Plaintiffs' Mission Statement Summary

Working File

October 1, 1990

7 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Mission Statement Summary, 1990. d1ea85d2-a346-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b07c46b0-a31b-46e5-85be-4eb57994023d/plaintiffs-mission-statement-summary. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

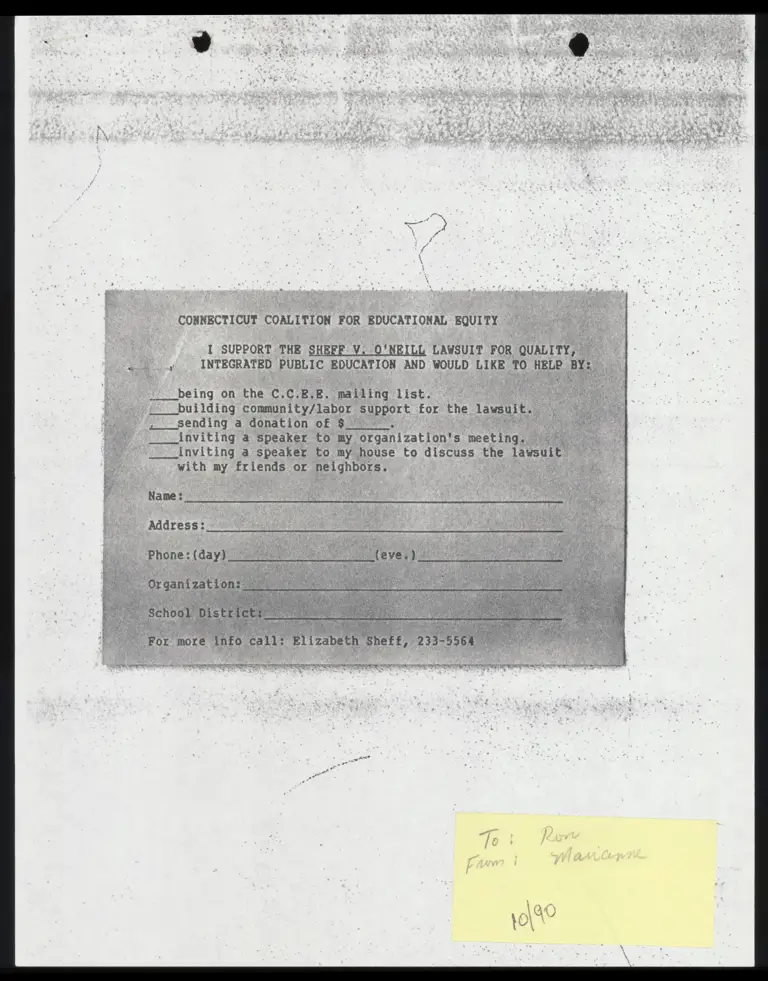

CONNECTICUT COALITION FOR EDUCATIONAL EQUITY

I SUPPORT THE SHEFF V. O'NEILL LAWSUIT FOR QUALITY,

CT INTEGRATED PUBLIC EDUCATION AND WOULD LIKE TO HELD BY

being on the C.C. E. E. mailing list. :

building community/labor support for the lawsuit.

sending a donation of § . 3

inviting a speaker to my organization's meeting, it

‘inviting a speaker to my house to discuss the lawsuit

with my friends or neighbors.

Name:

Address:

Phone: (day)

| organization:

4 4

August, 1989

SHEFF v. O'NEILL PLAINTIFFS' MISSION STATEMENT: Summary

We are ten families who desire the best possible education for our children and for all children in Greater Hartford. We are also dedicated to working for social justice and harmony. We want our children to be prepared for productive, self-sufficient adult careers; we want them to be able to associate with, learn from, and learn how to live together with people of backgrounds different from their own; and we want them to live in a just society. We believe that integrated education is essential to quality education. We believe that providing quality integrated education to all children is essential to securing ,an equitable and prosperous future for all the citizens of Greater Hartford. For these reasons we are asking the courts to protect our children’s rights, guaranteed them by the Connecticut Constitution, to enjoy equal educational opportunities and to obtain adequate educations.

The pattern of racial and ethnic segregation in the schools of Greater Hartford is obvious, flagrant, and getting worse. Well over 90% of the schoolchildren of Hartford belong to minority groups. Well over 90% of the schoolchildren in suburban towns that surround Hartford are white. Public officials have been aware of this pattern of segregation problem at least since the mid-1960s, but have failed to correct it. We think it is not only educationally unsound and morally wrong, but it also violates the first article of the Connecticut Constitution, which guarantees an equal opportunity to obtain a good education to every child in the state. In education, separate is unequal.

The Hartford schools enroll far more students from poor families, single-parent families, and families with limited English proficiency than do suburban schools. Even with their best efforts, the Hartford schools cannot meet all the special needs of their students. The tragic result is that on average Hartford schoolchildren learn less than suburban schoolchildren. Tests administered by the Connecticut Department of Education to measure essential reading and mathematics abilities show that a majority of Hartford students have not mastered "essential grade- level skills”. Thus by the State's own educational standards, these students are not receiving an adequate education. We believe this pattern of low academic achievement stems from violations of students’ right to equal educational opportunity. All children deserve an equal opportunity to learn and prepare themselves for productive adult lives.

The segregation of schools in Greater Hartford hurts not Just the poor and minority children of Hartford but also the

predominantly white school populations in suburban towns. For all children, segregated education is inferior education, because deprives them of the Opportunity to associate with and learn from children representing different racial, ethnic, and economic backgrounds. Only in integrated classrooms can children learn living lessons about the perceptions and values and human worth of people different from themselves. In a democratic nation that is profoundly multiracial and multicultural, segregated education is inefficient and imprudent as well as wrong. The ethnic homogeneity and insularity of many suburban schools weaken them as educational environments. Desegregation will strengthen them.

We have decided to bring suit in Superior Court, 1) because we are convinced that the defendants in the case, the authorities responsible for public education in Connecticut, have long been aware of the segregation problem but have failed to act to solve it, and 2) because the historical record shows that purely voluntary desegregation plans do not achieve significant results. We see no contradiction between our lawsuit and voluntary initiatives to desegregate the schools. We support such initiatives and we intend to take part in them in our communities. But we are convinced that voluntary measures alone will not suffice. Only when the courts have become involved, only when constitutional rights have been asserted and defended, has there been meaningful progress toward righting the wrongs of segregation.

THE PLAINTIFFS

For more information, please contact The Connecticut Ccalition for Educational Equity, 32 Grand Street, Hartford, CT 06106

Iv]

< >

CONNECTICUT SCHOOL DISTRICTS WITH FIFTEEN PERCENT

OR MORE MINORITY ENROLLMENTS

: SALTSOURY ORTH CANAAN wonrern | COLEBROON | mAmTLAMS wie mel Stafrony weon | wesesiocs es,

a] CRAY

BARKIANS TED tas)

N

R

D

o

s

s

y

G

T

I

O

P

3

EX

A

V

A

Y

QT

)

0

CTY craney Jomo ton RLMC TON PUTIRAR

LOCKS EASY TOLLAND baad ros Y

. My 9tmn ING WD SOR (AsITOne

en arr RD & re hind | WRLINGLY

tonag Ton " weoson | VERON o |

Tovar | mAWSIELD "| | a TON

| Ti] MANCHEST es reaR-NL@

ARTY MY | waa tnewme pt CA ARNE " sessed al]

: To CANTERBURY

WETMRSTLD om ad]

— CLAS TRHBRY HEmOR Sram

WALT ocxY mit Lenamen

TRE S EA trea thaw d Tee

gy So NS

po Ee — ts? CRCNESTER tress

a a bupg

of paTmAn loll ll

Fman WA EASY SMEm COI) raEsIoN ron A 2

wer — it : wowTeLe 7

FARTELD WTIRY trovane

wallmGrenn | BURMAN Ey -

’ ¥

"wow ihe fas Wann RS vor 10] Lvsg WATER ONS STengTon

srTHANY J:

: Se maven | moar we) | mw Low pig

CL 1 Ce ha wed maven

Bn AN . FS8Ex EAST LY

ONE 4 Si "sr 0p [AY LYE

ony pulagen. Mw "A a sro YoROm

aatd 3 wis! aan

EASTON \ onan} al navn

wes pw

re i p- Minority Enroliment

: NS Yip 50-74% 25-49% 15-24%

a

b

PD

o

r

y

o

y

a

f

a

a

b

*

S

2

(

Q

Soovce! Connecdico tb Educ a Non Assoc taNen Desecre 5 RN Tes kforce

A Desegregation Chronology

Desegregation of schools has been discussed in Connecticut for more than two decades.

A lawsuit filed in Hartford Superior Court on behalf of 17 children in Hartford and West

Hartford, claims that the Hartford students’ constitutional rights to equal opportunity and

freedom from discrimination were violated. The lawsuit, known as Sheff vs. O'Neill, also asks

for the court to order the racial integration of Hartford and suburban schools.

The following “Desegregation Chronology” is taken from the plaintiffs’ brief in that case.

1965—U.S. Civil Rights Commission issues a report documenting existence of racially

segregated schools in Connecticut.

The Hartford Board of Education and City Council hire Harvard University

consultants who find that low educational achievement in Hartford schools is closely

linked to a high level of poverty and that segregation causes educational damage to

minority children.

1966—The U.S. Civil Rights Commission asks the governor to seek legislation giving the state

Board of Education authority to integrate local schools. No such legislation has been

adopted.

1968 — Legislation is introduced to authorize the use of State bonds to pay for racially

integrated, city-suburban parks. The legislation was not enacted.

The State Board of Education proposes legislation that would authorize the board to

cut off money for school districts that fail to develop acceptable plans to correct racial

imbalance in local schools. The legislation was not enacted.

1969 — The Hartford school superintendent recommends that at least 5,000 children take part

in Project Concern, a voluntary transfer program allowing minority children from

Hartford to enroll in suburban schools. The program never exceeds 1,500 students and

now is about 750 students, less than 3 percent of the enrollment in Hartford Public

Schools.

The General Assembly passes a law requiring racial balance within, but not between,

school districts. However, the law is not put into effect for 10 years because the

legislature fails to approve regulations until 1980.

1986 —The State Board of Education adopts guidelines recognizing “the benefits of residential

and economic integration” in Connecticut.

A state board advisory committee issues a report saying there is a “strong inverse

relationship between racial imbalance and quality education in Connecticut's public

schools.”

1988 —Education Commissioner Gerald N. Tirozzi issues a report outlining the extent of racial

segregation in schools in Connecticut's largest cities. The report calls on largely white

suburbs to join cities in developing desegregation plans.

1989 —Tirozzi issues a second report, saying racial isolation in city schools is worsening. The

report recommends further study of various voluntary projects between cities and

suburbs.

14

# \

We would like to hear from you. Please jot down your thoughts on how you think we can

achieve quality- integrated education in the Greater Hartford area.

Under what conditions would you consider sending your child to a school in another

community? Please be specific about changes and improvements you would like to see.

PLEASE SEND YOUR COMMENTS TO C.C.E.E. 32 Grand Street. Hartford CT 06106