Milton v. Weinberg Plaintiff-Appellant's Brief and Appendix

Public Court Documents

August 27, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Milton v. Weinberg Plaintiff-Appellant's Brief and Appendix, 1987. 959202d0-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aea78233-9dbc-4092-9e1a-8a84dcbc6fa0/milton-v-weinberg-plaintiff-appellants-brief-and-appendix. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

LORD, B I 5 S E L L & B R O O K

115 S O U T H L A S A L L E S T R E E T

C H I C A G O , I L L I N O I S 6 0 6 0 3

(3 1 * ) 4 4 3 - 0 7 0 0

C A B ME - LO W IR C O C G O

T f L E X : 2 5 - 3 0 7 0

A T L A N T A O F F IC E

T H E E Q U IT A B L E B U IL D IN G

IO O P E A C H T R E E S T R E E T , S U IT E 2 6 4 0

A T L A N T A , G E O R G IA 3 0 3 0 3

L O S A N G E L E S O F F IC E

3 2 5 0 W IL S H IR E B O U L E V A R D

L O S A N G E L E S , C A L IF O R N IA 9 0 0 1 0

(2 1 3 ) 4 8 7 - 7 0 6 - 4

T E L E X : 1 8 -1 1 3 5

D I A N E f- J E N N I N G S

£312) 443.-0694

(-40-4) 5 2 1 - 7 7 9 0

T E L E X : 5 - 4 3 7 0 7

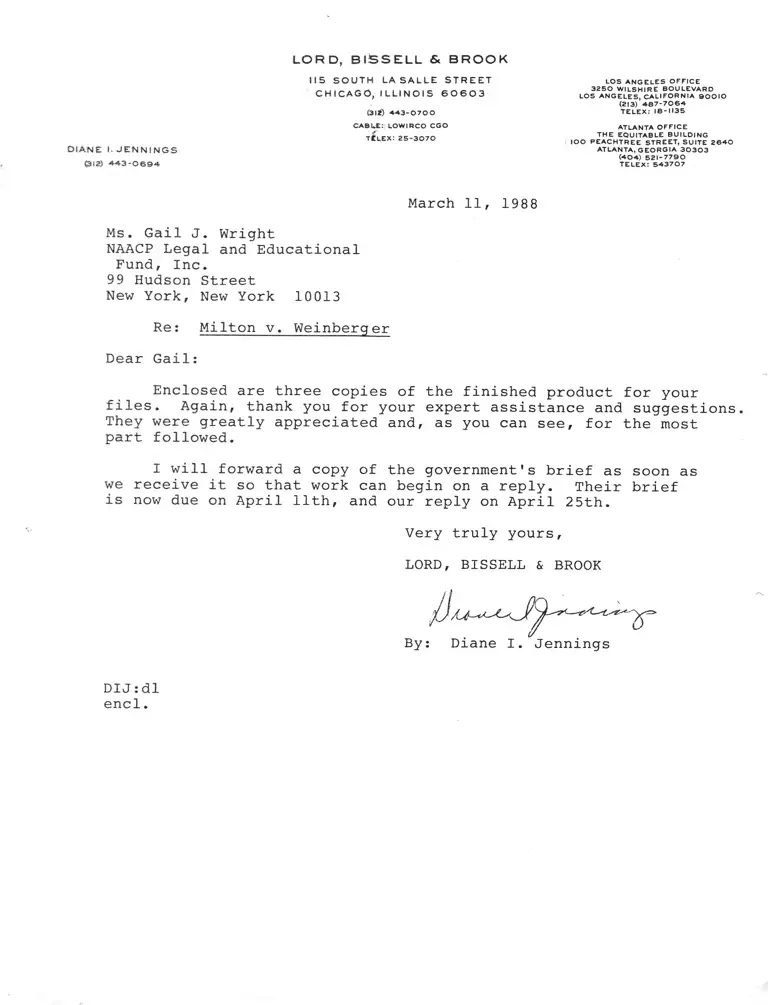

March 11, 1988

Ms, Gail J. Wright

NAACP Legal and Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Re: Milton v, Weinberger

Dear Gail:

Enclosed are three copies of the finished product for your

files. Again, thank you for your expert assistance and suggestions.

They were greatly appreciated and, as you can see, for the most

part followed.

I will forward a copy of the government's brief as soon as

we receive it so that work can begin on a reply. Their brief

is now due on April 11th, and our reply on April 25th.

Very truly yours

LORD, BISSELL & BROOK

/ 1

By: Diane I. Jennings

DIJ:dl

e n d .

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For The Seventh Circuit

No. 87 - 3096

DONALD L. MILTON,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

vs.

CASPER WEINBERG, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE,

DEFENSE LOGISTICS AGENCY, DCASR, Chicago,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division

The Honorable Paul E. Plunkett, Judge Presiding.

PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT'S BRIEF AND APPENDIX

Of Counsel:

DANIEL I. SCHLESSINGER

HUGH C. GRIFFIN

DIANE I. JENNINGS

LORD, BISSELL & BROOK

115 S. LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

(312) 443-0694

JULIAN L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

GAIL J. WRIGHT

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

Donald L. Milton

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

NAACP Legal and Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Oral Argument Requested

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Issue Presented for Review............................... I

Jurisdictional Statement....................... 1

Nature of the Case....................................... 3

Statement of Facts....................................... 5

Argument........ 12

Once Plaintiff Proved Discrimination By

Indirect Evidence Rebutting The Articulated

Reason For His Discharge, He Was Not Required To Rebut

Unarticulated Reasons Nor To Present Direct

Evidence Of Racial Bias In Order To Prevail....... 12

A. Discrimination May Be Proved By Direct Or

By Indirect Evidence Of Defendants'

Motivation...... 12

B. Milton’s Evidence And The Court’s Findings

Thereon Mandated A Conclusion That Racial

Bias Was The Cause Of His Discharge............. 19

C. In Any Event, The Trial Court's Ruling Is

Based On Erroneous Factual Findings............. 25

Conclusion................................................. 28

Appendix

Statement Pursuant To Circuit Rule 30................ A1

Order Finding For Defendants And Against Plaintiff,

Docketed Aug. 28, 1987............................... A4

Order Denying Plaintiff's Motion For Reconsideration,

Docketed Oct. 23, 1987............................... A4

Transcript Of Proceedings Of Aug. 27, 1987,

Containing District Court's Oral Findings And

Conclusions............................................ A5

Transcript of Proceedings Of October 22, 1987,

Containing District Court's Oral Statement Of

Findings On Denial Of Motion For Reconsideration.... A14

- l -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

DeLisstine v. Fort Wayne State Hospital and Training

Center, 682 F.2d 130 (7th Cir. 1982), cert, denied

459 U.S. 1017, 74 L. Ed. 2d 511, 103 S. Ct. 378 (1982).. 20

Duffy v. Wheeling Pittsburgh Steel Corp., 738 F.2d 1393

(3d Cir. 1984), cert, denied 469 U.S. 1087, 83 L. Ed. 2d

702, 105 S. Ct. 592 (1984).............................. 14

Flowers v. Crouch-Walker Corp., 552 F.2d 1277

(7th Cir. 1977).......................................... 19

Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567, 57

L. Ed. 2d 957, 98 S. Ct. 2943 (1978).................... 17

Graham v. Bendix Corp., 585 F. Supp. 1036

(N.D. Ind. 1984)......................................... 23

Hogan v. Pierce, 31 F.E.P. 115 (D. D.C. 1983).......... 23

Lanphear v. Prokop, 703 F.2d 1311 (D.C. Cir. 1983)..... 14, 24

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792,

36 L. Ed. 2d 668, 93 S. Ct. 1817 (1973)................. 12, 17

Mister v. Illinois Central Gulf R.R. Co., 832

F . 2d 1427 (7th Cir. 1987)................................ 14, 18

Riordan v. Kempiners, 831 F.2d 690 (7th Cir. 1987)..... 18

Rosemond v. Cooper Industrial Products, 612 F. Supp.

1105 (N.D. Ind. 1985).................................... 23

Texas Department of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U.S. 248, 67 L. Ed. 2d 207, 101 S. Ct. 1089 (1981)..... 15

United States Postal Service Board of Governors

v. Aikens. 460 U.S. 711, 75 L. Ed. 2d 403,

103 S. Ct. 1478 (1983)................................... 12 > 1 1 • 24

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 50 L. Ed. 2d 450, 97 S.

Ct. 55 ( 1977)............................................. 22

Statutes

5 U.S.C. §4302 ............................................ 21

42 U.S.C. §20Q0e et seg................................... 12

-i i-

ISSUE PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Can the District Court's conclusion that Plaintiff failed to

establish racial bias as a motivation for his discharge stand in

light of the Court's findings that:

a) the Defendants' sole articulated reason for discharge

was not believable; and

b) the Defendants failed to comply with statutory and

regulatory requirements, otherwise observed by them, that

Plaintiff be given notice of any performance deficiencies and an

opportunity to remedy them?

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

This action seeking relief from race discrimination in

employment was brought against the United States Secretary of

Defense, pursuant to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

(42 U.S.C. §2000e et se^.), as amended by the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972 (42 U.S.C. §2000e-16). Plaintiff was

notified on October 7, 1983 that, effective December 2, 1983, he

would be discharged from his employment with the DCASR, an

agency of the Defense Department. (R. 61 at p. 2; A6) On

December 16, 1983, he filed charges with the agency's Equal

Employment Opportunity Officer (" E E C ) alleging that his

discharge was racially motivated. (R. 1 at p. 2)

The EEO issued a right to sue letter, which Milton received

on September 14, 1984 (R. 1 at p. 2, R. 61 at p. 2), and this

action was filed on Monday, October 15, 1984 (R. 1). The

District Court had jurisdiction thereof under 42 U.S.C. §

20Q0e-5(f), 2000e-16(c), conferring jurisdiction of claims

arising under Title VII, and under 28 U.S.C. §1343(a)(4),

conferring jurisdiction of claims arising under any Act of

Congress providing for the protection of civil rights.

The District Court's final order and judgment finding in

favor of Defendants and against Plaintiff were docketed on

August 28, 1987. (App. A2, A3) Plaintiff sought

reconsideration of the Court's ruling in a motion received by

the District Court and served on Defendants on September 8,

1987, the Tuesday following the Labor Day holiday. (R. 83)

That motion was denied in an order entered October 23, 1987.

(App. A4) Plaintiff filed and served his notice of appeal to

this Court 60 days thereafter, on December 22, 1987 (R. 91),

pursuant to Rule 4(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

providing that a notice of appeal must be filed within 60 days

if the United States or an officer or agency thereof is a party

to the action. (F.R.C.P. 4(a).) This Court has jurisdiction of

the appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1291, conferring jurisdiction

of appeals from all final decisions of the district courts.

2

NATURE OF THE CASE

This action, brought pursuant to Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq.), as amended by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16)

involves allegations of racial discrimination in the discharge

of Plaintiff Donald Milton (hereinafter "Milton") from federal

employment. (R. 1, p. 2-3) Milton, a black, male citizen of

the United States, was hired by an agency of the United States

Department of Defense (hereinafter "DCASR") on January 3, 1983

for the position of Facilities Engineer, GS-801-11, a

Career-Conditional Appointment subject to a one year

probationary period. (Def. Ex. D) On July 29, 1983, he

received a positive written appraisal of his work in accordance

with agency rules and regulations, but on October 5, 1983 he was

told that his performance was unacceptable and on October 7,

1983 he was discharged, effective December 2, 1983. (R. 61 at

p. 2, A6)

The cause was tried before Judge Paul E. Plunkett,

sitting without a jury, on May 12, 1987 and August 12, 1987.

(R. 96-1, 96-2) Judge Plunkett entered judgment in favor of the

DCASR on August 28, 1987. (App. A2, A3) Although no written

findings of fact and conclusions of law were entered, Judge

Plunkett orally set forth the reasons for his ruling on August

27, 1987, stating (App. A6-A13):

3

1. Milton had established a prima facie case of racial

discrimination in his discharge.

2. If the case involved a question of discharging him

without cause and without due process, Milton would prevail, as

the nondiscriminatory reason proffered by the DCASR,

incompetence, was not true, and the DCASR had failed to follow

applicable regulations in discharging him without giving notice

of his purported deficiencies and an opportunity to remedy them;

and

3. The Court nevertheless was not persuaded that the

discharge was racially motivated, in light of the fact that the

supervisor who discharged Milton had also hired him and had

given him a positive evaluation two months before his

discharge. Accordingly, the Court found that no racial

motivation had been proved. (App. A9)

Thereafter, on September 8, 1987, Plaintiff moved for

reconsideration of Judge Plunkett's ruling (R. 83), which was

denied in an order docketed October 23, 1987 (App. A4). In so

ruling, Judge Plunkett stated that, while he had rejected the

reasons given by the DCASR for discharging Milton, he believed

that the reason for his discharge was that his supervisor

"simply didn't get along with him." (App. A15) This appeal

followed.

4

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Introduction

The District Court found that Milton, a qualified and

competent black civil engineer, was performing his job as a

Facilities Engineer with the DCASR in a satisfactory manner.

(App. A6-A13) Nevertheless, Milton was fired without being

afforded the opportunity to cure claimed deficiencies in his

performance, even though such an opportunity was required by

federal statute and regulations. The District Court’s

conclusion that this evidence failed to establish racial bias as

the motivating factor in Milton's unwarranted discharge without

procedural safeguards afforded to other employees is totally

contrary to the following evidence and findings:

The DCASR Chose Milton Over Other Minority

Candidates For The Position Of Facilities Engineer

Milton was employed by the Defense Contract

Administrative Services Region-Chicago ("DCASR"), a division

within the Defense Logistics Agency, an agency of the United

States Department of Defense. (R. 61 at p. 2; App. A6) In late

1982, Larry Vann, chief of the DCASR*s Resources and Procedures

Branch, determined that a facilities engineer was needed to

monitor several pending and contemplated agency construction

Projects. (R. 96-1 at p. 125-126) Accordingly, he developed a

position description (PI. Ex. 3) and forwarded it to the

personnel office with a request that eligible candidates for the

5

position be identified. (Def. Ex. 0 at p. 86) Personnel sent

him the names of three such candidates: Milton, Mrs. Doshin L.

Park, and Mr. Nanvant A. Patel. (R. 96-1 at p. 127-128; Def.

Ex. 0 at p. 86-87) Vann interviewed Milton and Mrs. Park, a

Korean national, but did not interview the third candidate. (R.

96-1 at p. 128)

Milton, a licensed professional engineer (R. 96-1 at p.

28) was found qualified for the position (R. 61 at p. 2; App.

A6), and was hired to begin work in Vann's department on January

3, 1983 (R. 96-1 at p. 13; Def. Ex. D). His qualifications

included a bachelor's degree in civil engineering, a master’s

degree in business administration, and extensive work experience

in structural design and supervision of construction. (R. 96-1

at p. 28-32)

Vann Fails To Provide The Guidance

And Orientation Afforded Other Employees

The supervisors in the branch where Milton worked were

all white, as were all of the other employees except Joyce

McClain, a black female. (R. 96-1 at p. 33-34) On the day

Milton started work, Vann gave him a brief overview of the job,

but did not explain in detail what Milton's duties would be.

(R. 96-1 at p. 57) Thereafter, Vann did not afford Milton any

orientation regarding work procedures and methods, although he

frequently gave such guidance to Donald Guerra, a white employee

hired just two months after Milton. (R. 96-1 at p. 70)

6

The agency had an orientation program which was offered

periodically for new employees. (R. 96-1 at p. 167) Vann never

told Milton that this program existed because "it wasn't his

responsibility" to do so. (R. 96-1 at p. 168) Sometime after

Milton began work, however, a fellow employee mentioned the

program, and Milton asked Vann about it. (R. 96-2 at p.

268-269) Vann promised to enroll Milton in the program, but

never did so. (R. 96-2 at p. 269) In fact, during the 11

months that Milton worked for the agency Vann never even

inquired whether a session was scheduled. (R. 96-1 at p. 168)

Milton Received Positive Evaluations

Prior To His Sudden Discharge

The District Court found that, during the course of

Milton's employment, a single counseling session took place in

April of 1983, in which Vann criticized his work, including

perceived inadequate preparation for a meeting; layouts prepared

for two offices; and "general lack of work quality and

timeliness". (App. A8; PI. Ex. 9; R. 96-1 at p. 168-169) Three

months later, however, on July 29, 1983, Vann completed a

performance appraisal of the four "critical job elements" of

Milton's work. He rated Milton as "highly successful" in his

contribution to the professional work environment and in

monitoring facility management, and "fully acceptable" in

maintaining communications and monitoring minor construction.

(PI. Ex. 4; R. 96-1 at p. 173-174) Vann himself had determined

the job elements which would be appraised, elements which by

7

regulation must accurately reflect the important aspects of the

employee's work. (R. 96-1 at p. 173)

At trial, Vann acknowledged that the primary purpose of

that evaluation was to inform the employee of how he was doing

(R. 96-1 at p. 173); that it is important to tell an employee if

he is not performing well, in order to give him an opportunity

to improve (R. 96-1 at p. 162); and that regulations in fact

required that employees whose performance is below standard be

counseled and that supervisors determine what training will

improve that performance and arrange for it to be provided (R.

96-1 at p. 158-161). Vann asserted, however, that even though

he considered Milton's performance to be so bad that he viewed

him as a "walking joke", he gave Milton a positive appraisal,

knowing that the evaluation would lead Milton to conclude that

he was doing a good job. (R. 96-2 at p. 177)

Vann's uncommunicated opinion that Milton was completely

worthless conflicted sharply with that of others who had

occasion to observe his performance. Because of the nature of

his job, Milton worked with a number of other supervisory

personnel both within the agency and outside of it. He received

nothing but positive comments from them, and several testified

at trial that his work in fact was completely satisfactory. (R.

96-1 at p. 39-44; Testimony of Barbara Reynolds, R. 96-2 at p.

222-231; R. 96-1 at p. 104; Supp. R., Kekoolani Dep. at p.

13-20) No supervisor other than Vann testified that Milton s

Performance was below expectations.

8

Vann Demonstrated Unjustified Distrust

Of The Ability Of Black Employees To Perform

Throughout the time of his employment, Milton observed

that Vann had less confidence in the ability of black employees

to do their work than he did in the ability of white employees.

(R. 96-2 at p. 270) That perception of attitudes within the

department was corroborated by Joyce McClain, the only other

black employee. She joined the DCASR in 1979 with the

understanding that, at the end of one year of service she would

be promoted from Grade 9 to Grade 11. (R. 96-2 at p. 233,

238-239) Ms. McClain did all of the work assigned to her during

that year, and received a good performance appraisal, but

nevertheless was told that she would not be promoted because she

"was not doing Grade 11 work." (R. 96-2 at p. 242) A white

employee was promoted, and when Ms. McClain complained, she was

suddenly promoted, without explanation, after a six week delay.

(R. 96-2 at p. 242-243) Thereafter, Ms. McClain repeatedly

asked to be given the broader assignments which would lead to

further promotion, rather than having her work confined to a

single narrow program. Vann promised to do so, but nevertheless

continued to apportion the more important work among the white

employees in the office. (R. 96-2 at p. 244-245, 251)

Milton Was Suddenly Discharged For

Purportedly Incompetent Job Performance

On October 5, 1983, Vann met with Milton regarding

purported failure to plan for relocation of employees during a

9

construction project, and suggested at that meeting that Milton

look for another job. (PI. Ex. 9; R. 96-2 at p. 194-195) Two

days later, -Milton was given written notice of his termination

effective approximately 50 days later. (PI. Ex. 5; R. 96-2 at

p. 195) That letter detailed four areas of alleged

unsatisfactory performance: poor planning in monitoring

facilities management; failure to complete assignments on time;

"unacceptable" correspondence; and errors in assigned projects.

(PI. Ex. 5)

The District Court Rejects The DCASR's

Claim That Milton Performed Incompetently

The bulk of the trial testimony involved the DCASR's

claim that Milton was incompetent to perform his job, and

Milton's rebuttal of that claim by showing that the allegations

regarding his work were unfounded. Vann's testimony detailing

his complaints about Milton's performance in large part dealt

with incidents which predated the positive performance appraisal

Vann gave him in July of 1983. (R. 96-1 at p. 132-152) With

regard to the incident which purportedly precipitated his

discharge, failure to move employees and files in advance of

construction (R. 96-1 at p. 146-147), Milton explained that he

had made repeated efforts to have the files moved, but it was

not done by those charged with the task of moving them (R. 96-1

at p. 81-82, 91-92), and that the movement of personnel was

necessitated only by last minute, major changes in the scope of

the work to be done; changes which Vann himself made without

10

informing Milton (R. 96-2 at p. 261-263; PI. Ex. 12).

Judge Plunkett rejected the DCASR's claim that Milton was

incompetent, noting that the incidents complained of predated

the positive appraisal, and that the failure to move employees

stemmed from Vann's failure to notify Milton of the altered

construction plans. (App. A8-A9) He was also of the opinion

that the reasons proffered by the DCASR did not constitute

grounds for discharging Milton, and that the DCASR had failed to

follow its own regulations in not providing Milton an

opportunity to cure any perceived deficiencies in his

performance. (App. A10) Nevertheless, Judge Plunkett found in

favor of the DCASR, refusing to draw any adverse inference from

the failure to follow procedures, or to ascribe racial bias as a

motivation for the employment decisions because the supervisor

who fired Milton had hired him and had given him a positive

evaluation. (App. A8-A9)

Judge Plunkett did, however, find it to be a close

question, and invited Milton's counsel to submit a motion for

reconsideration. (App. A13) After reviewing the motion, Judge

Plunkett declined to change his ruling, expressing uncertainty

over the applicable standard, and finding that Milton was fired

because his supervisor “simply didn’t get along with him.”

(App. A4, A15) This appeal followed.

11

ARGUMENT

ONCE PLAINTIFF PROVED DISCRIMINATION BY INDIRECT

EVIDENCE DISPROVING THE ARTICULATED REASON FOR

HIS DISCHARGE HE WAS NOT REQUIRED TO REBUT

UNARTICULATED REASONS NOR TO PRESENT DIRECT EVIDENCE

OF RACIAL BIAS IN ORDER TO PREVAIL

A. Discrimination May Be Proved By Direct Or

By Indirect Evidence Of Defendants' Motivation

The elements of a prima facie case of discrimination in

employment under Title VII (42 U.S.C. §2Q00e et seq.), and the

order and allocation of proof in such an action, established by

the Supreme Court in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792, 36 L. Ed. 2d 668, 93 S. Ct. 1817 (1973), are well known and

are not now in issue. Where, as here, the trial court

determines that a prima facie case has been established and that

a legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for discharge has been

articulated, the question becomes whether the plaintiff has met

his burden of persuading the court that racial bias motivated

the adverse employment action complained of. (United States

Postal Service Board of Governors v. Aikens, 460 U.S. 711, 75 L.

Ed. 2d 403, 103 S. Ct. 1478 (1983).) As the Aikens Court

further held, that burden of persuasion may be met in either of

two ways:

"As we stated in Burdine:

'The plaintiff may succeed [in fulfilling

the burden of persuasion] either directly

by persuading the court that a

discriminatory reason more likely motivated

the employer or indirectly by showing that

the employer's proffered explanation is

12

unworthy of credence.'

In short, the district court must decide

which party's explanation of the employer’s

motivation it believes." 460 U.S. at 716,

75 L. Ed. 2d at 410, 103 S. Ct. at 1482.

(Citation omitted, emphasis added.)

The District Court effectively found that Milton had

sustained his burden when it ruled that the DCASR's proffered

explanation for firing Milton was not believable. This finding

mandated a judgment in Milton's favor.

M[T]he McDonnell Douglas framework requires that

a plaintiff prevail when at the third stage of a

Title VII trial he demonstrates that the

legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason given by

the employer is in fact not the true reason for

the employment decision." (Aikens, supra, 460

U.S. at 718, 75 L. Ed. 2d at 417, 103 S. Ct. at

1483 (Blackmun, J., concurring).)

The District Court erred, however, like the trial court in

Aikens, in apparently believing that the plaintiff in a Title

VII case is required to offer direct evidence of

discrimination. Judge Plunkett decided that he could not find

for Milton because he was not persuaded that the firing decision

maker, Larry Vann, had a "discriminatory approach or thinking or

conduct." (App. All) Such evidence is clearly not required

when the plaintiff proves his case through the indirect method.

460 U.S. at 714 n. 3, 75 L. Ed. 2d at 409 n. 3, 103 S. Ct. at

1481 n. 3.

To the contrary, reasonably read McDonnell Douglas and

Aikens state that a Title VII plaintiff who demonstrates that

the proffered justification for firing is a pretext has won his

13

case. As this Court stated recently in Mister v. Illinois

Central Gulf R .R . Co . , 832 F. 2d 1427 (7th Cir. 1987), where the

only reasons advanced for the disparate treatment are racial

bias and a "legitimate" reason which has been disproved,

acceptance of the discriminatory motivation is compelled. 832

F. 2d at 1435. See also Aikens, supra, Blackmun concurring

opinion at 460 U.S. 718; Duffy v. Wheeling Pittsburgh Steel

Corp., 738 F. 2d 1393, 1396 (3d Cir. 1984) cert, denied, 469

U.S. 1087, 83 L. Ed. 2d 702, 105 S. Ct. 592 (1984) (under Aikens

the only burden of persuasion under the indirect method of

establishing discrimination is proving that the proffered

justification is not true; to find pretext is to find

discrimination).

In any event, at a minimum the McDonnell Douglas

framework of a three stage trial guarantees the plaintiff a

procedure by which he is confronted with the evidence against

him (once he has established a prima facie case) and given the

opportunity to rebut that evidence. If he is successful in his

rebuttal, he wins. The plaintiff cannot reasonably be expected

to rebut all possible reasons for his firing, only those with

which he is confronted. Indeed, the Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia so held under similar circumstances in

Danphear v. Prokop, 703 F. 2d 1311 (D.C. Cir. 1983). There, as

here, the employer claimed that the plaintiff was discharged

because he did not perform his job competently. As Milton did

in the instant case, the plaintiff in Lanphear then devoted his

14

energies" to proving that the articulated reason was not true.

(703 F. 2d at 1316.) He was successful, but the district court

nevertheless entered judgment for the employer, finding that the

plaintiff was discharged because his employer "’wanted to inject

new blood into the agency,'" a reason never articulated by the

employer. (703 F. 2d at 1316.)

The Court of Appeals reversed that ruling and remanded

the cause with directions to enter judgment for the plaintiff,

stating in pertinent part:

"The district court's substitution of a reason of its own

devising for that proffered by appellees runs directly

counter to the shifting allocation of burdens worked out

by the Supreme Court in McDonald Douglas and Burdine.

The purpose of that allocation is to focus the issues and

provide plaintiff with 'a full and fair opportunity' to

attack the defendant's purported justification. That

purpose is defeated if defendant is allowed to present a

moving target or, as in this case, conceal the target

altogether.

The Supreme Court explicitly added [in Texas Department

of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248, 255-56, 67

L. Ed. 2d 207, 101 S, Ct. 1089 (1981)] that '[a]n

articulation not admitted into evidence will not

suffice. Thus, the defendant cannot meet its burden

merely through an answer to the complaint or by argument

of counsel.' It should not be necessary to add that the

defendant cannot meet its burden by means of a

justification articulated for the first time in the

district court's opinion." (703 F. 2d at 1317. Emphasis

in original.)

In the instant case, Milton successfully took on every

bit of evidence presented that he was fired for a legitimate

reason. The District Court, agreeing with Milton, found every

reason offered by the DCASR for his discharge to be pretextual.

15

The court's finding that Milton was fired because his boss

couldn't get along with him is unfair and unsupportable under

Lanphear, not just because this was not one of the reasons

claimed by the DCASR, but because absolutely no evidence was

presented to support that finding. Milton's supervisor, Larry

Vann, who made the decision, advanced several reasons for firing

Milton, some of which were consistent with the reasons given by

the DCASR. None of the reasons Vann gave, however, was his

inability to get along with Milton. The exclusion of this

reason from Vann's list amounts to a denial that this was the

reason.

Even if the Court could have concluded that Vann and

Milton did not get along, that conclusion of itself does not

warrant a further conclusion that the failure to get along was

the reason for Milton's firing. If that had been articulated as

a reason and Vann had been asked the question directly, he might

well have denied that conclusion. More importantly, since no

evidence was presented that the DCASR fired Milton because Vann

did not get along with him, Milton had no chance to rebut such a

contention. For example, if confronted with such a claimed

nondiscriminatory reason, thus placing on Milton the burden to

show pretext, he might have presented evidence that Vann did not

get along with various white employees, but never fired any of

them as a result.

McDonnell Douglas's three-part procedure assures Milton

of the opportunity to rebut any articulated claim of a

16

legitimate reason for his firing. (See Aikens, supra, 460 U.S.

at 716, n. 5, 75 L. Ed. 2d at 410-411 n. 5, 103 S. Ct. at 1482.

("Of course, the plaintiff must have an adequate 'opportunity to

demonstrate that the proffered reason was not the true reason

for the employment decision,' but rather a pretext.").) As the

Lanphear Court recognized, he cannot be saddled with the

additional burden of anticipating and rebutting any and all

unclaimed, unarticulated reasons for the employer’s adverse

action which might occur to the court, no matter how arbitrary

or subjective. Such a reading would, in effect, require direct

proof of discrimination.

The Supreme Court's mandate that a plaintiff be permitted

to meet his burden of persuasion by proving that the reasons

articulated for his discharge are not worthy of credence arises

from the Court's recognition that, in a business setting,

decisions are not random and arbitrary; when articulated

legitimate reasons are eliminated, it is in fact more likely

than not that the decision was based on an impermissible

consideration such as race. (Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters,

438 U.S.

(1978) . )

afforded

assigned

its appl

a prompt

at 807,

567, 577, 57 L. Ed. 2d 957, 967, 98 S. Ct. 2943, 2949

For this reason, a Title VII plaintiff "... must be

a fair opportunity to demonstrate that [the employer's

reason for firing] was a pretext or discriminatory in

ication. If the District Judge so finds, he must order

and appropriate remedy." McDonnell Douglas, 411 U.S.

36 L. Ed. at 680, 93 S. Ct. at 1827. (Emphasis added.)

17

The Supreme Court has expressly held that a Title VII

claimant is not, and cannot be required to present direct

evidence of racial bias as the reason for his discharge.

(Aiken, 460 U.S. at 717, 75 L. Ed. 2d at 411, 103 S. Ct. at

1483.) The reason for refusing to place such a burden on the

plaintiff was explained recently by this Court as follows:

"Proof of [intentional discrimination in

employment] is always difficult. Defendants of

even minimal sophistication will neither admit

discriminatory animus nor leave a paper trail

demonstrating it; and because most employment

decisions involve an element of discretion,

alternative hypotheses (including that of simple

mistake) will always be possible and often

plausible. Only the very best workers are

completely satisfactory, and they are not likely

to be discriminated against - the cost of

discrimination is too great. The law tries to

protect average and even below-average workers

against being treated more harshly than would be

the case if they were of a different race, sex,

religion or national origin, but it has

difficulty achieving this goal because it is so

easy to concoct a plausible reason for not

hiring, or firing, or failing to promote, or

denying a pay raise to, a worker who is not

superlative." (Riordan v. Kempiners, 831 F. 2d

690, 697-698 (7th Cir. 1987).)

Under Aikens and any proper interpretation thereof,

Milton could meet his burden of persuasion by demonstrating that

the articulated reasons for the DCASR's adverse employment

actions were pretext, i.e ., an explanation that did not convey

the motivation for the employment decision. (Mister_v_.— 111 i no is

Central Gulf R .R . Co., 832 F. 2d 1427, 1435 (7th Cir. 1987).)

The District Court found that he had done so. The DCASR claimed

that Milton was incompetent, and the Court found that this was

18

not true. The DCASR claimed that regulations requiring that

Milton be given notice of performance deficiencies and an

opportunity to improve were not followed because they did not

apply to Milton, but the District Court found that they did

apply. Nevertheless, the Court found in favor of the DCASR,

ruling that Milton was fired because of a reason never

articulated or in any way advanced as the reason for discharge,

namely, that his supervisor "did not get along with him", and

the Court saw no evidence that the supervisor's animosity was

racially motivated. That ruling is directly contrary to the

Court’s own findings, and improperly places on Milton the

impossible burden of proving directly his supervisor's

subjective motivations.

B. Milton’s Evidence And The Court's Findings

Thereon Mandated A Conclusion That Racial

Bias Was The Cause of His Discharge __________ _

In the instant case, as he was entitled to do under the

law, Milton proceeded to meet his burden of persuasion by

presenting evidence that the ground asserted by the DCASR for

discharging him, namely, incompetence, was not worthy of

credence. In order to meet that burden, it was not necessary to

prove himself the perfect employee; it was enough to show that

his performance was of sufficient quality to merit continued

employment. (Flowers v. Crouch-Walker Corp., 552 F. 2d 1277

(7th Cir. 1977).) Where, as here, the reason relied upon by the

defendant is found not to warrant dismissal, an inference of

19

improper motivation arises. DeLisstine v. Fort Wayne State

Hospital and Training Center, 682 F. 2d 130 (7th Cir. 1982),

cert, denied 459 U.S. 1017, 74 L. Ed. 2d 511, 103 S. Ct. 378

(1982).

At trial, the DCASR dredged up every instance of real or

imagined errors in Milton's performance, for the most part

incidents predating the excellent evaluation he received just

two months before his discharge. Such acceptance, and indeed

praise of Milton's work despite claimed errors therein, refuted

any notion that those errors, even if they occurred, justified

discharge. (Flowers, supra.) Similarly, Milton proved that the

subsequent claimed failure to move personnel from a dangerous

work area was in fact not an error on his part, but on the part

of the supervisor who failed to tell him of a major change in

the work to be done, then used that as an excuse to fire him.

As the District Court quite correctly ruled, the conduct

complained of simply did not constitute good grounds for

discharging Milton. (See DeLesstine, supra, holding that proof

that the defendant's claimed ground for dismissal did not

constitute good cause justified a finding that the action was

predicated on racial bias.)

Milton presented further evidence of disparate treatment

in the manner in which he was discharged, which the DCASR

admitted. Federal statutes and regulations governing

Probationary employees require not only that they be evaluated

in accordance with an established appraisal system, but also

20

that they be assisted in improving unacceptable performance, and

that adverse employment action be taken only after the employee

has had an opportunity to demonstrate acceptable performance.

(5 U.S.C. §4302; PI. Ex. 7, 8) Vann admitted that he generally

followed these regulations, but that he did not give Milton the

opportunity to improve described and provided for in the statute

and in the agency's regulations. (R. 96-1 at p. 160-161, R. 96-2

at p. 195) Although the DCASR insisted that these requirements

did not apply to probationary employees, the District Court

correctly found that they not only were applicable, but also

were violated. That conclusion was supported by the fact that,

unlike other sections of the statute, the provision at issue

does not exclude probationary employees (See, e .g ., 5 U.S.C.

§4303); by evidence that the DCASR had in fact promulgated and

applied the appraisal system mandated by section 4302 and its

regulations to Milton, a probationary employee (PI. Ex. 4); by

Vann's admission that regulations required him to counsel and

assist employees whose performance is substandard (R. 96-1 at p.

158-161); and by the concern expressed by the DCASR's own

employees in investigating Milton’s discharge that proper

procedures were not followed (Def. Ex. 0 at p. 53-54).

The DCASR itself admitted that the written appraisal

given to Milton on July 29, 1983 would have led him to believe

that he was doing a good job, and no changes were necessary.

(R. 96-2 at p. 177) The counseling and assistance required by

the DCASR's own rules simply was not afforded to Milton.

21

Instead, just two months after being told that his work was

"fully acceptable" and "highly successful” (PI. Ex. 4), without

any intervening indication of a problem, he was informed that

that same work was unsatisfactory and he would be terminated as

a result. (PI. Ex. 5; R. 96-2 at p. 194-195) Such disparate

treatment was itself discriminatory. Nevertheless, while Judge

Plunkett acknowledged that regulations were violated, and that

Milton was denied due process (App. A10), the evidence was

dismissed with a statement that the Court "did not draw any

adverse inferences" from the DCASR's failure to afford Milton

the opportunity afforded others to demonstrate satisfactory

performance, an opportunity required by its own rules.

The court's summary dismissal of this evidence was

error. Federal government employers, unlike private employers,

are not free to operate their employment practices in any way

that they choose. The DCASR is bound by statute, civil service

regulations, directives and its own internal procedures which

require that its employment activities be conducted in a lawful

manner. The failure to comply with such governing regulations

(5 U.S.C. §4302; PI. Ex. 7, 8) was strong evidence that the

reasons advanced were pretexts for intentional discrimination.

As the Supreme Court held in Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 267, 50 L.

Ed. 2d 450, 97 S. Ct. 55 (1977), departure from prescribed

requirements or procedures is evidence of discrimination. When

coupled with the "specific sequence of events leading up to the

22

challenged decisions," (id.), including the face that Milton had

not received any notification that his performance was

unsatisfactory, and in fact had received a favorable appraisal,

a powerful circumstantial case of discrimination was made. See,

e,q., Rosemond v. Cooper Industrial Products, 612 F. Supp. 1105

(N.D. Ind. 1985) (failure to afford employee guidance or aid in

improving her performance, as required by employer's own

policies, evidenced racial bias); Graham v. Bendix Corp., 585 F.

Supp. 1036 (N.D. Ind. 1984) (departure from defendant’s own

written policies, treating plaintiff more severely than

mandated, evidenced discrimination); Hogan v. Pierce, 31 F.E.P.

Cases 115, 127 (D. D.C. 1983) (failure to follow proper

procedures was evidence of pretext).

Milton proceeded to rebut every nondiscriminatory reason

proffered by the DCASR for its employment decisions in the only

manner available to most Title VII plaintiffs, namely by

establishing that the proffered reasons were not worthy of

credence. The District Court found that Milton had met that

burden. (App. A10) Nevertheless, the District Court denied

Milton's claim, finding that he was fired because "his

supervisor did not get along with him", but that there was no

evidence that the supervisor had "a discriminatory approach or

thinking or conduct." (App. All)

Contrary to Judge Plunkett's ruling, under Aikens that

showing was sufficient, since proof that the articulated reason

for the DCASR's action is not the true reason renders it more

23

likely than not that the action was motivated by racial bias.

Milton cannot enter the minds of the DCASR’s employees to show

what motivated their wrongful conduct toward him, and the law

does not require that he do so. (See Aikens, supra.)

Similarly, Milton cannot, and should not be required to rebut

speculative "reasons" which were never proffered, such as the

bare possibility that the conduct was motivated by a

supervisor's personal dislike for him untinged by considerations

of the fact that he is black. See Lanphear, supra.

The District Court’s ruling in the instant case is

contrary to the evidence and its own findings thereon, and its

decision that discriminatory motivation has not been shown

accordingly should be reversed and remanded with directions to

enter judgment for Milton. At the very least, given the

District Court's professed uncertainty concerning the effect of

a finding that the articulated reasons were not worthy of

credence, and the strong likelihood that the Court's ruling was

based on the lack of direct evidence of racial bias on Vann's

part, the cause should be remanded with instructions to

reconsider the decision in the light of the Supreme Court's

ruling in Aikens that a Title VII claimant may not be required

to present direct evidence of bias. Certainly remand is

appropriate in the instant case, where Milton was never

confronted with, and accordingly had no opportunity to rebut,

the reason found by the Court to have motivated his discharge.

24

C. In Any Event, The Trial Court's Ruling

Is Based On Erroneous Factual Findings

The District Court based its ruling that Vann’s conduct

was not racially motivated on two erroneous findings: (1) that

Vann had hired Milton in the first place, and therefore was not

biased against him; and (2) that Vann gave Milton a positive

performance appraisal prior to his discharge, and therefore

could not have been biased on racial grounds. However, the

Court overlooked the fact that it was the personnel office, not

Vann, which determined what candidates were eligible for the

position. Vann had a position to fill and was presented with a

list to choose from which contained three names, that of a black

male (Milton), that of a Korean female (Mrs. Park), and that of

a male East Indian (Mr. Patel). The fact that Vann chose a

highly qualified black male from a list of three minority

candidates for the position is hardly compelling evidence of

Vann’s freedom from prejudice or bias in his perception of the

ability of a black person to handle the job, particularly in

light of the testimony that he perceived those of a different

race to be less qualified generally.

Judge Plunkett’s further reliance on the positive

evaluation given in July is premised on an inference that, if

Vann harbored racial bias, he would have given Milton a poor

evaluation. However, as Vann himself acknowledged, giving an

employee a poor evaluation would have allowed him to improve his

performance, and obligated Vann to work with him and assist him

25

in improving his work. (R. 96-1 at p. 158-163) By giving

Milton a satisfactory appraisal, Vann could avoid assisting him

and insure that perceived problems in Milton's performance would

not be remedied. Certainly such an evaluation is inconsistent

with Vann's belief that Milton was a "walking joke". Judge

Plunkett was troubled by this very inconsistency, but resolved

it by concluding that Vann did not form that opinion until after

the July, 1983 evaluation. (App. A10) That conclusion was

wrong. Vann's own testimony was that he had reached that

conclusion before evaluating Milton. (R. 96-2 at p. 177)

The strong inference of racial bias arising from the

finding that the DCASR's proffered reason for discharge was

untrue, and that Milton was not given the opportunity to, or

assistance in, improving his performance mandated by the DCASR s

own regulations simply was not dispelled or negated in any way

by Vann's prior conduct. Vann had no non-minority candidate to

choose from in filling the position, and the fact that he might

elect to avoid blatant discrimination by rejecting an obviously

qualified and pre-approved candidate is not inconsistent with

the existence of racial bias in perceptions of that candidate s

work product or the refusal to give him the same opportunities

afforded other employees. If that were the case, any employer

could avoid a finding of discrimination in its adverse

employment decisions simply by pointing to the fact that the

employee was hired in the first place, and arguing that his

employer therefore could not possibly be biased.

26

That simply is not, and cannot be the law. Milton was

entitled to have all of the DCASR's employment decisions about

him, not just his initial hiring, made without regard to his

race. The District Court's conclusion that the wrongful

treatment found to exist in the instant case must have had some

other basis than race is simply contrary to the evidence, and

should be reversed.

27

CONCLUSION

Donald Milton carried his burden of persuasion in the

instant case by demonstrating that the reasons proffered by the

DCASR for his discharge, as well as its reasons for failing to

afford him an opportunity to improve his performance, were not

true. That is all the law requires of him, and he is not

required to present direct evidence of discrimination, nor to

rebut any possible reason for his discharge other than that

articulated by the DCASR. The District Court's conclusion that

Milton, while successfully rebutting the reasons advanced for

the DCASR's employment decisions, had nonetheless failed to

prove that the DCASR's conduct was motivated by racial bias is

contrary to the evidence and the Court's own findings and should

be reversed. At the very least, the cause should be remanded

with instructions to review the evidence under the standard

mandated by the Supreme Court, which prohibits basing a Title

VII determination on the absence of direct evidence of

discrimination, or to afford Milton an opportunity to rebut the

unarticulated reason found by the Court to have been the true

reason for his discharge.

Of Counsel:

Julian L. Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Gail J. Wright

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

NAACP Legal and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Respectfully submitted,

Daniel I. Schlessinger

Hugh C. Griffin

Diane I. Jennings

LORD, BISSELL & BROOK

115 S. LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60603

(312) 443-0600

Attorneys for

Plaintiff-Appellant

Donald L. Milton

28

APPENDIX

STATEMENT PURSUANT TO CIRCUIT RULE 30

Pursuant to Circuit Rule 30(c), counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant

Donald Milton states that all of the materials required by Circuit

Rule 30(a) and (b) to be included in the appendix to appellant's

brief are included herein.

LORD, BISSELL & BROOK

By:

Diane I.

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

Donald L. Milton

A-l

pHt ̂ iUt

ftV. t /H * )

MOTION:

USio/J + 1 U * l.LQ13JL&23\

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT, NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS, E t »TERN DIVISION

^ t & L u J L £ ^

Hint of Assi|

Judge ot M agist

Sitting Judge/ Mag If Other

Thin Assigned Judge/Mag

Case N u m b e r

Case

Title

f V c f f 4 2 -

Date

/ L l l l t terfj 7 . / 'ff'7

L'

[In the following box (a) indicate the party filing the motion, e.g., plaintiff, defendant, 3d-party

plaintiff, and (b) state briefly the nature of the motion being presented]

AUG 3 1 19CT

WET ENTRY: (The balance o f this form is reserved for notations by court staff.)

| x ] Judgment is entered as follows: (2) | | [Other docket entry:}

l»rthe defendants' and against the plaintiff, reasons for decision are contained in

court's oral opinion in open court.

Filed motion of [use listing in “MOTION” box above}.

Brief in support of motion dtK__________ _________

Answer brief to motion due______________________

H e aring

Ruling on-

. Reply to answer brief due.

_________set for_________

Status hearing o continued to | | set for | | reset for

Pretrial conference | | held | | continued to [ | set for £

' j set for [ j reset for_____________________________

reset for.

. a t .

.a t .

Trial

Bench trial ( ( jary trial | ) Hearing held and continued to .

This case is dismissed I without

D

I with prejudice and without costs j ] by agreement

| | FRCP 4(j) (failure to serve) [ [ General Rule 21 (want of prosecution) [ | FRCP41(a)(l) |

(For further detail see | | order on the reverse of d order attached to the original minute order form.)

pursuant to

FRCP 41 (a)(2)

No notices required.

Notices mailed by judge's staff.

Notified counsel by telephone.

Docketing to mau! notices.

£ Ma.l AO 45C fcrT

si CoP> to judge magistrate

courtroom

deputy’s

initials

tic

fcv, V

~ G j

Date/time received in

central Clerk’s Office

3 ~

AUG 2 8 1987

AUG-g-B

N L f

A - 2

AO <50 (Rev. 5/85) J u d s ™ " 'ln • Civil Ct»e •

d o c k e t e d

AUG 88 1987

<

Pntteb Jitfatee district (Em.rt

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS

Eastern Division v>

M il t o n

V.

JUDGMENT IN A CIVIL CASE

W e in b e rg e r , e t a l .

CASE NUM BER: 84 C 8892

D Jury Verdict This action cam e before the Court for a trial by jury. The issues have been tried and the jury

has rendered its verdict.

ifDecision by Court. This action cam e to trial or hearing before the Court. The issues have been tried or

heard and a decision has been rendered.

IT IS ORDERED AND AD JU D G ED judgment is entered for the defendants’ and against the

plaintiff, reasons for decision are contained in the court's oral opinion in open court

»

Minute Order Form

((«*. 4/*r«) culing mtn. for reconsideration

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT, NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS, EASTERN DIVISION

Ita of Assigned 1 Sltt,n* Mag If Other

judge or Magistrate âui rlU T lK eC t J Than Assigned Judge/Mag.

Case Number 84 C 8892 October 22, 1987 9:15

Case

Title

Donald li. Milton v Mr. Casper Weinberger

[In the following box (a) indicate the party filing the motion, e.g., plaintiff, defendant, Id-party

u u‘ ' plaintiff, and (b) state briefly the nature of the motion being presented]

lain t i f f * s motion for reconsideration is denied for the reasons stated in open

Filed motion of (uk listing in “MOTION” box above}

Brief in snppoet o f motion due

Aniwet brief to motion duej j Hearing

Ruling

Reply to answcT brief due.

__________ let for_________ . a t .

Status hearing I I held ( I continued to I I set for | 1 moot fee ____

Fret rial conference | [ held j f continued to I I set for j | re—t for.

Trial 1 l « » f o r | I w ort far----------------------------------------------------------- ---

. a t.

L e t t .

. a t .

Bench trial f ) Jury trial _ ] | Hearing held and continued to . . a t .

This case is dismissed j 1 without I I with prejudice and without costs | j by agreement ( pursuant

FRCF ♦(j)(faih»re to serve) | | General Rule 21 (want'of prosecution) [ | FRCP 41(a)(1) | j FRCP 41 (a)(2)

(For further detail see I

V

No notices required.

Notices mailed by judge's staff.

Notified counsel by telephone.

Docketing to mail notices.

Mail AO ajOfc iT ,

Copy to judge magistrate

courtroom

deputy**

initials /

d L

.......... .................. f - . —— T------

9 K 8 « iZ 10 0 i/ 4 fad

&0CT i- 3 »a87

1 flfrrrmr-

Oate/time received in

central Clerk's Office

number

of notices

mailing dpty.

initials

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS

EASTERN DIVISION

DONALD L. MILTON,

Plaintiff,

vs.

CASPER WEINBERGER,

etc., et al.,

Defendants.

)

)) Docket No. 84 C 8892

| Chicago, Illinois

; August 27, 1987

j 11:00 o'clock, a.m.

)

)

)

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS

BEFORE HONORABLE PAUL E. PLUNKETT

PRESENT:

For the Plaintiff: MR. DANIEL I. SCHLESSINGER

115 S. LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois

For the Defendants: MR. FREDERICK H. BRANDING

Asst. United States Attorney

U.S. Courthouse, Chicago, II.

Court Reporter: Joseph Betz

U.S. Courthouse

Chicago, II.

2

THE CLERK: 84 C 8892, Milton vs. Weinberger.

Decision on trial.

MR. SCHLESSINGER: Good morning, your Honor. Daniel

Schlessinger for the plaintiff.

MR. BRANDING: Good morning, Judge. Frederick Brand

ing on behalf of defendants.

THE COURT: Well, why don't you folks be seated. I

am going to read, as I told you I would, an opinion. I will say

before I begin this that all cases under Title VII and

accompanying statutes on racial discrimination, indeed, any

discrimination, give any finder of fact a certain difficulty,

because a court is trying to devine, almost, the intent of one

actor in a story.

I found this case particularly difficult to deal

with. I have reviewed all of the file, I have reviewed the pre

trial order, the stipulations, and paid close attention to the

closing arguments by both sides.

I conclude as follows:

I will find as a fact all of the stipulations

of uncontested facts which the parties have given me in the pre

trial order. I will not read them into the record, but they

consist of nine stipulations contained on Pages 1, 2 and 3 of

the pretrial order-

The case as presented, at least as I found,

demonstrated that the plaintiff had shown a prima facie case.

A-6

3

The government, the United States Department of Defense, and

the other defendants, came forward with a proposed legitimate

reason for the discharge of Mr. Milton, and Mr. Milton, both in

his case in chief and in rebuttal, attempted to demonstrate

that that legitimate reason was pretextual.

The important facts as I find them in the case

are as follows:

First, Mr. Vann, the supervisor of Mr. Milton,

was the person who actually hired Mr. Milton and the person

who supervised, or at least was responsible for Mr. Milton

throughout his employment, which lasted some ten or eleven month

Mr. Milton was at all times a probationary

employee under the applicable federal rules and regulations,

and was entitled to be fired for any reason whatsoever, of

course not including discrimination. But he was not a person

who could only be fired for cause. He could be fired for any

reason that was legitimate and not discriminatory.

Mr. Vann as the supervisor selected Mr. Milton

from several candidates, and of at least the ones he interviewed

Mr. Milton was the only black candidate. So it is difficult to

see initially that Mr. Vann demonstrates any discrimination,

at least as the scenario begins.

Mr. Vann testified that he was not particularly

pleased with the plaintiff's performance during the course of

the ten or eleven months that Mr. Milton was there, and he

A-7

4

attempted to set forth reasons as to why he was not pleased.

Before I get to those, I have to say I will accept Mr. Vann's

testimony, which is contested by Mr. Milton, that there was a

meeting in April at which Mr. Vann voiced some of his concerns

with Mr. Milton's performance.

I make that finding largely because in judging

credibility I believe Mr. Vann did that; I note it is not properl

handled on the employee card but I discount that, and, as I say,

I will accept that there was a meeting at which Mr. Vann pointed

out areas in which Mr. Milton could improve.

It is uncontested that Mr. Vann gave an extremly

qood appraisal or evaluation of Mr. Milton in July, exactly,

July 29th, 1983, which is Plaintiff's Exhibit 4. In a sense

this is a two-edged sword for the plaintiff. It certainly shows

that at that point in time Mr. Vann perceived Mr. Milton to be

doing a decent if not a good job, and Mr. Van gave a meaningful,

favorable statement of Mr. Milton's work.

It also, however, tends to undercut somewhat the

argument that Mr. Vann based his decisions on discrimination,

since if Mr. Vann was a person with that bent it would be hard

to imgine that he would give this kind of a review to a

probationary employee.

So, as we reach the end of July, I do not see

that I am persuaded that at that point at least Mr. Vann is

engaged in any sort of discrimination against Mr. Milton. As I

A-8

5

say, he hired him, he was his supervisor, he met with him in

April to give him some corrective and constructive comments, and

he gave him a good review.

The problems apparently with Mr. Milton's em

ployment became significant by early October. Mr. Vann became

upset with what he perceived was a failure by Mr. Milton to

properly perform his tasks of planning for the computer room

or the -- I have forgotten the exact name of that room —

MR. BRANDING: ADP, Automatic Data Processing.

THE COURT: Right. Mr. Van perceived that Mr. Milton

as a planner had actually left employees in a construction area,

and Mr. Milton rebutted that by showing a letter which at least

somewhat demonstrated that it was really Mr. Vann, not Mr.

Milton, who made the change that led to this problem, and I am

prepared to find that Mr. Vann was essentially mistaken and

wrong in his criticism of Mr. Milton for this job. But that is

not tantamount to finding discrimination.

I will turn now to some of the points that Mr.

Schlessinger made, because he gave a splendid closing argument

and I have to deal with some of these. It is true that Mr. Vann

apparently called Mr. Milton a walking joke, and, indeed, Mr.

Vann repeated that testimony on the stand, that he had said that,

and apparently he feels that way.

Mr. Milton's counsel argues that this shows

that Mr. Vann is untruthful because no one who perceived another

A-9

6

as a walking joke would give him any sort of a good evaluation

after six months of work to encourage him, since you don't

encourage someone who has no redeeming abilities and no meaning

ful way to improve.

The problem with the argument is that Mr. Vann --

we're uncertain as to when Mr. Vann formed that judgment, and

I conclude from the evidence that Mr. Vann, while annoyed and

unhappy with Mr. Milton from time to time, did not really come

to this conclusion until after the evaluation.

Mr. Milton presented two witnesses at DCASR who

said that Mr. Milton did a good job, and I accept their testi

mony as true. They were not Mr. Milton's supervisors, however,

and they were in less than a perfect position to judge the

quality of his work. Their testimony was more that they had

no problems with him personally and that they didn't see any

problems with the work that he had done for them. But those

are on two limited jobs.

Mr. Vann failed to follow some of the government

regulations, but I don't draw any adverse inference from that.

In short, what I am finding is that if this were

a case of discharging an employee without cause and without due

process, that the government would lose and that Mr. Milton

would win, because I don't think there was a particularly — the

problems that Mr. Vann had I doubt would ever rise to a for-cause

dismissal, particularly in light of this record.

A-l 0

7

The difficulty, however, for me, is that the

government is not defending that kind of a case; they are

defending a claim of discrimination by Mr. Vann.

Mr. Milton was a probationary employee. Mr.

Vann, and I accept his testimony, was upset by Mr. Milton's —

the way in which he dealt with several of his projects, and he

was upset by the way Mr. Milton handled criticism.

I conclude that while the plaintiff has shown

that many of Mr. Vann's complaints were not so serious as to

permit a for-cause termination here, that I cannot and I am not

persuaded that the plaintiff was discharged because of a dis

criminatory approach or thinking or conduct by Mr. Vann.

Accordingly, after a good deal of thought I will

enter judgment for the defendants and against the plaintiff, and

that will conclude the findings in the case.

As I say, it was a difficult, difficult case,

and, Mr. Schlessinger, I am not all-knowing, and so if you

perceive after getting this transcript that there are some areas

that you can point out to me where I am mistaken, I not only

will permit but will welcome a motion to reconsider this with

your additional thinking on the questions.

MR. SCHLESSINGER: Thank you. I appreciate that

opportunity, your Honor.

THE COURT: Thank you both. The case was well

presented by both sides.

A-l 1

8

MR. BRANDING: Judge, if I may just for the record

make a comment to compliment Mr. Schlessinger. As court-

appointed counsel, I think he did a superb job. He did a very

good job as an advocate. He was tough, but, at the same time,

he was always fair. There was no unreasonableness to any of his

positions.

THE COURT: As I said, it was a spelendid closing

argument, and I wish there were ways to be certain, absolutely

certain, but in life there is no way to, and it is my best

judgment. He gave me an awful lot to think about.

As you know, I had to push this over, because

I thought about it all weekend and still wasn't certain how

this case should come out.

MR. BRANDING: That is certainly the dilemma that

every trier of fact has to face in every case.

THE COURT: Yes, but I have them all the time. I have

never had one that — I have had a few, but this is a rare

instance where I had a lot of trouble with it.

Mr. Milton, I know you’re very disappointed that

you have lost this case. As I told your lawyer, I will be happy

to look at it again. As I tried to tell you in that opinion,

while I didn't find that Mr. Vann discriminated against you, I

am also not applauding his decision to terminate you.

I think in some ways he must be — at least that

is the inference I draw — a rather impatient man who at times is

A-l 2

9

difficult to get along with, and it is really -- it leaves

you without a remedy, in my view, because you see him as a

discriminator.

I didn't have the ability to protect you as a

permanent employee but only a probationary one.

All I can tell you, Mr. Milton, is that I did

my best. I found from the evidence, and I'll say on the record,

that I think you are a qualified engineer, and I am sorry that

the period with the government was not more satisfactory to you.

Maybe there will come a time when the government — and, I don't

know, maybe the government in light of some of the things I have

said here might take another look at you, because I think you

do a good job, and I didn't find that you didn't. I just

couldn't find discrimination by your boss.

Thank you, folks.

MR. SCHLESSINGER: Thank you for your careful con

sideration, your Honor.

MR. BRANDING: Thank you, Judge.

C E R T I F I C A T E

Transcript above certified true and complete

A-13

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS

EASTERN DIVISION

DONALD L. MILTON, )

)Plaintiff, )

)

vs. )

)CASPER WEINBERGER, )

et al., )

)Defendants. )

Docket No. 84 C 8892

Chicago, Illinois

October 22, 1987

9:20 o'clock, a.m.

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS

BEFORE HONORABLE PAUL E. PLUNKETT

PRESENT:

For the Plaintiff: MR. DANIEL I. SCHLESSINGER

Lord, Bissell t Brook

Chicago, II.

For the Defendants: MS. EILEEN KARUTZKY

Asst. United States Attorney

U.S. Courthouse, Chicago, II.

Court Reporter: Joseph Betz

U.S. Courthouse

Chicago, Illinois

A-14

2

THE CLERK: 84 C 8892, Milton vs. Weinberger. Ruling.

MS. MARUTZKY: Good morning, your Honor. Eileen

Marutzky for Defendant Weinberger.

MR. SCHLESSINGER: Good morning, your Honor. Daniel

Schlessinger representing the plaintiff.

THE COURT: Good morning. I reviewed what you filed,

Mr. Schlessinger, and you touched on a point that caused me

a problem in the decision, that is, if I wasn't fascinated with

the government's legitimate explanation what inference is to

be drawn, and I gave that a lot of thought, and I don't change

my opinion, Mr. Schlessinger.

If I'm not convinced that the reasons espoused

by the government constitute a good ground to discharge him,

I still am convinced that the actual reason for discharging

him was because the boss, rightly or wrongly, simply didn't

get along with him, and I see no discrimination. So I am

going to deny the motion to reconsider, and perhaps someday

I'll get a definitive answer on the question.

MR. SCHLESSINGER: We thank the Court very kindly

for its careful consideration.

MS. MARUTZKY: Thank you, your Honor.

THE COURT: All right.

C E R T I F I C A T E

Transcript above certified true and complete