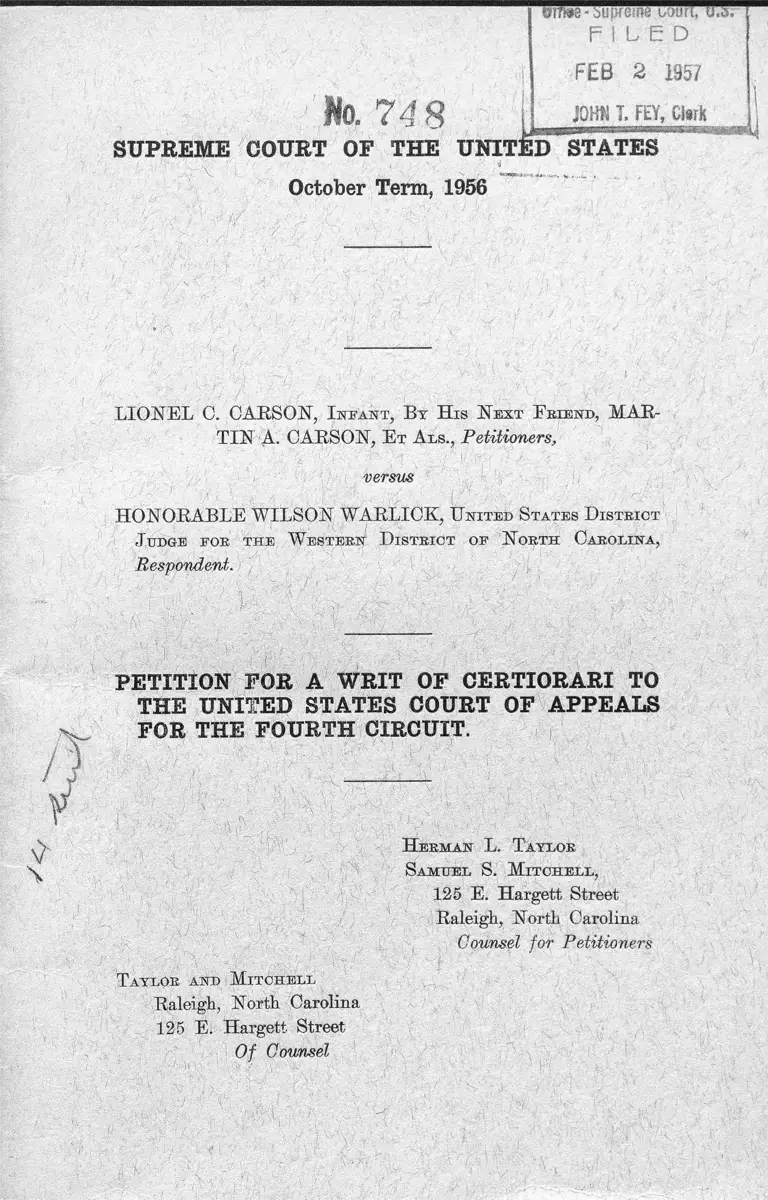

Carson v. Warlick Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

February 2, 1957

42 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carson v. Warlick Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1957. ce411413-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ae404c59-97ed-41a7-a68c-6e547451e8db/carson-v-warlick-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

c riw a * supreme u atin , u .a .

F I L E D

F E B 2 1957

NO. 748 || JOBfl I . FEY, Clark };

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED^STATES

October Term, 1956

LION EL C. CARSON, I n f a n t , By H is N e x t E rien d , M A R

T IN A. CARSON, E t A ls ., Petitioners,

versus

HONORABLE W ILSON W ARLICK, U n it e d S tates D is t r ic t

J udge for t h e 'Western D is tr ic t of N o rth Car o l in a ,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT.

T ay lo r and M it c h e l l

Raleigh, North Carolina

125 E. Hargett Street

Of Counsel

H erm an L . T ay lo r

Sa m u e l S. M it c h e l l ,

125 E. Hargett Street

Raleigh, North Carolina

Counsel for Petitioners

INDEX

OPIN IO N BELOW ........................... .............................

J U R IS D IC T IO N .... ..........................................................

QUESTIONS PR E SE N TE D .........................................

STATU TES IN V O LV E D ................................................

STATEM EN T ................................... .................................

REASONS FOR GRAN TIN G TH E W R IT ............

1. The decision of the Court below is in conflict with

decisions of other United States Courts of Appeals

2. The decision of the Court below is in conflict with

the decision of this Court in Brown et al. vs. Board

of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L.

ed. 653..........................................................................

3. The Court below has reached an erroneous and

monstrous conclusion by pyramiding a series of

inapplicable and conflicting principles of federal

law ................................................................................

4. The questions presented herein are of such great

and recurring significance in the matter of public

school education throughout the Fourth Circuit,

as well as throughout other Circuits, as to make

this a case peculiarly appropriate for the exercise

of this Court’s discretionary jurisdiction................

C O N C LU SIO N ............................................................ ......

A P P E N D IX

“ A ” : Opinion of the Court of Appeals.........................

“ B ” : Order of the Court of Appeals............................

“ C” : Order of the District Court..................................

“ D” : North Carolina General Statutes 115-176

as amended............ ....... ..................................... .

“ E” : Opinion of North Carolina Supreme Court in

Joyner et al. vs. McDowell County Board of

Education, 244 N.C. 164, 92 S.E. 2d 795........

“ F ” : Administrative Ruling (Communications be

tween counsel for Petitioners and the Board

of Education of McDowell County)................

1

2

2

3

3 thru 4

5 thru 11

5

PAGES

6 and 7

7 thru 10

10 and 11

11

12 thru 20

21

22 thru 24

25 thru 27

28 thru 34

35 and 36

ii INDEX

-PAGES

ST A T U T E S:

18 U.S.O. 242.................................................................. 10

42 U.S.C. 1983................................................................ 10

28 U.S.O. 1254(1)......................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. 2 1 0 1 (c )..................................................... 2

North. Carolina General Statutes:

115-176 through 115-179.............. 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 and 13 thru 16

115-176 through 115-179 (amended).............. 3 and 25 thru 27

M ISCELLAN EO U S:

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure— Rule 23(a) (3).... 6

42 Am. Jur. (Public Administrative Law) Sec. 29.... 9

42 Am. Jur. (Public Administrative Law) Sec. 36.... 9

CASES:

Brown et al. vs. Board of Education,

1954— 347 U.S. 483, 74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. ed. 873... 6 and 10

1955— 349 U.S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. ed. 653...3, 6 and 10

Brown et al. vs. Edwin L. Bippy,

(C.A., 5th) 233 E. 2d 796........................................... 5 and 10

Bush vs. Orleans Parish School Board,

U.S.D.C., La. 138 F. Supp. 336................................ 5

Carson et al. vs. Board of Education of McDowell

County, 227 E. 2d 789................................................ 4 and 11

Clemons et al. vs. Board of Education of Hillsboro,

Ohio, et al. (C.A., 6th) 228 E. 2d 853...................... 5 and 10

Carter et al. vs. School Board of Arlington County,

Virginia (C.C.A., 4th) 182 F. 2d 531....................... 7

Chung Yim vs. United States (C.C.A., 8th), 78 E. 2d

43, 296 U.S. 627, 56 S. Ct. 150, 80 L. ed. 446........ 9

Conally vs. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385,

46 S. Ct. 126, 70 L. ed. 322....................... ............... 9

County School Board of Arlington County, Virginia,

vs. Clarissa S. Thompson et al., No. 7310 (O.A.,

4th), ..... E. 2d............................................................ 11

Drumheller vs. Local Board No. 1 et al. (O.C.A., 3rd)

130 E. 2d 610................................................................ 9

PAGES

Herbert Brewer et al. vs. Hoxie School District No.

16 (C.A., 8th), 238 F. 2d 91................................. 5 and 10

Hood vs. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School

District No. 2, Sumter County, South Carolina,

et al. (C.A., 4th), 232 F. 2d 626............................. U

Joyner et al. vs. Board of Education of McDowell

County, 244 H.O. 164, 92 S.E. 2d 795..................... 4 and 7

Jackson et al. vs. 0 . C. Rawdon as President of the

Board of Trustees, Mansfield Independent School

District, et al (C.A., 5th), Civ. Ho. 15927, 235 F.

2d 93, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 655.................................. 5 and 10

Lane vs. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872, 83

L. ed. 1281.,................................................................... 8

Lowell vs. Griffith, 303 U.S. 444, 58 S. Ct. 666,

82 L. ed. 949................................................................ 9

Morgan vs. Tenn. Valley Authority (C.C.A., 6th),

115 F. 2d 990.......... 9

Hotter vs. Derby Oil Co. (O.C.A., 8th), 16 F. 2d 717,

273 U.S. 762, 47 S. Ct. 477, 71 L. ed. 879............ 9

McKissick vs. Carmichael (C.C.A., 4th), 187 F. 2d

949 ......................................................................................... 10

New Jersey State Board of Optometrists et al., 5 FT. J.

412, 75 A. 2d 867, 22 A.L.R. 2d 929....................... 9

Opp. Cotton Mills vs. Administrator of Wage and

Hour Division of Department of Labor, 312 U.S.

126, 61 S. Ct. 524, 85 L. ed. 624................................ 8

Procter & Gamble Distributing Co. vs. Sherman et al.

(D.C., S.D .H .Y .), 2 F. 2d 165.................................. 7 and 8

Panama Refining Co. vs. Ryan, 293 U.S. 388, 55

S. Ct. 241, 79 L. ed. 446............................................. 8

People use of Moore vs. J. 0 . Beekman and Com

pany, 347 111. 92, 179 H.E. 435............... ................ 8

Robinson et al. vs. Board of Education of St. Mary’s

County et al. (U.S.D.O., M d.), Civil Aetion Ho.

8780, 143 F. Supp. 481............................................... 11

index iii

iv INDEX

PAGES

School Board of the City of Charlottesville et al. vs.

Doris Marie Allen et al., No. 7303 (C.A., 4th),

......F. 2 d ........................................................................ 11

United States vs. Coplan (C.A., 2nd), 185 F. 2d 629,

28 A.L.K. 2d 1041, 342 U.S. 920, 72 S. Ct. 362,

96 L. ed. 690................................................................ 10

Yick Wo. vs. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 358, 30 L. ed. 356,

6 S. Ct. 1064.................................................. 9

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

O ctober T e r m , 1956

N o-

L io n el C. Carson , Infant, By His Next Friend, M a r t in A.

Carson , E t A l s ., Petitioners,

verms

H onorable W ilso n W a r l ic k , United States District Judge for

the Western District of North Carolina, Respondent.

PETITION FOB A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

The Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the Order and Decision of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit entered in the a,hove case on November 14,1956.

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit,

(R., Opinion of the Court), is reported a t ..... F. 2d ......, and is

copied in the Appendix to this Petition as Appendix “ A .” The

Order of the District Court for the Western District of North

Carolina is copied in the Appendix to this Petition as Appendix

«C .” The Administrative Ruling which precipitated the instant

controversy is copied herein as Appendix F to this Petition.

2

JURISDICTION

The Order and Opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit are dated November 14, 1956, and both were entered on

the day abovementioned. Copies of both the Order and the

Opinion of said Court are copied in the Appendix to this Petition

as Appendix “ A ” and “ B ” respectively. The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 TT.S.C. 1254(1) and under 28 U.S.C.

2101(c).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

In the Court of Appeals below, petitioners sought a writ of

mandamus, which petitioner prayed to he directed to the United

States District Court for the Western District of North Carolina,

under the terms of which, among other things, the District Court

would he directed to vacate an order of stay of proceedings which

it had entered and to proceed with petitioners’ cause as though

petitioners had either exhausted all administrative remedies or

had no such remedies to exhaust as a prerequisite to obtaining

federal injunctive relief. The Court of Appeals denied the peti

tion for writ of mandamus. The questions presented are:

1. Whether the North Carolina General Statutes 115-178 et

seq. provide an adequate administrative remedy which petitioners

are required to exhaust prior to seeking federal injunctive relief ?

2. Whether petitioners have in fact exhausted such adminis

trative remedies as are applicable to them ?

3. Whether the public school authorities have a subsisting duty,

prior to the entry of judicial decrees, to provide Negro public

school children with public school education on a racially non-

segregated basis ?

4. Whether the Court of Appeals should have entered a writ

of mandamus directing the District Court to vacate its stay of

proceedings and to proceed to judgment in petitioners’ cause?

3

STATUTES INVOLVED

The pertinent portions of North Carolina General Statutes

115-176 through 115-179 are set forth and copied in the Appendix

to this Petition as a footnote to the Opinion of the Court below in

Appendix “ A.” North Carolina General Statutes 115-176 through

115-179, as amended July 27, 1956, during the pendency of the

instant cause, are set forth and copied as Appendix “ D.” How

ever, the amendments make no changes relevant to this Petition.

STATEMENT

The instant action was filed in the United States District Court

for the Western District of North Carolina on August 10, 1953,

because of alleged racial segregation and discrimination in the

matter of public education in McDowell County, North Carolina.

Tour infant petitioners alleged that they “ are residents of and

domiciled in and around the Town of Old Port, McDovrell County,

North Carolina.” Your petitioners also alleged that they were

required by the school authorities, because of their race and color,

to attend public school at Marion, North Carolina, which is some

fourteen or fifteen miles away, while children of the Caucasian or

white race, who were residents of and domiciled in and around

the Town of Old Port, McDowell County, North Carolina, were

provided public school education in the Town of Old Fort. Your

petitioners also particularly alleged that the defendant County

Board of Education maintained and operated its public school

system “ on a separate segregated basis, with white children attend

ing some schools exclusively, and Negro children forced to attend

one school maintained for them exclusively.” These allegations

were admitted in the defendant board’s answer to the original com

plaint, (Record, Exhibit “B,” Pages 26 and 27).

After the 1955 decision by this Court in Brown et al. vs. Board

of Education and allied cases, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99

. L. ed. 653, the District Court presumed to dismiss your petitioners’

action as being moot. On appeal to the Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit the Judgment of dismissal -was vacated and the

4

cause remanded with directions, Carson et al. vs. Board of Educa

tion of McDowell County, 227 F. 2d 789. The directions given

to the District Court by the Court of Appeals for consideration of

your petitioners’ cause was that the District Court “ consider it in

the light of the decision of the Supreme Court, in the school segre

gation case and of the North Carolina statute above mentioned and

with power to stay proceedings therein pending the exhaustion of

administrative remedies under the statute and to order a repleader

if this may seem desirable,” 227 F. 2d 789, at Page 791. The

“ statute” mentioned in the Court of Appeals’ directions is North

Carolina 115-178 et seq. which appears in the Appendix to this

Petition as Appendix “ D .”

On the 26th day of July, 1956, when the instant cause was

before the District Court on motion for leave to file supplemental

pleading, the District Court entered a stay of proceeding, holding

that your petitioners had not exhausted administrative remedies

under North Carolina General Statutes 115-178 et seq. Shortly

thereafterwards, to wit, on the 15th day of August, 1956, your

petitioners filed a petition in the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit in which they alleged, among other things, that they were

still aggrieved by the matters shown in their original complaint,

that they had exhausted such administrative remedies as were

available to them and, in the alternative, that North Carolina Gen

eral Statutes 115-178 et seq. provided no adequate remedy for

them, (R ., Application for Writ of Mandamus, Pages 1 to 18).

To their petition for Writ of Mandamus your petitioners attached

a copy of the Record in Joyner et al. vs. Board of Education of

McDowell County, 244 N.C. 164, 92 S.E. 2d 795, in which their

protracted but futile attempt to secure relief via North Carolina

General Statutes 115-178 et seq. is chronicled, (R., Exhibit “ A ”

to Application for Writ of Mandamus). See Appendix “ E ” of

this Petition. Upon denial of the Writ of Mandamus, your peti

tioners now petition this Court to issue the Writ of Certiorari to

review the Order and Decision of the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit.

5

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The decision below should be reviewed by this Court because

of numerous impelling reasons, all of which are obvious from a

reading of the text and some of which are enumerated immediately

below:

1. The decision of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

has answered two important questions of federal law in a manner

directly in conflict with decisions of the Courts of Appeals for the

Fifth, Sixth and Eighth Circuits, viz., Broivn et al. vs. Edwin L.

Rippy, (C.A., 5th) 233 F. 2d 796; Jackson et al. vs. 0 . G.

Rawdon as President of the Board of Trustees, Mansfield Inde

pendent School District, et al., (C.A. 5th) Civ. No. 15927, 235

F. 2d 93, 1 Race Eel. L. Rep. 655; Clemons et al. vs. Board of

Education of Hillsboro, Ohio, et al., (C.A. 6th) 228 F. 2d 853;

Herbert Brewer et al. vs. Hoxie School District No. 46 (C.A. 8th),

238 F. 2d 91, decided October 25, 1956. The decision below is

grounded upon two fallacious notions: (1 ) that the doctrine of

exhaustion of administrative remedies has the same vigor in public

school desegregation actions as in other actions and, (2 ) that the

school boards have no pre-existing and peremptory duty, apart, from

and prior to the entry of judicial decrees, to provide Negro public

school pupils with public school education on a non-segregated

basis. In Brown et al. vs. Edwin L. Puppy, supra; Clemons et al.

vs. Board of Education of Hillsboro, Ohio, et al., supra; and Jack-

son et al. vs. 0 . C. Rawdon, supra, the Courts of Appeals of the

Fifth, and Sixth Circuits have declined to give vigor or notice to

the doctrine of exhaustion of administrative remedies, and in

those cases, as well as in Herbert Brewer et al. vs. Hoxie School

District No. 46, supra, the Courts of Appeals of the Fifth, Sixth

and Eighth Circuits have recognized and applied to the factual

situations involved a pre-existing and peremptory duty on the part

of the defendant school boards to de-segregate the public schools in

their charge. Again, the instant decision is diametrically in con

flict with the well reasoned opinion of the United States District

Court in the Fifth Circuit upon a similar set of facts. (Bush vs.

Orleans Parish School Board, U. S. D. C,, La. 138 F. Supp. 336).

6

2. The decision of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

is in irreconcilable conflict with the decisions of this Court in Brown

et al. vs. Board of Education and allied cases, 1954: 347 U.S. 483,

74 S. Ct. 686, 98 L. ed. 873; 1955: 349 U.S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753,

99 L. ed. 653. In the abovementioned decisions this Court has

(1 ) enjoined school authorities to de-segregate public schools with

“ all deliberate speed,” (2) sanctioned the application of class action

under F.E.C.P., Eule 2 3 (a )(3 ), (3 ) allowed some leeway for

statutory changes designed to solve the problems necessitated by

the decisions in the so-called Segregation Cases and (4 ) declared

the right of Negro complainants to be admitted “ to public schools

as soon as practicable on a non-discriminatory basis.” On the other

hand and by way of contrast and distortion of the above enumerated

principles, the opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit has (1 ) not enjoined the school authorities to de-segregate

with “ all deliberate speed,” but, through the medium of a nugatory,

wearisome and cumbersome state enacted administrative procedure,

placed the burden of desegregating public schools upon each Negro

child involved rather than upon school authorities, (2 ) emaciated

the class action under F.K.C.P., Eule 2 3 (a )(3 ) by reducing the

class in federal court- to include only those complainants who have

personally exhausted the so-called state administrative remedies,

(3 ) sanctioned a statutory innovation, the necessary and inevitable

operation of which is to thwart and delay desegregation of the

public schools in North Carolina, and (4 ) denied to Negro com

plainants the right to be admitted “ to public school as soon as prac

ticable on a nondiscriminatory basis” by requiring that each plain

tiff, before seeking federal injunctive relief, individually tread the

fruitless and squirrel-cage like procedure provided under North

Carolina General Statutes 115-178 et seq. In short, while this

Court in the Brown and allied cases cited above has declared that

the practice of racial segregation in public school education is

illegal and a deprivation of the “ equal protection of the laws

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment,” the Court below has

attempted to narrow this constitutional proposition to the bare

“ right of these school children to be admitted to the schools of

7

North Carolina without discrimination on the ground of race,”

without taking notice of the correlative duty of school authorities.

3. The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, by entry of the

opinion and order below, has reached a monstrous conclusion of

circuit-wide impact in an important area of American life— the

field of education— by pyramiding a series of inapplicable and

conflicting principles of federal law.

(a) The opinion below applies the doctrine of exhaustion of

administrative remedies to a civil rights action. In doing this it

has passed upon a question heretofore not passed upon by this

Court. It has also sub silentio reversed itself. See Carter et al.

vs. School Board of Arlington County, Virginia, (C.C.A. 4th),

182 F. 2d 531. More importantly, in applying this doctrine to

the facts of the instant case the Court below has done so in a ritual

istic and formalistic manner, inasmuch as the entire record is ample

attestation of the fact that your petitioners did substantially, real

istically and actually exhaust so much of the purported administra

tive remedy as the Court below has held to he applicable to them.

See Joyner vs. McDowell County Board of Education, 244 N.C.

164, 92 S.E. 2d 195; Exhibit “ A ,” “ C -l” and “ C-2” of the Record

before this Court and Appendices “ E ” and “ F ” to this Petition.

Compare Procter & Gamble Distributing Company vs. Sherman

et al., (D. C., S.D.N.Y.) 2 E. 2d 165. The opinion below reads in

part: “ While the presentation of the children at the Old Fort

school appears to have been sufficient as the first step in the admin

istrative procedure provided by statute, the prosecution of a joint

or class proceeding before the school board was not sufficient under

the North Carolina statute as the Supreme Court of North Carolina

pointed out in its opinion; and not until the administrative pro

cedure before the hoard had been followed in accordance with the

interpretation placed upon the statute by that court would appli

cants be in position to say that administrative remedies had been

exhausted.” Again, the Court below has erroneously held that the

question of whether a state administrative remedy has been ex

hausted is a question of state law and that the federal courts, on

8

this question, are bound by the decisions of the state courts. Com

pare Lane vs. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872, 83 L. ed. 1281;

Procter & Gamble Distributing Company vs. Sherman, supra.

(b) The opinion below has apparently confused the principles

of legitimate exercise by administrative agencies of delegated legisl

ative process with the principles of the doctrine of exhaustion of

administrative remedies. The opinion states: “ The authority

given the boards ‘is of a fact finding and administrative nature and

hence is lawfully conferred.’ ” The eases cited in the opinion for

this proposition are cases wherein this Court has sanctioned ruling

making by the administrative agencies, or finding o f fact by admin

istrative agencies preparatory to putting a previously declared law

into effect, or legitimate exercise of police power by legislatures

through administrative agencies. See Opp. Cotton Mills vs. Ad

ministrator of Wage and Hour Division of Dept, of Labor, 312

U.S. 126, 61 S. Ct. 524, 85 L. ed. 624, which is principally relied

upon by the Court below. None of the cases cited are cases wherein

the constitutional rights of an applicant to a hearing and of pro

cedural due process were involved, but all were cases of approved

delegation of legislative power. But if the Court below is correct

in holding that the school boards are exercising delegated legislative

power in hearings on application by complainants in the enrollment

or assignment of public school pupils, and are merely finding facts

preparatory to putting a statute into effect, then North Carolina

General Statutes 115-178, et seq., is no administrative remedy at

all, and talk of exhaustion of administrative remedies under North

Carolina General Statutes 115-178 et seq. is totally irrelevant.

Compare Opp. Cotton Mills v. Administrator of Wage and Hour

Division of Dept, of Labor, supra. Moreover, the standards set

out in North Carolina General Statutes 115-178 et seq. are too

vague, subjective and arbitrary to support the exercise of delegated

legislative power, assuming that the Court below is correct in this

legal conclusion. Compare Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan, 293

U.S. 388, 55 S. Ct. 241, 79 L. ed. 446; People use of Moore vs.

J. 0. Beekman S Co., 347 Tib 92, 179 N.E. 435.

9

(c ) Nevertheless, it is abundantly clear* that North Carolina

General Statutes 115-178 et seq. purports to endow and could only

endow the school boards with administrative pow*er in the matter

of enrollment and assignment of pupils to public schools as con

trasted with delegated legislative power. See Chung Yim vs.

United States, (C.C.A. 8th), 78 F. 2d 43, Cert, denied 296 U.S.

627, 56 S. Ct. 150, 80 L. ed. 446; Matter vs. Derby Oil Go.,

(C.C.A. 8th), 16 F. 2d 717, Cert, denied 273 TT.S. 762, 47 S. Ct.

477, 71 L. ed. 879. The business of assigning and enrollment of

public school children in school is merely a matter of school man

agement and of execution of school law and has none of the attri

butes of legislation, 42 Am. Jur. (Public Administrative Law)

Sections 29 and 36; Chung Yim vs. United States, supra; Matter

vs. Der-by Oil Go., supra; Drumheller vs. Local Board No. 1 et al.,

(C.C.A. 3rd), 130 F. 2d 610; Morgan vs. Tenn. Valley Authority,

(C.C.A. 6th), 115 F. 2d 990. Hence, complainants under the

assignment plan are entitled to all of the rights of procedural due

process.

(d) The Court below has erroneously declined to weigh North

Carolina General Statutes 115-178 et seq. for procedural due

process, presumably because of its mistaken notion that the enact

ment clothed the school authorities with delegated legislative power

as contrasted with administrative power. But if the power given

to the board is administrative, as herein contended, and if the

North Carolina enactment purports to provide an administrative

remedy, then the enactment is void on its face, in that it is a grant

on its face of arbitrary power to the administrative agencies in

volved, Lowell v. Griffith, 303 U.S. 444, 58 S. Ct. 666, 82 L. ed.

949 ; New Jersey State Board of Optometrists et al., 5 N.J". 412,

75 A. 2d 867, 22 A.L.R. 2d 929; Yick Wo. vs. Hopkins, 118 U.S.

358, 30 L. ed. 356, 6 S. Ct. 1064; Connolly vs. General Construc

tion Co., 269 U.S. 385, 46 S. Ct. 126, 70 L. ed. 322. Moreover,

the purported standards, as presumably provided in the statute,

allow for and require the consideration by the school boards of

illegal matters in passing upon the complainants’ constitutional

rights in so far as the statute speaks of “ the best interests of such

10

child,” United States vs. Coplan, (G.A. 2d) 185 F. 2d 629, 28

A.L.K. 2d 1041, Cert, denied, 842 TT.S. 920, 72 S. Ct. 362, 96

L. ed. 690; McKissick vs. Carmichael, (C.C.A, 4th) 187 F. 2d 949;

in so far as the statute forbids the applicant’s admission to a school

i f it would interfere “ with the proper administration of such school

or with the proper instruction of pupils there enrolled,” Jackson

et al. vs. 0. C. Rawdon, supra; Clemons vs. Board of Education of

Hillsboro Ohio, supra; Hoxie School District No. 46 of Lawrence

County et al. vs. Herbert Brewer, et als., supra; and in so far as

the statute forbids the applicant’s admission to a school if it would

endanger the “ health or safety of the children there enrolled.” See

the Hoxie, Jackson and Clemons cases cited above and also Yick

Wo. vs. Hopkins, supra; Brown vs. Board of Education, supra, and

allied cases.

(e) Finally, the Court below seems to be oblivious to the fact

that the scecalled administrative remedy must, in petitioners’ action,

be administered by the very authorities against whom your peti

tioners complain of illegal racial segregation and discrimination.

See North Carolina General Statutes 115-178 et seq. At the very

instance of complaint of racial segregation and discrimination, if

petitioners’ allegations are true, the administrative agencies who

are commissioned to administer the remedy, are already in flagrant

violation of petitioners’ constitutional rights and of their rights

under 42 TT.S.C. 1983. The administrative agencies are also, under

conditions mentioned above, in open violation of 18 U.S.C. 242.

To hold, as the Court below has held, that petitioners are to be

remitted to a remedy administered by the confiseators of their

constitutional rights and by violators of 18 U.S.C. 242 is to judi

cially remit petitioners to the very abuses which are interdicted by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and

to sheer legal formalism, Procter & Gamble Distributing Co. vs.

Sherman et al., supra.

4. The questions presented by this case are of great and recur

ring significance in the matter of interpreting this Court’s decisions

in the so-called public school segregation cases in the Fourth Cir

cuit, as well as in other Circuits. A “ dictum” of the Court of

11

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, when this instant cause was pre

viously before that Court during the Fall Term, 1955, ( Carson

et al. vs. Board of Education, 227 F. 2d 789), relative to the appli

cability of the doctrine of exhaustion of administrative remedies

to cases such as this, has been made the law of the case in Hood vs.

Board of Trustees of Sumter County School District No. 2, Sumter

County, South Carolina, et al., (C.A. 4th) 232 F. 2d 626; Robin

son et al. vs. Board of Education of St. Mary’s County et al.,

(TT.S.D.C., Md.) Civil Action No. 8780, 143 F. Supp. 481. This

same “ dictum” has been applied with formalistic vigor to the instant

proceeding*. Again, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

has recently approved of an extension of its formalistic application

of the doctrine of exhaustion of administrative remedies to pro

ceeding aimed at enforcement of injunctive decrees already entered,

School Board of the City of Charlottesville et al. vs. Doris Marie

Allen et al., No. 7303, and County School Board of Arlington

County, Virginia, vs. Clarissa S. Thompson et al., FTo. 7310, (C.A.

4th) ..... F. 2d ....... The serious questions of the interpretation

of the Fourteenth Amendment in school cases and of the applica

bility of the doctrine of exhaustion of administrative remedies to

this and other civil rights actions of similar import make this a

case peculiarly appropriate for the exercise of this Court’s discre

tionary jurisdiction.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, it is respectfully submitted that

this Petition for a Writ of Certiorari should be granted.

H e e m a s L. T ay lo b

Sa m u e l S. M it c h e l l

125 East Hargett Street

Raleigh, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

T aylo b & M it c h e l l , Of Counsel

12

APPENDIX “A”

L io n el C. Carson-, Infant, By His Next Friend, M a r t in A.

Carson , Et Als., Petitioners,

verms

H onorable W ilso n W a r l ic k , United States District Judge for

the Western District of North Carolina, Respondent.

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS

United States Court of Appeals, Fourth Circuit.

(Argued October 1, 1956. Dated November 14, 1956.)

P arker , Chief Judge:

This is an application for a writ of mandamus in the case wherein

Negro children of Old Fort in McDowell County, North Carolina,

allege that the Board of Education of that county is exercising

discrimination on the grounds of race in refusing to admit them

to schools maintained in the town of Old Fort. When the case was

before us on appeal, we held that the court below erred in dismissing

the case as moot, but ruled that, in further proceedings therein,

the court below should give consideration to whether administrative

remedies provided by the North Carolina statute of March 30,

13

1955, * had been exhausted. Carson v. Board of Education of

McDowell County, 4 Cir. 227 F. 2d 789. After our decision, the

Supreme Court of North Carolina, in an action to which two of

the applicants here were parties, rendered a decision on May 23,

1956, construing the act of March 30, 1955 (Joyner v. McDowell

County Board of Education, 244 N.C. 164, 92 S.E. 2d 795) in

which it said:

“ With respect to the provisions of Gr.S. sec. 115-178, this Court

construes them to authorize the parent to apply to the appro

priate public school official for the enrollment of his child or

children by name in any public school within the county or

city administrative unit in which such child or children reside.

But such parent is not authorized to apply for admission of

any child or children other than his own unless he is the

guardian of such child or children or stands in loco parentis

to such child or children. In the event a parent, guardian or

one standing in loco parentis of several children should apply

for their admission to a particular school, it is quite possible

that b-y reason of the difference in the ages of the children, the

grades previously completed, the teacher load in the grades

involved, etc., the school official might admit one or more of

the children, and reject the others. The factors involved

See General Statutes of North Carolina as follows:

*'Sec. 115-176. County and city boards authorized to provide for

enrollment of pupils.— The county and city boards of education are

hereby authorized and directed to provide for the enrollment in a public

school within their respective administrative units of each child residing

within such administrative unit qualified under the laws of this State for

admission to a public school and applying for enrollment in or admission

to a public school in such administrative unit. Except as otherwise pro

vided in this article, the authority of each such board of education in the

matter of the enrollment of pupils in the public schools within such ad

ministrative unit shall be full and complete, and its decision as to the

enrollment of any pupil in any such school shall be final. No pupil shall

be enrolled in, admitted to, or entitled or permitted to attend any public

school in such administrative unit other than the public school in which

such child may be enrolled pursuant to the rules, regulations and decisions

of such board of education. (1955, c.366, s .l.)

14

necessitate the consideration of the application of any child

or children individually and not en masse. Any interested

parent, guardian or person standing in loco parentis to such

child or children, whose application may he rejected, may

appeal to the appropriate board for a hearing in accordance

with the rules and regulations established by such board.

Furthermore, if the board denies the application for admis

sion of such child or children, the aggrieved party may appeal

in the manner prescribed by statute, G.S. sec. 115-179, to the

superior court, where the matter shall he heard de novo before

a jury in the same manner as civil actions are tried therein.

“ Therefore, this Court holds that an appeal to the superior

court from the denial of an application made by any parent,

guardian or person standing in loco parentis to any child or

children for the admission of such child or children to a par

ticular school, must he prosecuted in behalf of the child or

children by the interested parent, guardian or person standing

in loco parentis to such child or children respectively and not

collectively.

* * * *

“ An additional reason why this proceeding was properly dis

missed is that while it purports to have been brought pursuant

to the provisions of our school enrollment statutes, it is not

Sec. 115-177. Authority to be exercised for efficient administration of

schools, etc .; rules and regulations.— In the exercise of the authority con

ferred by sec. 115-176 upon the county or city boards of education, each

such board shall provide for the enrollment of pupils in the respective

public schools located within such county or city administrative unit so

as to provide for the orderly and efficient administration of such public

schools, the effective instruction of the pupils therein enrolled, and the

health, safety, and general welfare of such pupils. In the exercise of such

authority such board may adopt such reasonable rules and regulations as

in the opinion of the board shall best accomplish such purposes. (1955,

c.366, s.2.)

15

based oil an application for assignment relating to named

individuals as contemplated by the enrollment statutes, but is

in reality a class suit. It is in effect an application for man

damus, requiring the immediate integration of all Negro

pupils residing in the administrative unit in which the Old

Fort school is located, in the Old Fort school. Such a pro

cedure is neither contemplated nor authorized by statute.

Therefore, the appeal is dismissed.”

The applicants did not attempt to comply with the provisions

of the statute as so interpreted by the Supreme Court of North

Carolina, but on July 11, 1956, counsel who are representing them

before this court wrote a letter to the secretary of the Board of

Education, inquiring what steps were being taken for the admis

sion of Negro children to the Old Fort school. The secretary re

plied that “ inasmuch as no Negro pupil has made application, nor

has any parent or person standing in loco parentis made application

for any Negro child to attend school in the town of Old Fort for

Sec. 115-178. Hearing before board upon denial of application for

enrollment.— The parent or guardian of any child, or the person standing

in loco parentis to any child, who shall apply to the appropriate public

school official for the enrollment of any such child in or the admission of

such child to any public school within the county or city administrative

unit in which such child resides, and whose application for such enroll

ment or admission shall be denied, may, pursuant to rules and regulations

established by the county or city board of education apply to such board

for enrollment in or admission to such school, and shall be entitled to a

prompt and fair hearing by such board in accordance with the rules and

regulations established by such board. The majority of such board shall

be a quorum for the purpose of holding such hearing and passing upon

such application, and the decision of the majority of the members present

at such hearing shall be the decision of the board. If, at such hearing,

the board shall find that such child is entitled to be enrolled in such school,

or if the board shall find that the enrollment of such child in such school

will be for the best interests of such child, and will not interfere with the

proper administration of such school, or with the proper instruction of

the pupils there enrolled, and will not endanger the health or safety of

the children there enrolled, the board shall direct that such child be

enrolled in and admitted to such school. (1955, c.366, s.3.)

16

the school year 1956-57, the Board had had no cause to take any

action in this connection.”

Upon receiving this reply, applicants here, plaintiffs in the court

below, on the 12th day of July 1956 moved in the action there

pending to file a supplemental complaint in which, without alleging

compliance with the requirements of the North Carolina statute as

interpreted by the Supreme Court, they asked a declaratory judg

ment and injunctive relief with respect to their right to attend the

Old Fort school. The District Judge denied the motion on the

ground that plaintiffs had not exhausted their administrative reme

dies and stayed proceedings in the cause until same should he

exhausted, hut stated that, as soon as it was made to appear that

they had been exhausted, he would grant such relief as might he

appropriate in the premises, saying:

“ (1 ) That obedient to the per curiam decision of the Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 227 F. 2d 789, this Court

has up until this time and will consistently hereafter consider

this case in the light of the decision of the Supreme Court of

the United States in the so-called School Segregation Case,

and of the North Carolina statute chapter 366 Laws 1955,

Sec. 115-179. Appeal from decision of board.-—Any person aggrieved

by the final order of the county or city board of education may at any

time within ten (1 0 ) days from the date of such order appeal therefrom

to the superior court of the county in which such administrative school

unit or some part thereof is located. Upon such appeal, the matter shall

be heard de novo in the superior court before a jury in the same manner

as civil actions are tried and disposed of therein. T he record on appeal

to the superior court shall consist of a true copy of the application and

decision of the board, duly certified by the secretary of such board. If

the decision of the court be that the order of the county or city board of

education shall be set aside, then the court shall enter its order so provid

ing and adjudging that such child is entitled to attend the school as

claimed by the appellant, or such other school as the court may find such

child is entitled to attend, and in such case such child shall be admitted

to such school by the county or city board of education concerned. From

the judgment of the superior court an appeal may be taken by any inter

ested party or by the board to the Supreme Court in the same manner as

other appeals are taken from judgments of such court in civil actions.

17

G.S. 115, 176-179, set out in the opinion in the 227 Fed.

Reporter 2d 789, and has consistently asserted and now re

affirms that it is the duty under the authority granted to stay

all proceedings herein and to cause the matter to remain con

tinuously at issue on the docket until it should be made to

appear that the plaintiffs herein or some of them have ex

hausted the administrative remedies which are provided for

them or some of them or any of them under the above statute,

and that when such is made to appear the Court will imme

diately entertain a motion by counsel for the plaintiffs or some

of them or any of them to file amendment to the complaint

or to replead, indicating that the rights to which they are

entitled have been denied them on account of their race or

color, and immediately thereafter, and within twenty days,

will require an answer to be filed thereto and will set the

case down with a peremptory setting as the first cause to be

disposed of, either at the regular term or some other called

term of this court, dependent upon the requests of the parties

or those who appear for them as counsel in said cause.”

Upon the denial of the motion, application for writ of mandamus

was filed here to require the District Judge to vacate the order

staying proceedings, to allow the supplemental pleading to be filed

and to proceed with the cause “ as though the Pupil Enrollment Act

had never been enacted.”

We think it clear that applicants are not entitled to the writ of

mandamus which they ask, for the reason that it nowhere appears

that they have exhausted their administrative remedies under the

North Carolina Pupil Enrollment Act, and are not entitled to the

relief which they seek in the court below until these administrative

remedies have been exhausted. (See 227 F. 2d at 790.) In the

supplemental complaint which they proposed to file in the court

below they did, indeed, allege that on August 24, 1955, they had

presented their children at the Old Fort school for admission, that

they were denied admission on the ground of race and that on

August 27 they and certain other Negroes had filed a joint petition

1 8

with the school hoard asking -that their children he admitted to the

school. This petition was denied by the Board in January 1956

and it was an appeal from this order of the Board to the Superior

Court and thence to the Supreme Court of the State in which the

decision of the Supreme Court of May 23, 1956 was rendered.

While the presentation of the children at the Old Tort school ap

pears to have been sufficient as the first step in the administrative

procedure provided by statute, the prosecution of a joint or class

proceeding before the school board was not sufficient under the

North Carolina statute as the Supreme Court of North Carolina

pointed out in its opinion; and not until the administrative pro

cedure before the board had been followed in accordance with the

interpretation placed upon the statute by that court would appli

cants be in position to say that administrative remedies had been

exhausted.

It is argued that the Pupil Enrollment Act is unconstitutional;

but we cannot hold that that statute is unconstitutional upon its

face and the question as to whether it has been unconstitutionally

applied is not before us, as the administrative remedy which it

provides has not been invoked. It is argued that it is unconstitu

tional on its face in that it vests discretion in an administrative

body without prescribing adequate standards for the exercise of

the discretion. The standards are set forth in the second section

of that act, G.S. 115-177, and require the enrollment to be made

“ so as to provide for the orderly and efficient administration of

such public schools, the effective instruction of the pupils enrolled,

and the health, safety and general welfare of such pupils.” Surely

the standards thus prescribed are not on their face insufficient to

sustain the exercise of the administrative power conferred. As

said in Opp Cotton Mills v. Administrator of the Wage and Hour

Division of the Department of Labor, 312 TT.S. 126, 145: “ The

essentials of the legislative function are the determination of the

legislative policy and its formulation as a rule of conduct. Those

essentials are preserved. when Congress specifies the basic conclu

sions; of fact upon ascertainment of which, from relevant data by

a designated administrative agency, it ordains that its statutory

n

command is to be effective,” The authority given the boards “ is of a

fact finding and administrative nature, and hence is lawfully con

ferred.” Sproles v. Binford, 286 TJ.S. 374, 397. See also Douglas

v. N olle, 261 TJ.S. 165, 169-170; Hall v. Geiger Jones Co., 242

TJ.S. 539, 553-554; Mutual Film Corp. v. Hodges, 236 TJ.S. 248;

Mutual Film Corp. v. Ohio Industrial Com’n, 236 TJ.S. 230, 245-

246; Bed “ C” Oil Mfg. Co. v. North Carolina, 222 TJ.S. 380, 394.

Somebody must enroll the pupils in the schools. They cannot

enroll themselves; and we can think of no one better qualified to

undertake the task than the officials of the schools and the school

boards having the schools in charge. It is to be presumed that these

will obey the law, observe the standards prescribed by the legisla

ture, and avoid the discrimination on account of race which the

Constitution forbids. Hot until they have been applied to and

have failed to give relief should the courts be asked to interfere

in school administration. As said by the Supreme Court in Brown

et al. v. Board of Education, et al., 349 TJ.S. 294, 299:

“ School authorities have the primary responsibility for eluci

dating, assessing, and solving these problems; courts will have

to consider whether the action of school authorities constitutes

good faith implementation of the governing constitutional

principles.”

It is argued that the statute does not provide an adequate admin

istrative remedy because it is said that it provides for appeals to

the Superior and Supreme Courts of the State and that these will

consume so much time that the proceedings for admission to a

school term will become moot before they can be completed. It is

clear, however, that the appeals to the courts which the statute

provides are judicial, not administrative remedies and that, after

administrative remedies before the school boards have been ex

hausted, judicial remedies for denial of constitutional rights may

be pursued at once in the federal courts without pursuing state

court remedies. Lane v. Wilson, 307 TJ.S. 268, 274. Furthermore,

if administrative remedies before a school board have been ex-

20

hausted, relief may be sought in the federal courts on the basis

laid therefor by application to the board, notwithstanding time that

may have elapsed while such application was pending. Applicants

here are not entitled to relief because of failure to exhaust what

are unquestionably administrative remedies before the board.

There is no question as to the right of these school children to be

admitted to the schools of North Carolina without discrimination

on the ground of race. They are admitted, however, as indi

viduals, not as a class or group; and it is as individuals that their

rights under the Constitution are asserted. Henderson v. United

States, 339 U.S. 816, 824. It is the state school authorities who

must pass in the first instance on their right to be admitted to any

particular school and the Supreme Court of North Carolina has

ruled that in the performance of this duty the school board must

pass upon individual applications made individually to the board.

The federal courts should not condone dilatory tactics or evasion

on the part of state officials in according to citizens of the United

States their rights under the Constitution, whether with respect to

school attendance or any other matter; but it is for the state to

prescribe the administrative procedure to be followed so long as

this does not violate constitutional requirements, and we see no

such violation in the procedure here required. We are dealing here,

of course, with the administrative procedure of the state and not

with the right of persons who have exhausted administrative reme

dies to maintain class actions in the federal courts in behalf of

themselves and others qualified to maintain such actions.

Mandamus Denied.

21

UNITED STATES COUBT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 7281.

L io n el C. Carson , Infant, By His Next Friend, M a r t in A.

C arson , Et Als., Petitioners,

APPENDIX “B”

vs.

H onorable W ilso n W a r l ic k , United States District Judge for

the Western District of North Carolina, Respondent.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF MANDAMUS

This cause came on to be heard on the petition of Lionel C.

Carson, infant, by his next friend, Martin A. Carson, and others,

for a writ of mandamus; answer of McDowell County Board of

Education; brief and supplement to brief in support of petition;

and the cause was argued by counsel.

On consideration whereof, it is now here ordered and adjudged

by this Court, for the reasons set forth in the opinion of the Court

filed herein, that the petition for a writ of mandamus be, and it is

hereby, denied.

November 14, 1956.

J ohn J. P a r k e r ,

Chief Judge, Fourth Circuit.

A true copy,

Teste:

R ichard M. F. W il l ia m s , J r., Clerk,

U. S. Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit.

22

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED

STATES FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT

OF NORTH CAROLINA

A sh e v il le D iv is io n

APPENDIX “0”

L io n el C. Carson , An Enfant, by bis

Next Friend, M a b t in A. Carson , et al.,

Plaintiffs,

C IV IL No. 1341.

v.

B oard oe E ducation of M cD o w ell

C o u n ty , a body Corporate,

Defendant.

July 26, 1956.

T h e C o u r t : From the bench the Court dictates the following

to be considered along with that which has already been said by

counsel for the plaintiffs and counsel for the defendant, Board of

Education of McDowell County, and by the Court, in discussing

the position of the Court and counsel at this time with respect to

this case:

(1 ) That obedient to the per curiam decision of the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 227 Fed. 2. 789, this Court has up

until this time and will consistently hereafter consider this case in

the light of the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States

in the so-called School Segregation Case, and of the North Caro

lina Statute Chapter 366 laws 1955, G.S. 115, 176-179, set out in

the opinion in the 227 Fed. Reporter 2d 789, and has consistently

asserted and now reaffirms that it is the duty under the authority

28

granted to stay all proceedings herein and to cause the matter to

remain continuously at issue on the docket until it should be made

to appear that the plaintiffs herein or some of them have exhausted

the administrative remedies which are provided for them or some

of them or any of them under the above statute, and that when

such is made to appear the Court will immediately entertain a

motion by counsel for the plaintiffs or some of them or any of them

: o file amendment to the complaint or to replead, indicating that

the rights to which they are entitled have been denied them on

account of their race or color, and immediately thereafter, and

within twenty days, will require an answer to he filed thereto and

will set the case down with a peremptory setting as the first cause to

be disposed of, either at the regular term or some other called term

of this court, dependent upon the requests of the parties or those

who appear for them as counsel in said cause.

(2) This Court is of the opinion that Eaymond Greenlee and

James Bryson, who are parties plaintiff to the action, in this court,

and Albert Joyner and Lucille Lytle, who joined them in the action

against the Board of Education of McDowell County in the civil

action which was decided in the opinion appearing in 244 1ST. C.

page 164, have not exhausted their administrative remedies and

therefore are not now in a position to do other than to proceed to

have their cause heard and thereby exhaust their remedies, and

that when such has come about, those things stated above will he

immediately set into motion and this cause of action heard.

(3 ) The Court finds as a fact that Eaymond Greenlee and James

Bryson, two of the plaintiffs appearing as such in this court, and

their associate plaintiffs, Albert Joyner and Lucille Lytle, insti

tuted such action, after having made their request of the School

Board in the Superior Court of McDowell County, and that the

same was heard by Judge George B. Patton, on a demurrer, and

probably other motions. The demurrer was filed for that “ There

is a defect of parties plaintiff and causes of action.” (G.S. 1-127,

Secs. 4, 5.), amounting to a misjoinder of both parties and causes

of action. This was sustained and such was affirmed by the Su

24

preme Court (244 N.C. 164.) for that, “ Where there is a mis

joinder of both parties and causes of action, the court is not author

ized to direct a severance, but must dismiss the action upon demur

rer,” (G.S. 1-132.) It would therefore appear that i f plaintiffs

or any of them decide to pursue their remedy further, it would be

incumbent upon them to file anew their request with the School

Board, and upon it being given an unfavorable consideration, for

each to carry his cause to the Superior Court and there, with the

privilege of a jury trial, have their cause determined, with the

right of an appeal to the Supreme Court of North Carolina if con

fronted with an adverse verdict; and that if it should then be made

to appear that having exhausted their administrative remedies

under the North Carolina law, each would then be entitled to have

this Court permit an amendment to the complaint or to replead if

such seems desirable and to entertain their motion for relief as is

prescribed by law.

W h er eu po n , the Court, being of the opinion that the adminis

trative remedies thus provided for have not been exhausted, an

nounces that it will stay proceedings herein until such comes about,

and on that being made to appear will order an immediate trial to

the end that the deprivation allegedly brought about will be in

quired into and the rights of the plaintiffs fully and completely

protected.

/ S / W ilso n W a r lic k

U. S. District Judge

25

AN ACT TO AMEND ARTICLE 21, CHAPTER 115

OF THE GENERAL STATUTES, RELATING TO

ASSIGNMENT AND ENROLLMENT OF PUPILS

IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS.

The General Assembly of North Carolina do enact:

Sec tio n 1. G.S. 115-176 is hereby amended to read as follows:

“ Each comity and city hoard of education is hereby authorized and

directed to provide for the assignment to a public school of each

child residing within the administration unit who is qualified under

the laws of this State for admission to a public school. Except as

otherwise provided in this Article, the authority of each hoard of

education in the matter of assignment of children to the public

schools shall be full and complete, and its decision as to the assign

ment of any child to any school shall he final. A child residing in

one administrative unit may he assigned either with or without the

payment of tuition to a public school located in another adminis

trative unit upon such terms and conditions as may he agreed in

writing between the boards of education of the administrative units

involved and entered upon the official records of such hoards. No

child shall be enrolled in or permitted to attend any public school

other than the public school to which the child has been assigned

by the appropriate board of education. In exercising the authority

conferred by this Section, each county and city board of education

shall make assignments of pupils to public schools so as to provide

for the orderly and efficient administration of the public schools,

and provide for the effective instruction, health, safety, and general

welfare of the pupils. Each board of education may adopt such

reasonable rules and regulations as in the opinion of the hoard are

necessary in the administration of this Article.”

Sec . 2. G.S. 115-177 is hereby amended to read as follows:

“ In exercising the authority conferred by §115-176, each county

or city board of education may, in making assignments of pupils,

give individual written notice of assignment, on each pupil’s report

card or by written notice by any other feasible means, to the parent

APPENDIX “D”

26

or guardian of each child or the person standing in loco parentis to

the child, or may give notice of assignment of groups or categories

of pupils by publication at least two times in some newspaper

having general circulation in the administrative unit.”

Sec. 3. Gr.S. 115-178 is hereby amended to read as follows:

“ The parent or guardian of any child, or the person standing in

loco parentis to any child, who is dissatisfied with the assignment

made by a board of education may, within ten (10) days after

notification of the assignment, or the last publication thereof, apply

in writing to the board of education for the reassignment of the

child to a different public school. Application for reassignment

shall be made on forms prescribed by the board of education pur

suant to rules and regulations adopted by the board of education.

I f the application for reassignment is disapproved, the board of

education shall give notice to the applicant by registered mail, and

the applicant may within five (5 ) days after receipt of such notice

apply to the board for a hearing, and shall be entitled to a prompt

and fair hearing on the question of reassignment of such child to a

different school. A majority of the board shall be a quorum for

the purpose of holding such hearing and passing upon application

for reassignment, and the decision of a majority of the members

present at the hearing shall be the decision of the board. If, at the

hearing, the board shall find that the child is entitled to be reas

signed to such school, or if the board shall find that the reassignment

of the child to such school will be for the best interests of the child,

and will not interfere with the proper administration of the school,

or with the proper instruction of the pupils there enrolled, and will

not endanger the health or safety of the children there enrolled, the

board shall direct that the child be reassigned to and admitted to

such school. The board shall render prompt decision upon the

hearing, and notice of the decision shall be given to the applicant

by registered mail.”

Sec . 4. All laws and clauses of laws in conflict with this Act

are hereby repealed.

•27'

Se c . 5. This Act shall be effective upon its ratification.

In the General Assembly read three times and ratified, this the

27th day of July, 1956.

28

IN TH E SUPREM E COURT OF N ORTH CAROLINA

A lb er t J o yn er , L u c il l e L y t l e , J am es B ryson and T h u rm a n

Green lee v . T h e M cD o w e ll C ounty B oard oe E d u ca tio n .

(Filed 23 May, 1956)

A pp e a l by petitioners from Patton, Special Judge, February

Term, 1956, of M cD o w e l l .

This is a proceeding brought on 27 August 1955 by petitioners

who filed with the Board of Education of McDowell County, here

inafter called the Board, a petition “ on behalf of their children

and themselves, and on behalf of other Negro children and parents

similarly situated,” in which, in sum and substance, they assert:

(1) That the (unnamed) children for whom they were speaking

were eligible to attend public schools in McDowell County, North

Carolina, and particularly the school at Old Fort.

(2 ) That the petitioners carried their children to the Old Fort

school on 24 August 1955 and demanded that they then be enrolled

in said school; that the principal of said school, acting in conjunc

tion with and under the direction of the Superintendent of Schools

of McDowell County, then and there denied to children of peti

tioners admission to the said Old Fort School.

(3 ) That the children were denied admission for the reason that

school children were “ not to be assigned in the schools of McDowell

County during the school year 1955-56 on any basis other than that

which has previously existed.”

(4 ) That “ the primary if not the sole basis upon which children

in McDowell County have been assigned to schools has been race

or color.”

(5 ) That the Supreme Court of the United States has declared

enforced racial segregation in public schools illegal.

APPENDIX “E”

29

(6 ) That the refusal to admit children of petitioners to the Old

Fort school “ was based solely and wholly upon race or color.”

The petition, following the foregoing allegations sought redress

in the following language:

“ The undersigned, on behalf of their own children and on behalf

of other Negro children and parents similarly situated, petition

your Board that you forthwith issue a directive, order or mandate

to the aforesaid Superintendent and Principal requiring them

forthwith to admit children of petitioners and other Negro children

similarly situated to the school and school facilities maintained by

vour Board in the Town of Old Fort.”

The petitioners appeared before the Board on 3 October 1955 in

support of their request. In a letter dated 5 January 1956, the

petitioners were informed by the secretary of the respondent Board

of the Board’s denial on 2 January 1956 of petitioners’ request to

have their children enrolled in the public school in Old Fort, North

Carolina. The denial was in the following language:

“ A request on the part of Taylor & Mitchell on behalf of the

Negroes at Old Fort to allow Negroes to attend school at Old Fort

rather than to be transported to Marion to attend school at Hudgins

High, was formally denied by virtue of necessity in that facilities

and room are available a Hudgins High and are not available at

Old Fort. The motion was made by Mr. Boss, seconded by Mr.

Greenlee and duly passed.”

The petitioners, through their counsel, gave notice of appeal to

the Board by telegram on 13 January 1956 and requested the im

mediate certification of the record to the Superior Court. The

record was duly certified as requested.

In apt time, in the Superior Court, the respondent moved to dis

miss the appeal on the ground that the notice of appeal was not

given or filed within ten days as required by statute. In addition

thereto, the respondent filed a demurrer to the petition and assigned

as grounds therefor: (1 ) that the petition failed to state a cause of

action; and (2 ) that there was a misjoinder of both parties and

causes of action.

After hearing argument of counsel for respondent and counsel

for petitioners, the court being of the opinion that the motion to

dismiss should he denied and that the demurrer should be overruled

in so far as it pertains to the failure to state a cause of action, but,

that the demurrer as it relates to the misjoinder of parties and

causes of action should be sustained, entered judgment accordingly.

The petitioners appeal to the Supreme Court, assigning error.

Taylor & Mitchell for petitioners.

Boy W. Davis for respondent.

Attorney-General Rodman, Amicus Curiae, for the State.

D e n n y , J . At the threshold of this appeal the Court is con

fronted with the fact that the questions presented are now academic

as to the school year 1955-56. Even so, Chapter 366 of the Session

Laws of 1955, codified as G.S. 115-176 through G.S. 115-179,

governing the enrollment of pupils in the public schools of North

Carolina is of such public importance that the Court deems it

appropriate to clarify the procedure thereunder.

The appellants’ pertinent assignments of error are directed to

the ruling of the court below in sustaining the respondent’s demur

rer on the grounds of a misjoinder of parties and causes of action

and to the failure of the court to order a severance of the causes

of action, if the court was correct in its ruling as to such misjoinder.

A demurrer should be sustained and the action dismissed where

there is a misjoinder of parties and causes of action, and the court

is not authorized in such cases to direct the severance of the respec

tive causes of action for trial under the provisions of G.S. 1-132.

Perry v. Doub, 238 N.C. 233, 77 S.E. 2d 711; Sellers v. Ins. Go.,

233 N.C. 590, 65 S.E. 2d 21; Erickson v. Starling, 233 N.C. 539,

64 S.E. 2d 832; Teague v. Oil Co., 232 N.C. 469, 61 S.E. 2d 345;

SI

s.c. 232 N.C. 65, 59 S.E. 2d 2 ; Moore County v. Bums, 224 N.C.

700, 32 S.E. 2d 225; Wingler v. Miller, 221 N.C. 137, 19 S.E. 2d

247.

The Court deems it unnecessary to enter into a discussion of the

question of misjoinder in this proceeding. The question is settled

by the statutes governing the enrollment of pupils in the public

schools of North Carolina and, in the opinion of the Court, they do

not authorize the institution of class suits upon denial of an appli

cation for enrollment in a particular school.

The provisions of G.S. 115-176 read as follows: “ The county

and city boards of education are hereby authorized and directed to

provide for the enrollment in a public school within their respective

administrative units of each child residing within such adminis

trative unit qualified under the laws of this State for admission to

a public school and applying for enrollment in or admission to a

public school in such administrative unit. Except as otherwise

provided in this article, the authority of each such hoax’d of educa

tion in the matter of the enrollment of pupils in the public schools

within such administrative unit shall be full and complete, and

its decision as to the enrollment of any pupil in any such school

shall be final. No pupil shall be enrolled in, admitted to, or entitled

or permitted to attend any public school in such administrative

unit other than the public school in which such child may be

enrolled pursuant to the rules, regulations and decisions of such

board of education.”

It is provided in G.S. 115-178 that, “ The parent or guardian

of any child, or the person standing in loco parentis to any child,

who shall apply to the appropriate public school official for the

enrollment of any such child in or the admission of such child to

any public school within the county or city administrative unit in

which said child resides, and whose application for such enrollment

or admission shall be denied, may, pursxxant to rules and regulations

established by the county or city board of education apply to such

board for enrollment in or admission to such school, and shall be

entitled to a prompt and fair hearing by such board in accordance

82

with the rules and regulations established by such board. The

majority of such board shall be a quorum for the purpose of holding

such hearing and passing upon such application, and the decision

of the majority of the members present at such hearing shall be the

decision of the board. If, at such hearing, the board shall find that

such child is entitled to be enrolled in such school, or if the board

shall find that the enrollment of such child in such school will he

for the hest interests of such child, and will not interfere with the

proper administration of such school, or with the proper instruction

of the pupils there enrolled, and will not endanger the health or

safety of the children there enrolled, the board shall direct that

such child he enrolled in and admitted to such school.”

The provisions of Gr.S. 115-179 are as follows: uAny person

aggrieved by the final order of the county or city board of education

may at any time within ten (10) days from the date of such order

appeal therefrom to the superior court of the county in which such

administrative school unit or some part thereof is located. Upon

such appeal, the matter shall be heard de novo in the superior court

before a jury in the same manner as civil actions are tried and

disposed of therein. The record on appeal to the superior court

shall consist of a true copy of the application and decision of the

hoard, duly certified by the secretary of such board. I f the decision

of the court be that the order of the county or city board of educa

tion shall be set aside, then the court shall enter its order so provid

ing and adjudging that such child is entitled to attend the school

as claimed by the appellant, or such other school as the court may

find such child is entitled to attend, and in such case such child shall

be admitted to such school by the county or city board of education

concerned. From the judgment of the superior court an appeal

may be taken by any interested party or by the hoard to the Supreme

Court in the same manner as other appeals are taken from judg

ments of such eoiirt in civil actions.”

With respect to the provisions of G.S. 115-178, this Court con

strues them to authorize the parent to apply to the appropriate

public school official for the enrollment of his child or children by

S3

name in any public school within the county or city administrative

unit in which such child or children reside. But such parent is not

authorized to apply for admission o f any child or children other

than his own unless he is the guardian of such child or children or

stands in loco parentis to such child or children. In the event a

parent, guardian or one standing in loco parentis of several children

should apply for their admission to a particular school, it is quite

possible that by reason of the difference in the ages of the children,

the grades previously completed, the teacher load in the grades

involved, etc., the school official might admit one or more of the

children, and reject the others. The factors involved necessitate

the consideration of the application of any child or children indi

vidually and not en masse. Any interested parent, guardian or

person standing in loco parentis to such child or children, whose

application may be rejected, may appeal to the appropriate board

for a hearing in accordance with the rules and regulations estab

lished by such board. Furthermore, i f the board denies the appli

cation for admission of such child or children, the aggrieved party

may appeal in the manner prescribed by statute (G.S. 115-179) to

the superior court, where the matter shall be heard de novo before a

jury in the same manner as civil actions are tried therein.

Therefore, this Court holds that an appeal to the superior court

from the denial of an application made by any parent, guardian or

person standing in loco parentis to any child or children for the

admission of such child or children to a particular school, must be

prosecuted in behalf of the child or children by the interested

parent, guardian or person standing in loco parentis to such child

or children respectively and not collectively.

The Court notes that the petitioners did not apply for the admis

sion of their children and other FTegro children similarly situated

to the school in Old Fort until the 24-th day of August 1955, the

day the school opened. It would seem that some rule or regulation

might well be promulgated by the county and city boards of educa

tion fixing a date reasonably in advance of the opening of school for

filing such applications. Judicial notice will be taken of the fact

84