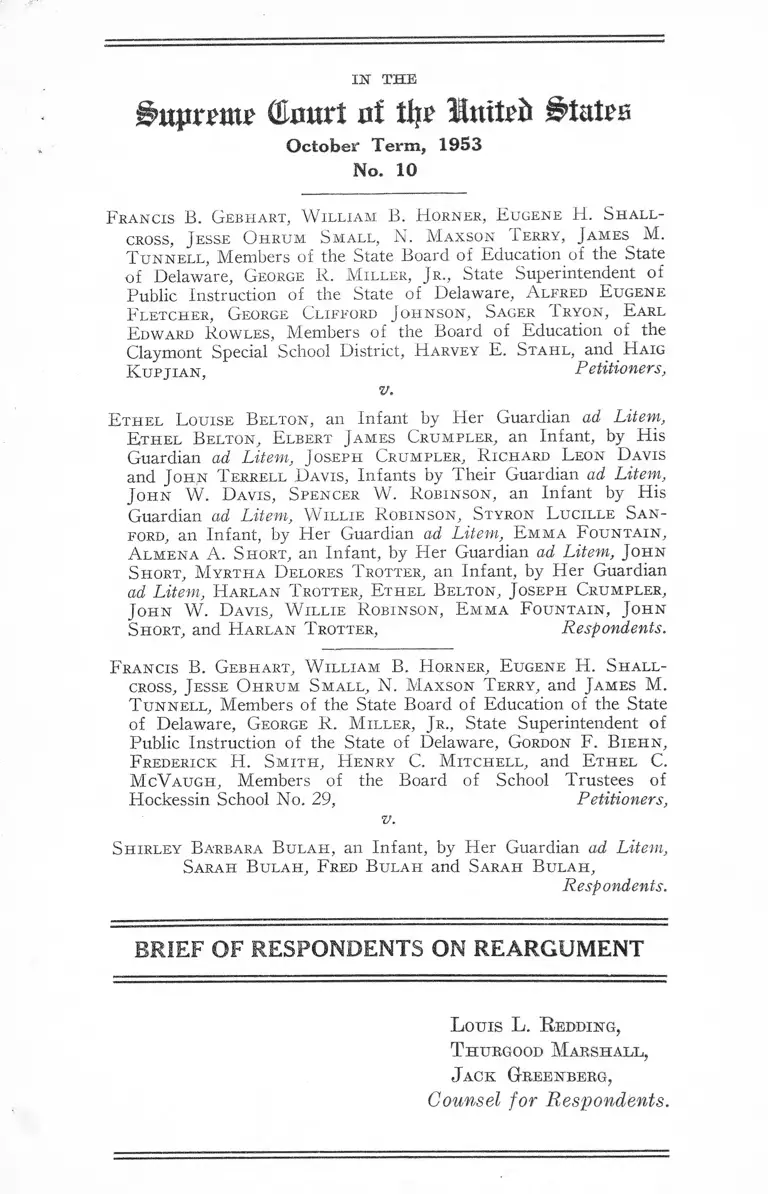

Gebhart v. Belton Brief of Respondents on Reargument

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gebhart v. Belton Brief of Respondents on Reargument, 1953. 72e406f8-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b0608907-81dc-4df1-83a2-b0884a7fa6a4/gebhart-v-belton-brief-of-respondents-on-reargument. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

(Enurt of tlĵ Bltttteft States

O ctober Term, 1953

No. 10

F ra n c is B. G eb h a r t , W il l ia m B. H orner , E u g en e H . S h a l l -

cross, J esse O h r u m S m a ll , N. M axson T erry, J a m es M.

T u n n e l l , Members of the State Board of Education of the State

of Delaware, G eorge R . M ille r , J r ., State Superintendent of

Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, A lfred E ugene

P'l etc h er , G eorge Clifford J o h n s o n , Sager T ryon , E arl

E dward R ow les , Members of the Board of Education of the

Claymont Special School District, H arvey E. S t a h l , and H aig

K u p j ia n , P etitioners,

v.

E t h e l L o u ise B elto n , an Infant by Her Guardian ad Litem,

E t h e l B elto n , E lbert J am es Cr u m pl er , an Infant, by His

Guardian ad Litem, J o seph Cr u m pl er , R ic hard L eon D avis

and J o h n T errell D avis, Infants by Their Guardian ad Litem,

J o h n W. D avis, S pen c er W. R o b in so n , an Infant by His

Guardian ad Litem, W il l ie R o b in so n , S tyron L u c ille S a n

ford, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem, E m m a F o u n t a in ,

A l m e n a A. S hort , an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem, J o h n

S hort , M y r th a D elores T rotter, an Infant, by Her Guardian

ad Litem, H arlan T rotter, E t h e l B elto n , J oseph Cr u m pl er ,

J o h n W. D avis, W il l ie R o b in so n , E m m a F o u n t a in , J o h n

S hort , and H arlan T rotter, Respondents.

F rancis B. G eb h a r t , W il l ia m B. H orner, E u g e n e H. S h a l l -

cross, J esse O h r u m S m a ll , N. M axson T erry, and J am es M.

T u n n e l l , Members of the State Board of Education of the State

of Delaware, G eorge R. M ille r , J r ., State Superintendent of

Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, G ordon F . B ie h n ,

F rederick H. S m it h , H enry C. M it c h e l l , and E t h e l C.

M cV a u g h , Members of the Board of School Trustees of

Hockessin School No. 29, Petitioners,

v.

S h ir l e y B arbara B u l a h , an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem,

S arah B u l a h , F red B u la h and S arah B u l a h ,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS ON REARGUMENT

Louis L. R edding,

T hurgoob Marshall,

J ack Greenberg,

Counsel for Respondents.

I N D E X

PAGE

Preliminary .................................................................. 2

Pertinent Delaware History ........................................ 4

Conclusion .................................................................... 12

Table of Cases Cited

Helvering v. Lerner Stores, 314 U. S. 463 .................. 2

Langnes v. Green, 282 U. S. 531 .................................. 2

Parker v. University of Delaware, — Del. — 75 A.

2d 225 ................ 12

Statutes Cited

2 Laws of Delaware, Cbapt. C V .................................. 7

2 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. CXLV, Revised Code of

Delaware, 1852, Chapt. CVII .................................. 4

2 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. CXLV, Sec. 8 ................ 4

7 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. X C IX ............................. 7

12 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 126, adopted January 3,

1861 ............................................................................ 5

12 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 296 ................................ 9

12 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 336 ................................ 5

12 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 592 ................................ 6

13 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 81.................................. 6

13 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 555 ................................ 7

13 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 256 ................................ 6

14 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 612 ................................ 7

14 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 613 ................................ 7

15 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 50, passed March 25,

1875 ............................................................................ 9

15 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 48, passed March 24,

1875 ............................................................................ 10

16 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 362 ............................... 10

II

Other Authorities Cited

PAGE

Biennial Message of Governor Robert J. Reynolds,

Jan. 3, 1893, New York Public Library, Document

P.133613 ..................................................................... 11

Conrad, Henry C.: History of the State of Delaware

(1908) pp. 195, 205 .................................................... 5

Delaware—A Guide to the First State (Viking Press,

1938), pp. 8, 52 .......................................................... 4,5

House Journal—State of Delaware, 1867, pp. 10-21 .. 6

Inaugural Address of Robert J. Reynolds, Governor of

the State of Delaware, Jan. 20, 1891, New York Pub

lic Library Document P. 12285 ............................... 10

Miller, George R. Jr.: “ Adolescent Negro Education

in Delaware”, pp. 175, 177 .......................................11,12

Powell, Walter A .: A History of Delaware (The Chris

topher Publishing House, Boston, 1928), pp. 252,

253, 261, 262, 419 ........................................................ 5, 8

Reed, H. Clay: Delaware—A History of the First

State, pp. 571, 586 .................................................... 4,, 8

Report of the Delaware Association for the Moral

Improvement and Education of the Colored People

of the State—February, 1868) (The Commercial

Press of Jenkins & Atkinson, Wilmington, 1868), New

York Public Library, Document No. P. 50318, Ap

pendix No. 2 .............. ................................................ 8

Robertson & Kirkham, Jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court of the United States (1951 ed.) §428 ............. 2

Scharf, John Thomas: History of Delaware—1609-1888

(1888), pp. 329, 330, 445, 446 ...............................4, 5, 8, 9

Strayer, Engelhart & Hart: “ Survey of the Public

Schools of Delaware” ............................................... 11

Strayer, Englehardt & H art: Service Citizens of

Delaware, Bulletin, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1919), p. 214 . . . . 11

Woodson, Carter G.: Education of the Negro Prior to

1861, 2nd ed. (Washington, D. C. 1919), p. 101 . . . . 8

I N T H E

ilwprpmp Qkmrt of tljp llttitpii States

October Term, 1953

No. 10

----- --------------------o-------------------------

F rancis B. G eb h a r t , W il l ia m B. H orner , E u gene H . S h a l l -

cross, J esse O h r u m S m a ll , N. M axson T erry, J am es M.

T u n n e l l , Members of the State Board of Education of the State

of Delaware, G eorge R. M ille r , J r ., State Superintendent of

Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, A lfred E ugene

F l etc h er , G eorge Clifford J o h n s o n , S ager T ryon , E arl

E dward R ow les , Members of the Board of Education of the

Claymont Special School District, H arvey E. S t a h l , and H aig

K u p jt a n , Petitioners,

v.

E t h e l L o u ise B elto n , an Infant by Her Guardian ad Litem,

E t h e l B elto n , E lbert J am es Cr u m pl er , an Infant, by His

Guardian ad Litem, J oseph Cr u m pl er , R ichard L eon D avis

and J o h n T errell D a vis , Infants by Their Guardian ad Litem,

J o h n W. D a vis , S pencer W. R o b in so n , an Infant by His

Guardian ad Litem, W il l ie R o b in so n , S tyron L u c ille S a n

ford, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem, E m m a F o u n t a in ,

A lm e n a A . S hort , an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem, J o h n

S hort , M yrth a D elores T rotter, an Infant, by Her Guardian

ad Litem, H arlan T rotter, E t h e l B elto n , J oseph Cr u m pl e r ,

J o h n W . D avis, W il l ie R o b in so n , E m m a F o u n t a in , J o h n

S hort , and H arlan T rotter, Respondents.

F rancis B. G eb h a r t , W illia m B. H orner , E u g en e H. S h a l l -

cross, J esse O h r u m S m all , N . M axson T erry, and J am es M.

T u n n e l l , Members of the State Board of Education of the State

of Delaware, G eorge R. M ille r , J r., State Superintendent of

Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, G ordon F, B ie h n ,

F rederick H. S m it h , H enry C. M it c h e l l , and E t h e l C.

M cV a u g h , Members of the Board of School Trustees of

Hockessin School No. 29, Petitioners,

v.

S h ir l e y B arbara B u l a h , an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem ,

S arah B u l a h , F red B u l a h and S arah B u l a h ,

Respondents.

------------------------ o------ -------------------

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS ON REARGUMENT

2

Respondents, desiring not to repeat the thorough analy

sis of the issues presented by petitioners in Nos. 1, 2 and 4,

joined in the brief of petitioners in those cases. However,

the brief for petitioners in this case has raised certain

matters peculiar to Delaware and to the Delaware litiga

tion before this Court, and it is to them that respondents

briefly make their answer. Concerning matters common to

Nos. 1, 2, 4 and 10 they continue to take the same position

as petitioners in Nos. 1, 2 and 4.

Preliminary

In a section entitled “ Preliminary,” petitioners have

taken the position that the validity of racial segregation in

education is not at issue in this case. That is not so. The

issue was raised and preserved at each and every stage of

the proceeding : by complaint, by evidence, on appeal to

the Supreme Court of Delaware and in response here. Peti

tioners take the position that since there was a cross-appeal

in Delaware raising the issue, but none here, respondents

have abandoned it. That is incorrect. In the Supreme

Court of Delaware the issue was raised by cross-appeal

because counsel for respondents believed that that was the

proper way to raise it there. In this Court, under the

doctrine of Helvering v. Lerner Stores, 314 U. S. 463, 466

and Langnes v. Green, 282 U. S. 531, 535, 538, it would be

superfluous to also raise the matter by a cross-appeal.1

Respondents may urge this Court to affirm on grounds

other than those embraced by the Court below, and they

have done so in timely manner. A cross-appeal could not

pray more.

1 See also, Robertson & Kirkham, Jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court of the United States (1951 ed.) §428.

Respondents of course recognize that this Court may

affirm on other and narrower grounds 2 presented by the

opinions below, but they urge that on this record and the

finding of the Chancellor, and as a matter of law, complete

relief in equity can only be given by a decree which reaches

the ultimate question. Otherwise respondents and their

successors will continue to attend school under the cloud

of the State’s avowed threat to segregate once more when

“ equality” in facilities is achieved; frequent litigation will

harass and burden both sides; and the already adjudicated

harmful effects of racial segregation will be intermittently

inflicted on respondents.

Petitioners, at pages 6-11 of their brief, assert that the

doctrine of white superiority and the inferior educational

opportunities for the Negro flowing from that doctrine

were abandoned with the ratification by Delaware, in 1901,

of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

We say that inferior educational opportunities for the

Negro are shown by all the historical evidence to have con

tinued down to the time of the facts concerning which these

respondents complained. Such inferior treatment is of a

piece, we submit, with the ante- and post-bellum attitude

and practice concerning Negroes set forth in the consoli

dated brief of petitioners in Nos. 1, 2, and 4, and respond

ents in No. 10, pages 50-65.

2 In detail, the narrow grounds upon which this Court may affirm

are set forth in respondents’ earlier brief No. 448, October Term,

1952, pp. 13-19.

4

Pertinent Delaware History

Bounded on the North by Pennsylvania and, on the

South and largely on the West, by Maryland, most of Dela

ware’s 110 miles of length is below the Mason-Dixon

boundary.3

In 1860, fewer than 10 per cent of the Negroes in Dela

ware were slaves, the large majority, approximately 90

per cent, being known as “ free colored persons.” 4 How

ever, these “ free” persons were not entitled to vote, be

appointed or elected to public office or give evidence in

criminal prosecutions, unless there was no competent white

witness. In a certain type of case a free Negro was abso

lutely disqualified as a witness against a white man.5

Under such restrictions, the rights given to free Negroes,

namely, “ to hold property, and to obtain redress in law or

equity” for injury to person or property,6 were less than

secure.

The attitude of Delaware toward Negroes is further

demonstrated by the fact that the popular vote for Lincoln

in the Presidential election in November, 1860, was the

third lowest among that for four candidates. John C.

3 Reed, H. Clay: Delaware—A History of the First State, p. 571;

Delaware—A Guide to the First State (Viking Press, 1938), p. 8.

4 Scharf, John Thomas: History of Delaware—1609-1888

(1888), p. 330, gives the 1860 census for Delaware as: white—

90,589; free colored—19,827; slaves—-1798, divided among the

counties as follows:

IV kite Free

Colored

Slave

New Castle 46,355 8188 254

Kent 20,330 7271 203

Sussex 23,904 4370 1341

5 2 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. CXLV, Revised Code of Dela-

zvare, 1852, Chapt. CV1I.

0 2 Lazes of Delaware, Chapt. CXLV, Sec. 8.

5

Breckinridge, of the Southern wing of the Democratic

Party, who espoused continuing and protecting the institu

tion of Negro slavery, polled a plurality, receiving almost

twice as many votes as did Lincoln.7 In 1861, President

Lincoln’s proposal for gradually emancipating the slaves,

with compensation to the slaveholders, failed of acceptance

in Delaware.8 * Early in 1861, in a letter 8 to the Governor

of Maryland, the Governor of Delaware stated he was

“ unable to say” whether the people of Delaware would be

governed by their “ interest” or their “ sympathy”. While

“ most all” of the State’s trade was with the North, “ A

majority of our citizens, if not in all three Counties, at

least in the two lower ones, sympathize with the South.”

Although, the same year, the Delaware General Assembly

declined an invitation to join the Southern states in seces

sion,10 on January 29, 1863, it adopted a joint resolution

stating, inter alia, “ That we do most emphatically con

demn, and in the name and on behalf of the people of Dela

ware, protest the Proclamation of Emancipation issued by

the President on the first instant * * V ’11

During the War of 1861-65 many Delawareans fought

for the Confederacy, although it should he noted that most

who entered armed service fought to preserve the Union.12

Beginning in February, 1865, and extending over a span

of eight years, a series of Delaware legislatures adopted

7 Conrad, Henry C .: History of the State of Delaware (1908),

p. 195; Scharf, op. cit., p. 329; Delaware—A Guide to the First

State, p. 52.

8 Conrad, op. cit., p. 205; Powell, Walter A .: A History of

Delaware (The Christopher Publishing House, Boston, 1928),

p. 262.

8 Powell, op. cit., pp. 252-253.

10 12 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 126, adopted January 3, 1861.

11 12 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 336.

12 Powell, op. cit., p. 261; Delaware—A Guide to the First State

p. 52.

6

a succession of joint resolutions manifesting deliberate

hostility toward the Civil War amendments to the federal

Constitution and various acts of Federal legislation im

plementing these amendments.

On February 8, 1865, the Delaware General Assembly

refused to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment.13 On Feb

ruary 16, 1866, it adopted a “ Joint Resolution on Federal

Relations, ’’ in which it condemned the Freedmen’s Bureau’s

extension to Delaware and “ interference” by the Federal

Government with civil justice in the States “ by extending

to the negro race rights and privileges for the enjoyment

of which they are not prepared either by nature or educa

tion” and “ which have been wisely denied them” by State

laws. It condemned “ attempts to patch” the Federal Con

stitution by “ acts erroneously termed amendments.” 14

On January 1, 1867, Governor Gove Saulsbury, in a

message15 to the legislature replete with strictures against

Negroes, declared that the laws of Delaware have “ wisely

denied the colored population certain rights and privileges

accorded to white people.” He sought to justify Delaware

laws which provided more severe criminal penalties for

Negroes than for whites. He requested the legislature to

reject the Fourteenth Amendment. The legislature did

that on February 7, 1867, in a resolution in which it ex

pressed “ unqualified disapproval” of the amendment and

there stated its refusal to ratify.16 On March 18, 1869,

the General Assembly in Delaware declared the Fifteenth

Amendment “ an attempt to establish an equality not sanc

tioned by the laws of nature or of God,” stated its un

qualified disapproval of the measure and refused to ratify

13 12 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 592.

14 13 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 81.

15 House Journal—State of Delaware, 1867, pp. 10-21.

16 13 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 256.

7

it.17 On April 11, 1873, two joint resolutions were adopted.

One, by way of condemning the “ Supplemental Civil

Rights Bill,” proclaimed “ unceasing opposition to making-

negroes eligible to public offices, to sit on juries, and to

their admission into public schools where white children

attend.” 18 The other denounced the “ invasion” of the

State system of local self-government by a Federal act

enforcing the right to vote and stated that “ it is essential

that the government of the States and of the Union shall be

entrusted to * * * white men.” 19

The attitude of Delaware shown to be hostile to Negro

rights generally was no less inimical to the Negro’s oppor

tunity for education. Initial impetus to a public school

system in Delaware came from the statute passed February

9, 1796,20 which, out of fees accruing to 1806 (later extended

to 1820) from marriage and tavern licenses, created a

“ fund for establishing schools” 21 for “ the purpose of in

structing the children of the inhabitants” of Delaware.

This statute made no reference to color. If this was an

inadvertent omission, before any schools were actually

established, it was cured by the act of February 12, 1829,22 *

which provided for divisions into school districts and for

the establishment by voters of district schools which “ shall

be free to all white children” of the district. Although

Negroes had long been inhabitants of Delaware28 and as

has been seen, sometimes were “ free”,24 no provision was

then undertaken by the State for their education.

17 13 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 555

18 14 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 612.

19 14 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 613.

20 2 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. CV.

21 Salaries of the judiciary were first deducted, the residue going

to schools.

22 7 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. XCIX.

28 Reed, op. cit., p. 571.

24 Supra, page 4.

8

The public school system comprehended by the 1829

law was most rudimentary. Sometimes the district tax to

support the school was voted down for several successive

years and there would be no school, for the State made

appropriations only of an equivalent of the amount raised

by local district taxation. There was no centralized con

trol, no standardization.25 This inefficient non-compulsory

idea continued until 1861.

Meanwhile, private efforts had started schools for

Negroes. As early as 1801, according to one authority, a

school was established in Wilmington for the education of

Negroes.26 In 1824, The African School Society of Wil-

ming'ton was founded.27 On December 27, 1866, the Dela

ware Association for the Moral Improvement and Educa

tion of the Colored People of the State was formed in

Wilmington. Its first annual report,28 published in 1868,

shows that it immediately began the establishment of

schools for Negroes and in January, 1868, had in operation 25 * 27 28

25 Scharf, op. cit., p. 445.

20 Woodson, Carter G .: Education of the Negro Prior to 1861,

2nd ed. (Washington, D. C., 1919), p. 101.

27 Reed, op. cit., p. 586; Powell, op. cit., 419.

28 Report of the Delaware Association for the Moral Improve

ment and Education of the Colored People of the State—February,

1868) (The Commercial Press of Jenkins & Atkinson, Wilmington,

1868), New York Public Library, Document No. P 50318. See

Appendix No. 2 of this Report, from which the following is quoted:

“This large class of our population [Negroes] are wholly ex

cluded from the benefits of our system of public education,

although not exempt from taxation, in some shape, for the

public schools. While legislation thus closes against them the

avenues of knowledge and improvement, it has visited in

their case the crimes and offences which naturally flow from

ignorance and degradation with excessive and cruel penalties.

Persistence in such glaring injustice must be attended with

grave accountability, for in the Providence of a righteous God,

every wrong brings sooner or later its retribution.”

9

twenty-two such schools throughout the State. The report

of the President of this Association shows that the program

of the Association was laid before Governor Saulsbury,

who gave hearing to it but differed from the President and

Managers of the Association “ in judgment as regards the

capacity of the colored man for Education.” In view of

the known exclusion of Negroes from the benefits of the

public school fund and the known hostile attitude of the

Governor of the State, this excerpt from the report has

particular significance:

“ Not only from its central location; but also as

the seat of Government of the State, the Managers

selected Dover as one of the first points to be se

cured ; and they planted, under the eye of the Execu

tive and Legislative authorities, what they hope will

prove, in time, a Model school. ’ ’

In 1861, the General Assembly strengthened the public

school law by requiring the school committee in each dis

trict to raise for support of the district school a specified

minimum amount, irrespective of the action of the voters.

The voters might, if they chose, raise a larger amount.29

The original school fund created under the law of 1796 was

augmented in 1867 by an act increasing the sources of state

revenue supplying the fund. The public school system was

further strengthened in 1875 by an act creating a State

Board of Education and the office of State Superintendent

of Free Schools.30 None of these measures applied to

Negroes. The State government had not modified the atti

tudes evinced in the revealing series of resolutions re

ferred to above. In Delaware, the Fourteenth Amendment

remained unratified.

29 12 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 296; Scharf, op. cit., p. 446.

30 15 Lazvs of Delaware, Chapt. 50, passed March 25, 1875.

10

When in 1875, a statute 81 authorized the assessment and

collection of taxes of thirty cents per $100 on the property

of Negroes, it provided for the ultimate turning over of

these funds to the private Delaware Association mentioned

above for distribution among Negro schools. The presump

tion arising from the statute and the incomplete historical

evidence is that the schools intended were those thereto

fore erected or maintained by the private initiative of the

Association, for certainly no schools had then been pro

vided for Negroes by the State. When in 1881, the General

Assembly appropriated the first money, $2,400, to be dis

tributed among the schools for Negroes, it was this same

private Association to which the State turned to allocate

and disburse the funds.82

The history of the public school system in Delaware

does not show unbroken progression toward betterment.

It appears that somewhere between 1875 and 1891, the office

of State Superintendent, with its opportunity for effectuat

ing uniform state-wide educational procedures, curricula

and standards, was abolished. We find the inaugural ad

dress of the Governor, on January 20, 1891,83 submitting,

“ for the consideration of the General Assembly, the

expediency of creating a State Superintendency of

Public Schools in addition to the existing County

Superintendency, the object being to harmonize our

school system and prevent objectionable features

arising from county differences in the general plan

of instruction and school regulation. To the State

Superintendent also should be entrusted the super

vision of the colored schools and the responsible

administration of the funds appropriated for their

support. ’ ’ 31 32 33

31 15 Lazvs of Delaware, Chapt. 48, passed March 24, 1875.

32 16 Laws of Delaware, Chapt. 362.

33 “Inaugural Address of Robert J. Reynolds, Governor of the

State of Delaware’', Jan. 20, 1891. New York Public Library,

Document P. 12285.

11

Even at this date, 1891, the Negro schools were being

operated without State guidance or surveillance.

We find the same Governor, in his biennial message

two years later, referring to failure of progress in the

colored schools and stating that “ it results very much from

the fact that the laws regulating the schools of the colored

people * * * are crude and imperfect. ’ ’ 84 * * * 88

Even the most cursory comparison of educational oppor

tunity provided by the State of Delaware for whites and

Negroes demonstrates that not only before 1897, but always,

Negro education has suffered from constitutional and statu

tory enactments which are the heritage of a slave system.

Thus:

(a) In 1897, a constitutional provision was adopted

which required that Negroes be excluded from schools

attended by whites.

(b) As late as 1919, after an exhaustive survey of Dela

ware schools by eminent educational administrators, it was

concluded that schools for Negroes were inferior to those

for whites.35

(c) Although “ In 1921, philanthropy in the guise of

Pierre duPont made possible the building of 87 Negro

schools” and “ It is interesting to contemplate what the

status of Negro schools would have been had it not been

for this philanthropic gesture, ” 38 as late as 1943 equality

84 “Biennial Message of Governor Robert J. Reynolds’’, Jan. 3,

1893, New York Public Library, Document P. 133613.

88 Strayer, Englehardt & Hart: “Survey of the Public Schools

of Delaware”—Service Citizens of Delaware, Bulletin, Vol. 1, No. 1

(1919), especially p. 214.

88 Miller, George R., J r . : “Adolescent Negro Education in Dela

ware”, p. 175. (The author of this doctoral dissertation, filed in the

Library of Congress, is State Superintendent of Public Instruction

in Delaware and a petitioner here.)

12

in education for Negroes in Delaware, in the words of a

petitioner here, had “ not yet been reached.” Indeed, at

that time, there were “ no complete 4-year high schools for

Negroes south of Wilmington,” although “ No white child

in the State [was] faced with this situation.” 37

(d) Still later, in 1950, it was judicially determined that

the Delaware State College for Negroes was “ woefully

inferior” to comparable facilities set aside for white stu

dents at the University of Delaware. Parker v. University

of Delaware,----- Del.------ , 75 A. 2d 225.

(e) In the instant cases both courts belowr held that there

wras inferiority in public school facilities for Negroes, as

compared with those for white children in the communities

involved.

The State now asserts (Petitioners’ Brief, p.10) that

the State constitutional and statutory provisions assailed

by respondents are “ in the cause of education of negroes,

a long stride forward.”

The respondents, however, do not assert a claim merely

to “ a long stride forward,” although they concede that

realization of their claim would entail such a stride. Re

spondents assert a constitutional right: the right to equal

protection of the laws, and they assert that education under

a system which is a heritage of slavery has borne, and must

always bear, the mark of slavery.

Conclusion

In this brief in answer, we have addressed ourselves

to certain contentions made by petitioners which were not

dealt with in the consolidated brief, in which we have joined.

The question of the history of Delaware which was raised

37 Id., at p. 177.

13

by petitioners presents in particular form one of the rea

sons for affirmance of the judgment below.

Wherefore, for the reasons set forth in the consoli

dated brief and herein, we respectfully urge that the

judgment below be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Lotus L. R edding,

T hurgood Marshall,

J ack Greenberg,

Counsel for Respondents.

Supreme P rinting Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y., BEekman 3 - 2320