LDF Suit Charges Bias in Federally Aided County Nursing Home in Alabama

Press Release

November 4, 1966

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 4. LDF Suit Charges Bias in Federally Aided County Nursing Home in Alabama, 1966. 60f0f54a-b792-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ae9fdb89-7709-40e6-bb28-27f5de67d396/ldf-suit-charges-bias-in-federally-aided-county-nursing-home-in-alabama. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

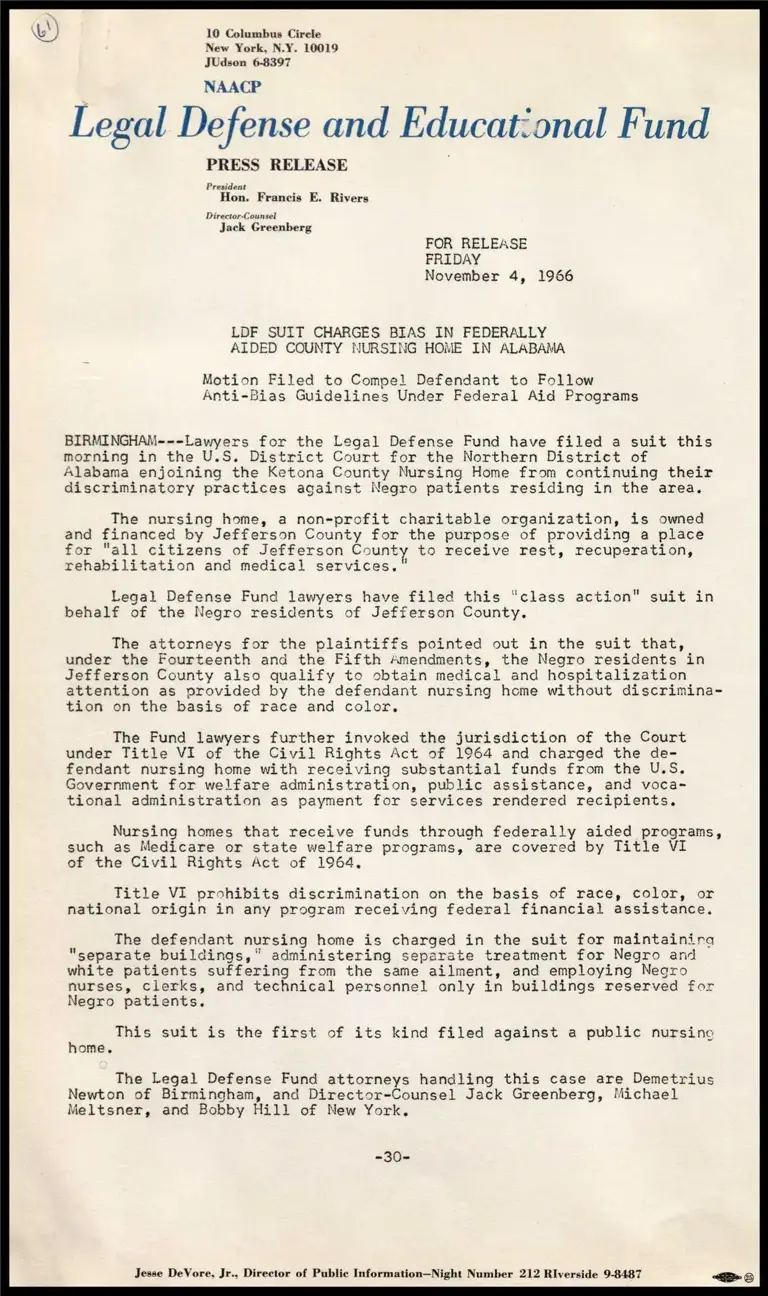

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

JUdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal Defense and Educat:onal Fund

PRESS RELEASE

OFieun Beanie Es Rivers

Director-Counsel

Jack Greenberg

FOR RELEASE

FRIDAY

November 4, 1966

LDF SUIT CHARGES BIAS IN FEDERALLY

AIDED COUNTY NURSING HOME IN ALABAMA

Motion Filed to Compel Defendant to Follow

Anti-Bias Guidelines Under Federal Aid Programs

BIRMINGHAM---Lawyers for the Legal Defense Fund have filed a suit this

morning in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of

Alabama enjoining the Ketona County Nursing Home from continuing their

discriminatory practices against Negro patients residing in the area.

The nursing home, a non-profit charitable organization, is owned

and financed by Jefferson County for the purpose of providing a place

for "all citizens of Jefferson County to receive rest, recuperation,

rehabilitation and medical services."

Legal Defense Fund lawyers have filed this “class action" suit in

behalf of the Negro residents of Jefferson County.

The attorneys for the plaintiffs pointed out in the suit that,

under the Fourteenth and the Fifth Amendments, the Negro residents in

Jefferson County also qualify to obtain medical and hospitalization

attention as provided by the defendant nursing home without discrimina-

tion on the basis of race and color.

The Fund lawyers further invoked the jurisdiction of the Court

under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and charged the de-

fendant nursing home with receiving substantial funds from the U.S.

Government for welfare administration, public assistance, and voca-~

tional administration as payment for services rendered recipients.

Nursing homes that receive funds through federally aided programs,

such as Medicare or state welfare programs, are covered by Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

Title VI prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or

national origin in any program receiving federal financial assistance.

The defendant nursing home is charged in the suit for maintainira

"separate buildings,” administering separate treatment for Negro and

white patients suffering from the same ailment, and employing Negro

nurses, clerks, and technical personnel only in buildings reserved for

Negro patients.

This suit is the first of its kind filed against a public nursince

home.

The Legal Defense Fund attorneys handling this case are Demetrius

Newton of Birmingham, and Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg, Michael

Meltsner, and Bobby Hill of New York.

-30-

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 Riverside 9-8487 Ss