Tison v. Arizona Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Tison v. Arizona Brief for Petitioners, 1985. 644e7247-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aff0483f-dca3-4379-bfca-e56050c0c812/tison-v-arizona-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

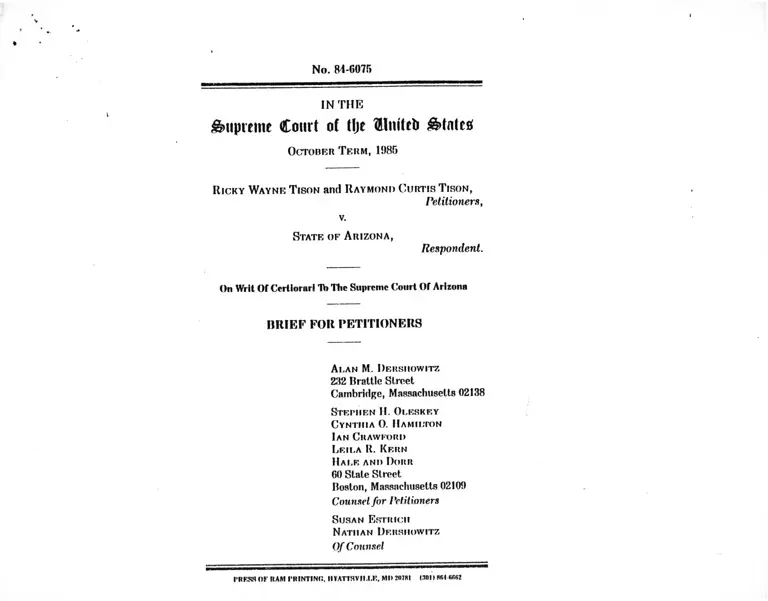

N o. 84-6075

IN T H E

Supreme Court of tlje ftlmteb &tntetf

October Term, 1985

Ricky Wayne T ison and Raymond Curtis T ison,

Petitioners,

v.

State of Arizona,

Respondent.

On Writ Of Certiorari Tb The Supreme Court Of Arizona

B R IE F F O R P E T IT IO N E R S

Alan M. Deusiiowitz

232 Brattle Street

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138

Stephen H. Oleskey

Cynthia O. Hamilton

Ian Crawford

Leila R. Kern

Hale and Dorr

60 State Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02109

Counsel fo r Petitioners

Susan Estricii

Nathan Deusiiowitz

Of Counsel

PRESS OF nAM I’UINTINC. IIVATTSVII.I.F, MO 20781 CHID 8fil M«2

I

%

i •

• K V L l J

)

i

(•

’>;i

f.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Is the December 4, 1984, decision of the Arizona

Supreme Court to execute these petitioners in conflict with the

holdings of this Court where, in words of that court, petitioners

“did not specifically intend that the [victims] die, . . . did not

plot in advance that these homicides would take place, or . . .

did not actually pull the triggers on the guns which inflicted the

fatal wounds,. . . ” but where that court fashioned an expanded

definition of “ intent to kill" to include any situation where a

non-triggerman "intended, contemplated or anticipated that

lethal force would or might be used or that life would or might

be taken in accomplishing the underlying felony”?

\

t a b l e o f c o n t e n t s

Page

Question Presented..........................................

Tahle of Authorities........................................ ■,1

Opinions Below.................................................

Jurisdiction..................................................... *

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions

Involved.................................................... 1

Statement of the Case ..................................... 2

Summary of the Argument............................... 14

Argument........................................................ 15

I. The Execution of Raymond and Ricky Tison

Would Violate The Eighth Amendment and

This Court’s Decision I n Enmund v. Florida 15

A. Enmund v. Florida Requires Reversal ........ 16

B. The Arizona Supreme Court Violated Enmund

in Defining Intent as Foresight of a Possibility 20

II. The Execution of Raymond and Ricky Tison

Would Violate The Eighth Amendment and

This Court's Decision in Godfrey v. Georgia 31

A. A Comparison Between the Circumstances in

Godfrey and in the Instant Case Establishes

That There Is "N o Principled Way to Dis

tinguish This Case, in Which the Death Penalty

Was Imposed, from the Many Cases in Which It

Was Not” And Thus Establishes That The Ari

zona Court Did Not Apply A Constitutional

Construction Tb Its Death Penalty Statute .. 31

B. The Aggravating Factors Relied on by the A ri

zona Courts Were A t Least as Standardless,

Unchanneled and Uncontrolled as the Ones

Unconstitutionally Relied on in Godfrey..... 38

Conclusion....................................................... 43

Statutory Appendix.......................................... la

ii

iii

TA B LE O F AU TH O R IT IE S

Page

Acker v. Slate, 26 Ariz. 372, 226 P. 199 (1924)........... 19 n.22

Cabana v. Bullock,____ U .S .-------, 106 S.Ct. 689

(1986)..................................................................... passim

Carlos v. Superior Court, 35 Cal. 3d 131, 197 Cal. Rptr.

79, 672 P.2d 862 (1983).......................................... 26 n.30

Chaney v. Brown, 730 F.2d 1334 (10th Cir.), cert, denied,

____ U.S______ , 105 S.Ct. 601 (1984)................,. 26 n.29

Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584 (1977)................................ 30

Enmund v. State, 399 So.2d 1362(1981), rev'd., 458 U.S.

782(1982)........................................................ 16, 16 n. 18

Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982)................... passim

Fisher v. United States, 328 U.S. 463, reh. denied, 329

U.S. 818(1946).......................................................... 29

Fleming v. Kemp, 748 F.2d 1435 (11th Cir. 1984) reh.

denied, 765 F.2d 1123 (U th Cir. 1985), cert, denied,

____ U.S______ , 106 S.Ct. 12S6 (1986)................. 26 n.29

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, reh. denied, 409 U.S.

902(1972)................................................................ 28,32

Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420 (1980).................... passim

Greenawalt v. Ricketts, No. 84-2752 (9th Cir. March 20,

1986)..................................................................... 35 n.39

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976).......................... 29, 32

Hatch v. State, 662 P.2d 1377 (Okla. Corn. App. 1983),

reh., 701 P.2d 1039 (Okla. Crim. App. 1985), cert..

denied____ U.S______ , 106 S.Ct. 834 (19861 • • • 26 n.30

Hyman v. Aiken, 777 F.2d 938 (4th Cir. 1985)........... 26 n.29

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586 (1978).............. 20, 22, 23 n.25

Mullaney v. Wilbur, 421 U.S. 684 (1975)......................... 29

Nyc & Nissen v. United States, 336 U.S. 613 (1949). 24 n.25

People v. Aaron, 409 Mich. 672, 299 N.W.2d 304

(1980)..................................................................... 24 n.25

People v. Dillon, 34 Cal. 3d 441, 194 Cal. Rptr. 390, 668

P.2d 697 (1983)............ 27 n.30

People v. Garcia, 36 Cal. 3d 539, 205 Cal. Rptr. 265, 684

P.2d 826 (1984), cert, denied, ____ U.S. ____ , 105

S.Ct. 1229(1985)................................................... 26 n.30

People v. Garcwal, 173 Cal. App. 3d 285, 218 Cal. Rptr.

690(1985).............................................................. 26 n.30

iv

Thble of Authorities Continued

i Page

People v. Jones, 94 Ill.2d 276, 447 N.E.2d 161 (1982), cert.

denied, 464 U.S. 920 (1983).................................. 27 n.30

People v. Tiller, 94 Ill.2d 303, 447 N.E.2d 174 (1982), cert.

denied, 461 U.S. 944 (1983).................................. 27 n.30

Reddix v. Thigpen, 728 F.2d 705 (5th Cir.), reh. denied,

732 F.2d 494 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,----- U.S-------- ,

105 S.Ct. 397 (198-1)............................................. 26n.29

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962)................... 29

Sander si Miller v. Logan, 710 F.2d 645 (10th Cir.

1983)................ ................................................... 19 n.22

Slate v. Bishop, 144 Ariz. 521, 698 P.2d 1240 (1985).. 27 n.32

State v. Bracy, 145 Ariz. 520, 703 P.2d 464 (1985), cert.

denied, 1___U.S______ , 106 S.Ct. 898 (1986).... 27 n.32

State v. Emery, 141 Ariz. 549, 688 P.2d 175 (1984)... 27 n.31

State v. Fisher, 141 Ariz. 227, 686 P.2d 750, cert, denied,

____U.S_______105 S.Ct. 548 (1984)..................... 28 n.32

State v. Gillies, 135 Ariz. 500, 662 P.2d 1007 (1983), cert.

denied,____ U.S______ , 105 S.Ct. 1775 (1984)... 28 n.32

Slate v. Greenawalt, 128 Ariz. 150, 624 P.2d 828, cert,

denied, 454 U.S. 882 (1981), rev'd. sub nom, Green

awalt v. Ricketts, No. 84-2752 (9th Cir. March 20,

1986).................................................................... 10 n.15

State v. Greenawalt, 128 Ariz. 388, 626 P.2d 118, cert,

denied, sub nom, Tison v. Arizona, 454 U.S. 848

(1981)............................................................. 2 n.l, 7 n.9

Slate v. Harding, 141 Ariz. 492, 687 P.2d 1247 (1984) 28 n.32

State v. Hoojwr, 145 Ariz. 538, 703 P.2d 482, cert, denied,

____U.S______ , 106 S.Ct. 834 (1986)............. 27-28 n.32

State v. James, 141 Ariz. 141, 685 P.2d 1293, cert, denied,

____U.S_______ 105 S.Ct. 398 (1984).................... 28 n.32

State v. Jonlan, 137 Ariz. 504 , 672 P.2d 169 (1983)... 28 n.32

Stale v. Libberton, 141 Ariz. 132, 685 P.2d 1284

(1984) ................................................................. 28 n.32

State v. Martinez-Villareal, 145 Ariz. 441, 702 P.2d 670,

cert, denied,____ U.S. 106 S.Ct. 339

(1985) ................................................................. 28 n.32

State v. McDaniel, 136 Ariz. 188, 665 P.2d 70

0983)...................................................... 20 n.23, 27 n.31

State v. Peterson, 335 S. E.2d 800 (S.C. 1985)........... 26 n.30

v

Ihhle o f Authorities Continued

Page

State v. Poland, 144 Ariz. 388,698 P.2d 183, cert, granted,

____ U.S______ , 106 S.Ct. 60 (1985)...........'........ 28 n.32

State v. Richmond, 136 Ariz. 312, 666 P.2d 57, cert.

denied, 464 U.S. 986 (1983).................................. 28 n.32

State v. Smith, 138 Ariz. 79, 673 P2d 17 (1983), cert.

denied, 465 U.S. 1074 (1984)............................... 28 n.32

State v. (Raymond Curtis) Tison, 129 Ariz. 546, 633 P.2d

355 (1981), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 882, reh. denied,

459 U.S. 1024(1982)............................................. 1

State v. (Raymond Curtis) Tison, 142 Ariz. 454, 690 P.2d

755 (1984), cert, granted, ____ U .S. ____ , 54

U.S.L.W. 3561 (1986)............................................... 1

State v. (Ricky Wayne) Tison, 129 Ariz. 526, 633 P.2d 335

(1981), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 882, reh. denied, 459

U.S. 1024 (1982)......................................................... 1

State v. (Ricky Wayne) Tison, 142 Ariz. 446, 690 P.2d 747

(1984), cert, granted,____ U .S ._____ , 54 U.S.L.W.

3561(1986).................................................................. 1

State v. Tison, CR. 108352 (Maricopa County).............. 3 n.3

State v. Villafuente, 142 Ariz. 323, 690 P.2d 42 (1984), cert.

denied, _ _ U.S_____ , 105 S.Ct. 1234 (1985)... 28 n.32

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910)................. 29

Constitutional Provisions:

U.S. Constitution amendment V I I I ................... 1, 15, 30, 31

U.S. Constitution amendment X IV ................................ 2, 31

Statutes:

Ala. Code §§ 13A-6-3, 13A-5-6 (1975, 1981 Supp.).. . . 24 n.26

Ariz. Rev. Slat. Ann. §§13-139, 13-140, 13-451, 13-452,

13-453, 13-454 (1956, Repealed 1978)............... 2, 18, 40

Ark. Stat. Ann. §§41-1504, 41-901 (1947, 1985 Supp.) 24 n.26

Conn. (Jen. Slat. Ann. §§53a-56a, 53a-35a (1958)___ 24 n.26

Ga. Code § 27-2534.1(b)(7) (1978).................................... 38

Hawaii Rev. Stat. §§707-701, 707-702, 706-660(1976,1984

Supp.)...................................................... 24 n.26, 24 n.27

111. Ann. Slat. ch. 38 §§9-3, 1005-8-1 (1979, 1982 and 1985

Supp.).................................................................... 24 n.26

Ind. Code Ann. §§35-42-1-5, 35-50-2-6 (1978)........... 24 n.26

VI

Thble of Authorities Continued

i Tage

Kan. Stat. Ann. §§21-3404, 21-4501 (1981, 1985

Supp.)................................................................... 24 n.2fi

Kv Rev. Stat. §§507.020, 507.040, 532.000

(1985)..................................................... 24 n.26, 24 n.27

Miss. Ann. Code §§99-19-101(7) (1985 Supp.).......... 24 n.27

Mo. Ann. Stat. §§505.024, 558.011 (1979 and 1980

Supp.)................................................................... 24 n.2G

Nev. Rev. Stat. 200.033(4) (1983)................. 24 n.2G, 24 n.27

N H. Rev. Stat. Ann. §630:1-B (1979 and

1983 Supp.)............................................................ 24 n.27

N.J. Stat. Ann. §§2c:ll-4, 2c:43 6 (1982)................... 24 n.2G

N.D. Cent. Code §§ 12.1-10-02, 12.1-32-01 (1985).... 24 n.26

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §§ 2903.01,2903.04 (1982 and Supp.)

.................................................................................... 24 n.27

Or. Rev. Stat. §§ 163.125, 161.605 (1983)................... 24 n.26

Pa. Stat. Ann. tit. 18, §§2504, 1104 (1983)................. 24 n.26

S.D. Codified Laws Ann. 22-16-20, 22-6-1 (1979 and 1984

Supp.)................................................................... 24 n.26

U'x. Penal Code Ann. §§ 19.05, 12.34 (1974)............ 24 n.26

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §§9A.32.060, 9A.20.021 (1977 and

1986 Supp.)............................................................ 24 n.2G

Wis. Stat. Ann. §§940.06, 939.50(1982)..................... 24 n.26

Other Authorities

ALI Model Penal §210 Code and

Commentaries............. 17, 19, 20 n.22, 22 n.25, 23 n.26

Corpus Juris Secundum, Criminal Law §§ 87, 88---- 19 n.22

Corpus Juris Secundum, Homicide § 9(d)................... 19 n.22

Roth and Sundby, “The Felony-Murder Rule: A Doctrine

at Constitutional Crossroads,” 70 Cornell L.Rev. 446

(1985)..................................................................... 24 n.27

OPINION BELOW

The opinions of the Supreme Court of Arizona denying post

conviction relief and affirming petitioners’ convictions of felony

murder and sentences of death are reported in Stale v. Ricky

Wayne Tison, 142 Ariz. 446, 690 P.2d 747 (1984) (J.A. 302-79)

ami State v. Raymond Curtis Tison, 142 Ariz. 454,690 P.2d 755

(1984) (J.A. 344-61). The opinions of the Supreme Court of

Arizona originally affirming petitioners’ convictions of felony

murder and sentences of death are reported in State v. Ricky

Wayne Tison, 129 Ariz. 526, 633 P.2d 335 (1981), cert, denied,

459 U.S. 882, reh. denied, 459 U.S. 1024 (1982) (J.A. 309-43)

and State v. Raymond Curtis Tison, 129 Ariz. 546,633 P.2d 355

(1981) , cert, denied, 459 U.S. 882, reh. denied, 459 U.S. 1024

(1982) (J.A. 290-308).

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this Court rests upon 28 U.S.C. § 1257(3),

the petitioners having asserted below and asserting here a

deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution of the United

States.

The original judgments of the Supreme Court of Arizona

affirming the petitioners’ convictions and sentences were

entered on July 9, 1981. Timely petitions for rehearing were

denied by the Supreme Court of Arizona on September 10,

1981. The Arizona Supreme Court denied post-conviction

relief on October 18, 1984. Timely petitions for reconsideration

were denied by the Arizona Supreme Court on December 4,

1984. The joint petition for certiorari was filed on January 16,

1985 and granted on February 24, 1986. ----- U.S. -------, 54

U.S.L.W. 3561 (U.S.).

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED

This case also involves the Eighth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States, which provides:

Excessive bail shall not be required nor excessive fines

imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishment inflicted. . . .

2

and the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States, which provides, in pertinent part:

No State shall make or enforce anv law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of the citizens of the United

Slates; nor shall any State deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property without due process of law; nor deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of

the laws.

This case also involves the following provisions of the stat

utes of the Slate of Arizona, which are set forth in the Stat

utory Appendix to this brief: Ariz Code of 19.19,43-116, in part,

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-139 (1956) (Repealed 1978); Laws of

1912, Ch. 35, §25, Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-140 (1956)

(Repealed 1978); Ariz. Code of 1.939, 43-2901, Ariz. Rev. Stat.

Ann. § 13-451 (1956) (Repealed 1978); Ariz. Code of 1939,

43-2902, Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-452 (Supp. 1957-1978)

(Amended 1973) (Repealed 1978); Ariz. Code of 1939, 43-2903,

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-453 (Supp. 1957-1978) (Amended

1973) (Repealed 1978); Laws of 1973, Ch. 138, §5, Ariz. Rev.

Stat. Ann. § 13-454 (Supp. 1957-1978) (Repealed 1978). These

statutes were in effect at the time of the crimes for which the

petitioners stand convicted. The statutes were then repealed

and replaced when Arizona revised its criminal code, effective

October 1, 1978.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioners Ricky and Raymond Tison were sentenced to

death for killings they neither committed nor specifically

intended. Ricky and Raymond were convicted of breaking their

father Gary Tison and his jailmate Randy Greenawalt out of

prison.1 They were 18 and 19 years old at the time of the

'In a separate trial from those in which they received the death penalty,

Ricky and Raymond Tison were both convicted in Pinal County, the site of the

prison, of aiding and assisting in an esca|>e, assault, possession of a stolen

vehicle, and unlawful (light from a law enforcement vehicle. They received

concurrent sentences of 30 years to life for each of the assaults, and sentences

of four to five years for each of the other offenses, to be served concurrently

with each other but consecutively to the assault sentences. Stale v. Green-

nwalt, 123 Ariz. 388,026 P.2d 118,121, cert. den. tub nom.. Titan v. Arizona,

•151 U S. 818 (1081). Throughout this litigation. Petitioners have raised

3

breakout. Neither had any prior felony convictions.2 They

lived at home with their mother and older brother Donald, and

visited their father nearly every week during his eleven-year

imprisonment preceding the breakout. (Transcript of March

14, 1979 at 103, 105-06, 110, 112, 124.) During those eleven

years, Gary Tison was a model prisoner who ran the prison

newspaper and assisted the prison administration in quieting a

riot and strike in 1977. (Transcript of March 14,1979 at 127-32,

137-38.)

Despite his excellent prison record, Gary Tison was refused

parole. (Tr. March 14,1979 at 140.) He planned an escape, with

the help of his brother Joseph, his three sons, their mother and

other relatives.3 According to the psychologist appointed by

the sentencing court to evaluate petitioners prior to sentenc

ing, “there was a family obsession, the boys were ‘trained’ to

think of their father as an innocent person being victimized

. . .” (See, infra, n.16).4 Originally it wad not intended for the

three sons to participate in the breakout (J. A. 50, J. A. 91), but

eventually they decided to become involved after receiving an

assurance from their father that no shots would be fired.5 And

indeed no shots were fired during the breakout. (J.A. 291)

numerous constitutional challenges to their convictions as well as their death

sentences. Without waiving any of the other issues— some of which require

development of the record through habeas corpus— they sought certiorari at

this stage on the constitutionality of the death penalty for defendants who

neither killed nor intended to kill.

zTheir only prior brush with the law was a misdemeanor charge of petty

theft for taking a case of beer, fur which they were required to clean up 6 miles

of highway. (J.A. 233-34)

aGaryb brother Joseph obtained the automobile and some guns used in the

escape. (J.A. 50-52, J.A. 91) Dorothy Tison, Gary’s wife and the boys’ mother,

was subsequently charged in connection with the escape, pleaded nolo eon-

tendre to a charge of conspiracy to assist in the escape and served nine

months in prison. State, v. Titan, Cr. No. 108352 (Maricopa County).

<The report continued that "both boys have made perfectly clear that they

were functioning of their own volition [but) at a deeper psychological level it

may have been less of their own volition than as a result of Mr. Tison’s

‘conditioning’ and the rather amoral attitude within the family home” See,

infra, n.10.

"■’Raymond Tison slated prior to his sentencing, "Well, I just think you

should know when we first came into this we had an agreement with my dad

4

Two days later, the car that was used for the escap e-*

, ^ n -ix o e r ien ced a second flat tire, thus incapacitating it.

i 'nA 3 (T l A 311) A decision was made to try to flag down a

(J. A 130, J. • h ape.6The car that was stopped— a

Mazda^onta^ned^he^Lyons family, consisting of a husband, a

" fe , toby and a niece named Theresa Tyson (no relatmn to

petitioners.), (/d.)

Both automobiles were driven down a dirt mad off the high

way (J.A. 131) The family was then placed by the ,̂de of t

road and the Tison^ possessions were placed in the Mazda.

{,d v Z Lincoln was then driven 50 to 75 yards further n o

the desert (Id ) T>» ensure that the family would not be able to

Ltacoin and aiert the authorities, Gary further mca-

pacited the Lincoln by firing into the car’s radiator (J. A. 39

J.A. 131) Those were the first shots that were fired during the

entire episode.

The father, Gary Tison, then told his sons to go back to the

Mazda and fetch a jug of water for the Lyons family. (J A. ,

i a 131) This combination of actions— further disabli g

Lincoln and sending hia sons to fetch water for the Lyons

family-was plainly intended to communicate to Ricky, Ray

mond, and Donnie the reassurance that the Lyons family would

not be killed. If there had been a plan to kill them, there would

have been no need to waste ammunition in further mcapacitat-

inr *1)0 car or to waste water on people who were going to be

n i.-icd. The sentencing court itself found that, " I t was not

essential to the defendants’ continuing evasion of arrest that

these persons were murdered.” (J.A. 283) Thus the very

“senselessness" of the killings made them unpredictable to

Ricky and Raymond. (J.A. 283)

While in the process of fetching the jug of water, the Tison

brothers were shocked to hear the sounds and see the flashes of

that nobody wouhl get hurt because we [the brothers) MiaHte.l no one hurt^"

(J.A. 359) There is nothin* in the reconl which in any way contradicts t

statement. . .

. . wanting to signal somebody down. Hag somebody down amltake

their vehicle."(J.A. 35) “And then he IGary Tisnnl came up with a plan you

know, just take another car . . ." (J.A. 52)

gunshots in the dark night as their father and Randy Green-

awalt opened fire and shot the Lyons family. (J.A. 75, J.A. 131)7

Either their father had changed his mind at the last minute

without telling his sons, or he had deliberately misled them

into believing that the Lyons would be left alive with water in

the incapacitated Lincoln.8 1

1 As Justices Feldman and Gordon pointed out in their dissenting opinion,

the only evidence in the record relating to the state of mind of the sons was the

following statement by Raymond:

Well I just think you should know when we first came into this we had an

agreement with my dad that nobody would get hurt because we I the

brothers] wanted no one hurt. And when this |kjllmg of the kidnap

victims) came about we were not expecting it. And it took us by surprise

as much as it took the family [the victims) by surprise because we were

not expecting this to happen. And I feel bad about it happening. I wish

we could lhave done) something to stop it, but by the lime it happened it

wns too late to stop it. And it’s just something we are going to live with

the rest of our lives. It will always be there.

(J.A. 377; ellipses from opinion.)

There is no ambiguity in the record about the fact that the father, Gary

Tison, shot into the radiator of the Lincoln “to make sure it wasn't going to

run " (J.A. 108) Nor is there any ambiguity about the fact that Gary Tison

specifically told his sons to "get a jug of water for these people"— the Lyons

family. (J.A. 75, J.A. 109) Neither is there any ambiguity about the Tact that

all of the shooting was done by Gary Tison and Randy Greenawalt. (J.A.

112-13) The only ambiguity in the record is precisely how close the Tison sons

were to the Lincoln when Gary Tison and Randy Greenawalt suddenly began

to shoot into it. Raymond recalled being at the Mazda filling the water jug

“when we started hearing the shots." (J.A. 21) Ricky believed that they were

“headed toward the Lincoln to give it [the waterl to the Lyons family when

the tragic events began: the father took the jug and he and Randy Greenawalt

“went behind the Lincoln, spoke briefly, raised their shotguns and started

firing." (J.A. 41, J.A. 112) It is impossible to determine whose recollection

was more precise and no real effort was made to do so at the trial, since

nothing turned on the physical proximity of the sons to the killers as they

fired their shots. There is nothing in the record to contradict the statements

of both sons that the shooting was sudden and unexpected and that they were

not in a position to prevent it. Nor is there anything in those portions of the

record cited by the Stale in its Rcs|>onse to Joint Petition for Writs of

Certiorari ( “State’s Response") that contradicts the fundamental reality that

Ricky and Raymond did not kill, plan the killings, or intend that the victims

die. (Slate’s Response at I I . )

The State argued that petitioners and their father “began planning the

escape a couple of years before it actually happened. (States Response at 1.)

This assertion misleadingly summarizes Ricky Tisons statement. Ricky

stated that he and his brother had had "thoughts" about his fathers getting

out of prison for years, but had become involved in the actual escape plan only

a week tiefore the escape. (Exhibit 1 to State’s Response at 8.) Furthermore,

6

It was for these murders— which were neither committed by

Raymond or Ricky Tison nor specifically intended or planned

. “rmmle of years" before the escape, Raymond and Ricky would have been at

15 and 16 years old, respectively, and hardly in a position to plan a prison

& when Gary Tison killed a prison guard in 1M7. Raymond

and Rickv were eight and nine years old, respectively. (J.A. 223, J.A. 263).

Their lack of comprehension of the significance of the event at the time was

comDounded by their experience with their father during the ensuing eleven

.ini-ini' which time he was a model prisoner and maintained a close

E n ” wu!: hi, t o i l , . See. i,„ra. „ I6 , „ l TV. Mareh U . 1OT. .1

132-33

Additionally the Stale claimed “While it has never been proved that either

petitioner fired any of the fatal shots, the evidence suggests that Ricky

Tisonk weapon was used to fire two rounds near the Lincoln (Exhibits 5 and

6)" (State’s Response at 7.) That the State even mentions this point demon

strates how weak its position is with res|>ect to petitioners’ culpability.

Exhibits 5 and 6 to the Stateb Response only indicate (a) tw o. 45 caliber shells

were found near the Lincoln, and (b) at one time Ricky Tison had bought a .45

caliber gun. There is no evidence as to when the gun was fired (no bullets

were ever found), what the gun was used for, or who fired it. There is no basis

for the State to insinuate that Ricky Tison had any personul involvement in

the killings and. indeed, the prosecution, the sentencing judge and the

Arizona Supreme Court have all specifically held to the contrary. A t Ricky s

trial, the prosecutor argued that “ He was an aider anti abettor. He conspired

with the persons who did the murders." (J.A. 152) And at Raymonds trial,

the prosecutor acknowledged that “ those other persons killed somebody

(J.A. 191) The sentencing judge found as a mitigating circumstance

that he was “convicted of four murders under the felony murder instruc

tions ■ (J.A. 285) The Arizona Supreme Court has acknowledged on two

separate occasions that there is no evidence that he participated in the

killings. (J.A. 341, J.A. 364)The state’s apparent inference to the contrary at

this stage of the case is simply not credible and should be given no further

consideration by this Court.

The State also points to a statement by Ricky that he heard his father tell

the Lyons that he (the father) was “thinking about” killing them. But the

record is clear that it was after this that the father decided to send his sons to

get the jug of water, thus telling Ricky in effect that he (the father) had

decided not to kill them.

Finally, the Arizona Supreme Court cited a hypothetical statement made

by Raymond in the presentence report to the effect that he would have killed

in a very close situation. This is how the court characterized Raymonds

statement:

. . . he later said that during the escape he would have been willing

personally to kill in a “ very close life or death situation, and that he

recognized that after the escape there was a |iossibility of killings.

(J.A. 346) This is the actual statement from the presentence report:

When I asked the defendant if he ever thought when they were

planning the break out at the prison, if someone might possddy get kdled

in prison, lie stated, that they had informed their father that was one

7

by them— that Raymond and Ricky Tison were sentenced to

the penalty of death.

Several days after Gary Tison and Randy Greenawalt killed

the Lyons family, the group was apprehended at a roadblock

near Casa Grande, Arizona.9 The oldest brother, Donnie Tison,

was shot in the head during the apprehension and died from his

injuries. Ricky, Raymond and Randy Greenawalt were

condition that they would have to go by, that no one gel hurt. I then

explained to him that entering a prison with loaded weapons was a pretty

“gutty* thing to do. He stated, JWe had no intention to shoot anybody.”

He then continued by stating, “Who ever said those guns were loaded.” I

then pointedly asked him, ‘‘Were they, Raymond?" He said, “Well, yes

tliey were, in case something happened." Tnis Officer asked, “ Raymond

could you have shot somebody if the whole deal had gone sour?" He

asked, “A t the Prison." And I said. “Yes.” He said, “ It would have hud to

have been a very close life or death situation. I could not cold-bloodedly

killed someone, no. Still 1 think I would have had some hesitation about

killing anybody, I just never really thought of it." He continued by

stating, “7b kill all those people at the prison would have been a senseless

killing, that is something I did not want. I asked him, “Well when it

started out why did you think you needed weapons?" He stated, “Just

strictly psychological."

(J.A. 248) It is clear from the context that the dominant message was that he

“had no intention to shoot anybody," that he would have had some “hesitation

about killing anybody," and that he “just never really thought of it.” In any

event, there is no suggestion anywhere in the record that either petitioner

ever contemplated the cold blooded killing of an innocent family.

The dissenting Justices evaluated the record and arrived at the following

conclusions:

'llie only evidence on the issue indicates that before the killings both of

the Tison brothers had been sent back to the victims’ car by their father

and were some distance away from the actual place at which the killings

occurred. (Statements of Ricky Tison, 1/26/79 at 13 and 2/1/79 at 35;

Statements of Raymond T7son, 1/26/79 at 18 and 2/1/79 at 42). There is

neither a finding from the trial court nor evidence to establish that

defendant was in a |>osition to prevent the killing, if he had wanted to.

There is evidence that although defendant was “worried" about his

fatherb intentions toward the kidnap victims, he did not know what was

going to happen until, from the other car some distance away, he and his

brother presumably heard the first shot, turned and saw the killings.

(Statements of Ricky Tison, 1/26/79 at 9 and 13; Statement of Raymond,

1/26/79 at 18).

(J.A. 356, J.A. 374). Nothing in the majority opinion specifically disputes any

of these record facts.

,JOn August 10, 1978, Gary Tison, Randy Greenawalt, Donnie Tison, au<|

petitioners were apprehended at a roadblock near Casa Grande, Arizona.

Randy Greenawalt and petitioners were arrested and incarcerated. They

were tried together and convicted in Pinal County for their part in the prison

breakout. Slate v. (ireenawall, 128 Ariz. 388, 626 P.2d 118, cert, denial snb

num, IHson v. Arizona, 454 II.S. 848 (1981).

8

» .i r,arv Tison, the father, initially escaped, but was

found two weeks later dead of exposure in the desert. (J. A. 819,

J.A. 321)

The three surviving defendants were tried together for

crimes committed .luring the breakout. They were convicte,

ami sentenced to long prison terms.'” Each was then tried

separately for the four murders, convicted and sentenced to

death.

Prior to sentencing, the judge issued an order appointing Dr

James A MacDonald, a clinical psychologist, to interview, test

and evaluate the defendants." A fter a battery of tests and

extended interviews with the boys and their mother, Dr. M c

Donald concluded that "these two youngsters . . . were

obsessed with their father’s release,” that “ their father, Gary

Tison exerted a strong, consistent, destructive but subtle

pressure upon these youngsters,” and that “ these young men

Z committed to an act which waa eaaenttally W them

heads.’ Once committed,” he continued, “ it was too'late. .

(see, infra, n.16)12 Dr. MacDonald concluded that these

youngsters have a capacity for rehabilitation and he recom

mended a “structured and controlled setting. (See, infra,

n. 16.)

The Chief Adult Probation Officer, after an extensive review

of the entire record, concluded that “ this defendant did not

actively participate in the murder of the Lyons family and

Theresa Tyson, except to drive them to the scene. (J.A.

He was “tom between recommending the maximum or lighter

sentence” and so he made no recommendation. (J.A. 252, J.A.

269)

'"See, infra, n.l.

"Dr. MacDonald waa not appointed as a defenae expert but rather as a

court expert.

,2l)r. MacDonald also concluded that there “does not appear to be any true

defense based on brainwashing, mental deficiency, mental illness or irre

sistable urge," but that "at a deeper psychological leve it may have been le..

of their own volition than as a result of Mr. Tison’s ‘conditioning and the

rather amoral attitudes within the family home. See. m/m, n.lh.

9

Even though neither of the professional evaluators recom

mended the death penalty, the trial judge imposed it on these

two young men. He found three aggravating factors and three

mitigating factors. The aggravating factors were: 1) that the

"persons among the defendants who fired the fatal shots fired

indiscriminately and excessively" and thus “knowingly created

a grave risk to other persons in addition to” John Lyons and

Donnelda Lyons,13 2) that the defendants committed the

offenses for "pecuniary” reasons, namely to take the car; and 3)

that the actual killers murdered their victims in “an especially

heinous, cruel and depraved manner,” based on "the sense

lessness of the murders,” since it “was not essential to the

defendants’ continuing evasion of arrest that these persons

were murdered.” (J.A. 281-83; emphasis added.)

Thus, only the second aggravating factor— pecuniary

motive— related to these petitioners, who did not themselves

kill the victims.14 The first and third factors related specifically

to the actual triggermen, who themselves chose the manner

and extent of the shootings. Indeed, the sentencing judge used

the same language in describing the aggravating factors found

against the Tison brothers— who neither killed, planned to kill,

nor specifically intended that the victims die— as he used in

finding these same three aggravating factors against Randy

Greenawalt, who deliberately murdered the victims. (J.A.

281-a i)15

,nThe sentencing court’s theory was apparently that Cary Tison and Randy

Greenawalt intended to murder only John Lyons and Donnelda Lyons and

that they created a risk to the other two people they also murdered.

"E ven the “pecuniary” factor hardly seems to fit the actions and motives of

the petitioners. Their crime was motivated by an obsession to break their

father out of prison and be reunited with him, rather than by pecuniary

considerations. Stealing a car was not part of the original plan, and resulted

from the unanticipated flat tires during the escape. (J.A. 311)

ir.The Court found that the following aggravating circumstances applied to

Randy Greenawalt:

“3. In the commission of the murders of John Lyons and Donnelda

Lyons, the defendant knowingly created a grave risk of death to other

persons in addition to those victims. The person or persons among the

defendants who fired the fatal shots fired indiscriminately and exces

sively as evidenced by the number of spent shotgun shell casings found in

the immediate vicinity of the Lincoln and the number of fatal wounds

sustained by John Lyons and Donnelda Lyons. The location of the fatal

10

The three mitigating factors found by the sentencing court

were-1) the youth,of the petitioners; 2) the absence of any prior

- 1 record- and 3) the fact that they were convicted of

murder under a felony murder instruction which did not

require a finding of intent. (J. A. 285)

hj -n,e defendant committed the offenses as.consideration for the

• , ; .1 „ pxnectation of the receipt of something of pecuniary

X ! n l c l y f c UkinB »t the .alomobSe and »lh er Pr » l * r t , o ( the

virfims John and Donnelda Lynns. . „

sgsspssi

conclusion is inescapable that ail me vicums Med by the

d fcV sm u l th7m\nnerinThichthe victimsi werekilled. w j

the equivalent to the severest physical torture.

"This finding is also based on the senselessness of the murders It was

not essential lo the defendant’s continuing escape and evasion

that these nenions be murdered. The victims could have easily been

restrained sufficiently to permit the defendant £

liefore the robberies, the kidnappings, and the lhc^ ^ |(\e'7 „e „ „ con-

in snv event the killing of Christopher Lyons, who could nose no con

ceivaJle threat to the ifefendant. by itself com|»els the conclusion that

was committed in a depraved manner. _ ,

Tr. of March 2fi, 1979, at 11-11-44, Stale v. Greemmll. 128 An*, m . 621 . <

828, red. denied. 454 U.S. 882 (1981). rev’d tub nomGreenawaU v. «.cfceCs

No. 84-2752 (9th Cir. March 20, 198(5); compare this language to J. A. 281-tw.

The Court found as additional aggravating factors that Greenawalt ha<

been previously convicted of mtinler and armed ro > >ery. c . a

n

On direct appeal, the Arizona Supreme Court reversed the

finding of the first aggravating factor relied on by the sentenc

ing judge, concluding that the evidence did not support the

hypothesis that the defendants who fired the shots deliberately

created a grave risk to others. (J. A. 303) It affirmed the pecuni

ary finding and the finding that the shootings were committed

in an "especially heinous, cruel, or depraved manner." (J.A.

301) It rejected petitioners’ argument that there were other

mitigating factors in addition to the three found by the sentenc

ing judge. (J.A. 305) Among the mitigating factors not found by

the sentencing judge and raised on appeal, was petitioners’

claim that the “psychological reports on his mother and himself

establishes the strong, manipulative influence [their] father,

Gary Tison, had on [them].” (J.A. 339) The Arizona Supreme

Court concluded that “the report does not support this argu

ment” (J.A. 339), though a fair reading of the entire report—

which is reproduced in footnote 16 below— demonstrably does

support petitioners’ contention that (in the words of the report

itself) “their father, Gary Tison, exerted a strong, consistent,

destructive but subtle pressure upon these youngsters” and

that “ these young men got committed to an act which was

essentially ‘over their heads.’ ” Although such pressure might

not constitute a "true defense,” it surely cannot be ignored— as

it was by the lower courts— as a mitigating factor in a life or

death decision.,fi

"The full text of Dr. MacDonald’s report to the sentencing court, which

was part of the record on appeal, i3 as follows:

Dear Judge McBryde,

Enclosed please find three copies of the documents pertaining to the

Tison boys as set forth in your order of January 10, 1979.

This included a lengthy social history taken by Mrs. Tison, review of

school and hospital records, approximately 1 to 5 hours spent with each

boy ami a foil and extensive psychological battery.

These young men represented a considerable diagnostic challenge and

due to the nature of the case I proceeded slowly and attempted to work

the entire psychological battery through a most cautious and careful

manner.

H ie bottom line appears to be that these are two youngsters who were

obsessed with their father's release but the obsession can not be consid

ered an irresistahie impulse. There is no sign of psychosis or mental

defect other than the mild antisocial personalities. Iliese most unfortu

nate youngsters were born into an extremely pathological family and

12

On direct appeal prior to this Court's decision in Enmnnd v.

Florida 458 U.S. 782 (1982), petitioners also argued that— in

the court’s own words— "the imposition of the sentence of death

upon an individual convicted under a felony murder theory

without evidence that he was the actual perpetrator of the

homicide or intended that the victim should die is grossly

disproportionate and violates the prohibition against cruel and

unusual punishment contained in the Eighth Amendment of

the United States Constitution.” (J. A . 293-294) The court

decided that issue adversely to both petitioners, concluding as I

were exposed to one of the premier sociopaths of recent Arizona history.

In mv opinion this very fact had a severe influence upon the personality

structure of these youngsters, coupled with the cold, long suffering

martyr-type personality of Mrs. tison. Under other circumstances

these youngsters may have been referred to the in vemle court for bicycle

heft.mischief, e tc , and would have never become invovcd in the

horrendous criminal events which followed the escape in July of 1978.

The question of rehabilitation and their potential for rehabilitation

looms large. 1 do not pretend to know legal processes and/or legal

possibilities but I do believe, over time, that these youngs ers have a

capacity for rehabilitation if placed in a structured and controlled set-

tine Due to their youth, their naivity, their basic immaturity, poor

judgment and lack or common sense these youngsters are easily led and

easily manipulated. I f at all possible it would be in their best interest to

segregate them in any prison setting, if possible, from older, more

hardcore prisoners. Ricky, in particular, is probably susceptible to sex

ual assault as it appears from the vast amount of testing accomplished

that Ricky is experiencing some significant psyehosexual dilliculties and

in my opinion could lie “used" sexually by unscrupulous prisoners Due

to the youth and the lack of sophistication on the part of boh these boys I

would urge that some consideration be given to the conditions ol their

incarceration.

I do believe that their father, Gary Tison, exerted n strong consistent,

destructive but subtle pressure upon these youngsters and 1 believe that

these young men got committed to an act which was essentially over

their heads." Once committed, it was too late and there does not appear

to be any true defense based on brainwashing, mental deficiency, mental

illness or irresistable urge. There was a family obsession, the boys were

“trained” to think of their father as an innocent person being victim zed

in the state prison but both youngsters have made perfectly clear that

they were functioning of their own volition. At a deeper psychological

level it may have been less of their own volition than as a result of Mr.

Tison’s “conditioning” and the rather amoral attitudes within the family

home.

Thank you Tor your attention to this note and I certainly appreciated

the opportunity to work with these interesting ami extremely ehallcng-

ing young men and I am grateful for the opportunity to be of service to

the Superior Court.

Sincerely yours,

James A. MacDonald, Ph.D.

13

follows: “That they did not specifically intend that the Lyons

and Theresa Tyson die, that they did not plot in advance that

these homicides would take place, or that they did not actually

pull the triggers on the guns which inflicted the fatal wounds is

of little significance.” (J.A. 340-341)

The record in this case compels a conclusion even stronger

than that petitioners did not specifically intend that the victims

die; the uncontradicted record evidence establishes that Ray

mond and Ricky Tison affirmatively intended and affirmatively

believed that no one would be killed, and that they were taken

by complete surprise when their father either changed his

mind suddenly or tricked his sons into believing that the Lyons

would be left alive with water in the incapacitated car.

Following this Court’s decision in Enviund v. Florida,

supra, the Arizona Supreme Court, on collateral review, reite

rated its original conclusion that “ the evidence does not show

that petitioner^] killed or attempted to kill.” (J.A. 345, J.A.

364) Nor did it make any findings inconsistent with its original

conclusion that petitioners “did not specifically intend that the

[victimsl die. . . . ” (J.A. 340) However, the court then fash

ioned a new and expanded legal definition of "intent” designed

to fit the facts of this case: “[IIntended to kill includes the

situation in which the defendant intended, contemplated, or

anticipated that lethal force would or might be used or that life

would or might be taken in accomplishing the underlying fel

ony." (J.A. 345, J.A. 363; emphasis added.) The court then

held— by a 3 to 2 vote— that the evidence established beyond a

reasonable doubt that petitioners “ intended to kill,” within its

new definition, and that they could thus be executed under

Enmnnd.

Justice Feldman and Vice Chief Justice Gordon, in a strongly

worded dissent, argued “ Even if we ignore the previous con

trary conclusion, today’s holding is remarkable because there is

no direct evidence that either of the brothers intended to kill,

actually participated in the killing or was aware that lethal

force would be used against the kidnap victims." (J.A. 353, J.A.

371) Even the State has admitted that “A t no time has [the

14

Arizona Supreme! Court held that either petitioner actually

killed any of the four victims or that either petitioner planned

any of the killings. . . . The original conclusion that petitioners

harbored no specific intent to kill remains unchanged.” (State’s

Response at 11.) Thus, Ricky and Raymond Tison stand sen

tenced to die despite the agreement by all concerned that these

young men, with no prior felony records, neither killed,

attempted or planned to kill, nor specifically intended that

death occur.17

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The instant case is factually indistinguishable from Entnund

v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982). In an effort to avoid the

governing effect of that authority, the Arizona Supreme Court

fashioned an expanded new definition of the "intent to kill”

required for a non-killer defendant to be subject to the death

penalty. Under this new definition, a non-killer who neither

planned nor specifically intended that the victims die, is eligi

ble for execution if he "intended, contemplated or anticipated

that the lethal force would or might be used or that life would or

might be taken. . . .” (J.A. 345; emphasis added.)

This definition— which attempts “ to apply the tort doctrine

of foreseeability to capital punishment in order to satisfy the

Enmund criteria” (J.A. 376)— is so broad, vague and open-

minded that it would dramatically expand the category of those

eligible for execution so as to include many (like petitioners)

who are far less personally culpable than many who are not

sentenced to die. Because judges and juries will continue to

impose the death penalty only “rarely” on “ one vicariously

guilty of the murder” ( Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. at 800),

the disparity will increase between those sentenced to death

and those not sentenced to death for crimes which are indis

tinguishable in principle.

The Arizona Supreme Court’s decision thus violates the

holdings of Enmund, Godfrey and other governing decisions.

,7For a listing of the other mitigating factors— not considered by the lower

courts—see, infra, at 111-15.

15

If allowed to stand, it would permit the execution of two young

men, with no prior felony records, whose personal culpability

is indistinguishable in principle from that of Enmund and God

frey. These young men, who were "trained” to believe their

father was innocent, “got committed to an act which was essen

tially 'over their heads,’ ” and agreed to help older family mem

bers break their father out of prison only after their father—

who “exerted a strong, constant, destructive but subtle pres

sure upon these youngsters”— promised them that no one

would be hurt. Moments before the shootings, they were affir

matively led to believe, by the words and actions of their father,

that the occupants of the disabled car would be left alive with a

jug of water. They were surprised at the sudden decision of

their father and his jailmate to shoot the victims, and they

could do nothing to stop it.

No one in the recent history of this country has ever been

executed where the personal aggravating factors have been so

few and weak and the mitigating factors so many and strong.

Petitioners’ sentences of death violate the Eighth Amendment

and should be reversed.

ARGUMENT

I. THE EXECUTION OF RAYMOND AND RICKY TISON

WOUIJ) VIOLATE THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT AND

THIS COURT’S DECISION IN ENMUND V. FLORIDA.

In Enmund v. Flonda, this Court imposed a substantive

constitutional limitation on the states’ power to impose the

death penalty in cases where the defendant "neither took life,

attempted to take life, nor intended to take life.” 458 U.S. 782,

787 (1982). It held that the Eighth Amendment to the United

States Constitution prohibits the imposition of the death

penalty on an armed robber who did not himself either kill or

personally intend that a killing take place. Neither the fact that

armed robbery is a serious or dangerous crime, nor the fact

that under Florida law Enmund was guilty of capital murder,

allowed the stale, in imposing the death penalty, to ignore the

difference in culpability between Enmund and those who actu

ally and intentionally killed.

If)

This case is plainly controlled by Enmund. Here, as in

Enmund, the defendants did not themselves kill. Here, as in

Enmund, the prosecution’s case was tried under a the<>ry 0

vicarious liability for felony murder. Here, as in Enmund. ihe

state supreme court itself concluded that the petitioners did

not specifically intend that the [victims] die . . . did not plot in

advance that these homicides would take place, or . . . did inot

actually pull the triggers on the guns which inflicted the fatal

wounds. . . ” (J. A. 340-41) Here, as in Enmund, the judgment

upholding the death penalty must be reversed.

A. Enmund v. Florida Requires Reversal.

Earl Enmund was convicted of the felony murder of an

innocent family which was the victim of an armed robbery. The

evidence in that case established that Enmund was stationed in

a nearby car, waiting to help the killer escape. A fter the

convictions were obtained, the trial court found four statutory

aggravating circumstances regarding the petitioners involve

ment,*8 and no mitigating circumstances, emphasizing that

Enmund’s participation in the murder had been major in that

he “planned the capital felony and actively participated in an

attempt to avoid detection by disusing of the murder weap

ons.” Enmund v. Slate, 399 So.2d at 1373 (1981), rev d 458

U.S. 782 (1982). On appeal, the Florida Supreme Court held

that the jury could have plainly inferred from the evidence that

"Enmund was there, a few hundred feet away, waiting to help

the robbers escape,” and that this was sufficient to find the

petitioner to be constructively present and a principal in the

murders under state law. Id.

It was in these circumstances that this Court held that the

death penalty could not constitutionally be imposed. This

Court’s opinion comprehensively surveyed "society s rejection

of the death penalty for accomplice liability in felony murders,

noting that most legislatures, judges, and juries have generally

'«On appeal, two of the aggravating circumstances were rejected by the

Florida Supreme Court, while the finding of no mitigating circumstances was

affirmed. Enmund v. State, 399 So.2d I3fi2. 1373 (1981), revd. 438 U.S. 782

(1982).

17

rejected the imposition of the death penalty for individuals like

Earl Enmund and Raymond and Ricky Tison. **' The Court

then reached that same conclusion as a “categorical rule” of the

Eighth Amendment. Cabana v. Bullock,____ U .S ._____ , 106

S.Ct. 689, 697 (1986). ’Hie Court recognized the fundamental

precept that “causing harm intentionally must be punished

more severely than causing the same harm unintentionally,”

and held that the state had violated the United States Constitu

tion in treating alike both Enmund and those who killed and in

attributing to Enmund the culpability of those who killed.

Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. at 798. "For purposes of Impos

ing the death penalty,” this Court concluded, "Enmund’s crimi

nal culpability must be limited to his participation in the

robbery, and his punishment must be tailored to his personal

responsibility and moral guilt.” Id. at 801.

The imposition of the death penalty on Raymond and Ricky

Tison would plainly violate that constitutional mandate. Ray

mond and Ricky were admittedly convicted of participating in

serious crimes which sometimes pose a risk to human life. But

so was Earl Enmund: it is precisely because armed robbery

presents a risk to human life that it is punished more severely

than unarmed robbery, and included in those felony murder

statutes which, like the A L I Model Penal Code, are limited to

inherently dangerous felonies. See, A L I Model Penal Code

§210 and Commentaries. And, again like Earl Enmund, Ray

mond and Ricky were convicted and punished based not on

proof that they themselves intended death, but rather based on

the superimposition of legal constructs one upon the other:

“The interaction of the ‘felony-murder rule and the law of

principals [or vicarious liability] combine to make a felon gener

ally responsible for the lethal acts of his co-felon.’ " Enmund v.

Florida, 458 U.S. at 787.

Tlie jury instructions in this case leave no doubt that the

convictions required no finding of the intent to kill necessary

for the imposition of the death penalty under Enmund, and the

'"See Enmund v. Florida. 158 U.S. at 789-96 (Court's description and

analysis of the data).

18

record of these cases would have precluded any such finding. In

both cases, the jury was charged that aiders and abettors,

"though not present,” as well as conspirators, are responsible

as principals for the commission of an offense (J. A. 177-79, J. A.

216-19), and that “a murder committed in avoiding a lawful

arrest or effecting an illegal escape from legal custody or in

perpetration of or an attempt to perpetrate robbery or kidnap

ping is murder of the first degree whether willful and premedi

tated or accidental." (J.A. 180, J.A. 220). Thus the prosecutor

was able to argue that if petitioners aided or abetted in the

prison escape, they were guilty of the Lyons’ murders even

though they neither pulled the trigger nor caused the killings

in any way.20 In fact, the prosecutor argued at Kicky’s trial that

“(t)here is tlo requirement that the defendant caused the k ill

ings’’ (J.A. 173; emphasis added) and at Raymond’s trial that “ in

this case we have a situation where the defendant is a conspir

ator with other persons and those other persotis killed some

body during these offenses, during a robbery, kidnap, avoiding

or preventing lawful arrest, or escape” (J.A. 191; emphasis

added). See J.A. 133-36, J.A. 185, J.A. 208-9. Once Ricky and

Raymond Tison were convicted of first degree murder under

the combined action of Arizona’s vicarious responsibility and

felony murder rules, they became eligible for the death penalty

despite their lack of personal involvement in the murders

themselves. See Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. §§ 13-452, 13-453, Stat

utory Appendix at la-2a.

Indeed, if anything, the facts of this case present stronger

grounds for reversal of the death penalty than Enmund itself.

In Enmund, reversal was mandatory because the record did

not affirmatively establish Enmund’s intent to kill. Here by

contrast, the record includes substantial evidence that the

hoys affirmatively intended that no one he killed, and that they

were either misled by their father, or that he suddenly changed

his mind. In Enmund, the court not only found that the peti

tioner actively participated in the planning and concealing of

^’Indeed. under this instruction and the reasoning of the courts below,

petitioners’ mother could have received the death penalty for her role in the

escape, a role for which she served nine months in jail. See, supra, n.,1.

19

the crime, but that he was a convicted prior felon with a

pecuniary interest in the robbery. See Enmund v. Florida, 458

U.S. at 785. Here, by contrast, we are faced with two teenage

boys, with no felony records, with the natural ties and affection

boys feel for their father.21 Indeed, the State itself conceded, in

opposing review in this Court, that the Arizona Supreme Court

has agreed “that petitioners harbored no specific intent to kill,”

but continued to argue, erroneously, that the distinction was

not constitutionally significant. (States Response at 11.)

In upholding these convictions on direct review, the Arizona

Supreme Court reached precisely the conclusion that this

Court reversed in Enmund: “that they did not specifically

intend that the [victimsl die, that they did not plot in advance

that these homicides would take place, or that they did not

actually pull the triggers on the guns which inflicted the fatal

wounds. . . . ” (J.A. 340-41) But it found these facts to be “of

little significance.” (J.A. 341) The absence of specific intent,

that is, a showing of a “conscious purpose" to cause death, may

well be “of little significance” in Arizona for purposes of defin

ing the crime of felony-murder. Enmund does not limit the

state of Arizona’s freedom to classify as murder, accessorial

conduct which lacks specific intent to kill.22 But what is of little 2 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

2,See, supra, n.16.

“ Federal cases are unanimous in requiring a community of unlawful pur

pose at the time the deadly act leas committed. See generally. Corpus Juris

Secundum, Criminal I,aw §§87, 88, and Homicide §9(d), and cases cited

therein. Where a particular intent is an element of the felony it is essential

that one anting and abetting the commission of such offense should have been

aware of the existence of such intent in the mind of the actual perpetrator of

the felony. See, e.g., Sanders!Miller v. Logan, 710 F.2d (kl5 (10th Cir. 1983)

and cases cited therein; Acker v. Slate, 20 Ariz. 372, 220 P. 199 (192-1) ( “A

crime in which intent is an element cannot be aided innocently"). In Sondersl

Miller, the court held that to find one guilty of murder for aiding and abetting

one must prove the accused acted with “ full knowledge of the intent of the

persons who commit the offense." Significantly, and quite correctly, the court

cites this Court's opinion in Enmund as support for this very proposition.

Enmn nd supports this proposition in that it mandates a finding of a conscious

purpose to cause death on the part of the non-triggerman. This is equivalent

to asserting that a non-triggerman must share the intent of the actual killer at

the moment of the killing.

The A L I Model Penal Code Commentary, in describing accomplice lia

bility, is unequivocal on this point. The term “accomplice" only applies when

20

significance for liability is, under Enmund, constitutionally

determinative of whether the most extreme penalty of death

can be imposed. See, Cabana v. Bullock, 100 S.Ct. at 696;

Lockett v. Ohio, 4.38 U.S. 586, 602 (1978) ("That States have

authority to make aiders and abettors equally responsible, as a

matter of law, with principals, or to enact felony-murder stat

utes is beyond constitutional challenge. But the definition of

crimes generally has not been thought automatically to dictate

what should be the proper penalty.” )

In recognizing that Raymond and Ricky did not “specifically

intend" to kill, the Arizona Supreme Court reached the only

conclusion that is or could be supported by this record.23 That

conclusion, under Enmund, mandates reversal of their death

sentences.

B. The Arizona Supreme Court Violated Enmund In

Defining Intent As Foresight Of A Possibility.

In an effort to avoid the clear application of Enmund, the

Arizona Supreme Court, on review of petitioners’ habeas

application, read the intent requirement of Enmund to mean * I

the participants are accomplices in the offense for which guilt is in question.

As the Commentary notes:

(T)he inquiry is not the broad one as to whether the defendant is or is

not, in general, an accomplice of another or a co-conspirator; rather, it is

the much more pointed question of whether the requisites for accomplice

liability are met for the particular crime sought to be charged to the

defendant. (Commentary at 306)

Given such a limited inquiry, Section 2.06(e)(a) mnndates that the accused

have the purpose of promoting or facilitating the commission of the particular

crime for which they are being punished. See Commentary at 311. Enmund,

in its explicit mandate that a “conscious purpose" to cause death be shown,

harmonizes perfectly with these provisions of the A L I Mode! Penal Code.

zThe Arizona Supreme Court has held that the intent required by the

Enmund standard must be found beyond a reasonable doubt, Slnte v.

McDaniel, 130 Ariz. 188, 199; 065 P.2d. 70, 81 (1983), and it purported to find

in this case that the “evidence docs demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt

I that petitioners! intended to kill." (J.A. 345, J. A. 363) The application of this

most stringent of factual standards to the record here makes it clear how

permissive a legal standard the court was applying. There is simply no basis

in this record for concluding beyond a reasonable doubt that Petitioners

intended or contemplated that life would be taken as those concepts were

used in Enmund.

21

no more than a broad tort based understanding of intentional

action. Having already held that the boys did not specifically

intend to kill, did not plan or plot the homicides, and did not

themselves kill, a divided Arizona Supreme Court held that

they might nonetheless be executed under Enmund. The

“ intent to kill” required by Enmund, the Arizona Court

decreed, means no more than that the defendant be in a situa

tion in which he can be found to anticipate “that lethal force

would or might be used or that life would or might be tAken in

accomplishing the underlying felony.” (J.A. 345, J.A. 363) In so

broadly construing intent to kill, the Arizona Supreme Court

plainly violated this Court’s holding and reasoning in Enmund

itself.24

Arizona’s interpretation totally eviscerates the Enmund

standard. It constructs a test of "intent" which would allow the

execution of virtually every individual ever convicted of any

vicarious felony murder— including Earl Enmund himself. For

the reality is that any felony involving a dangerous weapon

presents some risk that lethal force might be used and that

human life might then be taken. I f that were not so, the

underlying felony would not have been made a predicate for the

felony-murder rule. And it was the purpose of Enmund pre

cisely to distinguish— as a matter of constitutional law—

between those actors in a felony-murder-accessorial-liability

case who may be executed and those who may not.

In Enmund, this Court concluded:

Enmund did not kill or intend to kill and thus his

culpability is plainly different from that of the robbers who

killed; yet the State treated them alike and attributed to

Enmund the culpability of those who killed the Kerseys.

This was impermissible under the Eighth Amendment.

458 U.S. at 798. 21

21Cabana v. Bullock, 106 S.Ct. 089 (1980), makes clear that the Arizona

Supreme Court is authorized to make the factual determination of intent

required by Enmund. Rut it does not permit the state court to define the

“ intent” required by Enmand according to state common law principles. The

"intent" required by Enmund is an issue of federal constitutional law, man

dated by the eighth amendment, and the error here came not in who made the

findings of fact, hut in how they defined the constitutional standard.

24

The Constitution may not bar Arizona from choosing to

classify as felony murder what most states would consider

reckless homicide.?7 But it does prohibit the imposition of

death for such risk-taking activity. As this Court recognized

most recently in Cabana v. Bullock, “the principles of propor- * 21

reasoning. The Commentary condemns the use of mere probabilities as a sole

mlicator of culpability. Tb do so, the Commentary notes, would amount to

tunishing an accomplice for negligence while maintaining a higher standard

ror the principal who actually perpetrated the crime. In the words of the

•ommentators:

The culnability reiiuired to be shown of the principal actor, of course, Is

normally higher than negligence. . . . 7b say that the accomplice is

liable if the tffense committed is “reasonably foreseeable" or the ̂ proba

ble. consequence" of another crime is to make him liable fo r negligence,

even though more is remitted in order to convict the principal actor. This

is both incongrous and unjust; if anything, the culpability level for the

accomplice should he higher Ilian that of the principal actor. . . ."(Com

mentary, p. 312, n.42, emphasis added.)

>>* Nye & Nissan v. United States, 33(5 U.S. 613, 619 (19-19); see e g., Ala.

■ode 55I3A-6-3, I3A-5-6 (1975 A Supp. 1981); Ark. Stat. Ann. 1141-1504,

H 901 (1947 A Supp. 1985); Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. 5553a 56a, 53a-35a (West

958); Hawaii Rev.Stat. 55707-702, 706-660 (1976 A Supp. 1984), III. Ann

Uat. Ch. 38 559-3 (1979), 1005-8-1 (1982 A Supp 1985); 1ml. Code Ann.

•535-42-1-5, 35-50-2-6 (Hums 1978); Kan. Stat. Ann. 5521-3404. 21-4501

1981 A Supp. 1985); Ky. Rev. Stat. 55507.040,532.060(1985); Mo. Ann. Stat.

5565.024, 558-011 (Vernon 1979 A Supp 1986); N.J. Stat. Ann. 552c; 11-4,

V: 43 6 (West 1982); N.D. Cent. Code 55 12.1-16-02, 12.1-32 01 0985); Or.

tev. Stat. 55163.125, 161.605 (1983); Pa. Stat. Ann. tit. 18, 552504, 1104

l*urdon 1983); S.D. Codified Laws Ann. 22-16-20,22-6-1 (1979 A Supp. 1984)-

bx. Penal Code Ann. 55 19.05, 12.34 (Vernon 1974); Wash. Rev. Code Ann

59A.32.060. 9A.20.021 (1977 A Supp 1986); Wis. Stat. Ann. 55940 06

39.50 (West 1982).

21A number of states have abolished the felony murder rule. Kentucky and

lawaii abolished the nile hy statute. Hawaii Rev. Stat. 55707-701 (1976 A

984 Supp); Ky. Rev. Stat. 5607.020 (1985). Ohio has effectively reclassified

•lony murder as involuntary manslaughter. Ohio Rev. Code Annot.

$2903 01, 2903.04 (1982 A 1985 Supp.) Michigan has eliminated the rule by

ichcial decison. People v. Aaron, 409 Mich. 672, 299 N.W.2d 304 (1980).

dditionally, New Hampshire has adopted a rebuttable presumption ofreck-

ssness and Indifference under the nde, thereby constricting its reach N II

;ev. Stat. Ann. 5630; l-R (1976 A 1983 Supp). See, Roth and Sun.lby, The

dotty Murder Rule: A Doctrine at Constitutional Crossroads, 70 Cornell

Rev. 446, 446-7 (1985). Ib is Court in Enmund noted that only eight

msdictmns imposed the death penalty, at that time, solely for participating

i a robbery in which another roblier kills. 458 U.S. at 789. Of the eight

insilictions so noted, four of them, after Enmund, no longer impose the

, " Penalty in those circumstances. See Miss. Ann. Code 599-19-101(7)

'i'PP 1985), Nev. Rev. Stat. 200.033(4) (1983), and the California and South

arolina cases cited in n.30, infra.

25

tionality embodied in the Eighth Amendment bar imposition of

the death penalty upon a class of persons who may nonetheless

be guilty of the crime of capital murder as defined by state law;

that is, the class of murderers who did not themselves kill,

attempt to kill, or intend to kill. 10G S.Ct. at G9G.

Tb define intent to kill so broadly as to encompass any risk

taking activity which might endanger life, as the Arizona

Supreme Court did, amounts to nothing less than violating-the

constitutional limits imposed by Enmund. Yet it was only

through such an evisceration of the Enmund test that a bare

majority of the Arizona Supreme Court could deem the peti

tioners to have “ intended” the deaths here and thus be eligible

for the death penalty in this case. For if intent to kill were

properly limited to its constitutionally mandated meaning,

there simply would be no basis in this record for the execution

of Raymond and Ricky Tison. The evidence is overwhelming

that they lacked any such intent; indeed, it seems clear that

their intent was that no one should die, and that their father

either affirmatively misled them to believe that he shared that

intent, or that he suddenly changed his mind after sending his

sons for the water jug.

The record is clear that Ricky and Raymond Tison had every

reason to believe that their father, a model prisoner since the

boys were small children, would not turn ruthless killer.28

First, during the breakout— a time most likely for violence to

occur— the boys found their father holding to his word that

killing would be avoided. No one was hurt and not a shot was

fired. Guards and visitors were merely placed in a storage

room, and Gary Tison, Randy Greenawalt, and Donnie, Ricky

and Raymond Tison walked into the parking lot, got into a car,

and drove off. Second, after the Mazda was flagged down and

the victims abducted, Gary Tison shot the radiator of the

Lincoln, disabling it in the middle of the desert. The victims

were placed in the Lincoln, as if to be left to their own devices.

I f the victims were to be shot, the operability of the Lincoln

would be irrelevant. Third, and directly buttressing this

*""|T|herc was a family obsession, the boys were 'trained’ to think of their

father as an innocent person. . . ." See, supra, n. 16.

26

inference, Gary Tison sent Ricky and Raymond “to go get some

water, get a jug of water for these people.” In light of these

facts, the execution of Ricky and Raymond can only be viewed

is the very sort of attribution of the father’s guilt to the sons

that Enmund squarely prohibits.

Arizona^ requirement as to the type and level of intent

necessary to satisfy Enmund is also at variance with the

majority of courts which have applied Enmund. Petitioners

are aware of no federal case allowing a death sentence to stand

solely on the basis that a defendant anticipated that lethal force

might be used or that lives might be taken.29 Similarly, sub

stantial authority exists in post-Enmund cases decided by

state courts that more than a possibility that lethal force might

be employed is necessary to justify execution.30

v>See Hyman v. Aiken, 777 F.2d 938, 940 (4th Cir. 1985) (death sentence

vacated because "It|he instruction allowed the jury to recommend a death

sentence for Hyman as an aider and abettor whether or not he killed,

attempted to kill, or intended to kill the robbery victim"); Chaney v. Brown,

730 F.2d 1334, 1356 n.29 (10th Cir.), cert, denied, 105 S.Ct. 601 (1984)

(“Before death penalty can be imposed it must be proven beyond a reasonable

■louht that |the defendant) killed or attempted to kill the victim, or himself

intended or contemplated that the victim’s life would be taken"); Fleming v.

Kemp, 718 F.2d 1435, 1452-56 (11th Cir. 1984) (jury had to have found

defendant guilty of malice murder to support dentil sentence under

Enmund), reh. denied, 765 F.2d 1123(11th Cir. 1985), cert, denied, 106 S.Ct.

1286 (1986); Reddix v. Thigpen. 728 F.2d 705, 708 (5th Cir.), reh. denied, 732

F.2,1 494 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 105 S.Ct. 397 (1984) ( “The eighth amend

ment, then, allows the state to impose the death penalty only if it first proves

that the defendant either participated directly in the killing or personally had

in intent to commit murder”).

'‘'People v. Garetval, 173 Cal. App. 3d 285, 218 Cal. Rptr. 690, 696 (1985)

(death penalty may be imposed “only if the aider and abettor shared the

peqietrator's intent to kill"); State v. Peterson, 335 S.E.2d 800, 802 (S.C.

(985) (“death penalty can not be imposed on an individual who aids and abets

in a crime in the course of which a murder is committed by others, but who did

not himself kill, attempt to kill, or intend that killing take place or that lethal

force be used"); People v. Garcia. 36 Cal.3d 539,557, 205 Cal. Rptr. 265, 275,

684 P.2d 826, 836 (1984), cerf. denied, 105 S.Ct. 1229 (1985) ("possible

inference of intent to aid a killing" not enough to satisfy Enmund and the