Griffin v. Maryland Brief and Record Extract of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Griffin v. Maryland Brief and Record Extract of Appellants, 1960. 339a1bbf-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b06e1312-4638-4ab9-b43f-d6d184393ffb/griffin-v-maryland-brief-and-record-extract-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

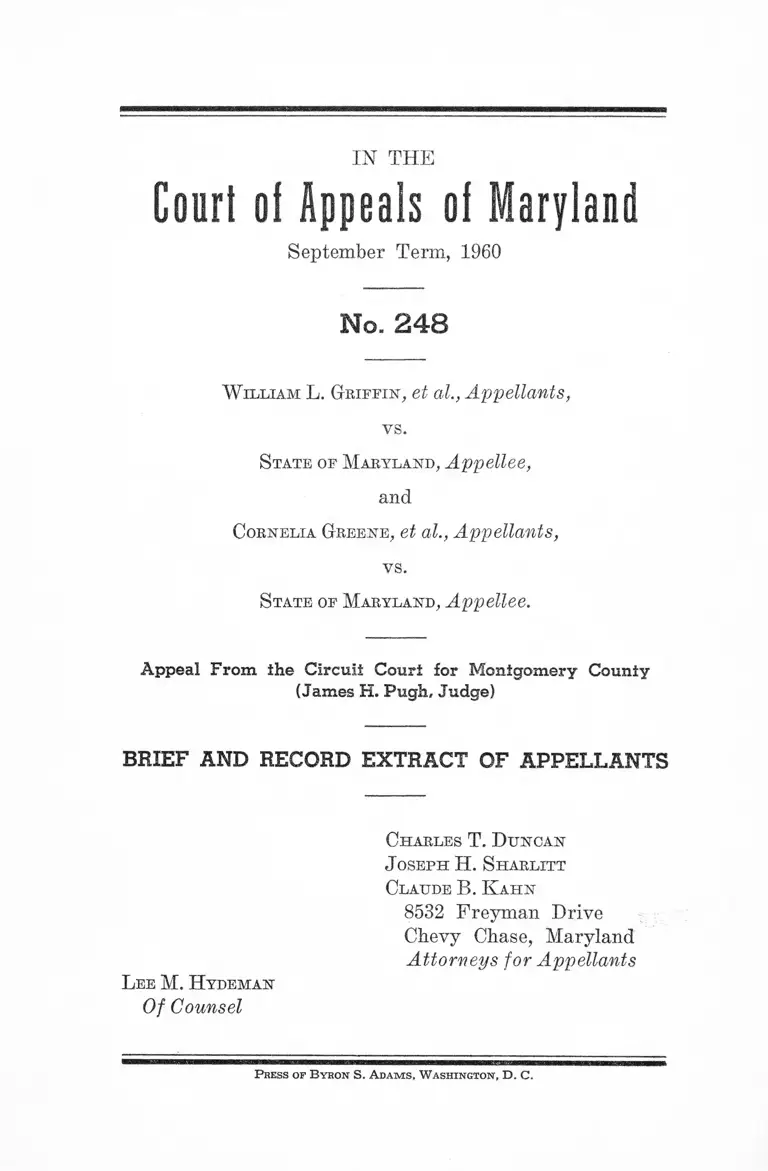

IN THE

Court of Appea l s of M a r y l a n d

September Term, 1960

No. 2 4 8

W illiam L . Gr iffin , et al., Appellants,

vs.

S tate of Maryland, Appellee,

and

Cornelia Greene, et al., Appellants,

vs.

S tate of Maryland, Appellee.

Appeal From the Circuit Court for Montgomery County

(James H. Pugh, Judge)

BRIEF AND RECORD EXTRACT OF APPELLANTS

Charles T. D uncan

J oseph H. S harlitt

Claude B. K ahn

8532 Freyman Drive

Chevy Chase, Maryland

Attorneys for Appellants

L ee M. H ydeman

Of Counsel

P ress o f B yro n S. A d a m s , W a s h in g t o n , D . C.

INDEX

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Statement of the Case ............................................... 1

Questions Presented ..................................................... 3

Statement of Facts ....................................................... 4

Summary of Arguments .............................................. 7

Argument ....................................................................... 8

I . T h e R equirements for Conviction U nder A r

ticle 27, S ection 577, of the A nnotated Code

of Maryland (1957 E dition), W ere N ot Met

in T hat A ppellants’ A cts W ere N ot W anton,

A ppellants W ere N ot Given P roper N otice,

and A ppellants W ere A cting U nder A B ona

F ide Claim of R ight ................................................ 8

II. T h e A rrests and Convictions of A ppellants

Constitute an E xercise of S tate P ower T o

E nforce R acial S egregation in V iolation of

R ights P rotected B y th e F ourteenth A mend

ment to the U nited S tates Constitution and

B y 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982 ........................ 12

Conclusion ..................................................................... 19

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases :

Baltimore Transit Co. v. Faulkner, 179 Md. 598, 20

A.2d 485 (1941) ................................................. 8

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) ......... ...15,16

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60, (1917) ................ 9

City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F.2d 425 (4th

Cir. 1957) ............................................................ 13,14

City of Petersburg v. Alsup, 238 F.2d 830 (5th Cir.

1956), cert, denied 353 U.S. 922 ........................

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ......................

13

13

11 Index Continued

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ........................... 9

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220

F.2d 386 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d per curiam 350

U.S. 877 .................................................................. 13

Department of Conservation v. Tate, 231 F.2d 615

(4th Cir. 1956) cert, denied 352 U.S. 838 ........... 13

Dennis v. Baltimore Transit Co., 189 Md. 610, 57

A.2d 813 (1947) ................................................... 8

Drews v. Maryland, — Md. —, No. 113, September

Term, 1960 .......................................................... 14,18

Durkee v. Murphy, 181 Md. 259, 29 A.2d 253 (1942) .. 14

G-reenfeld v. Maryland Jockey Club of Baltimore, 190

Md. 96, 57 A.2d 335 (1948) ................................... 17

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 223 F.2d 93 (5th Cir.

1955), aff’d per curiam 350 U.S. 879 .................... 13

Interstate Amusement Co. v. Martin, 8 Ala. App. 481,

62 So. 404 (1913) ................................................. 12

Jones v. Marva Theatres, Inc., 180 F. Supp. 49 (D.

Md. 1960) ................................................................ 13

Kansas City, Mo. v. Williams, 205 F.2d 47 (8th Cir.

1953), cert denied 346 U.S. 826 ........................... 13

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946) ..................... 16

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U.S. 141 (1943) ..................... 16

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950) ..................................................................... 14

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n., 202 F.2d

275 (6th Cir. 1953), aff’d per curiam 347 U.S.

971 ........................................................................... 13

New Orleans City Park Improvement Ass’n. v. Detiege,

252 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1958), aff’d per curiam 358

U.S. 54 ................................................................... 13

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) .................. 14

Rice v. Arnold, 45 So. 2d 195 (Fla. 1950), vacated 340

U.S. 848 .................................................................. 13

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ......................15,16

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953) ......................... 15

Tonkins v. City of Greensboro, 276 F.2d 890 (4th Cir.

I960) ....................................................................... 13

Valle v. Stengel, 176 F.2d 697 (3rd Cir. 1960) ............. 17

Page

Index Continued iii

Constitution and S tatutes: Page

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment...................................7, 8,13,14,

15,16,18

United States Code:

Title 42, Section 1981 ............................................7,11,17

Title 42, Section 1982 ............................................7,11,17

Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 edition):

Article 27, Section 576 ............................................... 8

Article 27, Section 577 ...................................... 2, 3, 4, 5, 6,

7, 8, 9, 10

Article 27, Section 578 ............................................... 8

Article 27, Section 579 ............................................... 8

Article 27, Section 580 ............................................... 8

APPENDIX

Docket Entries and Judgment Appealed From

Warrants of Arrest (Griffin, et al.) ..................

Warrants of Arrest (Greene, et al.) ................

Proceedings (Griffin, et al.) ...............................

Testimony at Trial:

Francis J. Collins

Direct ..........................................................

Cross ............................................................

Abram Baker

Direct ..........................................................

C ross............................................................

Re-Redireet .................................................

Kay Freeman

Direct ..........................................................

Cross ................................

Page

E. 1

E. 11

E. 12

E. 13

E. 14

E. 18

E. 22

E. 24

E. 26

E. 30

E. 32

IV Index Continued

Opinion of Court (Griffin, et al.) ....................................E. 33

Proceedings (Greene, et al.) .......................................... E. 37

Testimony at Trial:

Francis J. Collins

Direct ......................................................................E. 37

C ross..........................................................................E. 39

Abram Baker

Direct ......................................................................E. 40

C ross....................................................................... E. 41

Redirect ..................................................................E. 44

Recross....................................................................E. 46

Re-Redireet ...................................................... E. 46

Lenord Woronoff

Direct ..................................................................... E. 46

C ross........................................................................E. 47

Ronyl J. Stewart

Direct ............................................... E. 48

Martin A. Schain

Direct ......................................................................E. 51

C ross................................................................. ,E. 51

Abram Baker (Recalled)

Direct ......................................................................E. 52

C ross.......................................................................... E. 53

William Brigfield

Direct ......................................................................E. 59

Opinion of Court (Greene, et al.) ..................................E. 60

State’s Exhibit No. 8 A .....................................................E. 66

State’s Exhibit No. 8 B .....................................................E. 75

Page

IN THE

C o u r t of Appea l s of M a r y l a n d

September Term, 1960

No. 248

W illiam L. Gr iffin , et al., Appellants,

vs.

S tate of Maryland, Appellee,

and

Cornelia Greene, et al., Appellants,

vs.

S tate of Maryland, Appellee.

Appeal From the Circuit Court for Montgomery County

(Jam es H. Pugh, Judge)

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

STATEM ENT OF THE CASE

Appellants William L. Griffin, Marvous Saunders, Michael

Proctor, Cecil T. Washington, Jr., and Gwendolyn Greene

(hereinafter referred to as Appellants Griffin et al.) were

arrested on June 30, 1960, and charged in warrants issued

by a Justice of the Peace of Montgomery County with

trespassing on June 30, 1960, on the property of Glen

Echo Amusement Park in violation of Article 27, Section

2

577, of the Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 edition).

All of the aforementioned Appellants are members of

the Negro race.

Appellants Cornelia A. Greene, Helene D. Wilson, Mar

tin A. Schain, Bonyl J. Stewart, and Janet A. Lewis

(hereinafter referred to as Appellants Greene et al.) were

arrested on July 2, 1960, and charged in warrants issued

by a Justice of the Peace of Montgomery County with

trespassing on July 2, 1960, on the property of Glen Echo

Amusement Park in violation of the same statute cited

above. Appellants Greene, Stewart, and Lewis are mem

bers of the Negro race and Appellants Wilson and Schain

are members of the Caucasian race.

Article 27, Section 577, of the Annotated Code of Mary

land (1957 edition), provides as follows:

§ 577. Wanton trespass upon private land.

Any person or persons who shall enter upon or cross

over the land, premises or private property of any

person or persons in this State after having been duly

notified by the owner or his agent not to do so shall

be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and on conviction

thereof before some justice of the peace in the county

or city where such trespass may have been committed

be fined by said justice of the peace not less than one,

nor more than one hundred dollars, and shall stand

committed to the jail of county or city until such fine

and costs are paid; provided, however, that the person

or persons so convicted shall have the right to appeal

from the judgment of said justice of the peace to the

circuit court for the county or Criminal Court of Balti

more where such trespass was committed, at any time

within ten days after such judgment was rendered;

and, provided, further, that nothing in this section

shall be construed to include within its provisions

the entry upon or crossing over any land when such

entry or crossing is done under a bona fide claim of

3

right or ownership of said land, it being the intention

of this section only to prohibit any wanton trespass

upon the private land of others.

Appellants were arraigned, pleaded not guilty, and waived

a jury trial. The cases of Appellants Griffin et al., were

consolidated for trial, by consent, and tried on September

11, 1960, in the Circuit Court for Montgomery County,

Maryland, before Judge James H. Pugh. The cases of

Appellants Greene et al., similarly were consolidated for

trial and tried on September 11, 1960, in the same Court

and before the same judge.* Each of the Appellants (de

fendants below) was found guilty as charged and fined.

QUESTIONS PRESEN TED

1. Are the following elements of Article 27, Section 577,

of the Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 edition), each of

which is necessary to support a conviction, established by

the record:

a. Were the actions of Appellants wanton within

the meaning of the statute!

b. Was the statutory requirement of due notice by

the owner or his agent not to enter upon or cross

over the land in question met!

c. Were Appellants, who were attempting to assert

constitutional, statutory, or common-law rights, acting

under a bona fide claim of right within the meaning of

the statute!

2. Did the arrest and conviction of Appellants violate

or interfere with the rights secured to them by the Due

Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States or the

provisions of 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1982!

* The records of the two consolidated cases were consolidated into one

record on appeal pursuant to a letter, dated November 16, 1960, from the

Chief Deputy Clerk of the Court of Appeals of Maryland to counsel for

the Appellants.

4

STATEM ENT OF FACTS

On June 30, 1960, Appellants Griffin et al. entered onto

the property of Glen Echo Amusement Park (E. 15, 16),

a park operated by Kebar, Inc., a Maryland corporation,

under a lease from Rekab, Inc., also a Maryland corpora

tion and the owner of the property (E. 22, 23). The officers,

stockholders, and directors of both corporations are the

same persons (E. 22, 26). The park is located in Mont

gomery County, Maryland (E. 15). The owners' and oper

ators of the park employ National Detective Agency, a

District of Columbia corporation, to provide a force of

guards at the park (E. 18, 24), and on June 30, 1960,

and at all times pertinent to this action, the aforementioned

guards were under the charge of Francis J. Collins (here

inafter referred to as “ Lt. Collins” ), an employee of Na

tional Detective Agency (E. 14, 18) who also holds a com

mission from the State of Maryland as a Special Deputy

Sheriff for Montgomery County, Maryland (E. 18).

When Appellants Griffin et al. entered the park, they

proceeded to the carrousel which is located within the park

and took seats thereon (E. 16). When an attendant ap

peared, Appellants Griffin et al. tendered valid tickets for

this ride which had been purchased and transferred to

them by others (E. 20, 31). The attendant refused to

accept the tickets and also refused to start the carrousel

(E. 32). After a short time Lt. Collins approached

Appellants Griffin et al. and advised them that the

park was segregated and that Negroes were not per

mitted therein; he further advised that Appellants Griffin

et al. should leave the park or he would cause their arrest

(E. 16, 17, 19). Appellants Griffin et al. refused to

leave, whereupon Lt. Collins arrested them, transported

them to an office located on the park property, and notified

the Montgomery County Police, who came and took Appel

lant to a police station located in Bethesda, Maryland (E.

17), where they were charged with violations of Article 27,

5

Section 577, of the Maryland Code Annotated (1957 edi

tion) (E. 11).

At all times pertinent hereto the conduct of Appellants

Griffin et al. was orderly and peaceable (E. 21, 22, 31);

the policy of the park was to refuse admission to Negroes

solely on account of their race (E. 19, 23, 24, 25); and it was

pursuant to this policy that Appellants Griffin et al. were

refused service and arrested (E. 19, 24). Admission to the

park is free and there is free and open access to the park

through unobstructed entry ways (E. 20); the tickets

which were in the possession of Appellants Griffin et al.

were valid, duly purchased, and without limitation on

transfer (E. 20, 31); said tickets could be purchased

at a number of booths located within the park (E. 20); and

no refund or offer to make good the tickets in any way was

made by the operators of the park to Appellants Griffin

et al. (E. 20).

Glen Echo Amusement Park advertises through various

media, such as press, radio, and television, as to the avail

ability of its facilities to the public and invites the public

generally, without mention of its policies of racial dis

crimination, to come to the park and use the facilities

there provided (E. 25, 31). In addition to the car

rousel the park offers various other facilities (E. 32).

Appellants Greene et al. were arrested on July 2, 1960,

within the confines of a restaurant located in Glen Echo

Amusement Park (E. 38), under circumstances sub

stantially similar to those surrounding the arrest of Ap

pellants Griffin et al. This restaurant was operated by

B & B Catering Co., Inc., under an agreement with Kebar,

Inc. (E. 40, 41).

In order to establish the relationship between these cor

porations, two documents were admitted into evidence (E.

53). The first, dated August 29, 1958, covered the “ 1959

and 1960 Seasons” (E. 75). The second, undated and

consisting of six pages, covered the period commencing on

6

or about April 1, 1957, and ending on or about Labor Day,

September, 1958 (E. 66). Officers of Kebar, Inc., and

B & B Catering Co., Inc., testified that the two documents

constituted the entire agreement between the parties in

effect on the day Appellants Greene et al. were arrested

(E. 53, 59). Appellants objected to the introduction of

the second document (E. 53).

When Appellants Greene et al. entered the restaurant,

the attendants refused to serve them (E. 49, 51) and

closed the counter (E. 51, 52). Shortly thereafter, Lt.

Collins appeared and advised Appellants Greene et al. that

they were undesirable and that if they did not leave, they

would be arrested for trespassing (E. 38, 39, 49).

Appellants Greene et al. refused to leave, whereupon Lt.

Collins arrested them, transported them to an office located

on the park property, and notified the Montgomery County

Police, who took them to a police station located in Bethes-

da, Maryland (E. 39), where Appellants Greene et al. were

charged with violations of Article 27, Section 577, of the

Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 edition) (E. 12). The

arrests were made to implement the policy of the operators

of the park to maintain racial segregation (E. 44, 47).

Appellants’ conduct was peaceful and orderly at all times

pertinent hereto (E. 39, 50). The facts' concerning

ownership and operation of Glen Echo Amusement Park

(E. 40) and its policies of racial exclusion (E. 44, 47),

Francis J. Collins, and the National Detective Agency

guards (E. 37, 38, 39), set forth above, apply equally to

Appellants Greene et al. as they do to Appellants Griffin

et al.

At the trials held on September 11 and 12, 1960, re

spectively, all of the Appellants were found guilty as

charged and fined (E. 36, 65). It is from these convictions

that this appeal is taken.

7

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENTS

The record does not support the convictions of Appel

lants because of failure to meet the requirements of Ar

ticle 27, Section 577, of the Annotated Code of Maryland

(1957 edition), under which they were convicted. First,

the acts of Appellants were not wanton but were at all

times peaceable and orderly and cannot be characterized

as reckless or malicious. Second, Appellants were not

given the statutory notice required, since no notice was

given to them at or prior to the time of entry into the place

of public accommodation involved. Furthermore, Appel

lants Greene et al. were given no notice whatever by duly

authorized agents of the restaurant in which they were

arrested. Third, Appellants entered and remained on the

property in question under a bona fide claim of right and

were acting under that claim when they were arrested.

The arrests and convictions of Appellants constituted

an unlawful interference with the constitutionally pro

tected rights of Appellants under the Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. Appellants are

protected by the Constitution against the use of state

authority to enforce the private racially discriminatory

policies of a person whose property is open to use by the

public as a place of public service and accommodation.

Further, appellants are entitled under the Constitution

and as specified in 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982 to be

free from interference under color of state law with the

making and enforcing of contracts or the purchasing of

personal property on account of race or color. Moreover,

the arrests and convictions of Appellants were not a rea

sonable exercise of the police power of the state necessary

to maintain law and order.

8

I

ARGUM ENT

The R equirem ents for Conviction U nder A rticle 27, Section

577, of the A nnotated Code of M aryland (1957 Edition),

W ere Not M et In T hat A ppellan ts ' Acts W ere Not W anton,

A ppellants W ere Not G iven P roper Notice, and A ppellants

W ere A cting U nder a Bona Fide C laim of R ight.

A prerequisite to violation of Article 27, Section 577, of

the Annotated Code of Maryland (1957 edition), is wanton

ness. The statute is clear on its face in this regard, since

it is entitled “Wanton trespass upon private land.” In

addition, the statute concludes with the statement that it is

“ the intention of this section only to prohibit any wanton

trespass upon the private land of others” (emphasis sup

plied). Moreover, the use of “wanton” in this section is

in contradistinction to other criminal provisions of the

Annotated Code of Maryland relating to criminal trespass

which do not contain this requirement. Article 27, Sections

576, 578, 579, and 580, Annotated Code of Maryland (1957

edition).

“ Wanton” normally means a malicious or destructive

act. While this Court has not construed “ wanton” as used

in Article 27, Section 577, it has construed “wanton” in

other contexts. In Dennis v. Baltimore Transit Co., 189

Md. 610, 617, 56 A.2d 813 (1947), this Court stated. “ [t]he

word wanton means characterized by extreme recklessness

and utter disregard for the rights of others” , citing Balti

more Transit Co. v. Faulkner, 179 Md. 598, 602, 20 A.2d 485

(1941). In recognizing the need for a finding that Appel

lants’ conduct was wanton, the Trial Judge, in his opinion

in one of these cases in the lower court stated that

“ wanton” means “ . . . reckless, heedless, malicious,

characterized by extreme recklessness, foolhardiness and

reckless disregard for the rights or safety of others, or

of other consequences” (E. 33).

9

It is difficult to comprehend the manner in which Appel

lants’ conduct could be deemed wanton for purposes of

conviction under the criminal statute here involved. The

record is clear that the Appellants at all times conducted

themselves in a peaceable and orderly manner. They en

tered a place of public accommodation to which they, as

members of the general public, had been invited through

advertisement; they entered the usual and unobstructed

route of ingress and egress ; and they were attempting to

do no more than make use of the services offered at the

time of their arrest. The act for which they were arrested

was their refusal to leave under the belief that they were

entitled to enjoy these servics free from interference by

the state on account of race or color.

Moreover, they peacefully submitted to arrest. The

Trial Judge, in part, seemed to base the finding of wanton

ness on the possibility that the presence of a Negro in a

place of public accommodation, the proprietors of which

maintain a policy of racial discrimination, might produce

a riot. Not only is this the result of archaic thinking; it

also is contrary to the proposition frequently enunciated by

the Supreme Court of the United States that the rights of

private individuals are not to be sacrificed or yielded to

potential violence and disorder brought about by others.

See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 16 (1958); Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U.S. 60, 81 (1917).

The other basis for this finding of wantonness is the

refusal of Appellants, because of their belief in their right

to enjoy the services offered, to leave the premises upon

being requested to do so. This, in and of itslf, is not a

proper basis for a finding of wantonness, since the activity

of Appellants was not characterized by that extreme reck

lessness or foolhardiness which is required in order to

arrive at a determination of the type of conduct punishable

under the statute.

A second prerequisite to a valid conviction under Article

27, Section 577, of the Annotated Code of Maryland, is due

10

notice by the owner or his agent not to enter upon or cross

over his land, premises, or property. The language of the

statute requires prior notice as a condition of conviction.

It only applies to an entry or crossing “ after having been

duly notified by the owner or his agent not to do so. ’ ’ In the

instant cases, no notice was posted nor was any notice

orally communicated to Appellants prior to their entry

onto the land. Appellants had entered through an unre

stricted means of ingress, open to the public, who were

permitted and, in fact, invited to enter and use the facili

ties of the park. Appellants Griffin et al. received no

communication from anyone connected with the park until

they were on the carrousel, and Appellants Greene et al.

received no communication whatever until they were inside

the restaurant, both of which were well within the bound

aries of the property on which they allegedly trespassed.

This Court is under the normal constraint to construe the

statute narrowly, particularly since it is in derogation of

the common law.

Even if the Court were to construe the statute broadly in

the sense of meaning notice subsequent to entry, as to

Appellants Greene et al., the record does not show that Lt.

Collins was within the category of persons who are author

ized to give notice under the statute, and therefore the pur

ported notice was invalid. These Appellants were in a

restaurant which was leased by Glen Echo Amusement

Park (Kebar, Inc.) to B & B Catering Co., Inc. Appellants

contend that, as a matter of law, the agreement between

Kebar and B & B was contined in its entirety in the docu

ment dated August 29, 1958 (E. 75). It did not purport to

incorporate by reference or otherwise refer to any prior

agreement. It was complete on its face and set forth the

fact that it was “ the agreement” between the parties con

taining the “ terms” thereof. The prior lease (E. 66), by

its terms, expired in September, 1958, and, as a matter of

law, was not and could not have been extended by the agree

ment dated August 29, 1958. The testimony of the corpo

11

rate officers to the contrary (E. 55, 56, 57, 59) is insufficient,

appellants contend, to alter this conclusion. Further, the

fact that the two agreements have overlapping and in some

cases contradictory provisions demonstrates that the agree

ment of August 29, 1958, was not intended as an extension

of or supplement to the prior agreement. Unlike the prior

agreement, the agreement of August 29, 1958, created a

lease rather than a license, and contained no reservation

of control over the operation and conduct of the lessee’s

business beyond a restriction on employment of persons

under eighteen years of age. It follows, if B & B was a

lessee of the restaurant in which the arrests occurred, as

distinguished from a licensee, that the evidence is wholly

insufficient to support the contention that Lt. Collins was

acting as the agent of the lessee when Appellants Greene

et al. were “ notified” and subsequently arrested.

The third basis for setting aside Appellants conviction is

the proviso that the statute does not apply to persons who

are acting under a bona fide claim of right to be upon the

property of another.

All of Appellants were members of the general public,

invited to the park by the operators thereof. This invita

tion was extended to the public, without qualification as

to race or color, particularly to persons residing in the

Washington metropolitan area, by way of advertisements

in newspapers, signs on buses, and by radio and television.

Entry to the park was free and unobstructed and open to

all responding to such invitations. In view of these facts,

Appellants’ bona fide claim of right to enter and cross

over the property seems incontrovertible.

This claim of right is reinforced by the fact that all of

the Appellants were trying to make or to enforce con

tracts, or to purchase personal property, and thus their

activity is given the express sanction of law, 42 TT.S.C.A.

§4 1981, 1982, which give all persons, including Negroes,

12

the same right “ in every State and Territory to make and

enforce contracts . . . as is enjoyed by white citizens, . .

and an equivalent right to purchase personal property. A

peaceable entry into a place of public business in order to

purchase food, tickets, or other items on sale, or to make use

of tickets duly purchased from the proprietor is certainly

a proper exercise of these federally protected rights and,

Appellants submit, gives rise to a bona fide claim of right,

within the meaning of the statute involved.

In addition, in the case of Appellants Griffin et al., each

of them had valid and duly purchased tickets for admit

tance to the rides in the park. These Appellants, at the

time of their arrest, were on one such ride and had ten

dered the necessary tickets. Therefore, they were acting

under a bona fide claim of right and were thereby excluded

from operation of the statute since a ticket to a place of

public amusement constitutes a contract between the pro

prietor and the holder. Interstate Amusement Co. v. Mar

tin, 8 Ala. App. 481, 62 So. 404 (1913).

II.

The A rrests and Convictions of A ppellan ts C o n stitu te An

E xercise of S ta te Pow er to Enforce R acial Segregation in

V iolation of R ights P ro tected by th e F o u rteen th A m end

m ent to the U nited S ta tes C onstitu tion and B y 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981 and 1S82.

The arrests and convictions of Appellants implemented

the racially discriminatory policies of Glen Echo Amuse

ment Park, a place of public accommodation. Such arrests

and convictions constituted the use of the state police power

to enforce those policies. Appellants contend that their

federal rights thereby were violated. Although the federal

questions presented here have not been squarely decided

by the Supreme Court of the United States, the principles

on which they rely have been clearly enunciated.

13

These basic principles were first expressed in the Civil

Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883), in which the Supreme

Court declared that the Fourteenth Amendment and the

rights and privileges secured thereby “nullifies and makes

void . . . State action of every kind which impairs the priv

ileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, or

which injures them in life, liberty or property without

due process of law, or which denies to any of them the

equal protection of the laws.” Supra at 11. Moreover,

the Court stated that racially discriminatory policies of

individuals are insulated from the proscription of the

Fourteenth Amendment only in so far as they are “ un

supported by State authority in the shape of laws, customs

or judicial or executive proceedings,” or are “ not sanc

tioned in some way by the State.” Supra at 17.

Consistent with these expressions, the doctrine has been

clearly established that state power cannot be used affirma

tively to deny access to or limit use of public recreational

facilities because of race. This doctrine has been applied

to such recreational facilities as swimming pools, Kansas

City, Mo. v. Williams, 205 F.2d 47 (8th Cir. 1953), cert,

denied 346 U.S. 826; Tonkins v. City of Greensboro, 276

F.2d 890 (4th Cir. I960); public beaches and bathhouses,

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220 F.2d

386 (4th Cir. 1955), aff’d per curiam 350 U.S. 877; Depart

ment of Conservation v. Tate, 231 F.2d 615 (4th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied 3o2 U.S. 838; City of St. Petersburg v. Alsup,

238 F.2d 830 (5th Cir. 1956), cert, denied 352 U.S. 922; golf

courses, Rice v. Arnold, 45 So.2d 195, (Fla. 1950), vacated

340 U.S. 848; Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 223 F.2d 93 (5th

Cir. 1955) aff’d per curiam 350 U.S. 879; City of Greens

boro v. Simkins, 246 F.2d 425 (4th Cir. 1957); parks and

recreational facilities, New Orleans City Park Improve

ment Association v. Detiege, 252 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1958),

aff’d per curiam 358 U.S. 54; and theatres, Muir v.

Louisville Park Theatrical A ss’n., 202 F.2d 275 (6th Cir.

1953), off d per curiam, 347 U.S. 971; Jones v. Marva

Theatres, Inc., 180 F.Supp. 49 (D. Md. 1960).

14

Particularly pertinent to the instant case is the state

ment contained in the decision of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in the Dawson case,

supra at 387:

. . it is obvious that racial segregation in recrea

tional activities can no longer be sustained as a proper

exercise of the police power of the state . . . ”

The Court of Appeals in that case specifically overruled

Durkee v. Murphy, 181 Md. 259, 29 A.2d 253 (1942), which

had espoused the doctrine of separate-but-equal in public

recreational facilities. The Court, of course, based its

view on the fact that Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537

(1896), had in effect been overruled by the Supreme Court

in a series of cases beginning with McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950), as applied to educa

tional facilities, and the Court stated that it was equally

inapplicable to any other public facility.

This rule has been followed without distinction between

recreational facilities which are operated by state authori

ties in a “governmental” or “ proprietary” capacity, City

of St. Petersburg v. Alsup, supra, and facilities which

have been leased by state authorities to private operators,

City of Greensboro v. Simkins, supra. The rule therefore

has been applied in an all-inclusive manner.

The distinction between the cases cited above and the

instant case is the fact that the facility here involved is

not operated by or leased from the state, and therefore the

owners or operators of the park are not themselves af

fected by the limitations of the Fourteenth Amendment.

It follows, as has been held by this Court in Drews v.

Maryland, — Md. — (1961), No. 113, September Term,

1960, that a private owner or operator of a place of

public amusement is free to choose his customers on such

bases as he sees fit, including race or color. It is equally

clear, however, that the state can no more lend its legisla

15

tive, executive or judicial power to enforce private policies

of racial discrimination in a place of public accommodation

than it can adopt or enforce such policies in a facility

operated by it directly. If one is an infringement of

Fourteenth Amendment rights and an improper exercise

of the state’s police power, so is the other. Cf. Terry v.

Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953).

The Supreme Court also has enunciated the principle

that the powers of the state, whether legislative, judicial,

or executive, cannot he used to enforce racially discrimina

tory policies of private persons relating to the purchase

and sale of real property. In Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S.

1 (1948), the Court held that state courts could not carry

out the racially discriminatory policies of private land

owners through judicial enforcement of racial restrictive

covenants. Moreover, the Court was unwilling to permit

state courts to grant damages against private landowners

for breach of such covenants. Barrows v. Jackson, 346

U.S. 249 (1953). The Court, in holding that judicial en

forcement of racial discrimination violates the Fourteenth

Amendment, made it clear “ that the action of the States

to which the Amendment has reference, includes action of

state courts and state judicial officers.” Shelley v.

Kraemer, supra at 18. The assertion that property rights

of private individuals were paramount was met by the

Court in stating that:

The Constitution confers upon no individual the

right to demand action by the State which results in

the denial of equal protection of the laws to other

individuals. Supra at 22.

We are not here concerned, nor was the Court in Shelley

and Barrows, concerned with the questions whether or not

private citizens are required to sell to Negroes or of the

power of the state to force them so to sell. The question,

here, as in Shelly and Barrows, is whether or not the state,

consistent with the Constitution, can permit the full panoply

of its power to be used to aid, abet, implement, and effec

16

tuate discrimination by private entrepreneurs on account

of race or color. And, in the instant case, the use of state

power is more odious than in Shelly and Barrows because

criminal, rather than civil, sanctions have been imposed.

Furthermore, if individuals are attempting to exercise

federally protected rights, the fact that they are physically

present on private property which has been opened up to

the public is of no consequence and does not justify the

imposition by the state of criminal trespass sanctions.

In Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946), privately

owned land was being used as a “ company town.” The

landowner caused the arrest (by a company employee who

was also a county deputy sheriff) for trespass of a member

of a religious sect who was distributing literature contrary

to the wishes of the owner. It was argued in support of

the arrest that the landowner’s right of control is coexten

sive with the right of the homeowner to regulate the con

duct of his guests. The Court stated:

“We cannot accept that contention. Ownership does

not always mean absolute dominion. The more an

owner, for his advantage, opens up his property for

use by the public in general, the more do his rights be

come circumscribed by the statutory and constitutional

rights of those who use it,” Supra at 505-6.

Obviously, the respective rights of the parties must be

recognized and balanced. It should be noted, however, that

even the homeowner does not have absolute and inviolable

rights, as pointed out by the Court in Martin v. Struthers,

319 U.S. 141 (1943) (ordinance prohibiting door-to-door

distribution of handbills held invalid as applied to ad

vertisement of religious meeting).

Glen Echo Amusement Park has been opened by the

owner as a place of public accommodation, for his finan

cial advantage, and, following Marsh, he has thereby sub

ordinated his rights as a private property owner to the con

stitutional rights of the public who use it.

17

Appellants also rely on 42 U.S.C. §1981, which pro

vides that “ all persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States shall have the same right in every State

and Territory to make and enforce contracts . . . as is en

joyed by white citizens, . . .” , and on 42 U.S.C. § 1982,

which provides that “all citizens . . . shall have the same

right . . . as is enjoyed by white citizens to . . . purchase

. . . personal property.” Appellants entered Glen Echo

Amusement Park for the purpose of making contracts

with the operators of the park to use the facilities located

there and to purchase food, tickets, and other articles of

personal property which were on sale to the public. Ap

pellants Griffin et al, being in lawful possession of valid

tickets, in fact had entered into contractual relations with

the operators of the park (see Greenfeld v. Maryland

Jockey Club of Baltimore, 190 Md. 96, 57 A.2d 335 (1948)),

and were, at the time of their arrest, seeking to enforce

those contracts. Without question, Appellants arrests con

stituted unlawful interference with the exercise of their

statutory rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution.

The arguments advanced hereinabove by Appellants were

urged on the court in Valle v. Stengel, 176 F.2d 697 (3rd

Cir. 1949), involving facts substantially similar to those in

the instant case. In Valle, the court held that the convic

tions of the defendants under the New Jersey trespass

statute were void on the grounds that they constituted state

enforcement of privately imposed racial discrimination in

a place of public amusement in violation of defendants’

rights under the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment, and that they constituted

an unconstitutional interference with defendants’ equal

rights to make and enforce contracts and to purchase per

sonal property as set forth in 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982.

Appellants rely on that case.

The Court might well inquire as to the means available

to the owner of a place of public accommodation to enforce

18

his right to pick and choose his customers and to remove

unwanted persons from his property. Appellants submit

that the owner may resort to his common-law right of

reasonable self-help to remove such persons. If the person

resists to the point of disorderly conduct, or if a breach

of the peace is imminent or ensues, then resort may be

had to state authority to redress or prevent such independ

ent violations of the law. To permit state authorities to

lend their aid by arresting unwanted persons solely on ac

count of race or color in a place of public accommodation,

and to enforce judicially such racially discriminatory poli

cies through criminal prosecution and conviction goes too

far.

Appellants are aware of the holding of this Court in

Drews v. State of Maryland, — Md. — (1961), No. 113,

September Term, 1960. That case is factually distinguish

able on at least two grounds. In the Drews case, which

involved convictions for disorderly conduct, this Court

relied heavily upon the fact as established by the record

that the crowd which gathered around the defendants at

the time of their arrest was angry and on the verge of

getting out of control, which led this Court to conclude

that defendants were “inciting” the crowd by refusing

to obey valid commands of police officers. In addition, it

was found by the trial court that the Drews defendants in

fact acted in a disorderly manner. In the instant case, the

record is entirely barren of evidence that any element of

incitement was present. Further, the record repeatedly

shows that Appellants at all times conducted themselves in

a peaceful and orderly manner. In this case, therefore,

disorder and imminent violence were not present, and it

cannot be said here, as it was said in Drews, that the ar

rests were made to prevent violence or the further com

mission of disorderly acts. Appellants submit that this

case cannot be decided simply by following Drews v. Mary

land, supra.

This Court is called upon to balance conflicting interests.

On the one hand, the private businessman, having invited

19

the general public to come upon his land, nevertheless

seeks to exclude particular members of that public on ac

count of race and color and asks the state to assist him in

so doing. On the other hand, members of the public, hav

ing been invited to use the services offered by the private

businessman, ask only that the state refrain from assist

ing him in effectuating his dicriminatory policies.

In striking this balance, Appellants urge this Court to

take judicial notice of the changes which have occurred in

the State of Maryland in recent years. Discrimination on

account of race is now contrary to the public policy of the

State in all areas of public activity. Bills have been intro

duced in the legislature to outlaw racial discrimination in

privately owned places of public accommodation. At least

one county has established a Human Relations Council to

deal with residual areas of racial friction. In Baltimore,

parts of Montgomery County, and elsewhere in the state,

privately owned hotels, restaurants, bowling alleys and

other places of public accommodation have been desegre

gated by the voluntary action of their owners.

All of these developments stem from the recognition that

racial discrimination is morally wrong, economically un

sound, inconvenient in practice and unnecessary in fact.

In deciding these cases justice can permit but one result.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the judgments below

should be reversed with directions to vacate the convic

tions and to dismiss the proceedings against Appellants.

Charles T. D uncan

J oseph H . S harlitt

Claude B. K ahn

Attorneys for Appellants

L ee M. H ydeman

Of Counsel

RECORD EXTRACT

E l

No. 3881 Criminal

S tate oe Maryland

Docket Entries

vs.

W illiam L. Gr iffin

TRESPASSING

Aug. 4, 1960—Warrant, Recognizance, Demand for Jury

Trial &c filed, Page No. 1.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed, Page No. 5.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to consolidate this case

with Numbers 3882, 3883, 3889 and 3892 Criminal.

Sep. 12,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 12, 1960—The Court finds defendant guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Defendant was asked if he had anything to

say before sentence.

Sep. 12, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, William L.

Griffin, pay a fine of Fifty and no/100 dollars ($50.00)

current money and costs, and in default in the payment

of said fine and costs, that the Traverser, William L.

Griffin be confined in the Montgomery County Jail until

the fine and costs have been paid or until released by due

process of law.

Sep. 12,1960—Appeal filed, Page No. 6.

Oct. 13, 1960—Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to Court of Appeals to and

including November 15, 1960 filed, Page No. 7.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J . H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E2

No. 3882 Criminal

S tate of M aryland

Docket Entries

vs.

Michael A. P roctor

TRESPASSING

Ang. 4, 1960—Warrant, Recognizance, Demand for Jury

Trial &e. filed, Page No. 1.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed, Page No. 5.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to consolidate this case

with Numbers 3881, 3883, 3889 and 3892 Criminals.

Sep. 12,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 12,1960—The Court finds defendant guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Defendant was asked if he had anything

to say before sentence.

Sep. 12, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, Michael A.

Proctor, pay a fine of Fifty and no/100 Dollars ($50.00)

and costs, and in default in the payment of said fine and

costs, that the Traverser, Michael A. Proctor, be con

fined in the Montgomery County Jail until the fine and

costs have been paid or until released by due process of

law.

Sep. 12,1960—Appeal filed in No. 3881 Criminal.

Oct. 13, 1960—'Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to Court of Appeals to and

including November 15, 1960 filed in No. 3881 Criminal.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J . H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E3

No. 3883 Criminal

S tate of Maryland

Docket Entries

vs.

Cecil T. W ashington, J r.

TRESPASSING

Aug. 4, 1960—Warrant, Recognizance, Demand for Jury

Trial &c. filed, Page No. 1.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed, Page No. 6.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to consolidate this case

with Numbers 3881, 3882, 3889 and 3892 Criminals.

Sep. 12,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 12, 1960—The Court finds defendant guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Defendant was asked if he had anything to

say before sentence.

Sep. 12, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, Cecil T.

Washington, Jr., pay a fine of Fifty and no/100 Dollars

($50.00) current money and costs and in default in the

payment of said fine and costs, that the Traverser Cecil

T. Washington, Jr., be confined in the Montgomery

County Jail until the fine and costs have been paid or

until released by due process of law.

Sep. 12,1960—Appeal filed in No. 3881 Criminal.

Oct. 13, 1960—Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to Court of Appeals to and

including November 15, 1960 filed in No. 3881 Criminal.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J . H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E4

No. 3889 Criminal

S tate op Maryland

Docket Entries

vs.

Marvous S aunders

TRESPASSING

Aug. 4, 1960—Warrant, Demand for Jury Trial &c. filed,

Page No. 1.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed, Page No. 6.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to consolidate this case

with Numbers 3881, 3882, 3883 and 3892 Criminal.

Sep. 12,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 12, 1960—The Court finds the defendant guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Defendant was asked if he had anything

to say before sentence.

Sep. 12, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, Marvous

Saunders, pay a fine of Fifty and no/100 Dollars ($50.00)

current money and costs, and in default in the payment of

said fine and costs that the Traverser, Marvous Saunders,

be confined in the Montgomery County Jail until the fine

and costs have been paid or until released by due process

of law.

Sep. 12,1960—Appeal filed in No. 3881 Criminal.

Oct. 13, 1960—Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to Court of Appeals to and

including November 15, 1960 filed in No. 3881 Criminal.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J. H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E5

No. 3892 Criminal

S tate oe Maryland

Docket Entries

vs.

Gwendolyn T. Greene

TRESPASSING

Aug. 4, 1960—Warrant, Demand for Jury Trial &c. filed,

Page No. 1.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed, Page No. 6.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to consolidate this case

with Numbers 3881, 3882, 3883 and 3889 and 3892 Crim

inals.

Sep. 12,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 12, 1960—The Court finds defendant guilty.

Sep. 12, 1960—Defendant was asked if she had anything

to say before sentence.

Sep. 12, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, Gwendolyn

T. Greene, pay a fine of Fifty and no/100 dollars ($50.00)

current money and costs, and in default in the payment

of said fine and costs, that the Traverser, Gwendolyn T.

Greene, be confined in the Montgomery County Jail until

the fine and costs have been paid or until released by

due process of law.

Sep. 12,1960—Appeal filed in No. 3881 Criminal.

Oct. 13, 1960—Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to Court of Appeals to and

including November 15, 1960 filed in No. 3881 Criminal.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J. H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E6

No. 3878 Criminal

S tate oe Maryland

Docket Entries

vs.

Cornelia A. Greene

TRESPASSING

Aug. 4, 1960—Warrant, Recognizance, Demand for Jury

Trial &c. filed, Page No. 1.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to consolidate this case

with numbers 3879, 3890, 3891 and 3893 Criminals.

Sep. 13, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed, Page No. 6.

Sep. 13,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 13, 1960—The Court finds defendant guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Defendant was asked if she had anything

to say before sentence.

Sep. 13, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, Cornelia A.

Greene, pay a fine of One hundred and no/100 dollars

($100.00) current money and costs, and in default in the

payment of said fine and costs that the Traverser, Cor

nelia A. Greene, be confined in the Montgomery County

Jail until the fine and costs have been paid or until

released by due process of law.

Sep. 13,1960—Appeal filed, Page No. 7.

Oct. 13, 1960—Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to Court of Appeals to and

including the 15th day of November, 1960, Page No. 8.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J. H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E7

No. 3879 Criminal

S tate of M aryland

Docket Entries

vs.

H elene D. W ilson

TRESPASSING

Aug. 4, 1960—Warrant, Recognizance, Demand for Jury

Trial &c. filed.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to consolidate this case

with Numbers 3878, 3890, 3891 and 3893 Criminals.

Sep. 13, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed.

Sep. 13,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 13, 1960—The Court finds defendant guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Defendant was asked if she had anything

to say before sentence.

Sep. 13, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, Helene D.

Wilson, pay a fine of One Hundred and no/100 dollars

($100.00) current money, and costs, and in default in the

payment of said fine and costs that the Traverser, Helene

D. Wilson, be confined in the Montgomery County Jail

until the fine and costs have been paid or until released

by due process of law.

Sep. 13,1960—Appeal filed in No. 3878 Criminal.

Oct. 13, 1960—Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to Court of Appeals to and

including November 15, 1960 filed in No. 3878 Criminal.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J . H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E8

No. 3890 Criminal

S tate of Maryland

Docket Entries

vs.

M artin A. S chain

TRESPASSING

Aug. 4, 1960—Warrant, Demand for Jury Trial &c. filed.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to consolidate this case

with Numbers 3878, 3879, 3891 and 3893 Criminal.

Sep. 13, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed.

Sep. 13,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 13, 1960—The Court finds defendant guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Defendant was asked if he had anything

to say before sentence.

Sep. 13, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, Martin A.

Schain, pay a fine of One hundred and no/100 dollars

($100.00) current money, and costs, and in default in the

payment of said fine and costs, that the Traverser, Mar

tin A. Schain, be confined in the Montgomery County

Jail until the fine and costs have been paid or until

released by due process of law.

Sep. 13,1960—Appeal filed in No. 3878 Criminal.

Oct. 13, 1960—Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to and including November 15,

1960 filed in No. 3878 Criminal.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J. H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E9

No. 3891 Criminal

S tate of Maryland

Docket Entries

vs.

R onyl J . S tewart

TRESPASSING

Aug. 4, 1960—Warrant, Demand for Jury Trial &c. filed.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and Leave to consolidate this case

with Numbers 3878, 3879, 3890 and 3893 Criminal.

Sep. 13, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed.

Sep. 13,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 13, 1960—The Court finds defendant guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Defendant was asked if he had anything to

say before sentence.

Sep. 13, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, Ronyl J.

Stewart, pay a fine of Fifty and no/100 dollars ($50.00)

current money, and costs, and in default in the payment

of said fine and costs, that the Traverser Ronyl J.

Stewart, be confined in the Montgomery County Jail,

until the fine and costs have been paid or until released

by due process of law.

Sep. 13,1960—Appeal filed in No. 3878 Criminal.

Oct. 13, 1960—Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to Court of Appeals to and

including November 15, 1960 filed in No. 3878 Criminal.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J. H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E10

No. 3893 Criminal

S tate of Maryland

Docket Entries

vs.

J anet A. L ewis

TRESPASSING

Aug. 4, 1960—Warrant, Demand for Jury Trial &c. filed.

Sep. 12, 1960—Motion and leave to consolidate this case

with Numbers 3878, 3879, 3890 and 3891 Criminal.

Sep. 13, 1960—Motion and leave to amend warrant and

amendment filed.

Sep. 13,1960—Plea not guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Submitted to the Court and trial before

Judge Pugh, Mrs. Slack reporting.

Sep. 13, 1960—The Court finds the defendant guilty.

Sep. 13, 1960—Defendant was asked if she had anything

to say before sentence.

Sep. 13, 1960—Judgment that the Traverser, Janet A.

Lewis, pay a fine of Fifty and no/100 dollars ($50.00)

current money, and costs, and in default in the payment

of said fine and costs, that the Traverser Janet A. Lewis,-

be confined in the Montgomery County Jail until the

fine and costs have been paid or until released by due

process of law.

Sep. 13,1960—Appeal filed in No. 3878 Criminal.

Oct. 13, 1960—Petition and Order of Court extending time

for transmittal of record to Court of Appeals to and

including November 15, 1960 filed in No. 3878 Criminal.

L. T. Kardy—State’s Attorney

J. H. Sharlitt & C. T. Duncan—Attorneys for Defendant

E ll

State Warrant

S tate of Maryland, M ontgomery County, to w it:

To James S. McAuliffe, Superintendent of Police of said

County, Greeting:

W hereas, Complaint hath been made upon the informa

tion and oath of Lt. Francis Collins, Deputy Sheriff in and

for the Glen Echo Park, who charges that William L.

Griffin, late of the said County and State, on the 30th day

of June, 1960, at the County and State aforesaid, did un

lawfully and wantonly enter upon and cross over the land

of Rekab, Inc., a Maryland corporation, in Montgomery

County, Mryland, such land at that time having been leased

to Kebar, Inc. a Maryland corporation, and operated as the

Glen Echo Amusement Park, after having been duly noti

fied by an Agent of Kebar, Inc., not to do so in violation of

Article 27, Section 577 of the Annotated Code of Maryland,

1957 Edition as amended, contrary to the form of the Act

of the General Assembly of Maryland, in such case made

and provided, and against the peace, government and dig

nity of the State.

You are hereby commanded immediately to apprehend

the said .............................—................ and bring ....h._.....

before ... ..... ........................................... ... Judge at _____

............. - ............ — Montgomery County, to be dealt with

according to law. Hereof fail not, and have you there

this Warrant.

Justice of the Peace for Montgomery

County, Maryland

Issued ...............................................19...... .

[Identical warrants were issued against Appellants

Michael A. Proctor, No. 3882 Criminals, Cecil T. Wash

ington, Jr., No. 3883 Criminals, Marvous Saunders, No.

3889 Criminals, and Gwendolyn T. Greene, No. 3892, Crim

inals.]

E12

State Warrant

S tate of Maryland, M ontgomery County, to w it:

To James S. McAuliffe, Superintendent of Police of said

County, Greeting:

W hereas, Complaint hath been made upon the informa

tion and oath of Lt. Francis Collins, Deputy Sheriff in and

for the Glen Echo Park, who charges that Cornelia A.

Greene, late of the said County and State, on the 2nd day

of July, 1960, at the County and State aforesaid, did un

lawfully and wantonly enter upon and cross over the land

of Eekab, Inc., a Maryland corporation, in Montgomery

County, Mryland, such land at that time having been leased

to Kebar, Inc. a Maryland corporation, and operated as the

Glen Echo Amusement Park, after having been duly noti

fied by an Agent of Kebar, Inc., not to do so in violation of

Article 27, Section 577 of the Annotated Code of Maryland,

1957 Edition as amended, contrary to the form of the Act

of the General Assembly of Maryland, in such case made

and provided, and against the peace, government and dig

nity of the State.

You are hereb)7- commanded immediately to apprehend

the said ...... ..................... —.............. . and bring ....h.......

before .............. .... ........................ ....... . Judge at _____

................... ..... ..... Montgomery County, to be dealt with

according to law. Hereof fail not, and have you there

this Warrant.

Justice of the Peace for Montgomery

County, Maryland

Issued .............................. - .......- .....19-----

[Identical warrants were issued against Appellants

Helene D. Wilson, No. 3879 Criminals, Martin A. Sehain,

No. 3890 Criminals, Ronyl J. Stewart, No. 3891 Criminals,

and Janet A. Lewis, No. 3893 Criminals.]

E13

2 Excerpts from Transcript of Proceedings (Griffin, et al.)

The above-entitled cause came on regularly for hearing,

pursuant to notice, on September 12, 1960, at 10:00 o’clock

a.m. before The Honorable James H. Pugh, Judge of said

Court, when and where the following counsel were present

on behalf of the respective parties, and the following pro

ceedings were had and the f ollowing testimony was adduced.

By Mr. McAuliffe: Your Honor, the State will move to

amend the warrants in all five oases, and I have prepared

copies of the amendment that we would ask that the Court

make to these warrants, and I would ask that in each case

the copy which I have prepared be attached to the original

warrant, as an amendment to it, and the amendment we

desire to make is the same amendment in each ease and

would read as follows:

By Judge Pugh: Have the defense lawyers seen it?

By Mr. Duncan: I would like to see it, your Honor. (Mr.

McAuliffe hands a copy of the proposed amendment to

defense attorneys). Defense counsel makes no objection to

the motion for leave to amend the warrants, your Honor.

By Judge Pugh: The motion is granted.

* * # # * * # # # #

3 By Judge Pugh: The pleas are “ not guilty?”

By Mr. Duncan: Yes, your Honor.

# * = & # # * # # # #

6 By Mr. Duncan: I would like, with the Court’s

leave, to reserve the opening statement on behalf of

the defendants, and I would like to move to dismiss and

quash the warrants. The prosecutor has stated that the ar

rests in this case were made by a State officer for the pur

pose of enforcing a policy of private segregation, put into

effect and maintained by the owner and lessee of the prem

ises involved. I submit to the Court that such use of State

power is unconstitutional. That the application of the

statute in this case is unconstitutional. The argument

being that the State may not discriminate against citizens

E14

on the ground of race and color. It may not do so directly,

and it cannot do so indirectly. I further move to dismiss

the warrants—

By Judge Pugh: The Court is not allowed to direct a

verdict on opening statements. If the Court sits without

a jury, it is sitting as a jury, and then the Court is the

Judge of the law and the facts, so, on opening statements

we do not recognize motions for a directed verdict. The

motion is over-ruled.

Whereupon,

Francis J. Collins

a witness of lawful age, called for examination by counsel

for the plaintiff, and having first been duly sworn, accord

ing to law, was examined and testified as follows, upon

7 Direct Examination

By Mr. McAuliffe:

Q. Lieutenant, will you identify yourself to the Court?

A. Francis J. Collins; 1207 E. Capitol Street, Washing

ton, D. C.

Q. Lieutenant, by whom are you employed, and in what

capacity? A. I am employed by the National Detective

Agency and we are under contract to Kebar, Inc., and

Rekab, Inc.,

# # # # * * * # * *

Q. By whom are you employed, Lieutenant Collins?

A. National Detective Agency.

Q. And where are you stationed, pursuant to your em

ployment with the National Detective Agency? A. My

present assignment is Glen Echo Amusement Park.

Q. And at Glen Echo Amusement Park from whom

8 do you receive your instructions? A. From the

Park Manager, Mr. Woronoff.

Q. And for how long have you been so assigned at the

Glen Echo Amusement Park? A. Since April 2nd, 1960.

E15

Q. What is your connection and capacity with respect

to the park special police force there? A. I am the head

of the special police force at the park.

Q. What instructions have you received from Mr.

Woronoff, the Park Manager, with respect to the operation

of the park and your duties in connection therewith?

# # # # # # # # # #

Q. Now then, Lieutenant, directing your attention to

the date June 30, 1960, did you have occasion to he at the

Glen Echo Park at that time? A. I was on duty on that

date.

Q. And the Glen Echo Amusement Park is located in

what County and State? A. Montgomery County, Mary

land.

Q. Directing your attention again to June 30,

9 1960, at a time when you were on duty at Glen

Echo Amusement Park, did you have occasion to see

the five defendants in this case on that date? A. I did.

Q. Will you relate to the Court the circumstances under

which you first observed these five defendants at the Glen

Echo Amusement Park?

10 Q. Now, Lieutenant, what first communication, or

contact, did you have with the five defendants here,

and what were they doing at that time?

By Mr. Duncan: I object, your Honor. That is the

same question, if I understand it correctly.

By Judge Pugh: The objection is over-ruled.

A. The defendants broke from the picket line and went

from the picket line—

By Judge Pugh: (interrupting the witness)

Just tell when they came on to the private property of

the Glen Echo Amusement Park.

A. Approximately 8 :15.

By Judge Pugh: All five of them?

11 A. Yes, sir.

E16

Q. What, if anything, occurred then?

By Judge Pugh: On the property of Glen Echo Amuse

ment Park.

A. The five defendants went down through the park to

the carousel and got on to the ride, on the horses and the

different animals. I then went up to Mr. Woronoff and

asked him what he wanted me to do. He said they were

trespassing and he wanted them arrested for trespassing,

if they didn’t get off the property.

Q. What did you tell them to do? A. I went to the

12 defendants, individually, and gave them five minutes

to get off the property.

By Mr. Duncan: I object and move to have that answer

stricken. I t is not relevant.

By Judge Pugh: The objection is over-ruled.

Q. Then, Lieutenant, will you relate the circumstances

under which you went to the carousel, and what you did

when you arrived there with respect to these five defend

ants? A. I went to each defendant and told them—

Q. (interrupting the witness) First of all, tell us what

you found when you arrived there. Where they were,

and what they were doing. A. Each defendant was either

on a horse, or one of the other animals. I went to each

defendant and told them it was private property and it

was the policy of the park not to have colored people on

the rides, or in the park.

Q. Now, will you look upon each of the five defendants

and can you now state and identify each of the five de

fendants' seated here as being the five that you have just

referred to? A. These are the five defendants that I just

referred to.

By Mr. Duncan: I would object to that and ask that he

be required to identify each defendant individually. These

are five separate warrants.

By Judge Pugh: Can you identify each one of these

defendants individually?

A. Yes.13

E17

By Judge Pugh:

Q. Did you tell them to get off the property! A. Yes.

Q. What did each one of them say when you told them

that! A. They declined to leave.

Q. What did they say! A. They said they declined to

leave the property. They said they declined to leave and

that they had tickets.

* # # # * = * * # # *

18 Q. During the five minute period that you testi

fied to after you warned each of the five defendants

to leave the park premises, what, if anything, did you do!

A. I went to each defendant and told them that the time

was up and they were under arrest for trespassing. I

then escorted them up to our office, with a crowd milling

around there, to wait for transportation from the Mont

gomery County Police, to take them to Bethesda to swear

out the warrants.

By Mr. Duncan: At this point I renew my Motion to

quash the warrants.

By Judge Pugh: The motion is denied.

By Mr. Duncan: May I state what the grounds are,

your Honor!

By Judge Pugh: You can state that at the end of the

case.

By Mr. Duncan: I am required to state this at the

beginning.

By Judge Pugh: You have stated your Motion and the

Court has ruled on it. You may argue it to the Court of

Appeals.

20 Mr. McAuliffe Resumes Examination of the Witness:

Q. Lieutenant, how were you dressed at the time you

approached the defendants and when you warned them!

A. I was in uniform.

Q. What uniform was that! A. Of the National Detec

E18

tive Agency; blue pants, white shirt, black tie and white

coat and wearing a Special Deputy Sheriff’s badge.

Q. What is your position, or capacity, with re-

21 spect to being a Deputy Sheriff? Are you, in fact,

a Deputy Sheriff of Montgomery County? A. I am

a Special Deputy Sheriff of Montgomery County, State

of Maryland.

Q. And specifically by what two organizations are you

employed? A. Rekab, Inc., and Kebar, Inc.

By Mr. McAuliffe: You may cross-examine.

By Mr. Duncan: Is it my understanding that this

witness’s duties have been admitted, subject to proof?

By Judge Pugh: Subject to agency. Agency has not

been established yet. I sustained the objection on that

proffer.

Cross-Examination

By Mr. Duncan:

Q. You just said you are employed by Rekab, Inc., and

Kebar, Inc., is that correct? A. I am employed by the

National Detective Agency and they have a contract with

Kebar, Inc., and Rekab, Inc.

Q. Who pays your salary? A. The National Detective

Agency.

Q. And do you have any other income from any other

source. A. No, sir.

Q. Do you receive any money directly from Rekab,

22 Inc., or Kebar, Inc.? A. No, sir.

Q. Your salary, in fact, is paid by the National

Detective Agency; is that correct? A. Yes.

Q. What kind of agency is that? A. A private detective

agency.

Q. Is it incorporated? A. Yes, sir.

Q. In what State? A. The District of Columbia.

Q. Are you an officer of that corporation? A. No, sir.

Q. Are you an officer of either Rekab, Inc., or Kebar,

Inc.? A. No, sir.

E19

Q. Mr. Collins, yon testified that you saw these defend

ants prior to the time they entered the park; is that

correct? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Had you ever seen them before? A. No, sir.

Q. When you saw them inside the park, did you recog

nize them as the persons you had seen outside the park?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now you stated that you told them it was the policy

of the park not to admit colored people. Is that, in fact,

the policy of the park? A. Yes.

23 Q. Has1 it always been the policy of the park?

A. As far as I know.

Q. How long had you worked at Glen Echo Park?

A. Since April 2, 1960.

Q. And before that time were you employed by the

National Detective Agency? A. That is right.

Q. But you were assigned to a place other than Glen

Echo? A. That is right.

Q. To your knowledge, had negroes previously ever been

admitted to the park? A. Not to my knowledge.

Q. Now did you arrest these defendants because they

were negroes?

By Mr. McAuliffe: Objection.

By Judge Pugh: Over-ruled.

A. I arrested them on orders of Mr. Woronoff, due to

the fact that the policy of the park was that they catered

just to white people; not to colored people.

Q. I repeat my question. Did you arrest these de

fendants because they were negroes? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Were they in the company of other persons, to your

knowledge? A. Yes, sir.

24 Q. Were they in the company of white persons?

A. Where?

Q. When they were on the carousel. A. There were