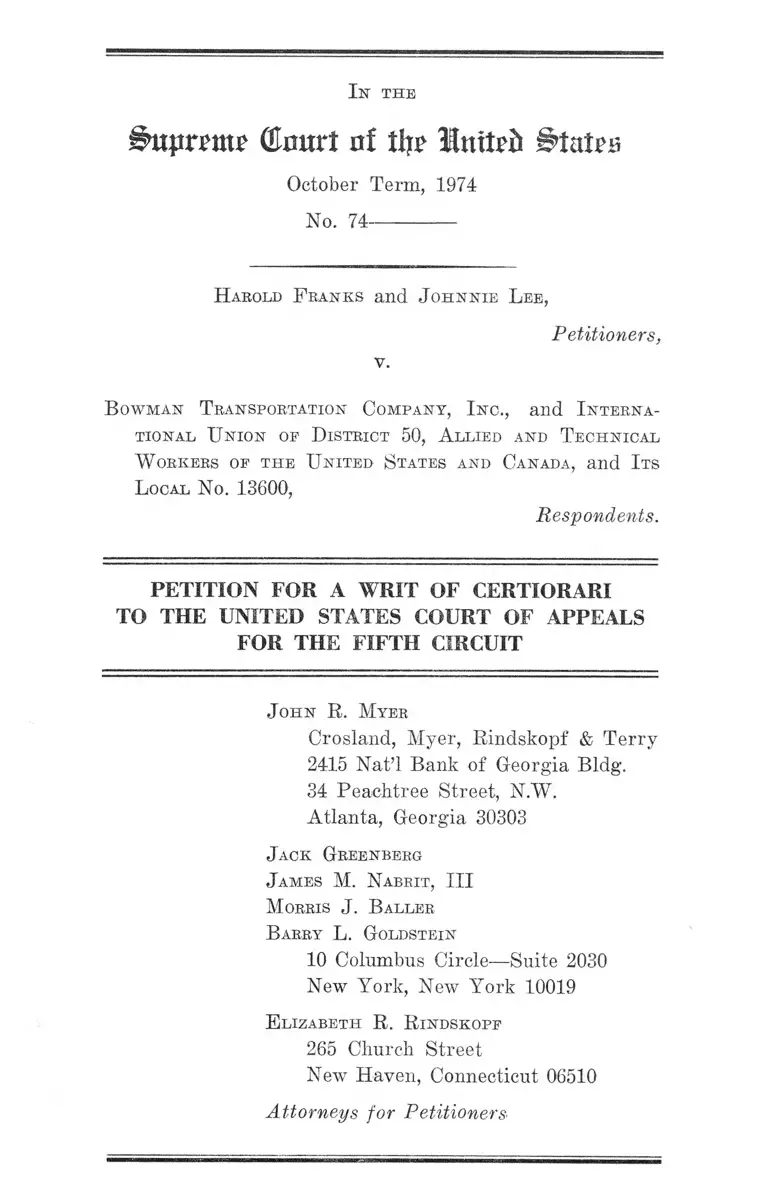

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1974. 645d2c6c-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b077dd88-93f1-4452-89e5-0755d9baa466/franks-v-bowman-transportation-company-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

iuiprrutc (ta r t of iljr Itnitrit Stains

October Term, 1974

No. 74-----------

H arold F r a n k s a n d J o h n n ie L e e ,

v.

Petitioners,

B o w m an T ra n sportation C o m pa n y , I n c ., a n d I n t e r n a

tio n a l U n io n op D istr ic t 50, A llied and T e c h n ic a l

W orkers op t h e U n it e d S tates and Canada, a n d I ts

L ocal N o. 13600,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J o h n R . M yer

Crosland, Myer, Rindskopf & Terry

2415 Nat’l Bank of Georgia Bldg.

34 Peachtree Street, N.WT.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

J ack G reenberg

J a m es M. N a brit , III

M orris J . B aller

B arry L. G oldstein

10 Columbus Circle—Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

E l iz a b e t h R. R in d sk o pf

265 Church Street

New Haven, Connecticut 06510

Attorneys for Petitioners'

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinions Below .........................

Jurisdiction .................................

Question Presented ....................

Statutory Provisions Involved ...

Statement of tlie Case ...............

R easons for G r a n t in g t h e W r it

I. The Petition Presents an Important Unresolved

Issue of Statutory Interpretation Affecting

Thousands of Persons Injured by Employment

Discrimination ...................................................... 8

II. The Court of Appeals Decision Is in Conflict

With the Remedial Purpose of Title VII and

With the Whole Scheme of Federal Labor Law 10

III. Neither the Statutory Language Nor the Legis

lative History Supports the Result Reached by

the Court of Appeals ........................ 19

IV. The Court of Appeals Decision Conflicts With

Authorities Holding That Title VII Does Not

Limit Remedies Available Under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 .................................................................... 21

1

2

2

2

PAGE

C o n clu sio n 23

11

A ppe n d ix page

Decision of the Court of Appeals ......................... A1

Judgment of the Court of Appeals .......................A42

Order of the Court of Appeals Denying Petition

for Rehearing ............. ...................................... A43

Order of the Court of Appeals Denying Petition

for Rehearing .......................................................A44

Opinion of the District Court .................................A45

Order and Decree of the District Court ...............A65

Judgment of the District C ourt............................. A69

Cases:

Aeronautical Industrial District Lodge 727 v. Camp

bell, 337 TJ.S. 521 (1949) ...........................................18,19

Afro-American Patrolmen’s League v. Duck, 366 F.

Supp. 1095 (N.D. Ohio 1973), aff’d in pertinent part

503 F.2d 294 (6th Cir. 1974) ................................... 14

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 39 L. Ed.2d 147

(1974) ...................................... 11,22

Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F. Supp. 1134 (S.D. Ala.

1971), aff’d per curiam 466 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied 412 U.S. 909 (1973) ............................ 14

Atlantic Maintenance Co. v. N.L.R.B., 305 F.2d 604

(3rd Cir. 1962), enf’g 134 NLRB 1328 (1961) ...... 17

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir. 1971),

cert, denied 404 U.S. 854 (1971) ............................ 22

Corning Glass Works v. Brennan, 41 L.Ed.2d 1

(1974) ...... .......,.......... ................................................ 12

Crosslin v. Mountain States Tel. & Tel. Co., 400 U.S.

1004 (1971), vacating and remanding 422 F.2d 1028

(9th Cir. 1970) ........................................................... 8

13

Dobbins v. Electrical Workers, Local 212, 292 F. Snpp.

413 (S.D. Ohio 1968), aff’d as later modified 472

F.2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973) ..........................................

EEOC v. Plumbers, Local Union No. 189, 311 F. Supp.

468 (S.D. Ohio 1970), vac’d on other grounds 438

F.2d 408 (6th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 404 U.S. 832

(1971) ............................................... .......................... 13

Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, 345 U.S. 330 (1953) ...... 18

Golden State Bottling Co. v. N.L.R.B., 38 L.Ed.2d 388

(1973), aff’g 467 F.2d 164 (9th Cir. 1972) ........ .....16,19

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ....8,11,21

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Co., 498 F.2d 641 (5th

Cir. 1974) .................................................................... 21

Harper v. Mayor of City Council of Baltimore, 359

F. Supp. 1187 (D. Md. 1973), aff’d sub noni. Harper

v. Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134 (4th Cir. 1973) .............. 15

Head v. Timken Boiler Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870

(6th Cir. 1973) ........................................................... 12

Jersey Central Power & Light Co. v. Electrical Work

ers, Local 327, 8 EPD 1)9759 (D.N.J. 1974) .............. 14

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., O.T. 1974

No. 73-1543 ................................................................ 21

Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 7 EPD 1)9066

(W.D. Okla. 1973) ................ 9

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) .................... 22

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paper-workers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert.

denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970) ................................12,15,20

Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972) ..................... 8

IV

Macklin v. Spector Motor Freight Systems, Inc., 478

F.2d 979 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ....................................... 21

McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) 8

N.L.R.B. v. Cone Brothers Contracting Co., 317 F.2d

3 (5th Cir. 1963) .......... ............................................... 17

N.L.R.B. v. Lamar Creamery Co., 246 F.2d 3 (5th Cir.

1957), enfg 115 NLRB 1113 (1956) ........................ 17

N.L.R.B. v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co., 304 U.S.

333 (1938) .................................................................. 16

N.L.R.B. v. Rutter-Rex Mfg. Co., 396 U.S. 258 (1969).... 16

N.L.R.B. v. Transport Co. of Texas, 438 F.2d 258 (5th

Cir. 1971) ................ 16

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974) ..........................................................12,16

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 313 U.S. 177

(1941) ................................................................... 16,17,19

Phillips v. Martin-Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971) 8

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D.

Ya. 1969) .................................................. .......... 12,13,20

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.

1971), cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) .............. 12

Rock v. Norfolk & Western Ry. Co., 473 F.2d 1344

(4th Cir. 1973), cert, denied 412 U.S. 933 (1973) .... 12

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th

Cir. 1972) .................................................................... 14

Southport Co. v. N.L.R.B., 315 U.S. 100 (1942) .......... 16

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652

(2nd Cir. 1971) ........................................ .................12, 20

United States v. Borden Co., 308 U.S. 188 (1939) ...... 22

PAGE

PAGE

United States v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 471 F.2d

582 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied 411 TJ.S. 939

(1973) .......................................... ........... ..... .......... ..12,

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 3 EPD 1J8318

(X.!). Ga. 1971) .............. .............................. ............

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th

Cir. 1973) ................... ........... ............. .......... ............ 9,

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 7 EPD 1(9167

(X.i). Ga. 1974) ...................... ........... .......................

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d

418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 406 U.S. 906 (1972)

United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ..........

United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354

(8th Cir. 1973) ......... ............................... ..................

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 416

F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969) .......................................13,

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 280

F. Supp. 719 (E.D. Mo. 1968) ...... ............................

Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., 451 F.2d 1236 (5th Cir.

1971) ...........................................................................

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., 503 F.2d 1309 (7th Cir. August 26,

1974) .......... .................................................................

Watkins v. United Steel Workers of America, Local

No. 2369, 369 F. Supp. 1221 (E.D. La. 1974) ..12,13,1.4,

Statutes and Rule:

5 U.S.C. §3502 (1966) ................................. ................

29 U.S.C. §160(c) [Section 10(c), National Labor

Relations Act] ..........................................................

20

6

16

9

12

11

12

20

13

11

20

22

18

15

VI

42 U.S.C. §1981 [Civil Eights Act of 1866] ..-2,4,8,21,22

42 U.S.C. §1982 ........................................................... - 22

42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq. [Title VII, Civil Rights Act

of 1964] ...........................2,5,7,9,12,14,15,17,19,20,22

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a) .................................................... 2

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(e) .................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h) [Section 703(h) of Title VII] .... 3, 7,

9,11,15,19, 20, 21, 22

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g) [Section 706(g) of Title VII] -4,10,

11,12,16,19, 20, 21

42 U.S.C. §§3601 et seq. [Fair Housing Act of 1968] — 22

50 U.S.C. App. §§301 et seq. [Selective Training and

PAGE

Service Act of 1940] .................................................. 17

50 U.S.C. App. §§451 et seq. [Selective Training and

Service Act of 1948] ................................................ 17

50 U.S.C. App. §459(c) (1967) ................... ................ 18

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23(b)(2) ...... 6

National Labor Relations Act [29 U.S.C. §§151 et seg.] 15,

16,17,18,19

Other Authorities:

Cong. Rec, S. 1526 (daily ed. February 19, 1972) ...... 22

Cong. Rec. S. 1797 (daily ed. February 15, 1972) ...... 22

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A General Approach to Objec

tive Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82 I I arv. L.

R ev . 1598 (1969) ..................................................... 13, 21

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 7th

Annual Report for Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1972 9

Vll

PAGE

Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Committee on

Labor and Public Welfare, Legislative History of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972

(1972) ...................................................................... . 11

S. Rep. No. 415, 92nd Congress, 1st Session (1971) .... 22

I n t h e

g>upmw> (tart of % luitrfli States

October Term, 1974

No. 74-----------

H arold F r a n k s a n d J o h n n ie L e e ,

v.

Petitioners,

B ow m an T ransportation C o m pa n y , I n c ., a n d I n t e r n a

tio n a l U n io n op D istr ic t 50, A ll ie d and T e c h n ic a l

W orkers of t h e U n ited S tates and C anada, a n d I ts

L ocal N o. 13600,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners, Harold Franks and Johnnie Lee, respect

fully pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review the

judgment and opinion of the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fifth Circuit entered in this proceeding on

June 3, 1974.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, reported at 495

F.2d 398, is reprinted in the Appendix hereto at pp. A1-A41.

The Order of the Court of Appeals denying Petitioners’

Petition for Rehearing, reported at 500 F.2d 1184, is re

printed in the Appendix at p. A44. The unreported opin

2

ion, decree, and judgment of the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Georgia are reprinted

in the Appendix at A45-A70.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

June 3, 1974. Petitioners’ timely Petition for Rehearing

was denied on September 12, 1974. Jurisdiction is in

voked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether in an action based on Title VII and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 the district courts are prohibited as a matter of

law from granting, as part of the remedy to black job

applicants unlawfully refused employment, the full senior

ity they would have obtained but for the employer’s dis

crimination!

Statutory Provisions Involved

The pertinent sections of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., as amended, provide:

Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a):

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any in

dividual, or otherwise to discriminate against any in

dividual with respect to his compensation, terms, con

ditions, or privileges of employment, because of such

individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national or

igin; or

3

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or

applicants for employment in any way which would

deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employ

ment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his

status as an employee, because of such individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Section 703(c), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(c):

It shall he an unlawful employment practice for a

labor organization—

(1) to exclude or to expel from its membership, or

otherwise to discriminate against, any individual be

cause of his race, color, religion,, sex, or national or

igin;

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify its membership or

applicants for membership, or to classify or fail or

refuse to refer for employment any individual, in any

way which would deprive or tend to deprive any in

dividual of employment opportunities, or would limit

such employment opportunities or otherwise adversely

affect his status as an employee or as an applicant for

employment, because of such individual’s race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin.

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h):

Notwithstanding any other provision of this title, it

shall not be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer to apply different standards of compensa

tion, or different terms, conditions, or privileges of

employment pursuant to a bona, fide seniority or merit

system, or a system which measures earnings by quan

tity or quality of production or to employees who work

in different locations, provided that such differences

are not the result of an intention to discriminate be

cause of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

4

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. $2000e-5(g):

If the court finds that the respondent has inten

tionally engaged in or is intentionally engaging in an

unlawful employment practice charged in the com

plaint, the court may enjoin the respondent from en

gaging in such unlawful employment practice, and

order such affirmative action as may be appropriate,

which may include, hut is not limited to, reinstatement

or hiring of employees, with or without back pay (pay

able by the employer, employment agency, or labor or

ganization, as the case may be, responsible for the

unlawful employment practice), or any other equitable

relief as the court deems appropriate. . . . No order of

the court shall require the admission or reinstatement

of an individual as a member of a union, or the hiring,

reinstatement, or promotion of an individual as an em

ployee, or the payment to him of any back pay, if such

individual was refused admission, suspended, or ex

pelled, or was refused employment or advancement or

was suspended or discharged for any reason other than

discrimination on account of race, color, religion, sex,

or national origin or in violation of section 704(a).

The Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons

and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall

be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes,

licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

5

Statement o f the Case

This class action filed in the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Georgia on May 5, 1971, chal

lenged practices of racial discrimination in employment by

Respondents Bowman Transportation, Inc,, and Local No.

13600, in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., and 42 U.S.C. § 1981. Peti

tioner Franks, a discharged former employee of Bowman,

alleged that Respondents had engaged in across-the-board

practices of racial discrimination in employment. Peti

tioner Lee, a rejected job applicant who was later hired

and discharged by Bowman, intervened in the case and

filed a similar class action complaint on July 21, 1971.

The district court found that Petitioner Franks had

been discriminatorily denied promotion to better jobs re

served for whites and discriminatorily discharged in 1968

for filing an EEOC charge alleging promotional discrimina

tion (A55-A56), and that Bowman’s initial refusal to hire

Petitioner Lee as an over-the-road (OTR) driver in Janu

ary, 1970, was racially motivated (A59-A60, A63). The

district court also found that Respondents had engaged in

a comprehensive program of racial discrimination until

after suit wras filed (A46-A52).1

With respect to OTR jobs, the court found that Bowman

followed “an unwritten policy” against hiring black ap

plicants ; that no black OTRs were employed anywhere in 1

1 Prior to 1968, Bowman maintained completely segregated jobs

and departments, with almost no black employees anywhere in the

Company (A47-A48). By August, 1971 (after suit was filed)

Bowman still had only a token few blacks in most job categories

and none at all in several of the more desirable positions (A48).

Bowman refused to allow transfers, which effectively locked blacks

into their few inferior jobs (A47, A51). Blacks were consistently

relegated to the lower paying positions (A48-A49).

6

the Company until September, 1970 ;2 3 and that prior to the

first hiring of blacks as OTRs, experienced and apparently

qualified black applicants had sought OTR jobs (A50).s

The court held the case maintainable as a class action under

Rule 23(b)(2), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (A53). It

allowed Petitioner Lee to represent a subclass, denominated

“Class 3”, consisting of all black OTR applicants who ap

plied prior to January 1, 1972 (A53, A66). Finding that

members of this subclass had been discriminatorily denied

OTR opportunities, the court granted them “preferential

re-application rights” to renewed and non-discriminatory

consideration for the OTR job (A66-A67). It rejected Peti

tioners’ demand that such discriminatees, if subsequently

hired, be g*ranted OTR seniority back to the date when they

would have been hired but for Bowman’s discrimination.4 *

On Petitioners’ appeal, the Court of Appeals affirmed all

the trial court’s findings of discrimination,6 found certain

2 Bowman employed no blacks and 415 whites as OTRs in July,

1965; no blacks and 464 whites as OTRs in March, 1968; and 11

blacks (all at one of the four OTR terminals) and 499 whites as

OTRs in August, 1971 (A48). At the time of trial (March, 1972),

Bowman’s OTR workforce was only 3.3% black (A18 n .ll , cf.

A50).

3 The record shows that Bowman rejected 196 black OTR ap

plicants in 1970-1971 alone. Of these, 115 list truck driving ex

perience on their applications which meets Bowman’s basic stan

dards; Bowman verified the claimed experience of at least 48

black applicants whom it nevertheless rejected.

Two black rejected OTR applicants other than Lee testified at

trial. The court found that each was “experienced and not obvi

ously disqualified” but had been discriminatorily rejected (A50).

4 The court expressly relied on its reasoning on the back pay

issue in United States v. Georgia Power Co., 3 EPD 1(8318 (N.D.

Ga. 1971) (A53-A54) ; that decision was subsequently reversed,

474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973).

6 With respect to the OTR hiring issue, the Court of Appeals

held,

The record in this case shows that Bowman followed a con

scious policy of excluding blacks from its OTR Department

7

other practices unlawful (A15-A20), and held that Peti

tioners were entitled to affirmative injunctive relief as well

as class back pay (A24-A40).* 6 But the Court of Appeals

rejected Petitioners’ request for full seniority relief for

blacks previously refused hiring, who successfully re-apply

for OTP jobs (members of “Class 3”).7 Characterizing the

remedy sought as “a giant step beyond permitting job com

petition on the basis of company seniority” and as “con

structive seniority” (A29-A30), the Court held that Section

703(h) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h), precludes such

relief as a matter of law (A30-A31). The Court based its

conclusion on the view that a seniority system is “bona

Me” and therefore protected by Section 703(h) regardless

of the prior unlawful exclusion of blacks from sharing the

benefits of that system.8

until September 1970, a time over five years after the effec

tive date of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The District Court

found that Bowman, although aware of its legal obligations,

intentionally continued to follow its discriminatory policy

and put off hiring black OTR drivers as long as it could

(A31).

6 Respondent Bowman's Petition for a W rit of Certiorari pre

senting the class back pay issue, No. 74-424, was denied on Decem

ber 9, 1974.

7 The record does not reveal how many persons are in this group

because the district court denied Petitioners’ request for retained

jurisdiction and reporting provisions. (The Court of Appeals

ordered the request granted, A37.) 212 members of “Class 3”

were sent notice inviting them to re-apply for priority considera

tion for OTR jobs, pursuant to the decree (A 67); presumably at

least some were hired if Bowman had abandoned its policy of

racial exclusion.

8 The Court of Appeals did not base its decision on the same

reasons as the district court; it rejected those grounds in its dis

cussion of the back pay issue (A37-A39).

8

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The Petition Presents an Important Unresolved Issue

of Statutory Interpretation Affecting Thousands o f Per

sons Injured by Employment Discrim ination.

The critical issues of employment discrimination law at

present involve remedies. This Court has decided Title VII

cases involving procedural questions,9 and cases defining

standards for proof of discrimination.10 This case brings

to the Court an important question involving the scope of

remedial authority vested in the district courts once dis

crimination is established. The Court of Appeals decision

resolved that question in a manner which conflicts in prin

ciple with decisions of this Court and lower courts.

The decision below would severely limit courts’ power

and EEOC’s authority to grant effective relief to thousands

of victims of unlawful hiring discrimination (I, infra).

That restriction is inconsistent with numerous decisions in

employment discrimination cases and other fields of labor

law and with the remedial purpose of Title VII (II, infra).

Nothing in the language or legislative history of Title VII

requires or supports the restriction (III, infra). In any

event, a limiting interpretation of Title VII’s provisions

should not bar relief under 42 U.S.C. §1981 (IV, infra).

The Court of Appeals decision interposes a general pro

hibition on seniority relief for victims of hiring diserim-

9 See, e.g., Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972) ; and Cross

lin v. Mountain States Tel. & Tel. Co., 400 U.S. 1004 (1971),

vacating and remanding 422 F.2d 1028 (9th Cir. 1970).

10 See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971);

Phillips v. Martin-Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971) ; McDon-

nell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973).

9

ination. The Court found a barrier not in the circumstances

of the case, but in the terms of Section 703(h) of Title VII,

42 TJ.S.C. §2000e-(h). If that decision stands, no court

may grant any job applicant rejected because of race, sex,

religion, or national origin—whatever the circumstances—

hiring with the seniority the applicant would have acquired

but for the discriminatory rejection.

The prohibitory effect of the decision will cut back on

relief now being obtained, or that could be obtained, in

many cases. In several Title YII cases, the United States

Department of Justice has secured decrees granting com

pensatory seniority to unlawfully rejected applicants.11 The

United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(EEOC) has filed 306 pending lawsuits, 174 of which seek

relief from discrimination in hiring [information supplied

by EEOC Litigation Services Branch, December 5, 1974],

And EEOC has thousands of pending administrative

charges of discrimination involving refusals to hire.11 12 13 In

conciliating, settling, or litigating these claims, EEOC’s

remedial effectiveness may be limited by the decision be

low.18 Many private plaintiffs’ refusal-to-hire suits will also

be adversely affected.

11 See, e.g., United States v. Georgia Power Co., 7 EPD f9167

(N.D. Ga. 1974) at p. 6885, issuing decree on remand from 474

F. 2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973) ; Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc.,

7 EPD lf9066 (W.D. Okla. 1973) at p. 6500.

12 EEOC’s 7th Annual Keport for Fiscal Year ended June 30,

1972 (its most recent) shows that 8,836 charges of hiring discrim

ination were received in fiscal year 1972. In fiscal year 1974,

14,866 actionable charges of hiring discrimination were filed (per

information supplied by EEOC Systems Control Branch, Decem

ber 2, 1974). No available data shows how many charges involve

jobs to which seniority applies, but the percentage is doubtless

substantial.

13 EEOC’s authority derives solely from Title YII. Thus, a

limitation read into Title VII may hamstring EEOC in all its

proceedings.

10

The principle announced below would permanently dis

able the federal courts from even entertaining claims for

relief from discriminatory seniority-based layoff practices.

Layoffs due to reduction in force are a recurrent feature

of the American economy, as exemplified in the current

recession. Such layoffs in industry are commonly controlled

by the “last hired, first fired” principle. Where racial or

other minorities were “last hired” because of discrimina

tion, that principle raises significant employment rights

issues. If allowed to prevail, the decision below would

prohibit courts from, addressing those issues, by exempt

ing employment seniority systems from modification re

gardless of their effects and circumstances.

II.

The Court o f Appeals D ecision Is in Conflict With

the Remedial Purpose o f Title VII and With the W hole

Scheme o f Federal Labor Law.

A. In Section 706(g) of Title VII, 42 IJ.S.C. §2000e-5(g),

Congress gave the courts broad equitable powers to rem

edy employment discrimination. The provision authorizes

courts to enjoin such discrimination “and order such af

firmative action as may be appropriate, which may include,

but is not limited to, reinstatement or hiring of employees

. . . or any other equitable relief as the court deems ap

propriate.” In 1972 a Conference Committee of the Senate

and House reiterated Congress’s intent to give courts ple

nary remedial powers:

The provisions of this subsection [706(g)] are intended

to give the courts wide discretion exercising their

equitable powers to fashion the most complete relief

possible. In dealing with the present section 706(g)

the courts have stressed that the scope of relief under

11

that section of the Act is intended to make the victims

of unlawful discrimination whole, and that the attain

ment of this objective rests not only upon the elimina

tion of the particular unlawful practice complained

of, but also requires that persons aggrieved by the

consequences and effects of the unlawful employment

practice be, so far as possible, restored to a position

where they would have been were it not for the un

lawful discrimination, [emphasis added]

Section-by-Section Analysis of H.R. 1746, reprinted by

Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Committee on Labor

and Public Welfare in Legislative History of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (1972), pp. 1844,

1848. See Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 39 L.Ed. 2d

147, 157-158 (1974). The only limitation on the grant of

remedial authority is found in Section 706(g) itself: no

such relief may be granted in the absence of a finding of

discrimination.

The Court of Appeals did not doubt that respondent

Bowman had engaged in discrimination made unlawful by

Section 703(a), requiring a grant of relief under Section

706(g), or that class 3 members lost jobs as a result

(A30). Nevertheless it barred full seniority relief on the

basis of Section 703(h), which does not by its terms de

fine or restrict available remedies but rather specifies what

constitutes an unlawful practice.

The Court’s theory in borrowing from Section 703(h)

to narrow the scope of Section 706(g) is incompatible with

federal courts’ duty to grant effective relief from racial

discrimination. Such relief must include affirmative mea

sures designed to eradicate, insofar as possible, all the

continuing effects of past discrimination.14 The decision

14 United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965); Griggs

v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 429-430 (1971) ; Vogler v.

12

below denies such effective relief. It subjects rehired class

3 members, because of their inferior seniority status, to

a variety of obstacles to full employment opportunities.15

The courts have not previously hesitated to modify se

niority systems where necessary to eliminate the present

effects of past discrimination as mandated by Section

706(g). In the line of cases fathered by Quarles v. Philip

Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Ya. 1969), and Local

189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S.

919 (1970), the courts have required substitution of date-

of-hire (“company” or “plant”) seniority for unit seniority

to allow segregated black employees equal access to jobs

in formerly all-white units.16 These decisions adopt em

ployment date as a nondiscriminatory seniority standard

not because it is per se valid but because it accomplishes

the remedial purpose of Title VII. The instant case re

quires a different remedy under the same principles be

cause of a crucial factual difference—the existence of an

all-white workforce. See Watkins, v. United Steel Workers

McCarty, Inc., 451 F.2d 1236, 1238 (5th Cir. 1971); Pettway v.

American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211, 243 (5th Cir. 1974);

Bock v. Norfolk & Western By. Co., 473 F.2d 1344 (4th Cir.

1973), cert, denied 412 U.S. 933 (1973). Cf. Corning Glass Works

v. Brennan, 41 L.Ed.2d 1 (1974).

15 Under the Respondents’ collective bargaining agreement,

choice of driving assignments and shifts, exposure to layoff during

reduction-in-force, and rights to recall are controlled by OTR

seniority.

16 See, e.g., United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652

(2nd Cir. 1971); Bobinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th

Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1971); United States

v. Chesapeake & Ohio By., 471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972), cert,

denied 411 U.S. 939 (1973); United States v. Jacksonville Termi

nal Co., 451 F.2d 418 (5th. Cir. 1971), cert, denied 406 U.S. 906

(1972) ; Head v. Timken Boiler Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870 (6th

Cir. 1973); United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354

(8th Cir. 1973).

13

of America, Local No. 2369, 369 F. Supp. 1221, 1231 (E.D.

La. 1974), and Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing

Under Fair Employment Laws: A General Approach to

Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82 H abv. L.

R ev . 1589, 1629 (1969) [hereinafter cited as Cooper and

Sobol]. The denial of authority to grant such remedy

places the decision below in conflict with the Quarles-Local

189 line.17

Date-of-hire seniority is not a sacrosanct principle where

it perpetuates discrimination. In cases involving union

work-referrals, the courts have expressly rejected use of

employment seniority or longevity of membership or ser

vice. Such seniority, they reason, is unavailable to black

workers because of past policies of exclusion and there

fore carries into the present the consequences of past dis

crimination. United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Iwcal

36, 416 F.2d 123, 131 (8th Cir. 1969) ;18 Dobbins v. Elec

trical Workers Local 212, 292 F. Supp. 413 (S.D. Ohio

1968), aff’d as later modified, 472 F.2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973);

EEOC v. Plumbers, Local Union No. 189, 311 F. Supp.

468, 474-476 (S.D. Ohio 1970), vac’d on other grounds 438

F.2d 408 (6th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 832 (1971).

These decisions require referral of black employees despite

their lack of longevity, and in effect modify the employ

17 The ruling below brings an anomalous result. The most dis

criminatory employers, who like Bowman have totally excluded

blacks, are subjected to less a complete remedy than other em

ployers who have hired blacks into segregated units. Such a rul

ing places a premium on total resistance to law. See, e.g., Watkins v.

United Steel Workers of America, Local No. 2369, supra, 369 F.

Sup. at 1229.

18 The Local 36 opinion reverses and expressly rejects a district

court holding that the referral system was a non-diseriminatory

seniority system and therefore immune from revision, 280 F. Supp.

719, 728-730 (E.D. Mo. 1968). The Eighth Circuit agreed that a

seniority system was at stake, but held it non-bona fide and un

lawful, 416 F.2d at 133-134 and n. 20.

14

ment seniority system. The same modification was held

beyond the Court’s power in the instant case.

The opinion below conflicts with decisions involving pro

motional and layoff rights.19 At least two courts have re

quired modification of a layoff system based on date-of-hire

seniority, where blacks had until recently been refused em

ployment. In Watkins v. United Steel Workers of America,

Local No. 2369, supra, 369 F. Supp. at 1226, the Court held

that “employment preferences cannot he allocated on the

basis of length of service seniority, where blacks were,

by virtue of prior discrimination, prevented from accumu

lating relevant seniority.” It therefore found layoff and

recall practices based on actual hire date discriminatory

under Title VII, id. at 1223. In Jersey Central Power &

Light Co. v. Electrical Workers, Local 327, 8 EPD 1J9759

(D.N.J. 1974), the court held that a seniority clause based

on employment date had to be accommodated to avoid prej

udice to recently hired black employees in a reduction-in

force. Similarly, the courts have invalidated length-of-

service as a factor in promotions, where blacks were pre

viously denied hiring. Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457

F.2d 348, 358 (5th Cir. 1972) (“ [the defendant] could not

. . . treat the recently hired and governmentally twice

emancipated Blacks as persons who once again had to go

to the foot of the line”) ; Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F.

Supp. 1134, 1142-1143 (S.D. Ala, 1971), aff’d per curiam

466 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied 412 U.S. 909

(1973) (holding use of service seniority credits unlawful);

Afro-American Patrolmen’s League v. Duck, 366 F. Supp.

1095, 1102 (N.D. Ohio 1973), aff’d in pertinent part 503

19 This case did not present the layoff issue on its facts. How

ever, the Fifth Circuit’s broad holding would seem to exempt a

“last hired, first fired” layoff system from modification without

regard to its impact on black workers or its business justification.

15

F.2d 294 (6th Cir. 1974); Hamper v. Mayor and City Council

of Baltimore, 359 F. Supp. 1187, 1203-1204 (D. Md. 1973),

aff’d sub nom Harper v. Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134 (4th Cir.

1973).

The holding below cannot be reconciled with any of the

foregoing employment discrimination cases. In requesting

retroactive seniority to the date when Class 3 members

would have been hired but for discrimination, Petitioners

merely seek to eliminate the present discriminatory impact

of Respondents’ seniority system on unlawfully rejected

applicants.20 The Court of Appeals rejected Petitioners’

request because it viewed Section 703(h) as placing be

yond remedy a seniority system founded on employment

date. Yet none of the other decisions finds employment

seniority per se consistent with Title VII,21 and many ex

pressly reject such seniority.

B. The Court of Appeals’ decision also conflicts with

labor law decisions of this Court which define the nature of

appropriate relief under Section 10(c) of the National

Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. § 160(c). The conflict is par

ticularly significant because Section 10(c) served as the

20 Indeed this ease is more compelling than the decisions involv

ing use of seniority in work referrals, layoffs and recalls, or

promotions. In those cases the beneficiaries of the courts’ holdings

had not themselves been rejected applicants; in the absence of

discrimination they might not have personally obtained the posi

tion granted them by court order. Petitioners seek only restora

tion of the seniority rights they would have individually enjoyed

if Respondents had not violated the law.

21 The Court of- Appeals’ reliance on the rejection of “fictional

seniority” in Local 189, 416 F.2d at 994-995, is misplaced. Judge

Wisdom’s dicta are addressed to the propriety of giving a remedy

to persons whose rejection before enactment of Title VII was not

then unlawful. Judge Wisdom also questioned whether remedies

should be granted to new employees who were not themselves the

victims of past discrimination. Neither of these problems is

present in the instant case.

16

model for Title VII’s remedial provision, Section 706(g),

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g).22

This Court has consistently held in NLRA cases that a

person unlawfully deprived of employment should be placed

in the same position he would have occupied but for the

unlawful discrimination. N.L.R.B. v. Rutter-Rex Mfg. Co.,

396 U.S. 258, 263 (1969). A remedy that leaves him “worse

off” is inadequate, id; Golden State Bottling Co. v. N.L.R.B.,

38 L. Ed. 2d 388 (1973), aff’g 467 F.2d 164, 166 (9th Cir.

1972). Thus, reinstatement to the full status that would

have obtained absent discrimination, including full senior

ity, is appropriate and necessary relief for an employee

discharged for protected union activities. Phelps Dodge

Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 313 U.S. 177, 188 (1941), Southport Co.

v. N.L.R.B., 315 U.S. 100, 106 n.4 (1942); and for an eco

nomic striker illegally denied rehiring, N.L.R.B. v. Mackay

Radio & Telegraph Co., 304 U.S. 333, 341, 348 (1938);

N.L.R.B. v. Transport Co. of Texas, 438 F.2d 258, 264-266

(5th Cir. 1971).

Unlawfully rejected applicants for employment are en

titled to no lesser remedy than dischargees and strikers.

This Court has held:

Experience having demonstrated that discrimination

in hiring is twin to discrimination in firing, it would

indeed be surprising if Congress gave a remedy for

the one which it denied for the other. . . . To differen

tiate between discrimination in denying employment

and in terminating it, would be a differentiation not

only without substance but in defiance of that against

which the prohibition of discrimination is directed.

22 United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906, 92.1 n.19

(5tli Cir. 1973) ; Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494

F.2d 211, 252 (5th Cir. 1974).

17

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. N.L.R.B., supra, 313 U.S. at 188. Vic

tims of unlawful hiring discrimination should therefore be

reinstated on the same basis as those unlawfully discharged.

See, e.g., Atlantic Maintenance Co. v. N.L.R.B., 305 F.2d

604 (3rd Cir. 1962), enfg 134 NLRB 1328 (1961) (requir

ing reinstatement of rejected applicant with full seniority

status); N.L.R.B. v. Lamar Creamery Co., 246 F.2d 3, 10

(5th Cir. 1957), enfg 115 NLKB 1113 (1956) (rejected ap

plicant ordered reinstated “without prejudice to senior

ity”) ; N.L.R.B. v. Cone Brothers Contracting Co., 317 F.2d

3, 7 (5th Cir. 1963).

The Fifth Circuit’s decision under Title VII specifically

prohibits the relief this Court deems vital under the NLRA.

Under the doctrine announced below, a victim of racially

motivated refusal to hire may not be reinstated to the posi

tion he would have held in the absence of discrimination.

The district court could only order him reinstated to an

inferior position of lower seniority standing. And discrim

ination in hiring would give rise to a lesser remedy than

its “twin” discrimination in firing, when the discrimination

is motivated by race or sex rather than union activities.

The decision below carves out a special category of un

lawful labor practices for persons illegally denied hiring

because of race or sex and denies them a remedy available

to all other victims of such practices.

C. Public policy sometimes requires individuals in pro

tected categories to be given employment credit for time

not actually worked on a job. Thus, Congress has enacted

legislation that grants seniority or length-of-service credit

to persons who were not employed but were engaged in

military service. The Selective Training and Service Act

of 1940, 50 U.S.C. App. §§ 301 et seq., and the Selective

Service Act of 1948, 50 U.S.C. App. §§ 451 et seq., both

required that an enrployee returning to a prior employer

18

from satisfactory military service be restored to bis job

“without loss of seniority,” 50 U.S.C. App. § 459(c) (1967).

See also, 5 U.S.C. § 3502(a) (1966) (federal employee

competing for retention in reduction-in-force receives

credit for time in military service).

In Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, 345 TJ.S. 330 (1953),

this Court held that the same policies expressed in the

Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 authorized,

as consistent with the National Labor Relations Act, the

granting of seniority credit for military service before

initial employment. Huffman rejected a challenge to a

collective bargaining agreement provision that gave veter

ans seniority credit for service during World War II

whether or not they were Ford employees before enter

ing the service, 345 U.S. at 334-335 nn.6,7, id. at 339-340.23

The Court, while relying on the strong public policy favor

ing employment of returning veterans, indicated that simi

lar provisions would be appropriate for other national

policy or public interest reasons, id. at 338-339. It spe

cifically held that the NLRA does not require seniority

to be based exclusively on dates of actual employment,

holding,

Nothing in the National Labor Relations Act, as

amended, so limits the vision and action of a bar

gaining representative that it must disregard public

policy and national security. Nor does anything in

that Act compel a bargaining representative to limit

seniority clauses solely to the relative lengths of em

ployment of the respective employees.

Id. at 342. Accord: Aeronautical Industrial District Lodge

727 v. Campbell, 337 U.S. 521 (1949) (Selective Service

23 The Court noted that such seniority provisions were then

“widespread,” id. at 333.

19

and Training Act does not require that NLRA be con

strued to require date-of-employment as standard for

seniority).24

The decision in the instant case would bar the district

courts under Title VII from granting, as a remedy for

discrimination, a measure that the NLRA. clearly author

izes for bargaining representatives. Such a narrow view

of Title VII is incompatible with the strong public policy

—no less strong than that of assisting returning veter

ans—favoring effective relief to victims of employment

discrimination.

III.

Neither the Statutory Language Nor the Legislative

History Supports the Result Reached by the Court o f

Appeals.

The text of Section 703(h) does not clearly indicate any

Congressional purpose to delimit remedies available un

der Section 706(g). Section 703(h) does not authorize or

limit Title VII relief at all; it simply clarifies the pro

hibition of Section 703(a) against unlawful employer

practices, by authorizing use of a “bona fide seniority or

merit system.” The statute does not define a “bona fide

seniority system.” In Phelps Dodge Corp. v. N.L.B.B.,

supra, this Court noted, “unlike mathematical symbols,

the phrasing of such social legislation as this seldom at

tains more than approximate precision of definition,” and

therefore sought guidance in the broad legislative policy

of the NLRA, 313 U.S. at 185. See also, Golden State

Bottling Co. v. N.L.R.B., supra, 38 L.Ed.2d at 398. A

24 As the Court noted there, to imply “that date of employment

is the inflexible basis for determining seniority rights as reflected

in layoffs is to ignore a vast body of long-established controlling

practices in the process of collective bargaining. . . . ” Id. at 527.

20

similar approach here militates against a restrictive read

ing of the vague provisions of Sections 703(h).

Every decision that construed Section 703(h) prior to

the Court of Appeals decision herein had read the section’s

terms narrowly.25 26 In the leading cases of Quarles v. Philip

Morris, Inc., supra, 279 F. Supp. at 516-517, and Local 189,

United Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United States,

supra, 416 F.2d at 995-996, the courts reasoned that a

seniority system which carries forward the effects of past

discrimination is by definition not “bona fide”. Both courts

noted that the Section 703(h) exemption is expressly in

applicable to seniority systems which cause differences re

sulting from “an intention to discriminate because of race,”

and that prior hiring discrimination is such an “inten

tional” act, see Quarles, 279 F. Supp. at 519; Local 189,

416 F.2d at 996.26

The legislative history reveals no Congressional inten

tion that Section 703(h) should limit the scope of Section

706(g). Congress attached no such limitations when it

adopted the remedial provisions of Section 706(g).27 Arid

all indicia of purpose show that Congress intended no ad

ditional restrictions when it added Section 703(h) to Title

VII as a late amendment. For a full discussion, see

25 Subsequently, the United States Court of Appeals for the

Seventh Circuit, in Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of Interna

tional Harvester Co., 503 F.2d 1309 (August 26, 1974), reached

the same legal conclusion as the Fifth Circuit. Waters is, however,

distinguishable. It involves the layoff/recall rights of an employee

whose application was discriminatorily rejected before Title VII

became effective.

26 Accord: United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., supra, 446

F.2d at 661-662; United States v. Chesapeake & Ohio Bwy. Co.,

supra, 471 F.2d at 587-588; United States v. Sheet Metal Work

ers, Local 36, supra, 416 F.2d at 133-134 and n. 20.

27 On the contrary, Congress has expressed its understanding

that Section 706(g) authorized broad remedies, see p. 10, supra.

21

Cooper and Sobol, supra, at 1610-1614. There was no

Congressional discussion, after the introduction of the

amendment, of what constitutes a “bona fide seniority sys

tem,” id. at 1610-1611, 1613.28

The limitation imposed by the Court of Appeals is there

fore judge-made. The Court of Appeals erroneously en

grafted a limitation on Section 706(g) from an unrelated

provision. The Court of Appeals’ construction of Section

703(h) as a limiting remedial provision is particularly in

appropriate since it would undo much of what Congress

hoped to accomplish in providing for broad and flexible

remedies. See Cooper and Sobol, supra, at 1614.

IV.

The Court o f Appeals D ecision Conflicts With Au

thorities Holding That Title VII Does Not Limit Rem

edies Available Under 42 U.S.C. §1981 .

The Court of Appeals ignored Petitioners’ cause of

action under the Civil Eights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

The Court correctly assumed that Petitioners were en

titled to relief on that separate basis (A 9, A 39),29 but

28 Petitioners suggest that a “bona fide seniority system” within

the correct meaning of the Act would be one which measures not

mere longevity but rather skill or ability necessary to efficient job

performance. This reading of the section is supported by its

reference to “merit” and “quantity or quality of production”.

Cf. Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971). The decision

below forecloses seniority relief to rejected applicants without

regard to whether, in a particular case, seniority might be related

to job performance.

29 Although this Court has not yet specifically ruled on the ques

tion (but see, Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., O.T.

1974, No. 73-1543), Section 1981 is now universally accepted as

an independent basis for employment discrimination actions. See,

e.g., Macklin v. Spector Motor Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d

979, 993-994 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ; Guerra v. Manchester Terminal

Co., 498 F.2d 641, 654 (5th Cir. 1974) ; and cases cited therein.

22

did not draw the logical consequences. Section 703(h)

cannot limit remedies based on laws other than Title VII,

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Secre

tary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159, 172 (3rd Cir. 1971), cert,

denied 404 U.S. 854 (1971). The same reasons for reject

ing Section 703(h) as a limitation on Title VII relief

apply even more forcefully to the Section 1981 remedy;

the latter section is a separate statute enacted a century

earlier. Cf. Watkins v. United Steel Workers, Local No.

2369, supra, 369 F. Supp. at 1230-1231.

This Court has stated that in adopting Title VII, Con

gress did not intend to limit the scope or effectiveness of

pre-existing remedies for employment discrimination, in

cluding Section 1981, Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

39 L.Ed.2d 147, 158 (1974). While considering the 1972

Amendments to Title VII, the Senate twice rejected an

amendment that would have made Title VII the exclusive

remedy for employment discrimination, Cong. Rec. S.

1526 (daily ed. February 9, 1972), Cong. Rec. S. 1797

(daily ed. February 15, 1972). The Report of the Senate

Committee on the amendments specifies that none “of the

provisions of this bill are meant to affect existing rights

granted under other laws,” S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Congress,

1st Session (1971), p. 24. This Court has reached a simi

lar conclusion as to the effect of the Fair Housing Act of

1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq., on the sister statute of

Section 1981. In Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 417

n. 20 (1968), it held that that Act “does not mention 42

U.S.C. § 1982, and we cannot assume that Congress in

tended to effect any change, either substantive or pro

cedural, in the prior statute. See United States v. Borden

Co., 308 U.S. 188, 198-199 [1939].” By the same logic,

Section 703(h) cannot bar Petitioners from full seniority

relief based on Section 1981.

23

CONCLUSION

The Court should grant a Writ of Certiorari to review

the judgment and opinion of the Court of Appeals.

Respectfully submitted,

J o h n R . M y ee

Crosland, Myer, Rindskopf & Terry

2415 Nat’l Bank of Georgia Bldg.

34 Peachtree Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

J ack Gbeen bebg

J am es M. N a bbit , III

M o eeis J . B alleb

B abby L. G oldstein

10 Columbus Circle—Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

E l iz a b e t h R . R in d sk o pf

265 Church Street

New Haven, Connecticut 06510

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

A1

D ecision o f the United States Court o f Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

FRANKS v. BOWMAN TRANSP. CO.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the North

ern District of Georgia.

Before THORNBERRY, AINSWORTH and RONEY, Cir

cuit Judges.

THORNBERRY, Circuit Judge:

After processing a complaint through the EEOC, appellant

Franks brought this racial-discrimination civil rights suit un

der Title VII, § 706, of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C.A. § 2000e-5, and under 42 U.S.C.A. § 1981 on behalf of

himself and those similarly situated against his former em

ployer, Bowman Transportation Company, and his union.1 He

alleged a discriminatory refusal to promote and a discrimina

tory discharge, and he sought extensive declaratory and equi

table relief for himself and for class members. Lee was

permitted to intervene as plaintiff to press his individual

claim against Bowman for a discriminatory refusal to hire and

for a discriminatory discharge and to represent other classes

of black Bowman employees and job applicants. The district

court found after a three-day trial that Franks had estab

lished the factual bases for his individual claim, but it dis

missed his individual action because it concluded Franks had

waited beyond the applicable limitations period to file suit.

The court held that Lee factually established his claim for a

discriminatory refusal to hire, but failed to prove his claim for

discriminatory discharge, and it accordingly entered judgment

partly for him and partly against him. As to the classes

represented, the court found that past racial discrimination

had been demonstrated and that the departmental seniority

1. International Union of District 50, Local No. 13600, Allied and

Technical Workers of the United States and Canada. Also included

as a party defendant was the national union of which Local 13600 is

a part, International Union of Allied and Technical Workers of the

United States and Canada.

A2

system maintained by Bowman and the union perpetuated the

effects of past discrimination. As a remedy, the court en

joined Bowman from discriminating along racial lines in the

future, ordered that certain class members be allowed to

utilize company seniority accumulated before the date on

which discrimination had ceased, and afforded certain discri-

minatees who responded to a notice from Bowman within

thirty days priority in consideration for employment. The

court declined to grant further affirmative relief requested,

including the use of full company seniority for certain discri-

minatees, measures to ensure hiring and training of greater

numbers of blacks in the future, and a requirement that

Bowman file periodic reports with the district court to demon

strate compliance.

On this appeal we are asked to review the district court’s

adverse rulings on the individual claims of Franks and Lee

and to determine whether the district court abused its discre

tion in not affording greater affirmative relief to the classes

they represented. We shall discuss the pertinent facts in

connection with the various claims.

I. Franks’ Individual Claim: Limitations and Laches

Bowman is an interstate trucking company which operates

as a common carrier licensed by the Interstate Commerce

Commission throughout southeastern United States and in

parts of the mid-west.I. 2 Its principal terminals are in Atlanta,

Birmingham, Charlotte, and Richmond.

Franks, a Negro, was first hired at Bowman’s Atlanta

terminal in 1960 as a “tire man,”—a position which requires

the most menial work at the terminal and brings the lowest

pay. Except for a one-year period in 1961 and 1962 during

which he was assigned as a “grease man,” Franks worked as a

tire man continuously until 1965, when he resigned due to an

2. Bowman’s operations and procedures are described more fully at

the beginning of part III of this opinion, infra.

FRANKS v. BOWMAN TRANSP. CO.

A3

injury. In 1966 he was rehired as a tire man. After his

return Franks attempted on several occasions to obtain a

transfer, or promotion, into another job, but his way was

blocked by Bowman’s racially discriminatory policy of employ

ing blacks only in the Tire Shop.3 Although Bowman agreed

in a collective bargaining agreement signed in 1967 to allow

transfers and to hire without regard to race, the discriminato

ry policy was in fact continued in effect unofficially after

1967. Both before and after 1967 Franks was told that blacks

could not transfer, or be promoted, from the Tire Shop. The

district court found that but for Bowman’s discriminatory

policy, Franks should reasonably have been promoted to a

higher paying, “dock worker” position by the end of 1967. No

challenge is made to this finding.

Having watched white workers hired “off the street” into

higher paying positions for which he was qualified and had

applied, Franks filed a complaint with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission on March 25, 1968, charging that

Bowman refused to promote him because of its racially dis

criminatory policy of employing blacks only in the Tire Shop.

EEOC officials visited the Atlanta terminal on two occasions,

on April 23, 1968 and on May 10, 1968 to investigate Franks’

charges. A few hours after the second visit Bowman dis

charged Franks, assertedly for “unauthorized bobtailing,” or

using company vehicles for personal errands. The district

court rejected this purported explanation, however, and found

that Franks was discharged “for reasons of race.” On May

13, 1968 Franks filed a second complaint with the EEOC,

alleging a discriminatory discharge.

Efforts to resolve the dispute through conciliation having

failed, on March 21, 1969 Franks’ then attorney requested the

EEOC to issue a § 706(e) “suit letter” covering both com

plaints, and such a letter was sent on the same day to Franks’

mailing address by certified mail, return receipt requested.

3. Two blacks who worked as “cleanup men” in the Trailer Shop

were exceptions.

FRANKS v. BOWMAN TRANSP. CO.

A4

Franks resided at 5339 Victory Drive in Morrow, Georgia, but

he received his mail at 5319 Victory Drive, where his grand

mother, sister, and nine-year-old nephew resided. On March

22 his nephew received the letter and signed the postal

receipt, but he lost the letter before delivering it to Franks.

Franks learned that his nephew had signed for some letter,

but he never saw or received the letter personally. About a

year later, on March 20, 1970 Franks contacted EEOC officials

again about his dispute with Bowman, and, upon being shown

the postal receipt for the first suit letter, affirmed in an

affidavit that he had not personally received it. Franks then

retained his present attorneys and filed “amended” charges

with the EEOC which substantially duplicated the earlier

charges. A second suit letter issued on April 14, 1971, and

Franks filed a suit less than a month later on May 5, 1971.

On these facts the district court held Franks’ Title VII and

his Section 1981 claim barred. As to the Title VII action, the

court reasoned that the thirty-day statutory limitations

period 4 began to run on March 22, 1969, the date the first suit

letter was delivered to Franks’ mailing address, so that the

action was barred after April 21, 1969. As to the § 1981

action, the court concluded that a two-year Georgia statute of

limitations was applicable and that it barred the claim since

the suit had not been filed for almost three years after

Franks’ discharge on May 10, 1968.

[1] The statutory language which established the thirty-

day limitations period applicable to Franks’ Title VII action is

found in § 706(e) as it read before the 1972 amendments:5

If within thirty days after a charge is filed with the

Commission [or within sixty days, if the Commission acts to

extend the period] the Commission has been unable to

obtain voluntary compliance with this subchapter, the Com-

4. The 1972 amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, P.L. 92-261

§ 14, 86 Stat. 113, extended the limitations period from thirty days

to ninety days.

5. See note 4 supra.

FRANKS v. BOWMAN TRANSP. CO.

A5

mission shall so notify the person aggrieved and a civil

action may, within thirty days thereafter be brought

against the respondent named in the charge (1) by the

person claiming to be aggrieved.

The key word in the statute is “notify”; the limitations period

begins to run upon notification of the aggrieved party.6 This

Court has held that such notification takes place only when

“notice of the failure to obtain voluntary compliance has been

sent and received.” Miller v. International Paper Co., 5th Cir.

1969, 408 F.2d 283 (emphasis added). There being no question

that the EEOC mailed the statutory notice to Franks, the

Title VII limitations issue must be framed in terms of wheth

er Franks constructively “received” the letter, even though it

never actually came into his hands. We hold that Franks did

not “receive” the first suit letter, and that the thirty-day

limitations period began to run only when the second suit

letter actually reached him or his attorney. Genovese v. Shell

Oil Co., 5th Cir. 1973, 488 F.2d 84. Since suit was filed within

thirty days of the receipt of the second suit letter, the Title

VII action was not barred by the § 706(e) limitations period.

We do not deal here with service of process or receipt of an

offer or acceptance to make a contract, but with the interpre

tation of Title VII. The courts have consistently construed

the Act liberally to effectuate its remedial purpose, and we

think this purpose would be poorly served by the application

of a “constructive receipt” doctrine to the notification proce

dure. More narrowly, the purpose of the statutory notifica

tion, which is “to provide a formal notification to the claimant

that his administrative remedies with the Commission have

6. The statute does not establish an aggregate ninety-day limitations

period (i. e., the aggregate of the maximum sixty-day conciliation

period and the thirty-day right-to-sue period) which begins to run on

the date the charge is filed. Miller v. International Paper Co., 5th

Cir. 1969, 408 F.2d 283. The statute does not specify any certain

limit on the time which may pass between the expiration of the

conciliation period and the statutory notification, which starts the

thirty-day period. See id.; see also 29 C.F.R. § 1601.25a.

FRANKS v. BOWMAN TRANSP. CO.

A6

been exhausted,” Beverly v. Lone Star Lead Construction

Corp., 5th Cir. 1971, 437 F.2d 1136, and to inform him that the

thirty-day period has begun to run, has not been accomplished

unless the claimant is actually aware of the suit letter. In

terms of the policy behind limitations periods generally, the

claimant can hardly be said to have slept on his rights if he

allows the thirty-day period to expire in ignorance of his right

to sue.

Our holding that the statutory notification is complete only

upon actual receipt of the suit letter accords with the view we

have expressed in prior cases that Congress did not intend to

condition a claimant’s right to sue under Title VII on fortui

tous circumstances or events beyond his control which are not

spelled out in the statute. Thus, in Beverly v. Lone Star Lead

Construction Corp., supra, we concluded that the EEOC’s

failure to find reasonable cause to suspect a Title VII viola

tion was not a jurisdictional barrier to a claimant’s Title VII

suit because Congress did not intend to make a claimant’s

statutory right to sue subject to “such fortuitous variables as

workload, mistakes, or possible lack of diligence of EEOC

personnel.” Id. at 1140. Similarly, in Dent v. St. Louis-San

Francisco Railway Co., 5th Cir. 1969, 406 F.2d 399, we held

that the EEOC’s failure to attempt to effect voluntary concili

ation did not bar a Title VII suit because a claimant’s right to

sue was not dependent on acts or omissions of the EEOC

which were “beyond the control of the aggrieved party.” Id.

at 403. In this case we are not confronted with any delay or

mistake on the part of the EEOC, but with the loss of the first

suit letter by Franks’ nine-year-old nephew. This loss must

be characterized as a fortuitous event, however, just as loss of

the letter in the EEOC office before mailing or loss by the

postal department would have been.

[2] As an evidentiary matter, a district court might prop

erly consider the mailing of a suit letter and the receipt

showing proper delivery as prima facie evidence that the

notice had reached the addressee. Where, however, it is

FRANKS v. BOWMAN TRANSP. CO.

A?

shown that the claimant through no fault of his own has

failed to receive the suit letter, and the district court has so

found, as in this case, the delivery of the letter to the mailing

address cannot be considered to constitute statutory notifica

tion.

[3] Our conclusion that Franks’ Title VII is not barred

does not end the matter, for special limitations considerations

apply to that aspect of the Title VII action which seeks back

pay. First, the proper limitations statute must be selected

and applied. Under the borrowing principle of Beard v.

Stephens, 5th Cir. 1967, 372 F.2d 685, when an action is

brought for back pay or similar damages under a federal

statute which contains no built-in limitations period, the fed

eral district court must apply the statute of limitations of the

state where it sits which would be applicable to the most

closely analogous state action. The instant case was brought

in a Georgia federal court. We have held in a recent case that

the Georgia statute governing a back pay award in a § 707

pattern or practice suit brought by the Attorney General or in

a § 706 private action such as the instant one, is Ga.Code

§ 3-704,7 which prescribes a two-year limitations period for

actions to recover wages, overtime, and damages due under

statutes respecting the payment of wages. United States v.

Georgia Power Company, 5th Cir. 1973, 474 F.2d 906, 924.

Under the Georgia Power case, then, it is clear that the

two-year statute applies.

[4] For Franks’ individual claim the statute began running

on the date of his dismissal May 10, 1968. The running of the

limitations period was tolled by the filing of a complaint with

7. Section 3-704 reads in pertinent part:

All suits for the enforcement of rights accruing to individuals

under statutes, acts of incorporation, or by operation of law, shall

be brought within 20 years after the right of action shall have

accrued: Provided, however, that all suits . . . for the

recovery of wages and overtime, subsequent to March

20, 1943, shall be brought within two years after the right of

action shall have accrued.

FRANKS v. BOWMAN TRANSP. CO.

a 8

the EEOC on May 13, 1968, three days later, and it remained

tolled “during such time as the processes of agency reconcilia

tion are at work and until notification to the complainant that

voluntary compliance cannot be obtained.” United States v.

Georgia Power Co., supra at 925. As we have indicated above,

the notification was not ultimately made until the second suit

letter was received on April 14, 1971. On this date the

limitations period began running again and continued to run

for twenty-one days, until suit was filed on May 5, 1971.

Thus the limitations period ran for a total of less than one

month, far less than the two year limitations period, before

the suit was filed.

Under the same borrowing principle of Beard v. Stephens,

supra, we conclude that Ga.Code § 3-704 applies to Franks’

action under § 1981, The first sentence of that section

providing a twenty-year period for “all suits for the enforce

ment of rights accruing to individuals under statutes

. ”, plainly did not bar Franks’ § 1981 action. The

proviso of the § 3-704 prescribing a two-year period for suits

to recover wages applies to the § 1981 action in the same way

as to the Title VII action. The running of the limitations

period was tolled during the period between the filing of the

May 13, 1968 complaint with the EEOC and the receipt of the

second suit letter on about April 14, 1971.

[5] One further matter relating to the time suit was filed

remains to be considered, and that is the applicability of the

doctrine of laches. Title VII empowers the federal district

court to

enjoin the respondent from engaging in such unlawful

employment practice, and order such affirmative action as

may be appropriate, which may include . . . rein

statement or hiring of employees, with or without back pay.

§ 706(g), 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e-5(g). Thus, the action and the

relief authorized are essentially equitable in nature. This is

FRANKS v. BOWMAN TRANSP. CO.

true not only of traditional injunctive relief which may be

granted, but also of the back pay award.

The demand for back pay is not in the nature of a claim for

damages, but rather is an integral part of the statutory

equitable remedy, to be determined through the exercise of

the court’s discretion, and not by a jury.

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 5th Cir. 1969, 417

F.2d 1122. The § 1981 action, insofar as it corresponds to the

Title VII action, must also be considered essentially equitable.

In an equitable action, equitable defenses may be raised, and

these include the doctrine of laches. In the proper case, laches

might be applied to bar a claim entirely, or it might bar only

part of the remedy sought, such as the back pay award or a

portion of it. See United States v. Georgia Power Co., supra

at 923. We do not intimate any view as to the applicability of

laches to this case, for the district court should make such a

determination in the first instance.

[6] Our holding that Franks’ individual claim was not

barred by limitations necessitates reversal of that portion of

the district court’s judgment dismissing it. Since the question

of Franks’ tardiness in initiating suit was called to the atten

tion of the district court, on remand it should specifically

consider the applicability of laches.8 Subject to its determina

tion as to the applicability of the doctrine of laches, the

district court should enter judgment for Franks and fashion

an appropriate remedy, since it has already found that he

established the factual bases of his claim.

II. Lee’s Individual Claim: Significance of

Arbitration Award

Lee, a Negro with seven years’ experience as a truck driver

and an excellent driving record, originally applied to Bowman

8. Appellants contend that the issue was not adequately raised

below. When the issue of tardy filing was brought sufficiently to

the attention of the court to be the ground for its ruling, however,

we think it must be considered to have been adequately raised.

A9

FRANKS v. BOWMAN TRANSP. CO.

A10

for a driving job in January of 1970, but he was not hired, the

district court found, because of his race. Upon learning that a

white driver had been hired shortly after his rejection, Lee

filed a complaint with the EEOC on February 26, 1970,

charging a racially discriminatory refusal to hire. In response

to the charge and to pressure from the Office of Federal

Contract Compliance, Lee was hired on September 18, 1970 at

the Birmingham terminal as one of Bowman’s first black

over-the-road truck drivers.

After working as a model employee for several months, Lee

was discharged on March 18, 1971. The facts surrounding his

discharge have been in dispute throughout this litigation.

When Lee brought his truck to the Bowman garage which