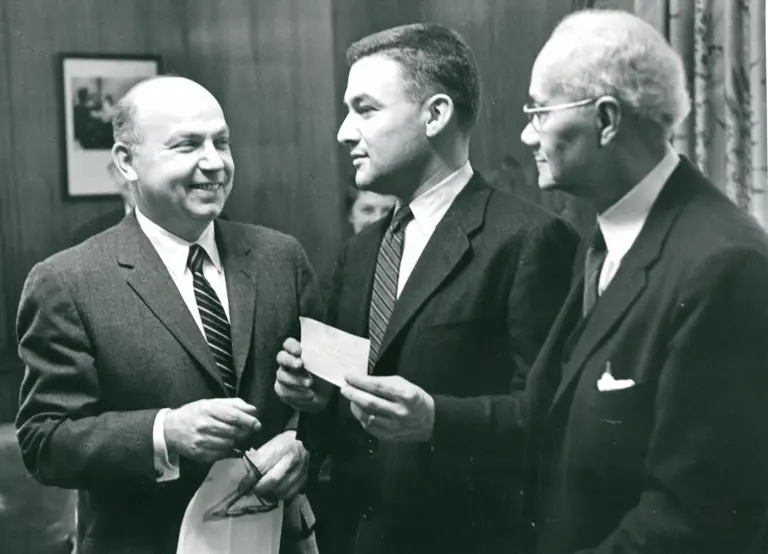

Greenberg, Jack; and Others, 1995, undated - 73 of 114

Photograph

January 1, 1995

Photo by Ed Bagwell

Cite this item

-

Photograph Collection, LDF Staff. Greenberg, Jack; and Others, 1995, undated - 73 of 114, 1995. f24b5dd5-c154-ef11-a317-6045bdd88b0e. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/af3a858c-b538-4977-86fd-036b5e4b8caf/greenberg-jack-and-others-1995-undated-73-of-114. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

X-TIKA:Parsed-By org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser X-TIKA:Parsed-By-Full-Set org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser Content-Length 4885381 Content-Type image/jpeg