Greenberg Succeeds Marshall As NAACP's Chief Legal Council

Press Release

October 14, 1961

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Greenberg Succeeds Marshall As NAACP's Chief Legal Council, 1961. 7d10faea-bd92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ae9856dc-20cd-4cb1-80eb-37eb44fded6d/greenberg-succeeds-marshall-as-naacps-chief-legal-council. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

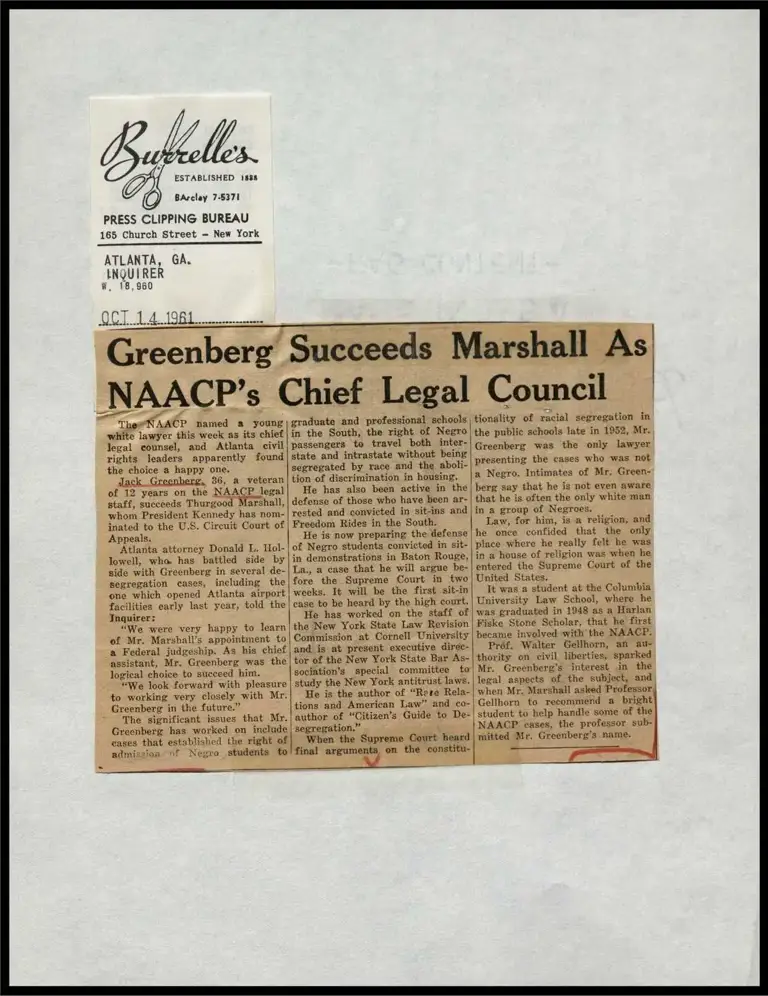

ESTABLISHED 1898

oO

PRESS CLIPPING BUREAU

165 Church Street - New York

ATLANTA, GA.

INQUIRER

W, 18,960

BArclay 7-537!

QOCT.14. 1981

Greenberg Succeeds Marshall As

NAACP’s Chief Legal Council

‘AMCP named a young

white lawyer this week as its chief

Jegal counsel, and Atlanta civil

rights leaders apparently found

the choice a happy one,

: 36, a veteran

of 12 years on the NAACP legal

staff, succeeds Thurgood Marshall,

whom President Kennedy has nom-

inated to the U.S. Circuit Court of

Appeals.

‘Atlanta attorney Donald L. Hol-

lowell, wha has battled side by

side with Greenberg in several de-

segregation cases, including the

‘one which opened Atlanta airport

facilities early last year, told the

Inquirer:

“We were very happy to learn

of Mr. Marshall's appointment to

‘a Federal judgeship. As his chief

assistant, Mr. Greenberg was the

logical choice to succeed him.

“We look forward with pleasure

to working very closely with Mr.

Greenberg in the future.”

The significant issues that Mr.

Greenberg has worked on inclade

cases that established the right of

admission of Negro students to

graduate and professional schools

in the South, the right of Negro

passengers to travel both inter

state and intrastate without being

segregated by race and the aboli-

tion of discrimination in housing.

He has also been active in the

defense of those who have been ar-

rested and convicted in sit-ins and

Freedom Rides in the South,

He is now preparing the defense

of Negro students convicted in sit-

in demonstrations in Baton Rouge,

La. a case that he will argue be-

fore the Supreme Court in two

weeks. It will be the first sit-in

case to be heard by the high court,

He has worked on the staff of

the New York State Law Revision

Commission at Cornell University

and_is at present executive direc-

tor of the New York State Bar As-

sociation’s special committee to

study the New York antitrust laws.

He is the author of “Rete Rela-

tions and American Law” and co-

author of “Citizen’s Guide to De-

segregation.” z

‘When the Supreme Court heard

final arguments, on the constitu-

avd

=

tionality of racial segregation in

the public schools late in 1952, Mr.

Greenberg was the only lawyer

presenting the cases who was not

a Negro. Intimates of Mr, Green-

berg say that he is not even aware

that he is often the only white man

in a group of Negroes.

w, for him, is-a religion, and

he once confided that the only

place where he really felt he was

in a house of religion was when he

entered the Supreme Court of the

United States.

Tt was a student at the Columbia

University Law School, where he

was graduated in 1948 as a Harlan

Fiske Stone Scholar, that he first

became involyed with’ the NAACP.

Préf, Walter Gellhorn, an av-

student to help handle some of the

NAACP’ cases, the professor sub-

mitted Mr. Greenberg's name.