Adarand Constructors v. Mineta Appendix to the Brief for the Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 2001

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Adarand Constructors v. Mineta Appendix to the Brief for the Respondents, 2001. f4ae56ea-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ae530a78-748c-4f7c-b170-f5603b2b44f7/adarand-constructors-v-mineta-appendix-to-the-brief-for-the-respondents. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

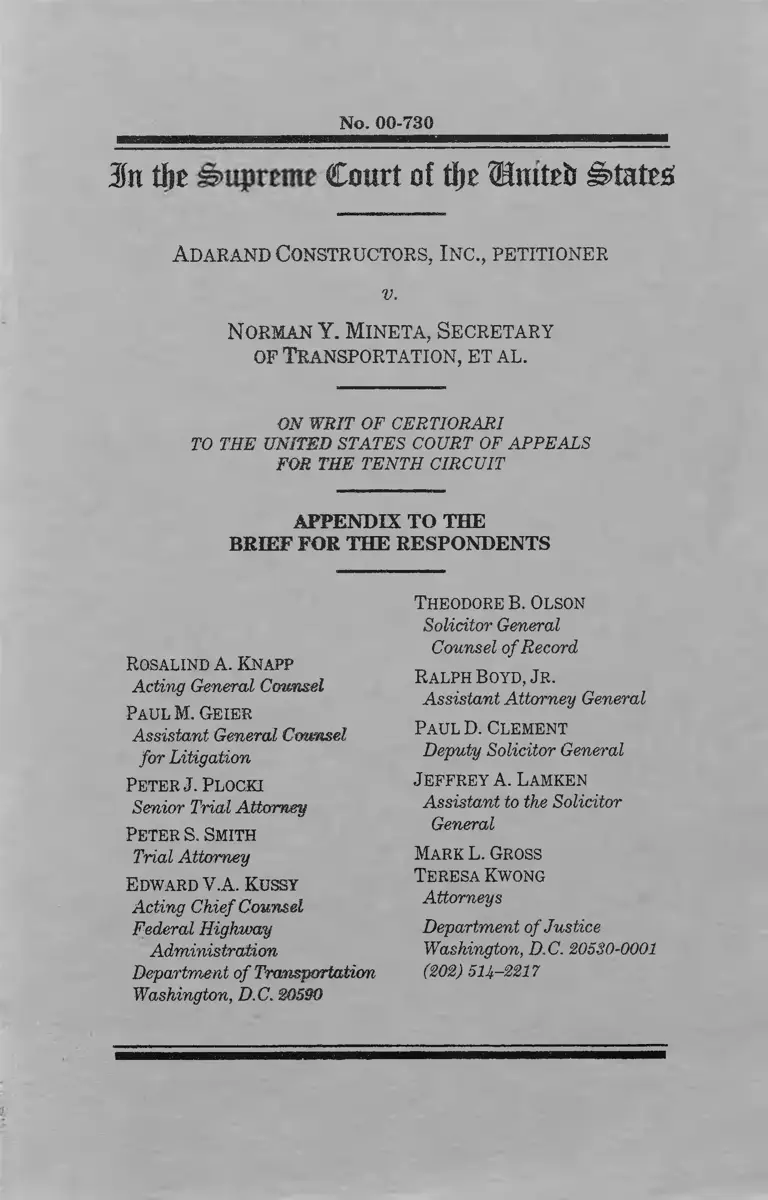

No. 00-730

In tf)£ Court of tlje Umtrb Mutt#

A d ara nd Constructors, I n c ., p e t it io n e r

V.

N orman Y. M in e t a , S ecreta r y

of Tra n spo rta tio n , e t a l .

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

APPENDIX TO THE

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENTS

Rosalind A. Knapp

Acting General Counsel

Paul M. Geier

Assistant General Counsel

for Litigation

Peter J. Plocki

Senior Trial Attorney

Peter s . Smith

Trial Attorney

Edward V.A. Kussy

Acting Chief Counsel

Federal Highway

Administration

Department o f Transportation

Washington, D.C. 20590

Theodore B. Olson

Solicitor General

Counsel of Record

Ralph Boyd, J r .

Assistant Attorney General

Paul D. Clement

Deputy Solicitor General

J effrey a . Lamken

Assistant to the Solicitor

General

Mark L. Gross

Teresa Kwong

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20580-0001

(202) 514-2217

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Appendix A: Relevant constitutional provisions...... .......... la

Appendix B: Relevant provisions of the Transportation

Equity Act for the 21st Century ................................... 2a

Appendix C: Section 8(d) of the Small Business Act, 15

U.S.C. 637(d)...... ............................................................ 8a

Appendix D: Relevant Department of Transportation

Disadvantaged Business Enterprise Regulations,

64 Fed. Reg. 5127-5148 (1999), to be codified at

49 C.F.R. Pt. 2 6 ............................................................ . 18a

Appendix E: Relevant Federal Acquisition Regulations..... 72a

Appendix F: Department of Justice Guidelines for

Affirmative Action, 61 Fed. Reg. 26,042-26,063

(1996)..................................... 101a

Appendix G: Selected Hearings and Reports,

1972-1995 .............................................. 190a

Appendix H: Hearings on the Surface Transportation

Assistance Act of 1982 ....................................... ...... ..... 195a

Appendix I: Hearings and Reports in connection with

ISTEA and TEA-21.............. ..... .......... ........................ 196a

Appendix J: Department of Transportation, Federal

Highway Administration, Central Federal Lands

Highway Division, Colorado FH 60-2(2), West

Dolores, Proposal and Contract (Proposal of Moun

tain Gravel & Construction Company)..... ..................... 198a

( 1 )

APPENDIX A

C o n st it u t io n a l P r o v isio n s

1. The Spending Clause of the United States Consti

tution, U.S. Const. Art. 1, § 8, Cl. 1, provides:

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes,

Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide

for the common Defense and general Welfare of the United

States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform

throughout the United States.

2. The Fifth Amendment to the United States Consti

tution, U.S. Const. Amend. V, provides:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or other

wise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment

of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval

forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War

or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the

same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor

shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness

against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law; nor shall private property be

taken for public use, without just compensation.

3. The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution, U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, provides in pertinent

part:

SECTION 1. * * * No state shall * * * deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws.

* * * * *

SECTION 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by

appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

(1 )

2a

APPENDIX B

The Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century

The Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century, Pub.

L. No. 105-178, Tit. I, § 1101,112 Stat. I l l , provides in

pertinent part:

An Act

To authorize funds for Federal-aid highways, highway

safety programs, and transit programs, and for other pur

poses.

June 9,1998

[H.R. 2400]

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives

of the United States o f America in Congress assembled,

* * * * *

TITLE I—FEDERAL AID HIGHWAYS

Subtitle A—Authorizations and Programs

SEC. 1101. AUTHORIZATION OF APPROPRIATIONS.

(a) IN GENERAL.—The following sums are authorized to be

appropriated out of the Highway Trust Fund (other

than the Mass Transit Account):

* * * * *

(b) DISADVANTAGED BUSINESS ENTERPRISES.—

(1) GENERAL RULE.—Except to the extent tha t the

Secretary determines otherwise, not less than 10 percent of

the amounts made available for any program under titles I,

III, and V of this Act shall be expended with small business

3a

concerns owned and controlled by socially and economically

disadvantaged individuals.

(2) DEFINITIONS.—In this subsection, the following

definitions apply:

(A) SMALL BUSINESS CONCERN.—The term “small

business concern” has the meaning such term has under

section 3 of the Small Business Act (15 U.S.C. 632);

except that such term shall not include any concern or

group of concerns controlled by the same socially and

economically disadvantaged individual or individuals

which has average annual gross receipts over the pre

ceding 3 fiscal years in excess of $16,600,000, as adjusted

by the Secretary for inflation.

(B) SOCIALLY AND ECONOMICALLY DISADVANTAGED

INDIVIDUALS.—The term “socially and economically

disadvantaged individuals” has the meaning such term

has under section 8(d) of the Small Business Act (15

U.S.C. 637(d)) and relevant subcontracting regulations

promulgated pursuant thereto; except that women shall

be presumed to be socially and economically disadvan

taged individuals for purposes of this subsection.

(3 ) ANNUAL LISTING OF DISADVANTAGED BUSINESS

ENTERPRISES.—Each State shall annually survey and

compile a list of the small business concerns referred to in

paragraph (1) and the location of such concerns in the State

and notify the Secretary, in 'writing, of the percentage of

such concerns wThich are controlled by women, by socially

and economically disadvantaged individuals (other than

women), and by individuals who are women and are other

wise socially and economically disadvantaged individuals.

(4) UNIFORM CERTIFICATION.— The Secretary shall

establish minimum uniform criteria for State governments to

4a

use in certifying whether a concern qualifies for purposes of

this subsection. Such minimum uniform criteria shall in

clude, but not be limited to on-site visits, personal inter

views, licenses, analysis of stock ownership, listing of equip

ment, analysis of bonding capacity, listing of work com

pleted, resume of principal owners, financial capacity, and

type of work preferred.

(5) COMPLIANCE WITH COURT ORDERS.— Nothing in

this subsection limits the eligibility of an entity or person to

receive funds made available under titles I, III, and V of this

Act, if the entity or person is prevented, in whole or in part,

from complying with paragraph (1) because a Federal court

issues a final order in which the court finds that the require

ment of paragraph (1), or the program established under

paragraph (1), is unconstitutional.

(6) REVIEW BY COMPTROLLER GENERAL.— Not later

than 3 years after the date of enactment of this Act, the

Comptroller General of the United States shall conduct a

review of, and publish and report to Congress findings and

conclusions on, the impact throughout the United States of

administering the requirement of paragraph (1), including an

analysis of—

(A) in the case of small business concerns certified in

each State under paragraph (4) as owned and controlled by

socially and economically disadvantaged individuals—

(i) the number of the small business concerns; and

(ii) the participation rates of the small business

concerns in prime contracts and subcontracts funded

under titles I, III, and V of this Act;

5a

(B) in the case of small business concerns described in

subparagraph (A) that receive prime contracts and sub

contracts funded under titles I, III, and V of this Act—

(i) the number of the small business concerns;

(ii) the annual gross receipts of the small business

concerns; and

(iii) the net worth of socially and economically dis

advantaged individuals that own and control the small

business concerns;

(C) in the case of small business concerns described in

subparagraph (A) that do not receive prime contracts and

subcontracts funded under titles I, III, and V of this Act—

(i) the annual gross receipts of the small business

concerns; and

(ii) the net worth of socially and economically

disadvantaged individuals that own and control the

small business concerns;

(D) in the case of business concerns that receive

prime contracts and subcontracts funded under titles I,

III, and V of this Act, other than small business concerns

described in subparagraph (B)—

(i) the annual gross receipts of the business con

cerns; and

(ii) the net worth of individuals that own and

control the business concerns;

(E) the rate of graduation from any programs carried

out to comply with the requirement of paragraph (1) for

small business concerns owned and controlled by socially

and economically disadvantaged individuals;

6a

(F) the overall cost of administering the requirement

of paragraph (1), including administrative costs, certifica

tion costs, additional construction costs, and litigation

costs;

(G) any discrimination on the basis of race, color,

national origin, or sex against small business concerns

owned and controlled by socially and economically dis

advantaged individuals;

(H) (i) any other factors limiting the ability of small

business concerns owned and controlled by socially and

economically disadvantaged individuals to compete for

prime contracts and subcontracts funded under titles I,

III, and V of this Act; and

(ii) the extent to which any of those factors are

caused, in whole or in part, by discrimination based on

race, color, national origin, or sex;

(I) any discrimination, on the basis of race, color, na

tional origin, or sex, against construction companies owned

and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged

individuals in public and private transportation contracting

and the financial, credit, insurance, and bond markets;

(J) the impact on small business concerns owned and

controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged indi

viduals of—

(i) the issuance of a final order described in

paragraph (5) by a Federal court that suspends a pro

gram established under paragraph (1); or

(ii) the repeal or suspension of State or local dis

advantaged business enterprise programs; and

7a

(K) the impact of the requirement of paragraph (1),

and any program carried out to comply with paragraph (1),

on competition and the creation of jobs, including the

creation of jobs for socially and economically disadvan

taged individuals.

8a

APPENDIX C

Section 8 (d ) of The Small Business A ct

Section 8(d) of the Small Business Act, 15 U.S.C. 637(d)

(1994 & Supp. V 1999), as amended Pub. L. No. 106-554,

§ 1(a)(9) [Tit. VI, § 615(b), Tit. VIII, § 803], 114 Stat. 2763,

2763A-667, 2763A-701 to 2763A-703, provides in pertinent

part:

(d) Performance of contracts by small business con

cerns; inclusion o f required contract clause; subcon

tracting plans; contract eligibility; incentives; breach

of contract; review; report to Congress

(1) It is the policy of the United States that small busi

ness concerns, small business concerns owned and controlled

by veterans, small business concerns owned and controlled

by service-disabled veterans, qualified HUBZone small

business concerns, small business concerns owned and

controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged in

dividuals, and small business concerns owned and controlled

by women, shall have the maximum practicable opportunity

to participate in the performance of contracts let by any

Federal agency, including contracts and subcontracts for

subsystems, assemblies, components, and related services

for major systems. It is further the policy of the United

States that its prime contractors establish procedures to

ensure the timely payment of amounts due pursuant to the

terms of their subcontracts with small business concerns,

small business concerns owned and controlled by veterans,

small business concerns owned and controlled by service-

disabled veterans, qualified HUBZone small business con

cerns, small business concerns owned and controlled by

socially and economically disadvantaged individuals, and

small business concerns owned and controlled by women.

9a

(2) The clause stated in paragraph (3) shall be included in

all contracts let by any Federal agency except any contract

which—

(A) does not exceed the simplified acquisition threshold;

(B) including all subcontracts under such contracts will

be performed entirely outside of any State, territory, or

possession of the United States, the District of Columbia,

or the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico; or

(C) is for services which are personal in nature.

(3) The clause required by paragraph (2) shall be as

follows:

“(A) It is the policy of the United States that small busi

ness concerns, small business concerns owned and controlled

by veterans, small business concerns owned and controlled

by service-disabled veterans, qualified HUBZone small bus

iness concerns, small business concerns owned and con

trolled by socially and economically disadvantaged indi

viduals, and small business concerns owned and controlled

by women shall have the maximum practicable opportunity

to participate in the performance of contracts let by any

Federal agency, including contracts and subcontracts for

subsystems, assemblies, components, and related services

for major systems. It is further the policy of the United

States that its prime contractors establish procedures to

ensure the timely payment of amounts due pursuant to the

terms of their subcontracts with small business concerns,

small business concerns owned and controlled by veterans,

small business concerns owned and controlled by service-

disabled veterans, qualified HUBZone small business con

cerns, small business concerns owned and controlled by

socially and economically disadvantaged individuals, and

small business concerns owned and controlled by women.

10a

“(B) The contractor hereby agrees to carry out this po

licy in the awarding of subcontracts to the fullest extent con

sistent with the efficient performance of this contract. The

contractor further agrees to cooperate in any studies or sur

veys as may be conducted by the United States Small Busi

ness Administration or the awarding agency of the United

States as may be necessary to determine the extent of the

contractor’s compliance with this clause.

“(C) As used in this contract, the term ‘small business

concern’ shall mean a small business as defined pursuant to

section 3 of the Small Business Act [15 U.S.C. 632] and rele

vant regulations promulgated pursuant thereto. The term

‘small business concern owned and controlled by socially and

economically disadvantaged individuals’ shall mean a small

business concern—

“(i) which is at least 51 per centum owned by one or

more socially and economically disadvantaged individuals;

or, in the case of any publicly owned business, at least 51

per centum of the stock of which is owned by one or more

socially and economically disadvantaged individuals; and

“(ii) whose management and daily business operations

are controlled by one or more of such individuals.

“The contractor shall presume that socially and eco

nomically disadvantaged individuals include Black

Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans,

Asian Pacific Americans, and other minorities, or any

other individual found to be disadvantaged by the Ad

ministration pursuant to section 8(a) of the Small Busi

ness Act [15 U.S.C. 637(a)],

“(D) The term ‘small business concern owned and con

trolled by women’ shall mean a small business concern—

“(i) which is at least 51 per centum owned by one or

more women; or, in the case of any publicly owned busi-

11a

ness, at least 51 per centum of the stock of which is owned

by one or more women; and

“(ii) whose management and daily business operations

are controlled by one or more women.

“(E) The term ‘small business concern owned and con

trolled by veterans’ shall mean a small business concern—

“(i) which is at least 51 per centum owned by one or

more eligible veterans; or, in the case of any publicly

owned business, at least 51 per centum of the stock of

which is owned by one or more veterans; and

“(ii) whose management and daily business operations

are controlled by such veterans. The contractor shall

treat as veterans all individuals who are veterans within

the meaning of the term under section 632(q) of this title.

“(F) Contractors acting in good faith may rely on

written representations by their subcontractors regarding

their status as either a small business concern, small

business concern owned and controlled by veterans, small

business concerns owned and controlled by service-disabled

veterans, a small business concern owned and controlled by

socially and economically disadvantaged individuals, or a

small business concern owned and controlled by women.

“(G) In this contract, the term ‘qualified HUBZone

small business concern’ has the meaning given that term in

section 632(p) of this Title.”

(4)(A) Each solicitation of an offer for a contract to be let

by a Federal agency which is to be awarded pursuant to the

negotiated method of procurement and which may exceed

$1,000,000, in the case of a contract for the construction of

any public facility, or $500,000, in the case of all other con

tracts, shall contain a clause notifying potential offering com

panies of the provisions of this subsection relating to con-

12a

tracts awarded pursuant to the negotiated method of pro

curement.

(B) Before the award of any contract to be let, or any

amendment or modification to any contract let, by any

Federal agency which—

(i) is to be awarded, or was let, pursuant to the nego

tiated method of procurement,

(ii) is required to include the clause stated in para

graph (3),

(iii) may exceed $1,000,000 in the case of a contract

for the construction of any public facility, or $500,000 in

the case of all other contracts, and

(iv) which offers subcontracting possibilities,

the apparent successful offeror shall negotiate with the pro

curement authority a subcontracting plan which incorpo

rates the information prescribed in paragraph (6). The sub

contracting plan shall be included in and made a material

part of the contract.

(C) If, within the time limit prescribed in regulations of

the Federal agency concerned, the apparent successful of

feror fails to negotiate the subcontracting plan required by

this paragraph, such offeror shall become ineligible to be

awarded the contract. Prior compliance of the offeror with

other such subcontracting plans shall be considered by the

Federal agency in determining the responsibility of that

offeror for the award of the contract.

(D) No contract shall be awarded to any offeror unless

the procurement authority determines that the plan to be

negotiated by the offeror pursuant to this paragraph pro

vides the maximum practicable opportunity for small busi

ness concerns, qualified HUBZone small business concerns,

small business concerns owned and controlled by veterans,

13a

small business concerns owned and controlled by service-

disabled veterans, small business concerns owned and

controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged in

dividuals, and small business concerns owned and controlled

by women to participate in the performance of the contract.

(E) Notwithstanding any other provision of law, every

Federal agency, in order to encourage subcontracting oppor

tunities for small business concerns, small business concerns

owned and controlled by veterans, small business concerns

owned and controlled by service-disabled veterans, qualified

HUBZone small business concerns, and small business con

cerns owned and controlled by the socially and economically

disadvantaged individuals as defined in paragraph (3) of this

subsection and for small business concerns owned and con

trolled by women, is hereby authorized to provide such in

centives as such Federal agency may deem appropriate in

order to encourage such subcontracting opportunities as may

be commensurate with the efficient and economical per

formance of the contract: Provided, That, this subparagraph

shall apply only to contracts let pursuant to the negotiated

method of procurement.

(F) (i) Each contract subject to the requirements of this

paragraph or paragraph (5) shall contain a clause for the pay

ment of liquidated damages upon a finding that a prime con

tractor has failed to make a good faith effort to comply with

the requirem ents imposed on such contractor by this

subsection.

(ii) The contractor shall be afforded an opportunity to

demonstrate a good faith effort regarding compliance prior

to the contracting officer’s final decision regarding the im

position of damages and the amount thereof. The final deci

sion of a contracting officer regarding the contractor’s obli

gation to pay such damages, or the amounts thereof, shall be

14a

subject to the Contract Disputes Act of 1978 (41 U.S.C. 601-

613).

(iii) Each agency shall ensure that the goals offered by

the apparent successful bidder or offeror are attainable in

relation to—

(I) the subcontracting opportunities available to the

contractor, commensurate with the efficient and

economical performance of the contract;

(II) the pool of eligible subcontractors available to

fulfill the subcontracting opportunities; and

(III) the actual performance of such contractor in ful

filling the subcontracting goals specified in prior plans.

(G) The following factors shall be designated by the

Federal agency as significant factors for purposes of

evaluating offers for a bundled contract where the head of

the agency determines that the contract offers a significant

opportunity for subcontracting:

(i) A factor that is based on the ra te provided

under the subcontracting plan for small business partici

pation in the performance of the contract.

(ii) For the evaluation of past performance of an

offeror, a factor that is based on the extent to which the

offeror attained applicable goals for small business

participation in the performance of contracts.

(5)(A) Each solicitation of a bid for any contract to be let,

or any amendment or modification to any contract let, by any

Federal agency which—

(i) is to be av?arded pursuant to the formal

advertising method of procurement,

(ii) is required to contain the clause stated in

paragraph (3) of this subsection,

15a

(iii) may exceed $1,000,000 in the case of a contract

for the construction of any public facility, or $500,000, in

the case of all other contracts, and

(iv) offers subcontracting possibilities,

shall contain a clause requiring any bidder who is selected

to be awarded a contract to submit to the Federal agency

concerned a subcontracting plan which incorporates the

information prescribed in paragraph (6).

(B) If, within the time limit prescribed in regulations of

the Federal agency concerned, the bidder selected to be

awarded the contract fails to submit the subcontracting plan

required by this paragraph, such bidder shall become in

eligible to be awarded the contract. Prior compliance of the

bidder with other such subcontracting plans shall be con

sidered by the Federal agency in determining the res

ponsibility of such bidder for the award of the contract. The

subcontracting plan of the bidder awarded the contract shall

be included in and made a material part of the contract.

(6) Each subcontracting plan required under paragraph (4)

or (5) shall include—

(A) percentage goals for the utilization as sub

contractors of small business concerns, small business

concerns owned and controlled by veterans, small busi

ness concerns owned and controlled by service-disabled

veterans, qualified HUBZone small business concerns,

small business concerns owned and controlled by socially

and economically disadvantaged individuals, and small

business concerns owned and controlled by women;

(B) the name of an individual within the employ of the

offeror or bidder who will administer the subcontracting

program of the offeror or bidder and a description of the

duties of such individual;

16a

(C) a description of the efforts the offeror or bidder

will take to assure that small business concerns, small

business concerns owned and controlled by veterans,

small business concerns owned and controlled by service-

disabled veterans, qualified HUBZone small business

concerns, small business concerns owned and controlled

by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals,

and small business concerns owned and controlled by

women will have an equitable opportunity to compete for

subcontracts;

(D) assurances that the offeror or bidder will include

the clause required by paragraph (2) of this subsection in

all subcontracts which offer fu rther subcontracting

opportunities, and that the offeror or bidder will require

all subcontractors (except small business concerns) who

receive subcontracts in excess of $1,000,000 in the case of

a contract for the construction of any public facility, or in

excess of $500,000 in the case of all other contracts, to

adopt a plan similar to the plan required under paragraph

(4) or (5);

(E) assurances that the offeror or bidder will submit

such periodic reports and cooperate in any studies or

surveys as may be required by the Federal agency or the

Administration in order to determine the extent of com

pliance by the offeror or bidder with the subcontracting

plan; and

(F) a recitation of the types of records the successful

offeror or bidder will maintain to demonstrate procedures

which have been adopted to comply w ith the

requirements and goals set forth in this plan, including

the establishment of source lists of small business con

cerns, small business concerns owned and controlled by

veterans, small business concerns owned and controlled

by service-disabled veterans, qualified HUBZone small

17a

business concerns, small business concerns owned and

controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged

individuals, and small business concerns owned and

controlled by women; and efforts to identify and award

subcontracts to such small business concerns.

(7) The provisions of paragraphs (4), (5), and (6) shall not

apply to offerors or bidders who are small business concerns.

(8) The failure of any contractor or subcontractor to com

ply in good faith with—

(A) the clause contained in paragraph (3) of this sub

section, or

(B) any plan required of such contractor pursuant to the

authority of this subsection to be included in its contract or

subcontract,

shall be a material breach of such contract or subcontract.

18a

APPENDIX D

Department of Transportation Disadvantaged

Business Enterprise Regulations

The Department of Transportations Disadvantaged Bus

iness Enterprise Regulations, 64 Fed. Reg. 5127-5148 (1999),

to be codified at 49 C.F.R. Pt. 26, provide in pertinent part:

§ 26.1 What are the objectives o f this part?

This part seeks to achieve several objectives:

(a) To ensure nondiscrimination in the award and

administration of DOT-assisted contracts in the Depart

ment’s highway, transit, and airport financial assistance pro

grams;

(b) To create a level playing field on which DBEs can

compete fairly for DOT-assisted contracts;

(c) To ensure that the Department’s DBE program is

narrowly tailored in accordance with applicable law;

(d) To ensure that only firms that fully meet this part’s

eligibility standards are permitted to participate as DBEs;

(e) To help remove barriers to the participation of DBEs

in DOT-assisted contracts;

(f) To assist the development of firms that can compete

successfully in the marketplace outside the DBE program;

and

(g) To provide appropriate flexibility to recipients of

Federal financial assistance in establishing and providing

opportunities for DBEs.

19a

§ 26.3 To whom does this p a rt apply?

(a) If you are a recipient of any of the following types of

funds, this part applies to you:

(1) Federal-aid highway funds authorized under Titles I

(other than P art B) and V of the Intermodal Surface

Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA), Pub. L. 102-

240, 105 Stat. 1914, or Titles I, III, and V of the Trans

portation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), Pub. L.

105-178,112 Stat. 107.

(2) Federal transit funds authorized by Titles I, III, V

and VI of ISTEA, Pub. L. 102-240 or by Federal transit laws

in Title 49, U.S. Code, or Titles I, III, and V of the TEA-21,

Pub. L. 105-178.

(3) Airport funds authorized by 49 U.S.C. 47101, et seq.

(b) [Reserved]

(c) If you are letting a contract, and that contract is to be

performed entirely outside the United States, its territories

and possessions, Puerto Rico, Guam, or the Northern

Marianas Islands, this part does not apply to the contract.

(d) If you are letting a contract in which DOT financial

assistance does not participate, this part does not apply to

the contract.

20a

§ 26.5 What do the terms used in this part mean?

Contractor means one who participates, through a con

tract or subcontract (at any tier), in a DOT-assisted highway,

transit, or airport program.

Department or DOT means the U.S. D epartm ent of

Transportation, including the Office of the Secretary, the

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Federal

Transit Administration (FTA), and the Federal Aviation

Administration (FAA).

Disadvantaged business enterprise or DBE means a for-

profit small business concern—

(1) That is at least 51 percent owned by one or more

individuals who are both socially and economically disad

vantaged or, in the case of a corporation, in which 51 percent

of the stock is owned by one or more such individuals; and

(2) Whose management and daily business operations

are controlled by one or more of the socially and eco

nomically disadvantaged individuals who own it.

DOT-assisted contract means any contract between a

recipient and a contractor (at any tier) funded in whole or in

part with DOT financial assistance, including letters of credit

or loan guarantees, except a contract solely for the purchase

of land.

Good fa ith efforts means efforts to achieve a DBE goal or

other requirement of this part which, by their scope, inten

sity, and appropriateness to the objective, can reasonably be

expected to fulfill the program requirement.

21a

Personal net worth means the net value of the assets of an

individual remaining after total liabilities are deducted. An

individual’s personal net worth does not include: The indi

vidual’s ownership interest in an applicant or participating

DBE firm; or the individual’s equity in his or her primary

place of residence. An individual’s personal net worth

includes only his or her own share of assets held jointly or as

community property with the individual’s spouse.

Primary industry classification means the four digit

Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code designation

which best describes the primary business of a firm. The

SIC code designations are described in the Standard In

dustry Classification Manual. As the North American Indus

trial Classification System (NAICS) replaces the SIC

system, references to SIC codes and the SIC Manual are

deemed to refer to the NAICS manual and applicable codes.

The SIC Manual and the NAICS Manual are available

through the National Technical Information Service (NTIS)

of the U.S. Department of Commerce (Springfield, VA,

22261). NTIS also makes materials available through its

web site (www.ntis.gov/naics).

Race-conscious measure or program is one that is focused

specifically on assisting only DBEs, including women-owned

DBEs.

Race-neutral measure or program is one that is, or can be,

used to assist all small businesses. For the purposes of this

part, race-neutral includes gender-neutrality.

Recipient is any entity, public or private, to which DOT fi

nancial assistance is extended, whether directly or through

another recipient, through the programs of the FAA,

FHWA, or FTA, or who has applied for such assistance.

http://www.ntis.gov/naics

22a

Secretary means the Secretary of Transportation or

his/her designee.

Set-aside means a contracting practice restricting eligi

bility for the competitive award of a contract solely to DBE

firms.

Sm all Business Adm inistration or SB A means the

United States Small Business Administration.

Sm all business concern means, with respect to firms

seeking to participate as DBEs in DOT-assisted contracts, a

small business concern as defined pursuant to section 3 of

the Small Business Act and Small Business Administration

regulations implementing it (13 CFR part 121) that also does

not exceed the cap on average annual gross receipts speci

fied in § 26.65(b).

Socially and economically disadvantaged individual

means any individual who is a citizen (or lawfully admitted

permanent resident) of the United States and who is—

(1) Any individual who a recipient finds to be a socially

and economically disadvantaged individual on a case-by-case

basis.

(2) Any individual in the following groups, members of

which are rebuttably presumed to be socially and eco

nomically disadvantaged:

(i) “Black Americans,” which includes persons having

origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa;

(ii) “Hispanic Americans,” which includes persons of

Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, Central or South

American, or other Spanish or Portuguese culture or origin,

regardless of race;

28a

(iii) “Native Americans,” which includes persons who

are American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts, or Native

Hawaiians;

(iv) “Asian-Pacific Americans,” which includes persons

whose origins are from Japan, China, Taiwan, Korea, Burma

(Myanmar), Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia (Kampuchea),

Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Brunei,

Samoa, Guam, the U.S. Trust Territories of the Pacific

Islands (Republic of Palau), the Commonwealth of the

Northern Marianas Islands, Macao, Fiji, Tonga, Kirbati,

Juvalu, Nauru, Federated States of Micronesia, or Hong

Kong;

(v) “Subcontinent Asian Americans,” which includes

persons whose origins are from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh,

Bhutan, the Maldives Islands, Nepal or Sri Lanka;

(vi) Women;

(vii) Any additional groups whose members are

designated as socially and economically disadvantaged by

the SBA, at such time as the SBA designation becomes

effective.

Tribally-owned concern means any concern at least 51

percent owned by an Indian tribe as defined in this section.

You refers to a recipient, unless a statement in the text of

this part or the context requires otherwise (i.e., ‘You must

do XYZ’ means that recipients must do XYZ).

§ 26.7 What discriminatory actions are forbidden?

(a) You must never exclude any person from partici

pation in, deny any person the benefits of, or otherwise

discriminate against anyone in connection with the award

24a

and performance of any contract covered by this part on the

basis of race, color, sex, or national origin.

(b) In administering your DBE program, you must not,

directly or through contractual or other arrangements, use

criteria or methods of administration that have the effect of

defeating or substantially impairing accomplishment of the

objectives of the program with respect to individuals of a

particular race, color, sex, or national origin.

§ 26.13 What assurances must recipients and contrac

tors make?

(a) Each financial assistance agreement you sign with a

DOT operating administration (or a primary recipient) must

include the following assurance:

The recipient shall not discriminate on the basis of race,

color, national origin, or sex in the award and performance of

any DOT-assisted contract or in the administration of its

DBE program or the requirements of 49 CFR part 26. The

recipient shall take all necessary and reasonable steps under

49 CFR part 26 to ensure nondiscrimination in the award

and administration of DOT-assisted contracts. The recipi

ent’s DBE program, as required by 49 CFR part 26 and as

approved by DOT, is incorporated by reference in this agree

ment. Implementation of this program is a legal obligation

and failure to carry out its terms shall be treated as a vio

lation of this agreement. Upon notification to the recipient

of its failure to carry out its approved program, the De

partment may impose sanctions as provided for under part

26 and may, in appropriate cases, refer the m atter for en

forcement under 18 U.S.C. 1001 and/or the Program Fraud

Civil Remedies Act of 1986 (31 U.S.C. 3801 et seq.).

25a

(b) Each contract you sign with a contractor (and each

subcontract the prime contractor signs with a subcontractor)

must include the following assurance:

The contractor, sub recipient or subcontractor shall not

discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, or sex

in the performance of this contract. The contractor shall

carry out applicable requirements of 49 CFR part 26 in the

award and administration of DOT-assisted contracts. Fail

ure by the contractor to carry out these requirements is a

material breach of this contract, which may result in the

termination of this contract or such other remedy as the

recipient deems appropriate.

§ 26.15 How can recipients apply for exemptions or

waivers?

(a) You can apply for an exemption from any provision of

this part. To apply, you must request the exemption in

writing from the Office of the Secretary of Transportation,

FHWA, FTA, or FAA. The Secretary will grant the request

only if it documents special or exceptional circumstances, not

likely to be generally applicable, and not contemplated in

connection with the rulemaking that established this part,

that make your compliance with a specific provision of this

part impractical. You must agree to take any steps that the

Department specifies to comply with the intent of the provi

sion from which an exemption is granted. The Secretary will

issue a written response to all exemption requests.

(b) You can apply for a waiver of any provision of Sub

part B or C of this part including, but not limited to, any pro

visions regarding administrative requirements, overall goals,

contract goals or good faith efforts. Program waivers are for

the purpose of authorizing you to operate a DBE program

that achieves the objectives of this part by means that may

26a

differ from one or more of the requirements of Subpart B or

C of this part. To receive a program waiver, you must follow

these procedures:

(1) You must apply through the concerned operating

administration. The application must include a specific pro

gram proposal and address how you will meet the criteria of

paragraph (b)(2) of this section. Before submitting your

application, you must have had public participation in devel

oping your proposal, including consultation with the DBE

community and at least one public hearing. Your application

must include a summary of the public participation process

and the information gathered through it.

(2) Your application must show that—

(i) There is a reasonable basis to conclude that you could

achieve a level of DBE participation consistent with the

objectives of this part using different or innovative means

other than those that are provided in subpart B or C of this

part;

(ii) Conditions in your jurisdiction are appropriate for

implementing the proposal;

(iii) Your proposal would prevent discrimination against

any individual or group in access to contracting opportuni

ties or other benefits of the program; and

(iv) Your proposal is consistent with applicable law and

program requirements of the concerned operating admini

stration’s financial assistance program.

(3) The Secretary has the authority to approve your

application. If the Secretary grants your application, you

may administer your DBE program as provided in your pro

posal, subject to the following conditions:

27a

(i) DBE eligibility is determined as provided in subparts

D and E of this part, and DBE participation is counted as

provided in § 26.49;

(ii) Your level of DBE participation continues to be con

sistent with the objectives of this part;

(iii) There is a reasonable limitation on the duration of

your modified program; and

(iv) Any other conditions the Secretary makes on the

grant of the waiver.

(4) The Secretary may end a program waiver at any time

and require you to comply with this part’s provisions. The

Secretary may also extend the waiver, if he or she deter

mines that all requirements of paragraphs (b)(2) and (3) of

this section continue to be met. Any such extension shall be

for no longer than period originally set for the duration of

the program.

Subpart B—Administrative Requirements for DBE Pro

grams for Federally-Assisted Contracting

§ 26.21 Who must have a DBE program?

(a) If you are in one of these categories and let DOT-

assisted contracts, you must have a DBE program meeting

the requirements of this part:

(1) All FHWA recipients receiving funds authorized by a

statute to which this part applies;

(2) FTA recipients that receive $250,000 or more in FTA

planning, capital, and/or operating assistance in a Federal

fiscal year;

(3) FAA recipients that receive a grant of $250,000 or

more for airport planning or development.

28a

(b) (1) You must submit a DBE program conforming to this

part by August 31, 1999 to the concerned operating admin

istration (OA). Once the OA has approved your program,

the approval counts for all of your DOT-assisted programs

(except th a t goals are reviewed and approved by the

particular operating administration that provides funding for

your DOT-assisted contracts).

(2) You do not have to submit regular updates of

your DBE programs, as long as you remain in compliance.

However, you must submit significant changes in the pro

gram for approval.

(c) You are not eligible to receive DOT financial assis

tance unless DOT has approved your DBE program and you

are in compliance with it and this part. You must continue to

carry out your program until all funds from DOT financial

assistance have been expended.

* * * * *

§ 26.29 What prompt payment m echanism s must

recipients have?

(a) You must establish, as part of your DBE program, a

contract clause to require prime contractors to pay subcon

tractors for satisfactory performance of their contracts no

later than a specific number of days from receipt of each

payment you make to the prime contractor. This clause

must also require the prompt return of retainage payments

from the prime contractor to the subcontractor within a

specific number of days after the subcontractor’s work is

satisfactorily completed.

(1) This clause may provide for appropriate penal ties for

failure to comply, the terms and conditions of which you set.

29a

(2) This clause may also provide that any delay or post

ponement of payment among the parties may take place only

for good cause, with your prior written approval.

(b) You may also establish, as part of your DBE pro

gram, any of the following additional mechanisms to ensure

prompt payment:

(1) A contract clause that requires prime contractors to

include in their subcontracts language providing that prime

contractors and subcontractors will use appropriate alter

native dispute resolution mechanisms to resolve payment

disputes. You may specify the nature of such mechanisms.

(2) A contract clause providing that the prime contractor

will not be reimbursed for work performed by subcon

tractors unless and until the prime contractor ensures that

the subcontractors are promptly paid for the work they have

performed.

(3) Other mechanisms, consistent with this part and

applicable state and local law, to ensure that DBEs and other

contractors are fully and promptly paid.

§ 26.31 W hat requirem ents p e rta in to the DBE direc

tory?

You must maintain and make available to interested per

sons a directory identifying all firms eligible to participate as

DBEs in your program. In the listing for each firm, you

must include its address, phone number, and the types of

work the firm has been certified to perform as a DBE. You

must revise your directory at least annually and make up

dated information available to contractors and the public on

request.

30a

§ 26.33 What steps must a recipient take to address

overconcentration of DBEs in certain types o f work?

(a) If you determine tha t DBE firms are so over

concentrated in a certain type of work as to unduly burden

the opportunity of non-DBE firms to participate in this type

of work, you must devise appropriate measures to address

this overconcentration.

(b) These measures may include the use of incentives,

technical assistance, business development programs,

mentor-protege programs, and other appropriate measures

designed to assist DBEs in performing work outside of the

specific field in which you have determined that non-DBEs

are unduly burdened. You may also consider varying your

use of contract goals, to the extent consistent with § 26.51, to

ensure that non-DBEs are not unfairly prevented from com

peting for subcontracts.

(c) You must obtain the approval of the concerned DOT

operating administration for your determination of over

concentration and the measures you devise to address it.

Once approved, the measures become part of your DBE

program.

* * * * *

Subpart C—Goals, Good Faith Efforts, and Counting

§ 26.41 What is the role o f the statutory 10 percent

goal in this program?

(a) The statutes authorizing this program provide that,

except to the extent the Secretary determines otherwise,

not less than 10 percent of the authorized funds are to be

expended with DBEs.

31a

(b) This 10 percent goal is an aspirational goal at the

national level, which the Department uses as a tool in

evaluating and monitoring DBEs’ opportunities to partici

pate in DOT-assisted contracts.

(c) The national 10 percent goal does not authorize or

require recipients to set overall or contract goals at the 10

percent level, or any other particular level, or to take any

special administrative steps if their goals are above or below

10 percent.

§ 26.43 Can recipients use set-asides or quotas as

part of this program?

(a) You are not permitted to use quotas for DBEs on

DOT-assisted contracts subject to this part.

(b) You may not set-aside contracts for DBEs on DOT-

assisted contracts subject to this part, except that, in limited

and extreme circumstances, you may use set-asides when no

other method could be reasonably expected to redress

egregious instances of discrimination.

§ 26.45 How do recipients set overall goals?

(a) You must set an overall goal for DBE participation in

your DOT-assisted contracts.

(b) Your overall goal must be based on demonstrable

evidence of the availability of ready, willing and able DBEs

relative to all businesses ready, willing and' able to partici

pate on your DOT-assisted contracts (hereafter, the “rela

tive availability of DBEs”)- The goal must reflect your

determination of the level of DBE participation you would

expect absent the effects of discrimination. You cannot

simply rely on either the 10 percent national goal, your pre

vious overall goal or past DBE participation rates in your

32a

program without reference to the relative availability of

DBEs in your market.

(c) Step 1. You must begin your goal setting process by

determining a base figure for the relative availability of

DBEs. The following are examples of approaches that you

may take toward determining a base figure. These examples

are provided as a starting point for your goal setting process.

Any percentage figure derived from one of these examples

should be considered a basis from which you begin when

examining all evidence available in your jurisdiction. These

examples are not intended as an exhaustive list. Other

methods or combinations of methods to determine a base fig

ure may be used, subject to approval by the concerned

operating administration.

(1) Use DBE Directories and Census Bureau Data.

Determine the number of ready, willing and able DBEs in

your m arket from your DBE directory. Using the Census

Bureau’s County Business Pattern (CBP) data base, deter

mine the number of all ready, willing and able businesses

available in your market that perform work in the same SIC

codes. (Information about the CBP data base may be

obtained from the Census Bureau at their web site,

www.census.gov/epcd/cbp/view/cbpview.html.) Divide the

number of DBEs by the number of all businesses to derive a

base figure for the relative availability of DBEs in your

market.

(2) Use a bidders list. Determine the number of DBEs

that have bid or quoted on your DOT-assisted prime con

tracts or subcontracts in the previous year. Determine the

number of all businesses that have bid or quoted on prime or

subcontracts in the same time period. Divide the number of

DBE bidders and quoters by the number for all businesses

http://www.census.gov/epcd/cbp/view/cbpview.html

33a

to derive a base figure for the relative availability of DBEs

in your market.

(3) Use data from a disparity study. Use a percentage

figure derived from data in a valid, applicable disparity

study.

(4) Use the goal o f another DOT recipient. If another

DOT recipient in the same, or substantially similar, market

has set an overall goal in compliance with this rule, you may

use that goal as a base figure for your goal.

(5) Alternative methods. Subject to the approval of the

DOT operating administration, you may use other methods

to determine a base figure for your overall goal. Any meth

odology you choose must be based on demonstrable evidence

of local market conditions and be designed to ultimately

attain a goal tha t is rationally related to the relative

availability of DBEs in your market.

(d) Step 2. Once you have calculated a base figure, you

must examine all of the evidence available in your juris

diction to determine what adjustment, if any, is needed to

the base figure in order to arrive at your overall goal.

(1) There are many types of evidence that must be

considered when adjusting the base figure. These include:

(i) The current capacity of DBEs to perform work in

your DOT-assisted contracting program, as measured by the

volume of work DBEs have performed in recent years;

(ii) Evidence from disparity studies conducted anywhere

within your jurisdiction, to the extent it is not already ac

counted for in your base figure; and

34a

(iii) If your base figure is the goal of another recipient,

you must adjust it for differences in your local market and

your contracting program.

(2) You may also consider available evidence from

related fields that affect the opportunities for DBEs to form,

grow and compete. These include, but are not limited to:

(i) Statistical disparities in the ability of DBEs to get

the financing, bonding and insurance required to participate

in your program;

(ii) Data on employment, self-employment, education,

training and union apprenticeship programs, to the extent

you can relate it to the opportunities for DBEs to perform in

your program.

(3) If you attempt to make an adjustment to your base

figure to account for the continuing effects of past discrimi

nation (often called the “but for” factor) or the effects of an

ongoing DBE program, the adjustment must be based on

demonstrable evidence that is logically and directly related

to the effect for which the adjustment is sought.

(e) Once you have determined a percentage figure in

accordance with paragraphs (c) and (d) of this section, you

should express your overall goal as follows:

(1) If you are an FHWA recipient, as a percentage of all

Federal-aid highway funds you will expend in FHWA-as-

sisted contracts in the forthcoming fiscal year;

(2) If you are an FT A or FAA recipient, as a percentage

of all FTA or FAA funds (exclusive of FTA funds to be used

for the purchase of transit vehicles) that you will expend in

FTA or FAA-assisted contracts in the forthcoming fiscal

year. In appropriate cases, the FTA or FAA Administrator

may permit you to express your overall goal as a percentage

35a

of funds for a particular grant or project or group of grants

and/or projects.

(f)(1) If you set overall goals on a fiscal year basis, you

must submit them to the applicable DOT operating admini

stration for review on August 1 of each year, unless the

Administrator of the concerned operating administration

establishes a different submission date.

(2) If you are an FTA or FAA recipient and set your

overall goal on a project or grant basis, you must submit the

goal for review at a time determined by the FTA or FAA

Administrator.

(3) You must include with your overall goal submission a

description of the methodology you used to establish the

goal, including your base figure and the evidence with which

it was calculated, and the adjustments you made to the base

figure and the evidence relied on for the adjustments. You

should also include a summary listing of the relevant avail

able evidence in your jurisdiction and, where applicable, an

explanation of why you did not use that evidence to adjust

your base figure. You must also include your projection of

the portions of the overall goal you expect to meet through

race-neutral and race-conscious measures, respectively (see

§ 26.51(c)).

(4) You are not required to obtain prior operating ad

ministration concurrence with the your overall goal. How

ever, if the operating administration’s review suggests that

your overall goal has not been correctly calculated, or that

your method for calculating goals is inadequate, the oper

ating administration may, after consulting with you, adjust

your overall goal or require that you do so. The adjusted

overall goal is binding on you.

36a

(5) If you need additional time to collect data or take

other steps to develop an approach to setting overall goals,

you may request the approval of the concerned operating

administration for an interim goal and/or goal-setting mecha

nism. Such a mechanism must:

(i) Reflect the relative availability of DBEs in your local

market to the maximum extent feasible given the data avail

able to you; and

(ii) Avoid imposing undue burdens on non-DBEs.

(g) In establishing an overall goal, you must provide for

public participation. This public participation must include:

(1) Consultation with minority, women’s and general

contractor groups, community organizations, and other offi

cials or organizations which could be expected to have in

formation concerning the availability of disadvantaged and

non-disadvantaged businesses, the effects of discrimination

on opportunities for DBEs, and your efforts to establish a

level playing field for the participation of DBEs.

(2) A published notice announcing your proposed overall

goal, informing the public that the proposed goal and its

rationale are available for inspection during normal business

hours at your principal office for 30 days following the date

of the notice, and informing the public that you and the

Department will accept comments on the goals for 45 days

from the date of the notice. The notice must include ad

dresses to which comments may be sent, and you must pub

lish it in general circulation media and available minority-

focused media and trade association publications.

(h) Your overall goals must provide for participation by

all certified DBEs and must not be subdivided into group-

specific goals.

37a

§ 26.47 Can recipients be penalized for failing to m eet

overall goals?

(a) You cannot be penalized, or treated by the Depart

ment as being in noncompliance with this rale, because your

DBE participation falls short of your overall goal, unless you

have failed to administer your program in good faith.

(b) If you do not have an approved DBE program or

overall goal, or if you fail to implement your program in good

faith, you are in noncompliance with this part.

§ 26.51 What means do recipients use to m eet overall

goals?

(a) You must meet the maximum feasible portion of your

overall goal by using race-neutral means of facilitating DBE

participation. Race-neutral DBE participation includes any

time a DBE wins a prime contract through customary com

petitive procurement procedures, is awarded a subcontract

on a prime contract that does not carry a DBE goal, or even

if there is a DBE goal, wins a subcontract from a prime

contractor that did not consider its DBE status in making

the award (e.g., a prime contractor that uses a strict low bid

system to award subcontracts).

(b) Race-neutral means include, but are not limited to,

the following:

(1) Arranging solicitations, times for the presentation of

bids, quantities, specifications, and delivery schedules in

ways that facilitate DBE, and other small businesses, par

ticipation (e.g., unbundling large contracts to make them

more accessible to small businesses, requiring or encourag

ing prime contractors to subcontract portions of work that

they might otherwise perform with their own forces);

38a

(2) Providing assistance in overcoming limitations such

as inability to obtain bonding or financing (e.g., by such

means as simplifying the bonding process, reducing bonding

requirements, eliminating the impact of surety costs from

bids, and providing services to help DBEs, and other small

businesses, obtain bonding and financing);

(3) Providing technical assistance and other services;

(4) Carrying out information and communications pro

grams on contracting procedures and specific contract op

portunities (e.g., ensuring the inclusion of DBEs, and other

small businesses, on recipient mailing lists for bidders; en

suring the dissemination to bidders on prime contracts of

lists of potential subcontractors; provision of information in

languages other than English, where appropriate);

(5) Implementing a supportive services program to de

velop and improve immediate and long-term business man

agement, record keeping, and financial and accounting capa

bility for DBEs and other small businesses;

(6) Providing services to help DBEs, and other small

businesses, improve long-term development, increase op

portunities to participate in a variety of kinds of work, han

dle increasingly significant projects, and achieve eventual

self-sufficiency;

(7) Establishing a program to assist new, start-up firms,

particularly in fields in which DBE participation has histori

cally been low;

(8) Ensuring distribution of your DBE directory,

through print and electronic means, to the widest feasible

universe of potential prime contractors; and

39a

(9) Assisting DBEs, and other small businesses, to de

velop their capability to utilize emerging technology and con

duct business through electronic media.

(c) Each time you submit your overall goal for review by

the concerned operating administration, you must also sub

mit your projection of the portion of the goal that you expect

to meet through race-neutral means and your basis for that

projection. This projection is subject to approval by the

concerned operating administration, in conjunction with its

review of your overall goal.

(d) You must establish contract goals to meet any por

tion of your overall goal you do not project being able to

meet using race-neutral means.

(e) The following provisions apply to the use of contract

goals:

(1) You may use contract goals only on those DOT-as-

sisted contracts that have subcontracting possibilities.

(2) You are not required to set a contract goal on every

DOT-assisted contract. You are not required to set each

contract goal at the same percentage level as the overall

goal. The goal for a specific contract may be higher or lower

than that percentage level of the overall goal, depending on

such factors as the type of work involved, the location of the

work, and the availability of DBEs for the work of the parti

cular contract. However, over the period covered by your

overall goal, you must set contract goals so that they will

cumulatively result in meeting any portion of your overall

goal you do not project being able to meet through the use of

race-neutral means.

(3) Operating administration approval of each contract

goal is not necessarily required. However, operating admini-

40a

strations may review and approve or disapprove any con

tract goal you establish.

(4) Your contract goals must provide for participation by

all certified DBEs and must not be subdivided into group-

specific goals.

(f) To ensure that your DBE program continues to be

narrowly tailored to overcome the effects of discrimination,

you must adjust your use of contract goals as follows:

(1) If your approved projection under paragraph (c) of

this section estimates that you can meet your entire overall

goal for a given year through race-neutral means, you must

implement your program without setting contract goals

during that year.

Example to Paragraph (f)(1): Your overall goal for Year

I is 12 percent. You estimate that you can obtain 12 percent

or more DBE participation through the use of race-neutral

measures, without any use of contract goals. In this case,

you do not set any contract goals for the contracts that will

be performed in Year I.

(2) If, during the course of any year in which you are

using contract goals, you determine that you will exceed

your overall goal, you must reduce or eliminate the use of

contract goals to the extent necessary to ensure that the use

of contract goals does not result in exceeding the overall

goal. If you determine that you will fall short of your overall

goal, then you must make appropriate modifications in your

use of race-neutral and/or race-conscious measures to allow

you to meet the overall goal.

Example to Paragraph (f)(2): In Year II, your overall

goal is 12 percent. You have estimated that you can obtain 5

percent DBE participation through use of race-neutral

41a

measures. You therefore plan to obtain the remaining 7 per

cent participation through use of DBE goals. By September,

you have already obtained 11 percent DBE participation for

the year. For contracts let during the remainder of the year,

you use contract goals only to the extent necessary to obtain

an additional one percent DBE participation. However, if

you determine in September that your participation for the

year is likely to be only 8 percent total, then you would in

crease your use of race-neutral and/or race-conscious means

during the remainder of the year in order to achieve your

overall goal.

(3) If the DBE participation you have obtained by race-

neutral means alone meets or exceeds your overall goals for

two consecutive years, you are not required to make a pro

jection of the amount of your goal you can meet using such

means in the next year. You do not set contract goals on any

contracts in the next year. You continue using only race-

neutral means to meet your overall goals unless and until

you do not meet your overall goal for a year.

Example to Paragraph (f)(3): Your overall goal for Year

I and Year II is 10 percent. The DBE participation you

obtain through race-neutral measures alone is 10 percent or

more in each year. (For this purpose, it does not matter

whether you obtained additional DBE participation through

using contract goals in these years.) In Year III and follow

ing years, you do not need to make a projection under para

graph (c) of this section of the portion of your overall goal

you expect to meet using race-neutral means. You simply

use race-neutral means to achieve your overall goals. How

ever, if in Year VI your DBE participation falls short of your

overall goal, then you must make a paragraph (c) projection

for Year VII and, if necessary, resume use of contract goals

in that year.

42a

(4) If you obtain DBE participation that exceeds your

overall goal in two consecutive years through the use of

contract goals (i.e., not through the use of race-neutral

means alone), you must reduce your use of contract goals

proportionately in the following year.

Example to Paragraph (f)(i): In Years I and II, your

overall goal is 12 percent, and you obtain 14 and 16 percent

DBE participation, respectively. You have exceeded your

goals over the two-year period by an average of 25 percent.

In Year III, your overall goal is again 12 percent, and your

paragraph (c) projection estimates that you will obtain 4 per

cent DBE participation through race-neutral means and 8

percent through contract goals. You then reduce the con

tract goal projection by 25 percent (i.e., from 8 to 6 percent)

and set contract goals accordingly during the year. If in

Year III you obtain 11 percent participation, you do not use

this contract goal adjustment mechanism for Year IV, be

cause there have not been two consecutive years of ex

ceeding overall goals.

(g) In any year in which you project meeting part of your

goal through race-neutral means and the remainder through

contract goals, you must maintain data separately on DBE

achievements in those contracts with and without contract

goals, respectively. You must report this data to the con

cerned operating administration as provided in § 26.11.

§ 26.53 What are the good faith efforts procedures

recipients follow in situations where there are contract

goals?

(a) When you have established a DBE contract goal, you

must award the contract only to a bidder/offeror who

makes good faith efforts to meet it. You must determine

43a

that a bidder/offeror has made good faith efforts if the

bidder/offeror does either of the following things:

(1) Documents that it has obtained enough DBE partici

pation to meet the goal; or

(2) Documents that it made adequate good faith efforts

to meet the goal, even though it did not succeed in obtaining

enough DBE participation to do so. If the bidder/offeror

does document adequate good faith efforts, you must not

deny a-ward of the contract on the basis that the bidder/

offeror failed to meet the goal. See Appendix A of this part

for guidance in determining the adequacy of a bidder/

offeror’s good faith efforts.

(b) In your solicitations for DOT-assisted contracts for

which a contract goal has been established, you must require

the following:

(1) Award of the contract will be conditioned on meeting

the requirements of this section;

(2) All bidders/offerors will be required to submit the

following information to the recipient, at the time provided

in paragraph (b)(3) of this section:

(i) The names and addresses of DBE firms that will par

ticipate in the contract;

(ii) A description of the work that each DBE will per

form;

(iii) The dollar amount of the participation of each DBE

firm participating;

(iv) W ritten documentation of the bidder/offeror’s com

mitment to use a DBE subcontractor whose participation it

submits to meet a contract goal;

44a

(v) Written confirmation from the DBE that it is partici

pating in the contract as provided in the prime contractor’s

commitment; and

(vi) If the contract goal is not met, evidence of good faith

efforts (see Appendix A of this part); and

(3) At your discretion, the bidder/offeror must pre

sent the information required by paragraph (b)(2) of this

section—

(i) Under sealed bid procedures, as a m atter of respon

siveness, or with initial proposals, under contract negotiation

procedures; or

(ii) At any time before you commit yourself to the per

formance of the contract by the bidder/offeror, as a m atter of

responsibility.

(c) You must make sure all information is complete and

accurate and adequately documents the bidder/offeror’s good

faith efforts before committing yourself to the performance

of the contract by the bidder /offeror.

(d) If you determine that the apparent successful bidder/

offeror has failed to meet the requirements of paragraph (a)

of this section, you must, before awarding the contract,

provide the bidder/offeror an opportunity for administrative

reconsideration.

(1) As part of this reconsideration, the bidder/offeror

must have the opportunity to provide written documentation

or argument concerning the issue of whether it met the goal

or made adequate good faith efforts to do so.

(2) Your decision on reconsideration must be made by an

official who did not take part in the original determination

45a

that the bldder/offeror failed to meet the goal or make ade

quate good faith efforts to do so.

(3) The bidder/offeror must have the opportunity to

meet in person with your reconsideration official to discuss

the issue of whether it met the goal or made adequate good

faith efforts to do so.

(4) You must send the bidder/offeror a written decision

on reconsideration, explaining the basis for finding that the

bidder did or did not meet the goal or make adequate good

faith efforts to do so.

(5) The result of the reconsideration process is not ad

ministratively appealable to the Department of Transporta

tion.

(e) In a “design-build” or “turnkey” contracting situa

tion, in which the recipient lets a master contract to a con

tractor, who in turn lets subsequent subcontracts for the

work of the project, a recipient may establish a goal for the

project. The master contractor then establishes contract

goals, as appropriate, for the subcontracts it lets. Recipients

must maintain oversight of the master contractor’s activities

to ensure that they are conducted consistent with the re

quirements of this part.

(f) (1) You must require that a prime contractor not te r

minate for convenience a DBE subcontractor listed in re

sponse to paragraph (b)(2) of this section (or an approved

substitute DBE firm) and then perform the work of the ter

minated subcontract with its own forces or those of an

affiliate, without your prior written consent.

(2) When a DBE subcontractor is terminated, or fails to

complete its work on the contract for any reason, you must

require the prime contractor to make good faith efforts to

46a

find another DBE subcontractor to substitute for the ori

ginal DBE. These good faith efforts shall be directed at

finding another DBE to perform at least the same amount of

work under the contract as the DBE that was terminated, to

the extent needed to meet the contract goal you established

for the procurement.

(3) You must include in each prime contract a provision

for appropriate administrative remedies that you will invoke

if the prime contractor fails to comply with the requirements

of this section.