Goodwin v. Alameda County Notice of Motion and Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Motion for Peremptory Writ of Mandate

Public Court Documents

July 13, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goodwin v. Alameda County Notice of Motion and Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Motion for Peremptory Writ of Mandate, 1984. 5684b9b3-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aee14041-59bb-4223-9461-e4905039cccc/goodwin-v-alameda-county-notice-of-motion-and-memorandum-of-points-and-authorities-in-support-of-motion-for-peremptory-writ-of-mandate. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

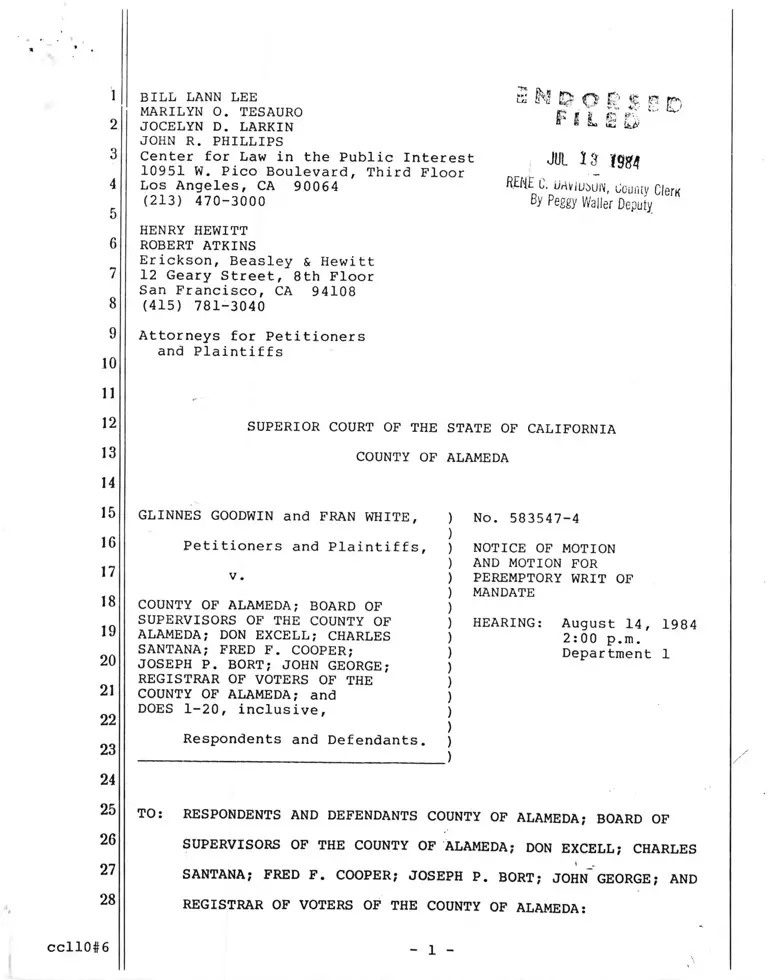

BILL LANN LEE

MARILYN 0. TESAURO

JOCELYN D. LARKIN

JOHN R. PHILLIPS

Center for Law in the Public Interest

10951 W. Pico Boulevard, Third Floor Los Angeles, CA 90064

(213) 470-3000

HENRY HEWITT

ROBERT ATKINS

Erickson, Beasley & Hewitt

12 Geary Street, 8th Floor

San Francisco, CA 94108

(415) 781-3040

£ N & o c-

~ I L ® ~ ~P

JUL is 1334

m E C uAviû u, county Clern

By Peggy Waller Deputy

Attorneys for Petitioners

and Plaintiffs

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

COUNTY OF ALAMEDA

GLINNES GOODWIN and FRAN WHITE, )

)Petitioners and Plaintiffs, )

)v- )

)COUNTY OF ALAMEDA; BOARD OF )

SUPERVISORS OF THE COUNTY OF )ALAMEDA; DON EXCELL; CHARLES )SANTANA; FRED F. COOPER; )

JOSEPH P. BORT; JOHN GEORGE; )

REGISTRAR OF VOTERS OF THE )

COUNTY OF ALAMEDA; and )

DOES 1-20, inclusive, )

)Respondents and Defendants. )

_____________________________)

No. 583547-4

NOTICE OF MOTION

AND MOTION FOR

PEREMPTORY WRIT OF MANDATE

HEARING: August 14, 1984

2:00 p.m.

Department 1

TO: RESPONDENTS AND DEFENDANTS COUNTY OF ALAMEDA; BOARD OF

SUPERVISORS OF THE COUNTY OF ALAMEDA; DON EXCELL; CHARLES

SANTANA; FRED F. COOPER; JOSEPH P. BORT; JOHN GEORGE; AND

REGISTRAR OF VOTERS OF THE COUNTY OF ALAMEDA:

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that on August 14, 1984, at 2:00

p.m., or as soon thereafter as the matter can be heard, at the

courtroom of Department 1 at the Alameda County Superior

Courthouse, 1225 Fallon Street, Oakland, California, petitioners

will move the Court for a peremptory writ of mandate commanding

respondents, as quickly and expeditiously as possible, to

undertake the following actions so as to accomplish compliance

with the mandatory duties imposed by the equal protection clause

of Article I, § 7 of the California Constitution:

1. To rescind Ordinance 83-077 ("the 1983

Redistricting") inasmuch as it adjusted the boundaries of

Supervisorial District 3;

2. To restore to District 3 the predominantly black

areas discriminatorily gerrymandered out of District 3;

3. To return to the boundaries of District 3 that

existed prior to the adoption of Ordinance 83-077, or, to assure

that any revised redistricting plan results in an equal

distribution of population among the districts without reducing

black voting strength in District 3.

The application is being filed at this time because

discovery has established respondents' clear failure to perform

their duty, required by Article I, § 7 of the California

Constitution, not to reduce the voting strength of black

residents of District 3.

The instant application is based on (a) the accompany

ing Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Motion

for Peremptory Writ of Mandate; (b) the verified Petition for

Writ of Mandate and Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Relief and respondents' Return and Answer filed herein; (c) the

lodged depositions, including attached exhibits, of District 1

Supervisor Don Excell (taken April 27 and 30, 1984); District 2

Supervisor Charles Santana (taken June 12, 1984); District 3

Supervisor Fred Cooper (taken April 24, 1984); District 4

Supervisor Joseph Bort (taken April 19, 1984); Alameda County

Planning Director William Fraley (taken April 17 and 18 and

May 2, 1984); and Charles Brown (taken June 4, 1984); (d) the

accompanying Declarations of Robert Atkins; Leo Bazile;

District 5 Supervisor John George; Jocelyn Larkin; Wilson Riles,

Jr.; Sandre Swanson; and Mary Watson; (e) the accompanying

Declaration of Christina Concepcion with the attached transcript

of the Board of Supervisors' meetings of October 4th and 11th;

and (f) such further evidence and argument as may be produced at

the hearing upon this application.

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

3

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

For the convenience of the Court and the parties,

petitioners' verified Petition for Writ of Mandate and

respondents' Return and Answer, the excerpts of the lodged

depositions and the exhibits to depositions cited by the

petitioners in the Memorandum of Points and Authorities have

been filed in an accompanying compilation, entitled "Record

Excerpts."

Dated: July 12, 1984

Respectfully submitted,

BILL LANN LEE

MARILYN O. TESAURO

JOCELYN D. LARKIN

JOHN R. PHILLIPS

Center in for Law in the

HENRY HEWITT ROBERT ATKINS

Erickson, Beasley & Hewitt

ROBERT ATKINS

Attorneys for Petitioners

and Plaintiffs

By

4

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

CERTIFICATE OF PERSONAL SERVICE

I, ROBERT ATKINS, declare and say:

That I am an attorney for petitioners and plaintiffs

in the above-entitled action.

That on July 13, 1984, I personally served the

attached NOTICE OF MOTION AND MOTION FOR PEREMPTORY WRIT OF

MANDATE upon counsel for respondents herein, by delivering a

true copy thereof to:

RICHARD J. MOORE

County Counsel

DOUGLAS HICKLING

KELVIN H. BOOTY, JR.

Assistants County Counsel

County of Alameda

1221 Oak Street, Suite 463

Oakland, California 94612

Executed this 13th day of July, 1984, at San

Francisco, California.

I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing

is true and correct.

ROBERT ATKINS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

f 5

BILL LANN LEE

MARILYN O. TESAURO

JOCELYN D. LARKIN JOHN R. PHILLIPS

Center for Law in the Public Interest 10951 W. Pico Boulevard, Third Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90064

(213) 470-3000

HENRY HEWITT

ROBERT ATKINS

Erickson, Beasley & Hewitt

12 Geary Street, 8th Floor

San Francisco, CA 94108

(415) 781-3040

Attorneys for Petitioners

and Plaintiffs ..

2 H & 0 8 S E D

F I L E B>

jut is m

RENE C. DavIDSON, County ClerK

By Peggy Waller Deputy

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

COUNTY OF ALAMEDA

GLINNES GOODWIN and FRAN WHITE,

Petitioners and Plaintiffs,

v.

COUNTY OF ALAMEDA; BOARD OF

SUPERVISORS OF THE COUNTY OF

ALAMEDA; DON EXCELL; CHARLES

SANTANA; FRED F. COOPER;

JOSEPH P. BORT; JOHN GEORGE;

REGISTRAR OF VOTERS OF THE COUNTY OF ALAMEDA; and

DOES 1-20, inclusive,

Respondents and Defendants.

/

/

) No. 583547-4

)) MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND

) AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT OF

) MOTION FOR PEREMPTORY ) WRIT OF MANDATE

)) HEARING:

) August 14, 1984

) 2:0 0 p.m.) Department 1

)

)

)

)

)

)

/

/

/

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Page

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities ..................................

I. INTRODUCTION......................................

II. JURISDICTION................................ .

III. STATEMENT OF THE CASE.............................

A. PROCEEDINGS TO DATE..........................

B. STATEMENT OF FACTS...........................

1. Background..............................

2. The 1981 Redistricting..................

3. Recent Electoral History of District 3. .

4. Preparations for 1983 Redistricting,

June through August, 1983...............

5. The 1983 Redistricting, September

through October, 1983...................

6. Impact of 1983 Redistricting............

7. Subsequent History of the

1983 Redistricting......................

IV. SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT...............................

V. ARGUMENT..........................................

A. AN ELECTORAL SYSTEM OR PRACTICE THAT

SIGNIFICANTLY IMPAIRS THE RIGHT TO VOTE

OF A RACIAL MINORITY IS SUBJECT TO "ACTIVE

AND CRITICAL" JUDICIAL SCRUTINY..............

B. A REDISTRICTING PLAN THAT REDUCES MINORITY

VOTING STRENGTH IS PROHIBITED BY THE GUARANTEE OF EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAWS..............

C. THE 1983 REDISTRICTING VIOLATES THE EQUAL

PROTECTION CLAUSE OF THE CALIFORNIA CONSTI

TUTION BECAUSE IT HAS THE VOTING EFFECT OF

REDUCING BLACK VOTING STRENGTH........... .. .

1. A Violation of Equal Protection of the

Laws is Established' by a Showing that the

1983 Redistricting Plan Has the Effect of Reducing Black Voting Strength. .

ii i

2

4

5

5

7

7

9

11

13

16

25

28

30

32

32

33

36

36

i

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Page

2. The 1983 Redistricting Plan Has the Effect

of Reducing Black Voting Strength in

Violation of the California Constitution. . 40

D. THE 1983 REDISTRICTING PLAN WAS INTENDED TO

DILUTE BLACK VOTING STRENGTH IN VIOLATION- OF

THE CALIFORNIA CONSTITUTION.................... 4 3

1. The Arlington Heights Standard............ 43

2. Application of the Arlington Heights

Standard.................................. 44

a. Substantive Irregularities............ 44(i) The decision to redistrict

in 1983......................... 45

(ii) The manipulation of population. . 47

(iii) The "uncouth configuration"

of new District 3............... 51

b. Procedural Irregularities............. 52

c. Historical Background and the

Specific Sequence of Events........... 55

d. Legislative History................... 59

D. RESPONDENTS' EXPLANATIONS FOR THE 1983

REDISTRICTING DO NOT JUSTIFY DENIAL OF

THE CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS OF BLACK

RESIDENTS OF DISTRICT 3........................ 63

1. Respondents Bear the Heavy Burden of

Demonstrating That the 1983 Redistricting

Is Necessary to Achieve a Compelling

State Interest............................ 63

2. None of Respondents' Rationalizations

Constitutes Either a Compelling State

Interest or Is Necessary to Achieve a

Compelling State Interest.............. 65

a. Respondents' Explanation of the

1983 Redistricting................. 65

b. The Interest in Equalizing Population . 66c. The Interest in Dispersing

Unincorporated Residents........... 66

d. The Interest in Preserving the

Historical Numbering of the Districts . 71

e. The Interest in Maintaining

Communities of Interest........... 72

f. The Interest in Enhancing Black

Voting Strength................... 76

g. The Support of Black Politicians. . . . 79h. Whether the Redistricting Would

Have Occurred in the Absence of^

a Discriminatory Purpose........... 81

VI. CONCLUSION....................................... 84

- ii -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

5

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Abate v. Mundt, 403 U.S. 182 (1971) .............■ 47

American Federation of State Employees

Local 685 v. County of Los Angeles,

146 Cal.App. 3d 879 (1983) ...................... 37

Anderson v. Celebreeze, __ U.S. __,

103 S.Ct. 1564 (1983) ......................... 43

Assembly v. Deukmejian, 30 Cal.3d 638 (1982) ........ 39

Blair v. Pitchess, 5 Cal.3d 258 (1971) .............. 5

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .... 33

Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73, (1966) ............ 38

Buskey v. Oliver, 565 F.Supp. 1473 (M.D. Ala. 1983) .. 35,80

Calderon v. City of Los Angeles, 4 Cal.3d 251 4,34,36,41

(1971) ....................................... 45,66,78,79

Castenada v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) ......... 81

Castorena v. City of Los Angeles, 34 Cal.App.3d 901

(1973) ....................................... 35,37

Castro v. State of California, 2 Cal.3d 223

(1970) ....................................... 32,63,64,66

Choudhry v. Free, 17 Cal.3d 660 (1976) 32

Citizens Against Forced Annexation v. Local Agency

Formation Commission, 32 Cal.3d 816 (1982) ...... 70

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) ....... 38

Committee to Defend Reproductive Rights v. Myers.

29 Cal.3d 252 (1981), appeal dismissed.456 U.S. 941 (1982) .......................

Crawford v. Board of Education, 17 Cal.3d 280

(1976) ........................................ 37

Curtis v. Board of Supervisors, 7 Cal.3d 942

(1972) ................ 32,34

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ....... 51

Gould v. Grubb, 14 Cal.3d 661 (1975) .............. 4,32,34,37

41,70,83

- iii -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Howard v. Adams County, 453 F.2d 455 (5th Cir.)

cer t. denied, 407 U.S. 925 (1972) ............. 38

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District,

59 Cal.2d 876 (1963) ........................ 33,36,37

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors, 554 F.2d 139

(5th Cir.) (en banc), cert, denied,

434 U.S. 968 (1977) ........................... 35,38,69

Larry P. v. Riles, 84 D.A.R. 398 (1984) ............ 37

Legislature v. Reinecke, 6 Cal.3d 595 (1972)........ 4,83

Mahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. 315 (1973) ............... 47

McWilliams v. Escambia County School Board,

658 F. 2d 326 (5th Cir. 1981) .................. 81

Moore v. Leflore County Board of Election

Commissioners, 502 F.2d 621 (5th Cir. 1974) ___ 59

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) .............. 32,33

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, __, (1982) .......... 43

Robinson v. Commissioners Court, 505 F.2d 674 35,38

(5th Cir. 1974) 49,50,59

Rybicki v. State Board of Elections, 574 F.Supp.

1082 (N.D.I11. 1982) 35,49,64,82

Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal.3d 584 (1971) ............. 32,37,39

Serrano v. Priest, 18 Cal.3d 728 (1976),

cert, denied, 432 U.S. 907 (1977) ............. 39

Tinsley v. Palo Alto Unified School District,

91 Cal. App. 3d 871 (1979) ...................... 39

United States v. Carolene Products Co.,

304 U.S. 144 (1938) 33

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan 43,44,59

Housing Development, 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ...... 62,64,81

Wenke v. Hitchcock, 6 Cal.3d 746 (1972) ............ 4

Westbrook v. Mihalv. 2 Cal.3d 765 (1970), 32,33,34

cert, denied, 403 U.S. 922 (1971) ............. 63,64,66

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) ............ 38

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ............ 32

IV

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Statutes

Article 1, § 7 of the California Constitution

Code of Civil Proc. § 1085 .................

Elections Code § 35000 ej: seq...............

Alameda County Charter, Section 7 ..........

Article

Karst, The Costs of Motive-Centered Inquiry,

15 San Diego L. Rev. 1163 (1978) ......

pass iro

5

passim

52,68

83

v

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

I. INTRODUCTION.

This action challenges the legality of Ordinance

No. 83-077, adopted by the Alameda County Board of Supervisors

on October 11, 1983. The ordinance altered the boundaries of

the five supervisorial districts of Alameda County, ostensibly

to achieve population equality among those districts as

permitted by Elections Code § 35003. Petitioners and

plaintiffs, Glinnes Goodwin and Fran White, who are black

residents, registered voters, and taxpayers in the City of

Oakland, assert that Ordinance 83-077 ("the 1983 Redistricting

Plan") fractures portions of the black population in District 3

between Districts 3 and 4, and thereby reduces the strength of

their vote. This discriminatory vote dilution deprives them of

their right to an equal and undiluted vote as guaranteed by the

equal protection clause of the California Constitution.

As further explained in Section III, infra, the 1983

Redistricting Plan radically altered the boundaries of

District 3, where many black voters reside, by eliminating

predominantly black Oakland neighborhoods and adding in virtu

ally all-white areas from other districts. As a result of

redistricting, the black population of District 3 dropped from

93,363 to 71,587 and the white population rose from 85,663 to

118,865, a net loss of about 22,000 blacks and a net gain of

about 33,000 whites. The consequence of this plan was to reduce

the black population of District 3 from a plurality of 42% to

31%, and increase the white population from 38% to a new

majority of 52%. The bottom line is that over a fifth of the

black population was lost and the white population increased by

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

almost 40%. The elaborate exchange of voters between District 3

and adjacent districts was wholly unnecessary to any legitimate

goal of equalizing population among districts, since this

purpose could have been accomplished by relatively'simple

adjustments of district lines involving small net population

changes. Moreover, the exceedingly suspect circumstances of its

adoption indicate that the redistricting was the product of

deliberate and purposeful racial discrimination.

Under the California Constitution, a plaintiff can

establish a violation of the guarantees of equal protection by

proving that a law has a discriminatory impact on a racial

minority. As fully briefed in Section V, infra, the fracturing

of District 3's black voters between two districts has the

effect of diluting the strength of their votes in violation of

the constitutional requirement of equal protection. In

addition, petitioners also demonstrate that the 1983

Redistricting Plan further denies equal protection of the laws

because it was intended to reduce the voting strength of blacks

within District 3. Moreover, respondents' purported

justifications for the Plan are without legal merit and

inadequate in light of the severe impairment that the Plan works

upon petitioners' fundamental constitutional rights.

Petitioners seek to correct the invidious reduction of

their previously established voting strength within District 3,

and, therefore, respectfully request that this court issue a

peremptory writ of mandate directing the Board to rescind the

discriminatory redistricting scheme and either return to the

pre-existing district boundaries or adopt a constitutionally

3

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

valid plan that does not fracture black areas or otherwise

reduce black voting strength.

II. JURISDICTION.

The California courts have traditionally reviewed

voting and election cases on a petition for writ of mandate

because such challenges generally present issues of substantial

and immediate public importance and seek relief in the form of

an order directing a legislative or administrative body to

comply with the requirements of law. See, e.g., Gould v. Grubb,

14 Cal.3d 661 (1975); Wenke v. Hitchcock, 6 Cal.3d 746, 751

(1972); Legislature v. Reinecke 6 Cal.3d 595 (1972); Calderon v.

City of Los Angeles, 4 Cal.3d 251 (1971). Mandamus is likewise

the appropriate remedy in this action because petitioners seek

to compel respondent Board to comply with its mandatory legal

duty to adopt a redistricting plan in conformance with the

requirements of the California Constitution.—^ The remedy that

they seek is a recission of the illegal redistricting of

District 3, and either a return to the pre-existing boundaries

or the adoption of a valid plan for District 3 and adjoining

districts that ensures the right of all voters to an equal and

undiluted vote. Monetary damages would not provide an adequate

substitute for the valuable right forfeited or restore legal

— While the initial decision whether to redistrict

pursuant to Elections Code § 35003. is within the Board's

discretion, once that decision is made, the Board is under a

mandatory legal duty to adopt a plan that conforms^to the

requirements of the state constitution. Thus, a writ of mandate

can properly be issued in this action.

4

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

supervisorial boundaries to within the County. Petitioners thus

have no adequate legal remedy to correct respondents' action,

and therefore proceed by means of an action for mandamus.

Petitioners have a beneficial interest in respondents'

actions with respect to redistricting because the ordinance

directly and materially impairs the worth of their vote in

future supervisorial elections. Petitioners' standing to sue is

based on that injury as well as on the broader injury they

suffer as taxpayers. The adoption by the Board of a

redistricting plan in violation of state law results in the

illegal and wasteful expenditure of public funds for which any

county taxpayer may seek redress. Blair v. Pitchess, 5 Cal.3d

258, 267 (1971).

Before filing suit, petitioners, by their attorneys,

made a demand upon the Board to rescind the 1983 Redistricting

Plan and to adopt a constitutionally valid plan. Petition

for Writ of Mandate and Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive

Relief (hereinafter "Petition") at 1[ 23. The Board has refused

to adopt a new plan, _id, and continues to ignore its clear and

present legal duty. Pursuant to its authority under Code of

Civil Proc. § 1085, this Court is empowered to direct respondent

Board to promulgate a redistricting plan that complies with the

California Constitution.

III. STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

A. PROCEEDINGS TO DATE.

This action was commenced on March 30, 1984 with the

filing of a petition for writ of mandate and complaint for

5

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

5

declaratory and injunctive relief by two black residents,

taxpayers, and registered voters of the third supervisorial

district of Alameda County. The Petition challenged the

redistricting plan adopted October 11, 1983 and sought relief

against the entities and officials responsible for County

elections, i.e., the County; the Board of Supervisors; the

individual Board members; the Registrar of Voters; and 20

fictitiously named DOES.

The County's Return and Answer (hereinafter "Return")

was filed by all the respondents and defendants other than John

George on May 4, 1984. The Return (a) admits certain factual

allegations, including those concerning the racial impact of the

redistricting on District 3, while denying others, and denying

liability; and (b) states various reasons why the redistricting

of District 3 was salutory and dictated by reapportionment

decisions involving other supervisorial districts. The County

also raises an affirmative defense of laches against judicial

relief for the June election, which is now moot.

Prior to the filing of respondents' Return,

petitioners commenced expedited discovery through depositions

and requests for production of documents.The County has

served interrogatories and requests to admit that were answered

on June 20th.

- The depositions of Supervisors Excell, Santana,

Cooper, and Bort, County Planning Director William Fraley, and

Supervisor Cooper's legislative assistant, Charles Brown, have been taken. The transcripts of these depositions have been

lodged with the Court. Excerpts of those portions of the

depositions cited in this Memorandum are appended herewith.

6

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

B. STATEMENT OF FACTS.

The material facts on which petitioners rely in

support of this motion are established in the verified petition,

admissions contained in the County's Return, deposition state

ments of defendants and respondents and their employees or

agents, documents supplied by respondents through the discovery

process, and the public hearing transcript and declarations,

appended herewith. No material facts are in dispute. Rather,

this is a case that requires the Court to apply the equal pro

tection clause of Article 1, § 7 of the California Constitution

and authoritative case law to an uncontroverted record.

1. Background.

The Board of Supervisors is the legislative body of

the County of Alameda. The Board consists of members elected

from five geographic districts for staggered terms of four

years. Petition at 1[ 11.

Prior to the 1983 redistricting, the total population

of the County was approximately 1,145,117. Exhibit 16 of Fraley

Deposition (hereinafter "Fraley Exh. 16"). District 1,

represented by Don Excell, consisted of Pleasanton, Livermore,

almost all of Fremont, Dublin, and an unincorporated population

of 7,622. ^d. See Map 1, attached herewith. District 2,

represented by Charles Santana, was composed of Newark, Union

City, a small part of Fremont (4,840), Hayward, and a large

unincorporated population of 59,599. Id. District 3,

represented by Fred Cooper, consisted of all of the City of

Alameda and a large portion of the City of Oakland. Id.

7

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

District 4, represented by Joseph Bort, was composed of San

Leandro, Piedmont, a portion of Oakland, and a 47,169

unincorporated population. Id. District 5, represented by John

George, consisted of north Oakland, Berkeley, Albany, and

Emeryville. Id.

Oakland residents within District 3 comprised

approximately 154,000 persons, 70% of District 3's total

population. Id. Alameda residents, approximately 66,385

persons, represented the other 30% of the District's total. Id-

The City of Oakland was divided between three districts: 44% of

its residents lived within the boundaries of District 3, 29% in

District 4, and 27% in District 5. Id-

Prior to the 1983 redistricting, District 3

encompassed parts of the City of Oakland that include

predominantly black neighborhoods. Petition at K 13.

District 3, in fact, had the largest black population of the

five supervisorial districts, both as an absolute number (93,363

persons) and as a proportion of district population (42.3%).—^

Id. Ninety-seven percent of District 3's black population lived

in Oakland, and 3% in Alameda. See Watson Declaration at U 7;

Fraley Exh. 4; Fraley Exh. 16. In contrast, 60% of District 3's

white population lived in Alameda, and 40% in Oakland. Id.

- Petitioners calculate the racial breakdown in

District 3 prior to the 1983 redistricting based upon the

Alameda County Planning Department's total District 3 population

figure as of August 22, 1983, Fraley Exh. 16, and the racial

percentages for each district contained in the Planning Depart

ment's letter to Supervisor Cooper, March 11, 1983* Fraley

Exh. 4. The 1980 U.S. Census racial percentages are the only

available breakdown of population by race. Fraley Exh. 33.

8

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

10

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

20

Since 1970, District 3 has been represented by

Supervisor Cooper. Cooper deposition (hereinafter "Depo."),

pp. 2-3. Supervisor Cooper, who is white, resides in Alameda

and maintains his law office in Alameda. Id.

2. The 1981 Redistricting.

The last reapportionment of supervisorial districts in

Alameda County prior to the 1983 redistricting occurred on

August 25, 1981. Fraley Exh. 10 (Ordinance 81-64); Bort Depo.,

p. 4; Cooper Depo., p. 3. Immediately before that 1981

redistricting, the County Planning Department estimated the

County's population at 1,112,362, so that an ideal population

for each supervisorial district was 222,472. Fraley Exh. 2

(letter dated July 29, 1981 to Board members from Planning

Director Fraley). The percentage difference in population

between the smallest and the largest district was 11.3%.—/

On August 25, 1981, Supervisor Bort moved that the

same districts be maintained except for certain minor technical

changes because the population was not sufficiently out of

- The Board was required to use then-current State

Department of Finance statistics to redistrict, rather than 1980

U.S. Census statistics. See Fraley Exh. 2; Fraley Exh. 13

(letter dated April 16, 1981 of County Counsel to Supervisor Bort) .

The percentage difference in population between the

smallest and largest districts, is calculated by ascertaining

the amount by which the smallest and largest districts are

respectively under and over the ideal population, adding

together these two figures and dividing the resulting sum by the ideal population.

9

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

balance. Public Hearing Trans, at 5;-^ Fraley Exh. 10; Bort

Depo., pp. 28-29. The motion passed 4-1. Fraley Exh. 10.—^

The 1981 redistricting, in fact, did not result in any

significant population equalization. See Fraley Exh. 7 (letter

of June 11, 1982 to Supervisor Cooper from Planning Director

Fraley stating that then current population of the supervisorial

- Petitioners have appended transcriptions of the public

hearing held by the Board on October 4, 1983, and a portion of

the Board meeting held on October 11, 1983 as Attachment A. See Declaration of Christina Concepcion.

6 /— On April 16, 1981, the County Counsel specifically

advised the Board of the mandatory requirement of Elections Code § 35000 that redistricting for the purpose of population

equalization must be completed by November 1, 1981. Fraley

Exh. 13. The County Counsel stated that Elections Code § 35000

"requires that the population of the districts be as equal as

possible," but noted that recent United States Supreme Court

decisions indicated that "some deviation from the equal

population requirement can be tolerated if found to be justified

by legitimate considerations incident to the effectuation of a rational policy." The letter continues:

[i J t is impossible to state what amount of deviation

would be found permissible. The Supreme Court has

upheld percentages of 7.8, 9.9, 11.9, and 16.4, but as

the court itself put it, "Neither courts nor Legisla

tures are furnished any specialized calipers that

enable them to extract from the general language of

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment the mathematical formula that establishes what

range of percentage deviations is permissible, and what is not."

Fraley Exh. 13. A month later, County Counsel provided an

extensive analysis of the relevant authorities at the request of

Supervisor Cooper. Cooper Exh. 4 (attached May 14, 1981 letter

memorandum to Supervisor Cooper from County Counsel Moore).

The respondents assert that "the 1981 redistricting

was not a reapportionment designed to equalize the population of

the supervisorial districts, but was comprised rather of minor

changes to district boundaries designed to bring them into

conformity with election precincts for the convenience of the Registrar of Voters." Return at 1| 2.

10

i:

1‘

l-

H

IE

1C

17

18

IS

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

districts is set forth in July 29, 1981 letter, produced prior

to 1981 redistricting); Public Hearing Trans, at 5

3. Recent Electoral History of District 3.

In 1978, Leo Bazile, a black Oakland resident,

challenged Supervisor Cooper for his seat in District 3. Cooper

retained his seat, winning 58.1% of the vote (25,451) to

Bazile's 41.9% (18,341). Cooper's margin of victory was 7,110

votes. See Exhibit A to Atkins Declaration.

In the 1982 District 3 election, Sandre Swanson, a

black candidate from Oakland, and C.J. "Chuck" Corica, a white

candidate, opposed Cooper. Petition at K 13. Swanson received

37.6% (14,361) of the votes cast, Cooper received 31.5%

(12,018), and Corica received 30.9% (11,776). Id. Because the

County requires a majority vote for election, a run-off was held

between Swanson and Cooper in November 1982. Id. In that

7/ In 1981, District 3 Supervisor Cooper voted aqainst the redistricting because he favored more extensive

redistricting but was unable to convince other board members Fraley Exh. 10; Cooper Depo., p. 83; Excell Depo., Vol. 1, np

9-10. County Planning Department records show that Supervisor

Cooper specifically requested racial data for the 1950, I960 and

1970 census during the consideration of the 1981 redistrictinq

S£e Fraley Exh. 11 (letter dated March 19, 1981 to Supervisor Cooper from Planning Director Fraley.)

These data show that the black population of the County has always been concentrated in Oakland, that the

population of Oakland declined from 384,575 in 1950 to 361 561

iD that the black population of Oakland increased47,562 in 1950 to 83,618 in 1960 to 124,710 in 1970 Id (The

?d Y Wi£h significant black population v^s Birkeley.)Id. On the other hand, the population of Alameda, which consti-

Part °f District 3' remained stable between 1950 (64,430) and 1970 (70,968), and over 90% white. Id.

11

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

district run-off election, Cooper received 52.6% (28,634) and

Swanson received 47.4% (25,770) of the votes cast. Cooper's

margin of victory was only 2,864 votes.

An analysis of the 1982 District 3 election returns

shows that 93 of 97 Oakland precincts were won by Swanson in the

June election, and that 88 of 97 Oakland precincts were won by

Swanson in the November 1982 run-off. See Watson Declaration at

1MI 3, 4. Cooper, on the other hand, carried all 47 Alameda

precincts in November. Id. Eighty-eight of the 93 total

precincts carried by Swanson in the June election were majority

black or majority non-white. Id. Eighty-four of the 88 total

precincts carried by Swanson in the November election were

majority black or majority non-white. JU3. Forty-nine of the

total 56 precincts carried by Cooper in November 1982 election

were predominantly white. Id.

In February or March 1983, several months after the

November 1982 run-off and prior to any official consideration of

redistricting by the Board, Supervisor Cooper requested that the

Planning Department provide him with a breakdown of population

in each supervisorial district by race and Spanish origin.

Petition at 1| 14; Return at 1[ 3. The Planning Department

provided these estimates to Cooper on or about March 11, 1983

with copies to the other members of the Board. ][d. The

Planning Department's estimates, based on 1980 census data,

revealed the following racial population data:

/

/

/

12

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Dist. Total White Black

Am. Indian

Eskimo &

Aleut.

Asian &

Pacific Islander Other

1 231,786 203,487

(87.8%)

4,960

(2.1%) 1,606

(0.7%) 11,277

(4.9%) 10,456(4.5%)

2 227,981 168,764

(74.0%)

12,245

(5.4%) 2,053

(0.9%) 21,127

(9.3%) 23,792

(10.4%)

3 214,622 83,309

(38.8%)

90,789

(42.3%) 1,729

(0.8%)

20,824

(9.7%) 17,971

(8.4%)

4 218,917 171,099

(78.1%)

24,499

(11.2%)

1,074

(0.5%) 14,820

(6.8%) 7,425(3.4%)

5 212,073 113,952

(53.7%)

71,120

(33.5%)

984

(0.5%)

17,851

(8.4%)

8,166

(3.9%)

TOTAL: 1,105,379 740,612

(67.0%)

203,612

(18.4%) 7,446

(0.7%) 85,899

(7.8%) 67,810

(6.1%)

Fraley Exh. 4 (Spanish origin <omitted)^

4. Preparations for 1983 Redistrictinq, June through

August, 1983.

On June 28, 1983, the Board considered the subject of

supervisorial redistricting as an off-agenda item, and requested

a report on district population from the Planning Director.

Return at K 18; Fraley Exh. 8. Planning Director Fraley

responded on July 15th with tables of the 1980 and 1983

supervisorial district populations and deviations from ideal

population. Return at 1[ 19. The 1983 table showed that the

total county population had increased to 1,145,117; the ideal

population for each district was now 229,023. Fraley Exh. 14.

— The Planning Director could recall only that

Supervisor Cooper requested racial data from the Planning

Department. He could not recall any other supervisors seeking such information. Fraley Depo., pp. 40-41.

- 13 -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

= 5

Since 1981, the percentage deviation between the largest and

smallest districts, had increased 0.3% from 11.3% in 1981, see

supra at p. 9, to 11.6% in 1983.—^ Supervisors Bort and George

did not believe that the population deviation was sufficient to

justify redistricting. Bort Depo., pp. 43-45; Public Hearing

Trans, at 6; George Decl., K 3a. The other Board members wanted

to proceed with redistricting.

On July 1st, the Clerk of the Board asked the Planning

Director to assist in scheduling a public hearing in three or

four weeks. Fraley Exh. 8. Two weeks later, the Planning

Director recommended that "such a hearing date be set at the

pleasure of the Board members." Fraley Exh. 14. No hearing was

set until final Board proposals were developed two months later.

On August 2nd, the Board named District 1 Supervisor

Excell as liaison between the Board and the Planning Director on

supervisorial redistricting. Fraley Exh. 15.— ^ As liaison,

Supervisor Excell was to give the Planning Director the Board's

proposals for redistricting so that the Planning Department

could prepare maps and determine the population impact of

- The Planning Department's July 15th report to the

Board included 1980 U.S. Census statistics, which show a per

centage deviation between the largest and smallest districts of

8.9%. When these figures are compared with the 1981 figures

contained in Fraley Exh. 14, it demonstrates that most of the

2.7% increase in deviation between 1980 and 1983 occurred prior

to the 1981 redistricting. The Planning Department did not

provide the Board with the January 1981 State Department of

Finance statistics upon which the 1981 redistricting, in fact, was based.

^7^ Supervisor Cooper made the motion. Fraley Exh. 15.

Supervisors Cooper, Santana and Excell voted in favor of the

appointment; Supervisor George was excused, and Supervisor Bort abstained. Id.

14

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

proposals. Excell Depo., Vol. 1, pp. 3-5. Each of the super

visors was to make decisions about the redistricting of his own

district, Bort Depo., pp. 20-21, Excell Depo., Vol. I, p. 37,

Vol. II, p. 37, and to obtain the consent or acquiescence of

supervisors of adjoining districts. The Planning Director

played no role in preparing proposals, did not comment on alter

natives, and made no judgments as to the propriety or legality

of the Board's proposals. Fraley Depo., pp. 57-58, 84. No

outside advisory or study commission or group played any role in

the deliberations that went into preparation of the Board's

proposals.

Supervisor Excell determined the redistricting to be

done in District 1, i.e., areas to be transferred to other

areas, and ascertained from each of the other supervisors,

except Supervisor George,— ^ what he wanted as to redistricting

of his own district. Excell Depo., Vol. I, pp. 4-5, Vol. II,

pp. 37-39. Supervisor Excell recalled that Supervisor Cooper

and he were the most interested in reapportionment. Id.,

Vol. II, p. 34. Planning Director Fraley recalls that Brown,

Cooper's legislative aide, was the only legislative aide to

contact him regarding the 1983 redistricting. Fraley Depo.,

pp. 65-71. Brown gave Excell a map or maps about the proposed

redistricting of District 3, and the proposed resulting modifi

cations of Districts 2 and 4. Excell Depo., Vol. II, pp. 42-44.

11/— District 5 Supervisor George, the only black

supervisor, opposed redistricting and did not discuss any

redistricting proposals concerning District 5 with^any other supervisor. George Decl. at 11 3.

15

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

5

5. The 1983 Red istricting, September through

October, 1983.

No redistricting proposal was released until September

1983. Fraley Exh. 20. On September 19, 1983, Supervisor Excell

transmitted to Planning Director Fraley a proposed redistricting

map with tentative district boundary lines shown in green

("green-line map"). Brown Exh. 9. This green-line map had been

prepared by Supervisor Cooper's aide, Charles Brown. Brown

Depo., pp. 72-75, 90. The next day, Brown sent to Excell a

memorandum with population estimates for each of the proposed

green-line districts. Excell Exh.l.— '' The memorandum, which

stated that the ideal or "optimum district size" was 229,000,

showed that the green-line map proposed districts with the

following population breakdown:

District Population

Id.

1 235,535

2 230,541

3 229,804

4 232,120

5 217,000

The green-line map shows that, starting with an

original District 3 population of 221,000, a total of 41,784

12/— A similarly worded memorandum with identical numbers

and a total county population figure was prepared the same day

under Planning Director Fraley's name and transmitted to Excell.

See Fraley Exh. 20. The Fraley version of the green-line

numbers was distributed to the Board on September 23rd. Excell Exh. 6.

16

1

1

1

1

1

1!

ll

r

1!

1!

21

2

2‘

2;

2‘

2[

2(

2\

2i

persons

persons

persons

to Distr

Leandro

District

would be removed from Di

in the East Oakland Banc

in the East Oakland Lake

ict 4.— ^ At the same t

census tracts— ^ would

4, and 27,314 persons

strict 3, including 7,

roft census tracts and

Merritt census tracts

ime, 23,274 persons in

be added to District 3

from two unincorporated

119

34,665

and added

the San

from

areas,

— ^ EAST OAKLAND TRACTS TO BE TRANSFERRED TO DISTRICT

Census Tract Total White Black Other

Lake Merritt

034 3351 1888 800 663052 4657 2270 783 1604053 4906 2576 968 1362054 6210 1356 3163 1691055 3433 876 1585 972056 3228 861 1393 974057 3149 710 1903 536058 3529 503 2329 697064 2202 956 892 354Total 34,665 11,996 13,816 8853

Bancroft

097 4470 393 3835 242102 2649 571 1902 1767119 964 5737 418

Fraley Exh. 20 , Exh. 21 I-J.

±4/ SAN LEANDRO TRACTS TO BE TRANSFERRED TO DISTRICT 3

Census Tract Total White Black Other

324 4619 3802 102 715333 6571 5657 37 877334 2948 2365 65 518335 4142 3745 11 386336 4994 4390 63 541Total 23,274 19,959 278 3037

Fraley Exh. 20, Exh. 21 I-J.

17

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

\5

Ashland and Cher r y l a n d ^ would be added to District 3 from

District 2. The net result of these proposed changes would be a

District 3 population estimated at 229,804. Fraley Exhs. 20,

21 I-J. The green-line map also shifted two census tracts along

the southern boundary of District 4 back into District 2,

despite the need to relieve District 2 of surplus population.— ̂

The tentative map contemplated no change in District 5, the most

underpopulated district. Id.

On September 20th, Supervisor Excell submitted to the

Board the green-line map for formal review and comment as an

off-agenda item and a public hearing was set for two weeks

later, October 4, 1983. See Fraley Exh. 22. On September 21st,

certain public officials were notified, through a letter from

the County Administrator, of the Board action of the previous

day. Fraley Exh. 22. Attached to the cover letter were maps of

— ^ DISTRICT 2 UNINCORPORATED TRACTS TO BE TRANSFERRED TO DISTRICT 3 —— ----------

Census Tract Total White Black Other338 4763 3984 80 699339 3908 2996 229 683357 900 (part -Planning Dept. estimate358 4535 4050 24 461359 4899 4372 22 505360 4208 3789 18 401361 4101 3634 20 447Total 27,314 22,285 393 3196

Fraley Exh. 20, 21 I-J.

only)

16/ DISTRICT 4 TRACTS TO BE TRANSFERRED TO DISTRICT 2

Census Tract Total White Black Other311 2926 2715 56 155312 4464 4011 112 - 341Total 7390 6726 168 496

Fraley Exh. 20, 21 I.

18

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

the current districts, the September 19th preliminary map and

the Planning Department's population data for both maps. This

was the first public notice that the Board was considering a

specific proposal for redistricting. Although "input" from the

officials was "welcome," the cover letter did not invite alter

native proposals or state that any would be considered. Id.— ^

Thereafter, on September 28th, the County Admini

strator sent out a notice to various local officials reiterating

the October 4th hearing date and attached two other maps, Map A

and Map B. Fraley Exh. 24. The letter stated that, "The Board

wants your input on how to achieve greater equality of

population within each district, while continuing to reflect

other concerns involved in establishing district boundaries."

Id. Map A was characterized as "a refinement of the map you

received previously" (i.e., the green-line map) and Map B as a

variant of Map A. J[d. The population estimates for the

districts set forth in Maps A and B were both closer to ideal

population than the original green-line proposal. See id.

Two days later, on September 30th, the Planning

Director transmitted to the Board a revised Map A and Map B,

Fraley Exhs. 35 and 36, in which "some minor adjustments" were

17 /— Supervisor Cooper testified in deposition that he and

his legislative aide, Charles Brown, held a meeting on

September 26, 1983, with certain invited black "community"

members. The meeting was not open to the public. At the

meeting, Supervisor Cooper and his aide presented as redistrict

ing options, the green-line map (or a plan similar to the green

line map) and a plan in which the greater part of San Leandro

would be transferred into District 3 and more of East Oakland

would be moved into District 4 than under the green-line map.

The consensus of the meeting was that the green-line map was

preferable to the latter alternative. Cooper Depo., pp. 27-29.

19

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

If 5

made to Maps A and B "as a result of refining figures and to

reflect election precinct lines." Fraley Exh. 25. Revised

Maps A and B were not made public until October 4th. See id.

The basic changes proposed for District 3 in the

September 19th green-line map were carried forward into the

revised Map A. The most substantial differences were (1) two

additional heavily black East Oakland-Bancroft census tracts

were transferred from District 3 to District 4, and one less

majority white Lake Merritt tract went from District 3 to

TO/District 4— ; (2) an additional tract of unincorporated area

was transferred from District 2 to District 3— ;̂ and (3) three

census tracts were moved into District 5.— ^ District 3's

proposed population was estimated in revised Map A as 228,000.

18/ EAST OAKLAND TRACTS TO BE TRANSFERRED TO DISTRICT 4

Census Tract Total White Black Other

103 2914 348 2332 234

104 2966 630 2115 221

Total 5880 978 4447 455

Tract 034, majority white, was ultimately transferred from

District 3 to 5, not District 3 to 4, as provided in the greenline map. See note 13, supra. Fraley Exh. 36.

19 /-- DISTRICT 2 UNINCORPORATED TRACTS TO BE TRANSFERRED TODISTRICT 3 --------

Census Tract Total White Black Other340 3161 2601 83 477

Fraley Exh. 36.

— / OAKLAND TRACTS TO BE TRANSFERRED TO DISTRICT 5

Census Tract Total White Black Other033 (from Dist.3) 1980 333 165 1482034 (from Dist.3) 3351 1888 800 - 663041 (from Dist.4) 5176 4318 303 555Total 10,507 6539 1268 2700

Fraley Exh. 36.

20

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Fraley Exh. 25. Revised Map B would have transferred all of San

Leandro from District 4 to District 3 and would have transferred

more of Oakland, including substantial black populations, from

District 3 to District 4 than revised Map A proposed. Id.

Both the September 21st and 28th notices were sent, at

the Board's direction, only to cities, chambers of commerce and

the County's legislative delegation. Excell Exh. 8. Neither

notice invited general public participation at the hearings and

neither invited alternative proposals. Neither notice indicated

the racial impact of the Board's redistricting proposals.

Finally, neither notice disclosed that the Board was planning to

vote on October 4th to adopt a redistricting proposal.

Four written responses to the September notices — all

from cities — appear in the record. Excell Exh. 8. Three

cities mentioned a previously-scheduled California League of

Cities meeting occurring on the same day as the hearing

(Hayward, San Leandro, Fremont). Of these, two asked for a

continuance of the October 4 hearing because of the short notice

and the pre-existing League of Cities meeting date (San Leandro,

Fremont). San Leandro and Fremont both also expressed

substantive objections to the proposed plans because the plans

contemplated splitting each of these two cities between two

supervisorial districts. The fourth city to respond, Albany,

wrote that it had no comment on the plans because it was not

affected by the redistricting.

On October 4, 1983, the Board held a brief public

hearing, the only public hearing ever held on the redistricting

issue, before introducing a slightly modified revised Map A for

21

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

first reading and vote as Ordinance 83-077. At this hearing,

virtually all speakers asked for more time for public partici

pation and for the appointment of a citizen advisory committee.

Public Hearing Trans., pp. 9-29. Specific questions were

asked and comments were made about the proposed reduction in the

black population of District 3. Jld. See text at p. 60-61,

infra. A majority of the Board members have admitted that they

knew beforehand that the Redistricting would have an impact on

District 3's black population. See Cooper Depo., pp. 28-29,

Bort Depo., pp. 80-83, Santana Depo., pp. 22-23, George Decl.,

11 3. Nevertheless, the Board voted 4 to 1 to adopt revised

Map A without material change. Public Hearing Trans., pp. 51-

21/53.— See Map 2, attached herewith. The one vote against

21/— The initial vote was Supervisors Cooper and Excell in favor and Supervisors George and Santana opposed, with Bort ini-

tiallY passing. Public Hearing Trans., pp. 51—52. Supervisor Bort and Supervisor Santana then changed their votes and revised Map A was adopted 4-1. JEd. at 52-53.

District 1 Supervisor Excell testified in deposition

that either revised Map A or revised Map B was acceptable to him

because both equalized population, provided unincorporated areas

for District 3, and had the same impact on District 1. Excell

voted for revised Map A because it had the support of other supervisors. Excell Depo., Vol. II, pp. 11-14.

District 2 Supervisor Santana testified that he was indifferent about whether there should be a redistricting, he

had no specific political goals of his own, and he thought that balancing population and keeping cities intact were his only concerns. Santana Depo., pp. 6-8, 16, 46-47.

District 3 Supervisor Cooper testified that he erron

eously believed redistricting was required by law, that the

County was legally vulnerable to a- lawsuit in which a judge

would redistrict the County if the Board did not redistrict, and

that Assemblyman Harris had told him that he and Oakland Mayor

Wilson were interested in East Oakland being moved to District 4

in exchange for San Leandro. Supervisor Cooper stated that he

[Continued]

22

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

revised Map A was cast by District 5 Supervisor George who had

earlier in the debate expressed concern about the impact of

revised Map A on blacks and had tried unsuccessfully to delay a

vote and create a task force to study the matter. Id. at pp.

42-44.— ^

It was not until October 7th, three days after the

public hearing and initial adoption of revised Map A, that the

Planning Department sent to the Board any information about the

racial impact of revised Map A. This data, which was not made

public, showed the following racial breakdown of the revised

Map A districts:

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

— / [Cont'd.]

voted for Map A because he wanted to preserve as much of Oakland as possible. Cooper Depo., pp. 10-13, 18-21, 83-86.

District 4 Supervisor Bort testified that he did not believe any redistricting was called for, but voted for revised

Map A in order to avoid adoption of Map B by the Board. Bort Depo., pp. 99-100.

22/ At the hearing, Supervisor George presented a plan

that attempted to avoid the fragmentation of Oakland areas with

substantial black population by moving the entire East Oakland

black community into District 4. Supervisor George felt that

this was the only realistic way to preserve the integrity of the

black community while accommodating Supervisor Cooper's desire to eliminate black voters from District 3. George Decl., 1f 5.

23

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Am. Indian Asian &

Eskimo & PacificDist. Total White Black Aleut. Islander Other

1 230,149 203,868

(88.6%) 4,515

(2.0%) 1,531

(0.7%) 10,056

(4.3%)- 10,079(4.4%)

2 229,499 167,308

(72.8%) 13,233

(5.8%) 2,000

(0.9%) 22,655

(9.9%) 24,303(10.6%)

3 228,753 118,865

(52.0%)

71,587

(31.3%) 1,824

(0.8%) 17,880

(7.8%) 18,597

(8.2%)

4 229,424 155,463

(67.8%)

45,931

(20.0%)

1,212

(0.5%) 18,001

(7.8%) 8,817

(3.8%)

5 227,292 122,943(54.1%) 73,891

(32.5%) 1,169

(0.5%) 20,530

(9.0%) 8,759

(3.9%)

Fraley Exh. 27, as corrected October 27, 1984 in Fraley Exh. 6

(District 5 figures revised) (Spanish origin omitted)

Even though the Board had before it the precise racial

data, it again voted in favor of revised Map A on October 11,

1983. Public Hearing Trans., pp. 54-55. The ordinance went

into effect 30 days later.

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

23/— The Planning Department derived the 1983_-racial

statistics for supervisor districts by applying 1980 U.S. Census

racial percentages to 1983 State Department of Finance statistics. Fraley Exh. 33.

- 24 -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

2G

27

28

6. Impact of 1983 Redistricting.

As stated above, the racial composition of District 3

before the 1983 redistricting, according to the U.S. Census

Bureau and the Alameda County Planning Department, was as

follows:

Race Percentage Number

Black 42.3

White 38.8

Asian 9.7

Native Amer. .8

Other 8.4

93,390

85,663

21,416

1,766

18,546

Total 100 220,781

Petition at H 18, p. 7. The racial composition of District 3

after the 1983 redistricting, according to the Alameda County

Planning Department, is as follows:

Race

Black

White

Asian

Native Amer

Other

Total

Id. at U 18, p. 8.

Percentage

31.3

52.0

7.8

.8

8.2

100

Number

71,587118,865

17,880

1,824

18,597

228,753

The redistricting reduced District 3's black popula

tion from 93,363 to 71,387, resulting in a net loss to

District 3 of almost 23,000 black residents, or almost a quarter

of the black population of the district, ^d. The percentage of

blacks in District 3 dropped from approximately 42.3%, the

largest black representation in any supervisorial district, to

approximately 31.3% as a result of the redistricting. Id. The

redistricting increased the white population of District 3 from

85,663 to 118,865, resulting in a net gain to District 3 of

25

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

5

approximately 33,000 white residents. While whites comprised

only 38.8% of District 3's total population before redis

tricting, District 3 emerged with a clear white majority of

approximately 52%.

Redistricting resulted in substantial alterations in

the racial composition of preexisting districts only in

District 3, where the white proportion of district population

increased 13.2% and the black proportion decreased 11.0%, and

District 4, where the black proportion of district population

increased 8.8% and the white proportion decreased 10.3%. In no

other district did any racial or ethnic group's representation

change more than 1.9%.— ^

The population growth that ostensibly necessitated

adjustment of the supervisorial districts in 1983 had occurred

in Districts 1 and 2 in the southern part of the County. Dis

tricts 3, 4, and 5, located in the north County, each needed

population added to them if population of the districts were to

— / The following table shows the percentage changeeach group's

redistrictingrepresentation m a district

Am. Indian

Eskimo &

resulting

Asian &

Pacific

from

District White Black Aleut. Islander Other

1 + 0.8 - 0.1 + 0.6 - 0.12 - 1.2 - 0.4 + 0.6 + 0.23 + 13.2 -11.0 - 1.9 - 0.24 -10.3 + 8.8 + 1.0 + 0.45 + 0.4 - 1.0 + 0.6 + 1.2

These percentage changes were calculated based upon the pre-

redistricting racial breakdowns, see supra at n. 3, , and

Planning Department post-redistricting figures, Fraley Exh. 4.

26

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

f 5

be equalized. District 3 required an increase of approximately

8,000 residents. Petition at U 18, p. 8. Although both

District 3 and District 4 required an increase in population to

achieve population parity, twelve Oakland census tracts, seven

with majority black populations, were transferred from Dis

trict 3 to District 4,— ^ and five tracts, all at least 80%

white, were transferred from District 4 to District 3.— ^ The

transfer of black population from District 3 to District 4

accounts for almost all the loss of District 3's black popula

tion in the 1983 redistricting. See supra at nn. 13, 18, and

20. The transfer of precincts between Districts 3 and 4 was

fully half of all the precincts transferred from one

supervisorial district to another under the 1983 redistricting.

Petition at 18(b).

The 1983 redistricting resulted in District 3 taking

on an uncouth configuration. J[d. at 1[ 18(d). Precincts were

gouged out of two sections of District 3 adjacent to the eastern

boundary between District 3 and 4, and moved to District 4. Id.

In the southern part of District 3, precincts from San Leandro

(a separate city) were split off from District 4 and added to

District 3, and unincorporated areas from District 2 were added

25/— ' See supra at nn. 13 and 18. Seven of the 12 tracts

had populations greater than 50% black and only one had a

population greater than 50% white. Id. Of the remaining four

majority non-white tracts, the black population was a plurality

of the total tract population in two of these tracts. Id.

26/— ' See supra at n. 14. Not one of the five census tracts had a black population over 3%. Id.

27

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

5

to District 3, including virtually all-white precincts that form

a triangular island connected to District 3 by only a narrow

corridor. Id.

7. Subsequent History of the 1983 Redistricting.

After the passage of Ordinance 83-077, a referendum

petition protesting the adoption of the ordinance was circulated

by District 3 residents. See Swanson Decl., H 7. A petition

containing 41,225 signatures was timely filed on November 9,

1983, within the 30-day period prescribed by Elections Code

§§ 3751 and 3753. However, the Registrar of Voters found an

insufficient number of valid signatures on November 23rd.

On November 21st, Oakland Mayor Lionel J. Wilson wrote

Supervisor Excell protesting the redistricting, "which divides

up the large minority population of East Oakland and substan

tially disenfranchises some 60,000 East Oakland people," as a

"blatant rape of the rights and interest of thousands of Oakland

residents." Excell Exh. 17. In subsequent correspondence,

Wilson stated that the redistricting plan "effectively disen

franchises a substantial portion of the City of Oakland on the

Board of Supervisors." Excell Exh. 18.— ^

27/— Mayor Wilson's November 21st letter, in its entirety, states

I was shocked and truly disappointed to learn

that you had joined with Fred Cooper to pass Ordinance

No. 0-83-077 which divides up the large minority population of East Oakland and substantially

disenfranchises some 60,000 East Oakland people.

Unfortunately, I have been out of the City from

time to time recently and was, therefore, unable to

[Continued]

28

1 On December 6, 1983, a motion was introduced by

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Supervisor George, seconded by Supervisor Excell, to appoint a

fifteen-person citizens commission to study redistricting of

supervisorial boundaries. Cooper Exh. 10. The motion was

rejected by a 3-2 vote. Supervisors George and Excell voted for

the motion, and Supervisors Bort, Cooper, and Santana voted

against. Id.

A second petition drive in support of an intitiative

to overturn the redistricting was launched May 8, 1984 by a

coalition of political, labor, and environmental leaders from

several of the supervisorial districts. See Swanson Decl., V 7.

/

i

13 /

14 /

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

/

/

— / [Cont'd]

become actively involved in the development to take

the issue of county redistricting to the people

(despite my strong aversion to government by

initiative process). This blatant rape of the rights

and interest of thousands of Oakland residents is

certainly inconsistent with the seeming fair-minded,

rational and objective Don Excel [sic] I had come to

know and respect. Fred Cooper's actions are more

readily understood within the context of "a drowning

person reaching for a straw."

I do hope that some resolution of the issue is

found that will effectively deal with this grave

miscarriage of justice — and although I am having all

legal aspects researched, hopefully it won't have to

be resolved through litigation.

Excell Exh.17.

ccllO# 5 29

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

IV. SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.

This case concerns an egregious and unjustified

interference with the voting rights of a racial minority.

Because the right to vote is a fundamental right and the group

subject to discrimination is a racial minority, the Court must

subject the 1983 Redistricting to "active and critical"

scrutiny.

A violation of the equal protection clause of

Article I, § 7 of the California Constitution may be established

either by demonstrating that the 1983 Redistricting has the

effect of reducing minority voting strength or by proving that

the Redistricting was purposeful racial discrimination. In the

instant case, petitioners present undisputed evidence of both

adverse impact and discriminatory purpose. The adverse impact

of the 1983 Redistricting is clear and unequivocal: a substan

tial reduction of black voting strength in District 3, such that

over one-fifth of the black population was lost, and a nearly

40% increase in white population. The existence of a clear

discriminatory effect alone establishes respondents' liability

under the state equal protection clause. Petitioners also

demonstrate that the 1983 Redistricting process and outcome were

the product of intentional discrimination. Disproportionate

racial impact, substantive irregularities, procedural irregu

larities, the historical background of the action, and the

legislative history of the 1983 Redistricting, together

establish that respondents' adoption of the redistricting plan

was purposeful racial discrimination.

/

30

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Nor can respondents excuse or justify their actions.

Respondents are unable to carry their heavy burden of showing

that the 1983 Redistricting furthered a compelling governmental

interest and that the Redistricting was necessary to further

this compelling governmental interest. The various reasons

advanced by respondents simply do not stand up to the rigorous

analysis required by law.

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

/

31

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1G

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

v . ARGUMENT.

A. AN ELECTORAL SYSTEM OR PRACTICE THAT SIGNIFICANTLY

IMPAIRS THE RIGHT TO VOTE OF A RACIAL MINORITY IS

SUBJECT TO "ACTIVE AND CRITICAL" JUDICIAL SCRUTINY.

The right to vote has traditionally been considered

the single most fundamental right, for it is the right with

which we preserve and protect all other basic civil and

political rights. Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 560 (1964);

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370 (1886). As a result, the

California Supreme Court, interpreting the state equal

protection clause, has held that any electoral system or

practice that significantly impairs the right to vote is subject

to "active and critical" judicial scrutiny. Westbrook v.

Mihaly, 2 Cal.3d 765, 785 (1970), cert, denied, 403 U.S. 922

(1971). See Choudhry v. Free, 17 Cal.3d 660, 664 (1976); Gould

v. Grubb, 14 Cal.3d 661, 670 (1975); Curtis v. Board of