Wall v. Stanley County, North Carolina Board of Education Opinion

Public Court Documents

March 6, 1967 - May 19, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wall v. Stanley County, North Carolina Board of Education Opinion, 1967. e8a5e259-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b0006a0f-e219-4e71-a699-417d4284ef1d/wall-v-stanley-county-north-carolina-board-of-education-opinion. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

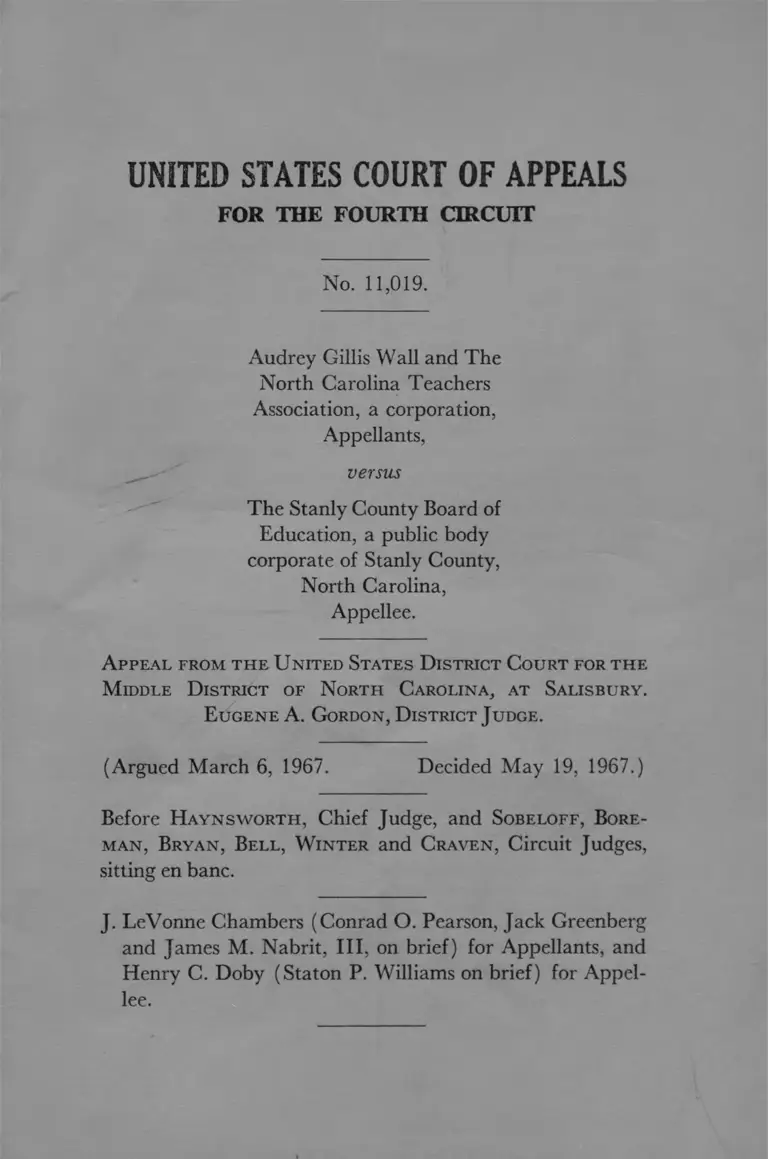

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 11,019.

Audrey Gillis Wall and The

North Carolina Teachers

Association, a corporation,

Appellants,

versus

The Stanly County Board of

Education, a public body

corporate of Stanly County,

North Carolina,

Appellee.

A ppeal from the U nited States District Court for the

M iddle District of North Carolina, at Salisbury.

Eugene A. Gordon, D istrict Judge.

(Argued March 6, 1967. Decided May 19, 1967.)

Before H aynsworth , Chief Judge, and Sobeloff, Bore-

m an , Bryan, Bell, W inter and Craven, Circuit Judges,

sitting en banc.

J. LeVonne Chambers (Conrad O. Pearson, Jack Greenberg

and James M. Nabrit, III, on brief) for Appellants, and

Henry C. Doby (Staton P. Williams on brief) for Appel

lee.

2

C r a v e n , Circuit Judge:

It is now firmly established in this circuit (1) that the

Fourteenth Amendment forbids the selection, retention, and

assignment of public school teachers on the basis of race;

(2) that reduction in the number of students and faculty in

a previously all-Negro school will not alone justify the dis

charge or failure to reemploy Negro teachers in a school

system; (3) that teachers displaced from formerly racially

homogeneous schools must be judged by definite objective

standards with all other teachers in the system for continued

employment; and (4) that a teacher wrongfully discharged

or denied reemployment in contravention of these principles

is, in addition to equitable remedies, entitled to an award of

actual damages.1

In derogation of these principles, the district court denied

relief to Negro school teacher Mrs. Audrey Wall. We reverse.

I .

The facts found by the district court are briefly stated2

below.

Audrey Gillis Wall, a Negro, is, in the words of the district

judge, a teacher of “ unchallenged professional and educa

tional qualifications, who has thirteen years of teaching ex

perience, predominantly in Stanly County,” North Caro

lina. She holds A.B. and M.S. degrees and, despite some de

1 Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ., 364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir.

1966); Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir. 1966); Wheeler v. Durham

City Bd of Educ., 363 F.2d 738 (4th Cir. 1966); Franklin v. County School Bd.,

360 F.2d 325 (4th Cir. 1966). Chambers, Johnson, and Franklin were authored

by Judge J. Spencer Bell, who would have written the opinion for the court in

this case but for his death on March 19, 1967.

2 For a more complete statement of findings, see Wall v. Stanly County Bd. of

Educ., 259 F. Supp. 238 (M .D .N .C. 1966).

3

ficiencies in performance, was recommended by her princi

pal for reemployment for the school year 1965-66. The

School Board approved the principal’s recommendation of

reemployment, contingent only upon the allocation of the

requisite teaching positions by the State.

Integration came to the Stanly County school system ten

years after Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), occurring with the transfer of two Negro pupils

from a Negro school to a formerly all-white school in the

school year 1964-65. The system at that time consisted of

seventeen public schools and some 7,000 students, of which

approximately fifteen percent were Negro.

For the year 1965-66 and prior thereto, there was com

plete segregation of white and Negro teachers, i.e., no Negro

teacher taught white pupils, and no white teacher taught

Negro pupils. The first break in teacher segregation occurred

in January 1966 when a Negro teacher was employed to

teach history in a mostly white school.

On or about June 5, 1965, the allocation of teacher spaces

for the school year 1965-66 was received from the North

Carolina Board of Education. For the first time such spaces

were granted to the Stanly County Board of Education with

out reference to race and without designation of the school

in which the spaces might be used by the Stanly County

Board. During the spring of 1965, the Board adopted a free

dom of choice plan of pupil enrollment, and as a result

thereof, over 300 Negro pupils who had formerly attended

all-Negro schools were assigned to formerly white schools

for the school year beginning September 1965.

As found by the district court, “ the shifts in pupil enroll

ment as result of the ‘freedom of choice plan’ resulted in a

decrease in the allocation of teacher spaces to the Negro

schools and an increase in the allocation of teacher spaces to

4

formerly white or predominantly white schools.” Despite

this, and again in the words of the district court, “ the Board

adopted no specific provisions to govern assignment of teach

ers who might be affected by the shifting of pupil enroll

ment. The Board did not solicit opinions from either teach

ers or principals as to what, if any, policy might or should be

adopted. Principals were not advised as to whether teachers

whose positions were affected by the aforesaid reduced al

lotments to Negro schools would be reassigned to another

school in the system. The Board did not advise the several

white principals that they could employ Negro teachers nor

Negro principals that they could hire white teachers.”

II.

The meaning of the foregoing is very plain. Obviously the

Board considered that transfer of Negro pupils from a Negro

school diminished the need for Negro teachers in the Negro

school, causing Mrs. Wall to lose her job. The premise of

such a proposition is that Mrs. Wall was not employed as a

teacher in the Stanly County school system but was em

ployed as a Negro teacher in a Negro school. Such a premise

is unlawful. It is repugnant to the Fourteenth Amendment,

which “ forbids discrimination on account of race by a public

school system with respect to employment of teachers.”

Franklin v. County School Bd., 360 F.2d 325, 327 (4th Cir.

1966), citing Bradley v. School B d 345 F.2d 310, 316 (4th

Cir.), rev’d on other grounds, 382 U.S. 103 (1965).

In his opinion, the district judge said: “ It is obvious that

if the teacher spaces at Lakeview had not been reduced,

Mrs. Wall would have been reemployed for the school year

1965-66.” His finding is fully supported by the evidence. It

requires reversal of the decision below because Mrs. Wall

was not allowed by the School Board to compete for a teach

5

ing position in the system on the basis of her merit and quali

fications as a teacher. Solely because of her race, she was not

considered in comparison with other teacher applicants,

about fifty of whom had not previously taught in the sys

tem. This sort of invidious discrimination offends the Con

stitution. E.g., Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of

Educ., 364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966); Franklin v. County

School Bd., 360 F.2d 325 (4th Cir. 1966); see generally

Note, Discrimination in the Hiring and Assignment of

T eachers in the Public School Systems, 64 Mich. 692 (1966).

We reject the erroneous conclusion of the district court that

the decisions of this circuit in Chambers and Franklin, re

quiring an objective and comparative evaluation with all

other teachers, are not controlling.

III.

Since Mrs. Wall was recommended for reemployment by

her principal and his recommendation approved by the

School Board— subject only to the allotment of spaces, which

was controlled by the same Board— we think the belated

and invidiously unfair rejection of her application for re

employment entitles her to recover damages. Smith v. Bd. of

Educ., 365 F.2d 770, 784 (8th Cir. 1966); Chambers v.

Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ., 364 F.2d 189, 193 (4th

Cir. 1966) ; Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177, 182 (4th Cir.

1966) ; Rolfe v. County Bd. of Educ., 11 Race Rel. L. Rep.

1841, 1846-47, ..... F. Supp.........., ...... (E.D. Tenn. 1966) ;

Macklin v. County Bd. of Educ., 11 Race Rel. L. Rep. 805,

806,.... F.Supp..... ,.... (M.D. Tenn. 1966). Mrs. Wall man

aged to secure employment elsewhere for the school year

1965-66. Proper damage elements will include salary differ

ences, if any, and moving expenses to her new residence. If

she should be reemployed in the Stanly County system for

6

the school year 1967-68, she should also be awarded the rea

sonable expense of moving back to Stanly County.

We further instruct the district court to order the Board

to put Mrs. Wall, if she wishes, on the roster of teaching ap

plicants for the school year 1967-68, and to require that she

then be considered for employment objectively in compari

son with all teachers. The Board will be ordered to consider

her twelve-year experience in the Stanly County school sys

tem to the extent it considers seniority as a factor in the re

tention of other teachers. The Board should be specifically

enjoined from considering her race as a factor in determin

ing whether or not she will be reemployed.

If Mrs. Wall should be denied reemployment, the district

court will require a full report of the reasons for denial, and

will scrutinize it to assure that the School Board has acted

in good faith and without regard to race. Because of the

Board’s prior discrimination against Mrs. Wall, it will carry

“ the burden of justifying its conduct by clear and convincing

evidence.” Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ.,

364 F.2d 189, 196 (4th Cir. 1966).

IV.

On April 15, 1966, the School Board adopted an extreme

ly comprehensive plan governing the hiring and assigning of

personnel in the public schools. The plan establishes stand

ards and procedures for rating and evaluating teachers. It

contains definitions and instructions for the application of

the standards to a given teacher and methods by which at

tributes of the teacher are to be evaluated. We think this ex

haustive plan, if implemented in good faith, is fully sufficient

to assure that “ staff and professional personnel will be em

ployed solely on the basis of competence, training, experi

ence, and personal qualification and shall be assigned to and

7

within the schools of the administrative unit without regard

to race, color, or national origin * * *.,,s

Aside from the facial adequacy of the new plan of teacher

recruitment and assignment, we are advised in open court by

counsel that for the school year 1966-67 some progress has

been made in integrating the faculty and that now some six

or seven Negro teachers are teaching in formerly white

schools. On remand, we instruct the district court to make

further inquiry into the present degree of implementation of

the plan and to consider de novo the question of whether or

not an injunction ought to issue. Only if the district court

concludes that the plan is being implemented according to

its tenor, i.e., that teachers are being hired and assigned with

out racial discrimination, may it reject the prayer for an in

junction. The district court will retain jurisdiction to con

sider motions in the cause as may be necessary to assure fair

and equal treatment of all teachers and to assure that the

plan will not become a paper proclamation of good inten

tions to be filed away and forgotten.

Reversed and Remanded.

3 Resolution on Teacher Hiring Policies, Stanly County, North Carolina,

Board of Education, April 15, 1966.

A d m . O ffice, U . S. C o u rts— 3555— 6-13-66— 150— Lew is P r in tin g C o ., R ich m o n d , V a . 2320?