Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

September 21, 1998

68 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Jurisdictional Statement, 1998. fb7d6926-d90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b0a89a19-ee86-4eeb-8ed7-5a031bc2509b/jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

a

|

NN

(QV

{a )

i

FA

X

NO

.

20

26

82

13

12

[) |

OO

S JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT OO

(an)

=

~. @ARTIN B. McGEE ROBINSON O. EVERETT* Z Williams, Boger, Grady Everett & Everett = Davis & Tutlle, P.A. P.O. Box 586 P.O. Box 810 Durham, NC 27702

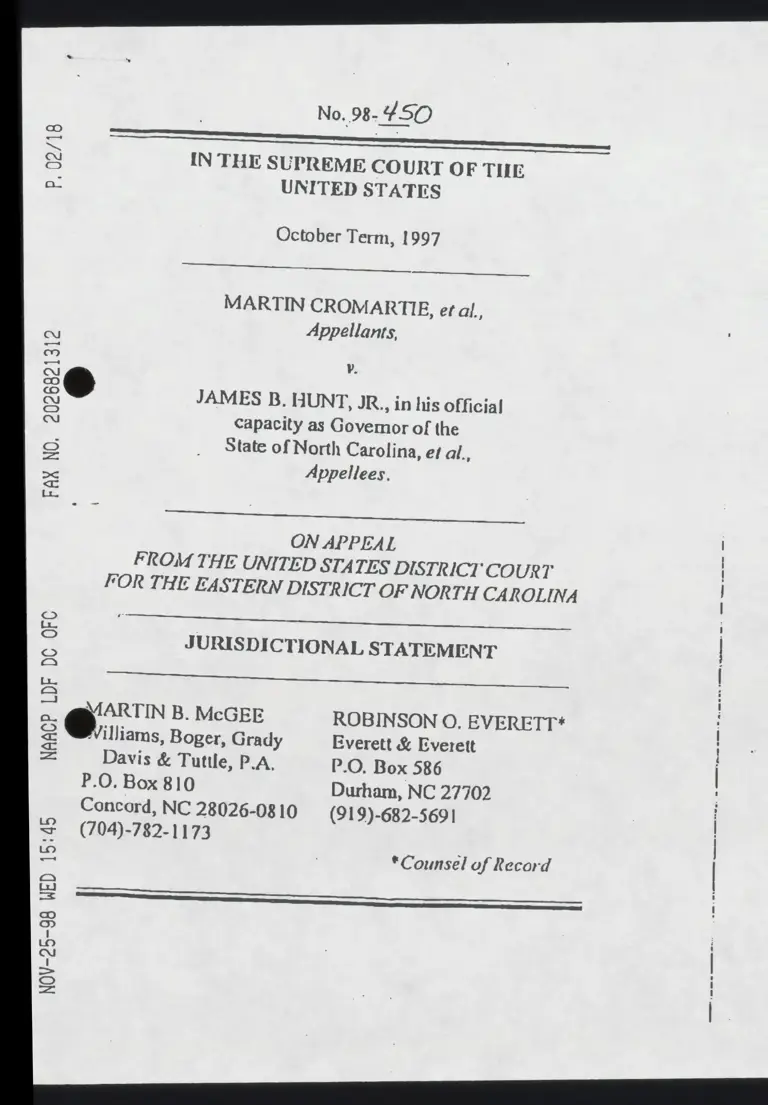

No. 98- 4.50

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TIE

UNITED STATES

October Term, 1997

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al,

Appellants,

py.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official

capacity as Govemor of the

State of North Carolina, et al.

Appellees.

ON APPEAL

FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Concord, NC 28026-0810 (919)-682-5691

(704)-782-1173

*Counsel of Record

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

5

i

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

After the 1992 and 1997 redistricting plans had been

held unconstitutional as racial gerrymanders and the

General Assembly had enacted a new plan, was the

district court required to determine that any

unconstitutional vestiges of tlie earlier plan had been

removed before allowing the 1998 plan to be used in

elections?

In determining whether the 1998 plan was an adequate

remedy for the unconstitutional defects of the 1992 and

1997 racial gerrymanders, should the three-judge

district court have placed on the State defendants the

burden of proving that race did not predominate as a

motive in drawing Districts 1 and 12?

P

A

G

F

AD

2

0

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

NO

U

25

’9

8

15

:5

4

ao

—t

NN

on

LN

o-

FA

X

NO.

20

26

82

13

12

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

Lo

<r

LO

-—4

[an]

Lx]

=

@

%

LO

T

=

Sr,

=z

i

LIST OF PARTIES

MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS CHANDLER MUSE,

R.O. EVERETT, JH. FROELICH, JAMES RONALD

LINVILLE, SUSAN HARDAWAY, ROBERT WEAVER and

JOEL K. BOURNE are appellanis in this case and were

plaintiffs below; :

JAMES B. HUNT, JR. in his official capacity as Governor of

the State of North Carolina, DENNIS WICKER in his official

capacity as Lieutenant Govemor of the State of North Carolina,

HAROLD BRUBAKER in his official capacity as Speaker of

the North Carolina House. of Representatives, ELAINE

MARSHALL in her official capacity as Secretary of the State

of North Carolina, and LARRY LEAKE, S. KATHERINE

BURNETTE, FAIGER BLACKWELL, DOROTHY

PRESSER and JUNE YOUNGBLQOOD in their capacity as the

North Carolina State Board of Elections, were defendants

below and are appellees in this case.

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, DAVID MOORE, WILLIAM M.

HODGES, ROBERT L. DAVIS, JR, JAN VALDER,

BARNEY OFFERMAN, VIRGINIA NEWELL, CHARLES

LAMBETH and GEORGE SIMKINS were allowed to

intervene of right as defendants at the time of the order

appealed from; and as defendant-intervenors they are included

as appellees.

Apart from lhe defendant-intervenors who are included as

appellees in this appeal, the parties in this case are the same as

in the separate appeal filed earlier in Hunt v. Cromartie, No.

98-85, in which the present appellants, Cromartie, ef al., who

were plaintiffs in the three-judge district court, were appellees

and the present appellees, Hunt, ef al,, who were defendants

below, were appellants.

TABLE OF CONTENTS ;

| bd QUESTIONS PRESENTED .............on.. Bee

LISTOFPARTIES fm 500 Tn 0 i

A IABLEOr AUTHORITIBS::..........00 0 iv ’

a

u OPINION BELOW. ....oh. cots. 3, 0 2 &

JURISDICTION .........eoniots le. 22 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED... 1... 4

STATEMENTOE THECASE oc... 05. 3

ARGUMENT. vi ifr, os iis 5

PYIROBUCTION ... 5. [0s 1.0 eg 5

I. THE COURT BELOW HAD THE DUTY To DETERMINE THAT NO “VESTIGES” OF THE EARLIER UNCONSTITUTIONAL PLANS REMAINED IN THE 1998 PLAN ...... 8

Il. THEDISTRICT COURT SHOULD HAVE PLACED ON THE STATE DEFENDANTS THE : BURDEN OF PROVING THAT THE 1998 PLAN hy WASNOTRACE-BASED,. 20", i

a

on CONCLUSION, 1.0 itn fon ai [7

&

2

Z

Iv

|

© TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ~~

= Brown v. Board of Educ., 892 F.2d 851 (10th Cir. 1989) .. 8

Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590 (1 015) ....... A. 9.17

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979) ... 8

Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200 0979). ..... 0 9.13 J

= ® » Cromartie, 8.C1. No. 98-85 ......... passim a

«©

SS. Hunierv Underwood, 471U.8. 222 (1985) ...... [1

= Miller v. Johnson, 515 US.000¢1998y. ,...0 12 o>

<TC

"Mt. Healthy City Sch. Dist. Bd. of Educ. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. SUIT) reer. a 1

Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338 (1939)... 9

re Ross v. Houston Ind Sch. Dist., 699 F.2d 218 (5th <5 Cn 1080 on i a 9 oo

= School Bd of the City of Richmond Vv. Baliles, 829 F.2d a 303 anmCienogy 0 TL 9, 16 <TC p=

: = Shaw v. Hunt, S17US, 39901996)... .%....... possin

Lo Snepp v. United States, 444 U.S. 507 (1930). .....» = 10 Tr

= Swann v. Charlotte-Meckienburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 3 O71)... a fa mE a 8 -_=

OQ

(>)

LO

(QV

=

2

Vv

Taylor v. Alabama, 457 U.S. 687 (1982)... ..... = ..¢9

Taylor v. Ouachita Parish Sch, Bd., 648 F.2d 959

QO), . oh io 9.17

United States v. Lawrence County Sch. Dist., 799 F.2d 103]

(3th Cir. 1986) ........ RP Se UE

Vaughan v. Board of Educ., 758 F.2d 983 (4th Cir.

Caste verb naeRe ti I Ls Te 16

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Dev. Corp.,

49U8.2500197%).. .p.... 911,16

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 2200976) ...... "7

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 US. 535(1918)........ 6.7, 10, 16

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 214293... 19" °

I

A

A

I

"

r

A

A

P

A

D

K

Q

A

D

I

T

1

D

NO

U

25

“vi

= CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS 5 rv

a US. Const, Amendinly. oui. id .F 2.3

BUSCEI23 oni inlb 7:3

USCS: ......00. 0. ...5 LR 13

NC.Con. Stal. § 163008). 22.0.0. Lob 1,2

1997 N.C. Sess. Laws, Oh M0. vii iin 0 4

1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, Ch. 2 ras rma igins doh, we 1,28

FA

X

NO.

“

®

"

"

®

LD

F

DC

OF

C

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

6

No. 98-450

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES

October Term, 1998

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.,

Appellants,

V.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official

capacity as Governor of the

State of North Carolina, ef al,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL

FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Martin Cromartie and the other Plaintiffs below appeal

from the Order of the Uniled States District Court for the

Eastern District of North Carolina, dated June 22, 1998, which

denied to appellants the temporary and permanent injunction

which they had sought to enjoin the State appellees from

conducting any elections under the congressional redistricting

plan enacted by the North Carolina General Assembly on May

21, 1998. See 1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, Ch. 2, amending N.C.

Gen. Stat. § 163-201 (a). Plaintiffs filed notice of appeal on July

P

O

R

E

A

P

A

P

R

R

P

1

1

2

ao

et

Ne

«©

8

0.

FA

X

NO.

20

26

82

13

12

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

6

2

17, 1998 and jurisdiction of this appeal is conferred on this Court by 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

OPINION BELOW

The June 22, 1998 opinion of the three-judge district court, which has not yet been reported, appears in the appendix

to this jurisdictional statement at | a.

JURISDICTION

The district court's order denying the injunction was entered on June 22, 1998. On July 17, 1998, appellants filed a notice of appeal to this Count. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This appzal concems the constitutionality of 1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, Ch. 2, which amended N.C. Gen. Stat. § 163- 201(a); copies of this Session Law were previously lodged with the Court by the present appellants in connection with the Motion to Dismiss or, in the Alternative, to Affirm which they filed in Hunt v. Cromartie (No. 98-85), where they are

appellees.

The present appeal involves the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment which provides:

All persons bom or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,

are citizens of the United States and of the State

wherein they reside. No State shall make or

enforce any law which shall abridge the

privileges or immunities of citizens of the

3

United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due

process of law; nor deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This appeal is taken pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1253

which provides: :

Except as otherwise provided by law, any party

may appeal to the Supreme Court from an order

granting or denying, after notice and hearing, an

interlocutory or permanent injunction in any

civil action, suit or proceeding required by any

Act of Congress to be heard and determined by

a district court of three judges.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE'

In Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) (“Shaw II), the

Court held thal District 12 in North Carolina’s 1992

congressional redistricting plan (“the 1992 plan”) violated the

Equal Protection Clause because race predominated in the

design of the Twelfth Congressional District, and the plan

could not survive strict scrutiny. The Court declined to

consider the constitutionality of the First District in the 1992

plan because none of the plaintiffs had standing. Therefore, a

separate action was initiated by Martin Cromartie and other

registered voters in the First District to challenge its

constitutionality.

' The present appellants have provided the Court a more detailed

statement of the relevant facts in their Counterstatement contained in the

Motion to Dismiss or, in the Alternative, to Affirm which they filed in Hunt

v. Cromartie (No. 98-85), which involves the same parties.

~

~

p

—

00

| 5

an

n

| a

d

oo

ton

le

e I

Re

e

p

I

s

s

n

25

NO

U

P.

07

/1

8

FA

X

NO.

l

g

“

®

LD

F

DC

OF

C

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

6

i.

The action filed by Cromartie was stayed by consent awaiting further proceedings in the Shaw litigation, which had been remanded to the lower court. That court granted the State legislature an opportunity to redraw the State’s congressional plan to correct its constitutional defects; and on Marc), 31 1997, the North Carolina General Assembly enacted a new congressional redistricting plan, 1997 Session Laws, Chapter [1 (“the 1997 plan”). The 1997 plan was precleared by the Department of Justice for use in the 1998 and subsequent elections; and in September 1997 it was accepted by the lower court as a remedy for the claim asserted by the Shaw plaintiffs, who under the 1997 plan were no longer residents of the Twelfth District.

Shortly thereafter, the stay in the action brought by Cromartie was dissolved; and an amended complaint was filed, which alleged that the 1997 redistricting plan was also an unconstitutional racial gerrymander and that race had predominated in drawing both its First District and its Twelfth District. The amended complaint included as plaintiffs registered voters both of the First and the Twelfth Disiricts.

After a hearing on March 31, 1998, the three-judge district court before which the casc was pending granted summary judgment for the plaintiffs as to the Twelfth Congressional District and enjoined the defendants from conducting any primary or general election under the 1997 redistricting plan. The state defendants gave notice of appeal and also applied unsuccessfully to the district court and to this Court for an Cmergency stay of the injunction. Subsequently, the State defendants filed a Jurisdictional Statement in this Count, Huni v. Cromartie (No. 98-85); and in response the

See Appendix la, 4a, 45a of the Jurisdictional Staternent filed in Hunt v. Cromartie (No. 98-85).

o

y

5

plaintiffs have filed a Motion to Dismiss or, in the Alternative,

to Affirm, which is now pending.

Instead of immediately undertaking to drafl its own

redistricting plan in order to remedy the constitutional defects,

the three-judge district court allowed the General Assembly an

opportunity to enact siill another redistricting plan. On May

21, 1998 a new plan (“the 1998 plan’) was enacted, which was

to be used for the 1998 and 2000 elections, unless this Court

reverses the district court decision holding the 1997 plan

unconstitutional. See 1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, Ch.2. Afier the

Department of Justice had precleared this plan, the plaintiffs

filed an opposition and objection to that plan; and the

defendants responded thereto.

On June 22, 1998, the three-judge district court

approved this plan "with respect to the 1998 congressional

elections,” because the court "concludes that on the record now

before us that race cannot be held to have been the predominant

factor in redrawing District 12.” (Appendix at 3a.) However,

the district court reserved “jurisdiction with regard to the

constitutionality of District I under this plan and as to District

12 should new evidence emerge,” and it directed that the case

“should therefore proceed with discovery and trial

accordingly." (App. at 5a.) The plaintiffs gave notice of

appeal with respect to this order.

ARGUMENT

Introduction

This appeal is taken to present for the Court’s decision

questions which concern the obligations of the three-judge

' Subsequently, a discovery schedule has been approved by the district

court.

p

p

po

go

lr

te

t

a

l

a

Po

TI

P

I

S

:

S

6

a

s

1

NO

U

25

a

-—

~N

a

i

a-

FA

X

NO.

20

26

82

13

12

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

7

6

district court in determining whether to accepl a new

redistricting plan as an adequate remedy for defects in two

earlier plans held to be unconstitutional racial gerrymanders,

The context for these questions is provided by the language of

the order entered below denying the requested injunction.

There the three-judge district court stated:

Because the Court cannol now say that race was

the predominant faclor in the drawing of

District 12 in the 1998 congressional districting

» plan, the revised plan is not in violation of the

United States Constitution, and the 1998

congressional elections should proceed as

scheduled in the Court's April 21 order.

(App. at 1a.) Later in the order, the court commented that it

- “now concludes thal on the record now before us that race

cannot be held to have been the predominant factor in

redrawing District 12." (App. at 3a.)

Some months earlier, in rendering its memorandum

opinion holding unconstitutional the State’s 1997 redistricting

plan, the court explained its methodology in considering a

remedial plan.* Citing Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978),

) opinion states:

Thus, when the federal courts declare an

apportionment scheme unconstitutional — as the

Supreme Court did in Shaw II - it is

appropriate, ‘whenever practicable, to afford a

This memarandum opinion appears at pages 1a-23a of Ihe jurisdictional

statement submitted by the defendants, who were then appellants, in their

jurisdictional statement in Hunt v. Cromartie (No. 98-85).

7

reasonable opportunity for the legislature to

meet constitutional requirements by adopting a

substitute measure rather than for the federal

court to devis2 and order into effect its own

plan. The new legislative plan, if forthcoming,

will then be the: governing law unless it, too, is

challenged and found to violate the

Constitution.’

Wise, 437 U.S. at 540.

As the district zourt’s language reveals, it reasoned that

after a new redistricting plan has been enacted, those who wish

to challenge it must start anew and the plan is to be viewed as

if it had been written on a clean slale. No effort was made by

the court to examin: what “vesliges” of the prior racial

gerrymanders might remain. The first question presented in this

appeal arises out of the district court’s failure to recognize or

perform its duty of assuring that the "vestiges" of the

unconstitutional 1992 and 1997 racial gemymanders were

eliminated.

The second question concerns the burden of proof.

When the plaintiffs expressed their opposition to the 1998 plan,

the district court placed on them the burden to demonstrate that

race had been the predbminant motive in redrawing District 12.

Instead, the burden should have been placed on the defendants

to show that race had not been the predominant factor; and use

of the plan should not have been allowed unless the court

concluded on the record before it that race had not been the

predominant factor in redrawing Disirict 12.

These errors on the part of the court below caused it to

deny the temporary and permanent injunctions which plaintiffs

sought. If these omissions on the district court’s part are

repeated at the forthcoming trial which that court has ordered,

o

m

)

get

gl

i

P

A

D

R

R

D

1

1

D

o

n

15

:5

7

NO

U

25

a

-—d

~N

oD

(a

o-

31

2

£2

the plaintiffs will be further prejudiced in obtaining the relief to which they are entitled. Moreover, the questions presented

in this appeal have added importance because they will arise in other litigation involving the adequacy of a new redistricting plan as a remedy for a plan that a court has held to be an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

I The Court Below Had the Duty to Determine That

No “Vestiges” of the Earlier Unconstitutional Plans

Remained in the 1998 Plan,

rotection guarantees, many federal district courts were

& Afier racial segregation of schools was held to violate

‘@® equal p

FA

X

NO.

2 required to oversee the Process of school desegregation. As guidance for the district court overseeing desegregation of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system, this Court pointed out that once the equal protection violation had teen proved, the local school authorities and the district court were required to “eliminate .. . al vestiges of state-imposed segregation.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,402 U.S. 1, 15 (197 1s In another school desegregation case, the Court made clear that

the Dayton Board of Education was under a continuing duty to eradicate the effects of segregated schools. See Dayron Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 537 (1979).

Consistent with these pronouncements, the Court of % ppeals for the Tenth Circuit ruled that once plaintiffs had E slablished a prima facie case of de Jure segregation, the =

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

8

defendant board of education had the duty to prove that its efforts to comply with desegregation orders had "eliminated all traces of past intentional segregation to the maximum feasible extent.” Brown v. Board of Education, 892 F.2d 851, 859 (10™

- Such “vestiges” included faculty assignments, transportation, student

assignments, and “racially-identifiable® schools. See United Siates v. Lawrence County Sch Dist., 799 F.2d 1031, 1043 (5th Cir. 1986).

9

Cir. 1989). Similarly, the Fifth Circuit has explained that the

failure of school authorities to satisfy their obligation to

eradicate the “vestiges” of de jure segregation is itself a

constitutional violation. See Taylor v. Ouachita Parish School

Board, 648 F.2d 959, 967-68 (1981); see also Ross v. Houston

Independent School Disirict, 699 F.2d 218, 225 (5* Cir. 1983)

(a school system “must eradicate, root and branch, the weeds of

discrimination”). Implementing the same policy of eradicating

the “vestiges” of the equal protection violation implicit in

racially-segregated schools, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit stated that once the violation had been established, a

plaintiff is “entitled to the presumption that current disparities

are causally related to prior segregation, and the burden of

proving otherwise rests on the defendants.” School Bd. of the

City of Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d 1308, 1311 (4th Cir.

1987). See also Vaughan v. Board of Educ., 758 F.2d 983, 991

(41h Cir. 1985).

A helpful analogy is provided by cases discussing the

effects of the violation of due process rights. Recognizing that

evidence which is the “fruit of the poisonous tree” is

inadmissible without regard to its credibility, the Court held

that a confession obtained shortly after an unconstitutional

search and arrest could not be received as evidence. See

Nardone v. United Slates, 308 U.S. 338 (1939).¢ Similarly, a

confession is inadmissible if it is the “fruit” of an illegal arrest

which has preceded it. See Brown v. lllinois, 422 U.S. 590

(1975); Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200, 216-19 (1979);

Taylor v. Alabama, 457 U.S. 687 (1982).

It seems only logical that the right of a voter to

¢ Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963), which first used the

term "fruit of the poisonous tree,” involved only a statutory violation rather

than a violation of the Constitution.

P

A

G

E

.

89

20

26

82

13

12

S5

8

15

:5

7

NO

U

25

a

I Sa)

~N

OO

«4

o-

21

31

2

a

«©

FA

X

NO.

20

2

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

a

hy 32

LO

-—

[x]

10

participate in an electoral process untainted by equal prolection violations should be given at least as much protection as the right of schoolchildren to be freed from the effects of racially segregated schools or of criminal defendants to be shielded from the use of evidence that was the “fruit” of violations of the Fourth Amendment. Indeed, if the right to vote is the mosl fundamental right of citizenship in a democracy ~ which seems indisputable - it should recejve €ven more protection than other constitutional rights. Although appellants recognize that the Court is concerned that the judiciary not interfere unduly with the work of state legislatures or of the Congress, cf. Wise v. ipscomb, supra, the cited precedents plainly support the Proposition that the three-judge district court had the responsibility to assure thal “vestiges” of an earlier racially gerrymandered redistricting Plan are eliminated and that a replacement plan is not the “fruit* of the earlier unconstitutional plan,’

Although in the Shaw litigation the Court imposed the requirement that plaintiffs demonstrate that race was the predominant motive for creating the Twelfth District in the 1992 plan, appellants submit that a different test should be applied in determining whether a replacement plan retains “vestiges” of the earlier plan. Usually, in determining whether questioned legislation violates equal protection, the issue is whether that legislation would have been enacted in the

The Court has also made clear that persons guilty of a breach of trust should nol retain the benefits of that breach. See, e.g., Snepp v. United Staies, 444 \j.S, 507, 515 (1980) (imposing a constructive trust on proceeds received by a former CIA employee in violation of his contract with that agency.) Here, political benefits resulting fram a constitutional violation are being retained by persons who participated in the violation and their retention is teing justified under the guise of "incumbent protection’ and “maintaining partisan balance.”

«2

s

r

y

"e

m.

S

m

e

e

1]

absence of a race-based purpose. See Village of Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 265-66

(1977); cf. Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985); Mt.

Healthy City Sch. Dist. Bd. of Educ. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274

(1977), Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976). Only if the

Arlington Heights test is employed can a district court be

assured that the “taint” of an earlier racial gerrymander has been

eliminated. Moreover, having already deprived its voters of

equal protection by an unconstitutional racial gerrymander -

and in North Carolina's case two such gerrymanders — the

legislature cannot complain if the Court applies to its most

recent replacement plan the standard usually employed in

determining whether equal protection requirements have been

violated.

In any event, nothing in the opinion of the court below

reflects any awareness on its part of its responsibility to assure

that “vestiges” of the racially-gerrymandered 1992 plan were

not still present in the 1998 plan® Indeed, had the Court

considered whether those “vestiges” were still present, it would

quickly have concluded thal the 1998 plan reflects no genuine

attempt to eliminate “vestiges” of the 1992 plan, which this

Court analogized to “apartheid” and ruled unconstitutional.

Even a visual comparison of the 1998 plan with the 1992 plan,

which this Court held unconstitutional, with the 1997 plan,

which the district court held unconstitutional, reveals that the

' Even though this Court did not rule on the constitutionality of the First

District in the 1992 plan because of a lack of standing of the Shaw

plaintiffs, Cremartie and his fellow plaintiffs — who are now appellants -

have consistently claimed that the original First District was an

unconstilutional racial gerrymander. If that premise is correct - which

seems obvious in light of the District's demographics and lack of

geographical compactness — the lower court was also under a duty to assure

that the First District as it exists in the 1998 plan has none of the "vestiges"

of the zarlier First District and is not the “fruit” of that poisonous tree.

1A

Pa

nR

F

2

A

P

R

R

2

1

3

1

"

12

Current plan retains many “vestiges” of its predecessors. For = example, the Twelfil District still is not “geographically a: ‘ompacl.” Although not all of its counties are divided — as was frue in the 1992 and 1997 plans - four of its five counties are split in the new Plan; and this ratio js higher than for any of North Carolina's eleven other districts ®

The 1998 plan still links two of the State's most populous counties, Mecklenburg and Forsyth ~ which are in different Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) and different media markets and which, until 1992, had not been in the same

than in any of the three counties which are used to link Mecklenburg with Forsyth. Thus - just as in the 1992 plan, held unconstitutional in Shay - a predominantly rural, "white corridor” was created to link artificially two unrelated black- concentrated urban cores located in Separate metropolitan areas! fF urthermore, apart from Guilford County, which was

Lo umerous counties - was a flagrantly unconstitutional racial gerrymander —but also thay jis continuing “taint” is obvious in the First District of the 1997 tn and 1998 plans.

wo Foranother example of the use of such corridors, see Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995).

13

totally removed from District 12, only three precincts having

forty percent or more African-American population were

removed fiom the 1997 plan’s District 12 when the 1998 plan

was redrawn."

If percentages of African-American population are

reflected on a map of the state's urban areas — areas which are

for the most part in the Piedmont” - it becomes readily

apparent that the black population is sufficiently dispersed thal

no urban district can be drawn which will conform with

traditional race-neutral redistricting principles and yet will have

a population which is much more than 25% African-American.

Any significantly higher concentration of African-Americans

within a single district in the Piedmont - where they are

primarily located in urban areas - is an obvious “vestige” of the

unconstitutional 1992 and 1997 plans. Over 35% of the

population of the “new” Twelfth District is African-American --

a percentage which can only be explained as the result of a

predominant purpose to group voters by race across scparate

metropolitan areas.

In its memorandum opinion of April 14, 1998, which

invalidated the 1997 redistricting plan, the three-judge district

court stated that, in redrawing the plan, “the legislature may

consider traditional districting criteria, including incumbency

considerations, to the extent consistent with curing the

"Guilford County, which has several precincts with a high percentage of

African-Americans was (otally removed from the Twelfth Districl.

Ironically, Guilford County — unlike Mecklenburg County ~ is in the same

Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) and same television market (DMA) as

the adjacent Forsyth County; and also it is tke only county in the 1997

version of District 12 that was subject to preclearancs under Section 5 of

the Voting Rights Act. See 42 U.S.C. § 1973c.

'" Appellants lodged such maps with the Court in Hunt v. Cromartie (No.

98-85) in which they were the appellees.

P

O

R

E

11

P

A

D

R

R

2

1

R

1

2

'

8

8

.

1

5

:

5

8

NO

U

25

14

= conslitutional defects "3 Presumably, when the district court permitted use of the 1998 plan for the current elections, it was ol continuing to allow legislators lo rely on “incumbency considerations” - to which the General Assembly admittedly had given great weight in drawing that plan.

Although appellants recognize that in the first instance a legislature may consider “incumbency” in redistricting, allowing “incumbency” to . be considered when the or Representatives in office have been elected pursuant to a ™ racially-germrymandered plan is inconsistent with eliminating S he “vestiges” of that plan. The flagrantly unconstitutional

oO

district created with the express objective of assuring election “- of an African-American to Congress from that district. To allow a plan to be drawn which has as iis purpose - or even considers - the protection of this Representative's race-based incumbency is at odds with removing the “taint” of the 1992 plan." An acknowledged goal of the General Assembly was to "maintain the partisan balance of the Stale’s congressional delegation.” (App. at 4a) Maintaining a "partisan balance” which has resulted from elections conducted under an unconstitutional race-based Plan also is at odds with removing a of the earlier gerrymandering." Indeed, in North

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

See Hunt v. Cromartie (No. 98-85), Appendix to J.S., at 22a. "Of course appellants are not contending that this incumbent should be disqualified from running or that an effort should be made to penalize him; tut the General Assembly’s effort to help him attain reelection conflicts with the basic goal of removing unconstitutional “vestiges.” Also it induces in vofers a loss of hope for participating in the electoral process. "* The same can be said with respect to the General Assembly’s purpose “to keep incumbents in Segregated districts and preserve the cores of those

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

9

“15

Caro. ina, which now has six Democratic incumbents and six

Republican incumbents, “maintaining partisan balance” is a

euphemism for retaining the status quo, keeping in office

incumbents elected pursuant to a race-based redistricting plan,

and thereby perpetuating the unconstitutional results of the

gerrymandering."

As seems clear from its opinions, the thres-judge

district court did not recognize its duty to assure that the 1998

plan was not the "fruit of the poisonous tree.” Had it done so,

the court would have concluded readily that the 1998 plan was

itself’ unconstitutional because it retained "vestiges* of ils

predecessor plans. In view of pending proceedings in this case

—- including a trial — the Court should provide clear guidance to

the three-judge district court that it must satisfy itself that the

“taint” of the 1992 race-based plan has been finally removed.

This guidance also will greatly benefit other courts called upon

to evaluate redistricting plans which replace plans held

unconstitutional.

II. The District Court Should Have Placed on the State

Defendants the Burden of Proving That the 1998

Plan Was Not Race-Based.

In its order allowing the congressional elections to

proceed pursuant to the 1998 plan, the three-judge district court

districts." (App. al 4a.) In this context, “cores” is the functional equivalent

of '"vesliges’; and protecting “cores” of racially gerrymandered

congressional districts is no more to be tolerated than preserving the

“vestiges” of racially segregated schools.

' Understandably the use of such euphemism heightens public cynicism

about the purpose and value of elections. Moreover, in the present contex|

to accept the logic of “incumbency considerations” would permil

reenactment of the most flawed racially gerrymandered plan for the alleged

purpose of prolecting incumbents elected pursuant to that plan.

P

a

r

e

1

2

P

2

A

D

A

R

2

1

R

1

2D

9

8

15

:5

9

NO

U

25

P.

13

/1

8

50

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

16

stated, “[b)ecause the Court cannot now say thal race was the predominant factor in the drawing of District 12 jn the 1998 congressional districting plan, the revised plan is not in violation of the Unijled States Constitution.” (App. at la.) Appellants have already pointed out that in dealing with a plan which replaces a racially gerrymandered plan, the standard should be hat of Arlington Heights - whether the plan would have been adopted absent the racial motive - rather than whether "race was the predominant facior,”!?

However, even if the test is still to be whether a racial molive predominaled, the State defendants ~ who committed the constitutional violations - should bear the burden to establish that race was nor the predominant motive; and the burden should not have been placed on the plaintiffs to establish that race stil predominated in drawing District 12. This conclusion is a logical corollary of the principle that “vestiges” of the unconstitutional plan should be eliminated. Thus, in comparable cases involving school desegregation, the burden was placed on the defendants to prove that they had eliminated the constitutional violation. Cf. School Bd. of Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d at 131 1; Vaughan v. Board of Educ., 758 F.2d at 99 hig

In Hise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. at 540, the Court stated, “The new islative plan, if forthcoming, will then be the governing law unless it, loo, is challenged and found to violate the Constitution.” However, appellants do not interpret this statement to mean that when the new plan "is challenged,” tha challenge will be considered as if there had been no preceding violation. Not to consider the prior violations would conflict with the principle that *vestiges® of an unconstitutional plan should be eliminated and 2lsp would facilitate evasion of equal proteclion guaraniees.

Similarly, the burden of Proof seems 10 have been placed on the prosecution to demonstrate that the “aint” arising out of an illegal arrest in violation of the Fourth Amendment had been eliminated prior to obtaining

17

The misallocation of burden of proof helped lead the

court below to an erroneous result. It is especially important

that this error not be repeated in future proceedings in this case

or duplicated in other litigation which concerns the remedying

of unconstitutional racial gerrymanders.

CONCLUSION

The three-judge district court erred in denying

appellants their requested injunction against use of the 1998

redistricting plan in any congressional primary or election.

Therefore, its order should be set aside and the Court should

provide clear guidance to the court below as to its full scope of

its responsibilities in reviewing the 1998 plan. This guidance

also will help other courts avoid similar errors in future

redistricting cases.

Respectfully submitted, this the 15" day of September,

1998.

ROBINSON O. EVERETT*

MARTIN B. McGEE

Attorneys for the Appellants

*Counsel of Record

a confession. See Taylor v. Alabama, 457 U.S. at 690; Dunaway v. New

York, 442 U.S. al 216-19; Brown v. lllinois, 422 U.S, al 603-4.

P

O

R

E

1

P

A

D

R

A

2

1

2D

O

B

15

:5

9

NO

U

25

APPENDIX

li

m

s

‘ON

Xv4d

040

04

407

OWGN

19:1

(3M

86-G2-AON

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ORDER OF UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF

NORTH CAROLINA, JUNE 22,1998 ......... la

P

A

G

E

.

14

:

NOTICE OF APPEAL TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE UNITED STATES, FILED JULY 17,

1008. J idnsnicinn sass urs vniets snsnns sini 6a

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

NO

U

25

'S

8

16

:0

0

e

s

ON

Xb

040

00

41

®

.

19:91

(3M

86-S2-AON

la

ORDER OF UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA,

JUNE 22, 1998

[C aption omitted in printing]

This matter is before the Court on the Defendants’

submission of a congressional districting plan for the 1998

congressional elections (the “1998 plan’). By Order dated

April 21, 1998, this Court directed the North Carolina General

Assembly to enact legislation revising the 1997 congressional

districting plan and. to submit copies to the Court. The General

Assembly enacted House Bill 1394, Session Law 1998-2,

redistricting the State of North Carolina's twelve congressional

districts, and the Defendants timely submitted the 1998 plan to

the'Court. The Plaintiffs subsequently filed an opposition and

objections to the 1998 plan, and the Defendants have responded

to the Plaintiffs’ objections. On June 8, 1998, the United States

Department of Justice precleared the 1998 plan pursuant to

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,42 U.S.C. § 1973c,

and this Court must now decided whether the 1998 plan

complies with the Equal Protection Clause of the United States

Constitution. |

Because the Court cannot now say that race was the

predominant factor in the drawing of District 12 in the 1998

congressional districting plan, the revised plan is not: in

violation of the United States Constitution, and the 1998

congressional elections should proceed as scheduled in the

Court’s April 21 Order.

%* k ok Xk

In Shaw v. Hunt, the United States Supreme Court

considered challenges 1o North Carolina's 1992 congressional

PA

GE

.

1S

20

26

82

13

12

’S

8

16

:0

0

NO

U

25

a

tt

NN

«©

et

a.

31

2

«©

FA

X

NO.

20

26

8

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

<TC N

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:5

1

2a

districting plan (the *1992 plan”) and held that the Twelftl Congressional District ("District 12") in the 1992 plan was drawn with race as the predominant factor, that the districting plan was not narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest, and that the 1997 plan violated the Equal Protection Clause. 509 U.S. 630,113 S.Ct. 2816, 125 L.Ed.2d 511 (1993) (“Shaw I"); 517 U.S, 899, 116 S.Ct. 1894, 135 L.Ed.2d 207 (1996) ("Shaw nr).

After the North Carolina General Assembly redrew the op State’s congressional districting plan in 1997, the Plaintiffs in his action challenged the constitutionality of the 1997 plan in this Court. Specifically, the Plaintiffs argued that the Twelfth and First Congressional Districts were unconstitutional racial germymanders. Each party moved for summary Judgment, and in an Order dated April 3, 1998, the Court granted summary judgment in favor of the Plaintiffs with respect to District 12, Like the Supreme Court ip Shaw, this Court held that race was the predominant factor in the drawing of District 12 in the 1997 plan, and that the district was violative of Equal Protection. In its April 3 Order, the Court instructed the Defendants to submit a new plan in which race was not he predominant factor in the drawing of District (2.

The Court found that neither party could prevail as a tter of law with respect to District 1, and denied summary Judgment as 1o that district. Neither this Court nor the Supreme Court in Shaw has made a legal ruling on the conslitutionality of District 1 under the 1992, 1997, or 1998 congressional districting plans.

+ % 2

In Wise v. Lipscomb the Supreme Court advised that “[wlhen a federal court declares an existing apportionment

E

m

m

"

8

SS

ED

A

R

E

E

a

fC

SA

S

G

E

§

3a

scheme unconstitutional, it is . . . appropriate, whenever

practicable, to afford a reasonable opportunity for the

legislature to meet constitutional requirements by adopting a

substitute measure rather than for the federal court to devise

and order into effect its own plan.” 437 U.S. 535, 540, 98 S.Ct.

2493, 2497, 57 L.Ed2d 411 (1978). In reevaluating a

substitute district plan, the court must be cognizant that "a

state’s freedom of choice to devise a substitute for an

apportionment plan found unconstitutional, either in whole or

in part, should not be restricted beyond the clear commands of

the Equal Protection Clause. Id. (quoting Burns v.

Richardson, 384 U.S. 73, 85, 86 S.Ct. 1286, 1293, 16 L.Ed.2d

376 (1966)). Finally, as the Supreme Court has noted, because

"federal court review of districting legislation represents a

serious intrusion on the most vital of Jocal functions,” this

Court must “exercise extraordinary caution in adjudicating” the

issues now before it. Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900,916,115

S.Ct. 2475, 2488, 132 L.Ed.2d 762 (1995).

Because this Court held only that District 12 in the 1997 - -

plan unconstitutionally used race as the predominant factor in

drawing District 12, the Court is now limited to deciding

whether race was the predominant factor in the redrawing of

District 12 in the 1998 plan. In reviewing the General

Assembly’s 1998 plan, the Court now concludes that on the

record now before us that race cannot be held to have been the

predominant factor in redrawing District 12. In enacting the

1998 plan, the General Assembly aimed to specifically address

this Court’s concerns about District 12. Thus, the present

showing supports the proposition that the primary goal of the

legislature in drafting the new plan was “to eliminate the

constitutional defects in District 12.” Aff. of Gerry F. Cohen.

The State also hoped to change as few districts as possible, to

maintain the partisan balance of the State's congressional

delegation, to keep incumbents in separate districts and

P

o

E

1

&

P

2

A

2

R

R

A

2

1

1

2

NO

U

25

’'

98

1

6

:

0

1

+ 4a.

preserve the cores of those districts, and to reduce the division of counties and cities, especially where the Court found the divisions were based on tacial lines. Md.

a

Ri

Nn

r~—

——

o-

With the foregoing in mind, the General Assembly successfully addressed the concerns noted by the Court in its Memorandum Opinion for the purposes of the instant Order. Thus, the 1998 plan includes a Twelfih Congressional District with fewer counties, fewer divided counties, a more “regular” geographic shape, fewer divided towns, and higher dispersion and perimeter compactness measures. District 12 now contains five, rather than six, counties, and one of those counties js whole. District 12 no longer contains any part of the City of | Greensboro or Guilford County. The 1998 plan no longer divides Thomasville, Salisbury, Spencer, or Statesville. The new plan also addresses the Court’s concem that it not assign precincts on a racial basis. While the Court noted in jts Memorandum Opinion tha the 1997 plan excepted form District 12 many adjacent “voling precincts with less than 35 percent African-American population, but heavily Democratic voting registrations,” the 1998 plan includes fourteen precincts in Mecklenburg County in which previous Democratic performance was sufficient lo further the State’s interest in maintaining the partisan balance within the congressional delegation. The General Assembly also added several F orsyth County precincts to smooth and regularize the District’s @oundavics These changes resulted in a total African- American population in District 12 of 35 percent of the total population of the district, down from 46 percent under the 1997 plan.

FA

X

NO.

20

26

82

13

12

Ve

ce

—

te

w

w

.

i

n

a

cae

ra

in

s

NA

AC

P

LD

F

DC

OF

C

¥ kx §

Based on the foregoing, the Court now accepts the 1998 plan as written. The 1998 congressional elections will thus proceed under this plan, as scheduled in this Court’s April 21,

J

LO

Lo

4

[an

88)

-=

(o0]

T

Ln

S

S

po

VE

ne

c

e

—

w

w

@

i

a

n

cee

wv

nl

es

-

ce

em

im

e

g

m

—

_

Sa

1998, Order. As noted above, neither this Court nor any other

has made a legal ruling on the constitutionality of District I.

The 1998 plan is only approved with respec! lo the 1998

"congressional elections, but the Court reserves jurisdiction with

regard to the constitutionality of District 1 under this plan and

as to District 12 should new evidence emerge. This matler

should therefore proceed with discovery and trial accordingly.

The parties are ordered to submit proposed discovery schedules

to the Court on or before June 30, 1998. ;

SO ORDERED.

This 19" day of June, 1998.

SAM J. ERVIN, 111

United States Circuit Judge

TERRENCE W. BOYLE

Chief United States District Judge

RICHARD L. VOORHEES

United States District Judge

P

A

G

E

.

17

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

NO

U

25

S9

8

16

:8

1

a

hE

a

—

0.

FA

X

NO.

“

@

®

°

"

'

®

LD

F

DC

OF

C

J

LO

Lo

——

oo

Lx)

=

<0

5

LO

2

=

oO

=

6a

NOTICE OF APPEAL TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Nolice is hereby given that Martin Cromartie, ef al, the plaintiffs above-named, hereby appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States from the Order of the three-judge District Court dated June 19, 1998, approving the 1998 congressional redistricting plan for use in the 1998 congressional elections in accordance with the schedule provided in the Court’s April 21,

1998 Orde;.

This appeal is taken pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

Respectfully submitted, this the 17* day of July, 1998.

/s/ Robinson O. Everett

/s/ Martin B. McGee

-

e

e

E

e

e

an

.

—

—

—

a

—

—

n

e

E

n

e

En

—

—

—

a

—

i

[V1]

2

0

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

rl >

’S

8

1

6

:

0

NO

U

25

a

«4

~~

(QV

OO

o-

FA

X

NO.

a

5

L]

ai

i

DC

OF

C

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

5

No. 98 -450

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TIIE

UNITED STATES

October Term, 1997

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al,

Appellants,

Vv.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., in his official

capacity as Govemor of the

State of North Carolina, ef al.,

Appellees.

|

ON APPEAL

FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

MARTIN B. McGEE ROBINSON O. EVERETT*

Williams, Boger, Grady Everett & Everett

Davis & Tutile, P.A. P.O. Box 586

P.O. Box 810 Durham, NC 27702

Concord, NC 28026-0810 (919)-682-5691

(704)-782-1173

* Counsel of Record

WL

C

E

a

t

e

—

—

a

—

—

—

i

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

After the 1992 and 1997 redistricting plans had been

held unconstitutional as racial gerrymanders and the

General Assembly had enacted a new plan, was the

district court required to determine thai any

unconstitutional vestiges of tlie earlier plan bad been

removed before allowing the 1998 plan to be used in

elections?

In determining whether the 1998 plan was an adequate

remedy for the unconstitutional defects of the 1992 and

1997 racial gerrymanders, should the three-judge

district court have placed on the State defendants the

burden of proving that race did not predominate as a

motive in drawing Districts 1 and 12?

CEIWE

VE

AN

aN

NO

U

25

’S

8

15

:5

4

a

«4

Ne

(9.0)

(a)

o-

FA

X

NO.

y

a

a

DC

OF

C

LO

<r

Lo

cD

ix)

=

(oo)

i

LO

i

=

oO

-—

ii

LIST OF PARTIES

MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS CHANDLER MUSE,

R.O. EVERETT, JH. FROELICH, JAMES RONALD

LINVILLE, SUSAN HARDAWAY, ROBERT WEAVER and

JOEL K. BOURNE are appellants in this case and were

plaintiffs below;

JAMES B. HUNT, JR,, in his official capacity as Governor of

the State of North Carolina, DENNIS WICKER in his official

capacity as Lieutenant Govemor of the State of North Carolina,

HAROLD BRUBAKER in his official capacity as Speaker of

the North Carolina House of Representatives, ELAINE

MARSHALL in her official capacity as Secretary of the State

of North Carolina, and LARRY LEAKE, S. KATHERINE

BURNETTE, FAIGER BLACKWELL, DOROTHY

PRESSER and JUNE YOUNGBLQOOD in their capacity as the

North Carolina State Board of Elections, were defendants

below and are appellees in this case.

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, DAVID MOORE, WILLIAM M.

HODGES, ROBERT L. DAVIS, JR, JAN VALDER,

BARNEY OFFERMAN, VIRGINIA NEWELL, CHARLES

LAMBETH and GEORGE SIMKINS were allowed to

intervene of right as defendants at the time of the order

appealed from; and as defendant-intervenors they are included

as appellees.

Apart from the defendant-intervenors who are inciuded as

appellees in this appeal, the parties in this case are the same as

in the separate appeal filed earlier in Hunt v. Cromartie, No.

98-85, in which the present appellants, Cromartie, ef al., who

were plaintiffs in the three-judge district court, were appellees

and the present appellees, Hunt, er al., who were defendants

below, were appellants.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED iii. aa abs i

WSTOFPARTIES . .. &....., 0.00 oe 7 ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES... .../...... ....° iv

OPINION BELOW... ss iain, wo 2

JURISDICTION ........ a ai sa 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED ’ rien sain Seeis nti

SIATEMENTOPTHECASE .ovu. oii 3

ARGUMENT she vs tess oe vo nda 0 Ls 5

INTRODUCTION. o.oo. 5

I. THE COURT BELOW HAD THE DUTY TO

DETERMINE THAT NO "VESTIGES" OF THE

EARLIER UNCONSTITUTIONAL PLANS

REMAINED IN THE 1998 PLAN .......... 8

I. THE DISTRICT COURT SHOULD HAVE

PLACED ON THE STATE DEF ENDANTS THE

BURDEN OF PROVING THAT THE 1998 PLAN

WAS NOT RACE-BASED sr tines sens mess iy 18

CONCLUSION... 5... 4. os Beis inis nien’s sie ian a 17

0]

NO

U

25

*S

8

1

5

:

5

4

Vv

wo TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Sh

or Brownv. Board of Educ., 892 F 24 851 (10th Cir. 1989) .. 8

Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590 (1075) ..... 5..." 9.17

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526 (1979)... 3

Dunaway v. New York, 442 US. 20001979) ...... ... 9.17 ad

®P Hunt v. Cromartie, S. Ct. No. 98.88... Lu passim a

«©

SS Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1988) x, 0. ou [1

= Miller v. Johnson, 515 US. 900 (1998). = mo 12 bao

<C

"Mt. Healthy City Sch. Dist. Bd of Educ. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. cro ivy Dine REIS Tn lel dn 11

Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338 (1339).......... 9

= Ross v. Houston Ind. Sch. Dist , 699 F.2d 218 (Sth & in utetetiien. org ue LE I ie 9

Q® Bd. of the City of Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d 2 1308amCin 08. 280 = 9, 16 <I &

| = Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 Q996Y..... 27. passim

wo Snepp v. United States, 444 U.S. 507 (1980) ....... | 10

= Swann v. Chay lotte-Mecklenburg Bd of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (OY... pie. i Oa Cl 8

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WED

Vv

Taylor v. Alabama, 457 U.S. 687 (198... vis... 9

Taylor v. Ouachita Parish Sch, Bd., 648 F.2d 959

Alii of CECE Die SiO, |

United States v. Lawrence County Sch. Dist., 799 F.2d 103]

UCI 1986)... eb ii ia 8

Vaughan v. Board of Educ., 758 F.2d 983 (4th Cir.

1983) ou ten a 16

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Dev. Corp.,

429038. 2520197... hae TE 911,16

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ....... .... 3

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978). 5% ..... 6.7, 10, 16

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963) ........9

vi

o CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS ANG

LO

i US. Const, Amend. xiv®,. 008 0. 0 0 2.3

WUSC.31283 2... as a 2,3

PUSC Ie ue, eo 13

oS N.C. Gen. Stat. § 163-2000)... iii iS j, 2

» 1992 N.C. Sess Laws, Chl) . 0000. any 20 4

«©

(QV)

N IS98 N.C. Sess. Laws, Ch. 2 ©. vs. al oa 1:23

(=)

a

ps

ir

a

i

DC

OF

C

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

6

No. 08. 450

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES

October Term, 1998

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.,

Appellants,

V.

JAMES B. HUNT, JR,, in his official

capacity as Governor of the

State of North Carolina, ef al,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL

FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Martin Cromartie and the other Plaintiffs below appeal

from the Order of the United States District Court for the

Eastem District of North Carolina, dated June 22, 1998, which

denied to appellants the temporary and permanent injunction

which they had sought to enjoin the State appellees from

conducting any elections under the congressional redistricting

plan enacted by the North Carolina General Assembly on May

21, 1998. See 1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, Ch. 2, amending N.C.

Gen. Stat. § 163-201 (a). Plaintiffs filed notice of appeal on July

a

«4

NY

«©

SE

0.

FA

X

NO.

a

i

y

4

DC

OF

C

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WED

15:

45

2

17, 1998 and jurisdiction of this appeal is conferred on this

Court by 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

OPINION BELOW

The June 22, 1998 opinion of the three-judge district

court, which has not yet been reported, appears in the appendix

to this jurisdictional statement at 1a.

JURISDICTION

The district court's order denying the injunction was

entered on June 22, 1998. On July 17, 1998, appellants filed a

notice of appeal to this Court. The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This appzal concems the constitutionality of 1998 N.C.

Sess. Laws, Ch. 2, which amended N.C. Gen. Stat. § 163-

201(a); copies of this Session Law were previously lodged with

the Court by the present appellants in connection with the

Motion to Dismiss or, in the Alternative, to Affirm which they

filed in Hunt v. Cromartie (No. 98-85), where they are

appellees.

The present appeal involves the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment which provides:

All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,

are citizens of the United States and of the State

wherein they reside. No State shall make or

enforce any law which shall abridge the

privileges or immunities of citizens of the

3

United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due

process of law; nor deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This appeal is taken pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1253

which provides: :

Except as otherwise provided by law, any party

may appeal to the Supreme Court from an order

granting or denying, after notice and hearing, an

interlocutory or permanent injunction in any

civil action, suit or proceeding required by any

Act of Congress to be heard and determined by

a district court of three judges.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE!

In Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) (“Shaw II"), the

Court held that District 12 in North Carolina’s 1992

congressional redistricting plan (“the 1992 plan”) violated the

Equal Protection Clause because race predominated in the

design of the Twelfth Congressional District, and the plan

could not survive strict scrutiny. The Court declined to

consider the constitutionality of the First District in the 1992

plan because none of the plaintiffs had standing. Therefore, a

separate action was initiated by Martin Cromartie and other

registered voters in the First District to challenge its

constitutionality.

'! The present appellants have provided the Court a more detailed

statement of the relevani facts in their Counterstatement centained in the

Motion to Dismiss or, in the Alternative, to Affirm which they filed in Hum

v. Cromartie (No. 98-85), which involves the same parties.

pa

te

r

Q

a

1

5

:

5

5

N

O

U

2

S

©

-—d

BE =~!

Fane

a.

FA

X

NO.

a

Ll

“o

d

DC

OF

C

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

6

4

The action filed by Cromartie was stayed by consent

awaiting further proceedings in the Shaw litigation, which had

been remanded to the lower court, That court granted the State

legislature an opportunity to redraw the State’s congressional

plan to correct its constitutional defects; and on March 31,

1997, the North Carolina General Assembly enacted a new

congressional redistricting plan, 1997 Session Laws, Chapter

LT (“the 1997 plan”). The 1997 plan was precleared by the

Departruent of Justice for use in the 1998 and subsequent

elections; and in September 1997 it was accepted by the lower

court as a remedy for the claim asserted by the Shaw plaintiffs,

who under the 1997 plan were no longer residents of the

Twelfth District.

Shortly thereafter, the stay in the action brought by

Cromartie was dissolved; and an amended complaint was filed,

which alleged that the 1997 redistricting plan was also an

unconstitutional racial gerrymander and that race had

predominated in drawing both its First District and its Twelfth

District. The amended complaint included as plaintiffs

registered voters both of the First and the Twelfth Districts.

After a hearing on March 31, 1998, the three-judge

district court before which the case was pending granted

summary judgment for the plaintiffs as to the Twelfth

Congressional District and enjoined the defendants from

conducting any primary or general election under the 1997

redistricting plan. The state defendants gave notice of appeal

and also applied unsuccessfully to the district court and to this

Court for an emergency stay of the injunction. Subsequently,

the State defendants filed a Jurisdictional Statement in this

Court, Hunt v. Cromartie (No. 98-85); and in response the

2 See Appendix la, 4a, 45a of the Jurisdictional Statement filed in Hunt v. Cromartie (No. 98-85 ).

I

3

|

5

plaintiffs have filed a Motion to Dismiss or, in the Alternative,

to Affirm, which is now pending.

Instead of immediately undertaking to drafl its own

redistricting plan in order to remedy the constitutional defects,

the three-judge district court allowed the General Assembly an

opportunity to enact siill another redistricting plan. On May

21, 1998 a new plan (“the 1998 plan’) was enacted, which was

to be used for the 1998 and 2000 elections, unless this Court

reverses the district court decision holding the 1997 plan

unconstitutional. See 1998 N.C. Sess. Laws, Ch.2. Afier the

Department of Justice had precleared this plan, the plaintiffs

filed an opposition and objection to that plan, and the

defendants responded thereto.

On June 22, 1998, the three-judge district court

approved this plan "with respect to the 1998 congressional

elections,” because the court “concludes that on the record now

before us that race cannot be held to have been the predominant

factor in redrawing District 12.” (Appendix al 3a.) However,

the district court reserved “jurisdiction with regard to the

constitutionality of District I under this plan and as to District

12 should new evidence emerge,” and it directed that the case

“should therefore proceed = with discovery and tial

accordingly." (App. at 5a.) The plaintiffs gave notice of

appeal with respect to this order.

ARGUMENT

Introduction

This appeal is taken to present for the Court’s decision

questions which concern the obligations of the three-judge

! Subsequently, a discovery schedule has been approved by the district

court. N

O

U

25

S

9

8

1

8

:

5

6

6

district court in determining whether to accept a new

redistricting plan as an adequate remedy for defects in two

earlier plans held to be unconstitutional racial gerrymanders.

The context for these questions is provided by the language of

the order entered below denying the requested injunction.

There the three-judge district court stated:

P.

08

/1

8

Because the Court cannot now say that race was

the predominant factor in the drawing of

District 12 in the 1998 congressional districting

plan, the revised plan is not in violation of the

United States Constitution, and the 1998

congressional elections should proceed as

scheduled in the Court’s April 21 order.

(App. at 1a.) Later in the order, the court commented that jt

“now concludes thal on the record now before us that race

cannot be held to have been the predominant factor in

redrawing District 12." (App. at 3a.)

FA

X

NO.

a

Some months earlier, in rendering its memorandum

opinion holding unconstitutional the State’s 1997 redistricting

plan, the court explained its methodology in considering a

remedial plan.* Citing Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978),

the opinion states:

a

i

DC

OF

C

Thus, when the federal courts declare an

apportionment scheme unconstitutional — as the

Supreme Court did in Shaw II - it is

appropriate, ‘whenever practicable, to afford a

This memarandum opinion appears at pages 1a-23a of the jurisdictional

statement submitted by the defendants, who were then appellants, in their

jurisdictional statement in Hunt v. Cromartie (No. 98-85).

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

7

7

reasonable opportunity for the legislature to

meet constitutional requirements by adopting a

substitute measure rather than for the federal

court lo devis2 and order into effect its own

plan. The new legislative plan, if forthcoming,

will then be the: governing law unless it, too, is

challenged and found to violate the

Constitution.’

Wise, 437 U.S. at 540.

As the district court’s language reveals, it reasoned that

afler a new redistricting plan has been enacted, those who wish

to challenge it must start anew and the plan is to be viewed as

if it had been written on a clean slate. No effort was made by

the court to examin: what “vesliges” of the prior racial

germrymanders might remain. The first question presented in this

appeal arises out of the district court’s failure to recognize or

perform its duty of assuring that the “vestiges" of the

unconstitutional 1992 and 1997 racial gerrymanders were

eliminated.

The second question concerns the burden of proof.

When the plaintiffs expressed their opposition to the 1998 plan,

the district court placed on them the burden to demonstrate that

race had been the predominant motive in redrawing District 12.

Instead, the burden should have been placed on the defendants

to show that race had not been the predominant factor; and use

of the plan should not have been allowed unless the court

concluded on the record before it that race had not been the

predominant factor in redrawing Disirict 12.

These errors on the part of the court below caused it to

deny the temporary and permanent injunctions which plaintiffs

sought. If these omissions on the district court’s part are

repeated at the forthcoming trial which that court has ordered,

rO

8

AS

1

s

NO

U

25

a

4

Bn

oD

<D

oO.

FA

X

NO.

a

B

si

d

DC

OF

C

NO

V-

25

-9

8

WE

D

15

:4

8

8

the plaintiffs will be further prejudiced in obtaining the relief

to which they are entitled. Moreover, the questions presented

in this appeal have added importance because they will arise in

other litigation involving the adequacy of a new redistricting

plan as a remedy for a plan that a court has held to be an

unconstitutional racial genrymander.

I The Court Below Had the Duty to Determine That

No “Vestiges” of the Earlier Unconstitutional Plans

Remained in the 1998 Plan.

Afier racial segregation of schools was held to violate

equal protection guarantees, many federal district courls were

required to oversee the process of school desegregation. As

guidance for the district court overseeing desegregation of the

Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system, this Court pointed out

that once the equal protection violation had teen proved, the

local school authorities and the district court were required to

“eliminate... . all vestiges of state-imposed segregation.” Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,402 U.S. 1, 15 (1971)3

In another school desegregation case, the Court made clear that

the Dayton Board of Education was under a continuing duty to

eradicate the effects of segregated schools. See Dayton Bd. of

Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 537 (1979).

Consistent with these pronouncements, the Court of

Appeals for the Tenth Circuit ruled that once plamtiffs had

established a prima facie case of de Jure segregation, the

defendant board of education had the duty to prove that its

efforts to comply with desegregation orders had “eliminated all

traces of past intentional segregation to the maximum feasible

extent.” Brown v. Board of Education, 892 F.2d 851, 859 (10™

s Such “vestiges” included faculty assignments, transportation, student

assignments, and “racially-identifiable® schools. See United States v.

Lawrence County Sch. Dist., 799 F.2d 1031 , 1043 (5th Cir. 1986).

S

E

B

.

|

-

—

=

9

,

g

r

»

.

|

9

Cir. 1989). Similarly, the Fifth Circuit has explained that the

failure of school authorities to satisfy their obligation to

eradicate the “vestiges” of de jure segregation is itself a

constitutional violation. See Taylor v. Ouachita Parish School

Board, 648 F.2d 959, 967-68 (1981); see also Ross v. Houston

Independent School District, 699 F.2d 218, 225 (5 Cir. 1983)

(a school system “must eradicate, root and branch, the weeds of

discrimination”). Implementing the same policy of eradicating

the “vestiges” of the equal protection violation implicit in

racially-segregated schools, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit stated thal once the violation had been established, a

plaintiff is "entitled to the presumption that current disparities

are causally related to prior segregation, and the burden of

proving otherwise rests on the defendants.” School Bd. of the

City of Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d 1308, 1311 (4th Cir.

1987). See also Vaughan v. Board of Educ.,758 F.2d 983, 991

(41h Cir. 1985).

A helpful analogy is provided by cases discussing the

effects of the violation of due process rights. Recognizing that

evidence which is the “fruit of the poisonous tree” is

inadmissible without regard to its credibility, the Court held

that a confession obtained shortly after an unconstitutional

search and arrest could not be received as evidence. See

Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338 (1939).¢ Similarly, a

confession is inadmissible if it is the “fruit” of an illegal arrest

which has preceded it. See Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590

(1975); Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200, 216-19 (1979);

Taylor v. Alabama, 457 U.S. 687 (1982).

[t seems only logical that the right of a voter to

§ Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963), which first used the

term “fruit of the poisonous tree,” involved only a statutory violation rather

than a violation of the Constitution.

oA

)

PA

2

8

2

6

8

2

1

3

1

2

NO

U

25

9

8

1

5

:

5

7

10

participate in an electoral process untainted by equal protection

violations should be given at least as much protection as the

right of schoolchildren to be freed from the effects of racially

segregated schools or of criminal defendants to be shielded

from the use of evidence that was the “fruit” of violations of the

Fourth Amendment. Indeed, if the right to vote is the mos!

fundamental right of citizenship in a democracy ~ which seems

indisputable - it should receive even more protection than other

constitutional rights. Although appellants recognize that the

Court is concerned that the Judiciary not interfere unduly with

the work of slate legislatures or of the Congress, cf. Wise v.

Lipscomb, supra, the cited precedents plainly support the

proposition that the three-judge district court had the

responsibility to assure that “vestiges” of an earlier racially

gerrymandered redistricting plan are eliminated and that a

replacement plan is not the “fruit* of the earlier unconstitutional

plan,’

a

EI

OQ

-—

o-

FA

X

NO.

'

-

Although in the Shaw litigation the Court imposed the

requirement that plaintiffs demonstrate that race was the

predominant motive for creating the Twelfth District in the

o> 1992 plan, appellants submit that a different test should be