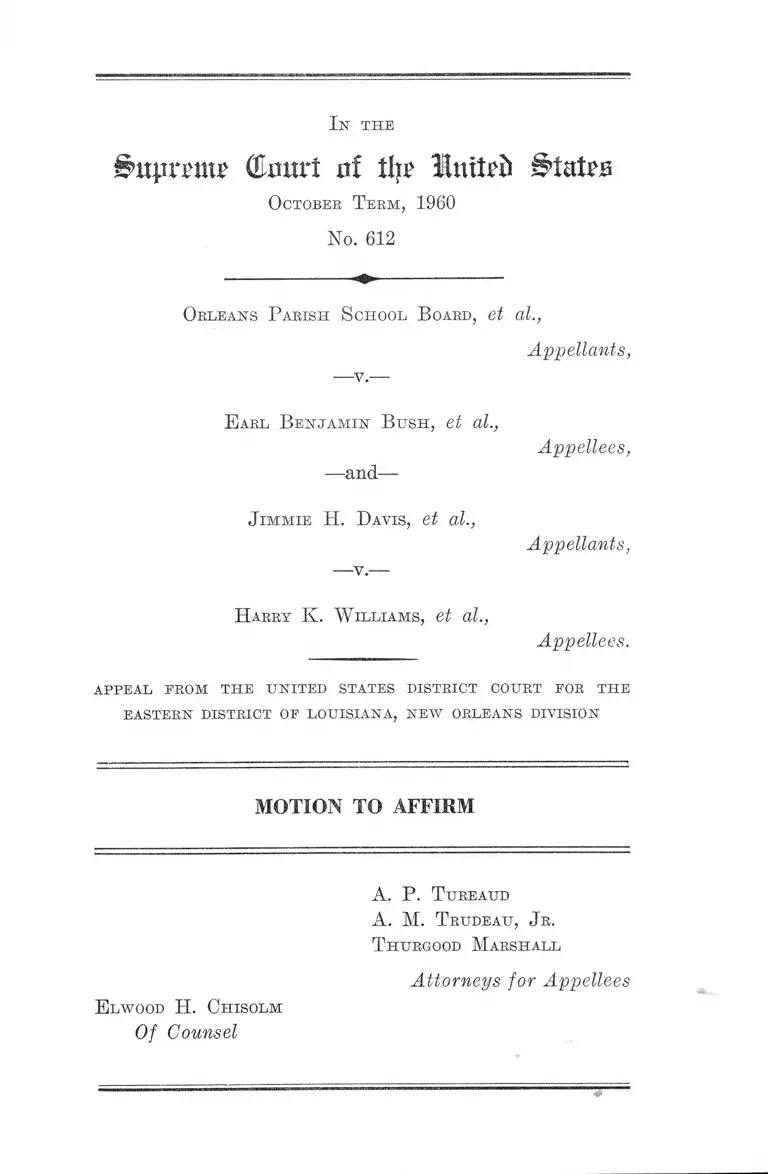

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush Motion to Affirm No. 612

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush Motion to Affirm No. 612, 1960. c81eee69-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b05797d0-c0ac-40f3-82c7-8093af4188a7/orleans-parish-school-board-v-bush-motion-to-affirm-no-612. Accessed January 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

^iipriw (tart nf tip? States

Octobeb Teem, 1960

No. 612

Orleans Parish School B oard, et al.,

Appellants,

— y .—

E arl B enjamin B ush, et al.,

—and—

Jimmie H. Davis, et al.,

Appellees,

Appellants,

Harry K. W illiams, et al.,

Appellees.

APPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

EASTERN D ISTRICT OF L O U ISIA N A , N E W ORLEANS DIVISION

MOTION TO AFFIRM

A. P. T ureaud

A. M. T rudeau, Jr.

T hurgood Marshall

Attorneys for Appellees

E lwood H. Chisolm

Of Counsel

In the

Supreme CUrntrt of tlje lutteft States

October Term, 1960

No. 612

Orleans P arish School B oard, et al.,

Appellants,

-v -

E arl B enjamin B ush, et al.,

—and—■

J immie H. Davis, et al.,

Harry K. W illiams, et al.,

Appellees,

Appellants,

Appellees.

a p p e a l p r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r t e o r t h e

EASTERN DISTRICT OE L O U ISIA N A , N E W ORLEANS DIVISION

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Appellees move to affirm the judgment below on the

ground that the questions presented for decision in the

cause are manifestly so unsubstantial as not to need further

argument.

Opinion Below

The opinion and judgment here on this appeal are re

ported at 187 F.Supp. 42.

2

Questions Presented

For the purposes of this motion, appellees adopt the

“ Questions” as presented by appellants at pages 5-7 of

their Jurisdictional Statement.

Statement of the Case

Other aspects of the New Orleans public schools litigation

have been brought here this Term and earlier. See Orleans

Parish v. Bush, No. 589, October Term 1960; United States

v. Louisiana, 5 L.ed. 2d 245; Orleans Parish School Board

v. Bush, 242 F.2d 156 (1957), cert, denied, 354 U.S. 921;

252 F.2d 253 (1958), cert, denied, 356 U.S. 969.

The instant appeal follows from proceedings intiated on

August 16, 1960, by the Bush appellees on motions to add

the Governor and Attorney General of Louisiana as parties

defendant, for leave to file a verified supplemental com

plaint, and for a preliminary injunction enjoining enforce

ment of a state court injunction issued against the Orleans

Parish School Board on the Attorney General’s applica

tion as well as restraining him and the Governor from

taking any further action to prevent the School Board from

desegregating public schools in compliance with orders

previously entered by the District Court. On the following

day, the Williams appellants by verified complaint brought

suit for injunctive relief against the Governor, a state

judge, other state officials and the School Boards in addi

tion to the appellants, claiming that the aforementioned

state court injunction was in the teeth of the District

Court’s desegregation order and assailing the unconstitu

tionality of a spate of state laws which specifically or

generally provided for the maintenance of racial segrega

tion in public schools.

3

Thereafter, on August 17, the District Court ordered the

addition of the Governor and Attorney General as parties

defendant and granted leave to file the supplemental com

plaint in Bush. A statutory three-judge District Court was

convened because the constitutionality of state legislation

had been assailed; and, since a preliminary injunction was

also moved for in Williams, both motions were consolidated

and set for hearing on August 26, 1960, at which no oral

testimony was to be taken and the record would be made

on affidavits and other documents.

The Attorney General appeared at the hearing, repre

senting himself and the State Treasurer (Tr. 4) plus the

State Superintendent of Schools (Tr. 23). In both Bush

and Williams he filed motions to dismiss for lack of juris

diction, for failure to state a claim on which relief could

be granted, for a more definite statement, motions for con

tinuance (each accompanied with supporting memoranda)

as well as answers and a trial brief (Tr. 25-28). He also

filed in Bush a motion to drop himself and the Governor

as parties defendant (Tr. 26); and, in Williams, he moved

to make District Judge Wright an additional defendant

(Tr. 27).

Moreover, the following documents and affidavits were in

troduced by the Attorney General: a certified copy of the

Executive Order by which the Governor took over operation

of the New Orleans public schools (Tr. 29); the affidavits of

a state tropper and three employees in the Governor’s of

fice, relating to the manner in which the Governor was

served (Tr. 30); the affidavits of the Superintendent of the

Orleans Parish Public Schools, two Assistant Superin

tendents, the Director of Research and Director of Person

nel— each alleging that compliance with the District Court’s

desegregation order would adversely effect the operation

of the local school systems (Tr. 30); and three affidavits by

4

the Attorney General, himself, relating to the pleadings

served upon him, the status of the state court action which

he initiated against the School Board and his contention

that Judge Wright was an “ interested party” (Tr. 29-30).

The School Board and Superintendent filed motions to

dismiss and supporting memoranda in Williams (Tr. 31-

32); and the state judge also filed both a motion to dismiss

and a motion to quash service in Williams (Tr. 32).

Thereafter, the Bush appellees introduced certified copies

of the Attorney General’s petition in the state court pro

ceeding against the School Board and the opinion and

judgment entered there (Tr. 34). The Williams appellees

introduced an affidavit, showing the irreparable injuries

which they and their children would suffer if the public

schools were closed by defendants (R. 42). This affidavit

was received over the Attorney General’s objections; and

it was at this juncture that he withdrew from the courtroom,

stating, “ I am not going to stay in this den of iniquity”

(Tr. 40).

After he left, the District Court granted his staff per

mission to withdraw (Tr. 41); it then sustained the School

Board’s objections to certain newspaper clippings which

the Williams appellees sought to introduce (Tr. 42-43),

heard oral argument by counsel for appellees (48-52,

54-69) and the School Board (Tr. 69-71) before taking the

case under advisement (Tr. 71).

The only oral testimony taken was introduced before

the Attorney General withdrew: it related to the Marshalls’

service upon the Governor (Tr. 10-12, 13-14, 16-21) and

the Court ruled that the Attorney General could not cross-

examine since he did not represent the person on whose

behalf sei’vice was in issue (Tr. 14).

On August 27, 1960, the District Court filed an opinion

and judgment for appellees (Appellants’ App. A and B,

5

pp. 1-4, 5-12; 187 F.Supp. 42). Notice of appeal was filed

by appellants on August 30 and this Court denied their

application for a stay on September 1.

Reasons for Granting the Motion

The congeries of questions presented by the Attorney

General and Treasurer of Louisiana falls far short of any

substantial merit. Indeed, by failing to treat most of them,

especially those that concern the legislative, executive, and

judicial acts which the District Court held unconstitutional

and enjoined the enforcement thereof, appellants admit

the correctness of the judgment below. Such admission,

we submit, is compelled under a long line of decisions which

dealt with similar efforts to frustrate desegregation in

Little Rock and Norfolk, see Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1;

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F.Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark. 1959),

affirmed sub nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197; James

v. Almond, 170 F.Supp. 331 (E.D. Va. 1959), dismissed

359 U.S. 1006; James v. Duckworth, 170 F.Supp. 342 (E.D.

Va. 1959), affirmed 267 F.2d 224 (4th Cir. 1959), cert,

denied 361 U.S. 835; Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d 797

(8th Cir. 1958), cert, denied 358 U.S. 829; Thomason v.

Cooper, 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958), and in New Orleans,

too. See United States v. Louisiana, 5 L.ed. 2d 245; Orleans

Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F.2d 156 (1957), cert,

denied 354 U.S. 921; Id., 268 F.2d 78 (1959).

The “major questions” treated by appellants, the ones

which they contend “ are clearly substantial” (Juris. State

ment, p. 25), present the following claims: (1) that the

judgment below violates the Eleventh Amendment; (2)

that the District Court had no jurisdiction in the premises

inasmuch as a previous order was on appeal to the Court

of Appeals; (3) that they have not had a fair trial and

their day in court.

6

None of these claims, we submit, is so substantial as to

require plenary consideration: the first misconceives the

facts and the law; the second understates the law; and the

record belies the third.

1. The thrust of appellants’ first claim is that the fourth

paragraph of the judgment below, ordering the Orleans

Parish School Board to comply with the order dated May

16, 1960, requiring desegregation beginning with the first

grade, compels affirmative state action which falls within

the Eleventh Amendment’s prohibition of suits against the

state.

Laying to one side the fact that this paragraph of the

judgment commands nothing of the appellants, themselves,

and assuming arguendo their standing to assert the claim

of the party adversely affected, appellees say that the

protection of individual rights under the Constitution by

enjoining state officers from taking action beyond the

scope of their legal powers does not trespass on what is

forbidden by the Eleventh Amendment. The difference

between enjoining the exercise of discretion by state offi

cers and enjoining their violation of constitutional rights

under authority of their office was established definitively

over a half-century ago in Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123,

159-160, and it has been followed ever since by this Court.

See, e.g., Lane v. Watts, 234 U.S. 525, 540; Philadelphia

Co. v. Stimson, 223 U.S. 605; Truax v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33;

Public Service Co. v. Corboy, 250 U.S. 153; Colorado v. Toll,

268 U.S. 228, 230; Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378. See

also Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, supra, 242 F.2d

156, 160-161, cert, denied 354 U.S. 921; School Board of

City of Charlottesville v. Allen, 240 F.2d 59, 62-63 (4th

Cir. 1956).

Finally, as the case last cited pointed out, at page 63:

While no such question was raised in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 . . . and 349 U.S.

7

294, . . . the question was inherent- in the record in

those cases; and it is not reasonable that the Su

preme Court would have directed injunctive relief

against school boards acting as state agencies, if no

such relief could be granted because of the provisions

of the Eleventh Amendment to the Constitution.

2. Appellees cannot gainsay that, at the time parties

were added and the supplemental complaint was allowed

in Bush, the Orleans Parish School Board had noticed an

appeal from the District Court order dated May 16, 1960,

requiring desegregation beginning with the first grade in

New Orleans. Neither do appellees deny that one general

rule of federal procedure is that the filing of notice of

appeal transfers jurisdiction of the cause from the Dis

trict Court to the Court of Appeals. However, we say

that it is only “ jurisdiction over the particular cause or

matter which is transferred by perfection of an appeal,

not the total jurisdiction of the District Court over every

thing related to or connected with it, and especially not to

take action compatible with the appeal.” 13 Cyc. Fed. Proc.

§62.04, p. 683.

Clearly the action taken by the court below on motion

of the Bush appellees was compatible with the appeal. It

did not adjudicate substantial rights directly involved in

the appeal of the School Board or alter the parties to

and judgment involved, rather the orders issued against

the Governor and these appellees—the Attorney General

and Treasurer—were made to prevent acts which would

have made the School Board’s appeal moot. In such cir

cumstances, as this Court held in Newton v. Consolidated

Gas Co., 258 U.S. 165, 177: “ Undoubtedly, after appeal,

the trial court may, if the purpose of justice requires,

preserve the status quo until decision by the appellate

court [citing Havey v. McDonald, 109 U.S. 150, 157].” See

Grant v. Phoenix Mutual Life Ins. Co., 121 U.S. 118;

8

Shinholt v. Angle, 90 F.2d 297 (5th Cir. 1937); Rule 8,

Rules of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit. Cf. Rule 33, Rules of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

In addition, perfection of the appeal by the Orleans

Parish School Board obviously did not deprive the Dis

trict Court of jurisdiction over the separate suit brought

by the Williams appellees. Nor would it have prevented

an ancillary suit by the Bush appellees for the same relief

as that granted by the May 16, 1960 judgment. Cf. Natal

v. Louisiana, 123 U.S. 516, 518.

3. The record clearly demonstrates the lack of merit,

if not the frivolousness, of appellants’ insistence that they

were denied a fair and impartial trial or any other pro

cedural due process (see the Statement of the Case, supra).

Considering all the circumstances, it shows that no sub

stantial right was denied; that the District Court wisely

excluded ill-advised cross-examination and other matter;

and that the Attorney General unwisely talked too much

before he and his staff withdrew from the District Court.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, considering the foregoing reasons, the ques

tions presented by appellants are manifestly unsubstantial

and the motion to affirm should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

A. P. T ttreatjd

A. M. Trudeau, Jr.

T hurgood M arshall

E lwood H. Chisolm

Of Counsel

Attorneys for Appellees

c«gff|p|g&> 3 8