Smith v Morrilton School District BOE Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1966

12 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Morrilton School District BOE Reply Brief for Appellants, 1966. 19312eb5-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b0740a53-271b-473e-9d67-4ba09f6e3650/smith-v-morrilton-school-district-boe-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

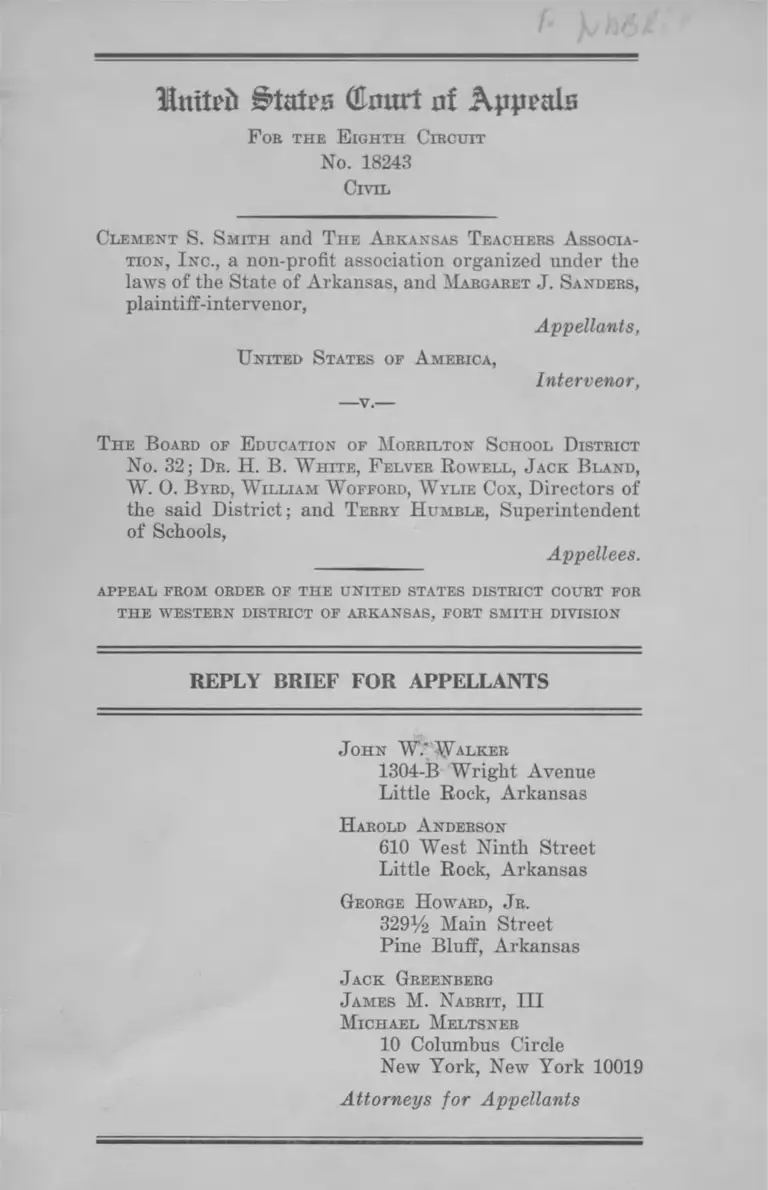

Ilntfrd States GInurt of Appeals

F ob the E ighth Circuit

No. 18243

Civil.

Clement S. S mith and T he A rkansas T eachers A ssocia

tion, I nc., a non-profit association organized under the

laws of the State of Arkansas, and Margaret J. Sanders,

plaintiff-intervenor,

Appellants,

U nited States of A merica,

— v .—

Intervenor,

T he B oard of E ducation of M orrilton School D istrict

No. 32; Dr. H. B. W hite, F elver R owell, J ack B land,

W. 0. B yrd, W illiam W offord, W ylie Cox, Directors of

the said District; and T erry H umble, Superintendent

of Schools,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM ORDER OF THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS, FORT SMITH DIVISION

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ohn W * W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

H arold A nderson

610 West Ninth Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

George H oward, Jr.

3291/2 Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

Utt!teb States (!Inurt at Appeals

F ob the E ighth Cibcuit

No. 18243

Civil

Clement S. S mith and T he A bkansas T eachebs A ssocia

tion, I nc., a non-profit association organized under the

laws of the State of Arkansas, and Maegaeet J. Sandebs,

plaintiff-intervenor,

Appellants,

U nited States of A mebica,

Intervenor,

—v.—

T he B oabd of E ducation of Mobbilton S chool D istbict

No. 32; D b. H. B. W hite, F elveb R owell, J ack B land,

W . 0 . B ybd, W illiam W offobd, W ylie Cox, Directors of

the said District; and T ebby H umble, Superintendent

of Schools,

Appellees.

APPEAL FBOM OBDEB OF THE UNITED STATES DISTBICT COUBT FOB

THE WESTEBN DISTBICT OF ARKANSAS, FOBT SMITH DIVISION

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

I.

Subsequent to the filing of appellants’ brief, the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit decided a

Negro teacher dismissal case identical to this in all ma

terial respects. The board concedes it “ is directly in point”

(appellee’s brief p. 20). In Franklin v. County School

Board of Giles County, No. 10,214, decided April 6, 1966,

2

23 Negro school children applied under a choice plan to

attend the all-white county high school. As a result, the

school board decided to abandon two Negro schools, and

notified Negro teachers that their services would not be

needed after the close of that school year. Later, the

school board employed eight new teachers, all of whom

were white.

In a suit brought by discharged teachers and the Vir

ginia Teachers Association seeking reinstatement of the

teachers, the superintendent contended that he compared

the qualifications of the Negro teachers with those of all

the other 179 teachers in the school system and concluded

that the Negroes were the least suitable for reemployment.

But the district court found that he had compared the

qualifications of the Negro teachers only as to the antici

pated vacancies. While the district court found that com

parative evaluation must include all teachers and not just

new applicants it only ordered the school board to notify

discharged teachers of any vacancy for which they were

qualified and “to offer them the opportunity to apply for

the job in competition with others who might seek employ

ment.” (Emphasis supplied)

The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reversed.

It found that no comparative evaluation of any sort was

made; that the teachers were discharged because of their

race in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and that

they are entitled to a mandatory injunction requiring their

reinstatement: “We think the individual plaintiffs are

entitled to reemployment in any vacancy which occurs for

which they are qualified by certificate or experience.”

The court in Franklin did not pass on the question of

whether the teachers were entitled to damages because

none were sought, but another recent decision of the

3

Fourth Circuit, Smith v. Hampton Training Institute, No.

10,312, decided April 28, 1966, makes clear the court’s view

that racially discharged teachers are entitled to compen

sation for denial of their constitutional rights. In Smith,

three Negro nurses were discharged by a government sub

sidized hospital after they atempted to eat in the all-white

hospital cafeteria. The Fourth Circuit, citing its decision

in Franklin, supra, directed that the nurses be reinstated

with back pay, in order to “make them whole” and to

deter racial discharges in the future.

The school board does not mention the decision of the

Court of Appeals in Franklin but attempts to distinguish

the district court decision on the ground that displaced

teachers had been retained in the school system in the past.

The record here, however, establishes the normal annual

faculty turnover and assignment practices present in that

case. Superintendent Humble conceded that vacancies had

“happened in each other year” (R. 206) and that in the

past teachers were “ retained” , “ moved” and “ transferred”

without having to apply when schools were closed (R. 169,

170, 212, 213). To be sure he testified that at the time

the high school was closed there were no vacancies (R.

170) but the point is that he could not but know that

vacancies would occur because they had “happened in

every other year.” His failure to notify the dismissed

Negroes of their supposed freedom to apply (after he

dismissed them) for the vacancies which occurred as “ in

every other year” , his still undenied racial explanation of

the firing, and his vague, but significant, description of a

Negro “ speech pattern” and manner of “communication”

(R. 200, 196-99) speak eloquently of his intentions. That

the board merely sought to exclude Negro teachers from

teaching at the “white” school and did not pass any valid

judgment on their qualifications as teachers is further

4

supported by the fact that all of the Negro high school

teachers had been notified that they would be rehired prior

to their dismissal. Thus, the attempts of the Superintend

ent to cast doubt on the ability of Negro teachers merely

reflects the different standards which he reveals holding

with respect to Negro and white pupils. In this respect

his testimony demonstrates the frame of mind Avhich

brought about a racial discharge of teachers.

Nor is Franklin distinguishable because the school sys

tem there had on prior occasions compared the qualifica

tions of all teachers in the system before dismissal. The

Fourth Circuit’s conclusion that Negro teachers were dis

charged racially does not depend on the existence of this

practice. A school board may not, consistent with the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, ad

minister a desegregation plan to cast the entire burden

of desegregation on Negro teachers. That Negro teachers

were discharged because they all taught at the same school

does not alter this conclusion for they all taught at the

same school because of the board’s unconstitutional racial

assignment policies, policies which have been unconstitu

tional for over a decade. Secondly, the board’s attempt to

treat this matter as if it were a simple question of school

closing is not acceptable because Brown v. Board of Educa

tion placed the obligation to desegregate not on particular

schools but upon area school authorities which in Arkansas,

as in other states, means the area school boards. As the

board is constitutionally responsible it cannot adopt a

plan for desegregation which burdens solely Negro teach

ers. The briefs cite numerous cases in which the federal

courts have consistently rejected desegregation standards

which, while appearing nonracial, act in an obvious way

to burden Negroes. See also Sellers v. Crook,------F. Supp.

------ , No. 2361-N (M.D. Ala) where a three judge court

5

found a legislative extension of terms of office of county

commissioners unconstitutional because it freezes into of

fice persons elected when Negroes were illegally deprived

of vote even though the extension of terms was not found

to be racially motivated.

Five pages of the board’s brief consists of a labored

attempt to suggest that race is a permissible criteria for

assignment of Negro teachers. Appellants find this at

tempt inexplicable unless the board is seeking to justify

to the Court the conceded racial assignment of teachers

which condemned only Negro teachers to discharge, while

white teachers retain their jobs even if they had less

seniority or ability. That race, constitutionally excluded

as criteria in every area of our public life, may be per

mitted at this time to infect the assignment or discharge

of teachers is a proposition too unreal to argue. Such

matters are closed as litigable issues.1

Appellants’ rights to reinstatement are further sup

ported by the Revised Statement of Policies for School

Desegregation Plans under Titile VI of the Civil Rights

Act (March 1966). These revised guidelines explicitly

direct themselves to the situation involved in this case.2

1 Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U .S. 31, 33. See for example, Cooper v. Aaron,

348 U .S . 1 (schools); Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U .S. 683 (pupil

transfer p la n ); Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U .S. 526 (public p a rk s);

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U .S . 61 (courtrooms); Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U .S . 715 (restaurants in public buildings); Peter

son v. Greenville, 373 U .S . 244 (restaurants); Simkins v. Moses H. Cone

Memorial Hospital, 323 F .2d 959 (4th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 376 U .S.

938 (hospital medical staff and patient admission).

2 The pertinent guidelines state as follow s:

$181.13 Faculty and Staff

(a) Desegregation of Staff. The racial composition of the professional

staff of a school system, and of the schools in the system, must be con

sidered in determining whether students are subjected to discrimination

in educational programs. Each school system is responsible for correcting

6

They provide that in any instance where one or more

teachers are displaced as a result of desegregation no staff

vacancy in the school system may be filled through re

cruitment from outside the system, unless the system can

the effects of all past discriminatory practices in the assignment of teachers

and other professional staff.

(b) New Assignments. Race, color, or national origin may not be a

factor in the hiring or assignment to schools or within schools of teachers

and other professional staff, including student teachers and staff serving

two or more schools, except to correct the effects of past discriminatory

assignments.

(c) Dismissals. Teachers and other professional staff may not be dis

missed, demoted, or passed over for retention, promotion, or rehiring on

the ground o f race, color, or national origin. In any instance where one

or more teachers or other professional staff members are to be displaced

as a result o f desegregation, no staff vacancy in the school system may be

filled through recruitment from outside the system unless the school officials

can show that no such displaced staff member is qualified to fill the va

cancy. I f as a result of desegregation, there is to be a reduction in the

total professional staff of the school system, the qualifications of all staff

members in the system must be evaluated in selecting the staff members

to be released.

(d) Past Assignments. The pattern of assignment of teachers and other

professional staff among the various schools of a system may not be such

that schools are identifiable as intended for students of a particular race,

color, or national origin, or such that teachers or other professional staff

of a particular race are concentrated in those schools where all, or the

majority of, the students are of that race. Each school system has a

positive duty to make staff assignments and reassignments necessary to

eliminate past discriminatory assignment patterns. Staff desegregation for

the 1966-67 school year must include significant progress beyond what was

accomplished for the 1965-66 school year in the desegregation of teachers

assigned to schools on a regular full-time basis. Patterns of staff assign

ment to initiate staff desegregation might include, for example: (1 ) Some

desegregation of professional staff in each school in the system, (2 ) the

assignment of a significant portion of the professional staff o f each race

to particular schools in the system where their race is a minority and

where special staff training programs are established to help with the

process of staff desegregation, (3 ) the assignment of a significant portion

of the staff on a desegregated basis to those schools in which the student

body is desegregated, (4 ) the reassignment of the staff of schools being

closed to other schools in the system where their race is a minority, or

(5 ) an alternative pattern of assignment which will make comparable

progress in bringing about staff desegregation successfully.

7

show that no displaced staff member is qualified to fill

the vacancy. If as a result of desegregation, there is a

reduction in the total professional staff of the system, all

staff members in the system must be evaluated in selecting

the staff members to be released. These standards clearly

apply to require reinstatement of those displaced Negro

teachers who desire it, all of whom were rehired by the

board prior to the desegregation and closing of Sullivan

high school without any evaluation of all staff members

in the system and have equal or superior qualifications

to the inexperienced teachers hired by the board. This

court has stated that the guidelines, while not binding,

are entitled to great weight, Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d

14, 18-19 (8th Cir. 1965). They are especially meaningful

in the area of faculty desegregation for the guidelines

represent the product of educational expertise and an

awareness of national patterns of Negro teacher dismissal.3

II.

The school board also urges that the suit cannot he

prosecuted as a class action, and that the corporate plain

tiff, the Arkansas Teachers Association, is not a proper

party. First, it is obvious that Negro teachers in Arkansas

have a common interest in ending racial dismissal as a

consequence of pupil desegregation and that their incor

porated teachers’ association may represent that interest,

as well as sue in its own right in order to protect its own

welfare. See appellants’ brief note 1; Franklin v. County

School Board of Giles County, supra; Buford v. Morgan-

3 Significantly, at least two district courts had fashioned orders com

parable to the guidelines before the Office of Education adopted them.

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F . Supp. 971, 977-8 (W .D .

Okla. 1 9 6 5 ); Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County, Va 249

F . Supp. 239, 247 (W .D . Va. 1966).

8

ton Board of Education, 244 F. Supp. 437, 445 (W.D. N.C.

1965); cf. NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449, 468-9; Pierce

v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, 535. Significantly, the

cases cited by the board were decided prior to NAACP

v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 428 (1963) which puts beyond

question the power of the Arkansas Teachers Association

to sue.

The argument that the interests of Negro teachers

are antagonistic is without merit. They have a common

interest in the relief sought here to redress the racial

dismissal policy of the board. The board also cites cases

where it was not “ impracticable” to join all persons in

the class as parties. There are just as many decisions

holding that similar numbers of persons were sufficient

to support a class action brought by “ representatives” of

the class. See e.g., Citizens Banking Co. v. Monticello

State Bank, 143 F.2d 261 (8th Cir. 1944) (12 note holders

permitted to represent 28 others in class action). The

court need not decide the application of Rule 23(a)(3) to

this suit for the Arkansas Teachers Association (because

it represents its members) and the United States are

parties entitled to relief protecting the rights of the

affected class. The cases and commentators agree, how

ever, that the test of whether a class action may be brought

has nothing to do with a “numbers game” , but “ only the

difficulty or inconvenience of joining all members of the

class” or the burden caused by litigating the issues in

volved in a piecemeal fashion by numerous suits. Ad

vertising Special National Association v. Federal Trade

Commission, 238 F.2d 108, 119 (1st Cir. 1956). “ The fed

eral decisions . . . [reflect] a practical judgment on the

particular facts of the case” 3 Moore’s Federal Practice,

§2305, p. 3421.

9

It is obviously inconvenient and unnecessary to require

that all Negro teachers affected be brought before the

court as party-plaintiffs, especially when all do not wish

to be named plaintiffs, and clearly burdensome to the

court to settle piecemeal the legal obligations of the school

board with respect to Negro teachers. Joinder of named

plaintiffs is also unnecessary because concededly common

questions of law and fact are involved as to all Negro

teachers discharged. If the Court held that appellants

were entitled to relief because the board had dismissed

them racially but that they could not maintain a class

action, the plain consequence of such a ruling would be

that each and every other Negro teacher dismissed could

bring an individual suit in the district court alleging the

racial discharge and praying for reinstatement. They

would each be clearly entitled to this relief but the dis

trict court would have to hear separate suits involving

a repetition of testimony and argument already presented

to the court. The class action provision of the Federal

Rules were formulated to avoid such results so obviously

wasteful of the energy of the judiciary.

While the class action provisions of Rule 23 facilitate

the presentation of the claims of Negro teachers and would

save the time of the court, the granting of class relief

does not prejudice the board in any manner. This is a

“ spurious” class action brought under Rule 23(a)(3)

where “the class is formed solely by the presence of a

common question of law or fact” 3 Moore’s Federal Prac

tice, §23.10, p. 3443, and “ the judgment binds only the

original parties of record and those who intervene and

become parties to the action.” Id. at p. 3456. In addition,

should relief be granted to named parties the decree,

regardless of its terms, could not expressly or impliedly

authorize continued discrimination. See Potts v. Flax, 313

10

F.2d 284, 288-90 (5th Cir. 1963). The class action decree

is therefore a convenient device for “cleaning up” this

litigious situation and informing the board of its general

obligation to Negro teachers.

Respectfully submitted,

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

H arold A nderson

610 West Ninth Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

George H oward, J r.

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C.