Plaintiffs' Brief Supporting Motion for Additional Relief

Public Court Documents

February 23, 1987

34 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Brief Supporting Motion for Additional Relief, 1987. aa87fe97-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aec63fc0-9b2a-4e05-93c1-75e6ca9a77da/plaintiffs-brief-supporting-motion-for-additional-relief. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

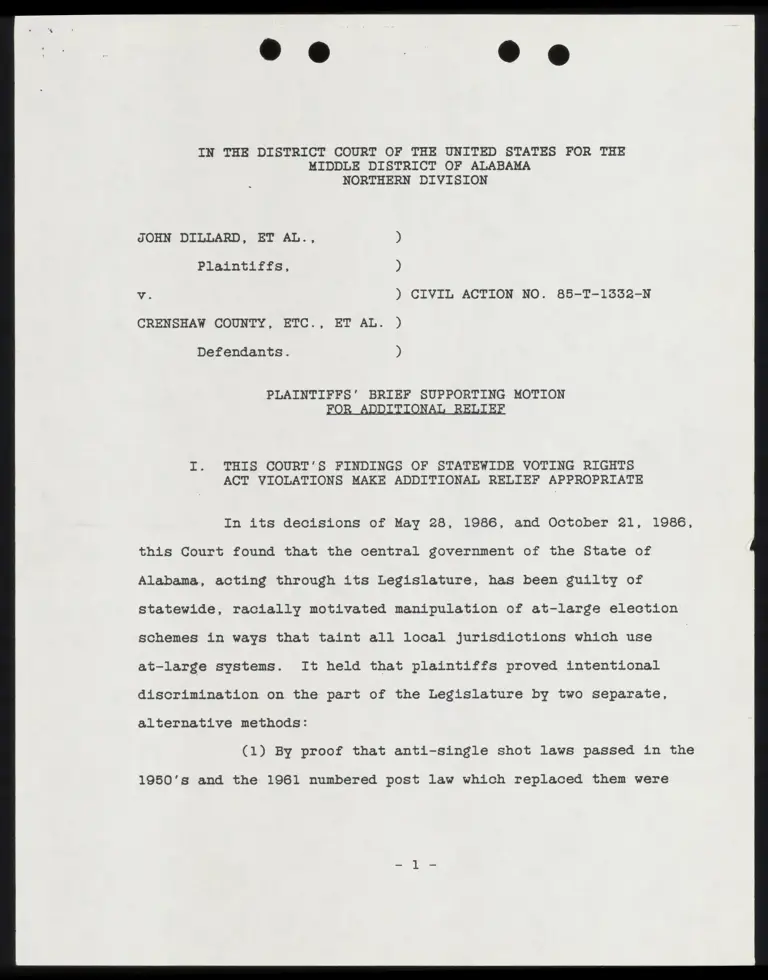

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

JOHN DILLARD, ET AL., )

Plaintiffs, )

v. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ETC., ET AL. )

Defendants. )

PLAINTIFFS’ BRIEF SUPPORTING MOTION

FOR ADDITIONAL RELIEF

I. THIS COURT'S FINDINGS OF STATEWIDE VOTING RIGHTS

ACT VIOLATIONS MAKE ADDITIONAL RELIEF APPROPRIATE

In its decisions of May 28, 1986, and October 21, 1986,

this Court found that the central government of the State of

Alabama, acting through its Legislature, has been guilty of

statewide, racially motivated manipulation of at-large election

schemes in ways that taint all local jurisdictions which use

at-large systems. It held that plaintiffs proved intentional

discrimination on the part of the Legislature by two separate,

alternative methods:

(1) By proof that anti-single shot laws passed in the

1950's and the 1961 numbered post law which replaced them were

intended to minimize black voting strength.

These racially inspired numbered place laws exist and

operate today.

Therefore, regardless of the reasons for which the

at-large systems were put into place in various

counties, including the five counties sued here, the

numbered place laws have inevitably tainted these

systems wherever they exist in the state. In adopting

the laws, the state reshaped at-large systems into more

secure mechanisms for discrimination. And as the

evidence makes clear, this reshaping of the systems was

completely intentional.

Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 640 F.Supp. 1347, 1357 (M.D.Ala.

1986) (emphasis added).

(2) By proof of "a pattern and practice of using

at-large systems as an instrument for race discrimination." 640

F.Supp. at 1361.

[Tlhe Alabama legislature ... has consistently enacted

at-large systems for local governments during periods

when there was a substantial threat of black

participation in the political process. This evidence,

set against the background of the state's unrelenting

and undisputed history of race discrimination,

convinces the court that the enactment of the at-large

systems during such periods was not adventitious but

rather racially inspired.

Id. (emphasis added).

This Court went on to conclude that the Legislature's

racially motivated manipulation of laws governing at-large

systems for local governments violated Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. section 1973, with respect to the five

counties then defending their election systems, because the other

two requirements for establishing a statutory claim were

satisfied: proof that the laws have a present adverse impact on

black voters and failure of the counties to rebut plaintiffs’

prima facie case. 640 F.Sup. at 1360, 1361.

There are over 200 municipalities and over 30 county

school districts with substantial black populations still using

the tainted at-large election system. Available evidence shows

that, like the nine counties against whom judgments have already

been entered in this action, these jurisdictions display the same

characteristics which, in the context of at-large elections, deny

blacks equal access to the political process.

The election systems in the five counties were

determined to be in violation of the Voting Rights Act because of

the state legislature's purposeful discrimination plus the

following:

(1) "three structural features particularly

relevant”:

(a) at-large voting methods,

(b) numbered posts, and

(c) a majority vote requirement, 640 F.Supp.at 1352;

(2) "a clear history of racially polarized elections

for both state and county officials", and

(3) the absence of black elected officials, id. at

Vhen this motion for additional relief is set for

evidentiary hearing, plaintiffs will be prepared to show that

each of the identified cities and school boards is elected by a

system that includes all three relevant structural features, that

recent elections in each jurisdiction exhibited racially

polarized voting, and that in most cases no blacks have been

elected (or, in a few cases, elected on disproportionately few

occasions). This constitutes evidence that "the system continues

today to have some adverse racial impact", id. at 1354, in each

jurisdiction. Coupled with the existing findings of racially

motivated statewide legislation, this impact evidence should be

sufficient to shift the burden of rebutting prima facie Section 2

violations "to the scheme’'s defenders". Id. at 1355.

Plaintiffs emphasize that the quantity and quality of

present impact proof they are prepared to adduce for some 250

local government election systems is necessarily less

comprehensive than the evidence ordinarily expected in

case-by-case trials under the Section 2 "results" standard. We

contend that the Voting Rights Act does not demand such strict

proof in the circumstances of this case for the following

reasons:

a. As this Court noted, the "intent" and "results"

standards are alternative methods for establishing a Section 2

violation. 640 F.Supp. at 1353. With the exception of Pickens

County, the county commissions enjoined by this Court were found

to have at-large systems that violated Section 2 according to the

intent standard. Because of the large number of county

commissions challenged, plaintiffs tactically chose to prove a

statewide intent case. The Court recognized that, once racial

motives for the statewide at-large laws were established, the

criteria for proving present-day adverse impact are "less

stringent and may be met by any evidence that the challenged

action is having significant impact on black persons today." Id.

at 1354 n.5 (citation omitted). The evidence plaintiffs propose

to adduce for each of the additional local election systems

provides a sufficient overview of their disadvantageous operation

against blacks to create a rebuttable presumption of adverse

impact, in light of the laws’ intended statewide effects and in

light of the fact that at-large election systems have been the

subject of court ordered change in over 30 local jurisdictions

1

already in Alabama.

1

At-large election systems have been struck down by court

orders in the following county jurisdictions: Montgomery, Mobile,

Marengo, Pike, Dallas, Tallapoosa, Henry, Russell, Hale,

Tuscaloosa, Monroe, Conecuh, Barbour, Choctaw, Clarke, Talladega,

Crenshaw, Pickens, Coffee, Calhoun, Lawrence, Etowah, Escambia

and Lee.

At-large election systems have been struck down by

court orders in the following municipalities: Mobile, Troy,

Enterprise, Jackson, Opelika, Tuscaloosa, Montgomery, Bessemer,

Gadsden and Marion.

This list is probably incomplete.

b. The Court’s alternative finding of intentional

discrimination using the pattern and practice method and relying

on precedents like Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973), suggests the appropriateness of a school desegregation

approach to remedying Voting Rights Act violations that

potentially exist statewide. Just as the State of Alabama has an

obligation to dismantle the vestiges of de jure school

segregation in all its school districts, it has a corresponding

obligation to remedy any continuing effects of its de jure policy

of racial vote dilution in every political subdivision that uses

at-large elections. Only a minimal showing of a continuing

violation in particular jurisdictions should be required of the

victims of official voting discrimination to shift the burden to

the state to demonstrate that, in fact, its offensive policy no

longer disadvantages blacks there. The Court has noticed the

rule of school desegregation caselaw that proof of discriminatory

intent in one part of a school system creates a presumption that

invidious intent exists in other parts where schools are

segregated. 640 F.Supp. at 1361 n.7, citing Keyes, supra. In the

context of de jure discriminatory at-large voting schemes, proof

that blacks are significantly underrepresented in at-large

Jurisdictions by itself should be analogous to proof that

particular schools are still segregated.

c. An "intensely local appraisal” is required to

® oO ® ©

establish a Section 2 claim only when the Court must proceed

under the ¥Yhite v. Regester results standard. Once statewide

intentional discrimination has been established with respect to a

voting practice, like at-large elections, a requirement that

extensive proof still be adduced for each of hundreds of local

jurisdictions would frustrate the Congressional purpose of the

Voting Rights Act. The Court has acknowledged "the expressed

policy of the Voting Rights Act that voting discrimination be

dealt with ‘not step by step, but comprehensively and finally’'."

640 F.Supp. at 1369, quoting S.Rep.No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

5. Speedy enforcement of the Act should be given a high priority:

"the court does recognize that with each election the [unlawfull

at-large systems impermissibly dilute the vote of thousands of

black citizens and thus must be eliminated as soon as possible."

Id. at 1362. Where the state legislature has carried out an

invidious design to dilute black voting strength, there is at

least some presumption that the design has succeeded in each

jurisdiction operating under the affected laws. To require

further extensive proof of present adverse effects in hundreds of

Alabama jurisdictions would take many years and would undermine

enforcement of the Act.

II. THE STATE OF ALABAMA IS THE PROPER PARTY TO DEFEND

THE STATEWIDE CLAIM AGAINST ITS LOCAL JURISDICTIONS

AND TO SUPERVISE DEVELOPMENT OF REMEDIAL PLANS

The state legislature is the entity responsible for

the use of tainted at-large systems in the identified local

Jurisdictions. 640 F.Supp. at 1361.

The State Is Ultimately Responsible for Remedying

the Continuing Effects in Each of its Subdivisions

of Laws That Violate the Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act was intended to remedy a

“century of obstruction" and "to counter the perpetuation of 95

years of pervasive voting discrimination," City of Rome v.

United States, 446 U.S. 156, 182 (1980), by “creatl[ingl a set of

mechanisms for dealing with continued voting discrimination,not

step by step, but comprehensively and finally." §S.Rep.No.

97-417, p.5 (1982). Sections 4 and 5, which suspend the use of

tests and devices and require that covered jurisdictions seek

preclearance of electoral changes, form the "heart of the Act,"

because they "shift the advantage of time and inertia from the

perpetrators of the evil to its victims," South Carolina v.

Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 315, 328 (1966). Thus, sections 4 and 5

constitute, along with section 2, a concerted plan of attack on

practices, standards, and devices that discriminate against

minority voters. Cf. S.Rep.No. 97-417, pp.5-6 (1982).

Section 2 of the Act contains a broad prohibition of

“the use of voting rules to abridge exercise of the franchise.”

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. at 301. The legislative

history of the 1982 amendment of section 4 shows that Congress

intended to make states affirmatively responsible for dismantling

discriminatory electoral systems within their territories. Thus,

a state’s continued acquiescence in its subdivisions’ use of

election systems which result in the dilution of minority voting

strength violates section 2.

Originally, coverage under the special provisions of

sections 4 and 5 of the Act was triggered by a finding that the

state or separately covered subdivision had used a test or device

as a prerequisite to registration or voting and had a history of

depressed political participation. Section 4(b). The triggering

mechanism was designed to identify and target those jurisdictions

which had historically discriminated on the basis of race in

restricting the franchise. A covered jurisdiction could "bail

out," or free itself from the Act's special remedies, by showing

that, for a specified period of time, it had not used the test or

device with the purpose or effect of denying or abridging the

right to vote on account of race. Section 4(a).

In 1982, Congress found a continuing need for the

special remedies provided by sections 4 and 5. Preclearance

remained necessary for some jurisdictions both "because there are

‘vestiges of discrimination present in their electoral system and

because no constructive steps have been taken to alter that

fact.'" H.R.Rep.No. 97-227, p.37 (1982). Thus, Congress amended

the bailout provision to ensure that jurisdictions would not be

released from the special remedial provisions of the Act merely

because of the passage of wie In place of the existing bailout

provision, which imposed on covered jurisdictions only a passive

obligation not to use tests or devices that had the purpose or

effect of denying minorities the right to vote, Congress

substituted a bailout formula that imposed on covered

jurisdictions an affirmative responsibility to ensure minorities

the right to vote and to have their votes count. It hoped that

"a carefully drafted amendment to the bailout provision could

indeed act as an incentive to jurisdictions to take steps to

permanently involve minorities within their political process

." H.R.Rep.No. 97-227, p.37 (1982); see also id. at 32;.

S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.2 (1982) (new bailout provision requires a

2

The then-existing bailout formula permitted covered

jurisdictions to bail out by showing that they had not used a

test or device in a discriminatory manner in the preceding 17

years. Since section 4 had suspended the use of tests and

devices in the originally covered jurisdictions on August 6,

1965, such jurisdictions would automatically come out from under

sections 4 and 5 on August 6, 1982. See S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.43,

n.162 (1982).

- 10 -

showing that jurisdiction has "taken positive steps to increase

the opportunity for full minority participation in the political

process, including the removal of any discriminatory barriers");

id. at 43-44.

The new bailout formula, which took effect on August

5, 1984, provides, in pertinent part, that the declaratory

judgment releasing a jurisdiction from the requirements of

sections 4 and 5

shall issue only if [the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia] determines that during

the ten years preceding the filing of the action, and

during the pendency of such action--

(F) such State or political subdivision and all

governmental units within its territory--

(1) have eliminated voting procedures and

methods of election which inhibit or dilute equal

access to the electoral process;

(ii) have engaged in constructive efforts to

eliminate intimidation and harassment of persons

exercising rights protected under this Act; and

(iii) have engaged in other constructive

efforts, such as expanded opportunity for convenient

registration and voting for every person of voting age

and the appointment of minority persons as election

officials throughout the jurisdiction and at all stages

of the election and registration process.

(Emphasis added). The legislative history of this new bailout

provision shows that Congress intended to impose on covered

states an affirmative responsibility to police the electoral

-iyY

behavior of their political subdivisions and to remedy the

continuing effects in each of its subdivisions of state laws

adopted with the purpose or having the effect of denying citizens

the right to vote on account of race.

The most detailed discussion of the states’ special

responsibilities under the Act occurred in the context of a floor

debate in the House concerning a proposed amendment to section 4

that would have permitted states to bail out even if not all

their political subdivisions met all the criteria for bailout.

The House rejected that amendment overwhelmingly.

Representatives who spoke in opposition to the proposed amendment

stressed both the special constitutional role of states in

protecting the right to vote and the extent of states’ control

over their subdivisions’ electoral systems. (See, e.g., 127

Cong .Rec. HB6969 (daily ed., Oct. 2, 1981) (Rep. Sensenbrenner)

(states have broad control over subdivisions and ample authority

to make them obey the Act); id. at H6970 (Rep. Fish) (noting that

states "are mentioned specifically in the language of the 15th

amendment" and "have an important fundamental power with regard

to the franchise. I think, along with that authority goes the

responsibility of States to protect the right to vote"); id.

(Rep. Frank) (same); 1d. at HE6971 (Rep. Chisholm) (states "have a

constitutional and a moral responsibility to insure that the

local governmental units under their jurisdiction meet the

- a,

standards of the act").

Of particular salience to this case, several

representatives pointed to Alabama legislation to support their

contention that states must be made responsible for the

compliance of their subdivisions. Representative Washington

relied on Alabama's local reregistration statutes to illustrate

the danger of relieving states of the obligation of assuring

compliance with the Act by their subdivisions:

[I]t will be very difficult to determine when a

violation flowed from a county provision in the first

instance, from a provision of state law, or as a

consequence of a county's interpretation or

administration of a State law of general

applicability. And throughout all of this would remain

the issue of whether the State knew or should have

known that it was legislatively acquiescing to a county

practice that violated the act.

127 Cong .Rec. H6968 (daily ed., Oct. 2, 1981). Moreover,

Representative Washington's explanation of the way in which

states historically acted to restrict the franchise mirrors this

Court's description of Alabama's intentional manipulation of

county commission elections. Compare Dillard v. Crenshaw

County, 640 F.Supp. 1347, 1356-59 (M.D.Ala. 1986) with 127

Cong .Rec.H6968 (daily ed., Oct. 2, 1981) ("there is a tradition

of the State legislature overruling or preempting other

jurisdictions in these matters. Remember it was the Stae [gic]

legislatures which called constitutional conventions to

disenfranchise blacks."). Representative Sensenbrenner also used

Alabama's local laws as an example to support his assertion that

states have broad control over subdivisions and ample authority

to make them obey the Act. Id. at HE969. In light of this debate,

the House Report expressly stated that the new bailout formula

"retain[s] the concept that the greater governmental entity is

responsible for the actions of the units of government within its

territory, so that the State is barred from bailout unless all

its counties/parishes can also meet the bailout standard "

H.R. Rep.No. 97-227, p.33 (1982).

The Senate Report, which the Supreme Court has

characterized as an "authoritative source" for determining

Congress’ purpose in enacting the 1982 amendments, Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U.S. __, 92 L.E4d.2d4 25, 42 n.7 (1986), took the

same approach. "It is approporiate to condition the right of a

state to bail out on the compliance of all its political

subdivisions, both because of the significant statutory and

practical control which a state has over them and because the

Fifteenth Amendment places responsibility on the states for

protecting voting rights." §S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.56 (1982). In

particular, the Report noted that "States have historically been

treated as the responsible unit of government for protecting the

franchise," id. at 57, because "the Fifteenth Amendment places

responsibility on the states for protecting voting rights,” id.

at 69. Since state laws govern local electoral practices, the

- 14

states ultimately are responsible for ensuring that none of their

subdivisions denies minorities the right to vote. Id. at 57.

In sum, the 1982 amendments of section 4, the

centerpiece of the Act's special protections, were intended to

place upon states an affirmative obligation to dismantle

still-existing barriers to minority political participation. A

state's failure to undertake this duty should not only result in

its continued coverage under section 5 but should also be viewed

as a violation of section 2, which prohibits the states from

imposing or applying any voting standard practice or procedure

which results in the denial or abridgment of the right to vote.

As the 1982 House Report made clear:

Under the Voting Rights Act, whether a discriminatory

practice or procedure is of recent origin affects oniy

the mechanism that triggers relief, i.e., litigation

[under section 2] or preclearance [under section 5].

The lawfulness of such a practice should not vary

depending on when it was adopted, i.e., whether it is a

change. :

H.R.Rep.No. 97-227, p.28 (1982). The failure of Alabama to

dismantle its discriminatory electoral systems represents a

continuing violation of the Voting Rights Act and the Fifteenth

Amendment.

- 15 -

The State of Alabama Is Subject to Suit Under

Section 2 of the Votlng Rights Act

A proper reading of the amended Voting Rights Act and

eleventh amendment jurisprudence demonstrates that sovereign

immunity is no bar to the claims by these private plaintiffs

against the State of Alabama. This Court has noted the three

exceptions to the state's eleventh amendment immunity from suits

by private litigants. Allen v. Alabama State Bd. of Education,

636 F.Supp 64 (M.D.Ala. 1986), rev'd on other grounds, __F.2d.__

(llth Cir., Nov. 25, 1988):

(1) The Ex Parte Young exception. Prospective

injunctive relief can be sought against state officials who

violate the laws and Constitution of the United States. 636

F.Supp at 75-76, c¢lting Green v. Mapsour, 106 S.Ct. 423, 428

(1985); Pennhurst State School & Hospital v. Halderman, 465 U.S.

89, 105 (1984). Plaintiffs here rely on the Young exception in

seeking to have the state Attorney General added as a party

defendant. However, for reasons already stated, the state

legislature itself is guilty of the intentional dilution of

blacks’ voting rights, and the responsibility for eliminating all

vestiges of the central government's wrongdoing should fall not

just on one state official but all departments, agencies,

officers and political subdivisions of the State of Alabama.

- 168 -

Plaintiffs believe that the best and most appropriate way to

insure that all elements of the state share in the legal, :

financial and practical responsibility for vindicating the voting

rights of black citizens is to add the state as a defendant in

its own name.

(2) The congressional abrogation exception.

Exercising its authority under the Commerce Clause, section 5 of

the fourteenth amendment or section 2 of the fifteenth amendment,

Congress can abrogate the eleventh amendment immunity of the

state. 636 F.Supp. at 76, citing Atascadero State Hospital v.

Scanlon, 105 S.Ct. 3142, 3145 (1985); Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427

U.S. 445 (1976). The "abrogation" exception is the one plaintiffs

rely on in the instant case.

(3) The state waiver or consent exception. Under

proper circumstances, which will not be enumerated here, the

state can walve its eleventh amendment immunity. 636 F.Supp at

76, clting Atascadero, supra, 105 S.Ct 3145 n.l; Edelman v.

Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 673 (1974). Plaintiffs do not rely on the

walver exception in the instant case.

So far as we can determine, no court has squarely

addressed the question of congressional abrogation of states’

eleventh amendment immunity by the Voting Rights Act. A state

agency was successfully sued by private citizens in Allen v.

State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1968). The Supreme

- 17 -

Court's decision upheld a private cause of action to enforce

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, but it did not squarely

address the sovereign immunity question. However, the long and

somewhat complicated eleventh amendment jurisprudence makes it

clear that Congress has waived the state's immunity from suit

under Section 2 of the Act.

States and their agencies can be sued by private

parties when Congress, exercising its power under section 5 of

the fourteenth amendment or section 2 of the fifteenth amendment,

unequivocally expresses its intent to abrogate their eleventh

amendment immunity. Gomez v. Illinois State Board of Education,

F.2d (75h Cir., Jan. 30, 1987), Lexis Op. at 7, gclting

Atascadero, supra, 105 S.Ct. at 3145 (a copy of the relevant

portions of the Gomez opinion, taken from the Lexis service, is

attached to this brief). The issue is one of statutory

construction. For the important federal-state policy reasons

discussed by this Court in Allen v. Alabama State Board of

Education, supra, the Supreme Court has said there must be

"unmistakable language in the statute itself" containing

Congress’ unequivocal expression of intent to abrogate the

state's eleventh amendment immunity. Atascadero, supra, 108

S.Ct. 3148. It held in Atascadero that Section 504 of the

Rehabiliation Act did not unequivocally abrograte the immunity,

and in Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer it held that Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act did contain a clear expression of abrogation. The

question, therefore, is whether the statutory language of the

Voting Rights Act and its supporting legislative history meet the

criteria of unequivocal abrogation found in Fitzpatrick or fail

to do so for reasons like those in Atascadero.

There are these discernible differences between

Atascadero and Fitzpatrick:

In Atascadero:

(1) The statutory entitlement set up by Section 504

of the Rehabilitation Act used the language "No otherwise

qualified handicapped individual ... shall ... be excluded from

participation in ... any program or activity receiving Federal

Financial Assistance ...." A congressional intent that individual

legal rights should proceed against the states had to be inferred

from their inclusion in the generic class of programs receiving

federal financial assistance. 105 S.Ct. at 3149.

(2) Similarly, the remedies provided by the

Rehabilitation Act referred to those in Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act and were to be available against "any recipient of

Federal Assistance." Id. (emphasis supplied by Court). The Court

said this statutory language was not a sufficiently unequivocal

abrogation of eleventh amendment immunity, because it constituted

only a "general authorization of suit in federal court". Id.

(3) In order for states to become subject to the

=:10 =

rights of individuals provided by the Rehabilitation Act, it was

necessary for them to accept federal funding. Id. at 3149-50.

There was no indication that Congress intended to single out the

states in particular, as distinguished from other potential

recipients of funding.

(4) The Court could not find in the legislative

history of the Rehabilitation Act a clear congressional purpose

to expand the jurisdiction of federal courts and thus to enhance

federal power over power reserved by the states. 105 S.Ct. at

3148, 3150.

In Fltzpatrick:

(1) Congress in 1972 struck an explicit exclusion of

states and their political subdivisions from the definition of an

employer subject to Title VII and added to the definition of

persons who were employers "governments, governmental agencies,

[and] political subdivisions." 427 U.S. at 449 n.2. The rights

of employees covered by Title VII thus proceeded against

employers who, by definition, included the states.

(2) The remedy section of Title VII was not amended

explicitly to name states; rather, broad equitable relief in

federal court remained available against "respondents" in

general. The definition of employer as including states was

considered sufficient to connect the entitlement section with

remedy section. 427 U.S. at 449 and n.5.

w OL) im

(3) The legislative history of Title VII made it

clear that Congress intended to extend coverage to the states in

particular as employers. 427 U.S. at 453 n.9, citing S.Rep.No.

92-415, pp. 10-11 (1971).

(4) Citing inter alia a Voting Rights Act case, South

Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 308 (1966), the Court found

that abrogation of eleventh amendment immunity was part of a

“shift in the federal-state balance" brought about by the Civil

War Amendments and "was grounded on the expansion of Congress’

powers—--with the corresponding diminution of state

sovereignty--found to be intended by the Framers and made part of

the Constitution upon the State's ratification of those

Amendments ...." 427 U.S. at 455-56.

Considering the analyses in Atascadero and Fitzpatrick,

along with the rest of the eleventh amendment jurisprudence, one

can see that the Supreme Court "has never held ... that a statute

must expressly provide that it abrogates the states’ immunity

...." Gomez, supra, Lexis Op. at 7, citing Fitzpatrick, supra;

Hutto v. Finney, 436 U.S. 678 (1978).

Thus, although a federal enactment must "unequivocally"

abrogate immunity, it may do so, not in so many words,

but rather by its effect. For example, an abrogation

may be found where any other reading of the statute in

question would render nugatory the express terms of the

provision. :

Gomez, supra, Lexis Op. at 8 (citations omitted).

OY

Considering these criteria of statutory interpretation

one at a time and together, a congressional intent to abrogate

the state's eleventh amendment immunity is clear in the Voting

Rights Act. First, the entitlement language of Section 2

explicitly extends its obligations to the state: "No voting

qualifications ... shall be imposed or implied by any state or

political subdivision ...." 42 U.S.C. section 1973 (emphasis

added). Similar wording has led federal courts to find

congressional abrogation of immunity in the Equal Educational

Opportunities Act, Gomez, supra, Lexis Op. at 8 ("No State shall

deny an equal educational opportunity to an individual on account

of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin ...."), and in

the Education of All Handicapped Children Act, David D. ¥.

Dartmouth School Committee, 775 F.2d 411, 422 (1st Cir. 1985)

(unlike Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, the EAHCA "is

directed to one class of actors: states and their political

subdivisions responsible for providing public education"). 3

Second, when Congress amended the Voting Rights Act in

1982, it made clear its intention that a private right of action

5)

Two other courts of appeals have reached opposite

conclusions about abrogation of eleventh amendment immunity by

the EAHCA, but both courts summarily assumed that the EAHCA was

in all relevant respects identical to the Rehabilitation Act

without considering the differences discussed in David D.

, 796 F.2d 940, 944

(7th Cir. 19868): Doe v. Maher, 793 F.2d 1470, 1493-94 (9th Cir.

10886).

- DO

exists under Section 2. S.Rep.No. 97-417, p.30 (1982). Even

though the language in the jurisdictional section of the Voting

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. section 1983j(f), speaks only in terms of

"a person asserting rights under the provisions of [the Actl" and

does not explicitly mention actions against the state, as in

Fitzpatrick, the connection between the statutory section

authorizing a judicial remedy and the section establishing rights

against the state is enough to exhibit Congress’ intent to

abrogate eleventh amendment immunity. No clearer reference to

the state is found in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act,

Fitzpatrick, supra, 427 U.S. at 449 and n.S5, or in the Equal

Educational Opportunities Act, Gomez, supra, Lexis Op. at 9 (an

individual denied an equal educational opportunity ... may

institute a civil action in an appropriate district court of the

United States against such parties and for such relief, as may be

appropriate"), or in the Education of All Handicapped Children

Act, David D., supra, 775 F.2d at 422 ("The culmination of the

state administrative appeals process is the right of any party

‘aggrieved’ by the decision or procedure employed to take the

matter to either state of federal court", c¢iting 20 U.S.C.

section 1415(e)(2)).

Third, as in Fitzpatrick, legislative history makes it

clear that Congress intended the states to be the entitles

primarily responsible for enforcement of rights guaranteed by the

- Be.

Voting Rights Act and the fifteenth amendment. See the preceding

section of this brief. As distinguished from the statute

considered in Atascadero, the Voting Rights Act does not impose

obligations upon the states only if they accept federal funding,

and the responsiblities of the state are singled out from those

of other persons or entities who are able to affect blacks’

voting rights.

Fourth, the Voting Rights Act is probably the most

dramatic instance of the exercise of Congress’ enlarged powers,

vis-a-vis the states, under the enforcement sections of the Civil

War Amendments.

"It is the power of Congress which has been enlarged.

Congress is authorized to enforce the prohibitions [in

Section 1 of the fifteenth amendment] by appropriate

legislation. Some legislation is contemplated to make

the [Civil War] amendments fully effective."

Accordingly, in addition to the courts, Congress has

full remedial powers to effectuate the constitutional

prohibition against racial discrimination in voting.

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, supra, 383 U.S. at 326, quoting EX

Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 345.

Finally, as in Gomez, supra, a reading of the Voting

Rights Act which provides private citizens a judicial cause of

action under Section 2 of the Act but which denies them the right

to name the state as a defendant would render nugatory thelr

ability to obtain an injunction against unlawful voting practices

"applied by any State". As this Court has discovered in the

A

ea Oo eo o

instant action and in other cases like Harris v. Graddick, 593

F.Supp 128 (M.D.Ala. 1984), private suits challenging voting

practices with statewide implications face practical difficulties

and delays when the defendants are limited to state officers. In

Harris, the primary defense of the governor and attorney general

has been their disavowal of responsibility in their individual or

official capacities to fulfill the state's obligation to

eliminate statewide voting rights violations carried out under

state law. By enacting and amending the Voting Rights Act,

Congress intended to block the "buck-passing" tactics officers

and subdivisions of the state were employing to avoid voting

rights enforcement. It could not have intended to extend a right

of action to the victims of voting discrimination and at the same

time cripple their ability to obtain enforcement by forcing them

to sue individual state officers. The only fair reading of the

express terms and legislative scheme of the Voting Rights Act is

that Congress abrogated the states’ eleventh amendment immunity.

Procedural and Practical Matters

According to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

service on the State of Alabama should be perfected by service on

the governor and state attorney general. Under Alabama law, the

attorney general is responsible for defending the state and all

- an.

its agencies in civil actions. Ala. Code sections 16-8-1 and

36-15-21 (1975).

The state is bound by this Court's findings of

invidious legislative intent. Although this Court never formally

invited the Attorney General of Alabama to defend the original

claims, as a matter of fact the Attorney General was aware of the

lawsuit, was actually requested to participate by some of the

defendant counties, and chose not to intervene.

However, the state should be given the opportunity to

demonstrate that, as a matter of law or as a matter of fact, it

is not bound by principles of res judicata with respect to the

intent findings.

The state alone has the responsibility and resources to

respond to claims that the racially motivated at-large laws still

adversely affect blacks in each of the identified local

jurisdictions. It can carry out its responsibilities under the

Voting Rights Act in at least two ways: by conducting its own

assessment of where violations still exist and by coordinating

any defenses that the local jurisdictions themselves might choose

to assert. Because any significant adverse racial impact makes

the local election systems unlawful in light of this Court's

intent findings, and because Thornburg wv. Gingles, 106 S.Ct.

2752 (1986), has dramatically clarified and simplified the

criteria for determining whether at-large systems fall the

- 260 -

results test in particular jurisdictions, the state has clear

guidance for its assessment. The state may already have access

to much of the information needed to "audit" its at-large local

election systems. It can, where it thinks necessary, require

local jurisdictions to produce all the data--such as

precinct-level election returns, black-white registered voter

PE (or census figures where the registered voter breakdown

is not available), and the record of success of candidates

favored by black voters--which should be examined to determine

whether there is racially polarized voting that operates in the

at-large system to deny a substantial black minority the equal

opportunity to elect candidates of its choice.

The state, of course, can also present any claim

preclusion defenses on behalf of particular local jurisdictions,

such as res judicata.

As a practical matter, the state may determine that

many if not most jurisdictions should not or would not choose to

defend the liability claims in court. These jurisdictions .can

4

This Court previously ordered 64 counties to comply no

later than the 1986 primary elections with the requirement of

Ala. Code section 17-4-187 (Supp. 1986) to maintain a permanent

list of all qualified electors by precinct and by race. Harris

v. Graddick, 615 F.Supp. 239, 246 (M.D.Ala. 1985). The Court

presently has under submission the Harris plaintiffs’ remaining

claims that the state attorney general should supervise

enforcement of this requirement and others set out in the Harris

decree.

- 0.

become the subject of prompt remedy proceedings. With respect to

situations where the state and/or the local jurisdiction decides

to rebut the prima facie evidence of a Section 2 violation,

pretrial preparation and presentation of evidence can be

coordinated by the state, and cumulative or duplicative evidence

can be eliminated. Once on notice about which local

Jurisdictions will be the subjects of liability contests,

plaintiffs can be given a manageable opportunity to prepare

whatever evidence they think is needed to meet these defenses.

In the remedy phase, the state is the appropriate

entity to coordinate specific proposals. In the first place, by

legislation it can offer local jursidictions options for remedial

election systems that are not available under existing law. The

state attorney general can examine existing law governing

municipal and school board elections and propose modifications or

additions to the Legislature. See Ala. Code sections 36-15-1(1),

(8), (10) and (15). In this way, the Court will be adhering to

the rule of initial deference to proper state authority in.

formulating remedies.

It appears that current Alabama law provides the

following options for municipalities using at-large elections:

Cities over 12,000 not having a commission form of government

elect the members of the council under one of several options;

most require at-large elections. Only two options allow the use

of districts--a city having more than 7 wards shall elect one

councilor from each ward plus enough at-large to make 15 total

(one of whom is designated the president); and cities over 20,000

with 7 or fewer wards shall elect two from each ward, plus an

at-large county president. See generally Ala. Code, Title 11,

Chapters 43 and 44.

Unless local laws provide alternative systems, general

law in Alabama now provides only for partisan election of county

school boards by the at-large scheme challenged here. Ala. Code,

section 16-8-1 (1975).

The state can choose to provide remedial election

schemes other than the single-member districts which must be

employed in court-ordered plans. So long as they afford blacks

truly equal opportunities for effective political participation

and to elect candidates of their choice, state and local

governments are free to retain at-large voting under election

schemes that include provisions like limited voting, cumulative

voting and transferable preferential voting. United States v.

Marengo County Comm., 731 F.2d 1546, 1560 n.24 (llth Cir. 1984)

(citations omitted).

Considering all the remedial options available to the

state (but not to the local governments), the Court should

require the attorney general to prepare and present for

appropriate Section 5 preclearance and final approval by the

0

Court a statewide "de-dilution" plan.

III. CLASS ACTION ISSUES

The State of Alabama has ultimate legal authority over

all its local subdivisions and their election systems. Arguably,

the state is the only party defendant necessary to afford

plaintiffs complete relief.

However, to take account of potential practical and

political conflicts between state and local officials, plaintiffs

have asked that the Talladega County Board of Education and the

City of Childersburg be added as respresentative defendants.

But, in joining the Talladega County defendants,

plaintiffs emphasize their contention that the state has the

primary legal and financial responsibility for defending this

action. Accordingly, plaintiffs also seek to join the Attorney

General of Alabama as a named party so that he can serve as the

chief co-representative of the defendant class of nunicipalities

and school boards. In this way, the attorney general, who would

already be before the Court as counsel for the defendant State of

Alabama, can in his joint capacity ensure that the defendant

class (and subclasses, if necessary) is adequately represented.

It would be impractical to require the Talladega County

defendants--or, for that matter, any other city or school

board--to bear more than a nominal share of the burden of

RE 4 DAE

representing the defendant class. With this defendant lineup,

plaintiffs contend, the major responsibility for conducting the

litigation will remain where it belongs, with the State of

Alabama: at the same time, the presence of city and school board

class representatives will afford a procedural avenue for more

active participation--and a commensurately larger share of the

legal and financial responsiblity--by local jurisdictions who

contend that the state and the attorney general are not

adequately representing thelr interests.

IV. PROCEDURALLY, JOINDER OF THE ADDITIONAL DEFENDANTS

AND DEFENDANT CLASS IN THIS ACTION IS APPROPRIATE

Joinder in this action of the State of Alabama, the

Attorney General of Alabama, the Talladega County Board of

Education, the City of Childersburg and the class they represent

is appropriate for the same reasons relied on by the Court to

join the five county commissions:

Plaintiffs’ claims arise out the state's racially

motivated enactment of at-large systems and numbered place laws.

640 F.Supp. at 1369.

Plaintiffs’ claims against all the additional

defendants arise from a single transaction or series of

transactions. Id.

Plaintiffs’ claims raise common questions of law and

- 31 -

fact with respect to all defendants. Id.

The Supreme Court instructs federal courts to give the

joinder rules "the broadest possible scope of action consistent

with fairness to the parties." Id., quoting United Mine Workers

v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 724 (19686).

Joinder is especially fitting where avoidance of

multiple litigation will help carry out the Congressional policy

of speedy enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. Id.

CONCLUSION

The motion for additional relief is the approporiate

means of enforcing the voting rights of Alabama's black citizens,

in light of this Court's prior rulings.

Respectfully submitted this 23rd day of February, 198%.

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

405 Van Antwerp Building

P. O. Box 105)

Mobile, AL 36633

(205) 433-2000

U. BLACKSHER

Larry T. Menefee

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

Fifth Floor, Title Bullding

300 Twenty-First Street, North

Birmingham, AL 35203

(205) 322-7300

Terry Davis

- 32 -

SEAY & DAVIS

732 Carter Hill Road

P. O. Box 6215

Montgomery, AL 36106

(205) 834-2000

Julius L. Chambers

Pamela S. Karlan

Lani Guinier

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

¥. Edward Still

REEVES & STILL

714 South 20th Street

- Birmingham, AL 35233-2810

(205) 322-6631

Reo Kirkland, Jr.

307 Evergreen Avenue

P. O. Box 646

Brewton, AL 36427

(205) 867-5711

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this 23rd day of February,

1987, a copy of the foregoing PLAINTIFFS’ BRIEF SUPPORTING MOTION

FOR ADDITIONAL RELIEF was served upon following counsel:

D. L. Martin, Esq. David R. Boyd, Esq.

215 South Main Street BALCH & BINGHAM

Moulton, AL 35650 P. O. Box 78

(205) 974-9200 Montgomery, AL 36101

(Lawrence County) (205) 834-6500 (Lawrence County)

Jack Floyd, Esq. Barry D. Vaughn, Esq.

FLOYD, KEENER & CUSIMANO PROCTOR & VAUGHN

816 Chestnut Street 209 North Norton Avenue

-. Bai,

Gadsden, AL 35999-2701

(208) 547-6328

(Etowah County)

Yetta G. Samford, Esq.

SAMFORD, DENSON, HORSLEY,

MARTIN & BARRETT

P. O. Box 2345

Opelika, AL 36803-2345

(205) 745-3504

(Lee County)

Herbert D. Jones, Jr., Esq.

BURNHAM, KLINEFELTER, HALSEY,

¥ CATER

P. O. Box 1618

Anniston, AL 36202

(208) 237-8515

(Calhoun County)

John A. Nichols, Esq.

LIGHTFOOT, NICHOLS &® SMITH

P. 0. Box 369

Luverne, AL 36049

(205) 335-5628

(Crenshaw County)

Robert Black, Esq.

HILL, HILL, CARTER, FRANCO, COLE

& BLACK

P. O. Box 118

Montgomery, AL 36195

(205) 834-7600

(Crenshaw County)

Warren Rowe, Esq.

Rowe & Sawyer

P. 0. Box 150

Enterprise, AL 36331

(Coffee County)

Sylacauga, AL 35150

(205) 249-8527

(Talladega County)

Rick Harris, Esq.

MOORE, KENDRICK, GLASSROTH,

HARRIS, BUSH & WHITE

P.O. Box 910

Montgomery, AL 36102

(208) 264-9000

(Crenshaw County)

James W. Webb, Esq.

WEBB, CRUMPTON, MCGREGOR, SCHMAELINC

¥ WILSON

P. O. Box 238

Montgomery, AL 36101

(205) 834-3176

(Escambia County)

Lee M. Otts, Esq.

OTTS & MOORE

P. O. Box 46%

Brewton, AL 36427

(205) 867-7724

(Escambia County)

¥. O. RIRK, Jr., Esq.

P. O.Box A-B

Carrollton, AL 35447

(205) 367-8125

(Pickens County)

James G. Speake, Esq.

SPEAKE, SPEAKE & REICH

P. O.Box B

Moulton, AL 35650

(Lawrence County)

by depositing same in the United States, mail postage prepaid.

EY FOR PLAINTIFFS

BA