prove these allegations, declaratory and in-

'5<fftCtive relief would be most appropriate. Accordingly, I

i

10

ertify these actions as Rule 23(b)(2)

Purposes of discovery and det • ' 355 a°ti0"S ^ the7 n<i dat™ » * t i o n of liability.

ZZ\ DISM1SS“ OP M E COMMISSIONERS.

Defendants claim that- ^

any way involved in the alle d d ‘ 0nUIUSS1°ners are n°t in

should, therefore be d ■ • r u m i n a t i o n and that they

once again r a i s e s *>» —

ho exhaust the ^ “ * - » - U e d

W n g Prao tic I : r 2 r niStratiVe * » —tne Commissioners s n - _300.104. * C‘F,R* §§300.101-

’ . Commissioners construe their role in

isions too narrowly and that tt„

involved in the eh n h Y are lntegrallythe challenged employment decisions t ,s

base. The CSC ic th at the navalne CSC is the general personnel a

federal government in charge of .rec ^ “ *

ranking, and selection Df • d • • rUltmSnt' measurement,i°n of individuals for initl-,1

nnd competitive promotions in the ^ - n t m e n t

-oo.ioi. 101.103

governing personnel actions tithin' the” "

promulgates and enforces such regulations that T T ” ^

- r y out those rules. 5 „.s.c. *”

specifically charged with regulatin /

heaeral agency. affirmative action p reVieWinS ^

ment °PPort uni ties. 5 c.r.R. sn"3 ^

- o r a l agencies under the ^

^ "ith “ “ ^ d s and regulations s c

the plaintiffs are eventually able t “

been discriminated against the e=tabUsh that they have

relief against their ' „ * ‘o i„i„„otive

— *• - -

against the Commissioners'eni • • «3unctiva relief

° f thGSe " ^ - ^ - t o r y e m p l o Z n T p ^ i c ^

-11-

•w

I do not find the Commissioners' assertion of the ex

haustion requirement to be persuasive. Plaintiffs all filed their

complaints with the employing agencies under 5 C.F.R. §713; defend

ants would insist upon their filing under 5 C.F.R. §§300.101-

300.104 as well.7 Once again, I find the filing of an adminis

trative complaint by each named plaintiff raising system-wide

discrimination allegations adequately put the CSC on notice of

the dissatisfaction of minority workers at the naval base. I

also find that'it would be unduly burdensome to the plaintiffs

to insist that they select the strictly proper section of the

regulations for processing their complaints when the regulations

contain a myriad of confusing and technical regulations requiring

legal sophistication to decipher. No purpose being met by blindly

requiring rigid adherence to the doctrine of exhaustion (McKart

v. United States, supra), I deny the Commissioners' motion to

dismiss.

i Dated: September 18, 1975.

William H. Orncx, or. O United States District Judge

C.F.R. §300.104 provides in pertinent part:

"(a) Employment practices. (1) A candidate

who believes that an employment practice whicn was

applied to him and which is administered or re

quired by the Commission violates a basic require

ment in §300.103 is entitled to appeal to the

Commission. , j •

(2) An appeal shall be filed in writing, shall

set forth the basis for the candidate s. belief that

a violation occurred, and shall be filed with the

Appeals Review Board, U.S. Civil Servicq Commission,

Washington, D.C. 20415, no later than 15 da/ s fJ ° ? e

■ the date the employment practice was applied to je

candidate or the date he became aware of the results

of the application of the employment practice. m e

board may extend the time limit in this subparagraph

for good cause shown by the candidate..

(3) An appeal shall be processed in accordance

with Subpart D of Part 772 of this chapter.

- 19 -