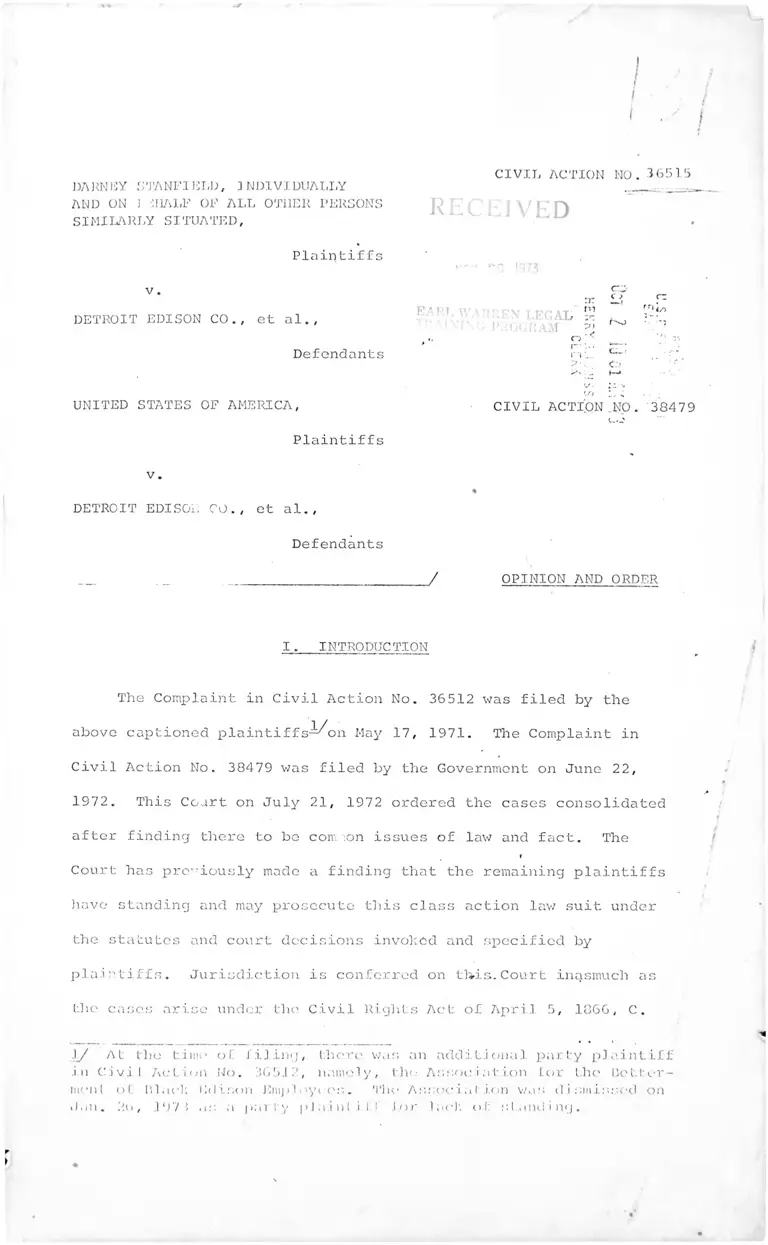

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co. Opinion and Order

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co. Opinion and Order, 1973. 15fd4bae-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/af53749a-5d1d-4654-a912-2e62464ee1e7/stamps-v-detroit-edison-co-opinion-and-order. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

CIVIL ACTIONDARNNY STANFIELD, INDIVIDUALLY

AND ON ) '.HALF OF ALL OTHER PERSONS

SIMILARLY SITUATED,

I

Il

f

NO. 3 651.5

Plaintiffs *irw or tq7

DETROIT EDISON CO., et al.,

Defendants

EAR!. ■ EN F' AL

:rrm

RAM o •t--1' i

r z

< >

C .- »o

rr, i

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, CIVIL ACTION.NO. '38479

Plaintiffs

v.

DETROIT EDISON CO., et al.,

Defendants

/ OPINION AND ORDER

I_.__INTRODUCTION

The Complaint in Civil Action No. 36512 was filed by the

above captioned plaintiffs-^on May 17, 1971. The Complaint in

Civil /action No. 38479 was filed by the Government on June 22,

1972. This Court on July 21, 1972 ordered the cases consolidated

after finding there to be common issues of law and fact. The

f

Court has previously made a finding that the remaining plaintiffs

have standing and may prosecute this class action lav/ suit under

the statutes and court decisions .invoked and specified by

plaintiffs. Jurisdiction is conferred on thas. Court inasmuch as

the cases arise under the Civil Rights Act of April 5, 1866, C.

1/ At the time o E filing, there was an additional party plaintiff

in Civil Action No. 36512, namely, the Association for the Better

ment of Bln eh Edison Emp.l oyecs. The Association was dismissed on

Jan. 2i>, 1973 as a parly j > I n.i n l i I.!’ for 1 net o I: s landing.

4*

3.1, 14 Slat;. 140, 4 2 U.S.C.A. § 1981; the Civil Rights.Act of

1964, 78 Stat. 259, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000-5(c); the National Labor

Relations Act, 61 Stat. 136, 29. U.S.C.A. § 151 and 185; and 28

U.S.C.A. § 2201 and 2202o

II. THEORIES OF THE PARTIES

The Final Pretrial Order entered by this Court and signed

by all parties dated January 12, 1973, states the following

theories of the litigants:

A. THEORY OF PLAINTIFF UNITED STATES:

The following is a brief statement of the government's

theory:

Until recent years, the defendant Detroit Edison Company

discriminated against its black employees by excluding

them from its desirable jobs except in token numbers.

Prior to the end of 1968 the Company employed a rela

tively small number of blacks in a few jobs, primarily

as janitors and servicement in the Building and

Properties Department, as utility servicemen and more

recently as laborers and stockmen in the Stores and

Transportation Department0 These few jobs in which

blacks were employed offered lower pay than most of its

skilled trade occupations and little or no advancement

opportunities. Some whites were also employed in these

low opportunity jobs, but virtually nd blacks were em

ployed in high opportunity, skilled jobs. Many black

employees who were limited to low opportunity jobs

possessed qualifications equal to or greater than many

of the whites whom the Company hired without prior

skills or experience and trained for specific trades

or crafts within the Company. Since 196b, when Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act became effective, the

Company has hired blacks in some formerly all white jobs,

especially in clerical jobs, in increasing numbers; but

its high opportunity hourly paid occupations remained

virtually all white until after 1968, and blacks re

mained concentrated in low opportunity jobs.

The collective bargaining agreements between the

Company and the defendants, Local 17 and Local 223,

grant preference to employees already in high—oppor

tunity departments and occupational groups in

1

competition for vacancies in those departments and

occupational groups and a.l.low employees who trans

fer to new departments and occupational groups no

credit for time spent in their former departments

when competing for future promotions or retention

against layoff. A transferring employee who begins

at the bottom of a new line of progression or occupa

tional group must also work at a reduced pay rate if

this new position pays less than his former position.

Although racially neutral on'their face, these

collective bargaining provisions carry forward into

the present and future the effects of the Company's

pattern of excluding blacks from high opportunity jobs

by allowing whites the benefit of seniority and pre

ferred bidding positions obtained during a time when

blacks were not able to acquire the same advantages.

The Courts have uniformly held that where the effects

of such a pattern of discriminatory job assignment are

carried forward by the operation of such a seniority

system, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 re

quires that the responsible defendants provide the

class of affected black employees with the employment

opportunities they would have received but for the

pattern of racial assignment or exclusion. Therefore,

the government requests an injunction providing an

affected class of black incumbents (i.e., those who

were assigned to lower paying jobs on the basis of their

race) with opportunities to compete for positions in

high opportunity occupational groups on the basis of

their Company seniority, to transfer, if successful,

without loss of earnings, and to carry their Company

seniority with them to such new occupational groups for

all purposes, including future promotions and protection

against layoff. The government also requests a determina

tion that the defendants2 are liable to pay back pay to

those affected class members, who in an ancillary pro

ceeding, may be shown to have suffered financial loss as

a result of the pattern of racially discriminatory assign

ment <,

2. The government expects,the evidence to demonstrate

that the Company is primarily responsible for the discriminatory

practices which have resulted in lost earnings to black employees.

Section 706 (g) of Title VII provides for such’ a determination of

responsibility. However the government is not prepared at this

time to waive all back pay claims against the defendant Unions,

fFootnote quoted from Government's TheoryJ ...

Until the commencement of Title VII enforcement pro

ceeding, and until the present in the case of some

practices, the defendant Company has discriminated

against black applicants and potential applicants for

employment in its recruiting and hiring practices.

Despite recent increases in the number of blacks hired,

in 1972 the Company employed approximately 060 blacks,

making up only 7.5% of the Company's total employment

of approximately 11,500„ Approximately 55% of the

Company's work force is employed in the City of Detroit

which has a black population pf 44%. Approximately

75% of the Company's work force is employed within Wayne

County which has a black population of 27%; and approxi

mately 85% of its work force is located within the three

county area.

The Courts have held in Title VII cases that where

blacks traditionally have been excluded from employment,

affirmative steps are necessary to recruit and employ

qualified applicants. The government therefore requests

an injunction requiring the Company to cease relying on

recruiting through friends and relatives of incumbent

employees; to exercise more direct control over the hir

ing decisions of its department supervisors; to remove

test st;ndards as a barrier to black hiring; and, subject

to the. availability of qualified applicants, to recruit

and hire blac];s throughout the Company and in specific

occupational groups in accordance with numerical goals

sufficient to overcome past exclusion of blacks within

a reasonable time.

B. THEORY OF PRIVATE PLAINTIFFS:

The theory of private pi: intiffs Complaint is as

follows:

Racial discrimination with regard to both hiring and pro

motion is proved by the small number of black employees-

employed at Detroit Edison. The percentage of blacks

employed in the work force of Detroit Edison — particu

larly in the classifications of. official/, manager, and

skilled craftsmen — is substantially smaller than the

percentage of blacks in the City of Detroit. Overt and

active racial discrimination has been practiced by

defendants against individual black employees through

1973.

Certain practices, arguably neutral and non-discriminatory

on their face -- have the effect, of perpetuating past

discrimination and embody such discrimination in the

present system:

4

.1 . Ward of mouth referrals by incumbent white

employer: of Edison and flic compilation of

lists of employees who have been recommended

by such incumbent whites by various Edison

Department Heads.

2. An interview system which does not put employ

ees on notice as to the job opportunities in

the company and which accordingly has the effect

of denying blacks higher paying jobs because

their friends and relatives are blacks, and un

likely to have held sucli jobs or to know of such

jobs in any kind of detail.

3. A departmental and job seniority system utilized

for competitive status jobs which penalizes the

black employee who has seniority granted in a

lower paying job or department because a past

discriminatory hiring policy has relegated blacks

to such jobs and departments. Moreover, some

black employees would be required to take wage

cuts in order to transfer.

4. Non-job related tests utilized for both hiring and

promotion which have the effect of screening out

blacks disproportionate to whites and/or preserve

the discriminatory status quo.

5. Educational and other non-job related requirements

which screen out blacks disproportionate to whites

and/or preserve the discriminatory status quo.

6. Subjective criteria and interview system which

screens out blacks disproportionately both from

employment and better paying jobs and/or preserve

the discriminatory status quo.

7. Subjective criteria utilized by supervisors and

other responsible corporate officials and/or pre

serve the discriminatory ptatus q\io.

8. The existence of all white and near all white super

visory workforce has the effect of excluding black

employees from consolidation for both hiring and

promotion.

Defendant unions liability are specifically predicated

upon the following factors:

The negotiation of the above-referred-to-seniority sys

tem which embodies within it the effects of past dis

crimination;

The failure to take any kind of affirmative action through

negotiation, arbitration, or any other means to alter

defendant Edison's' discriminatory hiring and testing

policy;

Individual instances of discrimination against black

employees who had appropriate seniority credits under

the collectively negotiated system but who neverthe

less were excluded for other reasons and for whom the

union refused to act affirmatively;

Black employees denied promotion because of discrimina

tion:

The difference between the amount of pay in the job or

department where discrimination has prevailed and the

amount of pay that such employee has in fact received.

Black employees denied hiring because of discrimination:

The difference between the amoun of pay in the job or

department in which discrimination prevailed and the

amount of pay that such individual earned or might have

earned with reasonable diligence.

Edison, through its supervisory and other employees has

retaliated, intimidated and interrogated Black employees

because of the filing of the original complaint with

the Equal'Employment Opportunity Commission and the sub-

s< quent suit filed in the District Court.

c. THEORY OF DEFENDANT EDISON COMPANY:

The vaguely-worded allegations, charges, and claims made

against Defendant Detroit Edison Company (hereinafter

referred to simply as Defendant) are without basis in

fact or law. Defendant continues to deny each and e,rery

one of them.

Affirmatively, Defendant says that its employment

practices have been and are free from racial discrimina

tion. If any of its employment practices have resulted

or do result in differential racial impact (and Defendant

does not admit that they have or do), such practices have

been and are necessary to the business in which Defendant

engages. Defendant has and does recruit, hire, transfer,

and promote qualified persons, according to their avail

ability and their ability without regard to race or color.

Any exceptions to this policy have been and are in favor

of black persons pursuant to the standards set' down by

federal and state government.

Furthermore, Defendant has and docs vigorously, attempt

6

to further the interests of black persons in equal em

ployment opportunity over and above what is required

by law or regulation. True to this goal, Defendant has

pursued and will continue to pursue the development of

an effective affirmative action program at the Detroit

Edison Company.

D. THEORY OF DEFENDANT I,OCAI. 223 :

Local 223 continues to adhere to the denials 'and affirma

tive defenses set out in the answer heretofore filed.

It denies engaging in any act, pattern or practice viola

tive of Title VII. It denies that the collective bargain

ing agreements it has negotiated with the Detroit Edison

Company violate the law. It denies that it has failed or

refused to represent any person or group of perso 3 em

ployed by the Detroit Edison Company or has differen

tially treated any person or group of persons for which

it is the recognized collective bargaining agent employed

by the Detroit Edison Company because of the race of that

person or group of persons.

E. THEORY OF DEFENDANT LOCAL 17:

Local 17 continues to adhere to the denials and affirma

tive defenses set out in the answers heretofore filed.

It denies engaging in any act, pattern or practice viola

tive of Title VII. It denies that the collective bargain-'

ing agreements it has negotiated with The Detroit Edison

Company violate the law. It denies that it has failed or

refused to represent any person or group of persons em

ployed by The Detroit Edison Company or has differentially

treated any person or group of persons for which it is

the recognized collective bargaining agent employed by The

Detroit Edison Company because of the race of that person

or group of persons»

III. SUNMtRY OF THE FINDINGS. AND

CONCLUSIONS OF THE COURT

Plaintiffs have alleged, among other things, that The Detroit

»

Edison Company has traditionally excluded blacks in a discrimina

tory manner from its high opportunity skilled trades and supervi

sory positions and that it con Lin ..-s to discriminate against blacks

7

1

in its hiring and promotion policies and practices. The plaintiffs

have also alleged that the Defendant Unions, which are jaarties to

collective bargaining agreements with the Company, have aided and

abetted the Company in its discrimination.

This Court has listened carefully to the presentation of

evidence in the course of a three month trial in this cause. The

evidenc was overwhelming that invidious racial discrimination in

employment practices permeates the corporate entity of The Detroit

Edison Company. The Court finds as proven facts that upward mobility

of blacks presently employed at Detroit Edison is almost non-existent,

and that qualified potential black employees are refused employment

or refrain from applying for employment because of the Company's

reputation in the Black Detroit Community for racial discrimination.

The Company has taken the position that if any inequities exist be

tween blacks and whites at Detroit Edison, such inequities have acci

dentally evolved and have not resulted from deliberate discrimination.

While this Court believes' that the lav/ would require it to find that

Detroit Edison has violated the law if it ha-s, without intent to

discrimim e, fostered practices which have resulted in a racially

discriminatory impact, the evidence in this case demonstrates that

the Company's discrimination has been deliberate, and by design.-?/

2/ "Proof of actual intent to discriminate is not a prerequisite to

a finding of an unlawful employment practice. Intent is inferred

from the totality of the conduct. All we need to show is that 'X'

intended to engage in the practice that has a discriminatory impact,

not that 'X' intended to discriminate. 1X ~ may not even be aware that

the result of his or her practices are in fact discriminatory. ’idle

relevant test for determining whether a practice is discriminatory is

whether the effect of it serves to exclude; a disproportionate number

of persons in a protected class. An employ cm ent practice which is based

f!

It is the conclusion of the Court that Defendant Detroit

Edison must alter its posture in the area of race relations and

immediately begin to deal with the problem of racial discrimina-%

tion seriously and with moral integrity if it is to fulfill its

obligation under the law. It is a matter of public knowledge in

this community that new leaders have tpken over the management of

this important Company. It is imperative that, if this Company

is to move forward economically and competitively as its manage

ment wants it to, equal employment opportunity for all must be

one of the yardsticks, as well as increased sales and profit

margins, by which the Company measures its achievements and

accomplishments.

It is unfortunate in the view of the Court, that the Company

has consistently refused to admit, much less see1: to remedy, that

its employment practices perpetrate racial discrimination. Indeed,

the Company at trial simply denied that it has ever engaged in

racial discrimination in Employment:

"The Court: Is it your position on behalf

of Det oit Edison, Mr. Ford, that

as you have checked the records,

and you have done it very master

fully and meticulously, that Edison

has never been* guilty of any racial

discrimination in its employment

policies?

Mr. Ford: Yes sir.

in part on unlawful considerations is not saved by the fact that

other non-discriminaLory considerations may also have been present."

William II. Brown, Chairman, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

"The Changing Concept of Discrimination," Contact, July 1972, p. 33.

S<. e generally Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

9

The Court: TheL is your position?

Mr. Ford: That is my position, and anybody

that thinks differently is certainly

invited to come forward with the

evidence of it and I don't believe

they can do it." [Transcript, pages

113-114.3

It is the conclusion of the Court, in light of the evidence

adduced, that the Company is refusing‘to acknowledge the obvious

and has therefore adopted an intractable position. Its denials

of culpability only serve to indicate the myopia in the history

of the Company with regard to its recognition and treatment of

the ignoble disease of racial discrimination. Implicit in these

Findings and Conclusions is the guiding principle that the Company

will not be allowed to continue to violate thj law with impunity

and will, instead, be required to implement corrective measures

designed to treat .the root causes of the conditions which bring

the Company in violation of the law0

With regard to the Defendant Unions, the Court has heard evidence

during the course of the trial that the collective bargaining engaged

in by these Unions has resulted in agreements‘perpetrating racial dis

crimination and preventing affirmative action to eliminate racial dife

crimination and the vestiges of such discrimination. The Unions en

couraged black employees to withdraw or not press grievances pro

testing discrimination practices. Collective bargaining agreements

define seniority in a way that represses the possibility of advance

ment by black employees. Defendant Local 223 lias misinformed black

members with advice that unsuccessful bids involving jobs outside

10

their departments. cannot be put through the grievance procedure

under the collective bargaining agreement. Defendant Local 223

has insisted upon adherence to seniority where black members

were involved to a much stricter degree than for whites. Defendant

Local 223 and the Company have deliberately gerrymandered seniority

districts so as to deny black members ̂ promotional opportunities in

the better paying jobs. Defendant Local 223 and Defendant Local

17 have negotiated for and acquiesced in procedures which lock

blacks into low opportunity jobs and have never protested the

obviously discriminatory practices of the Company. The President

of Defendant ^ocal 223 has insisted upon rerun elections solely

for elected black officials, has attempted to exclude blacks from

leadership positions, and has failed to take steps against threaten

ing and hostile actions and attitudes of white members expressed

towards black members. Defendant Local 17, by referring workers

to the Company ha directly aided and abetted the Company's dis

criminatory hiring practices. The unions have an especially heavy

burden to represent the best interests of all of their members.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that they failed to do so in this

case.

The long and short of the evidence with respect to the De-

f

fondant Unions is simply that the Unions have promoted the interest

of its white members without regard to the interests of its black

members, and have ignored the plight of the black members in gain

ing the equal employment opportunity that xs ‘their due 'under the

Constitution and laws of the United States. Tragically, the Unions

which one would look to for leadership in improving the lot of this

sector of the population, have instead become an obstacle to human

progress (o the point where the 'Court, lias reluctant ly concluded

lli.it th arc just it i a I > J y made delonda nI s .in this law suit.

and the statutes enacted byThe Constitutional provisions

Congress on the subject of equal employment opportunity aid find

their objective in the brief and eloquent phrase of Thomas

Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence:

"We hold those truths to be self-evident, that

all men are created equal, that they are en

dowed by their Creator with 'certain unalienable

Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and

the Pursuit of Happiness. ***"

In the modern industrial society which is the United States,

and certainly in the modern industrial urban society which is

Detroit, to be denied an equal chance at decent employment, and

an equal chance at advancement within one's employment, is to be

denied that equality so nobly articulated by Jefferson. It is in

this context unthinkable that a person would be den' d equal em

ployment opportunities at The Detroit Edison Company when employ

ment to a man means earning a living which will enable him to pro

vide adequately for his family and provide a good education for

his children. Being denied a job is demeaning to a person and

strips him of his dignity and assurance. A person has a right to

extend his God-given working abilities to their fullest without

being encumbered by artificial, irrelevant, insignificant and

fsuperficial barriers, and reasons such as the color of his skin.

The Company and the Unions by their individual and collective

actions arc guilty of denying this fundamental equality to the

members of the class who are the plaintiffs in this law suit, and

the Court will accordingly move on to consider and put into effect

suitable remedies. ...

- 1 2 -

IV. FIN))IUGS OF FACT

A. Preliminary Findings

1. Defendant, Detroit Edison Company, is a public utility,

incorporated under the laws of the State of Michigan and doing

business in a 7,600 square mile area in southeastern Michigan,

where it furnishes electric power to homes, businesses and offices

in the Metropolitan-Detroit area. The Detroit Edison Company em

ploys approximately 11,000 employees.

2. Defendant Local 223, Utility Workers Union of America, is

an unincorporated association doing business in the State of

Michigan and is the exclusive -bargaining representative for approxi

mately 4,000 employees working in job classifications represented

by Local 223 and grouped in approximately 28 bargaining units.

3. Defendant Local 17, International Brotherhood of Electrical

Workers, is an unincorporated association doing business in the

State of Michigan and is the exclusive bargaining representative

for approximately 800 hourly paid employees working in job classi

fications in the Underground Lines and Overhead Lines, Field

Division, of the Transmission and Distribution Department and tlie

Elevator Division of the Building and Properties Department.(

4. The Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA) racial

statistics for 1970 indicate that 44% of the City of Detroit is

»

composed of blacks and 18.2% of the SMSA total population is black.

** ».As of 1971, 73.28% of Detroit Edison's employment positions w< .:e

in Wayne County and 84.11% were in the Tri-County area. As of

1966, 304 of Edison's 9,475 employees were black. At that time,

4 of Edison's 1,722 officials and managers were black (I960 EEOC

Report).

R. Edison Emplc iient. Pract-lces — General]y

5. Testimony shows that for many years Edison employed only

a few blacks and only in menial jobs such as janitor, porter, shoe

shine boy, elevator operator, and utility servicemen. In the

1940's, '50's and '60's prior to and subsequent to July 2, 1965,

Detroit Edison had a reputation of hiring few blacks. Defendant

Detroit Edison lias had a reputation of limiting those blacks who

were hired to low-opportunity jobs such as those which are knowr

as of this time to be 1) In the Property Right of Way Department

— Building Cleaner, Janitor, Porter, Serviceman, Wall Washer,

Lamp Changer, ElevaJ )r Operator and Attendant; 2) In what is now

the Stores and Transportation Department - - all jobs except for

Mechanic; 3) In the Production Department - - Plant Cleaner; 4)

In the Central Heating Plant, Coal and Ash Handler. Such jobs

are low-opportunity jobs because of certain posting, bidding and

seniority provisions which give an almost ab’so1 ute preference to

employees already in high opportunity jobs, units and departments.

C . Union Representation - Background Facts

6. The record reflects that all collective*bargaining repre

sentatives for Local 223, Utility Workers of America; Local 17,

International Brotherhood of Electrical Worters; and Detroit Edi-

*

son are white with the exception of plaintiff Willie Stamps. All

* * • .

collective bargaining representatives of all throe parties have

always been white except for plaintiffs Stamps, James Atkinson

and William Armstead, all of whom have been division chairmen in

Locu 1 U t i l i t y Workers o f Amer ica . o f Defendant

Detroit De i son

S t a mps wa r • the

Local 22? and

All officers

are white. At the time of the trial in this cast ,

only black out Qf approximately 28 chairmen from

the only black on either side of the bargaining table.

D._Spec.iflc Indicia of Racial

Discrimination

7. The evidence submitted in this case indicates that

defendant Detroit Edison Company has in the past assigned those

few blacks who were hired almost exclusively to the low-opportunity

jobs referred to in Finding No. 5, supra. Defendant Detroit Edison

employed no black linesmen in Transmission and Distribution Over

head Lines until 1963. It employed no black sub-station operators

until 1968. It employed no black meter readers unti.'1 1964. The

stated reason of Detroit Edison Company for not employing black

meter readers was that the white community was not ready. Defendant

Detroit Edison or ployed no black appliance repair servicemen until

1962.

8. Beginning in the mid or late 1950's, Detroit Edison

Company had it:. personnel interviewers use a racial code or ident’ -

fication system to identify the race of applicants on application

forms. The system consisted of the interviewers placing a bladei

dot on the application forms of black applicants so that the race

of a black apxxlicant could be easily ascertained at any point in

the hiring process. This Court finds’that the racial code or

identification system was used by Detroit Edison to racially dis-

criminate against black applicants. The defendant Detroit Edison

assorted and maintained through the course of the trial"that this

black clot system war; inaugurated to insure that more blades be

came employed at the Company. The record and testimony in the

case negates this position, and indicates very clearly that the

black dot system was used to perpetuate and maintain blacks in

low paying positions in the Company and exclude them from

others. This coding system was known to and acquiesced in by the

highest levels of Detroit Edison Company's employment office and

management.

9. The disparity in numbers of whites and blacks hired at

Detroit Edison has a historical basis which continues to exist

to this day. In 1955, 232 whites and 4 blacks were hired. In

1956, 199 whites and 5 blacks were hired. In 1957, 97 whites

and 3 black were hired. At some point between 1955 and 1957, the

racial coding system came into being. In 1958, 18 whites and 1

black were hired. In 1959, 29 whites and 1 black were hired. In

1960 39 whites and no blacks were hired. In 1961, 52 whites and

2 blacks were hired. In 1962, 74 whites and 2 blacks were hired.

In 1963, 142 whites and 9 blacks were hired. In 1964, 229 whites

and 33 blacks were hired. In 1965, 481 whites and 34 blacks were

hired. In ligh of the fact that so few blacks were hired, sub

sequent to the implementation of the ra.cia 1 coding system, this

Court can only infer that the racial coding system was instituted

for some purpose other than that of achieving racial equality in

the employment pi. notices of the Edison Company. Indeed, during

the six years subsequent to the introduction_of the racial coding

system the percentage of blacks hired by Defendant Detroit Edison

declined.

16

10. Testimony demonstrates, and this Court finds, that in

many eases black employees with work experience and education

superior to that of white employees in skilled trades, were

denied high opportunity jobs and were assigned to and refused

transfer from low-opportunity jobs, referred to above. White em

ployees lacking a high school diploma -or related work experience

were and continued to be frequently promoted ahead of black em

ployees with high school diplomas and work experience superior to

said white employees.

11. The foregoing-described practices may be illustrated by

a few representative examples. Horace Henry, a black high school

graduate with credit hours at Detroit City College and an inspector

for the government during World War II was refused transfer from

utility serviceman from 1345 through 1962 or 1963. Local 223

Utility Workers Union of America encouraged Mr. Henry to withdraw

grievances protesting transfer refusals. McKinley Ogletree, a

black employee, was hired as a utility serviceman in 1945 and was

an apprentice electrician from 1950 through 1955. Mr. Ogletree

filed numerous requests for transfer to an electrician's job from

1950 to 1969 and was always denied the right to transfer, being

advised by Detroit Edison representatives that "You know you're

not going to get the job." Catherine Gafford and Mary Harris,

black female elevator operators and high school graduates filed

»

numerous applications for transfers in the 1940's, '50's and

‘60's without being given the opportunity tc transfer.

12. Both prior to and subsequent to July 2, 1965, plaintiff

James Atkinson was discriminator!ly assigned to low-opportunity

- 1 7 -

and projobs. In connection will) his applications for transfers

motions, James Atkinson was advised by Detroit Edison representa

tives that it was futile for him to apply and that a'decision

had been made concerning who would get the job before bids were in

vited. In some situations, Atkinson had observed the job performed

whereas the successful white applicant had not. In other situations,

Atkinson had actually performed the work which he sought whereas the

successful white applicant had not.

13. Plaintiff Willie Stamps, a high school graduate with

further education at the Dunbar Trade School in Chicago and

Worshin College of Mortuary Science was discriminatorily refused

employment on at least five occasions at Detroit Edison Company in

1956 and between 1965 and 1967. In 1965 and 1966, Stamps was de

prived of employment on the pretext that he was not properly

dressed and that he was over-weight. On approximately fifteen

occasions between 1967 and 1972, Stamps was denied transfer be

cause of his race. In no instance has the Company contended that

white employees who were selected instead of Stamps possess superior

or equal qualifications. Among the pretexts used to discrimin; te

against Stamps was the contention that he was over qualified for

the job for which he applied. Stamps was also harassed and dis

criminated against by Defendants Detroit Edison and Local 223 be

cause of his civil rights activities at Detrcit Edison.

*

14. The record in this case indicates that in order to im-

plcment and perpetuate discriminatory policies and practices,

Detroit Edison relied heavily on its transfer policies with re

spect to low-opportunity and high-opportunity jobs. High-

opportunity jobs possess pay grades and working conditions

- IE

demonstrably higher and superior to the pay grade of low-

opportunity jobs. High-opportunity jobs for blue collar em

ployees at Detroit Edison are in, for instance, Construction

and Maintenance, the Transmission and Distribution Departments

and the Production Department. Starting pay grades in Construc

tion is generally pay grade 5 ($4.32 per hour). Skilled trade

»

jobs such as Brickmason, Carpenter, Electrician, Mechanic Fitter,

Plumber, Rigger and Welder enable journeymen to receive wages be

tween pay grades 16 ($5,935 per hour) and 18 ($6.27 per hour).

In Transmission and Distribution, the pay grade for Maintenance

Cable Splice;, reaches 18 ($6.27 per hour). In Production and

Senior Plant Operator it reaches 17 ($6.13 per hour).

15. In low-opportunity jobs - - out of which transfer to

high-opportunity jobs is precluded because of Detroit Edison's

posting, bidding and seniority as described below - - the highest

pay '.grade is 5 ($4.32 per hour). For example, Building Cleaner

is pay grade 2 ($4.03 per hour) and Building Attendant begins at

pay grade 0 ($3.89 per hour). Coal-Ash Hardier in Production

(Central Heating) is pay grade 3 ($4,125 per hour) and Plant

Cleaner begins.at 2 and can advance to 3. High opportunity jobs

have been and remain nearly all white.

16. As of April 24, 1973, there were 832 blacks out of

10,630 employees. As of April 24, 1972, there were 12 blacks

*

and 1,099 whites in supervisory positions by the Defendant Detroit

Edison Company. As of April 24, 1972, there were 73 blacks and

1,785 white's in professional and technical jobs. As of April 24,

1972 the 24, 1972, in bargaining unit jobs represented by bocal

.1 9

223, at the Delray Plant, there were 14 blechr. and 113 whites.

There are 9 white firemen earning $4.9 to $5.46 but there arc no

black firemen. There are 20 general mechanics A employees earn

ing $5.26 to $5.93 but there are no blacks. There are seven

white instrument men but no black. The greatest percentage of

blacks at Delray are to be found at the plant cleaner classifica

tion where there are 4 whites and 2 blacks. At the Conner Creek

Plant there are 156 whites and 20 blacks. There are 21 general

mechanic A white employees but no blacks. There are 6 general

mechanic apprentices but no blacks. There are 9 white instrument

men but no black instrument men. Once again, the most significant

percentage of blacks is to be found among plant cleaners where

there are 7 white plant cleaners and 3 blacks. In the Marysville

plant there are 142 white employees and 5 blacks. There are 22

white power plant operators and one black. There are 29 white

assistant power plant operators and two blacks. There are no

blacks in the classification of turbin< operator, auxilliary,

combination firemen, senior plant operator, -water tender, switch

board operator 1st, yard equipment operator, coal handling equip

ment operator, general mechanic A, general mechanic A apprentices,

instrument man, plant warehouse man, and senior .tool crib man.

17. In the Trenton production plant there are 225 white

employees and 3 black employees. Once again there are no black

employees with such classification as general mechanic A, and

general mechanic A apprentice, and instrument man. The only

classification in which blacks arc present arc plant cleaner,

tool crib man and coal handling yard operator. In the St. Clair

P.1 mt, LJioro arc 178 white employees and 4 black employees.

Three of these black employees are in the classification of

plant cleaner and fourth is a serviceman. There are no blacks

in the classification of general mechanic A, general mechanic

A apprentices and instrument man.

18. In the River Rouge plant there are 99 white employees

and 12 black employees. There are 17 white general mechanic A

employees and one black general mechanic A.employee. There are

6 general mechanic A white apprentices and one black general A

apprentice. There are 17 white instrument A men and no black

instrument employees. However, there are 3 white plant cleaners

and 6 blade plant cleaners, tliis classification once again pro

viding the highest percentage of black participation. At the

Industrial Power Plant & Penn Salt there are 52 white employees

and 4 black employees. There are seven general mechanics A white

employees and no general mechanic A black employees. There are

2 general mechanic A white apprentices and one general mechanic

A black apprentice. At the Port Huron plant there are 13 white

employees an I no black employees. At the Monroe plant there are

100 white employees and 2 black employees. There are no black

general mechanic A employees in these jobs at thp Monroe plants.

The 2 blacks are in the classification of plant cleaner and

utility man. At the Wyandotte North Industrial plant there are

37 white employees and 5 black employees. At the Wyandotte South

Industrial plant there arc 50 white employees and 1 black em

ployee.

Ir* 21

s

19. At central Heating there arc 07 white employee a and

16 black employees. In the meter department there are 116 white

employees and 10 black c. ployees. Until, approximately 1960 it

was the practice of defendant Detroit Edison Company to deliber

ately exclude black employees from the meter department because

of the fear of community reaction. Although seniority was not

t

always adhered to in connection with job assignments in the meter

department prior to the time that blacks were hired, once blacks

were hired and protested the undesirable route into which they

were placed beca’ se of their low seniority, defendants Detroit

Edison Company and Local 223 refused to alter such assignments

even though seniority was not uniformly adhered to in the past

in connection with such assignments.

20. In the Stores Department there are 201 whites and 34

blackso In the Transportation Department there are 92 whites

and 22 blacks. The highest percentage of blacks is to be found

in the Utility Servicemen classific 'ion where there are 1.

whites and 13 blacks. Until some point subsequent to July 2,

1965, the Utilities Servicemen classification was one of low oppor

tunity classifications to which blacks were assigned in the over

whelming number of instances. There are 47 white auto mechanics

c

and one black auto mechanic. There are 4 white mechanic appren

tices and 1 black mechanic apprentice.

21. In the electrical substatiohs represented by Local 17,

International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, there.are 334

whites and 15 blacks. There arc no black journeymen first or

2 2 -

second class and out of a total of 67 journeymen positions 3

are held by blacks. In the transmission and Distribution and

Overhead Department, represented by Local 17, IJ3EVJ, there arc

741 whites employed and 21 blacks. There arc 221 white journey

men linemen employed and 4 black journeymen linemen. Ninety-

one apprentice linemen are employed and 6 blacks are so employed.

0

There 105 white journeymen linemen B Crew and 2 blacks„ In most

classificalions in the department, no blacks are employed.

22. In the Transmission and Distribution Underground repre

sented by Local 17, IBEW, there are 337 white employees and 30

blacks. In the journmen and apprentice categories for cable

splicers, there are 170 whites employed and 8 blacks. The most

significant percentage of blacks in the department is to be found

in the labor category where there are 5 blacks and 20 whites. In

the construction field division represented by Local 223, Utility

Workers of America, there are 851 whites employed and 50 blacks.

Among electrical journeymen and apprentices there are 176 whi '-.es

and 8 blacks. Among journeymen apprentice carpenters, there are

34 whites and 3 blacks. There are 34 whites and 4 blades employed

in the Pipe Cover Category. There are 31 white painters and 2 *

black painters. There are 24 Sheetmetal workers and 1 black Sheet

i

metal worker. There are 69 white welders and 3 black welders.

There are 269 white mechanic fitter journeymen apprentices and

11 blacks.

23. In construction Shops Department-represented .by Loca.1

223, there are 14 2 whites and 21 blacks.

- 23

There are no black shop

In the Customer ServiceThere are no black shop machinists.

Divi: ion there are 236 whites and 22 blacks^ In the Metier Read

ing Department Districts there are 378 whites and 10 blacks. Ex

cept for 1 black at the River Rouge Plant, the classificaition of

general mechanic A is all white. The classification of general

mechanic A apprentices remains almost completely white0

24. In Transmission and Distribution and Overhead Depart

ment journeymen and apprentice linemen are almost all white. The

same is true for most other classifications in the department. In

Transmission and Distribution Und- 'ground, journeymen and appren

tice cable splicer are almost completely all white classifications.

In Construction, electricians/ journeymen and apprentice, journey

men and apprentice carpenters, pipecoverers, sheetmetal workers,

welders, and shop machinists are almost all white classifications.

It would be fair to say that there is an almost complete statis

tical absence of blacks in most classifications.

25. In Buildings and Properties Department there are 141

whites and 78 blacks. The overwhelming majority of the blacks

work as janitors, servicemen and elevator operators, which are

the other categories in addition to those of utility servicemen

and others referred to above, to which blacks were restricted in

the overwhelming percentage of instances until some point subse

quent to July 2, 1965.

#

26. Testimony at trial clearly shows that subsequent to

July 2, 1965, defendan. Detroit Edison Company J d, and continues

to have, a reputation in the black community in the Metropolitan

area a.s an employer that generally does not hire blacks and con

tinues to assign those blacks that are hired to low opportunity,

non-promotable jobs such as those described above. Many blacks

who have been hired at Detroit Edison believe that they are for

tunate to be employed with Edison on any basis and they are afraid

to protest the absence of blacks at Detroit Edison in numbers rep

resentative of their presence in the Detroit City population.

27. It is important to observe that until some point sub

sequent to July 2, 1965, all hiring interviewers who hired em

ployees for defendant Detroit Edison Company were white. Through

the present date no attempt has ever been made with either black

or white interviewers to determine whether such interviewers are

racially prejudiced nor have any steps been taken to correct such

prejudice if it exists.

28c Applicants are asked if they have relatives employed by

the Company. A percentage of employees hired by Detroit Edison

have been hired as the result of contacts through friends and

relatives. A study of the Federal Bureau of Investigation in the

course- of which 06 white employees were contacted indicates that

43 of such employees had friends and acquaintances who were em

ployed by Detroit Edison and discussed job opportunities with such

friends and relatives. Since a disproportinate percentage of em

ployees at Detroit Edison Company are white and since the over

whelming percentage of employees in the higher opportunity jobs

** ..

referred to above are white, such a hiring practice in this instanc

had the effect of perpetuating the exclusion of black applicants

25

from employment with Detroit Edison Company and from the jobs

referred to above.

29. Interviewers and sup rvisory personnel in high oppor

tunity jobs and departments make the final decision regarding

who is to be employed in such departments. Hiring takes place

as the result of word-of-mouth recruitment. In order to advance

to high opportunity jobs and departments such as Production, Con

struction, Transmission and Distribution and Electrical Substa

tions, employees must be hired into those departments at an entry

level in practically every instance. All interviewers and super

visory personnel in departments which contain higher opportunity

jobs are white. Supervisory personnel in departments which con

tain higher opportunity jobs are white. Supervisory personnel

in such departments have no personal and social contact with

blacks. Thirty-five and four-tenths percent of white employees

who applied to Detroit Edison Company in 1969-1970 had relatives

employed by the Company. Sixteen and three-tenths percent of such

white employees had relatives in the same department where they

sought employment. Thirty-seven and one-half percent of white

employees have relatives employed by the Company. Fourteen and

two-tenths percent of the white employees have relatives employed

. n the same department. This phenomenon in practice perpetuates

the racial composition of the work force. Until September, 1972,

Edison

viewer

s applicants were asked if they had arrest records. Inter-

, until the eve of the trial of this case, have been re

quired to make extremely subjective judgments about an applicant's

per so1 nl.ity, appear, ace, dress and speech. There is no structured

or written format for questions to bo auk eel of applicants

which is provided interviewers by the Company. Defendant

Detroit Edison did not list employment vacancies with the

Michigan Employment Security Commission until required to do

so by law in late 1971 or early 1972.

30. After an employment application is rejected by Edi

son, an employee may renew his application by expressing con

tinued interest in employment with the Company. An interviewer

may mark an application "unrated". This generally means that

the applicant cannot be considered further. If an interest -

in renewal of the application is not expressed by the applicant,

the unrated application will be destroyed at the end of a 6

month period. If a renewal of interest is expressed the unrated

application will be held for another 6 month period. In 1968,

12.5 percent of white applicants and 22.5 percent of black appli

cants were unrated. In 1969 it was 10.9 percent for whites and

18.5 percent f- r 4 blacks. In 1970 it was 17.9 percent for

whites and 26.9 percent for blacks. In 1969 ani 1970, blacks

hired at Detroit Edison Company continued to' be disproportionately

assigned to low opportunity jobs.

E . Testing

31. The only standards which Edison docs apply uniformly

in the selection of applicants arc standards of performance on

written mental ability tests which arp administered to nearly all

applicants who reach the final stage of consideration in the era-

ploymc . department before referral to line department super

visors for final consideration. (Tr. Vol. IX, pp. 1297.130,; Vol.

- 27 -

VII I., p. 44-4G)

32. The Company administers a variety of test, batteries,

each consisting of one or several tests, in its selection of

new employees for entry level hourly paid and clerical jobs.

The following table shows the test batteries which are admin

istered to candidates for those

Test Battery

Mechanical Placement

Clerical Placement

Apprentice Lineman

Apprentice Draftsman

Customer Serviceman

Substation Operator

Apprentice Cable Splicing

Meter Reader

Power Plant

Ilenry Ford Comm. College

Proficiency Tcst

(Cov

entry ..level jobs at issue here

Entry Level Job

Utility Serviceman, Appli

ance Repair, Meter Reader,

Janitor, Construction Laborer,

Warehouse & Yard Laborer,

Metal Shop Helper, Stockman

Messenger, File Clerk,

General Clerk, Telephone

Clerk, Customer Telephone

Rep., Commercial Office

Rep., Computer, Programmer,

FT Steno, FT Typist,

Switchboard Operator, Tab

Machine Operator, Janitor,

Warehouse & iard Laborer

Apprentice Lineman

Draftsman General, Junior

Draftsman, Rodman

Customer Serviceman

Substation Operator

Laborer Conduit

r

Meter Reader

Assistant Power Plant

Operator, Subs tat:' m

Operator Trainee, Coetl

Ash Handler

Construction Laborer

. ■ b . 19)

33. A larger percentage of the black applicants for em

ployment have failed these tests than the percentage of white

applicants for employment who have failed them. Edison's em

ployment department relies on its psychological service's sec

tion for test administration and evaluation. (Tr. Vol. VIII,

pp. 44-46). This section ordinarily evaluates an applicant's

test performance by either reporting him as "acceptable" or

"not recommended" depending on whether he has given sufficient

numbers of right answers and thereby passed certain fixed

standards of performance. (Tr. Vol. XXI, p. 27) . The following

table shows for each test battery listed above, except the

apprentice lineman's battery, 'the approximate proportion of

white and black applicants taking each test who received evalu

ations of "not recommended" and were not hired in 1970 and 1971

1970 1970

Test White Black White Black

Cable Splicer 31.8 66.7 29.2 67.3

Meter Reader 26.7 66.7 0 50.0

Draftsmen 0 0 . 15.8 25.0

Customer Serviceman 51.9 85.7 57.6 61.1

Power Plant Operator 37.8 77.0 37.5 61.9

Substation Operator

Helper 44.6 '78.9 '42.9 69.8

Mechanical Placement 25.2 68.5 24.8 52.8

Clerical Placement 21.4 . 6 3.2 21.7

(Gov. Ex. 91) „

34. Although insufficient numbers oi blacks have taken

the apprentice lineman's battery to conclude from their per

formance that blacks have failed this battery more often than

whites (Gov. Ex. 83), this test would exclude a greater per

centage of blacks than whites if increased numbers of blacks

were measured by it. This battery consists only of tests

which are also included in several other batteries which blacks

have taken at Edison frequently, and they have consistently

scored significantly lower on each of these tests in such

batteries (Tr. Vol. IX, pp. 82-86; Gov. Ex. 8j).

35. For most applicants, both black and white, meeting

the prescribed cut-off scores or performance standards on test

batteries they are given is a prerequisite for employment.

While a small fraction of those applicants hired into some entry

level jobs have not met all of the standards of performance on

all of the tests in the batteries administered for their jobs,

(Gov. Ex. 100) , the overwhelming majority of those applicants

who do not meet these standards are not employed in the occupa

tions for which they are tested (Glv. Ex. 100; 91)„

36. The Company has also administered an entrance examina

tion for the Henry Ford Community College on which a passing

score has been required as a condition of admissrion to courses

offered there as part of the Construction and Maintenance Depart

ment apprenticeship training„ Obtaining such a passing score ha

been an additional prerequisite for entry into these apprentice-

ship programs. (Tr. Vol. VII, p. 122). Among those employees

- 30 -

iI

who could bo race idontilled who have taken this college en

trance examination, the fail’'.re rate among blacks lias been

significantly higher than that among whites (Gov. Ex. 92).

37. Under guidelines promulgated by the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, an employer may use a test which has

the effect of excluding significantly larger numbers of blacks

than whiles only if the test has been shown to be a valid pre

dictor of job performance. "Validity" as used by the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission means that the r lationship of

test scores to an appropriate criterion of job performance must,

at a minimum, be statistically significant at the 95 percent

level of confidence. Stated another way, this means that there

must be no more than one chance in 20 that the relationship be

tween test scores and the measure of job performance occurred

by chance. Guidelines on Employee Selection Procerh res (revised) ,

35 Fed. Reg. 12333, 29 G.F.R. 1607.5 (c) (1)

38. The EEOC Guideline s also require that validity be

established separately or "differentially" for blacks where ab

sence of sufficient numbers of blacks among those employed makes

such differential validation infeasible, the tests in question

may be regarded as Vcilid on the basis of other evidence only pro-

visionally until separate evidence of validity for the minority

group is produced. A test which otherwise has the effect of

under predicting the job performance of blacks should be scored

in such a way as to correct this. 29 C.F.R. 160,.5 (b) (5)

39. Measurements of such relationships, often expressed

3 1

us correlation coeficien ts, are determined by compar.i non of test

scores and performance criteria measures for groups of individ

uals who have been tested and also rated on the job. ' A correla

tion coeficient is high or low depending on whether individuals

in the group tend to have test scores and criterion ratings of

corresponding levels (Tr. Vol. XXIII, pp. 156-160). It is posst-

ble for such a correlation to achieve the level of statistical

significance required by the EEOC Guidelines while a substantial

number of the individuals in the group among whom the correlation

is computed have combinations of test scores and performance cri

terion rating: contrary to the trend, that is substantial numbers

receiving high test scores may have lower performance ratings

than others who received lower test scores and substantial numbers

who received low test scores may ha\a received higher performance

ratings than those receiving higher test scores (Tr. Vol. XXIV,

pp. 4-5, 96-98, 101-109, Gov. Ex. 103, p. 345, Gov. Ex. 107).

40. The EEOC Guidelines, also require that cut-off scores

or test standards must be related to "normal, expectations of

proficiency" in the work force and that they be reasonable, 29

C.F.R. 1607.6. Unless the relationship, or correlation, between

test performance and criteria of job performance^ is very high,

a reasonable cut-off score should eliminate only those applicants

who are likely to be insufficiently qualified to perform the job

»

satisfactorily (Tr. Vol. XXV, pp. 85-88).

41. None of the test batteries described in the proceeding

findings has been demonstrated both to Ido valid predictors of

job per Tor iri an co/ a:.; measured by statistical comparison to cri

teria of job performance, and to bo used witli performance

standards, or cut-off scores, reasonably designed to eliminate

those app] cants who are unlikely to perform satisfactorily in

the jobs for which they are being considered and tested.

42. Differential validity, that,is separate validity for

blacks -as a group apart from the general population of appli

cants and employees, has not been demonstrated for any of the

batteries in issue here. Differential validation was attempted

or evidence tending toward differential validation was presented,

in only four of the studies described, the clerical and mechanical

placement battery studies done b> National Compliance Company

(Gov. Ex. 102 pp. 115-139): the meter reader battery study and

the assistant power plant operator studies done by Ed'son (Gov.

Ex. 99, 101, Tr. Vol. XXII, pp. 22-23). These studies were in

sufficient to establish validity for whites or blacks, and there

fore they are deficient in evidence of differential validity

(See Findings 99-105, 110, 113-114). • .

43. The customer serviceman battery, which is found to

have been valid at the time of the study, apart from the lack

of justification for its cut off scores,, has not'been demon

strated to be different:? lly valid for blacks as there is no

evidence that there were blacks in the study group in 1965 (Tr.i

Vol. XXI pp. 69-93).

44. Edison has made no effort to validate the Henry Ford

Community College entrance examination (Tr. Vol. XVIII, pp. 6-

133, Vol. XXI, Vo.1 . XXII, Vol. XXI II, pp. 5-47).

33

The only sLanciarein for selection of applicants for'll!.

employment or transfer which arc uniformly applied by the

Company have been passing scores on batteries of mental abil

ity tests administered by the Company. Because blacks gener

ally score lower than do whites on many such tests, several

of the test batteries used by Edison hdve screened out larger

proportions of black applicants than of white applicants. With

one exception, none of these test batteries are valid predic

tors of job performance; and without exception none of them are

valid for blacks as a separate group. One of the batteries in

fact may be "unfair" to blacks in that it under-predicts their

performance relative to whites. Also without exception, all of

these batteries are admin:stewed with cut-off scores which are

unreasonably high, in that they screen out applicants whose

scores are comparable to former and current employees who were

not shown to be unable to perform in their jobs.

F. Specific Indicia of Union InvoIvement

46. Evidence submitted in this case show's that seniority,

as definied by the collective bargaining agreement between Detroit

Edison Company and Local 17 IBEW, is occupational group seniority

and is the measure of seniority to be considered'in matters of

layoffs, rehiring, promotions and transfer within and among the

occupational groups covered by the agreement. Promotions within

each bargaining unit are awarded to the senior bidding employee

possessing the required skills, abilities and/or adaptability.

In a small percentage of the cases, less than .10 percon.t. of them,

the junior employees successfully bid for the job. The posting

- 34

provisions of tiro agreement between defendants Local 17 and

Detroit Edison Company provide that all permanent vacancies in

the bargaining unit will be posted in all divisions of the de-

%

pertinent in which the vacancy occurs except in the case of the

journeymen linemen classification. The promotion and posting

provisions establish a priority f. * employ es who are within

the bargaining unit and the department for filling bargaining

unit vacancies. If the Company is unable to fill the vacancy

through either employees in the bargaining unit or department,

the vacancy is posted for company-w:: de bidding. No preference

is given to an employee who is not in the bargaining unit in

which a vacancy occurs.

47. The record further reflects that under both the Local

223 agreements, an employee bidding from outside the bargain

ing unit or the department, should he be successful, is unable

to carry with him any of the seniority he might have accumulated

in his former job for purposes of both future promotions and

bidding on vacancies in which the occupational group bargaining

unit. His competitive status is lower than chat of employees

who are junior to him in the Company's service but who are

nevertheless senior in the occupational group and/or bargaining

f

unit or department seniority. Both Local 17 and Local 223 agree

ments with Detroit Edison Company do not protect the rate of an

9employee who is transferring to a high opportunity job is a new

bargain! 'g unit which has a rate lower than the job from which

he is transferring. Accordingly, such an employee may suffer a

reduction in economic benefits under this system, which pro

vides for complete loss of seniority and pay reduction for

black employees assigned to low opportunity jobs. Such blacks

arc being discouraged from applying for high opportv ity jobs.

Moreover, in many instances such black employees do not even

have the opportunity to bid.

48. Seniority as defined in the collective bargaining

agreement between Local 223 Utility Workers Union of America

and Detroit Edison Company is once again occupational group

seniority for the purpose of layoff, rehidng, promotions and

transfers between bargaining unit- covered by the agreement.

Promotions to vacancies within an occupational group within

the bargaining unit are awarded on the basis of occupational

group seniority. In less than 10 percent of the bidding situ

ations a junior employee is chosen over a senior employee.

Under the Local 17 agreement, the junior employee is success

ful in even fewer instances. The posting provisions of the

collective bargaining agreements between Local 223 and Detroit

Edison Company provide the vacancies within a bargaining unit

which are not filled by an employee within the occupational

group itself in which the vacancy occurs shall first be posted

in the bargaining unit where the vacancy exists. When a va

cancy is not filled through employees in the bargaining unit

it may be posted in other bargaining units in the same depart

ment and, at that point, the measure of seniority considered

is Company service. If vacancies are not filled through this

- 3G -

procedure the vacancy ir. pouted companywide. This procedure

makes it unlikely that blacks, who have been and are dispro

portionately assigned to lower opportunity jobs, will ever

have the opportunity to bid for high opportunity jobs under

either the Local 223 or Local 17 contract.

49. It was repealed at trial thdt under the Local 223

agreement those blacks in low opportunity jobs who are for

tunate enough to have the opportunity to transfer must sacri

fice seniority credits previously accumulated as well as their

wage rate if the entry level in f: high opportunity department

pays less than the job which they hold. In most instances

blacks in low opportunity jobs do not have the chance to trans

fer to high opportunity jobs because of the bidding and post

ings listed above. Seniority loss and wage reduction discourage

transfers for those few blacks who obtain the chance to apply

for transfers. Supervisors, more than 99 percent of whom are

white, must sign a transfer bid before blacks can attempt to

transfer from a low to a high opportunity job.'

50. Defendant Detroit Edison Company claims that it

follows a policy of promotion from within. Yet its collective

bargaining agreements make unlikely or impossible promotion

from within of blacks who continue to be disproportionately

assigned to low opportunity jobs and v/ho are either completely

exc1 ided from or have taken responsibility in the high opportun

ity jobs described above. Rather than promote blacks from within

- 3 7

ski1led tradesmenthe Company, Detroit Edison sometimes hires

from Canada who cannot even speak English. Additionally, Detroit.

Edison deliberate]/ recruits blacks with poor employment records,

When it has on its payroll blacks with gc d employment records

who cannot obtain promotion and transfer because of the inten

tional and unintentional discrimination on account of race.

51. Defendant Utility Workers Union, Local 223, has misin

formed black members by advising such members that unsuccessful

bids involving jobs outside their departments cannot be put

through the grievance procedure under the collective bargaining

agreement. Black employees have been discouraged from filing

grievances and have not sought to use the grievance procedure

to obtain relief from discrimination because of their lack of

confidence in defendants local 223 and Detroit Edison Company.

Local 223 has insisted upon strict adherence to seniority for

black meter readers consigned by that system to undesirable

routes when seniority had not been followed uniformally for

i.white meter readers before blacks were hired. Defendant Local

223, Utility Workers Union of America and Detroit Edison Company

have delibcrately gerrymandered seniority districts so as to

deny black union members promotional opportunities in the better

i

paying jobs. Defendant Local 223 has negotiated and acquiesced

in discriminatory seniority, bidding and posting procedures

*which have the effect of locking blacks into low opportunity

jobs. Defendant Local 223 apparently has never protested Detroit

- 30 -

Edison Company's hiring or promotional policies with the Company

itself, before any administrative agency — federal or state; or

before any court.

52. The president of Local 223 was th only member of the

Utility Worker's Executive Committee to vote against the establish

merit of a human rights committee for that Union. The Loca- presi

dent, Pete Johnson, has insisted upon rerun elections only for

blacl officials of Local 223. Johnson and Local 223 have

attempted to exclude blacks from leadership positions and Local

223 has failed to take action to discourage the hostility and

threats of white members from -Local 223 made against black

members of Local 223.

53. Defendant Local 17 IBEW has negotiated seniority and

posting provisions in its collective agreement which have the

effect of locking blacks into low opportunity jobs. Defendant

Local 17 has never protested Detroit Edison Company's hiring or

promotion policies with the Company itself; before an administra

tive agency - - federal or state; or before any court. Defendant

Local 17 refers workers to defendant Detroit Edison Company and

thus directly aides and abets Edison's discriminatory hiring.

G. Deficiencies of 7- ffirmative Action Prog ran.

54. Detroit Edison Company's ; ffirmative action program

involves a sporadic and occasional effort to publicize job

opportunities in the black community in the Metropolitan

Detroit Area and is therefore inadequate. The Detroit Ed'son

Company has never made use of l̂ lack radio stations to adver

tise employment opportunities at Detroit Edi on Conpuny; in

fact, the Company lias done nothing at all which has produced

fruitful results. Defendant Detroit Edison has at various

times rejected the suggestions of the plaintiff Stamps and

other employees that the Company establish a training program,

if blacks were indeed unqualified and that a special coordinator

be assigned to deal with problems of black employees.

V, Discussion of Applicabl.e Lav;.

The courts have recognized that racial discrimination in

employment is class or group discrimination. See, e.g., Jenkins

v. United G->s Corp. 400 F. 2d 28 (5th Cir. lf 5C) ; Otis v. Crov. .

Zellerbach 398 F. 2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968); Blue Dell Boots v.

EEOC 410 F. 2d 355 (6th Cir. 1969). It is Title VII of the 1964

Civil Rights Act which provides the broadest legislative mandate

for eliminating racially discriminatory practices in emp>loymcnt.

Courts have frequerbly relied on statistics in the employment

discrimination area because of the difficulty involved in establish

ing unlawful action in connection with a wide variety of individual

acts where both records and witnesses may not be available after '

a substanti 1 period of time and where the employe r or union lias

primary or exclusive access to the relevant information. See,

e.g., Mabin v. T.cnj. Siwgl or, Inc. 457 F. 2d 806 (uth Cir. 1972) .

Tlie principle that "the prepondc ranee of Negroes in lower-paying

and inferior jobs, while white workers have the better work,

4 0

for Title VII violationought to establish a primn facie case

has now Iwen accepted in connection with promotion as well as

hiring by most of the U. S. Circuit Courts of Appeal. Gould,

"Seniority and the Black Worker," 47 Texas L. Rev. 1039 (1969).

There is virtur 1 unanimity on the proposition that the statis- .ical

absence of blade., disproportionate to whites makes out a Title

VII and Civil Rights Act of 1866 violation. Se<s for instance,

Mabln v. Lear Stegler, Ire., supra; United States v„ St. Louis-

San Francisco Ry., 454 F. 2d 301, 307 (8th Cir. 1972) cer.

denied 93 S. Ct. 913 (1973); Brown v, Gaston County Dyeing Mach.

Co. 457 F. 2d 1377, 1382 (4th Cir. 1972); United States v, Hayes

International Corp. 456 F. 2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972); United Spates

v. Ironworkers Local 86 443 F. 2d 544, 550 (9th Cir.), cert,

denied 404 U.S. 984 (1971); Jones v . Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc.

431 F. 2d 245, 247 (10th Cir. 1970) cert, denied 401 U. S. 954

(1971); IJ. S. v, Chosaocake & Olio Ry. Co. 5 FEP Cases 311 (4th

Cir. 1972).

Sign:' ficantly, the United States Court of Appeals for the

Eighth Circuit has gone further than the above-cited cases, stat

ing in Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co. 433 F. 2 421

(8th Cir. 1970) as follows:

"We hold as a matter of law that these statistics,

which reveal that an extraordinarily sir 11 number

of black employees, except for the most part as

menial laborers, established a violation of Title

VII . . . " Id. at 426.

Parham, then, concludes that statistics showing "an extraordinar

ily" small number of blticks proves a violation rather than merely

establishing a prima facie case. Even when statistics are not

- 41 -

tal;on to conelurvivcly establish discrimination - - though the

percentage of black workers may be extremely small - - they

should be given proper effect, by the court when valid, and

should be weighed by the court together with the testimony of

witnesses. See Jonn: v. Leo Way Motor Freight, Inc., supra at

247. In Jones, a case that differs frgin the instant case in

which statistics have been buttressed by witnesses' testimony,

the court set forth the following language:

"True, no specific instances of discrimination

have been shown. However, because of ne histor- •

ically all-white makeup of the Company's line

driver category, it well may be that Negroes

simply did not lather to apply." Id. at 247.

The Court in Jones, therefore, seemed to conclude that

"statistics establish a prima facie case even in the absence of

the kind of testimony which in the a’ sen e of the kind of testi

mony which is in the record in the instant case. Id. at 247.

Also pertine; is United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Interna

tional Local Union 36, 415 F. 2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969), where the

court, once again finding violation where tire record was "void

of sp ;if ic instances of discrimination" sub: quent to July 2,

1965, the effective date of Title VII, stated that

"The Act, in our view, permits the use, of evidence

of statistical probability to infer the existence

of a pattern of practices of discrimination,," Id.

at 127, n . 7.

Statistics in this case establishing prima facie.discrimina

tion demonstrate the following: (1) a severely disproportionate

and small number oL blacks k the labor market area; (2) a

severely disproportionate and small number of blacks employed in

4 2

V

Edison high opportunity jobs an deparLmonts; (3) the. number

and percentage of blacks hired declined subsequent to the intro

duction of tlie race identification system in the 1'950's; (4) a

higher percentage of black applicants continue to be unrated as

compared to white applicants.

The statistics indicate that prima facie violations were

made out with regard to defendants not only in the past but in

the present as well. Unlike Parham, for instance, whore present

discrimination could not be found because of the substantial im

provement in the company's hiring patterns, in this case present

as well as past discrimination is made out on the basis of sta

tistics. This is dramatically demonstrated not only by the con

tinued absence of blacks from professional, supervisory and skilled

trades jobs, but also by Government's exhibit 65 which indicates

that employees hired during the years 1963 and 1970 into the high