New Trial Asked for Reeves

Press Release

November 12, 1954

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. New Trial Asked for Reeves, 1954. 6f33e2fc-bb92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b0b0aa49-af8e-4dff-bbee-a7338c1089c1/new-trial-asked-for-reeves. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

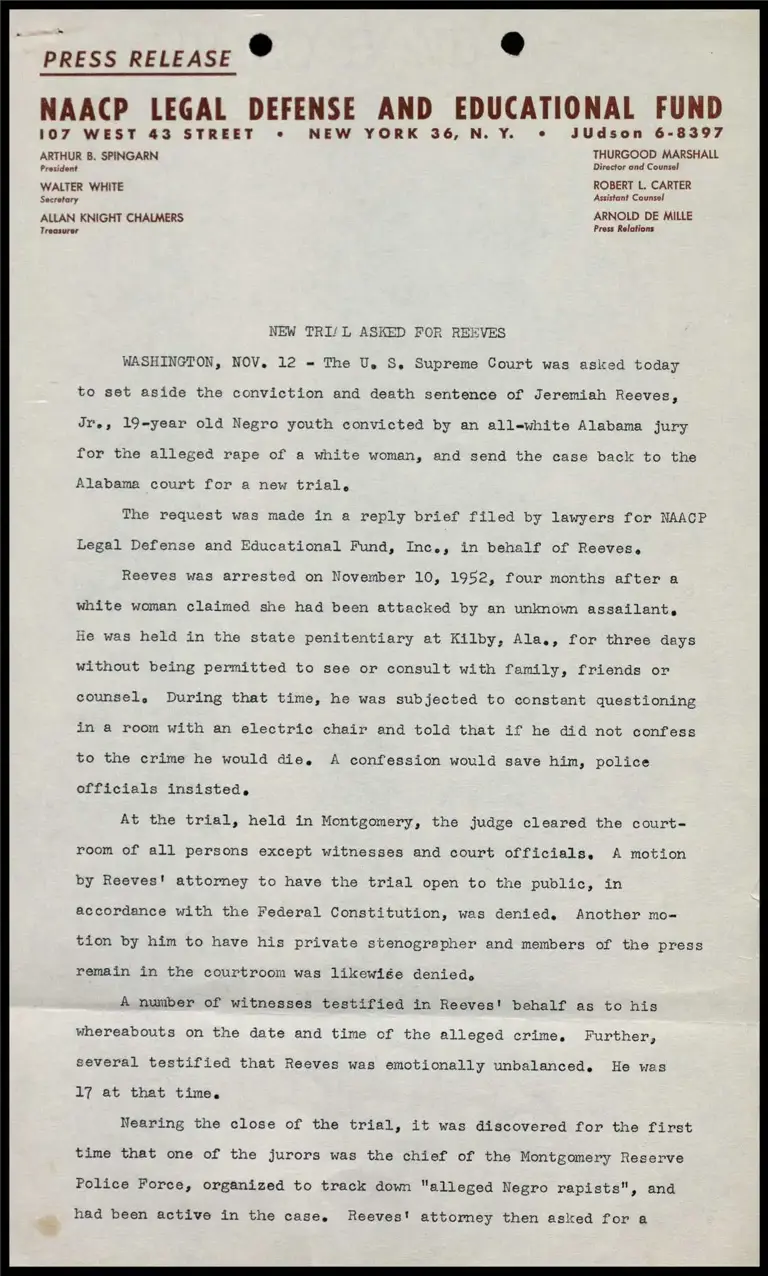

PRESS RELEASE e

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

107 WEST 43 STREET

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN

President

WALTER WHITE

Secretary

ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS

Treasurer

NEW YORK 36, JUdson 6-8397

THURGOOD MARSHALL

Director and Counsel

ROBERT L. CARTER

Assistant Counsel

ARNOLD DE MILLE

Press Relations

NEW TRI‘ L ASKED FOR REEVES

WASHINGTON, NOV. 12 = The U. S. Supreme Court was asked today

to set aside the conviction and death sentence of Jeremiah Reeves,

dre, 19-year old Negro youth convicted by an all-white Alabama jury

for the alleged rape of a white woman, and send the case back to the

Alabama court for a new trial.

The request was made in a reply brief filed by lawyers for NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., in behalf of Reevess

Reeves was arrested on November 10, 1952, four months after a

white woman claimed she had been attacked by an unknown assailant,

He was held in the state penitentiary at Kilby, Ala., for three days

without being permitted to see or consult with family, friends or

counsel, During that time, he was subjected to constant questioning

in a room with an electric chair and told that if he did not confess

to the crime he would die. A confession would save him, police

officials insisted.

At the trial, held in Montgomery, the judge cleared the court-

room of all persons except witnesses and court officials, A motion

by Reeves! attorney to have the trial open to the public, in

accordance with the Federal Constitution, was denied. Another mo-

tion by him to have his private stenographer and members of the press

remain in the courtroom was likewige denied,

A number of witnesses testified in Reeves! behalf as to his

whereabouts on the date and time of the alleged crime. Further,

several testified that Reeves was emotionally unbalanced. He was

17 at that time.

Nearing the close of the trial, it was discovered for the first

time that one of the jurors was the chief of the Montgomery Reserve

Police Force, organized to track down "alleged Negro rapists", and

had been active in the case, Reeves! attorney then asked for a

mistrial. The motion was denied.

A petition for rehearing was denied by the Alabama Supreme

Court on November 27, 1953. NAACP Legal Defense attorneys then peti-

tioned the U. S. Supreme Court for a hearing on March 12, 1954. It

was granted June 7.

NAACP Legal Defense lawyers asked the high court to set aside the

conviction and send the case back to the trial court on the grounds

that Reeves was denied a fair and impartial trial; that the confes-

sion used to convict Reeves was obtained by force, and that Negroes

were systematically excluded from the jury which convicted him.

The attorneys representing Reeves are Thurgood Marshall, direc-

tor-counsel of NAACP Legal Defense, Robert L. Carter, assistant, Jack

Greenberg and Elwood H. Chisolm of Legal Defense staff, Louis ie

Pollak of New York, and Peter A. Hall of Birmingham, Alabama,

TEMPORARY INJUNCTION AGAINST

CAMDEN HOUSING AUTHORITY November 12, 195)

CAMDEN, N.J., Nov. 12.--The Camden, N. J. Housing Authority was

today enjoined from discriminating against Negroes in the selection of

tenants for the remaining vacant units in the Peter McGuire federally-

aided low rent project, by an interlocutory injunction,

The temporary injunction was issued and signed by Judge Vinson

S. Haneman of the New Jersey Superior Court, Camden County, Division

of Chancery, after a three day trial in which seven Negro families

accused the housing officials of assigning all Negro applicants to

Roosevelt, another federally-aided low rent project,

The authorities issued a blanket denial of all charges but the

testimonies of the witnesses indicated that the practice of discrim-

ination does exist. Negro tenants said that rerardless of their

choice of project indicated in their applications, they were system-

atically assigned to the Roosevelt project designated for Negroes.

The trial of Homer Miller v. Joseph McComb began Monday, Novem-

ber 8, and continued through Wednesday, November 10. It was continued

until February 2.

In addition to the seven Negro families, Dr. Ulysses S, Wiggins,

President, Camden Branch of the National Association for the Advance-

ment of Colored People and Mr. Harry Hazlewood, Jr., Chairman of the

Housing Committee of the Camden Branch were plaintiffs in the case.

The suit was brought on their behalf as tax payers of the city of

Camden.

Attorneys for Miller and the Negro residents are Robert Burke

Johnson of Camden, and Mrs. Constance Baker Motley of the staff of

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

=e