Littles v. Jefferson Smurfit Corporation (US) Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1995

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Littles v. Jefferson Smurfit Corporation (US) Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1995. 3ae6465b-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b0378af1-3a51-4fff-829d-980f1bd1f0c6/littles-v-jefferson-smurfit-corporation-us-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

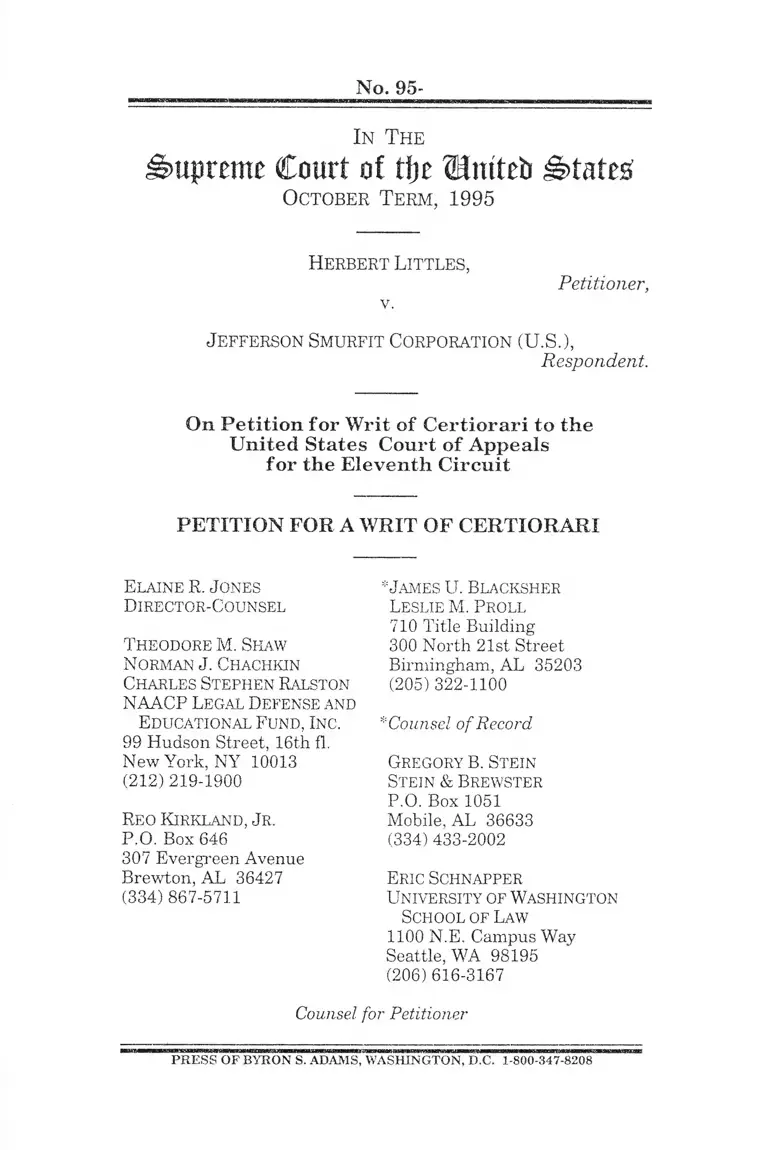

No. 95-

I n T h e

Supreme Court of tfjc fHntteb S ta tes

O cto ber T e r m , 1995

Herbert Littles ,

Petitioner,

v.

J efferson Smurfit Corporation (U.S.),

Respondent.

On Petition fo r Writ o f Certiorari to the

United States Court o f Appeals

fo r the Eleventh Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16t.h fl.

New York. NY 10013

(212)219-1900

Reo Kirkland, Jr.

P.O. Box 646

307 Evergreen Avenue

Brewton, AL 36427

(334) 867-5711

* James IJ. Blacksher

Leslie M. Proll

710 Title Building

300 North 21st Street

Birmingham, AL 35203

(205) 322-1100

*Counsel o f Record

Gregory B. Stein

Stein & Brewster

P.O. Box 1051

Mobile, AL 36633

(334) 433-2002

Eric Schnapper

University of Washington

School of Law

1100 N.E. Campus Way

Seattle, WA 98195

(206) 616-3167

Counsel for Petitioner

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. 1-800-347-8208

Questions Presented

(1) Do sections 1981 and 1982 of 42 U.S.C. forbid the

knowing use of practices which, by perpetuating past

intentional discrimination, completely preclude all African-

American entrepreneurs and black-owned firms from selling

timber to scores of southern pulp and paper mills?

(2) Where a defendant is alleged to maintain, for

discriminatory purposes, practices which perpetuate past

intentional discrimination, may a plaintiff be precluded from

offering evidence that such earlier intentional discrimination

ever occurred?

l

Parties

The parties are the petitioner, Herbert Littles, and

the respondent, Jefferson Smurfit Corporation (U.S.).

Subsequent to the initiation of this action, the original

defendant, Container Corporation of America, merged with

another firm and changed its corporate name to Jefferson

Smurfit Corporation (U.S.). Jefferson Smurfit Corporation

(U.S.) is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Jefferson Smurfit

Group, PLC.

li

Table of Contents

Page

Questions Presented...................................... i

P a rtie s ....................................................................... .. . . . ii

Table of Authorities............................................................ iv

Opinions Below ....................................................................1

Jurisdiction ...................... 2

Statutes Involved............... 2

Statement of the Case ........................................................ 3

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W R IT .....................9

I. This Case Raises Important Issues Regarding

Industry-Wide Segregation In A Vital Area

Of The South’s Economy.........................................9

II. The Decisions Below Are In Conflict With

Decisions Of This Court And Of Other

C ircuits................................................................. 16

Conclusion.......................................... 22

Appendix (opinions and orders below) ......................... la

in

Cases:

Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena,

U.S.__ , 115 S. Ct. 2097 (1995)......................... 22

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . . . 13

Associated General Contractors v. City of

Jacksonville,__ U.S.___ , 113 S. Ct. 2297

(1993)..................... ................ ............................. 22

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986) . . . . 8, 16, 17, 18

Brinkley-Obu v. Hughes Training, Inc., 36 F.2d 336

(4th Cir. 1994)............................................... 18, 19

City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469

(1989)........................... ............................ 9, 19, 22

Columbus Board of Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979)............................................... 19

Dixon v. Anderson, 928 F.2d 212 (6th Cir. 1991) ......... 18

EEOC v Penton Industrial Publishing Co., Inc., 851

F.2d 835 (6th Cir. 1988)........................................ 18

EEOC v. Container Corporation of America, 352 F.

Supp. 262 (M.D. Fla. 1972) .......................... 13

Florida v. Long, 487 U.S. 223 (1988) .............................. 17

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980).................... 22

Table of Authorities

Page

tv

Cases (continued):

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656 (1987) . . . 19

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ........... 17

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915)........... 20, 21

Harrington v. Aetna-Bearing Co., 921 F.2d 717

(7th Cir. 1991)...................... 18

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970)......................... 13

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965)........... 19

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U.S. 368 (1915)......................... 21

Nealon v. Stone, 958 F.2d 584 (4th Cir. 1992) .............. 18

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1968)...................................................... 13

Pallas v. Pacific Bell, 940 F.2d 1324 (9th Cir.

1991)............................................................... 18, 19

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340

(8th Cir. 1975)...................................................... 13

Sigurdson v. Isanti County, 448 N.W.2d 62

(Minn. 1989)................................................. 18, 19

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

v

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Stevenson v. International Paper Co., 516 F.2d

103 (5th Cir. 1975) ............................................. 13

Suggs v. Container Corporation, Civ. No. 7058-72-P

(S.D. Ala. 1974) .................................................. 13

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc.,

402 U.S. 1 (1974)................................................. 19

United States v. Fordice, 505 U .S.__ , 112 S. Ct.

2727 (1992)........................................................... 20

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159 (5th Cir.

1976)........... 13

Webb v. Indiana National Bank, 931 F.2d 434

(7th Cir. 1991)...................................................... 18

West Virginia Institute of Technology v. West

Virginia Human Rights Commission, 383

S.E.2d 490 (W. Va. 1989)............................. 18, 19

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ............................................................. 14

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982 . . ................ i, 2, 3, 5, 7, 16, 17

42 U.S.C. §1982 . . . . . 2, 7, 14

Other Authorities:

Alabama Forestry Commission, Alabama’s World

Class Forest Resource Fact Book 1995

(1995) .................................................................... 10

Alabama Forestry Commission, Forests of

Alabama (1992).................................................... 11

The Brewton Standard, July 31, 1994 ........................... 11

The Brewton Standard, June 30, 1993 ........................... 11

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Economic

Review, Jan./Feb. 1988 ................................ 10, 11

Edward McPherson, The Political History of the

United States During the Period of

Reconstruction (1875)........................................... 14

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural

Statistics 1993 (1993) ................................. 10

U.S. Department of Commerce, State and

Metropolitan Area Data Book 1991 (1991)......... 10

Laurence C. Walker, The Southern Forest: A Chronicle

(1991).............................................................. 9, 10

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

In the

Supreme Court of ti)e Mmteb States?

October Term, 1995

No. 95-

H e r b e r t Lit t l e s ,

Petitioner,

v.

Je f f e r s o n Sm u r f it C o r p o r a t io n (U .S .),

Respondent.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Eleventh Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Petitioner Herbert Littles respectfully prays that this

Court grant a writ of certiorari to review the judgment and

opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Eleventh Circuit entered on March 28, 1995. The Court of

Appeals denied a timely petition for rehearing on June 13,

1995.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Eleventh Circuit, which is not

officially reported, is set out at pp. la-2a of the Appendix

hereto ("App."). The order of the Court of Appeals denying

petitioner’s petition for rehearing and suggestion for

rehearing en banc is unreported, and is set out in App. 48a-

49a.

The order of the district court of April 30, 1992,

denying class certification, is set out at App. 3a-lla. The

opinion and order of the district court of March 3, 1992,

denying cross motions for summary judgment, are set out at

App. 12a-27a. The two district court orders regarding

motions in limine, both dated August 23, 1993, are set out

at App. 28a-33a and 34a-36a. The district court’s oral

rulings on the admissibility of certain evidence are set out at

App. 37a-41a. The jury verdict is set out at App. 42a-43a.

The district court’s order of December 1, 1993, denying

petitioner’s motion for equitable relief, is set out at App.

44a-45a. The district court order of February 10, 1994,

denying petitioner’s motion for judgment as a matter of law,

is set out at App. 47a. None of the district court orders is

officially reported.

Jurisdiction

The decision of the Eleventh Circuit was entered on

March 28, 1995. Petitioner’s timely petition for rehearing

and suggestion for rehearing en banc was denied on June 13,

1995. On September 9, 1995, Justice Kennedy granted an

order extending the time for filing a petition for a writ of

certiorari until September 21, 1995.

Statutes Involved

Section 1981(a) of 42 U.S.C. provides in pertinent

part:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every state and

territory to make and enforce contracts . . . as is

enjoyed by white citizens. . . .

Section 1981(c) of 42 U.S.C., provides:

The rights protected by this section are protected

against impairment by nongovernmental

discrimination and impairment under color of State

law.

Section 1982 of 42 U.S.C. provides:

All citizens of the United States shall have the same

right, in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by

2

white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell,

hold, and convey real and personal property.

Statement of the Case

This case concerns a practice peculiar to the southern

forest products industry pursuant to which scores of pulp

and paper mills will buy timber only from whites. The

courts below held that this practice, despite its enormous

economic impact, does not violate 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and

1982, even where a mill operator knows the practice

perpetuates its own intentional discrimination.

Most southern pulp and paper mills purchase their

timber supplies, known as "pulpwood," as does respondent,

through a system of exclusive "dealers." Under this

dealership system a mill designates a pre-selected group of

firms as its "dealers" and refuses to buy lumber from anyone

else. The dealers themselves may not necessarily cut, deliver

or own all or even any of the timber they "sell" to the mill.

Rather, because the dealers enjoy this exclusive right, any

firm which wants to supply wood to the mill must do so

under the auspices of a dealer and must pay the dealer for

permission to deliver wood to the mill. Firms which cut and

haul timber to these mills, but which have not been

designated as dealers, are known in the industry as

"producers."

It is undisputed that today literally all of the dealers

throughout the South are white. In the proceedings below

respondent so stipulated:

[Counsel for Petitioners]: We are . . . going i . . to

show that there are no black dealers anywhere . . .

The fact is that nobody has found, either on our side

or the defendant’s side, throughout the case a single

black wood dealer anywhere in the south.

3

THE COURT: [I]f it’s relevant that there are no

black wood dealers anybody knows of in any industry,

you don’t need a witness to prove i t . . . . You can ask

any Container witnesses on the stand on cross

[Counsel for Respondent]: It is a stipulated fact,

Judge.

THE COURT: Okay. Then that eliminates that.

(Tr. 41). A succession of white wood dealers and others

testified that there are in fact no black wood dealers.1

Respondent’s forestry expert acknowledged that use of this

"dealer" system is widespread in the South.* 2

Respondent operates in Brewton, Alabama, one of

the mills utilizing this dealer system. It buys pulpwood

exclusively from a group of approximately forty "dealers," all

of whom are white (App. 5a). Petitioner is one of the

African-American producers with whom respondent refuses

to contract. Although petitioner has been supplying

xTr. 365-66, 578, 673, 689, 705, 840. An expert on the lumber

industry called by respondent could identify in the entire history of

the South only one black businessman who had ever been a dealer.

The expert explained that this had occurred in the "[l]ate sixties, early

seventies . . . under the pressure of the Federal Government" and

that the black logger in question had actually functioned as a dealer

for only "about six or seven weeks" (Tr. 782). The expert conceded

he knew of no black dealers "in Alabama today" (Tr. 780). After

initially suggesting there might be a black dealer in South Carolina,

the expert conceded that the individual in question might merely have

been hired to cut timber on land owned by the mill for which he

worked (Tr. 780-81); such an arrangement would not constitute a

dealership (Tr. 780).

2Tr. 763 ("[t]he vast majority of the industry procures their wood

through . . . the dealer systems"), 771 ("[t]he vast majority . . . of all

the wood that’s produced in the south is through the dealer . . .

system").

4

pulpwood regularly to respondent’s Brewton mill since 1962,

petitioner himself never has been permitted to sell the mill

so much as a single log. Instead, petitioner has been forced

to market his wood to respondent by going through a white

dealer willing to lend his name to the transaction.3 The

economic role of the white dealer, in petitioner’s case, is

nominal. Petitioner himself buys the standing timber,

employs his own crew to cut the trees, and transports the

logs to the mill on his own trucks (Tr. 192). The white

dealer never has possession of or title to the wood, never

actually sees it, and has no reason to know where or when

it was harvested (Tr. 151-52). Petitioner is required to pay

white dealers tens of thousands of dollars a year for

permission to sell wood under their auspices.4

Petitioner filed suit in the district court for the

Southern District of Alabama, seeking an injunction

requiring that he be designated as a dealer, as well as

damages. Petitioner asserted, inter alia, that by utilizing its

particular dealer system, respondent was knowingly

perpetuating prior intentional racial discrimination. His

complaint asserted that such perpetuation violates sections

1981 and 1982 of 42 U.S.C.5

Petitioner alleged that respondent’s practices

perpetuated prior intentional discrimination in two distinct

ways. First, at some point prior to 1979 respondent

concededly froze the list of dealers with whom it would

3As one of respondent’s supervisors pointedly observed, "[h]e has

to sell it to a white man who sells it to Container" (Tr. 111).

“Petitioner pays a dealer a commission of $2.00 to $6.50 per cord

of wood delivered to the mill, or as much as $60.00 for each truck

load (Tr. 200-01).

5Amended Complaint, $1! 22A, 22B.

5

thereafter do business (Tr. 442, 464, 578). As of 1979, of

course, all of respondent’s dealers were white. Petitioner

alleged that prior to 1979 respondent had an intentionally

discriminatory policy of selecting only whites as dealers. The

courts below never addressed that contention, which for the

purposes of this appeal must be assumed to be true.6

Because of this freeze, many of the firms today permitted to

sell wood to respondent are the very firms which were

designated as dealers prior to 1979.7 Increasingly, the

individuals who own and operate respondent’s dealerships

are the sons of the white men who were designated dealers

during the period of alleged avowed intentional

discrimination.8 This system thus perpetuates into the

indefinite future decisions originally made prior to 1979,

allegedly on the basis of race, limiting the firms from which

respondent will buy wood.9

Petitioner asserted, second, that on those occasions

since 1978 when respondent had made an exception to the

freeze and contracted with a new dealer, respondent would

consider only firms which had already been designated as

dealers by some other mill, a restriction respondent admitted

(Tr. 284, 442, 548). All of the firms able to meet this

Respondent’s Answer did not deny it had once practiced racial

segregation at its Brewton mill; it only denied racial discrimination

"during any time period relevant to this lawsuit." Answer 1! 3.

7Tr. 445, 446-47, 560, 598, 599.

8Tr. 548 (ownership of current dealerships often comes "[fjhrough

inheritance. Many times a son will come into an operation that his

father had previously been operating [as] a dealership and his son will

take over the business"), 848.

’Although the firms that held these dealerships were occasionally

sold privately, none was ever sold to a black person.

6

requirement, of course, are -- and always have been — white

(see App. 5a); five new dealers added since 1979 were white.

Petitioner alleged that respondent knew that the other mills

in question engaged in intentional discrimination in

designating these dealers; here too the courts below did not

address or resolve this factual allegation. Firms thus

occasionally added to respondent’s list of dealers were

usually owned by whites who had been doing business as

dealers for decades,10 * or by their children.11

The district court repeatedly held that these claims of

knowing perpetuation of prior intentional discrimination

were not actionable under either section 1981 or section

1982. First, in response to motions for summary judgment,

the district court ruled that the perpetuation allegations

failed to state a claim upon which relief could be granted.

[T]he legal claims raised are not relevant in the

instant action. . . . [Pjlaintiff . . . may not proceed on

the theory that the adoption of policies that

unintentionally "lock in" past discrimination are

sufficient to prove his cause of action under either §

1981 or § 1982.

(App. 26a n.5). Second, after a juiy trial on other issues,

petitioner filed a motion for equitable relief on his

perpetuation claims. The district court denied these claims

as a matter of law, reasoning that "the legal arguments

raised by plaintiff in support of the claims have been

previously rejected by this Court" (App. 44a). Third, the

district court denied petitioner’s post-trial motion for

10Tr. 663 (firm had held dealership with another mill since 1968),

710-11 (firm had held dealership with another mill since 1964), 684

(firm had held dealership with another mill since 1950).

uTr. 685.

7

judgment as a matter of law on the perpetuation claims

(App. 47a).

Petitioner was permitted to proceed to trial only on

the narrow issue of whether after October, 1989,

respondent’s officials had made a specific race-based

decision to deny petitioner a dealership. The district court

granted two motions in limine precluding respondent from

offering evidence of historic discrimination in the selection

of dealers (App. 28a-36a). The court below continued to

preclude such evidence even after, as a supposedly benign

explanation for its actions, respondent relied on the fact

that there were no black wood dealers (Tr. 279-289; App.

37a-41a). The district court rejected instructions proffered

by petitioner which would have permitted the jury to

consider the perpetuation claims.

Petitioner argued below that the decisions of this

Court have repeatedly held unlawful the knowing use of

practices which perpetuate prior intentional discrimination.

Acknowledging that the Court had so held in Bazemore v.

Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986), the district court insisted that

Bazemore applied only to disparate impact claims:

"Bazemore . . . addressed the use of prior act evidence to

prove disparate impact under Title VII. Intent was not an

issue" (App. 30a). Because sections 1981 and 1982 require

proof of discriminatory intent, the court below reasoned,

Bazemore was irrelevant.

On appeal petitioner argued that sections 1981 and

1982 forbid utilization of practices known to perpetuate

prior intentional discrimination. The court of appeals, in a

summary opinion devoid of explanation, affirmed the

dismissal of the perpetuation claims (App. la-2a, 48a-49a).

8

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I. This Case Raises Important Issues Regarding

Industry-Wide Segregation In A Vital Area Of The

South’s Economy

Six years ago this Court observed that "the sorry

history of both private and public discrimination in this

country has contributed to a lack of opportunities for black

entrepreneurs," City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488

U.S. 469, 499 (1989). The Court noted as well the existence

of "abundant historical evidence" that facially neutral

practices "when applied to minority businesses, could

perpetuate the effects of prior discrimination." 488 U.S. at

488, quoting Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448, 478 (1980).

The legal question presented by this case is whether firms

which long engaged in intentional discrimination against

black entrepreneurs may continue to contract only with

whites by adopting practices which perpetuate that past

intentional discrimination.

The practical question presented is whether a key

portion of the most important industry in the economy of

the South will continue for the indefinite future to be

literally all white. The wood products industry is today the

backbone of the economies of the southern states. What

was once the land of cotton is now the land of timber. The

value of southern timber harvested each year long ago

exceeded the value of any other agricultural crop. In

Alabama the value of the timber harvest equals the

combined value of all other crops grown in the state.12

Southern states account for 58% of all the timber produced

each year in the United States, more than twice the

12Laurence C. Walker, The Southern Forest: A

CHRONrcLE 251-52 (1991).

9

production of the Pacific Coast states.13 Among the states

with the highest percentage of jobs in the wood products

industry, half are in southern states, including Alabama.14

Sixty-six percent of all Alabama land is devoted to forests

with 15 billion trees, compared with only 29% for the

country as a whole.15

The pivotal role of the southern timber industry is

certain to increase in the years ahead. Sixty-six percent of

all new seedlings planted in the United States each year are

in the South; Alabama, with 10% of the total new acreage,

is second in the country.16 Southern states enjoy a natural

advantage in timber production, because "the southern

climate promotes faster tree growth and thus a better per-

acre return over time."17 The percentage of wood

production coming from the South is expected to rise as the

supplies of virgin timber are exhausted in northern

California and the Pacific Northwest.18

The timber industry is particularly important in

Alabama. The state is the second largest pulpwood

13U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural

Statistics 1993 445 (1993).

14U.S. Department of Commerce, State and Metropolitan

Area Data Book 1991 267 (1991).

15Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Economic Review,

Jan./Feb. 1988, at 9; Alabama Forestry Commission, Alabama’s

World Class Forest Resource Fact Book 1995 3 (1995).

^Agricultural Statistics 1993, supra note 13, at 443.

17Economic Review, supra note 15, at 12.

18The Southern Forest: A Chronicle, at 232.

10

producer in the U.S., behind only Georgia.19 The state’s 22

million acres of commercial forest are third in the

countiy.20 The $9.1 billion21 wood products industry

accounts for 18% of manufacturing payrolls in Alabama,

more than any other segment of the state’s economy.22

The state’s 250 mills and 800 secondary wood product

manufacturers23 support, directly or indirectly, more than

150,000 jobs with a related income of approximately $3

billion.24

But, three decades after Congress restated a national

policy of racial non-discrimination, an entire segment of this

industry — wood dealers -- remains all white. The sheer

number of businesses involved, and thus the magnitude of

the economic opportunities foreclosed to blacks, makes this

continuing segregation palpably important. Systemic

exclusion of blacks from the dealership business is all the

more significant because the harvesting of timber is one of

the few areas of the industry available for new small

entrepreneurs. The lumber and paper mills themselves are

generally multi-million dollar facilities, often, as in this case,

owned by large multinational corporations. Because of the

time required for trees to reach maturity, ownership of

timber land is a capital-intensive, long-term investment. But

19Economic Review, supra note 15, at 8.

2(T he Brewton Standard, July 31, 1994, at 10.

21 Alabama Forestry Commission, Forests of Alabama 14

(1992).

22The Brewton Standard, June 30, 1993, at 11.

“Forests of Alabama, at 14.

24Id.

11

a black entrepreneur, whatever his or her expertise,

experience or determination, has virtually no chance to

reach the coveted status of wood dealer. The white

monopoly of economic power in the dealer business

manifestly has broader racial and economic ramifications;

petitioner asserted in the court below, for example, that the

number of black producers in Brewton has declined because

the white dealers, who alone determine who can sell to

respondent and at what price, have intentionally squeezed

black loggers out of business.

The allegations in this case describe a system at the

mill in question which assures with almost mathematical

precision that the mill’s dealers will remain all white in

perpetuity. Respondent’s annually renewed dealer contracts

have long been limited to the dealers designated in years

before, a scheme which reaches back through a chain of

annual dealership contracts to an era prior to 1979, when

respondent allegedly pursued an explicitly discriminatory

policy. If an additional dealer is needed, respondent will

consider only those firms - all white-owned ~ that have

previously been designated as dealers by some other mill.

Ownership of the firms holding these prized dealerships is

increasingly being passed on by inheritance to the children

of the men who decades ago were the beneficiaries of

alleged systemic segregation.

Petitioner asserts that respondent’s practices

perpetuate not some amorphous societal discrimination but

specific acts of discrimination by respondent and other

southern mills taken, as respondent well knew, to assure that

all wood dealers were white. This dealer selection scheme

is the economic equivalent of the infamous grandfather

clause.

That this systemic exclusion of black-owned firms has

occurred in the timber industry is not surprising. Paper

mills, the single largest purchaser of southern timber, were

12

among the most recalcitrant practitioners of racial

segregation. Successful employment discrimination cases

against the pulp and paper segment of the industry are

legion.25 Challenges to racially segregated jobs at

respondent’s own mills in Brewton and Femandina Beach,

Florida, were resolved by settlements which fundamentally

restructured their promotion processes.26 The complete

exclusion of blacks from the role of wood dealer in the

South reflects as well the structure of the industry. In other

areas of economic activity, such as retail sales, there are

numerous potential buyers, many of them black, a

circumstance which prevents total exclusion of black

entrepreneurs. But in the wood products industry, the

pulpwood harvested by tens of thousands of loggers working

for numerous producers can be sold only to a limited

number of mills. Equally important, because transporting

raw timber more than 50 miles is often economically

unfeasible, a single mill may dominate timber production in

a given area. Respondent’s Brewton mill, for example, is the

only paper mill in Escambia County, Alabama, where

petitioner harvests timber.

These circumstances in the southern timber industry

are expressly prohibited by the language of sections 1981 and

1982. In that industry, all persons do not "have the same

^E.g., Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Watkins

v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159 (5th Cir. 1976); Stevenson v.

International Paper Co., 516 F.2d 103 (5th Cir. 1975); Rogers v.

International Paper Co., 510 F,2d 1340 (8th Cir. 1975); Local 189,

United Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970); Oatis v. Crown

Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968).

26Suggs v. Container Corporation, Civ. No. 7058-72-P (S.D. Ala.

1974). See EEOC v. Container Corporation o f America, 352 F. Supp.

262 (M.D. Fla. 1972).

13

right . . . to make and enforce contracts . . . as is enjoyed by

white citizens." 42 U.S.C. § 1981. On the contrary, the only

persons who can make contracts to sell wood to the mills in

question are whites. Similarly, "[a]ll citizens" do not "have

the same right . . . as is enjoyed by white citizens . . . to . . .

sell . . . and convey . . . personal property." 42 U.S.C. §

1982. Only white persons have the right to sell timber to the

southern mills using the dealer system. The problem here

is not that petitioner’s request for a dealership is being

considered and rejected on the merits; rather, respondent’s

system assures that petitioner will never even be considered

for one of its dealer contracts.

The racial structure of this industry is a pristine

illustration of the very abuse sections 1981 and 1982 were

created to end. The 1866 Civil Rights Act was adopted to

make good the promise of the Thirteenth Amendment by

removing obstacles which prevented the newly freed slaves

from escaping a role of economic subservience to whites.

The infamous Black Codes included provisions, calculated to

perpetuate that subservience, which precluded blacks from

selling the goods they had produced on the open market.27

27For example, South Carolina law provided that any "person of

color" employed on a farm "shall not have the right to sell any corn,

rice, peas, wheat, or other grain, any flour, cotton, fodder, hay, bacon,

fresh meat of any kind, [or] poultry of any kind" without written

permission of his "master" or a state judge. Edward McPherson,

The Political History of the United States During the

Period of Reconstruction 35 (1875). Another law in that state

provided that "no person of color shall pursue or practice the art,

trade, or business of an artisan, mechanic, or shopkeeper, or any

other trade, employment or business (besides that of husbandry, or

that of a servant under a contract for service or labor)," unless he or

she obtained a license from a state judge and paid in advance a

prohibitive annual fee of $100. id. at 36. North Carolina law

invalidated any contract by a person of color for the sale "of any

horse, mule, ass, jennet, neat cattle, hog, sheep or goat," or of any

14

The guarantee now contained in section 1982 of the right to

"purchase, lease, hold, and convey real and personal

property" was framed above all to enable African Americans

to participate in the free enterprise economy in their own

right, rather than merely as employees of or under the

auspices of whites.

Thus the issue presented by this case is of decisive

importance for the economic and racial structure of the

southern timber industry. The circumstances of this case

present a particularly compelling claim. Petitioner has been

supplying timber to respondent’s mill for more than three

decades without ever being permitted to sell his goods

directly to the mill, even though petitioner buys all his wood

from landowners and performs all the functions of a dealer.

The dealer selection policy respondent now has in place

guarantees that this situation is unlikely ever to change.

Because wood dealers are independent contractors, not

employees, Title VII is inapplicable. Sections 1981 and 1982

are the only federal laws that could be invoked to end the

total exclusion of blacks from this pivotal role in the

industry. If, as the courts below held, allegations of such

knowing perpetuation of intentional discrimination are never

actionable under sections 1981 and 1982, the exclusionary

dealer system will be immune from judicial scrutiny, and the

wood dealers in Brewton and throughout the South are

likely to remain all white for generations to come.

articles worth more than $10, "unless . . . witnessed by a white

person." Id. at 29. Several Louisiana parishes adopted ordinances

simply directing, "Every negro is required to be in the regular service

of some white person." WALTER FLEMING, 1 DOCUMENTARY

History of Reconstruction 280 (1966 ed.) (1906).

15

II. The Decisions Below Are In Conflict With Decisions

Of This Court And Of Other Circuits

The courts below held that an allegation of knowing

perpetuation of past intentional discrimination does not state

a claim under sections 1981 and 1982. The decisions below

are flatly inconsistent with reported decisions of this Court

and of the other courts of appeals

(1) The lower court acknowledged that the

allegations in the instant case would state a "compelling"

claim if Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986) applied to

claims under sections 1981 and 1982 (App. 26a). In

Bazemore black workers hired prior to 1972 continued to be

paid less then white contemporaries because salary levels

two decades later were still based in part on pre-1972

salaries. 478 U.S. at 394. In the instant case, a white firm

designated as a dealer prior to the pre-1979 freeze is paid

$54.00 if it cuts and delivers a cord of pine pulpwood; a

black owned firm, unable because of race to obtain that

designation prior to 1979, receives only $47.50 to $52.00 for

logging and delivering the identical cord of wood.

Bazemore held that Title VII was violated by

salary disparities created prior to 1972 and

perpetuated thereafter. . . . That the Extension

Service discriminated with respect to salaries prior to

the time it was covered by Title VII does not excuse

perpetuating that discrimination . . . . [T]o the extent

that the discrimination was perpetuated after 1972,

liability may be imposed.

478 U.S. at 395 (emphasis added). In this case, however, the

court below insisted that the Bazemore anti-perpetuation rule

was inapplicable to claims of intentional discrimination.

"Bazemore . . . addressed the use of prior act evidence to

prove disparate impact under Title VII. Intent was not an

16

issue" (App 30a). Thus, the district court reasoned,

Bazemore was irrelevant to a claim of intentional

discrimination under 42 U.S.C.§§ 1981 and 1982 (App. 30a).

This decision is flatly inconsistent with this Court’s

actual opinion in Bazemore itself. Although Title VII applies

both to intentional discrimination and to certain instances of

disparate impact, the salary claim in Bazemore was an intent

claim. Had Bazemore involved a disparate impact claim, a

judicial determination of the legality of existing wage

disparities would have required consideration, inter alia, of

whether locking in pre-Act disparities might have been

justified by "business necessity". But the Court’s opinion in

Bazemore refers neither to the essential disparate impact

standards nor to any of the Court’s numerous disparate

impact decisions. E.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971). Rather, this Court held simply that "the present

salary structure . . . is illegal if it is a mere continuation of

the pre-1965 discriminatory pay structure", 478 U.S. at 397

n.6, a holding that made sense only if the Court regarded

such perpetuation as a species of intentional discrimination.

Subsequent decisions of this Court have recognized that the

perpetuation in Bazemore violated Title VII because it

amounted to a continuation of intentional pre-1972

discrimination. Thus in Florida v. Long, 487 U.S. 223, 239

(1988), the Court explained that "Bazemore concerned the

continuing payment of discriminatory wages based on

employer practices prior to Title VII."

The lower court’s decision limiting Bazemore to Title

VII effect claims conflicts as well with decisions in three

other circuits and with decisions by two state supreme

courts. These other jurisdictions uniformly agree that the

circumstances in Bazemore were unlawful because they

constituted a continuance of the original pre-1972

intentional discrimination. This contrary rule prevails in the

17

Fourth,28 Sixth,29 and Seventh Circuits,30 as well as in the

states of Minnesota31 and West Virginia32. Far from

limiting Bazemore to Title VII disparate impact claims, as

did the courts below, these other jurisdictions treat Bazemore

as equally applicable to claims under section 1981,33 the

Equal Pay Act,34 the Age Discrimination in Employment

Act,35 ERISA,36 the Pregnancy Discrimination Act37 and

28 Brinkley-Obu v. Hughes Training, Inc., 36 F.2d 336, 347 (4th

Cir. 1994) (Bazemore a "‘continuing’ violation"); Nealon v. Stone, 958

F.2d 584, 592 (4th Cir. 1992) (continuing violation principle applies

under Bazemore).

29 Dvcon v. Anderson, 928 F.2d 212, 216 (6th Cir. 1991)

{Bazemore example of "continuing violation"); EEOC v Penton

Industrial Publishing Co., Inc., 851 F.2d 835, 838 (6th Cir. 1988) ("The

Supreme Court has recognized the existence of a ‘continuing

violation’ so long as disparities continue").

30 Webb v. Indiana National Bank, 931 F.2d 434, 437 (7th Cir.

1991) (Bazemore a "continuing violation" so long as "[t]he disparity in

pay persisted").

31 Sigurdson v. Isanti County, 448 N.W.2d 62, 67-68 (Minn. 1989)

(Bazemore recognizes "the continuing violation doctrine").

32 West Virginia Institute o f Technology v. West Virginia Human

Rights Commission, 383 S.E.2d 490, 499 (W. Va. 1989) (Bazemore a

"disparate treatment" claim involving a "continuing violation").

33 Webb v. Indiana National Bank, 931 F.2d at 437.

34 Brinkley-Obu v. Hughes Training, Inc., 36 F.3d at 345-50;

Nealon v. Stone, 958 F.2d at 590 n.4; EEOC v. Penton Industrial

Publishing Company, Inc., 851 F.2d at 838.

35 Harrington v. Aetna-Bearing Co., 921 F.2d 717, 721 (7th Cir.

1991).

18

a variety of state anti-discrimination laws.36 37 38 None of these

decisions concerned, or suggested these other statutes even

encompassed, disparate impact claims.39

(2) The decision below is inconsistent as well with

half a century of decisions of this Court interpreting the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, which like sections

1981 and 1982 prohibit intentional racial discrimination.

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656 (1987).

This Court has repeatedly struck down facially

neutral state practices where they perpetuated prior

discrimination. Thus the Court has held that states cannot

continue to use voter registration lists constructed in a

discriminatory manner even if subsequent registration is to

be conducted in a non-discriminatory manner, Louisiana v.

United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154-56 (1965). In Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 21 (1974),

the Court forbade former de jure segregated school systems

from utilizing facially neutral practices which "perpetuate

. . . the dual system." See Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488

U.S. 469, 524 (1989) (Scalia, J., concurring) (Fourteenth

Amendment requires modification of student assignment

practices which "perpetuate a ‘dual system’"); Columbus

Board of Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 460 (1979) (school

officials must assure that even facially neutral practices "do

36 Pallas V. Pacific Bell, 940 F.2d 1324, 1327 (9th Cir. 1991).

37 Pallas v. Pacific Bell, 940 F.2d at 1326-27.

38 Id. (California Fair Employment and Housing Act); Sigurdson

v. Isanti County, 448 N.W. 2d 62, 67, 68 (Minn. 1989) (Minnesota

Human Rights Act); West Virginia Institute of Technology, 383 S.E. 2d

at 499 (West Virginia Human Rights Act).

39 See, e.g., Brinkley-Obu v. Hughes Training, Inc., 36 F.3d at 334-

51 (applying Bazemore to a Title VII intent claim).

19

not serve to perpetuate . . . the dual school system"). In the

context of higher education the Court has held that a state

remains in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment if it "has

perpetuated its formerly de jure segregation in any facet of

its institutional system," United States v. Fordice, 505 U.S.

__ , 112 S. Ct. 2727, 2735 (1992); see also id. at 2742

(facially neutral college mission designations adopted for

non-discriminatory purpose nonetheless unconstitutional

absent special justification if they "tend to perpetuate the

segregated system"), 2743 (state has not met its

constitutional obligations "when it perpetuates a separate but

‘more equal’" segregated system).

The circumstances of this case bear an uncanny

resemblance to the infamous "grandfather clause" found

unconstitutional in Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347

(1915). The statute in Guinn exempted from certain

onerous voter registration requirements any person "who

was, on January 1, 1866, . . . entitled to vote . . . [or any]

lineal descendant of such person." 238 U.S. at 357. In the

instant case, the exclusive right to do business with

respondent, like the right to vote in Guinn, is increasingly

exercised by the descendants of the original white

beneficiaries of discrimination. Like the pre-1979 freeze in

the instant case, the grandfather clause perpetuated

indefinitely the favored treatment of whites that had

occurred in the past. The grandfather clause, like

respondent’s policy freezing the pre-1979 dealer list,

contained on its face no express racial distinction,

but the standard itself inherently brings that result

into existence since it is based purely upon a period

of time [of avowed discrimination] and makes that

period the controlling and dominant test of the right

of suffrage.

238 U.S. at 364-65. The freeze at issue in the instant case

establishes as "the controlling and dominant test" of

20

qualification for a current dealership whether a firm had

been able to obtain a dealership prior to 1979, an era,

petitioner alleges, when it was respondent’s avowed policy to

designate only whites as dealers.

(3) The decision below also departed from the

teachings of this Court in holding that sections 1981 and

1982 permitted respondent to limit any new post-1979

dealers to firms already designated as dealers by other mills,

where petitioner alleged that respondent well knew that

those other mills had discriminated and continued to

discriminate on the basis of race in selecting dealers.

In Guinn, for example, the Oklahoma grandfather

clause conferred special status on persons who were "on

January 1, 1866, or at any time prior thereto, entitled to vote

under any form of government." 238 U.S. at 384. The

discriminatory status quo ante thus incorporated into.

Oklahoma law was primarily the discriminatory voter

registration requirements imposed by jurisdictions other than

Oklahoma. In 1866 most of what is now Oklahoma was

Indian territory, and virtually all of the whites who in 1910

received favorable treatment under the Oklahoma law did so

because they were descendants of white residents of other

states. If it was intentional discrimination for Oklahoma

thus to perpetuate discrimination by Texas and other

southern states, surely the same is true where respondent

bases its contracting practices on other mills’ intentional

discrimination, of which petitioner alleged that respondent

was aware.40

40 In a decision handed down the same day as Guinn, the Court

struck down an Annapolis ordinance which exempted from certain

restrictive registration requirements "descendants of any person who

prior to January 1, 1888, was entitled to vote in this State or in any

other State of the United States." Myers v. Anderson, 238 U.S. 368, 377

(1915) (emphasis added). This standard effectively perpetuated pre-

21

(4) The evidentiary issues presented by this case are

inextricably intertwined with the question presented

regarding the scope of sections 1981 and 1982. In barring

evidence of the historic exclusion of blacks from wood

dealerships, the district court avowedly relied on its view that

those sections simply did not forbid the knowing

perpetuation of past intentional discrimination. The

exclusion of that evidence thus rested on a mistaken

interpretation of the substantive statutes at issue, not on any

exercise of discretion.

Conclusion

The Court has dealt repeatedly and forcefully in the

past with the problem of remedying discrimination against

black citizens seeking to be hired and fairly treated by

employers. It has had fewer opportunities to exercise its

discretionary jurisdiction to grapple with the equally severe,

widespread and persistent problems faced by black-owned

firms or contractors and African-American entrepreneurs

who seek to enter and to compete effectively in our nation’s

market economy. The Court has, rather, heard and decided

principally reverse-discrimination claims by white-owned

businesses. See Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena,__ U.S.

__ , 115 S. Ct. 2097 (1995); Associated General Contractors

v. City o f Jacksonville,__ U .S.___ , 113 S. Ct. 2297 (1993);

City o f Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989);

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980).

The constitutional issues raised by these cases were

of considerable moment. But surely the availability or non

applicability of federal statutory remedies to eradicate actual

discrimination against black entrepreneurs is as important an

issue for review as was ensuring, in those earlier cases, that

1868 discrimination in all of the states from which Annapolis

residents might have migrated by the early twentieth century.

22

voluntary remedial measures do not exceed permissible

limits. For that reason, as well as for those given above, a

writ of certiorari should issue to review the judgment and

opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit in

this matter.

Respectfully submitted,

E l a in e R . Jo n e s ,

Director-Counsel

T h e o d o r e M . Sh a w

N o r m a n J. Ch a c h k in

C h a r l e s St e p h e n R a l s t o n

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

R eo Kir k l a n d , Jr .

P.O. Box 646

307 Evergreen Avenue

Brewton, AL 36427

(334) 867-5711

*Ja m e s U . B l a c k sh e r

L e sl ie M . Pr o l l

710 Title Building

300 North 21st Street

Birmingham, AL 35203

* Counsel o f Record

G r e g o r y B . St e in

St e in & B r e w s t e r

P. O. Box 1051

Mobile, AL 36633

(334) 433-2002

E r ic Sc h n a p p e r

U n iv e r s it y o f

W a sh in g t o n Sc h o o l

o f L a w

1100 N.E. Campus Way

Seattle, WA 98195

(206) 616-3167

Counsel for Petitioner

23

APPENDIX

March 28, 1995

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 94-6205

Non-Argument Calendar

D.C. Docket No. VC-91-0851-CB-S

HERBERT LITTLES,

Plaintiff-Counter-Defendant-Appellant,

versus

CONTAINER CORPORATION OF AMERICA,

Defendant-Counter-Claimant-Appellees.

CLAUDE ALFORD,

Movant.

Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Southern District of Alabama

(March 28, 1995)

Before TJOFLAT, Chief Judge, DUBINA and

BARKETT, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

Appellant is a producer of pulp wood. He sells the

pulp wood he cuts to pulp wood dealers; the dealers, in turn,

sell the wood to, among others, appellee’s paper mill in

2a

Brewton, Alabama.

In the district court, appellant contended that

appellee had discriminated against him on account of his

race, in violation of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982, by refusing

to enter into a dealership contract with appellant. Appellant

sought money damages and injunctive relief (requiring

appellee to make him on of appellee’s dealers). A jury

found that appellee had not discriminated against appellant

as alleged; accordingly, the district court gave appellee

judgment on appellant’s damages claim. Relying on the

jury’s finding of no discrimination, the court also denied

appellant the injunction he sought.

Following the entry of final judgment for appellees,

appellant moved the district court (1) for judgment as a

matter of law, (2) to amend the court’s findings of fact, (3)

to alter or amend the judgment, and, alternatively, (4) for a

new trial. The court denied appellant’s motions.

Appealing, appellant contends:

First, that the district court erred in refusing to grant

appellant judgment as a matter of law "on his claim that

[appellee] refused to give him a wood dealer contract

because of his race,"

Second, that the district court should have granted

him a new trial "because the district court abused its

discretion by excluding crucial evidence of [appellee’s] racial

motives, and

Third, that the district court abuse[d] its discretion by

refusing to certify this desegregation case as a Rule 23(b)(2)

class action."

None of appellant’s contentions has merit. Given the

evidentiary record in this case, appellant’s first contention is

frivolous. As for his second and third contentions, appellant

fails to demonstrate an abuse of discretion.

The judgment of the district court is, accordingly,

AFFIRMED.

3a

April 30th, 1992

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

HERBERT LITTLES,

Plaintiff,

CIVIL ACTION NO.

91-0851-B-S

v.

CONTAINER CORPORATION OF

AMERICA,

Defendant.

ORDER

This matter came before the Court on March 4,1992

for a hearing to determine plaintiffs right to bring his action

as a class action pursuant to Rule 23(a), (b)(1), and (b)(2)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure on behalf of "all

black persons residing in the Brewton, Alabama area who

may now or in the future wish to enter into wood supplier

or wood dealer contracts with defendant, or who may wish

to be employed by such suppliers ..." (See Plaintiffs

Amended Complaint).

Findings of Fact

Herbert Littles, by his testimony, is a logging

contractor with some 30 years experience who basically "cuts

and hauls" longwood timber. He has asked Container

Corporation of America (herein CCA) for a dealership so he

can make more money, and be more in control by knowing

what his workload would be and having the assurance that

by converting his equipment to shortwood capacity to meet

CCA’s needs, he would be able to absorb the cost. He has

4a

been a logging contractor, producing wood for the last six to

eight years for Tri-State Timber Company which is a CCA

dealer. Tri-State is owned by Claude Alford, whose

deposition testimony largely reveals the source of Littles’

complaint. Alford himself was a logger before he bought it.

It appears he may well have been less experienced and stable

in the logging industry than Littles was, (Alford’s deposition,

pages 24-30) at the time Littles applied for a dealership with

CCA. This issue will be left to be developed at the trial of

Littles’ underlying complaint which challenges CCA’s refusal

to enter into a dealership agreement with Littles "on account

of his race and color and pursuant to its purposefully

discriminatory policy . . . of excluding black persons . . ."

(Plaintiffs Complaint, para. 23).

Without, however, addressing the merits of plaintiffs

personal cause of action, the issue before the Court on

plaintiffs request to represent a class of similarly situated

blacks rises and falls, (and in this case falls), on one of the

prongs of the four part test of Rule 23(a), specifically

23(a)(1): "The class is so numerous that joinder of all

members is impracticable." The analysis of this aspect

obviates the need to address any of the other prerequisites

of 23(a) or of (b)(1) and (b)(2).

Littles was able to "identify" only four to fix other

black logging contractors in the Brewton area who hauled

wood, presumably for other dealers, to CCA’s Brewton mill.

There used to be a lot more in the past, he testified, but not

now as this has constantly changed over the years. When

asked by his own counsel whether the number of black

logging contractor in the area who would "constitute the

class" would be more or less than 50 he answered "yes."

Needing clarification, he was asked "more or less?" His

answer (and here the Court is quoting from its bench notes,

which if they are not one hundred percent accurate, clearly

reflect the substance of Littles’ answer): "I don’t know the

interest of the people. I have that gut feeling that if I am

given this chance, the number could exceed more than 50,

but I can’t give you a number." His cross-examination

5a

testimony was more specific, that he didn’t know of one

black logging contractor that had gone to CCA to ask for

dealership, nor did he know if any of those were qualified to

be CCA dealers.

Littles did produce several witnesses, including

Tommy Odom, a black logging contractor (apparently one

of the four to six) who testified he would like to be a dealer

with CCA. Thomas Watson, another black logger testified

he had never asked for a dealership because, as he put it, "it

just came to my mind" that if he applied, the dealer he

worked for, (not CCA) might terminate him.

Finally, CCA’s procurement manager, Don Heath,

testified that for reasons of economy CCA had reduced its

number of authorized dealers from sixty-six in 1984 to thirty-

eight as of 1991. During this period about fifty people had

applied for new dealerships, and all but five were turned

down. Of the fifty, two were black, Littles and Thomas

Moore.

Conclusions of Law

Plaintiffs underlying claim is that CCA refused to

enter into a dealership contract to purchase wood from him

because he is black, in violation of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and

1982. Plaintiff asserts that CCA’s refusal to contract with or

purchase directly from him is part of an intentional policy of

discrimination which affects all blacks in the logging industry

in the Brewton area. Hence, plaintiff seeks to maintain this

action as a class action on behalf of himself and all other

blacks who now, or in the future, wish to be wood dealers,

wood suppliers or who wish to be employed by wood dealers

or suppliers.

The class action was developed in equity and refined

by the drafters of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to

promote the efficient resolution of multiple claims or

liabilities in a single action, to eliminate repetitious litigation

and inconsistent adjudications involving common questions

of law or fact, and to establish an effective procedure for

those who might otherwise be economically unable to resort

6a

to litigation. C. Wright, A, Miller and M. Kane, Federal

Practice and Procedure § 1754 (1986). "[T]he class action

device saves the resources of both the courts and the parties

by permitting an issue potentially affecting every [class

member] to be litigated in an economical fashion under

Rule 23." Califano v. Yamasaki, 442 U.S. 682, 701 (1979).

In light of these objectives, Rule 23 sets forth

requirements that must be satisfied before an action may be

maintained as a class action. The plaintiff bears the burden

of persuading the Court that all of the prerequisites of Rule

23(a) and at least one of the prerequisites of Rule 23(b) are

satisfied if a class is to be certified. See Exell v. Mobile

Hous. Bd., 709 F.2d 1376, 1380 (11th Cir. 1983). Rule 23(a)

sets out the following prerequisites:

(1) the class is so numerous that joinder of all

members is impracticable, (2) there are questions of

law or fact common to the black, (3) the claims or

defenses of the representative parties will fairly and

adequately protect the interests of the class.

Plaintiff purports to maintain this action under subdivisions

(b)(1) and (b)(2). Because the plaintiff has clearly failed to

satisfy the first requirement of subdivision (a), commonly

referred to as numerosity, there is no need to address the

remaining prerequisites.

In order to determine whether the number of

potential plaintiffs is no numerous as to make joinder

impracticable, the Court must first define the scope of the

class. Dudo v. Schaffer, 82 F.R.D. 695, 699 (E.D. Pa. 1979).

It is axiomatic that plaintiff cannot represent a group of

which he is not a member. See East Texas Motor Freight Sys.

v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 395 (1977) (holding that plaintiffs who

were not qualified to be line-drivers could not represent

class of persons who were denied line-driver positions);

Wright, Miller & Kane, supra., § 1761. If plaintiff is to be

considered a member of a class, there must be some nexus

between him and the group he seeks to represent. Walker

7a

v. Jim Dandy, Co., 747 F.2d 1360, 1364 (11th Cir. 1984). In

addition, plaintiff cannot represent a class of persons whose

interests conflict with his own. Scott v. University of

Delaware, 601 F.2d 76, 85-86 (3d Cir.), cert, denied. 444 U.S.

931 (1979).

Plaintiff purports to represent "all black persons

residing in the Brewton, alabama, area who may now or in

the future wish to enter into wood supplier or wood dealer

contracts with defendant or who may wish to be employed

by such suppliers or contractors." The class, as defined by

plaintiff, can be divided into three subgroups: (1) those who

may now or in the future wish to enter wood dealer

contracts, (2) those who may now or in the future wish to

enter wood supplier contracts, and (3) those who may now

or in the future wish to be employed by wood dealers or

suppliers.

Plaintiff is a member of and can represent only the

first subgroup. Littles is now a wood supplier who would

like to enter a wood dealership contract with the defendant.

Not only is Littles not a member of the latter subgroups, he

would appear to have a conflict with those groups. Id. He

cannot represent those who wish to become wood suppliers

because he already is one. Since only a limited amount of

wood is needed by dealers who supply CCA, Littles would

be competing with those who wish to become suppliers.

Likewise, he cannot represent those who may wish to be

employed by wood dealers or suppliers. He cannot

represent those who wish to be employed by a dealer

because he is already employed by a dealer. He cannot

represent those who wish to be employed by a supplier

because he is a supplier.

Moreover, plaintiffs cause of action based on

defendant’s alleged discriminatory refusal to contract is

inapplicable to the latter subgroups. It is undisputed that

CCA procures lumber only through dealers and does not

contract with or purchase directly from any wood supplier.

Nor does it contract with or purchase from anyone who is

employed by a wood dealer or supplier. Thus CCA cannot

8a

be said to have discriminated by refusing to contract in areas

where it does not contract in the first place or by refusing to

purchase from certain members of a group from which it

does not purchase in the first place. The proper scope of

the class, therefore, if all blacks in the Brewton, Alabama,

area who may now or in the future wish to enter wood

dealership contracts with CC^A. Plaintiff could identify

only four to six logging contractors currently in the Brewton

area but contends that he nevertheless has satisfied the

numerosity requirement because the class includes future

members who by their very definition make joinder

impracticable.1

There is disagreement among courts as to the impact

of future class members on the numerosity requirement in

a (b)(2) class action where the plaintiff seeks injunctive relief

which may have an impact on future class members. Some

seem to suggest that the inclusion or future members per se

satisfies the numerosity requirement. Se.g., Phillips v. Joint

Legislative Comm, on Performance & Expenditure Review, 637

F.2d 1014 (5th Cir. Unit A Feb. 1981), cert, denied, 456 U.S.

960 (1982). Such an approach, however, is contrary to the

Supreme Court’s admonition in General Tel. Co. of the

Southwest v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147, 161 (1‘982), that a class

action should be certified only "if the trial court is satisfied,

after a rigorous analysis, that the prerequisites of Rule 23(a)

have been satisfied." At the other end of the spectrum,

some courts refuse to consider future members of all. See,

e.g., Selzer v. Board of Educ.. 1112 F.R.—. 176 (S.D.N.Y.

1986) (excluding future members from class definition).

The more reasoned approach, however, considers the

existence of future members in light of all of the

1 The Court understood Littles’ testimony that he had a "gut

feeling" that the number of black logging contractors who would be

interested in contracts with CCA if he were successful would be

greater than fifty to be an estimate of future class member. This

estimate is pure speculation and has no basis in fact.

9a

surrounding circumstances. See, e.g., Scott, 601 F.2d at 88

("[Ojbjectives [of Rule 23] are undermined... by the facile

conclusion that the numerosity requirement may always be

satisfied in antidiscrimination class actions because there

exist unidentified future class members who may suffer

discrimination.'1). One commentator has identified several

factors to be considered when the class is small:

Apart from class size, factors relevant to the joinder

impracticability issue include judicial economy arising

from avoidance of a multiplicity of actions,

geographic dispersement of class members, size of

individual claims, financial resources of class

members, the ability of claimants to institute

individual suits, and requests for prospective

injunctive relief which would involve future class

members.

Newberg on Class Actions § 3.06 (1985).

In an action such as this there is no need for class

treatment. There is no reason to believe that the number of

persons who may be harmed in the future by defendant’s

allegedly discriminatory conduct is so great that judicial

economy or the interests of the parties would favor

resolution in a single action. Cf Rodriguez v Department of

Treasury, 108 F.R.D. 360, 363 (D.D.C. 1985) (Inappropriate

to allow a purely speculative class to be the sole basis for the

satisfaction of the numerosity requirement); Durden v. R.H.

Bouligny, 22 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. 1455 (N.D. Fla. 1979

(Plaintiff must prove that class of future members would be

of sufficient size as to make joinder impracticable).

The potential class is limited by definition to a

sparsely populated rural area. It is further limited to

persons in the logging industry who wish to become wood

dealers with CCA. CCA has drastically reduced the number

of its wood dealers in recent years and has entered into only

five new dealership contracts since 1984. Although he

resources of potential litigants are likely to be small and the

size of the claims are unknown at this point, future members

10a

would have both incentive and resources to pursue their

claims since both punitive damages and attorneys’ fees are

available under Section 1981 and 1982. Claiborne v. Illinois

Cent. R. R., 583 F.2d 143 (5th Cir. 1978) (punitive damages

available under § 1981), cert, denied, 442 U.S. 934 (1979);

Gore v. Turner, 563 F.2d 159 (5th Cir. 1977) (punitive

damages available under § 1982); 42 U.S.C. § 1988 (Supp.

1986) (attorneys’ fees available under both sections).

It is also important to consider the effect of this

action on the rights of these future class members. Scott,

601 F.2d at 88. Future members would be bound by the

outcome of this action, whether favorable or unfavorable to

them. Since they are as yet unknown, future members,

unlike class members now in existence, cannot opt out and

have no way to protect their interests. The likely deterrent

effect of a possible favorable outcome to the plaintiff in this

cas lessens the need to certify the class. Furthermore, the

injunctive relief requested by plaintiff, if given, could benefit

all future plaintiffs.2

The Court’s conclusion that future class members do

not satisfy the numerosity/impracticability of joinder

requirement in this case is not in conflict with he circuit

precedents upon which plaintiff relies. In Kilgo v. Bowman

Transp., Inc., 789 F.2d 859, 878 (11th Cir. 1986), the Court

held:

[Tjhe district court did not abuse its discretion in

finding that the numerosity requirement had been

met. Plaintiffs have identified at least thirty-one

individual class members, and the class incudes

future and deterred job applicants, which of necessity

cannot be identified. The certified class also includes

applicants from a wide geographical area.

2 The scope of the injunctive relief depends, of course, upon

the nature of the wrong. The Court cannot say at this point whether

injunctive relief would have a direct effect on future class members.

11a

In reaching the conclusion that the requirements of 23(a)(1)

had been met, the appellate court noted that "[practicability

of joinder depends on many factors, inclusion, for example,

the size of the class, ease of identifying its numbers and

determining their addresses, facility of making service on

them if joined and their geographic dispersion." Id.

Nor do Phillips v. Joint Legislative Comm, on

Performance Evaluation & Expenditure Review, 637 F.2d 1014

(5th Cir. Unit A feb. 1981), and Jack v. American Linen

Supply Co„ 498 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1974), compel the

certification of a class based solely on the existence of future

members. In Phillips, the court, relying on Jack, held that

noted that [tjhe alleged class contains future and deterred

applicants, necessarily unidentifiable. In such a case the

requirement of Rule 23(a)(1) is clearly met, for ’joinder of

unknown individuals is certainly impracticable.’" Phillips, 637

F.2d at 1024 (quoting Jack, 498 F.2d at 124). However, in

both Phillips and Jack, plaintiffs had identified thirty-three

and fifty-one members, respectively, already in existence,

numbers which would probably be sufficient, without the

presence of future members, to meet the numerosity

requirement. See Cox v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 784

F.2d 1546 (11th Cir.), cert, denied, 479 U.S. 883 (1986).

Consequently, the presence of future members seems to

have been only one factor in the numerosity/practicability of

joinder consideration.

In sum, the Court finds that in this instance a class

action is unnecessary. Plaintiff has failed to persuade the

Court that the number of present or potential future

members of the class are sufficiently numerous to satisfy the

numerosity requirement of Rule 23(a)(1). It is, therefore,

ORDERED that plaintiffs request for class certification be

and hereby is DENIED.

DONE this the 30th day of April, 1992.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

12a

March 3, 1993

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

HERBERT LITTLES,

Plaintiff,

CIVIL ACTION NO.

91-0851-B-S

v.

CONTAINER CORPORATION OF

AMERICA,

Defendant.

OPINION AND ORDER

This matter is before the Court on cross motions for

summary judgment. Defendant Container Corporation of

America seeks dismissal of the plaintiffs claim in its entirety.

Plaintiff Herbert Littles seeks partial summary judgment on

certain issues related to alleged past discrimination by the

defendant. After careful consideration of the motions, the

supporting briefs and evidence submitted by the parties and

the relevant law, the Court finds that both motions are due

to be denied.

FINDINGS OF FACT

Plaintiff Herbert Littles, who is black, is a wood

producer or supplier who operates in the Brewton, Alabama

area. Littles contends that defendant Container Corporation

of America ("CCA") has discriminatorily denied him a wood

dealership contract on account of his race in violation of 42

U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982. CCA operates a paper mill in

Brewton that requires a continuous supply of various types

of timber for its operation. CCA has developed contracts

13a

with wood dealers to supply a certain amount of timber on

a weekly basis. Those dealers, in turn, contract with wood

suppliers, such as Littles, to deliver the wood to CCA.

For several years Littles has been interested in

becoming a wood dealer, and has expressed his interest in

CCA on several occasions. According to Littles, the last

time he approached CCA about a wood dealership was in

June of 1989 when he spoke with Don Heath, CCA’s

procurement manager. Although it is disputed whether or

not CCA has directly rejected Littles’ offer, it is CCA’s

position that Littles is not qualified to be a wood dealer. In

October 1989, Littles filed the instant action alleging that

CCA refused to contract with him because of his race.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

CCA contends that it is entitled to summary

judgment for two reasons: (1) plaintiffs class is barred by

the statute of limitations and (2) plaintiff cannot prove, by

either direct or circumstantial evidence, that CCA

intentionally discriminated against him. In response,

plaintiff denies that his claim is barred by the statute of

limitations and argues that he can prove discrimination not

only by direct and circumstantial evidence, but also by

proving that the defendant’s current practices perpetuate

past discrimination and by proving that the defendant’s

current selection criteria "lock in" past discriminatory

practices. Moreover, plaintiff seeks partial summary

judgment with respect to the last two issues because he

contends that there can be no dispute that defendant has

perpetuated past discrimination or that defendant’s

subjective hiring criteria lock in past discrimination.

Statute of Limitations

CCA contends that this action is due to be dismissed

because plaintiff failed to file suit within the applicable

limitations period. The statute of limitations governing suits

14a

under § 1981 is the same as that governing suits under 42

U.S.C 1983. Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. 656,

659 (1987). In Alabama that limitations period is two years.

See Owens v. Okure, 435 U.S. 235 (1989((holding that where

state has more than one personal injury statute of

limitations, the residual personal injury statute applies to §

1983 actions); Lufkin v. McCallum, (11th Cir. 1992)

(Alabama’s two-year statute of limitations for personal injury

actions governs § 1983 suite); accord Jones v. Preuit &

Mauldin, 876, 1480 (11th Cir. 1989((en banc). Likewise, the

same statute of limitations governs suits under § 1982.

Scheerer v.Rose State College, 950 F.2d 661, 664-65 (10th Cir.

1991); Allen v. Gifford, 462 F.2d 615, 615 (4th Cir.), cert,

denied, 409 U.S. 876 (1972); Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works